OF SCIENCE

WELLBEING & SUSTAINABLE BUILDINGS DISSERTATION BENV0008 VXGC7 UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON

THE IMPACT OF FACADE DESIGN ON PEDESTRIAN HEALTH & WELLBEING A LONDON BASED STUDY MASTERS

HEALTH,

DECLARATION

I declare that this dissertation is my own work and that all sources have been acknowledged.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I give my warmest thanks and gratitude to Nici Zimmermann - my supervisor, whose guidance, teachings, and advice have carried me through the writing of this work.

To all of, Helen Pineo, Gemma Moore, Marcella Ucci, Jean Hewitt, Anna Mavrogianni, Gesche Huebner, and Stephen Cannon-Brookes - Thank you. For broadening my knowledge within the field. You have developed the academic skillset that has made this piece of work possible.

Peers & friends, your brilliant minds have given me the opportunity to learn matters beyond the scope of the academic year. I express my sincerest appreciation to Yasmeen, for sustaining me through difficulties and being an exemplar of determination by far.

My family - your unprecedented wisdom & support have given me the strength the fulfil my passions with great courage, time and time again. Ashraf, Eman, Dania, Nadine, Ahmed, and Mohamed, you are the guiding light of all my endeavours. For you, I am thankful.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

i

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022 ii

With change as a constant variable in the age of architecture, the built environment has simulated a series of façade design styles that can be seen as a product of combining art, science, and new technologies. What arises within this, is that often newly designed buildings, their aesthetics, form, colour, materials, and architectural solid, lead to issues such as visual or thermal discomfort, distaste, confusion, or anxiety. While it is recognised that over 90% of public transport journeys in cities include at least two walking trips, from which travellers spend 45–50% of their travel time as pedestrians, the impact of façade design on pedestrian health and wellbeing has received limited attention from scholars and practitioners. In effect, this study explores the impact of façade design on pedestrians’ health and wellbeing through the appraisal of affect in relevance to four London based case studies. The methodologies carried out expand on conducting pedestrian questionnaires in proximity to the buildings while observing urban activities, monitoring temperature, light, and sound levels, and quantifying features of the urban environment. A façade design configuration system established in support of this study further accounts the components and characteristics of façade design into a descriptive ID that effectively serves as a tool for the comparison of cases. In result, pedestrian reported affective feelings of admiration, curiosity, and visual comfort because of the façade design elements of detailing, form, and use of materials. The study therefore provides evidence that urban walking serves psychological and physiological benefits, and further raises the investigation of the subject matter in future research to better understand how built facets can benefit individuals on multiple fronts.

Key words: Pedestrian, Façade, Building, Urban, Walking, Health, Wellbeing, Affect, Stimulation

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

ABSTRACT

iii

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022 iv Facade Design & Pedestrians in the Built Environment...........................................................................01 Aims & Objectives of the Study..................................................................................................................02 Scope of the Study.......................................................................................................................................02 CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 2.0 LITERATURE REVIEW 1.1 1.2 1.3 Literature Review Methods........................................................................................................................03 Health and Wellbeing in the Built Environment........................................................................................04 The Pedestrian Experience.........................................................................................................................05 Summary of the Literature.........................................................................................................................08 Existing Knowledge Gaps and Areas Requiring Further Research..........................................................10 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 3.0 METHODOLOGY p. 01 Study Design................................................................................................................... ............................11 Data Collection................................................................................................................ ..........................14 Data Analysis...............................................................................................................................................18 Facade Design Configuration System............................................................................................. ............18 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 2.1.1 2.1.2 Research Question and Search Criteria........................................................................................03 Database Search and Screening Process........................................................................................03 3.1.1 3.1.2 3.1.3 Approach and Strategy....................................................................................................................11 Case Study Selection.......................................................................................................................12 Case Study Approach.......................................................................................................................14 3.2.1 3.2.2 3.2.3 3.2.4 3.2.5 3.2.6 Practice Member Interviews...........................................................................................................14 Pedestrian Experience Questionnaires..........................................................................................15 Pedestrian Observation...................................................................................................................15 Ethical Considerations.....................................................................................................................15 Urban Environment Mapping & Observation.................................................................................16 Urban Environment Monitoring......................................................................................................17 3.2.2.2 3.2.2.2 General Pedestrian Questionnaire...................................................................................15 Case Study Pedestrian Questionnaire.............................................................................15 3.3.1 3.3.2 The Urban Environment..................................................................................................................18 The Pedestrian Experience.............................................................................................................18 3.4.1 3.4.2 The Why and How..........................................................................................................................18 Facade Design Configuration Tables...............................................................................................18 p. 11 p. 03

8.0 APPENDIX

Literature Review Search Criterion.............................................................................................................46 Interview with Practice Members - Details of Interview and Questions.................................................46 General Pedestrian Questionnaire...............................................................................................................47 Case Study Pedestrian Questionnaire.........................................................................................................48 Interviewee Information Document.............................................................................................................49 Interviewee Consent Form..........................................................................................................................52 Facade Design Configuration System............................................................................................. ..............54 Environment matrix adopted from Hillnhütter (2021) with condition scoring relevant to the surrounding environment of Montcalm East..............................................................................................57 Environment matrix adopted from Hillnhütter (2021) with condition scoring relevant to the surrounding environment of the Blavatnik building....................................................................................57 Environment matrix adopted from Hillnhütter (2021) with condition scoring relevant to the surrounding environment of the Rubens hotel...........................................................................................58 Environment matrix adopted from Hillnhütter (2021) with condition scoring relevant to the surrounding environment of the Viacom building.......................................................................................58

Facade design configuration of the Montcalm East hotel......................................................................... ..59 Facade design configuration of the Blavatnik building................................................................................62 Facade design configuration of the Blavatnik building................................................................................65 Facade design configuration of the Viacom building...................................................................................68 MSC IEDE Dissertation Ethics Declaration.................................................................................................71 Low Risk Application....................................................................................................................................72 Application For Ethical Review (Low Risk)................................................................................................73

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022 v

17 18

7.0

6.0 CONCLUSION

5.0

The Impact of the Reviewed Case Studies on Pedestrians’ Health and Wellbeing......... .......... .............36 Limitations within the Study.......................................................... .......37 Recommendations for Future Research....................................................................................................38 Implications for Policy and Practice...........................................................................................................39 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 4.0 RESULTS & ANALYSIS The Current Case......................................................................................................................................19 The Impact of: Montcalm East, the Blavatnik, the Rubens, and the Viacom on Pedestrians..................22 4.1 4.2 4.1.1 4.1.2 What is, and What is Not, an Issue................................................................................................19 What the Current Case Means.......................................................................................................21 4.2.1 4.2.2 4.2.3 The Urban Environment(s)..............................................................................................................22 The Building(s) & their Facade Design.......................................................................................... .27 The Pedestrian Experience.............................................................................................................28

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

p. 46

REFERENCES p. 42

p. 40

DISCUSSION p.36

p.19

LIST OF FIGURES

1.1 2.1 2.2 2.3 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9

Scope of the study.......................................................................................................................................02

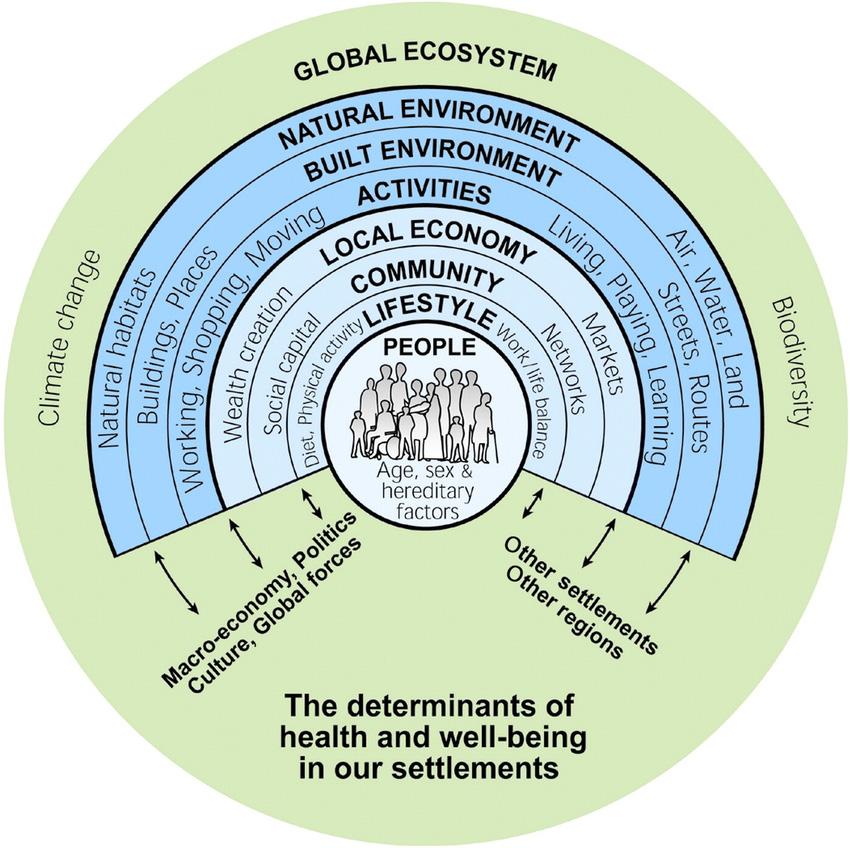

The Health Map - Barton and Grant (2006).............................................................................................05 Nasar’s (1994) probabilistic model of aesthetic response.......................................................................06 Causal chain model of drivers, source of interaction, exposures, indicators, and outcomes of a pedestrian’s encounter of a building facade..............................................................................................09

Summary of study methods........................................................................................................................12

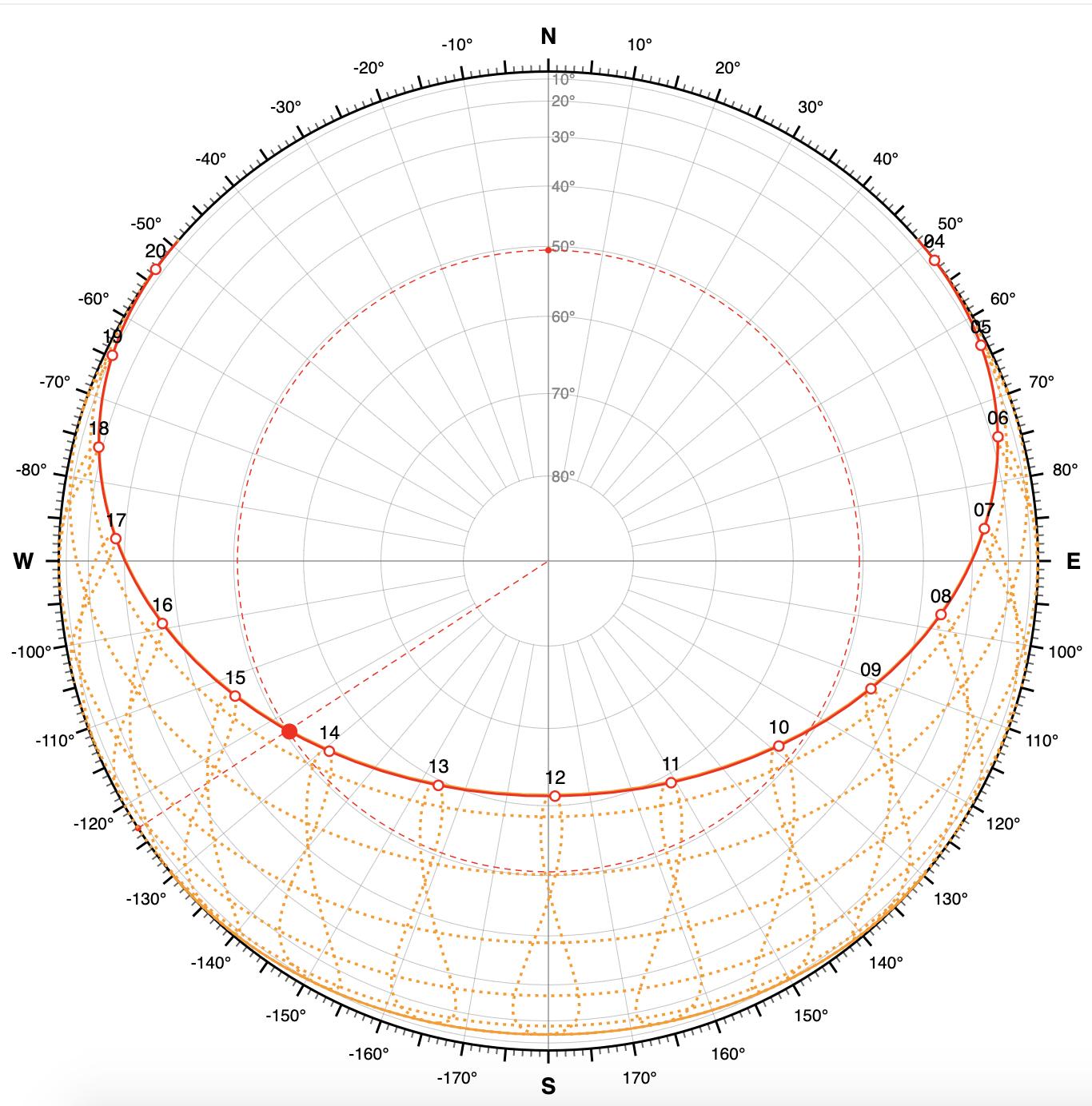

2D sun path diagram of London during the month of July - retrieved from Marsh (2014)..................14 Hillnhütter’s (2021) environment matrix, describing four conditions for seven features of walking environments..............................................................................................................................................16

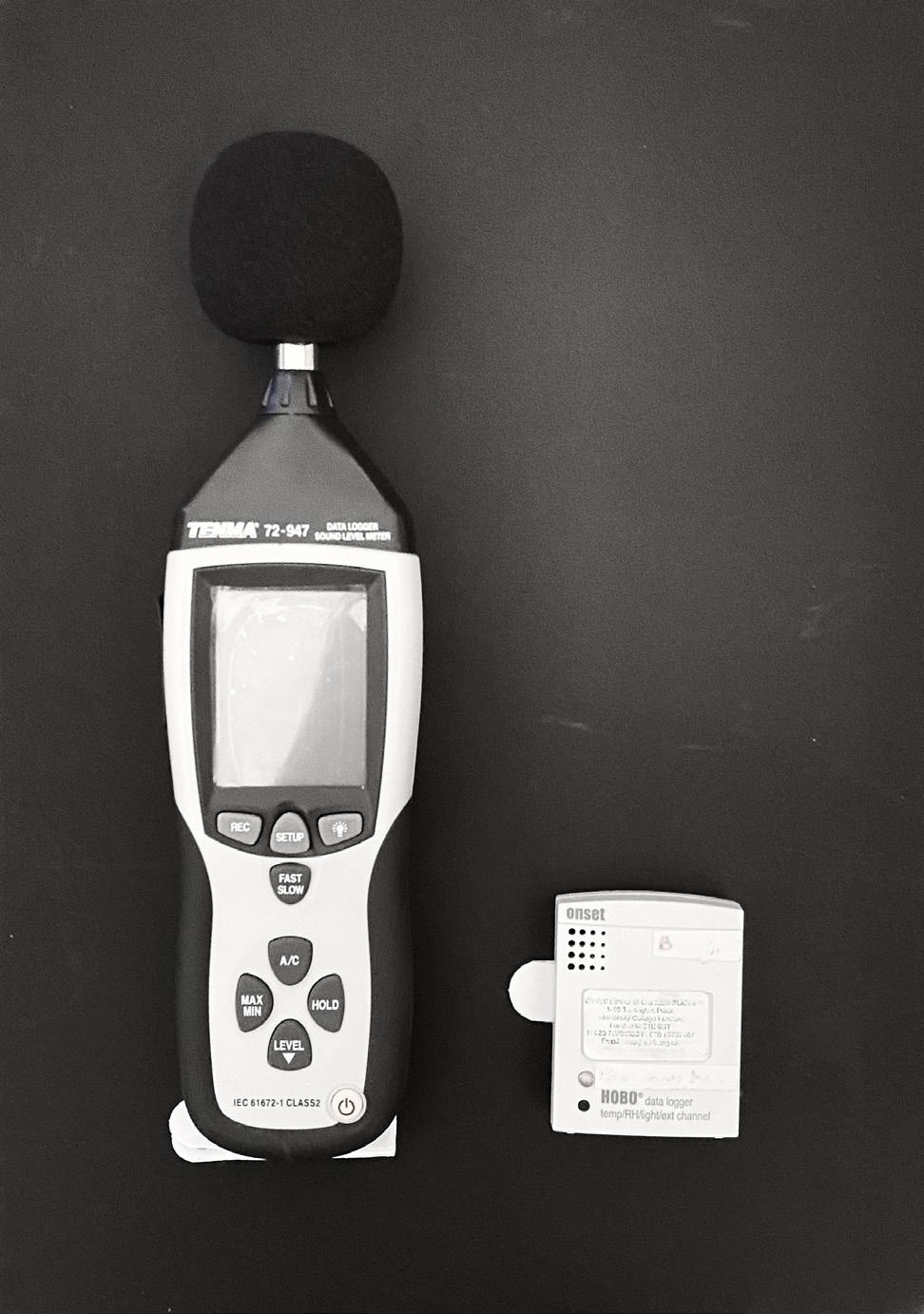

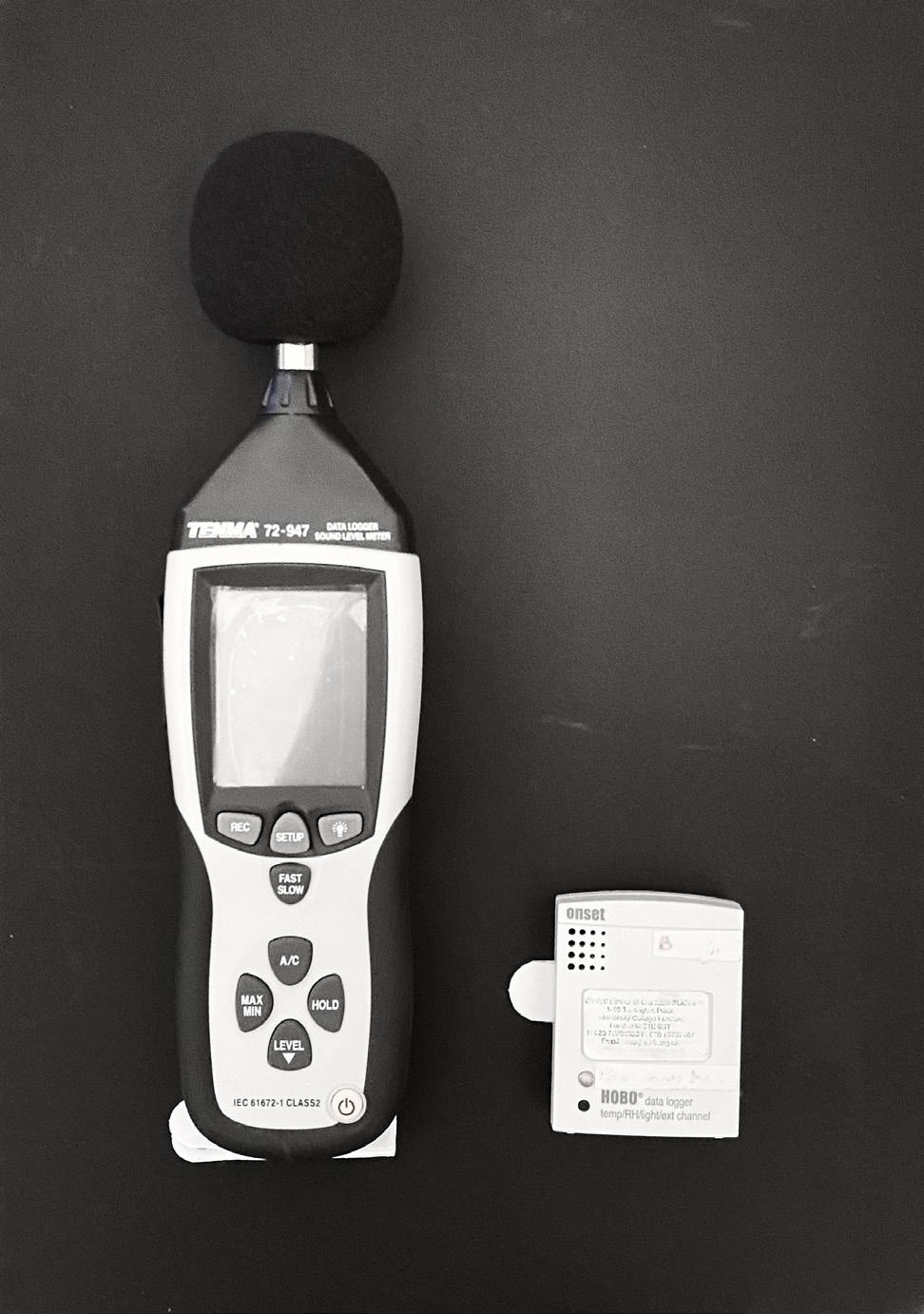

Environmental monitoring equiptment used - HOBO data logger & Tenma 72-947 sound level meter...........................................................................................................................................................17

Environmental monitoring equiptment set-up..........................................................................................17

Pedestrians that had experienced a building facade that positively or negatively impacted their mental or physical state against those who did not................................................................................19 Selected aspects of facade design that elevated pedestrians’ mental / physical state in past encounters..................................................................................................................... .............................20

Selected aspects of facade design that deterred from pedestrians’ mental / physical state in past encounters..................................................................................................................... .............................20

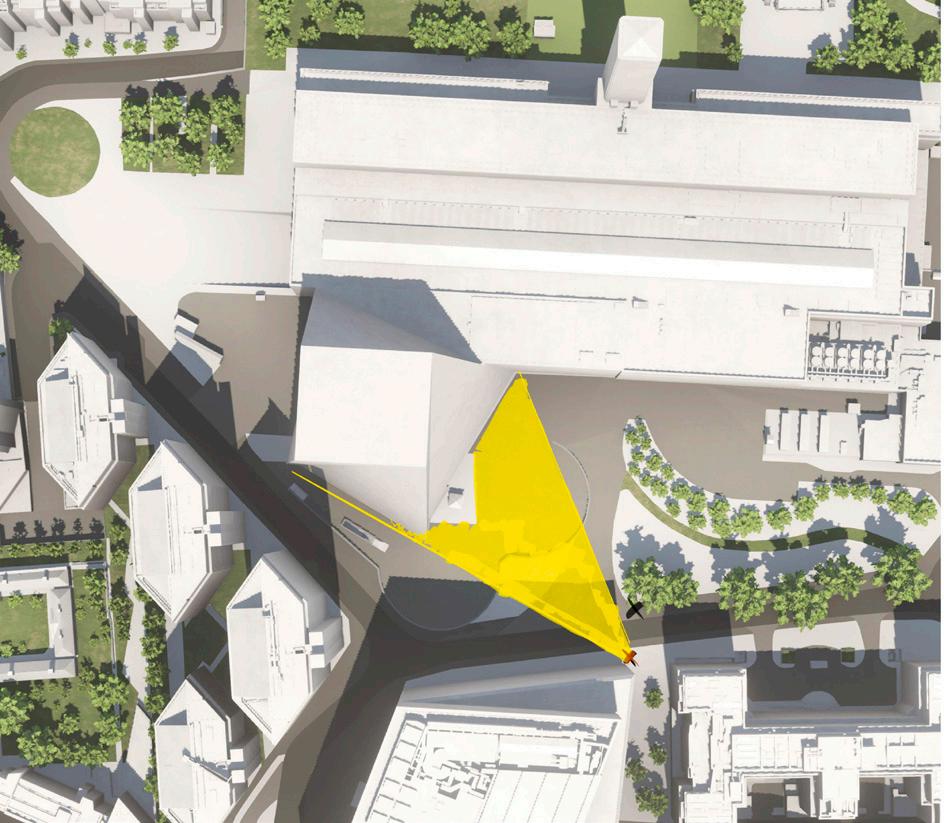

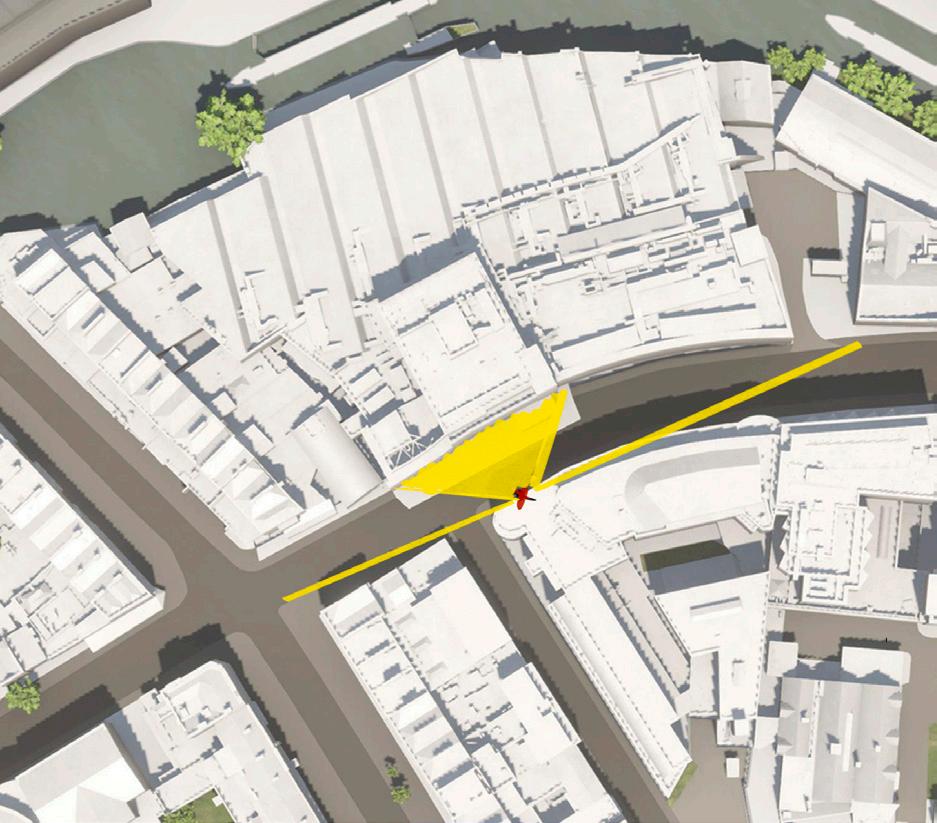

Map of each case study with location of field work set-up and area of which questionnaires were conducted....................................................................................................................................................23

Results regarding the environment matrix adopted from Hillnhütter (2021) with condition scoring of seven environmental features within the surrounding environment of Montcalm East, the Blavatnik building, the Rubens hotel, and the Viacom building................................................................................24

Pedestrians’ perception of Montcalm East’s, Blavatnik’s, Rubens’, and Viacom’s urban environment...26

Pedestrians’ perception of Montcalm East’s, Blavatnik’s, Rubens’, and Viacom’s exterior building design...........................................................................................................................................................27

Positive feelings experienced by pedestrians when encountering the facade design of the Montcalm East, the Blavatnik, the Rubens, and the Viacom.......................................................................................30

Negative feelings experienced by pedestrians when encountering the facade design of the Montcalm East, the Blavatnik, the Rubens, and the Viacom.......................................................................................31

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022 vi

F I G U R E S

LIST OF TABLES

3.1 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5

TABLES

The four selected case studies, their location, and reason for selection...............................................13

General and time-stamped observations of the surrounding environment to that of Montcalm East, the Blavatnik building, the Rubens hotel, and the Viacom building..........................................................25 Minimum, maximum, and average values of temperature, light, and sound levels of Montcalm East’s, the Blavatnik’s, the Rubens’, and the Viacom’s background environment...............................................26 Facade design configuration IDs of the Montcalm East hotel, the Blavatnik building, the Rubens hotel, and the Viacom building..............................................................................................................................28 General and time-stamped observations of pedestrians in reference to Montcalm East, the Blavatnik building, the Rubens hotel, and the Viacom building................................................................................28

Heat table illustrating pedestrians’ experienced positive feelings as a result of facade characteristics of the Montcalm East........................................................................................................... ......................32

Heat table illustrating pedestrians’ experienced positive feelings as a result of facade characteristics of the Blavatnik building.............................................................................................................................32

Heat table illustrating pedestrians’ experienced positive feelings as a result of facade characteristics of the Rubens.................................................................................................................. ............................33

Heat table illustrating pedestrians’ experienced positive feelings as a result of facade characteristics of the Viacom..............................................................................................................................................33

Heat table illustrating pedestrians’ experienced negative feelings as a result of facade characteristics of the Montcalm East........................................................................................................... ......................34

Heat table illustrating pedestrians’ experienced negative feelings as a result of facade characteristics of the Blavatnik...........................................................................................................................................34

Heat table illustrating pedestrians’ experienced negative feelings as a result of facade characteristics of the Rubens.................................................................................................................. ............................35

Heat table illustrating pedestrians’ experienced negative feelings as a result of facade characteristics of the Viacom..............................................................................................................................................35

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 4.10 4.11 4.12

vii

1.0 INTRODUCTION

1.1 FACADE DESIGN IN THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

Urban spaces and architecture have developed since antiquity. This development has carried historic themes and contemporary trends as the basis for creating the modern image of a city. With change as a constant variable in the age of architecture, the built environment has simulated a series of façade design styles that can be seen as a product of past movements in union with the notion of combining art, science, and new technologies (Górka, 2019). In most cases, the functionality of indoor illumination, acoustics, or thermal comfort of the user, has created the space for designers to be creative in their approach towards the subject matter and innovative in what they design and construct of an exterior building envelope. Within this, researchers and practice professionals have extensively sought out methods in which building facades can contribute to energy savings, mitigate environmental impact, meet occupant needs, and reflect the identity and traditions of place. On the contrary, few researchers have taken into consideration how the characteristics of façade design are liable in impacting pedestrian’s health and wellbeing (Bornioli et al., 2018; Hollander and Anderson, 2020; Lindal and Hartig, 2013).

It is recognised that over 90% of public transport journeys in cities include at least two walking trips, from which travellers spend 45–50% of their travel time as pedestrians (Hillnhütter, 2016). Within this, several health and wellbeing benefits can be expected due to improved environmental qualities and the increase of walking activity (Jeong et al., 2018). What arises within the contemporary innovation of façade design, is that often newly designed buildings, their aesthetics, form, colour, materials, and architectural solid, lead to issues such as visual or thermal discomfort, distaste, confusion, or anxiety (Bornioli et al., 2018; Hollander and Anderson, 2020; Ishak et al., 2021). To neglect the conception of pedestrian health and wellbeing as an added function of the building façade would mean to deny individuals the right to a healthy and giving city.

While a façade should verily continue to testify to the quality of solutions and functionality of an overall building design, there yet remains a need to understand what type of building façade characteristics cause pedestrians visual disturbance, confusion, or anxiety – and in opposition what characteristics of the exterior building envelope can contribute to conducive health and wellbeing through matters of visual comfort, curiosity, and excitement. From such, can policy and practice continue to recognise its audience holistically, and in effect respond to bettering the needs of the people who make up the city.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022 01

1.2 AIMS & OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY

The aim of this study is therefore to investigate if and how building facades prompt negative or positive experiences from pedestrians through four London based case studies. These are: the Montcalm East hotel, the Blavatnik building, the Rubens hotel, and the Viacom building. Accordingly, the objectives of the study expand onto; conducting pedestrian questionnaires in proximity to the buildings to uncover potential affects, perceptions, and opinions from the pedestrian. In conjunction with, mapping the urban morphology, observing urban and pedestrian activities, monitoring environmental conditions of temperature, light, and sound levels, and quantifying the urban environment via Hillnhütter’s (2021) environment matrix – all to highlight potential influences of the urban environment on the pedestrian experience. Additionally, the study raises the objective of applying a descriptive measure onto the buildings’ façade via establishing a façade design configuration system that accounts for various components of its characteristics. From such, the buildings’ façade could be classified in simple format to highlight findings through the comparison of commonalties and differences.

1.3 SCOPE OF THE STUDY

The current study is built on the premise that through understanding the evolutionary, environmental, and psychological factors influencing individuals’ perceptions, behaviour, and preference of built facets, in conjunction with investigating the influences of urban and building features on pedestrian stimulation and affect, can the knowledge gap encompassing how façade design impacts pedestrian be addressed. Figure 1.1 presents an illustration encompassing the scope of the study.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

BUILDING & THEIR FACADE KNOWLEDGE GAP &

• Health &

• Evolutionary Psychology • Environmental Psychology • Stimulation • Perception • Affect • Form • Features • Governing Dimensions • Morphology • Features • Environmental Conditions • Activities X X X 02

INDIVIDUAL URBAN

FOCUS OF THE STUDY

Wellbeing

2.0 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 LITERATURE REVIEW METHODS

2.1.1 RESEARCH QUESTION AND SEARCH CRITERIA

In pursuit of the presented objectives, the following literature review adopts a thematic narrative approach from which it researches the variables at interplay during a pedestrian’s encounter of a building facade. The literature review was guided by the questions:

- What is the effect of urban walking environments on pedestrians

- What is the pedestrian experience – how can it be positive or negative

- How does building design impact the pedestrian experience

- What is the impact of building/façade design on pedestrian health and wellbeing

From such, the study able to better understand the relationship between the pedestrian and the urban environment –highlighting patterns that imply positive or negative pedestrian experiences from the encounter of building facades.

2.1.2 DATABASE SEARCH AND SCREENING PROCESS

A database search was conducted through the Web of Science collection. The search criterion expanded on health, wellbeing, pedestrians, façade design, affective feelings and others key words evidenced in appendix 1. All papers from the database search were screened by the title of the paper and keywords listed. No criterion was put on papers’ date of publication. Given the diverse nature of buildings in relation to other dimensions, papers which expanded on the building occupant rather than the pedestrian were excluded. In addition to that, papers which studied building performance, energy savings, interior environmental performance were excluded. A snowball approach was further adopted from the papers retrieved. A total of 16 papers were retrieved from the Web of Science collection, with 14 snowball papers retrieved. Four textbook sources were additionally used.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

03

2.2 HEALTH AND WELLBEING IN THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

To understand the terms ‘health’ and ‘wellbeing’ as constituent products of pedestrians’ encounter with building facades, it is important to first define those terms regarding the components and functional relationships from which they stem from and expand onto. Through identifying the governing dimensions prescribed in those terms, it is made clearer where façade design situates within the narrative of individual health and wellbeing, and a foundational ground for the conceptualisation of the subject matter can therefore be established.

One of the most widely adopted definitions of ‘health’ stems from the preamble of the World Health Organization constitution (1946) where the term is regarded as, ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (p.1). Although the proposed definition has long set a universal aspiration, it has been contested by researchers for the reasons that it miscommunicates the medicalisation of society, it raises disease is an unadaptable circumstance, and sets a problematic and vague criterion, as it posits a non-functional, impracticable, and impossible measure of ‘wellbeing’ (Huber et al., 2011). Alternatively, Bircher and Kuruvilla (2014) propose a new definition for health by recognising the term as a constitute of three dimensions – individual, social, and environmental determinants. The authors establish that health is ‘a state of wellbeing emergent from conducive interactions between individuals’ potentials, life’s demands, and social and environmental determinants’ (p.368). This outlook, which they frame as the ‘Meikirch Model of Health’, acknowledges an individual’s biologically given and personally acquired potential in meeting the demands of life; from such, the authors reinstate the case where health varies depending on the individual’s personal capacity, circumstance, and available resources in facilitating satisfactory life conditions (Bircher and Hahn, 2016). Here, health is expressed as an emergent product of interacting dimensions within a wider, complex system. It is created by ongoing interactions between individual, social, and environmental determinants and is not produced exclusively by a sole driver.

Similar in its definitive nature to that of ‘health’; the term ‘wellbeing’ significantly overlaps with the characteristics that support the former term. It is recognised that while the two states are interdependent, they are not interchangeable (Pineo, 2022). By reason, ‘wellbeing’ continues to be considered a ‘complex and multi-faced’ concept (Pollard and Lee, 2003, p.60). While attempts to define and measure wellbeing have long eluded researchers, Dodge et al., (2012) propose an interpretation that voices simplicity, universal application, optimism, and basis for measurement. The authors recognise that: ‘wellbeing is when individuals have the psychological, social and physical resources they need to meet a particular psychological, social and/or physical challenge’ (p.230). This reinforms Bircher and Kuruvilla’s (2014) perspective on an individual’s varying ‘potential’ in meeting the ‘demands’ of life, and further builds on wellbeing research by Beddington et al. (2008) on people’s ‘ability’ to develop their potential, work productively and creatively, build strong and positive relationships with others, and contribute to their community’ (p.1057).

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

04

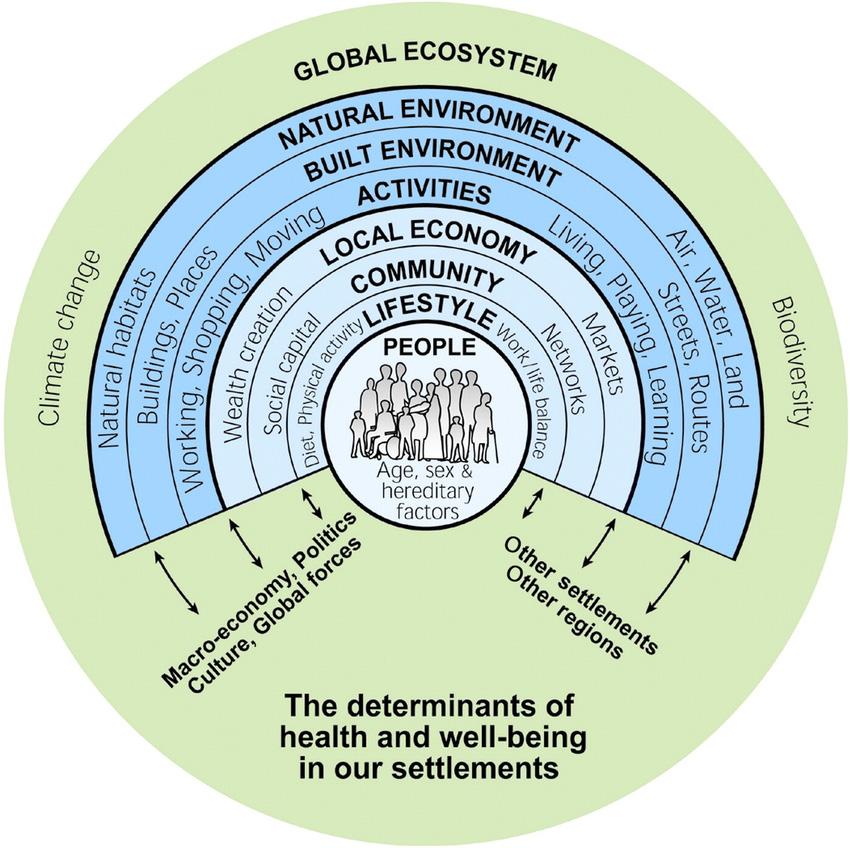

To put this in context of the built environment, Barton and Grant (2006) conceptualise the complexities and interrelationships of health and wellbeing in urban developments through a framework which they model as ‘The Health Map’ (presented in figure 2.1). The researchers depict health and wellbeing determinants at multiple scales of interacting factors, and this is reflected through a series of spheres moving through social, economic, and environmental variables. However, the placement of people at the centre often miscommunicates a perceived emphasis on individual and lifestyle factors as the stronger determinant – driving the false idea that the responsibility of improving individual health and wellbeing lies mostly with the individual rather than that of policy decisions and urban planning (Pineo, 2020). Nevertheless, the proposed model helps identify indirect processes which are often significant in terms of health, and thus can better the understanding of relations between factors.

2.3 THE PEDESTRIAN EXPERIENCE

In order to identify how façade design impacts pedestrians’ experience with regard to their health and wellbeing, one must first ask the question; what is the pedestrian experience?

A pedestrian is a person that carries out the activity of walking outside built spheres. They are driven by their unique psychological and physical conditions, they are exposed to environmental factors throughout walking, they carry out the activity within a defined urban context and are exposed to distinctive features within that context (Hillnhütter, 2021; Soria and Talavera, 2013). A great number of scholars have produced substantial research on influences of the urban environment on the experience of walking (Gatrell, 2013; Gehl and Koch, 2011), but the role of building facades as a component of the walking experience remains not well understood (Hollander and Anderson, 2020).

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

05

During the activity of walking, the five sense organs establish a link between the individual’s brain and the surrounding reality – constantly transferring a flow of environmental information (Hillnhütter, 2021). On the receiving end of the individual, psychology occupies a key role in the perception, response, and preference of environments. Chatterjee (2014) explains that people’s regard of landscapes and places expands on biological encoded processes that have developed over the course of human evolution. Places that had best provided means of safety and sustenance to the human lineage had indicated survival and nourishment and expanded beyond that to encompass the quality of communicating information quickly and giving a rich sense of place (Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989). On the contrary, Nasar (1994) proposes that an individual’s perception of place and in particular buildings, strays away from evolutionary processes to encompass more substantially, the observer’s personality, affective state, intentions, cultural experiences, and cognition. The author sets up a framework - presented in figure 2.2, to portray aesthetic response through a non-evolutionary view. From Nasar’s perspective, aesthetic response expands on affect, physiological response, and behaviour – which significantly builds on concepts revised in environmental psychology.

(Personality, affective state, intentions, cultural experiences) of building attributes (Judgments of building attributes) (Emotional Reactions) (Affect, physiological response, and behavior)

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

A 1 A 2 A 3 • • •

a

OBSERVER PERCEPTION COGNITION AFFECT AFFECTIVE APPRAISALS and connotative meanings AESTHETIC RESPONSE BUILDING ATTRIBUTES

A

06

Environmental psychologists have long directed their focus within the field towards how the environment affects human behaviour and vice versa. Lewin et al., (1936) observed that behaviour is not only a function of the individual, but it is also a function of the physical environment. In their studies, they found that an individual can have different responses to the same physical environment at different times, and that different people will perceive the same environment differently regardless of how similarly they encounter it. Expanding on Lewin et al.’s research, Barker (1968) found that while people will perceive the same environment differently, a pre-conceived social etiquette associated with the setting will unconsciously influence people’s behaviour in that setting. A curious question emerging from this discussion is whether this principle applies to broader urban settings – where for instance, pedestrians in a fast paced, business-oriented environment are less likely to enjoy and indulge in their surroundings compared to an environment that caters for leisure and interaction, even in scenarios where the former might represent more meaningful and fruitful architecture. This dilemma further instates the need to investigate the subject matter in real life scenarios compared to artificial settings as it is evidenced that individual perception, response, and behaviour are affected by more than merely physical stimulus.

Independent of psychological factors, urban researchers study the pedestrian experience in varying urban environments. For instance, Hillnhütter (2016) studied pedestrian step frequencies in (1) exciting, (2) relaxing, (3) boring, and (4) stressing urban environments. He found significantly higher step frequencies between boring and stressing environments, compared to exciting and relaxing environments. Gehl et al. (2006) studied building encounters –they found that pedestrian traffic was 13% slower along varied, open, interesting facades compared to monotone, uninteresting, closed ones, and further observed ground-floor facades to have a far greater emotional impact on pedestrians than that compared to the rest of the building or street, as details become more visible and attract eyes when closer and are responding to the human scale (Hillnhütter, 2021; Sussman and Hollander, 2021). Franek et al. (2018) experimented the effects of acoustics on pedestrians’ walking speed. He found that participants listening to traffic noise walked significantly faster than participants listening to forest birdsong sounds and those in a control condition – with those listening to forest birdsong enjoying their walking route much more than those listening to traffic. Accordingly, Sussman and Hollander (2021) proclaim that characteristics of a streetscape explain why people are drawn to certain places over others – and that this majorly depends on aspects of edges, patterns, shapes, and narrative. Supporting this proclamation, Ewing et al. (2016) measured twenty streetscape features and other variables for 588 blocks in New York City. The authors found positive correlations between proportion of windows on the street, the proportion of active street frontage, and the number of pieces of street furniture to pedestrian traffic volume.

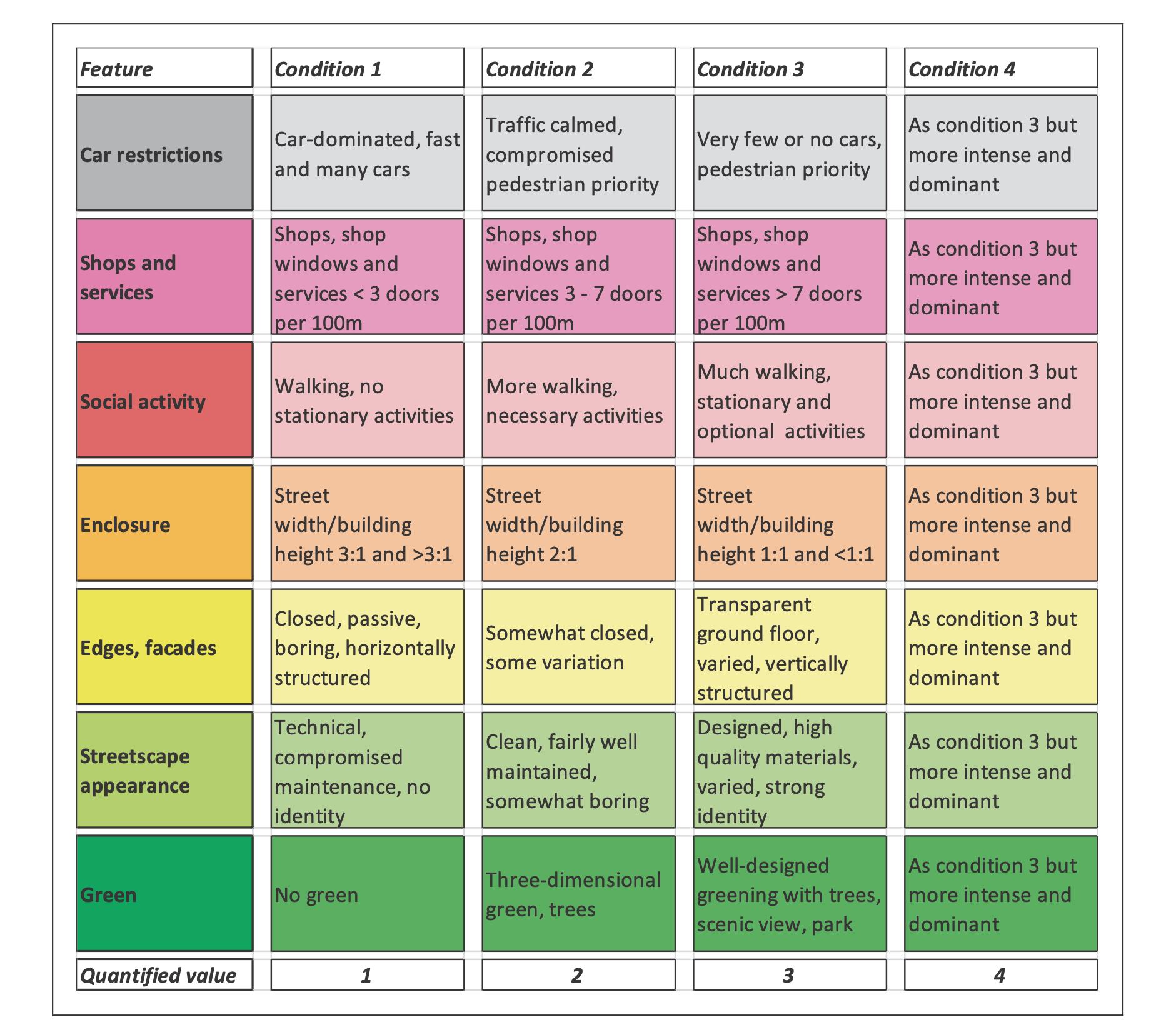

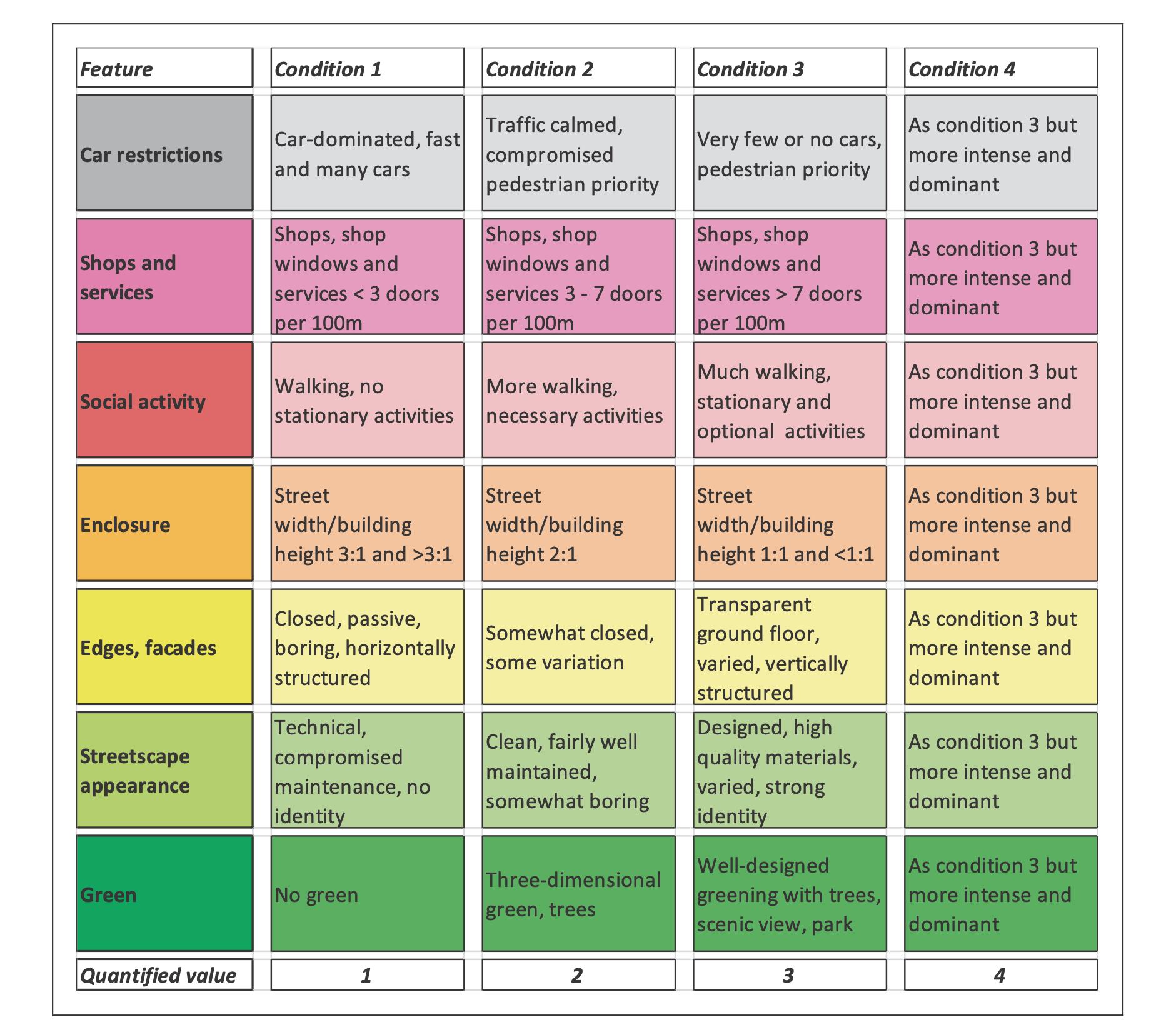

Building on Whyte’s (1980) perspective that initial observations serve to define behavioural patterns for a more focused investigation, and Gibson’s (1950) research on how humans collect visual information through eye and head movements, Hillnhütter (2021) analysed the effect of seven environmental characteristics on head movements to support the assumption that urban environments affect the amount of visual stimulus pedestrians receive from their surroundings, and hence provide an indicator of the quality of an environmental experience. He developed an environment matrix that enabled a quantitative measure of seven environmental features and had done so through identifying four conditions of each metric and subsequently giving each one of them a quantified value. The features of the environment included: (1) car restrictions, (2) shops and services, (3) social activity, (4) enclosure, (5) edges and facades, (6) streetscape appearance, and (7) green features. Hillnhütter found that the inclusion of shop windows, picturesque facades, as well as social and mobile activities in an urban setting, attracted pedestrians’ eyes and led to frequent head movements, and that head movements increased by 71% and looking down decreased by 54% in socially active urban squares and pedestrian streets compared to that of car-oriented environments.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

07

From such, it is seen that the urban aspects complied by Hillnhütter and researched alike by other scholars, do not only shape the pedestrian experience but also support the notion that non-natural environments can encourage and promote pedestrian stimulation, walkability, sociability, and satisfaction. On the contrary, there remains a vagueness is discourse encompassing the characteristics of the aspects raised, particularly those regarding buildings and more closely, building facades. Nevertheless, what these findings present is that independent of subjective and autonomic measures - head movements, step frequencies, the time spent looking down at the pavement, performed activities, and pedestrian volume, serve as indicators of the pedestrian experience and in turn, highlight what arises of health and wellbeing determinants when encountering building facades.

Moreover, the benefits of urban spheres that cater for a positive pedestrian experience are not only inducive of stimulation, walkability, sociability, and satisfaction, but are further associated with therapeutic engagements and positive affective appraisals. In a study investigating the psychological wellbeing benefits of place engagement during walking in urban environments, Bornioli et al. (2018) revealed that urban walking can be perceived as restorative as it elicited relaxation and stimulated positive affect, cognitive perceptions, engagement as well as stress recovery. The authors further observed that social liveliness within pedestrian encounters contributed to positive affective appraisals such as hedonic tone and the benefits of curiosity. Similarly, Zhao et al. (2019) explored the relationship between restorative quality and streetscape characteristics. They found that a high rate and diverse species of plants implied a high restorative capacity among pedestrians – supporting the impact of natural features in relieving stress (Beil and Hanes, 2013). In addition, Lindal and Hartig (2013) found that entropy and a sense of enclosure within architectural scenes resulted to feelings of restoration, and that the effect of building height on restoration likelihood was negative.

2.4 SUMMARY OF THE LITERATURE

What the previous sections of the literature review establish are five key points. First, health and wellbeing encompass numerous components and expand onto various functional relationships. Second, behind the perception, response, and preference of environments are drivers that expand on evolutionary and environmental psychology. Third, pedestrian behaviour and subjective response serve as indicators of the pedestrian experience. Fourth, integral features of an urban environment determine walkability, sociability, pedestrian stimulation, and satisfaction. Fifth, urban walking holds capacity in promoting therapeutic engagements and positive affective appraisals. In its efforts to conceptualise these findings, figure 2.3 presents a causal chain model of drivers, sources of interaction, exposures, indicators, and outcomes of a pedestrian’s encounter of a building façade while highlighting existing knowledge gaps.

Within this, the model communicates the various contributions that emerge from the individual as a pedestrian and the built environment as a basis of exposure, relative to façade design. It provides a more contextual understanding of the factors that come into play, and in effect establishes a foundational ground for the investigation of constituents and their role on health and wellbeing. This moreover presses how a systems thinking approach may aid in understanding, assessing, implementing, and managing healthy and sustainable facades for pedestrians.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

08

SITUATIONAL FACTORS

• Personality

• Affective State

• Intentions

• Cultural Experiences

EVOLUTIONARY PSYCHOLOGY

WALKING

• Sight • Touch • Hearing • Smell • Taste

ENVIRONMENTAL

• Air Quality

• Temperature

• Sound

• UV Radiation

INDICATORS

BEHAVIOUR

• Head Movements

• Step Frequencies • Time looking down at Pavement • Performed Activities

POSITIVE

• Excitement

• Curiosity • Admiration

• Visual Comfort

• Thermal Comfort

ENVIRONMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY

REFS.

SUPPORTING

DRIVERS

EXPOSURES

INDICATORS

OUTCOMES

• Car Restrictions

• Shops & Services

• Social Activity

• Enclosure

• Edges, Facades

• Steetscape Appearance • Green

URBAN BUILDING

• Glare • Reflection • Pattern • Overshadow • Colour • Scale • Use of Materials • Form • Detailing

RESPONSE

• Perception • Stimulation • Satisfaction • Affect • Affective Appraisals • Aesthetic Appeal • Theraputic Engagements

NEGATIVE

• Anxiety

• Confusion

• Distaste

• Visual Discomfort

• Thermal Discomfort

Brielmann et al., 2022; Chatterjee, 2014; Inavonna et al., 2018; Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989; Lau and Choi, 2021; Lewin et al., 1936; Read, 2015; Nasar, 1994

INTERACTION Gehl et al., 2006; Gibson, 1950; Hillnhütter, 2021; Soria and Talavera, 2013; Zakaria and Ujang, 2015

Browning et al., 2014; Ewing et al. 2016; Gjerde and Vale, 2022; Hillnhütter, 2021; Hollander and Anderson, 2020; Ishak et al., 2021; Kellert et al., 2008; Sadeghifar et al., 2018; Schiler, 2009; Sussman and Hollander, 2021

Franek et al. 2018; Gehl et al., 2006; Hillnhütter 2016; Hillnhütter, 2021

Bornioli et al. 2018; Hollander and Anderson, 2020; Ishak et al., 2021; Lindal and Hartig 2013; Zhao et al. 2019

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

DRIVERS INTERACTION EXPOSURES OUTCOMES

EXISTING KNOWLEDGE GAP 09

2.5 EXISTING KNOWLEDGE GAPS AND AREAS REQUIRING FURTHER RESEARCH

The current situation recognises exposures that occur when pedestrians encounter buildings – where they are mainly environmental and urban, there yet remains a knowledge gap on how characteristics of a building and its facade contribute to the pedestrian experience and in return, impact their momentarily or long-term conditions of health and wellbeing. Evidently, the question remains – how do different characteristics of a building and its façade impact pedestrian stimulation, affect, and in turn, their health and wellbeing?

Further research should therefore explore and document the characteristics of built setting with scrutiny in support of Galea and Vlahov’s (2005) perspective on the urban context itself being an exposure of interest. A building needs to be recognised holistically through its component parts, or else where research might support a feature works well in promoting conducive health and wellbeing for pedestrians, it may be overruled by other characteristics that instead leads to a detrimental outcome.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

10

METHODOLOGY

3.1 STUDY DESIGN

3.1.1 APPROACH AND STRATEGY

With an aim to investigate the industry’s views on façade design within the built environment, the study approaches members of practice to seek their perspective on the current and future agenda of façade design. The interview formulates an understanding of matters architectural practices value and prioritise when designing a façade for a building proposal. From such, the study can identify if practices are aware and considerate of pedestrians - and in particular their health and wellbeing when undertaking projects.

As research has raised that pedestrians are prone to be affected by the environment that surrounds them (Gehl et al. 2006; Hillnhütter, 2021; Hollander and Anderson, 2020), the study approaches a general population of pedestrians in London to identify in current time, what is and what is not, indeed an issue. As façade design has long developed, this aids the study in formulating a contemporary understanding of the subject matter and hence addressing it accordingly.

As previously outlined in the aims of this study, in order to gain a deeper understanding into how building façade characteristics can prompt negative or positive pedestrian experiences, this study is built on the premise that through configuring a building façade and investigating its consequent impact on pedestrians’ feelings and opinions, one can recognise how characteristics of the exterior envelope are liable to contribute to psychological and/or physiological, enrichment or deterioration. It is for those reasons; this study establishes a façade design configuration system that categorises the visual build-up of a building’s elevation into an identifiable ID that accounts various elements within a facade as well as the form and scale it accommodates.

Adopting the façade configuration system, the pedestrian experience is investigated through four case study buildings in London that speak of contemporary and innovative façade designs. These are: the Montcalm East hotel, the Blavatnik building of Tate Modern, the Rubens hotel of Buckingham Palace, and the Viacom International Media building. Acknowledging that each of these case studies will reside within unique urban domains, the urban environment is investigated through mapping, observations, and environmental monitoring of temperature, light levels, and sound levels.

A summary of the study methods is presented in figure 3.1.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

3.0

11

DESKTOP METHODS

INTERVIEWS WITH PRACTICE MEMBERS FACADE DESIGN CONFIGURATION SYSTEM

FIELD WORK METHODS

GENERAL CASE STUDIES

URBAN METHODS

PEDESTRIAN METHODS

Mapping Environment Matrix (Hillnhütter, 2021)

Urban Environment Observation

Urban Environment Monitoring

3.1.2 CASE STUDY SELECTION

Case Study Pedestrian Questionnaire Pedestrian Observation

Within context of this study, the four selected case studies act as the basis in investigating the impact of façade design on pedestrians’ health and wellbeing – details relative to the buildings, in addition to reasoning as to why they were chosen, are presented in table 3.1.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

General Pedestrian Questionnaire in Hyde Park

Montcalm East Hotel Blavatnik Building

Rubens Hotel Viacom Building

12

MONTCAL EAST HOTEL

LOCATION WITHIN MAP

PHOTOGRAPH

REASON FOR SELECTION LOCATION

Incorporates a façade design that distorts perception - and is located in an urban canyon environment.

151-157 City Rd, London, EC1V 1JH

Presents a façade that encompasses an irregular form - liable to distort perception - landscaping incorporates pedestrian street.

Bankside, London, SE1 9TG

Presents London’s largest vertical green wall system.

39 Buckingham Palace Rd, London, SW1W 0PS

Incorporates a vertical green living wall system in an urban environment that greatly lacks greenery.

17-29 Hawley Crescent, Camden Town, London, NW1 8TT

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

BLAVATNIK BUILDING

RUBENS HOTEL

VIACOM BUILDING

13

3.1.3

CASE STUDY APPROACH

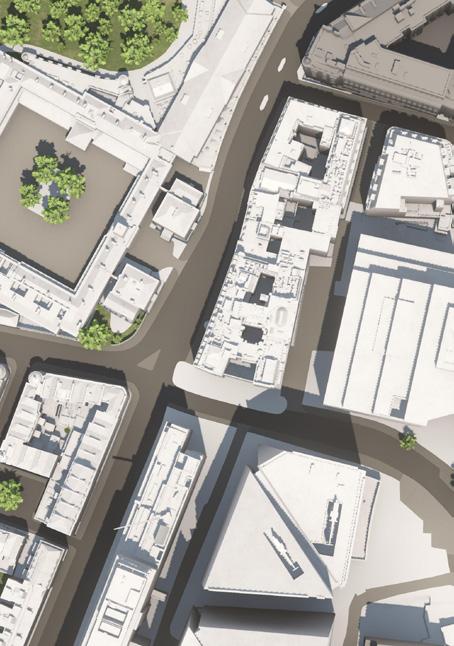

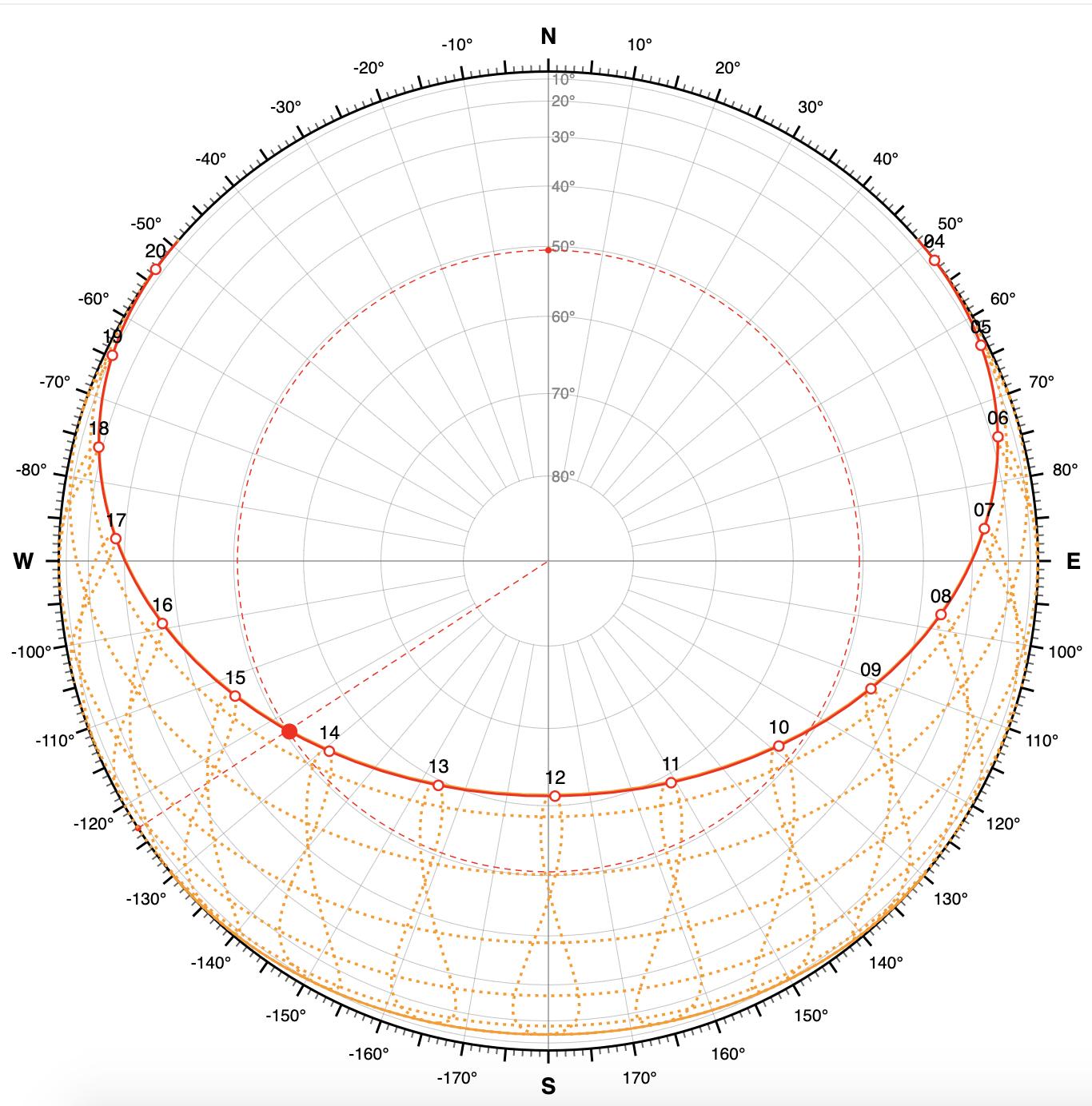

The case study field work research was carried out during a period where weather variation was liable to be at its minimal. While this is ambitious; noting that sunlight and cloud variation are dynamic qualities of the urban environment and are subject to unprecedented change within a short period of time, the study included field work when the sun is at its peak altitude. From such, the position of the sun varies slightly where it spans the most amount of time. In London, this follows the period of 10:00 to 14:00 as investigated via Andrew Marsh’s (2014) 2D sun path software as presented in figure 3.2. An extra hour had been allocated on each day in cases where more pedestrian questionnaires needed to be conducted. Consequently, field work research regarding the Montcalm East hotel, the Blavatnik building, the Rubens hotel, and the Viacom building were conducted on the 1st, 2nd, 4th, and 5th, of July respectively between the times 10:00 to 15:00.

3.2 DATA COLLECTION

3.2.1 PRACTICE MEMBERS INTERVIEWS

Three members of practice were approached via LinkedIn and invited to take part in an online interview on Microsoft Teams. The interview consisted of ten questions that expanded on the agenda of façade design within the industry. The interviews spanned a duration of approximately 30+ minutes. It was video recorded, from which audio files and transcripts were generated. See appendix 2 for interview details and questions asked.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

14

3.2.2 PEDESTRIAN EXPERIENCE QUESTIONNAIRES

The following questionnaires were conducted verbally by the author in person, and responses were documented digitally via a pre-assembled document on the iPad software Procreate.

3.2.2.1 GENERAL PEDESTRIAN QUESTIONNAIRE

Pedestrians of the public were approached in Hyde Park, London on the 25th, 26th, and 27th of July and asked about their experience of building facades as a daily encounter, in efforts to identify what indeed is and is not, an issue. The questionnaire was conducted in a park to increase the probability of interaction, fruitful conversation, as a well as to obtain responses from a spectrum of individuals. The questionnaire consisted of four pre-listed subjective and opinion orientated box-ticking questions. See appendix 3 for general pedestrian questionnaire.

3.2.2.2 CASE STUDY PEDESTRIAN QUESTIONNAIRE

25, 30, 31, and 30 pedestrians were approached within proximity of the Montcalm East hotel, the Blavatnik building, the Rubens hotel and the Viacom International building respectively and asked about their subjective experience and opinions regarding the façade design of the building in question. Prompting responses that expanded on health and wellbeing, the questionnaire consisted of box-ticking pre-listed statements for eight questions. See appendix 4 for case study pedestrian questionnaire.

3.2.3 PEDESTRIAN OBSERVATION

With evolutionary and environmental psychological tendencies rooted in the human species, the author observed pedestrians’ expressions and/or behavioural patterns, in context of the four selected case studies on the dates of 1st, 2nd, 4th, and 5th, of July conforming with the field work, to identify positive or negative façade encounters as it has been evidenced by the reviewed literature that behaviour serves as an indicator of the quality of an urban environment (Hillnhütter, 2021; Lewin et al., 1936). Observation is documented digitally through a pre-assembled document on the iPad software Procreate and during the period of 10:00 to 15:00 when the author is free from conducting questionnaires. Observation is noted through general comments and timestamped comments.

3.2.4 ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Prior to any form of data collection, interviewee participants had been informed of the study, its implications, and what participation would encompass via an information document (see appendix 5). Permission for the author to use what was discussed in the interview within this study was established by the interviewee(s) signature via a consent form (see appendix 6). The study did not seek written consent from pedestrians as they remained unidentifiable, and any personal or confidential data was not collected. The study has gathered primary data in accordance with UCL’s Data Protection Policy and ensured that legal obligations of the UK Data Protection Act 1998 (the UK legislation implementing the EU Data Protection Directive 1995) have been met.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

15

3.2.5 URBAN ENVIRONMENT MAPPING & OBSERVATION

With the urban sphere being a host of a broad range of people and services, the urban environment of the four selected case studies is observed by the author on the dates of 1st, 2nd, 4th, and 5th, of July conforming with the field work. Observation is documented digitally through two pre-assembled documents on the iPad software Procreate and during the period of 10:00 to 15:00, when the author is free from conducting questionnaires and observing pedestrians. Observation is noted in one document through general and timestamped comments, and in another through Hillnhütter’s (2021) environment matrix method of describing the features of walking environments. The matrix enables the status of seven environmental features to be scored with a condition value between one and four. See figure 3.3 for Hillnhütter’s (2021) environment matrix.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

16

3.2.6 URBAN ENVIRONMENT MONITORING

As the selected case studies bring forth four urban environments that vary from one another, the temperature, light, and sound levels of the background environment have been monitored on the dates of 1st, 2nd, 4th, and 5th, of July for each case study. From such, the study investigates if pedestrians’ responses might have been impacted by intense conditions of environmental factors.

Temperature and light levels were collected via an onset HOBO data logger with a 5-minute timestamp set to start automatically at 10:00. Sound levels were monitored via a Tenma 72-947 sound level meter and data logger, set with a 1 second timestamp starting manually at 10:00. See figure 3.4 for instruments used. While the intent of the study was to record 5 hours of the environmental factors, ending at 15:00 - both instruments needed to be manually stopped. Regarding the Tenma 72-947, this was done on-site during the end of the field work at 15:00, whereas for the HOBO device this was done off-site through the device’s software ‘HOBOware’ after the field work. Both instruments were set up on an extruded box with the dimensions: 33cm x 38cm x 66cm and were latched to the surface of the platform using a Velcro-adhesive strip for security purposes (see figure 3.5 for set-up).

The onset HOBO data logger monitored temperature and light levels for a duration of 5+ hours in each case study scenario, whereas the Tenma 72-947 had monitored sound levels for a duration of 5 hours of the first case study (the Montcalm East hotel) and 4 hours 6 minutes of the second case study (the Blavatnik building). The Tenma 72-947 had reached full capacity prior to the remaining two case studies (the Rubens hotel and the Viacom building), and hence did not record sound levels of the two cases.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

66 cm 33cm 38cm 17

3.3 DATA ANALYSIS

3.3.1 THE URBAN ENVIRONMENT

In investigating the urban environment of each case study through quantitative and qualitative assessments, the data is compared against one another to formulate the urban differences that have been of influence on the pedestrian experience. More interesting, is the role of the urban environment in shaping pedestrians’ perceptions and opinions on the case studies’ building facades, which is examined in relevance to the pedestrian questionnaire. From such, the comparison of each case studies’ building façade is established with a holistic view of the features constituting from the wider urban landscape.

3.3.2 THE PEDESTRIAN EXPERIENCE

The data analysis of the pedestrian experience utilises both quantitate and qualitative measures. As raised by the literature, the pedestrian experience serves as an indicator of the health and wellbeing outcomes derivative from the encounter of building facades. The responses retrieved from pedestrians within case study are compared against one another and evaluated with the regard to the urban environment and the characteristics of the building façade via the façade design configuration system. From such it is seen where differences have implied certain results – as the methodologies carried out within the study apply in similar manner to each of the building façade case study.

Further, the investigation of pedestrians’ subjective response of their affect, links how certain cases are of psychological or physiological elation or determent, and in turn provide areas for further research that would help better understand the impact of building facades on pedestrians’ health and wellbeing.

3.4 FACADE DESIGN CONFIGURATION SYSTEM

3.4.1 THE WHY AND HOW

In order to remove the vagueness in discourse about architectural façade designs, an objective measure of façade components needs to be applied. In context of this study, objective descriptions are that which are expressed in terms of form, scale, divisions, materials, and so on. For this reason, a façade design configuration system has been developed in support of this study.

The facade design configuration system is a system that establishes a descriptive measure of building facades and is built on the premise of categories and parameters. With recognition of the various forms, features, and dimensions a building façade can encompass, an account of design metrics has been established. Through identifying the category and parameter of each design metric, an identifiable ID of a building’s façade can be produced. The façade design configuration system further includes an urban environment classification within its output ID. The output ID is formatted as: 1:AB12345. From such, the subject matter can be recognised with its component parts but addressed holistically, and investigated against cases alike.

3.4.2 FACADE DESIGN CONFIGURATION TABLES

The façade design configuration system is formulated through tables of design metrics following urban environment, building form, façade features, and façade governing dimensions, as presented in appendix 7.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

18

RESULTS & ANALYSIS

4.1 THE CURRENT CASE

4.1.1 WHAT IS, AND WHAT IS NOT, AN ISSUE

In investigating the impact of façade design on pedestrians, one must place the pedestrian at the basis of the investigation. To imply that urban environments nonetheless building façades can influence how populations feel without the perusal of the population’s subjective or objective input, would mean deriving to conclusions that encompass several faults. In effect, a general pedestrian questionnaire investigated if individuals had ever experienced a building façade that they felt elevated or deterred from, their physical or mental state. It is worthy to note that the formulation of the question in past tense directs pedestrians to reflect on experiences that had left them with an impact or an impression. If indeed they did find themselves in such scenario, they can contemplate on how they felt and what they were exposed to, formulating a renewed recognition of their encounter of building facades. Out of the 32 pedestrians approached, figure 4.1 shows the number of individuals that did experience a building façade that they felt elevated or deterred from, their mental or physical state against those who did not.

PEDESTRIANS’ PAST EXPERIENCES OF BUILDING FACADES

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

4.0

19

In reflecting on the causes of these two scenarios, the 32 pedestrians approached were made to choose the different façade design aspects that they felt were of contributing influence. Options expanded on glare, reflection, pattern, overshadow, colour, scale, use of materials, form, detailing, ‘other’, or ‘none’. Results presenting what aspects elevated pedestrians’ mental/physical state in past encounters are presented in figure 4.2, whereas aspects that deterred from pedestrians’ mental/physical state in past encounters are presented in figure 4.3. From the portrayed results, it is seen that colour and use of materials are among the most influential façade aspects that had contributed to a positive pedestrian experience in the 32 individuals questioned. In a slightly lesser magnitude, pattern and detailing had also contributed to a positive pedestrian experience. On the contrary, a building façade’s colour was also portrayed as a key contributor to negative pedestrian experiences, and in a similar but less impact, a building’s façade use of materials.

ASPECTS OF FACADE DESIGN THAT ELEVATED PEDESTRIANS’ MENTAL / PHYSICAL STATE

TOTAL NUMBER OF SELECTION

ASPECTS OF FACADE DESIGN THAT DETERRED FROM PEDESTRIANS’ MENTAL / PHYSICAL STATE

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

FACADE DESIGN ASPECTS

FACADE DESIGN ASPECTS

20

TOTAL NUMBER OF SELECTION

In awareness of further contributions that could have been made by the urban environment, the 32 pedestrians were questioned if they think the overall urban environment affects their judgement of a particular building façade. 31 out of the 32 respondents, thought that the urban environment does indeed affect their judgment of a particular building façade.

4.1.2 WHAT THE CURRENT CASE MEANS

In a holistic view of the general pedestrian questionnaire results, three key points conclude what the current case means. The first, is that pedestrians are indeed affected by buildings’ façade design when in urban spheres. The investigation of such, highlighted that this is the case for the majority – where pedestrians have never been mentally or physically affected by a building façade, they form a minor percentage compared to those who have. The second point is that while certain aspects of building façades have the potential to impact pedestrians’ experience positively or negatively in stronger capacity than other aspects, a certain aspect may be the primary driver in both positive and negative experiences simultaneously, if examined regarding different individuals. It is acknowledged that this further depends on the characteristics of the facade aspect, but the concept nevertheless remains the same. Finally, pedestrians feel and are aware of, the urban environment’s capacity in impacting their subjective opinions about building façade designs.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

21

4.2 THE IMPACT OF: MONTCALM EAST, THE BLAVATNIK, THE RUBENS, AND THE VIACOM, ON PEDESTRIANS

4.2.1 THE URBAN ENVIRONMENT(S)

Undoubtfully, each urban environment is representative of facets that speak of how a pedestrian is to encounter the space around them and the impressions they consequently conceive. If anything has been enforced by the previous sections of the study, it is the dynamic relationship between individuals and the built environment. For this reason, that the comparison of the case studies to one another betters the understanding of the subject matter more holistically and is hence the adopted approach of investigation.

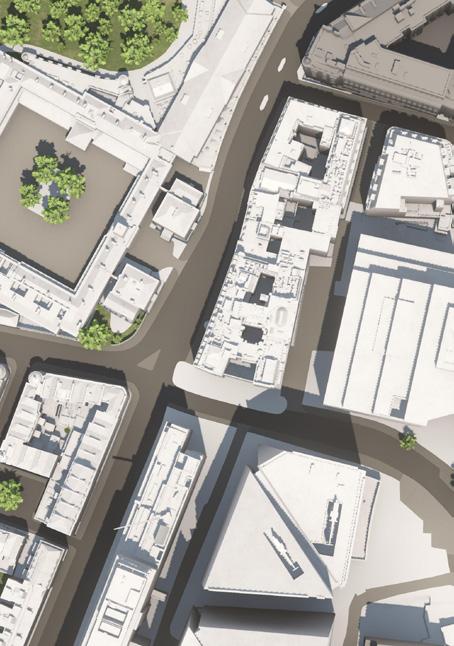

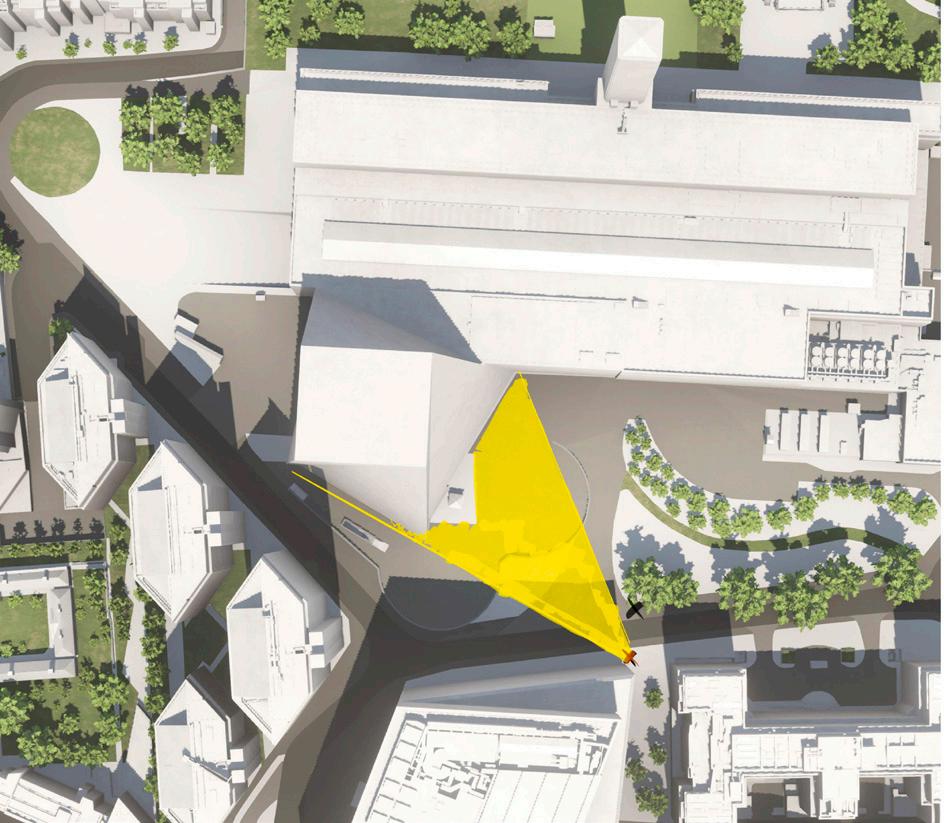

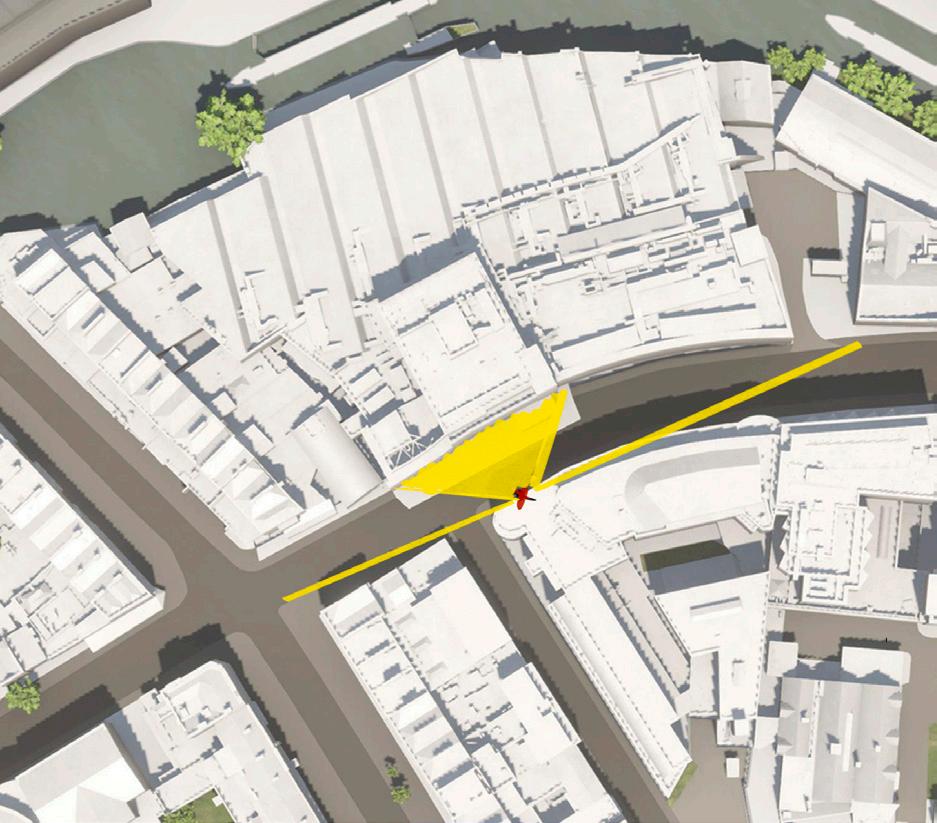

Initially, mapping gives an overview of the spatial organisation each case study encompasses. From which, vehicle and pedestrian pathways are identified, streetscape dimensions are understood in proportion to surrounding buildings, greenery is located, and boundaries within the urban space are highlighted. In reference to the surrounding environment of Montcalm East, the Blavatnik, the Rubens, and the Viacom, figure(s) 4.4 presents a map of each case with an ‘x’ marking the field work set-up and a highlighted area marking the space where pedestrian were approached, and the questionnaires conducted. Inclusive of this, are photographs of the buildings taken during the field work.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

22

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022 MONTCALM EAST BLAVATNIK RUBENS VIACOM x x x x x Field of vision looking towards the building Area of which questionnaires were conducted Location of environmental monitoring set-up 23

In formulating those findings into a quantifiable form, Hillnhütter’s (2021) environment matrix serves a foundation of more accurately comparing the buildings’ urban environments to one another through four different conditions scoring of seven environmental features. Appendices 8, 9, 10, and 11 show the environment matrix with condition scoring in relevance to Montcalm East, the Blavatnik building, the Rubens hotel, and the Viacom respectively. As an overview, figure 4.5 provides as a summary of the condition scores each urban case achieves. Essentially, what occupies a greater condition score, implies a better level of quality within the feature listed. Where for instance, the feature of greenery with a condition score of four implies an intense and dominant well-designed greening with trees, scenic view, park – whereas a condition score of one translates to no elements of greenery incorporated. In further documentation of the urban environment, table 4.1, presents general and time stamped observations of the surrounding environment made during the field work for each case study.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

Car Restrictions 1 3 2 2 Shops & Services 2 2 3 4 Social Activity 2 3 4 4 Enclosure 1 1 2 3 Edges, Facades 3 3 3 2 Streetscape Appearance 3 3 3 2 Green 1 3 2 2 24

MONTCALM BLAVATNIK RUBENS VIACOM

MONTCAL EAST

•

SURROUNDING ENVIRONMENT OBSERVATIONS

•

BLAVATNIK

A corner view of the building’s facade gives a stronger impression compared to a front view

• Weather is partly cloudy and windy

•

RUBENS

• 10:20

• 11:22 - Large vehicles passing through adjacent road

• 12:51 - Large population of pedestrians in the area

• 13:00+ - Position of the sun changed, sunlight directed at the West facade of the hotel

• Various greenery - trees are of the Oak breed - creating a consistent sound of tree rustle from wind

• Museum artwork in display along the sides of the pedestrian street

• 10:25 - Surrounding environment is quite - sound of trees rustling can be heard

• 10:00 - 11:00 - Minimal number of pedestrians

• 12:22 - 12:24 - Tate Modern service truck playing soft music loudly

• Area is not busy

• Public seating and a diverse range of greenery present

• Facade of the building incorporates a public display of art

• Road adjacent to the building has large vehicles and buses passing through it

• Faint construction noise in the background

• Sounds of birds chirping

• 10:34

• 11:30 - 15:00 - Vertical green wall system maintenance - workers trimming down the plants

• 12:49 - Environment becoming more crowded - more pedestrians

• 14:20+ - Sound of leaf blower - workers cleaning up after vertical green wall system maintenance

• Quite area

• Short buildings surrounded by 3-6 metre wide roads

• Cars are parked on the sides of the road

•

•

VIACOM

•

•

•

No signs of birds nestled within vegetation of the vertical green wall system of the Viacom

• Work vehicles passing through building’s adjacent street

• 11:46 - Vertical green wall system maintenance - workers using leaf blower to remove fallen bits of vegetation from the lower section of the facade - producing noise in the process

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

25

With all four environments catering for unique pedestrian encounters, in each scenario; pedestrians were approached and asked about their perception of the urban environment altogether. The questionnaire gathered responses from 25 pedestrians by Montcalm East, 30 pedestrians by the Blavatnik building, 31 pedestrians by the Rubens hotel, and 30 pedestrians by the Viacom building. Within this, pedestrians were given the option to select more than one description formulating what they thought of the space surrounding them. Results presenting pedestrians’ responses within each independent case study are presented in figure 4.6.

PEDESTRIANS’ PERCEPTION OF MONTCALM EAST’S, BLAVATNIK’S, RUBENS’ AND VIACOM’S URBAN ENVIRONMENT

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

ENVIRONMENT DESCRIPTION TOTAL NUMBER

OF SELECTION

MONTCALM BLAVATNIK RUBENS VIACOM TEMPERATURE (°C) MINIMUM 17 20 19 20 MAXIMUM 27 29 26 28 AVERAGE 21 23 22 22 LIGHT (LUX) MINIMUM 1612 1068 8337 12791 MAXIMUM 32280 32280 32280 32280 AVERAGE 17169 29250 19474 25953 SOUND (dBA) MINIMUM 53 53 X X MAXIMUM 119 82 X X AVERAGE 69 60 X X

26

In further acknowledging the non-tangible properties of the urban environment, table 4.2 presents minimum, maximum, and average values of temperature, light, and sound levels retrieved from field work monitoring in each case study respectively. Where the corresponding environment of the Rubens hotel and the Viacom building are missing sound data, this is because the instrument had reached full capacity prior to both cases.

4.2.2 THE BUILDING(S) & THEIR FACADE DESIGN

In directing focus towards the buildings in investigation, the approached pedestrians within each case study had been asked to share their opinions on the exterior building design of the Montcalm hotel, the Blavatnik building, the Rubens hotel, and the Viacom building respectively. Within this, pedestrians had been given the option to choose if they perceived the building as beautiful, disturbing, or neither. As the number of respondents in each case was different from the other, results presented in figure 4.7 display a percentage value as well as the number of pedestrians. Evidently, more than half of the approached pedestrians within each case perceived the building in question as beautiful. Those who perceived Montcalm East and the Blavatnik building beautiful accounted to double of those who had perceived the building as neither beautiful nor disturbing. Where pedestrians were disturbed by the exterior design of any of the buildings, the Blavatnik building consisted of the highest count compared to the other cases. Moreover, none of the approached pedestrians found the exterior of the Rubens or the Viacom disturbing. In fact, those who perceived the Rubens as beautiful accounted for more than triple of those who found it neither beautiful nor disturbing.

BUILDING(S) RESPONSES IN PERCENTAGE

However, to better understand how the characteristics of the investigated buildings have influenced pedestrians’ perceived experience, the buildings’ form, features, and dimensions have been identified through design metrics and established into an accordingly descriptive ID via the façade configuration system. The façade design configuration ID of Montcalm East, the Blavatnik building, the Rubens hotel, and the Viacom building are presented in appendices 12, 13, 14, and 15 respectively. The resulting classifications are additionally portrayed in table 4.3. Evidently, the Montcalm East hotel and the Blavatnik building share common characteristics while the Rubens hotel and the Viacom building share other commonalities. The discussion arising from this however will be discussed in later sections.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

PEDESTRIANS’ PERCEPTION OF MONTCALM EAST’S, BLAVATNIK’S, RUBENS’ AND VIACOM’S EXTERIOR BUILDING DESIGN

27

MONTCALM 1:DX42222

BLAVATNIK 1:FS42222 RUBENS 1:AV22321

VIACOM 1:BV22324

4.2.3 THE PEDESTRIAN EXPERIENCE

In investigating the pedestrian experience, observations made within each of the case studies’ surrounding environment revealed trends in pedestrians’ behaviour. As presented in table 4.4, the observation of pedestrians’ as they came into visual contact with buildings, highlighted that within urban encounters individuals are likely to take photographs of a feature that is of probable interest. In cases, it may be that the function of the building has made it worthy of photography – especially if the building function is subject in being a tourist attraction. For instance, the function of the Blavatnik building as a museum might have driven its audience to capture its essence regardless of whether they find it beautiful or not. In other cases, it might be that the action of photography within the majority that has encouraged others to do the same, such as what is implied in context of the Rubens hotel. The ideas behind why individuals may feel the need or simply want to capture a visual commemoration expands beyond the scope of this study, but it nevertheless implies a greater reasoning behind the action.

VIACOM

PEDESTRIAN OBSERVATIONS

• Pedestrians passing by building would look over at building facade

• 10:55 - Pedestrian taking photograph of building

• 11:35 - Pedestrian taking photograph of building

• 12:07 - Pedestrian taking photograph of building

• 13:06 - Pedestrian taking photograph of building

• 13:28 - Pedestrian taking photograph of building

• 13:37 - Pedestrian taking photograph of building

• 14:02 - Pedestrian taking photograph of building

• 14:55 - (4) Pedestrians taking photograph of building

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

FACADE DESIGN CONFIGURATION ID

28

MONTCAL EAST

PEDESTRIAN OBSERVATIONS

• Man stands for a few moments and looks at the building from a corner view - behaves in a curious manner

• 10:28

• 10:33

• 11:58

• 13:24 - Pedestrian taking photograph of building and zooming in on it

• 13:44 - Pedestrian taking photograph of building

• 13:46 - Pedestrian taking photograph of building

• 14:15 - (2) Pedestrians taking photograph of building and discussing its appearance

• 14:18 - Pedestrian looking at the building oddly

• 14:35 - Pedestrians talking about how the facade of the building looks like an optical illusion - stating they

• Pedestrians would sit on benches provided infront of the Blavatnik building, where one side is facing the building and the other the pedestrian street, pedestrians would choose to sit facing the pedestrian street

• 10:24 - Pedestrian taking photograph of building

• 10:31 - Pedestrian taking photograph of building

BLAVATNIK

• 11:10 - Pedestrian taking photograph of building

• 11:50 - Pedestrian taking photograph of neighbouring building but not the Blavatnik building

• 11:56 - Pedestrian taking multiple photographs of building

• 12:17 - Pedestrian stopped walking to take photograph of building

• 12:39 - Pedestrian looking at building oddly for aproximately 10 seconds - voicing to companion “this is a weird building”

• 12:58 - (2) Pedestrians having lunch on a bench and looking at the building

• 13:04 - (2) Pedestrians stopped walking to take a photograph of the building

• 13:17 - (2) Pedestrians taking photograph of building

• 14:11 - (2) Pedestrians taking photograph of building

• 14:24 - (2) Pedestrians taking photograph of building

• Pedestrians at street crossing point would look at building facade for more than a few seconds

• 10:06 - Pedestrian pointing to facade

• 10:24 - Pedestrian taking photograph of building

• 10:32 - (2) Pedestrians taking photograph of building

• 10:53 - (3) Pedestrians taking photograph of building

• 11:07 - (2) Pedestrians taking photograph of building

RUBENS

• 11:10 - (2) Pedestrians taking photograph of building and pointing at it

• 11:21 - (3) Pedestrians taking photograph of building

• 11:33 - (3) Pedestrians pausing from their walk to look at building

• 11:35 - (3) Pedestrians taking photograph of building

• 11:53 - (4) Pedestrians taking photograph of building

• 12:05 - (2) Pedestrians taking photograph of building

• 12:42 - (2) Pedestrians taking photograph of building

• 13:10 - (5) Pedestrians taking photograph of building

• 13:56 - (4) Pedestrians taking photograph of building

• 14:15 - (4) Pedestrians taking photograph of building

• 14:24 - (2) Pedestrians taking photograph of building

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

29

Fulfilling more focused findings, the pedestrians approached and questioned in proximity of the case studies reveal the impact the buildings’ façade on their subjective experiences. The questionnaire investigated the variety of positive and negative affect the buildings’ façade induced in pedestrians if any, and what characteristics of the façade this was a result of. It is crucial to note that within this, pedestrians were able to choose more than one feeling as a result of more than one façade design characteristic - as feelings are unrestrained when it comes to real life experiences. Initially, it is wise to reveal what positive and negative feelings pedestrians had encountered before identifying what this was a result of.

That being established, figure 4.8 shows what positive feelings pedestrians within each case study scenario experienced as a result of the buildings’ façade. In context of Montcalm East, it is seen that the feeling of admiration was a mutual experience for 15 of the approached pedestrians. In similar but lesser magnitude, the feeling of curiosity was also experienced by 12 of those approached. Regarding the Blavatnik building, most pedestrians had experienced the feeling of curiosity – amounting to 16 votes from the 30 individuals approached. Notably, a predominant positive feeling common in context of both the Rubens and the Viacom was that of visual comfort. Where 31 pedestrians were approached in proximity of the Rubens hotel, 19 of those felt visual comfort and 17 out of the 30 pedestrians approached near the Viacom building, voted for visual comfort.

VXGC7 SEPTEMBER 2022

FEELING

OF

30

POSITIVE FEELINGS EXPERIENCED BY PEDESTRIANS AS A RESULT OF CASE STUDIES’ FACADE

TOTAL NUMBER

SELECTION