13 minute read

POSITIONALITY & DISCLAIMER

A large portion of my identity is shaped by my heritage– my roots stemming from a land filled with conflict, displacement, and intergenerational trauma. Half of my ancestors did not survive the atrocities of the Holocaust; those who survived struggled to make a place in the world that didn’t accept them. One who immigrated to Canada, and my first cousin is named for, lived his life as a hoarder, afraid that he would lose everything again. Antisemitism is very much alive and on the rise worldwide.

I have privileges as an Israeli citizen that Palestinians do not, such as the ability to visit, move, and speak freely. While I cannot access certain zones under Palestinian jurisdiction, my access to Israel is expedited. My friends and family in Israel and Palestine endlessly fear for their lives, in and out of bomb shelters, while I only worry from the comfort of my own home, never having feared being displaced. I am a member of a small dialogue group called Bridge, comprised partly of Jews and Palestinians. In that space, I have learned the importance of dialogue, understanding, and listening to each other’s stories and narratives. I learned that there is more that unites us than divides us. It is a privilege to have those conversations, engage in activism, and write this graduate project in Canada without fear of persecution.

Advertisement

As I write this graduate project, a constant existential battle occurs in my mind. Professors and classmates have told me I am somewhat optimistic. I am not naive or overly optimistic. I understand my family, my friends, and my own reality. I have seen peace, and I have felt the consequences of war. I know my words are universalist messages of hope. The conflict is internationalized, and I am playing a part. I know I am suitable to play a part, even if it is just optimism. I do not pretend to understand the lived experience of those who are occupied, but through this project I will listen.

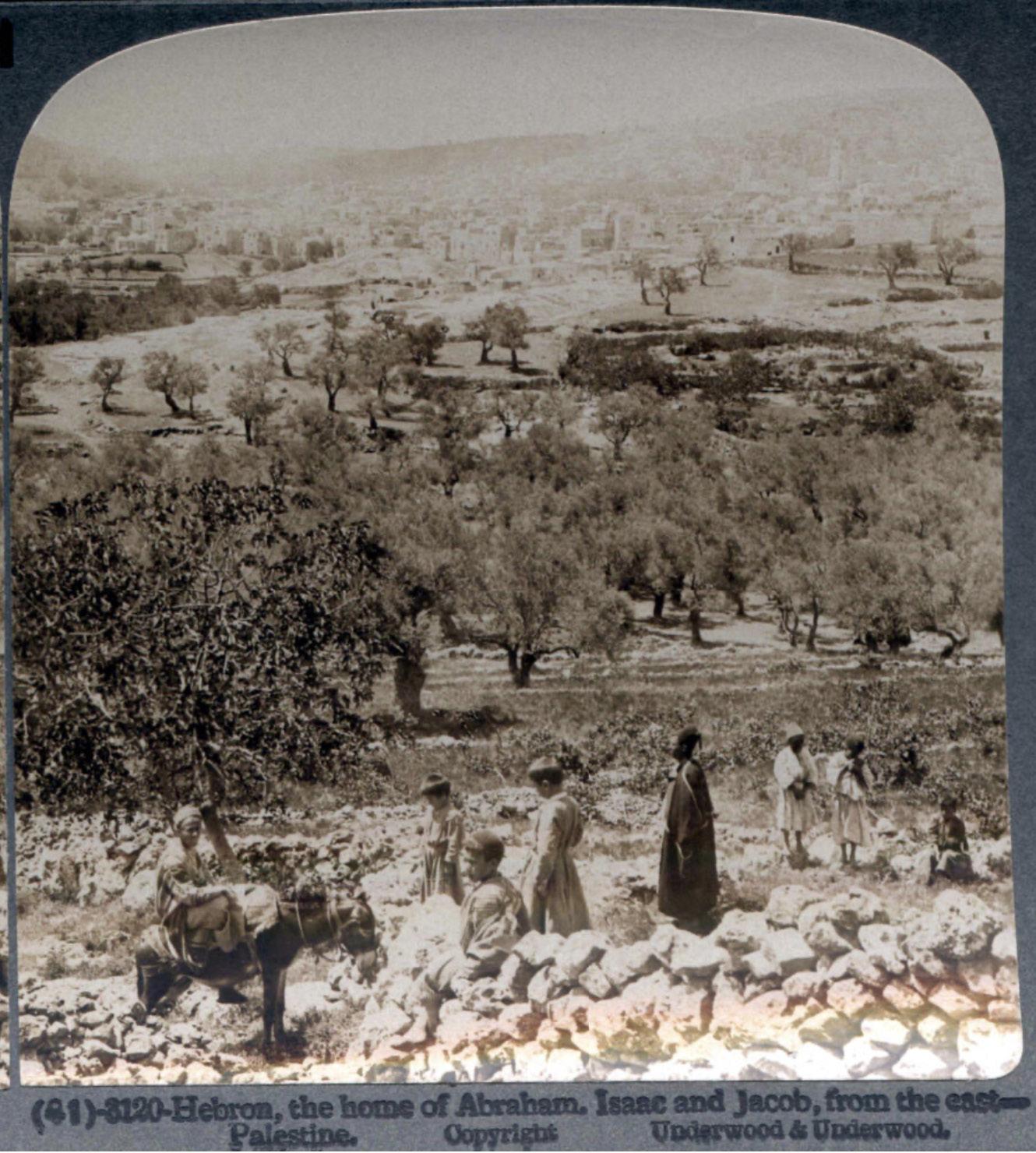

I want to be clear that this project is a love letter to my country. The land that many people and myself feel deeply connected to. The olive groves, the fruit trees, rolling hills, and valleys are part of me. It is because of my connection and love for this land that I wish to see it progress. I think of my family, my friends, and my friend’s family who do not deserve to live in fear or occupation. I think of future generations who deserve peace and liberation.

Introduction

In the contested landscape of Israel and Palestine, populated by communities with conflicting narratives, storytelling and placemaking plays a critical role in peacebuilding and mediating political tension. This project will study methods in landscape architecture that may reveal connections, stories, differences, and similarities embedded in the fabric of the landscape. While the Israeli-Palestinian situation is immensely complicated, this project takes a land-based approach to mediating what is ultimately a conflict rooted in the land. We are perpetually disappointed when we put our faith in politicians to facilitate conflict resolution. These past and present attempts at peace have created a landscape of estrangement through the construction of a ‘separation barrier,’ checkpoints, separate roads, and by using trees to fight wars or root oneself in the landscape. These divisive strategies not only divide the land but also divides those who inhabit it. Attempts at political peace to date are keeping everyone in a zero-sum game. No community’s freedom, liberation, and safety should come at the expense of another’s.

Israelis and Palestinians experience intergenerational trauma caused by centuries of persecution, displacement, islamophobia and antisemitism. Past social trauma, such as the experience of diaspora, fosters a distrust of others, a collective identity formed around victimhood, and bolsters us-versus-them thinking.1 A drastic mind shift happens when community members engage in humanizing dialogue and begin listening to each other’s narratives. We start to realize that our grief is the same grief. Storytelling and prioritizing discussion of personal, present experiences of the conflict increases empathy and intergroup acceptance in Israeli-Palestinian dialogues.2 These communities deserve a safe physical space that invites conversation, reflection, and storytelling. The manipulation of physical space can tell a story of deep love for the land, whether you live there now or dream of returning one day. In Peacebuilding and Spatial Transformation: Peace, Space and Place (2017), Annika Björkdahl and Stefanie Kappler affirm:

“Spaces of war can be transformed into spaces of peace– and vice versa. Places therefore always hold the possibility of hosting spaces that reinforce division or that challenge and overcome the latter. It is the forms of agency that develop around a particular place that determine its social meanings and functions.”3

-Annika Björkdahl and Stefanie Kappler

Moreover, this project is a dialogue in and of itself. By approaching this topic with empathy at the forefront, we start to see the conflict through a new lens. We open the floor for discussions on the cultural symbolism of trees, the landscape manifestations of rootedness after diaspora, being willing to open oneself to new and challenging narratives, and the landscape practices of warfighting or peacebuilding.

Traumatic experiences of diaspora that both Israelis and Palestinians experience fosters a desire for rootedness. To feel safe, secure, and liberated in the land. Our futures are threads that are now and forever entangled with one another. Perhaps the strongest thread is the one that runs deep into the landscape and ties us to it. In this way, the landscape is common ground. While it may be politicized and divided, the landscape is unprejudiced. The air we breathe is the same air, the water’s flow is unrestricted by borders, and the olive trees that grow on both sides are symbols of peace, truth, steadfastness, and perseverance. Olive trees take decades to produce fruit and can only be cultivated after enduring long-lasting stability, making their designation as a peace symbol properly ironic in this land.4 Olive cultivation and the use of charred olivewood in construction are traced back in this land likely to the Early Bronze Age.5 In Apeirogon: A Novel, author Colum McCann writes:

“In his first century B.C. treatise De Architectura, Vitruvius Pollio said that all walls which require a deep foundation- from barriers to huge wooden defence towers- should be joined together with charred olive ties. Olive wood does not decay even if buried in the earth or placed deep in water.”6

- Colum McCann

The olive tree, representing steadfastness for Palestinians and their territorial claim to Israel/Palestine, is paralleled with the symbolic importance of the pine tree for Israelis. The pine tree came to symbolize Jewish rootedness in the landscape because of the Jewish National Fund: Israel’s intermediary for land acquisition and prime afforestation agency. It is precisely because of the pine and the olive’s metaphorical rootedness in the landscape that they were natural proxy-soldiers, proxy-nation-builders, and easy targets. Pine forests are often located atop destroyed Palestinian villages and are often victims of arson attacks. Olive trees have been uprooted to make way for watchtowers, checkpoints, and the separation barrier.

The 708-kilometer built separation barrier that divides Israel and the West Bank is the physical manifestation of tension, division, and a desire for rootedness and security. The construction of borders is often used to keep unjust systems frozen in space and time and to maintain power imbalances.7 The wall has tattered opportunities and destroyed physical spaces for human connection and dialogue between both groups, and “exacerbated the conflict and contributed to the emergence of a segregated landscape.”8 Traversing agricultural land and desert, pine forests and olive groves, dividing cities and surrounding settlements, the wall epitomizes Israel’s endeavour to exert power and territoriality and practice the act of enclosure.

For Israelis, the wall symbolizes security, strength, and defence. For Palestinians, the wall symbolizes theft, occupation, and an unreachable statehood. Symbolism, however, does not change the fact that children grow up in these landscapes shaped by conflict in a home shadowed by a concrete wall. The construction of the separation wall uprooted hundreds of hectares of olive trees9 and made many olive groves inaccessible for cultivation and care. Three sites for intervention at the separation wall will study relationships in a divided landscape and the roles trees and spacemaking play in peacebuilding. The olive tree will guide the design process as a statue of strength, a symbol of peace, and reinforce ties to each other and the land.

“The world I was born into, the one I grew up in, made no sense. Surrounded by such beauty: the land full of rolling hills, green pastures, clear streams, and strong olive trees, the community full of welcoming neighbours who became extended family, the sun, the rain, the animals on the farm. That is home. Also surrounded by: armed soldiers, giant military tanks, stolen land, homes destroyed, a 25-foot wall preventing the freedom to travel, daily checkpoints, ID checks on the way to school, death, sadness, anger. That, too, is home. In reflecting back I am acutely aware of my desire to make sense of the dichotomy in which I existed.”10

– Izzeddin Hawamda

Endnotes

1. Julia Chaitin and Shoshana Steinberg, “”You should Know Better”: Expressions of Empathy and Disregard among Victims of Massive Social Trauma,” Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 17, no. 2 (2008): 205.

2. Ella Ben Hagai, Phillip L. Hammack, Andrew Pilecki, and Carissa Aresta, “Shifting Away from a Monolithic Narrative on Conflict: Israelis, Palestinians, and Americans in Conversation,” Peace and Conflict 19, no. 3 (2013): 298.

3. Annika Björkdahl and Stefanie Kappler, Peacebuilding and Spatial Transformation: Peace, Space and Place, 1st ed, London: Routledge, 2017, 138.

4. Rami Sarafa, “Roots of Conflict: Felling Palestine’s Olive Trees,” Harvard International Review 26, no. 1 (2004): 13.

5. Nili Liphschitz et al, “The Beginning of Olive (Olea Europaea) Cultivation in the Old World: A Reassessment,” Journal of Archaeological Science 18, no. 4 (1991): 450.

6. Colum McCann, Apeirogon: A Novel, First ed, New York: Random House, 2020, 170-171.

7. Björkdahl and Kappler, 143.

8. Silvia Hassouna, “Spaces for Dialogue in a Segregated Landscape: A Study on the Current Joint Efforts for Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict,” Conflict Resolution Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 1, 2016, pp. 57-82.

9. Gary Fields, “Landscaping Palestine: Reflections of Enclosure in a Historical Mirror,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 42, no. 1, 2010, 75.

10. Izzeddin Hawamda. Quote derived from a text exchange in September 2022, with permission granted for this purpose. Izzeddin is a teacher, activist, Ph.D. candidate, poet, storyteller, and dear friend of mine. He co-founded the IsraeliPalestinian Dialogue group, Bridge, of which I am a part. Growing up in a rural village near Nablus in the West Bank, Izzy offers an invaluable perspective that he manages to put into words in eloquent poetry and stories.

Part 1: Diaspora & Manifestations of Rootedness

“Individual members of groups in conflict with one another are in fact profoundly defined by the conflict itself, meaning that resolution of the conflict means removing a — if not the — definitive aspect of group members’ shared identity.”1 –

Ingrid Anderson

I am a Jewish person with Israeli citizenship who grew up in a very one-sided milieu, view of history, and education on the conflict. While I have expanded my worldview to become as neutral as possible, I am still biased. In this section, I attempt to summarize some of the histories and narratives that set the context for this project. I will not try to pretend like I completely understand both sides and can, therefore, adequately speak for either. I especially leave room for personal Palestinian experiences and narratives to be heard and told by those who truly know them. The history of Israel/Palestine, its lands, and its peoples is a complex set of narratives on ownership, control, and competing national identities. I have included a timeline of key narratives in this section. However, it is critical to begin with an understanding of the primary narratives that make coexistence and peace more difficult to achieve.

Trauma, Belonging, Displacement

Whether or not as a Jew, you are religiously observant or what many call ‘culturally Jewish,’ having a connection to Eretz Israel (the Land of Israel) is one of the primary pillars of Judaism. Most Jews see ancient history as a story of exodus, genocide, and triumph. This very deeprooted cultural tale of one day returning to Israel prevents many Jews from being willing to part with this sense of belonging in any capacity. It is also why many Jews reject terms like ‘settler’ or ‘colonizer,’ as Israel is the land they feel a sense of belonging and indigeneity. The Zionist movement that brought Jews back to Israel is contested among the Jewish community. Still, the primary principle that Jews belong in Israel and always have is less disputed. The many holy and sacred places in Israel/Palestine (the terms I use to describe the land as it is today) further connect Jews with their ancient history, such as the Western Wall in Jerusalem, the last standing wall of the Second Temple from the 2nd century BCE. Overlooking the Dead Sea, Masada houses ancient remains of a Jewish fortification built to resist Roman troops and is also where I had my Bat Mitzvah at age thirteen. While Jews existed in Israel/Palestine long before the birth of Islam, Arab presence in the land is also ancient. The Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque, built by the Umayyads after the Muslim Conquest, is a holy site for Muslims worldwide. Arab tribes fought against Byzantine and Roman invasions, just as Jews did if not alongside them. But these two communities and countless foreign powers wrestled for control of Palestine. It must also be acknowledged that the most recent foreign entity to control the land, the British, played a critical role in dividing Arabs and Jews and kickstarting the current conflict as it exists today.

The Holocaust and the Nakba

Israelis and Palestinians both experienced and continue to experience trauma relating to displacement. The two primary events contributing to this collective feeling are the Holocaust and the Nakba. The growing wave of violence against Jews worldwide, especially in Europe, stimulated desperate immigration to Palestine. The Holocaust resulted in the systematic genocide of over 6 million Jews at the hands of the Nazis. Research has shown that traumas of massive social violence, such as the Holocaust, haunt victims and their decedents for many years as the trauma is biological, sociocultural, psychodynamic and familial.2 Holocaust studies are hyper-prevalent in Jewish schools and programs worldwide. Delegate groups like March of the Living sends groups of students to death camps across Poland, strengthening the notion of needing a safeguard that would protect Jews from another genocide. It certainly does not help matters that millions of people deny the factuality of the Holocaust, and white-nationalist Nazi groups worldwide terrorize the memory of this trauma.

The aftermath of the Shoah saw the immigration of deeply traumatized and displaced Jews who became beneficiaries of the traumatic displacement and forceful removal of the Palestinian people. This mass exodus and displacement of approximately 750,000 Palestinian people from the land is referred to as al-Nakba (the catastrophe). The Nakba occurred in 1948, beginning the morning after Israel declared its independence and ended the British Mandate for Palestine. That morning, Jordan, Egypt, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen joined forces to enter the newly formed state and attack. Israel won the war after ten months of fighting and occupied even more territory than they held during their Declaration of Independence. Almost every Palestinian has been affected by the Nakba, regardless of age or location. Similarly to the Jewish collective trauma, victims and their decedents continue to suffer.

According to most Israeli narratives, the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who left during the war did so voluntarily as they expected and were told that they may eventually return to their homes after an Arab victory, which ended up not happening.3 The trauma of the Nakba became the essence of the Palestinian cause post-1948, and the narrative of an uprooted nation of refugees emerged.4 The Palestinian narrative claims that Palestinians have lived in this region for 1500 years and made up 90% of the population at the time when the British issued the Balfour Declaration.5 Mourid Barghouti describes this feeling of displacement and diaspora in I Saw Ramallah, writing:

“Because of the many places that the circumstances of the Diaspora made us live in, and because we so often had to leave them, our places lost their meaning and their concreteness.”6

-Mourid Barghouti

The argument about which group has suffered more as a collective is a typical proponent in many discussions of national belonging. Even Jewish Israelis who are critical of the Zionist movement and actions that have been taken on their behalf by the Israeli government often rely on this very comparison that views them as ‘inheritors of Jewish fate and tragedy’ as having greater victimhood than the Palestinians and their suffering.7 The fact of the matter is that both groups have suffered at the hands of the other and the hands of external foreign forces. For Israelis, omnipresent existential fear and memories of trauma and victimhood make it difficult to acknowledge their oppression of the Palestinians. Palestinians’ demand for dignity, justice, and liberation is fueled by “seemingly permanent humiliation, indignity, dispossession and disrespect.”8 They are constantly reminded of the unbalanced power dynamics and feel that Israel (with the United States at their side) is to be blamed for their suffering and Israel’s destruction is necessary if they are to see an end to occupation and achieve just independence.9

At the heart of it, neither group accepts the other’s legitimacy, narrative, or right to exist. Both experience distrust and intergenerational trauma and believe they would be safer and happier if the other found somewhere else to live (which, of course, will never happen). One-state, two-state, or no-state, there is no future where either will be satisfied so long as no one speaks to each other or acknowledges the other’s right to exist. Facts can be disputed, and the history of this land is so ancient that texts and discoveries have been revisited and retranslated countless times.

It is not up to one person to say that someone else’s entire belief system and one group’s entire collective narrative is wrong. It is imperative at this point that we move toward a place where we can acknowledge that two truths can exist at once, and the future holds the possibility for a new collective identity, one that is not based on the delegitimization of the other.

While suffering and displacement are a pillar of both narratives, it is paramount to remember that these stories are also tales of resilience. Palestinians have continued to persevere under consistent occupation, and Israelis have been resilient to continuous external threats made against them by their many enemies. They will continue to make a home for themselves in the land they love and care for.