HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENT

HEALTH AND WELLBEING IN CITIES: THEORY AND PRACTICE

BENV0056 VXGC7

Designing London’s Recovery.....................................................................................................................02 A Health Impact Assessment Approach.....................................................................................................04 C O N T E N T S 1.0 INTRODUCTION 2 . 0 M E T H O D O L O G Y 1.1 1.2 1.1.1 1.1.2 The 15-Minute Child Led Neighbourhoods Initiative..................................................................02 The Context: The London Borough of Newham..........................................................................03 The Overall HIA Process............................................................................................................................06 Stage 1: Planning & Scoping.........................................................................................................................09 Stage 2: Collecting & Assessing...................................................................................................................17 Stage 3: Engaging & Observing....................................................................................................................18 Stage 4: Reflecting & Reporting..................................................................................................................18 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 3 . 0 K E Y F I N D I N G S 6 . 0 L I M I T A T I O N S & F U R T H E R R E S E A R C H 7 . 0 R E F L E C T I O N S O N T H E H I A P R O C E S S 9 . 0 A P P E N D I X HUDU’s rapid HIA tool on social cohesion and inclusive design..............................................................44 Addressing the assessment criteria of social cohesion and inclusive de- sign from the HUDU rapid HIA tool in Miro...........................................................................................................................................44 Presentation..................................................................................................................................................45 1 2 3 p. 19 p. 35 p. 37 p. 43 p. 05 p. 01 Social Cohesion, Health & Wellbeing.........................................................................................................20 Overview of Findings...................................................................................................................................20 Big Roads.....................................................................................................................................................24 Green Spaces..............................................................................................................................................25 Pedestrianised Streets.................................................................................................................................26 A Sense of Community................................................................................................................................27 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 ii 1.2.1 Aims & Rationale of the Study......................................................................................................04 4 . 0 R E C O M M E N D A T I O N S 5 . 0 C O N C L U S I O N S p. 29 p. 33 8 . 0 R E F E R E N C E S p. 40

1.1 1.2 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7

F I G U R E S

F I G U R E S

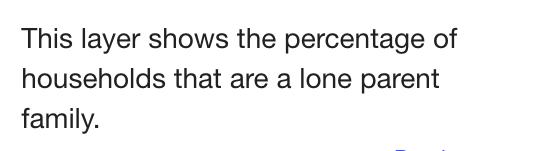

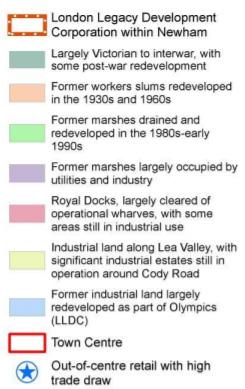

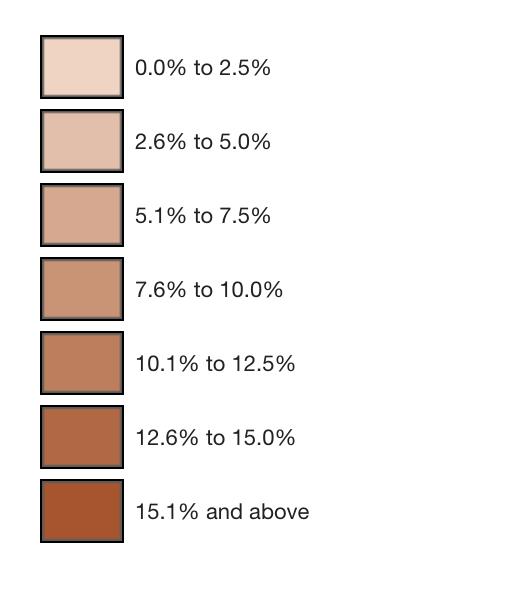

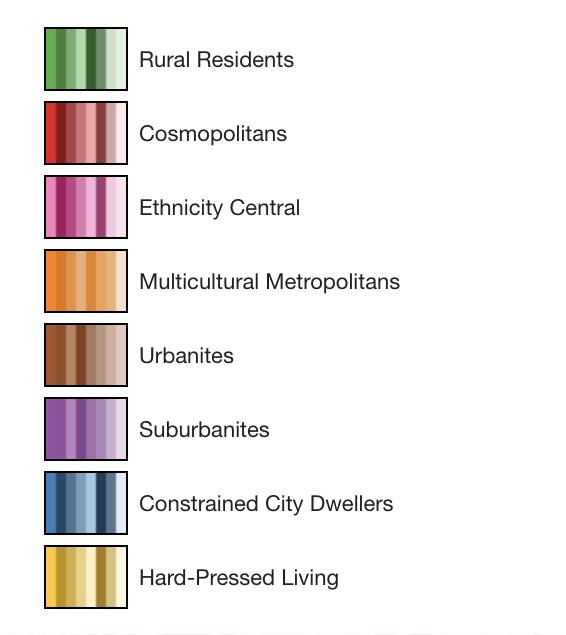

The nine missions areas for London’s Recovery Programme..................................................................02 Map of Newham..........................................................................................................................................03

Overall methodology process of the HIA................................................................................................07 Newham’s typological & societal distribution...........................................................................................11 Overlay of mapping categories...................................................................................................................13

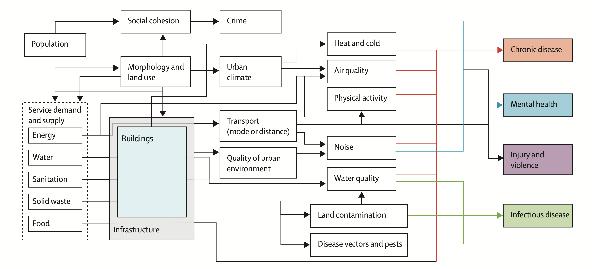

Rydin et al., (2012) different urban contexts framework.........................................................................10 Causal mapping of health & wellbeing indicators against Rydin et al., (2012) different urban contexts framework...................................................................................................................................................15

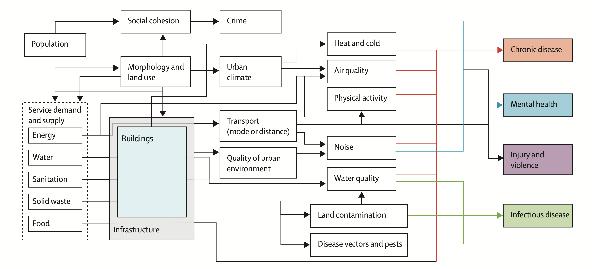

Social cohesion within connections of health outcomes and the urban environment - adopted from Rydin et al., (2012).....................................................................................................................................20

15-Minute diameter map of Beckton relative to the assessed aspects...................................................22 Photographs taken during the site visit relative to the investigated area..............................................23

15-Minute diameter map of Beckton relative to ‘big roads’....................................................................24

15-Minute diameter map of Beckton relative to ‘green spaces’..............................................................25

15-Minute diameter map of Beckton relative to ‘pedestrianised streets’..............................................26

15-Minute diameter map of Beckton relative to ‘community centres’...................................................27

iii L I S T O F F I G U R E S

iv

2.1 2.2 3.1 3.2 4.1 7.1 L I S T O F T A B L E S

T A B L E S What 15-minute child led neighbourhoods mean with regard to health & wellbeing indicators.........09 Reasoning behind the selection of mapping categories............................................................................10 Overview of findings gathered from primary and secondary research..................................................21 Beckton local’s responses to the conducted survey.................................................................................28 Recommendations of action...................................................................................................... .................31 Roles and responsibilities throughout the HIA process..........................................................................39

- ENRIQUE PEÑALOSA (FORMER MAYOR OF BOGOTA)

01

1.0 introduction

“Children are a kind of indicator species, if we can build a successful city for children, we will have a successful city for everyone.”

1.1 DESIGNING LONDON’S RECOVERY

Planning London’s Recovery is the Mayor of London’s new challenge program that takes on a cooperative, design-led approach to supplement advancement and innovativeness within London’s Recovery in response to the pandemic. It is being conveyed in organization with the GLA, Design Council and UCL’s CUSSH project.

1.1.1 THE 15-MINUTE CHILD LED NEIGHBOURHOODS INITIATIVE

Adopting a specific initiative to address the raised missions presented in figure 1.1 (GLA, 2020), the Sustrans organisation proposed the concept of ‘Child-led 15-Minute Neighbourhoods’ – with an aim to explore how streets and neighbourhoods can be made more accessible to children and shift the current power imbalances to shape a greener and more equitable future. This initiative drives the urban scape to uphold the needs and values of children, adults, and the environment, and encourages the idea of fruitful city planning in harmony with intergenerational inclusivity.

02

1.1.2 THE CONTEXT: THE LONDON BOROUGH OF NEWHAM

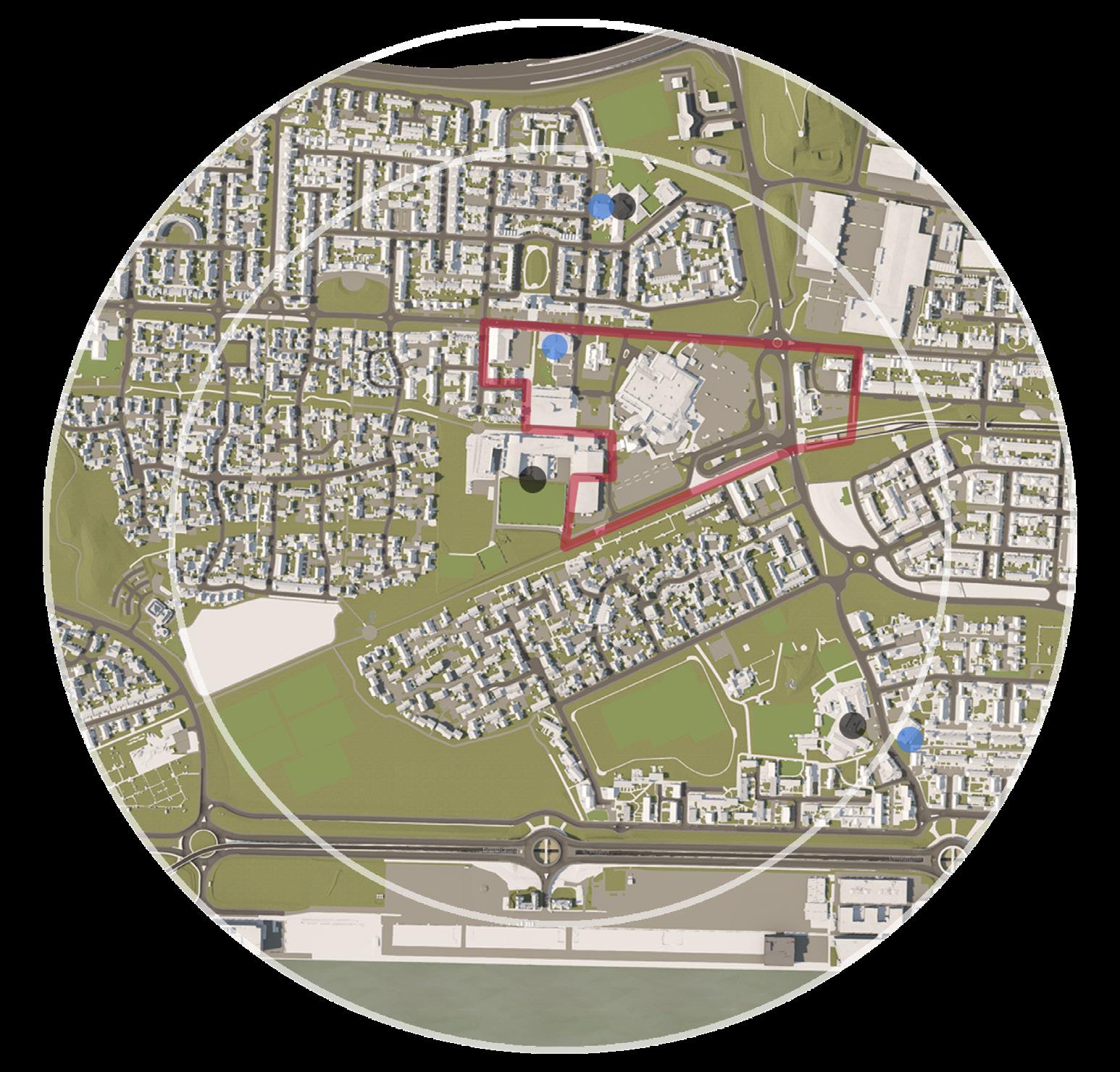

Following the vision of Sustrans more closely, the notion of breaking barriers to childhood independence through making car-centric outer London boroughs more people-centric, prompts this study to focus on Newham to consequently investigate how the initiative of 15-Minute Child Led Neighbourhoods can conform with the set missions, and subsequently promote residents’ health and wellbeing. Considering this, the study advances to address Beckton in later focus. Figure 1.2 presents a map of Newham with an overview on the borough’s background.

A

BACKGROUND

ON NEWHAM

Population: 352,005 Area: 36.21 km ² Businesses: 14570 New Homes: 2377

Passengers: 253,000,000

03

1.2 A HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENT APPROACH

Defined by the World Health Organisation, a Health Impact Assessment (HIA) is “a combination of procedures, methods, and tools by which a policy, programme or project may be judged as to its potential effects on the health of the population, and the distribution of those effects within the population” (WHO, 1999) p.4. It is further recognised as a practical approach that focuses on vulnerable or disadvantaged groups – and ultimately, recommendations for decision-makers and stakeholders are informed from such and guided by the aim of maximising positive health outcomes whilst minimising negative ones (WHO, n.d.).

1.2.1 AIMS & RATIONALE OF THE STUDY

Within the scope of this study, the HIA approach aims to assess the stance of Newham in terms of Sustran’s ’15-Minute Child Led Neighbourhoods’ concept. From such process, this study will be able to identify and assess health impacts on the population. Effectively, where there is room for critique and improvement, this will be communicated through recommendations and future research.

04

05

2.0 METHODOLOGY

2.1 THE OVERALL HIA PROCESS

Responding to the challenge, the HIA process proceeds to adopt a non-linear action research strategy. This consists of exploring the context and subject matter broadly and accordingly advancing with focused action, all whilst transferring back and forth between stages. The following figure 2.1 - illustrates the overall process of the HIA carried out by the group. Where the author had a contributing role in this, the box is highlighted in green.

06

15 - Minute Child Led Neighbourhoods Mean

Health & Wellbeing Indicators

Causal Mapping of Health & Wellbeing Indicators

Integrating Causal Mapping into Rydin et al.’s Framework

‘Social Cohesion’ as Key Topic Focus

Newham Typology & Societal Mapping

Potential Areas of Focus

Beckton as Area of Focus

HUDU Rapid HIA Tool on Social Cohesion & Inclusive Design

HUDU Rapid HIA Tool on “ ”

Raised Assessment Criterion

Primary Research Secondary Research Beckton Site Visit 15 - Minute Diameter Mapping

Background Research on Newham STAGE 2: COLLECTING & ASSESSING

Observations 10 Surveys from Beckton Random Locals Photographs

07

STAGE 1: PLANNING & SCOPING

Stakeholder Panel Presentation

Feedback from Panel

Re-assessment of HIA Strategy & Future Considerations

Key Findings from the HIA

Recommendations with Actions Limitations & Further Research HIA Process

08

STAGE 3: ENGAGING & OBSERVING STAGE 4: REFLECTING & REPORTING

2.2 STAGE 1: PLANNING & SCOPING

The objective of this stage is to build an understanding on the background and context of Newham. This stage utilises secondary research to scope out the parameters of the HIA and proves sufficient in raising what health and wellbeing indicators will be explored, and consequently what questions will be asked.

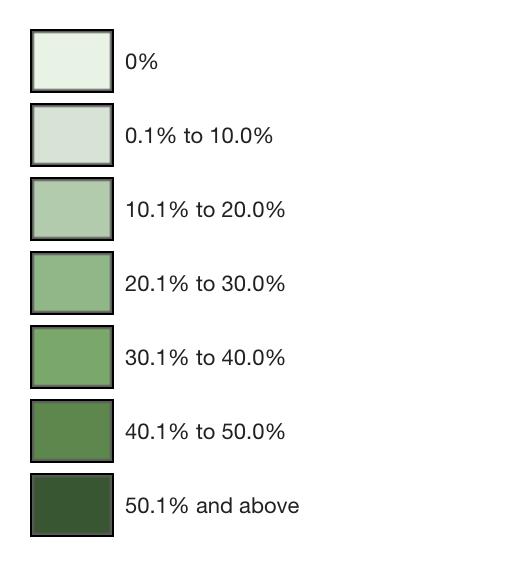

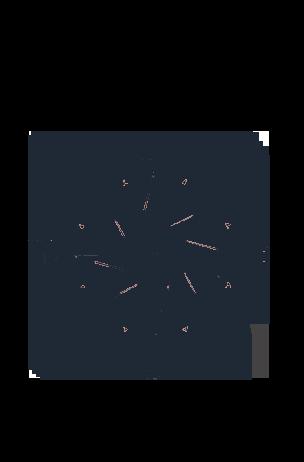

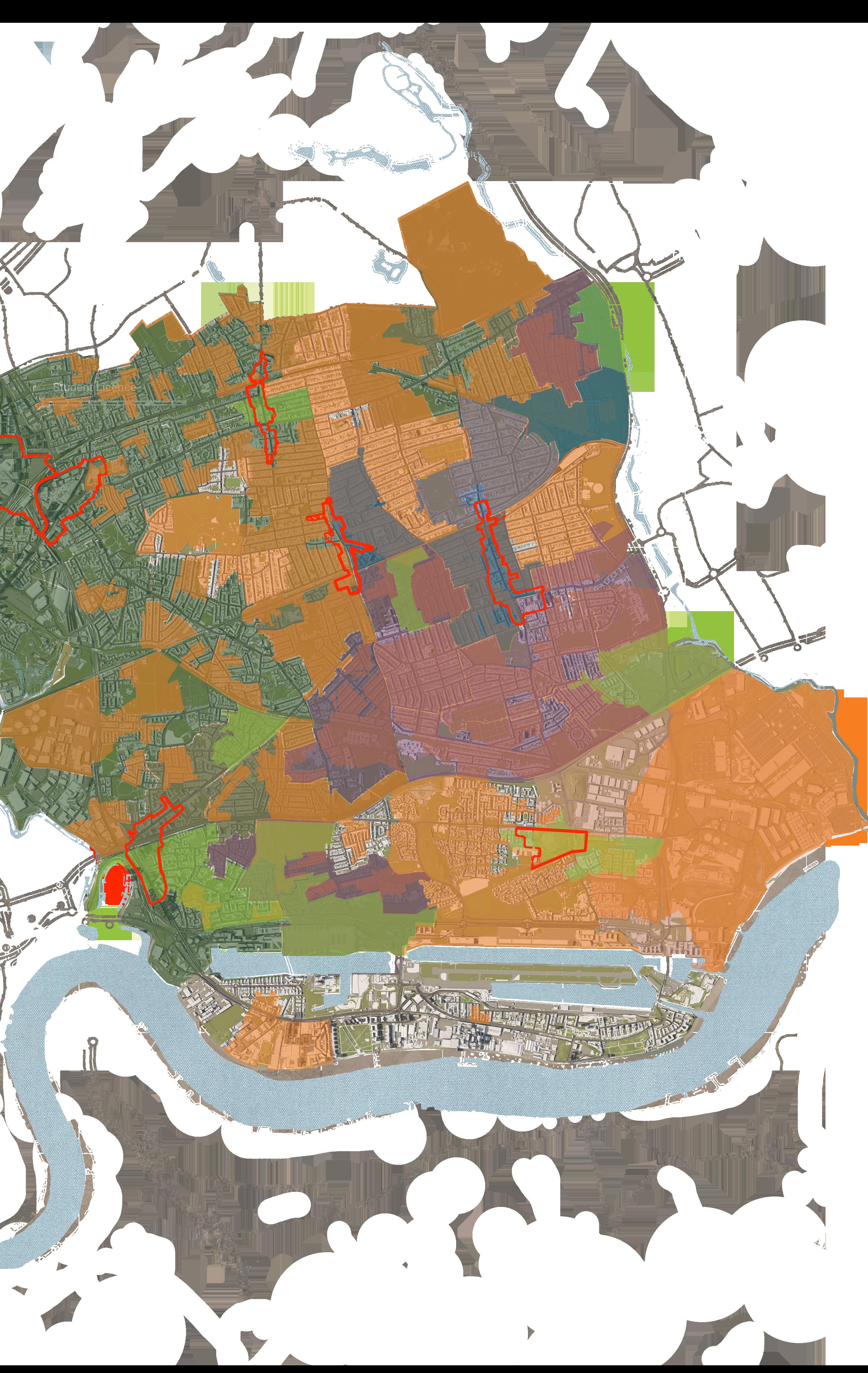

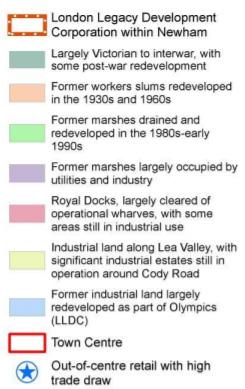

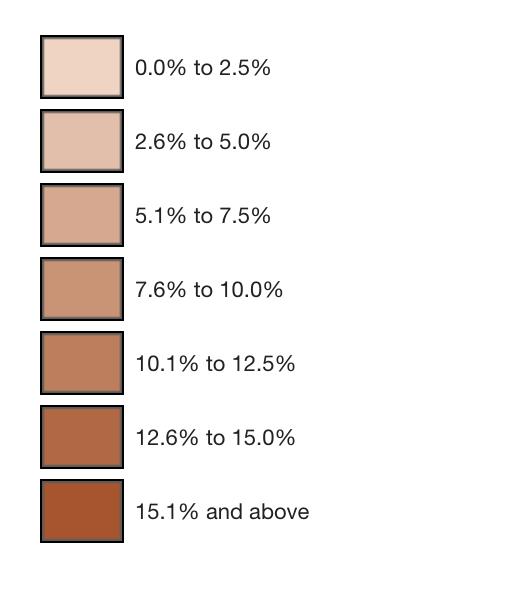

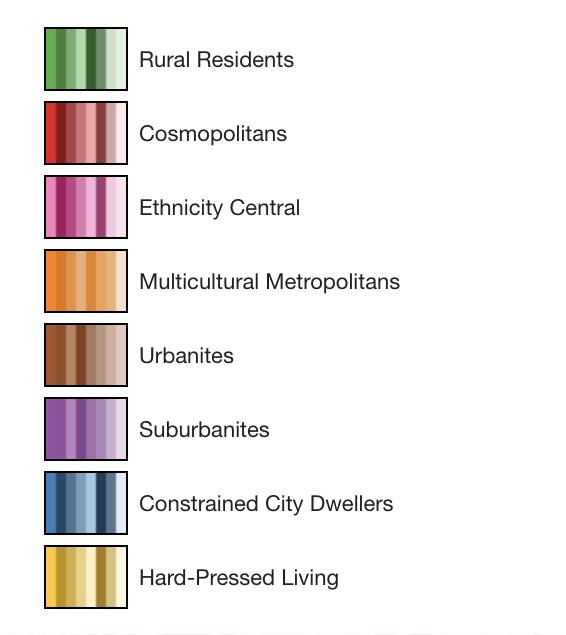

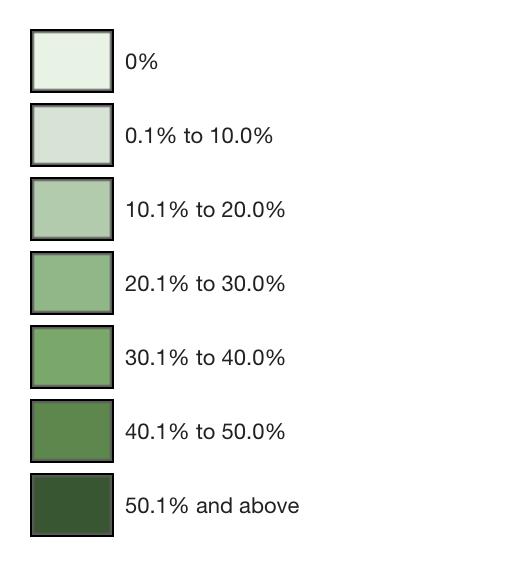

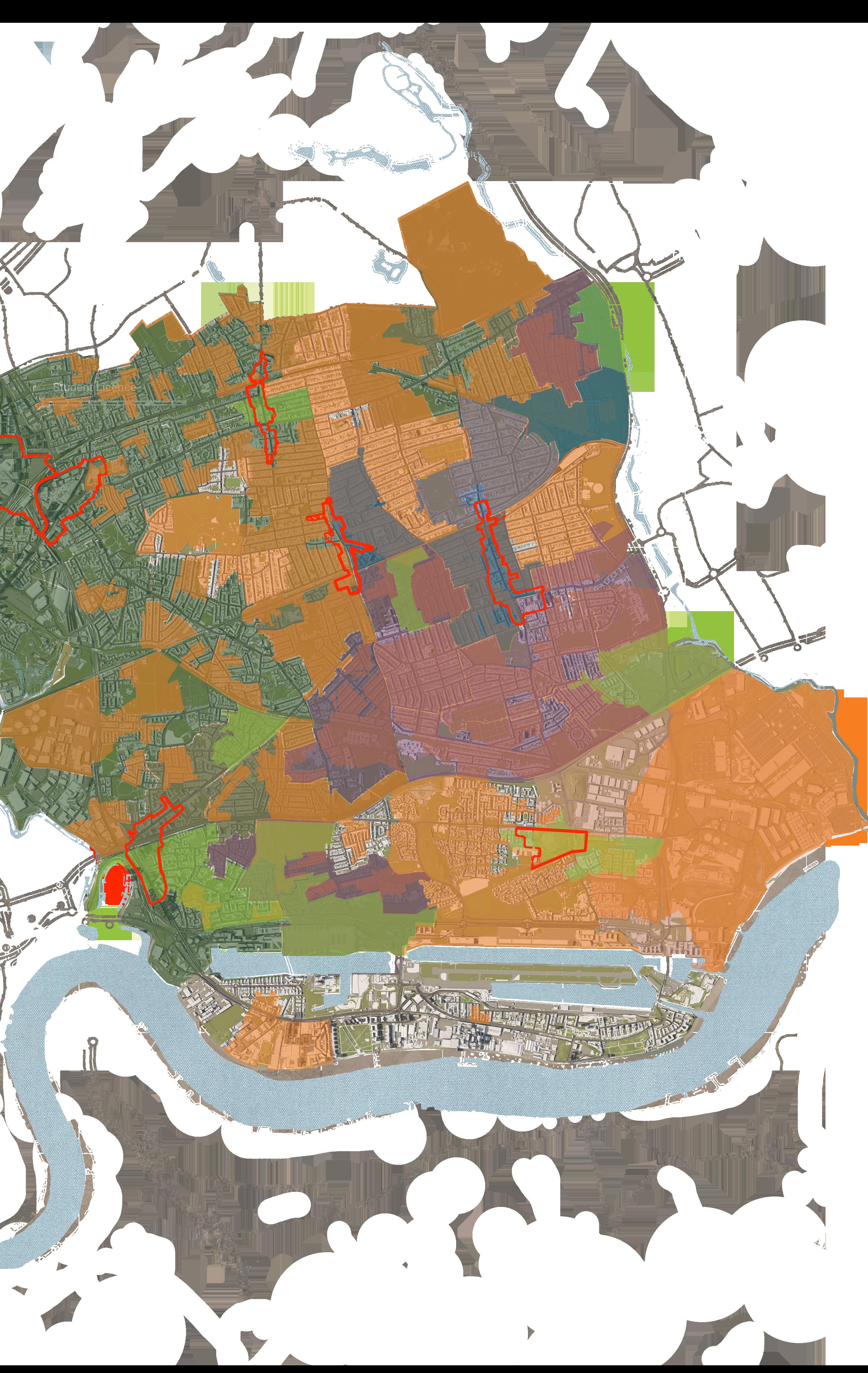

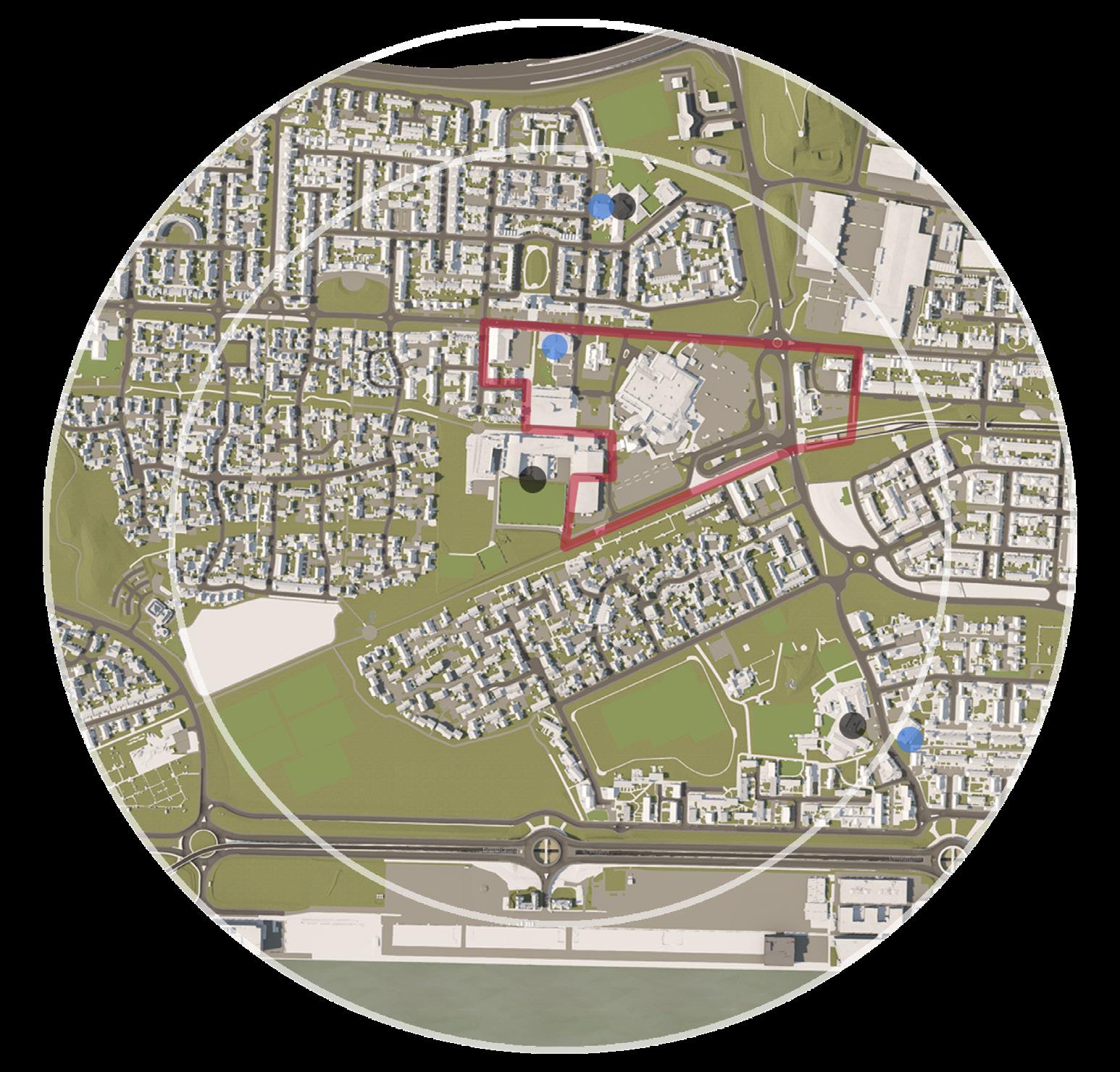

There are two starting points of this stage – the first of them consists of debriefing what 15-Minute Child Led Neighbourhoods mean with regard to health and wellbeing indicators. Table 2.1 expands on five key findings, along with reviewed literature that mutually raise them as integral components of child friendly urban planning. The second point adopts a diagnostic approach and reviews Newham’s typological and societal distribution to identify an area of focus – all mapping categories are presented in figure(s) 2.2, while the reasoning behind the selection of these categories presented in table 2.2. Accordingly, an overlay of important specifications within these categories are presented in figure(s) 2.3 where potential areas of interest are identified. By investigating these four locations, Beckton was chosen as a focal point due to its inclusion of a town centre, three schools, parks, predominant travel pathways, and high deprivation score – proving to be the most suitable for the HIA in terms of ‘15-Minute Child Led’.

HEALTH & WELLBEING INDICATORS

SUPPORTING LITERATURE

Green Infrastructure (Arup, 2017) (Gill, 2021) (Hackney Government, 2021) (Krishnamurthy, 2019) (Montgomery, 2013) (Sugar, n.d.) (UDG, 2020)

09

Space for Play & Social Activity Safe & Uncomplicated Transport & Travel Pathways

of Child Friendly Third Spaces

Lit Streets & Areas throughout Unharmful or Irritating Sounds

Open

Inclusion

Well

WHAT DO 15-MINUTE CHILD LED NEIGHBOURHOODS MEAN?

MAPPING CATEGORY REASON FOR INCLUSION

Summary of Typology Distribution

Index of Multiple Deprivation Score

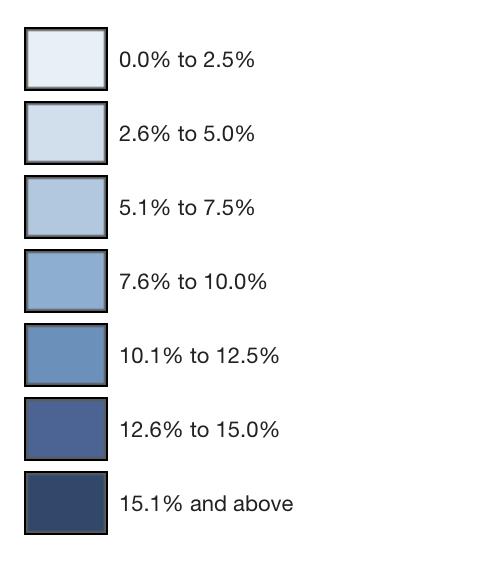

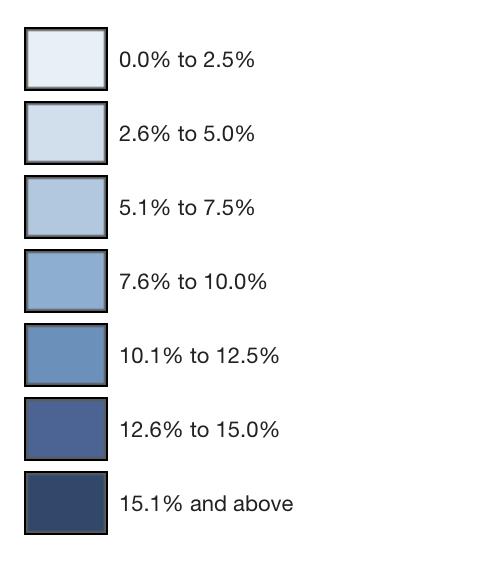

Households with No Cars

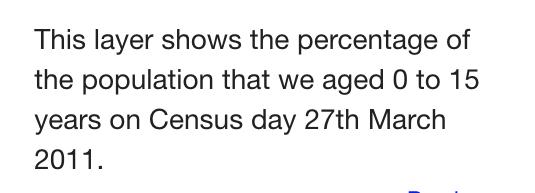

Population Aged 0 to 15

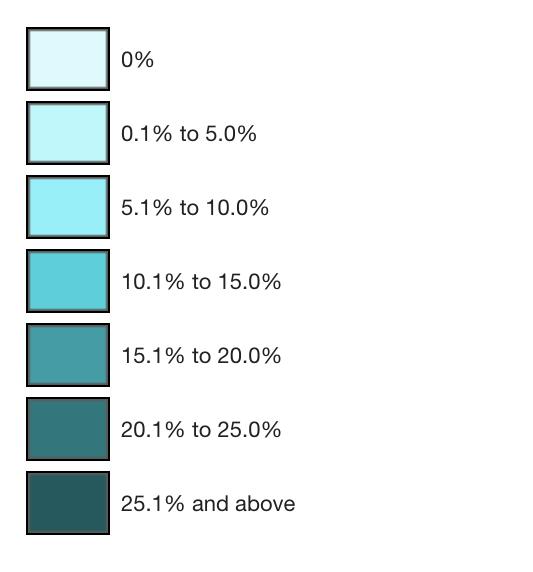

Lone Parents

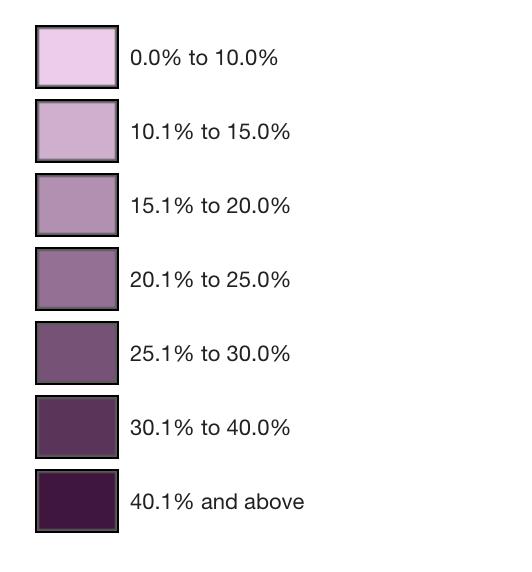

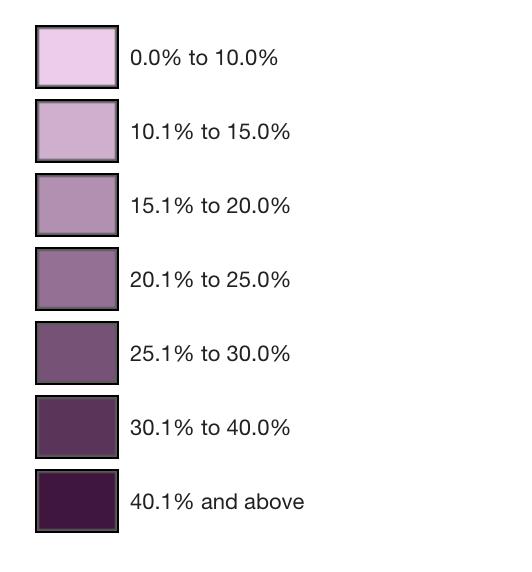

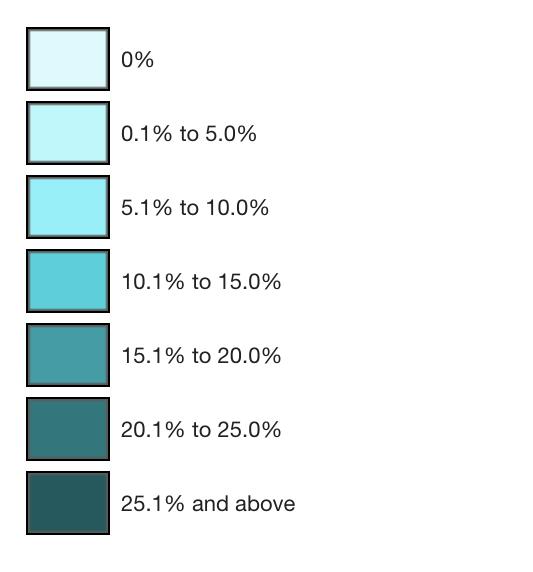

Families with 3 Dependent Children

Neighbourhood Descriptions

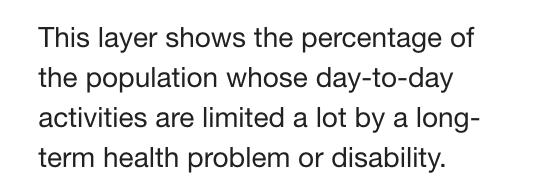

Day to Day Population Activity Affected by Health Problems

To outline town centres or in other words, focal points within Newham.

To identify main areas of deprivation in terms of income, employment, health deprivation and disability, education and skills training, crime, barriers to housing and services, and living environment and hence where an intervention would most likely be needed.

To identify areas where features of accessibility and walkability within Newham would most be important.

To identify the most predominant areas in which children reside - gives direction to assess the application of ‘15-Minute Child Led’ accordingly.

To identify the areas where children are more likely required to be independent as lone parents are more often likely to attend to their children.

To identify where households consist of higher members of children, and hence there are more likely various needs for the family.

To identify where multi-cultural individuals reside within Newham, and hence the consideration of inclusivity regarding diversity .

To identify the areas in which easy accessibility and a health conducive environment is important in response to individuals who are limited by a long-term health problem or disability.

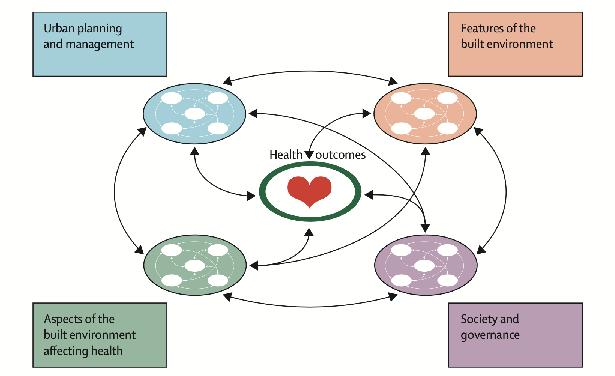

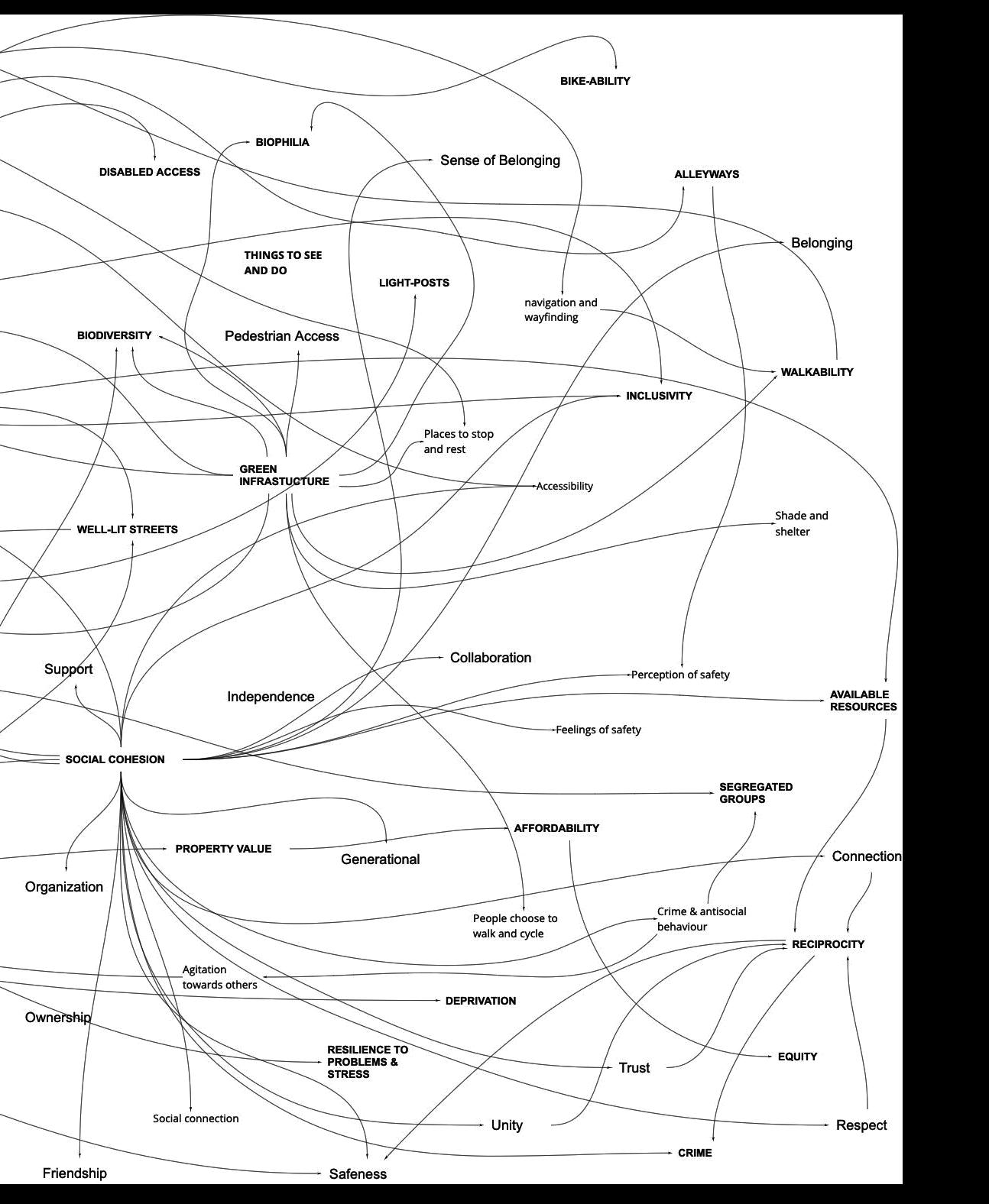

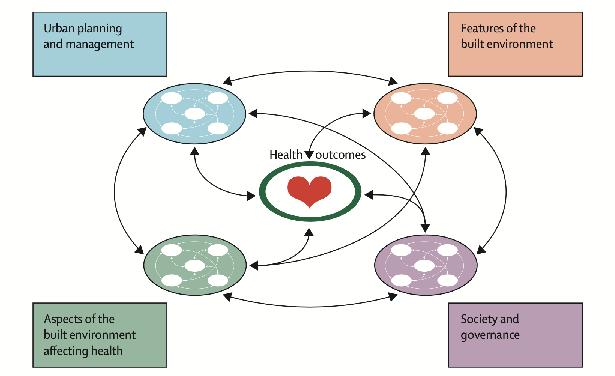

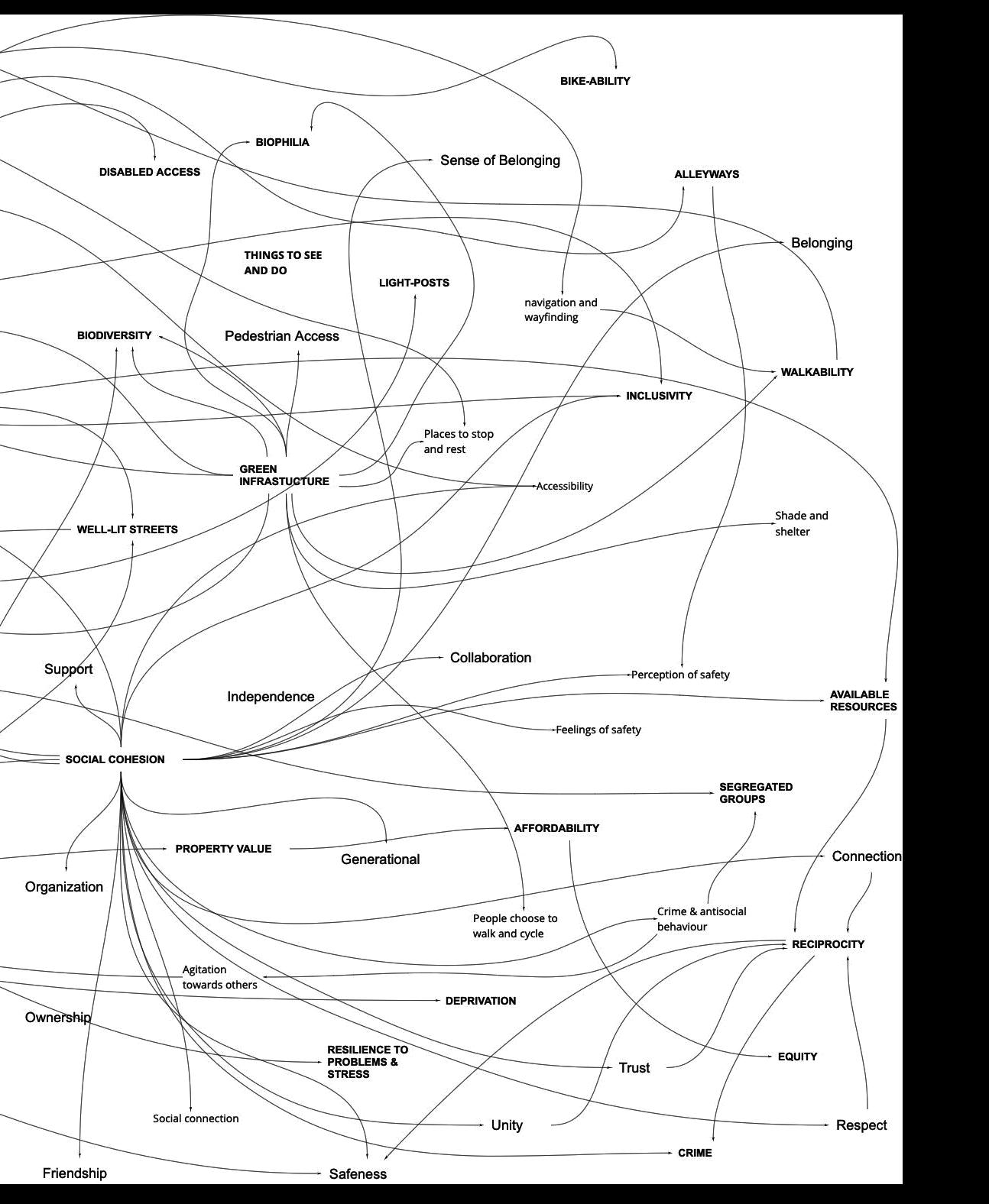

Similarly, a causal map was created from the identified indicators and mapped against Rydin et al., (2012) different urban contexts framework (see figure 2.4) to identify the most predominant contributor to health and wellbeing and hence inform the topic of focus considering different levels of interconnectedness. This is presented in figure 2.5. In result, ‘Social Cohesion’ emphasises its vast interconnectedness with different facets across all four layers. Consequently, this is assessed in Beckton against HUDU’s rapid HIA tool on social cohesion and inclusive design (see appendix 1), with particular focus on aspects that deter or encourage social interaction where further questions are proposed to inform this and are expanded on in stage 2.

10

8.9 to 16.6 16.6 to 24.4 24.4 to 32 32 to 39.9 39.9 to 47.7

This layer shows the index of multiple deprivation score, where a higher score indicates a higher level of deprivation. The IMD is compromised of seven distinct domains of deprivation - income, employment, health deprivation and disability, education and skills training, crime, barriers to housing and services, and living environment.

11 LONE POPULATION AGED 0 TO 15

NEIGHBOURHOOD DESCRIPTIONS DAY TO DAY AFFECTED INDEX OF MULTIPLE SUMMARY OF TYPOLOGY DISTRIBUTION

12 LONE PARENTS FAMILIES WITH 3 DEPENDENT CHILDREN HOUSEHOLDS WITH NO CARS DAY POPULATION ACTIVITY AFFECTED BY HEALTH PROBLEMS MULTIPLE DEPRIVATION SCORE

13

DAY

• Town Centre • Schools • Parks • Third spaces • Rail Stations • Children

• Residential Districts • Commercial Districts +

LONE PARENTS FAMILIES WITH 3 DEPENDENT CHILDREN POPULATION AGED 0 TO 15 NEIGHBOURHOOD DESCRIPTION HOUSEHOLDS WITH NO CARS

TO DAY POPULATION ACTIVITY AFFECTED BY HEALTH PROBLEMS INDEX OF MULTIPLE DEPRIVATION SCORE 39.9 to 47.7 TOWN CENTRES Newham town centres NOTE ON HOW TO READ MAPTHE LESS CLARITY OF THE GEOGRAPHICAL MAP YOU CAN SEE, THE MORE LAYERS ARE OVERLAYED ONTOP OF ONE ANOTHERTHIS IDENTIFIES AREAS OF INTEREST PER THE SELECTED & ANALYSED CATEGORIES CATEGORIES OF INTEREST Beckton...

Centres

14

ASPECTS OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT AFFECTING HEALTH

URBAN PLANNING & MANAGEMENT

15

FEATURES OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

SOCIETY & GOVERNANCE 16

STAGE 2: COLLECTING & ASSESSING

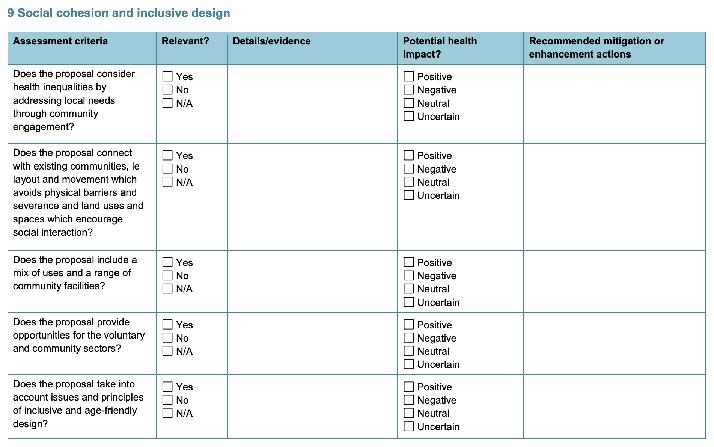

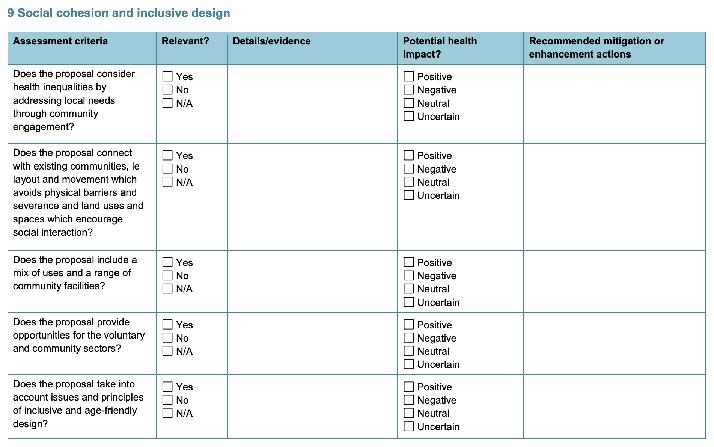

In efforts of gathering information to identify the potential effects of social cohesion on health and wellbeing, this stage advances to collect data that would better inform social cohesion in Beckton and the experiences of whose who reside in the area. However prior in doing so, the assessment criteria needed to be redefined to allow for more focused findings. By briefly addressing the assessment criteria of social cohesion and inclusive design from the HUDU rapid HIA tool (see appendix 2), was the question “Does the proposal connect with existing communities, ie layout and movement which avoids physical barriers and severance and land uses and spaces which encourage social interaction?” determined most effective in assessing the quality of social cohesion. This was nevertheless considered a vague assessment criterion, therefore; the presented questions have been raised to gain deeper insight.

1 - Does the area have big roads (A & B roads) between schools & homes which deter walkable neighbourhoods?

2 - Does the area consider access to green spaces between and near schools (compact/mixed-use space)?

3 - Does the area have pedestrianised streets to encourage safe interaction, connectivity, and permeability?

4 - Does the area encourage a sense of community? How is this expressed by the locals?

To answer these questions, primary research via a site visit within Beckton was carried out. To specifically address question four, a survey to measure social cohesion on a neighbourhood scale created by the organisation Social Life was filled out by 10 random Beckton locals during the site visit – this was developed from the Community Life Survey and the Understanding Society Survey, GLA. Secondary research was carried out via mapping a 15-Minute diameter circle in Beckton, by relevancy to a community school at the centre, and outlining physical elements relevant to the raised questions.

17

2.3

2.4 STAGE 3: ENGAGING & OBSERVING

The adopted approach of assessing impacts of the proposal on health and wellbeing and plans of action research was presented to a panel of stakeholders. This allowed the group to consider a range of viewpoints for assessment, and consequently adopt the outlined methodology. See appendix 3 for presentation.

2.5 STAGE 4: REFLECTING & REPORTING

This stage delivers key findings from the conducted HIA whilst prompting recommendations with actions informed via relevant literature. Further outlining limitations and areas for further research within the HIA, and additional reflections on the overall process.

18

3.0 KEY FINDINGS

19

3.1 SOCIAL COHESION, HEALTH & WELLBEING

Rydin et al., (2012) raises that urban health outcomes result from the mutual interconnection of various descriptors, and of the ways in which social use is made of that environment, how the built environment affects health, and health outcomes themselves. Figure 3.1 illustrates which interventions, inclusive of social cohesion, in the physical fabric of the built environment affect what health outcomes.

3.2 OVERVIEW OF FINDINGS

Within the scope of the HIA, the observations made on big roads, green spaces, pedestrianised streets, and the existing sense of community within Beckton, directed the group to judge their wider potential health impact on locals. The following table 3.1 presents an overview on findings gathered from the primary and secondary research. See figure 3.2 to notice the boundary of the site visit and the corresponding assessments’ physical aspect within the 15-Minute diameter map. Further exhibiting these observations, are photographs taken during the site visit – see figure(s) 3.3. The implications of these findings are however discussed in the upcoming sections.

20

ASSESSMENT CRITERIA

1) Does the area have (A & B roads) between schools & homes which deter walkable neighbourhoods?

2) Does the area consider access to s between and near schools (compact/mixeduse space)?

3) Does the area have to encourage safe interaction, connectivity and permeability?

4) Does the area encourage

How is this expressed by the locals?

KEY FINDINGS

PRIMARY RESEARCH SECONDARY RESEARCH

• There are large roads surrounding the supermarket where the main bus stop/ Beckton station is.

• Central area is busy with cars and accommodates for more vehicles than people.

• There are no cycle lanes.

• There is a greenway that runs between the Kingsford school and residential area. Its location makes it easily accessible for families, students, and others.

• Canopy/tree inclusion is generally good around the school area.

• Most of the pedestrianised pathways are accompanying the big roads.

• There is connectivity between key landmarks but this is not accompanied by other services or forms to encourage interaction such as an open town area or child friendly third spaces.

• Some of explored pedestrianised streets are engulfed by trees and greenery that would question its safety during the day and particularily during the night.

• The 10 locals that were interviewed expressed that there was a sense of community within the area.

• Experience of these people outlined that the area is very diverse, and locals are very accepting of this.

• When the council closed the city farm, locals were able to gather together in protest and campaign for it to return.

• There are a series of big housing districts. They do not however cut through between the school and its corrosponding nearest residential area.

• roads are approximately 8.5 metres wide.

• There are spacious green spaces near the school.

• Some are more easily accessible than others, this has been categorised accordingly.

• The Beckton Dristrict Park is within the outer boundary of the 15-Minute diameter.

• Most of the pedestrianised streets are park / green space pathways rather than people oriented passage routes through the urban scape.

• Where pedestrianised streets are not within parks / green spaces, they extend short distances and situate within residential areas.

• Where pedestrianised streets are external of residential districts and inclusive of third spaces, they accompany car parking lots.

• There are 3 community centres within the 15-Minute diameters area, one of which is the Beckton Community Centre - accessible to all locals, and the others extend from the local church and a children’s sport facility.

• The community is built up from historical post war community ties.

POTENTIAL

HEALTH

IMPACT

Positive Negative Neutral Uncertain

Positive Negative Neutral Uncertain

Positive Negative Neutral Uncertain

Positive Negative Neutral Uncertain

21

22 Schools Community Centres Parks / Playing Fields Easily Accessible Green Space Moderately Accessible Green Space Pedestrianised Streets Big Roads Town Centre 15-Minute Diameter 0.75 miles (Child Walking Speed) 15-Minute Diameter 1 mile (Adult Walking Speed) Investigated Area

23 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Schools

Town Centre

Big Roads

3.3 BIG ROADS

In the case of Beckton and the 15-Minute diameter, big roads segregate each residential district – dividing them into easily recognisable parts (see figure 3.4 for map). In his book Happy City (2013), Charles Montgomery raises that, predominant roads, reconfigure the urban system to accommodate vehicle travel and consequently determine how people move through landscapes. This is a critical point; because not only does this shape the population’s travel behaviour, but it threatens the experience of walking, and deters the social fabric. Big roads further imply heavier traffic – as experimented by Appleyard and Lintell (1972), heavier traffic meant fewer local friends and acquaintances established by residents. While Beckton’s big roads are not predominant in amount, their infrastructure limits how people and children can socialise, play, and cycle (see previous photographs: 1 & 2). Additionally, a car moving at typical city speed uses seventy-five as much space as someone walking (Litman, 2001) – in effect, the neighbourhood’s intent on providing more variety, freedom, and social interaction, expands onto a larger boundary and limits the construct of 15-Minute child led.

24

3.4 GREEN SPACES

Reflecting on the observations, it is evident that Beckton’s inclusion of green infrastructure is vast throughout the 15-Minute diameter area and is in proximity to both residential and commercial districts (see figure 3.5 for map). Where schools are located, an adjacent green space accompanies it – this implies that children can shortly commute or walk to the spaces that encourage them to play and interact with another, all the while being near adult locals for supervision. The challenge of Sustrans’ proposal, however, wants to challenge this dilemma – 15-Minute child led does not merely imply features of the built environment are close to one another, but are further made more accessible to children by the inclusivity of independent travel, safety, and equity. Notably, what the current state of Beckton expresses in theory, is a good case of safety – vast provision of green spaces and vegetation of sorts as observed by Kuo and Sullivan (2001), would imply fewer crime rates even in environments where trees would potentially provide cover for illicit activities.

25

Schools Parks / Playing Fields Easily Accessible Green Space Moderately Accessible Green Space Town Centre

STREETS

The current assessment of Beckton indicates that pedestrianised streets are made supplementary to roads and for passage through green spaces. Where pedestrianised streets are external of this, and inclusive of third spaces, they mostly accompany car parking lots. This may be because the 15-Minute diameter is limited in third spaces, hotspots, and leisure services – and where they are available, they are allocated altogether within the town centre. In result, spacious car parking is presented to conform with this. Nonetheless, this transforms parts of the urban fabric to a home of motorised vehicles, from which the dynamic of parking lots shifts local people interacting towards people just passing through (Montgomery, 2013). In similarity, the investigated pedestrianised street situated within a green space, lacks interventions or services that drive lively encounters (see previous photograph: 8), and in alternative provide route for a serene stroll. With an aim to optimise the use of these spaces, the Beckton community assemblies have raised initiative of proposing play streets that enhance current walkways with play equipment, natural materials, and plants to encourage social interactions, from which a permanent play street within Remington Road has been approved (Saber, 2021) – see figure 3.6 for map.

Schools

Remington Road

Town Centre

Pedestrianised Streets

26 3.5

PEDESTRIANISED

3.6 A SENSE OF COMMUNITY

As expressed by locals, and outlined in table 3.2, most residents can converse with their neighbours, ask them for advice if needed, and are able to get on well with one another, including those from different backgrounds. The willingness of these locals to work together to improve the neighbourhood and their perceived meaningfulness of local friendships, imply that a good sense of community exists within Beckton and its people. While this may be a result of how communities have settled in the area post-war, the variety of community centres in Beckton reinforce the idea that aspects of social interaction and the availability of needed support are available and being carried through today (see figure 3.7 for distribution of community centres).

Community Centres

Schools Town Centre

27

SECTION QUESTIONS ANSWERS

1 What things do you like most about the local area? 2 6 2 2 1

2 The friendships and associations I have with other people in my neighbourhood mean a lot to me.

No Comment

Proximity of Green Spaces Proximity of Supermarkets Low Buildings Routes of Travel

2 5 1 1 0 1

I regularly stop and talk with people in my neighbourhood. 3 5 0 2 0 0

I would be willing to work together with others on something to improve my neighbourhood.

If I needed advice about something I could go to someone in my neighbourhood.

Strongly Agree Agree

Neither Agree / Disagree Disagree Strongly Disagree Don’t Know

Strongly Agree Agree

Neither Agree / Disagree Disagree Strongly Disagree Don’t Know

1 7 1 1 0 0

Strongly Agree Agree

Neither Agree / Disagree Disagree Strongly Disagree Don’t Know

0 5 0 4 1 0

Strongly Agree Agree

Neither Agree / Disagree Disagree Strongly Disagree Don’t Know

3 I borrow things and exchange favours with neighbours in the local area where I live/work in.

The local area where I live/ work in, is a place where people from different backgrounds get on well together.

1 3 3 3 0 0

Strongly Agree Agree

Neither Agree / Disagree Disagree Strongly Disagree Don’t Know

1 7 1 1 0 0

Strongly Agree Agree

Neither Agree / Disagree Disagree Strongly Disagree Don’t Know -

cisions affecting the local area where I live/work in.

0 3 2 4 1 0

I feel safe in my local area. 3 5 0 1 1 0

I feel safe walking alone in the area after dark. 2 3 2 2 0 1

Strongly Agree Agree

Neither Agree / Disagree Disagree Strongly Disagree Don’t Know

Strongly Agree Agree

Neither Agree / Disagree Disagree Strongly Disagree Don’t Know

Strongly Agree Agree

Neither Agree / Disagree Disagree Strongly Disagree Don’t Know

28

29 4.0 RECOMMENDATIONS

Where a feature in Beckton already works, it is advised that policy continue to preserve this to uphold what already works for people.

To create child friendly urban landscapes, policy, participation, design, and management need to be revised and addressed holistically. From such, can communities flourish to build a greater sense of community, include more sustainable high streets and public spaces, and effectively support individuals into good work. Recommendations of action are presented in table(s) 4.1, in its efforts to enhance the explored features relating to social cohesion. It is important to note that some of those recommendations provide actions that require further assessment of Beckton’s physical infrastructure and social dilemma, nonetheless all of them should be tailored to the location in which they would be applied into. Existing features within the neighbourhood, require deep thought into how an intervention will impact the urban fabric and the people surrounding it. The recommendations of action presented are further prioritised in terms of their practical application and urgency to the existing urban scape – this is expanded on below.

Priority Scale

S Short Term – up to 1 year

M Medium Term - up to 5 years

L Longer Term – up to 10 years +

Importance

1 Critical - aspects which are fundamental.

2 Rational – aspects that are important but not as critical as level 1 priorities.

3 Good - aspects which are reasonable to address.

30

BIG ROADS

RECOMMENDATION OF ACTION REASONING / OBJECTIVE SUPPORTING REFERENCE

Adopt the Healthy Streets Framework toolkit to impose interventions that would better the infrastructure of big roads - aim for metrics of high scores.

Improves social, economic and environmental sustainability through how streets are designed and managed - by improving on existing conditions.

Prompts:

• That everyone feels welcome

• Easy crossing

• Shade & shelter

• Places to stop & rest

• Noise reduction

• Walking & cycling

• Perception of safety

• Things to see & do

• People to feel relaxed

• Cleaner air

Night-time restrictions on movement of heavy goods vehicles.

GREEN SPACES

Include cycling networks to accompany roads.

Integrate playful encounters such as public art or creative bus or tram stop designs on big roads.

Ensure the neighbourhood integrates adequate greenery at all scales throughout.

Inclusion of Community gardens.

Applies safety measures for pedestrians, cyclists, and car drivers as well as improving air quality standards, noise reduction measures for properties and street lighting.

Colourful crossings or

and aid driver awareness of pedestrians and street activities.

Reinforces equity as well as sustainability.

Invites playful interaction as part of everyday journeys and activities.

Micro - scaled applications of vegetation serve biophilic health & wellbeing positive outcomes.

Provides opportunities for intergenerational activities, socialising, skills development and outdoor physical activity & gives more vibrancy to green space in Beckton.

(Healthy Streets, 2021)

(Anciaes, Metcalfe and Heywood, 2016)

X X X L2

X X M2

(Arup, 2017)

X X X S1

(Gill, 2021)

(Arup, 2017)

X X X M1

X X X S2

(Montgomery, 2013)

X X X S3

(Arup, 2017)

X X X X S2

Include cycling tracks in parks. Encourages active travel. (Gill, 2021)

X X X M2

31

RELATIVE TO (FEATURE)

CATEGORY PRIORITY

POLICY PARTICIPATION DESIGN MANAGEMENT

PEDESTRIANISED STREETS

RECOMMENDATION OF ACTION REASONING / OBJECTIVE SUPPORTING REFERENCE

Providing multifunctional, playable space - beyond the playground and onto pedestrianised streets.

Apply varied, lively and active services that are exclusive of commercial retail, adjoining pedestrianised streets.

Modify pedestrianised streets

C’s of a good walking network’ framework.

Where pedestrianised streets should be:

• Connected

• Convival

• Conspicuous

• Comfortable

• Convenient

Neighbourhood mapping led by children.

Raise a sense of ownership of public space through co-creation and increased activity.

Visibly expose future construction sites.

A SENSE OF COMMUNITY

A major contribution made by Kevin Lynch on urban placemaking, establishes that urban scapes are successful when societies are able to express and imprint their colourful identities and background into the built environment.

It is hence ecourage that the settlement of Beckton

through monuments and public installations to prompt the resurgence of place identity.

Enables everyday freedom and creates a public realm for all ages to enjoy together.

Blank spaces are less social and safe - this action would also provide job oppurtunities for locals & encourage walkability.

Advocates for adequate mobility of children and other user groups such as eldery and disabled.

(Arup, 2017)

X X X X M2

(Montgomery, 2013)

X X X L2

(Gill, 2021)

X X X M2

Provides deeper insights into an area’s issues and opportunities.

Can help to decrease potential vandalism and maintenance costs.

They can become engaging places and educational assets for the local community, e.g. by hoarding design that makes works visible.

Substantially aids self-expression and the sense of belonging. Values are mutually upheld by locals and are shared between one another.

(Arup, 2017)

X X S1

(Arup, 2017)

X X X X M2

(Arup, 2017)

X X X S3

(Lynch, 1960)

X X X X M2

32

RELATIVE TO (FEATURE)

CATEGORY PRIORITY

POLICY PARTICIPATION DESIGN MANAGEMENT

5.0 CONCLUSIONS

33

With an aim to assess how Beckton and cases alike, can reverse the pattern of rising unemployment and lost economic growth, whilst supporting communities, helping young people flourish, narrowing social, economic and health inequalities, and accelerating the delivery of a cleaner, greener environment - this HIA demonstrated how big roads, green spaces, pedestrianised streets, and a sense of community can strive to meet the demands of such successful urban scape. Its ability to combine this altogether led to the advancement of practical actions that would better the case at hand. It is however important to highlight that the application of these interventions would require a much more rigorous understanding of Beckton as a neighbourhood and the services, policy, management, and stakeholders as a system of governing dimensions. Decision-makers need to account for all people including vulnerable or disadvantaged groups – and this requires a thoroughly reliable case of scrutiny from the earliest of stages.

Regarding vulnerable or disadvantaged groups - the conducted HIA did not take into sufficient account the conditions and needs of those audience. It is therefore unknown if the current case provides a fair and equitable life inclusive to all. This is a critical point; especially in terms of the explored topic ‘social cohesion’ as equality and equity make communities grow stronger. Ultimately, there remains a knowledge gap on definite implications this HIA would have on the community of Beckton and the wider urban fabric overtime – the environment is ever adapting to the shift and growth of individuals and their progressive needs. In the contemporary day however, the goal of health and wellbeing conducive cities, can verily be achieved through the capacity of a HIA.

34

6.0 LIMITATIONS & FURTHER RESEARCH 35

One crucial point raised by the GLA (2020), is that the adopted missions-based approach cannot address all aspects governing successful city making. This further raises the notion of interconnectedness between urban factors, consequently what might work in one aspect might have a negative effect on another. In effect, further research is required to consider and account this amalgam and it is advised to investigate how the urban scape holistically impacts its people and subsequently their individual health and wellbeing.

A weak point within this study, is found within the adopted approach of causal mapping integrated into the Rydin et al., (2012) framework. From which sub-indicators stemming from the main health indicators outlined, were raised based off the group’s judgement. This questions the validity of the level of interconnectedness and the aspects raised – in further research, this is encouraged to be backed up by relevant findings.

Within the scope of this HIA, the adopted approach of utilising HUDU’s rapid HIA as an assessment tool further directed the group to make their own judgments on the potential health impact of aspects observed in Beckton – while this has been backed-up by research, there remains limitations in the reliability of those results. Once more, the HUDU rapid HIA tool focused more on social cohesion and how to assess it accordingly, while it has been concluded that this is an integral component in delivering individual conducive health and wellbeing, it does not tie itself most strongly with ‘health’. Where there would be available resources, this study would encourage the use of the Healthy Streets Framework to better generate an understanding of health metrics within an existing environment. Additionally, the sample number (N=10) on surveys conducted limits the study and raises the same concern of reliability.

Lastly for further research, it is implicit that the 15-Minute child led initiative is assessed with regard to facets external of a 15-Minute diameter area, or else neighbourhoods are likely to neglect valuable wider urban provisions such as food systems that are governed by geographical location.

36

7.0 REFLECTIONS ON THE HIA

37

Proven by the challenges of this project, the HIA demands a collaborative sphere from which it can adequately expand and evolve throughout. This was an interesting opportunity for the author to understand how, much of what is taught in theory, can be integrated into existing environments, especially that of a neighbourhood or city scale. While the starting point of this process was difficult to grasp and direct with a confident stance, the dilemma quickly shifted to one that prompted feeding the curiosity of what different aspects of an urban scape meant for people. As a student that comes from a background of architecture, it was most interesting to conclude that shifts towards a successful neighbourhood may stray significantly from the physical features and involve that of policy, participation, or management – and how this is only viable to achieve when various stakeholders come together in eagerness of bettering a place to better its people. Although focused on social cohesion, the HIA process proved to be a substantial tool for research, exploring the context of Newham and the subject matter of ’15-Minute child led’ broadly and fruitfully.

While it is unfortunate that the author did not get the chance to visit the site and immerse in conversation with locals - it is realised that, even from conducting secondary research, this process asks you to put forth your humanity, place yourself in people’s conditions, and respond to what they need in order to experience and lead humanely ennobling lives.

Further reflecting on feedback received from the presentation, it was realised that to keep a clear focus, the group had to continue questioning what already works in the assessed area, and if these could be scaled rather than doing something new – which is something that strongly conforms with practicality. Roles and responsibilities throughout the HIA process are outlined in table 7.1.

38

SITE ANALYSIS

Case Studies

HIA Approach

HIA PLANNING

COLLECTING & ASSESSING

Research

Background Research: N. Demographics

Background Research: N. History & Development

Background Research: N. Crime Rates

Background Research: N. Green Infrastructure & Natural Assets

Background Research: N. Community Spaces

Background Research: N. Transport

Background Research: N. Air Quality & Noise Pollution

Background Research: N. Access to Healthy Food

Background Research: N. Policies & Strategies

Causal Mapping: Green Infrastructure

Causal Mapping: Noise Pollution

Causal Mapping: Transport / Travel Pathways

Causal Mapping: Child Friendly Third Spaces

Causal Mapping: Lighting / Well-lit Streets

Integrating Causal Mapping into Rydin et al. (2012) Framework

Group Presentation: Content & Research

Research Questions on Social Cohesion

Secondary Research: Large Roads between Schools & Homes which deter Walkable Neighbourhoods

Secondary Research: Access to Green Spaces between / near Schools

Secondary Research: Pedestrianised Streets to Encourage Safe Interaction, Connectivity & Permeability

Secondary Research: Sense of Community

Primary Research: Large Roads between Schools & Homes which deter Walkable Neighbourhoods

Primary Research: Access to Green Spaces between / near Schools

Primary Research: Pedestrianised Streets to Encourage Safe Interaction, Connectivity & Permeability

Primary Research: Sense of Community

Discussion of Recommendations

39 T A S K ROLES & RESPONSIBILITY LMHY5 VXGC7 VMSZ3 TZPS2 QTWF7

8.0 REFERENCES 40

41

The Necessity of Urban Green Space for Children’s Optimal Development

42

9.0

43

APPENDIX

APPENDIX 1 - HUDU’s rapid HIA tool on social cohesion and inclusive design (NHS, 2022)

APPENDIX 2 - Addressing the assessment criteria of social cohesion and inclusive design from the HUDU rapid HIA tool in Miro

44

VXGC7 BENV0056 HEALTH AND WELLBEING IN CITIES: THEORY AND PRACTICE HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENT 06 MAY 2022

F I G U R E S

F I G U R E S