42 glauben beliefs #6 fortytwomagazine Ein Thema—Zehn Perspektiven The Interview Magazine for Those Who Wonder

It’s impossible not to believe. We all have a view of the world that is reflected in our beliefs. “I believe that” is what we say when we express our opinion. And when someone expresses views that are too far removed from our own values and worldview, we don’t believe them. But that doesn’t mean that beliefs are immutable. Our point of view can change. And similarly, a belief can change us. Did you know that a belief can affect how we perceive pain and that we believe different things depending on whether we are speaking our native language or a foreign language?

I am pleased that you, dear reader, are holding the 6th issue of fortytwomagazine in your hands, with its ten scientific perspectives and one artistic angle—this time coming from the artist Daria Chernyshova—on the topic of beliefs. Paul Hedges, who teaches Interreligious Studies in Singapore, tells us how surprisingly little religion originally had to do with belief. However, religious belief can, under certain circumstances, lead people to feel less pain, as was shown in an astonishing study by neuroscientist Katja Wiech of the University of Oxford. Linguist Panos Athanasopoulos reveals how language can help us think more analytically. He also explains why we should never use our native language at the poker table. And speaking of analytical thinking: In our interview with economist Nicola Gennaioli, we not only discuss how rational we humans really are but also one great human invention that only works because we believe in it: money. Meanwhile, social psychologist Pia Lamberty answers a question we’ve probably been asking ourselves more often since the pandemic: Why do rational arguments not work on conspiracy ideologues? At the international level, too, there is far more at stake than just arguments. Credibility is the decisive factor that gives a country power, according to political scientist Hendrik Ohnesorge. Diplomacy is also not possible without belief.

fortytwomagazine — № 6 3 beliefs

Editorial

While I would like to conclude with a hopeful “Just believe in yourself,” it’s not as simple as that. As sociologist Jasmine Hill points out, this focus on the individual obscures structural inequality. However, we cannot do without trust entirely. If we can’t trust ourselves, then surely we can at least trust in science, can’t we? This is a question we asked Alexander Kaurov of Harvard University’s Department of the History of Science. Because let’s not delude ourselves: Without trust in the researchers who share their findings with us in this issue, you would not be reading this magazine right now. On behalf of the entire team at fortytwomagazine, I wish you an exciting read,

Lena Kronenbürger, Chefredakteurin Editor-in-chief

4 fortytwomagazine — № 6 beliefs

Photo: © Teresa Rothwangl

5 fortytwomagazine — № 6 Daria Chernyshova

Inhalt 6 fortytwomagazine — № 6 — Expert:innen 8 I Verschwörungsglaube 13 Pia Lamberty II Der Glaube an die Wissenschaft 25 Alexander Kaurov III Glaube an das Finanzsystem 41 Nicola Gennaioli IV Placeboeffekt 55 Katja Wiech V Sprache und Wahrnehmung 67 Panos Athanasopoulos VI Religion 81 Paul Hedges — Über die Künstlerin 92 — Daria Chernyshova VII Desinformation 102 Doowan Lee VIII Künstliche Intelligenz 115 Carla Hustedt IX Glaubwürdigkeit in der Diplomatie 129 Hendrik Ohnesorge X Hustle Culture 140 Jasmine Hill Impressum 152 Inhalt

Content 7 fortytwomagazine — № 6 — Experts 8 I Conspiracy Narratives 18 Pia Lamberty II Believing in Science 34 Alexander Kaurov III Beliefs in the Financial System 47 Nicola Gennaioli IV Placebo Effect 60 Katja Wiech V Language and Perception 74 Panos Athanasopoulos VI Religion 87 Paul Hedges — About the Artist 100 — Daria Chernyshova VII Disinformed Beliefs 109 Doowan Lee VIII Artificial Intelligence 120 Carla Hustedt IX Credibility in Diplomacy 135 Hendrik Ohnesorge X Hustle Culture 145 Jasmine Hill Imprint 152 Content

Experts

Pia Lamberty

Pia Lamberty erforscht als Sozialpsychologin, wieso Menschen an Verschwörungstheorien glauben. Sie ist Geschäftsführerin des gemeinnützigen Center für Monitoring, Analyse und Strategie (CeMAS), das interdisziplinäre Expertise zu Verschwörungsideologien, Desinformation, Antisemitismus und Rechtsextremismus bündelt. Lamberty verortet sich an der Schnittstelle von Wissenschaft und Gesellschaft. Gemeinsam mit der Publizistin Katharina Nocun hat sie zwei Sachbücher über Verschwörungstheorien veröffentlicht. Das dritte gemeinsame Buchprojekt erschien im Herbst 2022 zum Thema Esoterik.

Pia Lamberty is a social psychologist who researches the reasons behind people’s belief in conspiracy narratives. She is the managing director of the non-profit Center for Monitoring, Analysis and Strategy (CeMAS), which pools interdisciplinary expertise on conspiracy ideologies, disinformation, antisemitism and far-right extremism. Lamberty positions herself at the interface between science and society. Together with journalist Katharina Nocun, she has published two non-fiction books on conspiracy narratives. Their third joint book project, on the topic of esotericism, was published in autumn 2022.

Alexander Kaurov

Dr. Alexander Kaurov ist wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter am Lehrstuhl für Wissenschaftsgeschichte an der Harvard University, Gastdozent für interdisziplinäre Studien am Institute for Advanced Studies und Forschungsmitglied am Blue Marble Space Institute of Science. Zudem ist er Mitbegründer der Earthlings Hub-Initiative, die Flüchtlingskindern hilft, sich an neue Bildungsumgebungen zu gewöhnen. Kaurovs Forschung untersucht anhand von Datenerhebungen die Art und Weise wie Wissenschaft in der Öffentlichkeit wahrgenommen wird.

Dr Alexander Kaurov is a research associate in the Department of the History of Science at Harvard University, a visitor in the Program in Interdisciplinary Studies at the Institute for Advanced Studies, and an affiliate research scientist at the Blue Marble Space Institute of Science. He co-founded the Earthlings Hub initiative that helps children refugees adapt to new educational environments. Kaurov’s research investigates the public’s perception of science through data-driven methods.

fortytwomagazine — № 6 8 Expert:innen

Nicola Gennaioli

Nicola Gennaioli ist Professor für Wirtschaftswissenschaften an der Università Commerciale Luigi Bocconi in Mailand sowie Forschungsstipendiat am Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) und am European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI). Seine Arbeit konzentriert sich auf die Schnittstelle von Psychologie und Finanzen. In seinem Buch A Crisis of Beliefs (2018) befasst er sich mit den psychologischen Mechanismen, die bei der Finanzkrise 2008 am Werk waren.

Nicola Gennaioli is professor of finance at Università Commerciale

Luigi Bocconi in Milan, as well as a research fellow at the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI). His work focuses on the intersection of psychology and finance. In his book A Crisis of Beliefs (2018) he looks at the psychological mechanisms at work in the financial crisis 2008.

Katja Wiech

Dr. Katja Wiech ist Neurowissenschaftlerin am Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences der University of Oxford, wo sie die Forschungsgruppe Pain & Mind leitet. In ihrer Forschung beschäftigt sie sich vor allem mit Schmerz und der Auswirkung von Glauben, Vorannahmen und Placeboeffekten auf die Schmerzwahrnehmung. Neben dem theoretischen Verständnis, wie Schmerz sich im Gehirn manifestiert, geht es ihr dabei auch um die praktische Anwendung dieser Erkenntnisse in der Schmerztherapie.

Dr Katja Wiech is a neuroscientist at the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences at the University of Oxford, where she leads the Pain & Mind research group. Her research focuses on pain and the impact of beliefs, preconceptions and placebo effects on pain perception. In addition to the theoretical understanding of how pain manifests itself in the brain, she is also concerned with the practical application of these findings in pain therapy.

Panos Athanasopoulos

Prof. Dr. Panos Athanasopoulos forscht an der Lancaster University zu kognitiver Linguistik und experimenteller Psycholinguistik, auf der Suche nach Erkenntnissen darüber, wie unsere Muttersprachen und zusätzlich erworbene Sprachen unser Denken und unsere Weltanschauung beeinflussen.

Prof. Dr Panos Athanasopoulos conducts research at Lancaster University on experimental psycholinguistics and cognitive linguistics to gather more insight in how native and additionally acquired languages affect our thinking and perception of the world.

fortytwomagazine — № 6 9

Experts

Paul Hedges

Prof. Dr. Paul Hedges lehrt interreligiöse Studien an der S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU, Singapur, und ist Visiting Fellow am Clare Hall College der University of Cambridge, UK. Er veröffentlichte zahlreiche Texte über das Zusammenspiel von Religionen und ist Mitglied des Redaktionsausschusses des Journal of Religious History and Interreligious Studies und der Intercultural Theology.

Dr Paul Hedges is an Associate Professor in Interreligious Studies at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU, Singapore, and a Visiting Fellow at Clare Hall, University of Cambridge, UK. He has written extensively on the interplay between religions. He is on the editorial boards of both the Journal of Religious History and Interreligious Studies and Intercultural Theology.

Doowan Lee

Doowan Lee ist CEO und Mitbegründer von VAST-OSINT, einem Start-up, das automatisierte Datenanalysetools entwickelt, um den Ursprung von Desinformation aufzudecken. Er ist Teil der Social Media Governance Task Force des Georgetown University Center on National Security, leitender technischer Berater des Institute for Security and Technoloy und lehrt als außerordentlicher Professor für Politikwissenschaft an der University of San Francisco. Lees Ziel ist es, staatlich geförderte und extremistische Desinformationskampagnen zu bekämpfen.

Doowan Lee is the CEO and cofounder of VAST-OSINT, a start-up that builds automated data analytics tools to detect and expose the origin of disinformation and how it propagates across the media ecosystem. He is part of the Social Media Governance Task Force of the Georgetown University Center on National Security, a senior technical advisor to the Institute for Security and Technology and is teaching as an adjunct professor of politics at the University of San Francisco. Lee aims to combat state-sponsored and extremist disinformation and influence campaigns.

Carla Hustedt

Carla Hustedt leitet die Abteilung Digitalisierte Gesellschaft der Stiftung Mercator. Zuvor führte sie als Senior Project Manager bei der Bertelsmann Stiftung das Projekt Ethik der Algorithmen. Hustedt ist Mitglied des Beirats des Centers for Advanced Internet Studies (CAIS), des Hessischen Kompetenzzentrums für verantwortungsbewusste Digitalisierung und setzte sich für die Enquete-Kommission Künstliche Intelligenz des Deutschen Bundestages mit der Transparenz von KI-Systemen auseinander.

Carla Hustedt is Department Head of the Digitised Society at the Mercator Foundation. She previously led the Ethics of Algorithms project as senior project manager at the Bertelsmann Foundation. Hustedt is a member of the advisory board of the Center for Advanced Internet Studies (CAIS) of the Hessian Competence Centre for Responsible Digitality; she studied the transparency of AI systems for the AI Enquete Commission of the German Bundestag.

10 fortytwomagazine — № 6

Expert:innen

Hendrik W. Ohnesorge

Dr. Hendrik W. Ohnesorge ist Geschäftsführer des Center for Global Studies und Wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter am Lehrstuhl für Internationale Beziehungen der Rheinischen Friedrich-WilhelmsUniversität Bonn. Seine Forschungsschwerpunkte sind Macht, Präsidentschaft und Außenpolitik der Vereinigten Staaten sowie Einfluss individueller Führungspersönlichkeiten. Lehr- und Forschungsaufenthalte führten ihn unter anderem nach Mailand, St. Andrews und Harvard. Er ist Autor u. a. von Soft Power. The Forces of Attraction in International Relations (2020) und Herausgeber von Macht und Machtverschiebung. Schlüsselphänomene internationaler Politik (2022).

Dr Hendrik W. Ohnesorge is the Managing Director of the Center for Global Studies and Research Fellow at the Chair of International Relations at the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-University Bonn. His main research interests are power, presidency and foreign policy of the United States and the influence of individual leaders. Teaching and research stays took him to Milan, St. Andrews and Harvard, among other places. He is the author of Soft Power. The Forces of Attraction in International Relations (2020) and editor of Macht und Machtverschiebung. Schlüsselphänomene internationaler Politik (2022).

Jasmine Hill

Mit ihrer Arbeit will die Soziologin Dr. Jasmine Hill strukturelle Ungerechtigkeiten aufdecken. Derzeit ist sie Lehrbeauftragte für Public Policy and Sociology an der UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs in Los Angeles. In ihrer Forschung untersucht sie die Intersektionalität von Rassismus, Klasse und Kultur, wobei sie sich auf die Erfahrungen von Schwarzen Arbeiter:innen und Familien konzentriert. In ihrer Dissertation beschäftigte sie sich mit mit der Hustle Culture und der Natur des Plattform-Kapitalismus.

Dr Jasmine Hill is a sociologist whose work aims to dismantle racial and economic inequality. She is currently an Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Sociology at UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs in Los Angeles. Her research interrogates the intersections of racism, class, and culture and centers on the experiences of Black workers and Black families. She explored The Hustle Ethic and the Spirit of Platform Capitalism in her dissertation.

Daria Chernyshova

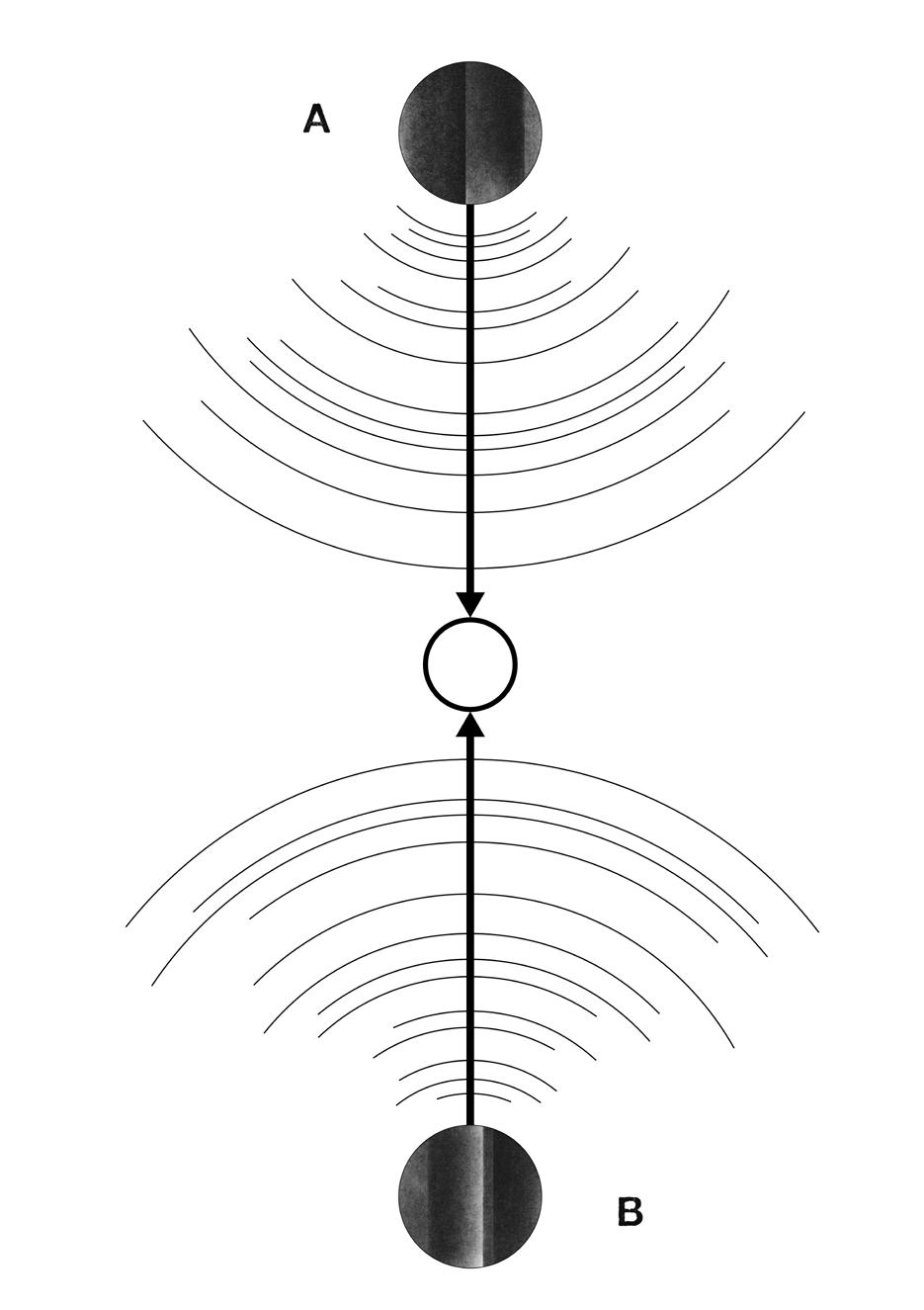

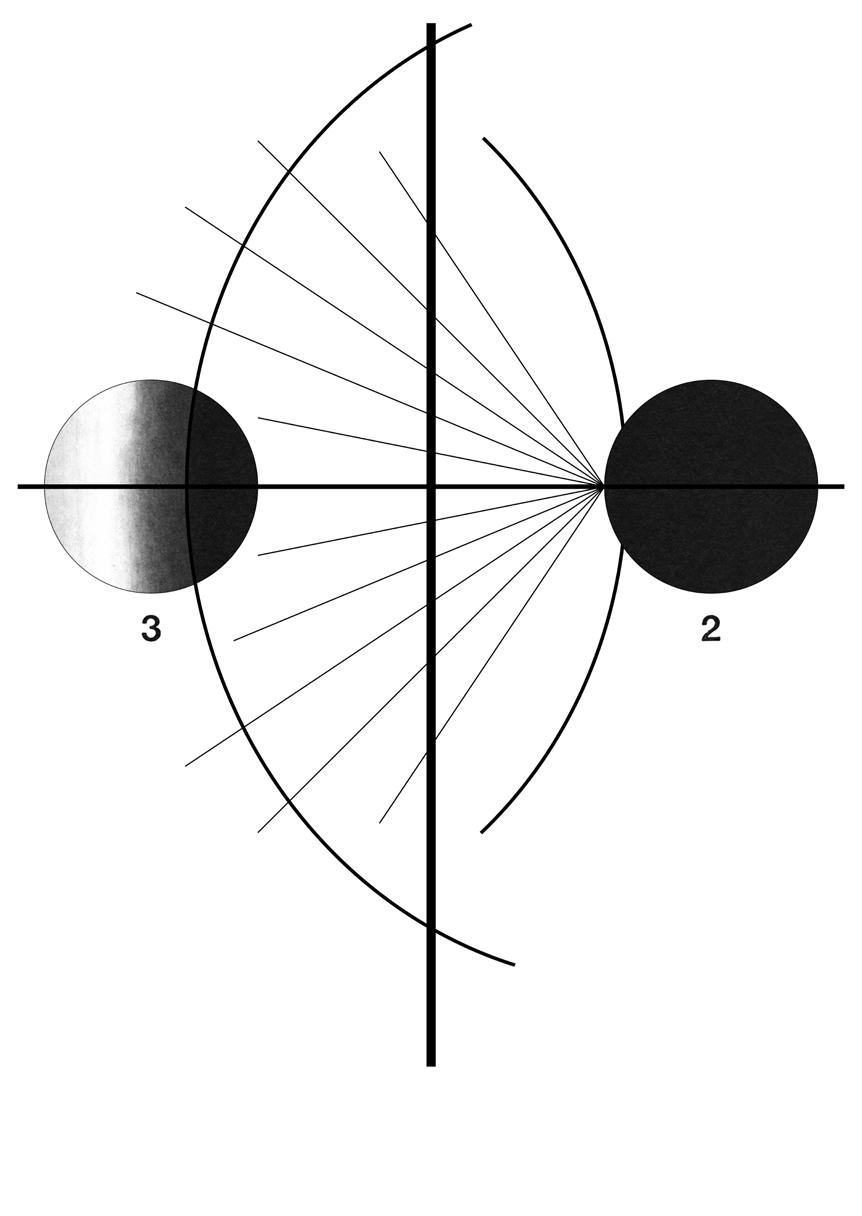

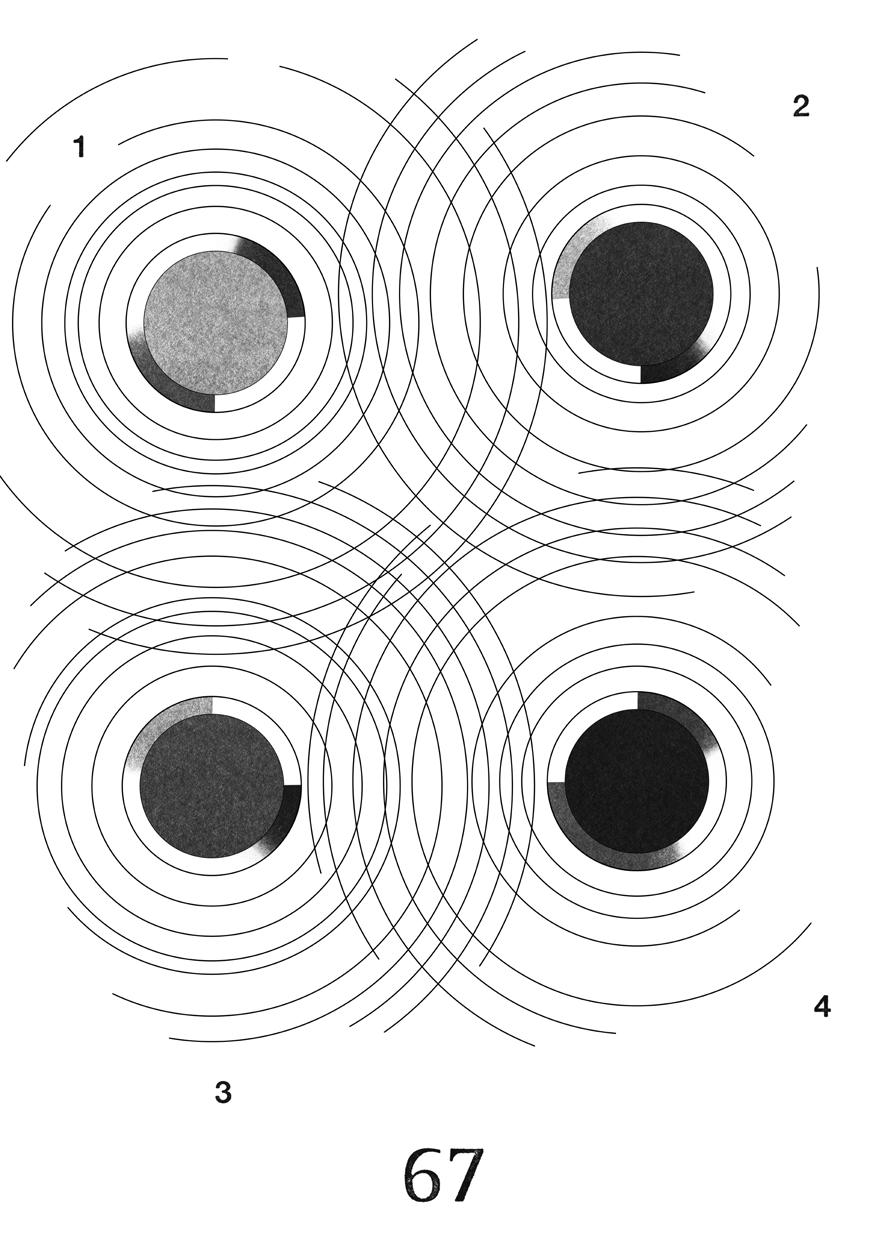

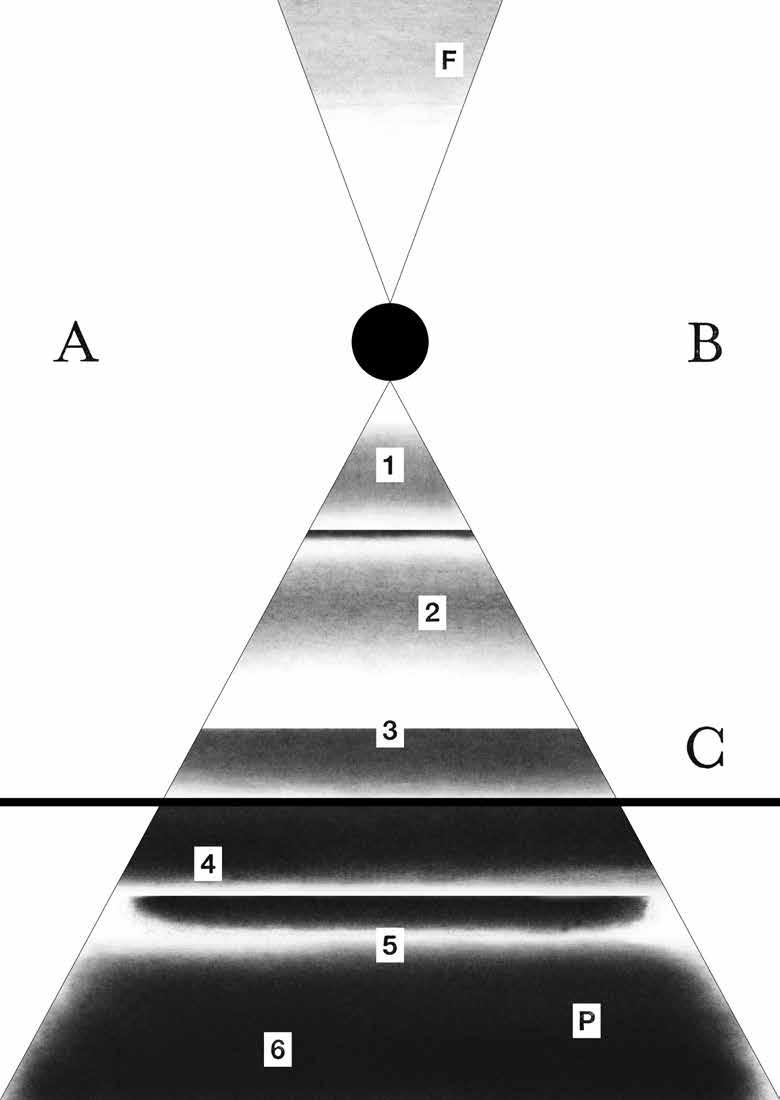

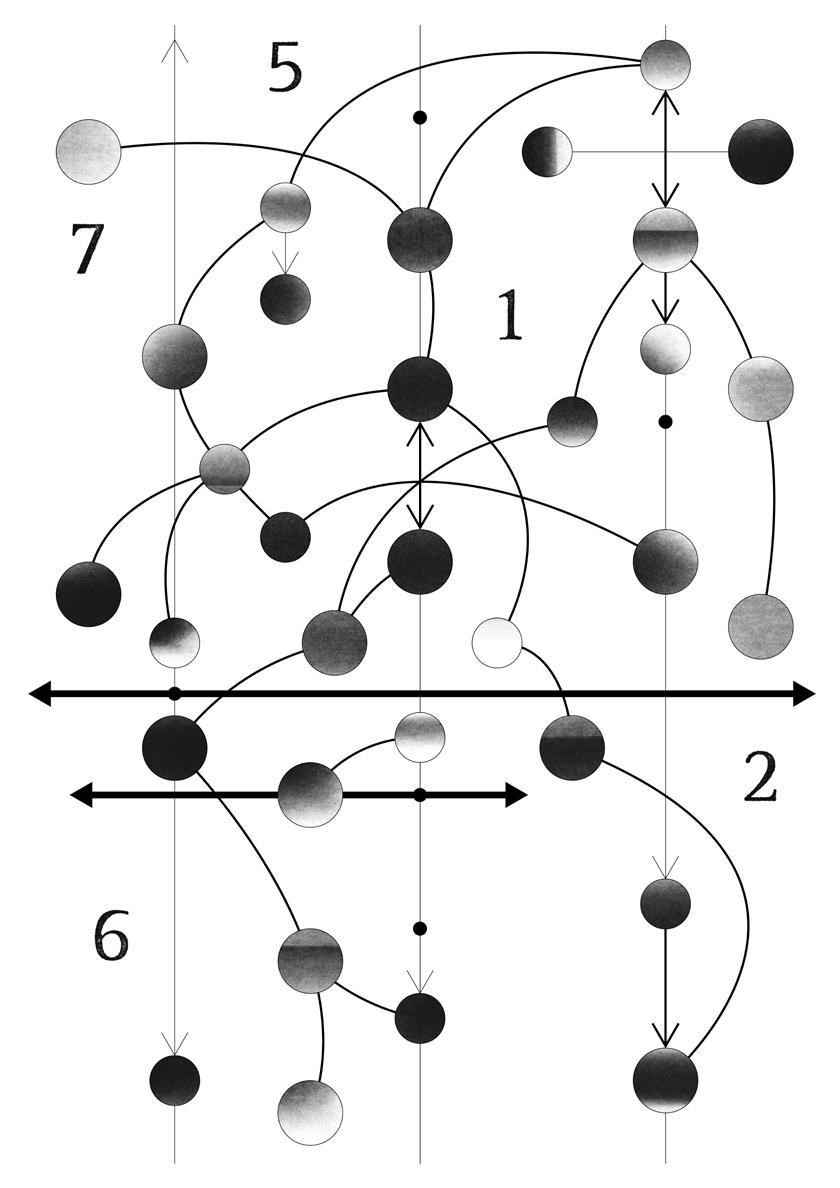

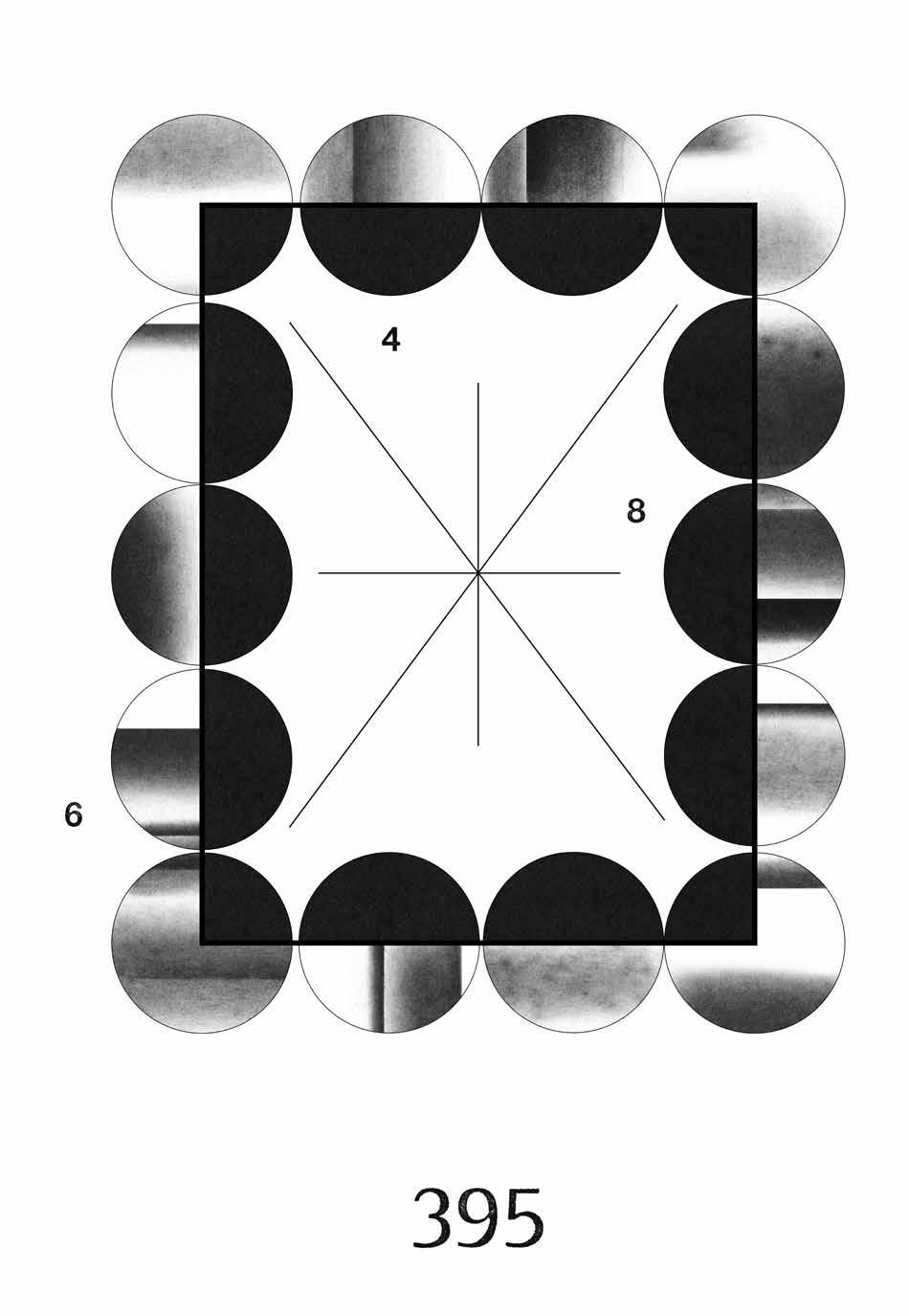

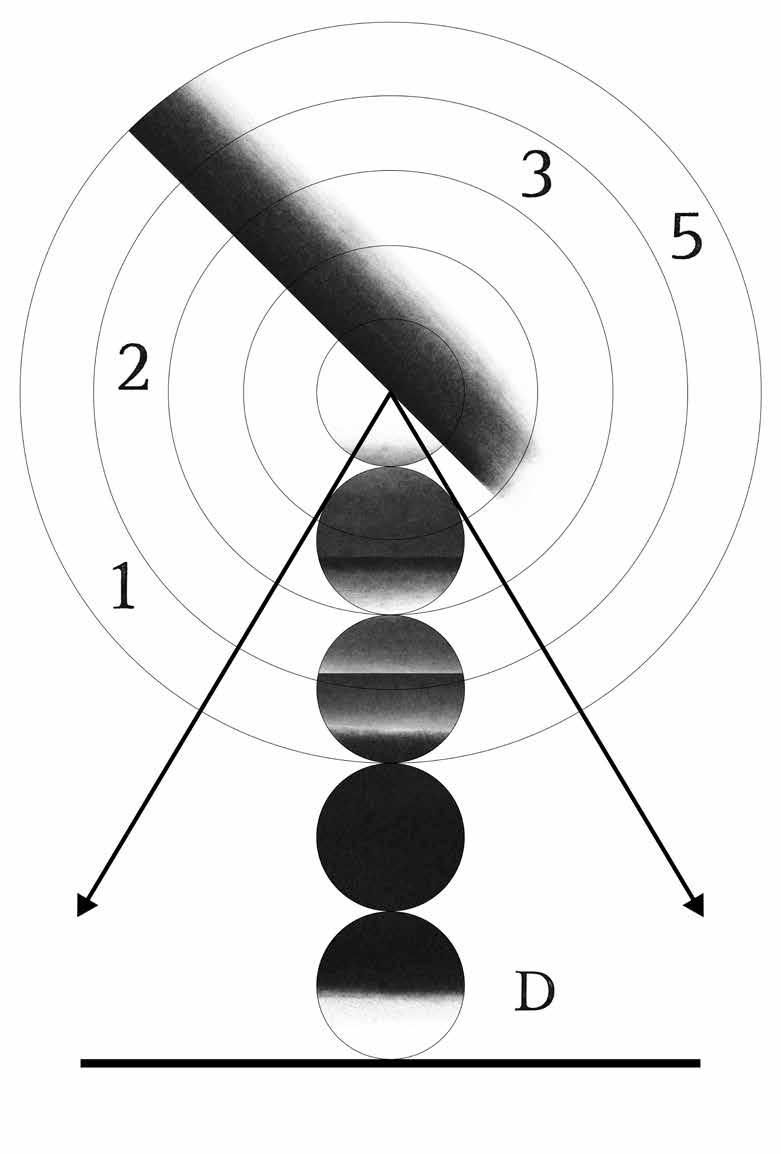

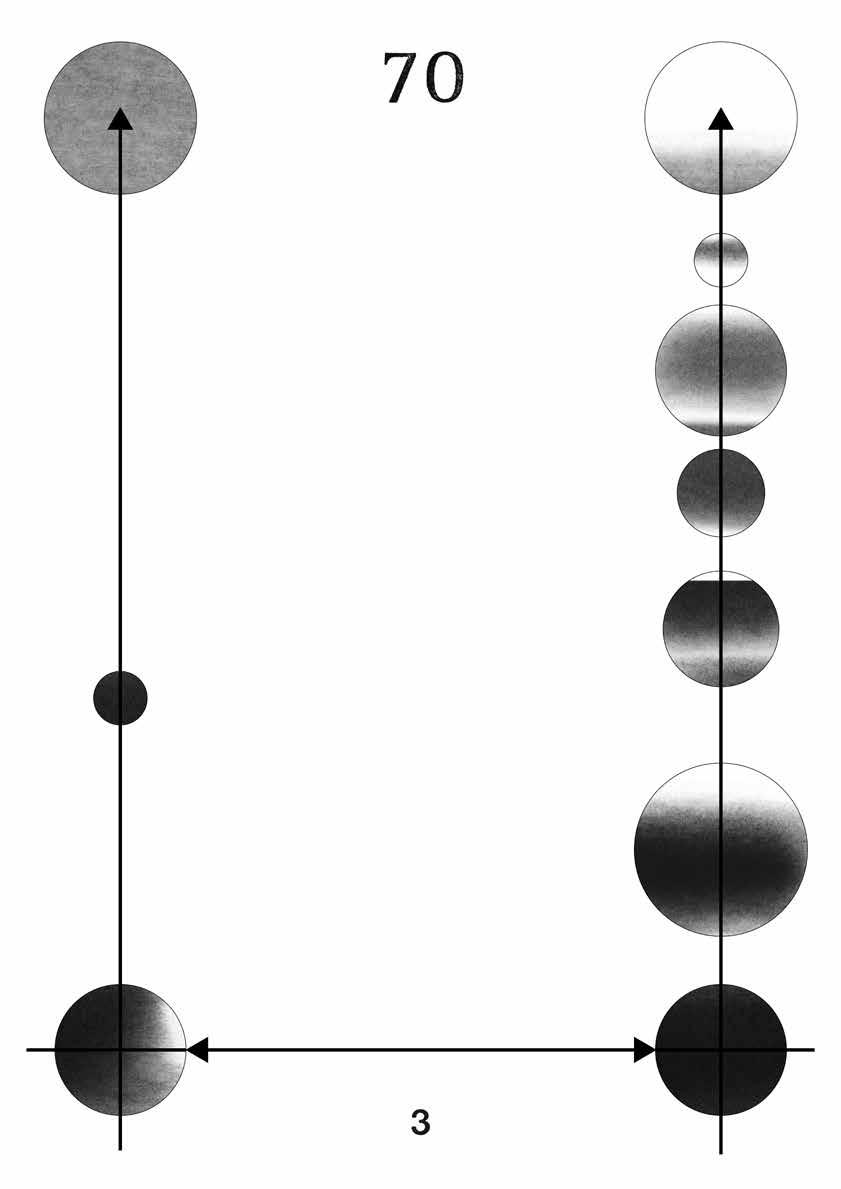

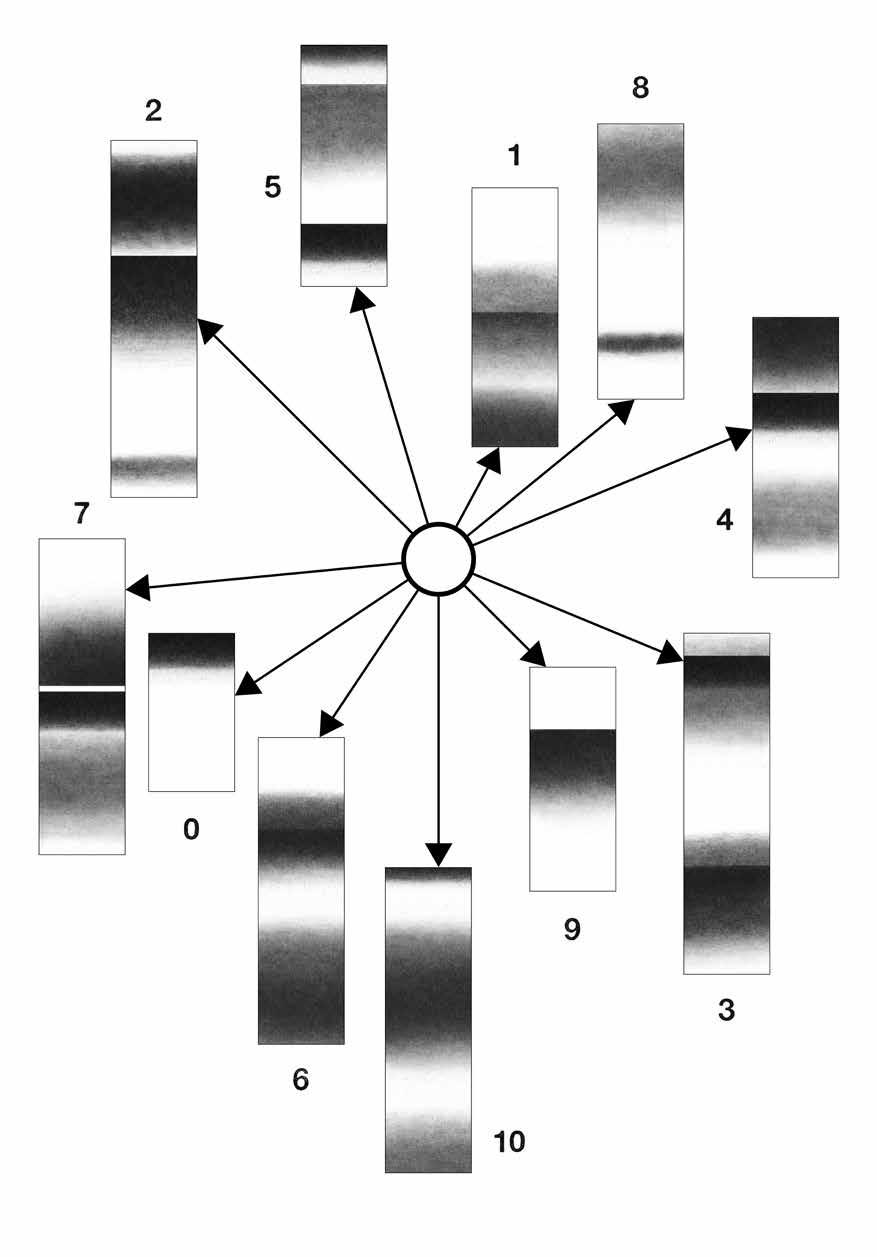

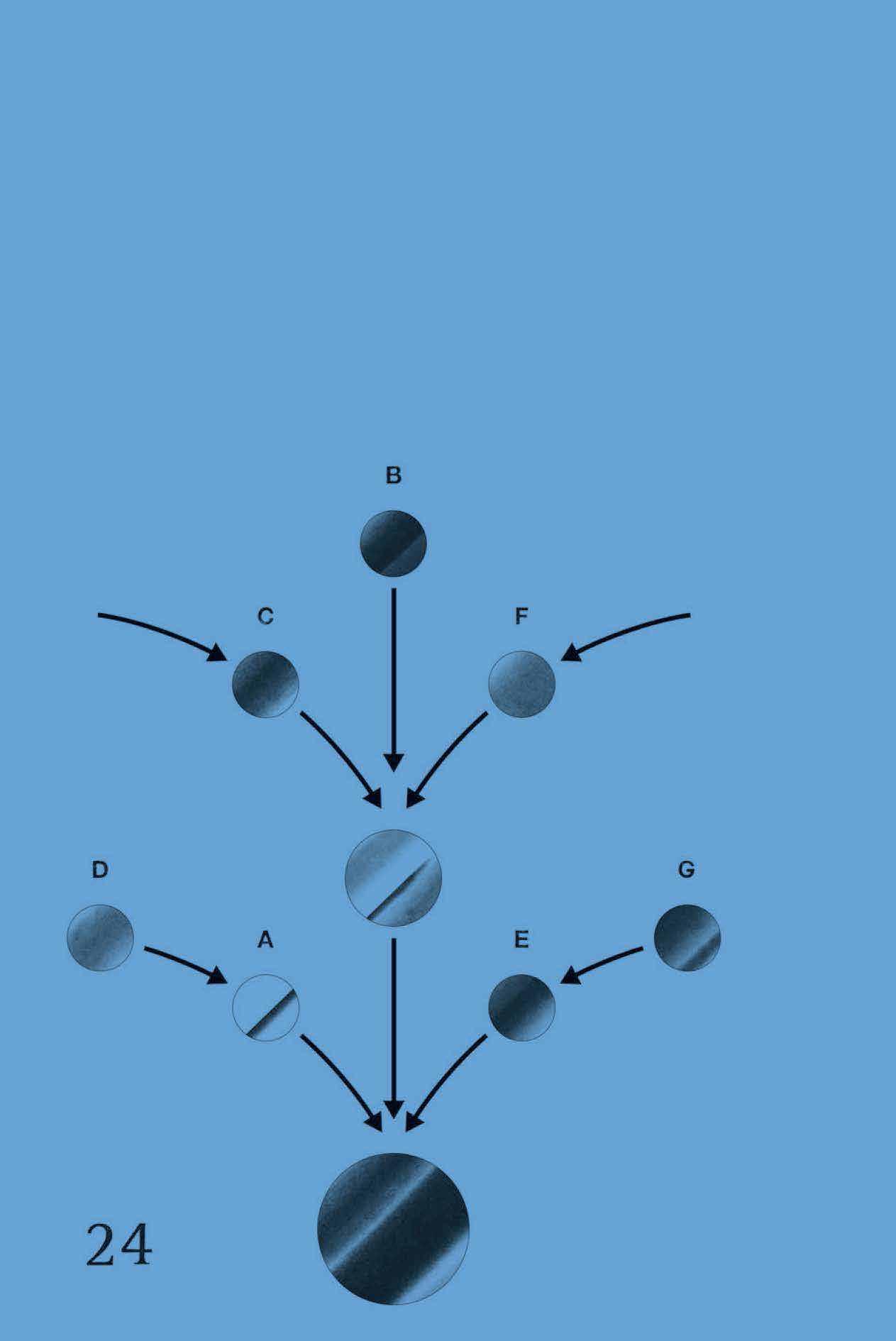

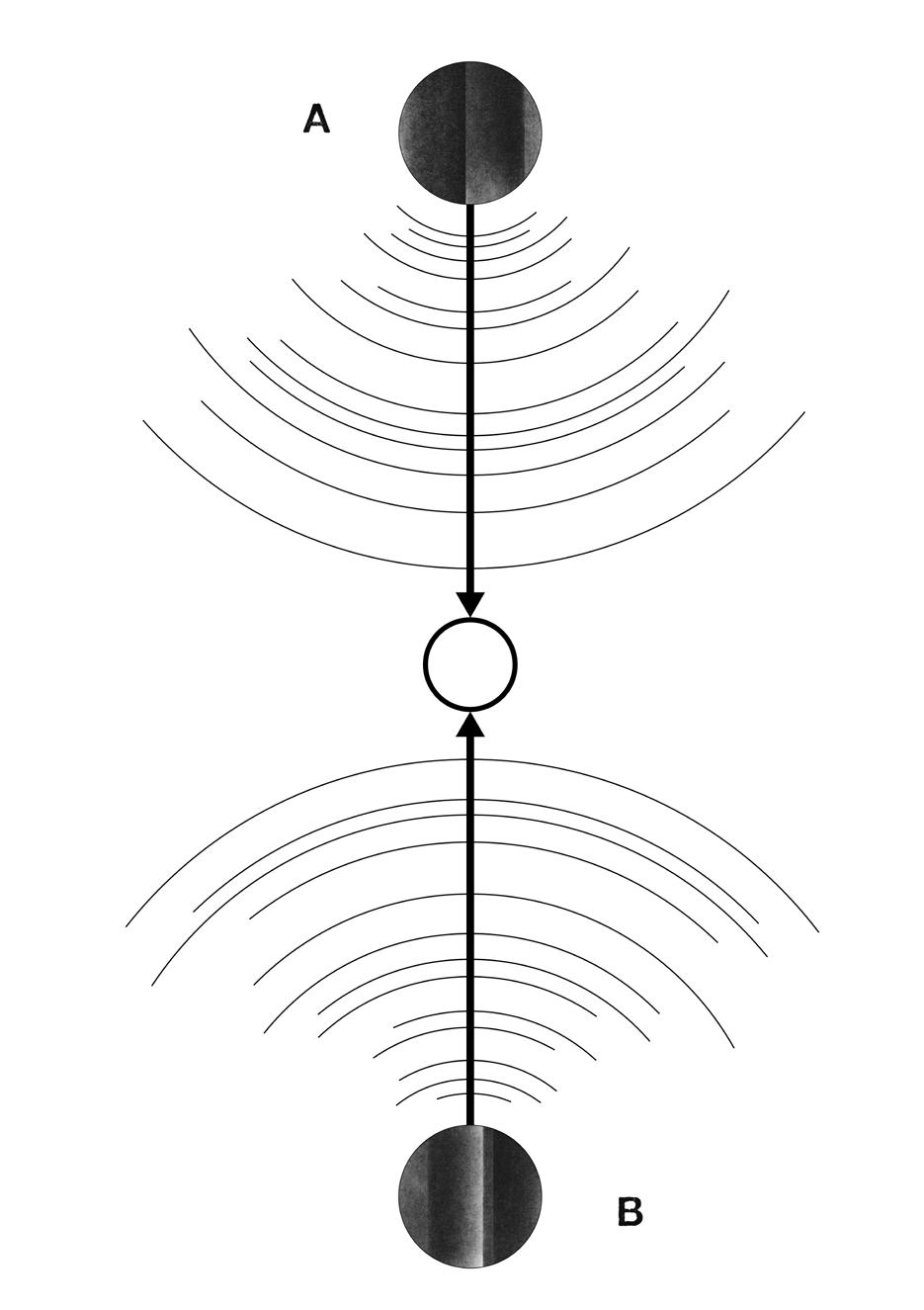

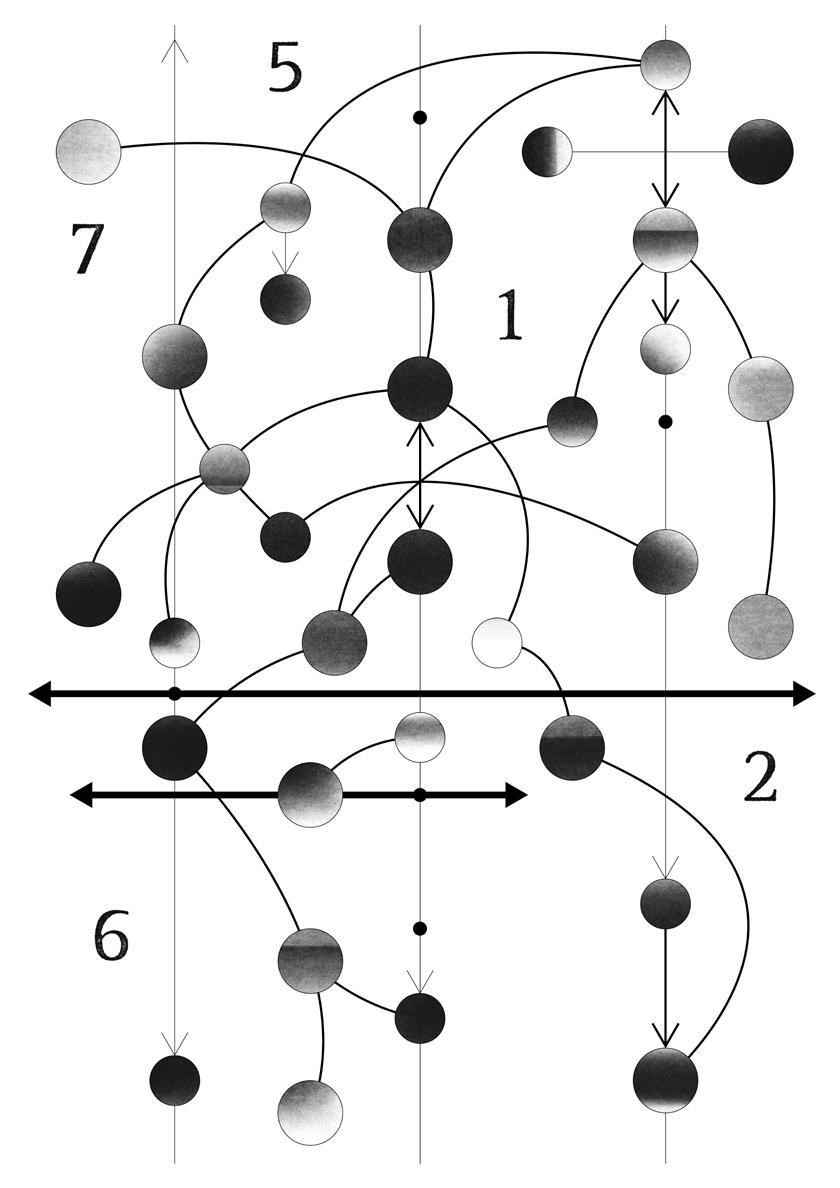

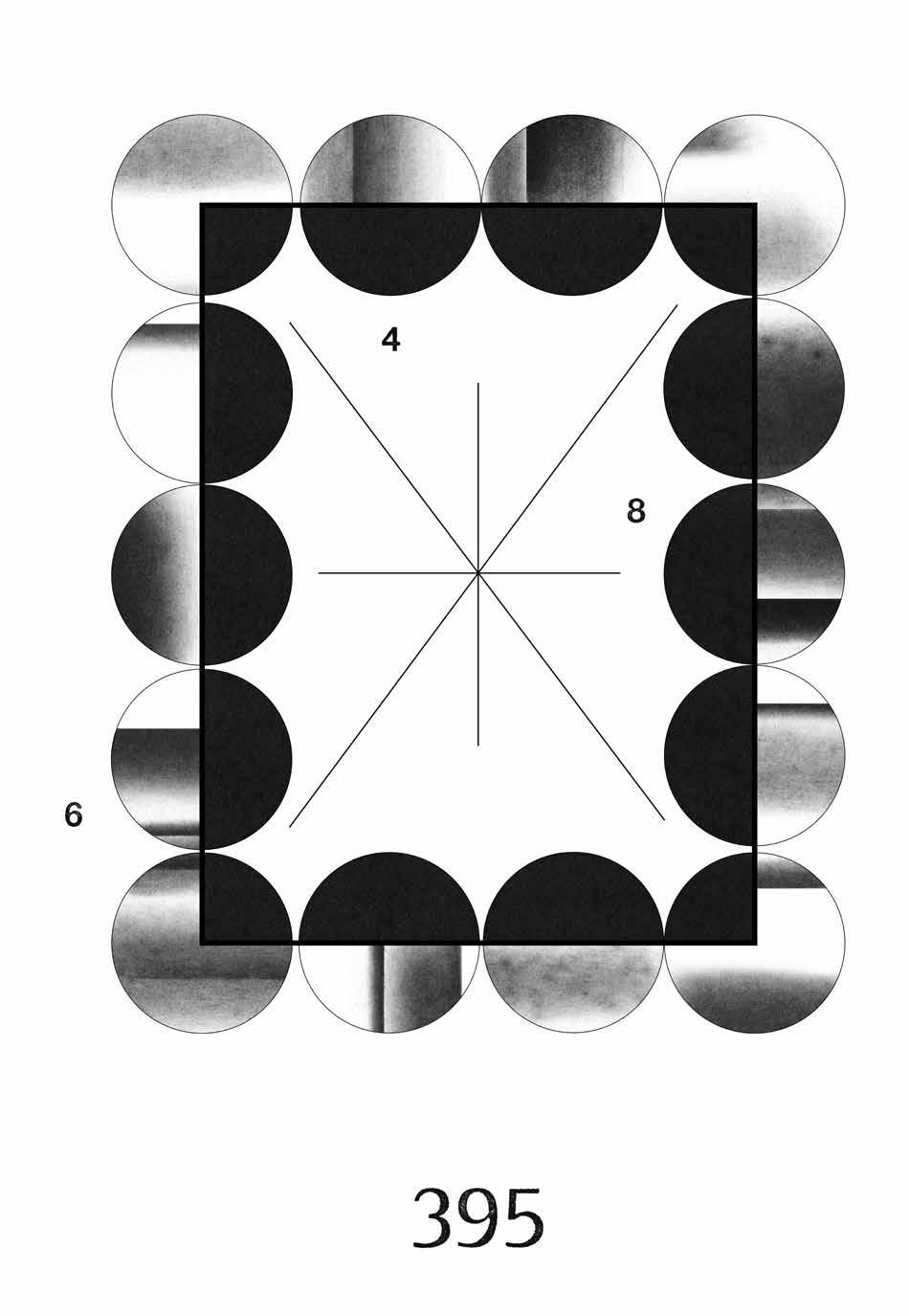

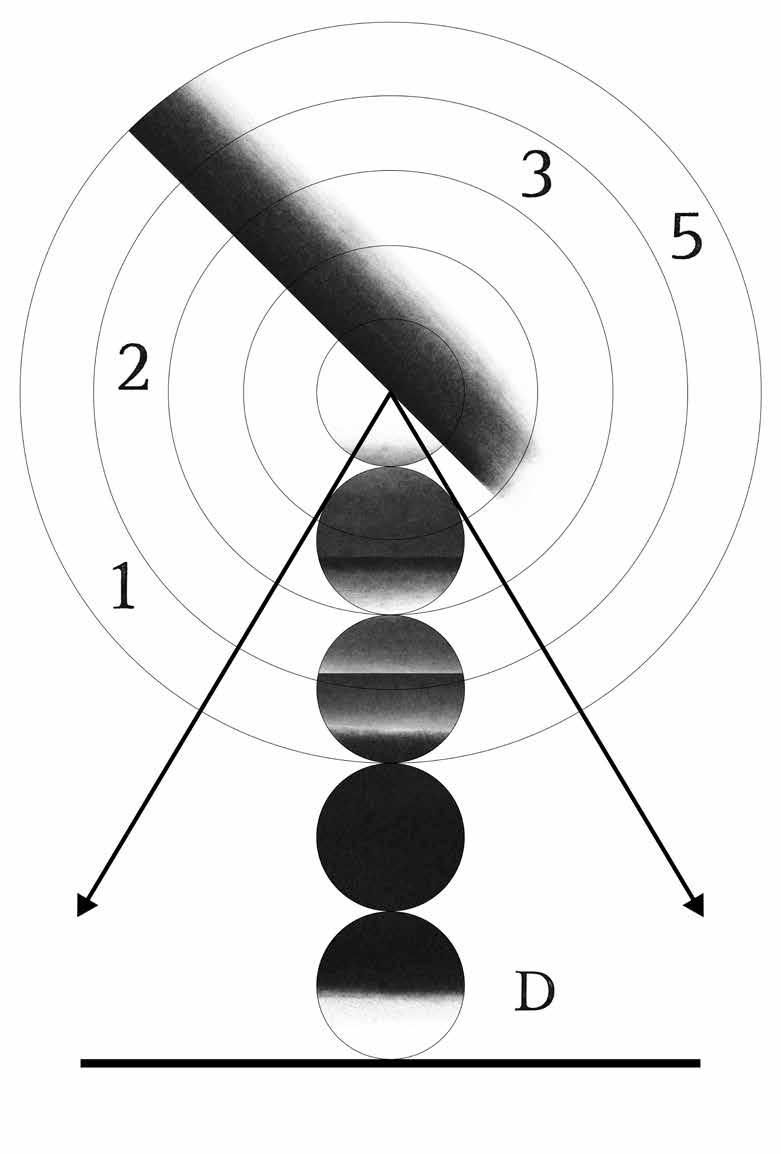

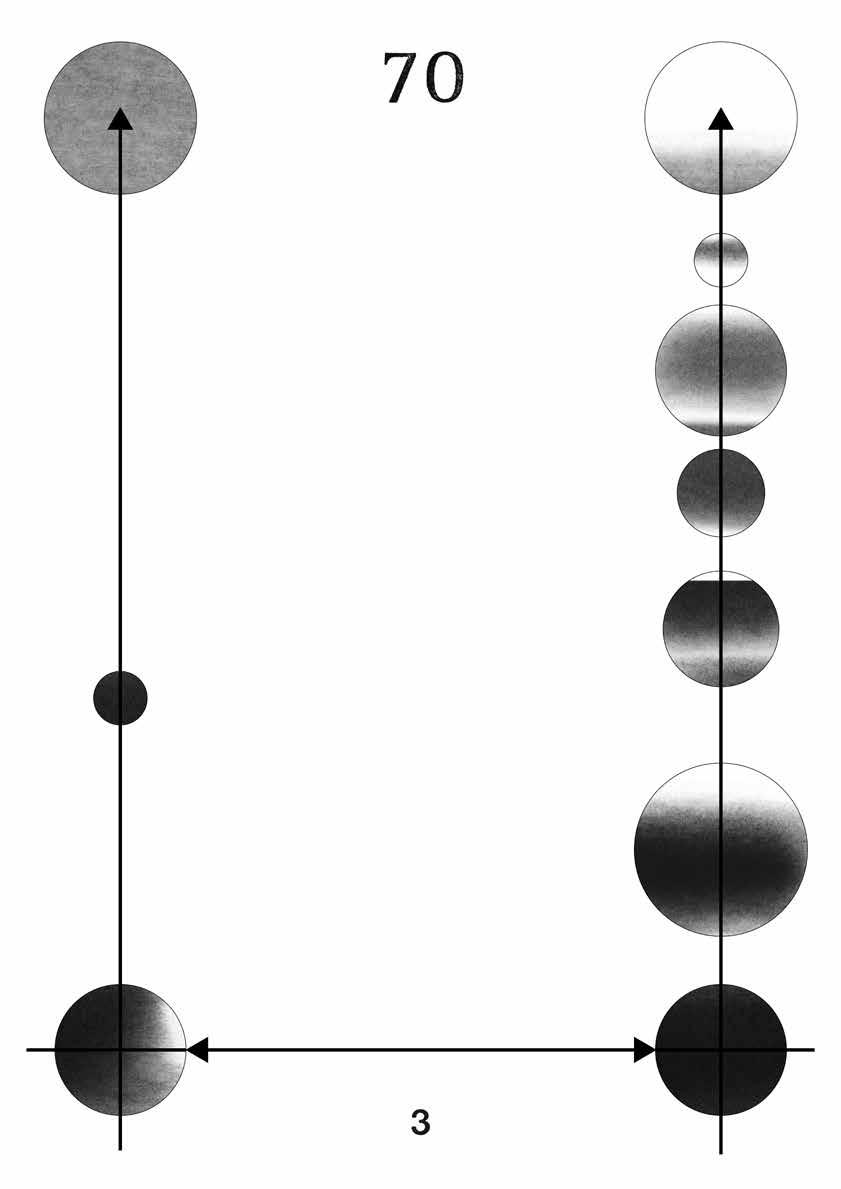

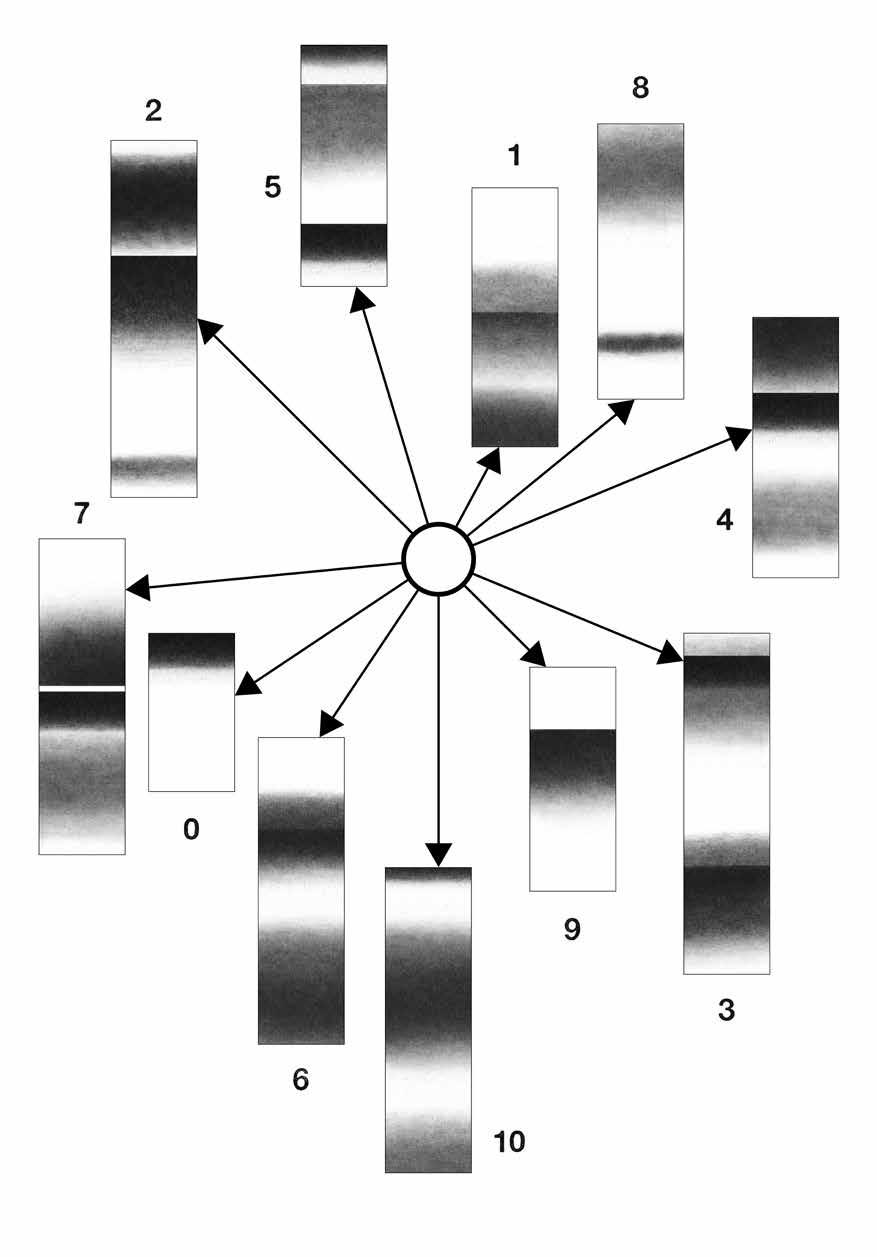

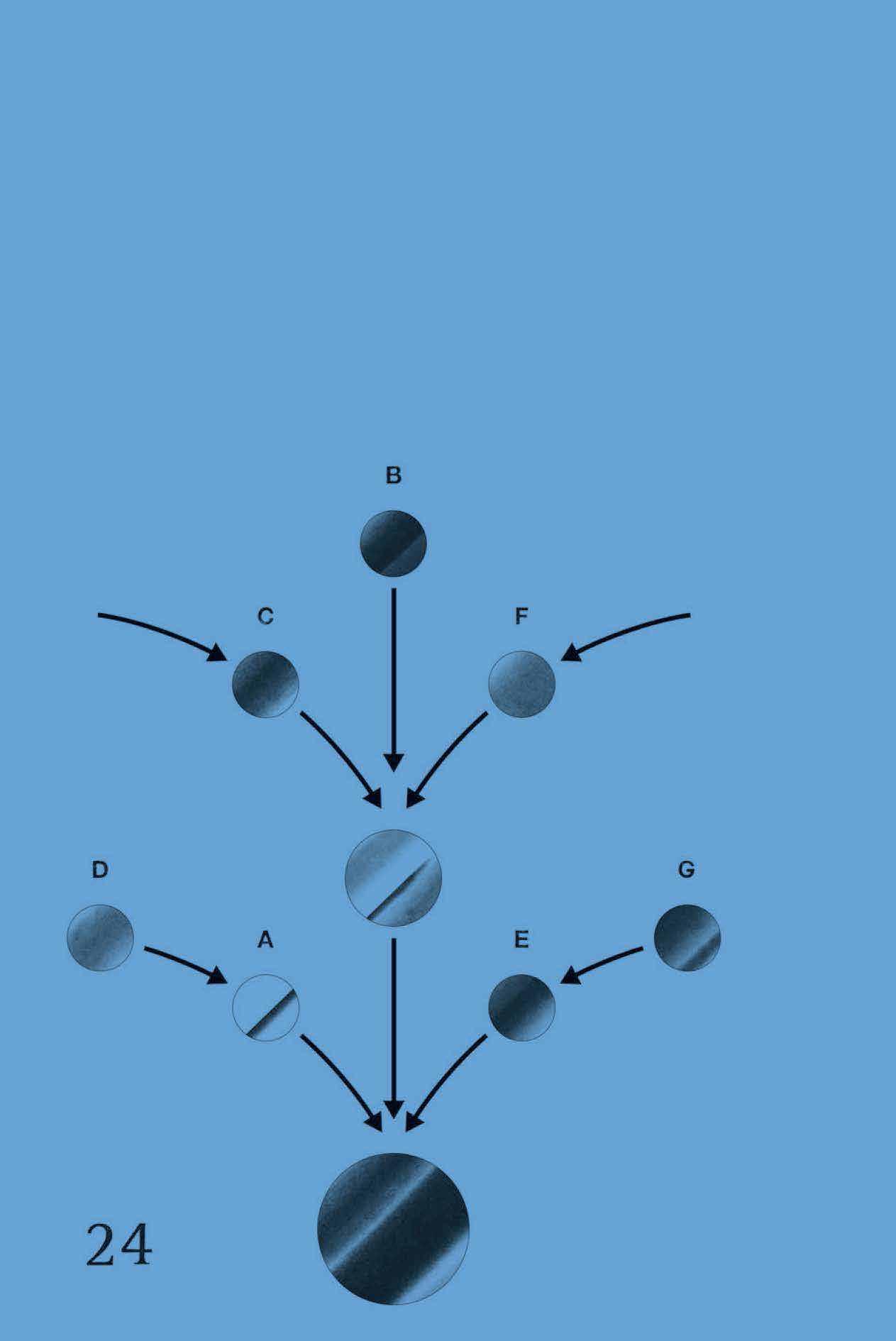

In ihrer Arbeit untersucht die Künstlerin Daria Chernyshova, wie sich Glauben bildet und verändert. Das zentrale Element jedes Werks ist die Komposition, eine ausbalancierte Zusammenstellung klarer geometrischer Formen und Muster, die als Abstraktionen sozialer Mechanismen gelesen werden können. Wir und alles um uns herum sind ständig im Wandel.

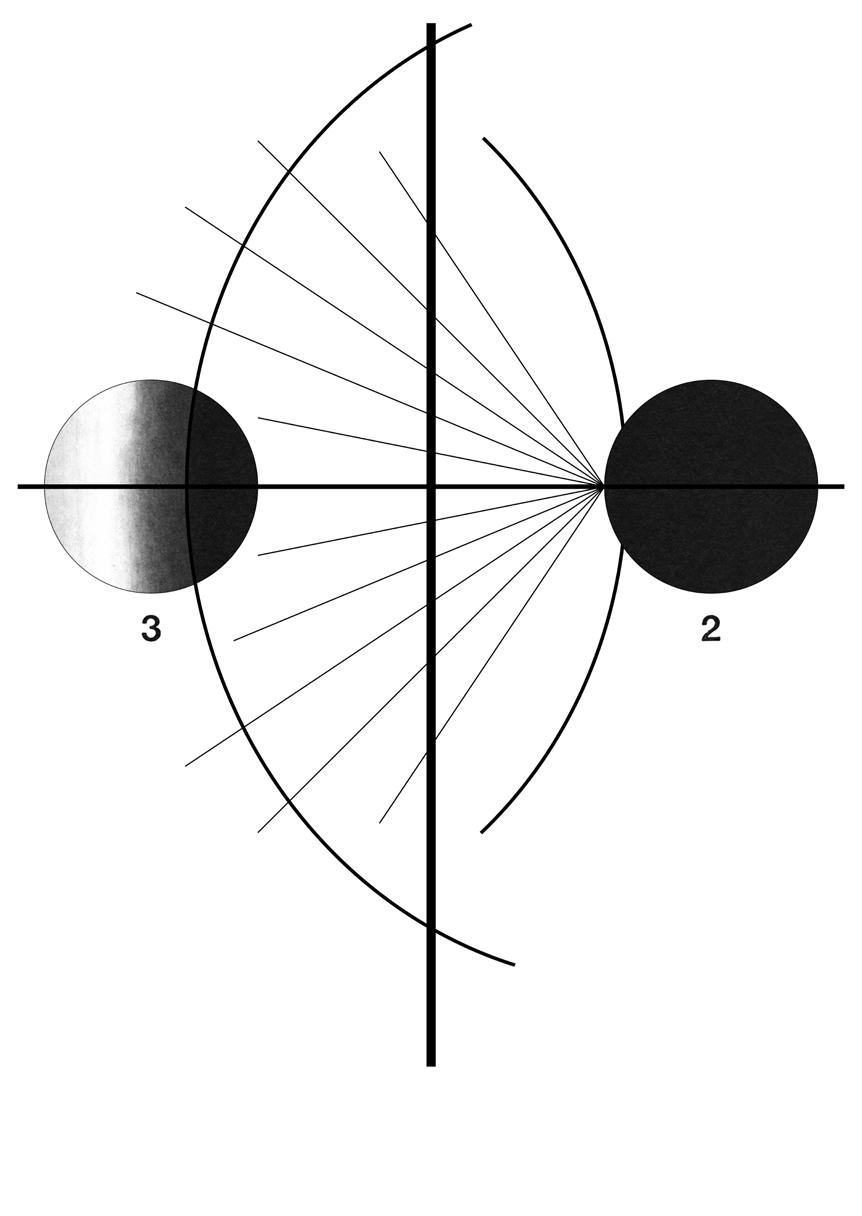

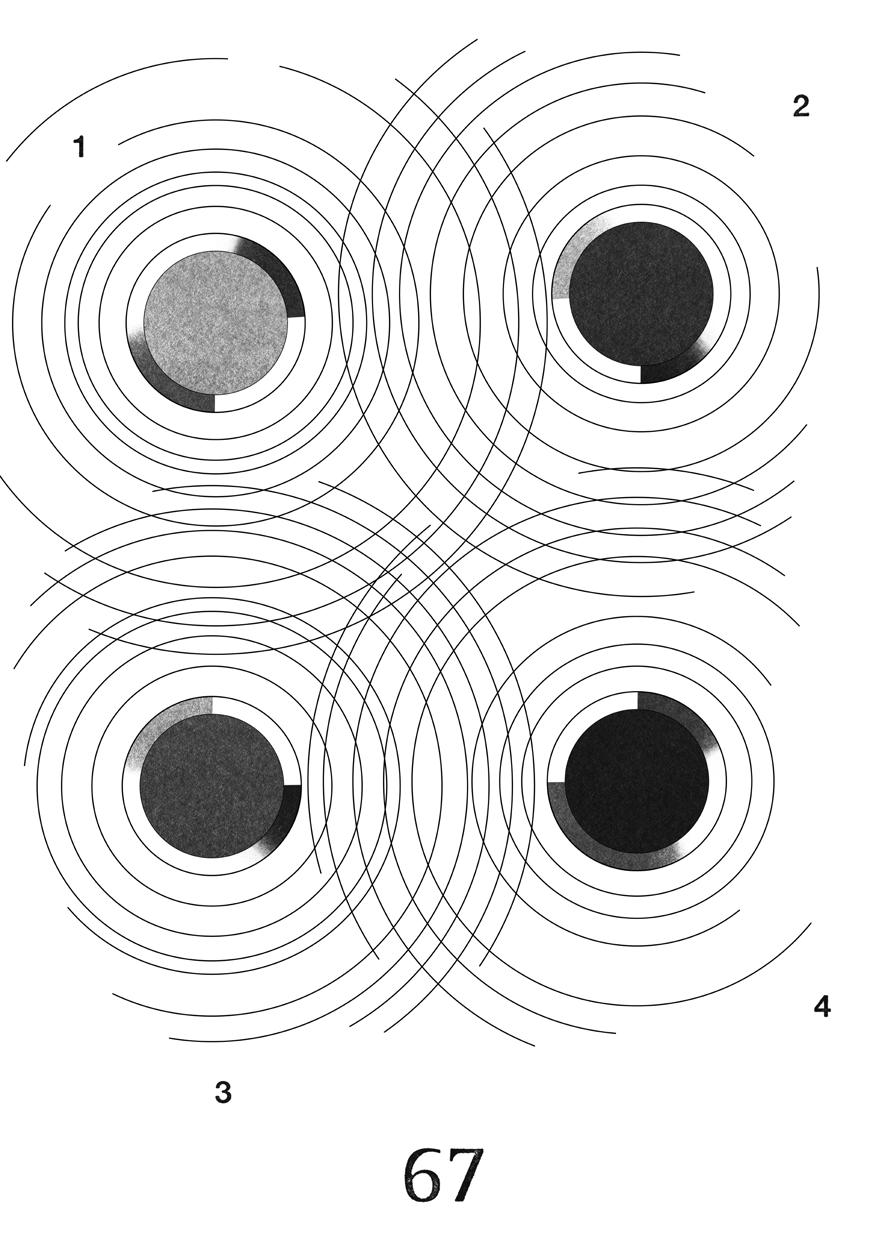

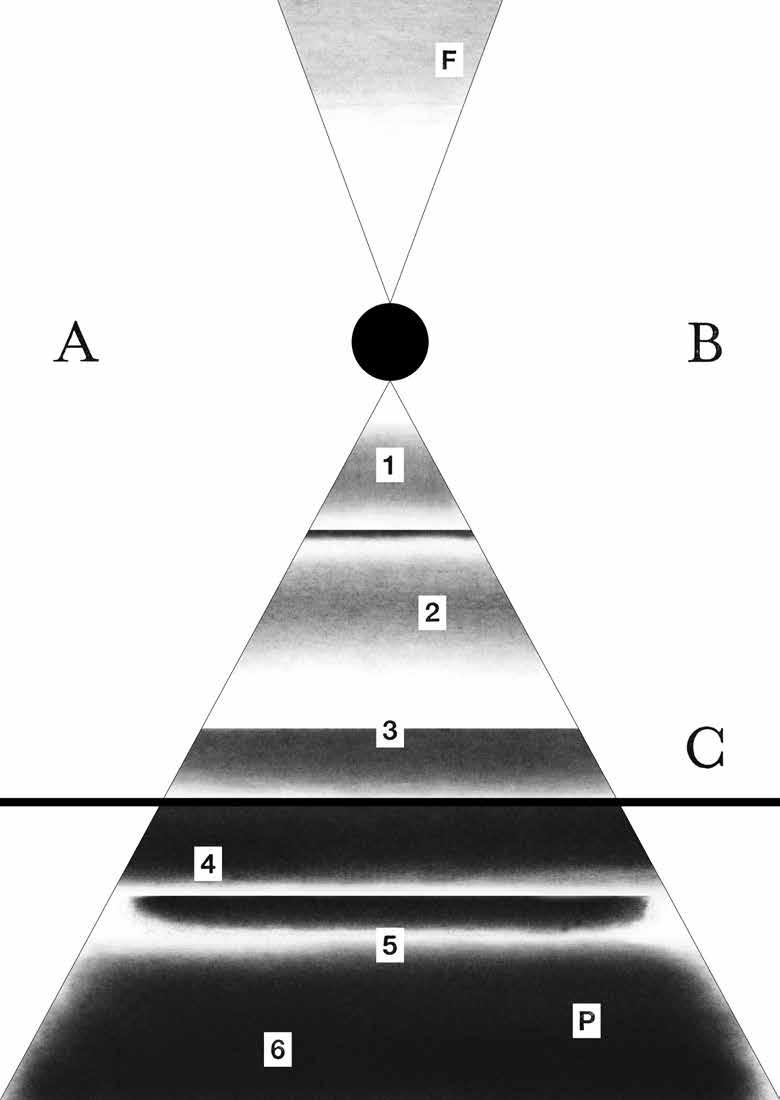

In her work, artist Daria Chernyshova explores the processes of how beliefs form and shift. The central aspect of each piece is the composition, a balanced assembly of rigid geometric shapes and patterns that can be read as an abstraction of social mechanisms. We and everything around us are in constant flux.

11 fortytwomagazine — № 6

Experts

Daria Chernyshova 12 fortytwomagazine — № 6

fortytwomagazine — № 6 Pia Lamberty

Interview with Pia Lamberty, Managing Director of the non-profit Center for Monitoring, Analysis and Strategy

“A belief in conspiracies is not something that can be cured”

13

»Den Glauben an Verschwörungen kann man nicht wegtherapieren«

I Verschwörungsglaube

an eine »gerechtere Welt«: Also dass Menschen, die Gutes tun, auch Gutes widerfährt. Im Umkehrschluss bedeutet das nämlich, dass Menschen, denen Schlechtes widerfährt, etwas Schlechtes getan haben müssen. Das klammert strukturelle Ungleichheiten aus. Auch bei Verschwörungsideologien geht es nicht um strukturelle, gesellschaftliche Ungerechtigkeit. Stattdessen glauben ihre Anhänger an die Existenz abgrundtief böser Einzelpersonen – und wenn man sich ihrer nur entledigt, ist die Gesellschaft eine gute. Das kann Gewalt provozieren.

Das bedeutet natürlich nicht, dass jede Person, die Yoga macht oder Homöopathie nutzt, eine Gefahr für die Demokratie ist. Man sollte sich aber bewusst sein, dass man vielleicht schneller mit problematischen Positionen in Kontakt kommt, als einem lieb ist.

Conspiracy narratives are not a new phenomenon: be it historical antisemitism or witch burnings, the inclination to believe in conspiracies has a firm place in human history. In an interview with fortytwomagazine, psychologist Pia Lamberty explains when we are susceptible to such narratives, why it has nothing to do with intelligence and how to talk to conspiracy ideologues.

Interview: Eliana Berger

Ms Lamberty, a friend of mine recently tried to explain to a “flat-earther” why the Earth is not a disk using arguments from physics. It didn’t work. Why not?

People with an ideology are not interested in rational arguments. Their focus lies on confirming their own worldview. And to a degree we are all like that. If I tell you that there is supposed to be a thunderstorm tomorrow, you will probably believe me, at least if the weather forecast agrees as well. But if I tell you that it will literally rain cats and dogs tomorrow, then that does not align with your worldview. You will probably think to yourself: What nonsense is Pia Lamberty talking about?

18 fortytwomagazine — № 6 42 Pia Lamberty DE Conspiracy Narratives

“People with an ideology are not interested in rational arguments”

EN

Starting from yourself helps you understand why it is so difficult to be confronted with things that are diametrically opposed to your own worldview. It takes a lot of persuasion and trust to get someone to change their mind. You have to be aware of that.

What would be the best way to proceed?

It’s difficult when a person is not willing to reflect. But it’s worth looking at where the inconsistencies in their belief system lie, where the cracks are. You can try to ask questions that disrupt the basic assumptions of the conspiracy theory: So you think 9 / 11 was staged by the US government? How was that supposed to have happened? Do you really think it’s possible that everyone kept quiet, that nobody said anything to anyone?

But it’s even more important to find questions that are relevant to the people themselves. If you are close, you can think about whether there are underlying reasons you need to address. But these are lengthy processes, and how they pan out also has a lot to do with how open someone is to changing their mind.

Before we delve further into the topic: How do you define a conspiracy narrative?

A person who believes in a conspiracy narrative thinks that the ruling elites have a secret plan and want to harm society. We speak of a conspiracy ideology when the whole becomes a worldview; when one interprets the whole world as a great conspiracy and that view strongly influences one’s behaviour.

What factors make people susceptible to falling for a conspiracy narrative? It’s not so much about falling for it. Usually it ties in with an existing worldview. A lot of people who start believing in a conspiracy narrative already assumed that “the others” are malicious and out to harm you. This can be further reinforced in groups that share a similar worldview, where you are confronted with increasingly radical ideas.

However, there are certain personality traits that make it more likely that a person might believe in a conspiracy narrative. For example a strong need to be unique; the belief that only you know what’s really going on. Collective narcissism also plays an important role. When this happens, you believe that your own group is

19 fortytwomagazine — № 6 42 PL 42 PL 42 PL Conspiracy Narratives

“In crisis situations people are open to conspiracy narratives”

“People who tend to avoid problems rather than deal with them are also more likely to believe in conspiracies”

only accessible to a small number of enlightened individuals. What is dangerous about both is their anti-democratic core. In the case of esotericism, this is reflected in its strong focus on the satisfaction of the individual and in a leadership cult of personality. What is also alarming in this context is the belief in a “fairer world”: Good things happen to people who do good things. Conversely, this means that when bad things happen to people it must be because they have done something bad. This does away with structural inequalities. Conspiracy ideologies are also not about structural social injustice. Instead, their adherents believe in the existence of egregiously evil individuals and if we just get rid of those people, then society will be good. This can incite violence. This obviously doesn’t mean that everyone who does yoga or uses homeopathy is a danger to democracy. Although you should be aware that you may come across problematic viewpoints more easily than you’d like to.

Die Sozialpsychologin Pia Lamberty ist Geschäftsführerin des gemeinnützigen Center für Monitoring, Analyse und Strategie (CeMAS), das interdisziplinäre Expertise unter anderem zu Verschwörungsideologien und Desinformation bündelt.

Social psychologist Pia Lamberty manages the non-profit Center for Monitoring, Analysis and Strategy (CeMAS), which pools interdisciplinary expertise on topics such as conspiracy ideologies and disinformation.

22 fortytwomagazine — № 6 Conspiracy Narratives

EN

23 fortytwomagazine — № 6 Daria Chernyshova

»Immer mehr senschaftler:innen unterstützen die Demokraten«

Dr Alexander Kaurov

24 fortytwomagazine — № 6

Der Glaube an die Wissenschaft

mehr Wissenschaftler:innen unterstützen Demokraten«

Interview with Dr Alexander Kaurov, Department of the History of Science at Harvard University.

25 fortytwomagazine — № 6

Dr Alexander Kaurov

II

“More and more scientists support Democrats”

Während der COVID-19-Pandemie war der Ruf nach mehr Vertrauen in die Wissenschaft allgegenwärtig. Aber wie können wir den Glauben an die Wissenschaft aufrechterhalten, wenn wir sehen, dass sich Expert:innen irren und politische Meinungen unsere Wahrnehmung von Fakten immer entscheidender beeinflusst? Dr. Alexander Kaurov, wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter in der Abteilung für Wissenschaftsgeschichte an der Harvard University, sucht nach Antworten und findet sie in Form von Daten. Er glaubt nicht an Wissenschaft als eine Ansammlung von Fakten, sondern als einen Prozess des Findens, Verstehens und gelegentlichen Korrigierens. Im Allgemeinen ruft er dazu auf, sich mit Wissenschaft und der ihr zugrundeliegenden Methodik vertraut zu machen. Aber er erklärt auch, wie wichtig das Vertrauen in die Wissenschaftler:innen ist.

Interview: Jonas Hermann & Lena Kronenbürger

Sie sind Wissenschaftler. Bedeutet das, dass Sie an die Wissenschaft glauben? In einem normalen Gespräch würde ich ja sagen. Aber der Begriff »Wissenschaft« ist zu weit gefasst, um eine solch einfache Antwort geben zu können. Genauer wäre es zu sagen, dass ich an wissenschaftliche Methoden glaube. Wissenschaftliches Arbeiten ist eine Möglichkeit, komplexe Probleme anzugehen, indem man Fakten durch Tests und Experimente objektiv feststellt. Es ist eine Praxis, also eine Art und Weise, wie man etwas tut. Wissenschaftliches Arbeiten hilft dabei, sich ein Urteil über eine Hypothese zu bilden, indem man die Beweise auswertet und sie dann entweder glaubt oder nicht. Oft kommt man dabei zu ambivalenten Schlussfolgerungen.

»Immer mehr senschaftler:innen unterstützen die Demokraten«

»Aufgrund des mangelnden Verständnisses dessen, was Wissenschaft ist, reduzieren viele Menschen das Vertrauen in die Wissenschaft auf blindes Vertrauen in alles, was das Etikett ›Wissenschaft‹ trägt«

Wo wir schon von Unsicherheit sprechen: Glauben wir manchmal zu naiv an die Wissenschaft?

Aufgrund des mangelnden Verständnisses dessen, was Wissenschaft ist, reduzieren viele Menschen das Vertrauen in die Wissenschaft auf blindes Vertrauen in alles, was das Etikett »Wissenschaft« trägt – ohne tiefere Kenntnis der zugrundeliegenden Beweisführung. Hier ein ganz banales Beispiel: Wenn Sie

DE 26 fortytwomagazine — № 6 Der Glaube an die Wissenschaft

42 Alexander Kaurov 42 AK

mehr Wissenschaftler:innen unterstützen Demokraten«

27 fortytwomagazine — № 6

fortytwomagazine — № 6 32 Daria Chernyshova

beliefs selection of

are

in the end

just a

narratives

decide whether to trust someone or not partially on a subconscious level. Moreover, recent research shows that political affiliation is becoming increasingly important. You are more likely to listen to someone who is on your side of the political spectrum.

How important is political affiliation regarding the public’s trust in science? For building any trust, not only in science, it becomes more and more crucial to have the messenger match the recipient based on political leanings. In the media landscape of the United States, there is a clear separation between left and right-leaning outlets, and their audiences match their political views. Something similar might also happen in academia, though it has not been clear whether there is a substantial amount of right-leaning academics. For this reason, we conducted a study on this.

We used a data-driven approach and analyzed the Federal Election Committee’s open database of donations by individuals. We identified about a hundred thousand scientists and looked at their donation patterns. The result? An increasing number of scientists support Democrats. It’s a strong trend that researchers already knew about, but we could show it in greater detail. Forty years ago, academics were 50 percent left and 50 percent right. And in the United States, historically, the population is also 50 percent left and 50 percent right. But very gradually, academics are becoming more liberal, more left-wing, and donating to Democrats. And now it’s hard to find anybody in academia who contributes to the Republican party. At Ivy League universities, 98 percent of donations go to Democrats.

What are the consequences for society when academia and the media are mostly politically left-wing?

Well, imagine you’re on the right side of the political spectrum. You know from the information sources you trust that the media is mainly left and academia is left. Are you likely to trust any of them? Probably not! So you end up watching right-wing sources of information propagating ideas you agree with. And when you have academics in front of you, you know they’re likely to be left. Therefore, you are less likely to trust them. That was partially the problem with Anthony Fauci.

To illustrate the consequences, we can cite a survey from last year showing that two-thirds of Democrats and one-third of Republicans trust scientists. This is the largest gap in 50 years of surveying. Imagine that I did not believe in science. How would you try to change my mind?

With adults, I wouldn’t even try. With children, on the other hand, you don’t have to do much convincing. I work a lot with children,

36 fortytwomagazine — № 6 DE 42 AK 42 AK 42 AK Believing in Science

“You are more likely to listen to someone who is on your side of the political spectrum”

and they are naturally curious about their surroundings. These days, science is so advanced that it is always around, no matter your interests. If you’re interested in video games, I would tell you that algebra and trigonometry are used to develop video games. So there’s always science, just a step away from you. If you’re interested in rockets, you want to know how they work. Of course, a single person can’t understand and know how everything works, but if you look at a jet engine and understand how it operates, it will familiarize you with the scientific method. Then, when you encounter a problem in biology, you’ll already know approximately how to expand your knowledge in that area within the scientific framework.

“At Ivy League universities, 98 percent of donations go to Democrats”

On your website, you quote the writer Darrel Huff: “If you torture the data long enough, it will confess to anything.” Does that mean you have to trust the person working with the data?

It’s a joke related to people working with data and statistics, but there’s an important message behind it. In science, you must assume that the people you are dealing with have good intentions. That is usually the case, but sometimes it’s not. That’s why scandals occur when someone falsifies data or publishes a paper and becomes famous for a discovery that turns out to be fake. Unfortunately, that happens. Science can survive because, on average, the people who work in science have good intentions and play by the rules. And then there is this minority who disobey the rules but are slowly filtered out of the system, for example, by competent peer reviewers. Sometimes these people climb too high and make it into the media, but sooner or later, their fraud is discovered by honest scientists. The whole scientific endeavor is possible because people, including scientists, have on average good intentions.

37 fortytwomagazine — № 6 42 AK Believing in Science

Dr. Alexander Kaurov ist wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter am Lehrstuhl für Wissenschaftsgeschichte der Harvard University und Gastdozent am Institute for Advanced Studies. Er erforscht, wie Wissenschaft öffentlich wahrgenommen wird.

Dr Alexander Kaurov is a research associate in the Department of the History of Science at Harvard University and a visiting lecturer at the Institute for Advanced Studies. He investigates the public’s perception of science.

40 fortytwomagazine — № 6 Daria Chernyshova

Glaube an das Finanzsystem

»Die Währung an sich ist wertlos«

Interview with Nicola Gennaioli, Professor of Finance at Università Commerciale Luigi Bocconi in Milan, Research Fellow at the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI)

fortytwomagazine — № 6

III

Nicola Gennaioli

41

“The currency per se is worthless”

One domain of the financial markets that is widely associated with expertise is the stock market. The value of a stock reflects the anticipated development of a company. It is the expected value of the future, not the present. So are we actually trading beliefs and not stocks?

Yes, it is in the very nature of the economic system since there is a large category of goods that do not yield value yet but will or at least hope to do so in the future. And because the future is inherently uncertain, the way in which we set the price for these goods depends on our beliefs about the future.

To what extent are instruments like stocks or loans a mechanism to deal with the high degree of uncertainty that economic actors face?

Well, these instruments have an important purpose. They allow you and me, and everybody else, to participate in the economy but also the system itself to get insured against certain risks. My grandfather was a farmer in central Italy, for example. He was always concerned about the weather, because bad weather would mean a bad harvest and not enough money to feed the family. That changed when he was able to borrow money from the bank in bad years to pay it back in good years. So the risk of a great disaster was significantly reduced. The financial sector does a great service to the economy by helping people to spread the risks that they cannot afford to bear.

Not only do consumers put their faith in the economy, but the economy must put its faith in consumers, and so loans are given in the belief that they will be repaid.

Speaking about money: A Dollar, a Euro, or a Yen derives its value through the shared collective belief that it has the same value for all participants in the economy. Do shared beliefs form the core of an economic system?

There are some markets in which having common beliefs is very relevant, and there are other markets in which they are less so. For instance, in currency markets, it is indeed important that we all believe that a currency is still going to have a value tomorrow. Because if people suddenly stop believing in the value of a currency, it is going to be worthless tomorrow since they are not going to accept it for payment anymore. The currency per se is worthless, it’s just pieces of paper. It is the common belief that attributes value to it. So in the case of currencies, the shared belief that the currency is going to be of value is critical. That’s why we have central banks that give credibility to the value of a currency and therefore strengthen the common belief. When there is no such intermediary, as is the case of cryptocurrencies, then the common belief in

50 fortytwomagazine — № 6 Beliefs in the Financial System EN 42 NG 42 NG 42 NG

“Even if there is expertise in the system, it doesn’t necessarily mean that it gets optimally utilized”

its value might at times be stronger and at times weaker causing a lot of volatility, instability, and anxiety. Under which circumstances are common beliefs less important? Let’s look at the art market and, for example, at a Picasso painting. Maybe some people don’t like it, but as long as I like it, I’m willing to pay whatever the market price for a Picasso is. Actually, the more I like the Picasso, the more I would like others not to like the Picasso. Because in that case, I would be able to buy the Les Demoiselles d’Avignon for a lower price. These are markets in which I get an intrinsic value for a good. Of course, the prices will go up if everybody believes that Picasso was a fantastic painter, but the common nature of beliefs is less important for the survival of the market.

Dr. Nicola Gennaioli ist Professor für Wirtschaftswissenschaften an der Università Commerciale Luigi Bocconi in Mailand. In seinem Buch A Crisis of Beliefs (2018) befasst er sich mit den psychologischen Mechanismen der Finanzkrise 2008.

Dr Nicola Gennaioli is professor of finance at Universita Commerciale Luigi Bocconi in Milan. In his book A Crisis of Beliefs (2018), he looks at the psychological mechanisms at work in the financial crisis 2008.

42 NG 51 fortytwomagazine — № 6

Beliefs in the Financial System

54 fortytwomagazine — № 6 Daria Chernyshova

IV Placeboeffekt

»Wir haben quasi eine eigene Apotheke im Kopf«

“We have our own pharmacy in our heads”

Interview with Dr Katja Wiech, Neuroscientist at the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences at the University of Oxford

fortytwomagazine — № 6

Dr Katja Wiech

55

Gabe es methodische Zweifel an der Studie? Das nicht. Die Kritik war tatsächlich eher gesellschaftspolitisch. Es war wirklich unglaublich. Ich habe davor noch nie so eine kontroverse Studie durchgeführt, wobei ich sie auf den ersten Blick gar nicht kontrovers fand. Aber Religion ist ja an sich oft schon Sprengstoff in der öffentlichen Debatte. Dass wir in diesem speziellen Kontext tatsächlich positive Effekte nachweisen konnten, hat eben alle möglichen Fragen aufgeworfen.

»Ich glaube, dass die Erfahrung von Selbstwirksamkeit für Schmerzpatienten extrem hilfreich sein kann«

Ließen sich ähnliche Effekte – also nicht nur von Religion, sondern von kultureller Prägung allgemein – in der Schmerztherapie einsetzen? Absolut, ich sehe da riesiges Potential. Wenn wir solche Effekte aktiv nutzen könnten, ließen sich auch viele Probleme vermeiden, die von hochdosierten aktiven Präparaten kommen, also starke Nebenwirkungen, Abhängigkeiten usw. Ich glaube, dass diese Erfahrung von Selbstwirksamkeit für Schmerzpatienten extrem hilfreich sein kann. Wir haben quasi eine eigene Apotheke im Kopf. Wenn wir die systematisch aktivieren könnten, wäre das ein riesiger Vorteil.

Did you know that it is not only sensory perception or actual tissue damage that triggers pain perception? And that there are certain areas of the brain that exert control over the painrelevant parts and thus on our perception of pain? Dr. Katja Wiech from the Pain & Mind research group at the University of Oxford explains how beliefs influence our perception of pain in the brain. She looks at belief in general, in the sense of presuppositions, but also in a religious and cultural sense. To this end, Wiech tells us about two revealing studies: one on the contribution of the placebo effect to the efficacy of a common painkiller and one on the impact of religious socialisation on pain perception.

60 fortytwomagazine — № 6 42 KW 42 KW EN Placebo Effect

Interview and translation: Jonas Hermann

A majority of the medication we take in the course of our lives has to do with pain relief. That already starts with aspirin when we have a cold. What does pain have to do with belief?

When it comes to pain, most people would probably say: either something hurts or it doesn’t hurt. Belief has nothing to do with that, it shouldn’t play a role.

But the interesting thing is that belief does have something to do with pain. The scientific view has changed a lot here. For example, as a clinical neuroscientist, I look at how pain is processed in the central nervous system. My research concerns the question of how we evaluate, process, rate, and sometimes ignore information in the brain and then compile it into information that is perceived as pain.

So how would you define pain?

Until not too long ago, the prevailing notion was that pain was the perception of stimuli resulting from tissue damage. This definition has extended in recent years. Pain can also be based solely on the belief that there is tissue damage, even if there is none. Sometimes you don’t find anything in patients that physically indicates that they are in pain. That is why pain is also a subjective perception. The role of belief in medicine is discussed publicly mainly in connection with the so-called placebo effect, for example with regard to homoeopathy. How do you see the placebo effect from a professional perspective?

We speak of a placebo effect when a patient assumes that a certain drug that does not contain an effective active substance will reduce pain a strong presumption. Now let’s suppose that a person who has received a placebo undergoes a medical procedure. The sensory information for example, drilling at the dentist is then met with a strong expectation. It is much less likely in this case that the patient will experience pain. The sensory information must be extremely strong to defeat the positive expectation of pain relief by the “medication”. One and the same pain stimulus can trigger strong pain or hardly be perceived under different conditions. Perception always has something to do with belief, ideas or preconceptions. If you have experienced pain at the dentist once, you

61 fortytwomagazine — № 6 42 Katja Wiech 42 KW 42 KW Placebo Effect

“Pain can also be based solely on the belief that there is tissue damage, even if there is none”

“One and the same pain stimulus can trigger strong pain or hardly be perceived under different conditions”

Yes, one’s own socialisation is also relevant in the context of pain. The religious group told us afterwards that during the study, they actually felt very close to the Virgin Mary in their experience of suffering and pain. So it was precisely the identification with the suffering Mary that led to this reduction in pain. Unfortunately, there were hardly any follow-up studies. This is also because we had incredible trouble getting this study published. Many journals were initially interested but then found that the topic was too controversial. Were there methodological doubts about the study?

No, the criticism was actually more socio-political. It was really incredible. I had never done such a controversial study before, although at first, I didn’t find it controversial at all. But religion in itself is often a contentious topic in public debate. The fact that we were actually able to prove positive effects in this particular context just raised all kinds of questions.

Could similar effects not only of religion but of cultural socialisation in general be used in pain therapy?

Absolutely, I see huge potential there. If we could actively use such effects, we could also avoid many of the problems that come from high-dose active medication, strong side effects, addiction, and so on. I believe that this experience of self-efficacy can be extremely helpful for pain patients. We have our own pharmacy in our heads, so to speak. If we could activate it systematically, that would be a huge advantage.

Dr. Katja Wiech ist Neurowissenschaftlerin an der University of Oxford, wo sie die Forschungsgruppe Pain & Mind leitet. Sie forscht unter anderem zur Auswirkung von Glauben und Placeboeffekten auf die Schmerzwahrnehmung.

Dr Katja Wiech is a neuroscientist at the University of Oxford and head of the Pain & Mind research group. Her research focuses on pain and the impact of beliefs, preconceptions, and placebo effects on pain perception.

64 fortytwomagazine — № 6 KW 42 KW 42 KW Placebo Effect

“I believe that this experience of self-efficacy can be extremely helpful for pain patients”

EN

fortytwomagazine — № 6 65 Daria Chernyshova

»Wenn Sie sino gehen, Sie nicht einmal Traum daran, Muttersprache spielen!«

“If you go to a casino, don’t even dream of using your first language!”

Sie in ein Cagehen, denken einmal im daran, in Ihrer Muttersprache zu

Interview with Prof Dr Panos Athanasopoulos, Linguistics and English Language Department at Lancaster University

67 fortytwomagazine — № 6

V Sprache und

Wahrnehmung

Prof Dr Panos Athanasopoulos

When you learn a second language later in life, you learn it in a different context; usually, via formal instruction. Because you’re more conscious of the rules that you’re learning, it’s more emotionally detached. It’s a new system that has tools and which is attached to a more logical and analytical way of thinking. These different systems of thought have been linked to the first and second language respectively. One thought system is more impulsive, because you are drawing on your instincts or your gut feeling. The other is more analytical.

How does the emotional detachment show in bilinguals’ behaviour, when they speak their second language?

One of the most fascinating examples is gambling. You know how some tend to believe that there is a blind element called luck?

If you keep winning and if you keep playing, you’re going to win more because you’re on a hot streak. Of course, that’s nonsense. Nobody is favouring you up above, you don’t have a hot streak. It’s all down to probability. There are experiments that show that if you are gambling in your first language, you’re more likely to fall for the so-called hot hand effect, whereas if you’re gambling in your second language, you’re more detached from the emotional way of thinking about luck, and thus, you will act more cautiously.

So you would recommend going to the casino only if you speak a second language, and then to only gamble in your second language?

If you go to a casino, use your second language, don’t even dream of using your first language, unless you’re very rich, and you don’t mind living dangerously.

78 fortytwomagazine — № 6 42 PA 42 PA

“If you’re gambling in your second language, you’re more detached from the emotional way of thinking about luck, and thus, you will act more cautiously”

Language and Perception EN

Prof. Dr. Panos Athanasopoulos forscht an der Lancaster University zu kognitiver Linguistik und experimenteller Psycholinguistik, auf der Suche nach Erkenntnissen darüber, wie Sprachen unser Denken und unsere Weltanschauung prägen.

Prof. Dr Panos Athanasopoulos conducts research at Lancaster University on experimental psycholinguistics and cognitive linguistics in search of insights into how languages affect our thinking and perception of the world.

Daria Chernyshova

80 fortytwomagazine — № 6 Daria Chernyshova

»Es ist nicht immer möglich, das Religiöse vom Politischen zu trennen«

“It’s not always possible to separate the religious from the political”

Interview with Dr Paul Hedges, Associate Professor in Interreligious Studies at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU, Singapore

Dr Paul Hedges

fortytwomagazine — № 6 81 VI

Religion

that created conflict. But increasingly, particularly amongst religious leadership, it is known that when an attack is associated with a religion, that religion is going to suffer. In response, there are acts of solidarity. For example, in the UK, after the 9 / 11 bombings took place very early the next morning, the orthodox rabbi of Birmingham stood outside the largest mosque. Shortly thereafter, the reformed rabbi showed up, and soon the Christian bishops got to hear about this and joined, too. There was a big multi-faith gathering outside the mosque.

How does religious illiteracy affect the relationships and interplay between religions?

If you are unfamiliar with another tradition, it is very easy to assume the worst about it. Religious literacy is, therefore an important factor. And, of course, the media also plays a role. A classic case is the notion of jihad in Islam. If you look at the media stories, it’s framed as Muslims engaging in a holy war against other people. But the term “jihad” itself simply means “striving”.

This idea of jihad as a holy war is utterly misunderstood. For much of Muslim history, to do jihad was to strive to make the world a better place. Donating to charity can be part of one’s jihad. Now they can’t use this word because of linguistic framing and a lack of religious literacy.

How can religious literacy be developed in society?

Religious literacy can be developed through schools or the media. Having said that, it needs to be well-designed. In places like the UK or Australia, we’ve had religious education in schools for a long time. It hasn’t necessarily solved prejudice between religions. There is a shortage of teachers who are really versed in the subject. If you are taught by a teacher with their own prejudices, you will pick up a negative perception. But there is some evidence that schools can improve religious relations in this regard.

It really is an issue that affects the whole of society. Media often contributes to the negative discourse surrounding certain religions, and unfortunately, in Europe, there are populist politicians who know that badmouthing Islam and telling outright lies about Islamic tradition and distorting the figures works for them. It’s one of society’s core responsibilities to do better. It’s something we see

90 fortytwomagazine — № 6 42 PH 42 PH

“If you are unfamiliar with another tradition, it is very easy to assume the worst about it”

“For much of Muslim history, to do jihad was to strive to make the world a better place”

EN Religion

here in Singapore, where the government is very clear that they are not going to weaponise religion. This means the media has to be careful, or perhaps accurate is another word, in reporting, they can’t sensationalise religious violence for headlines. We also see religious leaders and politicians working in tandem to diffuse any tensions and show coexistence between the traditions. Do you think that despite differences in beliefs, peaceful coexistence between religions has actually been the norm in human history?

In Islam, there is a concept known as Adab. It means something like good manners, customs, or etiquette. Before colonial times, everyone had their own customs. These were various types of Muslims, Hindus, Christians. It was normal that everyone had different traditions, nothing else was expected. There was a mutual understanding that you don’t push too far. There was no question of trying to convert the people because everyone had different customs. People found ways to make it work despite differences in religion. In Southeast Asia, religions coexisted peacefully for centuries until colonial dynamics altered the power structures and identity groups. Again, in the Balkans which is often seen as a hotbed of tensions Orthodox Christians, Catholic Christians, Jews, and Muslims were living alongside each other, and places such as churches might be held sacred by both Christians and Muslims. Similarly, across much of Southeast Asia, there are still many places where Christians and Muslims share shrines, for example, in Indonesia. They’re disappearing now because, after colonialism, people have started to develop identities with sharp boundaries. Until recently, this coexisting, this sharing of a religious world has simply been the norm. People were neighbours, they lived alongside each other, doing trade, finding ways to get along. For instance, if one village was predominantly Christian and another predominantly Muslim, they would come together to help build churches or mosques for the other community, come and bring food for the other’s festivals, and so on. Again, in Morocco, Muslims were the traditional custodians of Jewish graveyards, protecting and tending these for the minority community in their midst.

91 fortytwomagazine — № 6 Religion 42 PH

Prof. Dr. Paul Hedges lehrt interreligiöse Studien an der S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU, Singapur. Zu seinen Forschungsschwerpunkten zählen interreligiöse Beziehungen in Ost- sowie Südostasien.

Prof. Dr Paul Hedges is an Associate Professor in Interreligious Studies at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU, Singapore. His research interests include interreligious relations in East and SouthEast Asia.

The Artist

92 fortytwomagazine—N° 6 Daria Chernyshova

Daria Chernyshova

Exploring how beliefs form and evolve, seeing the dynamic nature of human existence. We and everything around us are constantly in flux.

Daria Chernyshova

In her work, artist Daria Chernyshova explores the processes of how beliefs form and shift. The central aspect of each piece is the composition, a balanced assembly of rigid geometric shapes and patterns that can be read as an abstraction of social mechanisms. They emphasise the ephemeral and dynamic element of human existence. We and everything around us are in constant flux. The use of an abstract visual language opens up the spectrum of interpretations to the viewer by taking away preconceived connotations. Instead, it invites the viewer to actively engage with the composition and reflect on social processes while investigating it. However, in some works, one can sense references to familiar formats like infographics that challenge the way we pass on knowledge and the beliefs they manifest. It is our beliefs that structure our worldview, it is our beliefs that guide our actions, it is our beliefs that give hope. A man-made polestar.

100 fortytwomagazine — № 6 The Artist

fortytwomagazine — № 6 101 Daria Chernyshova

»Falschinformation und Fiktion waren schon immer ein integraler Bestandteil der menschlichen Existenz«

“Misinformation, disinformation, and fiction have always been integral parts of human existence”

102 fortytwomagazine — № 6 Dr Doowan Lee

Desinformation

Interview with Dr Doowan Lee, Adjunct

Professor of Politics at the University of San Francisco, CEO of VAST-OSINT

510.000 neue Kommentare werden jede Minute auf Facebook gepostet, 136.000 neue Fotos sowie 4 Millionen Likes. Jede Sekunde finden 99.000 Suchanfragen bei Google statt: Unsere digitale Welt wird stetig schneller und immer komplexer. Der Krieg in der Ukraine führt uns ein weiteres Mal vor Augen, dass Information zu einem wichtigen Element in Kriegen und Konflikten geworden ist. Im Gespräch mit fortytwomagazine erklärt Doowan Lee, Experte für Desinformation und Informationssicherheit, warum dies kein neues Phänomen ist, welche Möglichkeiten Staaten und private Akteure haben, um Desinformationskampagnen zu bekämpfen und welche Technologien ihm schlaflose Nächte bereiten.

Interview und Übersetzung: Marie Welling

Herr Lee, wir leben in einer hochgradig digitalisierten Welt mit einer Vielzahl von Akteuren. Welche sind die wichtigsten Gruppen in unserer digitalen Umwelt im Hinblick auf die Bekämpfung von Desinformation und Fake News?

Die Integrität und Sicherheit von Daten und Informationen wird insbesondere von vier Akteuren gefördert: Nummer eins sind demokratische Regierungen und die damit verbundenen Gesetzgebungen und Programme, die Regeln und Rahmenbedingungen festlegen. Nummer zwei sind die Technologieplattformen, die in diesem Bereich auch eine sehr große Rolle spielen. Nummer drei sind Journalist:innen, da sie sozusagen die wichtigsten Wächter:innen über die Echtheit von Information sind. Wissenschaftler:innen und Forscher:innen sind die vierte Gruppe. Es ist wichtig zu verstehen, dass die Problematik rund um Desinformation etwas ist, das nicht nur eine dieser vier Gruppen betrifft, sondern alle. Um diese Probleme lösen zu können, müssen die Gruppen zusammenarbeiten.

Sie bekämpfen aktiv Desinformation und Fake News. Was sind aktuelle Lösungsansätze, um etwas als Desinformation zu identifizieren?

In unserem Feld verwenden wir in der Regel das Akronym ABC, das für »actors« , »behaviour« und »content« steht (Anm. der Red.: zu Deutsch: Akteure, Verhalten, Inhalte). Viele der bestehenden

103 fortytwomagazine — № 6 DE 42 Doowan Lee 42 DL Desinformation

VII

what’s missing in the digital ecosystem at this point. Whether you are using a search engine or browsing on social media platforms, you get certain results which you may be tempted to consume. But does it tell you whether it is trustworthy? Does it tell you whether it is reliable or where it originated? Because there is no source intelligence about digital content at this point, it becomes so easy for extremists and authoritarian regimes to manipulate, dupe and mislead large numbers of digital users.

Speaking of authoritarian regimes, is the ongoing information war between Ukraine and Russia the first of its kind?

I often try to challenge my colleagues and friends asking them to name one conflict in which storytelling was not involved. Misinformation, disinformation, and fiction have always been integral parts of human existence, whether it is peaceful or in conflict. We have always used lies and stories to mobilize people to fight on behalf of some king or emperor.

What has changed in today’s digital age?

Every 60 seconds, about 170 million emails are sent, 500,000 tweets are posted and 700,000 new searches take place. There is a new blog set up every second. So, the scale of the content has become overwhelming as well as its speed. Back in the day, there were only a handful of news outlets. Today’s media ecosystem has become incredibly complex and there are a lot of different mechanisms and venues where disinformation and conspiracy theories can hide. We also face what I call an access imbalance which occurs especially between democracies and authoritarian regimes. Those regimes have unhindered access to content platforms used in Western industrialized countries. They can essentially use the platforms to influence audiences in democratic countries but it does not work the other way around, we cannot communicate with their citizens. Authoritarian regimes such as China or Russia have the capability to undermine public discourse in democratic countries which is a huge issue.

In your opinion, what would have to change in the current media ecosystem? This might sound a little bit philosophical but we need to consider information as a public good. We have a lot of guardrails when it comes to food safety, drinking water and the air we breathe. But we have no protection in terms of how our content is harvested and used for profit. During the dawn of the Industrial Age, people used to work up to 20 hours a day and a lot of labour abuse happened. Eventually, they realized in order to avoid excessive commodification and exploitation they needed to introduce minimum safety nets because labour became a critical element for industrializing

112 fortytwomagazine — № 6 EN Disinformed Beliefs 42 DL 42 DL 42 DL

“We need to consider information as a public good”

countries. It is about how we approach the issue of information as a new social contract. Once we consider information as a public good, it will get much more feasible to establish safety nets for the information environment.

What is your biggest concern about today’s information technology that keeps you up at night?

My biggest concern revolves around synthetic content. Like Deep Fakes?

Yes, Deep Fakes are a type of synthetic content but it has multiple forms – machines can generate stories and phrases, they can even emulate a specific author. I could send an email generated by an AI mimicking your style of writing and I do not think there would be any clues to suspect that it was written by a machine. This difficulty of detection is what a lot of malign actors will try to benefit from. Another type of creating synthetic content is voice phishing which is the synthesis of a voice that could sound exactly like yours. My concern is how blindingly fast the sophistication of synthetic content is taking place. In democratic countries, there are certain discussions on how to safeguard this technology but I do not think that Russia, China or other authoritarian regimes would care much about the harm of synthetic content. They might weaponize and exploit it.

113 fortytwomagazine — № 6 Disinformed Beliefs 42 DL 42 DL

“We have a lot of guardrails when it comes to food safety, drinking water and the air we breathe. But we have no protection in terms of how our content is harvested and used for profit”

Doowan Lee ist CEO und Mitbegründer von VAST-OSINT, einem Start-up, das Datenanalysetools entwickelt, um den Ursprung von Desinformation aufzudecken. Er ist Teil der Social Media Governance Task Force der Georgetown University.

Doowan Lee is the CEO and cofounder of VAST-OSINT, a startup that builds data analytics tools to detect and expose the origin of disinformation. He is part of the Social Media Governance Task Force at Georgetown University.

Daria Chernyshova 114 fortytwomagazine — № 6

»Eine KI glaubt nicht!«

115 fortytwomagazine — № 6 Künstliche Intelligenz

Interview with Carla Hustedt, Department Head of the Digitised Society, Mercator Foundation, Essen, Germany

VIII Künstliche Intelligenz

“An AI does not have beliefs!”

the formal education system also need to be educated. We need to understand that the newsfeed does not reflect reality one-to-one and that the content stems from a wide variety of sources, not always reputable, and is sorted algorithmically. This is far from clear to everyone. Once you realise this, you can change the settings on some networks so that, for example, the content is displayed in chronological order instead of being personalised. Many users don’t even know this. It is also important not to place responsibility for these issues on the users alone. We need to think about political solutions and also hold the big tech companies accountable. Should we have a healthy distrust of AI?

Yes, this is crucial. We need to understand that these AI systems are neither perfect nor neutral but that they are a data-based rear-view mirror of our society: they can reproduce discriminatory views, make mistakes and can’t handle exceptions precisely because they are based on statistical patterns and therefore absolutely need to be monitored by humans. One must not blindly trust the technology because therein lies a great risk.

One last question about AI with relevance to everyday life: If you want to go to a restaurant tonight, who do you turn to for advice, to AI like ChatGPT or to a close friend?

I could, of course, search for a restaurant that I like and then use an AI like ChatGPT to create a list of similar restaurants. Obviously, the AI systems have access to a larger database than my friend because they potentially have information on all restaurants in Berlin, while my friend can only visit a limited number of restaurants in her lifetime. But I would still ask my friend because she knows, perhaps even better than I do, how I feel, what would do me good right now, etc. And, of course, it’s much nicer when you can have a chat afterwards about how you liked the pizza.

124 fortytwomagazine — № 6 Artificial Intelligence 42 CH 42 CH EN

Carla Hustedt leitet die Abteilung Digitalisierte Gesellschaft der Stiftung Mercator. Sie ist Teil des Beirats des Centers for Advanced Internet Studies und des Hessischen Kompetenzzentrums für verantwortungsbewusste Digitalisierung.

Carla Hustedt is head of the Digitized Society department at Stiftung Mercator. She is part of the advisory board of the Center for Advanced Internet Studies and the Hessian Competence Center for Responsible Digitalization.

125 fortytwomagazine — № 6 Daria Chernyshova

the future

126 fortytwomagazine — № 6

always is not ahead of us

127 fortytwomagazine — № 6 Daria Chernyshova

128 fortytwomagazine — № 6 Daria Chernyshova

Glaubwürdigkeit in der Diplomatie

»Storytelling ist ein Instrument, um Macht zu begründen«

“Storytelling is a tool to justify power”

fortytwomagazine — № 6

Dr Hendrik W. Ohnesorge

Interview with Dr Hendrik W. Ohnesorge, managing director of the Center for Global Studies at the Rheinische FriedrichWilhelms-University Bonn

IX

129

lower transaction costs, for example, in trade relations. But consistency says nothing about whether actions are good or bad. A state’s actions could also be consistently negative for partners. The most important thing for credibility is that words and actions coincide, that there is a continuous practice. And vice versa, when a state changes its position, this must be explained. Communication is crucial. Promises or threats must be backed by actions. This is as true for friends as it is for enemies.

What role does the person at the top play for a country’s credibility? Does it make a difference whether the US is governed by Donald Trump or by Barack Obama?

There is currently a trend in society as a whole as well as in international politics to personalise things. Which is why personalities are identified as a fourth source of Soft Power. This is because a personality influences how a country is perceived, especially in the short term. There are dependable studies that have surveyed the opinions of international respondents about the US and their trust in the current US president over a period of years. When you conflate these results, you see a correlation. Under Obama, whose trust ratings were high, the US was more popular as a country overall in Western Europe than under Trump. In short, the higher people’s trust in the US president, the better people’s opinion of the United States.

This human factor in political leadership, what does it have to do with belief? Belief in a leader is tremendously important in measuring the potential success of a state. Storytelling is a tool to justify power, and it is often tailored to a specific person, also by the media. In an increasingly complex world, it is easier to talk about Putin, Macron, Erdogan and Trump or Biden rather than about the respective countries and their various interests even if this focus entails a reduction. Empirically, the belief in such leaders can lead to greater cohesion, greater power of mobilisation in both positive and negative terms.

Are there any countries with a big contrast between Soft and Hard Power capacities? Players who achieve more through values, culture and policies than through the military or the economy? One might assume that Soft Power is solely a tool for countries with a strong military or economy that can therefore afford to pay attention to values. And it is true that one needs economic capacity to establish a Goethe Institute abroad as a tool of cultural diplomacy. But there are also countries that successfully engage in a kind of niche diplomacy that specifically relies on Soft Power. Costa Rica, for example, succeeds in achieving important environmental and climate action objectives despite its lower Hard Power capacities. Credibility plays a key role here and Costa Rica has earned it by not only demanding consistent climate protection from its negotiating partners, but also by implementing it at home: over 98 percent of the country’s energy comes from renewable sources.

138 fortytwomagazine — № 6 42 HWO 42 HWO 42 HWO EN Credibility in Diplomacy

Another country that has taken a central role on the world stage in recent years, mainly through Soft Power, is South Korea. A variety of its cultural products have achieved an immense international reach. The South Korean boy band BTS was named Entertainer of the Year by the Times Magazine in 2020, and they visited Joe Biden at the White House last year: A symbol of South Korea’s Soft Power, achieved without any official diplomatic delegations.

You emphasised the importance of narratives in international relations. If we return to Costa Rica’s climate action efforts: What narrative do we need to get all countries sitting at a negotiating table to believe that we need to make radical changes to save the climate?

Absorbing the consequences of climate damage, such as floods or droughts, or switching to low-emission strategies requires financial capacity. So Hard Power definitely plays a role in combating climate change. But when it comes down to it, you cannot force other states to approach the negotiating table. The key is to convince the other party that an objective is desirable; not through coercion or financial inducements, but because you are successfully appealing to a state’s self-interest and credibility in a way that’s attractive and persuasive. Soft Power can in fact have a more powerful and, above all, a more sustainable effect than Hard Power being imposed from the outside. Especially in the case of a transboundary crisis such as climate change, which cannot be solved through military or economic means alone, but above all through cooperation.

Dr. Hendrik W. Ohnesorge ist Geschäftsführer des Center for Global Studies und Wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter am Lehrstuhl für Internationale Beziehungen der Universität Bonn. Er erforscht unter anderem Macht und Außenpolitik der USA.

Dr Hendrik W. Ohnesorge is the Managing Director of the Center for Global Studies and a Research Fellow at the Chair of International Relations at the University of Bonn. His research interests include U.S. power and foreign policy.

139 fortytwomagazine — № 6 42 HWO Credibility in Diplomacy

“Hustle culture wants us to believe we live in a society where there is equality of opportunity”

Dr Jasmine Hill

140 fortytwomagazine — № 6

»Die Hustle Culture will uns glauben machen, dass wir in einer Gesellschaft leben, in der es Chancengleichheit gibt«

Hustle Culture

Liegt das Rezept für Erfolg in unserer Hand? Müssen wir nur an uns selbst glauben? Die Soziologin Jasmine Hill ist da anderer Meinung. Hill zufolge nehmen die Ungleichheiten zu, während sie uns immer weniger bewusst sind. Aber warum glauben viele, dass wir alle erfolgreich sein können? Einer der Hauptgründe ist die »Hustle Culture« – eine neue Kultur von Überzeugungen, Symbolen und Ritualen, die der Plattform-Kapitalismus nach dem Vorbild des amerikanischen Traums hervorgebracht hat. Im Gespräch mit fortytwomagazine bringt uns Jasmine Hill die irreführenden Versprechen der Technologien und Plattformen näher und erklärt, warum es gefährlich ist, zu glauben, dass Chancenungleichheit Schnee von gestern ist.

Interview: Lena Kronenbürger

Übersetzung: Ina Habermann

Am liebsten möchte ich morgens in aller Ruhe meinen Kaffee trinken. Doch Influencer:innen auf Instagram und anderen Social-Media-Plattformen zufolge, liegt einer der Schlüssel zum Erfolg darin, eine produktive Morgenroutine zu entwickeln. Lesen, Tagebuch schreiben und Yoga machen – ist es wirklich das, was es braucht?

Unsere Zeit als eine Ware zu betrachten, ist ein grundlegendes Konzept des Kapitalismus. Wenn es möglich ist, jedes bisschen unserer persönlichen Zeit zu quantifizieren und effizient zu nutzen, führt dies logischerweise zu wirtschaftlichem Erfolg, selbst wenn diese Aktivitäten normalerweise als Freizeit betrachtet werden. Eine produktive Morgenroutine zu schaffen, wird dann beispielsweise zu einem Job, noch bevor die Arbeit beginnt. Influencer:innen sagen uns, dass wir lesen, Tagebuch führen und all diese Dinge für unser »persönliches Wachstum« tun sollen. Dabei behaupten sie, dass diese Maßnahmen die persönliche Optimierung und Effizienz steigern können – und dass sie uns ebenso Vorteile auf dem Arbeitsmarkt verschaffen. Wenn man zum Beispiel zum Vergnügen liest, wird man vermutlich ein besserer Gesprächspartner oder ein fähigerer Netzwerker. Nun spricht nichts gegen eine Morgenroutine. Doch macht sie uns wirklich erfolgreicher? Oder sind wir weniger wertvoll, wenn wir keine solche Routine haben? Die Antwort auf diese Fragen lautet nein. Stattdessen gibt es reale, strukturelle

fortytwomagazine — № 6 DE 42 Jasmine Hill Hustle Culture

Interview with Dr Jasmine Hill, assistant professor of Public Policy and Sociology at UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, Los Angeles.

X

That sounds like a revival of the American Dream. Yes, the idea that being an entrepreneur leads to financial freedom is a very old one and similar to the historical narrative of the American dream. The same applies to the aspect of personal optimization, which means continuously developing and fostering good habits. But one component is new: platforms and the belief that technology opens unprecedented and indiscriminate access to financial freedom. It is not enough anymore to be an entrepreneur or to have the right mindset. Hustle culture wants us to believe that we can achieve anything we previously couldn’t because of digital platforms. Cryptocurrencies or the capacity to advertise and start a business on TikTok are now the solutions to all of our inequality problems. The platforms themselves get framed as essentially the missing ingredient in realizing all of our meritocratic fantasies.

Performance-oriented memes like “I’ve got a dream that’s worth more than my sleep” or “0 % luck, 100 % hustle” are part of our everyday digital world. What is the unifying desire of hustlers?

Hustle culture is a way people use to make sense of and deal with economic precarity. They want to solve financial problems, so the goal of hustle ethic as a belief system is to reach financial freedom. Sure, some want to become billionaires, but in many cases – given how they describe financial freedom as taking vacations, retiring, and having savings – they simply want what has traditionally been considered middle-class life.

Many people only know the term hustler from hip-hop songs. How has the concept evolved?

The culture itself has named itself “hustle culture”, which is a nod and tribute to African-American culture. It’s fascinating that the “hustler” has historically been a marginalized and disrespected individual. If someone hustles you, the term suggests that the person is cheating or stealing from you. Through the popularization of hip-hop, we have taken on this valiant, persevering, moral subject who still might cut corners to achieve their goals. Today, this is considered positive. We’re talking about people who are far outside of that original picture. “White tech bros” who are interested in matters far beyond the traditional hustler image are taking on that identity. I think that speaks to a widening of the economic precarity that was once uniquely situated, at least in the U.S., as an urban, black, low-income experience. With the changes in labor relations and worker protections over the years, people are experiencing a new wave of economic precarity and loss, and thus the need to hustle.

148 fortytwomagazine — № 6 42 JH 42 JH 42 JH Hustle Culture

“Hustle culture wants us to believe that we can achieve anything we previously couldn’t because of digital platforms”

EN

Do you have to be in a precarious financial situation to hustle?

I think there are plenty of wealthy people who fall into hustle culture, in fact, they might be the most dangerous. Elon Musk, for example, infamously pushed the idea that relentless hard work leads to success when he declared “Nobody ever changed the world on 40 hours a week.” What’s dangerous about that is that some people will hear him say that and see that he’s a billionaire, and think that if they just work hard enough, they too can become wealthy like him. This, of course, completely leaves out that he inherited an incredible amount of his wealth. But the second aspect that’s dangerous is that as an employer, Musk also has the power to subject his workforce to unfair, and as per the reports of his Fremont Tesla factories, arguably inhumane work conditions by pushing people to work hard for his benefit. So, anyone can subscribe to hustle culture. It might just lead to different kinds of outcomes.

With your research, you are making the inequalities visible again that hustlers tend to neglect. But now, people might provocatively ask, “What’s wrong with believing in oneself?” In other words, are you dashing hopes? The truth is that many are out of touch with the material realities of modern inequality. By asking people to acknowledge the existing racial and gender inequality, maybe I am asking them to be a bit more pessimistic. Hustle culture is a reasonable reaction to economic precarity; It’s a sensible response to say: “how can I take matters into my own hands? I have to figure out how to hustle, make ends meet, and solve my economic problems.” However, the illusion that a massive redistribution of wealth is taking place that is accessible to all has truly dangerous consequences and prevents mass mobilization against inequality.

Dr. Jasmine Hill ist Lehrbeauftragte für Public Policy and Sociology an der UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs in Los Angeles. In ihrer Dissertation beschäftigte sich die Soziologin mit Hustle Culture und Plattform-Kapitalismus.

149 fortytwomagazine — № 6 42 JH 42 JH Hustle Culture

Dr Jasmine Hill is an Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Sociology at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs in Los Angeles. Her dissertation explored the hustle ethic and the spirit of platform capitalism.

mind change and try my

151 fortytwomagazine — № 6 Daria Chernyshova

Imprint

Herausgeber | Publishers

Berger Bille Kronenbürger

Richthofen GbR | ViSdP

Redaktion | Editorial Board

Lena Kronenbürger, Chefredakteurin

Eliana Berger

Kurt Bille

Lara von Richthofen

Verlag | Publishing House

Slanted Publishers UG (haftungsbeschränkt)

Nördliche Uferstraße 4–6

76189 Karlsruhe, Germany slanted.de

Verlagsleitung | Publishing

Direction

Lars Harmsen, Julia Kahl

ISBN: 978-3-948440-51-0

© Slanted Publishers, Karlsruhe, 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy or any storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek. The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie, detailed bibliographic data is available online at dnd.d-nb.de

Interviews

Eliana Berger

Kurt Bille

Jonas Hermann

David Krebs

Lena Kronenbürger

Sophia Stahl

Ella Steiner

Marie Welling

Lisa Zahrobsky

Artist Liaison

Kurt Bille

Artist

Daria Chernyshova instagram.com/ intuitive.practice

Illustration series:

Man-Made Polestar, 2023

Übersetzung | Translation

Kurt Bille

Ina Habermann

Jonas Hermann

David Krebs

Lara von Richthofen

Laura Emily Schulze

Ella Steiner

Marie Welling

Lektorat | Proofreading

Deutsch | German

Julia Becker

Englisch | English

Oscar Bell

Kandice Clarke

Jules Skotnes-Brown

Grafisches Konzept | Graphic Concept

Slanted Publishers, slanted.de

Lars Harmsen, Julia Kahl

Grafikdesign | Graphic Design

Clara Weinreich

Schriften | Typefaces

NN Nouvelle Grotesk

& NN Rekja by Anton Studer, Nouvelle Noire, nouvellenoire.ch

Logo Slanted Publishers

Social Media | Blog

Eliana Berger

Kurt Bille

Charlotte Boschen

Jonas Hermann

Anna Hörter

David Krebs

Lena Kronenbürger

Neele Mühlhoff

Leonie Quedden

Lara von Richthofen

Laura Emily Schulze

Sophia Stahl

Ella Steiner

Marie Welling

Til Antonie Wiesbeck

Lisa Zahrobsky

Technical Lead

fortytwomagazine

Frederik Junge

Visit Our Social Media Facebook, Instagram & LinkedIn: fortytwomagazine

Twitter: fortytwomgzn fortytwomagazine.com

Angaben gemäß Paragraph

5 TMG | Legal Information

Berger Bille Kronenbürger

Richthofen GbR | ViSdP

Sankt Augustiner Str. 11 53225 Bonn, Germany contact@fortytwomagazine. com

Redaktionsschluss | Editorial Deadline

28.02.2023 | 28 February 2023

Wir danken herzlich unserem Förderer BauData Projektentwicklungs-und Beratungsgesellschaft mbH.

We sincerely thank our sponsor BauData Projektentwicklungsund Beratungsgesellschaft mbH.

152 fortytwomagazine—N° 6 Impressum

Did you know that our beliefs have the power to influence how we perceive pain and that we believe different things depending on whether we are speaking our native language or a foreign language?

Have you ever wondered why rational arguments often fail to convince conspiracy ideologues or considered how the popular phrase “just believe in yourself” masks structural inequality?

This 6th issue of fortytwomagazine invites you to explore the realm of beliefs through ten thought-provoking interviews in both German and English with distinguished scientists, who shed light on the topic from their distinct perspectives such as social psychology, religion, and artificial intelligence.

fortytwomagazine.com 42 #6

glauben beliefs

One Topic —Ten Perspectives Das gesellschaftspolitische Interviewmagazin SLANTED.DE € 18.– (DE) 978-3-948440-51-0