33 minute read

Piccola riflessione sulla realtà virtuale

from Connessioni N. 54

by Pentastudio

Senza dimenticare AR e XR

Chiara Benedettini

Quando si parla di VR si pensa in prima battuta a tecnologie e linguaggi di programmazione, ma vanno tenuti in altrettanta considerazione anche gli aspetti cognitivi e il loro evolversi nel tempo.

Ecco alcune considerazioni e una intervista con Enzo d’Annibale, esperto di VR e collaboratore al CNR, per approfondire le applicazioni, le possibilità di sviluppo e le implicazioni percettive e psicologiche della VR/AR/XR

Tra 2020 e 2021 si è molto parlato della Realtà Virtuale (o VR- Virtual Reality), e da molti punti di vista: via via è stata l’ipotesi di uno spazio diverso dove riunirsi per lavorare (o anche solo per incontrarsi) quando non è stato possibile farlo in prima persona, oppure l’ambiente dove organizzare una fiera, o ancora il contesto nel quale alcune aziende hanno presentato nuovi prodotti e applicazioni. Si veda per esempio il caso di Sony che tra aprile e maggio 2021 ha lanciato Spark, un ambiente immersivo che riproduceva lo stand di ISE, da esplorare con una visione in prima persona e nel quale fruire presentazioni, contenuti, tutorial ecc. Anche noi nella primavera del 2020 ci siamo cimentati con la VR lanciando Active Spaces Virtual, un ambiente immersivo con finalità formative e di networking da vivere con un avatar, dove svolgere gli eventi che avevamo programmato e che come tutti non abbiamo potuto realizzare in presenza; una alternativa ai Webinar che rispondono solo in parte alle necessità di relazione tra i partecipanti. La Realtà Virtuale è stata anche una suggestione e un desiderio per molti durante il lockdown, un ambiente parallelo nel quale vivere quanto il Covid ci ha negato per diversi mesi, da una passeggiata all’incontro con gli amici, alla possibilità di fare un viaggio. Fatto sta che, per quanto si pensi alla VR come a una opportunità anche nel dopo Covid, nell’ottica di trarre la migliore sintesi tra quanto ci ha insegnato la pandemia e la ritrovata “normalità”, ancora in molti non la ritengono matura per il grande salto. Tuttavia, la causa appare più legata a ragioni di tipo cognitivo (come viviamo e percepiamo l’esperienza del mondo esterno attraverso i sensi e il proprio bagaglio di conoscenze), piuttosto che a ragioni tecnologiche. La tecnologia quindi potrebbe essere pronta, ma siamo noi a non saperla ancora usare al meglio? È quindi necessario spostare il punto di vista?

BREVE VADEMECUM DEI CONCETTI DI VR/AR/XR

Siamo certi che i nostri lettori sanno già molto bene di cosa stiamo parlando, tuttavia concentrarsi sulle parole spesso porta a delle sorprese. Forse in pochi sanno infatti che la VR non è un concetto recente: senza voler scomodare Platone che in uno dei suoi ultimi Dialoghi, Timeo, ipotizzò che la realtà fosse costruita da minuscoli triangoli che cuciti insieme possono riprodurre qualunque realtà, fu Morton Heilig nel 1962 a creare una sorta di cinema esperienziale con il Sensorama, mentre il termine VR risale al 1989, quando Jaron Lanier fondò la VPL Research con l’intento di creare linguaggi di programmazione virtuale. Oggi il termine si è molto allargato e non si riferisce solo a una esperienza immersiva, ma in generale alla simulazione virtuale creata con un computer, fruita anche tramite un normale schermo che funge da “finestra” con la VR.

Tornando alle parole, con Virtual Reality si intende la creazione o la simulazione di un ambiente o situazione reali tramite un computer ed eventualmente interfacce che fungono da estensione del corpo. Quindi la VR si vive in prima persona! La Augmented Reality è invece un ampliamento o integrazione della realtà con immagini create virtualmente, che modificano l’ambiente originario senza influire sulle possibilità di interazione del soggetto con la realtà. La Mixed Reality è infine più della somma di entrambe: si intende la fusione tra il mondo fisico e quello reale grazie a strumenti quali la grafica 3D, la visione artificiale, l’elaborazione dei dati e dei contenuti in generale. Il termine si è precisato nel 1994*, e nel tempo è stata approfondita la relazione tra input umano e quello del computer; ma è la combinazione tra l’elaborazione del computer, l’input umano e l’input ambientale che dà vita a esperienze di realtà mista. Come si vede, il corpo, l’esperienza personale e la percezione (dato anche dal punto di vista unico e irripetibile di ognuno di noi), continuano ad avere un ruolo fondamentale anche nella Realtà Virtuale.

* Il termine realtà mista è stato coniato nel 1994 in un documento a cura di Paul Milgram e Fumio Kishino: A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual Displays, (Tassonomia dei dispositivi di visualizzazione nella realtà mista).

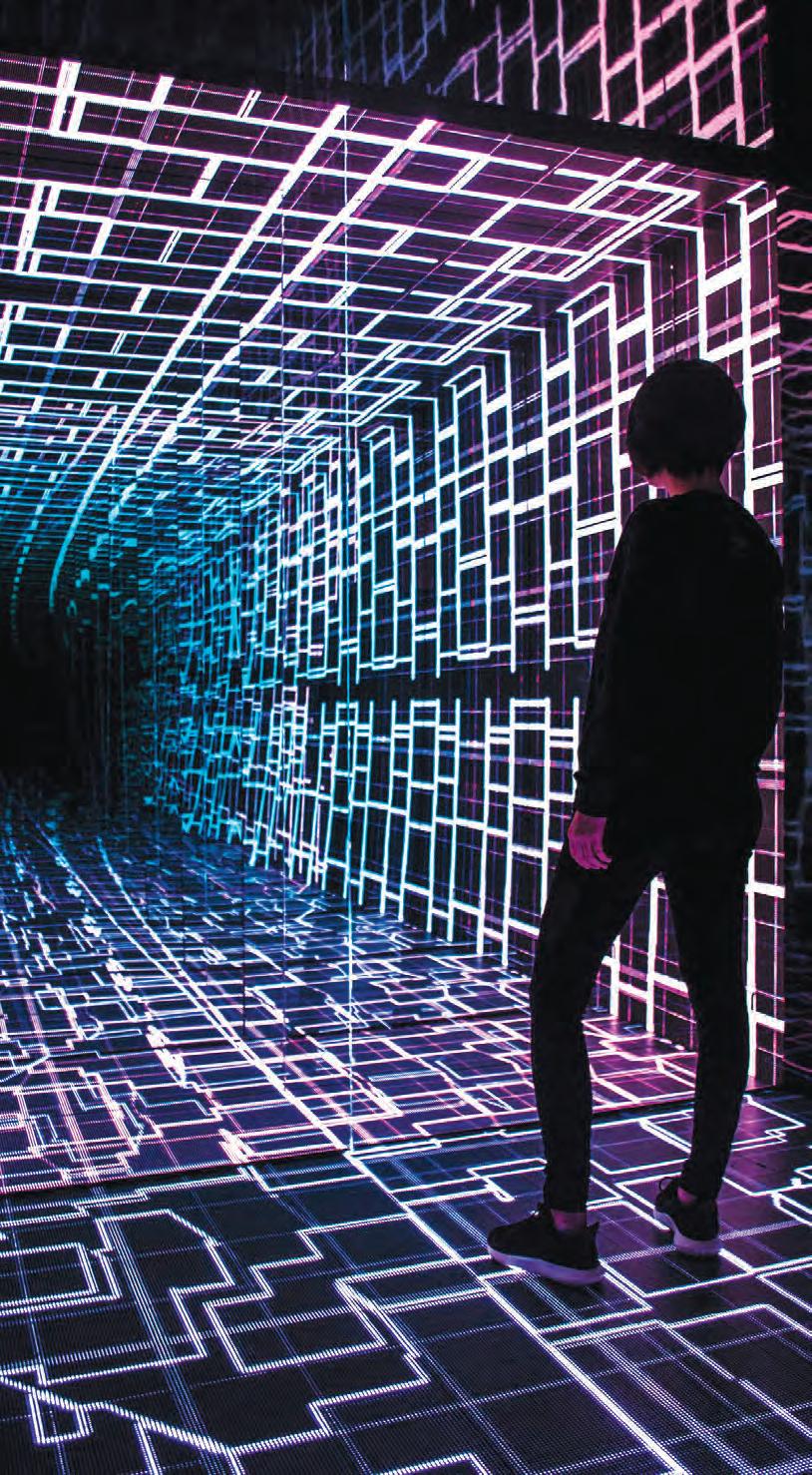

IMMERSIVITÀ ED ESPERIENZA COGNITIVA NELLA VR

La presenza e l’immersione nell’ambiente, come si vede, sono i caposaldi della Realtà Virtuale. Con “presenza” si può intendere il livello di realismo psicologico di cui un soggetto fa esperienza nell’interazione con il mondo virtuale, nel rapporto istantaneo con l’ambiente e in maniera coerente rispetto alle aspettative e alle previsioni. Ad esempio, se si lascia la presa di un oggetto ci si aspetta che questo cada a terra e non fluttui nell’aria. Dal punto di vista psicologico, l’immersione si realizza con il coinvolgimento e l’impiego delle risorse cognitive del soggetto. Riprendendo l’esempio del corpo lasciato cadere, l’immersione è data non solo dalla sensazione tattile dell’oggetto che scivola via dalla mano, dal suono prodotto all’impatto col terreno e dalle conseguenze visive dell’azione, ma anche (ad esempio) dall’attivazione dei processi automatici legati al tentativo di riprenderlo prima che tocchi terra e si danneggi. Tuttavia, anche se l’esperienza della VR riguarda tutti i sensi, dall’udito all’olfatto, è la vista quello prevalente nell’uomo, così che molte delle periferiche e applicazioni per la VR si concentrano sulla vista. Sono già diversi infatti i visori in commercio, come i tool di modellazione 3D hanno raggiunto livelli di grandissimo dettaglio, grazie anche all’arrivo del 4K e ora 8K, mentre in pochissimi dispongono di “wired gloves”. Le tecnologie utilizzate nella VR sono: • Software e tool di modellazione 3D, a partire sia da materiale reale (foto e filmati, per intendersi), che prodotto sinteticamente (dati e coordinate di oggetti e luoghi, per esempio). Uno dei linguaggi più utilizzati per la creazione di mondi virtuali è il VRML (Virtual Reality Modeling Language). • Visori; i più conosciuti sono Oculus, Samsung HMD Odissey, oppure Hololens di Microsoft, basato su tecnologia olografica; in ambito gaming, Playstation VR; • Auricolari, per riprodurre suoni spazializzati; • Wired gloves; guanti dotati di sensori capaci di registrare i movimenti, ma anche le accelerazioni, consentendo l’interazione con lo spazio e gli oggetti virtuali; • Cyber-tuta; una tuta che avvolge il corpo. Può avere molteplici utilizzi, può simulare il tatto flettendo su se stessa grazie al tessuto elastico, o realizzare una scansione tridimensionale del corpo dell’utente e trasferirla nell’ambiente virtuale.

Ma se è vero che potenzialmente la Realtà virtuale ha tutte le carte in regola per permetterci di vivere esperienze potenti, dirette, in prima persona, della realtà virtuale o mista che sia, e che anzi ci prometta, proprio attraverso il nostro sistema cognitivo, di poter vivere esperienze “accelerate” ebbene, che si tratti di formazione, lavoro o intrattenimento, ancora non abbiamo raggiunto lo stato di una esperienza ottimale e user friendly al 100%. Sappiamo, insomma, che si può ottenere di più.

L’ipotesi potrebbe quindi essere che il punto da valicare non sia di tipo tecnologico, ma risieda in ragioni cognitive. Fino ad oggi gli strumenti per la VR si sono concentrati molto sull’esperienza visiva, tuttavia sappiamo che anche gli altri sensi hanno un ruolo fondamentale nella percezione della realtà. Anzi, udito e olfatto in particolare, sono sensi che ci riportano a dimensioni molto profonde del nostro vissuto, attingendo anche all’inconscio della persona. Ed è spesso l’udito che, ancora prima della vista, ci avverte di pericoli, o di qualcosa cui dobbiamo prestare attenzione. Quindi, dato che la tecnologia risulta matura, potrebbe essere utile concentrarsi maggiormente sulla percezione a tutto tondo, partendo proprio da udito e olfatto.

Un’altra strada, di cui la letteratura e il cinema si sono appropriati come potente suggestione per storie appassionanti – vedi i film Avatar di James Cameron, o il romanzo Shovel Ready di Adam Sternberg – è la possibilità di bypassare l’aspetto fisico dell’uomo per mettere in relazione direttamente le periferiche con il cervello dell’utente (il cosiddetto Wetware), vero centro di ogni nostra percezione.

LE APPLICAZIONI DI OGGI E DI DOMANI

A fianco delle enormi possibilità della VR nel gaming e nell’intrattenimento, con la possibilità di creare mondi possibili, realistici ma non necessariamente reali, nelle applicazioni business la VR viene spesso utilizzata per ricreare proprio ambientazioni reali o comunque realistiche, di quanto è troppo lontano, difficile da raggiungere – fisicamente o materialmente – o rischioso. La VR si utilizza già con successo nella progettazione, anche nella direzione della prevenzione di inefficienze, errori ecc. In questo senso si utilizza anche nella meccanica, per predire debolezze delle varie parti e anticipare o localizzare i guasti. La formazione già utilizza la VR, non solo per ricreare ambienti di studio, ma anche per studiare senza rischi nel campo della medicina, della biologia, con potenzialità ancora tutte da inventare. Un altro campo che già trova beneficio nella VR è il marketing, anche se ancora di nicchia: non è difficile immaginare il vantaggio di poter andare più volte nello stesso negozio senza fare un’ora di tragitto, di progettare in prospettiva immersiva la propria cucina, senza contare i vantaggi per chi deve presentare a potenziali clienti case, barche, ambienti ancora sulla carta ma che possono vivere intorno a noi grazie a un visore e a due sensori.

LA VR NELLA RICERCA E NELLA FORMAZIONE

Per approfondire la VR in una applicazione a cavallo tra il mondo della formazione e della ricerca abbiamo intervistato Enzo d’Annibale: ingegnere, borsista post dottorato presso il CNR – ISPC (Istituto di Scienze del Patrimonio Culturale), ma anche designer freelance e progettista di esperienze immersive, parte del gruppo di lavoro WhatWeAre specializzato in esperienze immersive, italiano ma da molti anni in Svezia. Con Enzo, però, non abbiamo parlato solo dei vantaggi di ricreare virtualmente il mondo di 2.000 anni fa per poterlo studiare meglio, ma anche dello sviluppo di queste tecnologie.

Enzo d’Annibale - Mi occupo di applicazioni VR nel campo dell’archeologia; alla riproduzione virtuale 3D di manufatti o interi siti attraverso un lavoro multidisciplinare, integriamo informazioni aggiuntive e spesso ricostruzioni archeologiche del passato. In pratica simuliamo quello che non possiamo (più) vedere, ma che è stato reale un tempo. Sviluppiamo strumenti per la fruizione degli scenari virtuali non solo per gli specialisti, ma per un pubblico più ampio, in particolare quello dei musei. In ambito professionale mi sono spesso occupato della progettazione e dello sviluppo di tool per la realizzazione di video proiezioni immersive o di espedienti teatrali come gli ologrammi, o meglio Pepper’s Ghost. Per fare un esempio, nel corso del mio primo progetto per musei in Libia abbiamo prima ricostruito virtualmente architetture e sculture sparse nel vasto territorio, in luoghi desertici e difficilmente raggiungibili, poi abbiamo riprodotto i siti all’interno del museo di Tripoli sotto forma di ologrammi o di virtual tour. Ci puoi dire qualcosa di più sul tuo gruppo di lavoro? L’ISPC – l’Istituto di Scienze per il Patrimonio Culturale - si occupa di valorizzazione dei beni culturali utilizzando discipline umanistiche, scientifiche e applicazioni tecnologiche; io faccio parte di un gruppo che fa ricerca in ambito archeologico utilizzando le tecnologie di rilevazione, ricostruzione virtuale 3D e digital storytelling. È composto per lo più da archeologi – a parte me, un informatico e una esperta di user experience – anche se molto lontani da una archeologia con lo scalpello; molti sono, o sono diventati, abili modellatori e capaci programmatori.

Prima di approfondire, come si diventa esperti di VR? Non ho seguito un percorso di formazione specifico, ho iniziato utilizzando strumenti di simulazione 3D durante il corso di laurea in Ingegneria Edile Architettura. Ho coltivato la passione per la fotogrammetria, ovvero la scienza che consente di estrapolare informazioni tridimensionali dalle foto bidimensionali, fino a conseguire il dottorato in Geomatica. Sempre per passione

mi sono specializzato nella progettazione e nello sviluppo di tool per realizzare tour virtuali, video proiezioni interattive e ologrammi, che mi hanno permesso di seguire diverse installazioni museali, in Italia e all’estero. Lo studio dei fattori prospettici e della percezione dello spazio mi hanno aiutato molto nel controllo di camere o di proiettori virtuali, così come nella scelta delle prospettive da fornire all’utente per rendere credibile - o incredibile se tutto va bene - l’esperienza. Non ero programmatore ma lo sono diventato e ora sviluppo applicativi di Spatial Augmented Reality, ovvero la modalità per proiettare la realtà virtuale su oggetti fisici con la tecnica del projection mapping.

Per progredire, di cosa ha necessita la VR dal lato tecnico e tecnologico? Disponiamo già di ottimi visori, tool di modellazione, videoproiettori ecc. ma è indispensabile che la piattaforma sia stabile, e che la rete sia veloce...e ovviamente di un ampio progetto di formazione non solo accademico. Lo sviluppo dei processori grafici ci ha offerto nuove potenzialità per effettuare rendering accurati dal punto di vista fotometrico e ad altissima risoluzione. L’ultimo grande “salto” in avanti è il Real Time Ray-traced Rendering, ovvero l’utilizzo della computer grafica per produrre e analizzare immagini fotorealistiche in tempo reale. Il secondo, a mio parere, è in atto adesso con lo streaming, ovvero la possibilità di condividere la realtà virtuale in tempo reale in uno spazio comune con altri utenti on line, e vivere insieme l’esperienza immersiva di studio, di lavoro, di sviluppo, di creazione e co-creazione. Naturalmente la rete in questo caso è fondamentale, e la disparità tra Paesi Europei, e tra Regioni, si fa sentire escludendo di fatto coloro che non ne beneficiano.

E dal lato cognitivo? In Archeologia e non solo ricreiamo ambienti, cerchiamo cioè di “illudere” gli utenti di vedere un oggetto o di essere in un determinato ambiente, che deve risultare quindi più credibile possibile: ma l’esperienza personale può essere influenzata da molti fattori. Partendo da quelli soggettivi, secondo me non ci concentriamo abbastanza sull’impatto che l’applicativo ha sull’utente, sia dal lato prospettico che dell’illusione. La qualità della relazione con l’utente non dipende solo dalla qualità dell’immagine, ma anche dalla risposta dell’ambiente rispetto all’utente: se ci sono dei delay nella risposta del sensore, se il refresh è basso, l’ambiente VR perde di efficacia e utilità. Ci sono poi gli aspetti culturali e del background di ogni singolo utente: la stessa mostra portata in Germania o a Roma non viene vissuta allo stesso modo: se il visitatore tedesco visita la mostra perché è “utile e doveroso” per incrementare la propria formazione, e ha un approccio molto diretto con la tecnologia fino a testare ogni singolo touch point, quello italiano la visita per ragioni più personali, e di solito è più diffidente rispetto alle tecnologie, tanto che alcuni aspettano altri visitatori per osservare dall’esterno cosa succede con l’immersività.

Come fare un ulteriore passo avanti con la VR? Ci stiamo interrogando molto sullo standard minimo di qualità, anche se è un tema in continua evoluzione: per esempio, quali sono gli step ottimali da compiere per elaborare e ottimizzare i dati Raw per arrivare a un modello fruibile sul Web? Quale frame rate devo adottare? Come deve rispondere il sensore? Sarebbe utile avere degli standard da ancorare all’evoluzione delle tecnologie, perché quello che oggi è qualitativamente ineccepibile, tra due anni sarà sorpassato. Ovviamente non mi riferisco alla qualità estetica, ma a quella necessaria per il lavoro di ricerca.

Il secondo aspetto che ritengo importante è la conservazione dei dati a livello informatico: è indispensabile che non vadano perduti anche con il variare delle tecnologie e degli applicativi… o dei fornitori! Altrimenti rischiamo che due anni di lavoro di renderizzazione del Colosseo, per esempio, non siano più accessibili perché la Software House che ha eseguito il lavoro non esiste più. Infine, ritengo fondamentale lavorare di più sul suono: il nostro sistema cognitivo ne è molto influenzato e un audio immersivo ben fatto aggiungerebbe molto valore e realismo.

di realtà mista docs.microsoft.com/it-it/windows/mixed-reality/discover/mixed-reality www.ispc.cnr.it/it_it/ www.realtimerendering.com

Breve storia della Realtà Virtuale

Anche se già Platone sosteneva nel Timeo, uno dei suoi ultimi Dialoghi, che fuoco, terra, acqua e aria fossero composti da una infinità di minuscoli triangoli capaci di riprodurre qualsiasi mondo possibile, come si fa nella modellazione 3D degli ambienti virtuali, la VR si può dire nasca nel 1962 con il Sensorama di Morton Heilig, un prototipo (completo di cinque film sperimentali) che consentiva di immergere lo spettatore nell’azione coinvolgendo più sensi. Il primo sistema di VR con visore è del 1968 a opera di Ivan Sutherland: enorme e pesantissimo, non a caso fu chiamato La Spada di Damocle. Bisogna arrivare al 1977 con il MIT per vedere un sistema più maneggevole, anche se ancora limitato: Aspen Movie Map, un simulatore che riproduceva la cittadina di Aspen, la modalità di visione chiamata poligonale si basava su una poligonazione tridimensionale. Il termine Virtual Reality risale al 1989: Jaron Lanier fondò la VPL Research, per la creazione di linguaggi di programmazione virtuale mentre Mixed Reality è stato coniato nel 1994 in un documento a cura di Paul Milgram e Fumio Kishino. Infine, il concetto di cyberspazio è stato inventato dallo scrittore di fantascienza William Gibson.

A brief history of Virtual Reality

Even if Plato already claimed in the Timaeus, one of his later Dialogues, that fire, earth, water and air were composed of an infinity of tiny triangles capable of reproducing any possible world, as is done in the 3D modelling of virtual environments, with VR it can be said that it was born in 1962 with Morton Heilig’s Sensorama, a prototype (complete with five experimental films) that allowed the viewer to be immersed in the action by involving multiple senses. The first VR system with a viewer is from 1968 by Ivan Sutherland: huge and very heavy, it is no coincidence that it was called The Sword of Damocles. It is necessary to arrive at 1977 with MIT to see a more manageable system, even if still limited: Aspen Movie Map, a simulator that reproduced the town of Aspen, the viewing mode called polygonal was based on a three-dimensional polygon. The term Virtual Reality dates back to 1989: Jaron Lanier founded VPL Research, for the creation of virtual programming languages while Mixed Reality was coined in 1994 in a document edited by Paul Milgram and Fumio Kishino. Finally, the concept of cyberspace was invented by science fiction writer William Gibson. Suggestioni dalla letteratura e dal cinema

Sia la letteratura che il cinema, in particolare il filone detto cyberpunk, hanno fatto propri gli scenari di realtà virtuale: il primo romanzo sul tema è forse Duellomacchina (The Dueling Machine) di Ben Bova del 1963, dove due avversari possono duellare fino alla morte in un ambiente virtuale senza reali conseguenze fisiche, seguito da Neuromante di William Gibson, considerato il manifesto del cyberpunk. Tron di Steven Lisberger è il primo film di Hollywood (1982) a trattare temi legati alla VR, seguito da Il tagliaerbe di Brett Leonard (1992), ispirato a Jaron Lanier, e dal celeberrimo Matrix del 1999, dei fratelli Wachowski. Da non dimenticare anche l’italiano Nirvana di Gabriele Salvatores e il più recente Avatar di James Cameron, vero e proprio manifesto del cinema 3D immersivo sui temi della realtà Virtuale.

Suggestions from literature and cinema

Both literature and cinema, in particular the trend known as cyberpunk, have made virtual reality scenarios their own: the first novel on the subject is perhaps Ben Bova’s Duellomacchina (The Dueling Machine) from 1963, where two opponents can duel to the death. in a virtual environment with no real physical consequences, followed by William Gibson’s Neuromancer, considered the manifesto of cyberpunk. Steven Lisberger’s Tron is the first Hollywood film (1982) to deal with VR issues, followed by Brett Leonard’s The Cutter (1992), inspired by Jaron Lanier, and the famous 1999 Matrix, by the Wachowski brothers. Not to be forgotten is Gabriele Salvatores’ Italian Nirvana and the most recent Avatar, a true manifesto of immersive 3D cinema on the themes of Virtual Reality.

ACTIVE SPACES VIRTUAL

Immagini dalla serie di eventi proposti da Connessioni con What We Are sui temi dell’AV nella formazione, come risposta alle restrizioni imposte dalla pandemia. Un sentito ringraziamento agli sponsor che hanno reso possibile questo esperimento: Euromet, Lightware, Prase Media Technologies e Yamaha. Images from the events proposed by Connections with What We Are about AV in education as a response to the restrictions imposed by the pandemic. Many thanks to the sponsors who made this experiment possible: Euromet, Lightware, Prase Media Technologies and Yamaha.

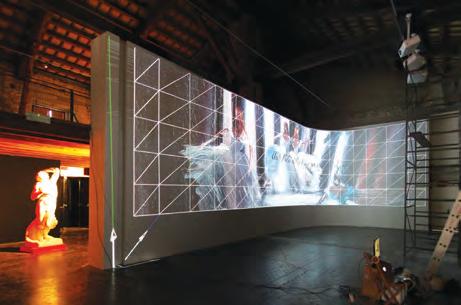

Museo Vigna Barberini Prototipazione e ottimizzazione software per la creazione delle multi proiezioni immersive e per il controllo interattivo, laboratorio di ricerca VHLab - CNR ISPC

Prototyping and software optimisation for the creation of immersive multi-projection and interactive control, VHLab research laboratory - CNR ISPC

Cenerentola - Projection mapping setup della Sala del ballo del museo “La Rocca delle Fiabe” presso S.Agata Feltria - Touchwindow Projection mapping setup of the Ballroom in the “La Rocca delle Fiabe” museum at S.Agata Feltria - Touchwindow

Museo Vigna Barberini Setup e calibrazione di una multi videoproiezione immersiva per una installazione museale temporanea sul Colle Palatino a Roma - CNR ISPC Setup and calibration of a multi immersive video projection for the temporary museum installation on the Colle Palatino in Rome - CNR ISPC

HUMAN

Human computer interaction

MIXED REALITY Conventional reality

COMPUTER

Perception ENVIRONMENT

Small reflection on virtual reality

Without forgetting AR and XR

Chiara Benedettini

When we talk about VR we first think of technologies and programming languages, but cognitive aspects and their evolution over time must also be taken into consideration. Here are some considerations and an interview with Enzo d'Annibale, VR expert and CNR collaborator, to deepen the applications, development possibilities, and perceptual and psychological implications of VR / AR / XR

Between 2020 and 2021 there has been a lot of talk about Virtual Reality (VR) and from many different points of view. Gradually, it was the hypothesis of a different space…where to get together to work (or even just to meet) when it was possible to do so in person, which environment to organise a fair, or the context in which some companies presented new products and applications. For example, see the case of Sony which launched Spark between April and May 2021, an immersive environment that reproduced the ISE stand, to be explored with a first-person view and in which to enjoy presentations, contents, tutorials, etc. In the spring of 2020, we too ventured into VR by launching Active Virtual Spaces, an immersive environment with training and networking purposes to be experienced with an avatar, where we could carry out the events we had planned and which, like everyone, we could not carry out in person, an alternative to Webinars that only partially meet the need for relationships between the participants. Virtual Reality was also a suggestion and a desire for many during the lockdowns, a parallel environment in which to live what Covid has denied us for many months, from a walk to meeting friends, to the possibility of taking a trip.

The fact is that, although we think of VR as an opportunity even after Covid, with a view to drawing the best synthesis between what the pandemic has taught us and the rediscovered ‘normality’, still many do not consider it ready for the big leap. However, the cause appears more related to cognitive reasons (how we live and perceive the experience of the outside world through the senses and our own wealth of knowledge), rather than to technological reasons. So the technology could be ready, but are we not yet able to use it to the fullest? Is it therefore necessary to shift the point of view?

BRIEF VADEMECUM OF VR / AR / XR CONCEPTS

We are sure that our readers already know what we are talking about quite well, however focusing on the words often leads to surprises. In fact, perhaps few know that VR is not a recent concept: without wishing to bother Plato who in one of his later dialogues, Timaeus, hypothesised that reality was built from tiny triangles that sewn together can reproduce any reality, it was Morton Heilig in 1962 that created a sort of experiential cinema with Sensorama. The term VR dates back to 1989, when Jaron Lanier founded VPL Research with the aim of creating virtual programming languages. Today the term has expanded a lot and does not refer only to an immersive experience, but in general to the virtual simulation created with a computer, also enjoyed through a normal screen that acts as a ‘window’ with VR. Returning to the words, with Virtual Reality we mean the creation or simulation of a real environment or situation through a computer and possibly interfaces that act as an extension of the body. So, VR is lived in first person! Augmented Reality, on the other hand, is an extension or integration of reality with images created virtually, which modify the original environment without affecting the possibility of interaction of the subject in reality. Finally, Mixed Reality is more than the sum of both: it means the fusion between the physical world and the real one thanks to tools such as 3D graphics, artificial vision, data processing and content in general. The term was clarified in 1994*, and over time the relationship between human input and that of the computer has been deepened; but it is the combination of computer processing, human input and environmental input that gives life to mixed reality experiences. As you can see, the body, personal experience and perception (also given from the unique and unrepeatable point of view of each of us) continue to play a fundamental role in Virtual Reality as well.

IMMERSIVITY AND COGNITIVE EXPERIENCE IN VR

The presence and immersion in the environment, as you can see, are the cornerstones of Virtual Reality. By ‘presence’ we can mean the level of psychological realism that a someone experiences in interacting with the virtual world, in the instantaneous relationship with the environment and in a manner consistent with expectations and forecasts. For example, letting go of an object, it is expected to fall to the ground and not float in the air. From a psychological point of view, immersion is achieved with the involvement and use of the subject’s cognitive resources. Taking the example of the body dropped, immersion is given not only by the tactile sensation of the object slipping away from

* The term mixed reality was coined in 1994 in a paper by Paul Milgram and Fumio Kishino: (A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual Displays.)

Progettazione e simulazione 3D di infrastrutture per spazi di proiezione immersiva nei musei - Ing. Enzo d’Annibaleibale

Cenerentola - Video proiezione immersiva con contenuti in Spatial Augmented Reality per la Sala del ballo del museo “La Rocca delle Fiabe” presso S.Agata Feltia - Touchwindow

Spadò - Multi videoproiezione su ampia superfice curva - Esposizione del titolo “Spadò – L’artista eclettico che incantò l’Europa” presso la Mole Vanvitelliana di Ancona per Touchwindow the hand, by the sound produced upon impact with the ground and by the visual consequences of the action, but also (for example) from the activation of the automatic processes linked to the attempt to recover it before it hits the ground and is damaged. However, even if the experience of VR affects all the senses, from hearing to smell, sight is the one most prevalent in humans, so that many of the devices and applications for VR focus on sight. In fact, there are already several viewers on the market, such as 3D modelling tools have reached levels of great detail, thanks also to the arrival of 4K and now 8K, while very few have ‘wired gloves.’

The technologies used in VR are: • 3D modelling software and tools, starting both from real material (photos and videos, so to speak), and synthetically produced (data and coordinates of objects and places, for example). One of the most used languages for creating virtual worlds is VRML (Virtual Reality Modeling Language.) • Viewers; the best known are Oculus, Samsung HMD Odissey, or Microsoft’s Hololens, based on holographic technology; in the gaming sector, Playstation VR; • Earphones, to reproduce spatial sounds; • Wired gloves; gloves equipped with sensors capable of recording movements, but also accelerations, allowing interaction with space and virtual objects; • Cyber-suit; a suit that wraps the body. It can have multiple uses, it can simulate touch by flexing on itself thanks to the elastic fabric, or make a three-dimensional scan of the user’s body and transfer it to the virtual environment. But if it is true that virtual reality potentially has all the credentials to allow us to live powerful, direct, first-person experiences of virtual or mixed reality, and that it promises us, precisely through our cognitive system, of being able to live “accelerated” experiences well, whether it is training, work or entertainment, we have not yet reached the state of an optimal and 100% user friendly experience. In short, we know that more can be achieved. The hypothesis could therefore be that the point to be crossed is not of a technological nature, but lies in cognitive reasons. Until now, VR tools have focused a lot on the visual experience, however we know that the other senses also play a fundamental role in the perception of reality. Indeed, hearing and smell in particular are senses that bring us back to very deep dimensions of our experience, also drawing on the person’s unconscious. And it is often hearing that, even before sight, warns us of dangers, or of something we must pay attention to. Therefore, given that the technology is mature, it could be useful to focus more on perception, starting from hearing and smell. Another avenue, which literature and film have appropriated as a powerful suggestion for compelling stories - see James Cameron’s Avatar films, or Adam Sternberg’s novel Shovel Ready - is the possibility of bypassing the physical aspect of man to directly relate the peripherals with the user’s brain (the so-called Wetware), the true centre of all our perceptions.

THE APPLICATIONS OF TODAY AND TOMORROW

Alongside the enormous possibilities of VR in gaming and entertainment, with the possibility of creating possible, realistic but not necessarily real worlds, in business applications VR is often used to recreate real or otherwise realistic settings, of what is too far away, difficult to reach - physically or materially - or risky. VR is already used successfully in design, also in the direction of preventing inefficiencies, errors, etc. In this sense it is also used in mechanics, to predict weaknesses of the various parts and anticipate or locate failures. The training

already uses VR, not only to recreate study environments, but also to study without risk in the field of medicine, biology, with potential still to be invented. Another field that already benefits from VR is marketing, even if still a niche one: it is not difficult to imagine the advantage of being able to go to the same store several times without taking an hour of travel, of designing one’s own kitchen in an immersive perspective, not to mention the advantages for those who have to present to potential customers homes, boats, environments still on paper but which can live around us thanks to a viewer and two sensors.

VR IN RESEARCH AND TRAINING

To deepen VR in an application straddling the world of education and research, we interviewed Enzo d’Annibale: engineer, postdoctoral fellow at CNR - ISPC (Institute of Cultural Heritage Sciences), but also freelance designer and designer of immersive experiences, part of the WhatWeAre working group specialised in immersive experiences, an Italian but for many years has been based in Sweden. With Enzo, we not only talked about the advantages of virtually recreating the world of 2,000 years ago to be able to study it better, but also about the development of these technologies.

Enzo d’Annibale - I deal with VR applications in the field of archeology. To the virtual 3D reproduction of artifacts or entire sites through a multidisciplinary work, we integrate additional information and often archaeological reconstructions of the past. In practice we simulate what we cannot (anymore) see, but which was real in the past. We develop tools for the use of virtual scenarios not only for specialists, but for a wider audience, in particular that of museums. In the professional field I have often dealt with the design and development of tools for creating immersive video projections or theatrical devices such as holograms, or rather Pepper’s Ghost. To give an example, during my first project for museums in Libya we first virtually reconstructed architecture and sculptures scattered over the vast territory, in deserted and difficult to reach places, then we reproduced the sites inside the Tripoli Museum in the form of holograms or a virtual tour.

Can you tell us more about your work group? ISPC - the Institute of Sciences for Cultural Heritage - deals with the enhancement of cultural heritage using humanistic, scientific and technological applications; I am part of a group that does research in the archaeological field using 3D, virtual technologies and digital storytelling. It is mostly made up of archaeologists - apart from me and a user experience expert - although very far from a chisel archaeology; many are, or have become, skilled modelers and skilled programmers.

Before delving into it, how do you become a VR expert? I did not follow a specific training path, I started using 3D simulation tools during my degree course in Building Engineering Architecture. I cultivated a passion for photogrammetry- the science that allows you to extrapolate three-dimensional information from two-dimensional photos, and progressed through to a doctorate in Geomatics. Always out of passion, I specialised in the design and development of tools for creating virtual tours, interactive video projections and holograms, which allowed me to follow various museum installations, in Italy and abroad. The study of perspective factors and the perception of space helped me a lot in controlling rooms or virtual projectors, as well as in choosing the perspectives to provide to the user to make the experience credible - or incredible if all goes well. I was not a programmer, but I became one and now I develop applications of Spatial Augmented Reality, that is the way to project virtual reality on physical objects with the projection mapping technique. To progress, what does VR need from the technical and technological side? We already have excellent viewers, modelling tools, projectors etc. but it is essential that the platform is stable, and that the network is fast ... and obviously a large training project, not only academic. The development of graphics processors has given us new capabilities for photometrically accurate, ultra-high resolution renderings. The last big “leap” forward is Real Time Ray-traced Rendering, the use of computer graphics to produce and analyse photorealistic images in real time. The second, in my opinion, is now underway with streaming- the possibility of sharing virtual reality in real time in a common space with other users online, and living together the immersive experience of study, work, development, creation and co-creation. Naturally the network in this case is fundamental, and the disparity between European countries, and between regions, is felt by effectively excluding those who do not benefit from it. And on the cognitive side? In Archeology we recreate environments, that is, we try to ‘deceive’ users to see an object or to be in a certain environment, which must therefore be as credible as possible: but personal experience can be influenced by many factors. Starting from the subjective ones, in my opinion we do not focus enough on the impact that the application has on the user, both from the perspective and from the illusion side.

The quality of the relationship with the user does not depend only on the quality of the image, but also on the response of the environment to the user: if there are delays in the response of the sensor, if the refresh is low, the VR environment loses effectiveness and usefulness. Then there are the cultural aspects and the background of each individual user: the same exhibition brought to Germany or Rome is not experienced in the same way: if the German visitor visits the exhibition because it is ‘useful and necessary’ to increase their training, and has a very direct approach with technology up to testing every single touch point, the Italian one visits it for more personal reasons, and is usually more suspicious of technologies, so much so that some wait for other visitors to observe from the outside what happens with the immersion.

How can we take VR a step further? We’re asking ourselves a lot about the minimum quality standard, even if it is a constantly evolving theme: for example, what are the optimal steps to take to process and optimize raw data to arrive at a model that would be usable on the Web? What frame rate should I adopt? How should the sensor respond? It would be useful to have standards to be anchored to the evolution of technologies, because what today is qualitatively impeccable, will be surpassed in two years. Obviously I am not referring to the aesthetic quality, but to that necessary for the research work. The second aspect which is important is the conservation of data at the computer level: it is essential that they are not lost even with the variation of technologies and applications ... or suppliers! Otherwise we risk that two years of rendering work on the Colosseum, for example, will no longer be accessible because the Software House that performed the work no longer exists. Finally, I believe it is essential to work more on sound: our cognitive system is very influenced by it and a well-made immersive audio would add a lot of value and realism.

La pubblicazione di riferimento per il mondo degli SMART BUILDING

N° 7 I 2021

DIGITALIZZAZIONE E RIVOLUZIONE VERDE: I GRANDI TEMI DELLA RIPARTENZA

SBI NETWORK la cabina di regia

FOCUS PROFESSIONI Case sempre più connesse per vivere bene anzi meglio!

EFFICIENZA ENERGETICA

SMART CITY I progetti più innovativi per la smart city

TECNOLOGIA E MERCATO 6 I 2020

IL FUTURO È UNA LEARNING CITY

Carnevale Maffè

L’INTELLIGENZA ARTIFICIALE PER LA DIAGNOSI E LA CURA

Claudio Ronco

SMART WORKING, UN BOOM CHE GENERA MERCATO

Fiorella Crespi e Luciano Vescovi

I MUSEI DEL POST COVID INVESTONO IN SICUREZZA E CREATIVITÀ

Solima, Maffei, Manoli, Hruby

smartbuildingitalia.it

LE TECNOLOGIE DOPO IL LOCKDOWN

5 I 2019

DONATELLA PROTO: LE NORME NON BASTANO, LA SFIDA DELL’EDILIZIA 4.0 NON È ANCORA VINTA

L’INTERVISTA INEDITA A MARCO GAY: STARTUP E GRANDI IMPRESE L’ALLEANZA VINCENTE

GRAHAM MARTIN: REALIZZARE IN MODO INTELLIGENTE EDIFICI INTELLIGENTI

smartbuildingitalia.it

MILANO SMART CITY CONFERENCE

4 I 2019

SMART CITY CONFERENCE

PENTASTUDIO E COMOLI FERRARI INSIEME ANCORA PIÙ SMART

UN ROADSHOW DI EOLO LANCIA GLI IMPIANTI MULTISERVIZIO

L’IMPORTANZA DELLA FORMAZIONE

ROTTA SU MILANO: GLI EVENTI SMART BUILDING 2019 SMART INSTALLER

1

SMART ® BUILDING ITALIA

IL MAGAZINE DELL’EDIFICIO INTELLIGENTE

IN FIERA A BARI

Integrazione, innovazione e formazione per i professionisti della fliera

FIBRA OTTICA, BIM E 5G

Nuovi strumenti per il rilancio del settore delle costruzioni

LA MAPPA DEGLI ESPOSITORI

smartbuildingitalia.it

smartbuildingitalia.it

SPECIALE SMART BUILDING LEVANTE 2018

Il magazine dell’edificio intelligente è una iniziativa di Pentastudio penta@pentastudio.it www.pentastudio.it

Richiedi la copia dell’ultimo numero a info@smartbuildingitalia.it Sfoglia la versione digitale www.smartbuildingitalia.it