Re-invent Ancestral Hall

Thesis Statement

Close up of the Architectural Model

Historically, religious practices have been the primary drivers of beautiful architecture.

Which in turn has served as a vessel for cultural expression and preservation. Architecture has cultivated discourse, shaped culture, and prevented it from fading away—it is the proof of a culture.

This thesis investigates the modern feasibility of using architecture to convey culture by examining the Ancestral Hall of Southeast China and the practice of ancestral worship. As younger generations of Cantonese people have grown up overseas, many have lost touch with their traditions. Without the physical presence of architecture, these cultural rituals are inaccessible. Unlike churches, ancestral halls do not worship a universal deity, and the fragmentation of clans has made it challenging to create architecture that serves this purpose. However, the generational migration of Cantonese people underscores the importance of cultural unity. Drawing on examples from other immigrant groups, a place of worship could unite all people of Cantonese descent, making the ancestral hall a potential solution.

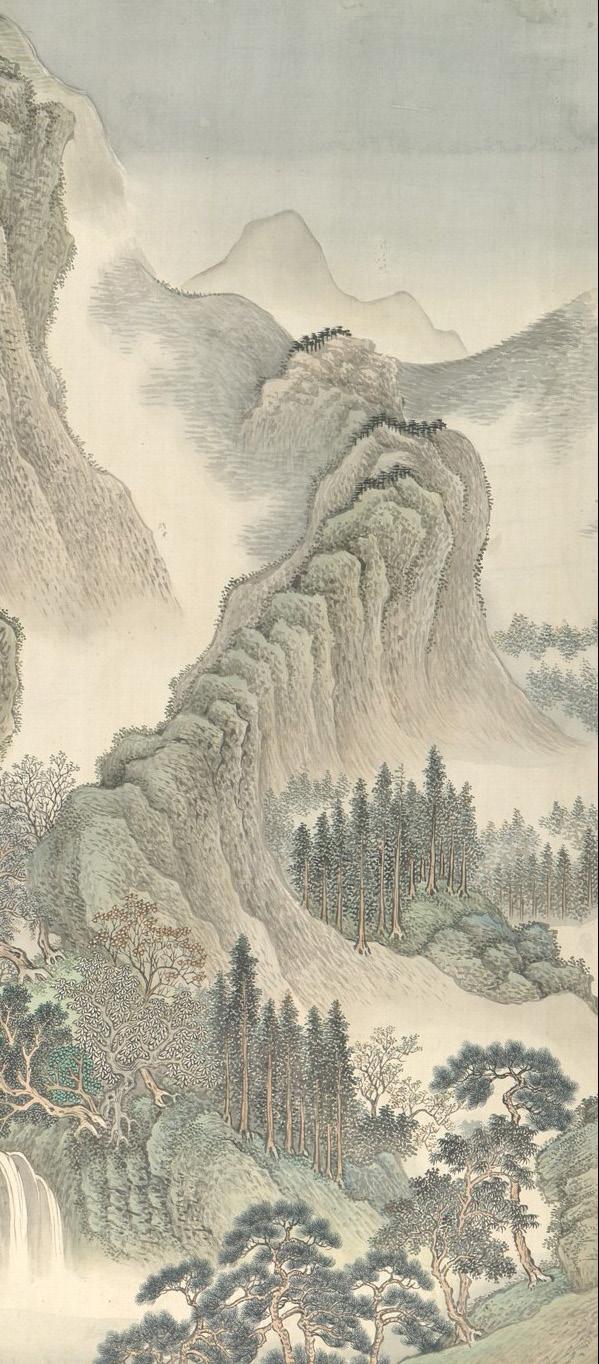

A new ancestral hall overseas could convey traditional culture by combining elements of traditional Chinese architecture with modern building technology, updating its functionality to serve a broader audience. The design strategy incorporates aspects of mountains and water, inspired by Chinese horizontal viewing scrolls. The roof massing reflects a continuous range of peaks and ravines, while the use of mass timber enhances the hall’s warmth and welcoming atmosphere, allowing for a larger footprint to accommodate multiple worshipers. Traditional ornaments are tailored to each event and the private rituals each family wishes to perform. While a traditional ancestral hall balances relationships within a clan, the new hall would balance relationships among clans in the same region. This ancestral hall would unify the community, renew interest in traditional culture, and create, convey, and preserve culture, as architecture is meant to do. Y

Research

History and Culture

Ancestral Tablets in Pang Ancestral Hall

The “Punti”, the “Hakkah”, the “Tanka” and the “Hoklo”are the four major local culture group in Hong Kong. These two clans resulted in two types of ancestral halls in Hong Kong. It is unclear how many functional ancestral halls remain in Hong Kong, but a search of the term “Ancestral Hall” on the Antiquities Advisory Board would return 165 records. These are the halls that have significant cultural and architectural value to the region. Ancestral Hall and its related activities are protected under the Basic Law of Hong Kong and the New Territories Ordinance. The “Punti” (Local people) ancestral halls are larger, more extravagant, and likely to be a declared monument. While the “Hakkah” (Guest people) ancestral halls are smaller, with fewer ancestral tablets but greater in numbers. The Punti people moved to Hong Kong over 700 years ago with a large number of the clan, they came with wealth and built their village on the flat plains. Their relative wealth and local influence allowed them to build

grand extravagant ancestral halls. The Hakkah people have moved to Hong Kong in the last 200 years, escaping the various political turmoil from the Taiping Rebellion. Since they do not belong to the local clans, they coined the term “Hakkah”, which translates as the guest people/ the outsider in the 1900s. They settled in smaller groups, on less advantageous land in the mountain. The Hakkah people were relatively poorer in pre-colonial times, their ancestral hall would therefore be smaller and less decorative. The “Tanka” and “Hoklo” people are the people who live on the water, they did not have significant architecture such as the ancestral halls, and will be omitted from this chapter.

The “Punti” Ancestral Halls

The Punti people moved to Hong Kong over 700 years ago with a massive population, they came with wealth and built their village on the flat plains, where they could get plenty of access to water and growable land. They built their village with walls, to protect themselves from the private and the outsiders and became the archetype of Hong Kong’s native village “Wai Tsuen” (Walled Village), and their name became the “Wai Tou” people (people who live in the wall). Officially they are recognized as the “Punti”local people of Hong Kong. Punti clans often had greater wealth and official government titles; they were permitted to build grand ancestral halls for multiple alters for multiple ancestors. When Hong Kong was first incorporated, the colonial government did not give many rights to its Chinese residents, which led to the nonrecognition of native statues to its residents. However, when the Convention for

the Extension of Hong Kong Territory was signed, the colonial government granted special rights to the people descended through the male line from a person who was in 1898, a resident of an established village in the New Territories of Hong Kong. The traditional rights and interests of the indigenous inhabitants of the “New Territories” are lawfully protected under the colonial rule, and later HKSAR. A series of different political policies resulted in different cultural landscapes in the same city. Despite Hong Kong being under colonial rule for a hundred years, it ironically has better preservation for traditional architecture and practice than adjacent China.

Dim Dang ritual at Tang Ancestral Hall in Ha Tsuen

Main Hall of the Sam Tung Uk Village

The “Hakkah” Ancestral Halls

The Hakkah people have moved to Hong Kong in the last 200 years, escaping the various political turmoil from the Taiping Rebellion. Since they do not belong to the local clans, they coined the term “Hakkah”, which translates as the guest people/ the outsider in the 1900s. They usually move in small numbers, where they would only have their immediate family as they leave their larger clan behind for a better life down south. They settled in smaller groups, on less advantageous land in the mountain. The Hakkah people were relatively poorer in the pre-colonial times, their ancestral hall would therefore be smaller and less decorative. However, there would always be a sitting sculpture of Kwun Yam on the left side of the main hall. Signafyin that they will receive more children through Kwum Yam and strengthen their clan. Most of the Hakkah clan’s ancestral halls are embedded near or inside the domestic houses. There were few major clashes that resulted in the Hakkah Punti Clan Wars. But slowly, the two culture clans learned to co-exsit peacefully and became the major players of Eastern Culture of Hong Kong.

Typology

Spatial configuration of Chinese building

Chinese architecture has a typical practice of combining “yin” (positive space) and “yan” (negative space) to achieve spatial harmony. Although the “yin” translates to negative, it actually represents the positive space in architecture, while “yan” means positive, it represents the negative space in architecture. In architecture, a positive space is the space of occupancy, where there would be a roof covered and enclosed on at least two sides. However, in Chinese architecture, since the positive space is enclosed and dark, it is therefore referred to as the space of “yin”, the space of negative power. The negative space is often recognized as the courtyard type. It could be enclosed on all four sides and remain completely private. It is recognized as the space of “yan” with positive energy because it is the space where light penetrates, bringing warmth and shine.

There a many combinations of spaces of “yin” and “yan”/ positive and negative spaces. In traditional Chinese architecture, the combination could go up to nine positive spaces with eight courtyards, it is only used in residential plans of the great power in northern China. It is not applicable to ancestral halls in southeast China, as the region is far from the traditional political power. Most often seen in ancestral halls in this area are the single hall type, the double halls type, and the triple halls type. They each have their function and spatial designation in the village. Some might also take up the function as a town hall, some will only remain as a place of remembrance.

Single Hall Single Courtyard

Section Diagram of a Single Hall Type

Typically seen in memorial halls and ancestral halls for a single family, this is the most basic, simple type of hall type. It is either established to commemorate a single ancestor with great accomplishment or it was the first ancestral hall the family had built when they first settled in Hong Kong. Most commonly seen in the Hakkah Clan, the single hall type ancestral hall is built to commemorate one or a few ancestors in the family. It could either have a courtyard or no courtyard at all. Some would have a courtyard by adding a non-functional part at the entrance with two walls on the side, but such a courtyard would be too small for gathering; some are standalone ancestral halls, but most are found embedded inside the walled village. Which is a manifesto of the term of「 庶人祭於寢」.

Although in its most simplified form, the single hall type is rare to see than the two halls one courtyard counter-

part. Since it is small in footprint and has very few members it doesn’t carry the function of a town hall or clan gathering and, therefore receives very little funding for upkeep. Most of the single-hall type ancestral halls in Hong Kong are facing the danger of rapid deterioration as the descendants moved overseas and forfeited many traditional practices such as the Dim Dang ritual, Ching Ming, Double Nine, and or Chinese Festival gathering. The single hall type is often overlooked by historical preservation as it was deemed to have very little architectural merit; however, it is the strongest representation of ancestral worship in Chinese culture as it demonstrates that ancestral worship is a practice of all people.

Plan Diagram of a Single Hall Type

Double Hall Single Courtyard

Section Diagram of a Double Hall Type

Most ancestral halls are in the twohall-one courtyard type, this is the most typical, commonly seen type of traditional architecture. It has the widest application in the program and it is also the largest format a none gentry family is allowed to build for their clan. The courtyard often functions as a gathering place in front of the ancestor while the front hall functions as an informational space upon entry. Double hall type ancestral halls are also the most often seen ancestral halls nowadays since it was widely constructed and financially well kept by their descendants. Both Punti and Hakka clans constructed various types of double hall type architecture. Some would only have a simple courtyard, some would even have side chambers beside to courtyard to maintain upkeep. Depending on the size of the clan and the footprint of the ancestral hall, the double hall type could have up to three alters and multiple ancestral

tablets for generations of ancestors. The Man’s Ancestral Hall in Tai Po is a signature double hall-type ancestral hall in Hong Kong. With 500 years of history, the Man’s Ancestral Hall in Tai Po was constructed on the standard footprint of the Ming dynasty, which is rather large by today’s standards. Wealthy families with no official titles often build grand double hall-type ancestral halls. A double hall type with a courtyard could serve all of the functions of an ancestral hall. Including but not limited to the Dim Dang ritual, Da Jiu Festival, Group worship and/ or Autumn Festival, etc. Some could even serve as the village hall for election and/ or wedding venue.

Plan Diagram of a Double Hall Type

Triple Hall Double Courtyard

Section Diagram of a Triple Hall Type

entry families with wealth to afford such grand gestures for their ancestors. Three hall types are usually only seen in the ancestral hall and the study hall near the ancestral hall. The study hall is another display of clan power where the family could afford to build a school to educate their descent to continue holding office in the local government. Several ancestral halls would also have guest houses in their proximity as they would play host to guests and their counterparts from northern China.

Typically only seen in Punti’s “Five Great Clans of the New Territories”, which are “Tang (鄧), Man (文), Hau ( 侯), Pang (彭) and Liu (廖). The family has strong financial standing through its massive decedents and often held official titles in various political offices since the Qing dynasty. This typology is almost exclusive to the village gentry, who would also have their ancestral hall dubbed as the village

gathering place for all people. The official election would be held at these halls till this day. Triple Halls are considered a rare type in Hong Kong as Hong Kong was far from the northern political power center of ancient China, and very few families had reached the statues to build a triple hall type for their ancestors and descendants.

「凡品官之家,立祠堂于正寢之東,為屋 三間,外為中門,中門為兩階,皆三級,東 曰阼階,西曰西階,階下隨地廣狹,以屋 覆之,令可容家衆敘立,又為遺書衣物 祭器庫及神廚於其東,繚以外垣,別為 外門,常加扃閉。」

Plan Diagram of a Triple Hall Type

Tectonic

Front Hall Structural Diagram of Tang Ancestral Hall in Ping Shan

Ancestral Halls incorporate a wide range of tectonics from traditional architecture and make it unique to its program.

Chinese Architecture developed a series of unique tectonics that influenced the rest of East Asia. To a Western audience, Chinese architecture may be indistinguishable at first glance; however, a temple and a grand house are deeds very different. An ancestral hall serves both sacred and domestic programming and, therefore looks and structure both like a temple and a domestic house. This ambiguity contributes greatly to the popularity of an ancestral hall and strengthens the political power of the local clans. Most ancestral halls have similar tec-

tonics, but each clan could also have its specialty. From the roof to the bottom of the cornerstone. Each clan does it a little bit differently. All the tectonics and their ornaments have special meaning to the family and its particular period of construction. Many wealthy families would also take the liberty to dress their columns and beams, creating unique wooden carvings for their tectonic elements. These decorated tectonics are the symbolism of Cantonese culture and carry a great amount of history and identity of the city of Hong Kong.

Roof and its ornaments in Tang Chung Ling Ancestral Hall

Tou-Kung Chinese Order

Qing Kung-Ch’eng-Tso-Fa

Structural Wooden Frame

Structural and Eave Ornaments at Pang Ancestral Hall

Beams and brackets are the most crucial structural components of Chinese traditional architecture. It is the middle tectonic that holds up the overall framework of the building. In contrast to the western stick and frame wooden method, the traditional method would thrust the roof to transfer downward instead of spending horizontally, it also allows fewer uses of nails and makes repair and replacement much more convenient. The complexity of the bracket often displays the status of the family. Adding on to the layer of complexity, many families would have their wooden brackets decorated with excessive ornaments. Detailing every corner visible, these wooden bracket combines wooden carving and painting artistry.

Similar to roof ridges, the patterns used on this wooden bracket are often the same, from floral to fruits and animal figures. They all represent the good fortune and hope of prosperity of the family. However, some exclusive Chinese folk tales could also be found in these wooden brackets. Folk tales such as “Eight Immortals Crossing the

Sea”, or “Peach Club” hosted by Queen Mother of the West.

This wooden bracket has the most engineering value and the aesthetic value of the ancestral halls. The front porch would usually showcase the complicated structure of toukung, where the weight of the roof was transferred to the front columns; the front hall would usually have the more visually complicated lifting beam frame, where the weight from the roof could be transferred onto, and shift toward to the columns on the side. The beams are usually very decorated as the visitor can easily access them by looking upward. The back hall, which is usually taller and larger, would use more structural sound through beam frames that require a larger timber size. The through-beam beam frame would have some large prints on its component due to its distance from the viewer’s eye.

Diagram of Weight Transformation

Structural Ornaments at Tang’s Kun Ting Study Hall in Ping Shan

Gegiake of Tang Chung Ling Ancestral Hall

Purling

Cross Beam at Sam Tung Uk Village

Depending on the size of the structure, there are various sizes of beam and purling layouts. Smaller wooden structures usually have up to the fifth purling beam where it raises to a maximum of 70% slop; medium-sized wooden structures usually have up to the seventh purling beam that raises to a maximum of 90-85% slop; largesize wooden structures usually have up to the ninth purling beam that reaches to the maximum 100% slope with ping-shui. The greater the structure, the larger the beam would be, as it approaches the eave.

“The pitch of each section of the rafter is increased from the eave up towards the ridge. The lowest section is a 50% slope, the next 70%; the next, 80%; to the 90% rise of the top section is added a “ping-shui” of 4 Tou-K’ou, making approximately a 100% or 45% slope.” (Liang, 4)

The size of the purling stays relatively the same. In many traditional Chinese architecture, they are often neglected as they are not as structurally exposed as the cross beam (aka purling beam) and therefore have less room to be decorative. However, the

location of these purling is perfect for hanging lanterns for festivals, and it was referred to as the “cross beam” in Cantonese opposite the actual beam that ran across each purling Due to its unique location, more decorative purling are developed just for the sake of hanging lanterns, therefore the once a year Dim Deng ritual was manifested due to these special purling. Dim Deng ritual is a special clan-wide activity native to the Cantonese population. Since the term “Dim Deng” (lighting the lantern/candle) is phonetically similar to the phrase【添丁】 , it is a ritual to announce the birth of male descent (after he turned one year of age) within the family to their ancestors. It is one of the largest and most unique events held in the ancestral hall, and the special purling to hold the lanterns is also denoted a special blessing to the new family members.

Beam Frame distribution Diagram

Rituals

Six foot large scale lantern for Dim Deng

Dim Deng is the most widely observed ritual in Cantonese culture. It is hosted during the Lantern Festival each year. Members of the clan gather to hang and raise one to three lanterns in each hall as a sign of passage in the family. The largest lantern can sometimes be six feet tall. The lanterns are inscribed with the word decedents wish to pass to their ancestors, mostly to share the good news of a new birth within the family. This ritual could be performed in front of the ancestors within the ancestral hall, making the ancestral hall an official communication channel between the living and the dead.

The tea lighting ceremony, "Dim Deng" is phonetically similar to the Cantonese phrase "adding a boy" to the family, which makes the ritual symbolic of strengthening the clan. During the ritual, the superintendent of the ancestral hall would gather the names of newborn boys from each village, write them into the ancestral book, and officially join them into the family tree. Tea lights would be placed in front of the altar, each would represent a boy.

Dim Deng ritual at Sam Tung Uk Village (Hakkah)

Dim Dang ritual at Tang Ancestral Hall in Ha Tsuen (Punti)

Provocations

Catholic Suzuka Church / Alphaville Architects

Churches

As the younger generation of Cantonese people grew up overseas, they have lost the cultural touch with the traditional culture. Without the physical presence of their ancestral hall, the new generation could not participate in their cultural rituals. Unlike churches, the ancestral hall does not worship the universal deity, and the fragmentation of the clans caused initial difficulties in constructing an architecture to serve such a purpose. Without a unifying architecture in the community, young Cantonese overseas face an identity crisis as they lose touch with their roots.

Through the recent event of generational migration of Cantonese people, the young Cantonese have come to realize the importance of cultural unity. Observing examples from other immigrant groups, they see that a place of worship could unite all people of Cantonese descent. Therefore, the ancestral hall they have left behind could become a potential solution. Multiple factors are causing the decline of interest in traditional ancestral worship rituals. Other than the missing architectural establishments to practice these rituals, Cantonese culture had also evolved with many outside influences. The practice of ancestor worship could only be preserved if the architecture representing it took on a new approach to engagement. The new ancestral hall should accept and

incorporate modern and Western influences while keeping the fundamental essence of a mass timber structure. It should be a place more than just an occasional ritual. It should take on a wider range of services from weddings to funerals. A new ancestral hall could have a similar function as a Western church, where regular gatherings could be hosted. As a traditional ancestral hall is meant to balance the relationship between clan members, the new hall would balance the relationship between the clans in the same region. Multiple alters could store information there and connect back to their home hall digitally. Different clans of the Cantonese diaspora could meet and gather to break bread and commemorate their ancestors under the same roof.

Building a universal ancestral hall overseas would not only bring unity within the community but also renew interest in traditional culture. It will create, convey, and preserve a culture, as architecture should.

Church of the Light

Tadao Ando Architect & Associates

The Chamber Church BUZZ/ Büro Ziyu Zhuang

Horizontal Perspective

The Kangxi Emperor's Southern Inspection Tour, Scroll Three: Ji'nan to Mount Tai/ Wang Hui

Neviges Mariendom / Gottfried Böhm

Neviges Mariendom / Gottfried Böhm

New Academy of Art in Hangzhou/ Wang Shu

New Academy of Art in Hangzhou/ Wang Shu

Prostho Museum and Research Center/ Kengo Kuma

Under Roof

Martyr Shrine / Lestudioarchitects

Martyr Shrine / Lestudioarchitects

Wa Shan Guesthouse/ Wang Shu

Wa Shan Guesthouse/ Wang Shu

Project

Study Model_ Traditional Ancestral Hall

Study Model_ Traditional Ancestral Hall

Study Model_ Mountain Range

Form

Finding

Study Model_ Traditional Ancestral Hall

+ CEILING

Initial Sketch Study

Secondary Sketch Study

Final Sketch Study

Framing Options

Modern Triangular Steel Bracing

Traditional Chinese Timber Bracing

The beauty of mass timber structure

An Image Caption

UPPER FLOOR PLAN

LOWER FLOOR PLAN

Section_A

Section_A

UPPER FLOOR PLAN

LOWER FLOOR PLAN

Section_B

Section_B

Exploded Timber Joint Diagram

Roof Plan Oblique

CHUNK_3

CHUNK_4

CHUNK_1

CHUNK_2

CHUNK_4

CHUNK_3

Credits

Thesis Advisor: Anna Neimark

HT Advisor: Erik Ghenoiu

Summer of 2019 - in front of my own Ancestral Hall

Ancestral hall is such an important part of Chinese culture, particularly in the Cantonese-speaking region. Yet, it is facing the harshest challenge of urban redevelopment. With waves and waves of decedents moving away from Hong Kong due to political unrest, more ancestral halls would face a decline and fail to upkeep shortly. It is important to carry on the lineage through ancestral halls, but it would be hard to carry on the history when the people are displaced. Many different suggestions have been made recently on how to preserve such practice, either

bringing the practice online, or rebuilding the actual architecture overseas to ethnoburbs such as Richmond BC, or San Gabriel CA. The method of preservation will continue to be a debate, but the conversation has already started with its crises of preservation. The architectural merit of these ancestral halls is immensely valuable to our built environment, and along with it, is also the self-identity of millions of Hong Kongers and overseas Cantonese people; therefore, regardless of the method of preservation, these ancestral halls must be preserved for years to come.