The Utopian Palimpsest

1

IMAGINING COLLABORATIVE WORLD

First Supervisor I Prof. Ivan Kucina Second Supervisor I Prof. Dulmini Perera Name I Shanzeh Usman Matriculation Number I 4069066

DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that this work is my own work and all the sources of materials used for this project have been fully acknowledged. This work has not been previously submitted, in entirety or in part, to obtain academic qualifications in any other university.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Thank you to Ivan Kucina for pushing me to explore new horizons, and Dulmini Perera for sharing her oceans of knowledge. To mama, for her unconditional love and prayers. To baba, for clutching my hand during my first stroll in the Walled City. To my Ustaad, Qasim Ahmed. To my people, Larissa, Shiza, Minahil, Jawwad, Sofia, and Aleezeh. To my support system, Jannat and Thomas. Thank you.

CONTENTS ABSTRACT 13 LAHORE; THE ANCIENT WHORE

17

I AM LAHORE, AND LAHORE IS ME

19

PRINCE LAVA – THE NAMESAKE OF LAHORE

23

ON THE BANKS OF RIVER RAVI

24

THE MAN WITH A MESSAGE

27

THE DIVIDING LINE

29

BORDERS AND ATROCITIES

31

PAKISTAN – A SOVEREIGN STATE

32

LAHORE – A SURVIVOR

33

THE FORTIFIED NUCLEUS

35

A CITY WITHIN A CITY

39

THE OLD CITY

41

THE HARMONIOUS TURBULENCE

43

THE INTANGIBLE

47

CHARACTERS OF THE STORY

49

RESIDENTS OF THE WALLED CITY

50

INDIVIDUALS INVOLVED IN COMMERCIAL ACTIVITY

51

HAWKERS AND BUSKERS

52

INDIVIDUALS AFFILIATED WITH TOURISM

53

AUTHORITIES 54 THE FREE-THINKERS – THE VISIONARIES

55

INTERLACED ACTIVITIES IN THE WALLED CITY

56

WHAT IS HERITAGE?

65

THE SPICED RICE (PILAU)

67

TRANSCENDENCE 69 THE HERITAGE STANDARD: GRAND AND THE MONUMENTAL

71

MUMMIFIED DYSTOPIA

73

THE BEAUTIFULLY MUNDANE

75

COLONIZED HERITAGE

77

A ‘GLASS CASE’ FOR ‘TOURIST GAZE’

81

THE DECISIONMAKERS INSTITUTIONS

83 84

AND HERITAGE AN AUTHORI - TOPIA (AUTHORITATIVE UTOPIA)

COMMUNITY-BASED TOURISM THE LIVING LIBRARIES: PAPER-PLANES AND POETRY

87

89 91

THE COMMUNITY-PARTICIPATION APPROACH

95

HOMESTAYS IN THE WALLED CITY

97

LAHORE’S FOOD CULTURE

99

ARTISANS – THE LIVING HERITAGE OF LAHORE

101

INTEGRATE AND CREATE

107

THE PHANTASMAGORIC SKY

109

MURKY SKY

111

GLITTERING KITES

113

THE FLOATING UTOPIA

115

A LIVING CITY

117

RESIDENTS: THE HEART OF THE WALLED CITY

117

HEARTY OLD MEN, GOSSIPING, SURVEYING...

118

BHAI-CHARA (BROTHERHOOD) 121 ROOF-TOP CULTURE

122

SECRET MEETINGS AFTER CURFEW

128

ROPES AND LADDERS

129

COURTYARDS: THE LIVING VOID

130

PROSPECT AND REFUGE

131

CULTURAL IMPLICATIONS OF COURTYARDS

133

COURTYARDS – THE SOCIAL HUB OF THE DWELLINGS

135

PIGEONS AND PROJECTIONS

136

THREE-DIMENSIONALITY OF THE COURTYARD

137

COURTYARDS AND CIRCULATION

138

COURTYARD – A WELLNESS COMPOUND

143

COURTYARDS AND SUSTAINABILITY

147

JHAROKA – NOT JUST A BALCONY

148

‘ JHAROKA DARSHAN ’

149

JHAROKAS AND ROMANCE

151

A FEMINIST UTOPIA

153

THE SCARLET ENIGMAS OF LAHORE

156

THE DYSTOPIAN SUBCULTURE

161

THE UTOPIAN ENIGMAS

163

THE ENSEMBLE OF BAZAARS

165

SWEET AFFAIRS

167

ACTIVITIES PILED AND ENTWINED

169

A KALEIDOSCOPE FOR SOARING BIRDS

171

BRIDGING BAZAARS

173

MAGIC POTIONS, HORSES AND BICYCLE RIMS

175

COMMERCIALIZED DYSTOPIA

177

THE THREATS FROM THE CLOTH MARKET

181

MONEY TALKS

183

TAPERING OFF THE MONSTROSITIES

185

THE UTOPIAN BAZAAR CULTURE

187

CROWDED ROADS AND TRAFFIC JAMS DONKEY CARTS, CARS, BULLOCKS, AND TRUCKS...

188 189

IMAGINE AUTO-TOPIA

193

THE MOVING CITY

195

FLOATING AND TRANSPORTING

197

ROBOT DONKEYS AND MECHANICAL BULLS!

OPEN SPACES; CULTURAL ROOTS CHARACTER OF THE VOIDS

ATROCIOUS ENCROACHMENTS EXTENSIONS; NOT ENCROACHMENTS

199

201 202

205 207

THE FRUIT SHOP, ROLLING DICE, CARROM BOARD, AND CRICKET

209

NAAYI KI DUKAAN (THE BARBER SHOP)

211

SWEET TEA, SPICY BIRYANI, AND REVOLUTIONARY IDEAS.

213

IMAGINE COLLABORATION

215

REFERENCES 216

12

Shanzeh Usman

ABSTRACT The Utopian Palimpsest is a visual story of the 11th-century Walled City of Lahore – it is a tale transporting the audience through its rich past, deteriorating present, and an array of innovative possibilities for a utopian future. The Walled City has been destroyed, rebuilt, recreated, and revamped repeatedly to cater to its inhabitants. This project, too, aspires to add layers to this urban palimpsest. The story envisions a series of alternative worlds, reimagining the fabric of the Walled City. A city drenched in complex socio-economic, religious and political issues, often fails to explore fantastical and unorthodox trajectories, reserved for more ‘progressive’ parts of the world. The goal of the thesis is to re-envision the Walled City for co-living, co-sharing, co-existing, and collaboration amongst the diverse actors involved. It is a story that sensitively weaves the existing traditional lifestyle of the people in the Walled City amidst magical, often dystopian, and bizarre scenarios. The Utopian Palimpsest re-imagines the ‘living’ cultural heritage that is deeply embedded in a strong sense of community. It aspires to tap into the utopian vistas offered by a city steeped in romanticism.

The Utopian Palimpsest

13

14

Shanzeh Usman

“Fantasy is hardly an escape from reality. It’s a way of understanding it.” Lloyd Alexander

The Utopian Palimpsest

15

16

Shanzeh Usman

LAHORE; THE ANCIENT WHORE “Lahore—the ancient whore, the handmaiden of dimly remembered Hindu kings, the courtesan of Moghul emperors—bedecked and bejeweled, savaged by marauding hordes—healed by the caressing hands of successive lovers… like an attractive but aging concubine, ready to bestow surprising delights on those who cared to court her—proudly displaying royal gifts.” The precariously balanced description by Bapsi Sidhwa, in her novel, The Pakistani Bride, captures the intriguing essence of the indulgent city. Some might argue that the once alluring concubine hasn’t aged well – it has merely survived. However, the haunting nostalgia of the city lingers, as does the intoxicating scent of jasmine flowers merging with carnations, springing innumerably within the ‘City of Gardens’. The large banyan trees still provide shade to hearty old men engrossed in political banter, smoking hookahs under the scorching heat of Lahore’s undeniable companion – the sun. The blissful months of winter are a welcoming contrast to the thick, humid summer air. Lahore’s divine winter sky, studded heavily with vibrant kites, captured by poets and painters, is no longer azure. A pale, dusty, yellow hue, surrounded by a mysterious ring of pollution, is rapidly compromising magnificent architectural marvels that the city boasts. The heady, grey smoke spewing out of ragged rickshaws, dust from construction sites, and the charcoal ignited for barbeques is another memory I associate with Lahore. Maybe, that is the reason I subconsciously often smoke when missing home. Lahore turned me into a smoker. I blame the whore!

The Utopian Palimpsest

17

18

Shanzeh Usman

I AM LAHORE, AND LAHORE IS ME Nostalgia is a haunting ghost, painting vivid yet often unrealistically beautiful visuals of contrasting memories. Memories of resting under the rose-tinted bougainvillea shrubs, getting lost in tales woven intricately by my nani (grandmother). Memories of showering under the heavy monsoon rains and dancing in poorly choreographed performances at extravagant weddings. A memory that I have retained is picking up my friend, Minahil, on my way to college and sneakily taking a detour in the congested Shadman Market to buy a packet of cigarettes. My tattered blue car, infamously known as Shetty (named after an over-performing Bollywood actor), had seen better days before barely surviving the untamed traffic of Lahore - Shetty was a pitiful sight and complimented the market around it. Minahil scanned the crowd to ensure that no one recognizes us – it is not proper for young girls to be smoking and gossip spreads like wildfire in Lahore. “Toffees, Fanta, chai?” inquired Arshad, the young man with lingering eyes from the khoka (corner store). He smiled shyly upon learning that we wanted cigarettes. Arshad discreetly covered our purchase in brown paper, as shop owners do with sanitary pads and contraceptives, giving us a pleasantly surprising discount. Maybe, the memory is so clear in my mind because it was a daily occurrence, and Arshad became my friend. We shared polite pleasantries during the transactions and he strived to bring my regular smokes to the car before other shop-owners gathered inquiringly to eye the female smokers. Arshad’s khoka was a small encroachment, battling with the car parking space and other intrusions. The market was heavily congested and loud, with barely any space for Shetty to park, or Arshad’s stall to even exist. I often wondered if they could just hang these tiny khokas up, dangling from the thick air, like light bulbs just so there was enough room for some wind to breeze through!

The Utopian Palimpsest

19

20

Shanzeh Usman

Snippets of another memory that linger in my mind and heart are those of sauntering through the narrow streets of the Walled City of Lahore, blocking out the distracting honking of cars and sinking into the enchantment of the city - of what it once was, what it is today and what it can evolve into. My thoughts - an odd amalgamation of tales of war, love, empires and bazaars, life, religion, and continuity - of being submerged in the mystique of Lahore.

The Utopian Palimpsest

21

22

Shanzeh Usman

PRINCE LAVA – THE NAMESAKE OF LAHORE

The very name of the city is grounded in legend and folklore. Oral history suggests that the city’s namesake, and founder, is Prince Lava - son of the Hindu god, Rama, and the hero of the epic, Ramayana. According to the Holy scripture, Lava’s mother, Sita, banished herself from the kingdom due to the gossip of the locals about her sanctity. I am not surprised that the very origin of the city indicates how gossiping is deeply-rooted in the culture of Lahore. A temple encased within the Lahore Fort still stands tall yet empty, in honor of Prince Lava.

The Utopian Palimpsest

23

ON THE BANKS OF RIVER RAVI Lost in its own silent rhythm, the Ravi sings its song. In its undulating flow I see the reflections in my heart— The willows, the world, in worship of God I stand at the edge of the flowing water I do not know how and where I stand— In the wine-colored dusk The Old Man shakily sprinkles crimson in the sky The day is returning to where it came from This is not dew; these are flowers, gifts from the sun Far off, a cluster of minarets stand in statuesque splendor Marking where Moghul chivalry sleeps This palace tells the story of time’s tyranny A saga of a time long spent What destination is this? A quiet song only the heart can hear? A gathering of trees speaks for me. In midstream, a boat hurtles by Riding the relentless currents, Darting beyond the eye’s curved boundary. Life flows on this river of eternity Man is not born this way; does not perish this way Undefeated, life slips beyond the horizon, But does not end there. The poetry is from ‘On the Banks of River Ravi’, by Muhammad Allama Iqbal – translated by Parizad N. Sidhwa.

24

Shanzeh Usman

Lahore originated along the ancient route from Kabul to Delhi, via Khyber Pass, on the western bank of the unpredictable River Ravi. Like many ancient cities, Lahore was once a Walled City, fortified during the Mughal empire. The city encompassed by a fortress boasts splendors of heritage and architecture. Lahore thrived and survived through the epoch, adapting to the raving demands of its captors and users. The overflow of people, industry, and the congestion dictated Lahore to gradually encroach upon its rural surroundings. Today, Lahore encompasses the Mall Road, boasting deteriorating examples of Indo-Gothic architecture, shaded by massive eucalyptus trees, flowing towards the Cantonment, DHA, and as far and wide as the Bahria Town. It now sprawls, rather gracelessly, over 1770 square kilometers of urban congestion, inhabited by 11 million people.

The Utopian Palimpsest

25

26

Shanzeh Usman

THE MAN WITH A MESSAGE I often found myself amidst the commotion of Liberty Market – an apt representation of Pakistan. The Market is an absurd composition of traffic-laden roads, beggars, fakirs, buskers, upper-class women purchasing high-end clothes from designer outlets, the lewd men shamelessly ogling them, colorful fabrics displayed in open-air markets and opulent restaurants with pretentious French names. Amidst the cauldron of this peculiar diversity, I often encountered a treat for sore eyes. A determined, old man sat peacefully protesting in the chaotic Liberty Market roundabout. Ikram-ul-Haque had experienced the war of independence firsthand while honing a strong sense of love for his motherland. He visited the same location, often multiple times a week, merely holding a thought-provoking poster stating, “We want Jinnah’s Pakistan again.” (Jinnah – the founder of Pakistan). The simple words with a powerful message often forced me to reminisce over the tales of sufferings, longings, and colossal losses that eventually founded Pakistan. Haque recently passed away, and I still foolishly hope to see him, his poster, and his determined smile, every time I pass by the Liberty Market. Perhaps, there should have been a peepal tree shading him against the raging sun or a cathedral of lights constructed around him so that his message blazed as bright. The Liberty roundabout is often the site of peaceful protests, gatherings, and vigils. I wonder if urban installations would complement a powerful message, encourage people to rise, and accommodate their voice. Haque’s voice still echoes softly in my ears. The old man with a message is undeniably a lost jewel in the crown of Pakistan.

The Utopian Palimpsest

27

28

Shanzeh Usman

THE DIVIDING LINE

You tore into our land a crooked line. That morning we learned: the dawn had been bitten by moths, flying in droves, in madness towards light. Unsure of the nature of light, they had consumed everything. This poem was originally commissioned by the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at NYU on the occasion of the closing of the exhibition ‘Zarina: Dark Roads’.

The Utopian Palimpsest

29

30

Shanzeh Usman

BORDERS AND ATROCITIES I recall decorating my neighborhood with green pennants, dangling on strings, and hoisting the proud flag of Pakistan every Independence Day. The tradition was followed by visiting my grandmother for evening chai. We celebrated the birth of Pakistan in a gathering blessed with ignorant bliss, until one year when my grandmother shattered this innocence. “I was walking back from school, with books clutched in my hands. It was Friday, and I was looking forward to the weekend, dreading the math assignment that came with it. I was hoping that my father had returned from the mosque after the congregational prayer. However, when I reached my haveli, my world collapsed,” she recalled. “My father was hanging lifelessly from the ceiling of our patio - a Sikh man did it, my neighbors claimed, maybe he killed a Sikh too. I covered my sister’s eyes, gathering whatever I could in my satchel, and left my home, to go home.” In August 1947, a massive struggle of decades resulted in the collapse of the British colonial rule in India. Atrocities spanning for over two centuries were overcome by the emasculated population, leading to the independence of the Indo-Pak subcontinent – but the stains of colonization rooted in the divide and rule policy, culminated in the Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs pitting against each other, splitting the once syncretic, motherland in half. Hence the traumatic experience both, politically and emotionally of one of the greatest mass migrations in recorded history commenced – over 15 million people were uprooted and 2 million slaughtered. Trains loaded with immigrants, poured in and out of the newly-founded state, often reaching their destination tainted scarlet - with nothing but bloodied corpses. My grandmother arrived to Pakistan in one of those horrendous trains amidst a landscape of violent victory. She had arrived to her new home – Pakistan.

The Utopian Palimpsest

31

PAKISTAN – A SOVEREIGN STATE Pakistan is located in South Asia, surrounded by four immediate neighbors; it is bordered on the north-east by China, on the east by India, and the west by Iran and Afghanistan. The disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir lies on the northeast tip of the country. Pakistan is a federation of four provinces. These provinces are Sindh, Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (formerly North-West Frontier Province) and Baluchistan. In addition, there are also federally and provincially administered areas such as the capital city of Islamabad (or the Islamabad Capital Territory) and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) as well as the Provincially Administered Tribal Areas (PATA) (Sohail 2020). The significant rivers in Pakistan are the Indus and its four tributaries; the Ravi, Chenab, Sutlej, and Jhelum (Hasan 2002). My grandmother emigrated from Amritsar to the cultural capital of Punjab – Lahore, a city in chaos, a city striving to survive.

32

Shanzeh Usman

LAHORE – A SURVIVOR

Lahore is amongst the few cities in South Asia boasting an uninterrupted, yet checkered ancient history. The city’s geographically strategic location hypnotically pulled the vested interests of Persian and Afghani kingdoms, which clashed with those of northern Indians. It has, thus, experienced an almost continuous flow of visitors, pilgrims, and inevitably invaders. Lahore, once the camping ground of the early Aryans was under the rule of the prince of Chauhan at the time of the first Muslim invasions. For centuries, the Hindu rulers of Lahore withstood the invasions, attacks, and plundering, while eventually being defeated by the forces of Mahmud of Ghazni obliterating the Hindu principality of Lahore. The city has witnessed a fascinating concoction of turbulence, tranquility, invasions, and catastrophic devastations. It has survived the Sultanates (1206-1524), the Mughal Empire (1524-1712), and Sikh Raj (1764-1849), followed by the British colonial period and a painful Partition in 1947. Therefore, its prosperity ebbed and flowed as a result of the sovereign changes. The city has been erased, revamped, recreated, and embellished multiple times, layers over layers – Lahore is undeniably a survivor.

The Utopian Palimpsest

33

34

Shanzeh Usman

THE FORTIFIED NUCLEUS

When you conquer a gem as precious as Lahore, protecting it from eyeing invaders may induce sleepless nights. Maybe building a wall around the city helped the Mughal emperor Akbar embrace slumber peacefully. In 1584, Akbar made Lahore his headquarters and enclosed the city within 30 feet high brick walls. The wall was segmented with thirteen grand wood and iron gates, allowing entrance into the city. I can still distinctly recall the names of the gates – Delhi Gate, Yakki Gate, Sheranwala Gate, Kashmiri Gate, Masti Gate, Roshnai Gate, Lohari Gate, Bhatti Gate, Shah Alami Gate, Akbari Gate, Mochi Gate, Taxali Gate, and Mori Gate. I remember cramming the names of the gates for my history exam in school. I found myself easily distracted and day-dreaming about the tales concealed within the once stoic gates of the city during the zenith of the Mughal Rule – the visuals of Mughal emperors, mounted on their royal horses while entering through the grand gates, the alluring stroll of dancing girls of the once-thriving Hira Mandi, heady scent of spices sold in the surrounding bazaars, powers of healing potions invented by hakims and the grandeur of architectural marvels erected by the Mughals occupied my active imagination. There is no denying that the Mughals were romantics – lovers of art and architecture. No wonder Shah Jehan erected the Taj Mahal in loving memory of his wife, and Hiran Minar to honor his treasured antelope; rather than educational institutions. Immersed in my sea of thoughts, I took my sweet time memorizing the names of the gates!

The Utopian Palimpsest

35

36

Shanzeh Usman

During the Sikh reign, Ranjit Singh expanded his empire and added a moat around the city for defense. But the walls and the moat couldn’t withstand the British colonization. The measures taken to safeguard the city by its preceding rulers crumbled to the ground. The British eradicated the fortifying walls, filled the moat, and created a Circular Garden around the city. Carefully avoiding the congested Walled City, the colonizers embarked upon the development of its surrounding outskirts, studding it with a unique expression of Indo-Gothic architecture. In the early 1900s, the British rebuilt the thirteen gates varying from its original Mughal era form. These are the gates we see today. Some of them were burnt to the ground while others collapsed when battling the raging war against time. Six of the remaining gates still stand, amongst which Roshnai Gate is the lonely survivor of the Mughal era. If the mighty walls were erected once again, I wonder if they would protect the Walled City from its demons. Probably not, because the invaders lie deep within the fabric of the city, treacherously creeping into the remnants of its heritage. No tangible wall is tall or sturdy enough for protection. In today’s context, the wall is a metaphor for utopian ideas and alternative trajectories that allow the varying stakeholders of the Walled City to co-exist blissfully.

The tumbled walls still hold a city within a city – this city is the heart of my delirious utopia.

The Utopian Palimpsest

37

38

Shanzeh Usman

A CITY WITHIN A CITY

The Lahore Metropolitan area covers 2, 300 square kilometers, of which the Walled City of Lahore occupies a 2.5 square kilometer stretch of the dense structure. Within its thirteen gates, the city accommodates more than 22, 000 buildings and has offered shelter and employment for closely fifteen percent of the metropolitan population (Rab 1998). In the recent years, Lahore has begun to surge inexorably southwards. The Walled City of Lahore is situated in the north-western quarter of Pakistan’s second-largest city, Lahore, which is the provincial and cultural capital of Punjab. The Walled City is locally referred to as the Androon Shehr or the Inner City, as it represents the nucleus from where the metropolitan city originated during the 11th century and expanded. A barricade no longer contains the Walled City, but an imaginary periphery still signifies a primordial sense of ‘inside’ and ‘outside’.

The Utopian Palimpsest

39

40

Shanzeh Usman

THE OLD CITY

The old city stands, basking in the ever-fading glory of distant times. Bustling, it still is with the antiquated spirit of a civilization that flourished within its walls The archaic structure peels off slowly, once thought invincible At odds with the bare luxury of advancement galore, stealing the space once all its own It clings to history it holds in its rattling bones The old city remains with somber grace, in parts, though lone and withdrawn Receding from the influx of metal and machine Yet holding its ground as the last reminiscence of an era that was. This poem was by Nosheen Irfan, written in 2016.

The Utopian Palimpsest

41

42

Shanzeh Usman

THE HARMONIOUS TURBULENCE Live electrical wires boldly intertwining with colorful fairy lights, tattered kites, and hoardings creeping across the horizon – casting shadows on the world that breathes beneath. Donkey-carts, motorcycles, trucks, cars, and pedestrians alike battle for their right to passage over the narrow alleyways of the Walled City, cursing and beeping, while commercial activity flurries. Shop owners and street vendors alike holler, advertising their goods, striving to attract customers. The aroma of freshly prepared food wafts into the air, as people sitting under the embrace of a tree devour it.

The Utopian Palimpsest

43

44

Shanzeh Usman

Amidst this unique merger of harmonious turbulence stand marvels of architectural heritage, alluring tourists to sink into the grandeur of the past – one such site is the Lahore Fort. Before 1556, the Fort had been constructed, damaged, demolished, rebuilt, and restored various times. Today, it seemingly stands as a historic spectacle. However, its gardens, palaces, halls, and dungeons conceal colorfully the, often, obscure tales of love, war, serenity, and dishevels. Lahore Fort has witnessed the many states that once prevailed and the greed for the throne, which embellished the fortress. The fort has an oddly eerie yet appealing ‘abandoned’ character today. However, historically, the ostentatious entrance to the royal quarters of the emperors allowed several elephants carrying members of the royalty to enter. The small Moti Masjid (Pearl Mosque), adorned in white marble, was initially built for the private use of the ladies of the royal household and was later converted into a Sikh temple and a state treasury during the period of the Sikh rule, under Ranjit Singh. The other architectural treasures include the Mughal-style gardens (Char Bagh) and the Sheesh Mahal (Palace of Mirrors). The Sheesh Mahal, decorated with intricately carved glass, was built for the empress and her court – it was also installed with screens to conceal them from prying eyes. The Naulakha Pavilion, another addition, is decorated with pietra-dura inlay, studded with semi-precious jewels laden in floral motifs.

The Utopian Palimpsest

45

46

Shanzeh Usman

THE INTANGIBLE

Tourists pour into the acclaimed UNESCO World Heritage Site, Lahore Fort, steeping in its glory. I, a flaneur, in my own right, often visit this chaos, not to pay my tribute to the wonders that the Mughals left behind, but to bask in the intangible heritage that the city upholds. This intangible heritage is the ever-evolving unique culture of the Walled City, springing from within the diverse set of actors in our story.

The Utopian Palimpsest

47

48

Shanzeh Usman

CHARACTERS OF THE STORY

The Utopian Palimpsest

49

RESIDENTS OF THE WALLED CITY

These actors include the residents of the Walled City. From the man whose greatgrandfather flew a handcrafted kite on the same rooftop as he had in his childhood, to the widowed woman who remembered moving into her quaint home in the Walled City after losing her beloved during the independence migration.

50

Shanzeh Usman

INDIVIDUALS INVOLVED IN COMMERCIAL ACTIVITY

The Walled City is bustling with commercial activity. From Ali’s family-run shop selling wooden spoons, the artisan continuing his forefather’s legacy of carving and selling semi-precious ethnic jewelry to wholesale traders and multinational corporations.

The Utopian Palimpsest

51

HAWKERS AND BUSKERS

The street hawkers decorate the labyrinth-like lanes of the Walled City with their fruits, vegetables, and everyday items.

52

Shanzeh Usman

INDIVIDUALS AFFILIATED WITH TOURISM

These actors include the facilitators of the tourism industry. These predominantly cater to the affluent class of local tourists fascinated by the meticulously designed ‘heritage amusement park’ within the Walled City, as well as the international tourists curious to connect with the culture.

The Utopian Palimpsest

53

AUTHORITIES – (MAINTAINING THE INTEGRITY OF THE WALLED CITY)

This group of actors includes the local authorities as well as international organizations like ICOMOS and UNESCO, which intend to promote the maintenance, preservation, and restoration of the Walled City. The local authorities are accountable for great responsibility, but are often distracted by commodifying heritage and minting coins.

54

Shanzeh Usman

THE FREE-THINKERS – THE VISIONARIES

The Walled City has inspired lovers and poets, painters and dancers, writers, and visionaries, sitting under the shade of a tree, sipping hot tea, and immersing in their ocean of thoughts amidst the cauldron of sounds, flashing colors and movements.

The Utopian Palimpsest

55

INTERLACED ACTIVITIES IN THE WALLED CITY

56

Shanzeh Usman

The three primary over-lapping activities, conducted by the stakeholders in the Walled City, can be categorized into residential, commercial, and tourism-related.

The Utopian Palimpsest

57

RESIDENTIAL ACTIVITIES

58

Shanzeh Usman

COMMERCIAL ACTIVITIES

The Utopian Palimpsest

59

ACTIVITIES IN PUBLIC SPACES

60

Shanzeh Usman

TOURISM-RELATED ACTIVITIES

S

TOURISM RELATED ACTIVITIES

The Utopian Palimpsest

61

62

Shanzeh Usman

These activities don’t function as independent entities but coexist within this congested drumming engine, intricately intertwined with each other. The actors conducting these activities, the building stock, and the urban fabric amalgamates to create the culture and heritage of the Walled City.

63

The Utopian Palimpsest

63

64

Shanzeh Usman

WHAT IS HERITAGE?

The dispersion of Eurocentric ideologies, labeled as the authorized heritage discourse or AHD (Smith 2006), focuses on material and monumental forms of ‘old’ or aesthetically pleasing, often tangible, heritage. The ‘heritage’ promotes a consensus version of both the past and the present. Instead, an alternative conception of heritage is developed, which establishes and cultivates themes of memory, performance, identity, intangibility, dissonance, and place.

The Utopian Palimpsest

65

66

Shanzeh Usman

THE SPICED RICE (PILAU)

A fond memory from my adolescence that I cherish is of cooking pilau (spiced rice) with my father. His grandmother passed on a treasured recipe that she carried with her while migrating from the terrains of Kabul. For generations, this recipe was improvised, cherished, and recreated, resulting in a hearty meal shared amongst the loved ones. In the context, the dish itself is not merely my heritage but the act of creating it, passing it down, and renewing associations to cement present and future communal and familial relationships. Even if the dish completely changes, or is not being created at the moment, its transcendental being too is heritage. If heritage is a mentality - a way of knowing and seeing, then all heritage becomes, in a sense, ‘intangible’ (Smith 2006).

The Utopian Palimpsest

67

68

Shanzeh Usman

TRANSCENDENCE

Understanding the basis of heritage helps comprehend how not just the bricks and mortar, marble, and ornaments of the ancient structures are heritage but also the lore that it encapsulates. The transcendent memories exist regardless of time, space, and the limits of the building that encloses these.

The Utopian Palimpsest

69

70

Shanzeh Usman

THE HERITAGE STANDARD: GRAND AND THE MONUMENTAL Lahore Fort upholds its significance because of the royalty that resided there. The Badshahi Mosque (the Royal Mosque) is a wonder because the name itself pays tribute to the ruling elite. The grandeur buildings and their eligibility to be considered heritage remains certain. However, it is thought-provoking how often the grand and the monumental is epitomized as heritage. Heritage can un-problematically be identified as ‘old’, grand, monumental and aesthetically pleasing sites, buildings, places and artefacts. This privileges monumentality and grand scale, innate artefact or site significance tied to time depth, scientific or aesthetic expert judgement, social consensus and nation building (Smith 2006). In accordance with this criterion, a set of building stock affiliated with small factions of the once privileged elite heavily overshadows the heritage of subaltern groups. This creates a hollow perception of heritage, claiming a set of an extravagant built structure as the sole representative of the diverse peoples’ legacy. In doing so, selective monumental heritage is elevated on a pedestal, and disconnected from its roots; the people, traditions, emotions, and alternative legacies. This process compromises the evolving social, economic, psychological, and cultural values of everyday life - values that are the rightful essence of heritage.

The Utopian Palimpsest

71

72

Shanzeh Usman

MUMMIFIED DYSTOPIA

The values embedded in the Walled City cannot be simplified and attached to a set of ‘mummified’ building stock. This kind of ‘mummification’ is often per the static ‘conserve as found’ ethos (Smith 2006). Within this narrative, the tangible elements present in historic sites are objectified and preserved, lacking association with their foundations and the evolving regional realities.

The Utopian Palimpsest

73

74

Shanzeh Usman

THE BEAUTIFULLY MUNDANE It is irrefutable that, inevitably, the extraordinarily extravagant is commemorated, overshadowing the ordinary. The banal, intangible legacies of communities are what uphold their heritage. In the case of the Walled City of Lahore, it is not just the palaces of the royals or even the stacked houses of the ‘commoners’ that reflect heritage. This statement does not dismiss the tangible but merely de-privileges it, to comprehend that fabric is not its sole manifestation. Heritage also lies in the everyday activities and the mundane normalcy where the sense of community builds in quintessence. It is the empty buckets that women sling down like Rapunzel hair from their jharokas (semi-enclosed balconies) to purchase groceries from street vendors. It is the trust they have in the hawker to provide them with fresh produce while lowering down their hard-earned money. It’s about bargaining compulsively regarding their everyday purchases just for the sake of conversing. Banter that evolves into sharing with the neighbors, what is intended to be prepared with these groceries. Here lies the heritage that creates the Walled City of Lahore; concealed within the mundane act of buying tomatoes and onions.

The Utopian Palimpsest

75

76

Shanzeh Usman

COLONIZED HERITAGE Colonization is not limited to custody over land, its manpower, or the riches. It is deeply engaged in influencing the minds, ethics, and social strata, while naturally institutionalizing the meaning of heritage for a nation. The industrial character that came with the colonial control became the basis for actions that caused morphological, typological, and technological alterations that alienated the innercity with its ordinary, everyday character. The insensitive, often superficial, comprehension of the heritage of the Walled City of Lahore is evident in Lord Curzon’s speech, the Viceroy of India, to the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1900. India is covered with visible records of vanished dynasties, of forgotten monarchs, of persecuted and sometimes dishonored creeds. These monuments are […] in British territory, and on soil belonging to (the) Government. Many of them are in out-of-the-way places, and are liable to the combined ravages of […] very often a local and ignorant population [...] All these circumstances explain the peculiar responsibility that rests upon Government in India […] They supply the data by which we may reconstruct the annals of the past, and recall to life the morality, the literature, the politics, the art of a perished age […] Indeed, a race like our own, who are themselves foreigners are in a sense better fitted to guard, with a dispassionate and imperial zeal, relics of different ages […] [A] curtain of dark and romantic mystery hangs over the earlier chapters, of which we are only slowly beginning to lift the corners [for] displaying that tolerant and enlightened respect to the treasures of all, which is one of the main lessons that the returning West has been able to teach to the East. (Curzon of Kedleston 1900) In claiming stringent stewardship over the relics of the past and rendering the ‘ignorant local population’ and ‘dishonored creeds’ irrelevant, the colonizers have displayed a non-holistic approach towards heritage. Thus, the adherence of heritage to the perceived identity of the dominant ruling elite and the western definitions of heritage, of tidy control, has long polluted the legacy of the Walled City. The Utopian Palimpsest

77

78

Shanzeh Usman

The values of mummified heritage are steeped in the 19th-century Romanticism aesthetic, championed by Morris and Ruskin. In his work, The Seven Lamps of Architecture ([1849] 1899), Ruskin argued against the dominant practice of restoration, where historic buildings would be ‘restored’ to ‘original’ conditions by removing later additions or adaptations. For Ruskin, the fabric of a building was inherently valuable and needed to be protected for the artisanal and aesthetic values it contained. “We have no right whatever to touch them. They are not ours. They belong partly to those who built them, and partly to all generations of mankind who are to follow us” (Ruskin 1849). In pre-partitioned India, the local people were rendered simpletons, with no regard for their culture and an inability to deal with their built environment. In colonial perception, the Inner City was a chaotic accumulation of narrow and torturous streets, with tall houses that seemed a potential hotbed of disease and social instability, and especially, difficult to observe and fathom (Glover 2008). This simply did not match their Victorian sensibilities. Rudyard Kipling stood on the minaret of Wazir Khan Mosque, which was a popular European vantage point for observing the city without having to be in it. He describes his view of the inner city in City of Dreadful Nights, admiring how the inhabitants ‘can even breathe’: Seated with both elbows on the parapet of the tower, one can watch and wonder over that heat-tortured hive till the dawn. “How do they live down there? What do they think of ? When will they awake?” […] A small cloud passes over the face of the Moon, and the city and its inhabitants – clear drawn in black and white before – fade into masses of black and deeper black. (Glover 2008) Heritage steeped in mysticism, romantic ardor and a sense of community, had been simplified, institutionalized and grotesquely colonized.

The Utopian Palimpsest

79

80

Shanzeh Usman

A ‘GLASS CASE’ FOR ‘TOURIST GAZE’ Imagine a view from the fifth floor of the Mughal-themed boutique hotel, painting a ravishing visual of ancient forts, palaces, and dwellings. The air-conditioner blasting against the hellish heat, plush Persian carpets, room-service catering the cuisine once devoured by Mughal royalty prepared in the imperial kitchen – feels like heaven. Oh, look the horse carriages painted so vibrantly, a man dressed in an extravagant emperor’s costume – utterly enchanting. What’s the congestion, precariously conceived behind the ancient mosque? Is that a family of eight inelegantly pack on a motorbike behind the curtain? The voyeuristic view of heritage often projects a simplified, censored, and sanitized version of reality. The disconnection with the holistic concept of heritage and viewing it as frozen music trivializes a breathing being into an artifact. The ‘glass case’ display mentality (Merriman 1991) associated with museum exhibitions is equally evident in certain interpretations of heritage sites and places. (Urry 1990) identifies the institutionalization of the ‘tourist gaze’ and the way this gaze constructs reality and normalizes a range of touristic experiences. The ‘heritage industry’ is responsible for commodifying selective remnants of the past, catering to upper-class leisure and touristic pursuits; undermining the users of a historic core.

The Utopian Palimpsest

81

The president of Lahore Conservation Society, Kamil Khan Mumtaz, reflects deep concern regarding the intensifying penetration into the tourism industry (Sohail 2020). “You don’t need these colorful rickshaws; hotel operators and God knows who else – to pull down these lovely heritage buildings so that they can build a lovely heritage hotel. They are going to make money out of this and we will have lost the last traces of our humanity.”

82

Shanzeh Usman

THE DECISIONMAKERS

The users of historic sites have been popularly classified as passive recipients of an environment that is conceived, executed, managed, and evaluated by the outside; the public or private sector, landowners, and developers with professional expertise (Paul Jenkins 2009). In the context of the Walled City of Lahore, the ‘outside’ refers predominantly to the decisionmakers, which play a significant role in navigating the lives of the users.

The Utopian Palimpsest

83

INSTITUTIONS AND HERITAGE Under the Walled City of Lahore Act 2012, the Walled City of Lahore Authority (WCLA) was created by the Punjab Government. It is the appointed autonomous body for the regulation and management of the functions of the entire Walled City of Lahore. The Act defines heritage not merely as individual buildings but an integral whole comprising its ‘architectural, archaeological, monumental, historic, artistic, aesthetic, cultural or social [legacy], elements [and] features of a building and building fabric, groups of buildings and structures, urban fabric, urban open spaces, public areas, public crossings or public passages, as well as the environment of the Walled City, including intangible heritage’ (AKCSP 2018). The city undeniably offers a vast potential for tapping into the heritage tourism industry. The Director-General of the Walled City of Lahore Authority (WCLA), a retired army official, Kamran Lashari, shows keen interest in this aspect. The institution has been focusing primarily on preserving acclaimed heritage sites and takes great pride in UNESCO validated and award-winning projects. Furthermore, WCLA skims over the restoration of residential buildings, preservation of facades, and improving the infrastructure of the urban fabric. The idea of an entire city as heritage is new to Pakistan. In the cities of developing countries, it is simply not economically possible to retain an entire stock of urban heritage and the national or local budgets rarely stretch to urban conservation (Assi 2008). The motive of the local government to enlist the historic building stock on the protection list becomes a cause for quick and visible actions, like recreating or even inventing history.

84

Shanzeh Usman

In 2006, the Sustainable Walled City Project (SDWCLP) began, funded by the World Bank, with a particular intention of developing cultural tourism. This was followed with plans for restaurants, hotels, tourist transportation, and handicraft boutiques. The project involved the execution of a pilot project, which led to the creation of a heritage trail, ‘to showcase methods and the benefits of the conservation of cultural assets, and their productive use and reuse’ (Roquet, et al. 2017). The rehabilitation included façade and street improvements, conforming to Mughal-era forms, with the provision of new municipal infrastructure and services; designing a carefully-choreographed heterotopia within the Walled City. “The understanding of heritage and the attempt to protect or conserve it is deeply political. It appears to me that their understanding of the city reduces to a place where non-Walled City residents come to entertain themselves.” Ahmed Rafay Alam, an environment lawyer, and activist, comments on the prevailing inclinations of the authorities concerned.

The Utopian Palimpsest

85

86

Shanzeh Usman

AN AUTHORI - TOPIA (AUTHORITATIVE UTOPIA) The barrier erected amidst the city conveniently partitions the sanitized pictureperfect grandeur of the past from the intangible heritage of the Walled City of Lahore. This intangible heritage is callously perceived as flawed and inadequate for the purpose of minting money. It is easier to commodify a ‘heritage theme park’, skillfully concealing the very real, imperfect, yet complex world behind a brick wall. The tourists must not see what lies behind the division – it doesn’t sell. The local residents of Old Lahore must not be involved in the decision-making of how their heritage is molded, objectified, or liquidated. Why share the economic benefits? Let’s construct higher walls of brick, mortar, and deceit until a faction of the city turns into a museum, and its people lose all rights to their home and legacy. The ‘Disneyfication’ of heritage sites, by creating controlled, developed, and deviously preserved zones for mass tourism, conflicts with the interest and lifestyle of the residents. The trend places their culture in a sterilized ‘bubble’ while varying agencies extrapolate the benefits of tourism.

The Utopian Palimpsest

87

In such a situation, a need for a personalized model of sustainable tourism arises for the Walled City of Lahore.

88

Shanzeh Usman

COMMUNITY-BASED TOURISM

The Utopian Palimpsest

89

90

Shanzeh Usman

THE LIVING LIBRARIES: PAPER-PLANES AND POETRY Guided tours exclusively for tourists, mounted on traditional carriages, streaming through heritage sites, are a unique experience. Of course, the tours, aided by well-rehearsed speeches by tour guides from a history book, are informative. It is fascinating to learn where the royals devoured their meals and how the Badshahi Mosque (The Royal Mosque) has stood tall for centuries. However, it is an entirely different experience sitting under the shade of a tree, immersing in the tales imparted by the living libraries of Lahore, over a cup of tea. An aged man shares the horrors of the bloody partition riots he experienced, and with it the tale of how he met his beloved wife of sixty years: “A striking beauty stood looking out her window, our eyes met, and my heart leaped. It was as simple as that. We didn’t have mobile phones, and I couldn’t count her in public, fearing ‘tainting’ her character. I began to compose poetry for her, folding papers clumsily into planes and floating them through her window. This very window...”, He points towards a four-story building. “Eventually, her heart warmed up towards me, and I arranged for my parents to visit her family, asking her hand in marriage. We spoke for the first time after our wedding ceremony.” No organized tour can condense a culture so distinct, or capture the essence of a story so simple.

The Utopian Palimpsest

91

92

Shanzeh Usman

It is undeniable that the lives of the residents of the Walled City of Lahore intertwine with the heritage and culture of the city – even if they might not be aware of the memorized facts as fluently as the trained tour guides from the greater Lahore – they boast a great fountain of knowledge regarding cultural practices. There is a need for tour-guide training programs, exclusively conducted for the residents, and alternative excursions, guiding tourists through a closer to reality cultural experience. The heritage sites of Lahore offer a wealth of potential for tourism, which presents a source of employment in varying sectors of hospitality. Tourism can lead to infrastructural developments such as an improved network of roads, public transport, water, and electricity supply, which can benefit tourists as well as residents. However, it is essential to comprehend that the Walled City is not just a hub of monumental heritage but also houses an invaluable living culture, altering inevitably with time. Tourism ought to be rooted in the cultural practices and the lifestyle of the people. ‘Culture should be regarded as the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of society or a social group, and that it encompasses, in addition to art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs’ (UNESCO 2001).

The Utopian Palimpsest

93

94

Shanzeh Usman

THE COMMUNITYPARTICIPATION APPROACH The unique heritage of the Walled City demands an unconventional system of sustainable tourism – a system in which bare minimal economic gains don’t trickle down (from the rich) upon the local inhabitants. This type of tourism development model builds upon environmental and ecological resources and is generally based on a grass-roots approach with the participation of local communities and stakeholders in the planning process (Boo 1990). The purpose of participation is power redistribution, enabling the society to fairly redistribute the incurred benefits and costs from it (Arnstein 1969). The community-participation approach is, often, advocated as an integral part of sustainable tourism development. The negative impacts of tourism reduce, it is believed, while the positive effects enhance, as participation increases the carrying capacity of a community (Haywood 1988, Jamal 1999, Murphy 1985). Researchers have also doubted the possibility of implementing community participation. Taylor (1995) criticizes ‘communitarianism’ as romanticism that is not rooted in reality. However, a city like Lahore, immersed in mysticism and nostalgia, demands a romantic approach.

The Utopian Palimpsest

95

96

Shanzeh Usman

HOMESTAYS IN THE WALLED CITY Boutique hotels animating the Mughal-era lifestyle of the privileged elite allow tourists to only penetrate the heritage of Old Lahore on a very shallow surface. An alternative approach is the concept of homestays with the local inhabitants of the Walled City. (Lynch 2005) defines homestays as a specialist term referring to types of accommodation where tourists or guests pay to stay in private homes, where interaction takes place with a host or the family usually living upon the premises, and with whom public space is, to a degree, shared. Imagine lodging in the humble abode of a local, inhabiting a portion of a grand haveli (traditional mansion) for generations. The haveli encloses a courtyard with a shabby fountain that no longer functions and is shared by multiple families. The accommodation is simple, and the amenities modest. However, the world is real, full of stories of everyday life, and personalized knowledge only accumulated through living first-hand in the Walled City. Homestays not only provide an opportunity for the locals to showcase their prided hospitality, but also allow women primarily occupied in household commitments to generate income and experience cultural diversity.

The Utopian Palimpsest

97

98

Shanzeh Usman

LAHORE’S FOOD CULTURE

Lahoris unapologetically love food, and who could blame them? The city boasts a variety of delicious cuisine - an inheritance from the Indian and Persian influences, perfected through generations. Experiencing local cuisine is an integral aspect of tourism. This experience is not just about devouring a plate, but also immersing in the elaborate food culture of the city. Sitting under an embellished chandelier, enveloped by the intricately ornamented walls of a Mughal-themed restaurant, is a treat for the local and international tourists alike. High-end restaurants cater a menu fit for royalty, coupled with Mughal-themed costumes, adorned by the waiters. The environment takes you on a fantastical journey, recreating the glory of the past. The experience is what it stands for, precisely – ‘heritage theme parks’ recreating the splendor of the past. However, these pretentious restaurants don’t do justice to the ‘real’ food culture of Lahore – a culture that encircles around the experience of selecting livestock from a nearby shed and slow-cooking the meat in open air over lingering conversations. This experience is found in small-scale, family-run eateries, offering a relatively authentic meal and experience at nominal prices. Perhaps, these small eateries could offer communal cooking while sharing family recipes and stories they wish to impart.

The Utopian Palimpsest

99

100 Shanzeh Usman

ARTISANS – THE LIVING HERITAGE OF LAHORE The Mughal emperors were great patrons of arts and crafts, evolving the heart of their empire, the Walled City, into an artisan cluster. The city’s dense tangle of alleyways thrived with weavers, ironsmiths, masons, miniaturists, jewelers, and cobblers. This constellation of artisans was disrupted time and again as a result of the political instability. People poured in and out of the Walled City - however, the craftsmen’s continuity was grounded in their skills. Some of them continue their legacy to this day. Amidst a cacophony of overpowering vehicular traffic of the Taxali Gate, a determined craftsman intricately carves a tabla (classical hand-drum) – an acquired skill he inherited through generations, which practiced instrument-making in the Indian subcontinent. Once upon a time, his forefathers crafted the melodious dholaks (two-headed hand-drum), to which the dancing girls of Hira Mandi swayed. The city still upholds the custom of hand-made instruments, varying from the traditional flutes, drums, and harmoniums to guitars and violins.

The Utopian Palimpsest 101

102 Shanzeh Usman

The same locality houses workshops of the shoemakers. The cobblers continue their tradition, crafting a variety of traditional footwear – khussas, khairis, and chappal, created with pure cow or sheep leather, ornamented with tilla (gold thread). The clanking and drilling of the blacksmiths of the Kasera Bazaar echo the creation of swords and armors for the ancient city’s soldiers and rulers. Today, these metalworkers produce scissors for the tailors and cobblers of Lahore, harmoniously binding craft industries. The treasured jewelry-makers, battling with mass production, occupy small shops in the Suha Bazaar fashioning traditional trinkets in gold and silver. Meanwhile, in the jostling streets of Urdu Bazaar, a few artisans diligently practice the art of book-binding and book-making, indulging in old techniques from the golden age of the 12th-century Baghdad (Parvez 2017).

The Utopian Palimpsest 103

104 Shanzeh Usman

The women of Old Lahore are often solely steeped in household activities and are in dire need of programs like the Naqsh School of Arts, established in 2003. This institution upholds the motto ‘preserve for posterity’ and offers workshops for traditional drawing, painting, ceramics, and calligraphy. Institutions like these provide an opportunity for the women and men of less affluent localities to develop artistic skills and partake in the craft-tourism experience.

The Utopian Palimpsest 105

106 Shanzeh Usman

INTEGRATE AND CREATE

Interactive forms of community-based tourism in the Walled City of Lahore are not merely about purchasing traditional crafts from artisans. The act of buying an ethnic token of memory, in the form of a well-crafted souvenir, is not a wholesome cultural experience – the essence of these crafts does not lie clearly in the resulting object. It rests in the cultural practice of creation itself. Experiencing cultural tourism is also not about watching artisans create masterpieces, displaying their process and lifestyle like an artifact in a museum. It is about participating in integration with the community and embarking on a creative journey in innovative craft-design workshops – weaving connections with the people.

The Utopian Palimpsest 107

108 Shanzeh Usman

THE PHANTASMAGORIC SKY

A vibrant sky studded with a mass of soaring kites isn’t just a mere phantasmagoria but an event steeped in the centuries-old tradition of kite-making and kite-flying in Lahore. The once-celebrated annual festival of Basant, which is steeped in Hindu mythology, marking the end of winter and the herald of blossoming spring, allowed this tradition to prevail. At the festival, families, and friends, would gather over narrow rooftops, expertly handling kite strings with calloused hands, hoping to emerge victorious from the battle of kites. The lethal casualties caused by dangerous metallic kite strings manufactured in recent years resulted in banning Basant. However, this does not undermine the ancient tradition, rooted in the street culture, of kite-flying and kite-making. It is not only a profession of crafting high-quality kites, with varying designs and sizes but a skill that most locals proudly swank. Young boys constructing kites, with light-weight paper and bamboo sticks for leisure, is undeniably their legacy.

The Utopian Palimpsest 109

110 Shanzeh Usman

MURKY SKY

However, the azure blue sky dancing with vibrant kites turns murky as the sun sinks under the shadows of dusk. The street lights, once brightening the city, no longer enliven the gloom. The shortage of electricity and the excessive consumption of fossil fuels results in electrical power outages. Load-shedding renders the city dreary for hours at a stretch in the evening, daily. Oil lamps and melting candle wax pile up as people sit in their homes, helplessly anticipating the electricity’s unpredictable return.

The Utopian Palimpsest 111

112 Shanzeh Usman

GLITTERING KITES

Lahore’s dearest friend and foe, the sunlight, filters through the thin, colorful paper of the kites, soaring high in the daytime sky, creating a ravishing painting of shades and shadows upon the world lying below. Imagine these kites soaking in the immortal energy from the sun, absorbing it in customized solar panels designed on the kites. As the daylight fades, and the streetlights fail to shine, the rooftops once again come to life with the innumerable kite enthusiasts, expertly manipulating their glittering kites to wander in the sky. The stars, which fail to shine over the polluted horizon, are replaced by kites - bedazzling the sky while radiating the many absorbed rays of sunlight.

The Utopian Palimpsest 113

114 Shanzeh Usman

THE FLOATING UTOPIA

Heritage is not merely a thing of the past – it hones a fluid nature, one that demands the sensitive developments to coincide with the alterations through time and space. The cultural values and meanings are knitted intricately with the cultural change within the regional realities. I wonder, does a kite need to be shaped like a perfect diamond? Maybe, it can be the shape of a box? Perhaps, that box can carry objects? Possibly, a love letter or a basket of fruit for the neighbors. Could these age-old kites evolve into the new delivery service, carrying objects, traditional pizzas, milk, and yogurt to their respective consumers? What if the kites could just transport people around, take the load off the heavily-laden urban fabric of the Walled City?

The Utopian Palimpsest 115

116 Shanzeh Usman

A LIVING CITY

The Walled City of Lahore is a living city. It’s a breathing being that grows and develops, inhales and exhales, wrinkles and ages, alongside its inhabitants.

RESIDENTS: THE HEART OF THE WALLED CITY The residents of the Walled City grew up from playing hockey in their adolescence within the narrow alleyways to playing board games and smoking hookah on tharas (stoops on footpaths) of their neighborhoods. They found food, shelter, family, livelihood, romance, and an ethereal sense of community within these invisible walls of the Old Lahore. Historically, the Walled City constituted essentially a largely residential land-use and was organized into administrative zones called guzars (the principal thoroughfares that led in from the entrance gates). Each guzar was informally organized into mohallas (neighborhoods), galis (streets), and kuchas (dead ends). These created a hierarchical network of circulation spaces, creating security, social privacy, and quietude. These residential neighborhoods, forming a unique urban ensemble, have housed some of the locals for generations and promoted a strong bond of brotherhood, culture, and a sense of community (AKCSP 2018).

The Utopian Palimpsest 117

HEARTY OLD MEN, GOSSIPING, SURVEYING... Valuable actors within this community are multitasking, hearty old men. For generations, having resided in the Walled City, they know of every nook and crook like the back of their hands. Often gathered together in small groups, they are found sitting on their charpoys, smoking hookahs, gulping tea, debating politics, settling disputes, and gossiping for hours each day. This activity has been an integral part of their lives for most of their mature adulthood. These men are comparable to security cameras for their neighborhoods - keeping tabs on who bought a new bike, the latest brawl between two cranky women, and forbidden romances – they know it all!

118 Shanzeh Usman

However, this leisure time is being compromised by the heavy traffic in the city, the emergent street vendors, and a deprived sense of privacy. I wonder - what will a space look like, personalized for these stakeholders to keep their communal activity afloat? Should there be a designated space in a particular corner of the neighborhood, partially shaded by trees while these men survey the neighborhood activities with their watchful eyes?

The Utopian Palimpsest 119

Or, should they be elevated with a customized machine, so they can scan the city from a pedestal while life bustles beneath them?

120 Shanzeh Usman

BHAI-CHARA (BROTHERHOOD) Haji Rafique is a native of Mochi Gate and the owner of the area’s well known traditional mithai (sweet) food chain. Senior inhabitants, like Haji Rafique, hold the Walled City’s unique culture and bhai-chara (brotherhood) in high esteem. Despite being a successful businessman and having a house in Lahore’s Jauhar Town locality, Haji Rafique chooses to spend much of his time at his ancestral home in Mochi Gate (Ezdi 2007). Residents like Haji Rafique, who could afford to move out of the congested Walled City to more peaceful and developed parts of Lahore, continue to return to the streets they grew up in – to sit along with their friends, chattering, and downing tea endlessly.

The Utopian Palimpsest 121

ROOF-TOP CULTURE ROOF-HOPPERS Within the congested urban fabric of Old Lahore, rooftops play an integral role in the lives of the residents. Kite-flying has been an important leisure activity for the youth of the city. Intoxicated by the floating kites, and the urge to capture a falling one lost in a duel, young boys fluidly jump from rooftop to rooftop. The buildings are close together but the fall between them is steep. However, the adventureseeking youth casually hops around their neighbor’s rooftops to meet friends, catch a falling kite, or glance at their crushes.

122 Shanzeh Usman

I wonder if connecting the rooftops between houses through bridges would convenience them?

The Utopian Palimpsest 123

HANGING LAUNDRY, DRYING SPICES, AND HOLLERING CONVERSATIONS The activity on the rooftops is not limited to kite flying. A woman sits on the roof of her house, picking stones out of lentils, while her neighbor on the left is hanging wet laundry. Another woman is drying spices under the sun while one just came to the scene to be a part of the group. These women holler at each other, sharing pleasantries, stories, recipes, and tattles while carrying out their household activities.

124 Shanzeh Usman

Would merging the scattered rooftops into one big surface allow them to form a stronger bond? Would they sit together on one charpoy while running errands?

The Utopian Palimpsest 125

SLEEPING CONSTELLATIONS Sleeping under the stars is a romantic notion, which is not uncommon for the residents of the Walled City. When small rooms shared by multiple family members get too uncomfortable for warm summer nights, people often sleep on their rooftops. The charpoys, with sleeping residents dotting the roofs across the neighborhoods, form constellations of their own.

126 Shanzeh Usman

LIVING ROOFTOPS Rooftops in the Walled City house a variety of diverse activities. Perhaps, sustainable roof design would provide the locals with a more welcoming environment to carry out their daily activities. Living rooftops would not only drop the temperatures within the building but also allow a comfortable slumber under the star-studded summer night sky. Furthermore, innovative design solutions like green roofs provide an oasis for the community, simultaneously balancing out the negative effects of climate change on the building stock (Harvey and Perry 2015).

The Utopian Palimpsest 127

SECRET MEETINGS AFTER CURFEW While the rooftops are dotted with residents engulfed in slumber, the youth prepares for their nightly meetings – snagging a smoke or delivering a love letter without getting caught. In the traditional family system of the Old Lahore, when it gets dark, lights are turned off, and doors are locked. However, this doesn’t stop the young rebels of the city from escaping their homes. They often climb down drainage pipes and sling ropes to the ground, carefully concealing their nightly escapades from their family members.

128 Shanzeh Usman

ROPES AND LADDERS

Slinging ropes and sliding down cold metal pipes – the communal activities of the nocturnal youth must be worth the trouble. Perhaps, a few wooden bars could transform these multifaceted drainage pipes into ladders. This might accommodate the post-curfew friendly gatherings and harmless rebellions.

The Utopian Palimpsest 129

COURTYARDS: THE LIVING VOID An integral element in the dwellings of the Walled City is a courtyard. The courtyard-typology has existed in South Asia for thousands of years and can be traced back to the Indus Valley Civilization (McIntosh 2008). The courtyards were a prominent feature in Islamic, as well as Indian architecture, before the dawn of Islam in the region. Traditionally used as a central space between houses or rooms owned by individual families, courtyards served as the focal point of a settlement, strengthening interior relationships. They served as a protective barrier against the climate, enemies, animals, and encouraged social interactions, becoming an important interface for all communal activities (Mishra 2016).

130 Shanzeh Usman

PROSPECT AND REFUGE

A consistent indoor environment cuts us from the outside world and brings in no social, cultural, or aesthetic richness to a place (Hosey 2012). (Annemarie S. Dosen n.d.) has identified the concept of prospect and refuge as survival-advantageous characteristics creating rewarding spaces. The shelter is a necessity for humans to protect themselves from climate and other threats. Jay Appleton has referred to this characteristic as ‘refuge’ (Appleton 1996). Simultaneously the need for open spaces is identified as ‘prospect’. Both cannot be present in one space but they must be contiguous and fluid. The courtyard typology houses these characteristics. It offers a sense of refuge, within the indoor spaces, flowing into an open-to-sky void. The void forms the heart of the dwelling – it acts as the communal center of the house, promoting social interactions, enhancing a sense of security, and providing a therapeutic connection to nature.

The Utopian Palimpsest 131

132 Shanzeh Usman

CULTURAL IMPLICATIONS OF COURTYARDS Courtyards in South Asia hold a spiritual and religious significance. These multifaceted open-to-sky courtyards provide space for religious gatherings and activities – from the central placement of the holy Tulsi (Basil) plant in Hindu culture to the concept of private, segregated areas for women in Islam. This translates to an introverted design, providing women with outdoor spaces, without exposing them to the general public. Therefore, traditionally in the Walled City, dwellings boast two courtyards, following a gradient from formal spaces to informal spaces – the outer one is for the males and the inner one for the women and children of the house. Baithak is a male domain and serves as a transition between the public and private space (Thapar 2004).

The Utopian Palimpsest 133

134 Shanzeh Usman

COURTYARDS – THE SOCIAL HUB OF THE DWELLINGS A few women scatter around the fountain, preoccupied with spinning, cleaning cotton, and embroidering. The others are engrossed in cooking a hearty meal for their families while keeping a watchful eye on their children playing tirelessly. The aroma of food merges with the scent of nature, filling the space. Outdoor furniture, like an elevated podium, creates a space for traditional floor sitting, while charpoys are for sleeping or resting. In winters, a portable fireplace is set up, bringing people together during the chilly evenings. The courtyards in the Inner City traditionally hold a diverse range of functions. These multipurpose open-tosky spaces not only provide a cool space to nap during the scorching summers but also serve as dining and gathering spaces. Large houses boasting courtyards were originally occupied by a single-family unit in the Walled City of Lahore. However, today, multiple families reside within one building, which provides an opportunity for social interaction and integration with neighbors, as private dwellings open into a shared central courtyard. The level of privacy increases with an increase in the floor levels, allowing the residents on the upper floors to look down from their windows. The rooms on the upper floors extend into shaded jharokas, creating a visual connection with the courtyards. The veranda surrounding the courtyards, and the shade of jharokas, provide the users with a sense of refuge. This space becomes suitable for private conversations while still outdoors. Courtyards in the context are voids, acting as an integral circulation nucleus, linking various spaces, and creating a sense of community within controlled environments.

The Utopian Palimpsest 135

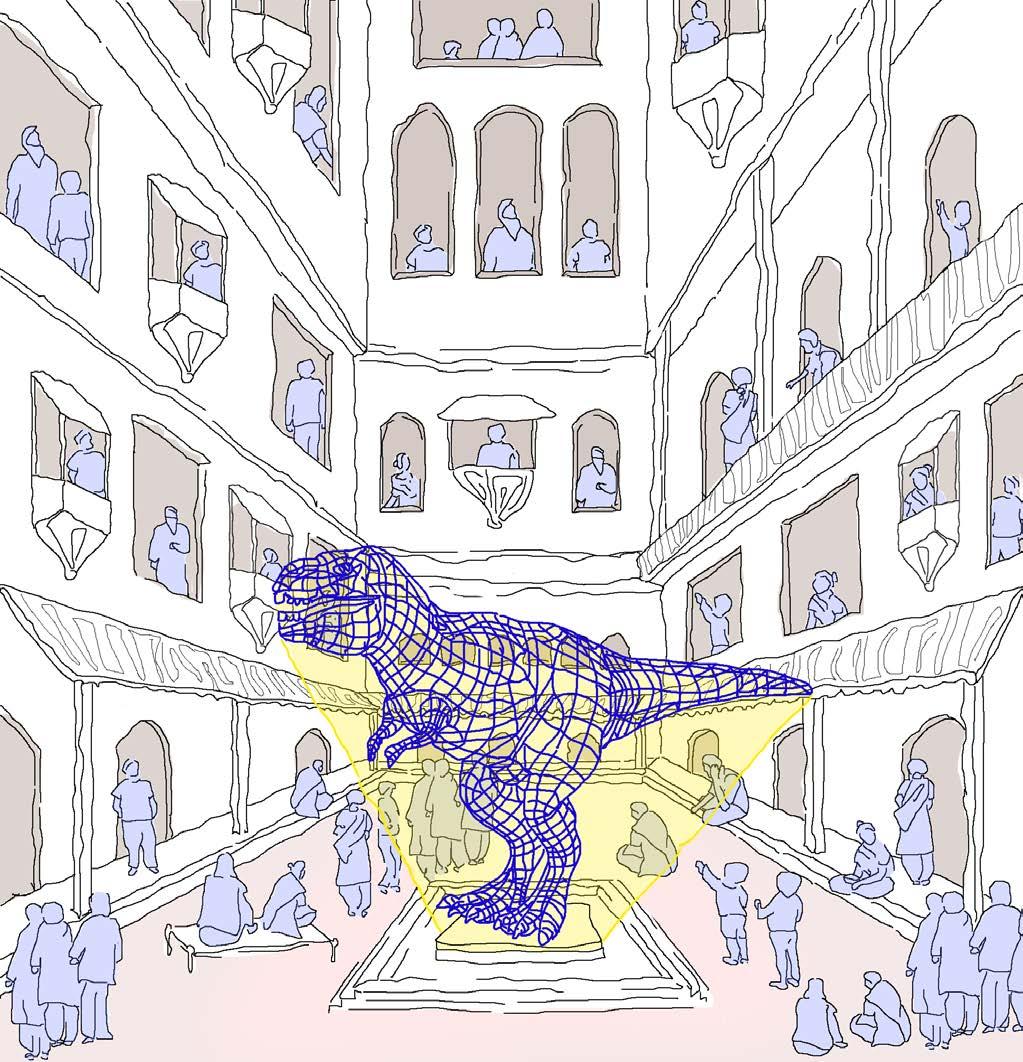

PIGEONS AND PROJECTIONS Traditionally, the people of the Walled City enjoyed a game in which they would set their pigeons free. Whoever’s pigeon returned to their respective cage before the rest was declared the winner. People are no longer inclined to play with birds for entertainment, they have their smart phones to keep them well-occupied. To provide a source of social gatherings within the courtyards, the installation of a large projector screen, running across three to four stories of the haveli enveloping the courtyard, would provide entertainment. This would allow people to enjoy a movie in a communal space. The intervention also utilizes the verticality of the courtyards, as people can sit comfortably in their jharokas or windows enjoying a movie, while others scatter around the open spaces and verandas.

136 Shanzeh Usman

THREE-DIMENSIONALITY OF THE COURTYARD It is also interesting to explore the three-dimensionality of the courtyard. Instead of barring the residents on one side of the wall from the social experience, by covering it with a screen for projection, designing holographic installations viewed from each side, and all levels may engulf the people in shared activities. This intervention can also prove to be a useful source of infotainment.

The Utopian Palimpsest 137

COURTYARDS AND CIRCULATION BASKETS AND ELEVATORS In the Walled City, baskets are often flung down and pulled up with ropes from the jharokas. This is to avoid the uncomfortable stairs, which traditionally have narrow widths and high risers, while transporting items from the multistoried buildings enclosing the courtyard. Since installing elevators within ancient buildings may compromise its structure and heritage value, courtyards provide an interesting void for innovation. The installation of semi-open elevators, conveniently transporting items and people alike, would accommodate people on the upper floors of the building and increase circulation in the courtyard.

138 Shanzeh Usman

BRIDGING JHAROKAS Communication is not only limited to people from various floor levels to the courtyards, but also from one jharoka, window, or door, to another. Bridges, forming connections on different levels while passing through the courtyards, would increase the circulation and social interaction on a vertical as well as a horizontal level.

The Utopian Palimpsest 139

PLAYFUL CIRCULATION Another way to create a connection between these apertures within varying stories while creating a sense of play and excitement is through designing chairlifts! The courtyards often boast swings for children. Perhaps, installing slides through windows would create a sense of thrill for them to glide down into the courtyard and play with friends rather than hunching monotonously over computer screens.

140 Shanzeh Usman

CRAFTS AND PODS The women are occupied, often, with creating traditional crafts in the courtyard. Designing semi-open pods for them would possibly accommodate them to create art and handicrafts in unison

The Utopian Palimpsest 141

142 Shanzeh Usman

COURTYARD – A WELLNESS COMPOUND Courtyards in the Walled City allow an escape from the dense, urban setting to a natural environment. They are traditionally decorated with fountains and plants (Shahzad 2011). The therapeutic healing properties of nature create a sense of sublimity. The scent of the herbs, the visual soothing effect of greenery, and the music of rustling leaves create a world within a void. The water on the ground reflects its surroundings, dispersing the sunlight to form patterns. The seasonal changes affect the aesthetic appeal of the courtyard. In winters, the plants wither out leaving a more barren landscape. When spring arrives, fresh flowers and green leaves show up that are enjoyed all through summer until fall. During Autumn, the plants begin to change color and fallen leaves fill up the courtyard floor (Reynolds 2002). A simple perforated hole in a building block forms an island of relief amidst a bottlenecked environment. Waterbodies in a courtyard create a cooling effect through evaporation. They also provide a serene visual of rippling water and refreshing sounds. A fountain trickling from the fourth story of the building into the courtyard would allow the residents on varying levels and facades surrounding the courtyard, to experience its therapeutic properties.

The Utopian Palimpsest 143

A large tree in the center of the courtyard creates a comfortable sitting space underneath. It also provides the users to experience the tree from different heights. Sitting in the jharokas, amidst the branches and leaves, is an uplifting experience altogether.

144 Shanzeh Usman

Walking around a tree, too, is an enjoyable transition for children and adults alike. Paths, ladders, and ramps linking buildings through a tree in the courtyard create a merger of connection to nature and social integration.

The Utopian Palimpsest 145

A tree could host a treehouse for children too! There is this incomparable charm of a quaint treehouse – it’s a refuge buried in the soothing embrace of greenery, a fortress of solitude, and a childhood dream!

146 Shanzeh Usman

COURTYARDS AND SUSTAINABILITY Courtyards have been referred to as microclimate modifiers due to their ability to moderate high temperatures, channel breezes, and adjust the degree of humidity. However, while tapping into the inherent potential of the role of courtyards as temperature modifiers, under certain circumstances, contemporary design solutions may be implemented. Courtyards are often rendered abandoned if the wind is too harsh, a storm too heavy, or the rain too uncomfortable. People close their windows and find shelter in the seclusion of their rooms. To provide opportunities for shared spaces during rainy days can be pleasant for some. Transformable glass ceilings designed over the void could provide a controlled environment within the courtyard.

The Utopian Palimpsest 147

JHAROKA – NOT JUST A BALCONY Another prominent architectural feature of the Walled City is the jharoka – it is a traditional, oriel window projecting from upper-stories of a building, used in medieval Indian architecture. It extends from the façade of the building in an upper-story overlooking a street, market, or any other open space (Zulfiqar 2018). The prominent elements of a jharoka include a cantilevered balcony with a canopy or pyramid on the top, jalis or lattices, fence, pillars and brackets.

148 Shanzeh Usman

‘ JHAROKA DARSHAN ’

These platforms hold an almost ritualistic historic value. During the Mughal reign, emperors were known to practice ‘jharoka darshan’ – the daily act of appearing on the strategically designed jharoka to greet their patiently awaiting audience in the Diwan-e-Aam (courtyard of the ‘commoners’). It was once an essential custom, creating a bond between the rulers and his subjects. The sun filtered through the intricately carved jalis (lattice) of the heavily ornamented balconies. This play of light and shadows formed enticing geometrical patterns, adding to the allure of the Mughal emperor’s daily appearance on the jharoka. Shah Jehan, during his 30-year reign, never failed to address his audience from his elevated platform alongside his wife, Nur Jehan. The custom held such a prominent value that failure to emerge from the jharoka during his illness in 1657 lead to the rumors of his death (Koch 2010).

The Utopian Palimpsest 149

150 Shanzeh Usman