To the Rescue: at the Forefront of Saving Wildlife MAY/JUNE 2024

February 2025 Monarch Butterfly Migration Adventure Experience

For details about these trips and all our Adventures, visit Adventures.sdzwa.org

Join our Adventures to Madagascar or Mexico! Travel with us and experience the wonder of wildlife.

2024

2025!

Explore rare habitats, national parks, and private reserves.

.

September

& August

Madagascar Wildlife Adventure

the magic of hundreds of thousands of monarchs in flight.

Photos by: (top) Tammy Spratt/SDZWA, (bottom) provided by Natural Habitat Adventures

Journey Through Our Conservation Work

Vol. 4 No. 3

To learn more about our collaborative conservation programs, including our wildlife care at the San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park, visit sdzwa.org. May/June

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance safeguards wildlife in eight Conservation Hubs around the world.

Events 28 Wildlife Explorers Page

Last Look

Cover Story

10

To the Rescue

It takes quick action and collaboration to care for wildlife in crisis, and SDZWA and our dedicated partners are uniquely qualified to help.

Features

16

No Bird Is an Island

As part of a multi-organization recovery program, SDZWA is helping to protect San Clemente loggerhead shrikes and the habitat they share.

20

Waiting in the Wings

With its stunning array of avian wonders and lush greenery, the Safari Park’s Rainforest Aviary offers an immersive wildlife experience.

24

Visualize It

The enigmatic chameleon is known for its ability to change color. The technology behind radiographs allows us to take a deeper look at these fascinating lizards.

On the

Cover: Mountain lion cub Puma concolor

Photos by: (top) Ken Bohn/SDZWA, (middle) SDZWA, (bottom) Tammy Spratt/SDZWA

3

4

6

8

26

29

Photo by: Ken Bohn, SDZWA photographer

Contents 2 President/CEO’s Letter

By the Numbers

Findings

Meet Our Team

Hot Topics

10

2024

16 20

JOURNAL

MANAGING EDITOR Peggy Scott

STAFF WRITERS

Eston Ellis

Elyan Shor, Ph.D.

Alyssa Leicht

Arwen Neski

Ellie McMillan

COPY EDITOR Sara Maher

DESIGNER Christine Yetman

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Ken Bohn

Tammy Spratt

DESIGN AND PRODUCTION

Kim Turner

Lisa Bissi

Jennifer MacEwen

PREPRESS AND PRINTING Quad Graphics

Let's Stay Connected

Follow @sandiegozoo & @sdzsafaripark.

Share your #SanDiegoZoo & #SDZSafariPark memories on Twitter & Instagram.

The Zoological Society of San Diego was founded in Octo ber 1916 by Harry M. Wegeforth, M.D., as a private, nonprofit corporation, which does business as San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

The printed San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Journal (ISSN 2767-7680) (Vol. 4, No. 3) is published bimonthly, in January, March, May, July, September, and November. Publisher is San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, located at 2920 Zoo Drive, San Diego, CA 92101-1646. Periodicals postage paid at San Diego, California, USA, and at additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, PO Box 120271, San Diego, CA 92112-0271.

Copyright© 2024 San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. All rights reserved. All column and program titles are trademarks of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

If your mailing address has changed: Please contact the Membership Department; by mail at PO Box 120271, San Diego, CA 92112, or by phone at 619-231-0251 or 1-877-3MEMBER.

For information about becoming a member of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, please visit our website at ZooMember.org for a complete list of membership levels, offers, and benefits.

Paid subscriptions to San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Journal are available. Contact Membership Department for subscription information.

Science and Rescue for Wildlife

There is something incredibly special about the work we do to save, protect, and conserve the world’s wildlife. Every day we find hope in the projects and initiatives that are transforming the future for plants and animals around the world while adding vibrancy to the ecosystems we all share. San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance is proud to be at the forefront of conservation science and honored to fill a unique role in supporting wildlife rescue worldwide.

For over 100 years, we’ve partnered with wildlife conservation partners, universities, scientists, and other leading zoos to share our expertise and discover breakthroughs in wildlife health. By caring for the largest colony of koalas outside of Australia, we have a unique opportunity to leverage technology to uncover the hidden secrets of koala health found in their genomic structure. This invaluable information helps us develop conservation techniques that preserve genetic diversity and support sustainable populations of koalas worldwide. We also care for wildlife we coexist with in the Southwest, using our expertise in avian health to assist the San Clemente loggerhead shrike in its recovery. By creating a propagation program and caring for loggerhead shrikes in need throughout their native habitats, we are giving this incredible species the opportunity to thrive.

Our mission is to inspire a passion for nature, and we do this by connecting people through immersive conservation experiences at the San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park. With the support of wildlife allies like you, we offer world-class care and share new experiences and ecosystems—like the new Rainforest Aviary at the Safari Park—with the world. Conservation starts with people and takes all of us. We are so grateful for each of you, who help make our work possible and are a part of our Alliance. Together we are making a meaningful difference for wildlife, people, and the planet we all share in our commitment to a world where all life thrives.

As part of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s commitment to conservation, this magazine is printed on recycled paper that is at least 10% post-consumer waste, chlorine free, and is Forest Stewardship Council ® (FSC ®) certified. FSC ® is not responsible for any calculations on saving resources by choosing this paper.

2 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MAY/JUNE 2024

LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER PHOTO BY: KEN BOHN/SDZWA

Paul A. Baribault President and Chief Executive Officer Onward,

Securing the Future

In recognition of Endangered Species Day on May 17, we honor wildlife worldwide and the progress we’ve made to protect vulnerable species since San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s founding over 100 years ago. We work with partners and local communities to safeguard animals, plants, and the delicately balanced ecosystems we share, helping all life thrive for generations to come. Allies like you make it possible.

After 30 years of conservation efforts, the local Stephens’ kangaroo rat was “downlisted” from endangered to threatened— a conservation win.

Since 2012, we’ve helped recover the critically endangered Lord Howe Island stick insect, which was once thought to be extinct. These “tree lobsters” can now be seen at the San Diego Zoo’s Wildlife Explorers Basecamp— a first in North America.

It only takes one person to make a difference for wildlife. Conservation starts with you!

In 1987, only 27 California condors remained on Earth, and the species was extinct in native rangelands. Today nearly 600 soar across the skies.

Over 44,000 species worldwide are threatened with extinction.

2024 Board of Trustees

OFFICERS

Steven S. Simpson, Chair

Steven G. Tappan, Vice Chair

Rolf Benirschke, Vice Chair

Gary E. Knell, Treasurer

E. Jane Finley, Secretary

TRUSTEES

Kathleen Cain Carrithers

Javade Chaudhri

Adam Day

Clifford W. Hague

Bryan B. Min

Kenji Price ‘Aulani Wilhelm

TRUSTEES EMERITI

Berit N. Durler

Thompson Fetter

Richard B. Gulley

Robert B. Horsman

John M. Thornton

Executive Team

Paul A. Baribault

President and Chief Executive Officer

Shawn Dixon

Chief Operating Officer

David Franco

Chief Financial Officer

Erika Kohler

Executive Director, San Diego Zoo

Lisa Peterson

Executive Director, San Diego Zoo Safari Park

Nadine Lamberski, DVM, DACZM, DECZM (ZHM)

Chief Conservation and Wildlife Health Officer

Wendy Bulger

General Counsel

David Gillig

Chief Philanthropy Officer

Aida Rosa

Chief Human Resources Officer

David Miller

Chief Marketing Officer

SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 3

1 BY THE NUMBERS

44K+

30 27

PHOTOS BY: KEN BOHN/SDZWA

2012

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance (SDZWA)

protects and restores nature in eight conservation hubs on five continents. Below are recent discoveries and progress reports from around the world.

Javan Leopard Survey

In May 2023, our team and partners at SINTAS (SDZWA’s official partner organization in Indonesia) and the Ministry of Environment and Forestry of Indonesia completed a trail camera survey focused on detecting the presence of Javan leopards in Mount Ijen-Raung landscapes (East Java, Indonesia). This was the first-ever systematic trail camera survey of Javan leopards in these landscapes, and it supports the work of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry of Indonesia. We are repeating the survey in 2024, with twice the number of trail camera stations, in hopes of being able to produce the first-ever estimate of Javan leopard density for the area. With only 29 suitable landscapes remaining for these leopards in Java, it is critical that we understand how many cats live in this area so that we can help guide protections for these animals and their habitats.

Jaguar Coexistence Workshop

SDZWA collaborated with the regional government of Madre de Dios, Peru, to hold a three-day jaguar coexistence workshop. The workshop was focused on developing strategies to address humanjaguar conflicts and to foster coexistence between these big cats and communities living in the Peruvian Amazon so that these shared landscapes are safe for both people and wildlife. The workshop was led by our team in Peru, and over 40 participants from regional and national government agencies, nonprofits, and local communities attended. The strategies identified during the workshop will be implemented over the next five years in close collaboration with the Regional Forest and Wildlife Management Agency of Madre de Dios.

Botanical Expedition

In late 2023, SDZWA and our partners in Mexico and California organized the first all-women’s botanical expedition in the Baja California peninsula. The expedition was part of the Baja Rare program, our collaborative initiative to conserve rare and threatened plants in the cross-border region and more remote regions of the Baja California peninsula. It was also an opportunity to build capacity and promote inclusion and diversity in Baja California’s botanical community. During the expedition, 12 women spent a week searching for rare plants and documenting floristic diversity. The team successfully located some of the rarest plants in the region, and the data gathered supports new protected areas for biodiversity conservation. The expedition also included outreach to girls in local schools and helped change the face of regional fieldwork by supporting the participation of young women.

4 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MAY/JUNE 2024

FINDINGS PHOTOS: (TOP LEFT) MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND FORESTRY OF INDONESIA/SINTAS/SDZWA, (TOP RIGHT) KEN BOHN/SDZWA, (BOTTOM) SULA VANDERPLANK Not in Original Set Not in Original Set Not in Original Set Not in Original Set Not in Original Set Not in Original Set Not in Original Set Not in Original Set

How did you become interested in plant conservation?

In college, I knew I wanted to study ecology to both understand and conserve the natural world. The focus on plants was a gradual thing that seems inevitable in retrospect; ecology is all about relationships and interactions, and it becomes clear how central plants are in many ecosystems. Once you start focusing on plants, you realize how amazing they are. They deserve to be conserved, not just because they support us and many animals, but also because they’re incredible.

Do you have a favorite story from your time at San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance?

Early in my time here, I worked on a project in the Peruvian Amazon assessing the impact of harvesting fruit from the aguaje palm tree. It’s very important to wildlife and people in some rural villages. So we sponsored and presented a workshop on sustainable harvesting—how to safely climb trees to harvest fruit, and the benefits of climbing them over cutting them down. A few months later, we were back in the villages, and it was really cool to see our project’s influence on community behavior and witness how small communities can keep each other accountable in their commitments.

Christa Horn, M.S.

As a senior conservation program manager for San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, Christa oversees the preservation of plants native to San Diego County through seed banking, genetic analysis, propagation, restoration, and more. She works to save the critically endangered Torrey pine, examining the impact of drought and beetle infestations—and what we can do to help.

Q

What are the biggest challenges you face in your field, and how do you work to overcome them? Our biggest challenge is unpredictable weather. Our yearly goals for seed collecting depend on the plants being able to grow and produce seeds, and they need rain to do this. Keeping restored plants alive in a dry year is difficult, and along with our partners, we will hand water outplanted Torrey pines or other plants to help ensure they survive their first year.

How are plants interconnected with us, wildlife, and the ecosystems we all share?

What is the most unusual aspect of your job?

That I don’t really have a typical day. I might start early and hike around Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve to check seedlings or spend the day planning projects with partners. The variety of work our team conducts means I learn something new every day.

Q

Q Q

We depend on plants for so much: food, housing, clean water, supporting pollinators, providing food and shelter for wildlife—and we can’t forget oxygen! Plants aren’t always recognized for what they contribute when they’re there, but people certainly notice when they’re gone.

What do you see as the future of plant conservation?

Getting more native plants into public and private spaces, as well as traditional natural areas. Making restoration plantings more diverse in preserved areas, and helping people make habitat- and water-friendly landscaping. We also need to better understand how plants will adapt—or not be able to adapt—to climate change and what we can do to assist them if necessary.

MEET OUR TEAM

Q Q

PHOTO BY: KEN BOHN/SDZWA

6 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MAY/JUNE 2024

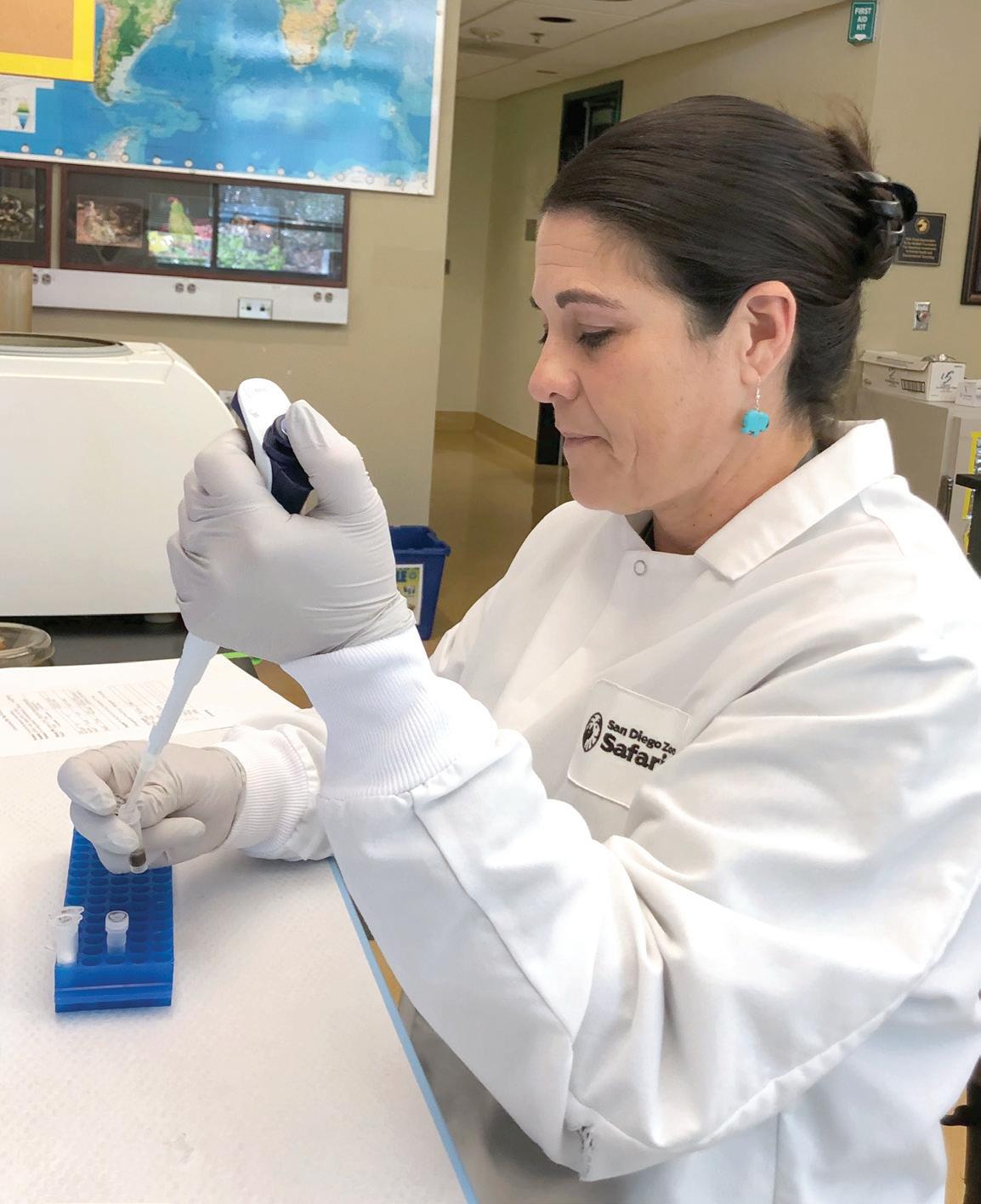

Genomic Insights for Koala Conservation and Health Tracing Retrovirus through the Generations

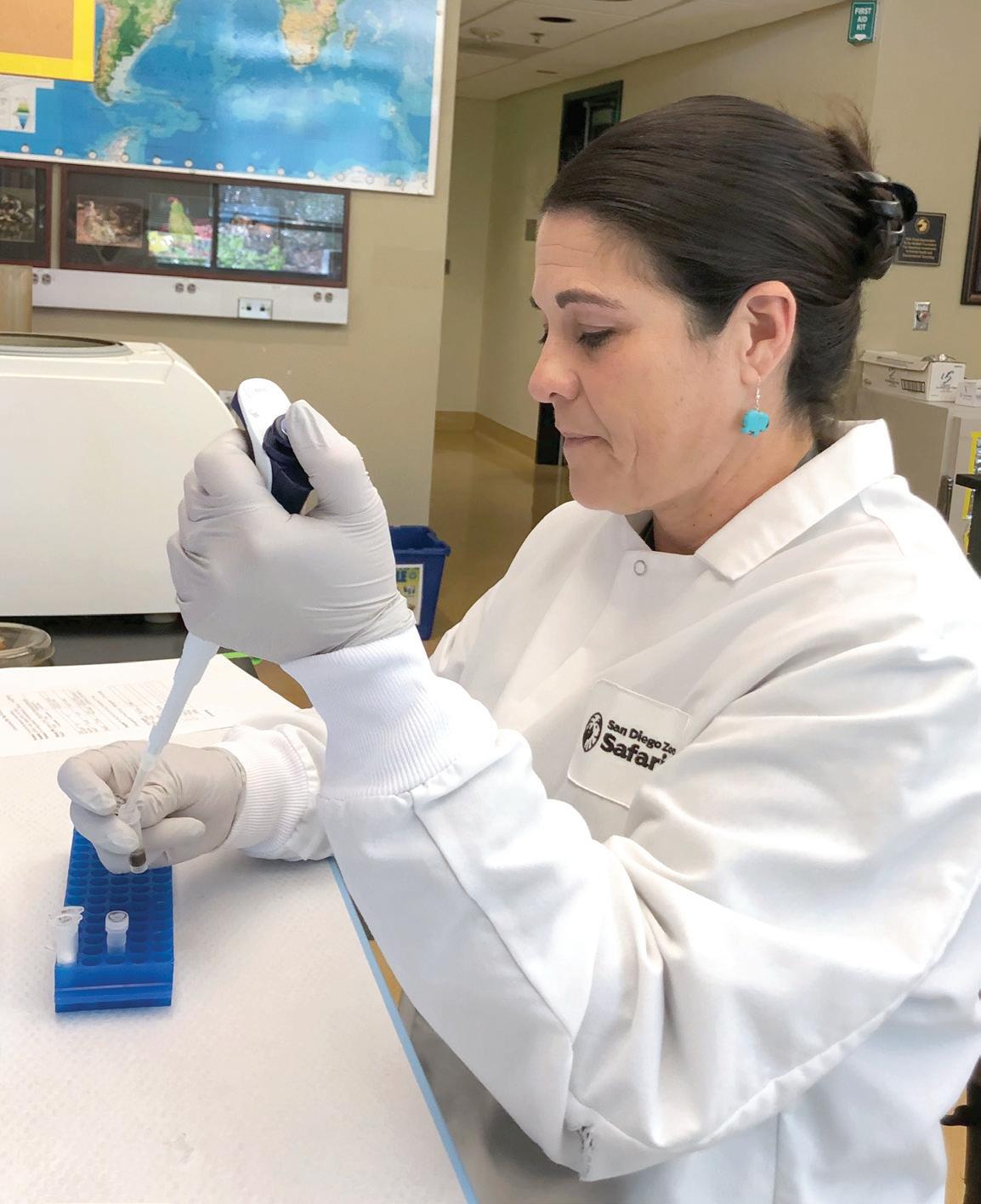

Cora Singleton, DVM, Dipl. ACZM, explains how scientists dive deep into the DNA of generations of San Diego Zoo koalas to expand our understanding of koala retrovirus.

Koala retrovirus (KoRV) is potentially a significant threat to koalas in the wild and in human care. Retroviruses are interesting because they insert (integrate) into the host cell’s genome as part of their life cycle. Retroviruses exist in both exogenous and endogenous forms. Exoge-

nous viruses can be spread from one person or animal to another, where they can cause disease by infecting the somatic cells (body cells) and use the host’s cell machinery to make more virus. Endogenous viruses are a special category of viruses that have infected the germ cells (egg or sperm) at some point in the past. By infecting germ cells, the inte-

grated virus DNA in the host genome is transferred from one generation to the next, becoming a permanent part of the host’s genome in all cells of the body. Many endogenous viruses can no longer replicate

The North American koala population consists of 50 koalas living at 9 different zoos.

8 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MAY/JUNE 2024 HOT TOPICS

independently or cause active viral infections. Most endogenous viruses are very old and are considered “fossils” of past viral infections. However, endogenous koala retroviruses have integrated into koala DNA only recently, evolutionarily speaking. The location in the host DNA where the KoRV integrates is important, as it leads to disruption of host gene function and predisposes koalas to certain diseases.

The prevalence of KoRV varies across populations. In the more northern Australian states of Queensland and New South Wales, the prevalence of infection is 100 percent, whereas in the southern states of Victoria and South Australia, the prevalence of infection can be as low as 30 percent. All koalas living in North American zoos have endogenous KoRV because the founder koalas came from Queensland in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Infection with KoRV is putatively associated with certain diseases in koalas. Cancers such as lymphoma and leukemia, as well as other bone marrow cancers and tumors of the bone, affect koalas in the wild and in human care. Also, KoRV infection may alter immune function, which may predispose koalas to other infectious diseases, such as a fungal infection called cryp-

tococcosis, and a bacterial infection called chlamydiosis, which causes widespread infertility in koalas in Australia, threatening already stressed koala populations facing drought, bush fires, and habitat loss.

The North American koala population consists of 50 koalas living at 9 different zoos. With 30 resident koalas, the San Diego Zoo cares for the largest colony of koalas outside of Australia and advises on the cooperative care of this iconic and specialized marsupial in North America. With decades of documented pedigrees, extensive health and husbandry data, and a large bank of biological samples, the North American koala population is viewed as extremely valuable for helping understand the biology and epidemiology of KoRV infection.

Molecular and genomic technologies are needed to study KoRV, but their application on a large scale has not been accessible until now. San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance has partnered with Illumina, a leading genomic sequencing technology company, and an international team of koala and KoRV experts at Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, The University of Sydney, the Australian Museum, and the University of Nottingham. Using whole genome sequencing of 91 living and deceased

koalas, the research team is investigating where KoRV integrates into the koala genome, how these integration sites are generated and inherited, and how the integration patterns are related to health outcomes. This partnership helps us clear a major technical hurdle in characterizing individual, familial, and population KoRV profiles, and will create the largest koala pedigree genomic database to date. Understanding how KoRV acts in the genome and how the North American koala population compares with Australian regional populations can help us make conservation management decisions (breeding, importation, translocation) that limit disease and optimize the health of koalas in their native range and under human care. This effort exemplifies how zoo populations can contribute meaningfully and directly to understanding and mitigating disease threats to koala conservation.

Cora Singleton, DVM, Dipl. ACZM, is a Board Certified Specialist in Zoological MedicineTM, and Senior Veterinarian at the Jennings Veterinary Medical Center.

SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 9

PHOTOS BY: (OPPOSITE PAGE) KEN BOHN/SDZWA, (TOP LEFT) SDZWA, (TOP RIGHT) KEN BOHN/SDZWA

10 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MAY/JUNE 2024

PHOTOS BY: (LEFT) KEN BOHN/SDZWA, (RIGHT)

LAURA VERO/SDZWA

To the Rescue Saving Wildlife, One Animal and Plant at a Time

BY PEGGY SCOTT

Three frightened young spider monkeys in a duffel bag at the U.S./Mexico border. A trio of orphaned mountain lion cubs in the San Pasqual Valley. Three baby cobras being smuggled in a Pringles can. The range of species is wide, and their circumstances are varied, but all these examples—and many more like them—have one thing in common: they were wildlife desperately in need of help, and San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance (SDZWA) experts came to the rescue.

Between the San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park, it’s estimated that SDZWA is called upon some 10 times a year to render aid to imperiled and confiscated wildlife often destined for the illegal pet trade or to be trafficked for folk medicine purposes.

We are part of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) and a platinum member of the Wildlife Trafficking Alliance (WTA), which is a partnership with AZA and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. SDZWA is also an active member of the Southern California Confiscations Network, a rapid response system created to help respond to wildlife confiscations in Southern California and is a working group of the WTA. SDZWA plays a key role in helping save animals and plants already caught in illegal operations—and preventing future cases.

The Network’s purpose is to create “a coalition of reputable and trusted animal care facilities that can provide immediate medical care and housing for wildlife that are trafficked through U.S. ports of entry, allowing wildlife law enforcement to concentrate on their core functions: the investigation and prosecution of criminals.”

When federal and state agencies encounter wildlife in crisis, SDZWA and its conservation partners are the organizations they call. And time is often of the essence.

The Clock Is Ticking

Because wildlife rescues are often emergency situations, every minute counts, explains Greg Vicino, vice president of wildlife care at the San Diego Zoo.

SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 11

“The first few hours are critical,” he says, likening the protocols to medical triage. “They’re sometimes in rough shape, needing water and food. We have to get them safe, stabilized, and treated—quickly.” Greg adds that it’s often a matter of hitting the ground running, as care teams sometimes only receive a few hours’ notice of a new case needing their attention. And both the Zoo and Safari Park need to be ready.

Kristi Burtis, D.M., is vice president of wildlife care at the Safari Park, and has seen firsthand how dire a rescue situation can be. “Three very young spider monkeys were discovered at the [U.S./Mexico] border crossing in a duffel bag,” Kristi recalls. “They were clinging to each other—and after observing for a moment, I moved the bag close to a large crate with blankets, towels, a warm plush animal, food, and water.” Kristi wanted to make the situation as soothing as possible and acted accordingly.

“Two of the monkeys had diapers on them, so I immediately removed them and placed the monkeys in the crate.” Kristi says. “They were vocal at the start of our trip, but soon fell asleep for about an hour and a half. When they awoke, they seemed more comfortable and started moving around the crate and demonstrating some natural behaviors like climbing.”

Proceed with Caution

The monkey trio was destined for a temporary stay at the Safari Park, during which they could wean and adapt to human care. When rescue situations like this involve transfer to SDZWA facilities, there are protocols that must be followed, notes Hendrik Nollens, DVM, MSc, Ph.D., vice president of wildlife health for SDZWA. “These are animals that need our help, but we must be careful,” he says. “Because they are of unknown origin, we don’t have their medical background, and have to consider the health of wildlife already in our care. That’s where our quarantine procedures come in.”

When it comes to treating new “patients” on site, Hendrik explains that the procedures can vary depending not only on the condition of the incoming wildlife, but the species as well. “Primates require specialized care, and the Centers for Disease Control must be notified,” he says. “We have to get a team ready; personal protective equipment is worn out of precaution. It can be difficult, but we are uniquely qualified.”

Hendrik notes there are instances where the rescued wildlife cannot be returned to its native range, either due to age, viability, injury, or because we don’t know which part of their home range they originated from. When this happens, SDZWA is often called upon to give those animals a home. “As a partner in our Conservation Hubs, we support them however we can, whether that’s in Kenya or Peru or here [in the Southwest]. We take the responsibility seriously.”

In the case of the mountain lion cubs, finding the very

Rendering

aid: SDZWA wildlife care specialists and veterinary team members often have very little notice before they are called upon to rescue and treat imperiled wildlife. The physical condition of confiscated animals and plants can often require immediate treatment for such ailments as dehydration and malnutrition. Some wildlife that come into our care end up staying, such as with the lion cub trio.

DID YOU KNOW?

Spider monkey troops are matriarchal; females are the leaders.

12 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MAY/JUNE 2024

young cats was only the first step in their recovery. The first cub was located shortly after the mother was killed while predating on livestock, and the second was found the next day, but it was a week before the third cub was located and brought into managed care. “They were dehydrated, but had no other health issues,” Kristi says, noting the cubs now live at the Safari Park and are doing well under a care program that recognizes their nocturnal nature. “They are not on habitat when there is human presence,” she explains. “They might be seen during a special early morning or evening tour when the cubs are ready, but otherwise, their feeding and care sessions are between 5 p.m. and 8 a.m.”

The Root of the Problem

While stories of rescued baby cats and confiscated monkeys may garner the lion’s share of media attention, there are few wildlife species that aren’t trafficked for one reason or another. Birds are trafficked globally, and some plants are hot commodities, too. As director of horticulture for the Safari Park, Raj Brown has seen how big the problem can grow. “The Safari Park is a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Plant Rescue Center for cactus, succulents, and cycads,” Raj explains. “And in June 2022, we received an 830-pound shipment of illegally trafficked cactus and succulent plant material. Our horticulture

SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 13

PHOTOS BY: (TOP) GUMMYBONE/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS, (BOTTOM RIGHT) LAURA VERO/SDZWA, (BOTTOM LEFT) KEN BOHN/SDZWA

team worked diligently for days, unwrapping the dank and musty packages in order to sort, identify, and catalogue each plant.” Raj goes on to describe how painstaking the work was, noting that some of the plants were so unique and tiny that the teams were unable to identify them until flowers emerged months later. He calls the outcome a success, adding that “we were able to salvage the majority of the seized plants, providing them homes in our greenhouse facilities, nurseries, and gardens.”

Greg estimates that 30 percent of wildlife trafficking involves reptiles. Kim Gray, curator of herpetology and ichthyology at the San Diego Zoo, also serves on the board of the Turtle Survival Alliance. She points out the location of our headquarters—San Diego—makes SDZWA uniquely situated to help fight wildlife trafficking. “Trafficked animals are usually on their way into or out of the country, and areas close to borders and busy ports are where they are often found,” Kim explains. She notes the U.S. is particularly attractive for those who trade in certain types of wildlife. “The U.S. has the largest diversity in species of turtles and tortoises anywhere,” Kim says. And while other countries are often cited as the last stop for trafficked wildlife, the evidence tells Kim that some of the problem hits closer to home. “The U.S. is the number two consumer of wildlife components,” she says. “It’s a huge market, even here in California.”

In June 2022, we received an 830-pound shipment of illegally trafficked cactus and succulent plant material.

Hendrik says, acknowledging that the money involved is a huge incentive for the sellers. But the buyers?

“People need to ask if is this species is suitable as a pet,” he advises, noting that it can be impossible for the general public to differentiate between a trafficked animal and an animal that comes from a legal, reputable program.

The bottom line for the motivating factor behind wildlife trafficking is exactly that—the bottom line. Regarding the financial impact of this illicit commerce, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime estimates wildlife trafficking generates from $8 billion to $10 billion a year.

How to Help

As complicated as the wildlife trafficking issue is, there are things everyone can do to help combat it. While having an exotic pet might seem enticing, it’s not a good idea,

“People don’t realize how big a problem wildlife trafficking is,” Greg says. “If you see something, say something.”

A Brighter Future

For some wildlife at least, their rescue story has a happy ending. The infant spider monkeys saved at the border—a male and two females—are currently under the care of the experts at the Safari Park. Their group is likely to grow, too. “We have received two spider monkeys from other AZA facilities, so after a quarantine period and socialization period, it’s likely the five will become a new troop,” Kristi says. “A new beginning for them.”

The monkeys aren’t the only species settling into a new home. “The mountain lion cubs are making progress, both as a trio and individually. They have explored all of their new habitat and are learning to shift between areas, participate in training sessions, and other behaviors involved with their care,” Kristi says. “They’re climbing and playing, and their personalities are becoming more obvious, and the two boys are more mellow but the first to explore something new, and the female cub is a protective mountain lion to the core!”

Kim’s department has welcomed newcomers as well. “The three young king cobras found in the [Pringles] chip can are healthy and living here at the San Diego Zoo,” she says. “One of the females is part of a breeding pair, so that’s good for the species.”

These kinds of results—a positive outcome for wildlife conservation—are the goal for all SDZWA efforts, and this work depends on success at each step. “Rescue starts with freeing wildlife from danger,” Kristi says. “And then it’s about managing for the next step, for tomorrow.”

PHOTO BY:

14 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MAY/JUNE 2024

SPRATT/SDZWA

TAMMY

BY:

16 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MAY/JUNE 2024

PHOTO

SDZWA

NO BIRD IS AN ISLAND

Protecting the San Clemente Loggerhead Shrike

BY SARAH SHELDON AND JAELEAN CARRERO

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance (SDZWA) is part of a collaborative, multiorganization recovery program dedicated to restoring habitat and species on San Clemente Island, one of the Channel Islands off the coast of California. Although there are several listed species on the island, SDZWA’s efforts are focused on one in particular—the San Clemente loggerhead shrike.

The San Clemente loggerhead shrike is an endangered, medium-size, predatory songbird endemic to San Clemente Island, a Navy installation and vital training ground for the military. In the 1990s, the shrike population dropped to as few as 14 individual birds due to historic landscape-level changes to the island, as it was used for ranching prior to its transfer to the Department of Defense in 1934—sustaining over 100 years of overgrazing by livestock and feral ungulates, the latter of which were removed by the Navy. In response, the Navy initiated the shrike recovery program and established a shrike working group to protect the population against the threat of extinction and restore it to historical levels. This working group continues to this day and includes SDZWA.

Within the working group, SDZWA’s San Clemente Loggerhead Shrike Conservation Breeding Program has

three main functions: provide juveniles and adults for release to help bolster the native population; maintain an assurance population to act as a genetic reservoir for the entire population on the island; and provide care for salvaged or injured eggs or birds. Given the long history of the project, this purpose is accomplished by on-island program staff with the aid of other departments throughout SDZWA. With 34 years of experience, SDZWA and our partners have worked hard to create a robust and dynamic toolkit of conservation techniques to aid in the shrike’s recovery.

Getting Established on the Island

In the early history of the program, the focus was on artificial incubation of eggs, handrearing of chicks, and figuring out the basics of shrike husbandry and breeding. But once those protocols were established, the program quickly transitioned to establishing

SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 17

Release readiness:

It is never too early to start preparing shrikes for release. Around day 12, nestlings are briefly removed from the nest to receive a unique colored leg band combination that allows them to be identified once released. They also receive the first in a series of vaccinations to protect them from disease.

techniques that would maximize both the quantity and quality of shrikes available for release.

In the early 2000s the program switched its focus to parent rearing, and that remains a key factor to the success of the program and improved survival of individuals post-release. The conservation breeding flock is located on San Clemente Island, which ensures all birds are acclimated to their native environment. All birds in the flock are fed live prey, which encourages natural behaviors, prepares individuals for release, and improves the health and the welfare of the birds. Native prey, including insects, mice, and lizards, are also provided by staff to guarantee the birds can recognize and handle food items available in the native range. Native shrubs are used for perching, cache sites, and potential nesting sites, and native plants are collected and provided for nesting material at the start of each breeding season.

Every effort is made by the conservation breeding program to mimic the shrike’s natural history and conditions found in its native range, including syncing the phenology (cyclical and seasonal natural phenomena) and behaviors of the shrikes under our care to promote natural breeding behaviors. In many shrike species, the males will larder, or store, their food items by caching them on branches as a signal to the females of their suitability as mates and parents—and our males are no different. While the timing of breeding varies annually, it usually occurs between March and July. Program staff manage the breeding of the flock to maximize genetic diversity in the entire population. In the conservation breeding flock, care staff conduct behavioral observations of the birds to assess behavioral compatibility of potential mates; oversee the progress of breeding activities, like nest building; and assess the foraging and flight skills of weaned juveniles destined for release.

With the right conditions established

in the aviaries, and under the watchful eyes of care staff, parent shrikes are able to raise their young to independence without the need for artificial incubation and handrearing techniques. Though release and breeding practices can vary from year to year, we usually release between 25 and 35 juveniles annually.

Island Forces

Over its history, the recovery program has had many successes using the tools available to us. In 2013, there were 70 breeding pairs in their native habitat, and every native shrike had some portion of their ancestry that could be traced back to the conservation breeding flock. Despite the efforts of the working group partners and these successes, the shrike population has dipped in recent years to as few as 22 pairs. This decline is suspected to be largely tied to the El Niño and La Niña weather cycle; drought years cause a decline in prey

abundance. Throughout the long history of the shrike recovery program, the working group has continued to place an emphasis on adaptability and innovation when it comes to our conservation practices— dynamic threats necessitate dynamic responses. We are currently focusing on creating new tools and adaptive response plans to bolster the native flock and continue to improve the quantity and quality of release shrikes.

For example, staff can artificially incubate, hatch, and hand-rear individuals when needed, but have also pioneered fostering techniques using active breeding pairs that can raise those individuals instead. These pairs have been very successful when presented with salvaged eggs or chicks that need continuous care. Post-release survival of hand-reared shrikes is 20 percent less than that of native range-born individuals, whereas survival of parent-reared shrikes is comparable to

18 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MAY/JUNE 2024

BY: (LEFT) SDZWA, (RIGHT) TAMMY SPRATT/SDZWA

PHOTOS

DID YOU KNOW?

One of the San Clemente loggerhead shrike’s nicknames is “The Butcher Bird.”

their native counterparts, making fostering another key strategy in the toolbox. Care staff create behavioral profiles of our breeding pairs so we know who is or who will make good foster parents, and we are able to augment clutches, exchange clutches, and even swap eggs for chicks with a 100-percent success rate. These past few years, we have also been working with the Wildlife Welfare and Wildlife Health teams to get genetically valuable birds that have never bred to contribute to the population. With additional calcium-rich supplements and eliciting improved nest building behaviors by varying the presentation of nesting materials in aviaries, we have more individual shrikes contributing to the breeding effort.

Insular Isn’t Isolated

In 2022, the partners within the shrike working group and representatives from many SDZWA departments met to

brainstorm additional measures to help the recovery of these birds. The 2023 and 2024 breeding seasons were our flagship years for implementing these new ideas. We’ve started planting native plants around and within the aviaries that are specifically meant to attract insects that are a significant source of food for the native shrike population, especially during drought years. With the recovery of other species on the island, including peregrine falcons that will predate shrikes, we’ve also begun implementing predator avoidance training, making sure that all juvenile shrikes destined for release are exposed to a falcon replica before they reach independence to allow the parent to model the appropriate duck-into-cover technique. Last year, with a wet winter and high prey abundance forecasted, care staff were also able to double the number of shrikes available for release with a total of 55 birds raised to independence, the most ever for

this program. We achieved these numbers by reintroducing pairs and allowing them to have a second clutch after the first set reached independence. Twice as many chicks meant twice as much work, but our team and our partners rose to the challenge and are planning on using the same technique again this year. It is impossible to predict what the 2024 breeding season will be like for the flock in the native range, but we can be sure that the conservation breeding team is ready for another banner year for the conservation breeding flock, which can only be a boon for the entire population.

Sarah Sheldon is a research coordinator for SDZWA’s San Clemente Loggerhead Shrike Conservation Breeding Program. Jaelean Carrero is a Recovery Ecology conservation program manager.

SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 19

Waiting in the Wings

Exploring the Safari Park’s Newest Aviary

BY PEGGY SCOTT PHOTOGRAPHY BY KEN BOHN

For many birds at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park, it’s looking a lot like rain— well, rainforest, actually—and these winged wonders are taking to their new habitat like a duck to water. And while not all its birds (or greenery) are native to rainforest habitats, the Rainforest Aviary has become a special little world of its own, with species

coexisting in harmony.

Located adjacent to Flightline Plaza on Nairobi Walk, the Rainforest Aviary inhabits space once occupied by Lorikeet Landing and is now home to numerous avian species. “As you enter the aviary, it just has a rainforest feel to it,” explains Andrew Stehly, curator of birds at the Safari Park. “There are sprinklers on top of the aviary

20 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MAY/JUNE 2024

Bird watching: The Rainforest Aviary (page 20) brings together many species, including (page 21, clockwise from top) the dramatically marked Inca tern, the eye-catching Madagascar crested ibis, and the beautiful Bali myna.

that turn on multiple times a day during the warmer months. The birds love it, and it really looks like a rainforest.”

Setting the Mood

The feeling of immersion begins even before entering the aviary. “With their large canopies and massive trunks, the large specimen trees surrounding the aviary create the rainforest experience,” says John Musser, horticulture manager

at the Safari Park. From the glossy-leafed Chinese mahogany and leguminous tropical ice cream bean tree to the hardy tulipwood tree and yellow-flowered sweetshade, the beauty of the aviary isn’t limited to just the feathered inhabitants. The elegant leaves of the evergreen long-leafed yellowwood are particularly attractive to birds, and the lush fern pine thrives in warm weather. The fragrant mock orange beckons with its sweet scent,

and the umbu tree—the mango’s massive cousin—sits at the aviary exit, waiting to “wow” guests.

On the Bill

Inside the Rainforest Aviary, several ficus trees serve as broad, shady perches and homes for the birds. As guests walk through the aviary, various bird species may cross their path, either on the ground or above. With its lyrical call, it’s

SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 21

DID YOU KNOW?

The spur-winged lapwing stands about one foot tall.

Avian works of art: (Clockwise from page 22) The spurwinged lapwing is a wading bird. The African spoonbill’s round-ended beak is its most notable feature. The endangered scaly-sided merganser has a thin, serrated red bill. The red-crested turaco’s call sounds like a monkey. The moustache-like white feathers on each side of the Inca terns’ beak signal maturity in males and females. Purple-tailed imperial pigeons are native to New Guinea.

22 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MAY/JUNE 2024

possible you’ll hear the white-crested laughingthrush before you see it, but once you do, there’s no mistaking its black eye mask. And while rare in North American zoos, Congo peafowl stroll proudly through the aviary, which is also home to midsize, red-eyed metallic starlings; diminutive but brightly marked red-breasted geese; and the plump, shortwinged, purple-tailed imperial pigeon.

Each walk through the Rainforest Aviary is a unique opportunity. On one visit, you may happen upon Madagascar crested ibises as they perform their elaborate courtship display. Inca terns might dive into the pool as they try to catch fish. The aviary’s pool is also popular with African pygmy and red-breasted geese, as well as the brightly billed scaly-sided mergansers. Keep an eye out for the African spoonbill—the long legs and round-ended beak are telltale characteristics. Another wading bird fond of the pond is the spur-winged lapwing, which can be identified by their coloration—brown back feathers with white necks and bellies and black legs. And is that a monkey you hear? Nope—that would be the frugivorous red-crested turaco making its presence known with its signature 10-second, whoop-and-croak call. Should a beautiful, snow-white bird with black-tipped tail feathers and wings alight nearby, that’s a Bali myna. Blue eye patches are another clue to this critically endangered bird’s identity.

Between the wide array of bird species and types of plant life here, the Rainforest Aviary has a wealth of wildlife to be appreciated. Even those who find themselves there frequently see something new every time. “Wandering into the lush Rainforest Aviary, you encounter busily chattering birds and breathe in earthy aromas,” says Raj Brown, director of horticulture at the Safari Park.

“You see sinewy ficus trees, and as you leave the aviary you are met by one of my favorite trees, the huge umbu tree. Rainforest Aviary is such an immersive and unique experience—you don’t want to miss it.”

SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 23

FROM THE TOP

CAN YOU SEE ME NOW?

CAN YOU SEE ME NOW?

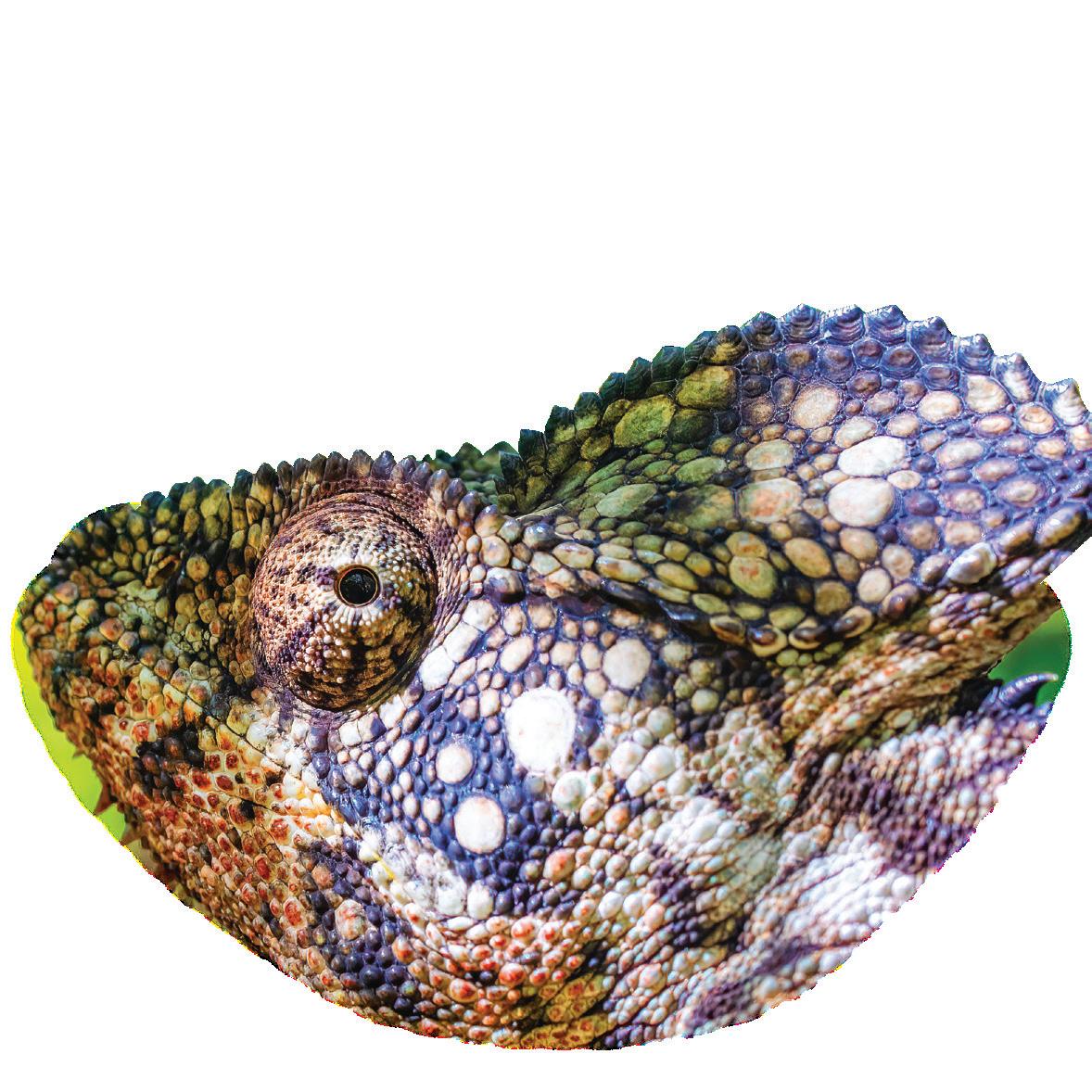

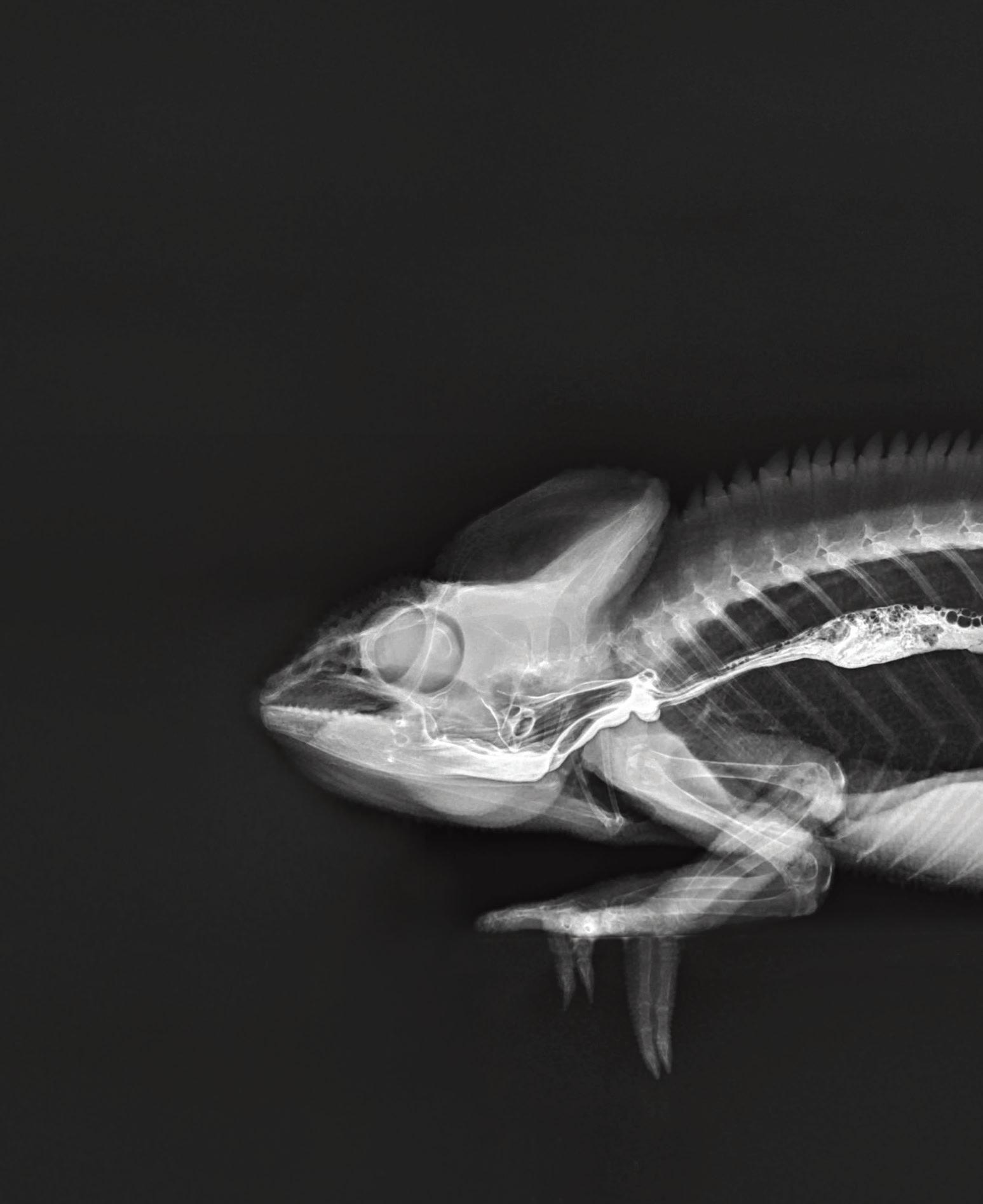

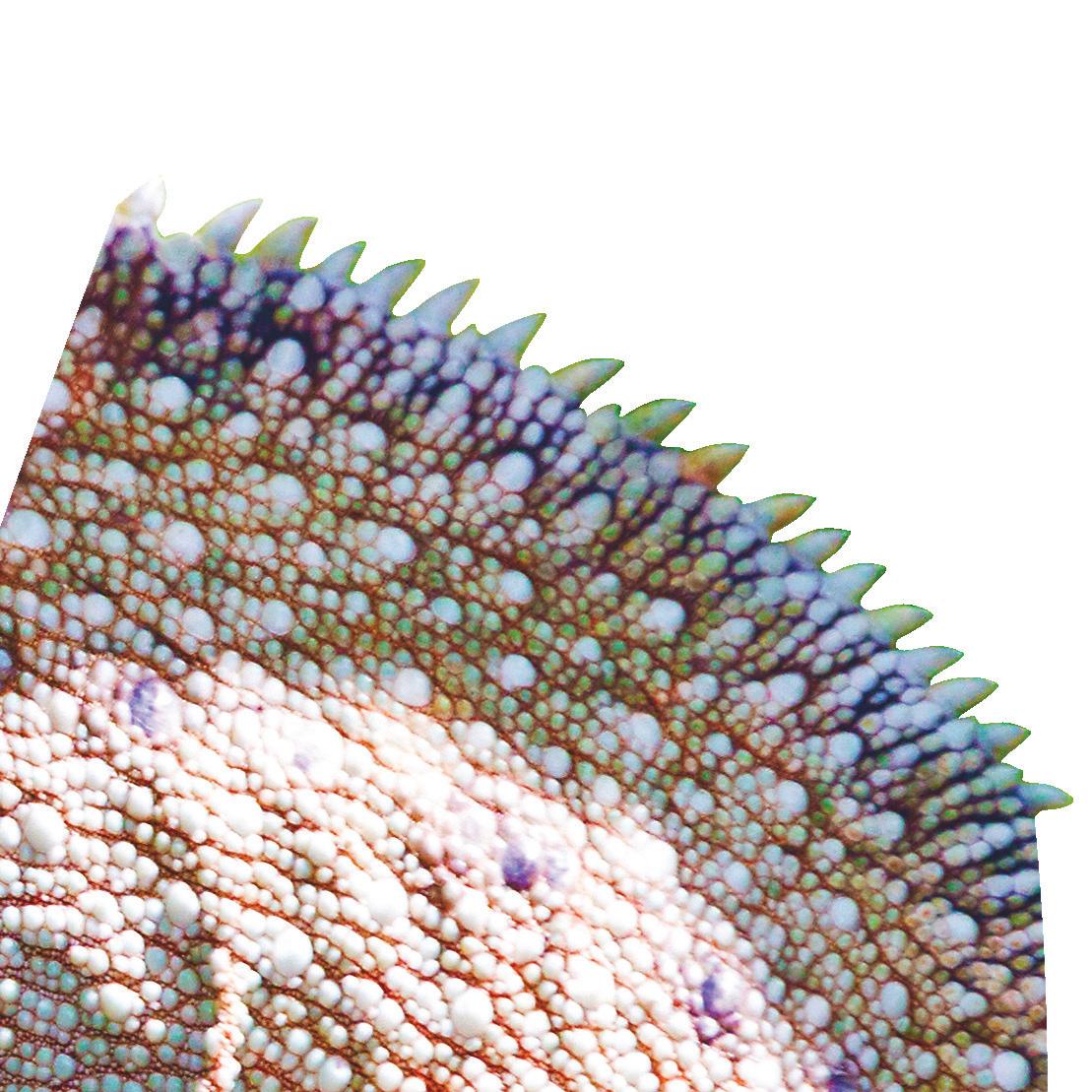

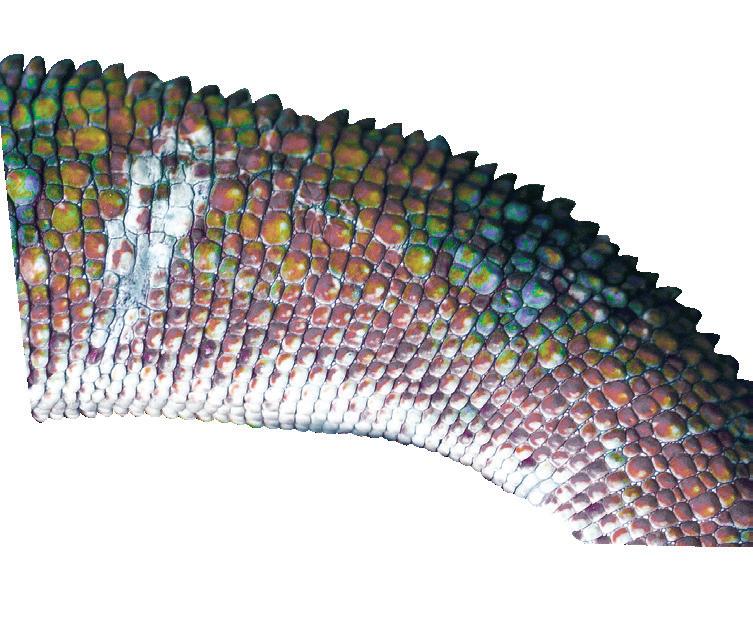

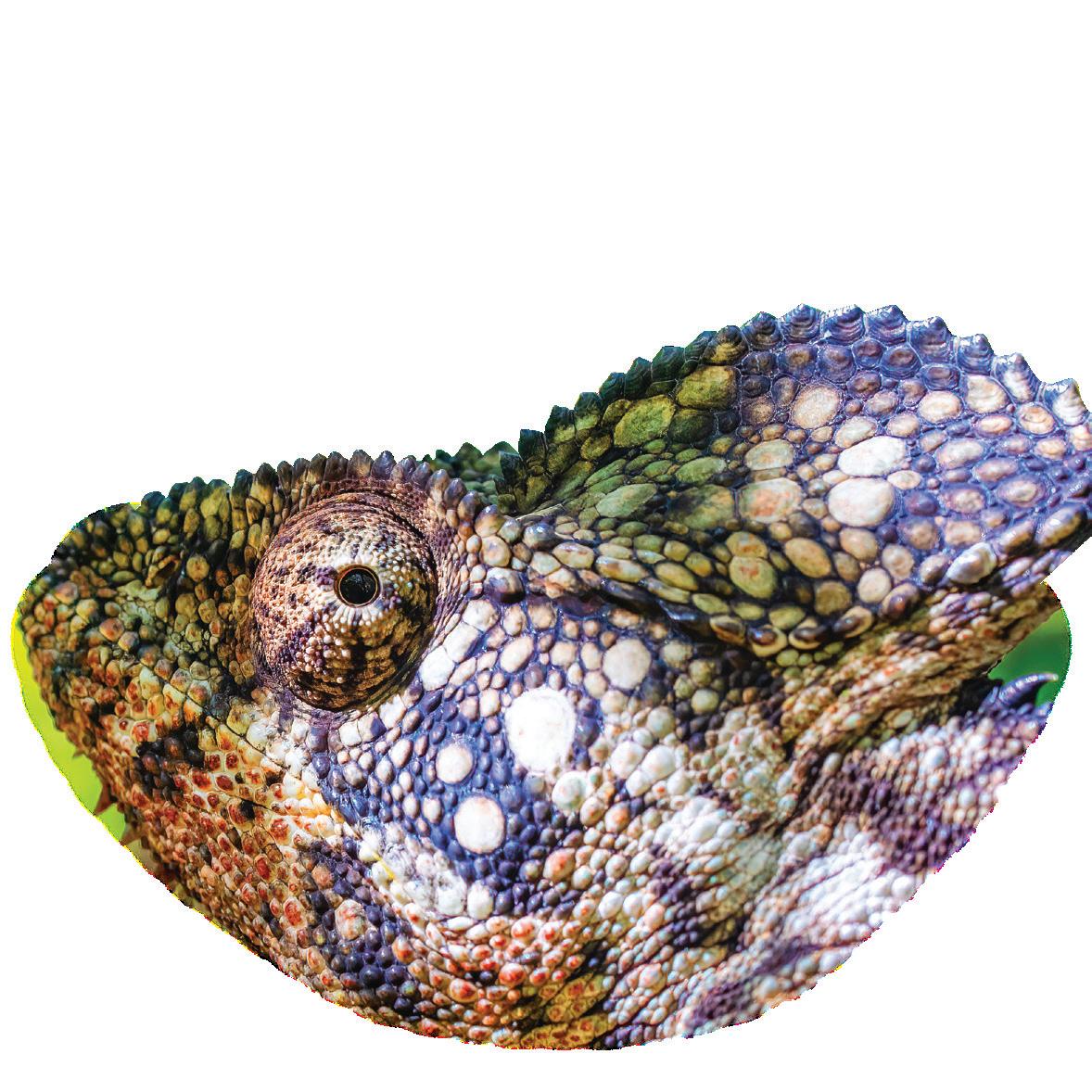

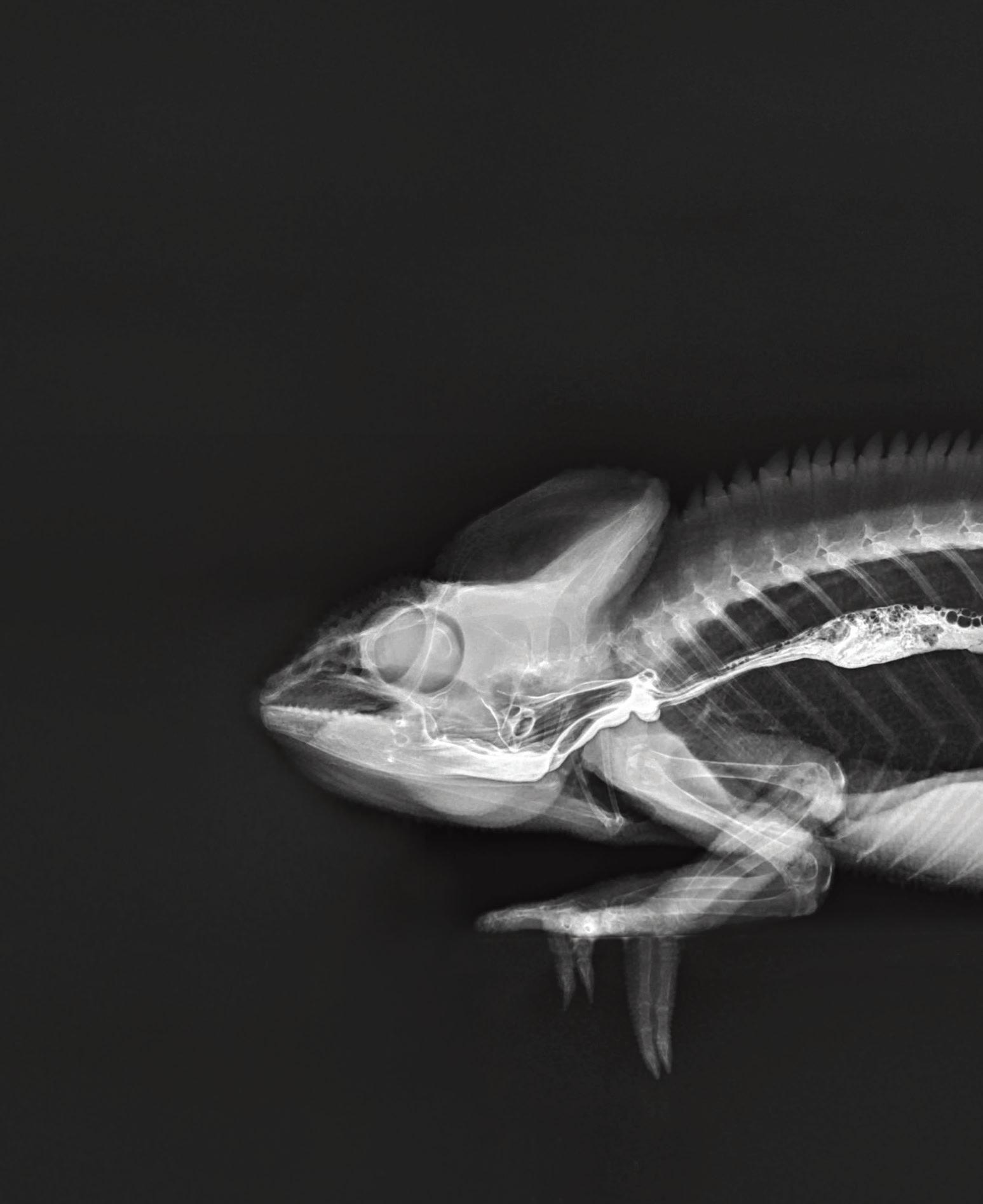

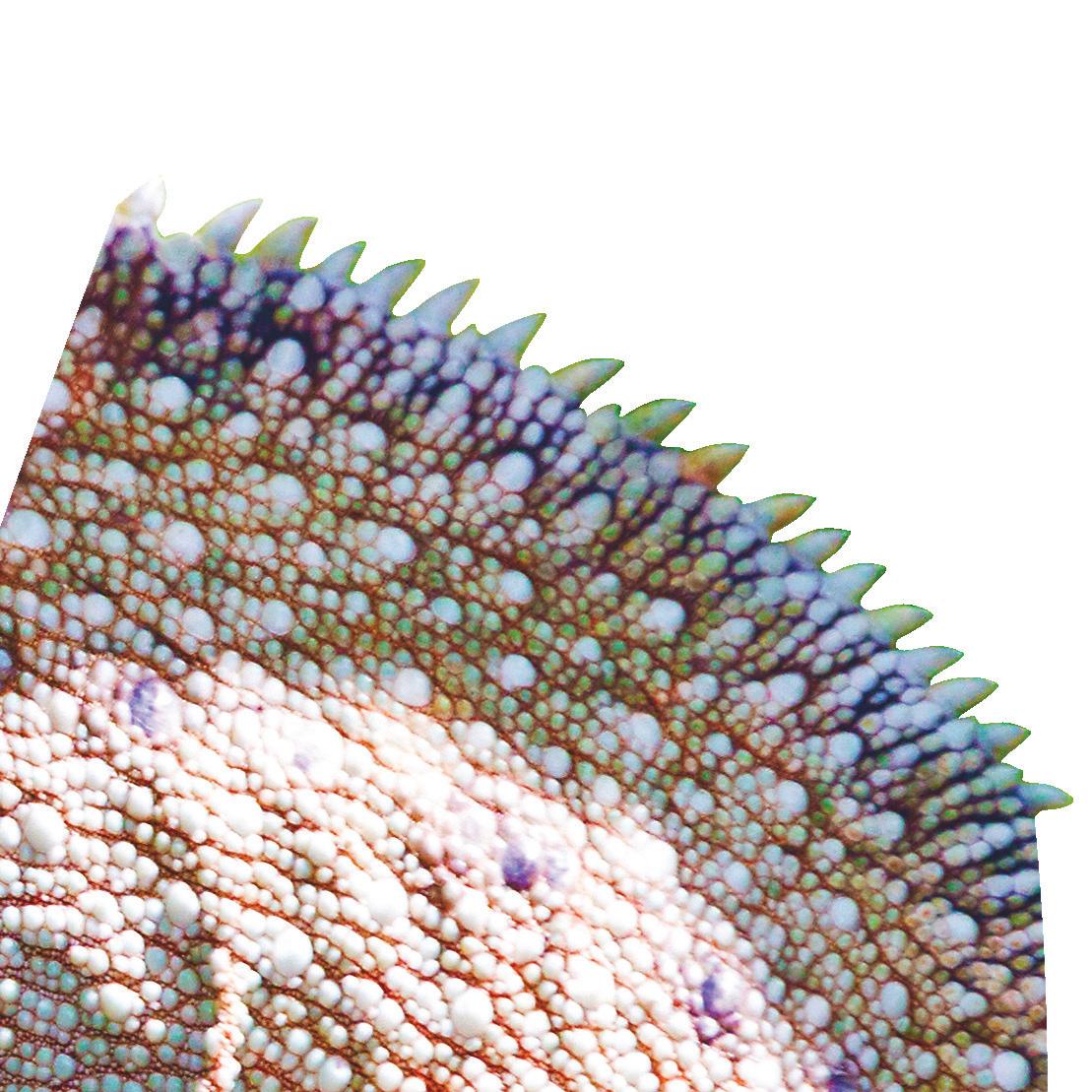

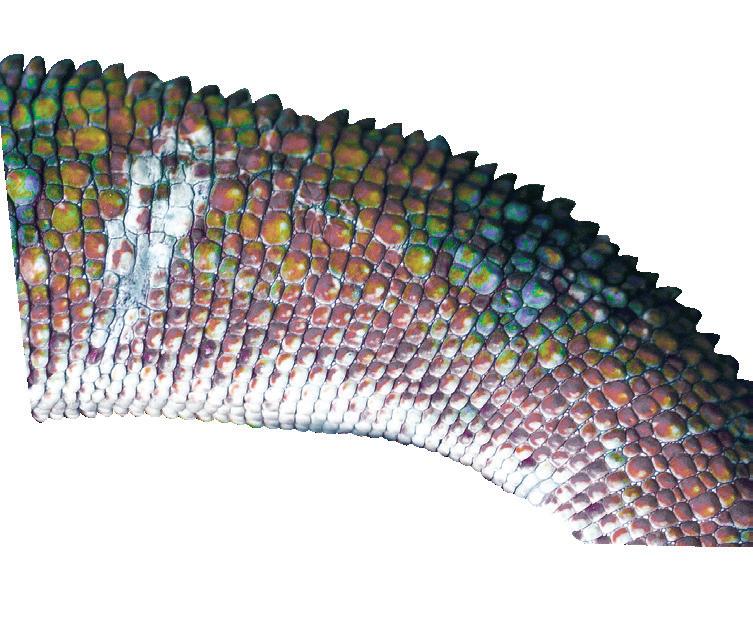

Found mostly in Madagascar, Africa, and parts of Asia and southern Europe, chameleons are known for their ability to change skin color. But this lizard’s astonishing adaptations are more than skin deep. Through radiography, we can take a deeper look at the physical characteristics that set the 200+ species of chameleons apart.

By Peggy Scott

THE “EYES” HAVE IT

A chameleon can rotate and focus its eyes separately to look at two different objects at the same time! it a full 360-degree view around its body.

LICKETY-SPLIT

A special group of muscles allows a chameleon to snap its tongue out fast—from 0 to 60 mph in 1/100th of a second! The tip of their tongue is coated with sticky mucus that helps trap its prey, such as crickets, grasshoppers, locusts, and other insects. Some larger chameleons also eat small birds or even other lizards.

A chameleon’s hood evolved to serve two main purposes. First, the hood helps chameleons collect water. Male chameleons typically have larger, pointier hoods than females, and they use theirs to look bigger to other males they might have to fight in order to gain access to females.

24 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MAY/JUNE 2024 VISUALIZE IT

360

GETTING THE SKINNY

Chameleons have four layers of skin:

The epidermis, a protective outer layer.

The nether layer, which solely reflects white. 1 2 3 4

The chromatophore layer, which contains yellow and red pigments.

The melanophore layer, which has dark pigment melanin and can create brown and black colors or reflect blue.

Z IS FOR ZYGODACTYLOUS

SIZING THEM UP

The longest chameleon is the Oustalet’s; it reaches 23 inches (60 centimeters).

The shortest chameleon is the pygmy leaf at 0.9 inches (2.54 centimeters) long.

HOLD ON!

The chameleon’s prehensile tail helps with their arboreal life— it can wrap around tree branches while climbing. But unlike some lizards, if a chameleon’s

Chameleons are the only animals with completely horizontal feet and toes that stick straight out to either side. A chameleon’s five toes are modified into groups. On the forefoot, the two outside toes are joined to form one group, and the three inside toes form another; the hind foot has the opposite arrangement. This allows them to grasp branches just like our fingers and thumbs can grip objects.

SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 25

PHOTOS BY: ARTUSH/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES, DENNISVDW/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS, DENNISVDW/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS, MDOUBRAVA/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

May & June EVENTS

SAN DIEGO ZOO

MAY 25–SEPTEMBER 2

May and June Hours

For San Diego Zoo and Safari Park operating hours, visit sdzwa.org

MAY 25–SEPTEMBER 2

Nighttime Zoo

sdzwa.org

619-231-1515

*Exceptions apply. Programs and dates are subject to changes—please check our website for the latest information and requirements for visiting.

(Z) = San Diego Zoo

(P) = Safari Park

As the sun goes down, your wild adventure is only just beginning! Join us this summer to rock and roar until 9 p.m. with live music, entertainment, and performances. Stay late with us for all the family fun and excitement of Nighttime Zoo! For member preview, see For Members. (Z)

MAY 17 & JUNE 21

Plant Day and Orchid Odyssey

On these special days, guests can take a rare look inside the Zoo’s Orchid House (and visit the plant sale) from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Discover more about the 700,000 plants we care for when you hop on the Botanical Bus Tour at 11 a.m., and check out the Carnivorous Plant Greenhouse from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. Free with admission; no reservations needed. (Z)

FOR MEMBERS

MAY 12 & JUNE 9

Member Exclusive Early Hours

Rise and shine with the sights and sounds of the San Diego Zoo. One Sunday each month, members can enter the parks one hour before the general public. To join us, simply present your qualifying membership card at the main entrance beginning at 8 a.m. (Z)

MAY 24

Member Preview

Kick off your summer with an exciting sneak peek into Nighttime Zoo—exclusively for members. (Z)

EVERY DAY Wild Perks SM San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance members are eligible for Wild Perks SM . Show your membership card each time you make an on-grounds purchase and save up to 20%, depending on your membership level. Some exclusions apply; for details, visit sdzwa.org/ membership/wild-perks (Z)

26 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MAY/JUNE 2024

SAFARI PARK

MAY 18–19

Wild Weekend: Australian Forest

Learn more about the wildlife you help save, protect, and care for through our Australian Forest Conservation Hub with special activities, wildlife care specialist talks, and more. (P)

OFFERED DAILY

Journey into the Wild

Join our wildlife care specialist team as they introduce you to wildlife ambassadors representing conservation work in our Amazonia Conservation Hub in South America as well as right here in the Southwest. This conservation presentation begins at 2 p.m. daily at Benbough Amphitheater. (P)

THROUGH MAY 12

Spring Safari featuring Butterfly Jungle

Explore a vibrant rainforest aviary as countless colorful butterflies flutter above and around you in Hidden Jungle (Butterfly Jungle experience purchase required), then discover a wide array of spring activities and entertainment throughout the Safari Park (free with admission or membership). For full details, visit sdzsafaripark.org. (P)

MAY 12 & JUNE 9

Member Exclusive Early Hours Rise and shine with the sights and sounds of the Safari Park. One Sunday each month, members can enter the parks one hour before the general public. To join us, simply present your qualifying membership card at the main entrance beginning at 8 a.m. (P)

EVERY DAY

Wild Perks SM

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance members are eligible for Wild Perks SM . Show your membership card each time you make an on-grounds purchase and save up to 20%, depending on your membership level. Some exclusions apply; for details, visit sdzwa.org/membership/ wild-perks (P) FOR

SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 27

MEMBERS

Visit the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Explorers website to find out about these and other animals, plus videos, crafts, stories, games, and more! SDZWildlifeExplorers.org

Who is ready to dig in?

There’s a special little bird here in San Diego County, and to find it you don’t look up, you look down—and into a burrow! San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance is working to help save the burrowing owl and its habitat. Our conservation team uses observation skills to study burrowing owls’ nesting habits, threats from predators, habitat needs, and more. Let’s practice those skills right now—if you look at the words below, how many words can you make with those letters? We’ve given you three to get started.

B U R R O W I N G O W L

Row Wing Brown

LAST LOOK

Bo, an African lion, has become the “mane” attraction at the Safari Park’s Lion Camp habitat. It is hoped that he will eventually lead his own pride when he is introduced to the three female lions who reside at Lion Camp—Malika, Zuri, and Amira. San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance supports lion conservation in Kenya, collaborating with community organizations Ewaso Lions and Northern Rangelands Trust. Photographed by Ken Bohn.

SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 29

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance

PO Box 120551, San Diego, CA 92112

You are our greatest ally as we work together to help protect and save wildlife. When you become a monthly donor, your recurring gift fuels critical conservation efforts around the globe. Our monthly donors are the heartbeat of everything we do at San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, and every sustaining gift adds up to make lasting impact for wildlife in need. You can inspire hope for wildlife worldwide and make a brighter future possible. Become a Monthly Donor today at sdzwa.org/hero.

JOURNAL You Can

Wildlife.

Help Save