One hour before the start of the concert, Bart de Graaf will give an introduction (in Dutch) to the programme, admission €7,50. Tickets are available at the hall, payment by debit card. The introduction is free for Vrienden.

Cover: New York, view of Liberty Island. Photo Reno Laithienne (Unsplash)

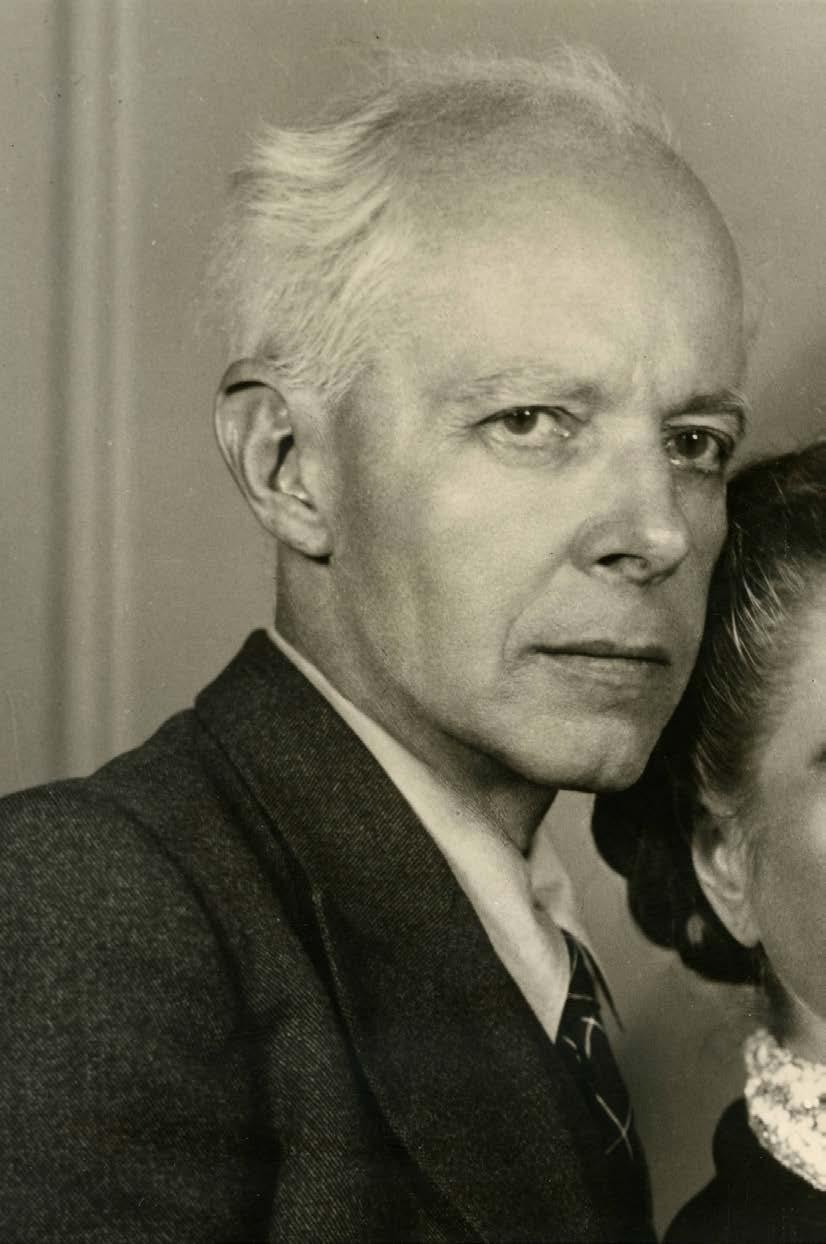

Béla Bartók and Ditta Pásztory Bartók in 1941: Photo Ernest Nash, coll. University of Washington

Blaník. Omslagillustratie door Antonín König voor de eerste uitgave van Smetana’s partituur (1894) Richard-Strauss-Institut

PROGRAMME

conductor Lahav Shani piano Martha Argerich

Joey Roukens (1982)

Con spirito, Overture for orchestra (2024) Commissioned work, world premiere

Béla Bartók (1881-1945)

Piano Concerto No. 3 (1945)

• Allegretto

• Adagio religioso

• Allegro vivace

intermission

Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904)

Symphony No. 9 in E minor, ‘From the New World’ (1893)

• Adagio. Allegro molto

• Largo

• Scherzo. Molto vivace

• Allegro con fuoco

Concert ends at around 22.20/16.20

Most recent performances by our orchestra: Roukens Con spirito: world premiere

Bartók Piano Concerto No. 3: Oct 2023, piano Kirill Gerstein, conductor Lahav Shani (on tour)

Dvořák: Symphony No. 9: Oct 2021, conductor Edo de Waart

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West: playbill for the theatre show Dvořák attended in the spring of 1893. Coll. Buffalo Bill Museum

American Dream, European reality

America has captured the imagination of many European composers. Dvořák discovered the spirituals that inspired his Ninth Symphony. Bartók’s Piano Concerto No. 3 is infused with the echoes of American birdsong. And although Roukens composed his work Con spirito in the Netherlands, this brand-new orchestral work radiates an optimism that seems typically American.

Hall of mirrors

Joey Roukens is a fan of composers including Sweelinck, Stravinsky, Sibelius, and John Adams. As well as the Beach Boys, Keith Jarrett and techno, not to mention the kind of music his colleagues tend to look down on, such as film music or Jacques Offenbach. In short, Roukens has an extremely eclectic taste, which is reflected in the metropolitan, Americantinted music with strong European roots with which he attracts a wide public. Following the success of his Symphony No. 1 from 2021, Roukens composed Con spirito for the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, parts of which take him into new territory. ‘Contemporary composers have forgotten how to write cheerful, energetic music,’ he explains. ‘Haydn, Weber and Poulenc were great exponents, but these days few dare head in this direction. It must be part of the legacy of post-war modernism: music had to be serious and complex. But I want to give it a try: a piece that is cheerful without being bland or superficial.’

Energetic rhythms have always been an element of Roukens’s palette, but never before has he sought such a crazy atmosphere, ‘Like a hall of mirrors at a funfair, full of deformed reflections’. The greatest challenge? How do you keep it playful whilst aiming to deploy the full ranks of the orchestra?

One-way ticket to New York

It would take a lot for Béla Bartók to turn his back on his beloved Hungary, but by 1939 the time had come. For decades he had cherished the folk music of his native country and bordering nations. He based all his compositions on such music. But this love was not mutual. Bartók had been reviled in his own country: too modern, and he ‘cosied up’ with other cultures. So when the country then aligned itself with the Nazis, he emigrated to New York, where he hoped to build a new life as a pianist and ethnomusicologist. It turned out to be a fiasco. America was not interested in his deep knowledge of Balkan music or his idiosyncratic compositions. Worse still, he suffered mysterious symptoms that would be diagnosed – too late – as leukaemia. This was the backdrop against which Bartók composed his Third Piano Concerto – a remarkably gentle piece given his harsh living conditions. A contributing factor was the sudden success of his recently composed Concerto for Orchestra, with which he finally achieved recognition in America. Furthermore, the almost neo-classical form of this work did not come out of the blue; even Bartók’s most modern works have a classical or even Baroque structure. Bartók’s hints of Balkan music are strongest in the outer movements.

But the focus lies in the middle movement that the atheist Bartók strikingly marked as ‘Adagio religioso’. This is a subtle reference to the Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesenden an die Gottheit (‘Holy song of thanksgiving of a convalescent to the Deity) from Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 15, opus 132, the melody from which is briefly quoted. Logically, Bartók brightened up with each improvement of his physical condition, however temporary in nature. And here, the ‘sounds of the night’ – a fixed element in his work - sound consoling rather than troubling, springing this time not from Bartók’s poignant imagination but from the birdsong that he had transcribed from his most recent summer vacation.

Return trip to New York

The contrast could not be greater: Antonin Dvořák, the one-time provincial composer from the periphery of the European music world, had grown into an international star who would cement his reputation in New York. At least, that’s why in 1892 music-school head Jeanette Thurber invited Dvořák to assist young American composers develop their national identity. After all, back home in what is now Czechia, he had demonstrated the alchemy of turning folk music into ‘high art’. For Dvořák, New York was a revelation. He wrote enthusiastically to those back home about the ‘Indian music’ he had heard at a theatre show. He was even more impressed by black music; he believed that gospel music and spirituals could form the basis of a ‘great and worthy American school’.

Ultimately, in America Dvořák was as much a student as he was a teacher; the folk music that he was introduced to coloured a number of his own compositions form that period, principally his Ninth Symphony. However, the American influence did not go too deep; the form, sounds and musical phrasing of the Ninth remained very

European. For example, the work begins with a pianissimo introduction, followed by a robust theme and a tender response which, since Beethoven, has been a typical opening in the European romantic style. What Dvořák did suddenly make frequent use of is the pentatonic scale (in other words, the black keys on a piano) that he picked up in America. It is something that appears in traditional music around the world, but for him it was something new.

Nowhere does Dvořák directly quote existing folk tunes, even though it sometimes sounds like he does. A good example of this is in the Second Movement, in which the oboe plays a gospel-sounding melody. Dvořák’s student, William Fisher, worked the melody into a song called Going Home, that became a favourite in the churches of black America.

Dvořák wrote enthusiastically to those back home about the ‘Indian music’ he had heard at a theatre show

The Third Movement is also a hybrid: the fast introductory theme is again a kind of Beethoven-esque clarion call, although Dvořák himself wrote that he composed this movement in response to reading about a ‘wild Indian dance’. Ironically, when the symphony was subsequently performed ‘back home’ in Prague, his compatriots thought that this movement sounded the most Czech. The almost Tchaikovsky-like, melancholy Fourth Movement also sounds Slavic. In this movement, you hear how Dvořák, despite all his wonderful impressions of America, was tormented by homesickness.

Michiel Cleij

Lahav Shani • chief conductor

Born: Tel Aviv, Israel

Current position: chief conductor Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra; music director Israel Philharmonic Orchestra; chief conductor designate Münchner Philharmoniker (from 2026)

Before: principal guest conductor Vienna Symphony Orchestra

Education: piano at the Buchmann-Mehta School of Music Tel Aviv; conducting and piano at the Academy of Music Hanns Eisler Berlin; mentor: Daniel Barenboim

Breakthrough: 2013, First Prize Gustav Mahler International Conducting Competition in Bamberg

Subsequently: guest appearances Wiener Philharmoniker, Berliner Philharmoniker, Gewandhaus Orchester, Münchner Philharmoniker, Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, London Symphony Orchestra, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra

Debut Rotterdam Philharmonic: 2016

Martha Argerich • Piano

Born: Buenos Aires, Argentina

Education: with Friedrich Gulda in Austria; Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, Stefan Askenase

Awards: Geneva International Music Competition (1957); Ferruccio Busoni

International Piano Competition Bolzano (1957); Praemium Imperiale Award (2005), Kennedy Center Honor (2016)

Breakthrough: 1965, after winning the Fryderyk Chopin International Piano Competition Warsaw

Subsequently: soloist with all major orchestras in the world

Chamber Music: with pianists Stephen Kovacevich, Alexandre Rabinovich, the late Nelson Freire and Nicolas Economou, violinist Gidon Kremer, cellist Mischa Maisky

Festival: honorary president International Piano Academy Lake Como

Documentary: Martha Argerich – Evening Talk 2002

Debut Rotterdam Philharmonic: 1969

Photo: Marco Borggreve

Photo: Nicolas Broadard

Musicians Agenda

Thu 3 October 2024 • 20.15

conductor Joana Mallwitz

piano Leif Ove Andsnes

Prokofiev Overture War and Peace

Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 3

Hindemith Symphonie Mathis der Maler

Ravel La valse

Fri 11 October 2024 • 20.15

conductor John Adams

vocalists Royal Conservatoire The Hague

Andriessen De Staat

Adams Harmonielehre

Thu 17 October 2024 • 20.15

Fri 18 oktober 2024 • 20.15

Sun 20 oktober 2024 • 14.15

conductor Stanislav Kochanovsky Tchaikovsky Suite No. 3

Rimski-Korsakov Sheherazade

Fri 1 November 2024 • 20.15

Sun 3 November 2024 • 14.15

conductor Stéphane Denève

piano Marie-Ange Nguci

Boulanger D’un matin de printemps

Saint-Saëns Piano Concerto No. 2

Ravel/Visman Gaspard de la nuit (world premiere)

Stravinsky The Firebird (Suite 1919)

Help us with your review

Do you have a moment? You can help us by leaving a Google review. It will only take a minute: scan the QR code below and let us know what you think of our orchestra. Thank you!

Chief Conductor

Lahav Shani

Honorary Conductor

Yannick Nézet-Séguin

Principal Guest Conductor

Tarmo Peltokoski

First Violin

Marieke Blankestijn, concertmeester

Quirine Scheffers

Hed Yaron Meyerson

Saskia Otto

Arno Bons

Rachel Browne

Maria Dingjan

Marie-José Schrijner

Noëmi Bodden

Petra Visser

Sophia Torrenga

Hadewijch Hofland

Annerien Stuker

Alexandra van Beveren

Marie Duquesnoy

Second Violin

Charlotte Potgieter

Frank de Groot

Laurens van Vliet

Elina Staphorsius

Jun Yi Dou

Bob Bruyn

Eefje Habraken

Maija Reinikainen

Babette van den Berg

Melanie Broers

Tobias Staub

Sarah Decamps

Viola

Anne Huser

Roman Spitzer

Galahad Samson

José Moura Nunes

Kerstin Bonk

Janine Baller

Francis Saunders

Veronika Lénártová

Rosalinde Kluck

León van den Berg

Olfje van der Klein

Jan Navarro

Cello

Emanuele Silvestri

Joanna Pachucka

Daniel Petrovitsch

Mario Rio

Eelco Beinema

Carla Schrijner

Pepijn Meeuws

Yi-Ting Fang

Double Bass

Matthew Midgley

Ying Lai Green

Jonathan Focquaert

Robert Franenberg

Harke Wiersma

Arjen Leendertz

Ricardo Neto

Javier Clemen Martínez

Flute

Juliette Hurel

Joséphine Olech

Manon Gayet

Flute/Piccolo

Beatriz Da Baião

Oboe

Karel Schoofs

Anja van der Maten

Oboe/Cor Anglais

Ron Tijhuis

Clarinet

Julien Hervé

Bruno Bonansea

Alberto Sánchez García

Clarinet/ Bass Clarinet

Romke-Jan Wijmenga

Bassoon

Pieter Nuytten

Lola Descours

Marianne Prommel

Bassoon/ Contrabassoon

Hans Wisse

Horn

David Fernández Alonso

Felipe Freitas

Wendy Leliveld

Richard Speetjens

Laurens Otto

Pierre Buizer

Trumpet

Alex Elia

Simon Wierenga

Jos Verspagen

Trombone

Pierre Volders

Alexander Verbeek

Remko de Jager

Bass Trombone

Rommert Groenhof

Tuba

Hendrik-Jan Renes

Percussion

Danny van de Wal

Ronald Ent

Martijn Boom

Adriaan Feyaerts

Harp

Charlotte Sprenkels