50 Years of Conservation Science and Our 2025 Calendar

50 Years of Conservation Science and Our 2025 Calendar

December 13, 2024, through January 5, 2025*

WE’RE AGLOW WITH THE SPIRIT AND MAGIC OF THE HOLIDAY

“Merry and bright” takes on a whole new meaning as the Zoo lights up the night with family-friendly entertainment, specialty sips and snacks, and amazing new illuminated experiences. Come help us ring in the season!

Join us at Albert’s Restaurant to indulge in the magic of Jungle Bells with a delicious three-course meal. Savor the season with our curated wine pairings and holiday-themed cocktails.

Book online through OpenTable zoo.sandiegozoo.org/dining/alberts

*Visit zoo.sandiegozoo.org/jungle-bells for dates, times, and exceptions.

MEMBERS are invited to join us for a Jungle Bells preview on December 13

November/December

4 No. 6

Journey through Our Conservation Work San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance safeguards wildlife in eight Conservation Hubs around the world. To learn more about our collaborative conservation programs, including our wildlife care at the San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park, visit sdzwa.org.

For decades, SDZWA has used a unique combination of cutting-edge science and wildlife care expertise to build hope for the future.

SDZWA is dedicated to protecting and restoring biodiversity through projects in our eight Conservation Hubs. Our 2025 calendar offers 12 examples of what SDZWA conservation efforts look like.

Cells may be the smallest unit of life, but they make up all living organisms in nature. Take a closer look at the size and structure of some of the miniscule-yet-mighty building blocks of life.

MANAGING EDITOR Peggy Scott

STAFF WRITERS

Eston Ellis

Elyan Shor, Ph.D.

Alyssa Leicht

Ellie McMillan

Sandy McCann

COPY EDITOR Sara Maher

DESIGNER Kaitlyn Lara

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Ken Bohn

Tammy Spratt

DESIGN AND PRODUCTION

Kim Turner

Lisa Bissi

Jennifer MacEwen

PREPRESS AND PRINTING Quad Graphics

Follow @sandiegozoo & @sdzsafaripark.

Share your #SanDiegoZoo & #SDZSafariPark memories on X & Instagram.

The Zoological Society of San Diego was founded in Octo ber 1916 by Harry M. Wegeforth, M.D., as a private, nonprofit corporation, which does business as San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

The printed San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Journal (ISSN 2767-7680) (Vol. 4, No. 6) is published bimonthly, in January, March, May, July, September, and November. Publisher is San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, located at 2920 Zoo Drive, San Diego, CA 92101-1646. Periodicals postage paid at San Diego, California, USA, and at additional mailing offices.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, PO Box 120271, San Diego, CA 92112-0271.

Copyright© 2024 San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. All rights reserved. All column and program titles are trademarks of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

If your mailing address has changed: Please contact the Membership Department; by mail at P.O. Box 120271, San Diego, CA 92112, or by phone at 619-231-0251 or 1-877-3MEMBER.

For information about becoming a member of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, please visit our website at ZooMember.org for a complete list of membership levels, offers, and benefits.

Paid subscriptions to San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Journal are available. Contact Membership Department for subscription information.

For half a century, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance has been at the forefront of groundbreaking science, supporting global biodiversity conservation.

As we celebrate nearly 50 years of transformative work, we honor Dr. Kurt Benirschke, the visionary behind our research department and the Frozen Zoo®, part of the Wildlife Biodiversity Bank. His approach laid the groundwork for our pioneering achievements, from genetic breakthroughs to advanced reproductive techniques, and his legacy continues to inspire us today.

From the forests of Vietnam, where our ecological monitoring is revealing new insights into endangered species, to the frozen tundra of Hudson Bay, where we track polar bears and study climate change, our Conservation Hubs serve as beacons of hope, connecting people with wildlife while driving positive outcomes globally.

At the Conservation Technology Lab, engineers are working with our wildlife care specialists at the Nikita Kahn Rhino Rescue Center, as well as partners at Loisaba Conservancy in Kenya. Together, they are developing cutting-edge camera systems to monitor and protect rhinos, deepening our understanding and enhancing our ability to safeguard their future.

The giant panda, featured on this month’s cover, symbolizes our commitment to wildlife’s future. For 30 years, our breeding and research programs have contributed to their recovery, helping them move from Endangered to Vulnerable status. Their journey reminds us that through collaboration and science, we can create lasting impacts for wildlife, people, and the planet we share.

Conservation starts with people. This work is only possible through your support. Together, we are making a meaningful difference for wildlife, with a shared commitment to a world where all life thrives.

As part of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s commitment to conservation, this magazine is printed on recycled paper that is at least 10% post-consumer waste, chlorine free, and is Forest Stewardship Council ® (FSC ®) certified. FSC ® is not responsible for any calculations on saving resources by choosing this paper.

Paul A. Baribault President and Chief Executive Officer Onward,

From biobanking and reproductive science to genetic rescue and wildlife health, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance has conceptualized, developed, and honed a unique set of skills and strengths that showcases the role of zoos in global conservation efforts.

The 250th California condor

chick hatched at the Safari Park, marking a milestone for the conservation of this magnificent species.

600K+

375

Our Native Plant Seed Bank represents over 375 unique plant taxa and conserves the diversity of San Diego County’s flora.

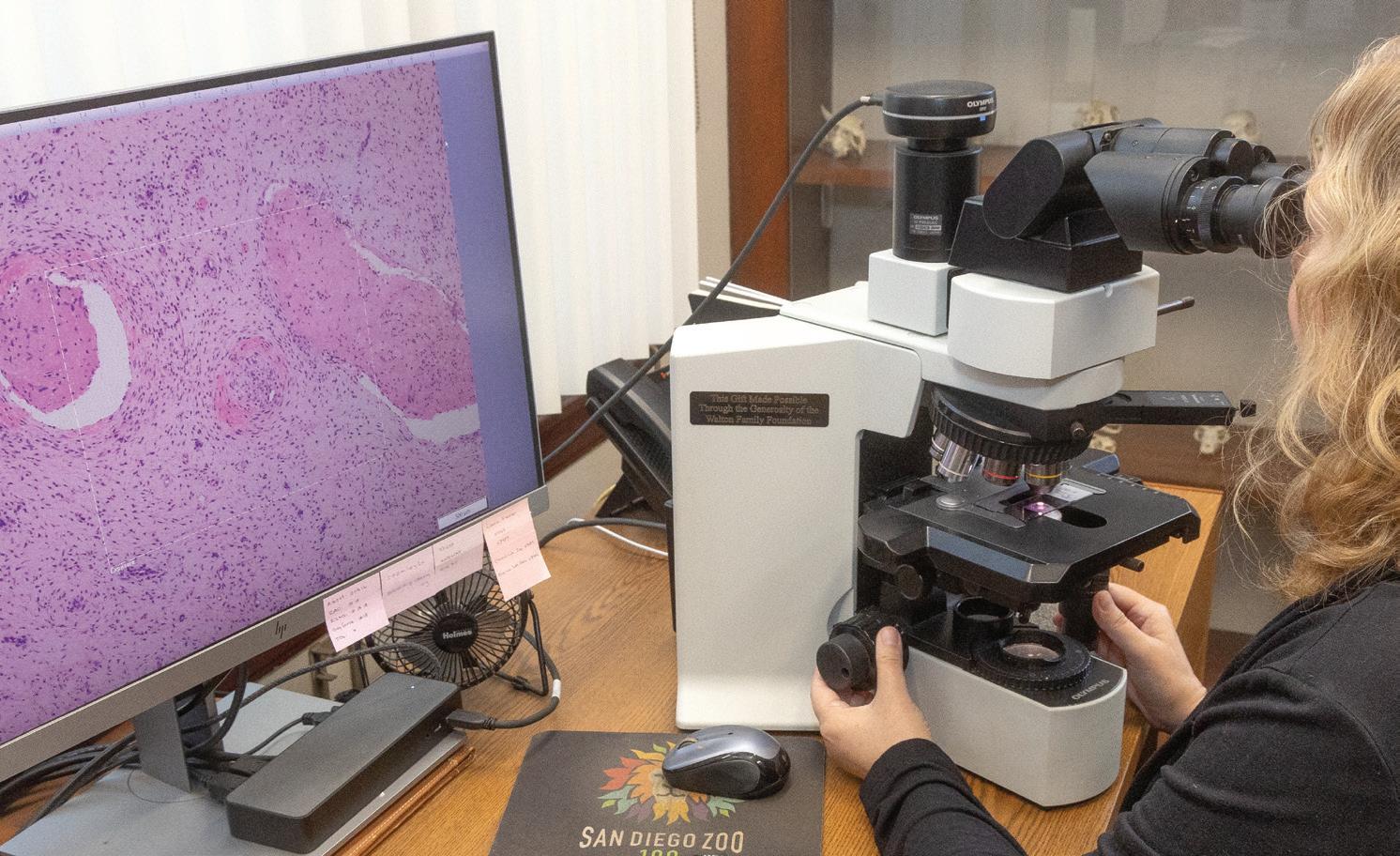

Since 1930, our Pathology Archive has collected over 600,000 microscope slides of tissue from more than 1,000 species—a repository of great value to conservationists around the world.

OFFICERS

Steven S. Simpson, Chair

Steven G. Tappan, Vice Chair

Rolf Benirschke, Vice Chair

Gary E. Knell, Treasurer

E. Jane Finley, Secretary

TRUSTEES

Kathleen Cain Carrithers

Javade Chaudhri

Adam Day

Clifford W. Hague

Bryan B. Min

Kenji Price ‘Aulani Wilhelm

TRUSTEES EMERITI

Berit N. Durler

Thompson Fetter

Richard B. Gulley

Robert B. Horsman

John M. Thornton

Paul A. Baribault

President and Chief Executive Officer

Shawn Dixon

Chief Operating Officer

David Franco

Chief Financial Officer

11,000

Our Frozen Zoo® contains over 11,000 living cell cultures, oocytes, sperm, and embryos representing nearly 1,000 taxa.

Erika Kohler

Executive Director, San Diego Zoo

Lisa Peterson

Executive Director, San Diego Zoo Safari Park

Nadine Lamberski, DVM, DACZM, DECZM (ZHM)

Chief Conservation and Wildlife Health Officer

Wendy Bulger

General Counsel

900

Spanning over 900 acres adjacent to the San Diego Zoo Safari Park, the Biodiversity Reserve acts as a wildlife corridor junction and is home to many species.

David Gillig

Chief Philanthropy Officer

Aida Rosa

Chief Human Resources Officer

David Miller

Chief Marketing Officer

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance (SDZWA) protects and restores nature in eight Conservation Hubs on five continents. Below are recent discoveries and progress reports from around the world.

Our team on Rota, part of the Northern Mariana Islands, recently released 22 endangered aga (Mariana crows) back into their island forests. The birds were hatched and raised in our on-island facility, where they could grow in safety away from predators. While in our care, we prepared them for survival in many ways, including by ensuring they learned to proficiently hunt and eat hermit crabs, one of their main sources of food. The timing of the release reflects the timing these birds leave their parents’ care and begin to forge strong social bonds with other aga. Our partners will continue to monitor the birds post-release. This is our team’s sixth season of releases, with a total of over 80 birds released. With only approximately 200 aga remaining on Earth, each released bird is a precious addition to this population.

The Annamite Mountains in Vietnam are one of the most biodiverse regions in the world; however, this area faces significant threats from hunting and habitat disturbance, and there is a lack of the comprehensive baseline data needed to address these threats. To fill in some of these data gaps, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance has launched an ecological monitoring project that combines trail cameras and surveys of local community members that will together clarify factors such as species behavior, abundance, distribution, and interactions. Working with Vietnamese agencies and partners, we have developed a survey questionnaire, conducted initial interviews with nearly 250 residents, and tested the placement of a trail camera grid. We will gather survey and image data and share these with local governments to help develop targeted conservation strategies.

Earlier this year, a team of researchers from San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance and our Canadian partners completed polar bear fieldwork in Canada’s Hudson Bay, where we deployed 10 GPS transmitting collars on adult females with cubs, 18 GPS transmitting ear tags on adult males and subadult bears, and 40 remote trail cameras to record information on polar bear feeding dynamics. The collars will stay on for one year (providing a location every four hours), and the ear tags stay on for three to six months (providing a location once per day). The data we collect are part of a long-term monitoring program, and analyses occur regularly for different aspects of polar bear biology. These efforts will help us understand and minimize the impacts of climate change on polar bears.

Stay fueled up by enjoying a delicious treat at one of our specialty snack stands on your next visit. The San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park thank our partners for their continued support!

QCan you tell us a bit about your research?

The current focus of my research is on mammalian species, including rhinos, dromedary camels, and Arabian oryx. Most mammals maintain body temperature at a narrow range, just like us, around 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit. With climate change, keeping body temperature constant can be very challenging! The heat can cause mass mortality for various mammalian species because as air temperatures increase, shade and water that are used to lower body temperature become scarcer. My research focuses on understanding what cells can tell us about species’ sensitivities to global warming so we can make informed conservation decisions.

QWhat’s the most interesting thing you’ve learned so far?

I’ve learned that cells behave like they’re little versions of the animals they belong to. For instance, rhinos maintain fairly constant body temperatures. Desert camels, on the other hand, can tolerate fluctuations in body temperature. When you expose rhino and camel cells to heat stress— simulating extreme heat waves—the rhino cells are noticeably affected, while the camel cells stay the same. This indicates how species’ tolerance to stressors can be seen at the cellular level, a new perspective that helps us develop innovative strategies to protect wildlife.

Our Wildlife Biodiversity Bank’s Frozen Zoo contains unlimited potential for the future of conservation. As a scientist for Biodiversity and Conservation Genetics, Carla looks at small things to see the big picture, working to understand what cells can tell us about complex conservation challenges so we can find solutions for wildlife.

Q

In your opinion, what are the most pressing issues facing biodiversity conservation today? Without a doubt, humandriven climate change is the biggest challenge. The unprecedented rate of extreme events, such as heat waves and flooding, has been destroying the lives and habitats of wildlife and human communities. The changes are overwhelming, and we’re losing species at alarming rates. It’s critical that we keep bringing awareness to these pressing threats and taking action to reduce our impacts and decelerate climate change.

Q

What is your favorite part about working at San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance? What I love the most about working here is the people. We’re all experts in our fields who are united by our efforts to save and preserve wildlife and their natural habitats. It’s very rewarding to work in a place where there’s a collective effort for a noble mission.

Q

Any advice for aspiring wildlife conservationists?

Keep dreaming big, learning from others, and taking constant steps toward your goals. Don’t forget to also take risks, it’ll result in big leaps of growth! Eventually, you will get there. You’re capable of anything you put your mind to.

Ian Ingram, M.S., a conservation technology scientist for San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance (SDZWA) and leader of the Conservation Technology Lab, explores deep learning and its role in protecting wildlife.

Ablack rhino living on the savanna at our partner facility, Loisaba Conservancy, in Kenya will never meet a white rhino living at the Rhino Rescue Center (RRC) just down the path from the SDZWA Beckman Center for Conservation Science in Escondido, California. But they can help each other. They help each other by helping us build

machine learning technologies that contribute to the conservation of both their species.

At the core of these technologies is deep learning—a groundbreaking development in how we humans use the power of computers that has found its way into seemingly every domain of human existence, from healthcare to entertainment. Software and hardware engineers in the SDZWA Conservation Technology Lab (CTL) have been collaborating with the

wildlife care specialists at the RRC and our colleagues at Loisaba to develop tools that use deep learning in conjunction with field camera systems to help us protect and learn about rhinos. Combining camera imagery (both stills and video) and artificial intelligence in this way is often shorthanded as CV/ML, for “computer vision and machine learning.”

Specifically, in our work with the two populations of rhinos, we are trying

Combining camera imagery (both stills and video) and artificial intelligence is often shorthanded as CV/ML, for “computer vision and machine learning.”

to improve our ability to do two things with CV/ML: 1) automatically identify individual rhinos, and 2) automatically determine what behavior a rhino is exhibiting at a given moment.

The automatic identification of individual rhinos is important in Loisaba simply as an aid in ensuring that each of the 21 black rhinos translocated there this past January is accounted for on an almostdaily basis—a necessary and required element of the rhinos management. It also enables us to do science around the social networks of the rhinos in both Kenya and Escondido, monitoring a location important to the rhinos like a midden (a communal dung heap) to see who visits and when and which other individuals they are interacting with—studies that will also benefit from the CV/ML behavior recognition systems.

While some of our computer vision tools can be used with camera devices that are available off-the-shelf, like trail cameras, for some we need custom equipment. Two of the core pieces of made-to-order equipment we employ in this work, the CTL’s mobile connection station and the tiny ScrubCam, were developed for use in the SageBRUSH (Bio-Reserve Ubiquitous Sensing in Habitat) system in our Biodiversity Reserve adjacent to the Safari Park. Customizing these devices for use in the context of our Savanna Conservation Hub is the project of our very first fellow in the brand-new SDZWA Kenyan Fellows in Conservation Technology program, Kiraoni Jackson Saruni.

White rhinos and black rhinos, the two extant African rhino species, are of course different from one another. To start, the white rhino is primarily a grazing

species, and the black rhino, a browsing species, as reflected in the respective shapes of their lips: broad and square in the white and hooked and nimble in the black. But the two species are morphologically similar enough that the majority of the machine learning techniques we develop for one are transferable to application with the other. In fact, many of these CV/ML techniques and systems have the potential to be transferable to SDZWA projects for many other species we help protect in our eight global Conservation Hubs.

The black rhinos in Loisaba and the white rhinos at the RRC are not just helping each other, but also helping polar bears, burrowing owls, elephants, mountain lions, 'alalās, platypuses, and gorillas, to name just a few. That in itself is quite an alliance.

BY NADINE LAMBERSKI, DVM, DACZM, ECZM (ZHM)

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance (SDZWA) is a conservation organization committed to saving wildlife worldwide. We strive to be the most effective wildlife conservation organization for the world by combining our skills and expertise in conservation science, wildlife health, wildlife care, and education and outreach.

Thinking ahead: Dr. Kurt Benirschke’s foresight about science’s role in conservation led to the establishment of the San Diego Zoo’s research department in 1975, which included the biological sample repository now known as the Frozen Zoo.

In 2025, SDZWA will celebrate 50 years of renowned conservation science work, initiated by Dr. Kurt Benirschke when he established SDZWA’s research department in 1975. This research department later became the Center for Reproduction of Endangered Species (CRES) and home of the biological sample repository now known as the Frozen Zoo®. But SDZWA’s commitment to wildlife conservation and scientific research can be traced back to our founder, Dr. Harry Wegeforth, who was a physician and advocate of science. A research committee was established as early as 1925, and the award-winning Zoological Hospital and Biological Research Institute (now known as the Scripps building) opened in 1927. In 1929, we became one of the first zoos to hire a staff veterinarian. A veterinary pathologist was added in 1964, paving the way for the systematic study of the health of wildlife in our care.

Our organization has always been committed to being more than a place to experience wildlife from around the world. We study wildlife in our care and use the knowledge gained to both improve our procedures and establish self-sustaining populations. For the first 20 years (1975–1995) there was an emphasis on learning more about the behavior, physiology, disease resistance, and genetics of endangered species, with the goal of improving animal reproduction, health, and well-being. A few examples include the use of noninvasive techniques for hormone monitoring in black rhinos, sex determination in California condors from a drop of blood, management strategies for breeding solitary species such as cheetahs, paternity testing in gorillas, and the veterinary management of malignant catarrhal

fever in wildebeest. Bringing scientists from different disciplines together to solve problems is the essence of our conservation work.

Over the next 25 years (1995–2020), the conservation challenges and research questions became more complex as the rate of human-caused species extinction increased dramatically. The skills and expertise of our team broadened to better meet this evolving need. I joined the organization in 2001 as a clinical veterinarian and was able to witness this evolution firsthand.

The Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center for Conservation Research opened in 2004 and became the new headquarters for our work. We changed the name from CRES to the Institute of Conservation Research. And we expanded our focus to preventing the extinction of plants as well as animals. We leveraged our knowledge of the species in our care and applied it to the conservation of wildlife in their native habitats. In 1996, we received our first pair of giant pandas and began a very comprehensive breeding and research program that eventually helped improve

the status of pandas in China. We initiated or expanded multiple species propagation and release programs, including for San Clemente Island loggerhead shrikes, Hawaiian forest birds, Pacific pocket mice, mountain yellow-legged frogs, and Torrey pines. We took over the management of the Desert Tortoise Conservation Center in Las Vegas, Nevada; the California condor program in Baja, Mexico; and the Stiefel-Behner Cocha Cashu Biological Station in Manú National Park, Peru. We designed headstarting programs to improve survival of endangered Caribbean

iguanas and desert tortoises. We engaged in polar bear conservation work supported by advances in conservation technology. We began offering conservation education programs to local high school students, hosted teacher training workshops, and launched a master’s degree program called the Advanced Inquiry Program in collaboration with Miami University. We also began community-based conservation work in Cameroon and northern Kenya.

While our conservation activities were evolving and expanding, so too was our Frozen Zoo, an irreplaceable biodiversity bank increasing in significance as the fields of genetic rescue and synthetic biology advance. With the establishment of the Frozen Zoo, SDZWA has been at the forefront of biodiversity banking since 1975. Living cell lines stored in this bank have been instrumental in bringing back valuable genetic diversity to the endangered black-footed ferret and Przewalski’s horse populations, increasing the odds of their species’ survival. Genetic rescue and advanced reproductive technologies utilizing samples preserved decades ago may be key to increasing the genetic diversity of white rhino populations in Africa.

In recognizing the scope and complexity of these global challenges, we know that we cannot do this important work alone. As an Alliance, we cultivate

A new hope:

(Left) Formerly extinct in native habitats, the Przewalski’s horse has survived for the past 40 years almost entirely in zoos around the world. All of the surviving horses are related to 12 Przewalski’s horses born in the wild. By reviving genetic diversity that was stored in San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s Biodiversity Bank, conservationists hope to expand the strength of the species’ population.

collaborative partnerships that amplify our impact. By prioritizing collaborations with motivated organizations and combining our expertise, we commit to projects that engage, respect, and benefit local communities and their heritage; enhance capacity and local leadership opportunities; support human-wildlife coexistence; promote healthy ecosystems; and meaningfully contribute to the equitable and sustainable management of the biodiversity upon which so many lives depend.

SDZWA is committed to working together to advance biobanking and to safeguard biodiversity on a global scale. In 2023, we partnered with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)

Species Survival Commission to form the Center for Species Survival: Biodiversity Bioanking, which aims to catalyze conservation action, collaboration, and communication. As the Center for Species Survival: Biodiversity Biobanking, SDZWA is a global leader in cultivating a network of conservation practitioners engaged in biodiversity banking.

I am so proud of the history of our organization and the invaluable contributions we have made over many decades. I am fortunate to lead an incredible team of scientists, wildlife health professionals, and conservation practitioners, and am excited about our current direction and future contributions to nature and people. Our work, and the

work of zoos and aquariums around the world, contributes to larger global initiatives (such as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals) that aim to restore biodiversity for a healthy, thriving planet. Working together, we can live in harmony with nature by 2050.

Nadine Lamberski, DVM, DACZM, ECZM (ZHM), is chief conservation and wildlife health officer for SDZWA.

Traverse Botswana’s diverse habitats as we delve deep into the most remote, wildlife-rich reaches of the Okavango Delta and Kalahari Desert.

Join Our Adventures to Botswana or the Amazon in 2025! Small Groups • Dedicated Hosts • Amazing Wildlife • Awe-Inspiring Locations

Encounter rainforest wildlife as we cruise aboard a deluxe riverboat along more than 400 miles of the Peruvian Amazon and its main tributaries to explore the river’s remote headwaters.

Book now! For details about these trips and all our Adventures, visit adventures.sdzwa.org .

BY MEGAN OWEN, PH.D. | PHOTOS BY KEN BOHN AND TAMMY SPRATT

In our eight Conservation Hubs around the world, our work is focused on realizing this vision by working with partners and local communities to protect and restore biodiversity. Through partnership and collaboration, we have committed to projects that engage, respect, and benefit local communities and their heritage; enhance capacity and local leadership opportunities; support human-wildlife coexistence; promote healthy ecosystems; and meaningfully contribute to the equitable and sustainable management of the biodiversity upon which so many lives depend.

AFRICAN FOREST Community is at the heart of everything we do in Cameroon’s Ebo forest, home to a rare population of lowland gorillas and the only chimpanzees in the world that are known for two different types of tool use. In this dense forest, critically endangered African forest elephants roam alongside a host of other bird, mammal, amphibian, and plant species. Critically important to this conservation program are the communities that have long lived in harmony with Ebo, and who work tirelessly to protect it.

AMAZONIA The jaguar is an iconic, wide-ranging big cat of the Americas, and one of the focal species in our Amazonia program. As for many large carnivores, living alongside human communities and human activities poses challenges. Our team in Peru is working with communities and partners to protect these powerful big cats and promote coexistence with the people that live alongside them. At the Wildlife Conservation Lab at Los Amigos, we are training students and early-career scientists in portable molecular technologies that are revolutionizing genomic science. At the Cocha Cashu Biological Station deep in the Amazon rainforest, we offer training courses to students, as well as a place for scientists to conduct research in a forest that is largely intact.

ASIA The illegal wildlife trade is a threat to an array of wildlife species in Asia, including sun bears, Asiatic black bears, tigers, orchids, carnivorous plants, and cycads. In Vietnam, our team works with local partners and communities to reduce consumer demand for wildlife products such as bear bile and tiger bone glue. And in Sumatra—one of the most populous islands in the world—our team is working to support coexistence between tigers and people in shared landscapes. The endangered Sumatran tiger is the smallest subspecies of tiger, and only an estimated 400 to 600 remain in native habitats due to the challenges of habitat loss and poaching.

AUSTRALIAN FOREST

We have been working with partners in Australia to protect koala populations for decades, and while the program had significant successes over that time, the bush fires of 2019–2020 were a stark reminder of how climate change-driven drought and weather patterns can drive catastrophic conditions for wildlife and people. In 2024, as part of our ongoing commitment to our partners in Australia, we embarked on an ambitious journey with the Taronga Zoo in Sydney, supporting their Platypus HQ, a conservation breeding and translocation center dedicated to the conservation of this unique duck-billed mammal.

OCEANS Climate change is impacting our oceans’ health on a global scale. Whether in the high Arctic archipelago of Svalbard, the Salish Sea, or off the California coast, our Oceans program is focused on mitigating the impacts of climate change on wildlife, and we’re using innovative technologies to do so. In the Arctic, sea ice losses challenge the successful emergence of polar bear mothers and cubs from maternal dens and also threaten coexistence with people as the ice melts and more bears come ashore. For the beloved killer whales of the Salish Sea, our teams are using innovative drone-based technologies to monitor population health. And closer to home, our team is working with partners and using advanced reproductive technologies to recover the sunflower sea star, a species that is essential to the health of the eastern Pacific kelp forests, and, as follows, the planet.

PACIFIC ISLANDS The Hawaiian Islands are home to an unparalleled array of unique wildlife species. In fact, about 90 percent of Hawai‘i’s wildlife species occur only there. On the islands of Hawai‘i and Maui, our program is largely focused on the recovery of endemic Hawaiian forest birds, including honeycreepers such as the ‘akikiki and ‘akeke‘e, and the ‘alalā, otherwise known as the Hawaiian crow, regarded in Hawaiian culture as ‘aumākua, or a family guardian. We are also working to save native palm trees in Hawaii and precious orchids in Palau. Habitat loss and non-endemic species have led to dramatic declines in forest birds, and climate change has exacerbated these losses, with malaria-carrying non-native mosquitoes further encroaching on forest bird habitat.

SAVANNA The arid rangelands of northern Kenya are home to some of the most iconic of east African wildlife species. African savanna elephants, African leopards, giraffes, black rhinoceroses, and many other iconic wildlife species share these rangelands with pastoralist communities, and water and grazing land are shared resources. Climate change-driven droughts challenge the healthy balance of this ecosystem and the survival of wildlife species. They also increase the likelihood of conflicts between wildlife and local communities. Our teams work with local communities to cogenerate restoration and coexistence solutions and support the health of wildlife populations.

SOUTHWEST The United States’ Southwest is a place of extraordinary natural beauty, with mountains, deserts, grasslands, and expansive stands of chaparral providing habitat for a diverse array of plant and animal species. It is also an area with extraordinary human population density and a history of expansive development, including infrastructure that fragments wildlife habitat. San Diego County is emblematic of the Southwest’s natural beauty and is the most biodiverse county in the contiguous U.S. It is also home to more threatened species than any other county in the U.S. In the greater San Diego region, our teams are committed to reversing this trend, with projects that include mountain lion coexistence, Pacific pocket mouse and mountain yellow-legged frog recovery, coastal scrub oak, and restoration of the iconic Torrey pine, a coniferous tree species found nowhere else.

SDZWA’s Wildlife Biodiversity Bank exists to further our efforts for a brighter future for all. Our 2025 calendar— which features some of our most promising successes—is a good place to start planning for one. Here’s to starting tomorrow, and next year, by engaging with wildlife today.

Cells vary in shape and function, and while some are enormous (the ostrich egg, the largest single cell in the animal kingdom, averages six inches long and weighs about three pounds), most cells can only be seen with the help of a microscope. The smallest object the human naked eye can see is approximately one-tenth of a millimeter (0.10 mm) in size—roughly the thickness of this piece of paper (0.15 mm), and the approximate diameter of a Southern white rhino egg (0.14 mm). Let’s zoom in and see how other cells measure up.

By Elyan Shor, Ph.D. | Illustrated by Amy Blandford

Egg

Blood Mammalian red blood cells (RBC) are round, don’t contain a nucleus, and are similar in size across species (a blue whale’s RBC are 0.008 mm in diameter; a brown rat’s RBC are 0.007 mm in diameter). Amphibian, reptile, and bird RBC are elliptical, contain a nucleus, and vary greatly in size across species. The three-toed amphiuma, a salamander native to the US, has the largest measured RBC of any animal on Earth (0.06 mm long).

The egg, or oocyte, is one of the largest cells by volume in the mammalian body. On average, a human oocyte is 0.11 mm in diameter.

Cells are small, but numerous

Although cell size doesn’t necessarily scale up with body size, the total number of cells does scale to body size. An adult human body contains approximately 30-40 trillion cells (not counting bacteria)—this is more than 100 times the estimated number of stars in the Milky Way galaxy! Meanwhile, the body of an adult African savanna elephant is estimated to contain over one quadrillion cells.

Feather A cell’s size and shape can change throughout its life cycle. During the growth phase, cells from a whooping crane’s emerging feathers measure about 0.09 mm long. During mitosis (cell division), these cells shrink to about 0.03 mm.

Plant

Plant and animal cells are alike, but not identical, in structure. In contrast to animals, cells from plants like king protea (0.05 mm long) are surrounded by a cell wall, use chloroplasts to synthesize energy (photosynthesis), and contain a fluid-filled central vacuole that provides nutrient storage and maintains the cell’s inner pressure.

* Cells vary in size between, and even within, individuals. All sizes listed here are averages.

ENDOPLASMIC RETICULUM

Skin

Fibroblasts are found in connective tissues such as bone, cartilage, and ligaments. These cells lend structure to organs and other tissues throughout the body. Manatee skin fibroblasts (0.08 mm long) help repair damage to their tough, one-inch-thick skin.

San Diego Zoo

9 a.m.–5 p.m.

Extended Hours during Jungle Bells

9 a.m.–8 p.m.

San Diego Zoo Safari Park

9 a.m.–5 p.m.

Extended Hours during Wild Holidays

9 a.m.–8 p.m.

sdzwa.org

(619) 231-1515

*Programs and dates are subject to change—please check our website for the latest information.

(Z) = San Diego Zoo

(P) = Safari Park

SELECT DATES IN DECEMBER 2024 AND JANUARY 1–5, 2025

The magic and spirit of the holiday season return! The Zoo lights up the night with amazing entertainment, featuring exciting new attractions and experiences. Bring the family and enjoy some tasty treats and the warmth of the holidays. On December 13, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance members are invited to enjoy a Jungle Bells Member Preview. (Z)

NOVEMBER 15 AND DECEMBER 20

Plant Day and Orchid Odyssey

On these special days, guests can take a rare look inside the Zoo’s Orchid Greenhouse from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., learn about the Zoo’s botanical collection on the Botanical Bus Tour at 11 a.m. and noon, and check out the Carnivorous Plant Greenhouse from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. A variety of plants will be available for purchase—all grown on site by Zoo horticulture staff. The Plant Sale takes place from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. in front of the Orchid Greenhouse entrance. (Z)

NOVEMBER 2–3

Wild Weekend: Oceans

Learn more about the wildlife of our Oceans Conservation Hub with special activities, wildlife care specialist talks, and more. (Z)

OFFERED DAILY Wildlife Wonders

During Wildlife Wonders at the Zoo’s Wegeforth Bowl amphitheater, presented daily at 2 p.m., wildlife care specialists will introduce you to wildlife ambassadors representing San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s conservation work around the world. Learn about amazing wildlife—from the Amazon to right here in our own backyard in San Diego. (Z)

FOR MEMBERS

NOVEMBER 3, DECEMBER 8

Member Exclusive Early Hours Rise and shine with the sights and sounds of the San Diego Zoo. One Sunday each month*, qualifying members can enter the Zoo one hour before the general public. To join us, simply present your membership card at the main entrance beginning at 8 a.m. *Excludes memberships with blockout dates (Z)

EVERY DAY

Wild Perks SM San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance members are eligible for Wild PerksSM Show your membership card each time you make a purchase and save up to 20%, depending on your membership level. Some exclusions apply; for details, visit sdzwa.org/ membership/wild-perks (Z)

SELECT DATES IN NOVEMBER AND DECEMBER

Spend evenings at the Safari Park until 8 p.m., go on a holiday expedition of light, and travel through places that twinkle and glow with holiday cheer. Musical entertainment, storytelling, and culinary treats round out the seasonal festivities. On November 29, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance members are invited to a Wild Holidays Member Preview. (P)

Botanical Africa Tram Tour at the Safari Park

Find out what’s growing on around the Safari Park during a new, flora-focused adventure. Offered Saturdays and Sundays at noon, join us to explore botanical wonders. Reservations are required and there is limited availability—first come, first served. The Botanical Africa Tram Tour is included with admission; visit any ticket booth at the Safari Park for your complimentary ticket. (P)

OFFERED DAILY

Journey into the Wild

Join our wildlife care specialist team as they introduce you to wildlife ambassadors representing San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s conservation work in our Amazonia Conservation Hub in South America, Savanna Conservation Hub in Africa, and Southwest Conservation Hub, right here in our own backyard. This conservation presentation begins at 2 p.m. daily at Benbough Amphitheater. (P)

NOVEMBER 3, DECEMBER 8

Member Exclusive Early Hours

Rise and shine with the sights and sounds of the Safari Park. One Sunday each month, members can enter the Safari Park one hour before the general public. To join us, simply present your membership card at the main entrance beginning at 8 a.m. (P)

EVERY DAY

Wild Perks SM

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance members are eligible for Wild PerksSM Show your membership card each time you make a purchase and save up to 20%, depending on your membership level. Some exclusions apply; for details, visit sdzwa.org/ membership/wild-perks (P)

Visit the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Explorers website to find out about these and other animals, plus videos, crafts, stories, games, and more!

SDZWildlifeExplorers.org

Naked mole-rat colonies live in large, dark burrows they dig underground. Just like in our own homes, they have rooms, or chambers, that serve different purposes. These small mammals have spaces for nesting, eating, and even going to the bathroom! Mole-rats have poor eyesight, so they rely on hearing, smell, and touch to navigate the tunnels. They feel what’s around them using fine hairs on their body. Wiggle your whiskers to help these little rodents find their way through the burrow.

Naked mole-rats can run both forward and backward through their mazes of tunnels. In this maze, you can only move forward!

Naked mole-rats aren’t moles or rats! They’re more closely related to porcupines or guinea pigs.

Sporting the characteristic striped and spotted coat, three-month-old Soona is the picture of Baird’s tapir calf perfection. Those markings help tapir calves blend in with the shadows of Central American forests. Her prehensile snout is stellar for sniffing—and plucking leaves from trees. Photographed at the San Diego Zoo by Ken Bohn, SDZWA photographer.