This study was completed as part of the BSc Architecture course at the University of the West of England. The work is my own. Where work of others is used or drawn on, it is attributed to the relevant source.

This dissertation is protected by copyright. Do not copy any part of it for any purpose other than personal academic study without the permission of the author.

Thank you - to my supervisor Mina Tirashi, for her continuous support throughout the writing of this work, and for allowing me to pursue my interests freely within this field of study.

ii

A B S T R A C T

An enquiry into Egyptian placemaking at the intersection of Pharaonic & Arabic architecture.

Architecture 2020 - 2021, Rodayna Abdelaziz

The dilemma of Egyptian placemaking has altered significantly over the past years due to an amalgam of influences, causing what can be identified as placemaking confusion to arise within contemporary Egypt. This is evidently seen in the form of clustered cityscapes and faceless red brick buildings of that which lack native accent and give no indication to what purpose they serve. While the story of Egypt speaks of Pharaonic and Arabic architecture, the integration of these two styles has delivered two forms of very different cultural imprints. This study rises from the dire need to understand the dynamics of Pharaonic and Arabic architecture, and how they realise themselves in the context of Egyptian placemaking for the reason of underpinning how they had succeeded to reflect Egyptian tradition and values.

To understand placemaking of the two architectural styles, this study will undertake a case study approach into investigating the features of inhabitable and monumental spaces that give Pharaonic and Arabic place purpose within context. The Pharaonic village of Amarna, which due to its geographical location and placement, had remained unaffected by the annual flood of the Nile subsequently allowing the preservation of architectural remains left inland, will be investigated to identify how ancient Egypt had reflected its tradition through design. Meanwhile, the village of New Gourna, developed at the hands of architect Hassan Fathy, will be examined to identify how Arabic design has been tailored to the needs of the people and allowed the application of architecture that reflected tradition.

If placemaking can help resurge interest in identity and cultural heritage as an agent to reinforce place identity – and it must – then, over the years, placemaking of Egyptian cities can serve as a foundation to orient views towards cohesive solidarity, individuality exploration and rootedness that is much needed today for the issue placemaking confusion mentioned prior.

iii

iv

Introduction Methodology

Chapter One: Understanding Pharaonic Placemaking Understanding Arabic Placemaking

Chapter Two: Case Study: Amarna Case Study: New Gourna Conclusion List Of Figures List Of References

v 17 20

C O N T E N T S

11 13 03 07 23 25 26

1

Culture springs from the roots And seeping through to all the shoots To leaf and flower and bud From cell to cell, like green blood, Is released by rain showers As fragrance from the wet flowers To fill the air. But culture that is poured on men From above, congeals then Like damp sugar, so they become Like sugar-dolls, and when some Life-giving shower wets them through They disappear and melt into A sticky mess

- From Architecture for the Poor, Hassan Fathy 1969

2

I N T R O D U C T I O N

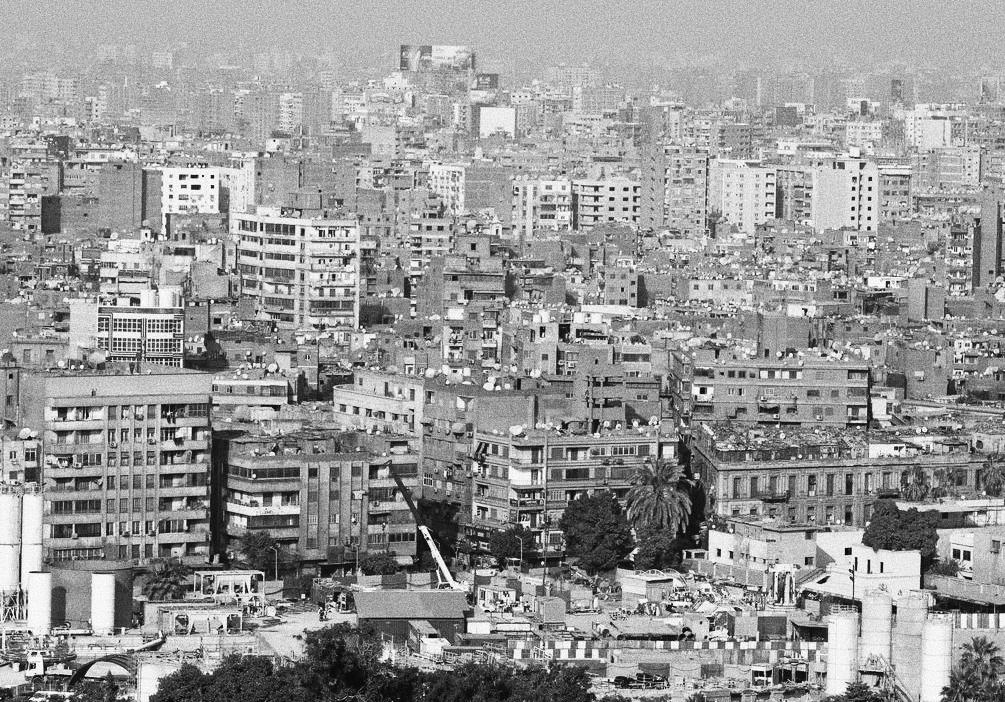

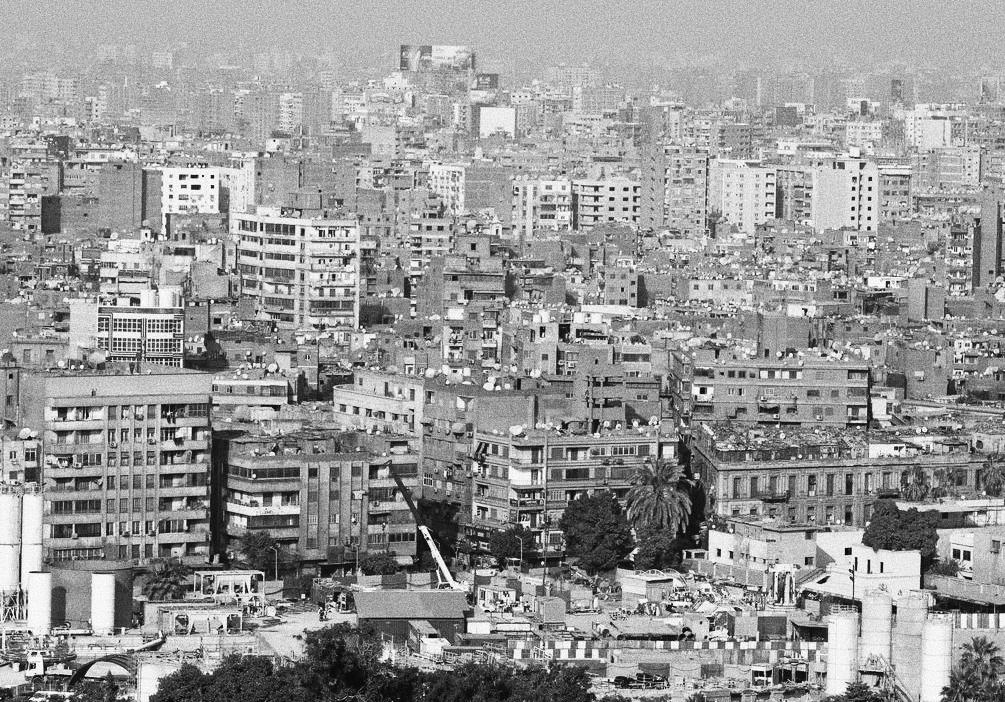

Egypt, like many countries, is a result of an amalgam of influences. Its geographical location gives it a spectrum of trends and movements presented in architecture and urbanism. With change as a constant variable in the age of architecture, Egypt has simulated a series of ‘isms’ including Mediterranean-ism and Middle Eastern-ism in association with postmodernism, historical revivalism, and critical regionalism (Salama, 2007). The search for an Egyptian architectural identity has led to a fall and rise in the ‘isms’, consequently contributing to what can be identified as placemaking ‘confusion’. With a background of the Pyramids and the Nile, the common man lives in an environment far from the reputation given to the land. This can be seen from what abides in its land - Egypt’s cities scape is clustered with reinforced concrete and red brick buildings that form a sense of architecture that denies itself from an Egyptian imprint that reflects identity, tradition, and values. One might assume such builds lie tangible to a certain socioeconomic group, but that is not the case. Even within higher socioeconomic groups, architectural styles and urban forms resemble nothing to that of past or even modern Egypt. This illustrates the dwindling strength of what placemaking once meant on Egyptian grounds.

As a result of improper relation to placemaking, Egypt’s homeland cities and villages are becoming increasingly ‘ugly’. Taking the form of cramped square boxes of assorted sizes where the ‘shoddy’ execution of the work has driven people to occupy houses with no native style. Not that the lack of Egyptian signature is compensated for an adequate housing environment, but rather they are compact and outward facing, stuck up all over unmade roads, wire, and dusted lines of washing hanging, and in effect increasing in ‘ugliness’ and inefficiency (Fathy, 1973). The lack of Egyptian accent within Egypt’s built environment is emphasized by Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy as he goes on to say: “I have succumbed to a feeling of helplessness, sadness, and pain for what was becoming of my people and my land”.

3

The architect proposes that the placemaking confusion in Egypt is seen as an issue of style and is regarded as a surface finish that can similarly be applied onto multiple buildings and altered if need be. Evidently, the contemporary situation has abandoned means of Egyptian placemaking that can provide its people with an essence of cohesive solidarity, individuality exploration and the feeling of rootedness. The contemporary issue has led to futile buildings that stand ill within the contemporary urban fabric, denied their people a holistic human environment for everyday endeavours.

Ultimately, the identity of Egypt goes to speak of two characters. One is the character is that which is regarded as the true lineal descendants of the ancient Egyptians, the Copts, which portrayed architecture in the means of Pharaonic style, and the other is what was believed should provide the pattern for new Egyptian architecture, the Arabic style. Whilst the story of Ancient Egypt can be represented in forms of Pharaonic style with examples of pylons and cavetto cornice, the Arab style is believed to be represented in forms of Islamic architecture with examples of geometric patterns and pointed domes.

4

Pharaonic and Arabic accents within the Egyptian built environment have, for many years, been a bridge that connected their people to their values, culture, and belief systems in built form and so it is important to understand how placemaking within these facets can offer this intangible bridge.

One must first understand how it can be of built form to display or lack identity of place. In his book: “Image of the city” author Kevin Lynch, proposes place identity as the basis of relation, whether practical or emotional in meaning for the observer (Lynch, 1960). As such, one might argue that identity of oneself is entirely subjective. However, the author of this thesis argues place-identity retains a different form as the latter is a collective of multiple persons. The ideology of place identity in itself is one that cannot be measured; in an article on the ‘Interpretation of architectural identity through landmark architecture’, the authors rule that regardless of identity, architecture, much like art, should be autonomous for personal expression and individual creativity in a sense that tradition and cultural context serve as a foundation to orient views towards memories, reality of images or even dreams (Jashari-Kajtazi and Jakupi, 2017). While in juxtaposition, French urbanist Marc Auge, has argued in his book ‘nonPlace’, that places are given identity through the interactions or activities they provide for its users (Auge, 1995). Whereas places that do not facilitate the opportunity for social interactions and/ or encounters are a ‘non-place’ (ibid, 1995).

A research conducted by Kevin Lynch studied mental images people held of a specified city. The research provided evidence that one can relate the identity of place in respect to the experience, senses and social activity provided by such place (Lynch, 1960). To better the case, Hassan Fathy argues that real architecture cannot exist except in a living tradition, where user experience allows the architecture such title.

If one would compile both Jashari-Kajtazi and Auge’s arguments, it would be safe to assume placemaking is connected to what one self-expresses and/or experiences in terms of activity. Thus, it is natural to assume self-expression is interlinked with one’s identity so much as activity is interlinked to culture or beliefs. Then finally, placemaking – can be identified as the execution of work in relation to shared values and beliefs within its specified context.

5

Respectively, placemaking therefore would be deemed successful should it relate to its people, values, and beliefs, where on the other hand failed placemaking would be one that fails to adhere to its contextual and living background.

It is within that ideology that sentimental manifestations are fulfilled in means of subjectivity and solidity. The architectural application drives the resurgence of cultural narrative and links individuals to culture and collective values. The unfortunate reality of the country’s contemporary built environment calls on the need to understand the dynamics of Pharaonic and Arabic architectural styles and how they realise themselves in placemaking.

6

M E T H O D O L O G Y

One must first understand the component parts of Pharaonic and Arabic placemaking to identify them in a contextualised dynamic field. Therefore, this study initially adapts a desk-based approach to introduce and understand Pharaonic and Arabic architectural styles within context of time and place.

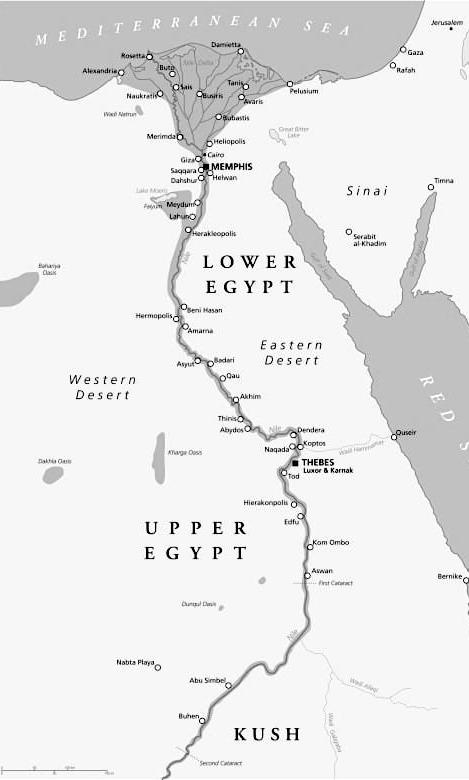

It is important to note that the civilisation of Egypt dates to its unification around 3100 B.C. Although not clearly recorded, ancient cities come into focus more clearly during the second millennium BC in comparison with earlier periods. In consideration of this, this study will then, adapt a case study approach into the architecture of the ancient administrative centre: Amarna – the founded capital after Thebes, to demonstrate an understanding of Pharaonic placemaking within Egyptian context. The study will go on to similarly examine the Egyptian village: New Gourna – the traditional mud brick porotype town developed by Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy, to demonstrate an understanding of Arabic placemaking and reflection of adaptability to the local environment within Egyptian context.

Finally, this study will conclude key findings of Pharaonic and Arabic architectural styles, and how both dynamics draw on one another collectively and independently towards Egyptian placemaking in order to understand how contemporary Egypt can learn to reinforce placemaking within its built environment.

7

8

9

All the land… Watered by the Nile in its course was Egypt, And all who dwelt lower than the city Elephantine (Aswan) And drank of that river’s water Were Egyptians.

10

PHARAONIC PLACEMAKING

01 UNDERSTANDING

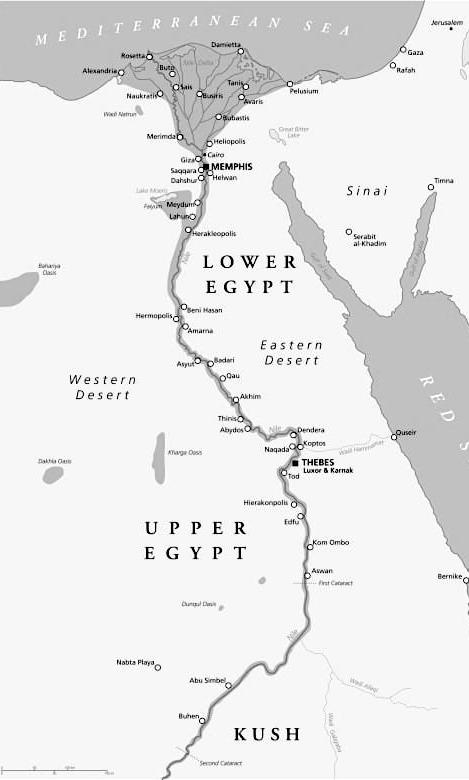

The civilisation of ancient Egypt is among the greatest river-based cultures of the Mediterranean basin. The Nile River has provided its inhabitants with means of sustenance for centuries, and the earliest of identifiable cities date back to the union of Upper and Lower Egypt by Menes, pharaoh king of Upper Egypt, who established his capital at Memphis, near the junction of the two lands (Fazio, Moffett and Wodehouse, 2008). In this era of renewed power, Egyptians lavished on expressing personal and collective values in forms of beauty and art. They cared deeply on matters of religion and death, and their belief in an afterlife had shaped the way inhabitable space was built.

Life in ancient Egypt had evolved around the annual cycles of the Nile, and the everchanging rhythms of the seasons had played a role in the survival of Egyptian cities. The archaeological problem of the latter, was that the Nile’s annual flooding affected evidence of towns situated along the river stream, causing deposit mud to bury any traceable remains underground. For the main part, civic buildings, houses, and palaces were made using sun-dried mud brick or of reed, thatch and wood materials while temples or tombs were either built or carved from stone (Gates, 2003).

In expression of commemorating pharaohs and formally worship the gods, temples of vertical columns, horizontal roofs and sloping pylons were created to allow for such tradition.

11

The design compositions of balance and lines were inspired by axial landscaping of Egypt’s environment; consequently, the buildings conformed to their surroundings (Murray, 2009). Not only did the temples correlate to earth, but researchers have further discovered the alignment of 350 temples in relation to the stations of the sun; accumulating to approximately 95% of all preserved temples existing in the country (Belmonte et al., 2010). In Pharaonic temples, capitals which are the topmost member of a column, are ornamented with papyrus, lotus, bud, or a combination of the following decorative elements, a form of reflection from their surrounding environment; the River Nile (Curl, 1994).

It is important to understand that culturally linked aspects of built forms tend to lead to a position of belief that knowledge, truth, and morality exist in relation to culture, society, or historical context and are not absolute. As proposed by Amos Rapoport in his studies on house form and culture, as soon as a given culture or way of live has changed, its form would be of no purpose and that even though its ancient settlements may still be used, their meaning alters profoundly. This puts great emphasis on placemaking in relation to time and sheds light on why the Pharaonic style and architecture of ancient Egypt is no longer fulfilled in a contemporary dynamic. It also means that while Egypt carries a great lineage of ancient culture, placemaking that reflects Pharaonic architecture in the modern-day society would deem itself false to its people for the circumstance that values and traditions has altered.

12

UNDERSTANDING ARABIC PLACEMAKING

The conversion of Middle Eastern tribes to Islam, brought in an intense awakening of Arab fervour within the region. The ideologies of Arabic architecture were introduced with Arab Moslem conquerors and are thus closely linked to Islamic architecture. Like many countries, Egypt had been architecturally altered to host forms, for and in expression of Islamic religious practice. Religion affects the form, plan, spatial arrangements, and the orientation of houses (Rapoport, 1969). From the allocation of minarets to call upon prayer, to the orientation of prayer halls, the application of the religion required for the architecture to respond accordingly.

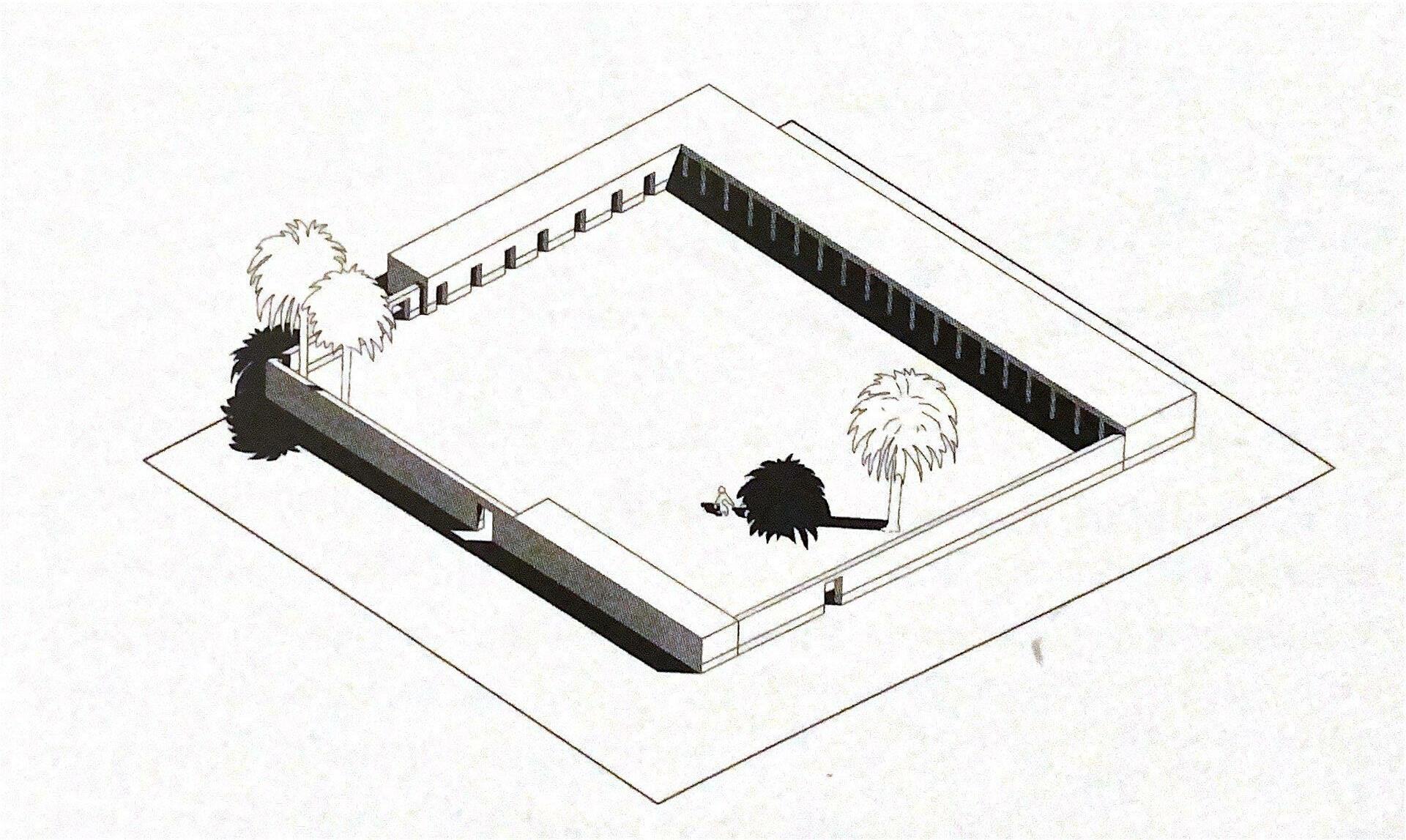

The conception of prophet Muhammed’s house for example, served as a porotype for the design of an Arabic Mosque. Composed of a square enclosure with a central courtyard and small chambers in the southeast corner of his living quarters, the space allowed for followers to gather for sermons and perform group prayer (Fazio, Moffett and Wodehouse, 2008), and so it allowed for people to come together in social solidarity to undertake a collective practice founded on the core principle of shared belief. Although domestically designed, the spatial organisation within the prophet’s house was subsequently one that similarly needed to be applied within a mosque. One may further propose that the spatial arrangement of the prophet’s house would deem itself functional for religious practice if applied in the contemporary fabric of Arabic households.

The Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy further identifies the Arab courtyard house with its novel expressions as the model for his own environmentally underpinned and culturally rooted architecture (Rabbat, n.d.). Fundamentally, open courts had realised themselves as an instrument to living tradition within the context of Arabic placemaking. On the contrary, it can be argued that open court spaces within contemporary housing environments are neither of great use nor demand. The role of traditional Arabic courtyards is today pursued by mosques and multi-functional religious spaces. The spatial requirement for that function is thus compensated for, and the initial domestic space is instead used for another purpose.

13

Nonetheless, it remains evident that such Arabic spaces are designed in reflection of living values and beliefs.

Liturgical elements integrated within a mosque such as minarets - that call people upon prayer, and mihrabs - that form a niche in the wall at the position closest the holy mosque of Mecca, are often expressed in non-traditional but vernacular ways. It is nevertheless important to realise that such elements have the capability to enhance the Islamic identity of a place (Fugate, 2015). This can prompt the resurgence of interest in historical and cultural heritage as a strong agent to reinforce place identity in response to identity abandonment issues (Akkar Ercan, 2016).

While mosques are designed to form coherent spaces for religious practises, other features of Islamic architecture present themselves as an additional variant to Arabic placemaking. Geometric patterns for instance, are both linked with monumental and domestic adornment. Patterns of geometry and Arabic calligraphy are in many cases integrated within interior space and used all across the Middle East for the decoration of place during traditional periods such as the holy month of Ramadan –even though aspects of this may be regarded as a surface finish as raised by Hassan Fathy prior, this type of ornamentation had evolved to adhere to societal and religious beliefs, and in essence allowing a more subtle form of Arabic expression within interior facets of the built environment.

figure 1 Reconstruction of the House of the Prophet, Medina, ca. 622.

14

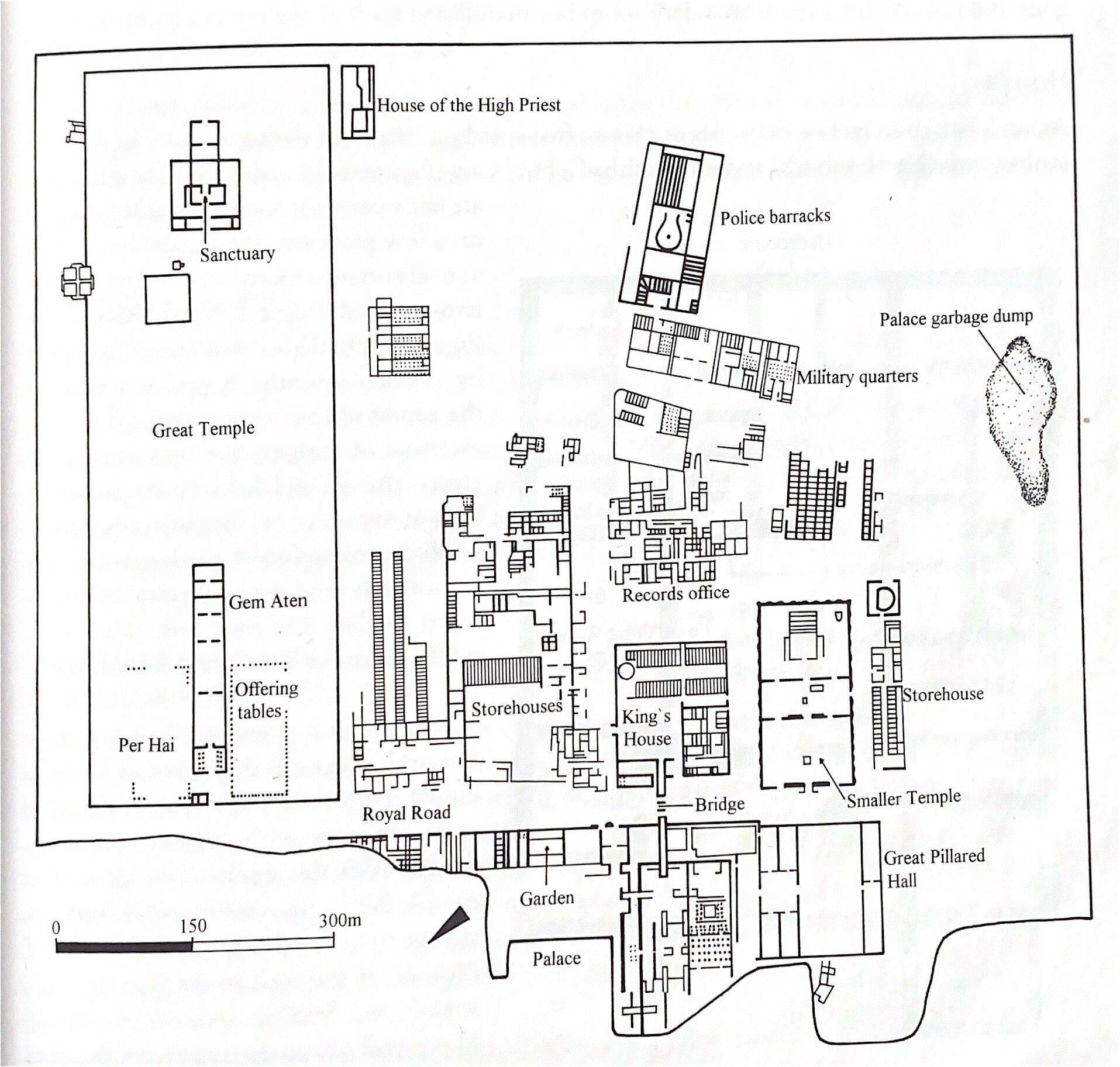

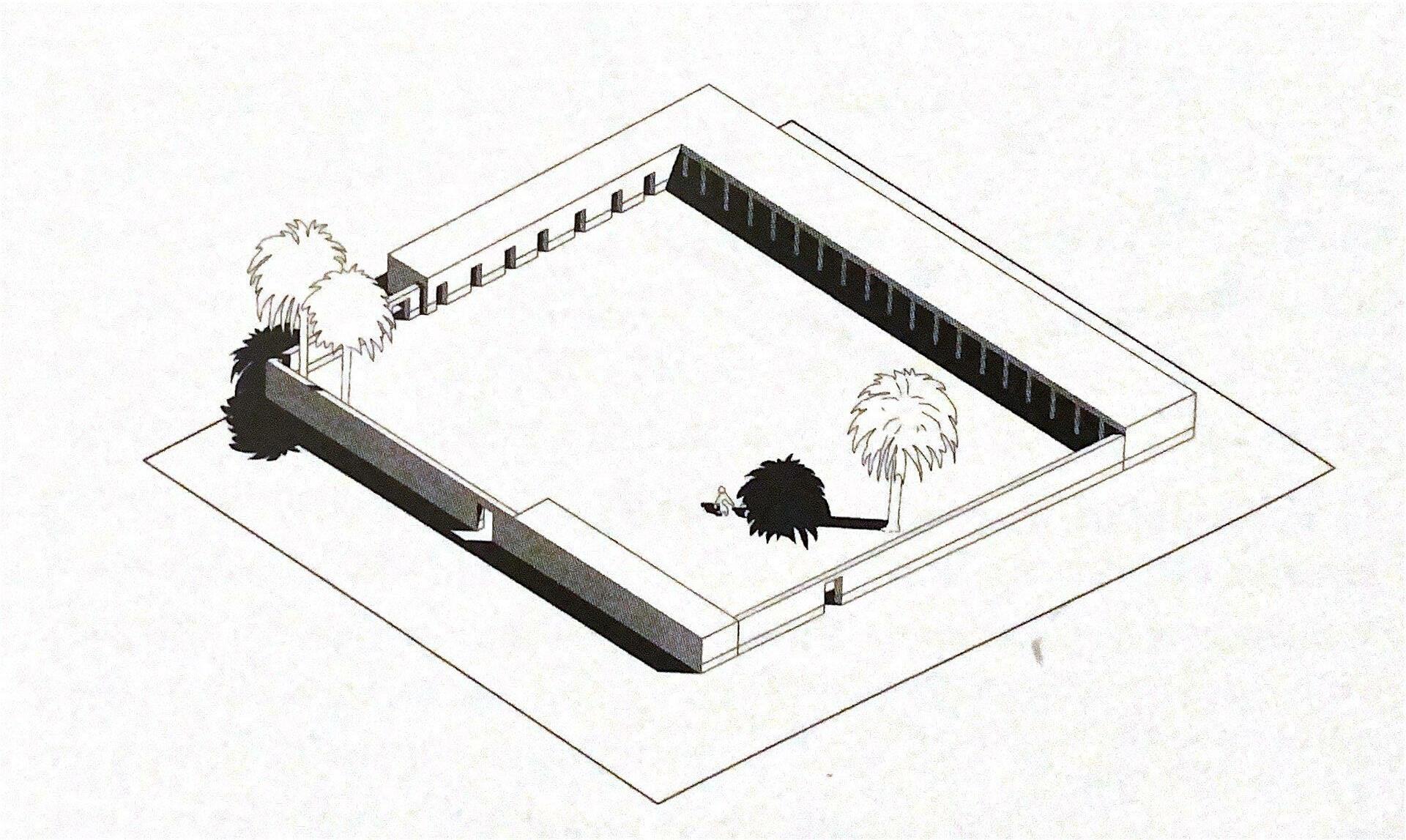

figure 2 Plan, city center, Amarna

15

Waset is the pattern of every city, Both the flood and the earth were in her from the begging of time, The sands came to delimit her soil, To create her ground upon the mound when the earth came into being. Then mankind came into being within her; To found every city in her true name Since all are called “city” after the example of Waset.

(Seton-Williams and Stocks 1993:536)

16

CASE STUDY: AMARNA 02

Occupied for a brief period, Amarna remains among the most complete examples of an ancient Egyptian city, at which a contemporaneous urban landscape of cult and ceremonial buildings, palaces, houses, cemeteries, and public spaces had been preserved and so revealed to provide insight into Pharaonic making of place (Stevens, 2016). In accordance with the studies of Charles gates on the architecture of ancient cities, by the fifth year of the god Amun’s reign, also identified as Akhenaten, the capital of Egypt was moved from Thebes to Amarna. Amarna consisted of a village that was located halfway between Thebes and Memphis. It had an extremely short life and because of the village’s geographical location and placement, the town remained unaffected by the annual flood of the Nile, and so any architectural and archaeological remains left inland had been preserved.

As a result, the ruins of Amara give a coherent study into ancient settlement planning, the shape of society, and the essence in which ancient Egyptian cities functioned and were experienced at the time.

The city plan of Amarna for start, portrays how the urban fabric in ancient Egypt was arranged to adhere by status and function. For instance, small houses tended to cluster around larger estates; such arrangement suggested that occupants were able to provide services for higher statutory officials in exchange for goods. Additionally, the variations of house sizes within the city, allowed an opportunity to model the socio-economic profile of Amarna (Stevens, 2016).

17

For the case of worship, temple space was of vital importance to celebrate rites for the sun god. The large open courtyards held traditional ceremonies, similar to that of Islamic architecture, the courtyards would contribute to the gathering of the people, and so they were planned to be directly lit by the sun (Gates, 2003).

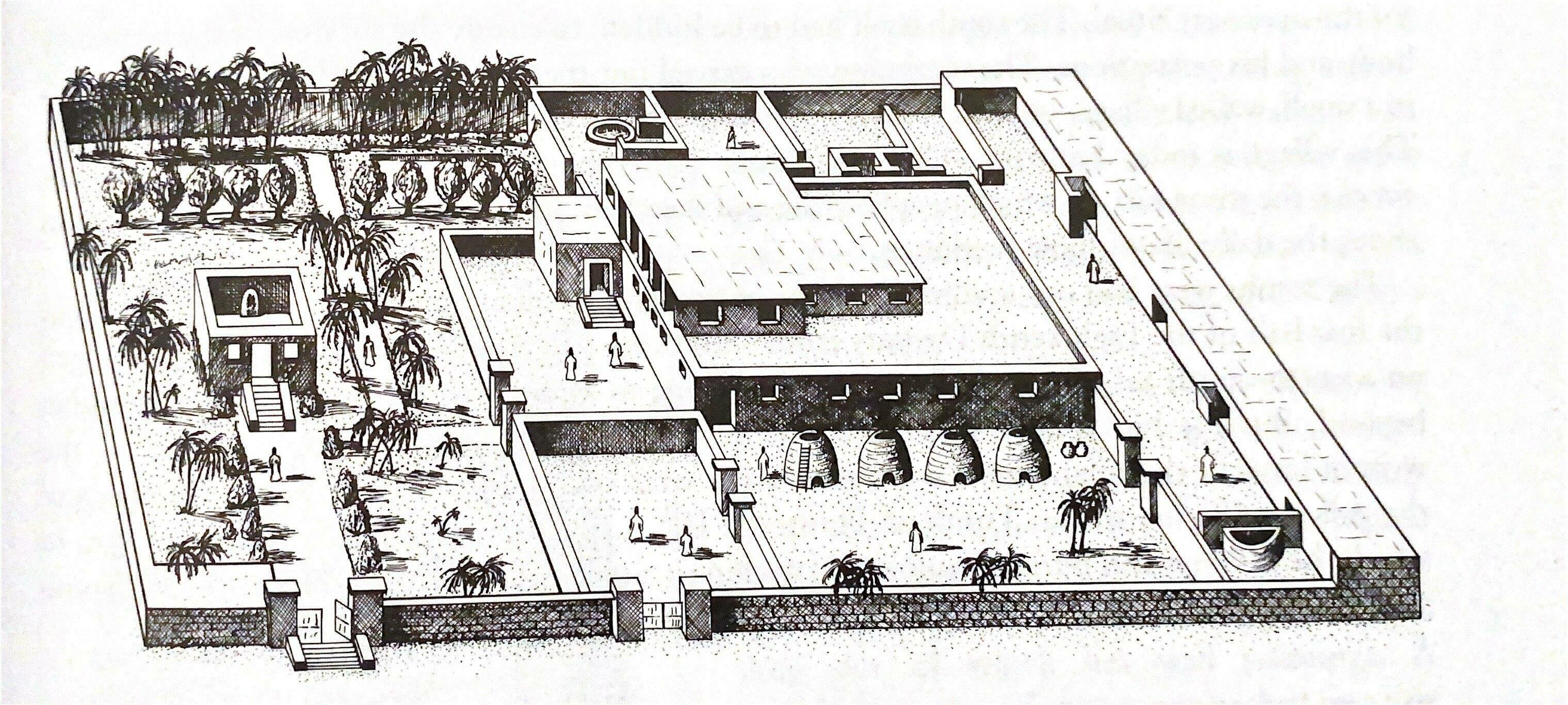

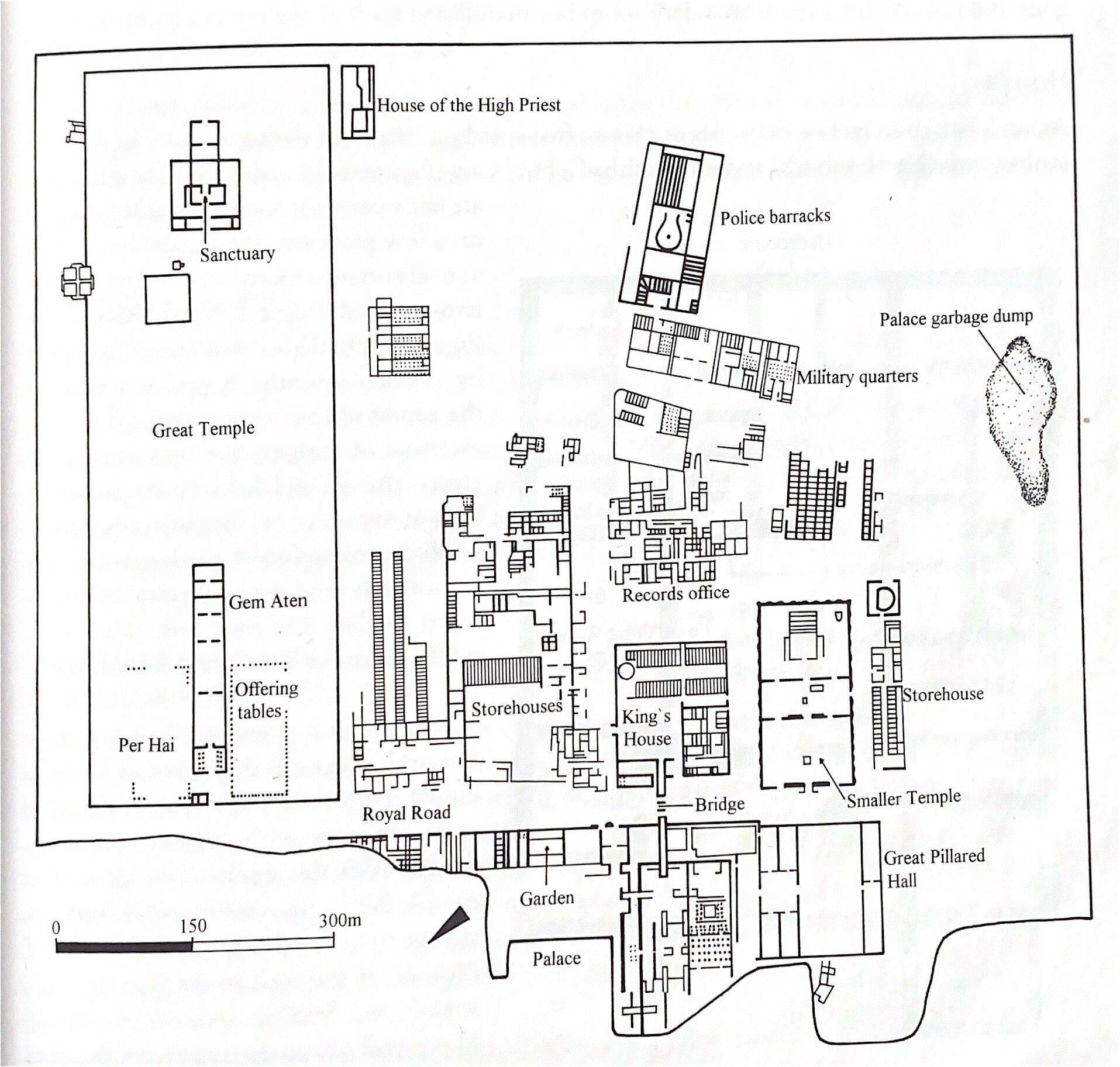

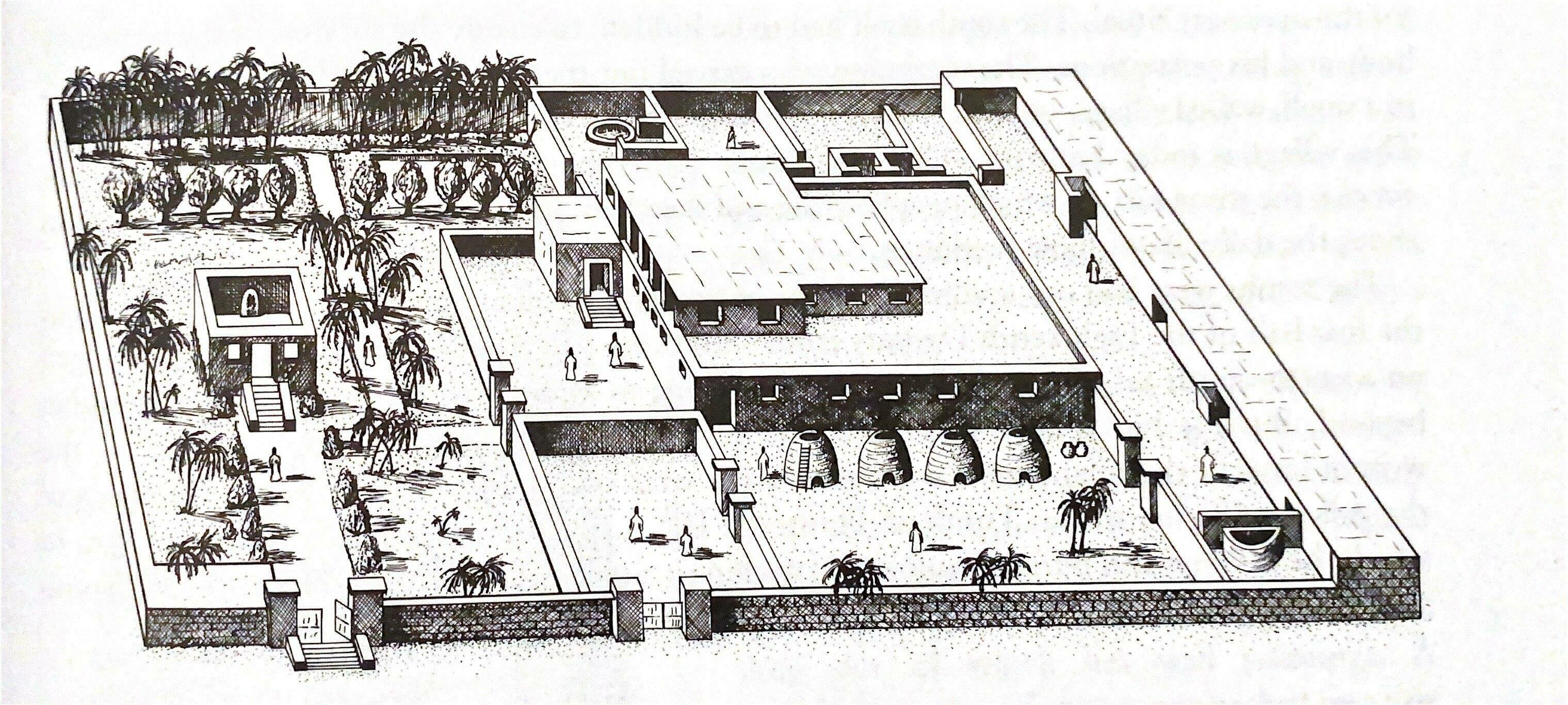

Similarly, to Arab style housing units, the private houses in Amarna adapt consistent and moderate features. Generally raised, on a platform and by wooden columns, the spatial parti of the interior accommodation consists of a central hall insulated by surrounding rooms, a servant’s quarter, and a shelter for animals (Gates, 2003). Ornamentation was rather simple, consisting of plastered walls and in some cases painted motifs of cultural geometric design. The landscape was further adorned with a garden of trees, food plants and flowers. The ideology of an Amarna house had been planned out on series of vertical and horizontal axis, resembling much of the methodologies used to plan more contemporary cities, and adorned with elements of nature derived from the surrounding environment

figure 3 House (reconstruction), Amarna

18

Fundamentally, the architectural ideas of Pharaonic placemaking in the case of Amara strongly appear to be most consistent with the geographical location and the socio-economic hierarchy of the urban life. Placemaking had been planned accordingly to become one with the existing fabric, and in essence allow ancient Egyptians to move along an axis that provided grandeur pathways to cherished spaces with architectural incidents like gateways whilst providing a rhythm and signalling changes in spatial significance to emphasize places that were of vital importance to the people (Fazio, Moffett and Wodehouse, 2008). These ideas have been planned around factors such as orientation, sequential movement, and articulation – and thereof complimenting the living tradition of ancient Egyptians and allowing direct pursuit of their activities and order within their social fabric.

19

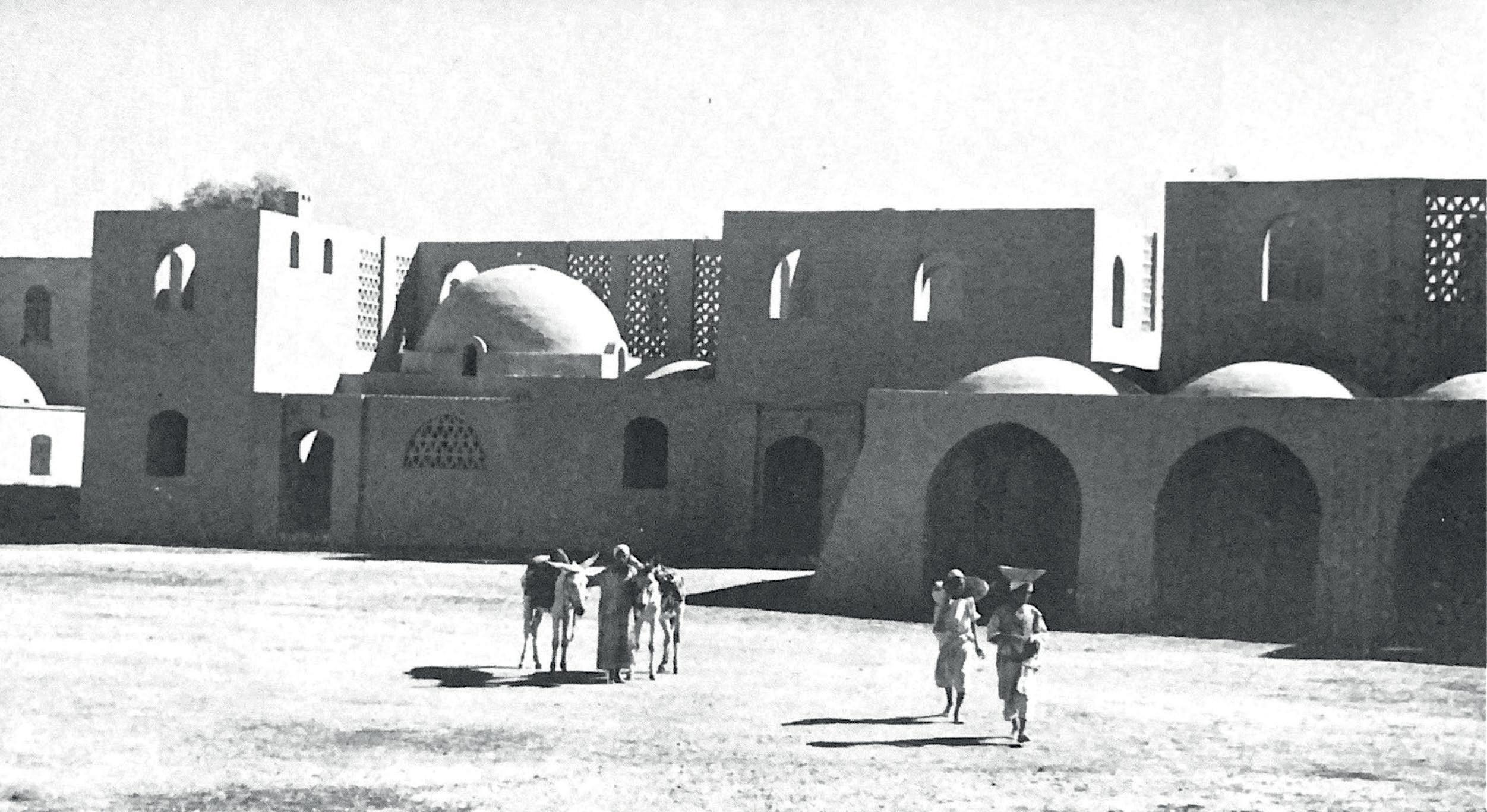

CASE STUDY: NEW GOURNA

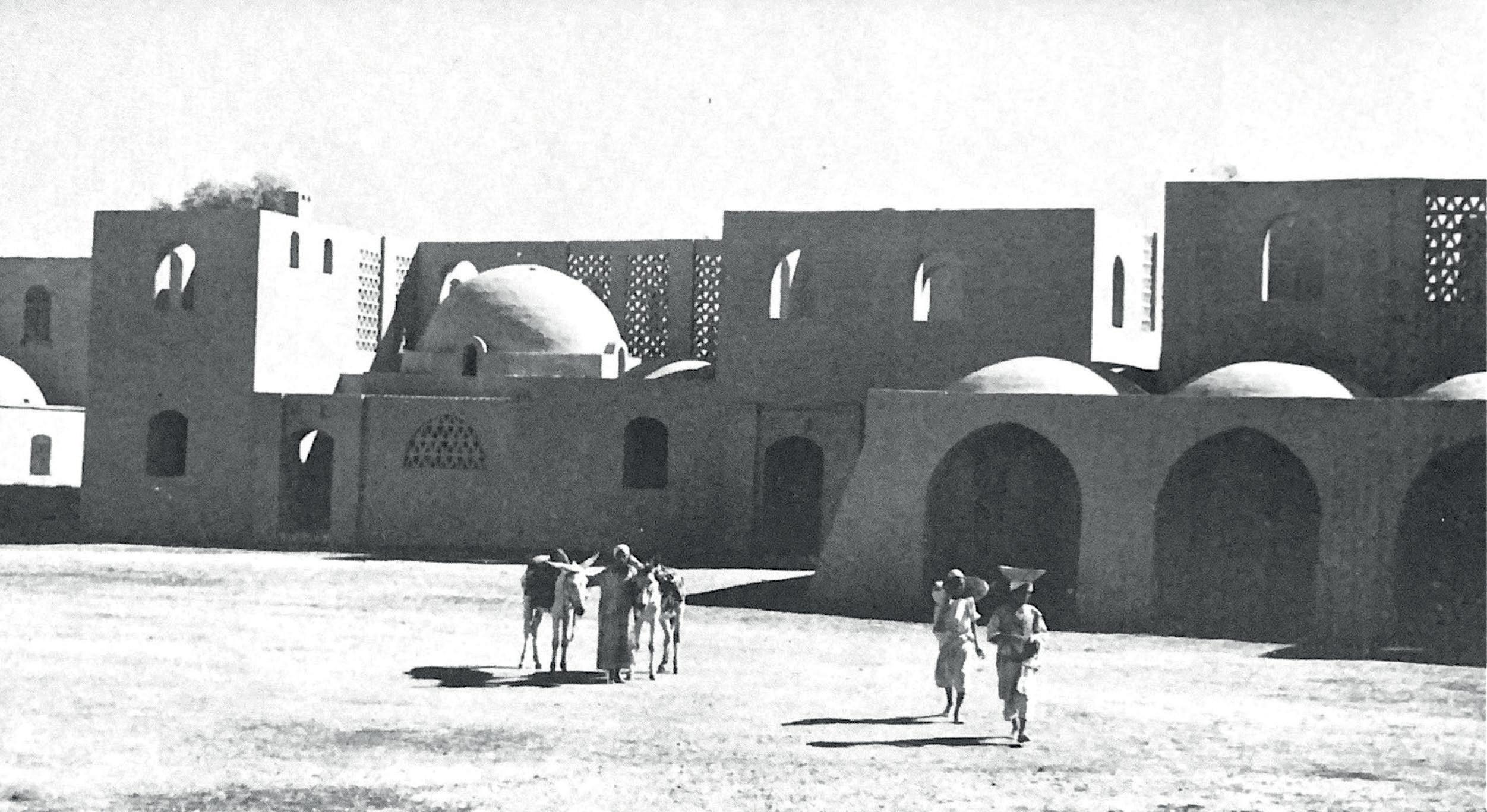

Developed in the hands of Hassan Fathy, the architect aimed to build up the village of Gourna in ways that it would not be false to Egypt. In efforts of restoring values of Arabic culture and tradition that would be available to the common villager, the objective was to produce cheap inhabitable space using local earthly material of sun-dried mud brick for the major poor. The achievement of such task would mean new domestic possibilities for 33% of Egypt’s 70 million civilians who were classified as poor, as according to the national statistics agency report released on household finances. Independent of socio-economic factors, this would allow more traditional methods of domestic construction to be applied within a contemporary Egyptian context.

The ideology of Hassan Fathy’s architecture for the poor employs traditional architectural designs of enclosed courtyards and domed and vaulted roofing using affordable material – allowing the construction to be ideal for the majority of population. As earth bricks cannot withstand bending and sheering, the vaults are formed into the shape of a parabola, thus eliminating all bending, and allowing the material to work under compression (Fathy, 1973).The result is the construction of a natural roof that uses the same locally sourced material as that of the walls, allows an architecture style that is affordable in construction to the poor locals and is inheritable to its component location and environment. The reality of placemaking within a village context thus proves to be capably cost effective and representative of the people’s connection with the wider urban fabric. Not only is it limited to that of domestic construction, but further the architect prompts that architecture that takes in account its people, can allow for the creation of economic resources for the village community and bring in small scale aspects of tradition to the existing context; and such example is portrayed through the creation and allocation of ponds in which to locals can gather to interact while they raise fish.

20

To better the case, the technique of building vaults and domes in Egypt had been evident in tombs of ancient Egyptians in the twelfth dynasty. In his book Architecture for the Poor, Hassan Fathy mentions a time in which he had seen a dome in the tomb of Seneb, in a cemetery at Giza. In this case the material of construction was mud brick too. This actively demonstrates that Pharaonic and Arabic styles may share common features and draw on one another in retrospect to the common climate they have essentially been built for and hosted in. In effect, the environment had led to a traditional method of Egyptian roofing that carried itself for decades and even centuries.

In ornamentation of the mud brick housing in New Gourna, a latticed projecting oriel window, in other words called Mashrabiya, was used to adorn housing with its capability to withstand heat of the village’s middle eastern sun. It also allowed occupants to overlook the activities of the street through the latticework, and in a sense abide with the cultural and religious need for privacy within an Arabic household.

Even though New Gourna is a testament to a functioning relation of tradition and values in the local society, the development of the village eventually came to a halt. It is argued that New Gourna failed as a model village for reasons of inappropriate use of symbolic architectural forms, poor application of an industrial supply system to inherently non-industrial craft building techniques, and the relocation of rural society villagers to more contemporary urban centres. Nevertheless, it succeeded at providing an ideal prototype for Arabic placemaking within Egyptian context. In a sense that it created a space that reformed the living culture and considered the values and needs of the local villagers. It was a natural growth in the landscape, ill of money, industry, and status; that of which sever contemporary Egyptian architecture from meaning and purpose as mentioned prior.

21

figure 4 Street in New Gourna

22

O N C L U S I O N

In retrospect to the conducted research, it is evident than many commonalities are shared between Pharaonic and Arabic styles of architecture. Attention to orientation, the environment, and most importantly the common values and tradition shared among the people, provided insight into understanding placemaking prior to contemporary Egypt. While both styles – although vividly contrasting, remain similar in sense to how they have responded to their context. Both styles have displayed depth to how they allowed space for shared culture, belief systems, and tradition.

While the Pharaonic style expressed grandeur to the gods and its source of life – the Nile – it has also reflected its belief, culture, and values within how its built form. In other words, its built form facilitated the expression of such beliefs and values. Similarly, the Arabic style, for instance, expressed beautiful sounds – of which was specifically built for. Mosque minarets sounded the call to prayer to remind its people to congregate. Beliefs, values, and culture was built for and expressed in the built form. One is therefore able to identify through such successful placemaking were such societies able to express and imprint their colourful identities and styles that remain celebrated and adored today. In essence, Egyptian placemaking as portrayed through the case studies of Amarna, and New Gourna, meant that places conformed to and were true to their function, and that mainly stemmed from knowing precisely what the function of such places was.

23

C

Today, it is unfortunate that modern Egyptian placemaking has failed to reflect its culture, beliefs, and values. Instead, the built form is erected with neglect to placemaking values in attempt to generate profit or meet demand. This is not to say that current Egyptian context contains a hollow and empty sphere of values and beliefs. This could not be more false. Rather the current Egyptian context is wealthy in societal value, culture, and belief systems. It is rather to conclude that current and past modern placemaking systems has failed to build for and adhere to its context. It may be that the function of contemporary Egypt had lost clarity on following function. Which in turn has produced an array of confusing spaces and ugly built forms with no relation to its people or place.

The thesis would therefore inform authoritative designers and planners to firmly identify the context and function of the specified place. To accordingly design and build in accordance to the values and beliefs of the people – or in other words to successfully execute placemaking in its true essence. Through such methods only will the inhabitants be able to fully self-express and truly find belonging with the built environment. An attribute which would undoubtedly bring a wave of benefits on multiple fronts.

24

Figure 1

Figure 2 Figure 3 Figure 4

Reconstruction of the House of the Prophet, Medina, ca. 622. Plan, city center, Amarna House (reconstruction), Amarna Street in New Gourna

L I S T O F F I G U R E S 25

Akkar Ercan, M., 2016. ‘Evolving’ or ‘lost’ identity of a historic public space? The tale of Gençlik Park in Ankara. Journal of Urban Design, 22(4), pp.520-543.

Augé, M., 1995. Non-places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. verso.

Behrens-Abouseif, D., 1989. Islamic Architecture in Cairo. 3rd ed. Netherlands: E. J. Brill.

Belmonte, J., Fekri, M., Abdel-Hadi, Y., Shaltout, M. and García, A., 2010. On the Orientation of Ancient Egyptian Temples: (5) Testing the Theory in Middle Egypt and Sudan. Journal for the History of Astronomy, [online] 41(1), pp.1-29. Available at: <https://www.researchgate.net/ publication/236330885_On_the_Orientation_of_Ancient_Egyptian_Temples_5_Testing_the_Theory_in_Middle_Egypt_and_Sudan> [Accessed 4 February 2021].

Curl, J., 1994. Egyptomania. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Fathy, H., 1973.Architecture for The Poor. The University of Chicago Press.

Fazio, M., Moffett, M. and Wodehouse, L., 2008. A World History of Architecture. 2nd ed. London: Laurence King Publishing Ltd, pp.20-33, 153-175.

Fugate, G., 2015. Creating an Islamic Place: Building Conversion and Sacred Space. ISVS e-journal, [online] 4(1). Available at: <http://isvshome.com/pdf/ISVS_4-1/ISVS%20 Vol4issue1paper1.pdf> [Accessed 8 February 2021].

Gates, C., 2003. Ancient Cities. New York: Routledge, pp.78-119.

I S T O F R E F E R

26

L

E N C E S

Jashari-Kajtazi,T. and Jakupi,A., 2017. Interpretation of architectural identity through landmark architecture: The case of Prishtina, Kosovo from the 1970s to the 1980s. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 6(4), pp.480-486.

Lynch, K., 1960.The Image Of The City. Massachusetts:The Joint Center for Urban Studies. Montgomery, C., 2013. Happy City.Toronto: Doubleday Canada.

Murray, M., 2009. Egyptian Temples. 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

Rabbat, N., n.d. What is Islamic architecture anyway?. [ebook] Available at: <https://arthistoriography.files.wordpress.com/2012/05/rabbat1.pdf> [Accessed 4 January 2021].

Rapoport, A. (1969) House Form and Culture. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Salama, A., 2007. Mediterranean Visual Messages: The Conundrum of Identity, ISMS, and Meaning in Contemporary Egyptian Architecture. International Journal of Architectural Research, 1(1), pp.86-104.

Stevens, A. (2016) Tell-El Amarna [online]. UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. 1 (1), . [Accessed 12 July 2021].

2019. Understanding Poverty And Inequality In Egypt. [ebook] World Bank Group.

27

28