The Ripple Effect of Innovative Wildlife Care

The Ripple Effect of Innovative Wildlife Care

At this one-of-a-kind tasting event, Southern California’s best food, wine, and brews are mixed with wild entertainment and the world’s most fascinating wildlife. Join us for this can’t-miss, all-inclusive evening to savor and sip your way through dedicated party areas around the San Diego Zoo. Raise a glass and take a bite out of conservation at the tastiest event that saves and protects the future for wildlife and the planet we all share. Saturday, September 21, 2024 7:30–10 p.m. at the World-Famous San Diego Zoo

Journey Through Our Conservation Work

Vol. 4 No. 4

To learn more about our collaborative conservation programs, including our wildlife care at the San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park, visit sdzwa.org. July/August 2024

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance safeguards wildlife in eight conservation hubs around the world.

10

Making Waves with the “Water Horse”

Take a deep dive into the unique and semiaquatic world of the San Diego Zoo’s river hippopotamuses and their upgraded habitat.

Features

With help from the San Diego Zoo’s polar bears—and some amazing technology—we are learning a lot about the great ice bear.

20

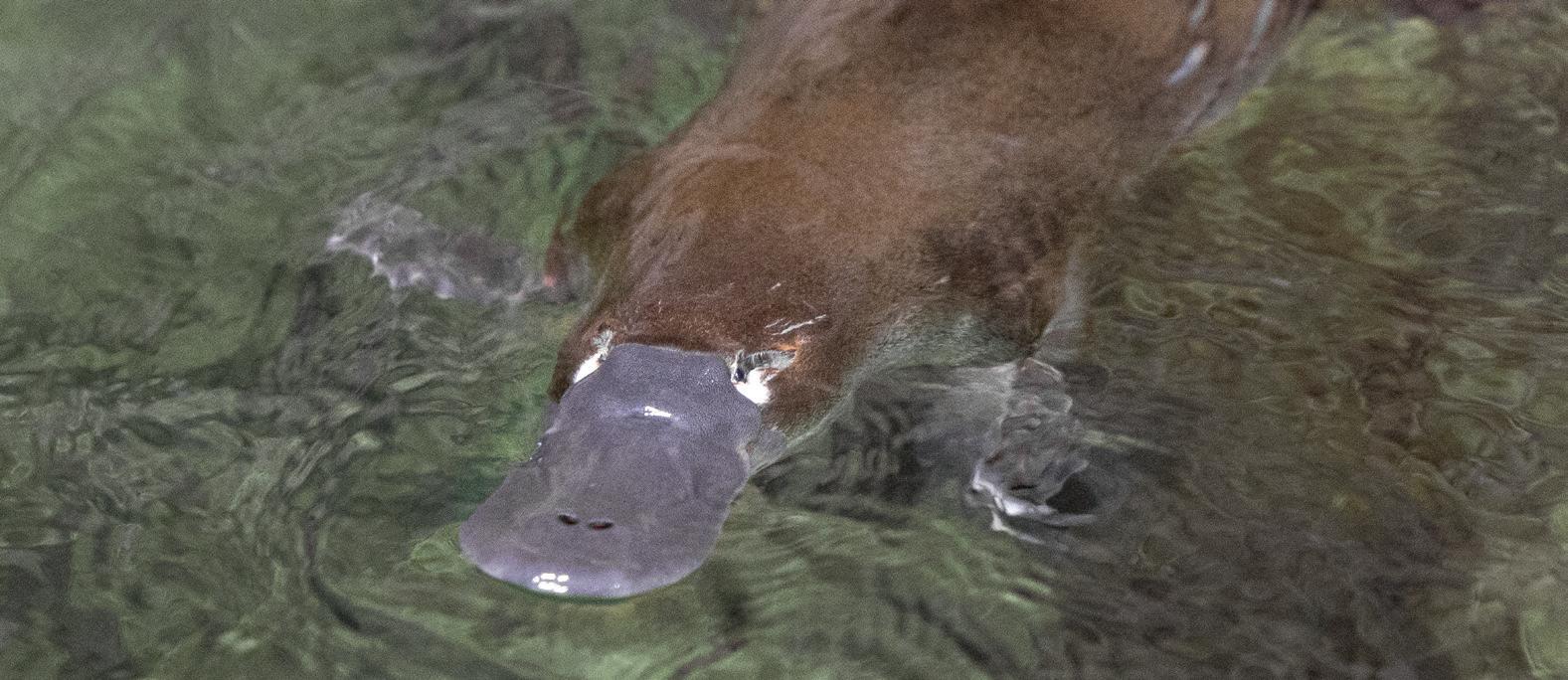

Making a Splash

If it looks like a duck, swims like an otter, and lays eggs, it’s the platypus! Get an in-depth look at this freshwater-loving mammal.

24

Visualize It

When it comes to providing the best possible care to wildlife, it takes a village—of dedicated conservation specialists. Luckily, SDWZA includes hundreds of them, all ready to realize a world where all life thrives.

MANAGING EDITOR Peggy Scott

STAFF WRITERS

Eston Ellis

Elyan Shor, Ph.D.

Alyssa Leicht

Arwen Neski

Ellie McMillan

Sandy McCann

COPY EDITOR Sara Maher

DESIGNERS

Christine Yetman

Kaitlyn Lara

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Ken Bohn

Tammy Spratt

DESIGN AND PRODUCTION

Kim Turner

Lisa Bissi

Jennifer MacEwen

PREPRESS AND PRINTING Quad Graphics

Follow @sandiegozoo & @sdzsafaripark.

Share your #SanDiegoZoo & #SDZSafariPark memories on Twitter & Instagram.

The Zoological Society of San Diego was founded in Octo ber 1916 by Harry M. Wegeforth, M.D., as a private, nonprofit corporation, which does business as San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

The printed San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Journal (ISSN 2767-7680) (Vol. 4, No. 4) is published bimonthly, in January, March, May, July, September, and November. Publisher is San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, located at 2920 Zoo Drive, San Diego, CA 92101-1646. Periodicals postage paid at San Diego, California, USA, and at additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, PO Box 120271, San Diego, CA 92112-0271.

Copyright© 2024 San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. All rights reserved. All column and program titles are trademarks of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

If your mailing address has changed: Please contact the Membership Department; by mail at P.O. Box 120271, San Diego, CA 92112, or by phone at 619-231-0251 or 1-877-3MEMBER.

For information about becoming a member of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, please visit our website at ZooMember.org for a complete list of membership levels, offers, and benefits.

Paid subscriptions to San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Journal are available. Contact Membership Department for subscription information.

There are countless moments at the San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park where our wildlife care specialists elevate conservation. Through their dedication and care of thousands of species of animals and plants, they create new possibilities and hope for wildlife here in San Diego and around the globe. We’re honored to celebrate National Wildlife Care Specialist Week in July and thank our team members— and wildlife experts everywhere—for their enduring commitment to a world where all life thrives.

Wildlife care specialists are collaborators and innovators whose work fuels our efforts to save wildlife worldwide. In this issue, we’ll explore some of the unique ways our team creates dynamic experiences for the world’s most incredible species. Our two leading zoos provide a second chance for wildlife when they need us most, including the three polar bears who were orphaned as cubs, rescued, and have been cared for at the Zoo. In addition to offering a sanctuary and world-class care, this special opportunity offers insights into nature’s mysteries, like how long it takes for a polar bear to grow fur. Such a simple question helps unlock important information about the health of entire populations across the Arctic. And to monitor these apex predators across their vast ecosystem, we’ve drawn inspiration from nature. We collaborated with partners to develop burr-like GPS devices and refine noninvasive tracking, uncovering insights into the complexities of polar bear movement and accelerating conservation efforts for these iconic species worldwide.

Every species is unique, and while some end their day when the sun sets, the activities of others are just beginning. Our teams provide around-the-clock care for species that thrive in darkness to ensure we support their nocturnal life cycles. Through innovative habitats, we also transport guests into an immersive “moonlight” environment, where they fully encounter how nocturnal species, like platypuses, navigate their unique ecosystems after dark. At the Safari Park, we have the honor of being the only zoo outside of Australia to care for platypuses, and our wildlife experts work alongside our Australian partners developing best practices to care for and conserve this elusive species.

All this work here in San Diego and around the world is only possible through your support. Thank you for being a such a special member of our Alliance.

As part of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s commitment to conservation, this magazine is printed on recycled paper that is at least 10% post-consumer waste, chlorine free, and is Forest Stewardship Council ® (FSC ®) certified. FSC ® is not responsible for any calculations on saving resources by choosing this paper.

Onward,

Paul A. Baribault President and Chief Executive Officer

Paul A. Baribault President and Chief Executive Officer

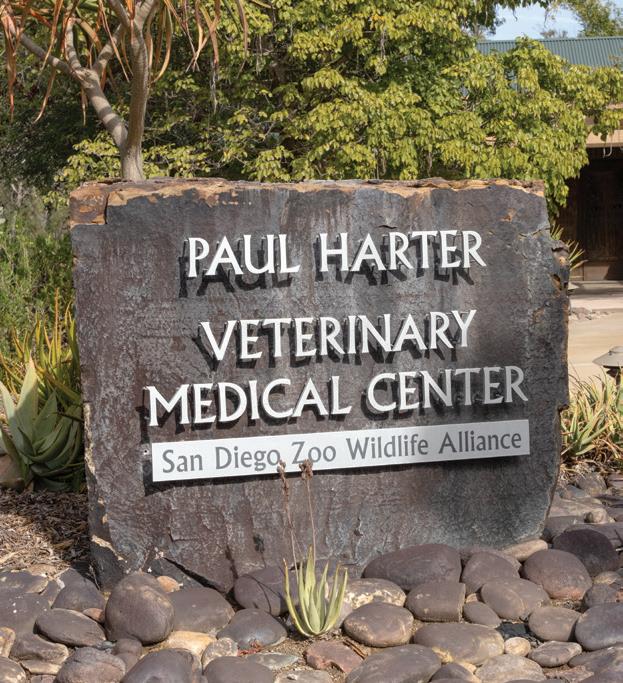

As a global conservation organization, caring for the world’s wildlife is at the heart of everything we do. Be it cells, chicks, or elephants, world-class wildlife care requires training, resources, and experience. Our teams of wildlife health and care specialists are critical to a world where all life thrives.

2

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance includes not one, but two veterinary hospitals that offer world-class wildlife care.

410

1

OFFICERS

Steven S. Simpson, Chair

Steven G. Tappan, Vice Chair

Rolf Benirschke, Vice Chair

Gary E. Knell, Treasurer

E. Jane Finley, Secretary

TRUSTEES

Kathleen Cain Carrithers

Javade Chaudhri

Adam Day

Clifford W. Hague

Bryan B. Min

Kenji Price ‘Aulani Wilhelm

24

Our care specialists offer 24-hour, around-the-clock care to wildlife at the San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park.

Our nutrition specialists utilize a combined 410 years of experience and specialized training to create diets for 19,000+ individual animals daily.

We are the only caretakers of platypuses outside of Australia.

Caring for this unique species allows us to raise awareness and design conservation strategies for this freshwater-loving, egg-laying mammal.

11,000

In our Wildlife Biodiversity Bank’s Frozen Zoo®, we care for over 11,000 individual cell lines from more than 1,250 species and subspecies.

TRUSTEES EMERITI

Berit N. Durler

Thompson Fetter

Richard B. Gulley

Robert B. Horsman

John M. Thornton

Paul A. Baribault

President and Chief Executive Officer

Shawn Dixon

Chief Operating Officer

David Franco

Chief Financial Officer

Erika Kohler

Executive Director, San Diego Zoo

Lisa Peterson

Executive Director, San Diego Zoo Safari Park

Nadine Lamberski, DVM, DACZM, DECZM (ZHM)

Chief Conservation and Wildlife Health Officer

Wendy Bulger

General Counsel

David Gillig

Chief Philanthropy Officer

Aida Rosa

Chief Human Resources Officer

David Miller

Chief Marketing Officer

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance has joined the Oiled Wildlife Care Network (OWCN), an initiative based at the University of California, Davis, that brings together partners from over 40 member organizations to rescue and rehabilitate wildlife affected by oil or chemical spills in California and support wildlife care efforts related to spills around the world. As members of OWCN, our team members will be trained to care for wildlife that are or could be impacted by oil or chemical spills, on land or in water, in Southern California. With so many local species vulnerable to the effects of spills, it is imperative that we are ready to mobilize and respond in case of an environmental emergency.

Because there are only two northern white rhinoceroses (NWR) remaining on Earth, rescuing this species from extinction will require the use of frozen NWR cells and assisted reproductive technology. In a recent study, our team simulated the fitness of a population of NWR restored from the cells of eight individuals banked in our Frozen Zoo®. We analyzed the genomes of the NWR cells and estimated the level of harmful mutations that could reduce rhino fitness. Our resulting models suggest that by regularly reintroducing new individuals born from the banked cells, we could establish a genetically healthy population. This incredibly promising result is a key piece of our goal to rescue NWR, as it suggests that a limited group of founder cell lines could still give rise to a sustainable rhino population.

Our team traveled to Puerto Maldonado, Peru, to provide clinical support for our partners at Taricaya Ecoreserve and Amazon Shelter, which work to rehabilitate injured wildlife and release them back into the surrounding Amazon. Though we expected to perform up to 40 exams during our 8-day visit, the success of our collaboration with local veterinarians allowed us to perform over 100 examinations on a diversity of species, including primates, parrots, and Andean bears. The procedures we assisted with included preventative health assessments, prerelease exams, and genetic and mercury testing. We also held wildlife health training sessions for staff and mentored 10 local vet students. This visit was part of our ongoing collaborative efforts to rescue and protect wildlife in the Peruvian Amazon.

Q QWhat was it like to intern with SDZWA?

The first two years, I was an education specialist for our summer camps. Then I worked alongside wildlife care specialists to learn how to care for wildlife. I had no idea what a fun world I would be getting myself into. I didn't even know what an ungulate was before starting my internship! Eight years later, I’m still just as excited to work with these incredible species.

Why did you want to continue your career with SDZWA?

After seeing firsthand how much care goes into each individual—from a small duiker to a large rhino—I knew I wanted to be a part of this place for a long time. I’ve grown up alongside these animals, and seeing them have calves of their own brings my journey full circle.

QWhat motivates you to help lead the summer intern program?

I believe in setting the next generation up for success. I want to make sure each and every intern gets the best foundation for their career goals, whether that is becoming a wildlife care specialist or not.

As a senior wildlife care specialist at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park, Alexa works with ungulates (large hoofed mammals, including rhinos and giraffes). She interned with San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance (SDZWA) for three summers before joining the wildlife care team. She now helps lead the summer intern program.

Q Q

What’s the most memorable wildlife moment you’ve witnessed?

I was fortunate to care for an okapi named Mbaya for over four years. Being with Mbaya through two of her pregnancies and subsequent births is a highlight of my career. One special moment was the day after she gave birth. She let her calf venture into an area near where I was working, and when she saw I was there, she went to lie down. She trusted me with her two-day-old calf, and I will cherish that moment forever.

What would you say to those thinking about interning with SDZWA?

DO IT! SDZWA is a great organization that can provide an amazing foundation for any future career. The job experience is great, but the people you’ll meet make this place special. Even if you don't go into the field of your internship, it’ll point you in the right direction, and you’ll have a team supporting you along the way. Someone took a chance on me eight years ago, a student freshly out of college with very little experience with wildlife. I got the opportunity to turn it into a wonderful career where my passion and knowledge are utilized every day to change lives for the better.

Kim Gray, curator of herpetology and ichthyology for SDZWA, explains the cold, hard facts about reptiles and temperature sex determination.

With most wildlife species, modes of sex determination in embryos are found at the genetic level. A location in the gene triggers a specific

sex trait, causing the embryo to become male or female. This process is called genotypic sex determination (GSD). Some wildlife species have what scientists refer to as environmental sex determination (ESD). In species that exhibit ESD, environmental factors—such as the amount of daylight exposure, demographics of adult

population or social environment, and temperature—can all play a critical role in determining if the embryo will become male or female. With reptiles that exhibit ESD, it is strictly the temperature the eggs are exposed to during incubation that plays the key role in this process, and it is referred to as temperature sex

(TSD).

Many lizard, turtle, and crocodilian species exhibit this form of natural history. It varies among these groups as to if a slightly warmer or cooler temperature results in the offspring being male or female. With climate change

A location in the gene triggers a specific sex trait, causing the embryo to become male or female.

and increasing temperatures, the science community is concerned that consistent increases in temperatures have the potential to significantly affect reptile populations. In a normal climate, the sex ratios of reptiles that have TSD exhibit a mix of males and females produced. With the increasingly high temperatures, however, it is anticipated that entire populations can potentially flip to become either all males or all females, depending on which temperature triggers the corresponding sex in the embryo.

Over time, this shift in demographics of a population to where higher numbers of only one sex are present can cause catastrophic impacts on the species’ ability to reproduce and have self-sustaining populations.

For example, a crocodile species that has this trait lays eggs in a nest, and if the nest temperatures are slightly cooler, the offspring will be female, and if the temperatures are a bit warmer, the

offspring will be male. This difference is only about four degrees, so as temperatures rise and consistently stay higher during the months of incubation, then more and more eggs will hatch as male, eventually causing entire populations to be all male or with fewer and fewer females, which may also cause additional inbreeding issues.

This is part of why habitat preservation is so critical to conserve species with TSD and ESD, as this provides the wildlife with the widest available space and thus potential temperatures they can choose from to build nests and lay their eggs. With reduced habitats, wildlife have fewer options, and these impacts amplify increasing risk to populations long-term. By studying egg incubation parameters and reptile behavior, we can learn the critical components to nesting behaviors and use what we learn to help build ex situ populations and support conservation initiatives that help ensure climate stability.

For decades, river hippos have played a big role for San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. In 1936, guests were awed by the arrival of the San Diego Zoo’s first river hippo, Puddles, a one-year-old genial giant who actively sought attention and often turned somersaults in his pool. Few people at the time had seen this species “in person,” and his presence helped keep the Zoo’s gates open during the lean years of the Great Depression. Rube and Ruby arrived as a pair four years later, and were still living there in the early 1980s. Since then, numerous other river hippos have come to live—and reproduce—at the San Diego Zoo, becoming ambassadors of sorts for hippos in their native habitat.

People are drawn to hippos for many reasons, from their size and shape to their reputation as the most dangerous land mammal in Africa. All these reasons—and more—explain why we can’t help but observe hippos with what Jen Chapman, a senior wildlife care specialist at the Zoo, calls “wonder and excitement.” And the San Diego Zoo’s newly upgraded Hippo Habitat is the perfect place to spend some time getting to know the resident hippo duo, Funani and her female calf, Amahle (pronounced ah-MA-shleh).

Despite the fact the word “hippopotamus” comes from a Greek word meaning “water horse” or “river horse,” the river (or common) hippo Hippopotamus amphibius is not related to equines—its closest living relatives (besides pygmy hippos) may be pigs or whales and dolphins. These well-rounded mammals are easily identified by their gray-to-brown skin, barrel-shaped body, short legs and tail, and huge head. Their size also makes them hard to miss—although they start life at less than 100 pounds, at adulthood, male river hippos can weigh more than 9,000 pounds, while females average 3,000.

Native to sub-Saharan Africa, river hippos are found in and around lakes, rivers, and mangroves, and are built for life in the water. With their

Hippos’ “blood sweat” is really a reddish mucus that helps protect their skin. DID YOU KNOW?

eyes, ears, and nostrils on the top of their head, hippos can hear, see, and breathe while most of their body is underwater. Hippos are equipped with a set of built-in “goggles”: a clear membrane covers their eyes for protection while still allowing them to see when underwater. Their nostrils close, and they can hold their breath for up to 30 minutes. Hippos can even sleep underwater, using a reflex that allows them to bob up, take a breath, and sink back down without waking up.

Despite all these adaptations for an aquatic life, hippos can’t swim— or even float. The density of their bodies makes floating impossible, so they move around by pushing off from the bottom of the river or simply walking along the riverbed in a slow-motion gallop, lightly touching the bottom with their toes, which are slightly webbed. And as adept as they are in the water, hippos can cover dry ground, too, and are capable of reaching a running speed of 15 miles per hour.

During daylight hours, hippos spend much of their time wallowing in shallow water to help keep cool. The hot African sun can be intense, and hippos have built-in protection against its rays. Their bodies produce “blood sweat” that is neither blood nor sweat—it’s a reddish mucus. When it dries, it crystalizes, creating a layer that locks in moisture and helps decrease their rate of dehydration when out of the water. Blood sweat also reflects the sun’s rays like sunscreen and has antiseptic properties to aid in healing wounds. In the evening, after the hot sun has set, hippos come out of the water for about six hours of grazing. Despite their enormous weight, hippos eat an average of only 88 pounds of food a night, which equals about 1 to 1.5 percent of their body weight. By comparison, the largest cattle eat 2.5 percent of their body weight each day.

The African wilderness can be unpredictable, and there are dangers hippos must face. Disease and drought are possible, as is predation by crocodiles, hyenas, leopards, and lions. While hippos may appear cute, they are considered among the most dangerous and aggressive of all mammals. And should a hippo need to defend itself, or a mother its calf, they are armed—not to the teeth, but with them. Hippos’ canine and incisor teeth grow continuously, with canines reaching 20 inches in length. And unfortunately, these teeth are one of the reasons their population is declining, as hippos are often poached for their teeth as part of the ivory trade. Other challenges river hippos face in their native range are habitat loss and diversion of water for agriculture, which impacts the natural waterways hippos rely on. River hippos are listed as Vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species.

The water’s fine: With the location of their eyes, ears, and nostrils— along with other adaptations—hippos are specially suited to spend a lot of their time in the water.

“

Team Hippo: As unofficial ambassadors for their species, Funani (left) and Amahle help spread the word about hippo conservation as guests form a connection to these amazing semi-aquatic mammals.

This habitat has always been a special place for people to connect with these amazing animals. But in line with our mission, we always improve where we can, whenever we can.”

At the San Diego Zoo, Funani and Amahle have taken to their refreshed habitat along Hippo Trail in Lost Forest like hippos to water. The aquatic ecosystem features 110 feet of crystal-clear glass for underwater viewing; a new, state-of-the-art water filtration system that can filter the entire pool—up to 210,000 gallons of water— every hour; improved vantage points for

guests; and expanded habitat features for the hippos. Greg Vicino, vice president of wildlife care at the San Diego Zoo, sees the hippo home improvement project as a win-win for the hippos and Zoo guests. “This habitat has always been a special place for people to connect with these amazing animals,” he says. “But in line with our mission, we always improve where we can, whenever we can.”

—GREG VICINO

Vice president of wildlife care

As impressive as the upgrades are, it’s still Funani and Amahle that attract guests to the habitat, Jen notes. “Having the opportunity to work on a great team caring for river hippopotamuses for over a decade has only strengthened my respect and admiration for these amazing mammals. My hope is that guests will have their moment of wonder and excitement, too.”

As the sun goes down, your wild adventure is only just beginning! Join us this summer to rock and roar until 9 p.m. with live music, entertainment, and performances. Stay late with us for all the family fun and excitement of Nighttime Zoo!

Polar bears live in one of the harshest environments on the planet: the sea ice of the Arctic. Spanning an area three times the size of the continental United States and more than 35 degrees of latitude, polar bears roam across areas that can get as cold as -50 degrees Fahrenheit, and in winter are covered by 24 hours of darkness. To study polar bears, conservation scientists are constantly looking for new ways to gain insight and add value to research methods. Increasingly, scientists are turning to polar bears living in zoos to help fill knowledge gaps, including Tatqiq, Kalluk, and Chinook here at the San Diego Zoo.

When bears are sedated in their native habitat for conservation research and management, biological samples, including hair, often are collected. Hair can provide valuable insight into polar bear diet, stress, and even pollutants that have accumulated. When analyzed in a laboratory, stress hormones and pollutants will show up in the results, giving scientists valuable insight. However, a key aspect of the sample information was missing: how long does it take to grow polar bear hair? If scientists could understand this more precisely, they could then understand the length of time reflected in the laboratory measurements of wild samples.

In 2020, 19-year-old female polar bear Tatqiq was chosen to help answer this question. Working with polar bear scientists from the United States Geological Survey and the University of Washington, wildlife care specialists were able to dye a large spot of fur on her

DID YOU KNOW?

Polar bears are the only bear species classified as marine mammals.

rump. She was fed a meatball containing a biomarker two times over the course of the year-long study, which would then show up during analysis (the biomarker was completely harmless to her). Then, every week for an entire year, a hair sample was noninvasively collected from the dyed patch. Once analyzed, the researcher would be able to locate the biomarkers in the hair samples and, knowing the dates they were consumed, measure how far apart they appeared in the hair samples, therefore determining how fast polar bear hair grows.

Up until recently, all the data on wild polar bears collected via tracking collars was only from adult female bears. You might ask why. It all relates to how polar bears are built. Male bears have incredibly large necks—

bigger in circumference than their heads. This means a collar placed on them will easily slip off as soon as they tilt their heads down toward the ground.

In collaboration with 3M, partner organization Polar Bears International begans began creating different prototypes of possible devices that could be used to study juvenile and male polar bears. These tracking tags would attach directly to the bear’s fur between their shoulder blades, allowing them to be placed on any bear, regardless of age or sex. Since bears naturally shed their fur seasonally, the devices would eventually drop off on their own. In 2021, the prototypes were sent to several zoos for testing. Two of our bears (27-year-old female Chinook and 21-year-old male Kalluk) were chosen to wear the devices to look at things such as how sturdily they attached to the

bear, if the bears were able to get them off/ how long they stayed on, or if they broke. This testing allowed for improvements to be made to the devices at a much quicker and more efficient rate than if they were tested out in the middle of the Arctic tundra. Our bears were able to rub the devices off within two days. Once they were off, the devices were sent back to the scientists to allow for the necessary modifications.

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance (SDZWA) researchers are currently working on many different conservation projects involving polar bears, including in Canada, which is home to two-thirds of the world’s remaining polar bears and is projected to have the last remaining sea ice refuge. There we work with our partners at Environment and

Field studies:

(Facing page, clockwise from top left)

Noninvasive tracking devices help scientists study individual bears over time. The genetic makeup of polar bear populations is changing due to a range of factors.

Co-author Nicholas Pilfold, Ph.D., collects a hair sample. (This page) Polar bears depend on sea ice for their survival and, In some areas, for maternal dens for the birthing and raising of cubs.

Climate Change Canada, the University of Alberta, and the University of Manitoba on understanding the health, movement, and population status of polar bears.

Our fieldwork primarily occurs in the Hudson Bay, home to the world’s best- and longest-studied population of polar bears. Each year we assist in the deployment of GPS ear tag transmitters on polar bears, which allows us to monitor migratory pathways and habitat use. In addition to deploying tags, we also collect physical measurements and biological samples and inventory the bears for population management. The biological samples have provided us insight into the health of the polar bear population, including a study we recently led examining exposure to infectious disease pathogens. The biological samples also provide genetic information, giving a wide range of indica-

tors about how the bears are being affected by rapid environmental change. Our current postdoctoral associate, Dr. Ruth Rivkin, is leading a study to understand how the genetic makeup of polar bear populations is changing now and will likely change due to future sea ice conditions. These assessments will allow us to explore potential future conservation management actions such as assisted migration and genetic rescue. In Svalbard, Norway, we have a multiyear study on maternal dens. Svalbard is a critical high-Arctic denning area for female polar bears, and they use the steep snow-covered slopes to dig their dens and birth their cubs. We have been working with our partners at Polar Bears International and the Norwegian Polar Institute to deploy remote cameras that can monitor the den sites. The data gathered gives us insights into how mother

polar bears are coping with environmental change and how they behave with their young outside of the den before taking them on a life-changing journey to the sea.

SDZWA’s polar bear conservation research extends into the far reaches of the circumpolar Arctic. We collaborate with partners across the Arctic on cutting-edge research to understand how polar bears are being affected by climate change and work together to provide conservation solutions.

Becky Wolf is a senior wildlife care specialist at the San Diego Zoo. Nicholas Pilfold, Ph.D., is a scientist for SDZWA.

With its mix of unique features and characteristics, the platypus has intrigued people since its discovery in the late 18th century. I remember learning about Australian animals and reading about the platypus when I was in grade school, and I was hooked. So it was a full circle moment when, in the fall of 2019, I was at Los Angeles International Airport waiting for two platypuses to arrive. It’s been five years since Birrarung and Eve

came to the San Diego Zoo Safari Park, and since then I have developed an even deeper appreciation for these fascinating mammals.

For their arrival, a new facility was built, taking recommendations and tips from other platypus houses in Australia. The platypus pair acclimated to their new home pretty quickly.

One of the first things guests notice when they visit the Nelson M. Millsberg Platypus Habitat is the habitat is complete-

ly dark. In their native range, platypuses are nocturnal, and their foraging, courtship, and breeding behaviors all occur in the water. So when walking in, it takes a few minutes for guests’ eyes to adjust to our “moonlight” setting. Most guests see our platypuses active in this lighting; in the summer (while the park has extended hours), they may get the chance to see the area with the “sunrise” setting slowly starting to kick on. When the lights begin to come on, this sends a signal to the platypuses that they should start getting ready to sleep.

Once out of the water, a platypus will find a comfortable spot (usually a dark, cool burrow) and rest for up to 12 hours. With the platypuses resting in their nest boxes, we quietly close off access to the pools and get to work.

Our day starts bright and early at 6 a.m., and the first thing we do is look for where the platypuses have chosen to sleep. The male, Birrarung (named after a river in Australia; we call him Birra) sometimes likes to sleep in, and when we find him in a nest box, I can always count on finding him on top of any substrate or blanket, quietly

greeting and sometimes nodding while I carefully give him a brief morning “hello.” Eve (she was named after Evelyn, one of her care specialists in Australia) is not as quiet—she likes to burrow herself as deep as she can get, and even before I open her nest box, she usually greets me with a low grumble. I imagine it’s her way of telling me that she wants to sleep in a little longer.

Platypuses can forage for up to 12 hours each day, even longer under cold conditions. They are carnivores, and in their

DID YOU KNOW?

Platypuses don’t have stomachs— their food goes right to their intestines.

native range they commonly feed on bottom-dwelling crustaceans like crayfish, aquatic insect larvae, pupae, nymphs, and other invertebrates. When platypuses enter the water, their foraging behavior kicks in. Sometimes called duck-billed platypuses, these aquatic mammals have a unique, flexible bill perfect for catching and grinding up prey. Over 40,000 electroreceptors in the bill act as an antenna to detect prey direction and distance. Only living prey produce this signal, so we often joke that when we become platypus specialists, we also become crayfish specialists. We house

crayfish at the Safari Park, and have housed over 1,000 crayfish in this space.

Every day we try and enter the pools and replenish the supply of crayfish, earthworms, mealworms, blackworms, and crickets. Platypuses can weigh up to 6.6 pounds; ours weigh between 2.2 and 3.3 pounds, depending on the time of the year. They can eat over 20 percent of their body weight daily, and a lactating female can eat up to 100 percent of her weight each day!

One of the first things we learned when becoming platypus care specialists is how to safely work around these animals. Platypuses are born with spurs on the inside of their hind feet. Females eventually shed their spurs during development, but males’ spurs will grow to the size of a pencil point. The spur is attached to a gland, which produces large amounts of venom during the breeding season. This means we only carefully handle the platypus when needed, and don’t share space with the male in the pools. We can, however, share pool space with our female. Working in a pool while a platypus swims around will always be the career highlight for me.

Diving in:

(Left) Birrarung dines on a crayfish. (Facing page, clockwise from top) Author Luis Ochoa adds more crayfish to the pool for the platypuses’ hunting—and eating—pleasure. Platypuses are comfortable both on land and in water. When a platypus floats, about 10 percent of their body stays above the surface. Birrarung exits a burrow/tunnel to take a dip in the pool.

Platypuses are usually solitary. In their native habitats they would avoid each other through most of the year. Breeding is seasonal, and from late July through early November we give them access to each other. Like the echidna, the platypus is a monotreme. While most other mammals give birth to their young, platypuses lay eggs, incubate them, and nurse their offspring.

Found mostly in eastern mainland Australia, platypuses are elusive, and there isn’t much known about them. Luckily there is a strong support community, and once a month we participate in what I like to call a “Platty Chatty” with specialists in Australia who also care for platypuses. We meet over video call; with the time difference we have to meet in the late afternoon for us, early morning for them. This gives us an opportunity to share best practices, compare notes on breeding and courtship behavior, or even just share fun videos of platypuses interacting with their specialist after a great learning session.

The platypus has been around a very long time and is the sole living representative of its family Ornithorhynchidae and genus Ornithorhynchus. They are a resilient species, with whole-genome data suggesting that modern platypus populations can be traced back to at least 800,000 years ago. Lately, however, there has been cause for concern.

The Australia wildfires that ravaged regions of New South Wales in 2020 brought a lot of ash, debris, and erosion to the waterways. As these became more congested, food sources became scarce, and traveling and burrowing became more difficult for the platypus. They are currently listed as Near Threatened on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List, and the population is declining. As the species faces the threat of local extinction, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance is proud to support a cutting-edge conservation effort in southeastern Australia that benefits endemic wildlife, including the platypus. A collaborative team is using a new technology called environmental DNA to map the distribution to the platypus. As living things shed their DNA through skin, hair, scales, feces, and eggs, water samples are collected and filtered through a special unit that strains out cells and analyzes them to determine the wildlife present. San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance is pleased to be supporting the “boots on the ground” efforts to preserve endemic wildlife, including the platypus, for generations to come.

The Safari Park’s platypuses can be seen in the Nelson M. Millsberg Platypus Habitat, or on the live Platypus Cam at sdzsafaripark.org/cams/platypus-cam.

Luis Ochoa is a lead wildlife care specialist at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park.

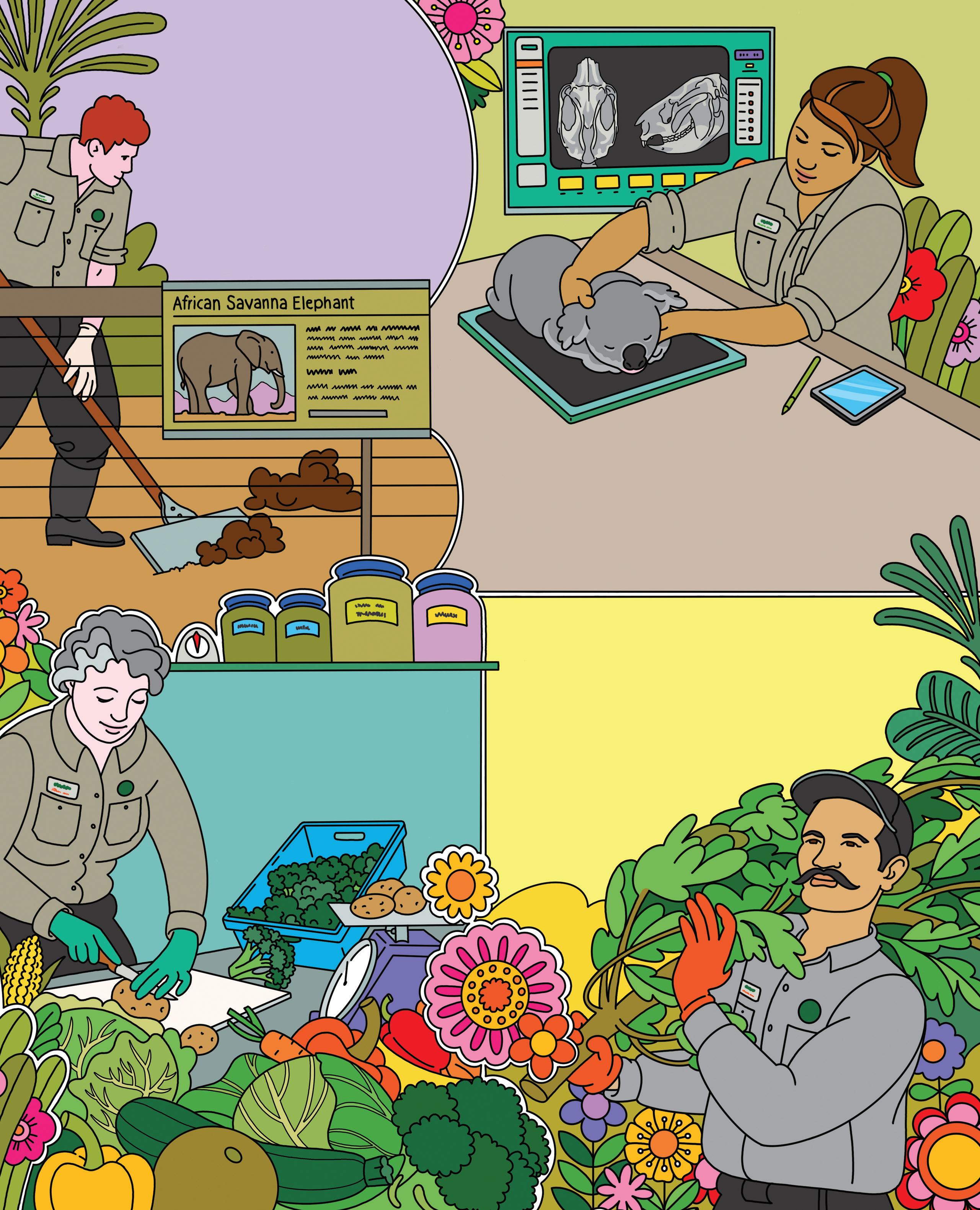

Providing the best possible care for wildlife is a job for more than one team. At the San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park, hundreds of professionals with different areas of expertise combine their talents to ensure wildlife are healthy and thriving. Here are just a few of the many roles that make it happen each and every day for more than 15,000 animals.

By Eston Ellis | Illustration by Amy Blandford

At the Zoo and Safari Park, wildlife participate in their own health care routines, thanks to the efforts of applied wildlife behaviorists. Just as you might do with your dog or cat, they offer positive reinforcement—such as a special food reward—for desired behaviors. This might include stepping on a scale for weigh-ins or getting into position for an ultrasound. By making these sessions positive and voluntary, exams can be done safely, effectively, and more frequently.

Doctors of veterinary medicine (DVMs) provide individual medical care for hundreds of species. They diagnose illnesses, prescribe lifesaving medications, perform surgical procedures, create regimens for patient recovery, and provide physical rehabilitation for postoperative and geriatric wildlife.

These experts are responsible for around-the-clock care of wildlife. Working closely with the animals they care for, they get to know each individual’s traits and temperaments, feeding them and cleaning their habitat, monitoring behavior and assessing overall health, and otherwise ensuring they thrive.

Researchers, nutritionists, and nutrition warehouse team members create the right diet for every species and individual, including daily diets, prescription diets, and other meals for wildlife with particular needs.

Working alongside DVMs, clinical registered veterinary technicians (RVTs) help care for the health and well-being of wildlife. Across our expansive savanna field habitats, in our hospitals at the Zoo and Safari Park, and everywhere in between, they assist with exams and procedures.

The Zoo and Safari Park grounds are lush botanic gardens, with over two million plants. In addition to being beautiful, many serve other purposes as well. Leaves and branches are used to feed wildlife ranging from ants to elephants, including reptiles and birds. At our two parks and two browse farms, browse team members grow and harvest an incredible variety of fantastic foliage.

San Diego Zoo

9 a.m.–9 p.m.

San Diego Zoo Safari Park

9 a.m.–7 p.m.

Hours*

San Diego Zoo

9 a.m.–9 p.m.

San Diego Zoo

Safari Park

August 1–11

9 a.m.–7 p.m.

August 12–31

9 a.m.–5 p.m.

sdzwa.org

619-231-1515

*Exceptions apply. Please check our website daily for the latest updates on opening and closing times.

(Z) = San Diego Zoo (P) = Safari Park

THROUGH SEPTEMBER 2

THROUGH SEPTEMBER 2

As the sun goes down, your wild adventure is only just beginning! Join us this summer to rock and roar until 9 p.m. with live music, entertainment, and performances. Stay up late for all the family-friendly fun and excitement of Nighttime Zoo! (Z)

JULY 19 AND AUGUST 16

Plant Day

On these special days, guests can take a rare look inside the Zoo’s Orchid House (and visit the plant sale) from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Discover more about the 700,000 plants we care for when you hop on the Botanical Bus Tour at 11 a.m., and check out the Carnivorous Plant Greenhouse from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. Free with admission; no reservations needed. (Z)

JULY 28 AND AUGUST 11

Member Exclusive Early Hours Rise and shine with the sights and sounds of the San Diego Zoo. One Sunday each month, members can enter the parks one hour before the general public. To join us, simply present your qualifying membership card at the main entrance beginning at 8 a.m. (Z) EVERY DAY

Wild Perks SM

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance members are eligible for Wild Perks SM . Show your membership card each time you make an on-grounds purchase and save up to 20%, depending on your membership level. Some exclusions apply; for details, visit sdzwa.org/membership/ wild-perks (Z) FOR MEMBERS

AUGUST 10–11

Join us at the Safari Park to celebrate World Elephant Day and discover the wildlife of our Savanna Conservation Hub with special activities, wildlife care specialist talks, and more. (P)

OFFERED DAILY

Journey into the Wild

Join our wildlife care specialist team as they introduce you to wildlife ambassadors representing conservation work in our Amazonia Conservation Hub in South America as well as right here in the Southwest. This conservation presentation begins at 2 p.m. daily at Benbough Amphitheater. (P)

JULY 28 AND AUGUST 11

Member Exclusive Early Hours Rise and shine with the sights and sounds of the Safari Park. One Sunday each month, members can enter the parks one hour before the general public. To join us, simply present your qualifying membership card at the main entrance beginning at 8 a.m. (P)

EVERY DAY

Wild Perks SM

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance members are eligible for Wild Perks SM . Show your membership card each time you make an on-grounds purchase and save up to 20%, depending on your membership level. Some exclusions apply; for details, visit sdzwa.org/ membership/wild-perks. (P)

Visit the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Explorers website to find out about these and other animals, plus videos, crafts, stories, games, and more! SDZWildlifeExplorers.org

The San Diego Zoo is open late all summer long, and a whole new world wakes up after dark. Take this quiz to discover which nocturnal species you are, then join us for Nighttime Zoo to connect with these fascinating species!

What is your go-to midnight snack?

A. Fruits and nuts

B. Whatever you can eat by the handful

C. Small bites

D. Something meaty

What is your best skill?

A. Strength

B. Problem-solving

C. Attention to detail

D. Stealth

Where are you going on your late-night adventure?

A. Stroll on the beach

B. Into the woods

C. The best lookout point

D. A grassy field

What is your secret talent?

A. Climbing

B. Finding hidden treats

C. Flexibility

D. Lifting heavy things

If you got:

MOSTLY A

You’re a Coconut Crab

Good night, largest arthropod in the world! These giant crabs can climb to the top of palm trees and crack open coconuts with their strong claws. During the day, they snuggle up in coastal burrows.

MOSTLY 1 2 3 4 5 B D

How do you sleep?

A. Tucked into a burrow

B. Cuddled in a cozy nest

C. Standing up!

D. Napping in the shade

You’re an Aye-Aye

Eyes wide open late at night? You’re an aye-aye. These lemurs are known for their unusual appearance and distinct extra-long fingers, which they use to pull grubs from tree bark. When the sun’s out, they’re tucked away in spherical nests.

MOSTLY C

You’re an Owl

Heads are spinning! A regular night owl, you thrive after dark. With keen eyesight, sharp hearing, and silent wings, owls are skilled nocturnal predators. When they’re not soaring the skies, these fascinating birds can sleep standing up.

You’re a Leopard

It’s hard to spot you, leopard. Whether slipping silently through the night or hiding their prey in treetops, these big cats are masters of stealth. Resting by day, they sleep in trees, caves, and bushes—anywhere in the shade and out of sight.

Sibling revelry is often on display at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park’s Tull Family Tiger Trail habitat. Sumatran tiger cub Puteri (left) is always ready to challenge her brother Hunan (right) to a friendly wrestling match. The cubs celebrate their first birthday this month. Photographed by Ken Bohn, SDZWA photographer.