BUILD A MORE INTEGRATED, COMPASSIONATE, AND HARMONIOUS COMMUNITY WHERE THE RICH TAPESTRY OF HUMAN EXPERIENCES SPANNING GENERATIONS CAN BE CELEBRATED AND INTERCONNECTED.

This thesis engages in an architectural exploration of the cultural implications surrounding fragmentation and alienation experienced by the elderly and unwell within our current youth-oriented and consumerist social system. Focusing on integrating sensation, psychology, and interaction into architecture and drawing inspiration from a blend of aesthetic and cultural production, this study aims to raise consciousness, awareness, and attention to pressing societal issues.

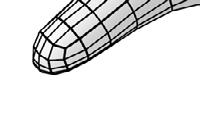

Recognizing the profound impact of deterioration and dementia on the lives of the elderly and unwell, this multivolume mixed-use building project catalyzes reintegration

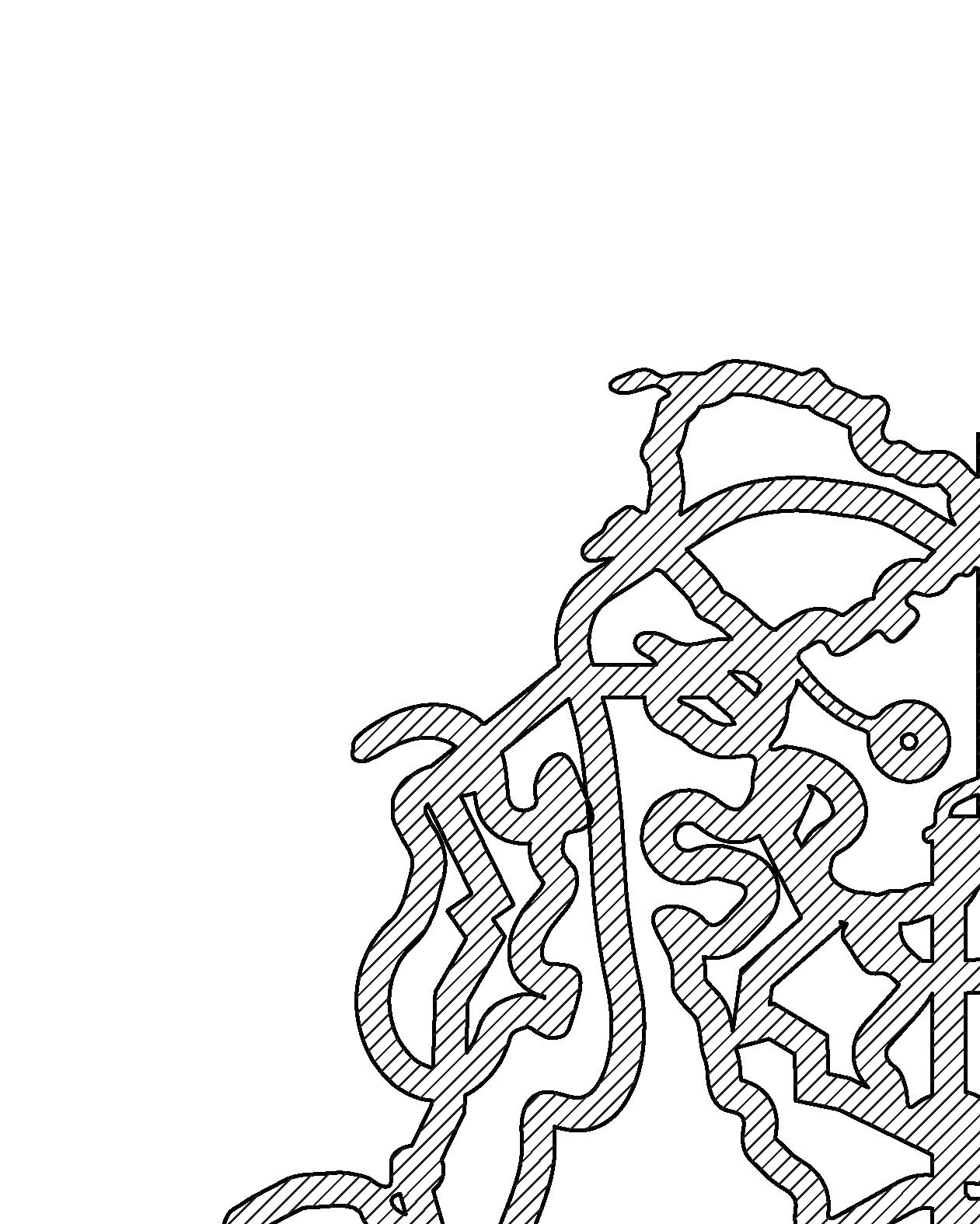

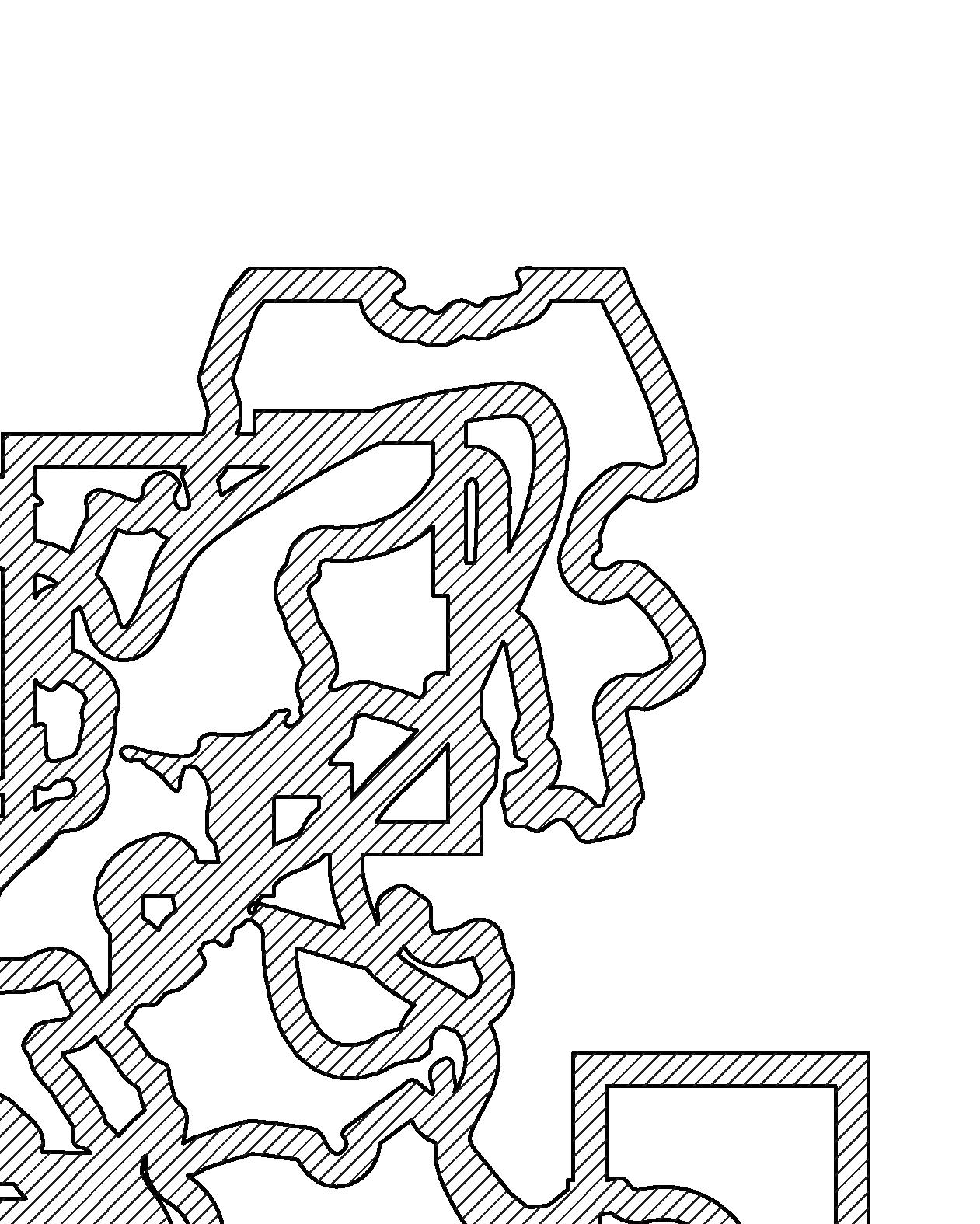

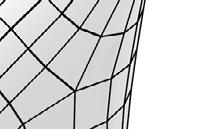

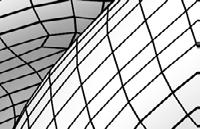

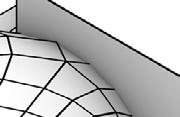

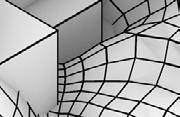

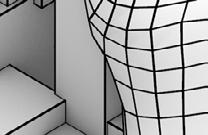

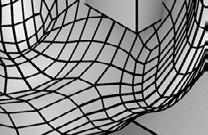

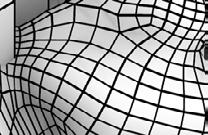

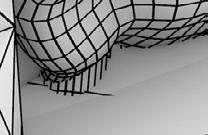

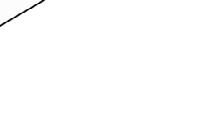

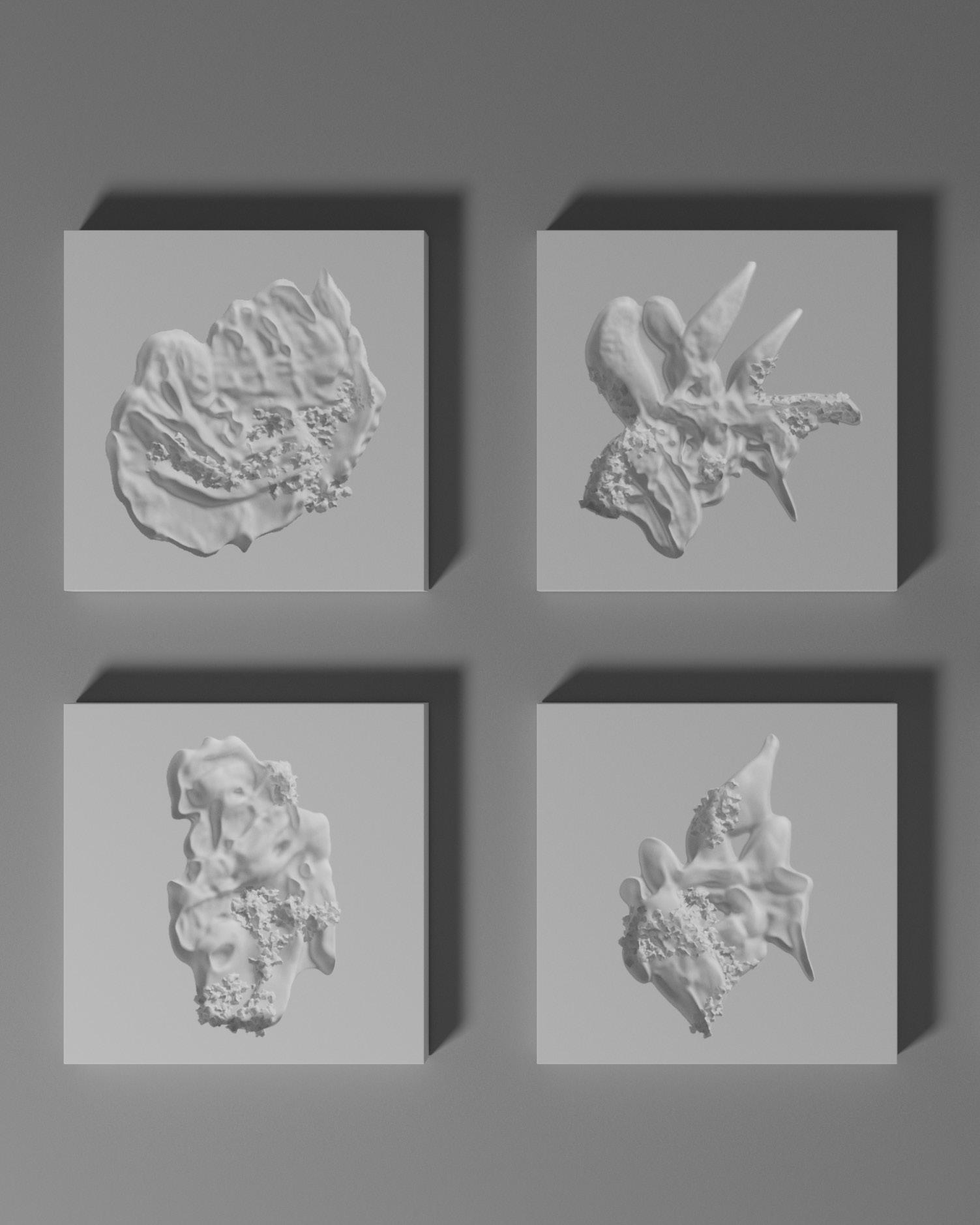

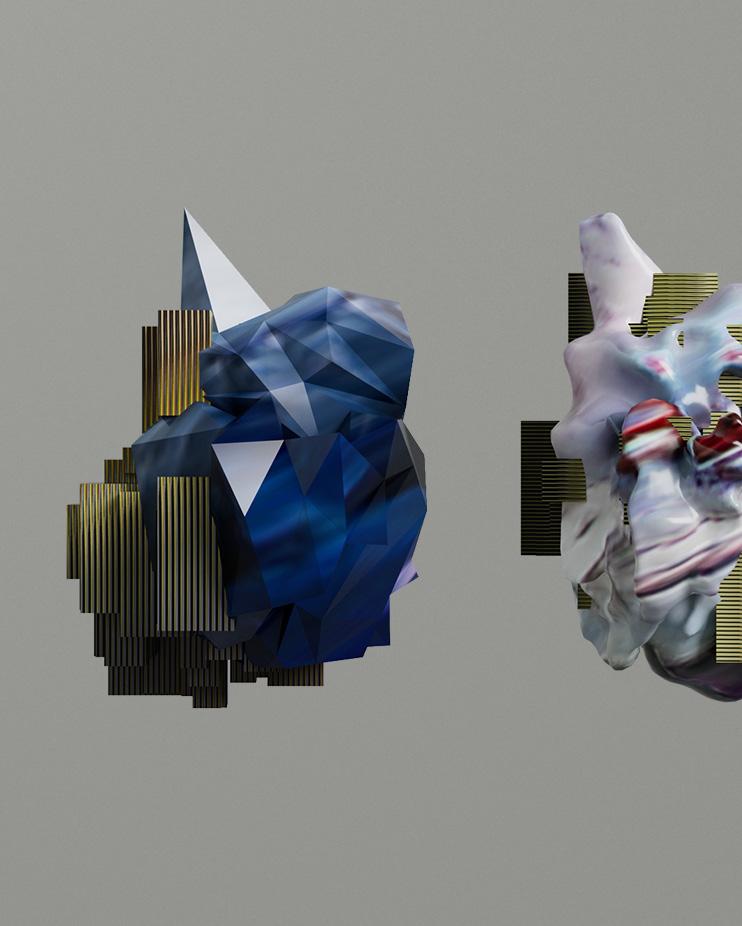

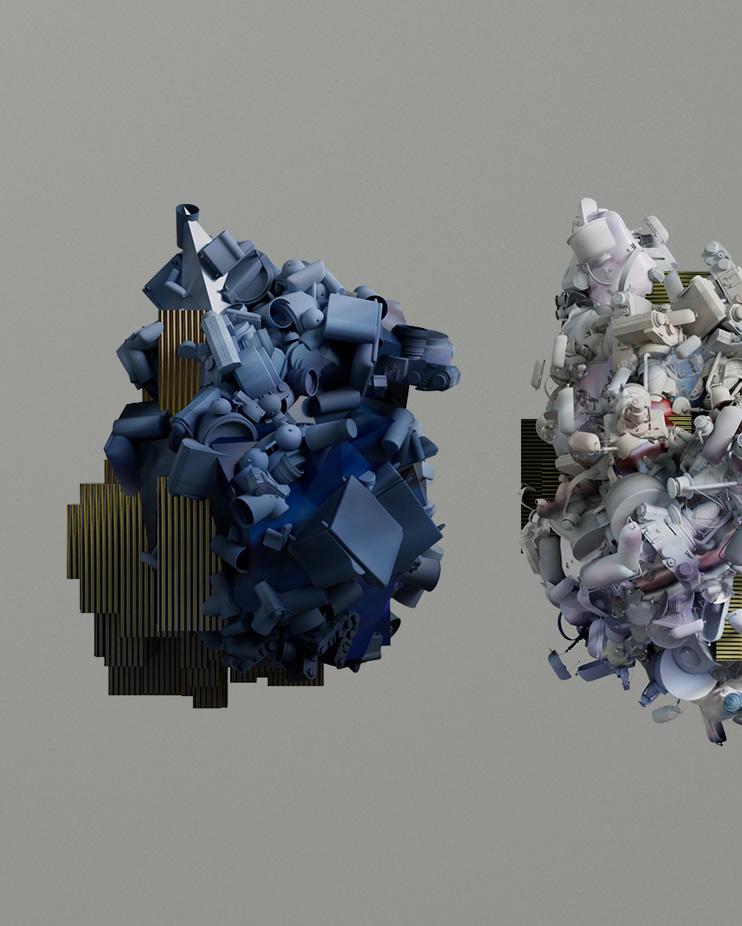

by implementing transformative spaces—a captivating and immersive museum and a vibrant community activity center. The project employs innovative techniques to address the challenges associated with dementia, recognizing it as involving errors in aesthetics, misremembering, disruption in legibility, and erasure. The emphasis remains on the aesthetic and cultural significance of the undertaken measures.

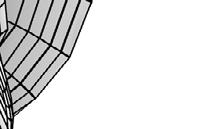

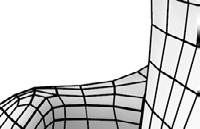

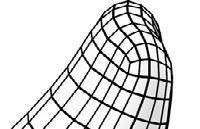

Blurring boundaries, merging memories, and reimagining the built environment, the design achieves an uncanny integration that defies hierarchical structures, fostering inclusivity and unity. The project taps into the creative potential found in the misremembering and reconfiguration of spaces, allowing for

a more empathetic and responsive design that caters to the changing needs and experiences of the citizen.

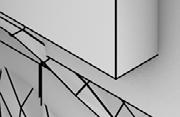

As an urban intervention, the thesis seeks to change the urban fabric and establish stronger connections with its surroundings, particularly the small and inadequate community centers in Los Angeles. By incorporating a largescale community center in the core of Downtown, the design aims to revitalize the urban environment, promote social cohesion, and facilitate interactions among diverse groups while considering the specific needs of those affected by dementia.

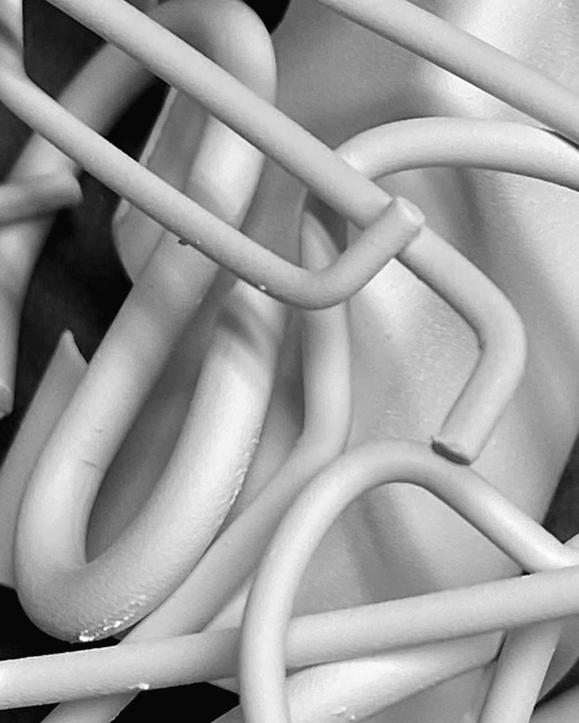

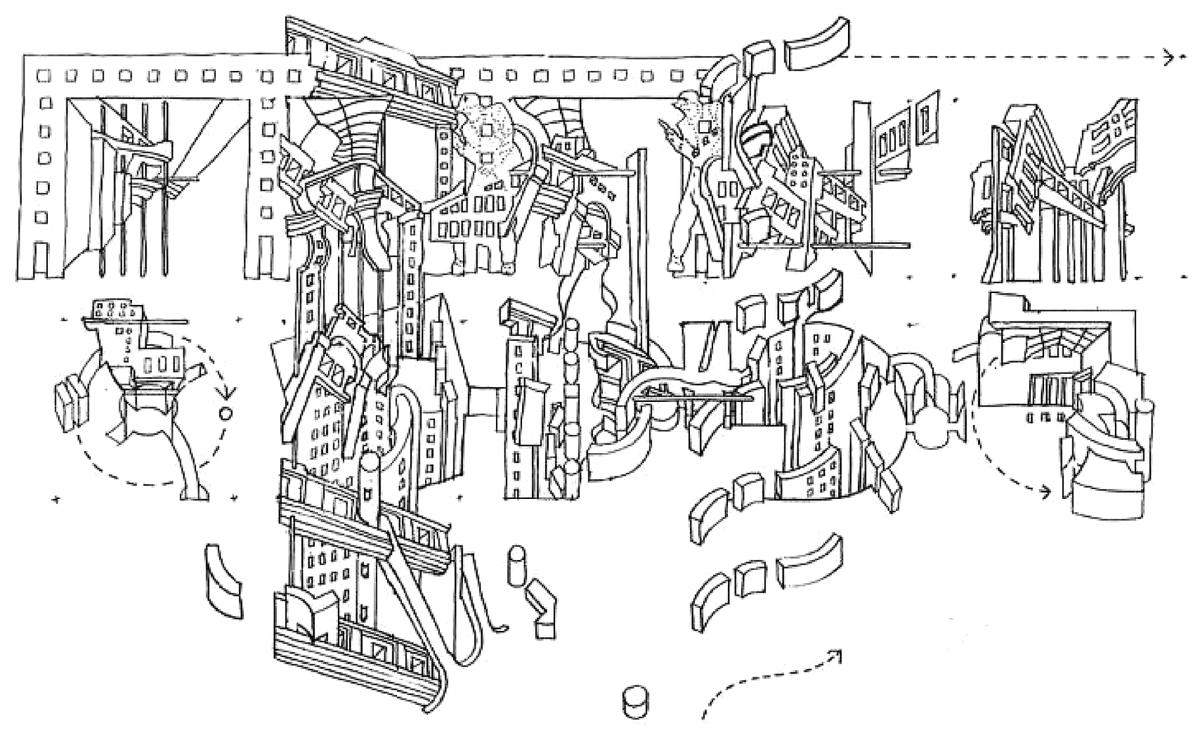

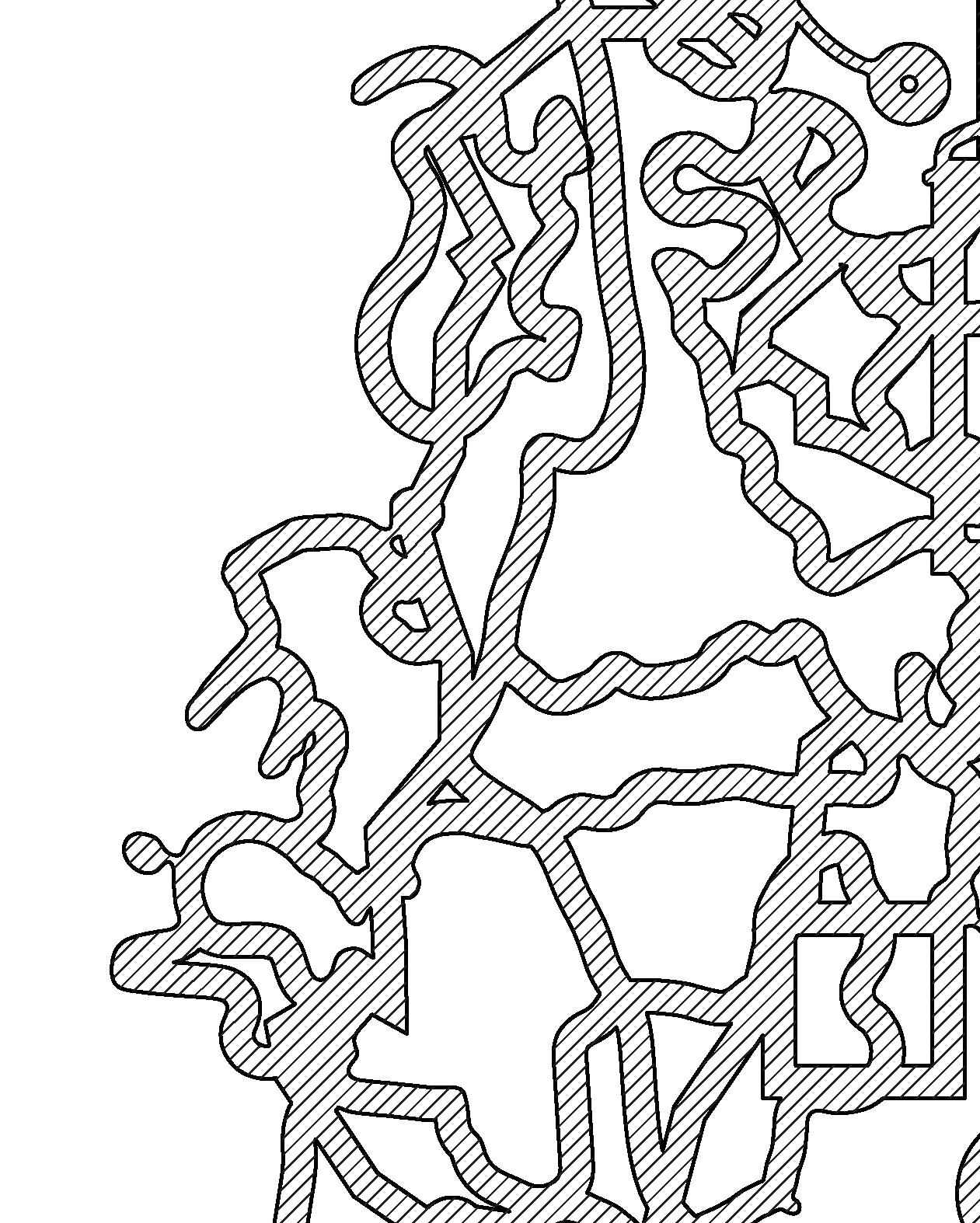

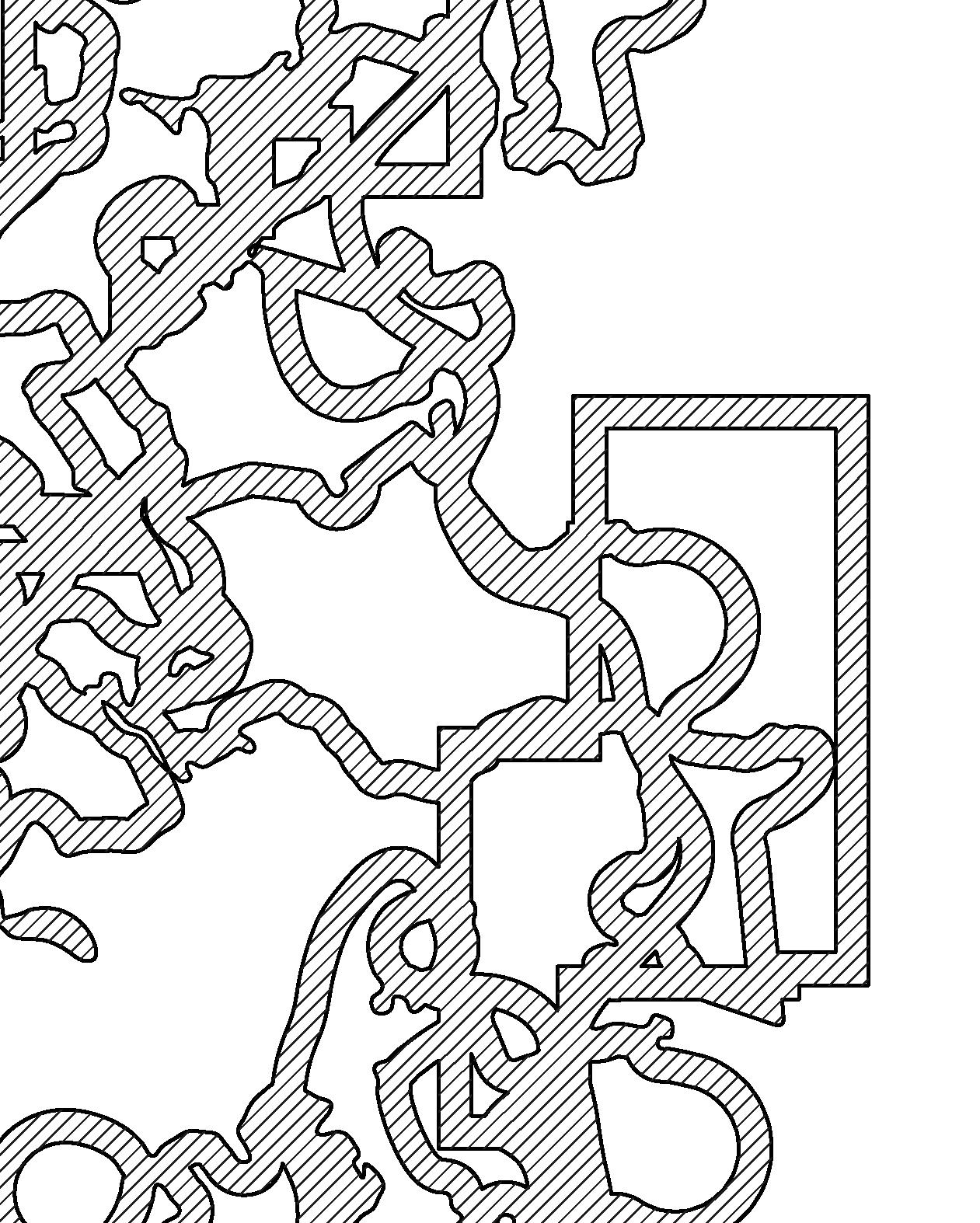

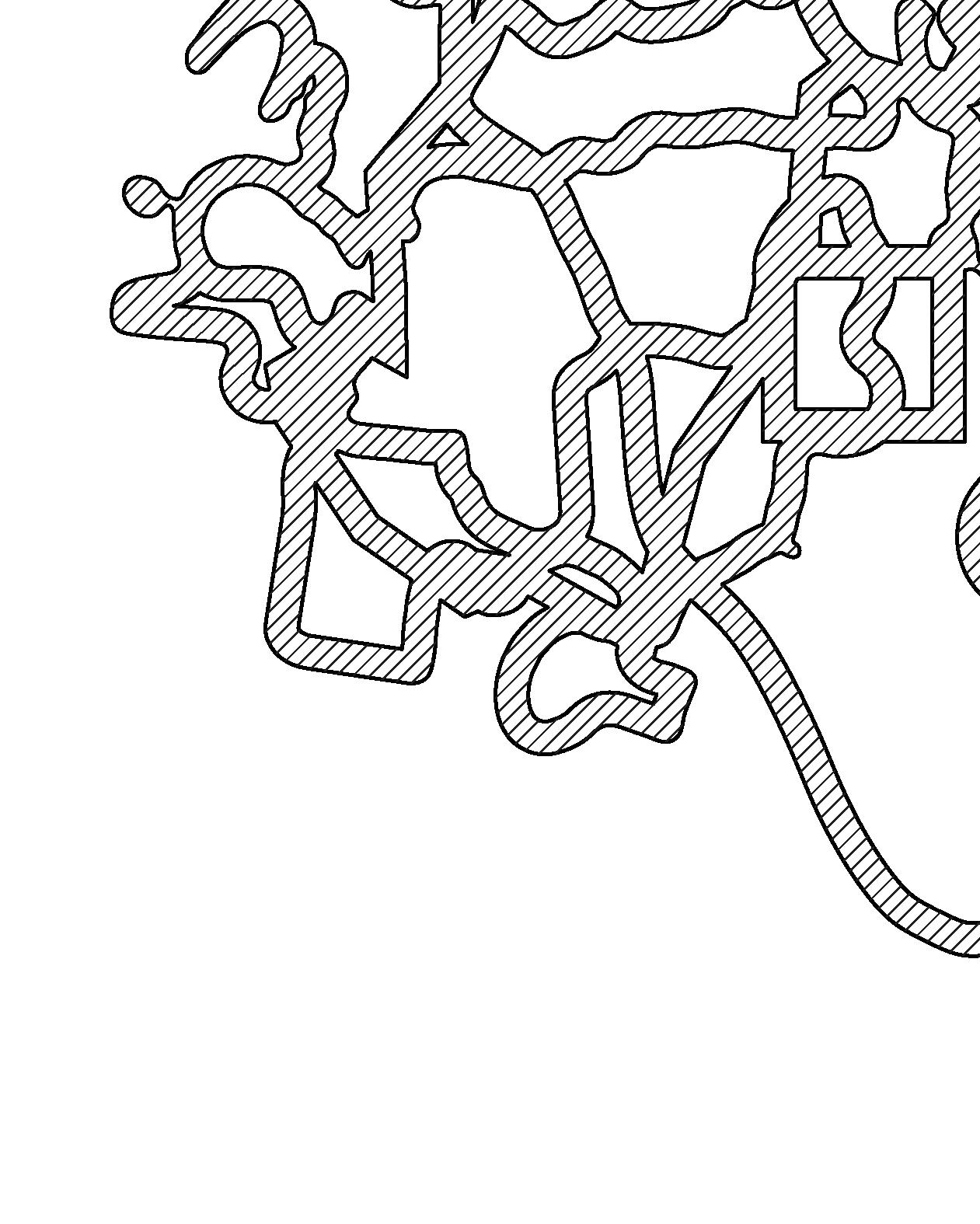

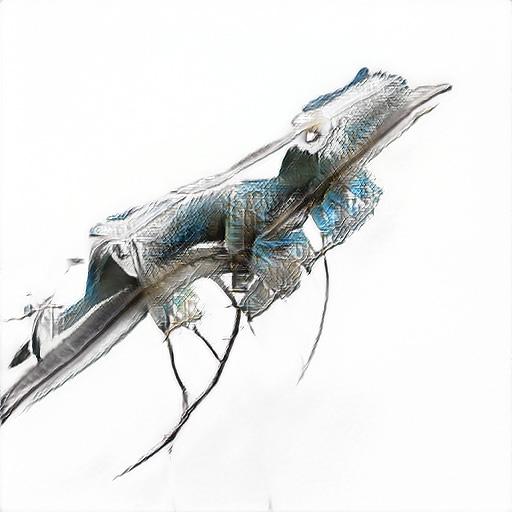

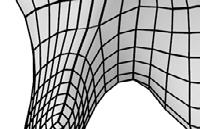

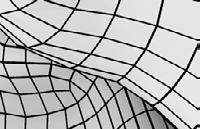

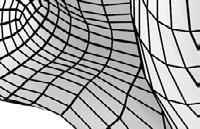

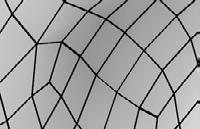

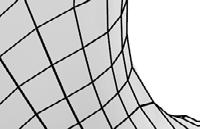

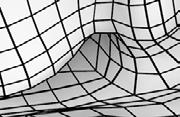

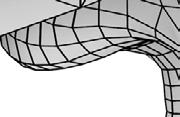

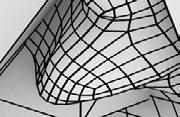

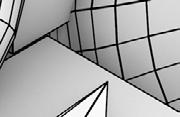

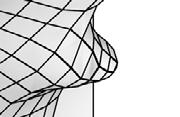

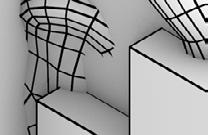

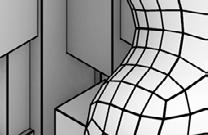

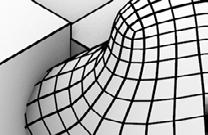

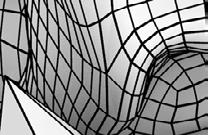

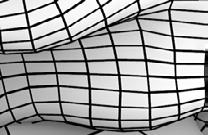

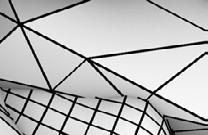

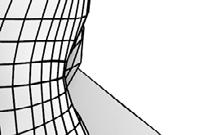

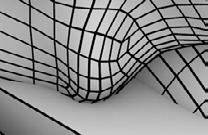

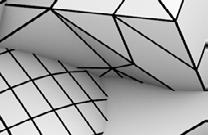

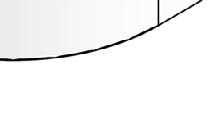

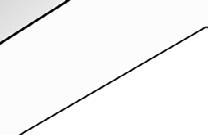

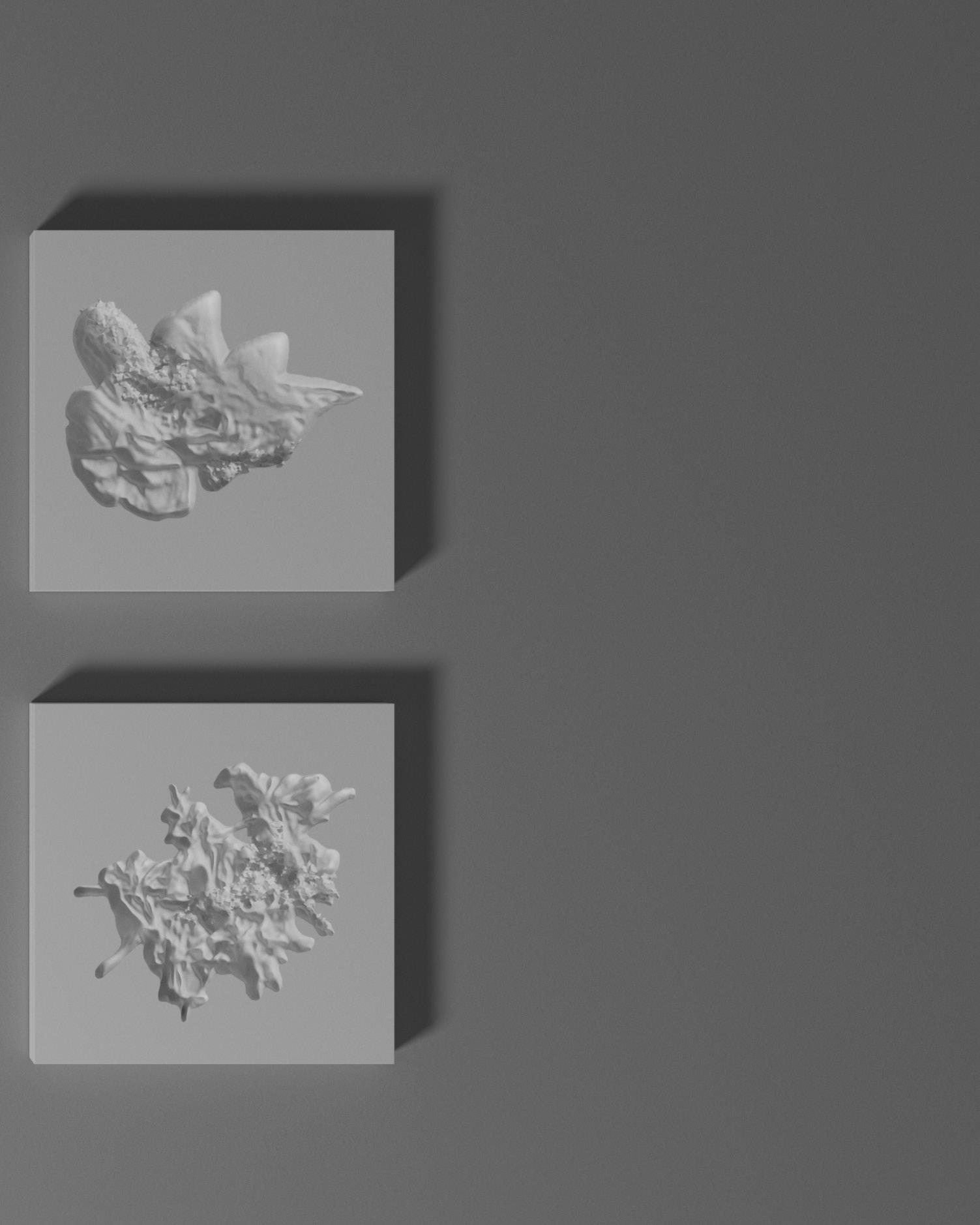

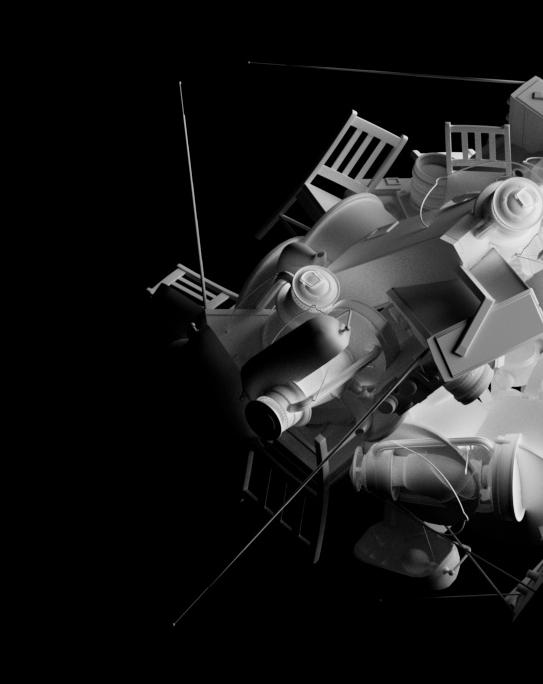

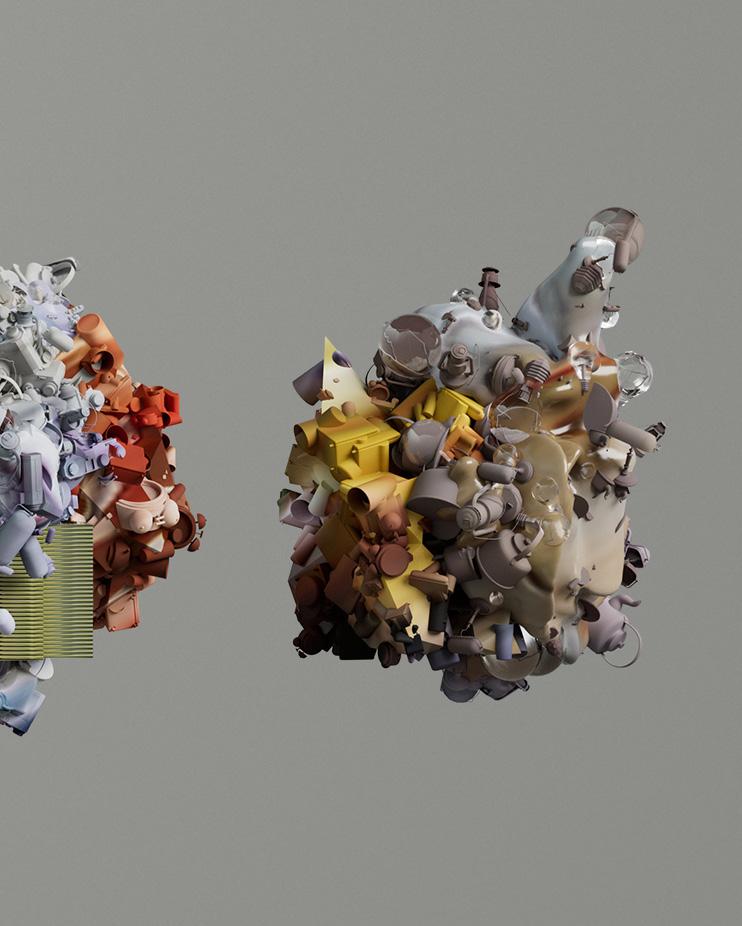

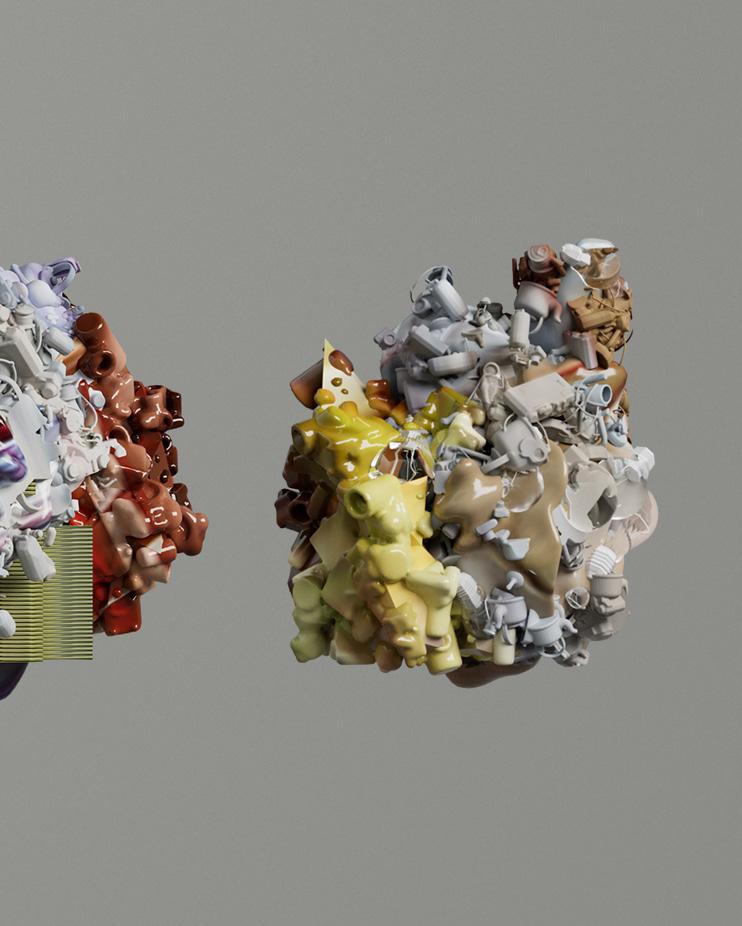

Delving into the psychological and mixed mental landscapes of people with dementia and the unwell, the project captures the paradoxical nature of their inner world. Leveraging machine learning capabilities of Style Generative Adversarial Network techniques to mimic intricate and nuanced states of mind, the spaces reflect the older generation's delicate dance between order and chaos, clarity and confusion, simplicity and complexity. By embracing the disruptions and errors of

dementia, the thesis strives to create legible, engaging, and nurturing environments for individuals experiencing memory loss. The project critically reflects and responds to the cultural contradictions of our time. It stimulates contemplation and dialogue by harnessing generative design to challenge societal norms and blur boundaries. The abstract-yettangible design serves as a tool for transformative storytelling and cultural reflection, fostering a shift in perceptions and attitudes toward aging people.

The ultimate aspiration is to ignite a cultural reawakening, breaking down the isolation between generations and social groups. By nurturing inclusive spaces and cultivating a collective consciousness in architectural design and contemporary culture, this thesis strives to build a more integrated, compassionate, and harmonious community where the rich tapestry of human experiences spanning generations can be celebrated and interconnected.

More complex, it is not the symptom of professional naivete or economic ignorance but the sign of a fundamental question that lies in the very nature of architecture and of its essential element: space. By focusing on itself, architecture has entered an unavoidable paradox that is more present in space than anywhere else: the impossibility of questioning the nature of space and at the same time experiencing a spatial praxis.

Linguistically, to define space means both "to make space distinct" and "to state the precise nature of space." Much of the current confusion about space can be illustrated by this ambiguity. While art and architecture have been concerned essentially with the first sense, philosophy, mathematics, and physics have tried throughout history to give interpretations to something variously described as a "material thing in which all material things are located" or as "some thing subjective with which the mind categorizes things." Remember: with Des cartes ended the Aristotelian tradition according to which space and time were "categories" that enabled the classification of "sensory knowledge." Space became absolute. Object before the subject, it dominated senses and bodies by containing them. Was space inherent to the totality of what exists? This was the question of space for Spinoza and Leibniz. Returning to the old notion of category, Kant described space as neither matter nor the set of objective relations between things but as an ideal internal structure, an a priori

consciousness, an instrument of knowledge. Subsequent mathematical developments on non-Euclidean spaces and their topologies did not eliminate the philosophical discussions. These reappeared with the widening gap between abstract spaces and society But space was generally ac cepted as a cosa mentale, a sort of all-embracing set with subsets such as literary space, ideological space, and psychoanalytical space.

The questions, "is there any reason why one cannot proceed from design that can be constructed to design that concerns itself only with the ideology and concept of architecture?" and "if architectural work consists of questioning the nature of architecture, what prevents us from making this questioning a work of architecture in itself?"' were already rhetorical questions in 1972. The renewed importance given to conceptual aims in architecture quickly became established . The medium used for the communication of concepts became architecture; information was architecture; the attitude was architecture; the written program or brief was architecture; gossip was architecture; production was architecture; and inevitably, the architect was architecture. Escaping the predictable ideological compromises of building, the architect could finally achieve the sensual satisfaction that the making of material objects no longer provided.

If architecture seemed to have gained freedom

from the socio economic constraints of building processes, any radical counter-designs and manifestos were inevitably reinstated in the commercial circuits of galleries or magazines. Like conceptual art in the mid-1960s, architecture seemed to have gained autonomy by opposing the institutional framework. But in the process it had become the institutional opposition, thus growing into the very thing it tried to oppose.

Rational architecture, for example, becomes a selected vocabulary of architectural elements of the past, with their oppositions, contrasts, and redistribution s. Not only does it refer to itself and to its own history, but function-the existential justification of the work-becomes virtual rather than real. So the language is closed in on itself, and architecture becomes a truly autonomous organism. Forms do not follow functions but refer to other forms, and functions relate to symbols. Ultimately architecture frees itself from reality altogether. Form does not need to call for external justifications. In a critical article in Oppositions, Manfredo Tafuri can thus describe Aldo Rossi's architecture as "a universe of carefully selected signs, within which the law of exclusion dominates, and in fact is the controlling expression," and the trend it represents as 'T architecture clans le boudoir" because the circle drawn around linguistic experimentation reveals a pregnant affinity with the obsessively rigorous writings of the Marquis de Sade.

Should I intensify the quarantine in the chambers of the Pyramid of reason? Shall I sink to depths where no one will be able to reach me and understand me, living among abstract connections more frequently expressed by inner monologues than by direct realities? Shall architecture, which started with the building of tombs, return to the Tomb, to the eternal silence of finally transcended history? Shall

architecture perform at the service of illusory functions and build virtual spaces? My voyage into the abstract realm of language, into the dematerialized world of concepts, meant the removal of architecture from its intricate and convoluted element: space. Removal from the exhilarating differences between the apse and the nave of Ely Cathedral, between Salisbury Plain and Stonehenge, between the Street and my Living Room. Space is real, for it seems to affect my senses long before my reason. The materiality of my body both coincides with and struggles with the materiality of space My body carries in itself spatial properties and spatial determination: up, down, right, left, symmetry, dissymmetry. It hears as much as it sees. Unfolding against the projections of reason, against the Absolute Truth, against the Pyramid, here is the Sensory Space, the Labyrinth, the Hole. Dislocated and dissociated by language or culture or economy into the specialized ghettos of sex and mind, Soho and Blooms bury, 42nd Street and West 40th Street, here is where my body tries to rediscover its lost unity, its energies and impulses, its rhythms and its flux .

This purely sensory approach has been a recurrent theme in this century's understanding and appreciation of space. It is not necessary to expand at length on the precedents witnessed by twentieth-century architecture. Suffice it to say that current conversation seems to fluctuate between (a) the German esthetic overtones of the Raumempfindung theory, whereby space is to be "felt" as something affecting the inner nature of man by a symbolic Einfiihlung, and (b) an idea that echoes Schlemmer's work at the Bauhaus, whereby space was not only the medium of expe rience but also the materialization of theory.

To single out particular areas of concern, such as the rational play of language as

opposed to the experience of the senses, would be a tedious game if it were to lead to a naive confrontation between the mind and the body. The architectural avant-garde has fought often enough over alternatives that appeared as opposites structure and chaos, ornament and purity, permanence and change, reason and intuition. And often enough it has been shown that such alternatives were in fact complementary : our analysis of a dematerialization of architecture in its ontological form (the Pyramid) and of a sensual experience (the Labyrinth) is no different. But if the existence of such an equation does not raise doubts over its complementarity, it certainly raises questions about how such equations can go beyond the vicious circle of terms· that speak only of themselves.

The answer may lie in the context in which such an equation takes place. A common accusation of analyses or even of works that concentrate on the specific nature of architecture is that they are "parallel," that is, they fold and unfold in some Panglossian world where social and economic forces are conveniently absent. Not affecting the determining forces of production, they constitute harmless forms of private expression. We shall therefore briefly consider the ambiguous par ticularities of the relationships between architecture and politics.

To restate my point, t he paradox is not about the impossibility of perceiving both architectural concept (the six faces of the cube) and real space at the same time but about the impossibility of questioning the nature of space and at the same time making or experiencing a real space. Unless we search for an escape from architecture into the general organization of building processes, the paradox persists: architecture is made of two terms that are interdependent but mutually

exclusive. Indeed, architecture constitutes the reality of experience while this reality gets in the way of the overall vision. Architecture constitutes the abstraction of absolute truth, while this very truth gets in the way of feeling. We cannot both experience and think that we experience. "The concept of dog does not bark"; the concept of space is not in space.

In the same way, the achievement of architectural reality (build ing) defeats architectural theory while at the same time being a product of it. So theory and praxis may be dialectic to one another, but in space, the translation of the concept, the overcoming of the abstraction in reality, involves the dissolution of the dialectic and an incomplete statement. This means, in effect, that, perhaps for the first time in history, architecture can never be. The effect of the great battles of social progress is obliterated, and so is the security of archetypes. Defined by its questioning, architecture is always the expression of a lack, a shortcoming, a noncompletion. It always misses something, either reality or concept. Architecture is both being and nonbeing. The only alternative to the paradox is silence, a final nihilistic statement that might provide modern architectural history with its ultimate punchline, its self-annihilation.

As long as social practice rejects the paradox of ideal and real space, imagination-interior experience-may be the only means to transcend it. By changing the prevalent attitudes toward space and its subject, the dream of the step beyond the paradox can even provide the conditions for renewed social attitudes. Just as eroticism is the pleasure of excess rather than the excess of pleasure, so the solution of the paradox is the imaginary blending of the architecture rule and the experience of pleasure.

When Benjamin discussed the reproducibility of images, he pointed out that the loss of their exchange value, their “aura,” made them interchangeable, and that in an age of pure information the only thing that counted was the “shock” -- the shock of images, their surprise factor. This shock factor was what allowed an image to stand out: moreover, it was also characteristic of our contemporary condition, and of the dangers of life in the modern metropolis. These dangers resulted in constant anxiety about finding oneself in a world in which everything was insignificant and gratuitous. The experience of such anxiety was an experience of defamiliarization, of un-zuhause-sein, of unheimlichkeit, of the uncanny.

Recently, we have seen important new research on cities in which the fragmentation and dislocation produced by the scaleless juxtaposition of highways, shopping centers, high-rise buildings, and small houses is seen as a positive sign of the vitality of urban culture. As opposed to nostalgic attempts to restore an impossible continuity of streets and plazas, this research implies making an event out of urban shock, intensifying and accelerating urban experience through clash and disjunction.

When I first met Jacques Derrida in order to try toconvince him to confront his own work with architecture, he asked me, “But how could an architect be interested in deconstruction? After all, deconstruction is anti-form, anti-

hierarchy, anti-structure, the opposite of all that architecture stands for.” “Precisely for this reason,” I replied.

For one architect it had to do with dissimulation, for another, with fragmentation ; for yet another, with displacement. Again, to quote Nietzsche: “There are no facts, only an infinity of interpretations.” And very soon, maybe due to the fact that many architects shared the same dislike for the geborgenheit of the “historicist postmodernists” and the same fascination for the early twentieth century avant-garde, deconstructivism was born -and immediately called a “style” -- precisely what these architects had been trying to avoid. Any interest in post-structuralist thought and deconstruction stemmed from the fact that they challenged the idea of a single unified set of images, the idea of certainty, and of course, the idea of an identifiable language.

Theoretical architects -- as they were called -- wanted to confront the binary oppostions of traditional architecture: namely form versus function, or abstraction versus figuration. However, they also wanted to challenge the implied hierarchies hidden in these dualities, such as, “form follows function,” and “ornament is subservient to structure.” This repudiation of hierarchy led to a fascination with complex images that were simultaneously “both” and “neither/nor” -- images that were the overlap or the superimposition of many other images. Superimposition became a key device.

When metaphors and catachreses are turned into buildings, they generally turn into plywood or papier mâché stage sets: the ornament again. Sheetrock columns that do not touch the ground are not structural, they are ornament. Yes, fiction and narrative fascinated many architects, perhaps because, our enemies might say, we knew more about books than about buildings.

If architecture is both concept and experience, space and use, structure and superficial image -- non-hierarchically -- then architecture should cease to separate these categories and instead merge them into unprecedented combinations of programs and spaces. “Crossprogramming,” “transprogramming,” “disprogramming:” I have elaborated on these concepts elsewhere, suggesting the displacement and mutual contamination of terms.

My own work in the 1970s constantly reiterated that there was no architecture without event, no architecture without action, without activities, without functions. Architecture was seen as the combination of spaces, events, and movements without any hierarchy or precedence among these concepts. The hierarchical cause-and-effect relationship between function and form is one of the great certainties of architectural thinking -- the one that lies behind that reassuring ideé recue of community life that tells us that we live in houses “designed to answer to our needs,” or in cities planned as machines to live in. Geborgenheit connotations of this notion go against both the real “pleasure” of architecture, in its unexpected combinations of terms, and the reality of contemporary urban life in its most stimulative, unsettling directions. Hence, in works like The Manhattan Transcripts, the

definition of architecture could not be form or walls, but had to be the combination of heterogeneous and incompatible terms.

Just as important is the spatialization that goes with the event. Such a concept is quite different from the project of the modern movement, which sought the affirmation of certainties in a unified utopia as opposed to our current questioning of multiple, fragmented, dislocated terrains.

A few years later, in an essay about the follies of the Parc de la Villette, Jacques Derrida expanded on the definition of event, calling it “the emergence of a disparate multiplicity.” I had constantly insisted, in our discussions and elsewhere, that these points called folies were points of activities, of programs, of events. Derrida elaborated on this concept, proposing the possibility of an “architecture of the event” that would “eventualize,” or open up that which, in our history or tradition, is understood to be fixed, essential, monumental. He had also suggested earlier that the word “event” shared roots with “invention,” hence the notion of the event, of the action-in-space, of the turning point, the invention.

This will not happen by imitating the past and eighteenth century ornaments. It also will not happen by simply commenting, through design, on the various dislocations and uncertainties of our contemporary condition. I do not believe it is possible, nor does it make sense, to design buildings that formally attempt to blur traditional structures, that is, that display forms that lie somewhere between abstraction and figuration, or between structure and ornament, or that are cut-up and dislocated for esthetic reasons. Architecture is not an illustrative art; it does not illustrate theories.

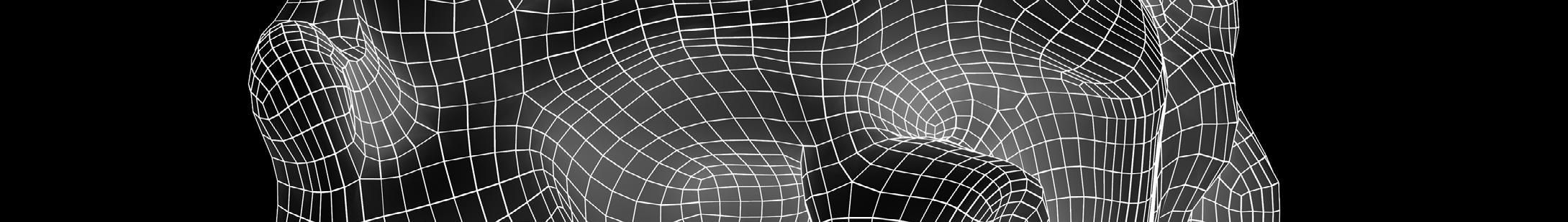

Schmarsow considered architectural space as the active creation of human "Koerpergefuehle" (feelings and conscious awareness of the body), as a reaction of man's physique, based mainly on physiological laws of human nature, projected into the outer world.

However, the architects were satisfied if the purpose was functionally expressed in the layout and from there transferred to the facade, while for Schmarsow the creation of space was the decisive factor and its purposeful (functional) organization only a natural symptom of all human activity.

With Eicken, Rudolf Metzger demands from any work of art primarily the clarification of our concept of the world. This is achieved in architecture by identification of architectural forms with human forms, and especially with human movements. Actually specific architectural forms, from the Greek column to the Gothic pointed arch, to the modern cantilever girder, represent frozen human movements. In other words, Metzger elaborates Lipps':7 theory of Einfuehlung (empathy) applied to architecture. Metzger is so one-sided in his concept of the identity of architectural forms and dynamic sensation (dynamische

Einfuehlung) that for him the categories of space and volume exist as little as those of function.

Hermann Soergel," the most important representative of the space concept, follows Schmarsow insofar as he considers space as the actual content of architecture and sees volume merely as means for the creation and definition of space Most decisive is Soergel's distinction between Daseinsraum (existential space, the objective real, imaginable space), Erscheinungsraum (visual space, i.e. the physiological, visually perceivable space), and finally Wirkungsraum (effectual space, i.e. the aesthetically impressive space). It is only the last which is created by the architect and to which the beholder reacts. Soergel distinguishes quite definitely between architecture as technique and architecture as art. Technique can be molded artistically, without losing its character as technique, art may have technical qualities without losing its quality as art. Technique means compulsion (material, economic, etc., limitations), art means liberty. Aesthetic effects based on technique, as those of industrial design, differ by principle from aesthetic effects based on art. Architecture as art is autonomous, in spite of its rational, technical, and

material data. The anti-functional viewpoint can hardly be pronounced more clearly.

Fritz Schumacher, who as city architect and city planner of Hamburg has created a great number of im- portant buildings, is the only practicing architect within this group which considers space the essence of architecture. He distinguishes among intellectual, sensuous and emotional effects of architecture, establishing the sensuous effects as the decisive ones. Thus he relegates functional considerations to a secondary role ("Kunstwirkung ist nicht Sachwirkung, sondern Bildwirkung"). He conceives of architecture as twofold creation of space by the limitations of volume. Twofold it is because for him the interior is perceivable only as a projection of con- cave parts into an imagined plane behind, while the exterior, the convex volume, is projected into the superior general space. Architecture, therefore, represents not merely the dualism of space and volume, but a threefold relationship. There exists: interior space; volume, determining interior as well as exterior space; and general exterior space. This threefold relationship can be perceived not only by visual experience but also by movement, successive action in time. Quite consistently, Schmacher explains stylistic differences by shifts within this threefold relationship of interior space, volume, and the comprehensive general space.se experimental art works were commenting once again on societal issues through architecture, contrasting on the

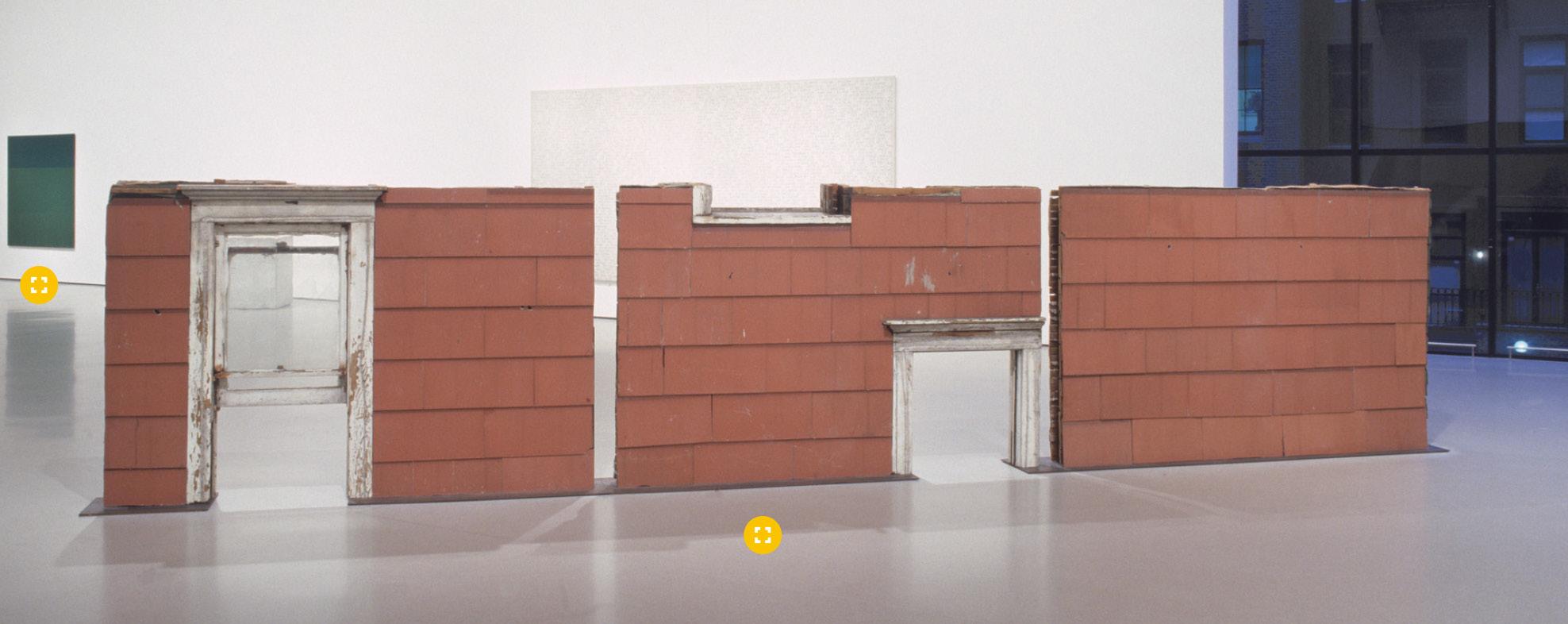

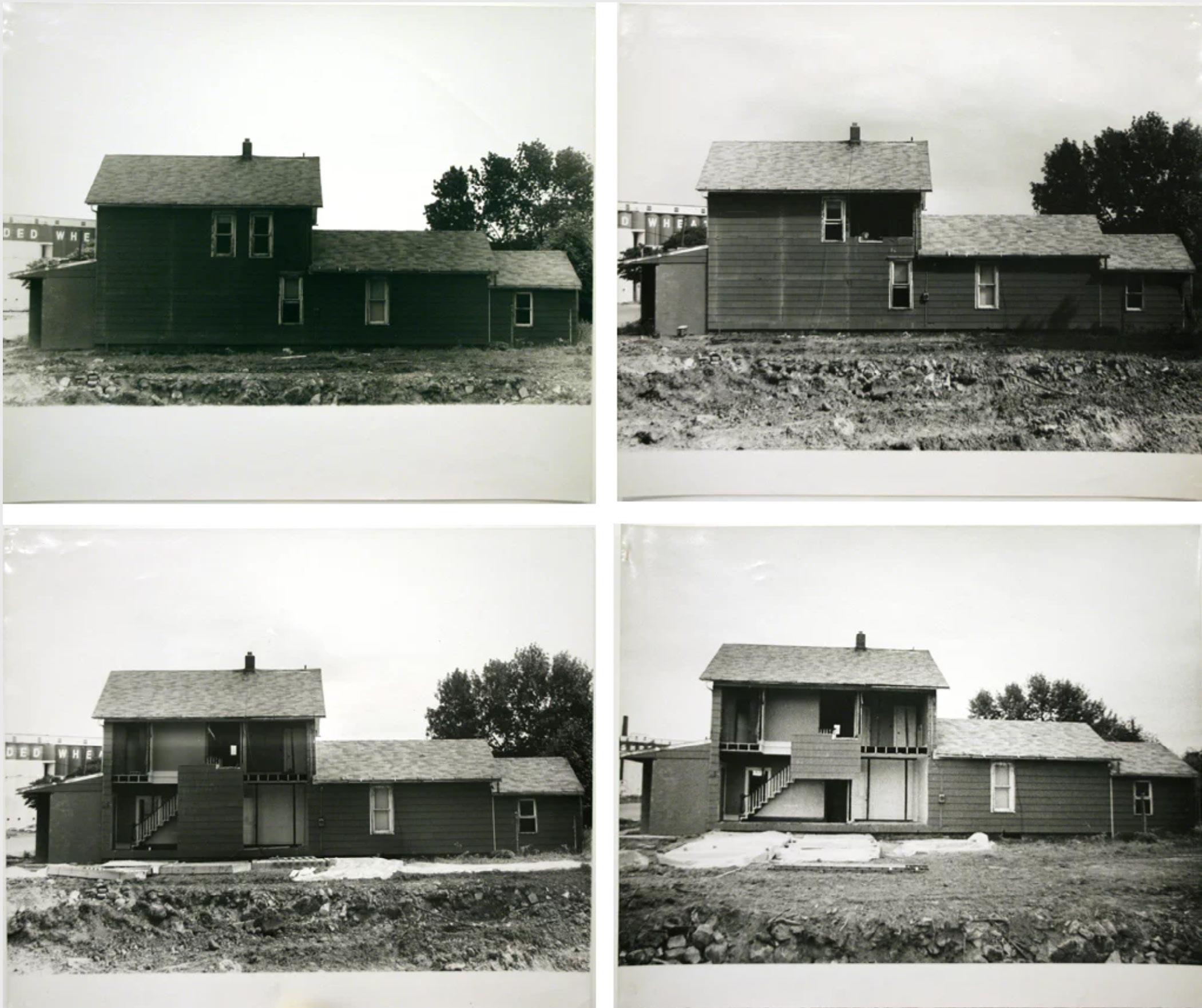

increasing desire for material accumulation, wealth and consumption. But most important of all they were creating a definitive contrast by constructing spaces of events by deconstructing it in the first place. This slight play of words gained them a very profound and successful paradoxicality in their work. Making their Architecture very much an event space, as it contained perceivable spaces as much as conceivable spaces.

TheW integration of space and volume as the basis of all architecture represents also the starting point for my own theories. To me, the integration of space and volume was also the starting point, modified, however, by emphasis on the time element. I interpreted the main differences between the various historical epochs primarily by the change of this time element in relation to space and volume. This time element means time in its aesthetic sense, that is the continuity of successive volume and space impressions. This continuity ("fliessender Vollzug") or discontinuity--the latter varying in its rhythm- depends on the architecturally established relationships among three factors: volume, space, and the time needed for their visual perception. This way the time element becomes immanent to all architecturally shaped space and volume. And it is the diversity of this relationship -a perpetual quality -by which the in- dividual styles differ from each other, independent from the functional purposes of each building

‘Architecture is always dream and function, expression of a utopia and instrument of a convenience’, wrote Roland Barthes in The Eiffel Tower and Other Mythologies. In this paper I wish to explore the way in which the language of modernist architecture and the dreams embedded within it impacted on the work of Gordon Matta-Clark (1943–1978). Unusually among artists of his generation, MattaClark was trained as an architect at Cornell University, where he was taught by some of the most eminent architectural theorists of the era and from where he graduated with a BArch in 1968.

The origin of the word Anarchitecture itself equally evades pinning down. While those who attended the meetings have generally attributed it to Matta-Clark, surviving participants also sometimes remember it as having been arrived at collectively; a combination of ‘anarchy’ and ‘architecture’ stumbled across through group discussion.6 Whatever its origin, the term Anarchitecture, expressing as it does a creative tension between Apollonian and Dionysian opposites, has come to summarise many of the concerns explored by Matta-Clark during his brief career.

The Anarchitecture show, then, was a kind of manifesto; but a manifesto of a tendency that

never existed, a temporary alliance of creative spirits that inhabited the same moment in history. A manifesto, perhaps, for a generation disillusioned with manifestos. Or, as Caroline Gooden put it, ‘Anarchitecture was a work in progress in Gordon’s mind’.

The first object he suggests for inclusion is a plain board with the words ‘NOTHING WORKS’ written on it. This fundamentally anti-functional statement, described in his letter as ‘a reaction to the prime-crime axium of modern designfighters’, stands in direct opposition to the whole ethos of utilitarian modernism. At the same time it approaches the life-experience of inhabitants of downtown New York in the early 1970s, as the city approached bankruptcy and garbage piled up on the streets. In a footnote, Louis Sullivan’s dictum ‘form follows function’ is manipulated through the distorting mirror of the artist’s compulsive punning to become ‘form fallows function’. If this wordplay means anything it implies that a rigid adherence to certain ideas of form will restrict an object or a building’s usefulness. An opposite approach might be to allow an object’s appearance to suggest spontaneous new uses, in the way that the carriage of a wrecked train suddenly becomes a bridge in the photograph included in the Anarchitecture show (fig.5). Further on in the same letter, Matta-Clark makes explicit his relationship to Le Corbusier, by suggesting

another idea for inclusion: ‘AN MACHINE FOR NOT LIVING WITH AN EXTRACT FROM CORBUSIER’S VERSO UN ARCHITEC (edge of paper destroyed) SHOWING THE VIRGIN MACHINE HE WANTS US ALL TO LIVE IN.’

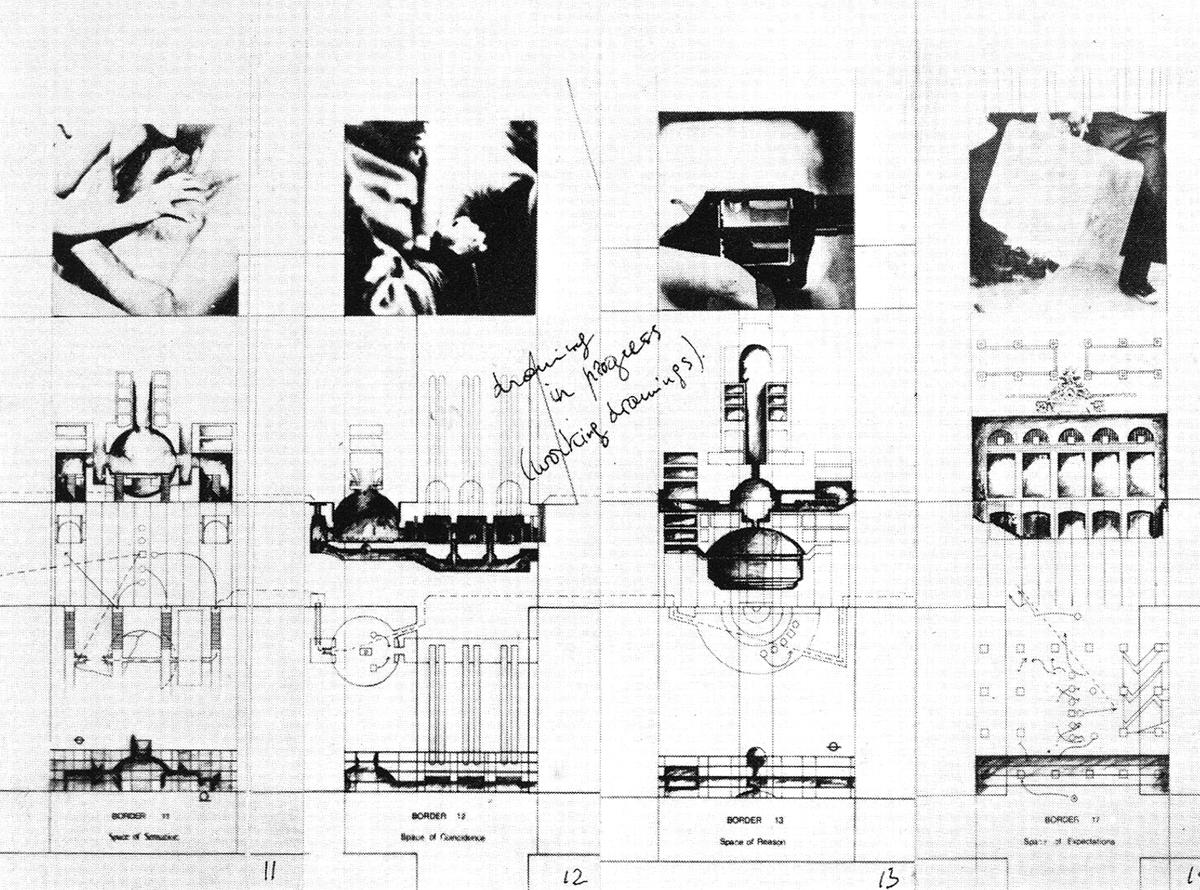

What are these images suggesting? Firstly, they are not meant to be read literally. On a metaphorical level they represent the opposite of the harmonious structuring of society and the urban environment that Le Corbusier believed was the highest aim of civilization. Anarchitecture celebrated the inner city in all its disorder and variety and crazy juxtaposition of eras and styles (fig.11). The forces of nature that picked up boats and piled them on top of one another both suggested new types of structures and alluded to the densely packed fabric of the inner city (fig.12).

SoHo, an area of near autonomy, seemingly beyond the control of city planning regulations, was, once the towers rose above it, overseen by their vertiginous façades. It was as if the world of finance was prophetically reasserting its dominance over the bohemian mini-state at its feet. Matta-Clark’s letter to the Group features a drawing of the Towers cancelled out with a bold cross and the caption ‘Erase all the Buildings on a Clear Horizon’.

One of Le Corbusier’s prime aims was to abolish the hidden infrastructure that lay beneath the streets, along with its unofficial inhabitants, making conduits for all services easily accessible. In contrast, Matta-Clark saw the underground as one of the last repositories of history in North America that had not disappeared under parking lots, and worried that it was now under threat from the everdeeper foundations of new buildings. Working within the influence of the surrealist tradition, he celebrated the unconscious, the irrational in the urban environment.

If, as Thomas Carlyle had written a century and a half earlier in Sartor Resartus,36 clothes could be ‘a warm movable house, a body round the body’, then architecture could be as flexible and movable as clothing. Sometimes architecture could be the body itself, giving shelter to the unborn, as in the photograph of a naked pregnant woman he proposed for inclusion in Anarchitecture; sometimes it housed the body after the spirit had departed, as in the images he proposed of graveyards.

In this way Matta-Clark created an architecture in two dimensions that still manages successfully to give the viewer access to a vanished three, or arguably four, dimensional experience. Just as the influence of Le Corbusier penetrated global consciousness principally through the pages of a book, it is the writings, photographs, drawings and films that continue to disseminate MattaClark’s vision today. Anarchitecture was, as he wrote on an art card, ‘about making space without building it’. At the same time, those ideas of Matta-Clark’s that could be termed more directly architectural worked from the bottom up, in a reversal of the usual pattern of the architect-client relationship. By observing the lives of those who were forced to live on the street, as he put it ‘beyond between and without walls putting to waste the most presumptuous building plans’,39 he came up with prototype forms, free of any commodity value, which could be used by anyone to create a shelter.

THE SHOW AND THE WORK. KEEPING IT AN ONGOING PROCESS. NOT FINISHING JUST KEEPING GOING AND STARTING OVER AND OVER.

1. "It can be defined as a space for sensations, the materiality of space can be acknowledged only by the materiality of the subject."

2. "Making their Architecture very much an event space, as it contained perceivable spaces as much as conceivable spaces."

6. "The paradox is not about the impossibility of perceiving both architectural concept and real space at the same time but about the impossibility of questioning the nature of space and at the same time making or experiencing a real space."

3. "Space and time were "categories" that enabled the classification of "sensory knowledge." Space became absolute. Object before the subject, it dominated senses and bodies by containing them."

7. "Architecture constitutes the reality of experience while this reality gets in the way of the overall vision. Architecture constitutes the abstraction of absolute truth, while this very truth gets in the way of feeling."

4. "Space was generally accepted as a cosa mentale, a sort of all-embracing set with subsets such as literary space, ideological space, and psychoanalytical space."

5. "Architecture becomes a truly autonomous organism. Forms do not follow functions but refer to other forms, and functions relate to symbols. Ultimately architecture frees itself from reality altogether. Form does not need to call for external justifications. "

8. "Architecture is always the expression of a lack, a shortcoming, a noncompletion. It always misses something, either reality or concept. Architecture is both being and nonbeing. The only alternative to the paradox is silence, a final nihilistic statement that might provide modern architectural history with its ultimate punchline, its self-annihilation."

1. The experiential dimension of space is contingent upon the bodily presence of a material subject, which allows for the recognition of the tangible properties of the environment.

surpasses the limitations of reality, where form exists independently of external justifications and can exist purely as an expressive entity.

2. Transforming experience into a dynamic space that accommodated abstract concepts and physical spaces that could be sensed and explored.

3. Space and time were used as tools for categorizing sensory experiences. Space was often viewed as an objective entity that existed independently of human perception, subordinating the senses and bodies by limiting them within its boundaries.

6. The paradox does not involve the inability to perceive architectural concepts and physical space simultaneously but rather the challenge of examining space's nature while creating or experiencing it in a tangible form.

7. Architecture's emphasis on form and function can obstruct a comprehensive outlook. Architecture embodies the pursuit of universal principles, but this pursuit can compromise our ability to connect with the visceral and subjective aspects of the built environment.

4. Literary, ideological, and psychoanalytic space, each representing a distinct conceptual framework for understanding the spatial dimensions of human experience.

5. Architecture attains a state of autonomy, where forms are not simply practical but self-referential, and functions acquire symbolic significance. Architecture

8. Architecture embodies a sense of incompleteness, insufficiency, or deficiency, either in relation to reality or to abstract ideas. It embodies both existence and nonexistence. The only way to escape this paradox is through silence, which might represent a nihilistic conclusion, a final statement.

9. "Architecture should cease to separate these categories and instead merge them into unprecedented combinations of programs and spaces. “Crossprogramming,” “transprogramming,” “disprogramming:”

10. “He distinguishes among intellectual, sensuous and emotional effects of architecture, establishing the sensuous effects as the decisive ones. Thus he relegates functional considerations to a secondary role。”

13. "Anarchitecture celebrated the inner city in all its disorder and variety and crazy juxtaposition of eras and styles.“

14. "Clothes could be ‘a warm movable house, a body round thy body’, then architecture could be as flexible and movable as clothing。"

11. "This continuity or discontinuity--the latter varying in its rhythm- depends on the architecturally established relationships among three factors: volume, space, and the time needed for their visual perception."

15. "Beyond between and without walls putting to waste the most presumptuous building plans, free of any commodity value, which could be used by anyone to create a shelter."

12. "Architecture is always dream and function, expression of a utopia and instrument of a convenience."

16. “Keeping it an ongoing process. Not finishing just keeping going and starting over and over.”

9. Architecture ought to eliminate the boundaries between different categories and instead integrate them in novel and innovative combinations of functions and spaces. Terms like 'crossprogramming,' 'transprogramming,' and 'disprogramming' reflect a dynamic and adaptable approach.

13. Anarchitecture exalted the urban landscape in all its chaos and diversity, with its eclectic mix of juxtaposition periods and architectural styles.

10. Differences between the intellectual, sensual, and emotional impacts of architecture. By prioritizing the sensual effects, the importance of functional aspects diminishes.

14. As clothing can serve as a flexible and comfortable residence for the human form, architecture should aspire to be as versatile and mobile as garments, accommodating the needs and desires of its inhabitants.

11. The presence or absence of a sense of continuity, which may vary in its pace and intensity, is determined by the interplay of three factors: the spatial volume, the spatial configuration, and the temporal duration required for their visual apprehension.

15. Breaking free from walls and boundaries, rejecting the hubris of grand architectural designs, and being stripped of any commercial worth, it could serve as a universal refuge accessible to all.

12. Architecture is a fusion of vision and purpose, encompassing the dual roles of an idealistic manifesto and a pragmatic tool.

16. The essential approach is to sustain an unceasing and iterative progression, without the constraint of finalization, persisting in recommencing and renewing the process.

In the movie "The Father" , it is the final monologue of the main character Anthony, who is suffering from Alzheimer's disease, at the end of the movie and his life. I prefer the Chinese translation "The father trapped in time" , which is a metaphor for the symptoms of the disease in Alzheimer's patients. It determines the title of this thesis, Time Paradox, and the direction of research and discussion. The aging of the population is becoming more and more significant as people's living conditions improve. Those who have Alzheimer's disease need more attention from this society. It is as if they are caught in the vortex of time, gradually disconnected from their families and

community, and finally leave the world in a void. Aphasia is the state they face, but worst of all, the only memories they rely on become blurred and confused as their condition worsens. The familiarity of the environment is like a rope that can pull the patient when caught in a whirlpool. While current medicine is still unable to cure this condition, is it possible that we can use technology to recreate the world in consciousness so that they are comfortable and safe when disconnected from reality? It is better than feeling panic and fear due to a very different environment from the perceived familiarity.

"I feel as if I am losing all my leaves. The branches and the wind and the rain.

I.. I have nowhere to put my head down anymore. But I know my watch is on my waist that I do know. For the journey..."

2020 Florian Zeller, The Father

"The most resilient parasite is an idea. A single idea from the human mind can build cities, create empires, and transform the world, and it's a sensation that transcends space and time." -

Cobb"In a dream, you can bend and manipulate the architecture of the world around you. You can create your own spaces, shape them according to your desires, and experience sensations that are beyond the boundaries of reality." -

Eames

Eames

"In dreams, we can travel through space and time, experience sensations that are indistinguishable from reality, and explore the depths of our subconscious. It's a realm where our perceptions of space and sensation are only limited by our imagination." -

Mal"Dreams are a world of infinite possibilities, where space and sensation are not bound by the laws of physics. They are a canvas for our imagination, where we can paint our own reality and explore the depths of our subconscious." -

Dom

"Our senses are the gateway to our memories. The smell of a familiar place, the taste of a childhood treat, the sound of a loved one's voice - they all trigger memories that can transport us to another time and place."

"Our memories are like threads that weave the tapestry of our lives. They can be fragile, easily frayed or lost, but they also hold the power to bring us comfort and joy, to transport us back in time and relive moments that are etched in our hearts and minds." - Brenda

-

Nate Fisher

Chenowith

The allotted at 349 facade The

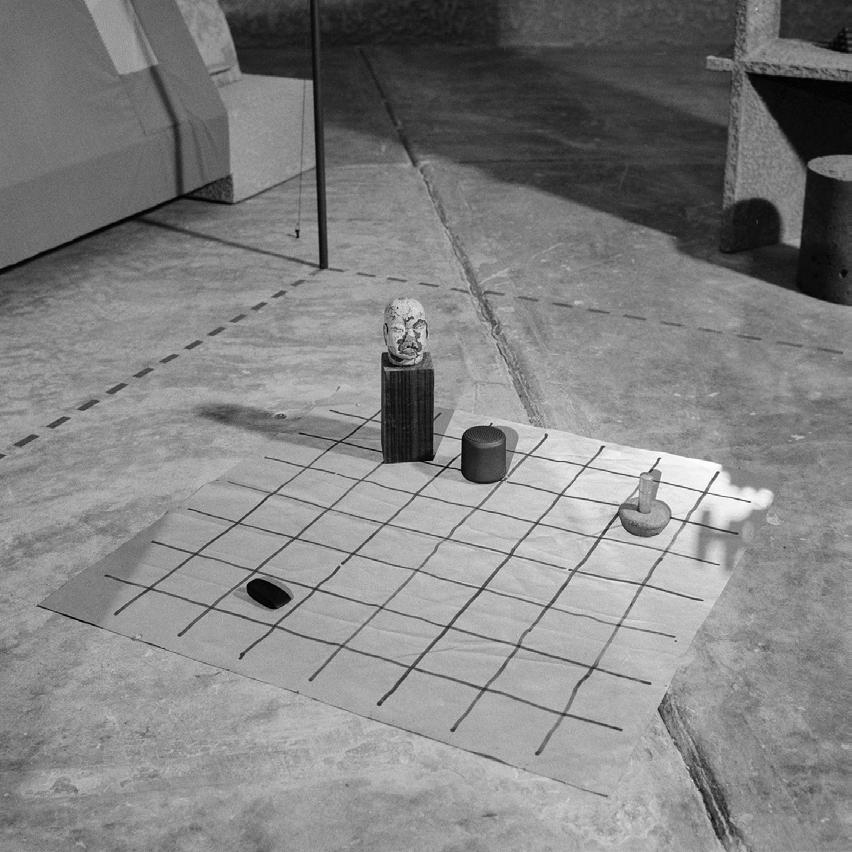

The city planning commission of Niagara Falls, New York, allotted Matta-Clark ten days to carve up a condemned house 349 Erie Avenue before it was demolished. He divided the facade into a grid and then removed each rectangle individually. The result was eight separate building fragments.

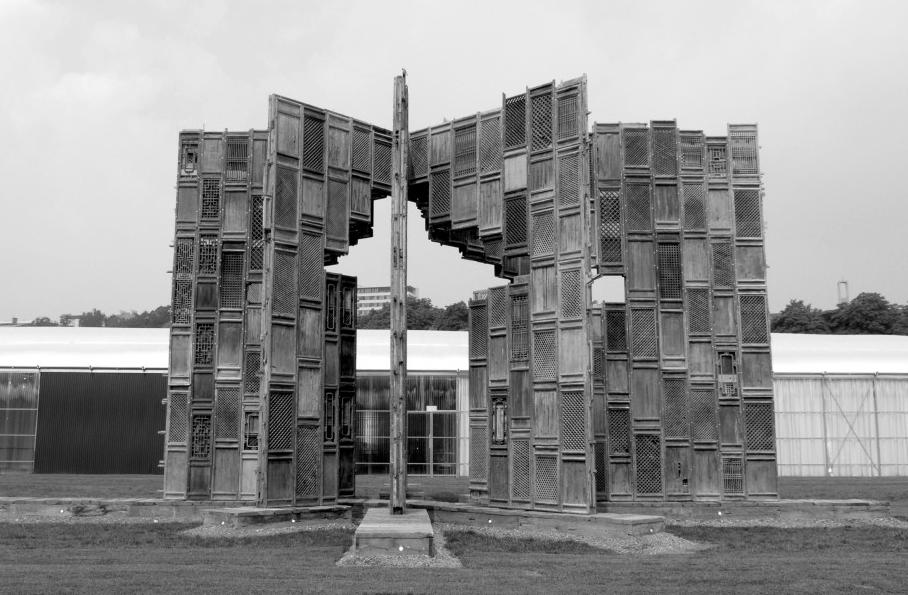

Template relates to change in China. It is composed of wooden doors and windows salvaged from Ming and Qing Dynasty houses which had been demolished to make way for new development. On displaying the installation outdoors in Germany in 2007, the structure collapsed after being exposed to wind and rain. Ai Weiwei embraced this change: “When I saw how the site had collapsed – turned into some other shape – I was quite impressed,” he told Bloomberg. “It comes from ruins and now it’s really a ruin”.

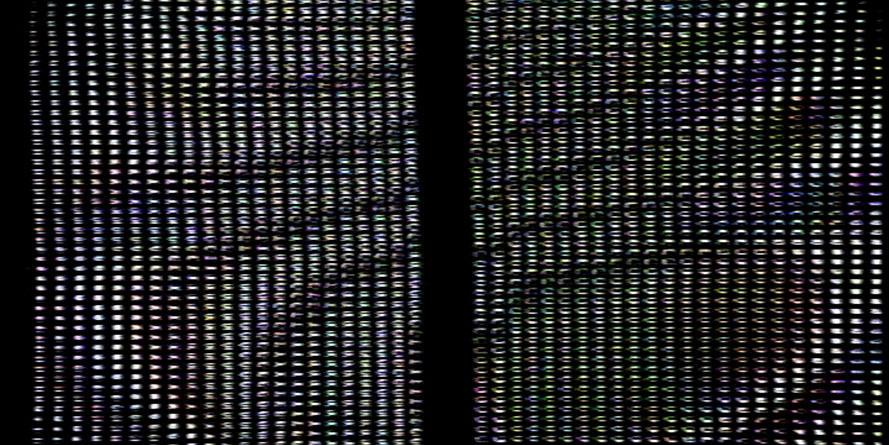

Equal Time, he sets up a minimalist arrangement, respectively on the left and right side to the opposite side.“

”In this work, the field of Hill’s experimentation

experimentation is the synchronization of visual and linguistic elements. For arrangement, whereby two identical panels with grid patterns, starting of the monitor, slowly move across the screen against a black background

"Bread is cut daily, but will not ever receive bespoke prosthetics; this seems futile, for the next cut is always imminent. Instead of a missing parts replacement, we replace the entire bread: bread can be regarded as its own prosthetic."

"What is interesting in the world are the grey areas. So what I have designed is a threshold. It's not possible for an architect to design a space - such a concept does not exist. Instead, we design the thresholds and the limits: the walls, windows, doors and so on. And people have feelings about these elements and put them together and create the sensation of a space. I'm interested in designing the elements

that give the impression of a space - which is why I like doors. The dialogue between the container and the contained, the boundaries and the space within them, is an obsession in contemporary culture, where the node is more important than the object. That's why architecture must work at the limits, not invent the shape and language but straddle two worlds, on the knife edge."

"Architecture is often secondary, invisible, but at certain moments, like when you climb a staircase or a ramp, there's a tension between your body and the building. Taking visitors up to this usually unvisited stratum evidences the energy that's necessary when challenging gravity. This is a standard element of architecture, but elevators and escalators meant the physical distance between the ground and upper levels is often forgotten. Our proposal draws attention to gravity as a fact of architecture."

"Refugio Justo, is a living space for a fictional explorer: in which a ‘signal-less’ life can be sustained. A diorama of sorts, this space seeks to display this character’s life by means of a series of sculptures in the form of objects and artifacts that represent and symbolize the daily routine of the user. Elements that recall, through their interactions with the most basic forms of life, a way of relating and reconnecting with nature, with the essential, while questioning our contemporary way of living— behavioral patterns, customs, and uses we take for granted. By creating an ephemeral space, the installation also explores themes of temporality in architecture, calling into question the very notion of permanece and property."

Societal Issues:

Aging Population Consumerist

Program:

Immersive Museum

Youth-oriented

Generation Gap

the fragmentation and alienation experienced by the elderly and unwel

Large-scale Community Center

raise consciousness, awareness, and attention

Activities Center reintegration of aging society (dementia and unwell)

Public Park healthy and environmental friendly

Blurring boundaries

Merging memories

Reimagining the built environment

ignite a cultural reawakening, break down the isolation between generations and social groups

Dataset / Initial:

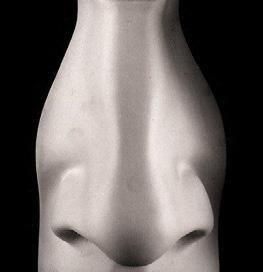

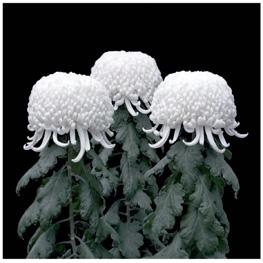

Human Body

Natural Elements

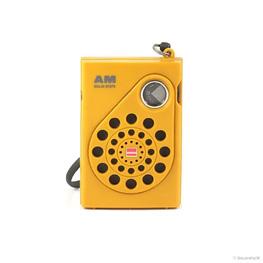

Daily Appliances

Images

Technique:

Generated Images

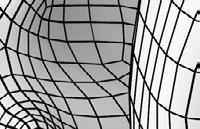

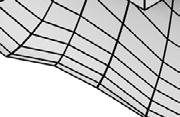

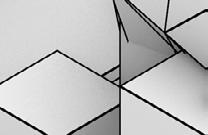

Design:

Building Forms

Textures & Materials

Surface Mapping

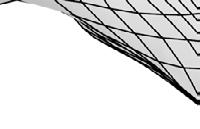

abstract-yet-tangible fluid & solid

scales change resolutions change

mixed-use cross-program

1. find the tension and possibilities in objects

2. blur the boundaries of objects full of memories

3. mimic the elderly's inner world

4. respond to the cultural contradiction

By integrating sensation, psychology, and interaction, I draw inspiration from techniques using Style Generative Adversarial Network. The dataset prepared for styleGAN can be categorified into body parts, natural elements, and daily appliances. They can respond and influence my project well. They are full of memories. Every image may tell a unique story, but the four categories can help the machine know more about images' similarities and differences as the creator intends.

I took a novel approach by embracing dementia as a source of nature, I leveraged machine learning techniques to mimic intricate spaces reflect the delicate dance between order and chaos, clarity complexity experienced by individuals with dementia.

inspiration. Understanding its paradoxical intricate and nuanced states of mind. The clarity and confusion, simplicity and

abstract-yet-tangible

My design encompasses a captivating and a vibrant community activity hub. spaces encourage unity and inclusivity, boundaries and reimagining the built

captivating museum hub. These inclusivity, blurring built environment.

Reintegration became my guiding principle as I envisioned transformative spaces that could foster a sense of belonging and connection within the community.

Leveraging the power of machine project reflect and mimic these

machine learning, the spaces within the these intricate states of mind.

One of the critical aspects I considered was the profound impact of deterioration and dementia on the lives of the elderly and unwell. These conditions present unique challenges, including errors in aesthetics, misremembering, disruption in legibility, and erasure. The project takes these challenges head-on, emphasizing the importance of aesthetics and cultural significance in addressing them.

By embracing the disruptions and errors of dementia, the thesis strives to create legible, engaging, and nurturing environments for individuals experiencing memory loss.

Beyond the architectural realm, the project extends to urban intervention. I seek to revitalize the urban environment and create stronger connections with the surroundings. By incorporating a large-scale community center in the core of Downtown, I aim to promote social cohesion and interactions among diverse groups, addressing the needs of those affected by dementia.

As this chapter of my journey comes to a close, I'm filled with deep gratitude for the pivotal roles you've played. To my dear family, your unwavering support has been my rock, reminding me that love knows no bounds.

Your guidance and wisdom have illuminated my path, turning challenges into stepping stones. Your dedication to my growth has left an indelible mark on my journey. Your insights have not only shaped my research but also my perspective on academia.

Your expertise and insights have paved the way for this achievement. Your meticulous attention to detail and thoughtful feedback have been invaluable in preparing me for this endeavor.

To those exceptional instructors who inspired me, Peter Testa, Dwayne Oyler, Karel Klein

Your passion and dedication have been a guiding light. Your knowledge and enthusiasm ignited my own thirst for learning and exploration.

Jinxin Xu, Michael Webb, Pan Tan, Shang Chu, Wan-Yu Chen, Wei-Hung Chen, Yiyu Zhou

You've added vivid colors of joy to the canvas of my experiences. Your companionship, encouragement, and shared laughter have made this journey unforgettable.

And to SCI-Arc, you've provided not just an education, but a nurturing environment where dreams took shape. The lessons learned within your walls will continue to resonate throughout my life.

Graduate Thesis - 2023 Summer