POTENCJALNE NARRACJE

POTENTIAL NARRATIVES

Jean-Samuel N’Sengi Tomasz Saciłowski

My experience makes me see the reality of the people I meet differently is a title of the interview with Yulia Krivich opening this publication. Throughout her work the artist and activist brings together documentary and artistic photography as well as merges political themes with personal narratives. Krivich’s decolonial take on interdependence of the art field and geopolitics becomes an important commentary on agency in the context of the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine. —8

POTENCJALNE

NARRACJE

POTENTIAL

NARRATIVES

The body of an artist and other bodies. Notes on photograph ic-performative incarnations by Jean-Samuel N’Sengi is an essay discussing the oeuvre of Belgian artist who engages the other artists into joint collaborative work, using references from the iconic works from art history from decades ago, including visual self expression and introspection. 14

Tomasz Saciłowski experiments with the partially used and half-damaged photographic foils, on which he puts his laser drawings. Saciłowski uses diverse materials and techniques of analog photography, often referring to nature and recycling of the half-damaged photo-and-graphic resources or film tapes. Saciłowski continuously deconstructs the aesthetics with which he is associated. In an interview he claims: Ihave an affectionate attitude towards my works. Saciłowski showcases an environmental work and talks about the open-air gallery JIL he creates. 21

The exhibition features some of the projects that use the medium of photography in various ways, introducing seemingly distant approaches to taking pictures — from experiments in the darkroom, through observation and documentation of nature, to post-art or performance-for-camera.

POTENTIAL NARRATIVES

is also a platform for text, podcast and discussion touching upon the issues of developing photos and their manipulation, as well as shaping our ideas about reality throughout the photographic frames.

Yulia Krivich, from the

In her practice Yulia Krivich (b. 1988) brings together documentary and artistic photography as well as merges political themes with personal narratives. Krivich’s decolonial take on interdependence of the art field and geopolitics in the context of the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine in conjunction with the artist’s involvement into projects developed collectively aimed at updating notions of Eastern Europe, become an im portant commentary on agency in times of overlapping crises.

Tomasz Saciłowski (born 1972) showca ses an environmental work composed of multi-colored drawings made in darkness with a laser on transparent foils used in advertising. In order to create his photo grams, Saciłowski uses diverse materials and techniques of analog photography, often referring to nature and recycling of the half-damaged photo-and-graphic resour ces or film tapes. Saciłowski continuously deconstructs the aesthetics with which he is associated.

By using photography, video and performance, Jean-Samuel N’Sengi (born 1994) evokes artistic-and-historical references and incorporates personal themes into his work, creating vibrant and tense images. N’Sengi combines visual self-expression and introspection, as well as balances between the present and the past, exploring relationships with his own body and the bodies invited to joint performative projects and choreographies. Brussels-based artist situates himself in the body of the ‘other’, incarnating multiple identities to visualize notions of queer subjectivity and subversion.

[previous page]

Jean-Samuel N’Sengi, from “In conversation with” series, in cooperation with Laetitia Bica, 2022

[previous page]

Jean-Samuel N’Sengi, from “In conversation with” series, in cooperation with Laetitia Bica, 2022

My experience makes me people I meet different

Romuald Demidenko: Your practice is situated between photography and post-art. The projects you have realised relate to various issues such as visibility of the Ukra inian diaspora in Poland. How would you describe what you do?

Yulia Krivich: I started doing photography, but I have also been interested in colonial discourse and the issues related to Eastern Europe for a long time. The collective-based practices resonate with me more and more. The last two years, together with Yuriy Biley and Vera Zalutskaya, we have been creating the ZA*Grupa, now we are working with a large team at the Solidary Community Center “Słonecznik” by the Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw. Throughout the last several years, photography has ceased to be the only medium that I use in my work. The crucial moment was the project In Ukraine, which I carried out in 2019. And I felt that this was what I would like to do. I realised that I didn’t want to be isolated in the field of photography exclusi vely, but rather broaden my activity by participating in social activities and collaborating with other artists. Although photo graphy is a utilitarian and much more accessible medium than painting, it has its social dimension as it can be read by almost everyone at different levels of “preparation”. It is interesting what it has become these days — a memory, a note, a message that we send to others instead of text. It is difficult to imagine media outlets without photography. None of the texts about the massacre in Bucha, Ukraine “sounded” in the same way as the photos did. Photography can also turn out to be a deceitful medium as many people believe in its documentary character and in its objectivity. It is a medium that will stay in use for a long time and will also change along with technology. Now we can witness photography becoming more, and probably more than video, a medium of manipulation. Photos are easier to be edited and modified in terms of meaning, and depending on the context in which they are presented.

me see the reality of the

tly

Yulia Krivich

RD: Let us come back to what you refer to as a crucial moment. You went out into the street with a white flag with blue inscription saying “W Ukrainie” [In Ukraine] to suggest a less popular prepo sition to be used. The photo that documents it, has become viral. Your slogan has inspired many people to use the Polish prepo sition “w” [in] instead of a more common “na” [on], referring not only to Ukraine, but also to other neighboring countries.

YK: I have gone through all the stages related to the realization process of this work. It started with a rebellion and emotions that grew in me. I made the work and then felt insecure when it suddenly turned out that I was becoming more of a public figure. There was a responsibility and I did not feel fully prepared for it. Now, after some time has passed, it turns out that this gesture achieved its goal. I was glad when in July this year the Polish Language Council published a statement encouraging the use of “w Ukrainie” [in Ukraine] and “do Ukrainy” [to Ukraine]. It made me realize that doing something actually makes sense, although there is still a lot to be done. Recently, I heard from a young artist that the Polish-Ukrainian relations were feudal, not colonial. I was surprised that a person who deals with art can express an opinion on history in such a self-confident manner. In fact, this topic has never been thoroughly researched. According to Ukrainian and Polish historians who raised this issue, there is no clear position, but I have heard from some theoreticians, including Timothy Sny der of Yale to describe Polish-Ukrainian relations as colonial.

RD: Can you tell me about your experiences related to learning Polish in this context?

YK: I am a migrant. Before I came to Poland, I was a completely different person in terms of my social background, status, and sense of security. Having said that, on a personal level I had a feeling of injustice, if I may call it that way. At the same time, I wanted to learn and use Polish. I noticed that while I was referring to Ukraine, I had to switch and use the preposition “na” [on] as if I were talking about a country on an island or a region. When I asked why, I was told that it was used only that way. From today’s perspective, I can see that my first years in Poland were about breaking my identity. This was the moment when I stopped “being myself”. I tried to speak without an accent, not to be treated in a biased way and hear: You don't even sound like

Yulia Krivich Protest Action or Frozen water on tree, from “Przeczucie” series, 2013 (detail)

Yulia Krivich Protest Action or Frozen water on tree, from “Przeczucie” series, 2013 (detail)

someone coming from Ukraine. I accepted it to assimilate, but later realized it wasn’t quite okay. My experience makes me see the reality of the people I meet differently and project my migrant gaze on them. Therefore, assimilation seems to me to be wrong. It is integration that relies on the work of both sides. And I was glad when people working at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw intended to learn Ukrainian in order to say something in that language. For me it was a small but big step. Certainly, this was an exceptional situation — the war and a large number of refugees from Ukraine suddenly appeared in front of a museum, in Pańska Street. Warsaw is also geographically close, for obvious reasons there are more people here who come from neighboring countries, so it would be appropriate to be able to say “good morning” in Ukrainian just like we tend to say it in English.

RD: Art cannot stop the war but we can use our visibility and thus provoke gestures that oppose violence and take the side of those forced to flee. You co-create with Taras Gembik, Maria Beburia and others, the Solidary Community Center “Słonecz nik” at the Warsaw’s Museum of Modern Art in Pańska Street, which has been operating since February. It is one of the few regularly functioning support platforms of this kind in the city, organized by an art institution. How was this place created?

YK: The basis for the creation of “Słonecznik” [Sunflower] was the Blyzkist collective, co-created by Taras Gembik and Maria Beburia. There was a need to increase the accessibility of the museum to members of the Ukrainian and migrant communities, including Belarusians and those of other nations. I have known well for a long time curators from the museum such as Sebastian Cichocki and Natalia Sielewicz, and also Kaja Kusztra, Kuba Depczyński and Bogna Stefańska from their project called Department of Presence. The idea came quite spontaneously at the end of February. You remember how it felt for all of us. At the beginning, together with the Consor tium of Postartistic Practices, we prepared banners for one of the protests against the war at the museum in Pańska Street, and upon our return we left the banners in the museum. We had a need to be somewhere and do something. The museum in Pańska is close to the Central Station, where a number of visitors ended up. This lo cation facilitated the transport of medicines and hot meals to support centers where newcomers were sent. In the beginning, the “Sunflower” operated as a first aid post. Later, there was a need for workshops and psychological support. Then people started to arrange the paperwork, so they needed photos. There was a need to leave the children under care and organize workshops for them, so that their parents could find work and accommodation during the day. I call the current stage educational — we organize events on history and culture, and each one is different. For example, one of the last events was Maria Vorotilina’s lecture and workshop titled Imagining Eastern Europe which dealt with notions coined by the West, such as the New East, expressing the more accurate need to redefine a new Europe.

RD: For several years you have been living near Haller Square. You observe this place on a daily basis. The first time we met here, you mentioned that it has changed in recent months.

YK: The Multicultural Center, which was established a few years ago, serves as a center for aid serving the people from Ukraine. It has been a year by now since Pracownia Wschodnia started operating in the area, becoming an important venue for local artists. Recently, the Ukrainian and Russian languages have been heard over here. The square is teeming with life day and night. I am afraid of gentrification, which to a large extent has not happened yet, and I hope it will not take place, be cause we’re more aware today how certain processes work. There are many people who have lived here all their lives — often older people. There are only two rental apartments in my stairwell. In general, people know each other very well, they know who is who and what certain people did in previous years. When I moved here in 2016, I noticed that it is a different, non-hipster neighborhood. I missed friends who lived in other parts of the city where there were places to go. However, Trzy Kruki café soon appeared to fill the gap. And now there’s a bit of everything. There is still a so-called prażka and element that is not on the square itself, but I see it in the evening near Żabka in Dąbrowszczaków Street. I like local class diversity as far as I can say. There are people in a homeless crisis. There are younger and older people. I have a neighbor living on the ground floor who suffers from dementia and hardly le aves the house. During the lockdown period, when no one came to her place, I would bring her groceries and go for walks together.

RD: Please tell us about the work you’re going to show.

YK: I would like to meet people who live, stay or work near the square. I intend to do this with the medium of photos, but also to reverse the roles and ask my neighbors or strangers to take a photo of me. I am very curious how people will react to this idea. I wish more people would discover that there is such a place as Pracownia Wschodnia. I would like to add that Plac Hallera is my second home and the first place in my life in Poland, where I feel “at home”. In my hometown, I lived near the central station, where people from different regions would arrive. At the same time, it was a spot where many people seemed to know each other by si ght and I have a feeling that it is similar here. Even the architectu re reminds me of the place where I grew up. The buildings, which are called Stalinka, were part of a modernist housing estate, where there are quite luxurious — as for the communist period — apartments with ceilings over three meters high. In later years, panel blocks of large slabs were erected to accommodate more people in relatively small apartments of a lower standard. These were Khrushchyovkas — named after Nikita Khrushchev, who abolished the directive according to which people from the countryside were not allowed to move to the cities .

The body of an artist and on photographic-performative Jean-Samuel N’Sengi

What we need to know is that queerness is not yet here but it approaches like a crashing wave of potentiality. And we must give in to its propulsion — a com mand by José Esteban Muñoz that although articulated over a decade ago seems all the more valid today1 .

I’m quoting these words by a Cuban theoretician as a potential correspondence with works by Brussels-based artist Jean-Samuel N’Sengi, that seem to be suspended between the past and the present. N’Sengi seeks to discover his own visual language informed by introspection, invites other artists to collaborate, and brings into focus iconic artworks created decades ago.

In one of the films posted on Instagram, N’Sengi puts white paint on his face. In this way he reperforms a series of 10-minute-long videos Art Make-Up by Bruce Nauman made between 1967 and 1968, in which Nauman puts white (and also pink, green, and black in the subsequent versions of the work) paint on his face and the upper torso to raise, symbolically, whate ver social connections it had with skin color2, as he mentions in a conversation several years after he created this seminal work. This, as well as Nauman’s self-portraits created around the same period — such as Flesh to White to Black to Flesh, in which he put layers of white and black pigment onto his torso, arms and face — seem to serve as a reference for N’Sengi, but they also seem to provoke him to articulate a daring visual response to them. These should not be seen as a reenactment but instead, as overwhelmingly personal work. N’Sengi addresses the problematic reading of contemporary art history, that used to (and presumably still tends to) struggle to reflect the Other. A white mask appears in another Instagram post by N’Sengi. He brings it close to his face in a theatrical manner. Noszona jako przebranie, dla roz rywki lub straszenia innych , Worn as a disguise, or to amuse or frighten other people, as he captions.

and other bodies. Notes photographic-performative incarnations by

Romuald Demidenko

It started from taking pictures when Jean-Samuel N’Sengi was studying photography at the Arba-Esa Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels. He concluded these formative years by assem bling portraits of his friends and coevals, in a self-published photobook As usual (2018). This title can be interpreted as the everyday action of « taking » photographs or the mundane digital practice through the devices we hold close to our bodies. These personal image banks might never be disseminated or looked at again. Likewise, not all work by N’Sengi can be easily found as he shares them through ephemeral platforms such as stories on Instagram or posts that are later deleted. This may serve as an explanation as to why quite an overwhelming collection of Photo Booth snapshots and videos ought to rather be treated as artistic research. This also applies to a vast selection of, largely unseen, stories created between 2014 and 2018, Damu Yangu, Mutoto Yangu [Swahili for “My blood, my child”] — a reference to a conversation with the artist’s mother living away from Brussels, concerned about her only son, ending one of their encounters with a line You can hide yourself from me but you won’t be able to hide from yourself . In the series we see the artist in various settings, sitting and sharing his thoughts, chanting or dancing on his own or with his friends, with wig or makeup on, assuming dif ferent incarnations. This composition including a sort of personal choreography is also evident in another series Babysamekh, also referred to as Loneliness of Babysamekh, and for the most part kept as a private archive.

Alongside the snapshots and staged photographs created during his studies, the ongoing self—portrait series Initiation of Esther is especially worth mentioning. In one of them, a closeup photo graph, the eponymous mother-femme figure appears in a white wig and her fringe almost covers the portrayed model’s eyes entirely. In another black-and-white image, he poses wearing a white gown, holding two horns behind the head. In a recent conversation N’Sengi revealed to me that the series is a way of exploring the personal narratives connected to his mother with whom he feels an utmost bond. By weaving around and embodying her experiences, he ultimately admits the disconnect

between some members of their family when he decided to come out, remembering specifically an aunt who said she would pray for him. Being queer is choosing the devil. So I did, he adds.

Jean-Samuel N’Sengi is a protagonist to his own works but often includes others. As he takes from the medium of photography to roam more dynamic and time-based formats, which ultimately take the form of interactive works that test potential dia logues with works by artists from the past. Right before Kanal — Centre Pompidou in Brussels was closed to the public for the renovation procedure in spring 2021, the artist used this occasion to initiate a live performance as an extension of his ongoing photographic series Lipstick phase in one of the future museum’s rooms. This invita tion and collaboration with others — on this occasion with art-related peers from his circle3 . Seduction and violence have a lot in common , as N’Sengi stated in one of our conversations. In fact his series commenced as a semi-staged photographic cycle echoing the Glass on Body Imprints from 1972 by Ana Mendieta. A Cuban -born artist was known for her use of unconventional materials, used soil as medium for her sculptural works to approach themes of rape, femicide and hidden acts of domestic violence. By using blood she also referenced the language of religions in African and Afro-Cuban communities, among others, as Muñoz suggests in his other text, fully dedicated to her. He began his essay with the question Where is Ana Mendieta? , quoting a slogan held by hundreds of protesters in front of the Guggenheim Museum in 1992, after the puzzling Mendieta’s death, in an apartment shared with her partner and minimalist sculptor, Carl Andre4 .

Considering the other artists in relation to N’Sengi works, I am thinking of the work of Adrian Piper. Through her photo collages, texts and posters, she addressed various accounts of otherness she experienced over years by ‘acting like a man’ while creating a figure referred to as Mythic being whom she started performing as in 1973. Finally, I cannot overlook the on-camera performances by Natalia LL: Consumer Art (1972–1975) and its extension, Postconsumer Art (1975). De spite being created decades ago these works remain influential in terms of the deconstruction of the portrait Another intere sting aspect relevant here is the way she would work with the models, which reminds us so much of the work by N’Sengi.

Tophotograph is to appropriate the thing photographed , as Susan Sontag implies in her seminal essay On Photography, suggesting later on how cameras and weapons have a lot to do with one another5. N’Sengi admits that his work revolves around positions of the viewer, power relations and furthermore, his personal references. He acknowledges that a vast part of his work is informed by looking at photography and performance art by iconic and for the most part Western white artists. N’Sengi continuously allows himself to experiment, juggling between his incarnations with ease and playing with different aesthetics or formats he seems to be interested in working with — staying “frivolous, promiscuous, and irrelevant”6 .

Throughout the photographs, collages, videos and collaborative acts, N’Sengi positions himself in the body of the Other as a way to find one’s own visual expression to touch upon notions of inti macy and political entanglements. Many examples of his oeuvre resonate with or directly connect to works or gestures manifested by different artists, often deriving from the past and exploring ways in which their body could serve as a medium to touch upon certain issues and concerns. Trying to describe, as well as look, at N’Sengi’s work challenges the viewer and demands responding to questions about the position we are looking from. Who is uncomfortable? Who is apologising? Who is doing the work?7

Jean-Samuel N’Sengi, from “In conversation with”series, in cooperation with Laetitia Bica, 2022

Jean-Samuel N’Sengi, from “In conversation with”series, in cooperation with Laetitia Bica, 2022

Jean-Samuel N’Sengi, from “Lipstick Phase” series, 2018 (detail)

[1] José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia. The Then and There of Queer Futurity, Conc lusion: “Take ecstasy with me”, 2009, p. 185. [2] Oral history interview with Bruce Nauman, 1980 May 27—30. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. [3] The artist mentions names of those he worked with for this occasion: Nina Fafchamps, Charlotte Guerlus, Cléa Massun, Alexis Monier, Indigo Canullo Stefanelli. [4] José Esteban Muñoz (2011), Vitalism’s af ter-burn: The sense of Ana Mendieta, Women & Performance: a jour nal of feminist theory, 21:2, pp. 191—198, 2011. [5] Susan Sontag, On Photography, New York: Anchor Books, 1990, p. 4. [6] “Being taken seriously means missing out on the chance to be frivolous, promiscuous, and irrelevant”, J. Jack Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure, 2011, p. 6. [7] Susan Pui San Lok, Decolonizing Art History, “Decolonizing Art History. Art History ” , 2020 #43.

Tomasz Saciłowski

I have an affectionate my works

Romuald Demidenko: How would you define your practice?

Tomasz Saciłowski: I see myself as someone who initiates the process of creating an image, the final effect of which arises spontaneously. Sometimes I also see myself as an inventor or collector of pictures and their concepts. I am interested in the possibility of doing something completely new within a certain medium. I feel close to the tradition of working with photography in the spirit of avant-garde, modernism and conceptual art. Historically, there have been many amateur artists who have worked on developing new photographic techniques and creating quasi-painterly works.

RD: Some of your works are in the collection of the Cracow’s Museum of Photography and it’s this medium that you are mainly associated with. However, you work across various techniques, you often use found images and also curate exhibitions every now and then.

TS: In the last decade I have focused on photography, but my body of work includes performance-related work as well as publishing, music and curatorial projects. In the past, I used to take a lot of photos of various sorts of objects and by making this I created a series to be presented as slide shows. Over time I lost my interest in compulsive photography and now I focus only on the material side of the work, its color, light and texture. I work with light and observe how it penetrates and illuminates specific materials. I have an ambiguous attitude to the photography itself. For example, it’s hard for me to figure out the motivation and purpose of taking pictures of landsca pes or capturing views.

RD: Our conversation takes place on occasion of the exhibition in which we will see some of the most recent works you created. You use the type of transparent foil designated to produce back lit images. Then you irradiate it with a laser and, as a result of experimenting in darkness, you create patterns that may resemble handwriting. Since when have you been working on this series?

nate attitude towards

TS: I started working on this series last year, when I finally managed to organize a suitable work space. I haven’t developed any systematic sign language, so you cannot really name it handwriting. I prefer to call what I do a “scribble” or a scum. Scum, or in Polish bohomaz, has an interesting etymology: this word in East Slavic languages meant an icon painter. Translating it into Polish realms, the use of s c u m in Polish next to “scribble”, has a strong connection with the disdainful attitude towards art from beyond the Eastern border. For me, a pattern or a dra wing are of lesser importance. I am mainly concerned with exposure and the play of light. I like to play with it. Playing with a laser is quite innocent, it’s even childish, like letting go and catching a bunny, as we describe playing with a mir ror and light. Sometimes it’s also about playing with afterimages. In darkness, the laser has a strong influence on the retina of the eye, which allows us to “remember” patterns. Other times, patterns are created through the music that has always been important to me. I used to often listen to orchestral music alone at home, nodding my head and waving my arms. I tried to record my own music and vocal productions, to which I would love to come back. Sometimes I imagine myself as a conductor “painting” with a laser something like a score.

RD: And how did you commence working with the lasers?

TS: It has been a long time since I used a transparent photosen sitive film for the first time. They were used in machines where a digital file was processed and irradiated with red, green and blue lasers. The “material” image was created as a result of mixing these three light sources. Unfortunately, these machines are practically no longer in use. The technique is being replaced by cheaper inkjet printing. Some materials have remained and are still available on the market. I try to acquire them and, replacing the machine, I use a laser and light myself. I have good memories with lasers. They also have a number of new industrial uses.

RD: Your studio is located in the middle of Warsaw but you live near Haller Square. What kind of relationship do you establish with your surroundings?

TS: I must admit that I am not always positively influenced by the local social fabric and I rather distance myself from the surroundings. But to point out some of its po sitive features: local kids listen to cool music, feel at ease and run around the street without anyone’s supervision. Such freedom is hard to see in other parts of the city. I like how new hip-hop can be heard from under my windows. I have a balcony with a beautiful axis view, which I love. Immediately after my move to Praga, even before the war broke out in Ukraine, I would hear the eastern languages and I appreciated it a lot. To get more of it, I used to go to the Orthodox church on Sundays after mass. To spend time with people and the icons.

RD: You occasionally work as curator of an outdoor gallery named “JIL”. The exhibition space is composed of a two-sided concrete wall, standing next to the building in which you live. On prefabricated elements such as this one, posters were displayed in several dozen Warsaw locations. That being said, you have restored the exhibition-making potential of the concrete wall.

TS: This gray advertising wall standing directly under my apartment caught my eye. For the average viewer it would be a rather inconspicuous spatial element, on which most people would likely stumble upon and not notice. The thin walls and the raw ness of the material itself impressed me. I was fascinated by the shape, which is why I named it “JIL”. I treat it more as a found object. The shape of its base is also asso ciated with the form of my works, which hang freely at exhibitions, slightly roll at the bottom and, when viewed from the side, take a form similar to the letters “J” or “L”. I deliberately roll more some of the exposures and prints.

RD: How do your neighbors react to JIL?

TS: The exhibitions at JIL have been commented on by my neighbors and these opinions were nothing worth quoting. It even happened that some works were intentional ly destroyed. Perhaps the art projects that were presented there were not suitable for the wider public, however it was not of great importance to me, since I organized the exhibitions for myself and a group of friends to a large extent. I am interested in adopting different places for exhibitions with great ar tists. I have implemented several bottom-up projects carried out by me outside the institutions.

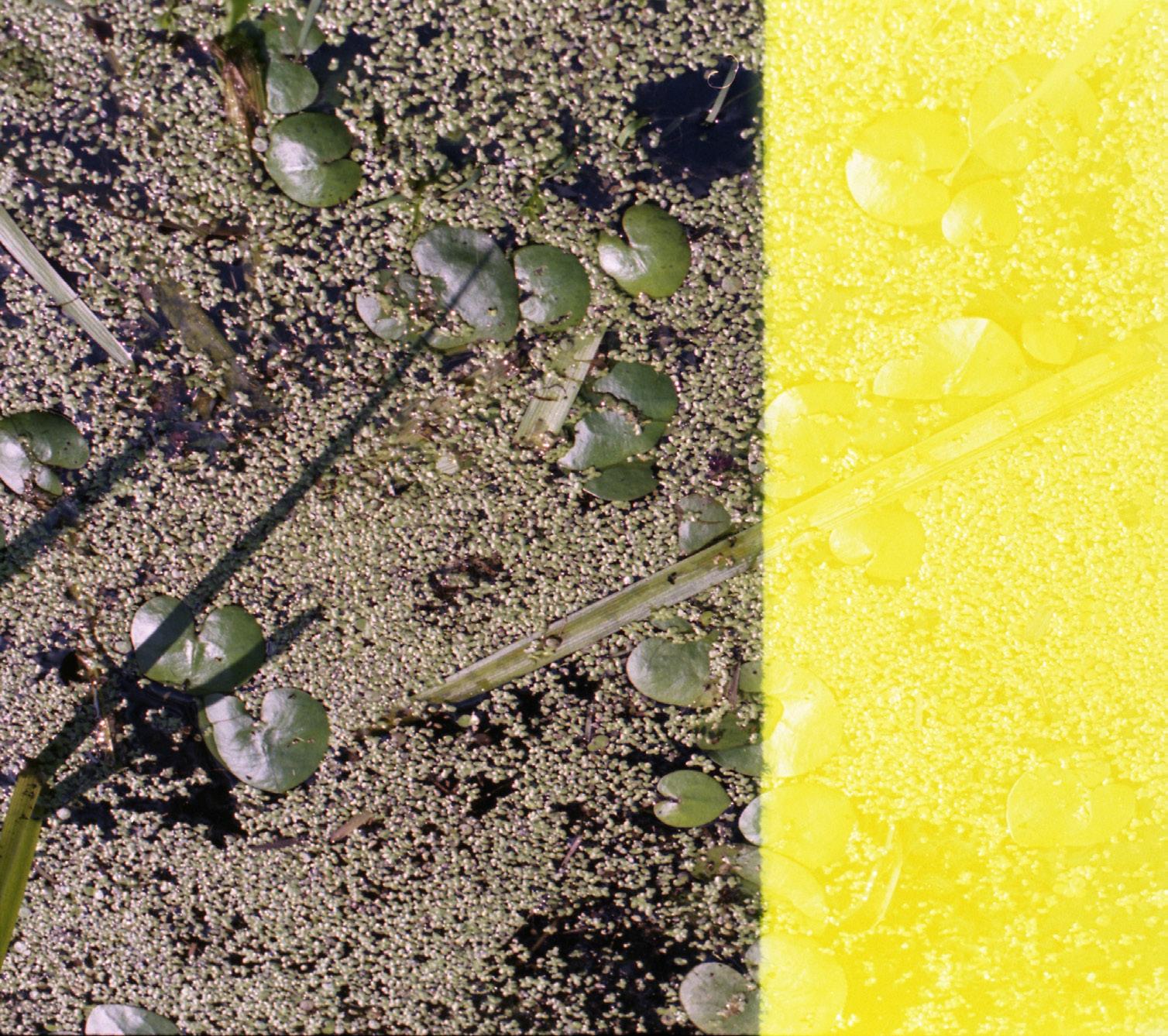

RD: You post quite a number of moving images on Instagram. In some of the videos you dip the photographic material in water. Can you describe more accurately what you’re into?

TS: I rarely or hardly ever post my photographic works on Insta gram. Instead, my IG profile mainly includes videos that I record near the water. This is where I recently take my prints with me, which I additionally rinse in a lake or river. Rinsing is the last step in the photo development process. I noticed that rinsing can be repeated many times. I have an affectionate attitude towards my works. I am attached to them and I treat them as if they were my pupils who need to be “taken for a walk”. The smell of chemicals and a claustrophobic darkroom do not serve them well at all. I feel that they need contact with nature, and water favors them. Water, sun and sky also allow me to observe and film interesting light effects on the surface of photographic works .

Tomasz Saciłowski,

Tomasz Saciłowski,

Tomasz Saciłowski, from “D-sub paint” series, 2015, (detail)

Tomasz Saciłowski, from “D-sub paint” series, 2015, (detail)

2018

Jean-Samuel N’Sengi, from “ Esther ”series

The publication accompanies the exhibition POTENTIAL NARRATIVES — Yulia Krivich, Jean-Samuel N’Sengi, Tomasz Saciłowski Pracownia Wschodnia 19.10—6.11.2022 | Trzy Kruki & JIL 19.10—22.12.2022 Curated by: Romuald Demidenko

linktr.ee/potencjalnenarracje

Texts: Romuald Demidenko, Yulia Krivich, Tomasz Saciłowski Translations and proofreading: Romuald Demidenko Proofreading of the text The body of an artist and other bodies.Notes on photographic- performative incarnations by Jean-Samuel N’Sengi: Samantha Lippett Graphic design: Mikołaj Konrad Grabowski

Acknowledgements: Yulia Krivich, Tomasz Saciłowski, Jean-Samuel N’Sengi (Laetitia Bica, Samantha Lippett), Mikołaj Konrad Grabowski, Kamil Malinowski, Pracownia Wschodnia [Mikołaj Chylak, Janek Cieślak, Tomek Melissa, Paulina Mirowska, Jędrzej Owsiński, Agnieszka Wach, Błażej Worsztynowicz, Łukasz Zembaty].

© 2022 Romuald Demidenko, Yulia Krivich, Jean-Samuel N’Sengi, Tomasz Saciłowski