Get Ready for Back to School with NK.

• Instant Data Access: Seamlessly view your performance metrics on your phone.

• Precision Tracking: Keep an accurate log of every stroke and session.

• Insightful Analysis: Break down your practices and race strategies for continuous improvement.

• Personalized Style: Customize your CoxBox with vibrant bumper colors to match your unique style.

(603) 643-8476

ROWING NEWS is published 12 times a year between January and December. by The Independent Rowing News, Inc, 53 S. Main St. Hanover NH 03755 Contributions of news, articles, and photographs are welcome. Unless otherwise requested, submitted materials become the property of The Independent Rowing News, Inc., PO Box 831, Hanover, NH 03755. Opinions expressed by authors do not necessarily reflect those of ROWING NEWS and associates. Periodical Postage paid at Hanover, NH 03755 and additional locations. Canada Post IPM Publication Mail Agreement No. 40834009 Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Express Messenger International Post Office Box 25058 London BRC, Ontario, Canada N6C 6A8.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: ROWING NEWS PO Box 831, Hanover, NH 03755. ISSN number 1548-694X

ROWING NEWS and the OARLOCK LOGO are trademarks of The Independent Rowing News, Inc.

Founded in 1994

©2024 The Independent Rowing News, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission prohibited.

The U.S men’s four won gold, and the eight captured bronze—an improvement over zero medals in Tokyo but short of the goal of four.

BY CHIP DAVIS

Single sculler Majdouline El Allaoui is a champion back home in Morocco, but like many African rowers, she struggled to compete in Paris.

BY THOMAS EARL

DEPARTMENTS

News Gladstone returns to college coaching Rich Davis, 1937-2024

Race Report North Tahoe Regatta

Sports Science Fin Tuning

Coxing The Art of Making a Pass

Best Practices Rebuilding Season

Fuel Hot Topics for Rowers

Training On the Ball

Coach Development ‘Full Gender Parity’? Yes, But…

2023-24

TRAINING

FISA Class A certified, 10lane protected, buoyed course with coaches lane

Adjacent 1500m practice course

Aluminum gangway with low profile floating docks Hotels, restaurants & attractions within walking distance

CHIP DAVIS

Your coach is the single greatest influence on your rowing experience. He or she teaches you to be better, which can be uncomfortable. You grow and improve as a rower and teammate, and therefore as a person, through that coaching.

What I learned from my father goes far beyond rowing, as it did for the thousands of young people he taught, coached, led, counseled, and inspired.

The 13 U.S. men who won Olympic medals in Paris—the first since 2008—know that truth well, and they nominated their boat coaches, Casey Galvanek and Micheal Callahan, as well as the supportive and influential Mike Teti, Tim McLaren and Kris Korzeniowski, for the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee’s Order of Ikkos.

A coach does not achieve coaching success at the Olympic level without prior championship-coaching success. Both Galvanek and Callahan coached crews to championships on multiple levels leading up to the Olympic level, and, like Teti, McLaren, and Korzeniowski, had great influences on more than 13 Olympians along the way.

I know how influential a coach can be, perhaps better than anyone, through my high-school coach, who was also my father. What I learned from him goes far beyond rowing, as it did for the thousands of young people he taught, coached, led, counseled, and inspired to reach their potential throughout his long life.

Rich Davis died on July 24, and his obituary appears on page 29. Even if you knew him well, you might learn how he helped others quietly and resolutely in ways you never knew. In writing it, I did.

In covering the Olympic regatta, the eighth for Rowing News, I also learned about rowing in parts of the world I never knew through Thomas Earl and his feature (page 48) about Moroccan sculler Majdouline El-Allaoui, who, fittingly, is also a coach.

As much as we celebrate the glory of winning Olympic medals, we also laud the creed of Baron Pierre de Coubertin: “The important thing in the Olympic Games is not winning but taking part; the essential thing in life is not conquering but fighting well.”

No one has explained completely why the 2028 Olympic race in Long Beach can’t be 2,000 meters.

In 1968, we—the Penn Varsity and five other crews—raced the Olympic trials the full 2,000 meters on that course. Yes, there was a bridge at about 500 meters, I think.

Same course, same bridge, same 2,000 meters ending in the 1932 Olympic Water Stadium.

Perhaps Olympic rules require a course without a bridge, but the rules allowed the ‘68 trials on that course. Which is a fairer, more intelligent decision: skipping those rules for the upcoming LA Olympics or having a ridiculously shortened course?

The best answer, unless there’s another

issue, is to race the 2,000 meters and put aside any perceived unfairness of racing under a bridge, since everyone would race under the bridge.

(The ‘68 trials were when the Penn varsity under Coach Joe Burk led everyone for the whole 2,000 meters—except for the last four inches. The New Yorker wrote an article about it, “A Fast and Furious Race!” Harvard won by a photo finish; as Penn was finishing a stroke, Harvard was already driving in its next catch.)

Gardner A. Cadwalader Philadelphia 1968 Olympics, Mexico

Washington, USA

Thursday, Feb. 6 to Saturday, Feb 8, 2025

The Women’s Coaching Conference serves all female rowing coaches, providing attendees with actionable education and community building to ma ximize their current positions and advance to the next step in their careers. The mission of the WCC is to educate, connect, and inspire emerging and established female coaches across the sport. The Winter ‘24-’25 conferences feature top-tier, professional presenters including leadership coaches, athletic directors, and leaders within the rowing community and beyond.

For more information, and to register for the event, visit wccconference.com Space is limited.

British coxswain Harry Brightmore said the essence of Olympic racing is rowing the fastest minute you’re ever rowed, rowing even faster the next minute, and repeating until you’ve won, which his eight did, ahead of The Netherlands and the U.S. “Every crew that has won has pretty much taken it by the scruff of the neck,” said Brightmore. “We lined up on that start line and we were going to sprint to the death, straight from the buzzer.”

ALL AVAILABLE WITH YOUR TEAM LOGO AT NO EXTRA CHARGE (MINIMUM 12)

UNITED STATES ROWING UV

VAPOR LONG SLEEVE $40

WHITE/OARLOCK ON BACK

NAVY/CROSSED OARS ON BACK

RED/CROSSED OARS ON BACK

PERFORMANCE LONG SLEEVES

PERFORMANCE T-SHIRTS

PERFORMANCE TANKS

Order any 12 performance shirts, hooded sweatshirts, or sweatpants and email your logo to teamorders@rowingcatalog.com and get your items with your logo at no additional cost!

Spracklen will coach Duke, and interims become permanents at Tufts, as the coaching carousel spins.

Steve Gladstone will return to collegiate coaching this fall.

“Being appointed the Tom and Candy Knudson Heavyweight Rowing Coach is an honor,” said Gladstone. “There have been many times in the course of my coaching career I dreamed of coming to the United States Naval Academy. Coaching young men who will be serving their country in leadership positions in the military and beyond is an absolute privilege.”

Gladstone was most recently head coach at Yale, where he coached the Bulldogs to three consecutive Intercollegiate Rowing Association (IRA) National

Championships (2017, 2018, 2019) for the first time in program history and won seven straight Eastern Sprints titles.

Gladstone’s 14 IRA Championships during his career, which has included stints at Harvard (lightweights), Brown, and Cal (twice) place him in a tie with Charles “Pop” Courtney of Cornell (1901-15) for the most varsity-eight titles in the history of collegiate rowing.

Duke announced the hiring of Adrian Spracklen as the head coach of its women’s rowing program. Spracklen, who spent the last 32 years as the director of rowing at Mercyhurst University, is the Blue Devils’ third head

The Intercollegiate Rowing Association (IRA) and streaming platform Overnght announced the extension of their partnership through 2030. Overnght has, in just a few months, become the de facto streaming partner of choice for rowing after securing partnerships with the IRA and USRowing. “The IRA is thrilled to continue our partnership with Overnght,” said IRA Commissioner Gary Caldwell. “Their dedication to delivering outstanding content and enhancing the viewer experience aligns perfectly with our mission to promote collegiate rowing.”

coach in the program’s history.

“We are absolutely thrilled to welcome Coach Spracklen and his family to Duke University,” Duke University Vice President and Director of Athletics Nina King said. “Coach Spracklen’s knowledge, drive, and passion, fueled by his well-documented family history, will be instrumental elements in the future successes of the young women in our program, both on and off the water.”

“I couldn’t be more excited to lead the next chapter in the storied tradition of Duke Rowing,” said Spracklen, a native of Marlow, England. “Duke’s philosophy and culture resonate deeply with me, and I am confident in my ability to elevate the program and help it ascend the national rankings.”

Spracklen earned NCAA Division II National Coach of the Year honors in 2004, 2009, 2010 and 2022. A 1990 graduate of Mercyhurst, Spracklen earned a bachelor’s degree in sport medicine before going on to earn his master’s in sport medicine and athletic training from Western Michigan University in 1991.

Adrienne Martelli was named head coach of the Clemson owing program in June 21. Martelli is an Olympic medalist and spent the past five seasons at Cal, most recently as associate head coach, finishing in the top 10 nationally each season. Martelli also coached the 2024 U.S. Olympic team.

The Tufts University Department of Athletics has removed the interim status of rowing coaches George Munger and Lily Siddall heading into the 2024-25 season. Munger has been promoted to director of rowing and Siddall to head coach of the women’s team.

“Without question, the decision to remove the ‘interim tag’ from George Munger‘s and Lily Siddall‘s titles is among the easiest I’ve had to make at Tufts,” said Director of Athletics John Morris.

Munger, the men’s rowing head coach since 2019, and Siddall were both named to interim positions as leaders of the Jumbos when previous director of rowing and women’s head coach Noel Wanner left Tufts for a position at Dartmouth College in August 2023.

Munger and Siddall led the Jumbos to unprecedented success during the 2023-24 season. Tufts’ women won their first-ever NCAA and NESCAC titles in the spring.

The men’s team was the national runner-up at the IRA Division III Championship.

“I am honored to continue working with Tufts Rowing, with whom my first nine years with the program have been very special,” said Munger, who also helped guide the Jumbos to a Points Trophy victory at the New England Rowing Championships in May. “I am grateful for the previous head coaches and program directors who I shared the boathouse with —Noel Wanner, Brian Dawe and Gary Caldwell.”

Under Siddall’s guidance, the Tufts women were the No. 1 team in the Pocock CRCA Poll for most of the spring season. The Jumbos also won the points trophy at the New England Rowing Championships and at the National Invitational Rowing Championships.

“I’m incredibly honored to be named the next head coach of Tufts women’s rowing,” Siddall said “This past year as interim was amazing, and I can’t wait to keep building with the team. Tufts is a place where student-athletes can thrive both academically and athletically.”

Michael Eichler has been named the head coach of Oregon State women’s rowing. Eichler brings more than a decade of experience to the team and finished his seventh season recently as a member of the Beavers’ coaching staff.

“While there were many great candidates for this position, after the success that our women’s rowing team has found in recent years, elevating Coach Eichler to head coach was a no-brainer,” OSU Vice President and Director of Intercollegiate Athletics Scott Barnes said.

Eichler joined the program originally in 2017 as an assistant coach and was elevated to associate head coach in September 2022, while serving as the program’s recruiting coordinator for each of his seven seasons.

“I am excited to continue building a championship mindset day in and day out with the thoughtful and powerful individuals of Beaver Women’s Rowing,” Eichler said. “We want to be fast on the water, leaders at the university, and top performers in the classroom and are eager to continue building on that tradition.

Before arriving in Corvallis, Eichler worked with the United States Junior National Team for five years. He also

worked at Rutgers and Princeton, where he oversaw on-campus recruiting operations.

University of Texas Rowing head coach Dave O’Neill announced the promotion of Gia Doonan to associate head coach and the addition of Lanie Nitsch as assistant coach.

Doonan, who is entering her fourth season with the Longhorns, was hired as a volunteer assistant coach in 2021 and promoted to a full-time assistant coaching role in 2022. Doonan has helped guide Texas to dominance during her span on staff, including three national titles over the last four years and three Big 12 Championships. Under her tutelage, the fours captured back-to-back national championships in 2023-24.

“This program would not be where it is today without Gia Doonan, and the impact she’s made as a coach these last few years has been tremendous,” said O’Neill. “She’s taken the lead on a number of projects that have made a real difference, so this promotion is very well deserved.”

Nitsch joins the staff after a four-year career with the Longhorns from 2021-24. Nitsch, a three-time national champion, helped Texas capture its third national crown over a four-year stretch in June 2024.

“I’m thrilled that Lanie Nitsch is joining our staff for the fall semester,” said O’Neill. “We have a temporary need, and Lanie is the perfect person for this role right now.”

Emily Gackowski, the first-year head coach of the Ohio State Buckeyes, announced the hiring of three assistant rowing coaches. Former Buckeyes Mandy Merritt (2011) and Bridget Schodorf (2018) along with University of Minnesota graduate Mari Sundbo join the Buckeyes for the 2025 season.

Gackowski said the new additions provide the Buckeyes the necessary tools for a winning program.

“Words cannot express how excited I am to have Mari, Mandy, and Bridget joining the staff this year,” Gackowski said. “Any head coach who brings in a new assistant should be excited, but these three are special. They each bring skills, experience, and knowledge that are difficult to come by. We are lucky to have them.”

Merritt coached the Clemson Tigers from 2016-24. During her time with Clemson, she led the novice program and

coached the fours. Merritt joined the Tigers after three seasons at West Virginia.

Schodorf joins the Buckeyes rowing program after coaching with Craftsury’s Green Racing Project.

Sundbo returned to her alma mater in July 2023 as a member of the Golden Gopher staff when she was hired as a varsity assistant coach and also served as the recruiting coordinator.

As the summer marches on, more coaches are finding new homes, most recently at the University of Virginia and Wisconsin. New head coach of the Cavaliers, Wes Ng, announced the hiring of three assistant coaches, two of whom followed him to Charlottesville from his previous stint at the University of Pennsylvania.

Helen (Tompkins) Samaniego, UVa class of 2010, returns to her alma mater after coaching with Ng at Penn for two years before joining the staff last year at the University of Texas.

Josie Konopka, another new UVa assistant, also joins Ng’s staff after having rowed for him at Penn, from which she graduated in 2022 after leading the Quakers to their best performance at the Ivy League and NCAA Championships.

“I knew she would be the first person I wanted to build our staff around,” Ng said of Konopka’s hiring. “Her deep understanding of the sport and her ability to teach and inspire from her firsthand experience will be invaluable to our program.”

To round out the UVa staff, Taylor Ruden makes the move from Ohio State to Charlottesville after four years with the Buckeyes and a successful career at Indiana.

In Madison, Badgers head coach Vicky Opitz announced two additions to the Wisconsin women’s rowing coaching staff. Sophia Vitas, a 2024 Olympian and former Wisco walk-on, will serve as a graduate assistant coach after returning from Paris, where she competed in the U.S. double.

Mary Anderson joins the staff as an assistant coach with the lightweight women after spending the last two seasons at Gonzaga, helping the Zags win West Coast Conference Championships in both seasons with the squad.

MADELINE DAVIS TULLY

25 lbs. 12 oz.

(lightest 1x in production)

Why a light boat?

• Less drag, more speed

• Lighter feel, higher stroke rate

• Easier to carry

How did we do it?

Single skin - kevlar/carbon

No paint on deck

I-beam frame

The lightest fittings:

• Dreher/Peinert rigger - 4.3 lbs.

• Dreher seat - 15.5 oz.

• Carl Douglas tracks - 15 oz.

• Carbon footboard - 15 oz.

• H2Row shoes - 19 oz.

• Molded bow ball - 1 oz.

$9,950 incl. options Made in USA

Richard F. Davis , devoted husband, father, grandfather, and brother, faithful friend, and longtime teacher, rowing coach, and mentor of young people, died in Rye, N.H., surrounded by family, on July 24, 2024. He was 86 years old.

Born on October 4, 1937, in Brooklyn, N.Y., Richard was the son of Virginia Vail Davis and Charles Fletcher Davis. He grew up in New York and New Jersey and attended River Edge Junior High School and Hackensack High School. He graduated from Rutgers University with honors in 1959, served as a captain in the United States Air Force, and in 1966 earned a master’s degree from Harvard University.

On July 1, 1967, Rich married Margaret “Peg” Johnston, beginning a matrimonial love affair that lasted 57 years. They lived, worked, and raised their three children—Fletcher, Ellen, and Chip—at St. Paul’s School in Concord, N.H. In 2003, when Rich retired, he and Peg moved to the New Hampshire seacoast where they

had first met when Rich was serving in the Strategic Air Command at Portsmouth’s Pease Air Force Base.

For 37 years, Rich taught, coached, and served in loco parentis to thousands of students at St. Paul’s School. He created numerous courses, chaired the history department, and coached hundreds of rowers on Turkey Pond, 10 of whom went on to row in the Olympics. Rich received many coaching awards, including “Rings of Gold” from The United States Olympic Committee in 2000.

While reviewing race strategy with a crew competing at Henley Royal Regatta, Coach Davis was asked by an athlete what they should do if anything went wrong during the race. His legendary reply: “Pull harder!” For 31 years, Rich shared his rowing wisdom as a contributor and board member of Rowing News, launched by his son, Chip.

At St. Paul’s, Rich counseled grieving students who had lost a parent. In retirement, he continued his service to

youth in similar situations through the Hope Project, based in Kittery, Maine.

Rich was a kind and beloved member of many communities. He served as an overseer of Portsmouth’s outdoor history museum, Strawberry Banke; worked with the Rye Historical Society; and volunteered at St. John’s Church, where a conversation with the Rev. Tim Rich about the educational needs of the region led to the founding of Seacoast Academy, a private middle school now called Heronfield Academy.

A loving husband, father, brother, and son, Rich is survived by his wife Peg, son J. Fletcher Davis, daughter Ellen Parish (Dan), son Chip Davis (Alison), brother Walton Davis (Fran Drago), and four grandchildren—Margaret, Ian, Ella, and Charlie.

Donations in memory of Rich Davis may be made to St. John’s Church in Portsmouth, N.H., or to the Alzheimer’s Association. CHIP DAVIS

THE U.S MEN’S FOUR WON GOLD, AND THE EIGHT CAPTURED BRONZE—AN IMPROVEMENT OVER ZERO MEDALS IN TOKYO BUT SHORT OF THE GOAL OF FOUR.

The U.S. men’s four led from the start and dictated the pace of the Olympic final, seizing control of an event Great Britain has owned since the days of Steve Redgrave. The U.S hadn’t won Olympic gold in the event since 1960, but on the warm waters of Varies-sur-Marne, Nick Mead, Justin Best, Michael Grady, and Liam Corrigan raced to victory, reestablishing American rowing glory at the Olympic Games. Corrigan, who stroked the four, credited the continuity of rowing together.

“The last five years since 2019 in different boats and pairs with each other, against each other—there’s so much trust that’s been developed in that amount of time you feel like one unit. It doesn’t feel like four people, it feels like one boat.”

“One unique thing about this lineup and this crew is we’ve been together for so long relative to other American crews in the past,” said bowman Nick Mead. “We’ve been rowing together now for about a year and training together for five or six years, so that’s a huge advantage for us.”

“One of the things with the men’s four, specifically, was getting out of their comfort zone,” said head men’s sweep coach Casey Galvanek, who selected both the four and the eight and was the boat coach for the four, working with them over the past two years.

“We put a lineup together and then I would ask them to make changes, and it was uncomfortable. They said, ‘It doesn’t feel good.’ I know it doesn’t feel good. We’ve got to give up the short-term feel for the long-term success, which they clearly understood. They decided they would do that, and that’s where I think part of the success came from.”

Contributing to that success were the clubs that supported and trained the athletes before they came together for the seven months leading up the Games.

“Three of us are fully from CRC [California Rowing Club], and they’ve been hugely supportive,” Corrigan said. “The clubs are a big part of it for one portion of the year.”

“NYAC has been hugely supportive of me,” echoed Mead. “Helping me both train in New York City, then also helping send me to the fall speed order and out to California to do some rows with them.

“One of the huge advantages of Josy’s program is that we’re all on the same training program throughout the country, so I might be in New York and they might be in Oakland, but on Tuesday morning we’re doing the same workout. So when we come together as a big team, it’s an easier confluence, having all done the same training.”

Previous page: Liam Corrigan, Michael Grady, Justin Best, and Nick Mead celebrate at the Vaires-sur-Marne Nautical Stadium.

This page: The eight of Rielly Milne, Pieter Quinton, Evan Olson, Peter Chatain, Chris Carlson, Clark Dean, Christian Tabash, Nick Rusher, and Henry Hollingsworth won the bronze medal, the U.S. men’s first medal in the event since 2008. “A lot of those guys are really young,” said head men’s sweep coach Casey Galvanek, “So, hopefully they come back. There’s a lot of talent in the boat.”

The Dutch men’s quad, perhaps the best ever, won the first rowing gold medal of the Paris Games, sculling almost flawlessly, leading from start to finish, and winning the Olympic final by open water.

By nomination of the medal-winning athletes, the United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee (USOPC) awarded Galvanek, Kris Korzeniowski, Mike Teti, and Tim McLaren the Order of Ikkos in recognition of their instrumental support of the crew.

Two days after the four’s victory—the Olympic regatta spanned eight days, with four days of finals—the U.S men’s eight delivered a medal-winning performance, winning bronze and earning the first Olympic medal in the event for the U.S. since 2008 after three straight fourth-place Olympic finishes.

“It’s been a childhood dream of mine growing up, seeing Olympic paraphernalia from Seoul and Barcelona,” said two-seat Nick Rusher, whose parents both rowed in the Olympics. “Just seeing my parents in the stands, cheering me on, when I got my medal, it’s the proudest moment of my life.”

“We worked really hard looking at which athletes would be best in each boat,” said Galvanek. “The word prioritize gets thrown around a lot, but we were trying to prioritize the speed of each boat.”

Once Galvanek selected the crew (rather than the next eight fastest guys after the four) that would be the eight, Washington coach Michael Callahan coached the boat, which included four Washington athletes and still needed to qualify for the Games in May.

“There’s a couple of guiding principles about this campaign,” said Callahan, who noted that he’d never worked with such a detail-focused and determined crew, “and we’ve been talking a lot about what we’re going to do this whole week.”

“That crew came in with the highest of expectations, and a bronze medal is a great accomplishment,” said Galvanek. “It’s an Olympic medal; it’s pretty fantastic.”

The USOPC awarded Callahan the Order of Ikkos as well.

Defending Olympic champions in the eight, the Canadian women won silver, outlasting Great Britain in the race behind Romania, which won by open water. All eight Romanian women doubled up at the Paris Olympics, winning silver in the double and pair, and finishing fourth in the four.

Only three nations, excluding Romania, won more Olympic rowing medals than the Romanian women’s eight: The Netherlands (eight, including

four gold), Great Britain (eight, including three gold), and New Zealand (four, one gold). Romania also won gold in the men’s double and silver in the lightweight women’s double for five medals total.

The gold medal of the men’s marked the first Olympic medal of any color for the U.S. since getting shut out in Tokyo and the first time a U.S. National Team senior crew has been first across the line since the 2019 World Rowing Championships.

Besides that gold and the bronze of the men’s eight, there was plenty of disappointment among the other 10 U.S. boats, especially for the women’s crews. The new pair of Jess Thoennes and Azja Czajkowski, formed for April’s Olympic trials, mounted a brave sprint to nip Lithuania by three one-hundredths of a second for fourth place—the best finish of the U.S. women, who qualified for every event for the fifth Olympics in a row.

“Coming from Tokyo, something that we really wanted to emphasize was the culture and how we lifted each other up,” said Thoeness. “Everybody has done a very nice job of contributing and adding to the positive energy.”

The U.S. women’s eight, selected with the four as a group of 12 by USRowing’s head women’s sweep coach Jesse Foglia, finished fifth, more than seven seconds behind Romania. The women’s eight was two-plus seconds out of the medals, a further step back from the Tokyo result. The four finished fifth, an improvement over Tokyo’s seventh place.

“Both Jesse Foglia and Josy [Verdonkschot] have been absolutely amazing in creating a structure,” said Regina Salmons, of the eight. “The team of girls—both the team that is here and the team that’s been training the last three years, all the women that we’re pulling for back at home—have been so positive, and the vibes have been really good.”

“We all learned a lot because for all of us it was our first Games,” said Emily Kallfelz, bow seat of the four that finished fifth in the A final. “It’s a different caliber out there. Coming off a world championship, you think you know, but it’s definitely a different ball game.”

Sophia Vitas and Kristi Wagner experienced how different the Olympics can be. After winning World Rowing Cup II in Lucerne in May, the U.S. double entered the Games as the top seed but struggled through their heat and semifinal.

“They didn’t go straight, so they just couldn’t deliver on the power they would be able to deliver normally,” said Verdonkschot after the semi. (Isabelle Jacobs coaches the double.) “It’s very unfortunate for them, because I think they’re much better than this.”

After their third-place finish in the B final for ninth place overall, Wagner said, “It’s frustrating when you have all the pieces, and they don’t come together, and there’s no explanation. But I don’t think we would do anything differently. We did everything we could have done. We didn’t give up. We raced till the last stroke.

“Sometimes it’s not a medal, it’s not a win.”

Olympic lightweight rowing came to an end at these Games, the only rowing events ever to feature an African gold medal (South Africa’s lightweight men’s four at London 2012) and the closest racing ever (less than a second from gold to fifth in the women’s lightweight double in Tokyo). But the International Olympic Committee wanted to eliminate weightclass events outside of combat sports, and World Rowing acquiesced, getting Beach Sprints into the Olympic program for LA28 as a consolation prize.

Ireland’s Fintan McCarthy and Paul O’Donovan put the men’s lightweight doubles in the history books with a commanding gold-medal performance, as did Great Britain’s Emily Craig and Imogen Grant. The Brit duo concluded an undefeated Olympiad after finishing half a second out of gold, but in fourth place, in Tokyo. Right behind them was the U.S. crew of Molly Reckford and Michelle Sechser, who were less than a tenth of second off the Brits at last year’s Varese stop of the World Rowing Cup. But at these Games, the U.S. crew finished sixth.

“We knew it was going to be hard,” said bow seat Reckford. “We gave it all in that first 1K to stay with the pack, but you pay for that. It meant we couldn’t get to that final gear. These women are fast.”

Canada’s lightweight double of Jill Moffatt and Jennifer Casson, the only other Canadian crew besides the women’s eight to qualify for the Olympics, finished second in the B final of the women’s lightweight double for eighth place overall.

In the men’s double, Ben Davison and Sorin Koszyk were in the thick of the race for medals in the A final, going as fast as eventual winner Romania across the 1,000-meter mark and staying in third

Martin and Valent Sinkovic won the men’s pair on the last stroke of the race, sprinting from fifth place in the last 500, to become the most decorated summer Olympians in Croatia’s history. The brothers are one of five sets of rowing siblings to win medals at the Paris Games.

through the middle of the race. But they had spent all that they had to stay in it and were passed by the Irish in the final 500 to finish fourth.

“We needed to put ourselves in a position to be in it in the sprint,” said Davison after the race. “We lost it in that last minute, unfortunately, but I have no regrets.”

“I’m gonna keep training” was Koszyk’s response to “What’s next?”

“I gotta take care of my back this next year and then keep training.”

Kara Kohler, a collegiate rowing walkon at Cal, continued her long Olympic career—she won a bronze in the quad at London 2012—with an appearance in the A final in her third Games, where she finished fifth.

Five-time Olympian Emma Twigg, 37, continued to be the only woman who can push her friend, Karolien Florijn, the 25-year old Dutch phenom who won gold.

Twigg was “super proud that I could go out there and execute when it counted, to have the race of my life. And being there with Karolien, who I’ve been chasing

for the last three years, was equally special, and sharing it with her as well was pretty cool. We’ve formed an awesome friendship over the last three years.”

Lithuania’s Viktorija Senkute, who rowed at the University of Central Florida and has epilepsy, outsprinted Australia’s Tara Rigney for the bronze.

“It’s not a limitation at all,” said Senkute, after winning Lithuania’s first medal of the Games. “People who have epilepsy are normal, regular people and they win Olympic medals.”

U.S. men’s single sculler Jacob Plihal (13th), the men’s pair of Dartmouth’s Billy Bender and Oliver Bubb (10th), and the women’s quad of Grace Joyce, Emily Delleman, Teal Cohen, and Lauren O’Connor (ninth) all turned in performances that constituted a U.S improvement over Tokyo.

They also raced in events with historic performances for the winners: Oli Zeidler set a new Olympic best time in a semifinal of the men’s single before winning the gold. Croatia’s Sinkovic brothers stormed from midfield to win the pair gold—their

third—on the last stroke, as did Great Britain’s quad.

As first-time Olympians, the U.S. rowers are like law-school students going up against Supreme Court justices. The old U.S. rowing approach to elite rowing, in which top collegiate rowers treat it like grad school—two or three years of training and competing after graduating before getting on with their lives—doesn’t work in the 21st century against top Olympic rowers.

“They train professionally every day since the first day they enter the training center,” said Verdonkschot of the European competition. “And they do study, but they do not have jobs to earn their living.

“It’s also the conscious decision of an athlete to put their life on hold for four to eight or 12 years. That’s a culture people have to understand and accept. If you want results, you have to invest more.”

The U.S. qualified 12 crews for the 14 Olympic events, tied with Romania for the most of any nation, and eight U.S. boats advanced to grand finals, proving the

“We have enough energy for both boats. The energy for the eight, it’s like a separate room of our body,” said Romania’s Maria Lehaci, who won gold with the eight and finished fourth in the four. Every oarswoman from the eight raced two events, with the double and pair each winning silver. “We mostly train in the pair. We have just a few kilometers in the eight. We have the same coach, and we all have the same technique and tactic. And it’s easy for us in the eight.”

Conditions at the Vaires-sur-Marne Nautical Stadium can be rough and windy, but for the Olympics, conditions were good for the duration of the eight-day regatta. “I don’t care about the lake,” said Romania’s Marian Florian Enache, who stroked the men’s double with Andrei Sebastian Cornea to Olympic gold. “I’m doing my job anyway, in any kind of condition.”

U.S. has the athletes who did the training to compete at the Olympics. But they weren’t prepared properly to perform at the highest level of the sport against the best in the world.

“We’ve made a lot of progress,” said Verdonkschot, who began coaching for USRowing in 2022 after the national governing body wasted more than a year squabbling before preparing for Paris. “Looking at how far we got, I’m proud of the job I did.

“We are very close but we need to make the final step, not just to train in the events and be competitive in the events but also to medal in the events.”

That will require making some changes, including following “what the rest are doing.”

“They come back in October and they continue,” said Verdonkschot. “In that respect we need to find clever solutions.”

U.S. rowers have shown that they have the fitness and skill to compete on the Olympic level. But to win medals at LA28, they’ll need to continue developing and gaining international racing experience. More than a World Cup here and a Henley trip there, this year’s Olympians—plus those who weren’t on this squad—need dozens of repetitions of lining up and racing against the world’s best.

With World Rowing showing no signs of expanding elite rowing events beyond Europe, that means joining the Kiwis and Aussies and racing in Europe every spring and summer for the next four years. USRowing has generated the revenue to afford that, but the current board and staff leadership have yet to make it happen.

Preparing for LA28 the same way USRowing prepared for Paris will produce the same result: two medals. That is certainly better than none but too few for a nation with the resources and tradition of rowing excellence like the United States.

Emily Craig and Imogen Grant raced in the closest race in Olympic rowing history, the Tokyo Games final of the women’s lightweight double, when the top five crews finished within a single second, and the British duo missed a medal by one one-hundredth of a second. They kept at it, going undefeated for the Olympic cycle leading up to Paris, and won the last Olympic lightweight rowing gold medal to be awarded. “This was the only result left for us to achieve, and we did it,” said Grant.

World Rowing operates elite-level rowing in the same old Eurocentric way the sport has functioned since the turn of the millennium.

World Rowing is in trouble.

The international governing body of the sport, formerly known as FISA, relies almost entirely on financial support from the International Olympic Committee and faces the same challenges of rising costs, waning relevancy, and shrinking revenue that’s affecting everything else in the sportsbusiness landscape—from the NFL to cornhole.

Competing for attention—and the sponsorship, attendance, and broadcastrights fees that come with it—has proven “very difficult, very competitive” said the president of World Rowing, Jean-Christophe Rolland, at the Olympics.

Earlier this year, Executive Director Vincent Gaillard stated frankly that World Rowing is “not in a good situation” and “going in the wrong direction.”

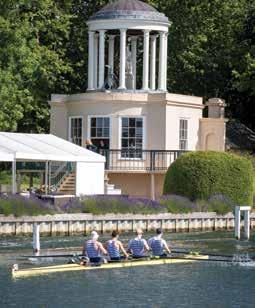

Rowing is flourishing in America, with record entries and crowds at the heads of the Charles, Schuylkill, and Hooch in the fall and ACRA, IRA, and Youth National championships in the spring. Rowing succeeds also when presented well, as at Henley Royal Regatta, which attracted record entries, 300,000 spectators, and almost 100,000 viewers per day over its YouTube livestream this year.

Those numbers approach Formula 1’s average U.S. viewership on ESPN of 1.1 million per race. Last year’s Las Vegas Grand Prix drew 315,000 spectators over four days.

But World Rowing operates elite-level rowing in the same old Eurocentric way the sport has functioned since the turn of the millennium, with World Rowing Cups that

almost no one attends (except in Lucerne), World Rowing Championships always in Europe except for the post-Olympic year, and regatta programs that could be held in a few days stretched over more than a week. It’s expensive and unproductive for all but the small handful of European national teams that dominate the medal tables. European countries won 70 of the 87 medals awarded at last year’s Worlds in Belgrade. In Paris, three European countries—The Netherlands, Great Britain, and Romania— won nine of the 14 events.

Pressure to reduce costs and the number of athletes has reduced Olympic rowing events to fields that are farcically small. Only seven boats qualify for the eights, and only nine for the fours and quads. With eight-lane courses the international standard, heats and semifinals are practically unnecessary. The current Olympic program could be run in a long weekend by the volunteers who make Canadian Henley such a success.

But people love rowing, as evidenced by ticket sales of 97 percent in Paris, where nearly 20,000 cheering fans filled the stands every day. Swimming, track & field, and cycling capture public attention with stars winning multiple medals every Games. Romania’s women’s eight proved it can be done in rowing, winning two silvers and a gold.

Why not run all the small-boat events the first four days of the Olympics and Worlds and big boats the last four (or fewer) days to facilitate it? Nations, instead of individual boats, could qualify for the Games, and contest all the rowing events—

bring back the coxed four and pair!—with a team of 20 men and women racing as many events as possible.

The sport could certainly use a Michael Phelps or Simone Biles. Twenty national teams of 20 rowers is only 400 athletes, fewer than rowing’s current allotment of 502, allowing plenty of room for international inclusion spots.

The Head of the Charles added events for pairs, and elite international crews already compete in it and Henley, so why not make popular regattas like those part of the World Rowing Cup series?

European national teams already spend on remote training camps, so why not have them in places like Aiken County, South Carolina, and Oak Ridge, Tenn., in the lead-up to an early-spring World Rowing Cup at Nathan Benderson Park in Sarasota?

The choice between Florida and central Europe in early spring is an easy one. World Rowing could join the rowing party where it’s already rocking instead of continuing the failing practice of expecting the world to come to them.

To its credit, World Rowing has hired outside consultants to study the problem and offer possible solutions. Meanwhile, its leaders point to indoor rowing, coastal rowing, and e-sports as “exciting” new branches of the sport, but participation and attention on the same level as real rowing have yet to materialize.

The leaders of elite-level rowing have their heads and hearts in the right places. They’re just slow.

And slow doesn’t succeed in rowing.

Hip mobility, measuring technology, and training in the Florida heat were keys to Olympic gold.

The Olympic gold won by the U.S. men’s four was the product of more than just four great collegiate oarsmen rowing together for several years. Coach Casey Galvanek used his sharp eye, available technology, and sales skills to get already successful athletes to make the little changes that reaped the ultimate result.

The loose, relaxed length evident in the four’s rowing was “the number-one thing we worked on at first,” said Galvanek after the Olympic victory. “It caused a little stress between us.”

“A lot of it was hip mobility,” said Galvanek. “They’re sitting in chairs a lot more. Work is in a chair. They’re sitting at a computer and in the classroom. Over the years, their mobility is less and less because they’re locked in place and they’re not stretching. Every 10 degrees of hip angle gives you a certain amount of length in the stroke.”

Galvanek identified hip mobility as a key early, talked to the strength and conditioning coach, and the next day they were working on it.

“They committed to it, and we saw the results right away. And then we just kept working on it, keeping a strong but more usable position that gives you more length and duration in the water. It changes the drive rhythm.”

Galvanek and his fellow Olympic coaches, including Brian de Regt and Michael Callahan, used the Peach system that measure forces, angles, and speeds in the shell while rowing. The technology showed them what they couldn’t see with their eyes.

“One degree here and there is pretty tough to see,” said Galvanek. “A little bit of timing differences are really hard to see.”

The recorded measurements also enabled Galvanek to sell the changes to the oarsmen, even if they didn’t feel right.

“I would show them reports, ‘Here’s a video of you doing it before I said, and here’s a video after I said, and then when you went back.’ And they can see it in the data. So it does help them agree and be convinced a bit more than just saying, ‘Hey, this is what I’m looking for.’

“If you look at the video of the boat

from when we first started working together for World Cup II last year till now, it looks like a wholly different boat.“

After more than 20 years of coaching in Florida, the Sarasota Crew CEO (like Washington’s Callahan, Galvanek receives the majority of his compensation from outside USRowing) had his crew ready for the heat at the Paris Olympics.

“One of the other things we worked on a lot was not avoiding the heat in training. It’s not like it’s magic. But just being accustomed to it is a big help.”

Again, Galvanek wanted his crew to eschew comfort for improvement by meeting the challenge of hot conditions in training.

“I asked them if they would do that, and they said yes. And so for the past two years, any time it was hot, we didn’t shy away from it.”

The preparations paid off in the Olympic final, as the U.S. men won gold in the four for the first time since 1960.

“It’s an incredible experience,” said Galvanek after the biggest win of his career. “I don’t know if there could be anything better.”

Left: “We started off in 2016 and the last three years in pairs,” said The Netherlands’ bowseat Ymkje Clevering of the years of experience she and Veronique Meester have rowing together. “We joined actually the national team by winning the national championships in the pair.” They won the Olympic final by more than four seconds over Romania. Australia won the bronze, and the U.S. finished fourth.

Top: The U.S. men’s four of Liam Corrigan, Michael Grady, Justin Best, and Nick Mead lauded their coach, Casey Galvanek. “We four had the competitiveness and the willpower to do whatever it takes,” said Grady. “But we didn’t necessarily know what that is. And he came in and guided us. Casey’s a guy who works a little bit in the background. We learned the right professional mentality, how to do smart training, how to recover, how to take really long, really effective, simple strokes. Casey had a very data-driven approach. He rigs the boat well. He keeps it really simple for the athletes. He makes the focus on training hard, but in a very smart way.”

The phenomenal single sculler is done with flat-water rowing and looking forward to Coastal Worlds, retiring, and rowing “for the sake of loving what I do.”

Emma Twigg, New Zealand’s fivetime Olympian, will race again in the World Rowing Coastal Championships and World Rowing Beach Sprint Finals after the flat-water season.

In 2022, Twigg won the coastal women’s solo CW1x class and finished second in the mixed quadruple sculls at the Coastal Worlds in Saundersfoot, Wales, a month after the World Rowing Championships.

Twigg won silver in the women’s single at the Paris Olympics to go with her gold from Tokyo.

“Tokyo for me was redemption of my belief that I could be an Olympic champion and that I always had it in me and that the results in London and Rio [fourth at both] were not me,” said Twigg, who was the

only sculler to challenge Olympic champion Karolien Florijn in the final, closing the gap in the third 500 before being outsprinted to the finish.

“That was the plan. I executed everything up until the last 250, when I ran out of gas. I left it out there and didn’t quite make it, but that’s sport, and I’m happy.”

Twigg, 37, is done with elite-level flatwater racing and will turn now to coastal rowing—for fun.

“I’m going to go and do the Coastal Worlds but I can safely say that my flatwater career is done. Coastal is an amazing sport but it’s probably not an old ladies’ game, so yeah, I’m just going to enjoy retirement and row for the sake of loving what I do.”

Five-time Olympian Emma Twigg trained apart from her young son during the Games, but brought another medal home.

“Hopefully one day he’ll look back and he’ll be able to put on mum’s medals and be really proud of what I’ve done, and hopefully he feels like he can chase his dreams, too.”

SINGLE SCULLER MAJDOULINE EL ALLAOUI IS A CHAMPION BACK HOME IN MOROCCO, BUT LIKE MANY AFRICAN ROWERS, SHE STRUGGLED TO COMPETE IN PARIS. HER STORY OF GRIT AND RESOLVE SHOWS THE CONTINENT’S UNTAPPED POTENTIAL IN THE SPORT.

STORY BY THOMAS EARL PHOTOS BY JULIA KOWACIC

When Majdouline El Allaoui glided to the finish line in the second heat of the women’s single-scull heat in Paris, she didn’t feel like much of an Olympian. The 23-yearold finished 53 seconds—nearly a minute—behind the victorious Karolien Florijn of The Netherlands. The sympathy applause pained her.

“It was not easy at all,” she said that evening. “I’ll try to do better tomorrow.”

After the race, El Allaoui trained, had a massage, and met with her mental coach. Despite facing her repechage at 9:24 the next morning, she didn’t get around to an ice bath and dinner until after 11 p.m.

It was only her second time using a competition-standard rowing shell—a Filippi purchased after she was qualified by the Moroccan Olympic Committee. Despite being a six-time Moroccan champion, she lacked experience rowing at the top level, and it showed in her performance. Even the Parisian weather was a surprise.

“It was really cold,” she said. “I didn’t expect it.”

Florijn is nine inches taller and 36 pounds heavier than El Allaoui. And whereas Florijn is the daughter of two Olympic rowers, El Allaoui’s parents are divorced, a rare and difficult circumstance in conservative Morocco. Her father wasn’t around much after the split, and her mother couldn’t get a passport to watch her in Paris.

Given her circumstances, coming within a minute of the Dutch Olympic medalist was a triumph, one that warrants a celebration of El Allaoui’s defiant journey to the Games. In many ways, she epitomizes the creed of Baron Pierre de Coubertin, who is credited with launching the modern Olympics: “The important thing in the Olympic Games is not winning but taking part; the essential thing in life is not conquering but fighting well.”

Her accomplishment also should persuade the rowing community to protect and preserve the 32-field single-sculls event. As the only category with more than 16 boats competing, single sculls had a distinctly global feel, owing to the breadth of countries represented. The presence of athletes from emerging rowing nations reminded viewers that there are more than just medals at stake in the Olympics.

After all, on the start line, the two women didn’t look so different. From 2,000 meters away, they both looked like Olympians.

It was difficult to picture El Allaoui, as she sipped orange juice in a marina-side cafe in Salé, Morocco, two days before she left for Paris, lining up in an Olympic regatta.

“I’m a little bit stressed, to be honest,” El Allaoui sighed, smiling. “When you see the boats, you’ll say ‘How did you qualify!’”

She glanced down as she rearranged the ice cubes in her glass with a straw. Overhearing her talk, you’d be forgiven for wondering if it was an upcoming college exam that was weighing on her mind.

“I’m not actually thinking about the podium,” El Allaoui admitted. She was realistic about her chances against the likes of Florijn and her rowing hero, Emma Twigg. But she also recognized that showing well in Paris could make a big difference for Moroccan rowing.

“The little girls who train every day, expecting nothing,” she said. Her voice rose as she gestured to the rowing club where she trains. “I’m doing it for them.”

Club Royal Marine, the home of the Moroccan rowing team, consists of a trailer of singles, an inflatable dinghy, and a gazebo providing shade to seven rusting Concept2 ergs. Three curtains have been fashioned into changing rooms at the side of the gazebo, and a restroom is provided by a friendly cafe owner a hundred yards away. Only three of the shells are serviceable, two with the help of duct tape. The rest are kept in the hope, rather than expectation, that they might be repaired someday.

A mix of 10 to 15 junior and senior athletes turns out usually for national-team training sessions, which take place on the Bouregreg River, in the shadow of Salé’s middle-class marina and Rabat’s 17thcentury Andalusian walls. The river reflects the emergence of modern Morocco, passing the newly constructed Mohammed VI tower, the third tallest building in Africa, before partitioning Rabat and Salé and emptying into the Atlantic.

Since the club has only three functional boats, half the rowers train on the ergs while the rest go out on the Zodiac with the coach, taking turns swapping in and out of the working shells.

This routine means practice takes three times as long as it should, but with five or six athletes huddling in the Zodiac, there’s plenty of joking around to pass the time. Comic relief sweetens the bitterness of equipment-caused frustrations.

When African competitions bring the group to the Tunisian Club Nautique, the so-called home of African rowing, the Moroccan team marvels at the facilities on Lake Tunis. Other African squads notice the Moroccans for their spirit.

“We just have fun together, laughing at each other,” El Allaoui said. “We are just like a little family.”

It was her parents’ divorce that turned El Allaoui into a sportswoman. Their separation forced her mother, Nawal Daoudi, to move back to Oujda, her ancestral home 300 miles away in eastern Morocco. Daoudi decided that her daughter would benefit from better schooling if she remained in Rabat, so from the age of five El Allaoui lived with Daoudi’s sister, Samia, in a suburb outside the capital. El Allaoui saw her mother only sporadically, when Daoudi could make the nine-hour train journey to the coast.

El Allaoui discovered athletics through school and found that sport distracted her from the loneliness and stigma of coming from a broken home. She showed potential in the 400-meter hurdles and tae kwon do.

“I did athletics as a way to not think,” she said. “I became obsessed with sport.”

It was Daoudi’s brother, Abdellatif, who brought El Allaoui to Club Royal Marine for the first time. Abdellatif was born in Oujda with his siblings but was adopted as a boy by a Belgian family as his family struggled to make ends meet. He grew up as Abel in Belgium before moving back to Morocco in 2013 and opening Abel Restaurant Belge, a Belgian restaurant in Salé Marina. He got to know the coaches at Club Royal Marine from living and working around the marina and brought his niece to the boat club for the first time in 2016 after a fight with some other girls left El Allaoui unable to continue with athletics.

Within a month, the 15-year-old was selected for the women’s national team, and within a year, El Allaoui was crowned Moroccan champion for the first time.

El Allaoui qualified for the Paris Olympics at the World Rowing African Olympic and Paralympic qualifier in

Tunisia in October 2023, winning her B final with a two-kilometer time of 8:34:46. Her qualification depended on the disqualification of a faster athlete from the A final, Sarra Zameli of Tunisia, based on World Rowing rules.

Of the 502 rowers who competed at the Paris Olympic Games, 18 represented African countries. That amounted to 15 African boats, with 12 qualifying through the single-sculls category.

Among these African athletes, El Allaoui’s story isn’t unique. Akoko Komlanvi grew up around Lake Togo without training facilities or proper equipment. The Togolese athlete relocated to Tunisia to benefit from technical support, proper training, and international competition, with the assistance of an Olympic Solidarity Scholarship.

“When I was chosen for the Olympic Solidarity program, it was a great joy for me and my family,” Komlanvi told the International Olympic Committee. “My housing, recovery, travel, everything is paid for by the scholarship, and it has also allowed me to take part in many international competitions.”

Six of the 18 African athletes represented were white: three from South Africa, and three who rowed at colleges in the United States. Kathleen Noble, the daughter of Irish missionaries who was raised in Uganda, credited representing the country with consolidating her Ugandan identity. She first represented her country as a swimmer, before walking onto the Princeton rowing team as a sophomore.

“Why’d you show me this? Do you want me to cry?” El Allaoui teased when I showed her pictures of an Ivy League boathouse. A week before the Olympics, she had never heard of Henley Royal Regatta or

the Oxford-Cambridge Boat Race.

“We don’t do that here,” she smiled, as she studied a photograph of the crew of a women’s eight at Henley hoisting oars above their blazers.

While rowing is a pathway to education for many athletes in the U.S., El Allaoui’s pursuit of the sport cost her a high-school diploma. After missing a month of her final year to attend an international competition in Tunisia, her high school prohibited her from taking the baccalaureate exam. So she dropped out and moved in with Abdellatif to live as close as possible to the rowing club and began training twice a day, every day, between coaching kids, working behind the desk at her gym, and waiting tables at her uncle’s restaurant.

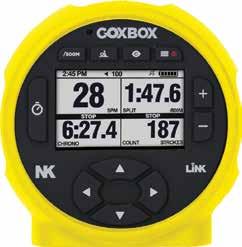

She was awarded a stipend by the Moroccan Olympic Committee after qualifying, which enabled her to cut back hours and orient her time around training. It also funded the purchase of an NK SpeedCoach GPS, which remains an object of great fascination to her teammates.

There was nothing noteworthy about El Allaoui’s final practice before leaving for Paris, because her training had not been designed to build to the Olympics. The team begins each week with distance training on Monday. Wednesday is a blend of strong and long, and her final session was a 5 x 500-meter sprint, as it is most Fridays.

A good amount of time was wasted adjusting and readjusting foot stretchers. Dodging jet skis and commercial traffic created another distraction.

El Allaoui stopped after her fourth sprint, complaining of a mild cramp in her hamstring. She climbed out of the scull and displaced some teammates so she could stretch out across the width of the Zodiac.

“I feel good,” she said, flashing a smile

that was betrayed by the concern in her eyes.

Only after everyone had their turn on the water and the Zodiac headed back to the marina did anyone mention the Olympics.

“We are so proud of her,” said Iliass Chafik, a 19-year-old on the men’s national team and El Allaoui’s cousin on her father’s side. “Because of her, rowing in Morocco will be famous.”

El Allaoui’s repechage race on July 28 played out almost identically to her heat the previous day. She broke ahead of the pack with a stroke rate of 48 in the initial moments, but the field caught up within 300 meters. By the halfway mark, she was 18 seconds behind the leader, Alejandra Alonso Alderete of Paraguay. Her inexperience was evident.

Her E/F semifinal, which featured three African scullers, was a similar story, with El Allaoui falling several lengths behind after 500 meters. At the halfway mark, she showed considerable grit by clawing back to within a length and a half of the thirdplace rower, Nicaraguan Evidelia Gonzalez Jarquin. But the gap reverted to three lengths by the time the pair reached the finish line.

“A lot of these women are racing normally at world championships—like El Allaoui, the Moroccan sculler—in the lightweight category,” said Olympic gold medalist Martin Cross as he called the race on Peacock for U.S. viewers. “They’re not big tall women you would expect to see in the quarterfinals going for places in the A and B semifinals.”

Cross was astute in making note of El Allaoui’s unusual size. At just under five feet, four inches, she is five inches shorter than the average female single sculler who competed at the Olympics and two inches shorter than the average lightweight

“I didn’t do well at all. I’m going to work so hard so that next time I do better,” vowed Majdouline El Allaoui. “I want to show that short girls can do it, that African girls can do it.”

women’s double sculler. While she has a suitable build for lightweight competition, she had neither the teammates nor access to double scull boats to train for the lightweight double sculls, the only Olympic category for lightweight rowers.

El Allaoui’s first thought after meeting Emma Twigg at the 2022 Coastal Championships in Saundersfoot, Wales, was to marvel at her stature.

“She’s a really big woman,” El Allaoui laughed, elongating the adverb as she rolled back her head.

After so many years at the top of Moroccan rowing, El Allaoui didn’t know whether she could get better. She entered the Welsh competition debating whether to try for LA 2028 if she should make it to Paris or whether she should give up on rowing and begin a new life.

Twigg’s career has been a model of longevity and passion for the sport. Witnessing her approach to rowing had a profound impact on El Allaoui.

“Why won’t I qualify two, three, four, or five times for the Olympic Games? Why won’t I someday bring home a medal?” she asked rhetorically. “That’s why I’m following this path. Her path.”

Despite practicing in coastal shells that are handmade in Morocco, El Allaoui and her mixed-doubles partner, Ibrahim Mraghi, posted the fastest Beach Sprint time in Africa at the 2023 African Beach Games. This qualified them for the canceled World Beach Games, which would have been held in Bali, Indonesia, that same year.

With the Beach Sprints making their debut at LA 2028, the pair hopes to recreate that performance next time out to secure a place.

“We are going to train hard for it,” El Allaoui said. “I’m pretty sure that we will qualify.”

Mraghi lives and trains in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates. El Allaoui has come to accept, reluctantly, that her dreams require her to move abroad, too.

She has World Rowing coaching qualifications, which she hopes will land her a coaching job and a visa to support a professional training regimen. She also hopes to get her high-school diploma through Morocco’s free baccalaureate program, which is commonly used by prisoners to accelerate their rehabilitation by qualifying them for work and further study.

Discussing where to go next has become a favorite way to pass time on the Zodiac. Everyone shares their opinions about different countries, which, since English comprehension in Morocco is low, originate from French and Arabic media as well as personal experience.

“Poland is an amazing country,” El Allaoui asserted. “I was there, and it’s not expensive.”

The team’s chief perception of the United States is that it’s extremely pricey, and the Moroccans were unaware of rowing scholarships. Although El Allaoui is now an Olympic rower, she’s never been contacted by a U.S. college coach.

“France is expensive,” offered Chafik. “It’s a racist and very expensive country.”

El Allaoui lined up against Akoko Komlanvi, the Togolese recipient of the Olympic Solidarity Scholarship, on Aug. 2 in the Single Sculls Final F.

With only two boats in the race, the final made for an intimate contest. The pair knew each other well, since Moroccan training camps tend to take place at Lake Tunis, where Komlanvi is now based.

“She’s such a good athlete, and her muscles are so strong,” El Allaoui said. “If she can grow her confidence, she’ll be a champion.”

El Allaoui pulled into clear water early, settling into a rhythm of 30 strokes per minute. Komlanvi closed the gap to

half a length in the second 500 meters, outstroking El Allaoui by five strokes a minute, but El Allaoui’s longer strokes took command of the race eventually, and she won the final convincingly, posting a time of 8:20:81, her fastest of the competition by almost 10 seconds.

Nevertheless, the result meant she finished 31 of the 32 female single scullers competing in Paris.

As she got off the water, she was deflated.

“I didn’t do well at all. I’m going to work so hard so that next time I do better,” she vowed. “I want to show that short girls can do it, that African girls can do it.”

The disappointment was exacerbated by comments on social media suggesting that she wasn’t worth sending to the Olympics and congratulating her sarcastically for managing not to capsize.

Criticism from within the sport she can shoulder; rarely is it more severe than the criticism to which she subjects herself. Negativity from outside the sport, however, can be a more bitter pill.

“They don’t know me,” she said, her voice rising for emphasis. “And they don’t know rowing.”

Many of the rowing enthusiasts in attendance towered over El Allaoui as she meandered behind the grandstand after her race. Fans nudged elbows and pointed discreetly as their heroes walked by, while El Allaoui went unnoticed.

Until a man ran up behind her and tapped her on the shoulder.

“Excuse me,” he said. “I’m Moroccan. Would you mind taking a photo with me?”

She stood in stunned silence for a moment before posing for the picture.

“Wow,” she said afterward, her eyes widening. “I’ve never felt anything like that before.”

Smaller skegs or fins don’t always make a boat faster.

Fins on our boats make taking a boat on and off the racks more difficult, require special attention so they don’t hit the dock when we launch, and, last but not least, cause resistance in the water. So it’s no wonder we want to get rid of them—until we lose them because we hit a log we didn’t see. Then we realize how well they serve us.

I remember a situation like this when we were in an eight a few years ago. The crew had done well in previous regattas, and we were preparing for the big race at the end of the summer sprint season. Because our experienced cox couldn’t make practice, one of the lightweights offered to step in and help.

All went well until the boat began swaying side to side suddenly and making long, violent turns, throwing off our rhythm, balance, and, of course, speed. I could see the coxswain’s desperate attempts to steer as I stroked the boat; she was moving erratically and pulling on the rudder lines frantically.

The poor volunteer coxswain lost her confidence quickly, and so we cut the practice short, went back to the boathouse, hauled the boat out of the water, and discovered…our fin was gone!

Even the best coxswain in the world can’t keep a boat straight without a fin, and so our replacement coxswain was redeemed.

We need fins to steer our boats, obviously, but why not make them smaller?

The advantages: less risk of bumping the fin in the racks or on the docks and less drag, which would make our boats faster.

It’s not that simple, however. If a fin is too small, the boat will not track well, and crosswinds will disturb its directional stability. Finless rowing requires more steering effort, which increases drag and decreases speed. The fin also helps balance and stabilize the boat; the larger the fin, the more stable the boat.

Because a smaller fin doesn’t always make a boat faster, what’s called for is compromise, tailored to the situation for which the fin is needed. A straight sprint

race requires a larger fin than a winding head race. A less experienced rower would benefit from a larger fin. A larger fin is useful also when racing on a sprint course known for its strong crosswinds. For all these reasons, it would be nice to have a boat design that allows fins to be changed easily.

The efficacy of a fin depends on two factors: depth and surface. Since surface area is the most important drag factor, boat designers like to make fins deeper, as reflected in all modern fin shapes. Hydrodynamically shaped fins also increase the function of a fin, but here, too, compromise is necessary. A thicker fin increases its efficiency, but also its resistance. In addition, such shapes can be achieved only with special plastics, which are more expensive than aluminum.

For boats used to train beginners, the choice of fin hardly matters, but for highly competitive crews, the right fin can make all the difference.

VOLKER NOLTE

Every opportunity to pass should be fun, so let that shine through in your coxing.

Head-racing season is upon us, and with it a new set of challenges to manage and skills to perfect. While it’s fun to focus on the perfect line down a course or the ideal angle to approach a bridge, it’s important to remember the basics, especially if you’re newer to head racing.

This fall, don’t take the humble skill of passing for granted. Any seasoned watcher of head races can tell you that a surprising variety of clashes and collisions is caused each year by coxswains and crews not executing a pass cleanly.

The foundational element of passing is understanding how your boat is traveling through the water—how fast and how predictably it moves and how easily it turns.

First, you need to assess how fast you’re approaching the boat ahead of you. To overtake cleanly, you need to anticipate both how quickly you’ll be able to overtake as well as where on the course the pass will occur so that you can account for any obstacles—buoys, boats, or the left-hand abutment of Weeks Bridge. You also need to know what kind of pressure that passed boat is going to be able to apply to you once you’re ahead of them.

As the overtaking boat, you get to

select the line you want. Make sure as you approach that you keep your bow pointed to the side you want to take. Once you’re a length and closing in, make the call to the coxswain in front of you to yield off the racing line, preferably using the team’s name. There’s a lot going on during races, so you might have to repeat yourself. Ensure that you’re projecting confidence to your rowers, even if the other coxswain doesn’t respond immediately.

Remember your earlier assessment of any potential obstacles? This is to ensure that you won’t make the mistake of asking the other coxswain to yield off the course or into a bridge. No matter how much you may want a particular line, the other boat can’t disappear into thin air. Leave enough room for the blades of both boats; clashes slow you down. If you’re passing around a turn, make sure you know your rudder and your rowers so that you can make your inside turn confidently. It’s always best to leave a margin for error between the boats in case your opponent’s turn is sharper or shallower than you anticipate.

If you’ve come off your preferred line to make the pass, make sure that your stern is clear of your competitor’s blades and bow before you pull back directly in front. Awareness of where your stern ends and how much it swings is more challenging in a bowloader, so this is a skill worth practicing if you’re coxing a four.

Once you’ve completed the pass and established yourself fully on the racing line you want, be sure to continue moving away from the boat behind you. Every opportunity to pass should be fun, so let that shine through in your coxing. Use that momentum to help keep up boat speed after you’ve completed the pass to shut the door firmly.

Sometimes in life you’re the passing boat and sometimes you’re the yielding boat. If you must yield, do it quickly, quietly, and with minimal disruption to your race plan or rhythm. Don’t let the speed of the boat fall off after the pass. Give your boat a goal and a focus, and provide the crew with the feedback and energy to reach that goal.

HANNAH WOODRUFF

A ROWER’S PARADISE in VERMONT On the GREEN RIVER RESERVOIR

9 Miles South of the Craftsbury Rowing Center and 14 Miles to Stowe, The Aspen of the East

The lake is 4 miles long, with 19 miles of undeveloped shoreline. The main body of the lake is 2,500 meters long and 300 meters wide. You can row 3 miles with only two, 45 degree turns, and never see a motor boat.

Each home is carefully crafted with pine floors and ceilings, and have their own kitchens. You can row in the morning, and see friends and family in the afternoon.

The total Living Area is 6,714 SF, all winterized and air conditioned. There are two heated, 2 car garages, a boat house, beach and barns

of a kind property offered at

Fall offers 10 weeks of water time to help athletes build fitness, row better, learn to compete, have fun, and prepare for spring racing.

Traditionally, the fall season is the “nontraditional” season for rowing. It’s a time when the serious spring racing feels distant and what racing occurs is head-style and less consequential. While the racing results may not be as important, the opportunity to prepare for the spring is hugely so. Used wisely, the fall season sets up a team for spring success.

As soon as the athletes get going in the fall, begin to establish team culture. Doing so constructs a foundation to build upon all year long. Some think of culture as a list of rules and procedures. This is a good start but ultimately limiting because rules can’t cover everything, nor are rules always enforceable.

Culture consists of values, not just policies. It’s about how teammates respect one another, their opponents, and the challenge of racing. Ben Hunt Davis, an Olympic gold medalist, distills “culture” to “Will it make the boat go faster?” However you define it, be sure to communicate it at the beginning of the year and reinforce it all year long.

The fall season allows for building a base of endurance focused on aerobic conditioning. This means lots of lowerintensity work (U1) that trains the body to utilize oxygen, build more capillaries, and become more efficient. Keep the rate low enough (less than 21strokes per minute) that the stroke requires some power and ratio. It’s wise to mix in about 15 percent of highintensity interval training (HIIT). While this is beneficial physiologically, it’s even more important for teaching athletes to pull harder. The value of learning to row harder can never be overstated.

Every fall, the temptation is to focus on head races and do lots of simulated races in practice at higher rates. Too much of this threshold training at the expense of basic endurance will handicap the aerobic development needed for spring racing. It can hinder rowers also from learning to row a long stroke. Be careful of achieving fall speed at the expense of spring success.

Lower-intensity rowing allows also for

more teaching of the rowing stroke. The fall is the best time for technical development. Take it slower and get it right. Teach everyone how you want them to row. Make sure each athlete knows how to take a stroke and move the boat. Better still, help them understand why. Total team understanding is achievable in the fall, even if perfect execution is lacking, but without first understanding, you’ll never get sustained execution.

The fall should be less intense and a time for more overt fun. Get athletes hooked on rowing so they’re willing to do the arduous winter training. Alternating between sweep and sculling and across different boat sizes

The fall should be less intense and a time for more overt fun. Get athletes hooked on rowing so they’re willing to do the arduous winter training.

will help. Cross training—team hikes, soccer games, water-polo matches, running races—all serve the dual purpose of general conditioning and having fun.

So too will internal competition. It’s fun to race, and athletes become better racers doing so. Train and teach them all week and set up squad racing at the end of the week. This is standard practice in many collegiate rowing programs, and whether called “YouPick-’Ems,” “PBR races,” “Friday Race Day,” or some other name, it generates terrific competition, good training, and great fun.

Programs that row in the fall typically have about 10 weeks of water time to work with. Used wisely, these weeks will help athletes build fitness, row better, learn to compete, have fun, and, most of all, set the team up for spring racing.

Come racing season, we all wish we had more time. That time exists in September, October, and November. BILL MANNING

At their annual meeting, sportsmedicine experts from around the world discussed the latest research, including why BORG drinking can lead to victory—if done by the other crew.

The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) is a professional organization for sport-science researchers, exercise physiologists, dietitians, doctors, and athlete-care providers. Each year, at ACSM’s annual meeting, more than 3,000 sports-medicine professionals and scientists from around the globe gather to present their latest research.

At this year’s meeting in Denver, a lively session hosted by Professionals in Nutrition for Exercise and Science, a worldwide organization for sport nutritionists, addressed several topics that are currently hot, including some that may interest rowers:

Continuous glucose monitors (CGM) can help athletes determine the best fueling tactics to maintain blood glucose levels within an energizing range and reduce needless bonking. This can be very helpful during endurance exercise such as long rows. Unfortunately, CGMs have yet to be perfected for athletes. The monitors can get dislodged from the body easily, and some studies show a failure rate of greater than 15 percent. The sport of cycling has banned CGMs during races, but many cyclists use them during training to learn how to “read” their body signals.

While extra evening protein is unlikely to offer a winning edge, it also will not cause harm or convert into body fat. Research to date shows that pre-sleep protein provides another opportunity to meet daily protein goals. More research is

needed to determine if consuming pre-sleep protein will help enhance muscle recovery, tissue repair, sleep, or performance.

Free amino acids and bioactive peptides

When compared to the protein in whole foods, free amino acids are slightly less effective for muscle-protein synthesis. Consuming protein within its natural food matrix is best. Plus, free amino acids taste terrible (although they have improved over the years). Bioactive peptides (two to three amino acids linked together) are available for purchase but lack research to validate potential benefits. So why bother?

Bicarbonate supplementation