iii HOUSING AFFORDABILITY DOWNLOAD IT TODAY has many Texans worried. That’s why this report is important. Reports are also available covering the Houston, DFW, San Antonio, and Austin housing markets. AVAILABLE ONLINE TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY Texas Real Estate Research Center

TIE RR RAND MA ZI

TEXAS REAL ESTATE RESEARCH CENTER

Brave New Virtual World

Virtual reality isn’t new—just ask any seasoned gamer. It is, however, new to the world of real estate, and it could mean exciting possibilities for industry professionals. By

Harold D. Hunt, Bucky Banks, and Steve Ramseur

School Daze

Student Loan Debt Challenges Younger Homebuyers

6 | Come and Take It? Not So Fast

Eminent Domain Revised

Eminent domain has always been a thorn in the landowner’s side. Recent revisions to state law don’t remove the thorn, but they could ease the pain a little. By

Kerri Lewis

10 | Go With the Flow

How Commuting Trends Affect Austin-Area Growth

Daily commutes are a necessary evil for many Texans in urban areas. Who knew they can serve as a bellwether of a region’s economic growth? Austin served as a recent case study. By

Adam Perdue and Reece Neathery

14 | What to Watch for in Texas Land Markets

This spring’s Outlook for Texas Land Markets conference covered a lot of ground, so to speak. Here are some of the key takeaways from experts who were there.

16 | Trading Spaces

Common Mistakes in a Like-Kind Exchange

Like-kind exchanges are popular with real estate investors, but they can be tricky. Here’s your guide to some of the pitfalls to avoid. By

William D. Elliott

19 | Liquidated Damages Clauses How Do They Work?

Liquidated damages clauses are common in Texas real estate contracts, but are they enforceable?

As Research Attorney Rusty Adams writes, “They are until they’re not.” By

Rusty Adams

28 | Practically Speaking

Real Estate Questions Answered

A Seller’s Disclosure Notice is required when selling a home except under certain circumstances. Do you know what they are? You will after you read this column. By Kerri

Lewis and Avis Wukasch

More than 297,000 students graduate from Texas colleges each year, many facing years of student loan debt. Add that to the list of obstacles standing between young people and homeownership. By

Executive Director, GARY W. MALER

Senior Editor, DAVID S. JONES

Managing Editor, BRYAN POPE

Associate Editor, KAMMY BAUMANN

Creative Manager, ROBERT P. BEALS II

Graphic Specialist/Photographer, JP BEATO III

Graphic Designer, ALDEN DeMOSS

Communications Specialist II, HAYLEY WILEY

Circulation Manager, MARK BAUMANN

Lithography, RR DONNELLEY, HOUSTON

Clare Losey

ADVISORY COMMITTEE: Doug Jennings, Fort Worth, chairman; Doug Foster, San Antonio, vice chairman; Troy C. Alley, Jr., Arlington; Russell Cain, Port Lavaca; Vicki Fullerton, The Woodlands; Patrick Geddes, Dallas; Besa Martin, Boerne; Walter F. “Ted” Nelson, Houston;Rebecca “Becky” Vajdak, Temple; and Barbara Russell, Denton, ex-officio representing the Texas Real Estate Commission.

TG (ISSN 1070-0234) is published quarterly by the Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas 77843-2115. Telephone: 979-845-2031.

VIEWS EXPRESSED are those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by the Texas Real Estate Research Center, Division of Academic and Strategic Collaborations, or Texas A&M University. The Texas A&M University System serves people of all ages, regardless of socioeconomic level, race, color, sex, religion, disability, or national origin. Nothing in this publication should be construed as legal or tax advice. For speci c advice, consult an attorney and/or a tax professional.

PHOTOGRAPHY/ILLUSTRATIONS: Getty Images, pp. 1, 2-3, 4-5, 6-7, 10-11, 16, 19, 20-21, 22-23, 25, 26; Alden DeMoss, pp. 14-15.

LICENSEE ADDRESS CHANGE. Log on to your Texas Real Estate Commission account to change your mailing address. © 2022, Texas Real Estate Research Center. All rights reserved.

SUMMER 2022

SUMMER 2022 VOLUME 29, NUMBER 3 www.recenter.tamu.edu

ON THE COVER: The Blue Lagoon, Huntsville. Photographed by JP Beato III.

22 TM

@recentertx

2

BRAVE NEW VIRTUALBRAVEWORLD NEW VIRTUAL WORLD

With work environments rapidly changing virtual office properties could open a new market for real estate professionals. Virtual reality could make it easier and faster to sell office properties, often before buyers ever step foot in them.

By Harold D. Hunt, Bucky Banks, and Steve Ramseur

Everyone from corporate leaders to students on campus are talking about the metaverse. Jamie Dimon and J.P. Morgan are in it. Bob Iger, Disney’s visionary former CEO, is in it. Microsoft spent $70 billion to purchase Activision/Blizzard to gain a foothold in the metaverse. Mark Zuckerberg even changed Facebook’s name to Meta in December.

So what’s all the fuss about? What are they “in”? More importantly, should real estate professionals be in it? If so, is there signi cant money to be made?

Understanding the Metaverse

How the metaverse will impact bricks-and-mortar values is unknown at this point. How it will impact the value of virtual space is just coming into focus. However, for the average person, the speci cs of the metaverse and what it means for their day-to-day lives are largely opaque.

2 TG

Commercial

Shortly after Facebook rebranded itself as Meta, highlighting its pivot into the metaverse, the public began picking up on the term. By the spring of 2022, the word was fully adopted into the popular lexicon. In the simplest terms, the metaverse is an upgrade to the Internet. Essentially, the metaverse uses virtual and augmented reality to replicate the feeling of physical space.

Think of the metaverse as an immersive online experience where individuals can interact with colleagues, clients, or other individuals in ways such as grabbing a virtual cup of coffee or making virtual presentations, all in a virtual office environment. If Zoom and Microsoft Teams are the 2-D versions of the future of work, the metaverse will become the 3-D application of it.

Unlike Web 1.0 and 2.0 (the current version of the Internet), Web 3.0 will seamlessly blend all the best aspects of computer gaming and visual entertainment with e-commerce and social

media, effectively gamifying the user experience. Visiting a website will go beyond discovering clickable pieces of information to “attending” a cohesive, accessible, and immersive event that puts users inside the virtual environment.

The metaverse will allow the user to superimpose an idealized notion of the world. Individuals can experience a variety of virtual property types, such as office, retail, or even conference space, through idealized and virtually constructed versions of themselves. Barriers to entry are greatly reduced, while metaverse space can be restricted or expanded to suit demand.

Why Should Real Estate Professionals Care?

As discussed in “Flight to Quality: Retaining Talent in the Great Resignation” (use QR code to read it), companies are ghting to retain high-quality talent. In relation to office space, post-pandemic worker preferences revealed that up to 100 percent of a rm’s office employees will no longer be coming into the office ve days a week. Employers must create a workplace ecosystem that enables employees to select their preferred work environment based on activities and employee preference. The metaverse adds one more choice at the intersection of where people live, work, and play (see gure).

Environment Choice

3 SUMMER 2022

People PhysicalS p a c e Technology Workers, Shoppers, Conference Attendees HQs,SatelliteO ces, RetailSpace,Etc. Zoom, MS Teams, VR & AR Tech The Metaverse Source: Steve Ramseur

Imagine a world where corporations have a combination of employees working from home, leased or owned office space, and leased or owned space in the metaverse. Meetings can be scheduled on the employee’s preferred platform, whether it be through software applications such as Microsoft Teams or Zoom, at their physical office, or in the metaverse. Such a varied strategy, while helping to control costs, will empower self-management, which has proven to be essential for employee satisfaction.

Work that facilitates connection and a sense of belonging, while providing workers with purpose and meaning, will impact an employee’s decision to remain or leave a given job. A real estate strategy at the intersection of the built and digital environment that offers choice at the lowest possible cost can contribute to these basic human needs. The metaverse will provide users with a simple plan: added convenience and value.

The greatest appeal to the average consumer or worker is convenience. Some employees will commit to remaining in the office, others will elect to become digital nomads, and still others will work a hybrid of the two. Those working from home may want to incorporate metaverse activity into their week to allow for some social interaction, even if only virtual.

The ability to trade digital space and generate real estate revenues from digital space will also appeal to rms. While companies want to put their best foot forward, they will ultimately consider the cost savings when their best foot forward becomes too expensive.

Making Money in the Metaverse

Programmers have found new ways to digitize everything from music and correspondence to social interactions. The free market has shown that anything can be monetized.

As these two basic ideas merge, professionals have begun to look for ways to monetize everything digital, including real estate. This is the central premise of the metaverse: any space that people inhabit online can be bought and sold. Unlike the built environment, which is nite, the metaverse has the potential to become a much larger market. This means more potential sales revenue for real estate professionals.

Another way the metaverse can assist real estate professionals is by providing a listing platform where potential buyers and tenants can explore real property virtually from an immersive, realistic perspective.

The easiest way to guarantee a property trades is to increase the number of eyes on the property. However, showing a property in person has its limitations. Posting the listing online is a 2-D experience, and there are only so many hours in the day to show a property in person.

The metaverse lls the gap between time constraints and the utility of an online listing. By viewing ultra-high-quality 3-D renderings of a given property, potential clients can get a feel for the property before they ever set foot across the threshold. Dozens of clients could walk the space simultaneously from their offices, allowing them to determine just how interested they are before they ever pick up the phone. With 5G network capabilities, the difference between experiencing the property in person and experiencing it through the metaverse will be negligible. Brokers can pro t from

4 TG

helping companies retain talent through the metaverse by doing what brokers do best: creating connections and building relationships. Trading virtual real estate will be entirely about levering relationships. The metaverse will help employers retain high value talent by offering workers more opportunities to connect.

Metaverse Service Companies are Emerging

Companies that are buying and building in the metaverse are actively seeking more opportunities than they have time to nd and vet. The largest participants currently exploring the metaverse are technology and nancerelated rms with limited access to real estate expertise. If brokers want to capture the fees associated with these transactions, they will need to know what spaces are available, who owns them, and what the economics of the space are.

Three companies currently leading the charge in this area are Metaverse Property, SuperWorld, and Swivelmeta. Each of these companies is expanding the footprint of the virtual-built environment. Each one presents brokers with a unique opportunity to pro t.

More speci c uses also exist in the metaverse. SwivelMeta is an Austin-based start-up that has begun to build virtual office space on a build-to-suit basis. Unlike Metaverse Property and SuperWorld, SwivelMeta allows individuals or rms to customize their land and improvements, including the interior space. Corporations and individuals can connect with programmers who implement existing architectural and interior designs or create completely new designs. Many of the spaces will be built on spec and sold or leased between companies and individuals. At this point, most of these transactions are taking place without the assistance of a real estate professional.

Metaverse Property was one of the rst signi cant real estate companies involved in the metaverse.They describe themselves as a virtual real estate company offering exposure to the burgeoning industry of digital real estate. The company facilitates virtual real estate transactions.

Much like Metaverse Property, SuperWorld virtual real estate allows the public to buy, sell, and trade virtual “plots” of real estate. Each plot measures 100 meters by 100 meters (approximately the size of a school football stadium). The virtual land can be held, sold, or developed. These plots provide the customer with the opportunity to create a built environment with features and vistas completely inaccessible in the real world.

Once owned, the property can be monetized through leasing. Spaces can be leased for such uses as e-commerce, gaming, and advertising. Lease negotiations typically resemble real-world agreements.

How to Get Involved

The rst step to getting involved requires nding groups that want to invest in or lease space in the metaverse. Building the right relationships will be critical. Engaging in the metaverse now presents brokers with a “ rst mover” opportunity. Unlike in existing markets with well-de ned commission structures, regulations, and fee pressure, brokers will have the opportunity to set their commissions.

As with every new market opportunity, rst movers should expect to capture the majority share of nancial gains. While the metaverse is not for everyone, it could be well worth the risk for those willing to take the plunge. The future of the office will inevitably become increasingly virtual as the technology becomes more widely available.

Dr. Hunt (hhunt@tamu.edu) is a research economist with the Texas Real Estate Research Center; Banks is associate director and executive assistant professor for Texas A&M’s Master of Real Estate program in Mays Business School; and Ramseur is executive professor for Texas A&M’s Master of Real Estate program.

5 SUMMER 2022

Come and Take Not So Fast

6 TG Land Markets

Eminent Domain Revised

It?

Recently passed laws will change the state’s eminent domain process, improving transparency of the process and the initial offer made by the entity seeking to use private property. By Kerri Lewis

This last legislative session, several bills were passed by the Texas Legislature and signed into law by Gov. Greg Abbott that will alter eminent domain discussions between landowners and condemning authorities (companies or government entities putting in pipelines, utilities, roads, etc.).

Under the revised laws, landowners will receive more information up front regarding the contract terms of an easement and the eminent domain process. These revisions should improve the transparency of the process for the landowner and, hopefully, the initial offer received from the entity seeking to use private property.

Although these bills may not go as far as some landowners would like, they are steps in the right direction.

What is Eminent Domain?

Eminent domain laws in Texas allow for the government or a private entity authorized by law to “condemn” or take private property for the bene t of public use. That means the intended project must be in the best interest of the general public and not solely for the economic gain of the private entity.

The government or private entity may seek all or part of the land outright or may seek an easement across a portion of the land, generally allowing the landowner to continue to use the surface area. But the government or authorized private entity cannot take private property for free. The Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution and Article I, Section 17 of the Texas Constitution prohibit taking or damaging of private property for public use without adequate compensation. What constitutes adequate compensation is usually the most heated area of negotiation between the landowner and the entity with eminent domain authority.

Other areas of negotiation revolve around surface use and other potential damage to the property, livestock, or crops.

What is Condemnation?

Condemnation is the exercise of the power of eminent domain. In Texas, the condemnation process is outlined in Sections 21.012 through 21.016 of the Texas Property Code.

The formal condemnation process comes into play only if the landowner and entity with eminent domain authority (also referred to as a condemning entity) cannot agree on the amount of compensation for the land.

What is the Landowner’s Bill of Rights?

The Landowner’s Bill of Rights requirements are set out in Texas Government Code Section 402.031 and Chapter 21

7 SUMMER 2022

8 TG S C

of the Texas Property Code. It applies to any attempt by the government or a private entity to exercise eminent domain authority to take private land.

The Office of the Attorney General (OAG) of Texas provides a plain-language statement of the landowner’s rights contained in the referenced statutes. That statement is titled “Landowner’s Bill of Rights” and is on the OAG’s website. It contains 11 statements about what an entity must do and what a landowner can do when eminent domain is exercised. In addition, it includes information about the condemnation procedure, the condemning entity’s obligations to the property owner, and the property owner’s options during a condemnation.

Additional addenda described under HB 2730 below are now a part of the Landowner’s Bill of Rights. A recently updated version setting out the updated 11 rights is on page 8. All other relevant legislative changes to the condemnation process, including new addenda, can be found online (use QR code to access).

Recent Legislative Changes

HB 2730

(effective Jan. 1, 2022). This bill made the most comprehensive changes to the eminent domain process. It changed relevant sections of the Texas Government Code, Occupations Code, and Property Code. Speci cally, the revisions:

• require the Landowner’s Bill of Rights prepared by the OAG to

0include notice that the property owner has the right to le a written complaint with the Texas Real Estate Commission (TREC) about misconduct by a registered easement or rightofway agent acting on behalf of the entity exercising eminent domain authority;

0add addenda of the new required terms for easement conveyance documents for pipelines (Addendum A) and electric transmission lines (Addendum B);

0add an addendum of optional terms for those easement conveyance documents that a landowner can negotiate (Addendum C); and

0be reviewed every two years with public input.

• allow the landowner and entity to amend, alter, or omit the contract terms set out in the above-referenced addenda by agreement;

• authorize TREC to

0add continuing education requirements for right-of-way agents;

0issue a probationary certi cate to right-of-way agents; and

0suspend or revoke a right-of-way certi cate if the agent accepts a nancial incentive to make an initial offer less than the adequate compensation required by law.

• require the initial offer by an entity with eminent domain authority to a landowner to be in writing and include 0a copy of the Landowner’s Bill of Rights, including prescribed addenda;

0a statement in bold print, with larger font, indicating whether the compensation being offered includes damages to the remainder of the property or a certi ed

appraisal of the property that includes damages to the remainder;

0the conveyance document, unless certain listed exclusions apply; and

0name and telephone number of a representative of the entity.

• require petitions in a condemnation lawsuit be sent by rst class mail, in addition to certi ed mail, return receipt requested; and

• set deadlines for appointment of special commissioners and alternate special commissioners in a condemnation suit.

HB 4107

(effective Sept. 1, 2021). This bill requires common carrier pipeline entities to provide two days advance written notice to the landowners of their intention to enter the property to conduct a survey under their eminent domain authority. The notice must include an indemni cation provision in favor of the landowner for any damages resulting from the survey and a contact phone number for questions or objections. The notice can be sent by rst class mail, email, or any other delivery method authorized by the Texas Rules of Civil Procedure.

Entry to the property is limited to the portion that is anticipated to be used for the proposed pipeline.

Following the survey, the property must be restored to its pre-survey condition, and the landowner is entitled to receive a copy of the survey or depiction prepared on written request at no charge.

HB 721

(effective Sept. 1, 2021). If there is a special commissioners’ hearing on the valuation of the property, this bill requires an entity with eminent domain authority to give the landowner copies of any appraisal reports produced or acquired by the entity at least three business days before the hearing, if an appraisal report is going to be used at the hearing.

HB 725

(effective Sept. 1, 2021). This provides that a property will not lose its agriculture exemption due to a condemnation for a right-of-way that is less than 200 feet wide. If additional taxes are due because a condemning entity changed the use of land to nonagriculture use, that entity, and not the landowner, is responsible for any additional taxes and interest imposed.

HB 726

(effective Sept. 1, 2021). This bill amended the law relating to a landowner’s ability to repurchase their property from a condemning entity if the entity has not shown “actual progress” on the easement within ten years. The entity must now have completed three of the ve actions enumerated to show actual progress, instead of two. There is one exception; a navigation district, port authority, or water district has to complete only one action to show actual progress.

Nothing in TG should be considered legal advice. For advice or representation on speci c legal matters, readers should retain an attorney.

Lewis (kerrilewis13@gmail.com) is a member of the State Bar of Texas and former general counsel for the Texas Real Estate Commission.

9 SUMMER 2022

Commuting patterns between counties tell much about an area’s economic growth, including which towns will see the most growth, and in which direction that growth will occur. By Adam Perdue and Reece

DNeathery

riven by population growth, small “bedroom communities” in a major metropolitan area occasionally become larger cities with economies that spread beyond their city limits and even across county borders. Sometimes their economies merge with those of neighboring municipalities. The commuting patterns between counties that make up a metropolitan area help illustrate this phenomenon. Take the Austin-Round Rock Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), for example. The Texas Real Estate Research Center

recently explored commuting patterns for Travis County and its neighboring counties to better understand the relationship between the regions that make up Greater Austin.

Tracking Commuting Patterns

The U.S. Census Bureau estimates commuting ows between counties as part of its regular surveys. For the Austin-Round Rock MSA, the Census Bureau estimates the ows between Bastrop, Caldwell, Hays, Williamson, and Travis Counties. Datasets used in this report are from the

10 TG Economy

1990 and 2000 decennial censuses and the 2011-15 ve-year American Community Survey (ACS).

All ve counties have seen growth in both employed residents and employment across the periods covered by the data (see table). Travis County, the region’s center and home to most of the City of Austin, has seen the largest absolute growth, increasing from 349,005 to 677,322 workers who also live in the metropolitan area.

More than a quarter of the residents from each of the outlying counties commute

Counties Encompassing

Austin-Round Rock MSA

Source: Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

Travis349,005 (84%)500,738 (79%)677,322 (74%)

Williamson34,460 (8%)82,928 (13%)160,252 (17%)

Hays 19,871 (5%)30,731 (5%)56,316 (6%)

Bastrop 8,525 (2%)12,290 (2%)16,684 (2%)

Caldwell6,007 (1%)5,866 (1%)8,384 (1%)

Metro417,868 (100%)632,553 (100%)918,958 (100%)

Number/Proportion of Austin-Round Rock MSA Residences by County

Travis297,035 (71%)425,181 (67%)575,759 (63%)

Williamson67,665 (16%)124,007 (20%)220,231 (24%)

Hays 27,504 (7%)46,165 (7%)78,556 (9%)

Bastrop15,851 (4%)25,047 (4%)29,517 (3%)

Caldwell9,813 (2%)

(2%)14,895 (2%)

Metro417,868 (100%)632,553 (100%)918,958 (100%)

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau and American Community Survey

11 SUMMER 2022 183 183 290 21 INTERSTATE 35 INTERSTATE 35 Austin Bastrop San Marcos Lockhart Georgetown Round Rock

BELL TRAVIS BLANCO HAYS BURNET WILLIAMSON MILAM COMAL GUADALUPE CALDWELL BASTROP

FAYETTE GONZALES

LEE

Number/Proportion of Austin-Round Rock MSA Residents Employed in Each County 1990 Census2000 Census 2011-15 ACS

12,153

1990 2000 2011-15

into Travis County for work. Of all the counties, Williamson County has seen the fastest rate of growth, increasing its proportion of total metropolitan area workers from 8 percent in 1990 to 17 percent in 2011-15. The trends are similar in terms of residential location for metropolitan area workers. The proportion of metropolitan area workers who live in Williamson County increased from 16 percent in 1990 to 24 percent in 2011-15. Figures 1 and 2 show the shifts in employment and residential location toward Williamson County. The main relative shift is away from Travis County and toward Williamson County. While Travis County continues to grow in both employment and residents, Williamson County is growing at a faster rate.

Most Travis County residents continue to work in Travis County (Figure 3), but that proportion fell from approximately

1990 2000 2011-15

97 percent in 1990 to an average of less than 92 percent in the 2011-15 ACS (Figure 4). An increasing but still small proportion of Travis County residents works in Williamson County (almost 7 percent) and Hays County (just above 1 percent) (Figure 3). Meanwhile, Bastrop and Caldwell Counties continue to receive only a miniscule number of reverse commuters from Travis County.

Williamson County residents show strong ties only to their own county and to Travis County (Figure 5). As the developed part of the region has moved northward, a growing number of Williamson County residents have found jobs in their own county. Now a larger percentage of them work in Williamson County than in Travis County.

Hays and Bastrop Counties also exhibit strong commuting relationships only with Travis County (Figures 6 and 7). Caldwell County, on the other hand, has decent commuting ties to both Travis and Hays Counties (Figure 8).

Austin’s Influence Moves Northward

The central City of Austin and its surrounding areas continue to grow, with growth largely concentrated to the north toward Williamson County. This means more urban-style development and jobs for Williamson County, which means many of its cities

TG

Figure 1. Austin-Round Rock MSA Residents by County of Work

Travis Williamson Hays Bastrop Caldwell

Percent

Census Bureau, American Community Survey, and Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University 80 60 40 20 0

Williamson Hays Bastrop

80 60 40 20 0

Sources: U.S.

Travis

Caldwell

Percent

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, and Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

Williamson Hays Bastrop Caldwell 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Percent Travis Williamson Hays Bastrop Caldwell 100 80 60 40 20 0

2000 2011-15

Figure 2. Austin-Round Rock MSA Workers by County of Residence

1990

Percent Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, and Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

Figure 3. Travis County Residents by County of Work

are no longer strictly bedroom communities of Austin-Round Rock.

The developed fringe of the central Austin region has only recently expanded beyond the Hays County line along the southern corridor of I-35. It has yet to reach Bastrop or Caldwell Counties, so residents there are likely still focusing on independent local job opportunities and commuting into Travis County.

The strong relationship between Caldwell and Hays Counties is likely due to the I-35 retail corridor and Texas State University, which is just inside Hays’ border.

As the Austin-Round Rock MSA region continues to grow, so should population and employment opportunities in the counties that make up the region. The ties between the counties should strengthen as well.

Dr. Perdue (aperdue@tamu.edu) is a research economist and Neathery a research intern with the Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University.

1990 2000 2011-15

Figure 7. Bastrop County Residents by County of Work

Travis

1990 2000 2011-15

1990 2000 2011-15

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, and Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

SUMMER 2022

97 96 95 94 93 92 91 90

1990 2000 2011-15

Percent Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, and Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University Travis Williamson Hays Bastrop Caldwell 60 50 40 30 20 10 0

Figure 4. Percentage of Travis County Residents Working in Travis County

1990 2000 2011-15

Work Percent Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, and Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

Williamson

60 50 40 30 20 10 0

Figure 5. Williamson County Residents by County of

Travis

Hays Bastrop Caldwell

Percent

and Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

Figure 6. Hays County Residents by County of Work

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey,

Williamson

Bastrop

60 50 40 30 20 10 0

Hays

Caldwell

Percent Sources: U.S. Census

American Community Survey, and Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

Bureau,

60 50 40 30 20 10 0

Travis

Williamson Hays Bastrop Caldwell

Percent

Figure 8. Caldwell County Residents by County of Work

What to Watch for in

Experts in various fields impacting land markets shared their insights at the Texas Real Estate Research Center’s 31st Annual Outlook for Texas Land Markets conference in April. Here are some highlights.

Economy

“Are we going to have a recession? There’s a 33 percent probability of a recession coming in the next 12 to 18 months. Can we avoid it? Yes.”

“It is quite possible that we’ll see a resurgence of stimulus payments and money being piped back into the government to minimize the impact and severity of whatever recession might come.”

DR. JAMES GAINES former chief economist, Texas Real Estate Research Center

DR. JAMES GAINES former chief economist, Texas Real Estate Research Center

Energy Usage

According to 4Q2021 Clean Power Quarterly data, Texas is the leader in wind and solar power generation.

[Regarding ERCOT] ”Overall I think the future is bright, with the key challenge being the need to focus on enhancing grid resiliency to severe events.”

The electric load is likely to increase with one major driver being the electri cation of transportation.

DR. THOMAS OVERBYE professor, Dept. of Electrical & Computer Engineering, Texas A&M University

“If you look at the amount of money that was spent on energy in terms of oil and gas development, infrastructure development for oil and gas, we’re almost seeing a one-quarter haircut that’s gone straight over into developing green resources.”

DR. DETLEF HALLERMANN clinical associate professor and director of the Reliant Energy Trade Center, Texas A&M University

Land Markets

Land prices, in ation, COVID-19, labor and resources shortages, and potential droughts are major headwinds for Texas’ land markets this year.

DR. CHARLES GILLILAND research economist, Texas Real Estate Research Center

DR. CHARLES GILLILAND research economist, Texas Real Estate Research Center

“People want to move to the small towns . . . if they can work remotely. So that’s driving up demand out in the country.”

DR. JAMES GAINES former chief economist, Texas Real Estate Research Center

Land Markets

Texas Land Markets

Legal Matters

What land is “jurisdictional” under WOTUS (and thus may be subject to federal regulation) is still uncertain and likely to remain so for the foreseeable future.

Market disruptors continue to challenge some business practices under antitrust laws. These cases are highly fact intensive, and courts vary on where to draw the line between good competitive business and anticompetitive conduct.

Texas Central Railway, which intends to build high-speed electric rail between Dallas and Houston, received a favorable holding from an appeals court regarding its eminent domain power. The case will be reviewed by the Supreme Court. Even if the company wins the case, it still has a ways to go to complete the project.

RUSTY ADAMS research attorney, Texas Real Estate Research Center

RUSTY ADAMS research attorney, Texas Real Estate Research Center

State Growth

The state’s population is projected to grow from 29 million now to almost 34 million by 2040.

DR. RONALD KAISER professor, Water Management & Hydrologic Science, Texas A&M University

DR. RONALD KAISER professor, Water Management & Hydrologic Science, Texas A&M University

Continuing changes to Texas’ climate and a growing population will impact water, energy, health, food, economy, and social equity. “This is going to be a real challenge for how resilient Texas is.”

DR. JAY BANNER

DR. JAY BANNER

F.M. Bullard Professor, Department of Geological Sciences, University of Texas

Water Management

“We have plenty of water. The bad news: it’s getting increasingly expensive.” Texas has $8 billion to spend on water projects.

Water use will increase from about 16-17 million acre-feet (MAF) today to 19 MAF by 2040.

DR. RONALD KAISER professor,

DR. RONALD KAISER professor,

Water Management & Hydrologic Science, Texas A&M University

Tax Issues

There is a declining risk of tax changes in Congress of any material kind for the remainder of 2022. For 2023 and 2024, Republicans are likely to control the House of Representatives and possibly the Senate, which will diminish the likelihood of tax changes unfavorable to real estate owners and investors.

WILLIAM D. ELLIOTT

tax attorney, Elliott, Thomason & Gibson LLP

WILLIAM D. ELLIOTT

tax attorney, Elliott, Thomason & Gibson LLP

The like-kind exchange is one of the most tax-favored transactions, but many technical requirements must be met for the exchange to work. Sellers are confronted with an array of risks that can lead to a failed exchange transaction, but they achieve the favorable tax bene ts of a like-kind exchange if they have good advisors and follow the rules. By William D. Elliott

Real estate professionals are likely familiar with the basic rules of like-kind exchanges, in which sellers of real property may defer the gain on the sale of real estate if they reinvest the sale proceeds in other like-kind real property (a similar property that can be exchanged without incurring any tax liability). The idea that a seller can defer potential gain from the sale of real estate by reinvesting into other real estate sounds like a great idea, at least at rst. Later, when mistakes occur, what seemed like an easy real estate swap becomes a nightmare. A failed exchange places the seller in a double bind. The seller has reinvested all of the sale proceeds from a sale into other property, but he still owes tax on gains from the sale.

An exchange of property can be simultaneous, but the seller typically hires an intermediary (called a “quali ed intermediary”) who acts as a middleman to facilitate the real estate

swap. The process usually goes like this. The seller sells a piece of property. The quali ed intermediary receives and holds the sale proceeds while the seller locates a replacement, like-kind, real property. Once a replacement property is found, the seller instructs the quali ed intermediary to purchase it. Essentially, the purpose of the quali ed intermediary is to avoid the seller having receipt of the sale proceeds. If the seller receives the sales proceeds of the rst property, she loses the bene ts of a like-kind exchange.

Under a like-kind exchange, the seller must identify replacement property within 45 days after the sale of the rst property (known as the identi cation period) and acquire the replacement property within 180 days after the sale (known as the replacement period), or sooner if the tax return is due.

The following mistakes are commonly seen in botched likekind exchanges.

Investment

MISTAKE #1

Waiting Too Late

Bene ting from a like-kind exchange takes advance planning. Real estate attorneys and title officers can talk for days about sellers who miss the opportunity to make a like-kind exchange by not realizing the opportunities until they arrive for closing.

When a seller walks into closing and realizes only then that she could have protected the gain on the sale by purchasing like-kind property, it is too late.

Failing to Identify Replacement Property Correctly and Timely MISTAKE #2

The seller has 45 days to identify replacement property— a short amount of time to identify, negotiate, underwrite, nance, and complete due diligence for the purpose of property.

Sellers commonly lose track of time and do not have a clear idea when the 45-day period ends. It begins on the date the seller sells his property and ends at midnight on the 45th day after that property is sold. The seller could fail to realize that the 45th day could end on a holiday or weekend. If he wishes to bene t from a like-kind exchange, he should mark speci c deadlines on a calendar.

Another common mistake is for a seller to identify only one replacement property, but then revoke the identi cation near the end of the 45-day period and miss the deadline. If there’s a possibility the seller might revoke an identi cation, he should leave ample time to select another potential replacement property before the deadline.

The seller is subject to two critical rules on identifying multiple replacement properties:

• the three-property rule, and

• the 200 percent rule (for more than three properties).

Under the three-property rule, the seller can identify up to three properties as potential replacement properties without any concern over the values of the properties. Under the 200 percent rule, the seller may name more than three potential replacement properties, but the combined value of those properties cannot exceed 200 percent of the value of the sold property.

The seller should plan for the likelihood that he will change his mind about a designated property and run over the 45-day limit by naming multiple potential replacement properties.

MISTAKE #3

Failing to Compute the Exchange Period Correctly

As previously discussed, the seller has 45 days to identify replacement property and 180 days to close on the purchase of the property. The exchange period begins on the date the seller transfers the relinquished property and ends at midnight on the 180th day. Usually that is ample time to close, but several problems can occur.

For instance, the 180th day could land on a holiday or weekend when title companies are closed, thus preventing the closing from happening. Another potential problem is the 180-day period can end early if the tax return for the year is due. The cut-off period for the tax return ling would mean an exchange that started late in the tax year could pose a risk if the seller les her tax return on March 15 or April 15.

electin a e an ualified ualified ntermediary

Participation in a like-kind exchange is not a time for working with amateurs, so sellers should use only a reputable and experienced quali ed intermediary. Unfortunately, the marketplace for quali ed intermediaries is unregulated, so it would be easy for the seller to select an inferior one.

The quali ed intermediary holds large sums of money, and there are highly publicized stories of less-than-scrupulous quali ed intermediaries mismanaging or even losing exchange funds. A seller whose exchange funds become unavailable faces not only losing the funds for the replacement purchase, but also a potential breach of contract lawsuit for failing to complete the exchange.

Participation in a like-kind exchange is not a time for working with amateurs, so sellers should use only a reputable and experienced qualified intermediary.

The quali ed intermediary requirements are formal and precise, and a qualied intermediary can take actions or cut corners that expose the seller to the risk of a botched like-kind exchange. Some have been known to play games with the identi cation rules by switching pages in the documentation to enable the seller to identify replacement property after the 45-day period expires. Sellers could face the risk of tax fraud if they play along with these scams. There are strict rules preventing a quali ed intermediary from distributing or making proceeds available to the seller before the end of the 45-day period.

Most reputable title companies or banks maintain a quali ed intermediary business staffed with competent personnel. In addition, there are many capable private quali ed intermediaries unaffiliated with a title company or bank. Some real estate attorneys also serve as quali ed intermediaries.

17 SUMMER 2022

MISTAKE #5

Relying on Amateur Intermediaries’ Tax Advice

Receiving awed tax advice from amateur intermediaries or nancial institutions is another common mistake. Taxpayers involved in a like-kind exchange are often tempted to follow advice from staff of the intermediary or from other nancial institutions, perhaps from someone who is neither an accountant nor an attorney but who nevertheless gives tax advice.

The tax requirements of a like-kind exchange are technical and require careful consideration. For example, a seller identifying a replacement property meets Treasury regulations only if the document identifying the replacement property is a “written document signed by the taxpayer and hand delivered, mailed, telecopied, or otherwise sent before the end of the identi cation period to either . . .” Is an email sufficient for this designation requirement? How is the email signed? Should DocuSign be employed to attach signatures to a document? Is the seller better off designating property with a signed document, converting it to a PDF le, then emailing the PDF? If there is a defect in the signature, such as a misspelling, is the document still acceptable? If there is no signature on the email other than the conventional email signature block, will the IRS or the courts respect it?

Again, these issues illustrate the technical nature of the exchange requirements, and taxpayers should rely on experienced and knowledgeable advisers, not amateur intermediaries or nancial institutions, for guidance.

Selling or Exchanging Property Not Held for Investment or Used in Trade or Business MISTAKE #6

One of the core rules of a like-kind exchange is that the property sold and the replacement property must both be investment properties or trade or business properties. Sellers make mistakes when they lose sight of these fundamental rules.

For example, personal-use property such as a residence will likely fail as transferred or replacement property. Sellers often try to convert residential or vacation property into investment property or trade or business property by offering it as a rental prior to an exchange. The IRS provides a safe harbor for exchanging or acquiring a second home or residential property in an exchange. One rule requires 24-month ownership before or after the exchange, minimizing personal use to 14 days or 10 percent of the number of days the property is rented at fair market value during the year.

Sellers wanting to include personal-use property in an exchange should proceed with caution.

MISTAKE #7

Trying to Exchange Property Held in a Partnership or LLC

Another common mistake occurs when sellers try to exchange property held by a partnership or LLC. The seller might be in a partnership or LLC with others, some of whom want to undertake a like-kind exchange, while others do not. A like-kind exchange concerns the exchange of real property, not partnership or LLC interests. If the seller wishes to exchange property held in a partnership or LLC, she should arrange for transfer of the property from the partnership or LLC and undertake the exchange acting as an individual owner.

MISTAKE #8

Acquiring Property from a Related Party

Sellers often attempt a like-kind exchange with a related party. Generally, this is ill-advised without attention to the detailed holding period rules. The IRS is concerned about nancial chicanery or parties playing games by dealing with related persons.

The like-kind exchange rules permit an exchange with a related party, but they impose a time requirement of 24 months. This means both the seller and the related party must hold title to the property acquired in the exchange for a minimum of 24 months. If either party disposes of the acquired property prematurely, both parties lose the favorable tax treatment of an exchange.

If a related party dies, the parties are relieved of the 24-month rule. The parties are not subject to the restriction if either experiences an involuntary conversion, such as a destruction of property by a severe storm.

The de nition of who is related is not straightforward. For individuals, related parties include a spouse, brothers, sisters, ancestors, and lineal descendants. If one owns more than a 50 percent interest in a corporation or partnership, then the corporation or partnership is the related party. There are many facets to identifying who is a related party, and sellers should proceed carefully.

Elliott (bill@wdelliottlaw.com) is a Dallas tax attorney, Board Certi ed, Tax Law; Board Certi ed, Estate Planning & Probate; Texas Board of Legal Specialization; and Fellow American College of Tax Counsel.

18 TG

LIQUIDATED DAMAGES CLAUSES

HOW DO THEY WORK?

Liquidated damages clauses are common in Texas real estate contracts, and they are generally enforceable. However, courts will not uphold the enforcement of a penalty. By Rusty Adams

Liquidated damages clauses are common in contracts dealing with Texas real estate. They are found in most sales contracts, whether residential, commercial, farm and ranch, or unimproved. They are found in many construction contracts. Really, a liquidated damages clause may be included in most any contract if the parties agree. Such provisions can provide advantages to the parties. However, they are not always enforceable by the courts.

19 SUMMER 2022 CONTRACT

Legal Issues

What are Liquidated Damages?

Liquidated, in the legal sense, means that a debt or dollar amount is settled or determined, especially by agreement. If damages are unliquidated, that means they cannot be determined by a xed formula and, instead, must be determined in some other way—usually by a judge or jury based on evidence presented at a trial. So “liquidated damages” means damages that are easily ascertained (e.g., in a suit on an account or a promissory note) or whose amount is xed by agreement of the parties to the transaction (e.g., in a liquidated damages clause).

In a liquidated damages clause, the parties to a contract stipulate in advance that in the event of a breach, the breaching party will pay the nonbreaching party a xed amount of money representing the loss sustained from the breach. Generally speaking, liquidated damages clauses are enforceable. As long as the agreement is enforceable, this provision furnishes the measure of damages for the breach.

The most common place for a liquidated damages clause involves the seller’s receiving of the earnest money as liquidated damages for the buyer’s default. It is common to see liquidated damages clauses in construction contracts, setting forth a speci c amount of damages for each day completion is delayed past a deadline.

Advantages of Liquidated Damages Provisions

Agreeing to liquidated damages clauses carries several advantages.

First, generally speaking, they allow the contracting parties to negotiate in advance amounts that the parties believe are fair based on the circumstances and the parties’ expectations at the time the contract is made.

Second, they provide certainty, at least to some extent, of what the parties’ potential liability or recourse will be.

Third, they can allow the parties to simplify their court cases or, better yet, avoid them altogether, saving or reducing the time and expense of litigation. Often in litigation, the biggest issue is determining the amount of damages, and the parties spend signi cant time, money, and effort preparing evidence of damages to present at trial. Instead of dealing with

these things in a courtroom after the fact, the parties simply agree to an amount they consider just compensation.

Of course, “the best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men gang aft agley.” Courts are supposed to uphold the freedom of contract, and ordinarily they give great deference to the agreement of the contracting parties. Courts like to say they cannot and will not rewrite contracts to relieve a party from a bad deal, but that is not necessarily so. Courts sometimes make exceptions to that rule, and liquidated damages clauses undergo judicial scrutiny.

Are Liquidated Damages Clauses Enforceable?

As stated before, the parties to a contract agree at the time of contracting that the liquidated clause supplies the measure of damages. However, these clauses may be challenged in court. Is such an agreement enforceable? Generally, yes. But as

with so many other questions in law, the answer is, “It is until it’s not.”

The reason for this lies in the theoretical underpinnings of contractual damages. Contract damages are generally supposed to compensate the injured party for losses actually incurred. They are not intended to discourage a party from breaching a contract, to compel a party to perform its promises, or to punish a party for breaching. For this reason, liquidated damages clauses that estimate in advance a party’s just compensation for another party’s breach are considered valid, while those that are designed to secure a party’s performance or punish a party’s nonperformance are considered unenforceable penalties.

Courts generally interpret and enforce contracts based on the intent of the parties as determined by examining the actual language of the contract, giving the words their plain meaning, in most cases. The entire contract is considered as a whole.

20 TG

The use of the terms “liquidated damages” or “penalty” may be considered in determining intent but is not conclusive.

The assertion that a liquidated damages clause is an unenforceable penalty is considered an affirmative defense and, as such, the party attempting to avoid enforcement must plead and prove that it is unenforceable. Whether a liquidated damages clause is enforceable or not is a question of law to be decided by a judge.

The general rule for determining enforceability was announced in Stewart v. Basey, 150 Tex. 666, 245 S.W.2d 484 (1952). To be enforceable, the clause must meet two requirements. First, the amount must be a reasonable forecast of just compensation for the damages caused by the breach. Second, the damages must be impossible or difcult to estimate accurately. Both prongs of the test are to be evaluated from the perspective of the parties at the time of making the contract. There is no formula

for determining the reasonableness of the amount. It appears to be entirely at the whim of the court. The court may consider mitigation of damages in its reasonableness analysis.

Over the years, different courts in various jurisdictions have struggled with the reasonableness of the liquidated damages amount and whether it should be evaluated from the perspective of the contracting parties or by comparing the estimate to the actual harm after the fact.

The Texas Supreme Court essentially announced a new requirement in FPL Energy, LLC v. TXU Portfolio Mgmt. Co., L.P., 426 S.W.3d 59 (Tex. 2014). The court stated the rule that evaluation of reasonableness is made from the perspective of the parties when entering the contract. Nevertheless, in evaluating the reasonableness of the damage forecast, the court observed an “unacceptable disparity” and “unbridgeable discrepancy” between the amount of damages estimated and

agreed on in the clause and the “unfortunate reality in application.” Thus, the court held the provision unenforceable. The Supreme Court restated this rule in Atrium Med. Ctr., LP v. Houston Red C LLC, 595 S.W.3d 188 (Tex. 2020), and this requirement appears to be here to stay, despite the court’s assertion that it has not modi ed the rule.

Interestingly, if such clauses are litigated, this rule can negate some reasons for having a liquidated damages clause in the rst place. If such clauses must be litigated, the goals of avoiding litigation and avoiding having to prove actual damages will be frustrated. In the event the clause is ruled an unenforceable penalty, actual damages must be shown in order for the party to recover those damages.

If a party relies on the liquidated damages clause alone and makes no showing of actual damages, that party may not recover if the court refuses to enforce the clause. Likewise, a party attempting to avoid enforcement of the clause must now prepare and present evidence of actual damages and/or the effects of the operation of the clause.

Drafting Considerations

The enforcement decisions of the courts leave some uncertainty when drafting liquidated damages clauses. Nevertheless, steps can be taken to include an enforceable liquidated damages clause.

First, there should be a recital that the parties agree that actual damages would be difficult or impossible to calculate. Additionally, there should be an agreement to an amount or a formula by which an amount may be calculated, and a recital that the parties agree that the amount or formula reasonably estimates actual damages in the event of a breach. The parties should avoid listing a single, speci c liquidated damages amount that applies regardless of the nature of the breach. While none of these is a magic bullet, they can assist a court in upholding the clause.

Nothing in TG should be considered legal advice. For advice or representation on speci c legal matters, readers should retain an attorney.

Adams (r_adams@tamu.edu) is a member of the State Bar of Texas and a research attorney for the Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University.

21 SUMMER 2022

School Daze

Residential

School Daze

Author’s note: This article is not an endorsement of any political argument regarding student loan debt forgiveness. It is simply intended to illustrate the impact student loan debt can have on an individual’s ability to purchase a home.

M Challenges

Younger Homebuyers

Student loan debt could affect a household’s ability to acquire home financing. It could reduce the household’s ability to save, extending how long it takes to save up for a

Many obstacles stand in the way of homebuying, particularly for rst-time buyers: historically high home-price appreciation, strong demand for homeownership amidst a limited supply of homes for sale, tightened mortgage credit availability, and now rising mortgage interest rates. But for many younger households, there’s yet another obstacle: student loan debt.

home.

By Clare Losey

A 2021 poll by the National Association of Realtors found that 60 percent of non-homeowning millennials (individuals between the ages of 26 and 41) cited student loan debt as a hurdle to purchasing a home. Two- fths of millennial homeowners reported student loan debt delayed their home purchase by at least three years.

Being a credit risk to lenders can hinder homeownership. Student loan debt makes mortgage applicants more of a credit risk by increasing their back-end debt-to-income (DTI) ratio (total measure of household debt), constraining their ability to save, and lowering their credit score if they miss student loan

homeowners reported student loan debt delayed their home payments.

All other conditions being the same, a higher DTI and loan-to-value (LTV) ratio and/or lower credit score may reduce an applicant’s chances of receiving a mortgage loan, depending on the level of credit risk the lender deems “acceptable.” If a higher-risk applicant is approved, the lender is likely to impose additional costs of borrowing, such as a mortgage insurance premium or other points and fees, to compensate

for the higher risk.

Millennials entered the housing market during a particularly turbulent time in the U.S. economy. The Great Recession occurred when the oldest millennials were 26 to 28 years old, meaning a sizeable portion of them graduated from college into a weak labor market. This had two primary effects: it reduced the potential earnings of millennials who went to work, and it incentivized millennials to return to school, potentially incurring more student loan debt.

Meanwhile, tuition continues to rise, leaving millennials with more student loan debt, on average, than previous

als with more student loan debt, on average, than previous generations.

SUMMER 2022

The Institute for College Access and Success reported that 52 percent of undergraduate students at four-year universities in Texas graduated with student loan debt in 2019-20, carrying an average balance of $26,273. Interest rates on student loans vary considerably depending on the rst disbursement date of the loan and whether the loan is federal or private.

The monthly loan payment increases as the total debt balance and the interest rate increase (Table 1). A direct subsidized student loan had an interest rate of 4.5 percent from July 2019 to June 2020, amounting to a $273 monthly payment for borrowers carrying the average debt balance.

Impact on Borrower’s Total Debt

As the monthly student loan payment increases, student loan debt consumes a larger percentage of household income (Table 2). If the loan payment doesn’t increase, student loan debt as a percentage of total household income decreases as household income increases. Student loan debt as a percentage of household income varies from 3.3 percent to 10.9 percent for the average monthly student loan payment of $273.

A household earning $60,000 annually with no student loan debt has a

Source: Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas

back-end DTI ratio of 37.9 percent (Table 3). The ratio for the same household with the average monthly student loan payment is 43.3 percent, just exceeding the maximum ceiling on qualifying ratios (43 percent) stipulated by the Dodd-Frank Act. Mortgage owners with higher back-end DTI ratios (in other words, less residual income) are more likely to have difficulty repaying mortgages should they lose their jobs, see a drop in their incomes, or incur signi cant costs from an unexpected nancial event.

Table 1. Monthly Student Loan Payment by Total Student Loan Debt, Interest Rate Total Debt Interest Rate 3%4%4.529%5%6%7%8% $5,000$48 $51 $52 $53 $56 $58 $61 $10,000$97 $101 $104 $106 $111 $116 $121 $15,000$145 $152 $156 $159 $167 $174 $182 $20,000$193 $202 $208 $212 $222 $232 $243 $25,000$241 $253 $259 $265 $278 $290 $303 $26,273$254 $266 $273 $279 $292 $305 $319 $30,000$290 $304 $311 $318 $333 $348 $364 $35,000$338 $354 $363 $371 $389 $406 $425 $40,000$386 $405 $415 $424 $444 $464 $485 $45,000$435 $456 $467 $477 $500 $522 $546 $50,000$483 $506 $519 $530 $555 $581 $607 Source: Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

Monthly Student Loan Payment Annual Household Income $30,000$40,000$50,000$60,000$67,635$70,000$80,000$90,000$100,000 $0 0%0%0%0%0%0%0%0%0% $50 2.0%1.5%1.2%1.0%0.9%0.9%0.8%0.7%0.6% $100 4.0%3.0%2.4%2.0%1.8%1.7%1.5%1.3%1.2% $150 6.0%4.5%3.6%3.0%2.7%2.6%2.3%2.0%1.8% $200 8.0%6.0%4.8%4.0%3.5%3.4%3.0%2.7%2.4% $250 10.0%7.5%6.0%5.0%4.4%4.3%3.8%3.3%3.0% $273 10.9%8.2%6.6%5.5%4.8%4.7%4.1%3.6%3.3% $300 12.0%9.0%7.2%6.0%5.3%5.1%4.5%4.0%3.6% $350 14.0%10.5%8.4%7.0%6.2%6.0%5.3%4.7%4.2% $400 16.0%12.0%9.6%8.0%7.1%6.9%6.0%5.3%4.8% $450 18.0%13.5%10.8%9.0%8.0%7.7%6.8%6.0%5.4% $500 20.0%15.0%12.0%10.0%8.9%8.6%7.5%6.7%6.0% $550 22.0%16.5%13.2%11.0%9.8%9.4%8.3%7.3%6.6% $600 24.0%18.0%14.4%12.0%10.6%10.3%9.0%8.0%7.2%

Table 2. Student Loan Debt as Percentage of Household Income

University

A&M

STUDENT LOAN DEBT CAN CONSUME anywhere from 3.3 to 10.9 percent of the average Texas college graduate's income, making it harder to qualify for a mortgage or save for a down payment.

otes he back end I ratio represents total household debt to household income. or this analysis total household debt includes only mortgage debt and student loan debt. The analysis assumes a 5 percent mortgage interest rate, a mortgage insurance premium of 0.5 percent, a 30-year loan term, a 95 percent LTV ratio, property taxes and insurance equal to percent of home price and a home purchase price of the first quartile sales price in exas in . igures in red indicate the back end I ratio exceeds percent the qualifying ratio imposed by the odd rank ct. hile lenders may still be willing to originate loans to applicants whose back end I ratio exceeds percent the applicant will likely need to present compensatory factors such as certain amount in cash reserves and sufficient residual income.

Source: Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

Monthly Student Loan Payment Annual Household Income $30,000$40,000$50,000$60,000$67,635$70,000$80,000$90,000$100,000 $0 75.8%56.8%45.5% 37.9%33.6%32.5%28.4%25.3%22.7% $50 77.8%58.3%46.7% 38.9%34.5%33.3%29.2%25.9%23.3% $100 79.8%59.8%47.9% 39.9%35.4%34.2%29.9%26.6%23.9% $150 81.8%61.3%49.1% 40.9%36.3%35.0%30.7%27.3%24.5% $200 83.8%62.8%50.3% 41.9%37.1%35.9%31.4%27.9%25.1% $250 85.8%64.3%51.5% 42.9%38.0%36.8%32.2%28.6%25.7% $273 86.7%65.0%52.0%43.3% 38.4%37.1%32.5%28.9%26.0% $300 87.8%65.8%52.7%43.9% 38.9%37.6%32.9%29.3%26.3% $350 89.8%67.3%53.9%44.9% 39.8%38.5%33.7%29.9%26.9% $400 91.8%68.8%55.1%45.9% 40.7%39.3%34.4%30.6%27.5% $450 93.8%70.3%56.3%46.9% 41.6%40.2%35.2%31.3%28.1% $500 95.8%71.8%57.5%47.9% 42.5%41.0%35.9%31.9%28.7% $550 97.8%73.3%58.7%48.9%43.4% 41.9%36.7%32.6%29.3% $600 99.8%74.8%59.9%49.9%44.2% 42.8%37.4%33.3%29.9%

Table 3. Back-End DTI Ratio by Annual Household Income, Monthly Student Loan Payment

FOR GRADUATES EARNING the median income for those aged 25 to 44 and paying the average monthly student loan payment amount, it will take just over three years to save enough for a 5 percent down payment on a $217,000 home.

As student loan debt as a percentage of household income increases, the home price-to-income multiplier decreases (Table 4). The home price-to-income multiplier is the maximum home price affordable to a particular household. Depending on the household’s income, the maximum home price affordable to a household with the average monthly student loan payment decreases by 8.3 percent to 34 percent compared with a household without student loan debt. For those earning the median income for householders aged 25 to 44 in 2020 ($67,635), the maximum home price affordable to a household with the average monthly student loan payment decreases by 12.7 percent compared with a household without student loan debt.

Households’ Ability to Save

The size of a down payment on a home varies greatly by home price and LTV ratio (Table 5).

In 2021, the rst-quartile sales price was $217,000. First-time buyers tend to have higher LTV ratios (usually between 90 and 100 percent, depending on the type of loan) than repeat buyers, who are generally older and further along in the labor cycle. A buyer who obtains a mortgage loan with an LTV ratio of 90 percent would need at least $21,700 in savings to afford the down payment. At an LTV ratio of 98 percent, that drops to $4,340.

STable 4. Relationship Between Student Loan Debt, Household Affordability

ote his analysis assumes a maximum back end I ratio of percent percent mortgage interest rate, mortgage insurance premium of 0.5 percent, 30-year loan term, 95 percent LTV ratio, and property taxes and insurance at 4 percent of home price.

Source: Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

tudent loan debt makes it harder to save. A household’s savings is a direct function of its disposable income and personal savings rate, or savings rate after taxes. Savings increases as annual income and the person’s personal savings rate increase. According to the Federal Reserve Economic Data, the personal savings rate averaged 7.64 percent in 2019 for all Americans (the rate for 2021 and 2021 was positively skewed by economic impact payments). Younger households may have lower savings rates than older households, because younger households generally have lower incomes and, therefore, less disposable income. Households anticipating a signi cant purchase, such as a home, in the near future may be inclined to increase their savings rate.

Home Price

Loan-to-Value Ratio

80%90%95%96.5%98% $150,000$30,000$15,000$7,500$5,250$3,000 $175,000$35,000$17,500$8,750$6,125$3,500 $200,000$40,000$20,000$10,000$7,000$4,000 $217,000$43,400$21,700$10,850$7,595$4,340 $225,000$45,000$22,500$11,250$7,875$4,500 $250,000$50,000$25,000$12,500$8,750$5,000 $275,000$55,000$27,500$13,750$9,625$5,500 $300,000$60,000$30,000$15,000$10,500$6,000 $325,000$65,000$32,500$16,250$11,375$6,500 $350,000$70,000$35,000$17,500$12,250$7,000 $375,000$75,000$37,500$18,750$13,125$7,500 $400,000$80,000$40,000$20,000$14,000$8,000

Source: Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

Table 5. Cost of Down Payment by Home Price, LTV Ratio

Table 5. Cost of Down Payment by Home Price, LTV Ratio

Student Loan Debt as a Percentage of Household Income Home Price-to-Income Multiplier 0% 4.11 2.5% 3.87 5% 3.63 7.5% 3.39 10% 3.15 12.5% 2.91 15% 2.67 17.5% 2.43 20% 2.20

Assuming a savings rate of 10 percent, a household earning the median income for households aged 25 to 44 in 2020 ($67,635) would save $6,764 annually without any student loan debt (Table 6) but nearly half that—$3,488— with the average monthly student loan payment ($273). This nearly doubles the time to save for a 5 percent down payment on a $217,000 home (the rst-quartile sales price in 2021) from 1.6 years to 3.1 years (Table 7).

The effect is more signi cant among lower-income households. Without any student loan debt, a household earning $50,000 annually could expect to save just over two years for the down payment on a $217,000 home. That increases to six years if the household carries the average student loan payment.

Dr. Losey (clare_losey@tamu.edu) is an assistant research economist with the Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University.

$0$1,000$2,000$3,000$3,764$4,000$5,000$6,000$7,000

-$276 $724$1,724$2,724$3,488$3,724$4,724$5,724$6,724

-$600 $400$1,400$2,400$3,164$3,400$4,400$5,400$6,400

-$1,200-$200 $800$1,800$2,564$2,800$3,800$4,800$5,800

$550 -$3,600-$2,600-$1,600-$600 $164$400$1,400$2,400$3,400

$600 -$4,200-$3,200-$2,200-$1,200-$437-$200 $800$1,800$2,800 ote egative values highlighted in red indicate the household does not earn sufficient income to save with its student loan debt burden. In other words the household is incurring more debt.

Source: Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

igure

Monthly Student Loan Payment Annual Household Income $30,000$40,000$50,000$60,000$67,635$70,000$80,000$90,000$100,000 $0 3.62.72.21.81.61.61.41.21.1 $50 4.53.22.52.01.81.71.51.31.2 $100 6.03.92.92.32.01.91.61.41.2 $150 9.04.93.42.62.22.11.81.51.3 $200 * 6.84.23.02.52.41.91.61.4 $250 * 5.43.62.92.72.21.81.6 $273 * 6.34.03.12.92.31.91.6 $300 * 7.84.53.43.22.52.01.7 $350 * 6.04.23.92.92.31.9 $400 * 9.05.54.93.42.62.1 $450 * 8.06.84.23.02.4 $500 * * 5.43.62.7 $550 * * 7.84.53.2 $600 * 6.03.9

Table 7. Years to Save for 5

Percent

Down Payment on First-Quartile Sales Price in 2021 ($217,000)

Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

exceeds the assumed loan term years for student loan debt. Source: Texas

Monthly Student Loan Payment Annual Household Income $30,000$40,000$50,000$60,000$67,635$70,000$80,000$90,000$100,000 $0 $3,000$4,000$5,000$6,000$6,764$7,000$8,000$9,000$10,000 $50 $2,400$3,400$4,400$5,400$6,164$6,400$7,400$8,400$9,400 $100 $1,800$2,800$3,800$4,800$5,564$5,800$6,800$7,800$8,800 $150 $1,200$2,200$3,200$4,200$4,964$5,200$6,200$7,200$8,200 $200 $600$1,600$2,600$3,600$4,364$4,600$5,600$6,600$7,600

$273

$400

$200$1,200$1,964$2,200$3,200$4,200$5,200 $450

$600$1,364$1,600$2,600$3,600$4,600 $500

$0$764$1,000$2,000$3,000$4,000

Table 6. Total Monthly Savings by Annual

Income,

Monthly Student Loan Payment

$250

$300

$350

-$1,800-$800

-$2,400-$1,400-$400

-$3,000-$2,000-$1,000

Q. The listing agent says the seller does not have to ll out a seller disclosure because the seller has not lived there in the last three years. Is that true?

A. No. This is a common misconception. The Texas Property Code has 11 exceptions to the seller disclosure law. Not living in the home is not one of those exceptions.

Q. I represent an heir to a property. Does she have to give a buyer a Seller’s Disclosure Notice?

A. It depends. If the property is sold during estate administration by the executor, the answer is no because the executor is exempt by law. If the property is sold after the estate is probated and title has transferred to your client, then the answer is yes

What the Law Says

The Seller’s Disclosure Notice is required when transferring residential real property with only one dwelling unit except:

• pursuant to a court order or foreclosure sale;

• by a trustee in bankruptcy;

• to a mortgagee by a mortgagor or successor in interest, or to a bene ciary of a deed of trust by a trustor or successor in interest;

• by a mortgagee or a bene ciary under a deed of trust who has acquired the real property at a sale conducted pursuant to a power of sale under a deed of trust or a sale pursuant to a court-ordered foreclosure or has acquired the real property by a deed in lieu of foreclosure;

• by a duciary in the course of the administration of a decedent’s estate, guardianship, conservatorship, or trust;

• from one co-owner to one or more other co-owners;

• when made to a spouse or to a person or persons in the lineal line of consanguinity (kinship) of one or more of the transferors;

• between spouses resulting from a decree of dissolution of marriage or a decree of legal separation or from a property settlement agreement incidental to such a decree;

• to or from any governmental entity;

• for a new residence of not more than one dwelling unit that has not previously been occupied for residential purposes; or

• for real property where the value of any dwelling does not exceed 5 percent of the value of the property [Texas Property Code §5.008(e)].

For Example

Jolene has a listing appointment with a seller who is an investor and has never lived in the home. At the appointment, she gives the seller an Information About Brokerage Services form, a listing agreement, and a seller disclosure form, and explains the need for each document. The seller pushes back on the seller disclosure form. He insists that he does not have to ll this out because he never lived in the property. Jolene assures him that in Texas this is required and “not having lived there” is not an exception. The seller says he bets he

All agents should know what the law says about when a seller’s disclosure form is required or not. Brokers should train agents on this. Keep in mind, all sellers and license holders must

can nd an agent who won’t make him ll out this silly form. Jolene has been in the business for a long time, and she knows when things start out in a negative way, they will likely get worse, not better. Jolene politely tells the seller, “Perhaps I am not the right agent for you.” The seller changes his tune because he knows she is the top listing agent in the area. He apologizes for his behavior and promises to get out his le on the property and ll out the disclosure based on the reports from his property manager.

Best Practice

disclose all knowledge about a material defect with the property, whether a Seller’s Disclosure Notice is required or not, or they could be sued under the Deceptive Trade Practices Act.

Nothing in this publication should be construed as legal advice for a particular situation. For speci c advice, consult an attorney. Lewis (kerrilewis13@gmail.com) is a member of the State Bar of Texas and former general counsel for the Texas Real Estate Commission (TREC). Wukasch (avis@2oldchicks.com) is a broker and former TREC chair.

28 TG

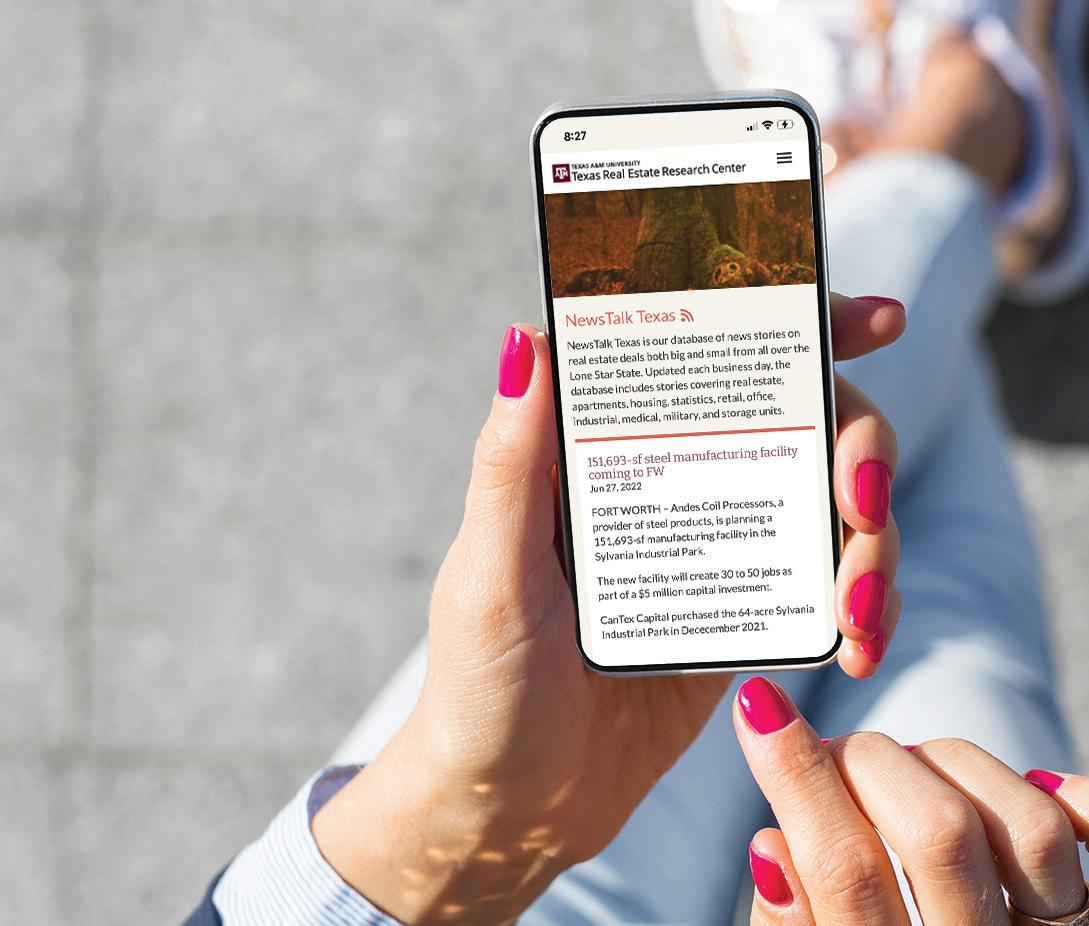

NewsTalk Texas is our online daily dose of real estate news and transactions covering all Texas markets. It’s convenient, portable, and searchable by Metropolitan Statistical Area, topic, and keyword. Helping Texans make the best real estate decisions since 1971. Start your day informed with NewsTalk Texas

DR. JAMES GAINES former chief economist, Texas Real Estate Research Center

DR. JAMES GAINES former chief economist, Texas Real Estate Research Center

DR. CHARLES GILLILAND research economist, Texas Real Estate Research Center

DR. CHARLES GILLILAND research economist, Texas Real Estate Research Center

RUSTY ADAMS research attorney, Texas Real Estate Research Center

RUSTY ADAMS research attorney, Texas Real Estate Research Center

DR. RONALD KAISER professor, Water Management & Hydrologic Science, Texas A&M University

DR. RONALD KAISER professor, Water Management & Hydrologic Science, Texas A&M University

DR. JAY BANNER

DR. JAY BANNER

WILLIAM D. ELLIOTT

tax attorney, Elliott, Thomason & Gibson LLP

WILLIAM D. ELLIOTT

tax attorney, Elliott, Thomason & Gibson LLP

Table 5. Cost of Down Payment by Home Price, LTV Ratio

Table 5. Cost of Down Payment by Home Price, LTV Ratio