NO-LONGER AND NOT-YET -

TEMPORARY USE TACTICS ON VACANT PLOTS

Rita Roznár

Academic Promotor: Martino Tattara

International Master of Science in Architecture

KU Leuven, Faculty of Architecture, Campus Sint-Lucas Brussels

June 2020

Rita Roznár

Academic Promotor: Martino Tattara

International Master of Science in Architecture

KU Leuven, Faculty of Architecture, Campus Sint-Lucas Brussels

June 2020

Rising rental prices in our contemporary cities make it harder and harder to find rentable living and working places at an a ffordable price. In Brussels, there are 44,000 households waiting get access to social housing, while living in inadequate conditions and housing insecurity. Controversially, the reason why space is becoming increasingly scarce is not due to the lack of space but to the inaccessibility to it. In Brussels, around 15 - to 30,000 1 of the existing housing units are simply empty, either because of property speculation or because of the owner’s inability to obtain a mortgage to refurbish them and the di fficulties with its maintenance and management.2

Empty plots and buildings trigger another pressing urban issue: devitalization and desolation of the neighbourhood. Vacancies accelerates the decay of the building, increases the feeling of insecurity within its neighbourhood and it is connected to a higher chance for vandalism and crime.

Owning a temporarily unused space involves many inconveniences also for its owner: management costs, municipal taxes, security costs, maintenance works and the regional fine on vacancy. 3

Unfortunately, there is no available data in Brussels about vacant properties. This is a huge problem because one of the major challenges in any temporary land-use project is to figure out the ownership relations. In many cases the property does not show the sign of emptiness for many months, making the available space invisible. Studies suggest, that this could be resolved by the town planning agencies, who have access to up-todate data.4 This task is instead o en conducted by nongovernmental organisations and volunteering citizens, who are in need for a space, and therefore have interest in tracking down and occupying the land even for a shorter period of time, until they find a permanent place for themselves.

Vacancy is an issue a ffecting all cities, however I examined an extreme case in the north-western part of the Northern District in Brussels, that shows significant developments in the last 20 years. In the chosen territory, there were all together 14 empty plots since 2001, om which 4 sites are still unoccupied till this day. In average, these building sites stand unused for around 14 years. Most of the cases they have some temporary functions, such as parking, but in other cases these plots are enclosed parts of the city, remaining as missed opportunities.

Empty properties are also urban resources that offer temporary platforms for alternative use. The term ‘temporary use tactics’ refer to a series of strategies for the temporary use of vacancies in the city that trigger entrepreneurship, fuel creativity, allow experimentation and can be also beneficial for the owner.

Temporary use tactics can be initiated with di fferent aims 5: city planners and policymakers use it as an urban tactic with the long-term aim to revitalise and heal the urban fabric; local bottom-up organisations take advantage of the property as a low rent/ or rent- ee space to accommodate there their neighbourhood activities; artists take over these places to create creative hubs for alternative culture embracing its non-institutional appeal. Unfortunately temporary use, (especially the latter type), o en triggers gentrification within the neighbourhood, making temporary use as an attractive tool for property owners to let other creative initiatives experiment with new ways of usage (artistic and cultural activities), which attracts attention and audience with purchasing power; and consequently increases the value of the property.

A recent study investigating the driving forces behind temporary use points to the political dimension of such aspect in terms of the right to space (especially if the terrain or building is public property), the right of use and the right to a decent housing.6 The temporary use of a space is o en linked to political manifestations,

STAND-IN

- no lasting e ffect

- low impact

CONSOLIDATION

- lasting e ffect on the permanent use

SUBVERSION

- strategic occupation

- to disturb/transform the long-term use

CO-EXISTENCE

- informal temporary use moves to a new place / continues to exist next to the new function

such as attention-raising public events and festivals, protests, public disobedience and squatting. In either case, it is important for the occupiers to have long term aims and strategy, so their action leads to positive urban and social change. 7 [ on p. 13]. A long term strategy can be, that the occupiers' suggestions and demands are incorporated into the city planning policies, or that together with the owner they came to an agreement, that is reflected in the future use a er the occupation period is over.[ - ] Lacking strategy, or tactics, the occupation will not have any lasting effect on its urban environment. [ - ].

Recognising the positive urban benefits that temporary activities generate, state institutions can support these initiatives both financially or with favourable legislative environment (such as demolishing or lightening anti squat laws.)

These di fferent dependencies between the owner, policymakers (City) and the occupiers (Users) has been classified by Philipp Oswalt, Klaus Overmeyer and Philipp Misselwitz in the book 'Urban Catalyst' 8 in 6 categories: (1) Enable, (2) Initiate, (3) Claim, (4) Coach, (5) Formalise and (6) Exploit. These categories are also illustrated with diagrams on the following page.

The 1 category (Enable) describes cases when the municipality helps the occupiers (e.g. with special regulations) to come to an agreement with the owner and use the space. An example for this approach is Badeau by Pool is cool, a temporary swimming pool located at the harbour of Brussels in 2016.

In the 2nd and the 3rd category (Initiate, Coach) a non-profit organisation is commissioned by a governmental organisation to gather possible users and together work out the occupation and negotiation strategy. This is o en the case when the public or semipublic territory have been underused for a while, but the future use has not yet started. Parkfarm at the Tour & Taxis park could be a good example for an Initiate project, while Tiers-Lieux ABC a temporary occupation in Anderlecht on a future CLT Brussels property is a good example for Coaching, where the agent was Communa, a non-profit organisation.

The 4ʰ category (Formalise) collects cases where the temporary occupation is managed on a more and more advanced level in order to become feasible to remain on the terrain as a permanent function.

This di ffers significantly for om the 5ʰ category (Claim), where the occupiers use subversion as a tool to disturb/transform the current use and claim their right to use the space. The PicNic The Streets movement in 2012 started as a citizens initiative, but now become part of the urban plan, while Squat Rue Royal 123 is an example for Claim, an occupying of an empty building as a response to poor housing and inequality.

The 6ʰ category (Exploit) collects all the marketdriven approaches where the main aim is to attract people with purchasing power, foster consumerism and consequently generate gentrification. Pop-up shops/ restaurants, and even flea-markets (though not intentionally) o en contribute to gentrification.

In times when cities struggle to adapt to the rapid economic and societal changes, in constant uncertainty and when future trends are hard to foresee, transitory town planning offers a viable solution. Transitory town planning means, that the adaptive tactics of the city users are integrated into the planning process, contributing to the creation of more responsive cities.9

Besides financial benefits, temporary use also has a positive effect on its urban environment if it is well planned and executed. However, defining these obstacles is not so easy to pin down, and in most of the cases, studies rather refer to successful experiments as examples, and not so much to rules or guidelines.

'Meanwhile Space', a British organisation working with unused spaces, monitored the local impact of temporary use and found out that the majority of the interviewed people supported the appearance of such functions in their neighbourhood; and felt that they are profiting om the activities happening there.

In many cases, temporary use generated local jobs and helped local entrepreneurs and producers to start, experiment with or expand their business while saving money on lower rents.

The appearance of such new functions and businesses give confidence for the local residents and hope in the further development of their neighbourhood (especially if these new functions emerged in deprived

areas.) In less a ffluent areas where more vacant units are available landlords are more willing to offer their properties for a temporary use project since they are less likely to find tenants.

Because of the danger of such project generating the processes of gentrification, careful land management and the involvement of local residents in the project can not be emphasised enough.

If locals are involved and encouraged to actively take part in the formation of their neighbourhood, the temporary function has such a lasting impact on the neighbourhood that is beneficial for the locals. In addition, it gives them a sense of responsibility that proves to be really helpful in the maintenance of the collectively planned development.

Without local involvement, property owners will easily recognise the potential in the temporary use as a tool for attracting the a ffluent classes interested in such creative/alternative milieu; and consequently increase the value of their property.

As outlined while describing the di fferent occupation categories on page 6, the Exploit category can range om unintended gentrification effects (triggered by the creative milieu) to marketing and selling concepts, where time-limit gives a sense of exclusivity, which has a huge appeal amongst consumers.10 This phenomena can be well illustrated by the sudden emergence of pop-up shops and restaurants.

Besides initiating with regulations and loose planning, governments can be also owners and managers of these properties. The process in which the governments [or other non-profit organisations] purchase tax-delinquent, tax reverted, foreclosed or abandoned properties and then convert them into productive and attractive pieces of land in order to "bank" them for future use is called 'Land banking'. 11

These vacant plots can be turned into assets for the neighbourhood by adding missing public functions that previous planning decisions failed to incorporate.

This land management technique is also a great tool to provide a ffordable housing12 while stabilizing and revitalising the declining neighbourhood, either by creating state-owned social housing units or by reselling the homes on an a ffordable price.

Furthermore, such properties could be also sold to non-profit corporations that are initiating alternative ownership models such as the Community Land Trusses. This is also an assurance for the government that the property is in the hands of responsible landowners, minimizing the risk of profit-oriented investments and gentrification.

Temporary housing is not a new phenomenon, indeed humankind has been living in temporary and mobile homes for thousands of years.

In western cities temporary use as a tool is mostly applied for public programs such as cultural or public events, and not so much for domestic use. This is understandable since domestic space usually requires a sense of ownership and security that is harder to create within the ambi guous legal and time amework within which occupiers have to operate.

The most common domestic occupation is squatting. This tactic o en has a political motivation claiming the right to decent housing, and the squatters are usually young people, single adults or couples, and sometimes even small families.13

Another domestic temporarily use is when empty buildings and terrains are used for providing emergency housing for people in need. However, it is only a temporary solution. Besides, residents are put at risk of being evicted as it can occur that the occupation period suddenly comes to an end due to unforeseen issues, and they might find themselves in a situation worse than before. Therefore if the aim is to provide accommodation for vulnerable groups, it has to be done with careful consideration and planning, providing security and assurance with occupation contracts and other tools.

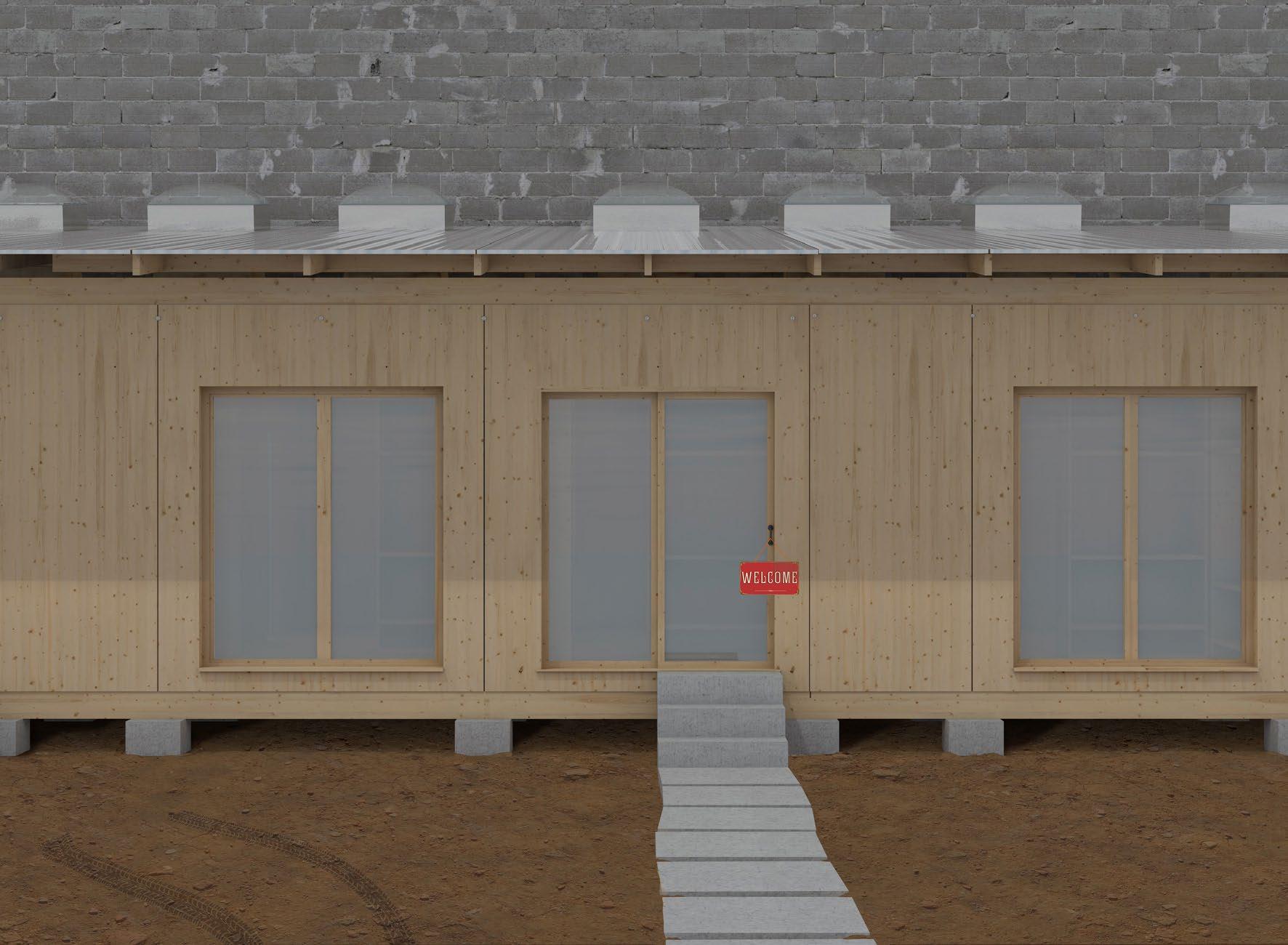

Furthermore, the solution for houseless people is actually not always to provide them with housing. A recent project in Brussels by the organisation Samenlevingsopbouw has an inspiring alternative approach to tackle homelessness. Solidair Mobiel Wonen is their pilot project intending to respond to the shortage of a ffordable and decent housing for homeless people. They use vacant building plots to provide temporary homes for houseless people, but they do not just wish to create places to stay but use the entire process of designing and constructing homes for building new skills and giving confidence and dignity to their future residents. The occupation period will last for around 2-4 years and will consist of 8 individual small dwellings and a communal space. Future occupants are homeless people, who are currently living in shelters and would like to take the next step to become independent, but they need a bit of help. Solidair Mobiel Wonen is a transitory stage, where participants have coaching sessions, job training, technical workshop to learn new technical skills and most importantly the become part of a supportive community. Thus at the end of the tenancy (or even before), they will be able to enter the labour market and find a permanent home. 14

Besides emergency housing, there are actually many life situations in which people with limited financial needs suddenly find themselves in need for temporary accommodation until they find a permanent place in the housing market. These situations can range om job loss, health issues, divorce or decease of a family

member. Lack of rentable housing is also a problem for the 'middle-class migrants' who temporarily change their residence because of a better job or educational opportunity in another city.15 The property market does not provide homes for these groups but temporary occupation could serve as a solution.

9. Peter Bishop and Lesley Williams, The Temporary City (Oxford: Routledge, 2012).

10. Rosalyn Deutsche and Cara G. Ryan, "The Fine Art of Gentrification," October 31 (Winter 1984): 91-111, doi:10.2307/778358.

11. Tappendorf, Julie A. and Brent O. Denzin. "Turning Vacant Properties into Community Assets through Land Banking." The Urban Lawyer Vol. 43, no. 3 (Summer, 2011): 801-812. https://search-proquest-com. kuleuven.ezproxy.kuleuven.be/cview/902766703?accountid=17215.

12. Sohil Shah, "Saving Our Cities: Land Banking in Tennessee," University of Memphis Law Review 46, no. 4 (Summer 2016): 927-972

13. Alexander Vasudevan, The Autonomous City: A History of Urban Squatting (London: Verso Books, 2017),

1. “An Appalling Number of Vacant Houses,” Rassemblement Bruxellois Pour Le Droit à L’Habitat, last modified March 16, 2015, https://www.rbdhbbrow.be/spip.php?article1672.

2. Alexandre D’hoore, “Opinion | The Housing Crisis Paradox: How the Citizens of Brussels Are Reclaiming Unused Space,” The Brussels Times, last modified November 29, 2018, https://www.brusselstimes.com/ opinion/52202/the-housing-crisis-paradox-how-the-citizens-of-brussels-arereclaiming-unused-space/.

3. The regional tax on vacancy in Brussels can reach 150 euros per running meter of the ont façade - in the case of an empty building.

4. Dr Simon Parris, Temporary Use Practice, SEEDS Workpackage 3, (She ffield: South Yorkshire Forest Partnership / She ffield City Council, 2015), www.seeds-project.com.

5. Philipp Oswalt, Klaus Overmeyer, and Philipp Misselwitz, eds., Urban Catalyst: The Power of Temporary Use (Berlin: Dom Publishers, 2013).

6. Peter Bishop and Lesley Williams, The Temporary City (Oxford: Routledge, 2012).

7. Lauren Andres, “Di fferential Spaces, Power Hierarchy and Collaborative Planning: A Critique of the Role of Temporary Uses in Shaping and Making Places,” Urban Studies 50, no. 4 (March 2013), doi:10.1177/0042098012455719.

8. Philipp Oswalt, Klaus Overmeyer, and Philipp Misselwitz, eds., Urban Catalyst: The Power of Temporary Use (Berlin: Dom Publishers, 2013).

14..."Solidair Mobiel Wonen," Samenlevingsopbouw Brussel, accessed April 6, 2020, https://samenlevingsopbouwbrussel.be/wat-doen-we/ projecten/swotmobiel/.

15. Rebecca Roke, Mobitecture: Architecture on the Move (London: Phaidon Press, 2017), 11-12

Images on page 15:

(1.) BADEAU by Pool is cool, a temporary swimming pool at the by the harbour of Brussels, August, 2016.

"Badeau," Pool is cool, 2016, http://www.pooliscool.org/news/2016/9/22/ badeau-the-first-public-open-air-swimming-pool-in-brussels.

(2.) PARKFARM at the Tour & Taxis park, Brussels, 2014.

"ParckFarm T&T," visit.brussels, n.d.https://visit.brussels/pt/place/ ParckFarm-T-T.

(3.) TIERS-LIEUX ABC by Communa, temporary occupation in Anderlecht, 2019.

"Tiers-Lieux ABC," Communa, 2019, http://www.communa.be/lieux/ tiers-lieux-abc/.

(4.) THE PICNIC THE STREETS movement by the Brussels stock exchange, 2012.; Pic Nic the Street Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/ PicnicTheStreet/photos/a.248370838611282/575343475914015/?type=1&the ater.

(5.) Plissaert M.F., "Squat at rue Royale 123," , 2016, https://issuu.com/ ldesiron/docs/le_droit_a_lhabitat_par_loccupation.

(6.) "place_du_jeu_de_balle_brussels_antiques_market_smarksthespots_ blog_04," S Marks The Spots, 2013, https://www.smarksthespots.com/placedu-jeu-de-balle-flea-market-brussels/.

To re-activate underused areas, citizens can take on a pro-active role, which usually develops out of the ustration that declining empty buildings cause, and om the fact that the decision-making is in the hands of city leaders, and not in the city dwellers living there. Giving access to these places empowers the local people, who then - with their thorough knowledge of the context - can come up with ideas for possible alternative usage, that city planners would not necessarily come up with.

Carrying out such a program involves a great deal of commitment and enthusiasm om the initiators, requiring knowledge and overview of complex legal regulations, in the absence of which such initiatives will eventually soon die.

Non-profit organisations can take over these duties and with their time and experience can help in the negotiation and occupation process.

Most of these non-profit organizations have grown into this semi-institutional role om small bottomup initiatives with the overall goal of exploring the possibilities that underutilized areas offer.

These intermediate parties di ffer greatly in the way they operate. The London based organisation 'Meanwhile Space' works more like a socially oriented real estate company, managing the vacant property as

a landlord helping community interest businesses and organisations to get access to space at an a ffordable price. The Aarhus based 'Institut for (X)' operates as a cultural and informational platform supporting citizen initiatives while developing its neighbourhood with grass-root activities. 'Free Riga' in Latvia and 'Yes we camp' in France are mixing bottom-up neighbourhood activities with transitory town planning strategies to tackle the issues connected to vacancy.

The Brussels based organisation 'Communa' has the aim to heal the urban scars by temporarily occupying vacant places. With the approval of the owner, they accommodate socially-oriented, non-profit organisations in them and provide homes for people in need.

The property is a platform for experimentation to test new functions (neighbourhood cinema, dance hall, community kitchen) that could serve the surrounding residents and strengthen the community. Therefore a strong collaboration with the neighbours is key when designing and realising their projects.

The recovery of the empty places happens as follows: upon choosing the next possible building that seems appropriate for such an intervention, Communa contacts the owners of the property and tries to convince them about the benefits of temporary occupation. They then sign an occupancy contract and Communa

1

2

3.Signinganoccupancycontract

4.Co-designingtheplacewith futuretenants

5

6.Accommodatingthedwellings

. Choosing the next buildingappropriatefortheintervention

.Refurbishthebuildingwith thehelpof volunteersandthe neighbourhood

fortheagreedperiod(2-5years.)

.Negotiatingwiththeownersof theproperty

co-creates the plans of the occupation together with the neighbourhood and the possible future tenants. A erwards, they refurbish the building to meet the minimal demands (with the help of volunteers and the committed citizens of the neighbourhood) and occupy and maintain the building for the agreed period (2-5 years).

La Serre is a typical Communa building. The 8502 property (together with two buildings on its side) used to be a car garage, now it is an empty space owned by the Municipality of Ixelles. A er refurbishment, Communa created 3 types of space in it: the le block contains 4 small refurbished rooms offering living space for people in need of a ffordable housing. The rooms are equipped with small in astructure like tap water, and tenants have a shared bathroom.

In the right block, there are co-working spaces for non-profit organisations and individuals who are working in the creative industry. Some other Communa buildings also have big ateliers and workshop spaces for artists and cra smen.

Probably the most important place is the central communal space, which gives home to a shared kitchen, numerous neighbourhood activities, public workshops, solidarity and second-hand markets, cultural events, and also a bar of which profit is used both for charity and to cover Cummuna's operation costs.

Usually, these constructions are funded om donations (materials and tools), and om the monthly contribution their members pay based on a solidarity system (those who can, pay more, so others can pay less). If there is a need for bigger in astructure at certain sites (such as an electricity generator), they run a crowdsourcing campaign. They also received financial support om governmental organisations thought solidarity and ecological awards.

Primarily operated by volunteers, om 2018 Communa was able to employ its 10 members full time with a compensatory salary for investing in the operation of the organisation.

Communa also developed an internal exchange currency for the services that the associations could offer to each other within the di fferent Communa buildings. The currency is called SEM (Network Exchange Service) and is based on time unit (1µ = 1 hour) rather than on Euro.

The organisation does not have a fixed formula for what kind of organisations should have access to the spaces they create in the empty buildings in order to achieve a balanced 'ecosystem'. Apparently, they intend to remain as open as possible when it comes to finding new tenants upon a new building becomes available. They believe, that facilitating access to these spaces should empower the citizens living in the neighbourhood, enabling everyone to participate in the construction of the city.

The selection process for future tenants (residence or organisation) therefore happens together with the active members and representatives of the neighbourhood, an occupant om another Communa site and a member of the Communa crew. These organisations can have di fferent aims: many associations focus on the support of the most vulnerable, with access to decent housing and other social support. Others use this opportunity to carry out cultural or artistic projects, and sometimes the aim is just to create a meeting space for people with di fferent backgrounds or to organise workshops where people can develop new skills.

The associations in the 10 buildings currently occupied by Communa are interconnected with social and economical networks optimising the management of available resources.

One resource, for instance, is food. Communa puts great effort in reducing food waste, so they have regular shipments om grocery stores with unsold uits and vegetables. Some of the food is used at various cooking events where food is prepared with the help of volunteers and served for ee. Many of the residences have solidarity idge with ee food for people in need. The management and distribution of this food is centralised in Le Septante 13, while the ee dinner events usually happen in the community kitchen of La Serre. Some other buildings have a profile focusing on material reuse, and up-cycling workshops, they are in charge of managing resources such as surplus construction

material or tools. This ecosystem also provides some sort of security for the case if the occupation period comes to an end earlier than planned, and residence or organisations can easily find space for themselves in another Communa building (if they could not manage to find a permanent place elsewhere till that.)

The aim is however not necessarily to facilitate the temporariness of such organisations, but to find a way to make them feasible and financially independent on the longer term.

In the case of emergency living units, they do not just wish to offer accommodation, because that alone would not solve the issues connected to precariousness and exclusion. What they wish to achieve is an integrated empowering process, where the accommodation is supplemented by social support, professional integration and skill-building. The whole process happens within a very open and supportive community, making sure that till the end of the occupation period residence will be able to move out to a permanent place and integrate back fully in the society.

'Zin TV' has his offices at Buissonnière and shows his work at the Tri Postal.

Residency+ Workshops

300 M2

since 2017 February

Distribution centre for the unsold supermarket food, sent to other Communa residences.

BINÔME10 living units, 560 M2 since 2018 September

BUISSONNIÉREResidency + Workshops

500 M2

"100 PAP" share the offices of Cygnes and sell their beers at the two bars

TRI POSTAL Workshops

1340 M2 since 2019 November

"Chant Pour Tous" organizes its sessions at La Serre and at Le Septante 13.

'Diogenes' has its offices in La Buissonniére and supports people housed in Binome.

'Hu Needs' has an office in Cygnes and supports people housed in Binome.

The 'Solidarity Fridge' at Binome was formed at Cygnes.

CYGNES

Workshops

500 M2 since 2019 November

since 2017 October residents volunteering/ organising programs sharing tools/resources/food

The occupants organize events also in La Serre.

The volunteer team of the bar at La Serre comes as a reinforcement in case of bigger events at Tri Postal

"Singa" organized activities at both places.

"Le Moussap" is sold at La Serre and Tri Postal and its creator is a resident of "Deux-Pontes"

"Thursdays Makers" are created by the occupants of these 2 places.

LA SERREResidency + Workshops

850 M2 since 2017 March

-

Residency

250 M2 since 2017 March

'L'Outilthéque' provides tools for the collective workshops

Workshops

200 M2

since 2017 December

A resident of Deux-Ponts volunteers at the La Récup'.

'Gilband' makes workshops with the La Récup'

'Gilband' created the Tri Postal sign. Provides materials for construction sites and projects

ABC

-

465 M2

since 2018 October

Client: CLT Brussels

As an organisation mainly consisting of young lawyers and social workers, my role as an architect within Communa's operation was a central question for me om the beginning.

A er studying their operation method throughout previous and ongoing occupation projects, and throughout our discussions, it became clear for me, that the biggest challenge they face is connected to the notion of constant relocation. Temporariness is not yet incorporated into their construction mode: they hardly ever dismantle and reuse the structures they made at previous sites because of the lack of preliminary design. Understandably, since the building happens quite organically as donated materials become available. However, controlling this working method could lead to limiting the creativity that volunteers can bring in. Finding the balance here as a designer is a challenge I would like to take, saving them some time and materials that could be reused.

This is om what the idea emerged, that it would be great to have some permanent structural elements, that would provide the basic in astructure that they always need at the beginning of the occupation.

While primarily Communa has more object-like or furniture-like elements, they are open to extending their field of operation to vacant building sites with empty plots and construction sites, where the construction has not yet started and is currently on hold.

To narrow down my search, I looked at building sites that are owned by the Community Land Trust Brussels - a new player in the city's a ffordable housing market - who have already collaborated with Communa and would certainly be open for a socially oriented temporary intervention.

Community Land Trust Brussels has many sites, where the acquisition had happened already, but the construction of the homes have not yet started due to financial issues or due to its complexity and its longerlasting nature (e.g. long participative planning process). Therefore these plots can remain empty for many years, sometimes even for a decade, which is a long enough period for a temporary project.

According to the aerial photos and the website of CLT Brussels, currently there are 3 empty plots owned by CLT Brussels.

Comparing the sites we can see that they all have very similar geometric characteristics (long narrow plots perpendicular to the street), with one or two fairly high firewalls on their longer sides (offering potential structural support).

Since the design project on the first site is the one

that is still in its initial phase, and on the other two the construction is about to start, I decided to continue working with this one.

On the longer term, it would be also interesting to see whether this urban tactic could be implemented on the building sites of other land owners, or, even in other cities and countries. Furthermore, CLT Brussels is currently working together with Communa in a recently purchased building, where Communa is organising community activities until the refurbishment of the building would start.

The amework of the project starts to take shape as we combine the time-line of Communa and CLT. We can see, that the assembling of the temporary building should not take longer than 1-3 month, so even in the worst-case scenario, there would be a 2-year-long period of tenancy.

Feasibilitystudy

Landacquisition

EMPTY

Assemblingtheprojectteam

Designandplanning

Construction

SITE 1. SITE 2.

SITE 3.

Accommodatingthedwellings

Supportforco-ownership

TIME LINE - REALIZATION OF A CLT BUILDING

Intermediatetime:<Artresidency, <Solidarityhotel <rentouttoraisemoney?

COMMUNA

The time gap between the previous and future use offers the opportunity to experiment with alternative building techniques opposed to the marketdriven building industry. Dedicating themselves to environmental activism, occupation projects are also platforms to experiment with environmental iendly solutions, building the temporary interventions out of reused or up-cycled waste material found on-site, or out of donated products that building material re-sellers could not sell.

There is also a new phenomenon unfolding called pre-cycling 1 , that regards buildings as material banks, where construction elements are assembled with joints that do not harm the material (with for example industrial belts or cable ties). As the occupation comes to an end, these elements can be disassembled and either returned to the construction material reseller or shipped to another site to construct a new building there. This approach could also be part of an advertising campaign, where construction companies offer materials with their logos on it for ee for the temporary intervention.

To commit themselves to environmental iendly construction modes and to meet circular-economy requirements on a budget, Communa developed its own network connecting those who have materials to offer or are in need of it.2. Additionally to their operation, this network also facilitates other sustainability-driven collaborations between di fferent entities (including governmental organisations, companies, NGO-s and di fferent recovery platforms).

Although, occupiers can save significant amount of money on building om such materials, working with reused materials requires experience and expertise in construction techniques and material knowledge in order to prevent degradation due to possible material damage or aging.

Generally temporary structures are built for public functions, creating spaces for short-term events such as festivals or temporary cultural events. They have a special character, that is somewhere between outdoor and indoor spaces. Their structures usually offer protection om rain and wind, and provide shading, but - in order to reduce material expenses- they do not necessarily tackle issues that are mandatory for domestic spaces, such as adequate thermal and sound insulation.

Looking at the wide variety of movable domestic spaces 3., 4 we can see, that in almost all the cases the

mobile home is transported in one piece (or in bigger pieces) with the help of cranes and heavy transport. This approach seems to be the fastest and the most efficient one, however, the created spaces are very limited in terms of spatial flexibility; are very small in their sizes (offering space for 1 or 2 people, maximum for one family); and the homes are custom made products, designed and constructed for a very high price.

There is also a growing trend of installing mobile container homes on empty terrains to provide emergency municipality housing 5.,6 , but interviews show 7 that this is not the kind of architecture that tenants desire, as these fairly small homes are lacking space for storage, there is no possibility to personalise and decorate these spaces, and in addition, they do not have adequate thermal qualities especially on hot summer days. On the other hand, a container complex serving as a homeless shelter in London shows that these emergency homes do have the potential to create adequate personal space, but only if the future tenants are actively involved in the formation of these spaces, creating a sense of ownership and belonging.8. Furthermore, the project seams to be successful also in empowering the homeless individual, who can gain new skills and confidence while taking part in the refurbishment works.

Inspired by the empowering effect of building one's own home, I started looking at temporary projects, where the structure was made without using custom made elements, built together with volunteers and future users.

There is very little research about the degradation of such materials within the architectural discourses, but the Brussels based company Rotor has interesting studies investigating the topic. 9 In the book 'Usures : how things stand' it examines how the sign of wear gives us information about our environment, and how recognising the traces that users leave on their environment would help us design better and more environmentally cautions buildings.

It also highlights the importance of maintenance in order to preserve the original qualities and extend the life-cycle of the objects. The study highlight the di fferentiation between aesthetic value and functional value, pointing out that in certain case (e.g. patina) wear can even heighten our assessment of the visual qualities of an object.

It is important to recognise the agency that maintenance offer for its users. While taking care of it to prevent degradation, it gives the opportunity to add their personal touch to the environment that surrounds them.

A er setting some constrains to guarantee a feasible solution, I collected building components that are durable and have dismountable connections in order to be re-usable; that can be constructed and dismantled within a really short period of time; and where elements were ready made products, which could be purchased om regular building material shops. At the same time, it was important that these construction should have an educative/community generator aspect, therefore I selected only those projects, where the assembly technique did not required special skills. Lastly, I focused only on those techniques, which would enable a rich variety of floor plans, in order to avoid rigid, repetitive spatial results.

Based on these criteria I assembled a reference building catalogue and evaluated their building components. As at temporary projects the time and the budget are the two most important factors, I aligned them within a matrix based on how fast is it to assemble them and how low their material cost would be.

I made di fferent categories for structure, partition, infill, and foundation. Ideal components are situated in the top right corner.

For the evaluation I relied on prices and data available on the websites of Belgian material re-sellers. For estimating the time the general rule was, that the smaller the building components are, the longer it takes to assemble them.

PRICE: LOW

ASSEMBLING: SLOW

PRICE: HIGH

ASSEMBLING: FAST

perforated

PRICE: LOW

ASSEMBLING: SLOW

ASSEMBLING: FAST

ASSEMBLING: SLOW

INTERNAL PARTITION

ASSEMBLING: FAST

PRICE: LOW

PRICE: HIGH

re-used waste wood “bricks”

cement-fibre tiles

2x36x40

pvc mesh tarpaulin

x126 1 €/ 2 kg kg plastic sheets

tied concrete brick

12x48x 12 €€€ kg kg kg

timber cladding

2.5x 20x 240

7 €/ 2 kg kg

2 €/ 2 5 kg/ 2 ‘ClickBrick’ 6x 18x6 17 €/ 2 kg kg kg kg

polycarbonate wall panels 14 €/ 2 kg

x 220x 3 €/ 2 2 kg/ 2

Papercrete brick 15x 15x40 5€ kg kg

textile curtain 0.01x x 4 €/ 2 kg kg

‘knitted’ OSB panels

2.5x 120x 270 8 € / 2 kg kg

metal sheets

x90x45

8 €/ 2 kg kg

PRICE: HIGH

‘JUUNOO’ steel ame 0.12x60x 17 €/ 2 kg kg

‘knitted’ OSB panels

2.5x 120x 270

8 € / 2 kg kg

plasterboard wall panels

7 €/ 2 kg

timper post paneling

x90x45

8 €/ 2 kg kg

polycarbonate panel 7 5x 120x 260 15 €/ 2 kg

Extra attention was paid while choosing the foundations, since they have to adapt to various site conditions as the mobile homes travel om one site to another.

There is no category comparing installations, however, I dedicated some time also to research independent and/or demountable piping, heating/ cooling and electricity systems.

Examining the high level of complexity that buildings reach today with their fine-tuned, meticulous systems to provide the perfect thermal and acoustic conditions made me realise, that the biggest issue will be to figure out how to connect to the city's centralised in astructural system within a really short period of time; or alternatively, find a way to providing electricity, water and heating for the homes. Most certainly this phase would certainly slows down and significantly complicate the construction.

Therefore I collected systems that have either easily removable elements, or have the opportunity to work in a de-centralised manner. Many of the examples were inspired by nomadic settlements, or historical examples om well before centralised systems were invented. Wile reading Sébastien Marot's chapter in Elements of architecture10. it was interesting to follow how, for instance, hearty in a portable pot - a very temporary

element - evolved into a fixed and fully-integrated heating system that is now an essential part of every domestic space.

The director of QED Properties, a company providing container homes for councils to set up emergency homes on empty lands, has a futuristic idea for solving the issue of in astructure. He envisions a site strategy, where pipes and ducts are readily installed on empty properties, so homes can be plugged in and out as temporary homes circulate around the city or around the globe. 11

:

1. "Pre-Cycling," umschichten, accessed March 22, 2020, https:// umschichten.de/pre-cycling/.

2. Communa ASBL, Rapport d’activité 2019, (2020), http://www. communa.be/rapport-dactivite-2019/.

3. Rebecca Roke, Nanotecture: Tiny Built Things (London: Phaidon Press, 2016)

4. Rebecca Roke, Mobitecture: Architecture on the Move (London: Phaidon Press, 2017)

5. Patrick Butler, "'They Just Dump You Here': the Homeless Families Living in Shipping Containers," The Guardian, last modified August 23, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/aug/23/they-just-dumpyou-here-the-homeless-families-living-in-shipping-containers.

6. Stephen Burgen, "Sardine Tins for the Poor?: Barcelona's Shipping Container Homes," The Guardian, last modified February 3, 2020, https:// www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/sep/06/sardine-tins-for-the-poorbarcelonas-shipping-container-homes.

7 Kyra Hanson, "What's It Like Living In A Shipping Container?," Londonist, last modified September 14, 2017, https://londonist.com/london/ housing/what-s-it-like-to-live-in-a-shipping-container.

8. Kyra Hanson, "What's It Like Living In A Shipping Container?," Londonist, last modified September 14, 2017, https://londonist.com/london/ housing/what-s-it-like-to-live-in-a-shipping-container.

9 . Rotor, Usus: état des lieux; Usures : how things stand (Bruxelles: Communauté ançaise Wallonie Bruxelles, 2010)

10. Sébastien Marot, "fireplace," in Elements of Architecture, ed. Rem Koolhaas (Köln: Taschen, 2018)

11. Rosie Spinks, "What if the Future of Housing Means Accepting That a Home Isn’t Permanent?," Quartz, last modified February 27, 2019, https://qz.com/1542887/london-provides-low-income-housing-in-modularshipping-containers/.

During the semester I worked out the design of a series of easily dismantlable living units, that future tenants can assemble within a short period, and which could be dismantled and shipped to the next building plot before the construction of the permanent building would start.

While working out the details of the design, I elaborated on the nature of such flexible and constantly changing constructions; the problem of constant relocation and its possibilities for learning and improvement; and issues connected to the possible degradation of the provided in astructural and structural elements.

Instead of a fixed design, the intention was to work out a modular system, within which a wide variety of floorplans would be possible every time the structure would be re-assembled on a new site. This would eliminate the risk of reducing the self-builders into the position of plain executers and would assure their involvement in the design process.

The ownership of the building elements and the operation of the entire process would be executed with the help of Communa, while the building process

could be supported by another Brussels-based social organisation called Toestand, who have experience in installing temporary structures.

A er assembling the building component matrix, I chose 3 of the fastest and cheapest components and constructed a possible volume for each on the site. Working out in details one module for the 3 most promising solutions, made it possible to compare them based on their durability, assembly time, weight and how easy would it be to transport them.

The third option, the timber box ame seemed to be the best solution, so I continued working out the assembly method step by step:

The construction starts with installing the foundations and the piping, and would be followed by laying the floorboards, li ing the timber ame boxes with a mobile crane, adding the structural partitions and placing the structural boxes. The ceiling structure is carried by the firewall and the box ames on the other side. A er installing the skylights and the cladding with the thermal insulation between its layers, the roof can be placed.

The measurements of the elements are all synchronised to materials available at building material resellers.

The grid is more visible om the top view showing the rhythm of the structure, where one unit consists of two grid elements. The ee floor is divided only by

curtains and shelves. There are di fferent floor-plan variations for single people or couples, students and bigger families occupying two units. The communal space is situated on the street side with the big kitchen. Important element is the temporary fence that serves as a communication surface about Communa‘s events and about the future of CLT homes.

TONIGHT DINNER WITH CONCERT!

c om mun a

c om mun a CONCERT CLT BXL HOMES SOON!

The garden around the homes serves as a semipublic space, but is also a productive garden, where special absorbent plants are grown to clean the possible contaminations om the soil.

The character of the garden also changes according to its urban context while the homes are travelling to di fferent sites: it would be a playground on the site in Laeken which is in the proximity of schools, or an outdoor gym on the site in Anderlecht, which is right next to a soccer field.

Because of this constant relocation and the assembling/dismantling of the elements, there needs to be a quality check on a regular basis to correct possible material damages. If the lifespan of a building component comes to an end, elements can be easily changed, since the module of the buildings were synchronised with materials available at building material re-sellers. This maintenance and care becomes visible on the appearance of the settlements which could give a special personal touch to its overall aesthetic.

Facilitating access on the muddy terrain

Cleaning contaminated soil

MUSTARD GREENS + Lead + Cadmium + Nickel + Zinc + Copper

BLADDER CAMPION + Zinc + Copper

ALPINE PENNYCRESS + Zinc + Cadmium + Mercury

Soaking up excess water

Site requirements

WILLOW TREE + Copper + Zinc

+ Selenium + Uranium + Petrochemicals

SUNFLOWERS + Radioactive metals + Uranium + Cesium + Methyl bromide

Absorbant plants that can clean the contaminated soil

Maintenance through time

Maintenance through time

Maintenance through time

Maintenance through time

Academic Promotor: Martino Tattara

International Master of Science in Architecture

KU Leuven, Faculty of Architecture, Campus Sint-Lucas Brussels

June 2020