M astering the M achine

Also in this Issue: 70 Y ears as the s tandard : a W orld F amous a nniversarY t he o rigins o F the n av Y ’ s n e W C od a ir C ra F t , the C mv-22B o spre Y F oundation F or the F uture , t odaY t he n ext g eneration – e m B raC ing t e C hnolog Y to e xpand on the t ried and t rue Winter 2023 Number 159

Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey: The World’s Most Versatile Aircraft

The development of new technology is central to the integration and transformation of military operations. The most versatile and game-changing technologies have enabled operators to complete more tasks with less resources. Examples throughout history such as improvements in the speed and range of vehicles, production improvements, or the innovation of new ideas to solve previously unsolvable problems, prove that technology has radically shaped national defense strategies.

The V-22 Osprey is one such example of revolutionary technology. The Osprey combines the vertical takeoff, hover, and landing qualities of a helicopter with the long-range, fuel efficiency, and speed characteristics of a turboprop aircraft.

The Osprey’s multi-mission advantage across a full range of military operations improves mission efficiency and reduces logistics with a demonstrated legacy of mission success over its 30 years of operation.

Initially developed as an aircraft for the United States Marine Corps to conduct combat and assault support, the Osprey can conduct diverse missions throughout the world’s most demanding operating environments. “The Osprey represents Bell Boeing’s incredible ability to reimagine the experience of flight and disrupt an entire industry,” said Kurt Fuller, Bell V-22 Vice President and Bell Boeing Program Director. Over time, additional service branches added the V-22 to their aircraft fleet with specific modifications to suit the needs of their forces. Today, the Osprey supports the Marines Corps, Air Force, Navy, and the Japan Ground Self Defense Force as the first international customer. With a fleet of over 400+ aircraft accumulating more than 700,000 flight hours, the Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey enhances versatility and interoperability throughout the world.

The MV-22 Osprey allows Marines to quickly deploy troops, equipment, and supplies from ships and land bases with the speed, range, and versatility not previously possible by any single platform. The Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC) CV-22’s primary mission is to conduct long-range infiltration, exfiltration, and resupply missions for Air Commandos worldwide at a moment’s notice. The CMV-22B, the program’s most recent variant conducts fleet logistics, or carrier onboard delivery (COD) with significant increases in capability and operational flexibility.

“The V-22 will be around for a long time, and we expect it will continue to evolve to meet the needs of the Department of Defense,” added Fuller. As the needs of the military continue to evolve, so too does the Osprey in a way only a tiltrotor can.

Winter 2023 ISSUE 159

About the cover: MH-60R Sea Hawk helicopter attached to the 'Vipers" of HSM 48 during preflight preparations aboard the guided-missile cruiser USS Anzio (CG 68)

Rotor Review (ISSN: 1085-9683)

is published quarterly by the Naval Helicopter Association, Inc. (NHA), a California nonprofit 501(c)(6) corporation. NHA is located in Building 654, Rogers Road, NASNI, San Diego, CA 92135. Views expressed in Rotor Review are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the policies of NHA or United States Navy, Marine Corps, or Coast Guard. Rotor Review is printed in the USA. Periodical rate postage is paid at San Diego, CA. Subscription to Rotor Review is included in the NHA or corporate membership fee. A current corporation annual report, prepared in accordance with Section 8321 of the California Corporation Code, is available on the NHA Website at www.navalhelicopterassn.org.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Naval Helicopter Association, P.O. Box 180578, Coronado, CA 92178-0578.

Rotor Review supports the goals of the association, provides a forum for discussion and exchange of information on topics of interest to the rotary force and keeps membership informed of NHA activities. As necessary, the President of NHA will provide guidance to the Rotor Review Editorial Board to ensure Rotor Review content continues to support this statement of policy as the Naval Helicopter Association adjusts to the expanding and evolving Rotary Wing and Tilt Rotor Communities .

FOCUS: Mastering the Machine

Mastering the Machine: “Gradually, then Suddenly"................................................................28

By CAPT Sandy Clark, USN (Ret.)

Human Factors in the Cockpit: It’s All of Our Problem........................................................30

By LCDR Eric “Pennies” Page, USN

ADTS and Moving Map Capabilities in the Personnel Recovery (PR) Environment.......33

By LT Joe “WORM” Rodgers, USN

Turning Shadow to Light: Empowering Grassroots Navy Software Development..........34

By LCDR Cory Poudrier, USN

“It’s Not the Plane, It’s the Pilot, Mav”.......................................................................................38

By LT Nick "SEGA" Padleckas, USN

Foundation for the Future,Today.................................................................................................40

By LT Zach “PuK” Pennington, USN

Increased Firepower Provides Unique Capability for Combat Rescue..............................42 From 920th Rescue Wing Public Affairs

HSC’s Double Bubble Trouble.....................................................................................................44

By LT I.M. “Fridge” Grover, USN

FLY-IN 2022

Return to Basics..................................................................................................................................26.

By LT Daniel “Roadkill” Lloyd, USN

The Fleet Fly-In and NHA Events - a Trustee's POV.................................................................27

By CAPT Sandy Clark, USN (Ret.)

FEATURES

The Origins of the Navy’s New COD Aircraft, the CMV-22B Osprey...............................46

By CDR John C. Ball, USN (Ret,)

Fisher House - A Sailor’s Home Away from Home................................................................52

By CAPT Bob Rutherford, USN (Ret.)

Rotary Wing Aviation—A Family Tradition...............................................................................54

By CDR Dave “Brisket” Kiser, USN

Joint Integration Abroad in Japan..................................................................................................55

By LT Ruthvik “Marbles” Kumar. USN

The Ten Commandments of being an Executive Assistant (EA)............................................56

By CAPT John Coyne, USN (Ret.)

Rotor Review Editors Emeriti

Wayne Jensen - John Ball - John Driver - Sean Laughlin - Andy Quiett Mike Curtis - Susan Fink

Bill Chase - Tracey Keefe - Maureen Palmerino - Bryan Buljat - Gabe Soltero

Todd Vorenkamp - Steve Bury - Clay Shane - Kristin Ohleger - Scott LippincottAllison Fletcher Ash Preston - Emily Lapp - Mallory Decker- - Caleb Levee

Shane Brenner - Shelby Gillis - Michael Short

Rotor Review #159 Winter '23 2

COLUMNS

The Next Generation – Embracing Technology to Expand on the Tried and True

By

CAPT

Jade Lepke, USN

Report from the Rising Sun..................................................................................................22

Individuality in the Uniformed Service: Breaking the Cycle of Hypervigilance

By LCDR Rob “OG” Swain, USN (CVW-5)

View from the Labs ...............................................................................................................24

By CAPT George Galdorisi, USN (Ret.)

DEPARTMENTS

Industry and Technology

The Differential Advantage of the CMV-22B.....................................................................58

By CAPT Christopher “chet” Misner, USN (Ret.)

Leonardo Subsidiary AgustaWestland to Exercise Option for the Production and Delivery of 26 TH-73A Thrasher Lot IV Training Helicopters......................................59 Leonardo Press Release

Editorial Staff

EDITOR -IN - CHIEF

LT Annie "Frizzle" Cutchen, USN annie.cutchen@gmail.com

MANAGING EDITOR

Allyson "Clown" Darroch rotorreview@navalhelicopterassn.org

COPY EDITORS

CDR John Ball, USN (Ret.) helopapa71@gmail.com

CAPT John Driver, USN (Ret.) jjdriver51@gmail.com

LT Elisha "Grudge" Clark, USN elishasuziclark@gmail.com

AIRCREW EDITOR

AWR1 Ronald "Scrappy" Pierpoint, USN pierpoint.ronald@gmail.com

COMMUNITY EDITORS

HM

LT Molly "Deuce" Burns, USN mkburns16@gmail.com

HSC

LT John “GID’R” Dunne, USN john.dunne05@gmail.com

LT Tyler "Benji" Benner, USN tbenner92@gmail.com

LT Andrew "Gonzo" Gregory, USN andrew.l.gregory92@gmail.com

Helo History

CAPT JoEllen Drag-Oslund: Female Naval Aviator and Trailblazer................................64

“It’s because of her that we are here”

By LT Audrey “Pam” Petersen,

Squadron Updates

USN

World Famous Vanguard of HM-14 Fly Final Flight..........................................................66

By CDR Nicklaus Smith, USN

70 Years as the Standard: a World Famous Anniversary..................................................68

By LT Alex “CRItR” Hosko, USN

HT-28 Hellions Reinvigorate Military Partnerships..........................................................69

By John Richards

Off Duty....................................................................................................................................70

Book Review: The Dream Machine by Richard Whittle

Movie Review: Desert One

Reviewed by LCDR Chip Lancaster, USN (Ret.) Radio

LT Fred "Prius" Shaak, USN fshaak@gmail.com

HSM

LT Joshua "Hotdog" Holsey, USN josholc@gmail.com

LT Johnattan "Snow" Gonzalez, USN johnattang334@gmail.com

LT Thomas "Buffer" Marryott Jr, USN tmarryott@gmail.com

LT Nathan "MAM" Beatty, USN nathan.g.beatty@gmail.com

LT Jared "Dogbeers" Jackson, USN jared.d.jack@gmail.com

USMC EDITOR

Maj. Nolan "Lean Bean" Vihlen, USMC nolan.vihlen@gmail.com

USCG EDITOR

LT Marco Tinari, USCG marco.m.tinari@uscg.mil

TECHNICAL ADVISOR

LCDR Chip Lancaster, USN (Ret.) chipplug@hotmail.com

©2023 Naval Helicopter Association, Inc., all rights reserved

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 3

.......................................................................................................................6 Executive Director's View.........................................................................................................7

President of Membership Report.................................................................................8 National President's Message................................................................................................10

the Editor-in-Chief........................................................................................................12

Fund Update ......................................................................................................14

Society.....................................................................................................................16

Chairman’s Brief

Vice

From

Scholarship

Historical

Commodore's Corner...........................................................................................................20

...........................................................................................................60

Change of Command

....................................................................................................................61

Region Updates

Rotors....................................................................................................................74

.........................................................................................................................78

Check ....................................................................................................73 Engaging

Signal Charlie

Thank You to Our Corporate Members - Your Support Keeps Our Rotors Turning

To get the latest information from our Corporate Members, just click on their logos.

Gold Supporter

executive patronS

Rotor Review #159 Winter '23 4

Small BuSineSS partnerS platinum SupporterS

Naval Helicopter Association, Inc.

P.O. Box 180578, Coronado, CA 92178-0578

(619) 435-7139 www.navalhelicopterassn.org

National Officers

President....................................CDR Emily Stellpflug, USN

Vice President ........................................CDR Eli Owre, USN

Executive Director...............CAPT Jim Gillcrist, USN (Ret.)

Business Development..............................Ms. Linda Vydra

Managing Editor, Rotor Review .......Ms. Allyson Darroch

Retired Affairs ..................CDR Mike Brattland, USN (Ret.)

Legal Advisor...............CDR George Hurley, Jr., USN (Ret.)

VP Corp. Membership..........CAPT Tres Dehay, USN (Ret.)

VP Awards.................................CDR Philip Pretzinger, USN

VP Membership ...............................LCDR James Teal, USN

VP Symposium 2023 .............................CDR Eli Owre, USN

Secretary..........................................LT Jimmy Gavidia, USN

Special Projects........................................................VACANT

NHA Branding and Gear...............LT Shaun Florance USN

Senior HSM Advisor.............AWRCM Nathan Hickey, USN

Senior HSC Advisor ......AWSCM Darren Hauptman, USN

Senior VRM Advisor........AWFCM Jose Colon-Torres, USN

Directors at Large

Chairman...............................RADM Dan Fillion, USN (Ret.)*

CAPT Gene Ager, USN (Ret.)*

CAPT Chuck Deitchman, USN (Ret.)*

CAPT Dennis DuBard, USN (Ret.)*

CAPT Tony Dzielski, USN (Ret.)*

CAPT Greg Hoffman, USN (Ret.)*

CAPT Bill Personius, USN (Ret.)*

CAPT Mario Mifsud, USN (Ret)*

CAPT Arne Nelson, USN (Ret.)*

CAPT Matt Schnappauf, USN (Ret.)*

LT Alden Marton, USN*

AWRCM Nathan Hickey, USN*

* Also serving as Scholarship Fund board members

Junior Officers Council

Nat’l Pres............................ LT Alden "CaSPR" Marton, USN

Region 1.........................LT Ryan "Shaggy" Rodriguez, USN

Region 2 .......................................LT Rob "JORTS" Platt, USN

Region 3 ....................... LT Bryan “Schmitty” Schmidt, USN

Region 4 ...................................LT Lei “REPTAR” Acuna, USN

Region 5..................LT Connor "Humpty" McKiernan, USN

Region 6....................................LT Robert "DB" Macko, USN

NHA Scholarship Fund

President .............................CAPT Arne Nelson, USN (Ret.)

Executive VP/ VP Ops ...CAPT Todd Vandegrift, USN (Ret.)

VP Plans................................................CAPT Jon Kline, USN

VP Scholarships ..............................Ms. Nancy Ruttenberg

VP Finance ...................................CDR Greg Knutson, USN

Treasurer........................................................Ms. Jen Swasey

Webmaster........................CDR Mike Brattland, USN (Ret.)

Social Media .............................................................VACANT

CFC/Special Projects ...............................................VACANT

Regional Officers

Region 1 - San Diego

Directors ......................................CAPT Chris Richard, USN

CAPT Ed Weiler, USN

CAPT Sam Bryant, USN

CAPT Nathan Rodenbarger, USN President ............................ CDR Dave Vogelgesang, USN

Region 2 - Washington D.C.

Director ........................................ CAPT Andy Berner, USN President ...........................................CDR Tony Perez, USN Co-President.................................CDR Pat Jeck, USN (Ret.)

Region 3 - Jacksonville

Director...................................CAPT Teague Laguens, USN President........................................CDR Dave Bizzarri, USN

Region 4 - Norfolk

Director...................,........................CAPT Ed Johnson, USN President ............................ CDR Santico Valenzuela, USN

Region 5 - Pensacola

Director ...........................................CAPT Jade Lepke, USN President .........................................CDR Annie Otten, USN '22 Fleet Fly-In Coordinator..LT Connor McKiernan, USN

Region 6 - OCONUS

Director .........................................CAPT Derek Brady, USN President ................................CDR Jonathan Dorsey, USN

NHA Historical Society

President............................CAPT Bill Personius, USN (Ret.)

VP/Webmaster..................CDR Mike Brattland, USN (Ret.)

Secretary................................LCDR Brian Miller, USN (Ret.)

Treasurer...........................CDR Chris Fitzgerald, USN (Ret.)

S.D. Air & Space Museum.....CAPT Jim Gillcrist, USN (Ret.)

NHAHS Committee Members

CAPT Dennis DuBard, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Mike Reber, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Arne Nelson, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Jim O’Brien, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Curtis Shaub, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Mike O’Connor, USN (Ret.)

CDR John Ball, USN (Ret.)

CDR Chris Fitzgerald, USN (Ret.)

CDR Chip Lancaster, USN (Ret.)

Master Chief Dave Crossan, USN (Ret.)

Navy Helicopter Association Founders

CDR

CDR

CDR

CDR D.J. Hayes, USN (Ret.)

CAPT C.B. Smiley, USN (Ret.)

CAPT J.M. Purtell, USN (Ret.)

CDR H.V. Pepper, USN (Ret.)

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 5

CAPT A.E. Monahan, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Mark R. Starr, USN (Ret.)

CAPT A.F. Emig, USN (Ret.)

Mr. H. Nachlin

H.F. McLinden, USN (Ret.)

W. Straight, USN (Ret.)

P.W. Nicholas, USN (Ret.)

Mastering the Machine

By RADM D.H. “Dano” Fillion, USN (Ret.)

Sea story: After I transitioned from flying the reliable and fun SH-3G to the Unbelievable SH-60B, I ran into a high school football buddy at home in Charleston, SC, Scott (my buddy) joined the Marines after college and like me, he was home on leave. We reconnected over a few beers (surprise). When he heard that I was now flying the SH-60 he asked: “So did you transition to that aircraft because it is the most technologically advanced helo in the Navy?” I thought of just saying yes because the newness and capabilities certainly did play into my decision but the most accurate answer to his question was; “Scott, I transitioned to the H-60 because after flying H-3s in Puerto Rico (my 1st squadron was VC-8, Rosey Roads), I wanted to fly an aircraft with an AIR CONDITIONER!” Stone cold fact, regardless of the reasoning, you all have as you continue to master your aircraft, as pilots, AWR/Ss, and amazing maintainers /support teams!

Going to push the metaphor button if you will let me; consider NHA as the “Machine” that all of you as members (and those of you who should be members) are mastering. NHA is only as good as the members who are willing to devote some effort to the “MACHINE.” I promise you, I/we at NHA Headquarters have not forgotten how busy you are in your professional and personal lives and when you dedicate time to NHA, it needs to have meaning, support you and your families’ efforts in the service of our country, build camaraderie/bonding/networks and be FUN! Just played in NHA Wild On Wings (WOW) Golf Tourney in Mayport, huge FUN! Everyone who participated was Mastering the Machine!

The organization that has the most interest in folks who fly, fight, maintain and support rotary wing aviation is NHA, stone cold fact! I wrote the paragraph above and have 100% tasked the NHA Board of Directors, the Trustees, all the NHA Officers, Volunteers, the NHA Headquarters Staff and the Chairman to ensure that everything NHA delivers has meaning, supports you and your families’ efforts in the service of our country, builds camaraderie/bonding/networks and is FUN! We, at NHA, are totally Committed, Not just involved, to delivering on that challenge!

Together we will “Master the Machine” that is your NHA!

“If you are in trouble anywhere in the world, an airplane can fly over and drop flowers, but a helicopter can land and save your life.”

Igor Sikorsky

Igor Sikorsky

As always, I am, V/r and CNJI (Committed Not Just Involved), Dano

Rotor Review #159 Winter '23 6 Chairman’s Brief

Executive Director’s View

Mastering The Machine (NHA) – Take Two

By CAPT Jim Gillcrist, USN (Ret.)

HappyNew Year to all – in this column, I am rolling in hot, right behind RADM “Dano” Fillion.

Upon flight logbook review:

• Logged 117+ hours in the T-28B Trojan

• Logged 1,008+ hours in the SH-2F Seasprite

• Logged 1,725+ hours in the SH-60B Seahawk

In other words, I got real good in three specific aircraft. Meaning, I mastered each of these machines in keeping with the theme of this issue.

So, when it applies to our professional organization, mastering NHA means that members appreciate why they join and/or renew their membership – it is that simple – and they are involved.

The question … “Why NHA?” … has been baking in my mind since I took over as Executive Director in 2019. From my view almost four years later, the question needs to be restated and should read … “Why wouldn’t you join and stay current in your professional organization?” This became clear at the 2022 Gulf Coast Fleet Fly-In (GCFFI) when I addressed this question, to the crowd in the Atrium, at the National Naval Aviation Museum.

Mastering NHA recognizes that the organization is unique as we promote Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard Rotary Wing, Tilt Rotor, and Unmanned Aviation. Its members include pilots, aircrewmen, and maintainers because that is how we operate and deploy – as a team, and that is also how we succeed.

NHA continues to get healthier with membership and volunteerism up. JOs and Aircrew themed the 2022 Symposium and GCFFI and then planned and executed both events for members – creating more connection professionally and personally, as well as enhancing the pure fun of gathering as members of the Rotary Wing / Tilt Rotor Community.

WE ARE A RELATIONSHIP ORGANIZATION. Meaning that the relationships we make at the squadron and aboard ships on deployment are lifelong, enriching, and purposeful. These same relationships continue downstream and remain powerful in our military careers, as well as when we transition to our next adventure outside of the service. We look after one another and pay it forward continuously. This awareness is the essence of mastering the NHA machine.

Nowhere is this “brotherhood and sisterhood” and sense of community more striking than was on display recently in Norfolk during a Santa Flight that originated out of HSC-2 on Saturday, 3 December – please see the full story on page 61.

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 7

Fleet Angel Santa Flight low pass over Oceanview Beach Front

Nuff said, 2023 will be a big year for Rotary Wing and Tilt Rotor Aviation beginning with HSM-41’s 40th Anniversary on 20 January followed by Sikorsky Aircraft’s 100th Year Anniversary as well as the 80th Year of Delivery of Sikorsky Helicopters to the Fleet. Another big milestone is the 50th Year Anniversary of the Induction of the First Six Female Naval Aviators into Naval Air Training. All of this will be on display at the 2023 NHA National Symposium at Harrah’s Resort Southern California from 17-19 May with a theme of … “Forging Legacy – Legends Past and Present!”

Lastly, we are returning to a printed Rotor Review Magazine and Region Stipend Checks in 2023 to continue to deliver value and enrich our professional organization as we all master NHA together.

So, please keep your membership profile up to date. If you should need any assistance at all, give us a call at (619) 435-7139 and we will be happy to help – you will get Linda, Mike, Allyson, or myself.

Warm regards with high hopes, Jim Gillcrist.

Every Member Counts / Stronger Together

We’ve Always Done It That Way

By Jim Stovall

We celebrate entrepreneurship and successful start-ups. These ventures come from new thinking and different ideas born out of invention, innovation, or improvement. When we consider how to move ahead in the future, we must recognize that the enemy is a mentality defined by the statement, “We’ve always done it that way.” The fastest way to never improve is to never change. Not all changes result in improvement, but no improvement comes from maintaining the status quo.

I’m reminded of the story about the bride who wanted to bake a ham for her new husband as her first home-cooked meal. She called her mother to ask the best way to do it, and her mother explained, “You begin by cutting off the end of the ham, then place the ham in a baking dish.” When the new bride asked her mother why she cut off the end of the ham, the mother had to admit she didn’t know, but she explained it was what her mother had told her. The bride decided to call her grandmother to try to solve the mystery of the ham. The grandmother had to admit she had no idea why she cut the end from the ham. It was simply what her mother had done.

The bride continued her quest by calling her great-grandmother in the nursing home. When she asked why she had cut off the end of the ham and why it seemed to be a family tradition, the great-grandmother responded, “I don’t know why anyone else cuts the end from the ham, but I did it because my pan was too small.”

One of the most powerful exercises you can undertake in your personal or professional life is a practice I call deconstruction. This endeavor is a mental process in which you consider everything you’re currently doing and ask, “Why?” Then you consider everything you’re not doing and ask, “Why not?” Socrates said, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” Everything needs to be placed under the microscope and scrutinized. There should not be any sacred cows in your life.

In the final analysis, all we have is our time, effort, and energy. If there’s a better way to utilize these assets, we must embrace it. Even if we undergo the process of deconstruction within an area of our life and determine everything is as it should be, it’s much like going to the doctor for a checkup and being given a clean bill of health.

As you go through your day today, question everything and embrace the possibilities.

Today’s the day!

About the Author

Jim Stovall is the president of the Emmy-award winning Narrative Television Network as well as a published author of more than 50 books—eight of which have been turned into movies. He is also a highly sought-after platform speaker. He may be reached at 5840 South Memorial Drive, Suite 312, Tulsa, OK 74145-9082; by email at Jim@JimStovall.com; or by phone at 918-627-1000

Rotor Review #159 Winter '23 8

Whiting Field: The Past and the Present

By LCDR Bill "WYLD Bill" Teal, USN

Aswe start our ramp up for Symposium this spring, it is a great time to round up your wardroom to support NHA. As with past years, the Max Beep Award will be back up for grabs, which means cold hard cash for the winners. Stay tuned to your email to learn about deadlines and the new structure. In the meantime, this is a great time to check your membership status and update your profile. You can also encourage your squadron mates to sign up if they aren’t yet. If you are an NHA squadron representative, feel free to reach out with a current squadron roster to membership@navalhelicopterassn.org and we’ll help you find the membership status of your ready room.

Congratulations to our Newest Life Time Members! NHA for Life

Aaron Beattie

Jon Berg-Johnsen

Brett Crozier

Tim Dinsmore

Tom Dunn

Chuck Erickson

Mark Eubanks

Guy Henry

Brad Homes

Robert Jackson

Riley Jones

Al Keil

Dave Kiser

John Linquist

Peter Linsky

Tom Pankey

Scott Pritchard

Jim Raimondo

Nick Ross

Matt Russ

Patrick Smith

William Solt

Taylor Sparks

Tim Symons

Tim Thomassy

Ken Ward

Andrew Webster

AugustusWill

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 9 VP of membership Report

Mastering the Machine

By CDR Emily “ABE” Stellpflug, USN

Justdays ago, I was flying a brand-new CMV-22 over the Mojave Desert on a picture-perfect, CAVU day. Our mission: to practice automation features to confined areas or potential reduced-visual landing sites. The Osprey has an impressive autopilot, affectionately known as "George." George can fly an entire route of flight, transition from airplane to VTOL mode, descend, and decelerate to a perfect 20-foot hover over a specified waypoint. While George is a fantastic tool, the key is successfully commanding George and accurately assessing whether it is executing the commands. We had specifically pre-briefed for this flight that if George isn’t doing what we want, we will clear the panel and hand fly. In theory, if operated correctly, all maneuvers should be predictable and benign.

So, there we were. We had input a flight plan out to Rice LZ, set up an initial point prior to Rice that should align us with our intended landing course, and let George take controls. There are a few limitations to the automatic approach feature, including that the aircraft must be less than 800 feet above the waypoint elevation to capture the approach. We started dialing down George’s altitude to ensure we met that criterion. While setting up for the approach, we checked the DAFIF for the waypoint, which specified an elevation of 0 feet. We were gradually stepping down our altitude and dialed in 1200 feet MSL. George had us in a steady descent as my copilot said, “we look low.” A few seconds later, “we look really low.” At 500 feet AGL, we cleared the panel, as briefed, and took over hand flying. Something wasn’t right.

We hand flew the approach, landed uneventfully, and noted that the LZ elevation was actually 900 feet MSL. Once we inserted another waypoint with the proper elevation, George beautifully executed an automatic approach directly to the LZ. The consequences of our relatively simple error could have been much more severe and disorienting during a night-time approach.

This event was a great reminder that being a “Master of the Machine” takes a lot more than just wiggling the sticks. In flight school, we spend much of our time, focus, and energy on being the flying pilot and maintaining basic airwork during a series of maneuvers or flight regimes. However, once we hit the Fleet, we go beyond airwork and require the ability to tactically employ our aircraft. As aircraft become increasingly complex, mastering each capability is more challenging, yet it is imperative to being a professional Naval Aviator.

This issue, “Mastering the Machine,” is aptly named as we ring in 2023 and reflect on 100 years of rotary aviation. The new year also brings us closer to the NHA Symposium at Harrah’s Resort Southern California - 15-19 May! Mark your calendars now, and we’ll see you in May!

Fly Safe!

V/R ABE, NHA Lifetime Member #481

Rotor Review #159 Winter '23 10 National President's Message

Mastering the Machine

By LT Annie "Frizzle" Cutchen, USN

Afew weeks after the theme of Rotor Review #159 “Mastering the Machine” was publicized, I had the pleasure of attending a Tactical Advancements for the Next Generation (TANG) event for one of their projects focused on redesigning the surface bridge.

TANG is a Navy program resourced through OPNAVN94 and executed through PEO-IWS5. For the week we volunteered as the end users of, in this case, the surface bridge project (resourced from SEA21/PMS443 ‘Bridge Integration and Ship Control Systems Program Office’). This was one of two workshops TANG has hosted in an effort to brainstorm solutions and improvements to the surface bridge. Every TANG project typically includes multiple end user engagement sessions throughout the project to ensure their voice is heard.

Leading up to this week, under the guidance of an incredible group of artists and engineers, my own reflection on “Mastering the Machine” elicited thoughts of how I may become better at working with the technology that exists in my aircraft currently to execute the mission at hand. The folks at TANG forced us all out of our comfort zone that is Microsoft PowerPoint, and had us get creative imagining ideas for now and the future that make the technology work for us, not the other way around.

My good friend, LCDR Eric “Pennies” Page, has always been well ahead of me, as I noticed every single flight and conversation we have had together, and wrote an outstanding article in this issue about just that. Another dear friend, LT Nick “SEGA” Padleckas, authored another outstanding article in this issue about how we may push our creative innovations, wants, and wonders to the appropriate level. Pennies’ and SEGA’s articles will give you, as they did me, an idea of just how simple, yet impactful, solutions can be and how we, the end user, can make them happen.

The TANG workshop also provided an immense insight into how we may approach problem solving through a creative lens using design thinking principles. The facilitators encouraged their groups of ranks ranging from E-4 to O-6 to brainstorm in new and innovative ways. They took rooms full of type-A personalities, accustomed to working within the confines of notetaking and outdated computer programs, and forced us to draw pictures and build prototypes out of 3D printed models and pipe cleaners. Challenging us in this way resulted in innovation and creative thinking that I had yet to see in my eight years of service. After the workshops, the project team takes these ideas from the workshops and moves them through the prototyping phase of their project. Ultimately coming up with a few solutions that meet stakeholder, technologist, and end user needs.

I walked away from a week of workshopping the surface bridge with a newfound knowledge that the skills rotary wing aviation builds in us all do translate to the surface Navy. Additionally, should we all take the time to think outside the box and step out of our comfort zone, we may find we have tangible solutions to issues that we face in our respective platforms. To me, “Mastering the Machine” means being brilliant at the basics so we may build upon those to master any mission we are tasked with. It also means knowing our respective machine well enough to recognize where the deficiencies are and correcting those for the next set of end users. Should you have the opportunity, I highly encourage you to participate in any TANG event, whether or not it is aviation related.

This next issue of Rotor Review (#160) will mirror the theme for the upcoming symposium, “Forging Legacy, Legends Past and Present.” The due date for submissions is 27 March 2023. Happy reading!

Rotor Review #159 Winter '23 12 From the Editor-in-Chief

Letters to the Editors

It is always great to hear from our membership! We need your input to ensure that Rotor Review keeps you informed, connected, and entertained. We maintain many open channels to contact the magazine staff for feedback, suggestions, praise, complaints or publishing corrections. Please advise us if you do not wish to have your input published in the magazine. Your anonymity will be respected. Post comments on the NHA Facebook Page or send an email to the Editor-in-Chief. Her email is annie.l.cutchen.mil@us.navy.mil, or to the Managing Editor at rotorreview@navalhelicopterassn.org. You can use snail mail too. Rotor Review’s mailing address is: Letters to the Editor, c/o Naval Helicopter Association, Inc., P.O. Box 180578, Coronado, CA 92178-0578.

RADIO CHECK Tell Us What You Think!

The theme of issue #160 is “Forging Legacy–Legends Past and Present.”

No legends started out that way and most never intended to be legends at all. Some are world renown, while others are only recognized in their own spheres of influence.

Who are those individuals that made our naval rotary wing community what it is today? What qualities make a legend? Have the qualities we value in those we hold at the highest regard changed over the years? Who are our modern-day legends and how do they differ from our legends of the past?

We want to hear from you! Please send your responses to the Rotor Review Editor-in-Chief at the email address listed below.

V/r, LT Annie “Frizzle” Cutchen Editor-in-Chief, Rotor Review annie.cutchen@gmail.com

Articles and news items are welcomed from NHA’s general membership and corporate associates. Articles should be of general interest to the readership and geared toward current Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard affairs, technical advances in the rotary wing / tilt rotor industry or of historical interest. Humorous articles are encouraged.

Rotor Review and Website Submission Guidelines

1. Articles: MS Word documents for text. Do not embed your images within the document. Send as a separate attachment.

2. Photos and Vector Images: Should be as high a resolution as possible and sent as a separate file from the article. Please include a suggested caption that has the following information: date, names, ranks or titles, location and credit the photographer or source of your image.

3. Videos: Must be in a mp4, mov, wmv or avi format.

• With your submission, please include the title and caption of all media, photographer’s name, command and the length of the video.

• Verify the media does not display any classified information.

• Ensure all maneuvers comply with NATOPS procedures.

• All submissions shall be tasteful and in keeping with good order and discipline.

• All submissions should portray the Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard and individual units in a positive light.

All submissions can be sent via email to your community editor, the Editor-in-Chief (annie.l.cutchen.mil@us.navy.mil), or the Managing Editor (rotorreview@navalhelicopterassn.org). You can also use the USPS mail. Our mailing address is Naval Helicopter Association

Attn: Rotor Review

P.O. Box 180578

Coronado, CA 92178-0578

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 13

Naval Helicopter Association Scholarship Fund

The Case for the Roll Vector

By CAPT Arne Nelson, USN (Ret.), President NHASF NHA LTM #4/RW#13762

Inlate 1979, I joined HM-12 as an FRS instructor after first attending the Aviation Safety Officer Course at Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) Monterey. Though better versed in the arts than the sciences, I really hit the books. When complete, I was proud to have earned three hours of undergraduate aerodynamic credits, an Aviation Safety Officer (ASO) Course Certificate, all for running 100 miles in 6 weeks. I was feeling healthy ... and smart! Filled with both academic and athletic fervor, I joined the squadron flag football team with our skipper, CAPT Dreesen, as the team captain and quarterback/coach.

As the squadron’s new ASO, my job included passing on my newfound knowledge of helo aero, and tons of other useful stuff, to the Ready Room. My first lecture was a lesson in dynamic rollover.

Having prepared a ten-minute session, I drew graphs to show how the lift vector rapidly becomes a roll vector if one of your landing gear is chained or otherwise fixed or obstructed (scupper, big rock, hole in the runway) and you pull up on the collective.

Shortly, the blackboard was covered in diagrams and even a little math. Doing my best to capture the full attention of a crowd of FRS instructors, I looked out at my colleagues to find no one paying attention (if only I could cartoon this with thought bubbles above each head...).

Finally, getting to the penultimate graph, the takeoff diagram, I emphasized tail rotor thrust and the roll vector. Then, in a final attempt to make aero exciting, I drew some arrows from the roll vector to the top of the blackboard and said in my best sports announcer voice:

"... Smith breaks out from coverage downfield. The Skipper drops back, rolls right, and pivots, throwing it long...and Smith catches it ...it’s a touchdown, and HM-12 wins the 5th Naval District Championships!"

Everyone looked up, initially startled, and then the ready room erupted in a great HOORAY!

And that is the case for The Roll Vector! Should read: (OBTW: We took third in the 5th Naval District Football Championships [11/1979])

NHA Scholarship Fund - 2023

The case for a scholarship fund donation.

TheNHA Scholarship Fund (NHA SF) Committee manages a modest scholarship fund for the NHA (~$500-$600k). In essence, the NHA SF Committee finds and manages the funding and the procedures to select and award a minimum of fifteen scholarships to eligible active-duty and reserve as well as enlisted personnel, retired members, and their family members. To fund our annual slate of awards, we manage a healthy investment portfolio and encourage individual donations, endowed gifts, corporate sponsors, and legacy and memorial gifts. Our fundraising season covers all twelve months of the year, emphasizing the 4th quarter of the calendar year.

Our strategic plan guides our annual award limits and the awareness effort needed to bring in adequate funding. NHASF's application period runs from 1 September through 31 January. It is guided by our vision: Position NHASF to be a premier scholarship choice in Naval Aviation in 5 years (2025).

We expect to provide a sound, growing fund base to incrementally increase the dollar value of the fifteen annual awards total to reach $75k ($5000 each) in 5 years (2025).

Rotor Review #159 Winter '23 14

In February, our selection process begins. Run regionally, our selection process consists of up to six NHA regional teams (San Diego, DC, Jacksonville, Norfolk, Pensacola, and overseas) and one functional group (graduate, active duty, military spouses including Gold Star family members). In February, each region/group receives a slate of applicants to “rack and stack,” then forwards their recommended slate of candidates and alternates to the Board of Directors. The Board of Directors approves the slate in April. Announcements are made at the NHA Symposium in May. Once announced, funds are sent directly to the registrar/admission/finance office of the selectee's university or college for tuition purposes. Fundraising and awareness continues through all twelve months.

Throughout the year, we encourage our members to donate generously and to encourage our shipmates and their families to apply.

Thanks for your support.

Aboard USS Midway Museum

The Midway Foundation Pillars of Freedom Awards

On10 November, USS Midway Foundation announced their 2023 Pillars of Freedom Grant Awards for the community, with 17 recipients sharing $627,000. NHASF was awarded $12,000, covering three $4,000 NHA Scholarships for 2023.

Receiving the award for NHA, CAPT Arne Nelson, USN (Ret.) said, “The USS Midway Museum continues to be a pillar of our community. Along with being the top attraction in San Diego, they give back generously. This is the fifth consecutive year the Foundation has awarded NHA with a generous grant. We appreciate your generosity and leadership in philanthropy.”

2023 Applications for one of 15 annual NHA Scholarships will be accepted through 24 January 2023; complete applications must be received by NHA Scholarship Office by 31 January 2023. The selection process will commence in February and after Board approval award winners will be announced at the May 2023 Symposium and published in Rotor Review.

Find out more by visiting our website:

Membership: https://www.nhascholarshipfund.org

Application and prescreening: https://www. nhascholarshipfund.org/

Arne Nelson Captain U. S. Navy (Ret.)

NHA Scholarship Fund President

LTM #4 Rotary Wing Number - 137562

P.O Box 180578 Coronado, California 92178-0578

(619) 435-7139 Office / (619) 607-0800 Cell www.navalhelicopterassn.org www.nhascholarshipfund.org

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 15

“Apply and Donate”

USS Midway Foundation President Laura White, and Robin Hatfield present a check to CAPT Arne Nelson, USN (Ret.).

Naval Helicopter Association Historical Society

Happenings at NHAHS

By CAPT Bill Personius, USN (Ret.), President, NHAHS LTM#46 / RW#16213

Happy Holidays and Merry Christmas!

Another year is behind us now to put into the books. It has been a good and productive year for NHAHS with a number of things accomplished and to be thankful for:

NHAHS and NHASF had a successful charity golf tournament 10 November right before the Veterans Day Holiday at the Admiral Baker South Golf Course. The weather was great and 125 golfers shared an outstanding round of golf and a nice lunch afterward at the clubhouse. A team of JO’s from HSM-41 Seahawks named “Big Putts” walked away with the big prize which was a silver trophy cup standing 36” tall. HSM-41 will defend their title at the Golf Tournament next year to be held in connection with the 2023 NHA Symposium in May.

Thanks to the efforts of the Midway Museum, HSC-4 Black Knights, and some members of NHAHS, the H-3 Sea King at Flag Circle has been freshened-up and painted and is looking good once again. This year’s Chief Selects also washed all the aircraft at flag circle as a community service project again this year and had some fun while doing it. Thank you to the new Chiefs for keeping our display aircraft looking good!

The Gifting Paperwork for the SH-60F CDR Clyde E. Lassen, USN (Ret.) Medal of Honor Memorial Display Aircraft at the front gate for NAS North Island is at the OPNAV Staff in the DNS Office and hopefully will be endorsed and then forwarded across the hall in the Pentagon to the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Energy Installations and the Environment. With any luck we are hoping that by the time this issue of the Rotor Review is published that we will know something positive about the request and that we will be working on contacting Davis Monthan Bone Yard

and making the arrangements for a truck to have the aircraft transported back to San Diego so it can be inducted into the Midway Restoration Hangar 805 on base. We are still collecting money to make this project a reality so if you are interested in helping out, please make a donation. Every little bit helps. Plus with the brick project at the base of the monument, you have an opportunity to have your name or a message left there for everyone to see. The details of how to donate are on page 17.

The Jack Rabbits to Jets history book about NAS North Island is in work and we are hoping to have a solution for publishing the book and making it available to those interested in having a copy soon. There is still work to do proofing and fact checking the book, however, the goal is to have it published sometime in 2023.

We are currently working with Mr. Hank Caruso to create a “helicatures book” (a book of helicopter character drawings) and we are hoping to have a preview available at the 2023 Symposium.

We are also working to fund and produce a movie about HC-7. "Leave No Man Behind - The Untold Story of HC-7." Helicopter Combat Support Squadron (HC-7) was formed during the Vietnam War and its primary mission was combat search and rescue (CSAR). Their mission was not for the faint

Rotor Review #159 Winter '23 16

Sea King at NAS North Island Flag Circle - Looking Good!

of heart. CSAR is often dangerous and requires persistence to get the downed airman out of danger. HC-7’s legacy of rescuing downed pilots, often deep in enemy territory, epitomizes the mantra “Leave No Warrior Behind.” Among the tenacious airmen who flew these often-dangerous missions was Clyde Lassen. He was only one of four naval aviators to be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his heroism in Vietnam. By the end of the war, HC-7 had rescued nearly 150 personnel and 94 aviators from Vietnam and the Gulf of Tonkin. HC-7’s stellar performance and the awards given to its members established HC-7’s reputation as “one of the most highly decorated squadrons in Naval Aviation history.” By September of 1967 when HC-7 was established, Vietnam was quickly becoming the “helicopter war.” Helicopters were its defining mode of transport and the image that remains in the minds of most Americans today. These birds brought men into battle and carried them home. We are hoping that the movie will premiere in 2023.

We are also working to identify the Mark Starr Pioneer Award Recipient who will be announced at the 2023 NHA Symposium in May.

We are looking for some assistance to find a home for a Night Vision Device (NVD) Terrain Board that we acquired. This is a 10’ x 10’ display used for NVD/G training and everything works! We have tried to see if USS Midway, the San Diego Air and Space Museum or the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola wanted it, however, neither were interested. While the board does not come with any goggles, we have found that we were able to borrow some goggles from a local squadron to try to find the board a new home. We also have a contact at Raytheon who might be willing to sponsor the display depending on where it ends up. If you or someone that you know might be interested in having the board, please let me know. It might also make a nice train set display too if you know someone into trains.

That is about it for NHAHS for this issue of Rotor Review. If you are interested in our helicopter history, send us a note, check out our website, send us a story, donate some memorabilia, or attend one of our meetings. Contact me at billprsonius@gmail.com or 858-449-1726.

Keep your turns up, Regards,

Bill Personius

HC-7 Movie for Television - NHAHS is Still Collecting Donations

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 17

Computer Rendition of NASNI Stockdale Entrance with SH-60F on a Pedestal

Mail Checks to: Naval Helicopter Association Historical Society, Inc. (NHAHS) NASNI SH-60F Project PO Box 180578, Coronado, CA 92178-0578

To donate with PayPay visit https://www.nhahistoricalsociety.org/indexphp/donations/ and click on the PayPal icon or copy and paste this link in your browser https://www.paypal.com/donate?token=dUz7iSsDDUkFxuXCIsSpZE5lRrmAZ7M5diK1LRJ315ULqrsnyvU3nuz4WHPu0z4ZBCW7xiw34NubTIs

Rotor Review #159 Winter '23 18

PayPal Donation Link

The Next Generation – Embracing Technology to Expand on the Tried and True

By CAPT Jade Lepke, USN Commodore, Training Air Wing Five

Naval Aviation training is rapidly evolving after remaining stagnant for decades, and today’s newest generation of aviators are embracing the change. As our Fleet warfighting platforms continue to evolve, so too are our methods of training. Our newly commissioned Officers and Sailors are arriving to the Fleet having been trained in the tried-and-true basics that have stood the test of time; however, fundamental skills they learn are now being reinforced with realistic hands-on training through technology.

Across the Navy, we have learned that readiness and safety are byproducts of currency and proficiency gained through reps and sets. These reps and sets often elude us when resources are scarce. Lessons learned through mishap investigations in both Naval Aviation and across the Navy draw a direct correlation to old and outdated methods of training to flight crews and bridge watchstanders that deserve more relevant and impactful training than what we’ve provided in the past. Mishaps aboard the USS Fitzgerald (CG 62) and USS McCain (DDG 56) were no surprise to anyone who had visited bridge simulators in Norfolk and San Diego. As a Navigator on the USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78), it was readily evident to me that something needed to change when I looked to maintain currency and build proficiency for our navigation team. Our team was forced to travel an hour north of NS Norfolk to Ft. Eustis to train in the only carrier bridge simulator that could fully accommodate a bridge team with navigation charts. Yes, that’s right, to an Army base! Training facilities on NS Norfolk were available, but were lacking to say the least. Following the unfortunate collisions, the surface fleet and the entire Navy has looked to state of the art simulators and commercial off-the-shelf technologies to bridge the gap. Our Navy has improved with Mariner Skills Training Centers that have opened in both Norfolk and San Diego and our leadership has invested in technologies that are transforming Naval Education and Training Command

(NETC) Learning Centers, one at a time with Ready Relevant Learning. We are also bringing the training directly to the carrier piers in mobile classrooms that can move from one pier to another.

Naval Aviation leadership has also made the needed investment in our future throughout Chief of Naval Air Training (CNATRA). Naval Aviation Training Next (NATN) is a concept that is proving that commercially available technologies can be modified to provide high fidelity training to our fledgling aviators throughout their entire training pipeline. Project Avenger is the first NATN Program that incorporates technologies such as virtual reality, mixed reality, and 360-degree immersive videos into a new agile training syllabus focused on a small group or det concept. With help from Naval Air Warfare Center Training Systems Division (NAWCTSD), technologies such as mixed reality have also been able to transform low fidelity or no fidelity simulators from instrument trainers into fully functional simulators with 360-degree views and flight characteristics that arguably match our highest fidelity simulators, at a fraction of the cost. Project Avenger students are also able to practice instrument approaches in virtual reality sims with off duty FAA Air Traffic

Rotor Review #159 Winter '23 20 Commodore's Corner

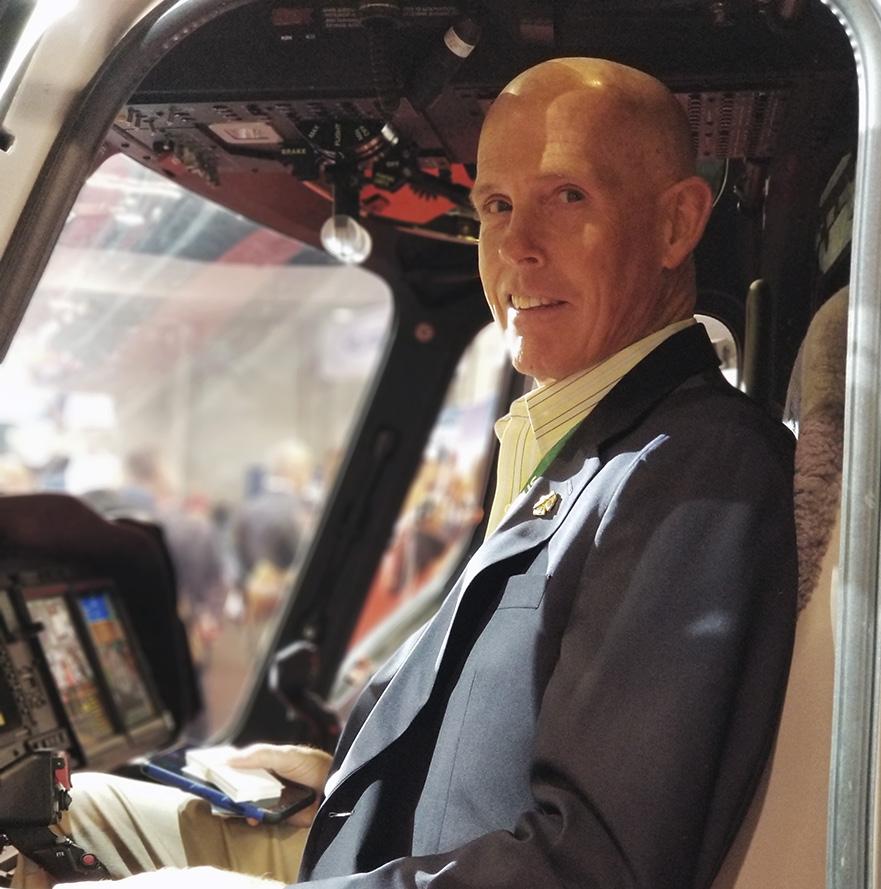

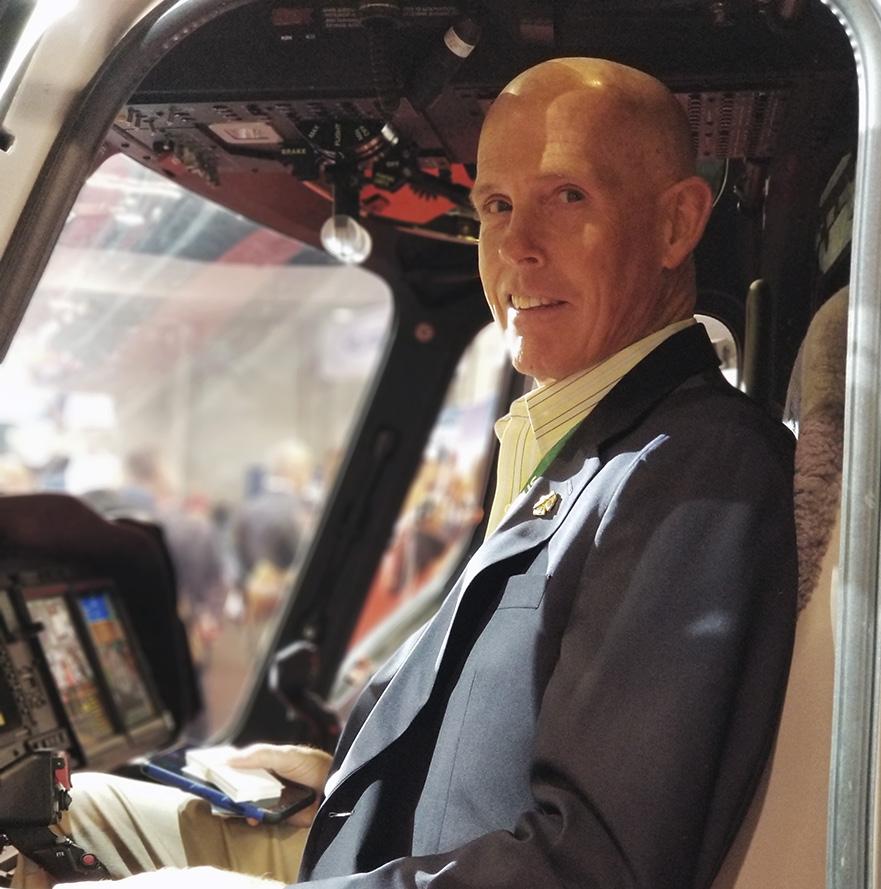

The first two TH-73A Thrasher student naval aviators(SNA) completed their solo flight Nov. 14 in the new training helicopter. Captain Jade Lepke, Commodore, Training Air Wing Five, congratulated the SNAs upon arrival. HT-8 is the first training squadron to employ the TH-73A Thrasher with SNAs. Photo by Julie Ziegenhorn, Naval Air Station Whiting Field

Controllers linked in and controlling multiple students at a time in the same airspace. This is an example of chair flying that could have only been imagined by Gen X. The concept behind NATN is not to replace flight time with simulator time, but to make each minute of training in the aircraft more impactful.

Gulf Coast Fleet Fly In 2022 celebrated the next generation of training at South Whiting Field. With almost 30 of 130 new TH-73 Thrashers on the flight line, the first students have completed their solo flights and are on their way to earning Wings of Gold. Gone are the days of steam gauges and instrument scan patterns that change from platform to platform. Moving from the T-6B to the TH-73 and then onto any of the Navy, Marine Corps, or Coast Guard Fleet aircraft will require only a minor modification to scan patterns. CRM is further reinforced in the new training syllabus with navigation and flight control systems in the TH-73 that closely mirror our Fleet aircraft. The fidelity of our new simulators has been described by the FAA as the best they have ever seen. Like Project Avenger, TH-73 students are no longer learning checklists and chair flying in static trainers. Instead, this generation of aviators is being trained in newly arriving mixed reality trainers and our classrooms are being transformed with interactively linked desktop trainers that bring the cockpit into the classroom with hands-on learning. These trainers are expected to be available to students for up to 20 hours a day to increase exposure and allow for reps and sets prior to graded simulator and flight events.

The future of rotary training at Whiting Field will continue to modernize over the next three years and beyond. Training Air Wing (TRAWING) Five will transition all three Helicopter Training squadrons to the TH-73, with Helicopter

Training Squadron Eight (HT-8) currently in the transition and HT-18 and HT-28 beginning the transition in FY24 and FY25 respectively. Additionally, the construction of our new training facility will begin this fiscal year and is expected to be completed in 2025. A new multi-use squadron ops/hangar facility is also expected to begin construction once funding for FY25 is secured. The Advance Helicopter Training System (AHTS) is not just a program to introduce a new training helicopter, but a comprehensive modernization of aircraft, facilities, and training that will sustain us into the future.

As our newly trained aviators begin to arrive at Fleet Replacement Squadron (FRS) and the Fleet, CNATRA training wings will need continuous feedback from Fleet Commodores, COs, and FRS instructor pilots and aircrew. Additionally, active Fleet participation in CNATRA Production Alignment Conferences and Curriculum Conferences will allow us to further improve training and ensure we focus on the needs of the Fleet. Embracing technology in our training pipelines does not mean we are throwing out the past for the sake of change. Instead, technology is helping our newest aviators keep pace with the systems they will be expected to manage in the Fleet. We need your feedback to ensure our training is hitting the mark and you are getting exactly what you need.

In closing, it is important to credit the efforts of those who have worked tirelessly to bring the entire AHTS program to the execution phase. A special thanks to the efforts of the TW-5 Fleet Introduction Team, both past and present, and also to the members of our team from N98T, PMA-273, Fleet Readiness Center Southeast (FRCSE), CNATRA Fleet Support Team, NAWC-TSD, and our industry partners, many who have worked long hours in uniform and beyond to secure the future of Naval Aviation.

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 21

Training Air Wing Five’s first 12 student naval aviators to begin training in the new TH-73A Thrasher helicopter stand in front of one of the aircraft in early September. This training system includes a new syllabus, virtual reality simulators, and the infrastructure to support the aircraft. Photo by LTJG Nelson Chandler, NAS Whiting Field Public Affairs.

Individuality in the Uniformed Service: Breaking the Cycle of Hypervigilance

By LCDR Rob “OG” Swain, USN (CVW-5)

Tanoshi kyujitsu (

), Naval Helicopter Association! Carrier Air Wing FIVE and Task Force 70 remain underway to support security operations in the Philippine Sea. On the Ronald Reagan deck plates, you can feel the emotional tides shifting in response to the uncertainty of our homecoming date. Originally scheduled to return to Japan in time for Thanksgiving, I booked non-refundable tickets back to the states for late December to celebrate New Year’s Eve with some of my favorite people in the Naval Helicopter community. Now approaching the second week of December and still underway, I am listening to the murmurs of a second extension crescendo, and considering that “nonrefundable”tickets may have been a mistake.

When your forward operating base can move 600 miles a day without severing the satellite umbilical to higher headquarters tasking, the reality of Navy life is that change is inevitable. Emergent threats demand tactical action, and the speed of relevance requires immediate flexibility. The dynamism of naval operations not only strains unit planners, it risks fatiguing every Sailor. Pilots and Aircrewmen are particularly susceptible to change-related stress. Too often, aviators allow their entire lives and self-worth to orbit around their billet, the flight schedule, or the leadership decisions implemented by their chain of command. In this issue of RFTRS, therefore, we’re going to talk about “Identity.”

The Naval Aviation Enterprise mirrors the structure of tight-knit organizations throughout the Department of Defense, Department of Homeland Security, and Law Enforcement. Carefully orchestrated periods of indoctrination, standardization, and adversity bind individuals from disparate socioeconomic backgrounds, creeds, and beliefs under a new banner of fraternity and Navy core values. This professional alignment, however, carries certain risks to a lifetime of individually-shaped personal identity. The aviator can begin to exhibit a physiological pattern coined “hypervigilance.”

The experiences, language, and danger inherent in flying naval aircraft prove difficult to emotionally translate to an outside audience. This environment passively invites aviators to cloister from the outside world and choose the path of least resistance toward a life defined, and self-worth dictated, by the squadron, staff, or ship. Slowly but surely, an aviator can dilute their identity from “I am Rob Swain” to “I am a Naval Aviator.” Hypervigilance is revealed when the individual is engaged, focused, social, and high-performing at work, but quietly in the background, balance in their personal lives atrophies. Preoccupation with the job begins to eclipse the hobbies, goals, values, and relationships which fortify service member resilience. If the hypervigilance cycle is not broken, then the support structures which equip a person to continue a life of committed, enthusiastic service erode, replaced by cynicism and disillusionment toward that very service.

Rotor Review #159 Winter '23 22 Report from the Rising Sun (RFTRS)

During my first seven years in the Helicopter Sea Combat community, I enjoyed immense job satisfaction. I benefited from leaders who inspired and gave me the latitude to fail and learn from my mistakes without reprisal. I worked with peers who motivated me. I enjoyed diverse flight experiences across the globe and developed an intense loyalty to my squadron. I was also single, rarely socialized with individuals who did not fly the MH-60S, and scorned Department Heads who spent time with their families rather than going to Belmont House of Smoke for karaoke on a Wednesday night. Over time, my sense of self and my professional reputation began to blur into one indistinguishable set of metrics. I was functioning in the hypervigilance cycle, but did not recognize the risk because I was having fun.

My first few months on CVW-5 staff threw all of that out the window. On my first day in the new billet, I rapidly recognized that all of my previous job satisfaction and community rapport had not followed me on the Trans-Pac. With no turnover and minimal carrier experience, I labored to orient myself in this foreign environment. I could sense a heaviness in the cultural atmosphere generated by a strike group trudging into year three of forward-deployed COVID restrictions. For the first time in my career, I experienced overt and covert prejudices against helicopter pilots and took it personally. I was straight-up not having a good time.

Shortly thereafter, I started this column because I love to write. I set a personal goal to enter the 1,000 lb club (which I had very publically failed at on the Aqaba, Jordan pier as a junior officer). I took leave over the holidays to spend time with loved ones and take off the flight suit for a few days. I took pride in flying helicopters, made efforts to increase mutual understanding of platform capabilities, and sought opportunities to integrate helicopters across the strike group and joint force. I started reading books that interested me, some related to the military, some not. I diversified my emotional investments outside of “the job” and found that it produced a source of strength and greater positivity in my work. The consistent positive attitude afforded by a balanced personal life increased trust between me and the organization. This led to reinvigorated job satisfaction and professional commitment. While I initially feared forward deployment had been a professional mistake, my time with CVW-5 came to yield some of the most rewarding moments of my career.

The Navy is an Armed Service. Service requires sacrifice. Sacrifice demands selflessness. The uniquely American strength of our Navy lies in the creativity, personal liberty, and individuality of our Sailors. To give of one’s self in defense of one’s country affords no higher honor. In doing so, however, do not compromise all of the wonderful qualities, interests, ambitions, and relationships which make you, you! Attending to these internal aspects independent of your career will steel you with the resolve to handle any spoolex, extension, ORDMOD, or disappointment without challenging your sense of self. It has been a privilege to share the “Report from the Rising Sun” over the past 18 months, and I look forward to continuing to share this great Navy adventure with you all!

I did not handle the changes gracefully. I felt undervalued. It led to sleeplessness, irritability, and waking anxiousness. I began firing off emails to mentors, friends, and family in an effort to understand why, for the first time in over a decade of military service, my commitment to the Navy was wavering. I tried to google “Harvard Graduate School application,” but the afloat CANES network blocked my search. I battled an internal victimization characteristic of so many service members who allow consistent professional validation and personal identity to merge into one amorphous definition of self-worth. When my work-relationships changed, when the job description changed, when the professional responsibilities, trust, and environment changed, I experienced conflict in my own personal perception.

About two months into that first deployment with CVW5, I received a response from my former Weapons School Pacific Commanding Officer. In a straight-forward message characteristic of his transparent leadership style he wrote, “Don’t be who you think the staff wants you to be, be yourself and everything else will fall into place.” His message resonated with encouragement to break the hypervigilance cycle.

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 23

“Don’t be who you think the staff wants you to be, be yourself and everything else will fall into place.”

Torii Gate at the Itsukushima Shrine

Mastering the Machine

By CAPT George Galdorisi, USN (Ret.)

Our Rotor Review editors have teed up a great topic this quarter. It is one that looks ahead, and one that will have the potential to impact our community for years and decades to come. Mastering the Machine is an important issue. Said another way, the future clearly involves both humans and machines.

The DoD’s “Third Offset Strategy” emphasizes manunmanned teaming, the essence of the relationship between machines and humans, as a central concept. Since not everyone is familiar with the term Third Offset Strategy, it bears some explanation.

The Department of Defense initiated a Third Offset Strategy to ensure that the United States retains the military edge against potential adversaries. An “offset strategy” is an approach to military competition that seeks to asymmetrically compensate for a disadvantaged position. Rather than competing head-to-head in an area where a potential adversary may also possess significant strength, an offset strategy seeks to shift the axis of competition, through the introduction of new operational concepts and technologies, toward one in which the United States has a significant and sustainable advantage.

The United States was successful in pursuing two distinct offset strategies during the Cold War. These strategies enabled the U.S. to “offset” the Soviet Union’s numerical advantage in conventional forces without pursuing the enormous investments in forward-deployed forces that would have been required to provide overmatch soldier-for-soldier and tank-for-tank. These offset strategies relied on fundamental innovations in technology, operational approaches, and organizational structure to compensate for a Soviet advantage in time, space, and force size.

In explaining the technological elements of the Third Offset Strategy, then-Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work emphasized the importance of emerging capabilities in unmanned systems, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and autonomy. He pointed out that these technologies offer significant advantages to the Joint Force, enabling the future force to develop and operate advanced joint, collaborative human-machine battle networks that synchronize simultaneous operations in space, air, sea, undersea, ground, and cyber domains. Man-machine teaming is at the core of the technological advances that are part of the Third Offset Strategy.

So what does this mean for our Rotary Wing Community?

Naval Aviation is on a glideslope to be approximately 40% unmanned circa 2035. Some predict this will occur sooner, while others envision the percentage of Naval Aviation that is unmanned will approach 60% by then. It is difficult to pin down a precise number that far into the future.

What is clear is that our community would be well-served to lean into planning how our modern platforms will capitalize on the synergy that comes with man-machine teaming. We have taken modest baby-steps by putting the MH-60S Knighthawk and MQ-8C Fire Scout onboard the Littoral Combat Ship. These two platforms have the potential to be the model for man-machine teaming, but we are not there yet. More on that in future columns. While man-machine teaming sounds easy and straightforward, it is not. What is required is serial innovation.

Since innovation is a term that gets thrown around a lot. I want to share with you how the Joint Staff describes what innovation is and what it means to America’s security:

"Innovation is the life blood of national security and national industrial competitiveness." Although the U.S. Department of Defense has historically played an oversized role in stimulating innovation, over the last several decades, while the U.S. enjoyed superpower dominance after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the edge of innovation has dulled. Simultaneously, over the last 20 years, China has modernized its military and employed aggressive and occasionally coercive behavior against U.S. allies in the Indo-Pacific.

Rotor Review #159 Winter '23 24

An MQ-8C Fire Scout unmanned autonomous helicopter attached to the “Wildcards” of HSC-23 moves aboard USS Montgomery (LCS 8) in preparation for an upcoming exercise. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Vance Hand, USN.

View from the Labs

Now, with China as our national “pacing threat,” significant investments are being allocated to innovation in national security, industrial competitiveness, and energy transformation, as articulated in the recent slate of groundbreaking legislation that includes the CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, as well as numerous national defense investments and policies. However, with all this investment, the U.S. is at risk of under-innovating, since the innovation industrial base is now accustomed to “low risk” research that is more attuned to enabling professors to publish in their echo-chamber and offers little to support disruptive innovations. Similarly, U.S. National Labs and other Federally Funded Research & Development Centers (FFRDC) have grown accustomed to persistent funding with little risk, and as a result, deliver little disruptive innovation.

Although the U.S. DoD and large successful business enterprises have become risk-intolerant, they still understand the need to be competitive and desire for disruptive innovation. This dichotomy in thinking underscores the dangers of China as the new “pacing threat.” Although the U.S. is compelled to change, decades of inertia make this very difficult. Nevertheless, the need for change is stark—recently punctuated with lessons from Ukraine and how it surprised the world pushing back against Russia. As methods and materials change, what was impossible becomes possible. What’s needed now is a new approach to disruptive innovation.

Lots of good words, but how does this apply to our Rotary Wing Community? While we have been the beneficiaries of continuously updated – as well as new – platforms over the past half-century, you would be hard-pressed to say that any of this was truly innovative. Each advance was basically a newerbetter version of what came before it.

The information above from the Joint Staff noted that in the war in Ukraine, Ukrainian forces have used innovative methods to take on a numerically superior foe. One of the most dramatic innovations is the way that Ukraine has used unmanned air and surface vehicles to attack Russian naval forces.

Both methods – air and surface – are effective. However, as adversary naval forces become more and more attuned to the unmanned threat, they are increasingly finding ways to take out unmanned aerial vehicles. Unmanned surface vehicles, especially small, stealthy USVs, are much harder to detect and destroy.

This has been proven in a large number of Navy and Marine Corps exercises, experiments, and demonstrations where unmanned surface vehicles have been able to make a substantial tactical and operational difference. As described in numerous professional journals, and as demonstrated most recently in International Maritime Exercise 2022 (IMX 22), held under the auspices of U.S. Naval Forces Central Command, Commander Task Force 59 in the Arabian Gulf,

which focused on the integration of manned and unmanned vessels, USVs are increasingly recognized by the U.S. Navy as invaluable assets in warfare at sea. Two unmanned surface vehicles, the MANTAS (a 12-foot USV) and Devil Ray (a 38foot USV), proved to be the USVs that CTF-59 used most often in these ongoing IMX 22 events, which covered large swaths of 2022.

What does this mean for us in the HSM and HSC Communities? Just this: Attacking adversary ships will always be an important mission for the rotary wing community far in the future. If we think innovatively and truly “out of box,” we should not restrict our notion of manned-machine teaming as only one (manned) air platform operating with another (unmanned) air platform.

Here is an idea that is gaining purchase in several defense circles. Imagine a U.S. surface combatant that discovers an adversary surface ship in a hot-war situation. Clearly, the goal is to “out-stick” the enemy and disable or destroy that ship before the U.S. Navy ship takes a hit. Said another way, standoff distance matters.

How might the U.S. ship most effectively engage the enemy? One standoff tactic would be to send an HSM or HSC helo armed with HELLFIRE missiles to strike the enemy ship. However, with the limited range for the HELLFIRE missile, that puts a $37M MH-60R/S Seahawk/Knighthawk helicopter and its crew well within the range of adversary anti-air systems. While our aviators don’t lack courage, we shouldn’t send them on a suicide mission.

What if, instead, the Navy surface combatant carried a number of MANTAS or Devil Ray USVs armed with oncontact explosives and launched them toward the adversary ship. That would be a good start, but if the adversary ship was over the horizon, these USVs would not get to their intended target.

This is where the Seahawk/Knighthawk comes in. The aircraft could launch, and while staying well-outside enemy anti-air platforms range, use a simple tablet to steer the USVs toward the adversary ship until impact and then let them continue autonomously on the last few tactical miles. This “swarm” tactic has been modeled by various organizations such as the Naval Postgraduate School and Naval War College and has proven to have deadly effectiveness.

This is where many defense experts see manned-machine teaming and “mastering the machine” going in the future. For those of us in the Naval Rotary Wing Community, all we need is to “unleash our innovative selves” and leverage emerging technology to “fly, fight, swim, and win.”

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 25

Return to Basics

By LT Daniel “Roadkill” Lloyd, USN (HSM-72)

Theflight line of South Field looked slightly different on November 1st as students and instructors alike arrived to see the usual array of orange and white trainers replaced with various gray aircraft from the Fleet’s operational commands. Rotary wing airframes from the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard had flown into NAS Whiting Field for the annual start of the Gulf Coast Fleet Fly-In–a weeklong training event designed to bring the vast experiences of the Fleet back to Pensacola to better inform students, currently in the rotary wing pipeline, as well as advertise helicopters to prospective students still awaiting the selection of an aviation community.

The influx of Fleet aviators brings the most up-to-date community details to the students, allowing them to make the best decisions possible regarding platform selection. This is accomplished via static displays and discussion panels, as well as opportunities to ride in and even fly the aircraft from the Fleet.

HSM-40 along with HSM-72, both located in Jacksonville, Florida, represented the Helicopter Maritime Strike Community at this year’s Fly-In. Crews from both squadrons spent a day providing orientation flights to various students in both the primary and advanced pipelines. Students had the opportunity to fly an MH-60R around the pattern at Santa Rosa Outlying Field. This experience also provided invaluable exposure to the MH-60R mission systems. The pilots and Naval Aircrewmen Tactical Helicopter (AWR) discussed the HSM community’s mission in depth in addition to demonstrating a portion of the aircraft’s advanced warfighting capabilities through the use of FLIR and ESM.