President | Ritchie Bryant, MS, CDI, CLIP-R

Vice President | Dr. Jesús Rēmigiō, PsyD, MBA, CDI

Secretary | Jason Hurdich, M.Ed, CDI

Treasurer | Kate O’Regan, MA, NIC

Member-at-Large | Traci Ison, NIC, NAD IV

Deaf Member-at-Large | Glenna Cooper, PDIC

Region I Representative | Christina Stevens, NIC

Region II Representative | M. Antwan Campbell, MPA, Ed:K-12

Region III Representative | Shawn Vriezen, CDI, QMHI

Region IV Representative | Justin “Bucky” Buckhold, CDI

Region V Representative | Jeremy Quiroga, CDI

Chief Executive Officer | Star Grieser, MS, CDI, ICE-CCP

Chief Operating Officer | Elijah Sow

Operations Project Coordinator | Kirsten Swanson

Human Resources Manager | Cassie Robles Sol

CMP Manager | Ashley Holladay

CMP Specialist | Kayla Marshall

EPS Manager | Tressela Bateson

EPS Specialist | Martha Wolcott

Certification Manager | Catie Purrazzella

Certification Specialist | Jess Kaady

Director of Member Services | Ryan Butts

Member Services Specialist | Vicky Whitty

Director of Government Affairs | Neal Tucker

Affiliate Chapter Liaison | Dr. Carolyn Ball, CI and CT, NIC

Director of Communications | JJ Johnson

Web and Production Manager | Jenelle Bloom

Publications Manager | Estefani Garrison

Director of Finance and Accounting | Jennifer Apple

Finance and Accounting Manager | Kristyne Reeds

Staff Accountant | Bradley Johnson

The Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) strives to advocate for best practices in interpreting, professional development for practitioners and for the highest standards in the provision of interpreting services for diverse users of languages that are signed or spoken.

By honoring its past and innovating for the future, RID envisions a world where:

Its members recognize and support the linguistic rights of all Deaf people as human rights, equal to those of users of spoken languages;

Deaf people and their values are vital to and visible in every aspect of RID;

Interpreted interaction between individuals who use signed and spoken languages are as viable as direct communication;

The interpreting profession is formally recognized and is advanced by rigorous professional development, standards of conduct, and credentials.

RID understands the necessity of multicultural awareness and sensitivity. Therefore, as an organization, we are committed to diversity both within the organization and within the profession of sign language interpreting.

Our commitment to diversity reflects and stems from our understanding of present and future needs of both our organization and the profession. We recognize that in order to provide the best service as the national certifying body among signed and spoken language interpreters, we must draw from the widest variety of society with regards to diversity in order to provide support, equality of treatment, and respect among interpreters within the RID organization.

Therefore, RID defines diversity as differences which are appreciated, sought, and shaped in the form of the following categories: gender identity or expression, racial identity, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, Deaf or hard of hearing status, disability status, age, geographic locale (rural vs. urban), sign language interpreting experience, certification status and level, and language bases (e.g., those who are native to or have acquired ASL and English, those who utilize a signed system, among those using spoken or signed languages) within both the profession of sign language interpreting and the RID organization.

To that end, we strive for diversity in every area of RID and its Headquarters. We know that the differences that exist among people represent a 21st century population and provide for innumerable resources within the sign language interpreting field.

In the current RID Views, you will find various discussions related to education.

When I see the word “education,” it has a broad meaning. It could mean my receiving an education, providing an education, and advocating for an education. It could also mean many more things.

RID has started being active in making a change; frequently, people feel hesitant and fearful of any change. This fear often could inhibit change, and education helps to reduce anxiety. Through education, we can find many potential paths toward achievement. Once we learn about something, our fears ease and even fade away. It is crucial to have education, which will help us,

remaining solely focused within ourselves and experiencing what I call an “echo chamber.” An echo chamber causes vicious cycles of conflicts and problematic issues.

the board, start planning toward change. However, before any change can happen, we must learn, research, and discover the information out there. The more we research, the more we understand that the RID’s vision of change is not unique. Indeed, many other associations, including similar certification-granting associations, are doing the same things as RID. Their change process parallels what RID is doing now. We cannot dismiss that,

other associations went through the process of change and succeeded, we owe ourselves to step out of our box, investigate and learn from them. We can bring their experience and knowledge into our organization. When the process has already been done elsewhere, there is no point in reinventing the wheel. We must be more aggressive in seeking ways we can learn to build our foundations solidly, which occurs through education. We should not limit our focus to changes in our organizational structure but also learn more about our interpreting profession as a whole since it’s constantly changing.

If

Ritchie Bryant, MS, CDI, CLIP-R Board President

“This fear often could inhibit change, and education helps to reduce anxiety.”

“The more we research, the more we understand that the RID’s vision of change is not unique.”

“We should not limit our focus to changes in our organizational structure but also learn more about our interpreting profession as a whole since it’s constantly changing.”

There is emerging research showing that our interpreting profession is continuing to evolve. There are no longer fixed ways of doing things; instead, methods are starting to blend, borrowing from each other to do what’s best for their area. So that means we, as interpreters, must seek out education, which will only help us develop and make outstanding contributions to the development of our profession.

Technology, for instance, has a significant impact on the interpreting field. It has reached the point where interpreters can work from their home. They can take online courses and better themselves. Online education will contribute toward the transformation of how we provide our services. Indeed, we must improve our ability to deliver our services.

That shows the value of education.

“Online education will contribute toward the transformation of how we provide our services”Grieser, MS, CDI, ICE-CCP Chief Executive Officer

We’re heading into the holiday season, and what marks one of my favorite things this time of the year after all the festivities is the new year. New beginnings, new possibilities, and new growth are on the horizon. This fall, we have spent considerable time gearing up for these things. We have been conducting organizational assessments, drafting our strategic plan, hosting board retreats, conference and communications planning, and nailing down our plan of action as we nudge RID towards becoming closer to the great organization that our members want, that the profession needs, and what our Deaf community needs. One of the major ways we did this was by establishing our Mission, Purpose, Vision and Values (MPVV) for RID.

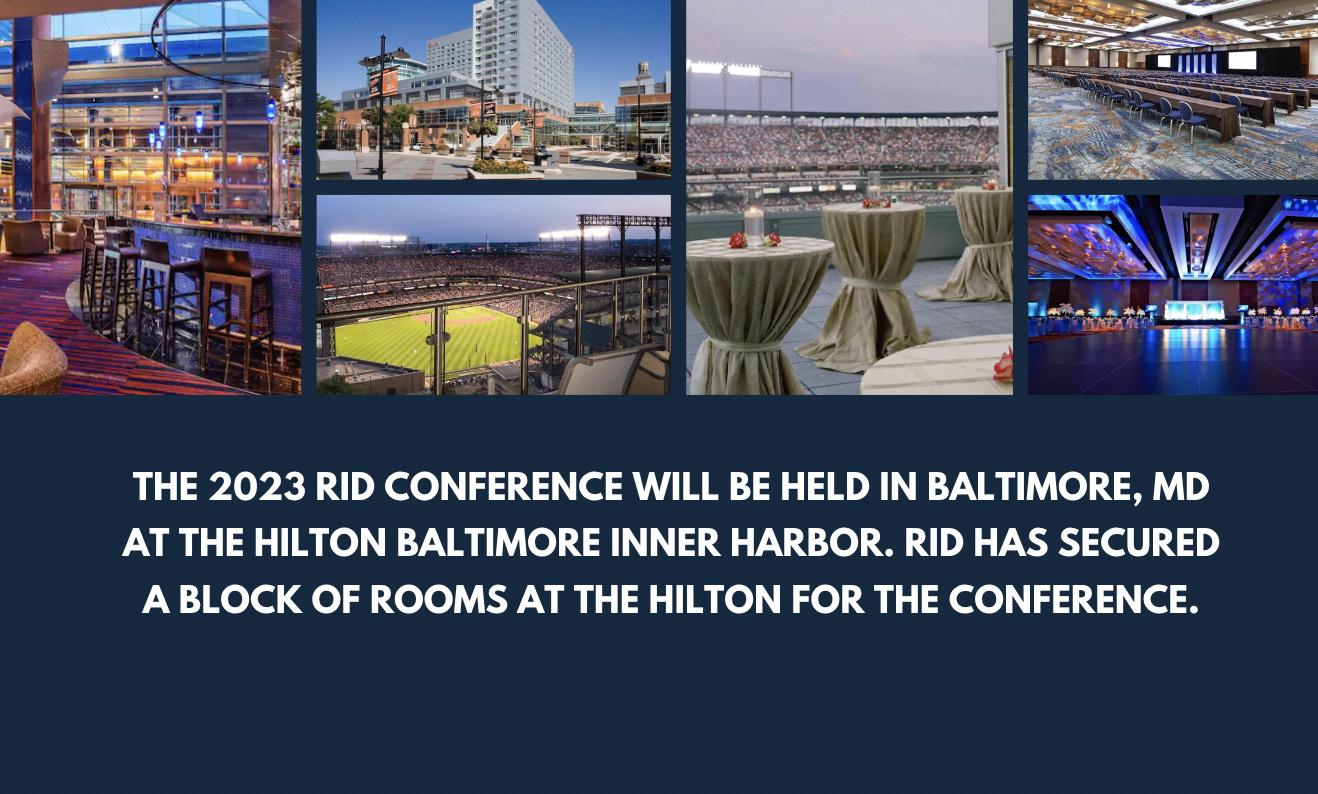

meeting and retreat, the Board focused on writing and finalizing the Board’s MPVV and RID’s next three-year Strategic Plan. President Bryant and I have begun sharing the MPVV – which is still being finalized – at our sister organizations, the Conference of Interpreter Trainers (CIT)’s biennial conference, and with members at state affiliate chapter conferences and the AC President’s Council. We will continue to discuss our MPVV and aligned work at virtual town halls this spring, at any conferences we’re invited to, and of course, at our national conference in Baltimore, Maryland, in July 2023. We want our members and stakeholders to understand and support our mission, purpose, vision and values.

Before I go further – to clarify, the board drafted the Mission, Purpose, Vision, and Values to sort of fine-tune our trajectory forward. The MPVV must absolutely be in alignment with RID’s purpose as outlined in our Articles of Incorporation (AOI), written back in 1973, and with the objectives of RID as spelled out in our bylaws. Nothing is in contradiction – two similar but somewhat differing statements can be mutually true. The AOI, the bylaws, and the Board’s MPVV can – and do – complement each other. Two months ago, at our October extended board

When I’m asked by someone outside of our profession and unfamiliar with Deaf culture and the world of communication access, “So, what is RID?” I reply: “RID is the national certifying body of sign language interpreters and is a professional organization that fosters the growth of the profession and the professional growth of interpreting.“ It really is that straightforward. This statement is our mission – what the

is.

But it gets more nuanced when we delve into what we really do and why we do it. What’s our purpose? Who do we serve? Why do we do what we do? “RID’s

organizationStar

What Does Change Mean For RID?Video CEO Report ASL Video

“The board drafted the Mission, Purpose, Vision, and Values to sort of fine-tune our trajectory forward.”

“We want our members and stakeholders to understand and enroll in our mission, purpose, vision and values.”

purpose is to serve equally our members, profession, and the public by promoting and advocating for qualified and effective interpreters in all spaces where intersectional diverse Deaf lives are impacted.”

Yes, we are serving our members, the profession and the public. But why do that? Why are we doing these things? Through these groups, we reach our ultimate purpose - serving intersectional diverse Deaf lives through our advocacy and our work toward upholding the standards for qualified and effective interpreters. This purpose is why we exist as an organization.

Now, the Board’s vision for RID is: “We envision qualified interpreters as partners in universal communication access and forward-thinking, effective communication solutions while honoring intersectional diverse spaces”. If you think about it, this statement is a vision of shared accountability in our work. This vision is RID taking the lead, our members taking part in advocacy efforts, and collaborating – as accomplices – with our consumers and stakeholders.

The values statement encompasses what lies at our work’s “heart” or the center. We could value selfinterest, but we don’t and shouldn’t. Anyone who serves in a leadership role will agree that our work within this industry and in this organization is a call to achieve and serve something much greater than our individual selves. RID values:

• Honoring the intersectionality and diversity of the communities we serve.

• Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Accessibility and Belonging (DEIAB).

• The professional contribution of volunteer leadership.

• The adaptability, advancement, and relevance of the interpreting profession.

• Ethical practices within the field of sign language interpreting, and embraces the principle of “do no harm.”

• Advocacy for the right to accessible, effective communication.

So while the MPVV answers what we do, why we do what we do, what we aim to achieve and what our values are, we have a responsibility to lay out a map of how to achieve our goals. Otherwise, our MPVV is

meaningless. This roadmap brings us to our strategic plan. The four major pillars of our strategic plan as we work to strengthen our organization and our relationships with others are:

• Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Accessibility, and Belonging initiatives in all aspects of planning. This value addresses and seeks remedies for systemic inequity, prejudice and discrimination throughout all facets of RID from leadership, headquarters staff, affiliate chapters, membership, the profession, and stakeholders. Also, to mindfully become aware of and address accessibility issues within our profession and to work towards creating a sense of welcome and belonging among members and consumers.

• Organization Transformation to bring RID into compliance with best practices for certification organizations and professional membership societies, in alignment with appropriate business models for member and organizational needs, and, of course, with NCCA (National Commission of Certifying Agencies) accreditation to champion the value of our certification for all stakeholders, members, and consumers.

• Organization Relevance. RID needs to clarify and solidify our message and purpose, strengthen our relationships with sister organizations and take our “seat at the table” in terms of collaborative advocacy activities, outreach and education, provision of resources and publications for our stakeholders, our members, and the public.

• Organization Effectiveness. This value is where leadership in RID – both the board and within RID HQ – takes a good, hard look at what works within our organization and what needs attention for improved efficiency and effectiveness. We are still finalizing the details of our strategic plan and devising an evaluation plan to flesh out our metrics for measuring progress in each of these areas. In the coming months and VIEWS magazine issues, I will be expounding on each of these four pillars and evaluation plan, and how they translate to working towards making RID the best possible organization for sign language interpreters. Together, we will elevate RID and the profession to the level where we all have desired and needed it to be.

Carolyn:Hi, my name is Dr. Carolyn Ball, and I am the RID affiliate Chapter Liaison. Every quarter RID publishes its organizational magazine called the VIEWS. I’m lucky enough to have an article in the views called the Affiliate Chapter Corner. This month I am very excited to have Hope Diehl with us, and she is the current president of Florida RID. So, Hope would you introduce yourself?

Hope: Sure, my name is Hope Diehl, and I serve as the president of Florida RID.

Carolyn: So, give us a little more about yourself…. come on, don’t be shy.

Hope: I’m an interpreter here in Central Florida. I grew up here. I’ve been interpreting for about 12 years, and I’m lucky to be in Central Florida because it is home to many conferences, so I get to do a lot of conference work on top of the usual VRS, freelancing, etc. There’s a lot of variety in the work here in Florida!

Carolyn: That’s very exciting! Recently, you and I were discussing FRID, and you were telling me all of these exciting things that were going on in your affiliate chapter. I was so excited that I thought, why don’t we take this opportunity to highlight FRID for the VIEWS AC Corner article? Would you mind telling us some of the exciting things happening at FRID?

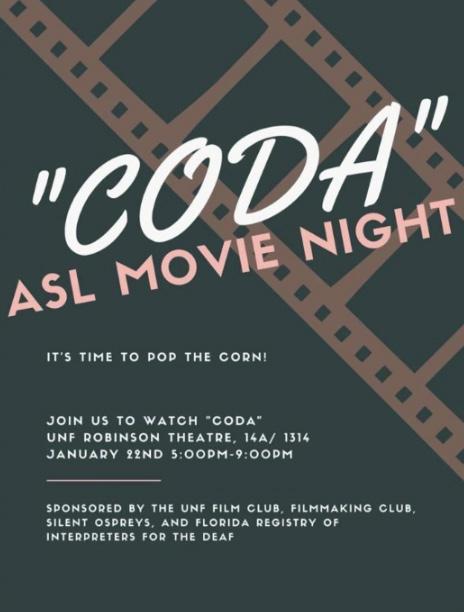

Hope: This year has had so many things happening; well, this calendar year. In January, we had a movie watch party to watch CODA at the University of North Florida (UNF). You know where that is, right Carolyn?

Carolyn: Oh yes…

Hope: Right! So, we had a watch party there at UNF. At the time, our AEO Chair, Carly Hudson, was the one that set up the watch party, planned everything, and executed the evening. Many people came and watched the movie CODA together, which was so exciting. Also, we created a partnership with the Orlando Magic Basketball team here in Orlando. We set up the first-ever ASL night and had different organizations, such as the school for the Deaf, the local school system, and local community members, all come together at the game. It was a night for accessibility and inclusion to spotlight ASL.

It was really neat; FRID worked with an interpreting agency and invited a few local FRID members to their suite. It was fun to watch the game together. It was a great night, and from now on, we will have that same

Carolyn: Wow! FRID has had so many activities; you went to the NBA game, and you had Splash. Another event we talked about was something that happened at the school. With books, a law, or something that happened, all of the Deaf kids came together. Do you want to tell us about that?

Hope: Oh, yes! That was not a FRID event, but I went to represent and show support. It is a district local to me, Orange County, here in Central Florida.

Orlando Magic court spelling out, Verbatim Languages, the local agency that partnered with FRID for the event. In that image are FRID Board members, FRID members, spoken language interpreters, agency owners and operators, and friends and family.

event annually. I feel blessed to have been there that first night. I am fortunate to be part of the planning process for that awesome event.

Another event that just happened this last weekend on Sunday was called Splash into Interpreting. A local community has a nice water park, with canoeing and tubing in the water. Also, there were a variety of different water activities where they could jump into the water. That was really cool and we had a lot of fun! We had a few interpreters, who were new to the area, show up so they could learn more about interpreting in the area and what options were available as an interpreter in Florida. It was very enjoyable to see people with their families and their children, and the new interpreters. It was fun spend time together signing, networking, and meeting the new interpreters in the area.

It just happened that the School Board was meeting; they usually have meetings every two weeks. But this school board meeting was extraordinary because many people came together from the community to emphasize the happenings regarding

educational interpreters in one specific school but also county-wide. The problem is that there are not enough interpreters. The Deaf students, the ASL teachers, the Deaf and Hard of Hearing teachers, and interpreters bonded together and went to the school board meeting to force the School Board’s attention on the issue. So, at this time, we are in discussions with the board to see how FRID can help with

Magic game ASL night spelling out F-R-I-D is Hope Diehl (President), Mary Hoover (Member-at-Large), Melanie Peach (Sponsor Chair), Genaere Lowery (Region Rep East), and Corey Helvey (Orlando Magic Rep). Ryan Shephard (CDI), Hope Diehl (FRID President), Keri Brooks (CDI), Daryl Everett (FRID Region Rep West).resources—for example, gathering information about rates, and job descriptions, to be able to compare what other counties are doing and how they could become more competitive to recruit interpreters to work in the educational setting.

Carolyn: Also, when we discussed that meeting with the School Board, you mentioned that the kids testified or expressed their feelings to the School Board.

Hope: Oh yeah, it was so moving! I’m not really in the school system right now, so I’m removed from a lot of these students and their experiences; most of my work is with adults in the community, but I was so fortunate to be there to witness the students getting up and advocating for themselves and expressing their feelings, sharing their struggles and their frustrations that they have had in the school system. It was beautiful to see.

Carolyn: So, that was with the school board the kids were talking to, right?

Hope: Yes, that’s right.

Carolyn: Wow, do you feel like it’s going to make an impact on the school board?

Hope: I really think it will, there was an extensive group, and I really think that the school board was listening. I’m hoping we can continue attending the school board meetings. They have open public meetings. So, I’m really hoping that other Board members can go as well, and we continue to show up and stay on it to see their response.

Carolyn: That is so great! On another note, you have been the Affiliate Chapter President at FRID. What is your favorite part about being the president of FRID?

Hope: Since I have been an interpreter, I’ve heard many people say, “what does FRID do for me?” “Why do I join? We pay our dues to be a member, and what do I get?” I just feel excited to help respond to that question. I hope to add value, create new ideas as a board and help people understand how relevant FRID is. Also, to establish activities that would demonstrate that value. Also, because of everything we’re doing as a Board, we can add value to what’s happening at FRID.

So, for example, we used to email all the FRID members on “FRIDay” to let members know what was happening in the organization. We send that out every

“The kids themselves testified or expressed their feelings to the school board.”

two weeks, but now we are adding video content with seasonal signs, such as football season. So, FRID made a video with a Deaf person showing how to sign football signs. Adding this content is one way that we can show members that their membership has value.

Also, one of our recent board members appointed is Katryna Arias, and she’s a certified wellness coach, so she will be providing tips such as proper ergonomics and ensuring that you drink enough water and take care of yourself throughout the day. Just little reminders to show our interpreters that FRID cares about them and their wellbeing! I’m excited about that.

Hope: Oh yes, there is another event I just remembered I wanted to mention, I almost forgot, but one of our region representatives on FRID, Daryl Everett, she planned a pottery night. So, members could go to the pottery place, pick an item to paint, and then leave it there for the people to put their painted items in the kiln. Then, we would go back and pick up our painted item. That was one of our networking events that happened the last week of July.

Carolyn: That sounds like so much fun! It’s wonderful, and I’m so impressed with your efforts as President of FRID. All of those events that are occurring are genuinely amazing!

I really appreciate you taking the time to describe briefly the events that are happening at FRID. Thank you so much, Hope, and I know the RID members who read the article and see our video conversation will also be impressed with FRID!

Thank you for serving at RID as President of FRID and meeting with me!

Hope: Sure thing! Thank you for your time!

Carolyn: So exciting! Is there anything else that you want to add?

“What does FRID do for me? Why do I join? We pay our dues to be a member and what do I get?”

“Just little reminders to show our interpreters that FRID cares about them and their wellbeing!”

Sorenson is commi ed to connecting Deaf, hard-of-hearing, and DeafBlind people through the power of the world’s signed and spoken languages — this requires a skilled and diverse workforce of interpreters. Sorenson is the largest private employer of sign language interpreters in the world and is dedicated to investing in a skilled workforce.

Emerald Program. Training for the Video Relay specialty.

Video Relay Service interpreting is a specialized type of interpreting requiring skills and knowledge above those learned in interpreting programs and community practice. Sorenson recognizes VRS (Video Relay Service) as an integral experience in the lives of Deaf people and understands that many times an interpreter’s rst encounter with VRS is on-the-job. Our Emerald Program provides guided support in customer service, call interaction, clari cation, and topical vocabulary to interpreters who are new to Sorenson VRS work.

Individuals who qualify for the Emerald Program experience our comprehensive New Hire Training and bene t from a wraparound paid training that includes mock interpreting practice, small group coaching in VRS speci c skills, and an extended period of supported phone time. Emerald Program creates contextualized training for this unique se ing through the inclusion of Deaf customers, seasoned VRS interpreters, and managers of VRS call centers. Sorenson is commi ed to ensuring our customers have a successful experience by investing in the interpreters doing this specialty work. Emerald Program seem like the right t for you? Apply for a VRS or Community position and screen with us to determine eligibility. Open positions can be found here

Deaf Interpreter Academy. Something for everyone. Sorenson’s Deaf Interpreter Academy works to promote best practices in Deaf-hearing interpreter teaming through trainings, resources, IEP curriculum supplements, and community partnerships. DIA o ers monthly webinars for working Deaf interpreters, an a nity mentoring program for Deaf interpreters from underrepresented communities, and the Gear Up program supporting newly trained Deaf interpreters’ transition into professional interpreting work.

Want to boost Deaf-hearing interpreter teaming in your area? Contact us today to discuss resource-sharing, workshop, and partnership opportunities! Check out at DIA’s resource website for Deaf and hearing interpreters, trainers, and consumers.

Compass. Providing growth and support for Codas.

Sorenson recognizes that traditional educational paths to becoming an interpreter may not be a t for those who grew up with Deaf parents. As a result, Compass provides a tailored interpreter education program for nearly fluent Deaf-parented heritage users of signed languages. Compass instructors and mentors work to grow participants’ existing language skills and help them explore their identities and culture. This structured 10-month opportunity is fully online, is o ered at no cost to participants, and is designed to put them on track toward becoming a professional interpreter.

Investing in interpreters of various backgrounds.

Sorenson’s Interpreter Education and Professional Development (IEPD) department employs 60 educators, half of whom are heritage language users of ASL (either Deaf or Coda). This talented, passionate, and dedicated sta is commi ed to ensuring Deaf, hard-of-hearing, and DeafBlind people are connecting with people who don’t sign. Sorenson invests in this connection by supporting the wraparound paid video relay training, Emerald Program, as well as Deaf Interpreter Academy and Compass which recognizes that not all interpreters arrive to the profession following the same path.

Video includes ASL & Spanish translations of this article

CEUs are always on the forefront of an interpreter’s down time. Do I have enough? Where can I learn about this new topic? How can I improve my skills? Will I get this done in time?

In the last 5 years, and really the last two plus years, the ability to find and attend workshops has changed. With our profession changing so are our abilities to attend workshops from presenters all over the world. Interpreters are getting up at 5am just to attend a workshop that starts at 9am EST. Or staying up late to attend a west coast based workshop. Yet, have we become complacent with our workshops? Are we just taking this workshop just so we have the right number of CEUs to maintain our certification? OR are we advancing ourselves and taking workshops that challenge us or inspire us?

Do we as interpreters apply the same code of moral ethics to our learning as we do to our interpreting work? Do we arrive ready to learn and work and improve ourselves? Giving focus to the presenter? Or do we just let the webinar run in the background as we clean the kitchen? Our CMP volunteer committee works hard to set standards that our volunteer CMP sponsors follow.

The volunteer sponsors support RID’s Professional Development system by diligently checking on attendance and participation and by guiding teachers to develop clear educational goals as well as assessment tools to monitor the transfer of knowledge during the event.

Here in Region 1 we have many AC (Affiliate Chapter) leaders who are providing safe and brave environments to begin tackling the hard work of Social Justice, Racism, and other -isms, within our work and ourselves. Also in Region 1 we have new ideas being researched and explored including our keynote speaker at this summer’s virtual conference, Sociocracy for All. These workshops are shared via email list serves within each AC and on social media.

Since 2020, the state of Rhode Island has been engaged in a community-wide health system transformation initiative made possible through an innovative partnership between the Rhode Island Commission on the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (RICDHH) and Rhode Island College (RIC). In an effort to reduce health disparities and eliminate barriers to healthcare access experienced by Deaf,

Christina

Christina

“Do I have enough? Where can I learn about this new topic? How can I improve my skills?”

Hard of Hearing, and DeafBlind consumers, the project has focused on three main goals: data collection, workforce training, and workforce development. This third goal has led to the establishment of the nation’s first professional development institute for interpreters with a focus on public health and equity.

The Rhode Island College Public Health and Equity Sign Language Interpreting Program (PHESLIP) is a 9-month, 120-hour professional development program for interpreters (both Deaf and hearing). The program consists of a hybrid format, with a one-week in-person residency in Rhode Island in August, followed by 9 months of online asynchronous coursework in medical, mental health, and behavioral health interpreting. Qualified participants who complete this non-credit program will receive a Certificate in Professional Studies and Continuing Education, 12 RID Continuing Education Units

(CEUs), and will meet the 40-hour training requirement to sit for the CCHI certification test. This program [PHESLIP] is designed for current interpreters who want to specialize in public health interpreting and/or want to increase their readiness to work in healthcare environments. Current sign language interpreters who are both credentialed and non-credentialed are eligible to apply. Tuition for the program is currently free. For more information about this program, please contact: Christine West, PHESLIP Program Specialist, at cwest@ric.edu or Dr. Marie Lynch, PHESLIP Program Director at mlynch@ric.edu.

As we fall into the new year and prepare for RID’s Conference in the summer of 2023 themed “Are you Ready” ...What are you ready for? What are you ready to learn? What are you ready to improve with your learning? What CEU opportunities are you ready for?

CEUs can be considered the lifeblood of Affiliate Chapters. Many members ask, “do I have enough? Where can I learn more information about this specific topic? Will this count towards licensure?”

In the past few years, the landscape of professional development has changed tremendously. We are able to attend workshops from all over the world and in many time zones; yet we still have that one burning question of “will I receive CEUs for this?”

In Region 2, many of our Affiliate Chapters are offering more workshops and professional development opportunities than ever before.

There has been a robust number of offerings concerning Power, Privilege, and Oppression topics in order to address the -isms that afflict our profession as a whole and individually. In order to heal we first must be open minded and ready to learn and adjust our own biases towards and cultural misunderstandings of each other.

We are keeping all of this in mind as we prepare for our ultimate professional learning opportunity at this year’s RID conference in Baltimore, MD, July 26-30, 2023. The theme for this year is “Are you Ready?” Region 2 is ready. Are you?

When we think of professional development, there are a lot of different truths to it. I have seen interpreters take advantage of every wonderful opportunity to get insight into improving. Then, some people brush it off and, at the last minute, try to scavenge for whatever is out there to meet the CEU requirements like it is a nuisance. Then others are apathetic, and their only interest appears to be to meet the bare minimum requirements. As a Deaf person who happens to be an interpreter, I have met interpreters in my career who say, “I work all week; I have no time to socialize with Deaf people” or “I sign all week. I need to rest. I do not want to sign anymore.” On the other end of the spectrum, I meet interpreters who take their work seriously and have respect for their craft. We all know the craft of interpreting has to include Deaf people; the saying “without Deaf people, there is no ASL” rings particularly true in the interpreting field. However, does the respect and behavior in our field, generally champion that thinking? Ask yourself.

For me, Professional development has three different areas to consider - our mind, skill, and heart. As for the mind, world knowledge and the fund of information are crucial to our interpreter development. It could be as simple as accurately understanding how welding works so you can interpret the concept better or reading a book on

the history of time to understand how past events impact today. However, do you have a hungry mind that does not want to stop learning and keep going because knowing more is just awesome? The desire to learn is why I am still an interpreter and not going anywhere. It allows me to absorb so much and opens many doors to lifelong learning.

The skill development aspect can be hard or soft skills. Choosing not to socialize with Deaf people when you are not working bothers me because it is a very important skill to push. I can tell whether interpreters socialize with Deaf people because of their signing style. If your signing style is from the 1900s, that is probably the last time you hung around Deaf people. That means you are choosing to drive a very old car compared to the Deaf community’s new car. You must remember that developing your skills and developing your mind are two very different things. Skill is the doing aspect and applying what you have in your mind to the hands using overall linguistic and cultural adaptation to create an accurate message. We need to focus more on professional skill development as an important balance in our work.

Jeremy *ASL Unavailable“Without Deaf people, there is no ASL”

The third, developing your heart, might be the most important thing right now in our profession. We all know the buzzword from a few years ago, “Deaf Heart.” Ask yourself what this truly means to you. We all know interpreters are humans, which means we have an ego, and it is the ego that can interfere with our ability to truly gain an understanding of the meaning behind Deaf Heart. I must continue here; the lack of diversity in our field impacts this too. The interpreting field has put interpreters in front of Deaf people, making them the focus. When Deaf people or our POC colleagues express frustration or ask for an adaptation from the dominant way of thinking, the “I” often overcomes listening. We all need to work together to remove ego for the greater good of our field and the Deaf community. Once we do, the positive impact will ripple back to all of us.

Here are some things region five affiliate chapters are doing for professional development.

Hawaii

1) HRID AC has PDC to help provide training opportunities to our members and anyone from the community who is interested, which is probably true for most ACs.

2) We also have a Google group to share various news and opportunities for our members.

Presently ORID has a professional development committee to help collect PD ideas from the membership and potentially coordinate workshops. Through the pandemic, though, there has been little action. However, through our connections with Western Oregon University, we are cosponsoring one fall workshop on co-navigation with blind persons.

Another professional development initiative in the works for the organization is a certification study group suggested by a member. The board agreed it would be a great way to support professional development and provide safe spaces for the community of practice to interact, which goes in hand with the idea that the board had to provide open remote supervision sessions to the membership once a month. These ideas are still in development, so please let me know if you would like a follow-up at any point.

UTRID has been active in professional development for many years. Even though 20202022, we hosted virtual workshops each quarter for our members and students. In addition, we recently held our state-wide conference with the theme of “Level Up” and provided onsite and virtual options, including streaming our keynote. During the conference, we provided opportunities to earn 16 contact hours of professional development. We have an active Professional development committee with a new chairperson elected in August 2022 that looks forward to planning 2023 events during our board retreat in November.

3) I believe that mindset is one area of training that might need improvement. However, mindset can be a potent tool in our professional and personal lives.

Our membership continues to grow in learning about HI/DI team interpreting, and we will provide ongoing workshops focused on supporting our certified Deaf and hearing interpreters.

“We all need to work together to remove ego for the greater good of our field and the Deaf community.”

“Mindset can be a potent tool in our professional and personal lives.”

Although WSRID has been without a PDC chair for several years, the board has accepted the responsibility of this work. As such, WSRID continues to host professional development opportunities through workshops, webinars, and information sharing of events hosted by other organizations. General areas of focus for our trainings/webinars often include “soft skills,” developing empathy, understanding systems of oppression, power, and liberation, and “hard skills.”

Over the past few years, WSRID has prioritized workshops that offer more of the former and less of the latter.

SCRID’s Professional Development Committee is offering professional development opportunities under the direction of a rotating project-based leadership approach, as the position of PDC Chair is currently vacant. In an attempt to demystify and accentuate the “doability” of professional leadership and engagement, we’re providing a fall workshop “Put Your Hand in it! A Recipe for Relevant Progress in Our Profession.” This workshop will explore what leadership looks like and how we all have experience in one way or another that is helpful when brought to the table. The aim is to highlight how doable it is to engage professionally and ramp us up for elections next May.

Last year we hosted several online workshops and virtual social meet-ups. This year we have focused on board leadership and governance training as we revise our policies and procedures and recruit more committee coordinators. In addition, we are working with our new PDC and CMP coordinators to plan for 2023.

While not exactly a professional development learning opportunity, supporting interpreters in their journey to certification fits under this umbrella. WSRID launched our new scholarship program this year, offering four scholarships a year to qualified candidates. The scholarship covers the total exam fee for both RID CDI and NIC performance exams, and the EIPA performance exam.

We also hosted a virtual info session explaining the various pathways to certification.

In the spring, SCRID will host a workshop, details to be determined, that focuses on self-assessment while in the field. This workshop will support to all participants, and lead into a three-month trial mentorship program that will replace the third of our usual workshop slots (our bylaws require a minimum of 3 PD opportunities annually).

Mentoring is consistently a primary ask from members (hence the workshop on self-assessment, teach to fish rather than get someone to fish for you.) So, we decided that instead of bringing in a presenter for a third workshop, we would support (pay and supervise) qualified local members in providing mentorship to emerging practitioners in our chapter.

Outside of SCRID’s PDC opportunities, we host social media sites on which members can post PD events.

“The scholarship covers the total exam fee for both RID CDI and NIC performance exams, and the EIPA performance exam.”

“In the spring, SCRID will host a workshop, details to be determined, that focuses on self-assessment while in the field.”

SaVRID also has been fortunate to have an active PDC chair/committee. Historically, we have had “insights” one-hour CEU opportunities after our general meetings. Those went away, but now that we have a FULL TEN PERSON board (woot woot!), those are coming back, with our first one lined up for November.

IdahoRID is trying to provide 6 Mini Workshops each fiscal year

Over Zoom making it accessible to interpreters throughout the state.

9 hours of Professional Development (Licensure Law requires 10 hours a year of CEUs)

Free

Prior to this, in 2022, our former PDC chair/ committee hosted a workshop titled “The Medical Kaleidoscope: A Conversation on Perspectives” by Corey Axelrod (as required by a motion passed by the membership that SaVRID provides one .2 CEUs medical workshop every year). In addition, SaVRID hosted two workshops: “K-12 Interpreting in Mainstream School Settings” and “Reframing our Lens of Interpreting within BIPOC Deaf Community,” by Janae Cobbs.

Free to Region V (Region V Agreement gives all ACs in our region the member price, including IAD & Idaho ASLTA) ▪

Many North Idaho interpreters belong to WaRID due to their proximity. ▪

Many East Idaho interpreters belong to URID due to their proximity.

Provides Presenter opportunities on a smaller scale for those wanting to gain experience.

“Historically, we have had “insights” one-hour CEU opportunities after our general meetings.”

By Louis Ricciardi, Assistant Professor

By Louis Ricciardi, Assistant Professor

awareness of the needs of the Deaf community and, therefore, not a lot of support for the accommodations I needed for effective education. I have experienced a funeral for my grandmother where the funeral home brought in a retired pastor to interpret despite not being an interpreter and having a limited grasp of sign language.

In an era where Deaf students were lucky to have an interpreter, I experienced varying levels of quality from the good, bad, and just plain ugly. I attended mainstream schools with sign language interpreting services for most of my education in K-12, postsecondary, and graduate studies. It was only in adulthood that I started to recognize what quality interpreting services meant. I have been a consumer in many different types of scenarios. I experienced my mother interpreting for me during doctor’s appointments and Emergency Room visits before I understood my rights. I am thankful for the support of my family during my upbringing. Still, I grew up in the 1980s and ‘90s in an area where there was not a lot of

Following graduate school, I became an ASL instructor. It was during that time I started to come into my identity as a Deaf person. During medical appointments, meetings for work, and family functions, I experienced many situations where other people decided what appropriate accommodations were for me. For example, in the past decade, I have experienced medical appointments with doctors deciding that employees who have deaf family members are sufficient to be interpreters. Likewise, I have experienced faculty meetings where leaders decided it was acceptable to proceed as scheduled despite no available interpreters.

“I experienced my mother interpreting for me during doctor’s appointments and Emergency Room visits before I understood my rights.”

Sadly, this kind of experience is common throughout the Deaf community. Using this experience aided me in my career as an interpreter trainer. I have the opportunity to do what I love while making a living and building relationships. The students who graduate from our program will work with the Deaf community for a long time. I want to ensure they understand our communities’ beauty and richness. In 2018, I became a tenure-track faculty member with a 4-year route to tenure.

To be granted promotion and tenure, I needed to show that I had put in effort in three different activities. The most important activity at the instructor rank was teaching and learning. I taught all levels of ASL for our program while teaching Deaf Culture and Advanced Interpreting courses. Professional and Service activities were two other activities expected of me for consideration for promotion and tenure. I am involved with different organizations relating to ASL teaching, and I have

served on various committees for the college. I knew I had put in the time and effort to get tenure, but the process was stressful!

This year, after successfully applying for promotion and tenure, I am honored to be the first Deaf person to earn tenure at Columbus State Community College (CSCC). Tenure is my most significant accomplishment by far in my life. I hope to honor my predecessors who helped the CSCC Interpreter Education Program be what it is today and to continue their hard work. In addition, as a tenured faculty member, I feel empowered to speak up for myself and my fellow Deaf community members to ensure communication access. I want my lived experiences, future actions, and teaching to ensure a more accessible world for all Deaf communities. In addition, the interpreting profession must recognize and value the Deaf people who share their experiences. Therefore, educating high-quality interpreters is my top priority!

Being an interpreter, by definition, includes familiarity with and fluency in at least two languages and cultures. Therefore, interpreter education must include the intentional development of both working languages so that students and practitioners can communicate cross-culturally. The higher quality of services provided, the more fully Deaf/hard-of-hearing citizens engage in, contribute to, and prosper within society as autonomous individuals.

The landscape of interpreter education and training remains constant as the understanding of the profession, work expectations, and consumers served continues to evolve. Between 2009 and 2017, we conducted a longitudinal study of graduates from a bachelor’s in interpreting program (Maroney & Smith, 2010; Smith & Maroney, 2018). We have redesigned the program due to what we have learned about preparing interpreters and the values embedded in the principles below that guide our practice as interpreter educators; Interpreters work in a multicultural/multilingual community of practitioners and consumers; connection, representation, and communication matter. Interpreters provide cultural and linguistic access.

The conversation regarding the gap (see Cogen & Cokely, 2016; Godfrey, 2011; Intelligere Solutions, 2017; Patrie, 1994; Ruiz, 2013; Stauffer, 1994; Volk, 2014; Witter-Merithew & Johnson, 2004) continues in our field. We studied the perceived gap between graduation from an interpreter education program and readiness-to-work and/or certification. The findings indicated that graduating seniors who participated had an average EIPA score of 3.39 (Smith & Maroney, 2018), which does not qualify them to work in Oregon or 33 other states where the EIPA requirement is 3.5 or higher (NAIE, 2021).

Elisa M. Maroney, Ph. D., CI and CT, NIC, Ed: K-12 ASLTA Qualified Amanda R. Smith, MA, CI and CT, Ed: K-12, NIC-M, SC:L, ACC coaching credential“I did then what I knew how to do, now that I know better, I do better.”

~Maya Angelou

The research data has confirmed what we have long suspected; though the graduates from the bachelor’s program are gaining employment due to the high demand for ASL/English interpreters, many of them are not credentialed by the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID). According to RID, “Candidates earn NIC [National Interpreter Certification] Certification if they demonstrate professional knowledge and skills that meet or exceed the minimum professional standards necessary to perform in a broad range of interpretation and transliteration assignments” (20152022). The Center for Assessment of Sign Language Interpretation (CASLI) states that “The passing rate for the NIC-Interview and Performance Exam has hovered between 25% to 30% since its launch on December 1, 2011” (CASLI, 2022). This pass rate represents the entire pool of candidates nationwide. We believe that if the NIC assesses “minimum professional standards,” interpreter education programs should be graduating interpreters who meet these minimum standards. We hope to address the lack of credentialed interpreters from the interpreter education perspective. Other stakeholders might benefit from reviewing the data and challenging the status quo.

To mitigate the gap between graduation and credentialing, a new pathway, a BS to MA in Interpreting Studies: Theory and Practice, was developed. An undergraduate foundation in interpreting with a concentration in a second working language prepares students to enter the MA degree to apply theory to practice. The entire pathway emphasizes the observation, practice, supervision, and reflective practice of interpreting.

Unlike other professions, such as nursing (Nursing License Map, 2022), the interpreting profession has yet to establish what entry-level means or where new interpreters should begin their careers. Unfortunately, some recent graduates without certification or credentialing and who do not possess minimum skills can still find ample job opportunities. Witter-Merithew and Johnson (2004) write, “practitioners can and do work without a credential or academic degree, and the definition of who is qualified to perform the task of interpretation is subject to a wide range of views and standards” (p.2).

More evidence for changing our approach to interpreter education in the 21st century is the data accumulated during the eight-year study regarding graduation to credential readiness. Throughout this

study, the graduate results remained consistent while recognizing that the requirements and stressors of the job of interpreting have increased (Pollard et al., 2021). The needs of the Deaf community have also changed (Holcomb & Smith, 2018). There are more Deaf/hard of hearing individuals completing college degrees who are Black and Latinx, especially Black Deaf women, completing at even higher rates (for example, see NDC, 2021; Thew Hackett et al., 2016). Consistently our data collection from past graduates and employers has indicated a need for a longer duration of supervised experiential courses.

Thew Hackett et al. (2016) conducted a Community Needs Assessment specific to the Deaf/hard of hearing population in Oregon. The findings are informative for the State of Oregon and may serve as an example for other states. This study indicated frequent frustration or lack of access to state services due to the “lack of interpreter availability” and/or “finding qualified interpreters.” The state of Oregon needs more interpreters and more interpreters of quality sufficient to meet the needs of the range of Deaf/hard of hearing citizens, from accessing state services to being able to navigate very specific, technical jargon with Deaf/hard-hearing individuals in the workforce.

Few, if any, interpreter education programs produce graduates with the professional skills necessary to provide adequate educational interpreting services to students who are deaf/hard of hearing (Smietanski, 2016; Smith & Maroney, 2018; Smith, 2010). There is a significant shortage of quality interpreters to serve Deaf citizens in the State of Oregon (Thew Hackett et al., 2016) and the nation at large (Olson & Swabey, 2017). The consequences are compromised quality of life for Deaf/hard of hearing individuals as access to education, work, and health care are limited by the skill set of the assigned interpreter.

Even in programs that are well respected, with highly sought-after graduates, sufficient numbers of qualified interpreting students are not graduating to meet the needs of the Deaf Community. Though many argue that interpreting is fundamentally about meaning transfer between languages, it is much more than that. We need to look at interpreter education from a completely different angle, starting earlier, including community engagement and growing familiarity with new settings, people, language use, and communication styles. “The time has come in interpreter education and assessment to shift the focus from just ASL development/competence to include the professional practice of interpreting”

(Smith & Maroney, 2018, p. 34). Additionally, there are different needs for those students who are native English speakers and those who are native/ primary users of ASL or another language. CASLI (2022) states, “Data analysis on the various skills evaluated on this exam indicates an area where candidates struggle overall is interpreting from ASL into English. Candidates consistently scored lower on this component than interpreting from voiced English into ASL.” This indicates a need for more emphasis on language development in both working languages. A pathway that includes a bachelor’s degree with a language concentration to a master’s degree with supervised onboarding can address the needs of heritage signers/speakers (Isakson, 2015; Williamson, 2015), Deaf ASL users (Green, 2017; Rogers, 2016), and those who learn ASL as a second language.

In response to the market challenges and the data we have collected, becoming engaged with interpreting students in their first year as college students will allow them to get a feel for the profession and decide if interpreting fits them. In this new pathway, faculty will engage with students during the foundational stages of their education and support students in making connections to program-specific coursework and concepts. This approach encourages faculty to support students in understanding their education in light of their professional goals. The pathway is rooted in demand-control schema (DC-S) (Dean & Pollard, 2013), making the program similar in structure to other practice professional training programs, such as the mental health and medical professions where students work while engaging in supervision. DCS equips interpreters to consider the full context in which the interpreting task occurs.

The design of this new pathway is based upon spoken language conference interpreter programs; an undergraduate degree focused on acquiring working languages mastery and fluency and a graduate degree focused on developing and honing the interpreting skills needed for professional practice (Middlebury Institute for International Studies at Monterey, n.d.). The development of a graduate program in interpreting demonstrates a commitment to promoting high standards and responding to employment market trends. By offering a master’s degree for entry-level interpreters, the need for qualified interpreters in Oregon and the nation will hopefully be addressed.

A unique benefit of this design is that BS to MA Interpreting Studies: Theory and Practice students take courses alongside MA students in the Interpreting Studies: Advanced and Teaching Interpreting program throughout their coursework. The interaction between

the students on the entry-level track and those on the advanced or teaching tracks allows students to engage in relationships that promote peer mentorship (Nguyen, 2017), collaboration, and the development of a “community of practice” (Mercieca, 2017), which continues after graduation from the program. This may address the isolation that interpreters often experience (Swartz, 2008). This opportunity for a community of practice involving one’s peers and advanced practitioners that students want to emulate is essential for their professional development. An added benefit of this community of practice is that Annarino and Hall (2013) found that interpreters are more likely to be concerned with ethical decisionmaking if they feel they are a part of a professional community.

We are collecting data on the obstacles and benefits of this new pathway to determine effective curriculum and sequencing and develop a working definition of “work readiness.” The bottom line is that the range of consumers has expanded and deepened. To do better, entry-level interpreters need to be ready to serve these consumers in a multicultural landscape, meeting the minimum standards set by RID (2022). It is time to expand our understanding of interpreting and adjust our programs to be holistic in nature and not overly focused on one language. To ensure that the consumers are served well, graduates will need to appreciate the multifaceted complexities of interpreting work, from fluency in their working languages to the interpersonal, environmental, and intrapersonal demands and ethical decision-making processes. To do this effectively, graduates will need to exist within a community of practice.

Interpreter educators have been doing relatively the same things for nearly 50 years with similar results. The 21st century brings the recognition of new demands that may require new ways of thinking to respond. Now that we know better, it is time to try something new by disrupting and challenging the status quo.

(Click here for references)

In October of 2021, the DeafBlind Interpreting National Training & Resource Center in Western Oregon University’s Research & Resource Center with Deaf* Communities received a $2.1 million dollar grant from the U.S. Department of Education’s Rehabilitation Services Administration (RSA). The grant has since undergone a name change to the Protactile Language Interpreting National Education Program to reflect the work better. PLI works to address the critical shortage and increase the number of qualified Protactile language interpreters with the expertise to interpret communication exchanges with DeafBlind individuals effectively. This work also addresses distantism in interpreted interactions, which refers to the privilege of distancing senses (hearing and vision) and not needing touch as a means of communication. This is the second grant PLI has received from RSA. The grant will fund projects for five years and continue work that began in 2017. The first grant cycle included

• training nearly 30 DeafBlind leaders,

• training over 150 interpreters to work with DeafBlind individuals in the United States,

• the creation of online video modules that nearly 5,000 people have viewed.

For those interpreters who regularly work in communities with greater concentrations of DeafBlind individuals, PLI is launching a Pilot cohort in 2023. The PLI Pilot creates intensive immersions for DeafBlind educators to train Protactile language interpreters.

There is no other immersion opportunity to prepare interpreters in learning, practicing, applying, and interpreting in Protactile language.

In an effort to increase the number of qualified interpreters in states with larger DeafBlind populations, PLI’s immersion training programs will focus on interpreters from the following noncontiguous geographic locations: CA, IL, LA, MA, MN, NC, NY, TX, and WA. PLI Pilot participants will be able to:

• Compare and contrast the linguistic and cultural value differences between Protactile language and visual ASL.

• Apply the principles of Protactile language.

• Define the role of a Co-Navigator and practice guiding techniques and co-presence.

• Define Protactile language and the cultural implications of autonomy.

• Socialize, learn, and communicate in an immersive PT Zone.

• Demonstrate Protactile back-channeling techniques, including emotions, conversational feedback, tactile mapping, and size and shape classifiers.

• Articulate why using Protactile language builds trust and respect that will lead to greater DeafBlind autonomy.

• Define distantism and articulate distantist and antidistantist behavior.

• Interpreters must live and work as an interpreter in one of these nine states: CA, IL, LA, MA, MN, NC, NY, TX, WA

• Interpreters must frequently work with DeafBlind individuals who use tactile language or Protactile language.

• Interpreters must have worked consistently as sign language interpreters for the last three or more years.

• Interpreters must have letters from 2 DeafBlind community members willing to serve as local mentors and supervisors for the mentorship and applied induction experiences.

PLI does not charge a fee to participate in the PLI Pilot but expects full participation and program completion from all participants accepted into this invaluable training opportunity. The estimated training value is $1500 per participant. Due to the costs of providing onsite, week-long, intensive training, the expectation is that participants pay for their airfare, travel to campus, and meals. In addition, participants must budget $300 for the Induction stage of the program, wherein interpreters return to their home community and compensate local DeafBlind mentors for their consultancy.

John Lee Clark, a DeafBlind poet, author, and PLI consultant, said of the grant award, “Cultivating the professional growth of interpreters and their Protactile skills is not merely a project, but truly a cause. A meaningful and transformative way to bring about the progress that benefits all DeafBlind people, directly and systemically.”

PLI will use asynchronous remote learning (individual modules and self-directed tracks), synchronous remote learning (online Community of Practice model), and onsite learning (language immersion training). This

training program will offer three separate interpreter competency certificates. Individuals enrolled in Certificate 1: Protactile Language Theory will complete an asynchronous, remote, online program of study focused on: 1) The Protactile Movement, 2) Protactile Language, and 3) Protactile: Power, Privilege, and Oppression. Individuals enrolled in Certificate 2: Protactile Language Theory and Fundamentals will complete a facilitated online program of study (asynchronous and synchronous), a one-week PT immersion program, and a three-month mentorship and induction period. Individuals enrolled in Certificate 3: Protactile Theory, Fundamentals, and Interpreting Practice will complete an extended, facilitated online program of study (synchronous and asynchronous), two separate onsite PT immersion sessions, community mentorship, and six months of induction.

PLI’s DeafBlind consultants and educators include Jelica Nuccio, Roberto Cabrera, John Lee Clark, Jason “Jaz” Herbers, Hayley Broadway, Earl Terry, Lesley Silva-Kopec, and Najma Johnson, who provides cultural competency training to the interpreter participants. Project staff includes CM Hall and Heather Holmes as co-principal investigators and directors, Elayne Kuletz as web manager, and Tracie Wicks as grant administrative support.

PLI will continue to serve as a resource center providing educational and professional development opportunities and technical assistance for interpreters, vocational rehabilitation professionals, interpreter educators, employers of interpreters, and service providers. In addition, the training content and materials will be regularly disseminated through online activities and will continue to be retrievable via the PLI website and digital commons archive.

For more information, please visit

www.ProtactileLanguageInterpreting.com

Part two

Hurdich, M.Ed.; CDI, RID Board of Directors Secretary (Past Region II Representative)Amber: Music from the Deaf side was loud, pounding percussion. You could feel the beat, but it wasn’t quite as pronounced on the hearing side. So the differences were there. Also, the experiences were different in the church. In the Deaf world, there were many churches with deaf services. On the hearing side, we had to use interpreters, or I became the interpreter.

noticed and identified and learned to identify who I am, and I learned to like these things and what I didn’t like - that was my experience.

Jason: That’s interesting! Now when you talk about your Troy experience, as you mentioned, that is southern Alabama, right?

Amber: Yes, in very much south Alabama.

Jason: That’s interesting. Wow, growing up, you were immersed in the Deaf world, the Deaf culture and all of the things there, but in the Black culture, Black identity seems that may not have been overly thought of as much as, compared to the primacy of Deaf identity; it seems that the Black identity formation came later.

Amber: Yes, not so much that my Black identity was later - but because in the Deaf world, I felt “normal.’’ It wasn’t until I arrived in Troy that I noticed a difference, which was startling. At home in a Deaf Black house, we don’t sign that way. We don’t do that. I never knew that kind of thing happened. The signs I saw were very different from home. At home, we used Black ASL compared to Troy’s school signs. But with hearing families and friends there at the college - I

Jason: Troy University has the only ITP in Alabama. As you recall, I worked with you in Troy. It is a town of 19,000 students, a small town south of Montgomery, the capital of Alabama. You shared during your presentation at the ALRID conference that you felt like the ITP class was white; you were the only Black student. All of your teachers were white. You felt like ITP was 100 percent white-run, as you shared. Would you mind elaborating on those points as you reflected upon that, how did that impact you, can you give an example of what we might have overlooked in our own privilege, and can you share your experience with that?

Amber: Troy - I was the only Black student in the ITP of white students. We had the largest graduating class in the Troy ITP history at the time, I think around maybe 23 or so students. I was the sole Black student. There was another Black interpreter who was studying online with a different curriculum; however, our experience was on campus. As the sole Black student in the whole class in a white space then, I was the sole visibly different interpreter. I saw a lot of things that I had never noticed before, like microaggressions.

Jason“I was the only Black student in the ITP of white students.”

Jason: Could you give us an example?

Amber: Such as clothing - that is very important in Troy - you must be professional and have colorcontrasting clothing, so your hands are visible. But their key difference they recommended dark colors repeatedly. I am a dark woman! So I had to speak up and ask, “what colors should I wear?” What could I wear? Because my experience is different from the white experience because they know that as a legacy of training for white interpreters. They suggested I could wear pastel colors, which left me feeling off. Whiteness was not considered in the suggestions I was given. But it was hard to figure out what I could wear to look good with dark skin. But not many people realized that these factors were impacting me because of colorism.

had to remember to pull back into the sign box. But that is how white interpreters sign, nice, small, and restricted; light signing, using the signing space chin to belly, and within my shoulder width. As I grew up, I felt we just signed like Black people, and Black people speak the same way, and Black deaf people have their signing, but they called it English, not ASL.

I was signing as a child, and they would say, you’re signing in English. No, I was not signing in English. I signed that way because Black people signed that way. Black ASL was the key difference. Just like hearing people do, we have Black sign language and slang. Black people use AAVE, African American Vernacular English. So you have to understand that I was a Black interpreter looking for more than what I could find in my ITP.

Jason: You felt like the spotlight was being shone on you, and you were being criticized even by your Deaf teachers for your signing style, right?

Amber: Right. My Deaf teachers didn’t realize there were Black ITP students who also wanted to become interpreters. They took ASL 1 and ASL 2, and then they stopped.

Which means that darker-skinned women - really, we stand out. We are always criticized, especially people in the Black community. Especially in the media, which you will see in books a lot of the time. For example, the author Alice Walker writes about colorism. That was really impactful because I was hurt. Now I struggled with darker-skinned women being looked down upon. I struggled, and when I finally started feeling good about myself, the ITP corrected me and criticized me. They criticized my clothing choices and my skin, but they were unaware. They were unaware of the impact because they had never experienced that. But a lot of Black darkskinned girls experience that. So, for example, my sign right now

Jason: Interesting.

Jason: I remember you mentioned that during your presentation.

Amber: My sign space is not small. My signing space is wide and large because Black people sign like that. But I was corrected for that. I was told no, that my signing space must become smaller, and that we have jobs on camera where you need to sign; I had a hard time really being able to interpret because I

Amber: Then I realized as I was asking them, “Did you feel okay?” It was not because the language was so hard. They were criticized because of their signing style, or they would take ASL 1, ASL 2, ASL 3, and ASL 4 and would be doing well. Then, once they got into the ITP, they were criticized for signing too much English and were told, “your hands are signing incorrectly.” They felt they needed to leave and find something else, and they felt so defeated. So you have to understand that the criticisms, yes, you can be straightforward and honest, you absolutely can, you understand. But the different cultures, the difference is there. And that really there was a loss in the ITPs, really the culture of the ITPs was geared towards understanding the Deaf, but not understanding other cultures that were coming into the program; the lack of representation was real. But also, the class was solely taught with understanding the Deaf culture as well; that was the primary perspective. Yeah, I understand. But there was no Black Deaf representation.

“My sign space is not small. My signing space is wide and large because Black people sign like that. But I was corrected for that.”

“You can be straightforward and honest, you absolutely can, you understand. But the different cultures, the difference is there.”

“They criticized my clothing choices and my skin, but they were unaware. They were unaware of the impact because they had never experienced that.”

Jason: You mentioned Black students were taking ASL 1 and ASL 2, and still teachers were criticizing their ASL, calling their signing English, saying they were not fitting in, but criticizing them from a white ASL perspective, which forced the student population to shrink. It wasn’t about ASL 1, 2, 3, or 4. It was that we lost a potential interpreter, right? We lost them.

Amber: In my presentation, I explained my own name; my full name is Amber Marie Robinson. My sister’s name is Camisha Ann Robinson. I noticed the difference on paper; you look at my name, and it looks white. Compared with my sister, her name you can identify that it is Black. I thought to myself, why would I not have a Black name that is pretty like my sister’s? I wanted her name; it was creative. But I realize that it helped me. My job experience in Alabama, seeing a white name, you will be accepted for jobs. That happens in the Black community if you have a whitesounding name, but you’re really not white - you’re Black.

Amber: Yes, because really, ignoring their Black identity, and that’s not all. It was not about not understanding deaf culture. We would then come into the ITP being excited to learn ASL and then being criticized. Why should you stay? Why would you want to stay with that? You can accept that I can sign, just not the way you want.

Jason: I understand. You continued with the program knowing that mindset was present in the ITP, and you continued in doing that. What pushed you to continue, even not knowing about Black ASL until later? How did you move through the program and decide to stay?

Amber: I moved through the program because I am a CODA. It helped me understand this world that you will have to live in. You have to understand the criticism and use that to foster your own push for success. Also, that straightforward blunt attitude that’s just part of the Deaf culture as well. I had to accept that this was something that I understand, okay, I made mistakes, but I’m still myself. The other thing is that I was involved with many other activities and organizations that helped me understand that as a Black woman in a privileged white world, I have to navigate things for myself. And understand that later it will be successful, it will be fine, I will succeed. And lastly, really, my family set me up for success.

Jason: Did you see the dichotomy for your sister?

Amber: In college, I had four roommates. Of the four of us, three were white. I was the only Black woman there. So I walked in and was cleaning up my space. I heard the door and saw my roommate awkwardly saying hi to me. It was very different. I Introduced myself, “Hi, my name is Amber.” She asked me, “Are you sure?” I said, “Yes. Yes, I’m Amber.” She said, “I thought you would be white because I saw your name on the form when we were getting ready to move in. I thought you were a white girl. Wow.” I was like, “Yeah. That’s me.” It was awkward.

Jason: Can you give me an example of your family setting you up for success?

Jason: Yeah, I can imagine it was awkward.

Amber: So, it happens. Also, just to add, clothing: my parents always taught me when going out in public or going places, people around will judge your clothing, that is representative of who you are, so I always want to look my best when I go out when I’m going into a room. For example, in Troy, I always walked into the classroom dressed FINE. The clothing was good. If it was gym class, I always wore something really nice because when people look at you entering the room, if they see a Black person in sloppy clothing, we are judged for that. It would not be remarked upon if a white person was viewed in sloppy clothes.

“I moved through the program because I am a CODA. It helped me understand this world that you will have to live in.”

“If they see a Black person in sloppy clothing, we are judged for that. It would not be remarked upon if a white person was viewed in sloppy clothes.”

“Why would I not have a Black name that is pretty like my sister’s? I wanted her name; it was creative. But I realize that it helped me.”

Jason: I remember your dad, Patrick. He tended to always wear a suit and tie. You mentioned that during your presentation as well. I remember you shared that practice was reinforced at home. Would you mind elaborating on that teaching from your dad and why that was significant?

Amber: Growing up, my family had a practice. It was like a pyramid. At the top is the white man, then the middle, white women. Then at the next level, the Black man. Then at the bottom, Black women. On the bottom level. This means that you have to be the best when you enter a room. You can’t be less than. You can’t be seen as weak because people will judge and perceive you that way in your profession. Typically, going into a Black world, you have to be the best. At all times, the clothing and hair fit and match because that is what people expect in the South. Black people really are looked down upon.

There are all those stereotypes and labels. No. I want to know that when I come in, I mean business. And my attitude and personality will become how I decide whether I am comfortable in a room. Going into a

room where white people are, you have to be on your best behavior. You can have a movement when you can be a Black person and relax, but you have to code switch. Black people use that a lot. My dad taught me that you have to sign differently when you go into a room. You want white people to understand and be comfortable and think, I can read your signs and understand what you are saying. However, if I go to a Black professional setting, it’s the same way. You have to sign clearly, but a little more expressively. My hands right now, my sign window grows and changes depending on the space that I am in. My comfort level changes depending on my audience.

“You can’t be seen as weak because people will judge and perceive you that way in your profession.”

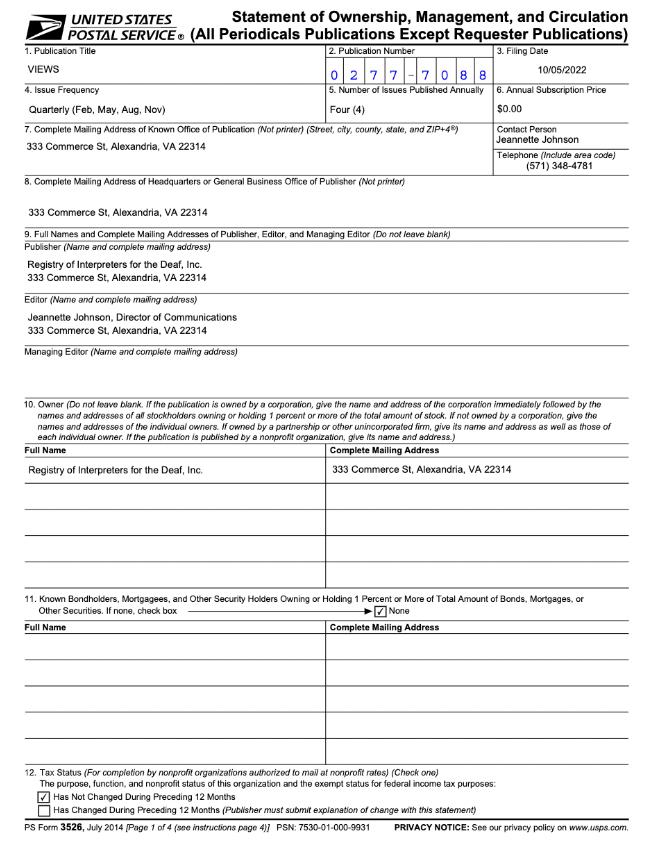

Below is a link to a page on the RID website, accessible to the community at large, that lists individuals whose certifications have been revoked due to non-compliance with the Certification Maintenance Program or by reasons stated in the RID PPM. The Certification Maintenance Program requirements are:

Maintain current RID membership by paying annual RID Certified Member dues

Meet the CEU requirements:

• 8.0 Total CEUs with at least 6.0 in PS CEUs

• Up to 2.0 GS CEUs may be applied toward the requirement

• SC:L only–2.0 of the 6.0 PS CEUs must be in legal interpreting topics

• SC:PA only–2.0 of the 6.0 PS CEUs must be in performing arts topics

Adhere to the RID Code of Professional Conduct

If an individual appears on the list, it means that consumers working with this interpreter may no longer be protected by the Ethical Practices System should an issue arise. The published list is a “live” list, meaning that it will be updated if a certification is reinstated or revoked. To view the revocation list, please visit HERE.

Should a member lose certification due to failure to comply with CEU requirements or failure to pay membership dues, that individual may submit a reinstatement request.The reinstatement form and policies are outlined HERE.