conductor John Adams

vocalists Dārta Liepiņa, Jasperina Verheij, Silvija Emilija Suna, Famke Voshol

Louis Andriessen (1939–2021) De Staat (1972–1976)

intermission

John Adams (1947)

Harmonielehre (1985)

• First Movement

• The Anfortas Wound

• Meister Eckhardt and Quackie

Concert ends at around 22.15

Most recent performances by our orchestra: Andriessen De Staat: first performance

Adams Harmonielehre: Nov 2017, conductor Roberto Trevino

One hour before the start of the concert, Michel Khalifa will give an introduction (in Dutch) to the programme, admission €7,50. Tickets are available at the hall, payment by debit card. The introduction is free for Vrienden.

Cover: Photo Katelyn Greer

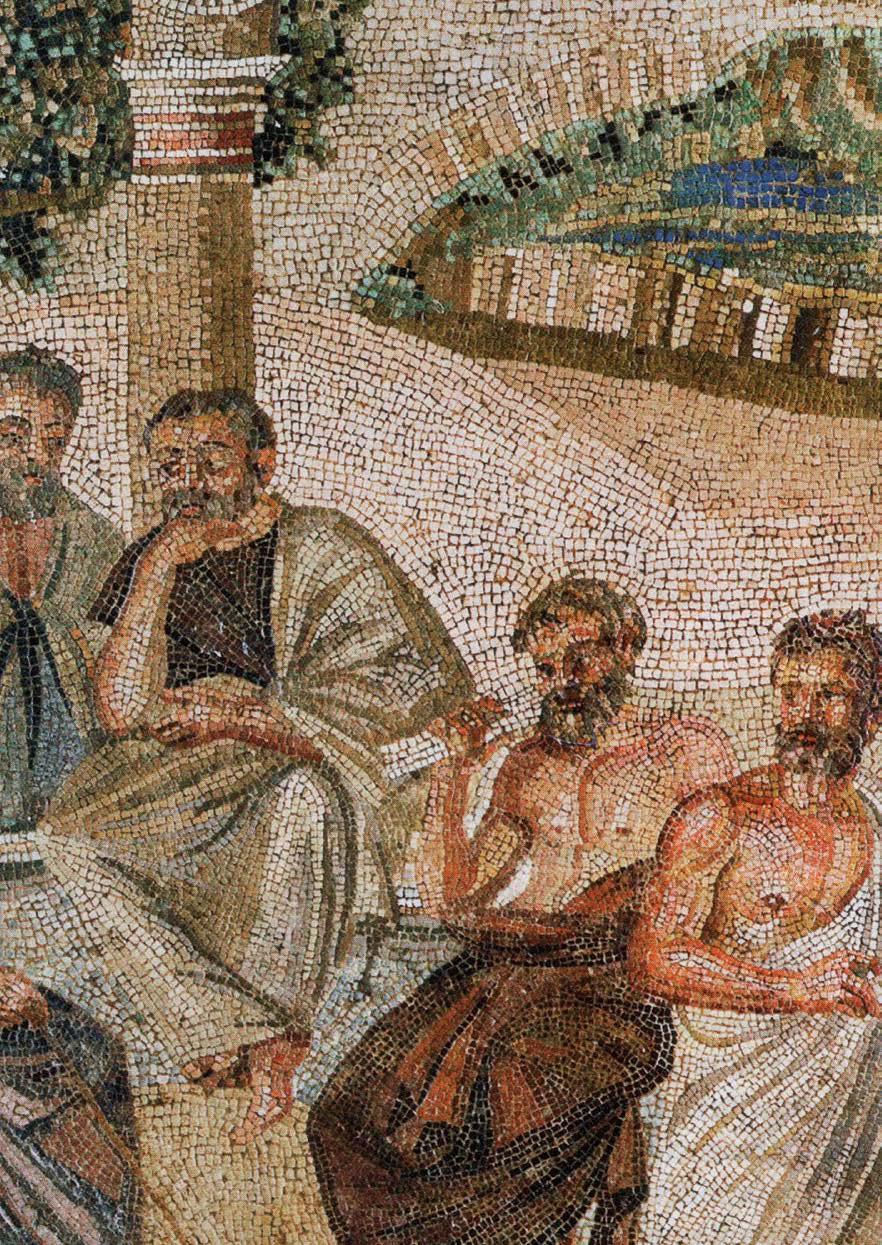

Plato’s academy (fragment): mosaic from the house of Titus Siminius Stephanus in Pompeii, c. 1st century. Coll. National Archaeological Museum Naples

‘De Staat by Louis Andriessen is the only piece by someone else that I would like to have composed’, said John Adams. He came across Andriessen via Edo de Waart, at that time conductor of the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, for which Adams composed his Harmonielehre.

It is not surprising that Adams was enthusiastic about his fellow composer’s music. Although ten years and an ocean separate the two works, there are some remarkable similarities between them. And both works are regarded as the breakthrough of the two composers’ personal style.

At the end of the turbulent 1960s, Louis Andriessen came to the conclusion that music needed to get out of the concert hall, the bastion of the elite, and back into the heart of society. Not long after the Paris student revolt and the Prague Spring, Amsterdam too experienced riots. Young composers who would later become known as the ‘Nutcrackers’ disrupted a concert in the Concertgebouw with rattles and noisemakers: they felt that the Concertgebouw’s programming included too few contemporary works. And that was just the beginning, because as far as Andriessen was concerned, the practices of the world of music as a whole were ripe for overhaul. Everything

ought to be a lot more democratic; musicians were no longer slaves to the score who meekly played what the almighty conductor put in front of them, even though they didn’t feel like it. Not only the composer but also the musicians ought to have a say in the music. Only then could they put their whole heart into it like jazz musicians.

During this turbulent period, in which Andriessen and his ensemble De Volharding took to the streets and played at demonstrations at home and abroad, he began work on De Staat. The title is a reference to Plato’s literary work ‘The Republic’, in which the Greek philosopher describes what instruments and scales have a negative effect on people and should therefore ideally be banned from society. Andriessen’s music challenged Plato’s assertions. He opposed the view that music can have such an effect. ‘If only it were true that musical innovation could change the laws of the State,’ the composer proclaimed on many occasions. After the booming brass at the beginning, in the middle and at the end of De Staat, quotations from Plato’s text are sung by four female voices – a quartet that evokes the association with statues of women that were used as columns in Greek architecture. Although they are amplified, so as to compete with the ensemble, the Greek words are unintelligible. Every instrument in the

ensemble goes against Plato with a pounding barrage of notes: even the listeners at the back of the concert hall have to be convinced. There is nothing Greek about the music, except perhaps for the use of oboes and harps. Andriessen drew his inspiration from jazz, from his favourite composer Stravinsky and from minimalism, the American music genre in which repetitive patterns play an important role. He sought after a musical language that appealed to more people than the rigorous abstraction of the avant-garde, but it shouldn’t sound sweet-toned either. Andriessen was furious with Plato, and that can be heard in the music.

Whereas Andriessen took to the streets in the build-up to De Staat, Adams shut himself away in his studio to compose Harmonielehre. In the early 1980s he was composer in residence with the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, but for eighteen months he was unable to commit a single note to paper. The deadline for the commissioned orchestral work was approaching, and panic struck. Adams’ creative block was broken by Arnold Schönberg, who had both fascinated and intimidated him since his teenage years. In a recurring dream, Schönberg encountered him on a dark forest trail and snatched one of the babies Adams was cradling in his arms. The tormented composer interpreted the dream as the usurping of the tonal system. In Harmonielehre – named after Schönberg’s seminal work on music theory –Adams reaffirmed the power of tonality. You can hear the search for harmony in this music, which ends with a triumphant major chord. Just like Andriessen, Adams turned his back on the European avant-garde that had dominated his student days. Adams too was unable to deny the past and drew from all kinds of musical styles. In Harmonielehre he combined the

chromatic harmonies of the late 19th century with the rhythmic patterns of minimalism. You can hear Wagner (the title of the second movement, ‘The Anfortas Wound’, refers to Wagner’s opera Parsifal), Debussy, Mahler, Sibelius and early Schönberg – ‘enlightened theft’ as Adams himself called it.

Andriessen was furious with Plato, and that can be heard in the music.

The work’s first movement was inspired by another dream: from the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge Adams sees an oil tanker rising vertically from the water like a Saturn rocket and blasting into the sky. Shortly after that dream, he sat down in his studio and found the opening chords of Harmonielehre, almost as if they were waiting for him. It was as if the floodgates that had been shut for a year and a half suddenly opened, such was the speed with which the notes flowed from his pen. Yet another dream image can be heard in the ethereal opening of the third movement, which has the curious title ‘Meister Eckhardt and Quackie’. Adams saw the Medieval mystic hovering in the sky, bearing on his shoulder a cheery infant, his four-month-old daughter Emily, nicknamed Quackie. It was conductor Edo de Waart who first performed Andriessen in San Francisco and – in 1983 – Adams in the Netherlands. Since then, they have often been mentioned in the same breath as representing ‘minimalism’, even though neither of them was a dogmatic follower of that movement. In the case of Andriessen, it was just one of the many styles from which he drew inspiration; he therefore preferred to see himself as a ‘maximalist’.

Carine Alders

Louis Andriessen on De Staat

I wrote De Staat as a contribution to the debate about the relation of music to politics. Many composers view the act of composing as, somehow, above social conditioning. I contest that. How you arrange your musical material, the techniques you use and the instruments you score for, are largely determined by your own social circumstances and listening experience, and the availability of financial support. […]

I have used passages from Plato to illustrate these points. His text is politically controversial, if not downright negative: everyone can see the absurdity of Plato’s statement that the mixolydian mode should be banned as it would have a damaging influence on the development of character.

Foto: Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

Born: Worcester, USA

Education: conducting and composition at Harvard University with Leon Kirchner, David del Tredici, Roger Sessions

My second reason for writing De Staat is a direct contradiction of the first: I deplore the fact that Plato was wrong. If only it were true that musical innovation could change the laws of the State!

Photo: Donemus

Awards: Erasmus Prize (2019); Pulitzer Prize (2003) for On the Transmigration of Souls; Pulitzer Prize Finalist for Century Rolls (1998); Grawemeyer Award (1995)

Honorary doctorates: Harvard, Yale, Northwestern University, Cambridge University, Juilliard School of Music, Royal Academy of Music

Guest conductor: Berliner Philharmoniker, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, Wiener Symphoniker, Los Angeles Philharmonic, orchestras of Seattle, Cincinnati, Atlanta, Toronto

Orchestral works: Harmonielehre (1984), Violin Concerto (1993), Naïve and Sentimental Music (1997-98), Absolute Jest (2012), Frenzy (2023)

Operas: Nixon in China (1985), The Death of Klinghofer (1992), Doctor Atomic (2004), Girls from the Golden West (2017) Debut Rotterdam Philharmonic: 2021

Thu 17 October 2024 • 20.15

Fri 18 October 2024 • 20.15

Sun 20 October 2024 • 14.15

conductor Stanislav Kochanovsky

Tchaikovsky Suite No. 3

Rimski-Korsakov Sheherazade

Fri 1 November 2024 • 20.15

Sun 3 November 2024 • 14.15

conductor Stéphane Denève

piano Marie-Ange Nguci

Boulanger D’un matin de printemps

Saint-Saëns Piano Concerto No. 2

Ravel/Visman Gaspard de la nuit (world premiere)

Stravinsky The Firebird (Suite 1919)

Thu 7 November 2024 • 20.15

Fri 8 November 2024 • 20.15

conductor Tarmo Peltokoski

cello Truls Mørk

Saariaho Ciel d’hiver

Shostakovich Cello Concerto No. 2

Sibelius Symphony No. 1

Wed 13 November 2024 • 19.30

Thu 14 November 2024 • 19.30

Fri 15 November 2024 • 19.30

Sat 16 November 2024 • 13.30 and 19.30

Sun 17 November 2024 • 13.30

Desplat Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows 2

Help us with your review

Do you have a moment? You can help us by leaving a Google review. It will only take a minute: scan the QR code below and let us know what you think of our orchestra. Thank you!

Chief Conductor

Lahav Shani

Honorary Conductor

Yannick Nézet-Séguin

Principal Guest Conductor

Tarmo Peltokoski

First Violin

Marieke Blankestijn, concertmeester

Quirine Scheffers

Hed Yaron Meyerson

Saskia Otto

Arno Bons

Rachel Browne

Maria Dingjan

Marie-José Schrijner

Noëmi Bodden

Petra Visser

Sophia Torrenga

Hadewijch Hofland

Annerien Stuker

Alexandra van Beveren

Marie Duquesnoy

Second Violin

Charlotte Potgieter

Frank de Groot

Laurens van Vliet

Elina Staphorsius

Jun Yi Dou

Bob Bruyn

Eefje Habraken

Maija Reinikainen

Babette van den Berg

Melanie Broers

Tobias Staub

Sarah Decamps

Viola

Anne Huser

Roman Spitzer

Galahad Samson

José Moura Nunes

Kerstin Bonk

Janine Baller

Francis Saunders

Veronika Lénártová

Rosalinde Kluck

León van den Berg

Olfje van der Klein

Jan Navarro

Cello

Emanuele Silvestri

Joanna Pachucka

Daniel Petrovitsch

Mario Rio

Eelco Beinema

Carla Schrijner

Pepijn Meeuws

Yi-Ting Fang

Double Bass

Matthew Midgley

Ying Lai Green

Jonathan Focquaert

Robert Franenberg

Harke Wiersma

Arjen Leendertz

Ricardo Neto

Javier Clemen Martínez

Flute

Juliette Hurel

Joséphine Olech

Manon Gayet

Flute/Piccolo

Beatriz Da Baião

Oboe

Karel Schoofs

Anja van der Maten

Oboe/Cor Anglais

Ron Tijhuis

Clarinet

Julien Hervé

Bruno Bonansea

Alberto Sánchez García

Clarinet/ Bass Clarinet

Romke-Jan Wijmenga

Bassoon

Pieter Nuytten

Lola Descours

Marianne Prommel

Bassoon/ Contrabassoon

Hans Wisse

Horn

David Fernández Alonso

Felipe Freitas

Wendy Leliveld

Richard Speetjens

Laurens Otto

Pierre Buizer

Trumpet

Alex Elia

Simon Wierenga

Jos Verspagen

Trombone

Pierre Volders

Alexander Verbeek

Remko de Jager

Bass Trombone

Rommert Groenhof

Tuba

Hendrik-Jan Renes

Percussion

Danny van de Wal

Ronald Ent

Martijn Boom

Adriaan Feyaerts

Harp

Charlotte Sprenkels