GRADUATE THESIS ‘24

Southern California Institute of Architecture

FIRM - PRESSS

Los Angeles

Southern California Institute of Architecture

FIRM - PRESSS

Los Angeles

Jack Belter

Jack Belter

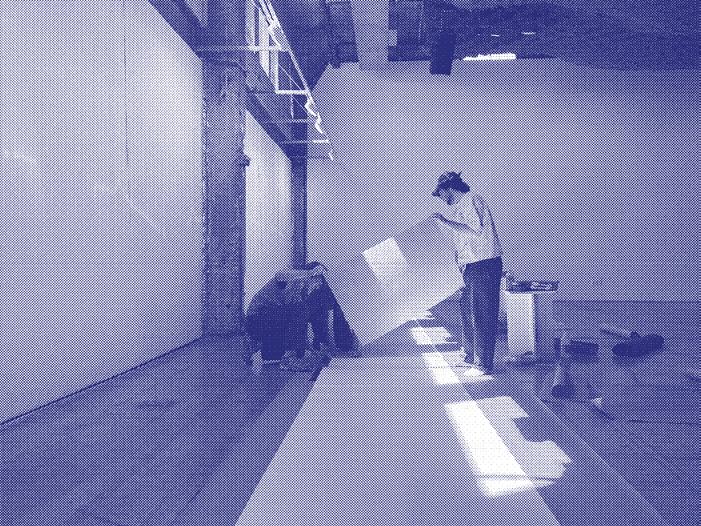

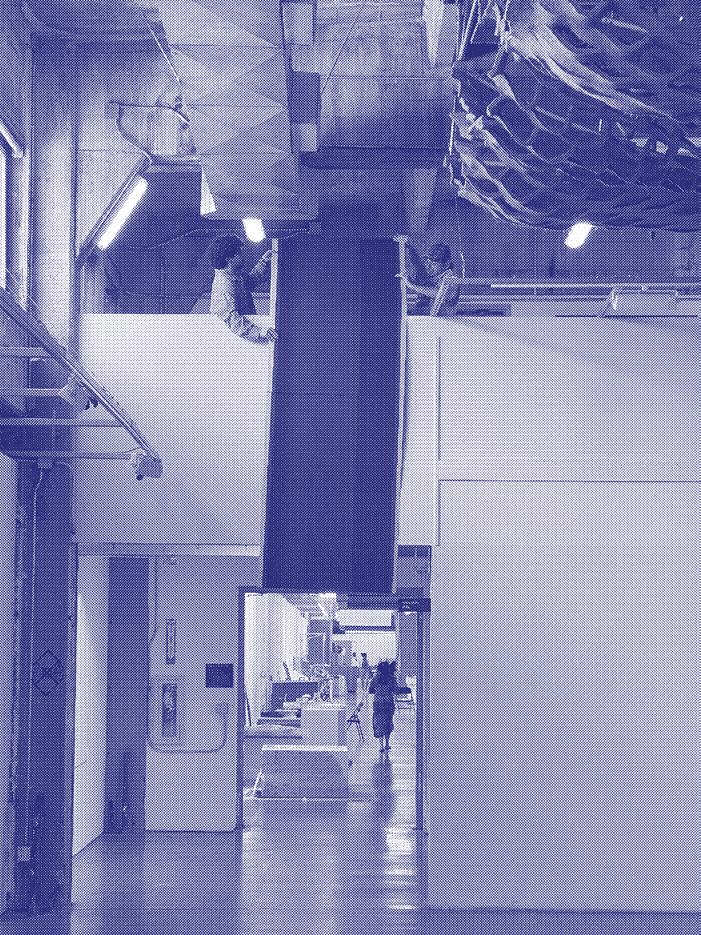

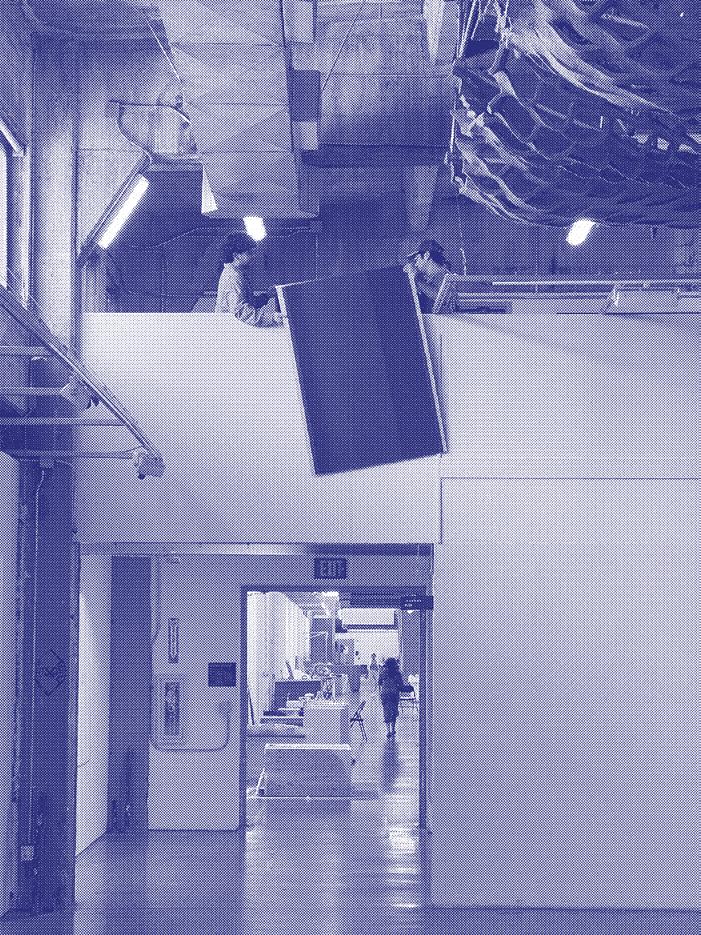

The following pages catalogs the thesis project Building Books presented during the 2024 SCI-Arc Graduate Thesis. Included are essay’s on the project, a catalog of the 6 books curated for its showing, and a collection of e-mails, transactions, and process photographs documenting the people and material involved within it. Along with the content cataloged inside this book, an accompanying presentation book of the same title was made as an instrument of oration during its presentation.

While at SCI-Arc I’ve continually found ways to insert printed matter into my own studio projects. Whether it be imaginary museum programs, material catalogs, or instruction manuals, I found that the format of books and other printed matter allow projects to exist beyond their traditional architectural representation. It was a way of inserting my own project into my education, and exploring the ways that printed matter inserts itself into architectural discourse and practice.

When thesis began, I knew a large component of my project would surround the printed page. To me, it was an opportunity to question one of the few other things that architects interest themselves in. It was Mark Lee in his Gropius Soundings Lecture that said his two favorite things in the world were “building and books” which I think was emblematic of the discipline of architecture’s predilection toward books.

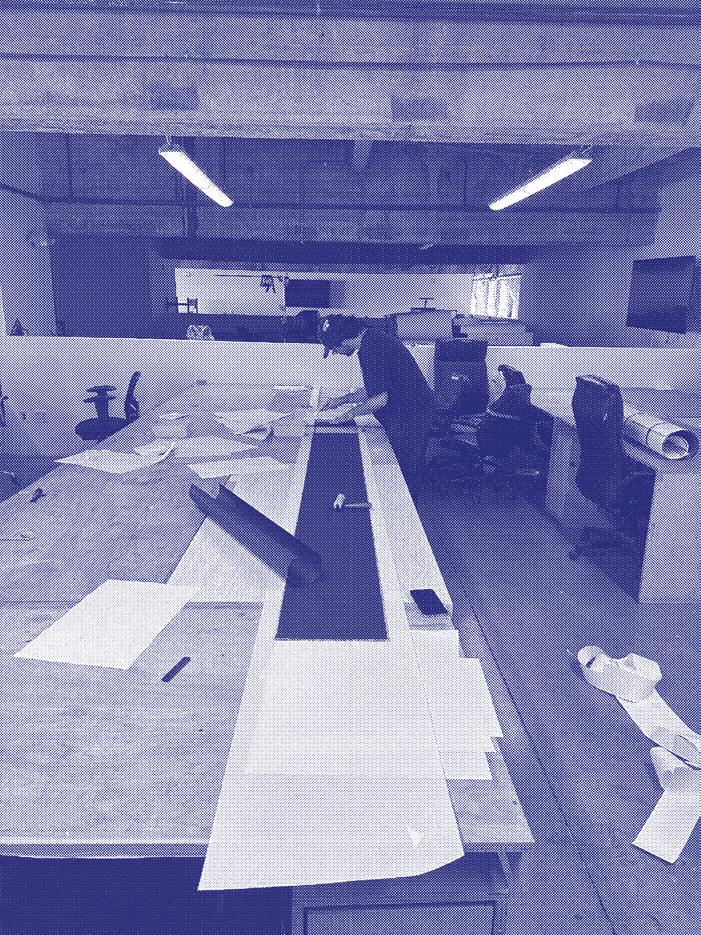

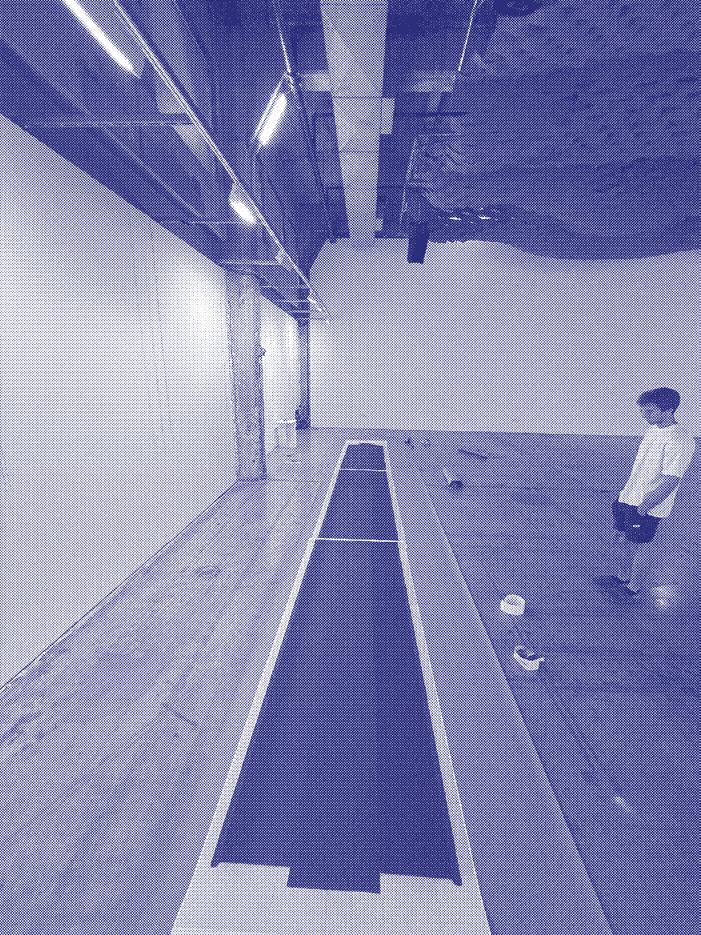

The project began with intuition and medium. I forced myself to engage with books in novel ways, using it as a way of honing technique. As the project developed however, I had to continually engage with the communities and production processes associated within it. The production of books takes much more than one set of hands. It requires experts on all the particularities. The intersection between people, produc-

tion, and discipline is what I find interesting within between books and architecture. It is where these two disciplines begin to conflate, and where the thesis exists.

Building Books is a thesis on many things. It is a project on production, and how we engage with the people surrounding a discipline. It is also about narrative; how books can become a vehicle for telling stories on architecture. Or perhaps it could be read as a reflection on how architects work and how we appropriate, copy and remix the work around us.

Jack Belter

Architecture and printed matter have historically tied themselves to each other, where the proliferation of architecture as a discipline is majoritavely due to the advancements of print technology. It was with the printing of Alberti’s De Re Aedifactoria that initiated the belief that architecture was a medium to be written about, intellectualized, and discussed among well-to-do parties. Books became a vehicle for the dematerialization of architecture, and with that allowed the practice of architecture to reach far beyond its built environment.

And while one might consider a mutuality between these two disciplines, there has been a tension between them since their ties to one another. Victor Hugo’s famous quote “This will kill that” presented that books were the end to architecture’s predominance as a container for human knowledge. While it’s clear this belief does not uphold due to the reliance on books and printed matter that architecture has had, it reveals that “architecture did not derive from the need for shelter… Rather, architecture arose from the same impulse that gave birth to writing.”1 The relationship between books and architecture take form in many ways from Labrouste’s Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève to architecture as written word. The publications of Venturi, Scott Brown, Koolhaas, or Rossi serve as examples of the building in written form where the ideas of architecture could materialize through printed matter.

This narrative ignores glaringly large components of both disciplines. That both books and architecture engage within a larger network of practitioners, materials, and conventions that allow for their production. Books themselves, just like architecture, are material. They are meant to be touched, to be occupied, and their forms and concepts allow us to engage with

them beyond their content. Take Dlia Golosa by El Lissitzky, a book “meant to be read out loud, the pages an instrument to project the author’s intended meaning into the reader’s space.”2 Here it is the concept of the book itself that expands itself into the built environment. “The volume’s physical qualities were not intended to guide the eyes or hands but were conceived directly for the voice. The poem, when read aloud, became a shared social experience.” The construction of books then can be looked through the lens of the architect where the book’s construction, convention, or material are opportunities to tie itself to the built environment. In doing so the stories of both architecture and book production interlink.

The relationship between books and architecture is not unique. Architecture’s relationship to many other disciplines share this; where the intersection of mediums generates something else. Thomas Ruff’s collaborations with Herzog and de Meuron show the agency of the artist in relation to architecture. His use of photography to edit and fabricate realities within Herzog and de Meuron’s work is a method that is not in pursuit in the re-representation of architecture. Instead, it is to exploit what photography can do3; that photography is a point of translation from building to printed image that produces something entirely new.

John Nichols is another figure tied to the history of architecture’s production. His work as a printmaker in aid to architect’s in the 1980s and 1990s aided in the elevation of the architectural drawing’s status as a product of art itself. Sylvia Lavin describes Nichols relationship to architecture as “not only defined in relation to medium or discipline but also as the intersection between people and production.”4 Unlike Ruff,

Nichols is not a figure of note to the same degree for his work. Instead he is considered very much a technician in his relation to architecture. That however, does not diminish his own work, nor does it affect his ability to influence architecture. Ultimately, it is architecture’s intersection with these mediums that allow for a closer reading of them. Not as technicians or artists, but as architects who embody many roles and work alongside their production.

1. Robin Middleton, The Beaux-Arts and Nineteenth-Century French Architecture (London: Thames And Hudson, 1984).

2. André Tavares, The Anatomy of the Architectural Book (Montreal: Canadian Centre For Architecture ; Zurich, 2016).

3. Jacques Herzog, “Jacques Herzog - New Works by Herzog and de Meuron,” Youtube (AA School of Architecture, October 24, 1999), https://youtu.be/F7UK6ns2fK4?feature=shared&t=964.

4. Sylvia Lavin, Architecture Itself and Other Postmodernist Myths (Montreal: Canadian Centre for Architecture , 2018).

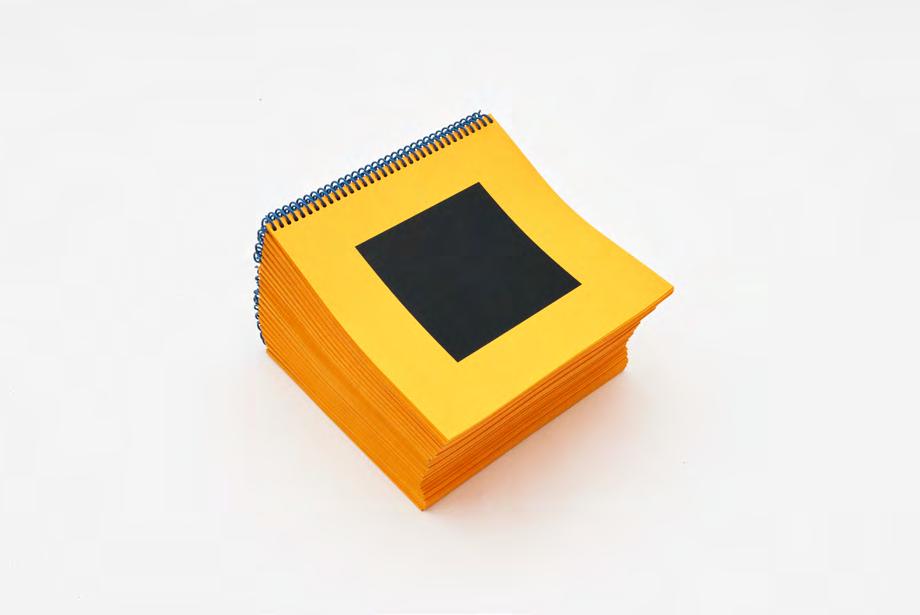

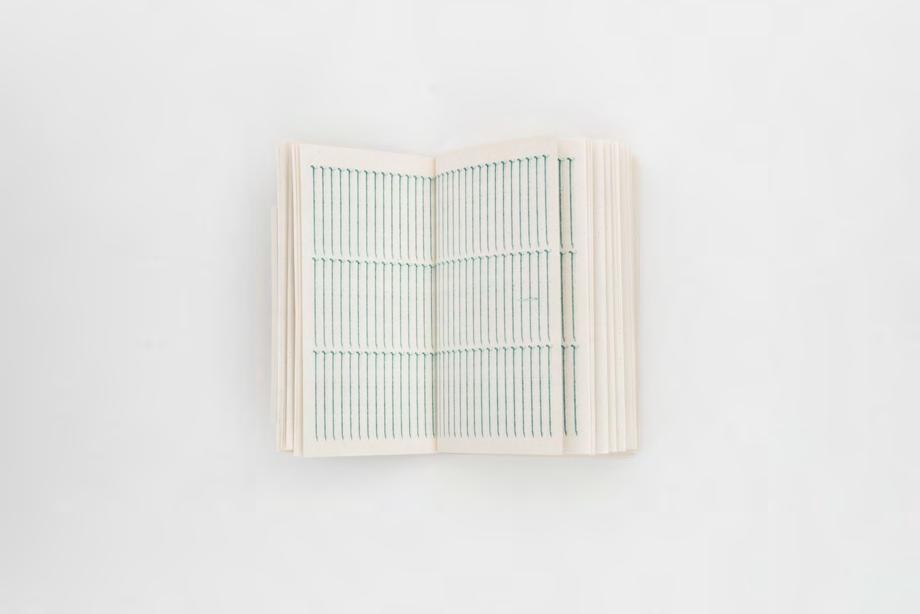

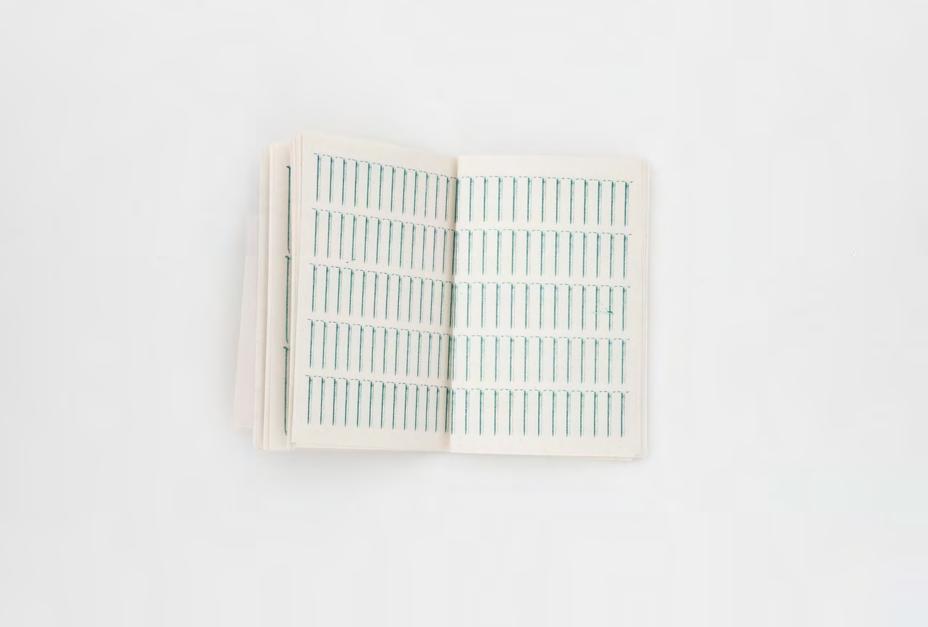

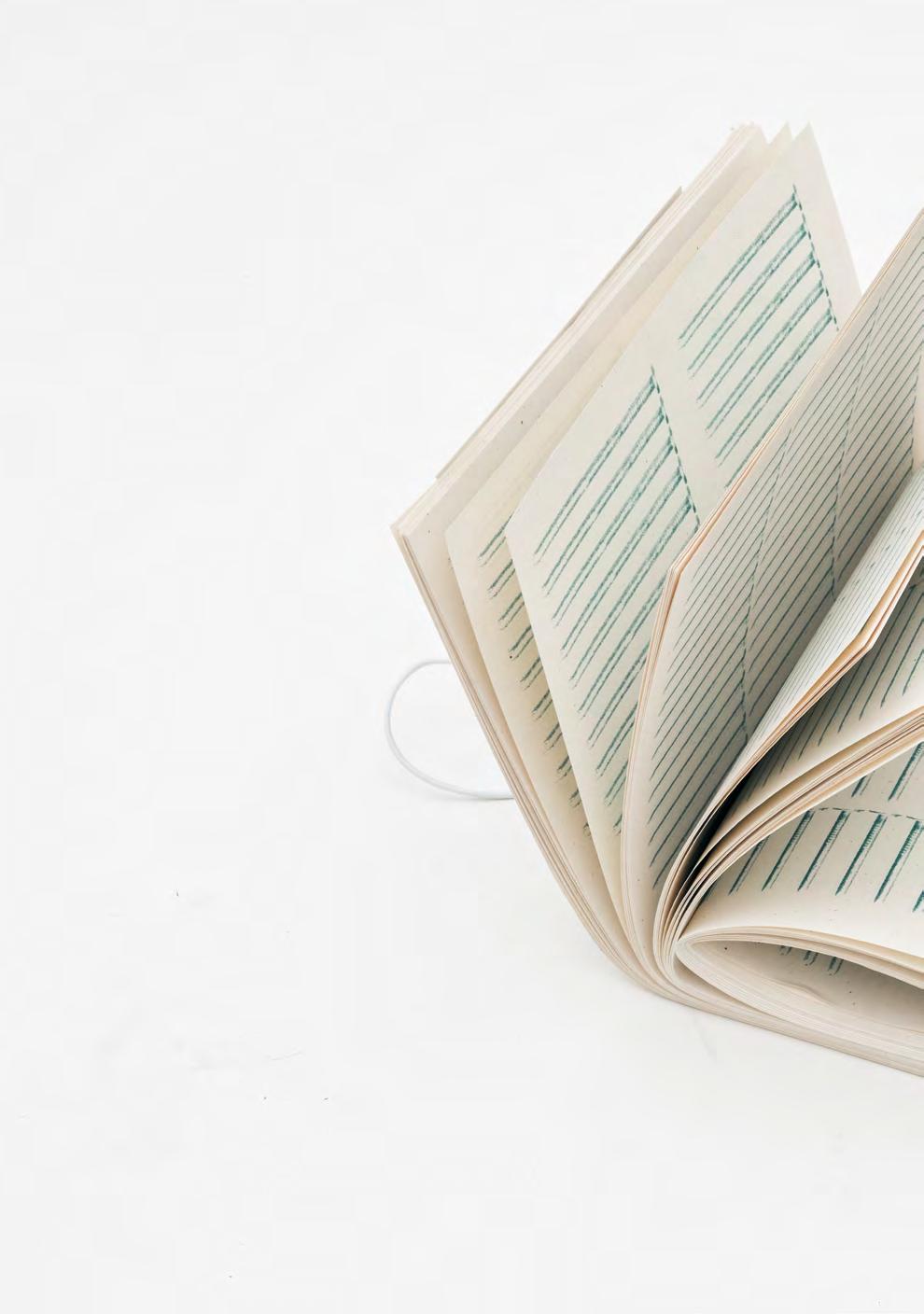

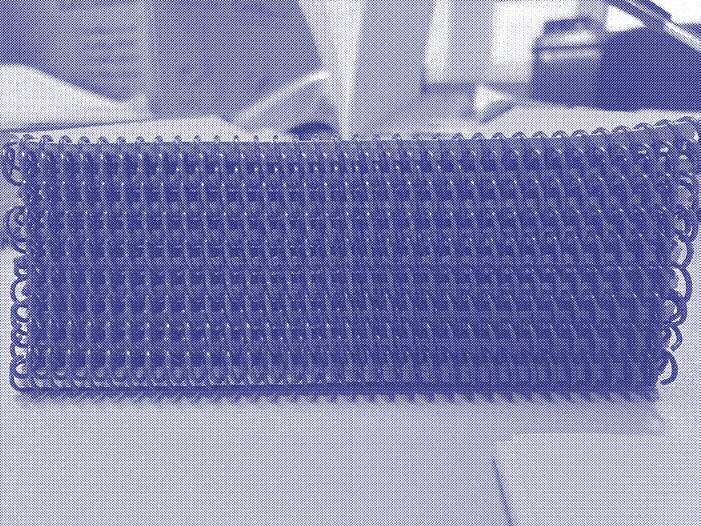

A book containg 500 serialized section of Aldo Rossi’s Monument for the Resistance in Cuneo. The sections are printed at 1:100, and the thickness of book is equal to the buildings thickness at that scale. The book is binded using a series of stitched spiral coil bindings.

for the Resistance in Cuneo 4 x 4 x 5 in

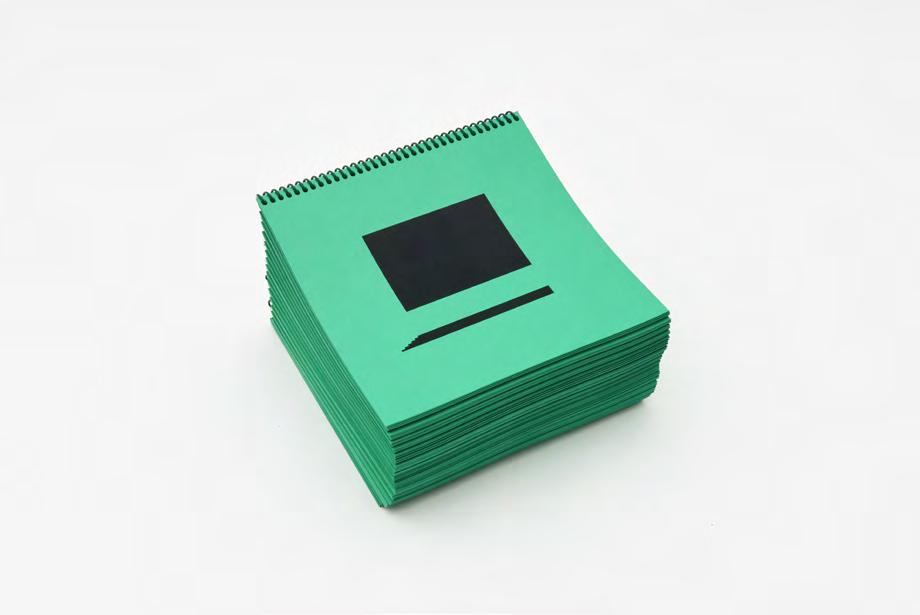

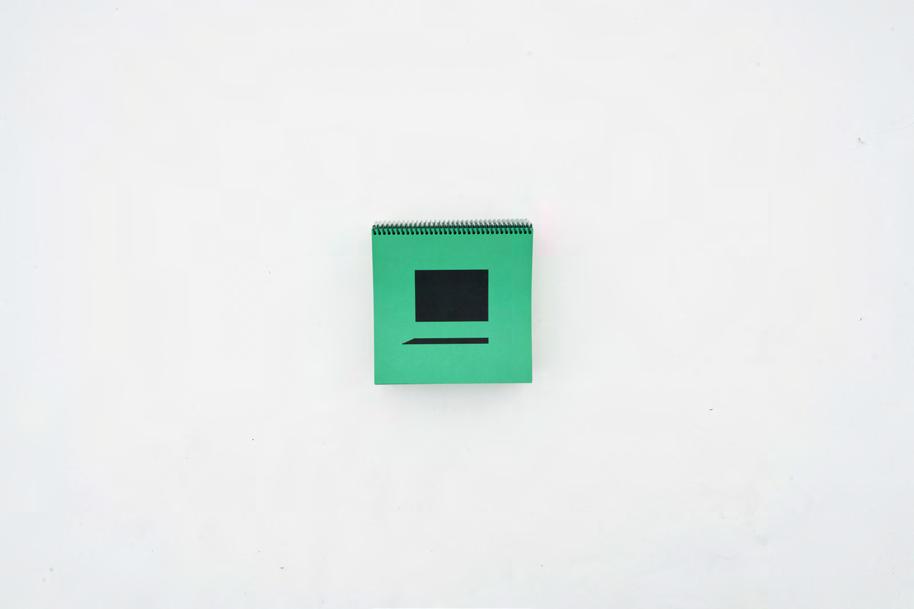

A book containg 400 serialized section of Aldo Rossi’s Monumental Fountain in Milan. The sections are printed at 1:100, and the thickness of book is equal to the buildings thickness at that scale. The book is binded using a series of stitched spiral coil bindings.

x 8.5 x 4 in

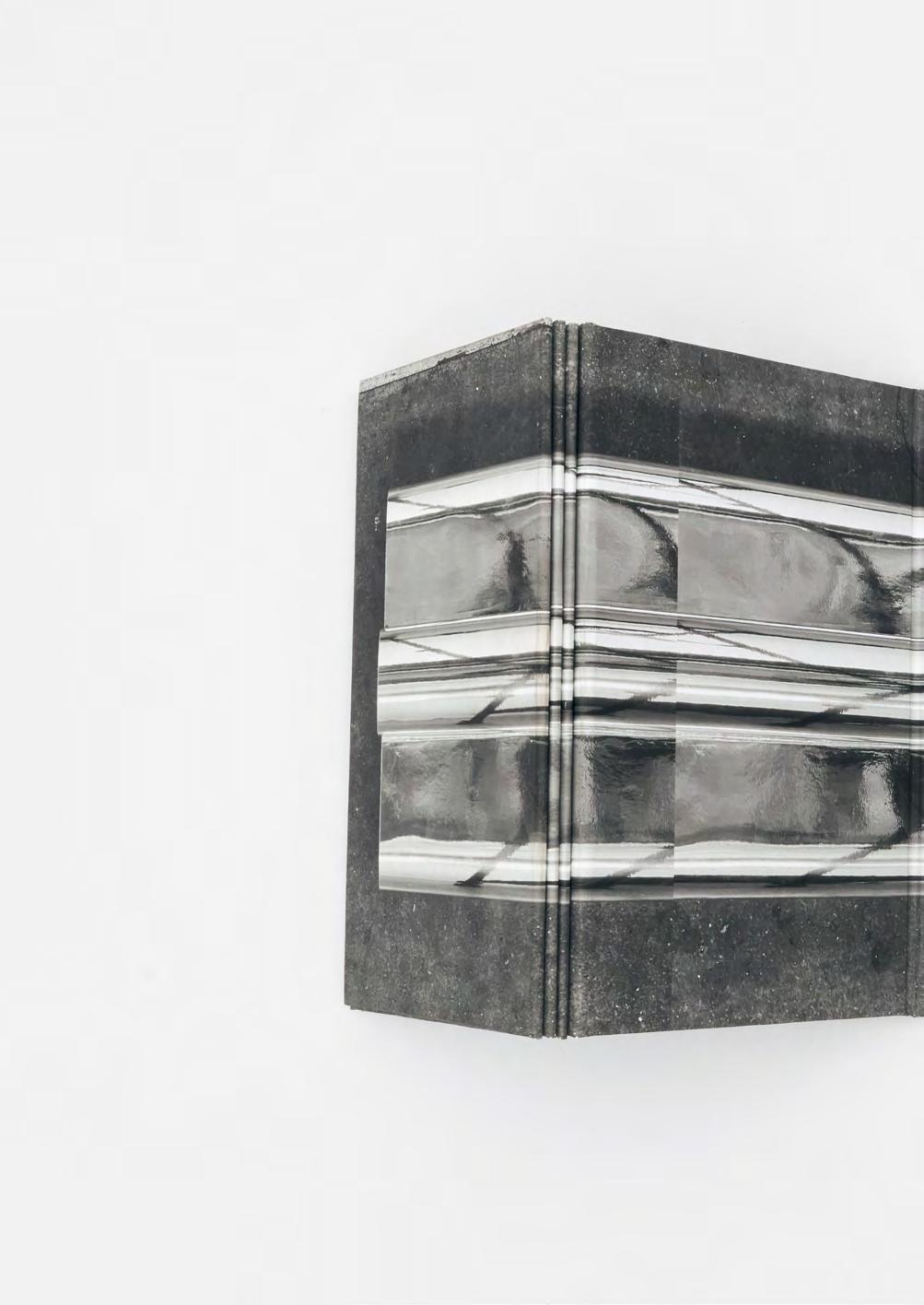

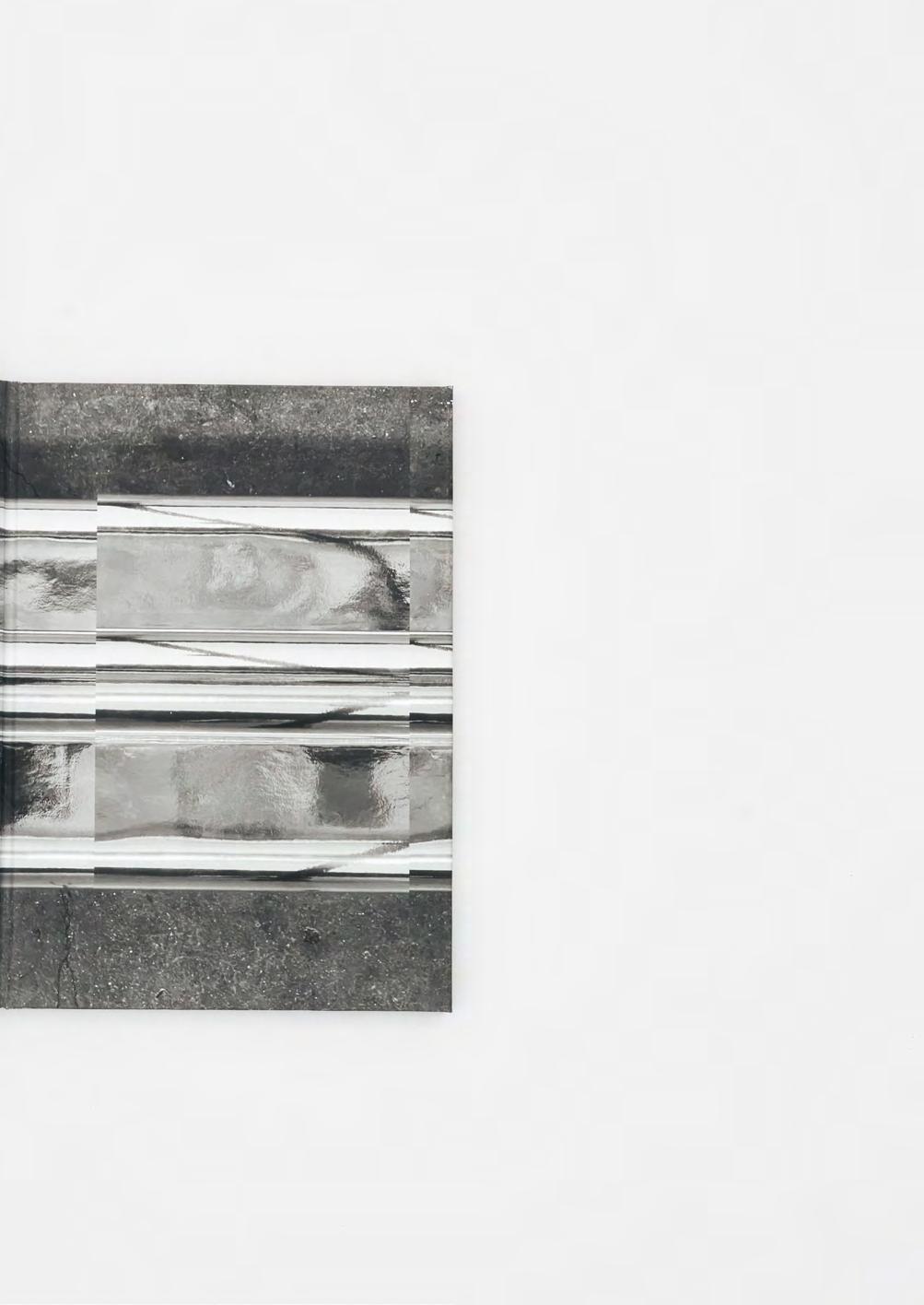

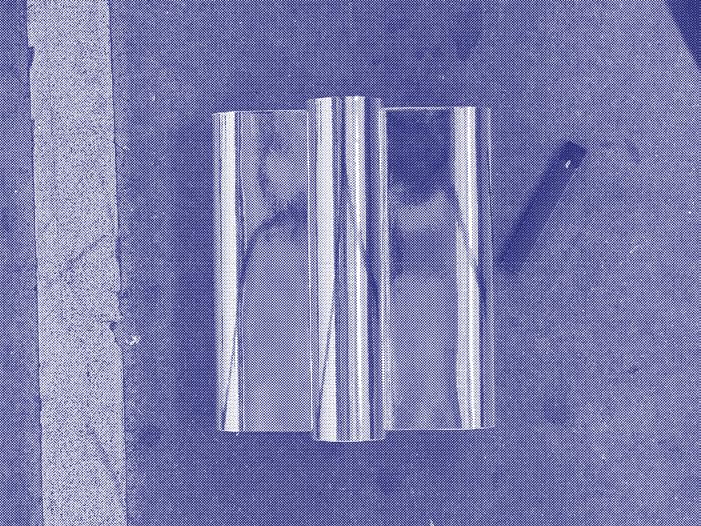

A book containing a 1:1 stitched photograph of the 3 meter column found in Mies van der Rohe’s Villa Tugendhat. The book is binded using a leporello binding, where each page is constructed using one sheet of book-board cut to DIN A4 paper size and cased in the printed photograph.

Tugendhat Column

210 x 297 x 39 mm

A book containing a 1:1 stitched photograph of the 15 column found in Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House. The book is binded using a leporello binding, where each page is constructed using one sheet of book-board cut to letter paper size and cased in the printed photograph.

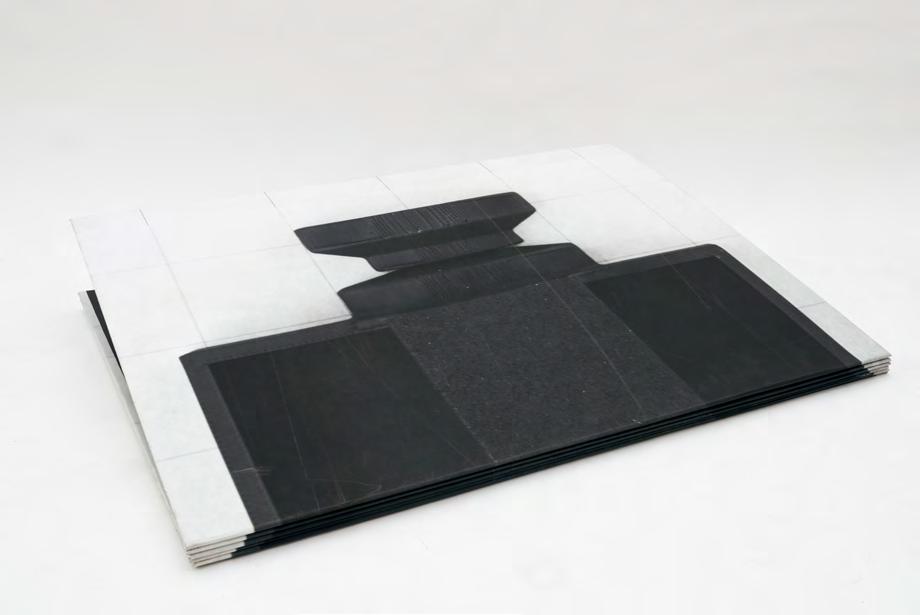

A book containing a 1:1 stitched photograph of the 8.5 meter column found in Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie. The book is binded using a leporello binding, where each page is constructed using one sheet of book-board cut to DIN B1 paper size and cased in the printed photograph.

Neue Nationalgalerie Column

707 x 1000 x 34 mm

A book containing a collection of 16,910 nails used to construct the Lieb House by Venturi Scott Brown & Associates. The 84 pages are loosely binded and folded into a single signature with its creep untrimmed.

16,910 Nails : Lieb House

5.5 x 8.5 x 2 in

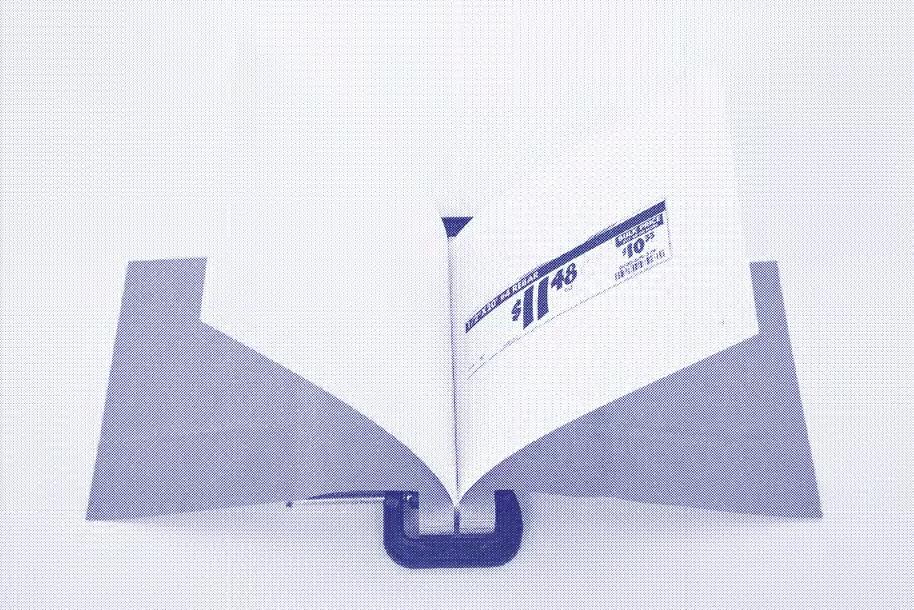

The clamp bound book contains a selection of Home Depot price tags of building materials found from the Frank Gehry’s Arnoldi Triplex in Venice. Built and inspired by artist friends of Gehry, the triplex was made with intentionally cheap and sometimes unconventional building materials. Over time the triplex’s materials have decayed requiring a constant maintenance of the houses. Most recently the operable windows of the triplex were replaced with inoperable ones due to the beach air of Venice hindering their operability. The pages of the book are held in place by two pieces of plywood viced together. The binding restricts the book from fully opening up and laying flat.

Frank Gehry, Arnoldi Triplex , 1981

Seven newspaper photographs of fathers and sons are displayed on A4 newsprint spreads. The photographs, inspired by a Thomas Ruff newspaper photograph of a father and son etched onto the facade of the Eberswalde Library, mirror the format of the working documents utilized by the firm at the time. The newsprint pages were progressively exposed to the sun, aging and yellowing the non-archival paper. As part of the environmental requirements for the Eberswalde Library was the need to protect the books and documents inside safe from the harmful UV rays. The book materializes and documents this effect by showing the difference in exposure of the paper.

Herzog & de Meuron, Eberswalde Library, 1997

The spiral bound book document’s the various bond and colored patterns featured on the facade of the ISI Headquarters built by Venturi Scott Brown. The clear acetate sheet features a coded notation of each of the porcelain tiles, while the page behind utilizes the specific pantone colors used for them. The facade is a reflection of the information management held inside, showing how VSBA addressed a shift in information and data management, by reflecting it’s indexcial and coded nature on the exterior. The book’s represents this information in the coded language it represents by using numerical and indexical notation as a form of analysis and representation.

Spanning a four mile long strip of Manhattan, a subsection of the continuous monument reveals a sequence of imagery that navigates through the imagined landscape of the project. Each fold and page turn mirror the rigid expansion depicted in the original imagery of the project. The accordion-bound book serves as a tangible representation of an abstract architectural proposal, and acts as a continuation of the projects relationship between the natural and artificial.

Superstudio, The Continuous Monument, 1970

Matching the exact dimensions of the 1986 edition of Toward An Architecture, this paperback copy has digitized each page of the book, representing them as QR Codes instead. The QR code, invented in 1994 by the automotive company Desno Wave, was originally a a means to facilitate the mass production of automobile parts. The compression of information aided by the QR code follows our contemporary methods of interacting with information. An entire book’s information no longer needs to fit within the confines of it’s pages and can now be contained within coded image.

The 1986 edition of Toward An Architecture (at the time mis-titled as Toward A New Architecture) published by Dover presents Le Corbusier’s seminal manifesto on paperback. It’s contents are formatted as symmetrical page spreads intended to create a dialogue between page spreads. In practice the book is constructs a series of diptychs, drawing relationships of things ranging from architecture to automobiles.

Le Corbusier, Towards An Architecture, 1923

A collection of scanned screenshots off an iPhone contain Hito Steyrel’s e-flux journal essay “In Defense of the Poor Image”. The interface of the smart phone formats media to be consumed in a particular way: click, scroll, scroll, scroll. The verticality of the screen removes the versatilityof the spread. Steyrel’s essay, a born-digital object, was primarily circulated through online channels. It’s text and images are sequenced, and formatted to the digital device. “In Defense of the Poor Image” questions the traditional media channels, specifically those that are controlled by large, corporatized institutions. Bootlegs, imperfect replicas,and other grey channel forms of distribution trade resolution for velocity; marking more accessible forms of media consumption.

Steyrel, In Defense of the Poor Image, 2018

The matchbook became widely popular in the late 19th century as a vehicle for promotion and advertisement. Likened to other easily distributable printed media, such as postcards, the matchbook creates an immediate relationship between printed image and public engagement. Printed on its paperboard cover is a chromolithograph of the exterior of the Crystal Palace as done by Matthew Digby Wyatt. Enclosed inside are ten matches in addition to twelve of Wyatt’s chromolithographs. The printmaking technique of chromolithography, as utilized in Dickinson’s Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851, replicate the Crystal Palace’s vibrant internal environment. Color plays not only an important role in the representation of the Crystal Palace, but also its built environment, creating an optical relationship between it’s structure and setting. Wyatt’s prints translate the techniques of polychromy within the building into the realm of printmaking and books; now serving as key records of the now burned down building.

Paxton, Crystal Palace, 1851

An excerpt from the thesis prep zine ‘for what?’

From the 15th century onward, the use of print media has been instrumental in the development and dissemination of architectural information. Bob Somol in his lecture “See What I’m Saying” points to Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau’s book S,M,L,XL as an end of ‘paper architecture’.1 No longer are books the main priori of polemical engagement within the field, instead the book became the building. The need and basis for books as some catapult of architectural discourse was superseded by the work itself; merging the two into one. This argument is built on Jacques Herzog’s quote “No architect has ever written a text which has survived more than one generation. What survives, what influences architecture, what makes architecture is the work.”

Counter to Jacques provocation, one might look at the history of architectural books as a way in which Architects didn’t just display their work, but as also an object that became the work.Le Corbusier and Koolhaasare both examples of architects who have worked primarily through print in these forms. Given the possible end of ‘paper architecture’ as well as a digital turn, giving speed and velocity to our own information channels, it is important that we re-assess the book and its purpose within Architecture.

Architecture’s predilection of print media stems from its cultural roots within the discipline. At its time, it was Architecture’s best vehicle for disseminating information. Shifts in technology have transformed our informational vehicle from a model-t to a six-cylinder twin-tubro super car. The velocity in which we consume and dismiss information has wildly changed. No longer are books the fastest, nor most inclusive way of exchanging ideas. In fact, due to the nature of books’

small print-runs and gate kept points of entry, the book has become a pillar to which anyone wanting to engage within architecture encounters. Hito Steyerel describes this phenomenon in regards to image circulation noting “perhaps one has to redefine the value of the image, or, more precisely, to create a new perspective for it.”2

Apart from resolution and exchange value, one might imagine another form of value defined by velocity, intensity, and spread.”2 Given the technological shift and expansion in our own means of production, the ease of entry into book and printmaking is higher than ever before. Maybe then we should also re-assess the qualities and reasons why we as architects use books and other printed materials. Given that all media is better, and faster spread through digital channels, the book must become something more than a vehicle for communicating information. Treating the book as an object, one with material that simultaneously addresses its creation in a digital-skewed culture, and celebrates its physicality. “Creating a book anew in and for the digital age, such works renew a conventional book form(the codex) by harking back to ancient techniques of book construction and recreate the intimacy of reading and sharing a book... Reverting to old traditions of bookmaking to provoke new orientations toward the object of reading, and as such, inviting reflection on reading as an embodied cognitive, and social practice”3

Plate may be right - maybe we must hearken back to the roots of technique and representation to re instill value into print media, or maybe there is another way.

1. Grau, Urtzi, and Cristina Goberna. “What Kinds of Copies?” Log, no. 31 (2014): 139–42. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43630899.

2. Steyerl, Hito. “In Defense of the Poor Image.” E-Flux Journal, no. 10 (November 2009). https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/indefense-of-the-poorimage/

3. Wadhera, Priya. 2016. Original Copies in Georges Perec and Andy Warhol. Boston: BRILL. Accessed April 8, 2024. ProQuest Ebook Central.

4. Hillel Schwartz. 2014. The Culture of the Copy : Striking Likenesses, Unreasonable Facsimiles. New York: Zone Books.

5. Krauss, Rosalind. “Photography’s Discursive Spaces: Landscape/ View.” Art Journal 42, no. 4 (1982): 311–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/776691.

An excerpt from the thesis prep zine ‘RE:Copy’

Architecture interests itself in the pursuit of originality. Without necessarily being uninspired or non-referential, Architects as well as other creative practitioners seek it in order to generate a sense of uniqueness. Hidden in plain sight is the simple truth that “Architects, copy!”1. The copy as a tool utilized by architects seeks to readdress our notions of distribution, authorship, and authenticity.

The copy is easily distributable. Beginning with the advent of the Xerox 914 copy machine that at the turn of the knob could produce hundreds of copies, the velocity in which text and images could be reproduced and distributed shifted. With this and other digital reproduction technology, images, film, and other media began to move at an unprecedented motion, shifting the word copy(n) to the active copy(v). Hito Steyerl presents this phenomenon as the poor image, “a ghost of an image, a preview, a thumbnail, an errant idea, an itinerant image distributed for free, squeezed through slow digital connections, compressed, reproduced, ripped, remixed, as well as copied and pasted into other channels of distribution.”2 It’s distribution becomes a new vehicle to which copies begin to act against capitalistic channels of broadcast.

The copy is non-authorial. It appropriates the original and degrades the history that exists before it, and replaces it anew. “Pierre Menard, author of the ‘Quixote’” by Jorge Luis Borges stories a man who strives to recreate “Don Quixote” line for line. In doing so, the original is reappropriated, and new meaning is inserted into the translation bore just off context alone. Georges Perec’s work “Un cabinet d’amateur” questions authorship in another way. A cabinet d’amateur is often a painting of a collection of artwork, in which many paintings

and Lithographic Reproduction)

are copied in order to produce it. The short novel is a literary translation of a collection of artwork, acting as a re-representation of something described to be real.3 Authorship in both of these cases places it not within the original but the entity who is copying.

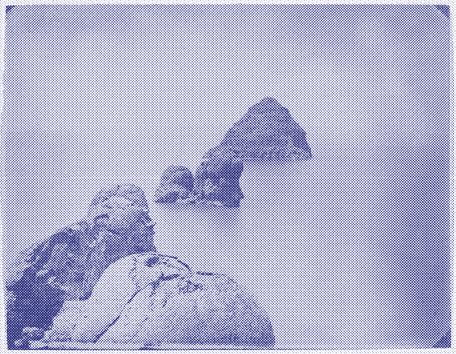

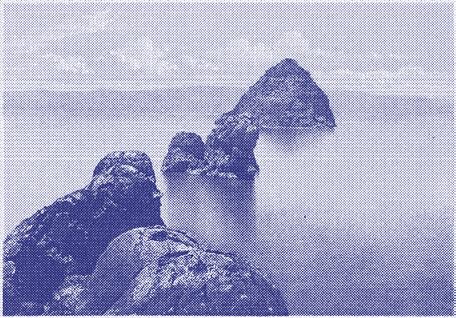

The copy positions itself as a false truth. “We use copies to certify originals, originals to certify copies”4. Copying is pedestrian. Its interest is not in pure authenticity; rather, transforming originality into accessibility, and reconstructing our understandings of the original. Timothy O’Sullivan’s photograph titled Tufa Domes, Pyramid Lake, Nevada, and its lithographic reproduction present how the copy can reproduce a false truth. Rosalind Krauss argues for the “mysterious, silent beauty” of the original, and that the copy is “an object of insistent visual banality”5. The effect of the copy, imperfect in its reproduction of the original, produces a new reality in which O’Sullivan’s work exists. It holds completely different optical qualities in comparison to the original, trading its originality for velocity. The lithographic copy originally published in Clarence King’s 1878 publication Systematic Geology, exists within a circulation and distribution platform that advantages itself in relation to the original. To those that have never had access to the original, this copy becomes truth. The copy brings on a question then: what is the real thing? The copy “is no longer about the real thing—the originary original. Instead, it is about its own real conditions of existence: about swarm circulation, digital dispersion, fractured and flexible temporalities. It is about defiance and appropriation just as it is about conformism and exploitation.”2

1. Grau, Urtzi, and Cristina Goberna. “What Kinds of Copies?” Log, no. 31 (2014): 139–42. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43630899.

2. Steyerl, Hito. “In Defense of the Poor Image.” E-Flux Journal, no. 10 (November 2009). https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/indefense-of-the-poorimage/

3. Wadhera, Priya. 2016. Original Copies in Georges Perec and Andy Warhol. Boston: BRILL. Accessed April 8, 2024. ProQuest Ebook Central.

4. Hillel Schwartz. 2014. The Culture of the Copy : Striking Likenesses, Unreasonable Facsimiles. New York: Zone Books.

5. Krauss, Rosalind. “Photography’s Discursive Spaces: Landscape/ View.” Art Journal 42, no. 4 (1982): 311–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/776691.

Building Books bore from the many conversations I’ve had with friends, and instructors at SCI-Arc, where before even entering thesis, I was able to do work that would lead to its fruition. In many ways the project became less about the final production of objects and just as much about those conversations. My instructors at SCI-Arc, particularly Matthew Au, Zeina Koreitem, and Devyn Weiser were of great help. Each of them has aided me throughout this project. Matthew was my thesis advisor through the summer, and helped see many of the project’s parts to fruition. As an advisor, he gave me the opportunity to experiment, fail, and find ways to navigate my project without being too prescriptive. Looking back at our initial conversations, it is funny to think where the project began and how it finished. Zeina was my thesis prep advisor during the spring semester. During the semester, she encouraged her students to be in a state of making. I believe that her advice encouraged me during that period to push the project forward through production first, setting the groundwork for the summer semester. Finally, Devyn Weiser has been a great helping hand over the spring and summer semesters. She has always been a wealth of knowledge, and I am always glad to see a message in my inbox with a new reference from her. It was such a pleasure to be surrounded by such intelligent and helpful instructors during my last few semesters at SCI-Arc, and I believe that it contributed immensely to my development and success as a student.

Bookmakers Matt Austin and Kiki Lechuga-Dupont have also been instrumental in the production of this thesis. I took a bookmaking workshop with them over the summer that completely demystified the process to me.I believe it was an inflec-

tion point within the thesis where I felt like I could begin to engage in the production of books in another way. Them and their print studio For the Birds Trapped in Airports have also helped bind and prepare the final glossary and presentation books for the thesis.

I’d like to thank Ben Denzer for his correspondence with me over the summer. It was really nice to connect and hear his advice over the semester. His work is amazing and many of the objects made were very much influenced by his own work.

I’d finally like to thank all of my friends who helped me on the project: Carley, Shaun, Caroline, Aram, Kelly, Ben, and Sev. Their help along with the conversations, bottles of wine, matches of Machi Kuro 2 and table tennis have helped keep my sanity through the semester. I cannot thank any of them enough.