HEALTH, LIFE & HIV

Advocating for people with HIV

This is only a brief summary of important information about BIKTARVY® and does not replace talking to your healthcare provider about your condition and your treatment.

BIKTARVY may cause serious side e ects, including:

` Worsening of hepatitis B (HBV) infection. Your healthcare provider will test you for HBV. If you have both HIV-1 and HBV, your HBV may suddenly get worse if you stop taking BIKTARVY. Do not stop taking BIKTARVY without fi rst talking to your healthcare provider, as they will need to check your health regularly for several months, and may give you HBV medicine.

BIKTARVY is a complete, 1-pill, once-a-day prescription medicine used to treat HIV-1 in adults and children who weigh at least 55 pounds. It can either be used in people who have never taken HIV-1 medicines before, or people who are replacing their current HIV-1 medicines and whose healthcare provider determines they meet certain requirements.

BIKTARVY does not cure HIV-1 or AIDS. HIV-1 is the virus that causes AIDS.

Do NOT take BIKTARVY if you also take a medicine that contains:

` dofetilide

` rifampin

` any other medicines to treat HIV-1

Tell your healthcare provider if you:

` Have or have had any kidney or liver problems, including hepatitis infection.

` Have any other health problems.

` Are pregnant or plan to become pregnant. It is not known if BIKTARVY can harm your unborn baby. Tell your healthcare provider if you become pregnant while taking BIKTARVY.

` Are breastfeeding (nursing) or plan to breastfeed. Talk to your healthcare provider about the risks of breastfeeding during treatment with BIKTARVY. Tell your healthcare provider about all the medicines you take:

` Keep a list that includes all prescription and over-thecounter medicines, antacids, laxatives, vitamins, and herbal supplements, and show it to your healthcare provider and pharmacist.

` BIKTARVY and other medicines may a ect each other. Ask your healthcare provider and pharmacist about medicines that interact with BIKTARVY, and ask if it is safe to take BIKTARVY with all your other medicines.

BIKTARVY may cause serious side e ects, including:

` Those in the “Most Important Information About BIKTARVY” section.

` Changes in your immune system. Your immune system may get stronger and begin to fight infections that may have been hidden in your body. Tell your healthcare provider if you have any new symptoms after you start taking BIKTARVY.

` Kidney problems, including kidney failure. Your healthcare provider should do blood and urine tests to check your kidneys. If you develop new or worse kidney problems, they may tell you to stop taking BIKTARVY.

` Too much lactic acid in your blood (lactic acidosis), which is a serious but rare medical emergency that can lead to death. Tell your healthcare provider right away if you get these symptoms: weakness or being more tired than usual, unusual muscle pain, being short of breath or fast breathing, stomach pain with nausea and vomiting, cold or blue hands and feet, feel dizzy or lightheaded, or a fast or abnormal heartbeat.

` Severe liver problems , which in rare cases can lead to death. Tell your healthcare provider right away if you get these symptoms: skin or the white part of your eyes turns yellow, dark “tea-colored” urine, light-colored stools, loss of appetite for several days or longer, nausea, or stomach-area pain.

` The most common side e ects of BIKTARVY in clinical studies were diarrhea (6%), nausea (6%), and headache (5%).

These are not all the possible side e ects of BIKTARVY. Tell your healthcare provider right away if you have any new symptoms while taking BIKTARVY. You are encouraged to report negative side e ects of prescription drugs to the FDA. Visit www.FDA.gov/medwatch or call 1-800-FDA-1088.

Your healthcare provider will need to do tests to monitor your health before and during treatment with BIKTARVY.

Take BIKTARVY 1 time each day with or without food.

` This is only a brief summary of important information about BIKTARVY. Talk to your healthcare provider or pharmacist to learn more.

` Go to BIKTARVY.com or call 1-800-GILEAD-5.

` If you need help paying for your medicine, visit BIKTARVY.com for program information.

People featured take BIKTARVY and are compensated by Gilead.

#1 PRESCRIBED HIV TREATMENT*

Ask your healthcare provider if BIKTARVY is right for you. NOW THERE’S

BIKTARVY® is now approved for more people than ever before.

BIKTARVY is a complete, 1-pill, once-a-day prescription medicine used to treat HIV-1 in certain adults. BIKTARVY does not cure HIV-1 or AIDS.

*Note: This information is an estimate derived from the use of information under license from the following IQVIA information service: IQVIA NPA Weekly, for the period week ending 04/19/2019 through week ending 05/19/2023. IQVIA expressly reserves all rights, including rights of copying, distribution, and republication.

Scan to learn more about the latest BIKTARVY update.

Please see Important Facts about BIKTARVY, including important warnings, on the previous page and at BIKTARVY.com.

Jirair Ratevosian visits the Elizabeth Taylor mural in Los Angeles.

Our roster of bloggers spans the diversity of the HIV community. Go to poz.com/blogs to read varying points of view from people living with the virus as well as from HIV-negative advocates. Join the conversation in the comments section. Visit the blogs to find hope and inspiration from others.

D

POZ OPINIONS

Advocates, researchers, politicians, thought leaders and folks just like you all have ideas worth sharing. Go to poz.com/ opinions to read about topics such as living with HIV, improving care and treatment, increasing prevention efforts and fighting for social justice.

#UNDETECTABLE

The science is clear: People who have an undetectable viral load don’t transmit HIV sexually. In addition to keeping people healthy, effective HIV treatment also means HIV prevention. Go to poz.com/undetectable for more.

Scan the QR code (le ) with your smartphone camera or go to poz.com/digital to view the current issue and read past issues online.

20 HIV AS THE COMMON DENOMINATOR

Public health warrior Jirair Ratevosian continues to fight for people living with the virus. BY TIM MURPHY

24 KUDOS FOR SAYING THAT RuPaul’s Drag Race contestant Q discusses having HIV. BY MATHEW RODRIGUEZ

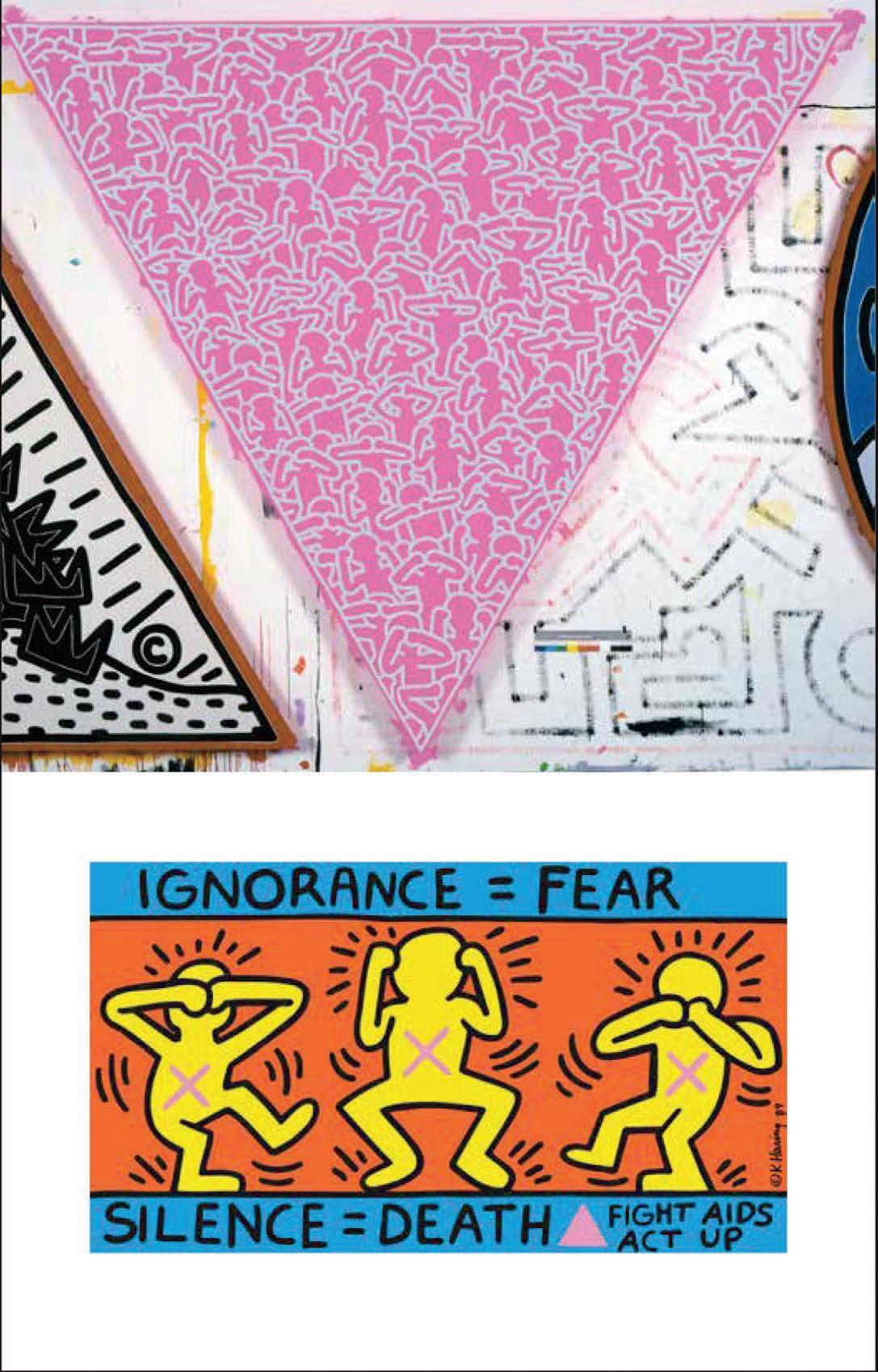

26 RADIANT ACTIVIST An excerpt of a new biography shines a light on the life of Keith Haring. BY BRAD GOOCH

3 FROM THE EDITOR

Defying Gravity

4 POZ Q & A

Former model and author Brad Gooch discusses his new biography of the late artist and activist Keith Haring.

6 POZ PLANET

Oprah pays tribute to her brother lost to AIDS • R.I.P. David Mixner, trailblazing strategist and activist • Elton John’s record-breaking 2024 Oscar party • meet GMHC’s new interim CEO • POZ Stories: Will Kennedy • Everyday: HIV milestones

10 VOICES

HIV.gov offers six tips on modernizing outdated HIV crime laws • thoughts on the emotional AIDS memorials during Madonna’s 2024 New York concert

14 SPOTLIGHT

A tribute to the late Hydeia Broadbent

16 BASICS

Medication adherence

17 RESEARCH NOTES

Biktarvy PEP • weekly pills • HIV remission in children • prostate cancer

18 CARE & TREATMENT

Cabenuva for people with adherence challenges • how well does oral PrEP work for women? • doxyPEP reduces STIs in San Francisco • cardiovascular care for people with HIV

32 HEROES

Drag performer Jerry Van Hook, aka Shi-Queeta Lee, is making the best of having a second chance at life.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

ORIOL R. GUTIERREZ JR.

MANAGING EDITOR

JENNIFER MORTON

DEPUTY EDITOR

TRENT STRAUBE

SCIENCE EDITOR

LIZ HIGHLEYMAN

COPY CHIEF

JOE MEJÍA

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

LAURA SCHMIDT

ART DIRECTOR

DORIOT KIM

ART PRODUCTION MANAGER

MICHAEL HALLIDAY

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

SHAWN DECKER, OLIVIA G. FORD, ALICIA GREEN, MARK S. KING, TIM MURPHY, MATHEW RODRIGUEZ, CHARLES SANCHEZ

CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS

JOAN LOBIS BROWN, LIZ DEFRAIN, ARI MICHELSON, JONATHAN TIMMES, BILL WADMAN

FOUNDER

SEAN STRUB

LEGACY ADVISER MEGAN STRUB

ADVISORY BOARD

A. CORNELIUS BAKER, GUILLERMO CHACÓN, SABINA HIRSHFIELD, PHD, KATHIE HIERS, TIM HORN, PAUL KAWATA, NAINA KHANNA, DANIEL TIETZ, MITCHELL WARREN

PRESS REQUESTS NEWS@POZ.COM

SUBSCRIPTIONS HTTP://ORDER.POZ.COM

UNITED STATES: 212-242-2163

SUBSCRIPTION@POZ.COM

FEEDBACK

EMAIL WEBSITE@POZ.COM OR EDITOR-IN-CHIEF@POZ.COM

SMART + STRONG

PRESIDENT AND COO

IAN E. ANDERSON

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

ORIOL R. GUTIERREZ JR.

CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER

CHRISTIAN EVANS

VICE PRESIDENT, INTEGRATED SALES

DIANE ANDERSON

INTEGRATED ADVERTISING MANAGER

JONATHAN GASKELL

INTEGRATED ADVERTISING COORDINATOR

SARAH PURSELL

SALES OFFICE

212-938-2051; SALES@POZ.COM

CDM PUBLISHING, LLC

CEO

JEREMY GRAYZEL

CONTROLLER

JOEL KAPLAN

Jirair Ratevosian at the Washington, DC, office of HIV advocate Representative Barbara Lee (D–Calif.) when he was her legislative director. I was then the deputy editor of POZ.

Since then, it’s been gratifying to see how he’s continued his journey as an HIV advocate. Ratevosian is HIV negative, so people may assume that he became an ally only as a result of his time with Lee. But in fact, he became devoted to the cause years earlier, which led him to work for Lee.

It’s also been heartwarming to witness Ratevosian’s path to becoming an out gay man. He was raised in a conservative family, which is an experience I can relate to. Despite being an HIV advocate and having many gay friends, he didn’t come out publicly until his 2023 marriage to Micheal Osa Ighodaro, an HIV-positive activist.

Most recently, Ratevosian ran for Congress in California with the hope of becoming a fierce Capitol Hill advocate for people living with HIV. Unfortunately, his run wasn’t successful. Nevertheless, we’re pleased to spotlight him on the cover of this issue. Please go to page 20 to read more about him and his future plans.

Ratevosian is a great example to lead our special issue dedicated to Pride, which spotlights LGBTQ-themed stories throughout. In addition to our profile of Ratevosian, we highlight a new biography of the late artist Keith Haring. Go to page 26 to read an excerpt that describes his decision to publicly disclose he was living with HIV.

Written by Brad Gooch, the book is titled Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring

The author has written other acclaimed biographies as well as poetry, novels and memoirs, including Smash Cut, about his decade-long relationship with film producer Howard Bruckner, who was lost to AIDS in 1989. Go to page 4 for our Q & A with Gooch.

Haring continues to loom large in AIDS history and current art trends. Madonna

counted him as one of her friends. During her recent Celebration tour, Madonna dedicated a portion of each show to honor those lost to the virus. As she sang “Live to Tell,” images of her friends, including Haring, were projected behind her onstage followed by photos of people she never knew. Go to page 12 for more.

RuPaul’s Drag Race has arguably made drag a mainstream affair. The show has also served as a high-profile platform for some contestants— including Ongina and Trinity K. Bonet—to reveal they’re living with HIV. This season, contestant Q became the latest. Go to page 24 to read about her journey and how her HIV disclosure became a meme.

Many drag performers without the kind of visibility a TV show can provide have also come forward to share that they’re living with HIV. Jerry Van Hook, aka Shi-Queeta Lee, is definitely one of them. Go to page 32 for more.

Born with HIV in 1984, LGBTQ ally Hydeia Broadbent died in February. She graced the cover of POZ twice, first in 1996 and again in 2017. Please go to page 14 for more about her amazing life of advocacy.

ORIOL R. GUTIERREZ JR. EDITOR-IN-CHIEF editor-in-chief@poz.com

to read more from Oriol? Follow him on Twitter @oriolgutierrez and check out blogs.poz.com/oriol.

Author Brad Gooch discusses his new biography of the late artist and activist Keith Haring.

AFTER WORKING AS A MODEL IN 1970S AND ’80S NEW YORK CITY, Brad Gooch became an author. He wrote poetry, novels and memoirs, including Smash Cut, about his decade-long relationship with film producer Howard Brookner, who died of AIDS in 1989. He also wrote acclaimed biographies of literary legends Frank O’Hara and Flannery O’Connor.

His latest biography is Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring. It’s a fat, juicy and extremely well-researched account of the brief but explosive life and career of the beloved pop artist, who died of AIDS-related complications in 1990 at age 31.

Below is a short version of a long interview that Gooch, 72, gave to The Caftan Chronicles, the Substack newsletter by longtime POZ contributing writer Tim Murphy. Go to page 26 in this issue to read an excerpt from the book.

What is a typical day like?

I have two kids—Walter, 9, and Glenn, 5. Today, I woke up at 6:40 a.m. listening to Walter play chess on this kids’ app. My partner, Paul Raushenbush, is 59 and is a minister who is president and CEO of the Interfaith Alliance. We live in Chelsea [in Manhattan]. I make breakfast for the boys. Paul goes to the gym, and I take the boys to school a few blocks away and then go to my separate office nearby. Then I’ll see my trainer. Then I’ll go home, and we have dinner together. The boys and I will watch a short video, and then I put them to bed. I watch PBS Newshour and read, and then I sleep.

What is it like having kids rather late in life?

It’s been great. I think 60 is a good age to start having children. I think I would’ve been

a horrible parent in my 30s because I’d have wanted to go out all the time, network, travel or work on my career.

You grew up in a small town in Pennsylvania—just like Keith! There were a lot of things about [writing about] Keith that came naturally to me. We were living in New York City at the same time. Both of us were born in the 1950s.

His parents didn’t want him to be an artist, and my parents didn’t want me to be a poet. Both our parents were Republicans. Keith’s mother said to me, “Keith never said the words gay or AIDS to us,” and I completely understood that. I don’t think I ever said the word gay to my parents, but when my lover, Howard Brookner, had AIDS, he’d come home with me in his wheelchair, and my parents accepted all of this, but we never said, “We are lovers, and one of us has AIDS.”

After all this immersion into Keith’s life and psyche, who do you think he was?

Keith had this innocent, almost naive quality combined with this enormous energy. He was really on a mission. He was an unusual artist because he was so generous in terms of [promoting] other people’s works.

He did a huge amount of public and community art that he didn’t seek compensation for.

And he set up the Keith Haring Foundation at age 28 and said that half the funds would go to charities involving AIDS and children, and that’s the case to this day. But there were other aspects to him that I think were mostly explained by immaturity.

For one thing, as your book makes clear, he was a real fame whore. His whole celebrity thing was kind of extreme. I mean, if you have Andy Warhol criticizing you for wanting to have your picture taken so badly. [Laughs] He had this gaga fanboy quality.

Your book vividly captures the frantic pace of Keith’s work and his entire life, especially as he became aware that he likely didn’t have long to live.

I had a far greater respect for him by the time I was finishing the book. I think the way he faced death was amazing. Instead of melting away, he revved everything up and created some of the best work that he ever made. In the ’90s, it seemed like he was going to fade away, but in so many ways, we’re living in Keith’s world now.

He’s had a huge surge of popularity in the 21st century. You see his work everywhere.

The world caught up to him. So many of the things he was propelled by in his work are now understandable. The idea of democratization, that art is for everybody. Not having this huge distinction between high and low art and the availability of every surface, activist messaging and the licensing of products that he was so criticized for at the time. All of this is our current world.

Your book really captures the mood arc of the ’80s—from a decade that

starts as the carryover of the hedonism of the ’70s and then darkens and saddens because of AIDS.

It’s true that it started with the infectious, liberating tone of the late ’70s. Then you get this scary article in The New York Times in 1981 [about the first AIDS cases].

I remember someone telling me that year that he had it—whatever we called it—the gay virus, and I almost passed out.

You’re HIV negative?

I didn’t know that until 1987, when I took an actual test. [Even once the test came out in 1985], people weren’t taking it because there was nothing you could do about positive results. Keith was healthy for a long time in the ’80s, but he assumed he had the virus because of the life he’d led at the baths. But the

sensed that you were gay, they didn’t want to use you.

Ew, that’s gross. So how do you see your present self in the context of your past self?

The main things that define my present life are having this family and writing. I’m living my best life now, but I also have a kind of PTSD from having lived through AIDS and the loss of Howard. In the ’90s, a numbness set in for me emotionally and sexually. I just went to Madonna’s Celebration concert at Madison Square Garden, and there’s a five - story-high image of both Keith Haring and Howard [when she sings “Live To Tell” as a memorial of her friends and others lost to AIDS].

Howard is wearing this striped shirt from Brooks Brothers. That’s what I was focusing on. [ Pauses] One reason I’m

“In so many ways, we’re living in Keith’s world now.”

epidemic didn’t really start manifesting until the mid-’80s. Suddenly, it seemed like every other person was either HIV positive or sick, and you were going to memorial services every night. That’s a tremendously dark period that Keith dies at the end of.

What was modeling like?

There were great aspects to it. I was suddenly invited into all these cool places and rich people’s houses and dinners where I sat next to [famed ballet dancer Rudolf] Nureyev, and he put his hand on my thigh. But I watched a lot of boy and girl models get destroyed by all that.

Also, gay photographers only wanted to work with straight models, so if they

glad to have this book about Keith out there is that it tells the story of AIDS at that moment, because I don’t think young queer people know it. That period is still always with me. Through the 2000s, I’d wake up in the middle of the night with this fear of death. That didn’t go away until I became a father.

Why do you think that is?

I guess now I have the feeling or the illusion that there’s a future. In a Rolling Stone interview Keith did when he came out as a person with AIDS, he said, “Well, I don’t have dreams of the future anymore.” That really stuck with me. But somehow, now, with kids, I have this sense that they’re going on into the future. Q

Thanks to Oprah Winfrey, HIV and AIDS took center stage March 14 at the 35th annual GLAAD Media Awards honoring LGBTQ representation in the media. A longtime queer ally, Winfrey received the Vanguard Award. During her acceptance speech, she became emotional while talking about her older brother, who was gay and died 35 years ago of an AIDS-related illness.

Winfrey also shared how she used The Oprah Winfrey Show, which aired from 1986 to 2011, to teach audiences the medical facts about HIV and to highlight stories of folks living with the virus, including advocate Hydeia Broadbent, who first appeared on Winfrey’s talk show in 1996 at age 11 (and on the cover of POZ in 1997 and 2017) and who died in February (go to page 14 for a tribute to Broadbent).

Upon receiving the Vanguard Award, Winfrey said:

Oprah Winfrey

lived to witness these liberated times and to be here with me tonight.…

“Many people don’t know this, but 35 years ago, my brother, Jeffrey Lee, passed away when he was just 29 years old from AIDS. Growing up at the time we did, in the community we did, we didn’t have the language to understand or speak about sexuality and gender in the way we do now. And at the time, I didn’t know how deeply my brother internalized the shame that he felt about being gay. I wish he could have

“What I know for sure is that when we can see one another, when we are open to supporting the truth of a fellow human, it makes for a full, rich, vibrant life for us all. And that’s what I wish my brother Jeffrey could have experienced: a world that could see him for who he was and appreciate him for what he brought to this world. I am proud to receive this honor. Thank you, GLAAD.” —Trent Straube

He was arrested in one of the first White House AIDS protests.

Longtime LGBTQ political strategist and AIDS activist David Mixner, who became a nationally known openly gay figure in the Clinton administration, died at his home in New York City on March 11, 2024. The cause was long COVID, The New York Times reported. He was 77.

Mixner was HIV positive and lost a partner of 12 years to the disease as well as, by his own count, 382 friends. While Ronald Reagan was president in 1987, Mixner participated in one of the first AIDS protests at the White House and was arrested along with 64 others, according to The Advocate. The LGBTQ magazine added that Mixner assisted in drafting legislation during the 1980s that helped California address the growing epidemic.

Mixner worked mostly behind the scenes, but he was an openly gay man

David Mixner

David Mixner

at a time when that was rare and fraught with danger. He was pivotal in fighting antigay legislation in the 1970s and 1980s and in pushing the political establishment to support and fund LGBTQ issues. A longtime friend of Bill Clinton, Mixner worked on Clinton’s presidential campaign, influencing him

to include AIDS and gay rights in his messaging.

In 2021, the City University of New York (CUNY) School of Law started a fellowship in Mixner’s name aimed at supporting students who intend to serve the LGBTQ and HIV communities. In a CUNY interview, Mixner said:

“The community [in the early days] mobilized when our government turned its back on us.… Many of us were included in a group that signed a pledge—I was one of the founders of the pledge— that no person with AIDS would die alone. Because many, many of our friends’ families disowned them when they found out; my partner’s family disowned him and wouldn’t see him before he died. I don’t know how a mother and father can do that, but that’s another issue. We made sure someone was there all the time by their bedsides.” —TS

The fundraiser raised nearly $11 million to fight HIV.

It’s the star-studded tradition that keeps on giving. The Elton John AIDS Foundation’s 32nd annual Academy Awards Viewing Party raised $10.8 million to fight HIV, a record-breaking high for the event.

Elton John and husband David Furnish’s Oscar party was cohosted this year by Tiffany Haddish, Neil Patrick Harris and David Burtka.

The evening featured an auction of fabulous collectibles (including a fully bedazzled piano!) and a performance of “Are You Ready for Love” by the R&B soul-pop trio Gabriels and the Rocket Man himself, according to a press release from the foundation.

Since 1992, the Academy Awards Viewing Party has raised over $110 million for efforts to fight HIV, AIDS and stigma across the globe, including in the U.S. South.

Above from le : Neil Patrick Harris, David Burtka, Elton John, Tiffany Haddish, David Furnish, Kyle Richards, Avril Lavigne and Kesha

“So far, this has been an extraordinary year beyond my wildest dreams, including the honor of achieving the EGOT, but it’s tonight’s gathering that is the ultimate highlight,” John said in the press statement, referring to taking home his first Emmy Award in January, when his concert film Elton John Live: Farewell From Dodger Stadium won for Outstanding Variety Special. According to Smithsonian, John is now the 19th person ever to earn an Emmy, Grammy, Oscar and Tony (EGOT).

Regarding his latest Academy Awards party, John added: “We won’t stop until we achieve our mission.”

Among the celebrity revelers in attendance were Danny DeVito, Rhea Pearlman, Donatella Versace, Alicia Silverstone, Billy Eichner, Sharon Stone, Cara Jade Myers, Christian Siriano, Brandi Carlile, Benson Boone, Tim Allen, Dylan Arnold, Olivia Holt, LOONY, Heidi Klum, Michaela Jaé Rodriguez, Ashlyn Harris, Patricia Arquette, Orville Peck, Sophia Bush, Julianne Hough, Zoe Lister-Jones, Daphne Guinness, Zooey Deschanel, Lucien Laviscount, Charlotte Tilbury, MUNA, Melanie Lynskey, Elizabeth Hurley, Joseph Lee, Alexis Bledel, Toni Braxton, Colton Haynes, Eric McCormack, Olivia Welch, Bailee Madison, Hunter Doohan, Kyle Richards, Avril Lavigne, Kesha, HotWax, Valerie Bertinelli, Ian Bohen and Smokey Robinson. —TS

New York City HIV and AIDS service provider

GMHC announced that Robert Guimento, MHA, is its new interim CEO. Guimento had served as president of the NewYork-Presbyterian (NYP) Brooklyn Methodist Hospital and led several other hospitals, outpatient clinics, medical staff and health care teams.

“GMHC’s board of directors is so excited to welcome Rob to the GMHC family,” Jon Mallow, who has served as board chair since 2020, said in a GMHC press release. “As GMHC continues historic program growth in supportive housing, our 340B pharmacy and other lifesaving services, Rob’s experience and expertise add even more transformative power to our executive team…. Rob will focus on our core commitments to clients, staff and volunteers. He will also support the growth and development of the board while we continue the search for our next permanent CEO.”

“GMHC is a historic organization critical to the health and well-being of thousands of New Yorkers living with and affected by HIV and AIDS,” Guimento said in a GMHC press release, “and I am honored to serve as its new interim CEO. Our leadership in the fight to end the HIV epidemic extends nationwide through advocacy in the media and at all levels of government. I look forward to supporting our inspirational staff and volunteers, donors and funders and to serving our clients.”

At NYP Brooklyn Methodist Hospital, Guimento led a 600-bed hospital and oversaw an operating budget of $1 billion, $900 million in capital projects, 3,800 staff and 14 accredited residency and fellowship programs, according to the GMHC press release. He also has extensive consulting experience in capital financing, post-merger integration and financial turnarounds, with clients that have included national health care systems, payers and government agencies.

Officially established in 1982 as Gay Men’s Health Crisis, GMHC is the world’s oldest HIV and AIDS service provider. —TS

Irish advocate Will Kennedy is an out and proud queer man living happily with HIV.By Will Kennedy

I am a 66-year-old queer, working-class Irish man living with HIV since 2007. I am also an activist and advocate for people living with HIV in my country. I was born in 1957, in an Ireland that was dominated and controlled by the Catholic Church. This had an enormous impact and effect on how I dealt with my sexuality. For more than half my life, I lived in fear that people would discover my secret. I attempted suicide on a number of occasions, but I overcame my struggles, and I am here to tell the tale.

When I was diagnosed with HIV in 2007, I was faced with a choice: Go back into a closet, or be open, vocal and visible about my HIV. Knowing the damage that living with a secret had done to my life, I knew I had no choice. I am a member of the Fast-Track Cities steering committee for Cork, Ireland. I have been on radio and had articles published in newspapers. Today, I am an out, proud and very visible queer man who happens to be living very happily with HIV.

5

Of course, it was not always like this. I have been in recovery for 29 years. At Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, I learned that my sexuality was not the problem; the social, religious and structural norms and values of the society that I grew up in were the real problems. Once I realized this, I was able to come out to myself. I stopped looking for acceptance from outside sources.

My journey was one of self-discovery; it was painful and very hard at times. But it was worth it. My life experiences are what have shaped me, made me the man I am today.

I am very vocal, visible and out here in Ireland along with other activists. I think the greatest barrier to ending HIV is stigma. HIV is an illness, a virus—nothing more, nothing less. It does not judge people; it does not moralize. I work hard to try to raise awareness about HIV—not just for the LBGTQ+ community but for anyone living with HIV.

We have a support group here in Cork, and it is made up of men, women,

Will Kennedy

straight and queer. Working together is the only way to make society understand HIV. After I got cancer in 2010, I wrote a book about my experiences. It’s called My Secret Life and is available on Amazon and other online bookstores. I never thought I would be living the life I am now. A life free from fear, a life of complete openness. I hope that someday soon, we will see an end to HIV, and I will continue to do my part in bringing this about.

What adjectives best describe you? Introverted, strong, empathetic.

What is your greatest regret? I cannot regret anything. Everything that has happened to me throughout my life is what has shaped me and formed the man I am today.

What’s the best advice you’ve received? When I am feeling down and complaining about my lot in life, a friend reminds me of the alternative. As long as you are alive, make the most of life that you can.

Read other POZ Stories or share your own at poz.com/stories.

These dates represent milestones in the HIV epidemic. Visit poz.com/aidsiseveryday to learn more about the history of HIV and AIDS. BY

HIV

Sir Elton John announces the launch of THE ROCKET FUND, a three-year, $125 million initiative to accelerate the end of AIDS. (2023)

15

VISUAL AIDS debuts the inaugural set of Play Smart safer sex trading cards. The cards use an honest and straightforward approach to promote pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), harm reduction and HIV testing. (2010)

21

BROADWAY BARES, an annual burlesque show and fundraiser for Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, celebrates its 25th anniversary. (2015)

27

26

Congress enacts the AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT, which prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities, including people living with HIV/AIDS. (1990)

NATIONAL HIV TESTING DAY

In a blog post titled “Ending the HIV Epidemic Requires States to Modernize Outdated HIV Crime Laws,” HIV.gov offers six tips on using a new tool from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Below is an edited excerpt.

HIV IS NOT A CRIME AWARE-

ness Day was launched in 2022 by the Sero Project in collaboration with the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation and other grassroots organizers, bringing together communities, people with HIV, governments and other partners to stand in unity against the harm caused by laws that use a person’s HIV status in criminal prosecution. February 28 was chosen to bridge Black History Month, Women’s History Month and several other HIV awareness days. Modernizing these laws is an essential element in ending the HIV epidemic. The National HIV/AIDS Strategy (2022–2025) recommends policies and priorities that can help end the HIV epidemic in the United States. Achieving the goals of this national strategy requires addressing stigma as well as structural barriers to HIV prevention and care. A key part of this effort is examining how laws and policies can inhibit positive change and exacerbate harm. The national strategy encourages reform of state HIV criminalization laws. All state laws and practices should be informed by science, but in the case of HIV criminalization laws, most are not. In addition, the implementation of HIV criminalization laws is not associated with reduced HIV incidence.

Modernizing outdated state laws and practices is necessary.

To help meet the National HIV/AIDS Strategy goals, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released the HIV Criminalization Legal and Policy Assessment Tool in 2022. This tool can help decision-makers identify opportunities to strengthen legal and policy protections for people with HIV by aligning laws and policies with evidencebased best practices.

As a follow-up to the release of the assessment tool, ChangeLab Solutions, with the Minority HIV/AIDS Fund funding from the CDC, partnered with the Association of State and Territorial Health O cials and the Network for Public Health Law to deliver in-depth training on operationalizing the tool.

The trainings covered four topics in the tool: 1) legal research and analysis; 2) HIV data privacy; 3) HIV testing and surveillance; and 4) HIV criminalization. The goal of these trainings is to facilitate discussion and support participating states in identifying action steps to address stigma and structural barriers to HIV prevention and care.

Here are some tips to help other states interested in using the assessment tool to analyze their laws and take action on this important issue:

• Identify and engage key partners in your state, such as community members living with HIV, public health organizations, community-based organizations, health care professionals and physicians, law enforcement professionals and state prosecutors.

• Convene a team to lead the development of a state strategy and action plan.

• Raise awareness in meetings and convenings with key partners about the harmful effects of stigmatizing language and about the science of HIV transmission to address common misconceptions about HIV that may hinder the implementation of evidence-based laws and policies.

• Have multiple organizations jointly host meetings with key partners and audiences to demonstrate the importance of HIV decriminalization.

• Involve people with legal expertise to analyze a state’s interpretation and application of laws affecting people living with HIV and develop a strategy to ensure that these laws are informed by science and promote health equity.

• Learn from other states that have recently reformed their laws. By taking these approaches, states can improve the well-being of people with HIV and ensure that laws are equitable and just. Q

Photos projected at the Madonna concert showed people lost to AIDS, including close friends.

In an opinion piece titled “Living for Love,” POZ contributing writer Mathew Rodriguez shares his thoughts about the emotional AIDS memorials during Madonna’s 2024 New York concert. Below is an edited excerpt.

IDON’T

walking into Madison Square Garden to see Madonna expected to cry, but I suspected I would—and I did.

Prior to seeing the Material Girl on a New York stop of her Celebration tour on a chilly evening in January—postponed from sweaty August 2023 because the superstar fell ill and was hospitalized with a bacterial infection last summer—I read that she dedicated a portion of her performance to a sort of living AIDS memorial, where as she sang “Live to Tell” she flashed pictures of people she knew, such as her dance teacher Christopher Flynn and artist Keith Haring, who died of AIDS-related illnesses.

I walked up the many stairs and escalators to my nosebleed seat expecting to be moved by the tribute. When it came along, heralded by a background dancer falling to the floor and breaking what had been up to that point the joyous mood brought about by her early hits, including “Holiday,” “Everybody” and “Burning Up,” I did,

of course, think of my father, who lived with HIV and passed in 2011. I thought about what it would be like to see his face plastered up on a screen alongside so many others. And I thought about what it meant that I conjured up his face in my own heart and about whom other people in the stadium might be thinking of at that moment.

But that wasn’t the only AIDS-related moment of the night, nor was it the one that affected me the most. Later in the evening, during the dedicated time when the superstar, sporting a cowboy hat and a guitar over her shoulder, spoke directly to the hushed, rapt audience, she talked about her time in New York City during the early days of the AIDS crisis.

She pointed to two people in the audience she knew, nurses Ellen Matzer and Valery Hughes, who wrote the book Nurses on the Inside: Stories of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic, which was published in 2019, just months before the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the world would once again be

reminded of the importance of nurses.

“I’m here to give thanks to them for being at the front line of the AIDS crisis so many years ago,” Madonna told the crowd. “Thank you for your bravery and courage.”

She then talked about visiting the AIDS ward at St. Vincent’s Hospital in New York’s Greenwich Village and how the ward was empty of people—no visitors—save the nurses caring for the sick at a time when nobody wanted to touch people with AIDS. Madonna thanked these women—whom she called angels and heroes—for doing their work. She also shared a story about seeing a young man in the AIDS ward, near death and no longer lucid, who believed that the woman visiting him was not Madonna but his own mother. She lay in bed next to him, and he said, “Mother, thank you for coming.”

Madonna spoke at length about nurses on another night during her New York stint, sharing that she had recently spent time in the hospital fearing for her own life and that the presence of

nurses had kept her in good spirits as she faced her own mortality. The idea of Madonna and death in the same sentence feels anathema, since her four-decade-plus career in an industry that denigrates and discards female artists, especially those who make pop or dance music, has made her seem near-invincible. Her longevity has ossified into mythology, the way some people say that a er the apocalypse, the only two things around will be cockroaches and Cher.

Madonna has spoken about her time in the hospital at other concerts. Many fellow concertgoers I spoke to considered her music career in the context of loss: the losses that marked the AIDS epidemic as well as the loss of her own mother, which she addressed at length in the documentary Truth or Dare and is the subject of several songs, including American Life’s “Mother and Father.”

Hearing Madonna speak about the power of nursing, I began to see her oeuvre as a dedication to mutual care and community. How much of her early music, including “Holiday,” are anthems about the power of a beat felt on the dance floor and the bodies and souls moving in rhythm with one

another? Madonna’s discography can be viewed through a lens of loss, but what shi s when you choose to view it as a call to care for one another, to nurse one another?

Later in the evening, she sang “Mother and Father,” a song casual Madonna fans may not know. It’s the penultimate track on one of the singer’s least popular albums. When she sang it, images of her

“Madonna was using the stage to fight back.”

mother and her adopted son David’s mother, who died of AIDS-related illness, were projected above the stage.

At a time when we are revisiting the way tabloid magazines lampooned female pop stars in the 2000s, Madonna was using the stage to fight back against the narrative that her adoption of children from Malawi was motivated by paternalism and suggesting that perhaps

it was more of a response to her own trauma related to the AIDS crisis, which Mary Gabriel describes in her Madonna biography, Madonna: A Rebel Life. Gabriel writes that Madonna’s visit to Malawi felt like “history repeating itself” and that she was moved to adopt children from the area because the visit reminded her of living in New York City in the early days of AIDS.

At the concert, I learned that Madonna held in equal regard the need to mourn the dead and the need to applaud those who care for the living. Although plans for a potential Madonna biopic have stalled, as I sat in Madison Square Garden, I thought maybe the milieu of the arena stage—in which Madonna is so at home—wasn’t cinematic enough.

Madonna had reminded the crowd that AIDS is bigger, more global, more diverse, more varied, more devastating, more personal, more all-encompassing than what many credit it for, something both universal and insular. When I walked out onto the sidewalk at 31st Street and Eighth Avenue, people were dancing to “Like a Prayer,” and I felt as though people had grasped the message; they were feeling together. We had, finally, gotten into the groove. Q

On February 20, 2024, the HIV community lost a fierce longtime advocate. Though she was only 39 years old when she died in her home in Las Vegas, Hydeia Broadbent had for more than three decades educated people around the world about HIV and AIDS.

Born with HIV in 1984, Hydeia was among the first generation of children born with the virus. When she was diagnosed with AIDS at age 3, doctors predicted she might not live past age 5. After all, effective antiretroviral therapy for HIV wouldn’t become available until the mid-’90s. But with the love and support of her adoptive

parents and her own positive attitude, Hydeia went on to thrive, fighting the stigma associated with the virus for the rest of her life.

At the suggestion of HIV advocate Elizabeth Glaser, who was taken with Broadbent’s vivacious nature and irresistible charm, Hydeia began publicly sharing her personal story at age 6. At age 7, she appeared on Nickelodeon with NBA star Magic Johnson; at age 11, she was a guest on The Oprah Winfrey Show; and in 1996, at age 12, she addressed the

Republican National Convention, boldly declaring, “I am the future, and I have AIDS.”

To the end, Hydeia used her platform to promote prevention, testing and treatment as acts of self-love and respect for others and her lived experience to spread hope.

3. Of Hydeia’s death, Magic Johnson posted on X: “By speaking out at such a young age, she helped so many people, young and old, because she wasn’t afraid to share her story and allowed everyone to see that those living with HIV and AIDS were everyday people and should be treated with respect.” 2

1. Hydeia graced the cover of POZ magazine twice: first In October 1996 (top right) at age 13 and again in April/May 2017. 2. On February 7, 2020, in observance of National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day, Hydeia posted a photo of her flanked by activist and professor Angela Davis, PhD (left), and politician and voting rights activist Stacey Abrams with the caption “Black women are taking the lead on Ending this Epidemic.”

4. In 2016, Hydeia toured Eswatini to educate young people to make informed decisions to stay HIV negative. 5. Actor Lamman Rucker presented Hydeia with Bounce TV’s 2020 Community Activist Award.

6. During her acceptance speech for GLAAD’s Vanguard Award in March, Oprah Winfrey (center), whose gay brother died of AIDS in 1989, noted that Hydeia, a guest on her show in 1996, used her life to empower others.

7. Las Vegas Councilman Cedric Crear presided over a public tribute to Hydeia, calling her a “national treasure.” 8. Rae Lewis Thornton (right) posed with fellow advocates Hydeia and Jeanne White Ginder, Ryan White’s mother, at an event in 2018. 9. At the Las Vegas stop of her Celebration tour, Madonna included Hydeia in her tribute to people who died of AIDS.

MODERN ANTIRETROVIRAL

regimens are highly effective and generally well tolerated, so treatment success o en comes down to consistent use.

Regular use is also a key to effective pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Adherence means taking the correct dose of medications every time as prescribed by a health care provider or recommended by a pharmacist.

To keep viral loads suppressed, the concentration of antiretrovirals in the body must be kept at a high enough level. If drug levels fall too low, the virus can resume replication, which can lead to immune system damage, disease progression and HIV transmission. Poor adherence can also cause drug resistance, meaning meds may stop working. With PrEP, inconsistent use raises the risk of HIV acquisition.

But taking pills every day is not always easy. Some people have di culty remembering to take their meds, or they don’t want to think about having HIV every day. Drug or alcohol use, depression and other mental health issues can interfere with good adherence. Concerns about side effects can make people reluctant to stick to their treatment. Some people are worried about having

pill bottles that could reveal their HIV status, or they may be in situations where their meds could be lost or stolen. Finally, if the cost of medications is a concern, people may be tempted to take them less o en to stretch their prescriptions.

Antiretroviral treatment and biomedical prevention have come a long way in recent decades. Many modern regimens require just one pill once daily with few or no food requirements. In addition, there are now long-acting injectable antiretrovirals that can be taken once monthly or less o en. Some people find it more convenient to take a pill every day, while others would rather visit a clinic periodically for a shot. Having more options makes it easier for everyone to find an HIV treatment or prevention regimen that works for them.

When starting treatment for the first time or switching to a new regimen, consider whether your lifestyle poses any potential obstacles to good adherence. For example, do you eat meals and go to bed at a consistent time? If you’re using a combination that requires multiple pills or more frequent dosing, ask your doctor whether a simpler regimen might be right for you. Talk to your health care provider if you are

struggling with drug side effects, substance use or mental health issues. If you’re having trouble affording your medications, talk to your doctor, case manager or an AIDS service organization about health insurance options and payment assistance programs.

Lapses in treatment adherence can happen to anyone. Don’t feel bad or guilty if you sometimes miss a dose, but do resolve to do better for the sake of your health and well-being. Q

• Make it a habit. Keep meds next to something you use every day, like your coffeepot or toothbrush.

• Beware of schedule changes. Some people have more trouble remembering their meds on days off from work or school or during a vacation.

• Meds on the go. If you need to take your medications while outside the house, check out portable pill cases— some even have built-in timers.

• Travel smart. Keep your meds in carry-on luggage and bring extra doses in case of flight delays or other unexpected events.

• Plan ahead. Regularly refill your prescriptions so you don’t run out.

The once-daily Biktarvy pill (bictegravir/tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine) can be a good option for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). PEP is a monthlong course of antiretrovirals taken within 72 hours a er a highrisk exposure. Current CDC PEP guidelines, last updated in 2016, recommend tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC; Truvada) plus either raltegravir (Isentress) or dolutegravir (Tivicay) for 28 days, but these regimens require two separate pills, and raltegravir should be taken twice daily. Researchers analyzed outcomes among 120 people who started PEP at emergency departments in Toronto a er sexual exposure. Those who initiated PEP with another regimen switched to Biktarvy. Adherence was high; 88% took PEP for at least 28 days. Biktarvy was generally well tolerated, and no HIV seroconversions occurred. Given the low incidence of seroconversion among PEP users, it’s di cult to demonstrate that one regimen is more effective than another, but these findings suggest that Biktarvy should be added to PEP guidelines.

Once-weekly oral treatment using the HIV capsid inhibitor lenacapavir (Sunlenca) and islatravir, a nucleoside reverse transcriptase translocation inhibitor, kept the virus suppressed as well as daily pills, researchers reported at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Daily antiretrovirals are effective, but some people can’t take pills every day. Some prefer long-acting injectables, but others don’t like shots or find injection appointments inconvenient. In a Phase II trial, 104 adults with viral suppression on Biktarvy (bictegravir/tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine) were randomized to stay on the daily pills or switch to once-weekly lenacapavir plus islatravir pills. In both groups, 94% maintained an undetectable viral load. The weekly treatment was safe with no clinically significant decreases in T cells. Other researchers reported early data for weekly oral antiretrovirals further back in the pipeline, including another nucleoside reverse transcriptase translocation inhibitor (MK-8527), an integrase inhibitor (GS-1720) and an NNRTI (GS-5894).

A small proportion of children who start HIV treatment very early may be able to maintain ongoing viral suppression a er stopping antiretroviral therapy (ART). In 2013, researchers reported on the Mississippi Baby, an infant born with HIV who started antiretrovirals 30 hours a er birth. She stopped treatment at 18 months but maintained viral suppression for more than two years before experiencing viral rebound. That case inspired the IMPAACT P1115 trial, in which 54 infants who acquired HIV during gestation started combination antiretroviral treatment within 48 hours a er birth. Six of the children met strict criteria for undetectable HIV and began a closely monitored treatment interruption at an average age of 5.5 years. Two of the children experienced relatively rapid viral rebound at three and eight weeks a er stopping treatment, but three girls and one boy achieved ART-free remission. One child maintained viral suppression for 80 weeks before experiencing viral rebound. The other three were still in remission at 48, 52 and 64 weeks.

Military veterans living with HIV received prostatespecific antigen (PSA) screening less o en and were diagnosed with prostate cancer at a later stage than HIV-negative veterans, a recent study showed. While prostate cancer is the most common malignancy among HIV-positive people in the U.S., it does not appear to occur more o en among these individuals than HIVnegative people. Using Veterans Aging Cohort StudyHIV data from 2001 to 2018, researchers identified 791 HIV-positive and 2,778 HIV-negative veterans with confirmed prostate cancer. Prior to diagnosis, men with HIV were less likely than HIV-negative men to receive PSA screening. At the time of diagnosis, more than 60% of men with HIV had a detectable viral load, indicating suboptimal treatment. HIV-positive veterans with prostate cancer had significantly higher PSA levels and were more likely to be diagnosed with intermediate or high-risk localized cancer or metastatic cancer. These findings suggest that prostate screening should be a priority for men living with HIV.

Long-acting injectable treatment can be an effective option for people who cannot maintain viral suppression on daily pills, researchers reported at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI).

The LATITUDE trial enrolled more than 400 people who had a persistent detectable viral load on oral treatment or had been lost to clinical follow-up. They first used a standard oral regimen while receiving comprehensive adherence support and financial incentives. Those who achieved viral suppression were then randomly assigned to stay on the pills or switch to once-monthly Cabenuva (injectable cabotegravir and rilpivirine). A er a year, 24% of people on Cabenuva experienced virological failure or stopped treatment, compared with 39% of those on the daily regimen.

But some people are not able to achieve viral suppression using daily pills. For them, starting injectables directly could be a feasible alternative. The team at the Ward 86 HIV clinic in San Francisco previously reported early results from a pilot study showing that 55 of 57 people who started Cabenuva with a detectable viral load achieved viral suppression. At CROI, they reported that 81% were still on Cabenuva with viral suppression a er a year of treatment.

Based on this and other small studies, the International Antiviral Society–USA recently released updated guidelines

stating that Cabenuva may be considered for people with a detectable viral load who are unable to take pills consistently, have a high risk of HIV disease progression and have virus susceptible to both drugs “when supported by intensive follow-up and case management services.”

A major limitation of Cabenuva, however, is resistance to NNRTIs like rilpivirine. A case series of 34 patients suggested that combining injectable cabotegravir with the long-acting HIV capsid inhibitor lenacapavir (Sunlenca) could be an effective alternative. Ward 86 medical director Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, and colleagues called for clinical trials of this regimen, which could be especially beneficial for people living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries where NNRTI resistance is more common.

It’s a common belief that daily pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) pills do not protect cisgender women as well as gay and bisexual men. Studies have found that tenofovir levels are lower in vaginal and cervical tissues compared with rectal tissue, suggesting that women may need to take PrEP more consistently. But further analysis shows that protection depends on adherence, not biological factors.

A mathematical modeling analysis of real-world data from 11 post-marketing studies, mostly conducted in Africa, found that tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/ emtricitabine (Truvada or generic equivalents) was highly effective for women who took at least four doses per week. None of the women who took PrEP pills every day acquired HIV. Among those who took four to six doses per week, only one seroconverted, similar to the incidence rate for gay men. Although daily adherence is optimal, a minimum of four doses per week “is expected to provide effective protection for most females,” the researchers concluded. However, less than 40% of the women in the studies achieved this level of adherence, suggesting that long-acting injectable PrEP may be a better option for some cisgender women.

“By combining data from several moderately sized studies, we have revealed a trend in prevention-effective use that suggests brief dosing interruptions should not stop cisgender women from experiencing the potentially life-changing benefits of oral PrEP,” says National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, MPH.

The early rollout of doxyPEP in San Francisco has contributed to a decline in sexually transmitted infections (STIs), according to reports at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. DoxyPEP refers to taking a single prophylactic dose of the antibiotic doxycycline within 72 hours a er sex.

San Francisco was the first city to issue local doxyPEP guidelines in October 2022, and it is the first to see real-world outcomes. At the San Francisco AIDS Foundation’s Magnet clinic, 1,209 PrEP users, mostly gay and bisexual men, were prescribed doxyPEP through September 2023. STI incidence fell by 58% overall but more so for chlamydia (67%) and early syphilis (78%) than for gonorrhea (a nonsignificant 11% drop).

DoxyPEP is also having an impact at the local population level. More than 3,700 gay and bi men and transgender women started doxyPEP at Magnet and two other local clinics by the end of 2023. Chlamydia cases in this population decreased by 50% and early syphilis decreased by 51% relative to predicted levels. But again, there was no significant decline in gonorrhea.

These findings back up evidence from clinical trials showing that doxyPEP can reduce chlamydia and syphilis, though it is less effective against gonorrhea. “The evidence now overwhelmingly supports the use of doxyPEP for STI prevention, and we see benefits of an aggressive rollout to the populations who are most likely to benefit,” says San Francisco AIDS Foundation medical director Hyman Scott, MD, MPH.

People living with HIV are at greater risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) compared with the general population, but managing risk factors can make a big difference.

Researchers at Kaiser Permanente Northern California analyzed CVD risk factors among people with and without HIV. In general, both groups had similar high levels of risk management. Overall, people with HIV had about a 20% higher risk for cardiovascular events. HIV-positive people with no traditional CVD risk factors still had more events than their HIVnegative counterparts, indicating that HIV-specific factors, such as inflammation, play a role. CVD risk was lessened in HIV-positive people with well-controlled blood lipid levels and diabetes, but their risk remained elevated despite well-controlled hypertension.

People with HIV may require CVD management at lower thresholds. An analysis from the REPRIEVE trial confirmed that a standard CVD risk calculation underestimates risk for people with HIV, especially women and Black people. REPRIEVE showed that a daily statin reduced the risk for heart attacks, strokes and other major cardiovascular events by 35% among HIV-positive people with low to moderate CVD risk, a group that ordinarily would not be prescribed statins. Based on these findings, the Department of Health and Human Services recently updated its guidelines to recommend statins for people with HIV ages 40 and older with low or intermediate CVD risk.

Another study conducted in Haiti showed that HIV-positive people with “prehypertension,” or blood pressure slightly above the normal range, were 57% less likely to develop hypertension if they received early treatment with a calcium channel blocker. Lowering the threshold for antihypertensive treatment for people living with HIV “may be an important tool for cardiovascular disease prevention,” says Lily Yan, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine.

ON A LATE MORNING IN MID-FEBRUARY, JIRAIR RATEVOSIAN WAS chatting on the phone with POZ from an apartment in Burbank, California, that he’d rented so that he could run for the U.S. congressional seat to be vacated by Representative Adam Schiff (D–Calif.), who has represented this deep-blue district since 2001.

It’s the district that Ratevosian, 43, the son of an Armenian father and a Lebanese mother, was born in. There are roughly 200,000 Armenians in LA County, the largest such population outside of Armenia.

When asked whether he’d reached out to LA’s most famous Armenian for support, Ratevosian, who is gay and already has the bulleted-talking-points conversational style of a seasoned politician, retorts, “Do you mean the Kardashians or Cher? We’re actively reaching out to both.”

His campaign was also reaching out to celebrities who have been instrumental in fighting HIV and AIDS, including Sheryl Lee Ralph and Alicia Keys. This is because Ratevosian, who is HIV negative, has made ending HIV and AIDS his mission—a career trajectory he aimed to take straight to the Capitol.

“I want to be the AIDS activist in Congress,” Ratevosian says. He wants to assume the lead HIV and AIDS advocacy role played for the past quarter of a century by Representative Barbara Lee (D–Calif.), who was vacating her seat to run against Schiff in the Democratic primary for the Senate. Ratevosian worked in Lee’s office for three and a half years and calls her “the boss of the HIV movement.”

But Ratevosian, who has an MPH from Boston University and a DrPH from

Jirair Ratevosian ran for Congress as an AIDS activist.

Johns Hopkins University, was facing a crowded field of 15 candidates—and he wasn’t even the only LGBTQ candidate or the only Armenian candidate vying for the seat. With his relatively low profile—compared with, say, fellow contender Laura Friedman, already well established in the district, having held previous elected positions—why did he think he had a chance?

“Because I haven’t been afraid to stand alone and fight,” he answers. “That’s been my life’s work, even when it’s not popular.” He claims that he was the first candidate in his race to call for a cease-fire in Gaza. He says not everyone in LA’s Armenian community was happy about his being an openly gay Armenian. “My Twitter and Instagram are full of hate,” he says. “People saying I shouldn’t be both gay and Armenian—that I should pick one.”

Further to why he felt he had a fighting chance, he says, “I’m the only one in the race with such deep roots in LA.”

Other strong points, he says, were “my lived experience as a gay man and the son of Armenians who embody the American dream.”

RATEVOSIAN WAS BORN IN HOLLYWOOD in 1980 but grew up attending Armenian Christian private schools in Sun Valley, just outside LA. “I was a teacher’s pet but also someone who was expelled from first grade because once at recess I opened the gates and all the kids ran out,” he says. “Maybe I was a Che Guevara in the making.”

Despite that early infraction, he went on to become a straight-A student. “I wanted to be a doctor,” he says, adding that it was one of the preferred professions in LA’s ambitious Armenian community. He was also a political junkie. “I loved reading the news and watching President Reagan”—beloved by his Republican family—“when he would speak on TV.”

“because I was so offended to learn that there was lifesaving HIV treatment available in the United States but not in South Africa.” The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) to fight the virus in poor nations had only just launched.

Ratevosian decided to go into public health “to have a larger impact on people’s lives than being a physician,” he says. “It’s that restless gene I have.” He went to public health graduate school at Boston University, which included spending eight weeks in Kenya in 2005 to finish his practicum. After he graduated, he served on Boston’s Ryan White HIV Planning Commission for a year.

“That’s when I first learned about a lot of the inequities in terms of how resources are sent to cities,” he says. People living with HIV and their advocates would regularly attend the meetings to talk about their needs. “It was the first time I was seeing the power of HIV advocacy.”

In high school, where he was class president, he says he had no gay desires or even the idea that he was gay. “I went to prom and was madly in love with this one girl,” he says. But he does remember the moment in 1991 when LA Lakers superstar Magic Johnson announced that he had HIV. “My father was a big Magic fan and was very distraught over the news.”

Ratevosian studied physiology and political science at the University of California, Los Angeles, and graduated in 2003, after which he started a medical postbaccalaureate at the University of California, San Francisco. While there, he won a scholarship from National Geographic to practice photography in South Africa.

“I was there to take photos of nature,” he recalls, but one day he visited an HIV clinic run by Doctors Without Borders. “That’s the moment I credit with changing my life,” he says,

Ratevosian vows to keep working to end the HIV epidemic.

But even in Boston, miles from home, his gayness remained latent. “I remember watching Angels in America and wondering if I was suppressing something,” he says. Nonetheless, by this point, he was completely devoted to HIV work and had moved to Washington, DC, where he worked for Physicians for Human Rights, before becoming deputy director of public policy for amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research, where he worked on syringe access programs.

He also volunteered at a DC needle exchange as well as at the WhitmanWalker LGBTQ health clinic, for which he did HIV testing at the Crew Club, the local gay bathhouse. “I saw tons of people, most of them young and Black, who’d find out they were HIV positive and start sobbing in despair and hopelessness,” he recalls. “We didn’t know about U=U at the time,” he adds, referring to the Undetectable Equals Untransmittable message, which means that people living with HIV who are on treatment and have an undetectable viral load do not transmit HIV through sex.

At this time, Ratevosian says, “I had tons of gay friends and was part of the HIV community,” but still “no one knew I was gay.” Afraid that his family and the Armenian community back home would reject him, he was keeping himself closeted.

In 2011, Ratevosian started working as Lee’s legislative director. “She was the idol of the HIV policy community, the only one who was hearing us,” he says of the congresswoman. He said his “crowning moment” during his three-and-ahalf-year tenure in her office was serving as lead staffer on the reauthorization of PEPFAR.

Working for Lee, Ratevosian says, “I learned that you could be progressive and stay true to your core values but also work with people who don’t agree with you to get things done.” He also learned “how lobbyists and other special interests with money can influence members of Congress.”

RATEVOSIAN LEFT LEE’S OFFICE IN 2014 to become the director of government affairs for Gilead Sciences, the HIV pharmaceutical giant, where, he says, “I saw myself as an insider who was helping my community advance things related to the HIV response.” After two years, the company relocated him from DC to San Francisco, where his participation in the AIDS/LifeCycle fundraising event sparked him to finally come out to family and friends.

His friends were fine with it—“we did shots to celebrate,” he recalls—but his parents were a mixed bag. “My dad hugged me and said that he and my mom were proud of me, but my mom cried and said, ‘We shouldn’t have let you go to Boston. We want you to be married and have kids.’ I told her that I could do all those things. They didn’t know it was possible to be gay and happy.”

His big public coming-out occurred in 2023 when The New York Times ran a story on his wedding to Micheal Osa Ighodaro, a Nigerian LGBTQ and HIV-positive activist who was granted asylum in the United States in 2013. Ighodaro currently works for the Prevention Access Campaign, which promotes the U=U message, and is also cofounder and executive director of the group Global Black Gay Men Connect.

The couple met in 2019 at a Brooklyn party thrown by mutual friends. After that, they would grab drinks together at various HIV-related conferences. Then, in 2020, Ratevosian invited Ighodaro to canvass for Joe Biden with him in Iowa, which is when their romantic relationship began.

Ratevosian’s parents. “My parents love Micheal so much and sensed he needed that extra TLC,” says Ratevosian.

Laura Friedman won the primary for the 30th Congressional District with 30% of the total vote—well ahead of any other candidate, including Ratevosian, who came in ninth out of 15 candidates, with 1.9% of the vote.

Talking with POZ a few days later, Ratevosian says, “I’m feeling disappointed but proud.” Whereas some of his rivals had over $1 million in campaign funds, he had about $350,000, which he says was an impressive sum “for a firsttime candidate not backed by special interests or PACs. Nobody was pushing me to run except for the HIV and public health communities, and we all know,” he says with a laugh, “that those groups don’t have money.”

He sent a thank-you email to his supporters that read, in part: “Although we don’t see a path to victory with the votes currently counted, I could not be prouder of how we ran this campaign. From being the first candidate to call for a cease-fire [in Gaza] to standing up for the rights of all LGBTQ people, I’m proud of the values that this campaign stuck to even when the going got tough.”

“NO ONE GOES TO CONGRESS ANYMORE WANTING TO FIGHT AIDS.”

“He’s the kindest person I know,” Ighodaro says of Ratevosian. “He has a very big heart and a sense of humility and is very funny but is also very pragmatic.” The two have shared each other’s cultures. Indeed, Ighodaro has learned about Armenian and Lebanese food, including the honeydrenched phyllo dessert baklava, and has cooked Nigerian staples like jollof rice for Ratevosian’s family.

Plus, says Ratevosian, his parents love Ighodaro, which has helped them accept their son’s gayness. “Micheal had an even more difficult experience than I did coming out to his family,” he says. And Ighodaro adds, “I’m far from my family, but Jirair’s family is definitely my family now.”

When POZ spoke with Ratevosian, Ighodaro had finally traveled west to live in Burbank with him and their fluffy white dog, Jozi Ruth, to help him on the campaign. In addition to catching movies together and hanging out in the West Hollywood gay bars, the couple has dinner weekly with

He also lamented that Adam Schiff— the very person whose congressional seat Ratevosian had been vying for—had beat Barbara Lee in the Senate primary race.

In other words, he says, there would soon no longer be even one longtime hardcore champion of HIV issues in Congress—at a time when right-wing Republicans are breaking with decades of bipartisan support for such issues, with some questioning ongoing funding for PEPFAR and domestic HIV efforts, like the Ending the Epidemic initiative.

“No one goes to Congress anymore wanting to fight AIDS,” he says. While on the campaign trail, Ratevosian found it alarming to learn how many citizens lacked faith in government—and even more alarming that many young people lacked the faith to vote.

Meanwhile, he adds, offers for his next chapter were arriving, but he wanted to use some of the time without a job to reflect. “This campaign was in pursuit of an opportunity to continue the work I’ve always done for health justice, but it didn’t work out. So I’ll take time to think about where else my experience, energy and passion can be transferred to.”

Ratevosian says that he will continue his HIV work. He is looking to do a postdoctoral fellowship at Yale University focused on breaking barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis access for Black and Latino gay and bisexual men. “When I was working for Representative Lee,” he says, “even when we were working on U.S. policy in Afghanistan, we were working the same day on Ryan White funding. HIV has been the common denominator for me all along.” Q

ISCLOSURE CAN BE DIFFICULT FOR PEOPLE

living with HIV even when a TV camera isn’t filming their every move, which helps explain why RuPaul’s Drag Race contestant Q’s announcement that she is HIV positive not only made for an emotional scene but also went viral. Q makes it clear that the moment wouldn’t have happened if she hadn’t felt secure in this reality-TV sisterhood. “I would have felt comfortable telling any of those girls,” she tells POZ, citing her fellow queens on season 16 of the Emmy-winning show. “They all made it feel like just a safe space where I could feel free

to come out with that information.”

When she came out as HIV positive, Q joined a lineage of people who have shared their status with American TV audiences, including pioneers like The Real World ’s Pedro Zamora and past Drag Race queens Ongina and Trinity K. Bonet. While speaking with POZ, Q also discussed the red ribbon dress she crafted for the runway, her relationship with her care provider and what it was like to see her moment of disclosure become a social media meme.

When you were diagnosed as HIV positive in 2021, at age 24, what went through your mind?

I was diagnosed in July of 2021. When you’re diagnosed, you feel so isolated; you feel very, very alone. It almost feels final, like the end. I think that’s why it’s so hard for so many people and definitely why it was so hard for me.

When you were diagnosed, you had already been doing drag. Did your art as a drag performer—or your drag community—help you process it at all?

My drag family supported me so much when I told them. I was lucky to have them and lucky to have my husband. Some people go through it alone. I can only imagine how hard that would be, because I definitely give a lot of [credit for] how well I moved on from that diagnosis to my drag family, my husband and the people around me.

I want to ask about the dress you made for Drag Race that featured the AIDS awareness red ribbon and art inspired by Keith Haring. Can you talk about where you got the idea for the dress while you were making your runway package for the season?

When I knew that we were doing an ’80s runway, I thought this was an opportunity for me to be more open about my status and give myself an ultimatum to talk to my family about it and be a voice for anybody who felt as scared as I did. I just really wanted to pay homage to the generation of queer people that we lost and that could still be alive and thriving today had politicians and government and health officials taken it more seriously and cared more about queer people in general.

I saw it as an opportunity to be a visual for anybody who is positive or who is recently diagnosed and feeling the same things that I felt because maybe they don’t have anybody at home with them. And if they see me, you know, maybe they at least feel not so alone.

You mentioned on the show that you had not discussed your HIV status with your family before talking about it on Drag Race. Disclosure on national television is such a huge deal. Were you more worried about disclosure to your family or being so visible to the world?

I honestly have no problem being publicly visible as someone who’s living with HIV. It’s not something I carry shame for. Sometimes, with the stigma that you have to face, people want you to feel shame for it. But I myself got into a place where I want to live openly about it and be a public figure and a visual aid for people living with it.

But I was more scared for my family. I talked to my mom before the episode aired—she knows, and my family knows. My mom worries when it rains too much outside. Thinking about her worrying about that—that’s what made me anxious. I know how I’ve been treated differently by some people because of my HIV status, which definitely made me cautious about telling certain people.

When you came out on Drag Race you mentioned that you had faced stigma from health care providers. What was that like, and what is your relationship with your doctor like now?

I have a primary care physician right now that I’m close with and who’s not queer but deals with a lot of queer people and is super knowledgeable. I went to a dermatologist because I had issues with my skin, and getting them to move past thinking that what was going on with my skin was HIV related was a challenge. It had been going on since before my diagnosis. Facing that was difficult.

The dermatologist was seeing you only as your status. Yeah, exactly. It’s honestly just hard to find doctors to trust or to find doctors that are versed in queer culture and the community. My husband and I are in an open relationship. My original HIV doctor just seemed to have no grasp on queer relationships or the community that I live in. It was difficult to even talk to them sometimes just because they were so out of touch.

For people with HIV, disclosure is such a big deal. And now you’ve done that on a national stage. Do you have advice for people with HIV struggling with or thinking about disclosure?

Definitely do it when it feels right for you. Don’t let anybody let you feel pressured because ultimately the decision is up to you. That’s your life. That’s your business. But if you do, make sure you have a good support system and people around you that love you. No matter how your disclosure is taken, there are people out there that love you and support you and see you for the amazing person you are

When you did disclose on the show, you chose to share with Plane Jane. Was there a reason you came out to her specifically?

We worked together that episode, and we were sitting by each other, and Plane’s also somebody I got close with on the show. Honestly, I would have felt comfortable telling any of those girls because we all got so close, and we’ve all been such big supporters of each other. They all made it feel like just a safe space where I could feel free to come out with that information.

That moment has become kind of a meme, specifically with Plane saying, “Mama, kudos for saying that—for spilling.” What is it like for you to see that go viral?

It’s so weird, because it didn’t feel like something that was super funny or awkward in the moment. Seeing it out of context, I can definitely see how it’s an awkward phrasing of, “Oh, mama, kudos for spilling,” after something so sincere. When she said that in person, she was very sincere, and it didn’t come off as not caring. We didn’t even think about it as something that would blow up or be funny. Somebody sent me one where Grindr posted a version with someone listing a million things they’re into, and somebody replied, “Mama, kudos to you for spilling,” and I was like, “Oh my God!” Q