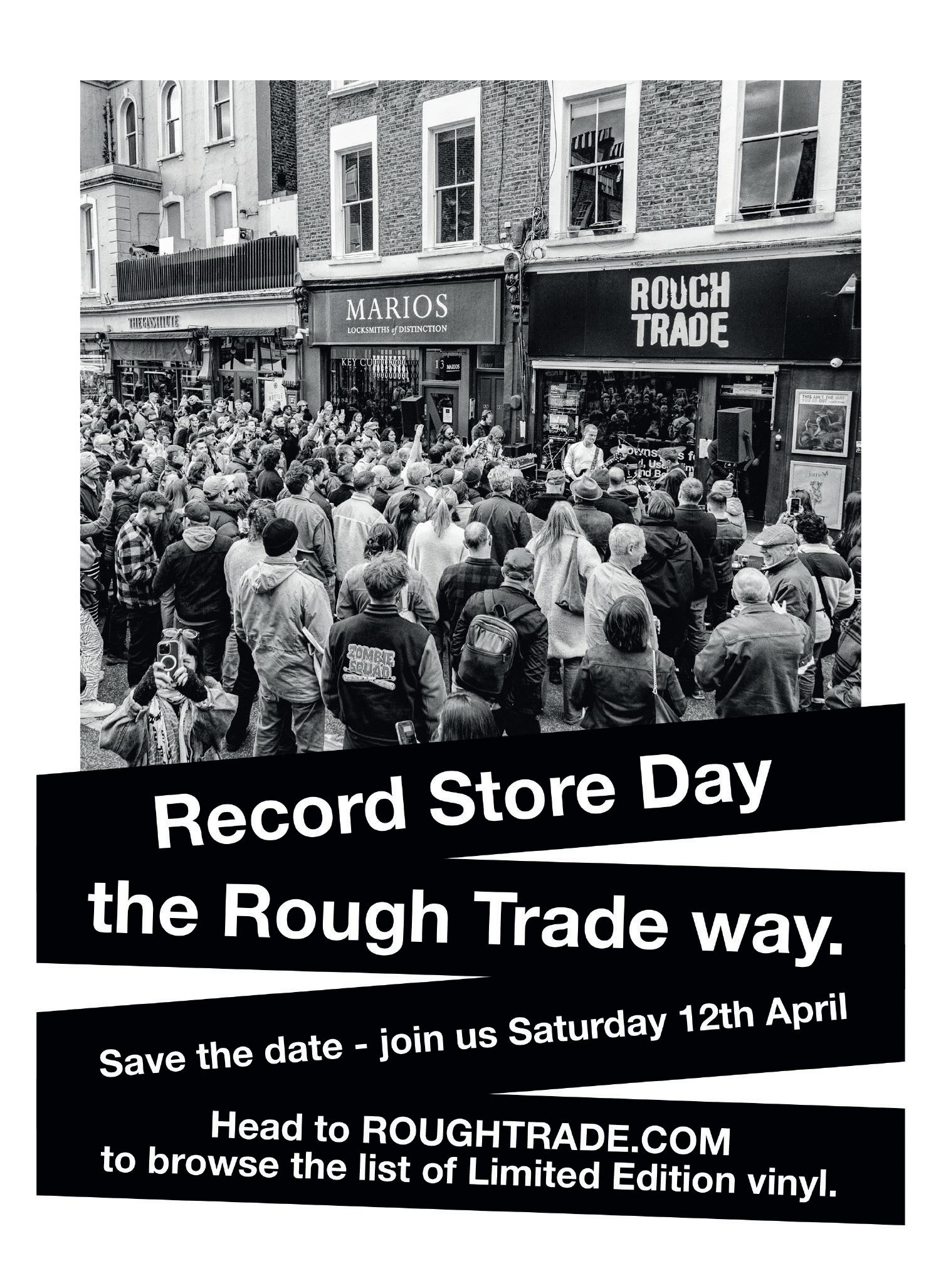

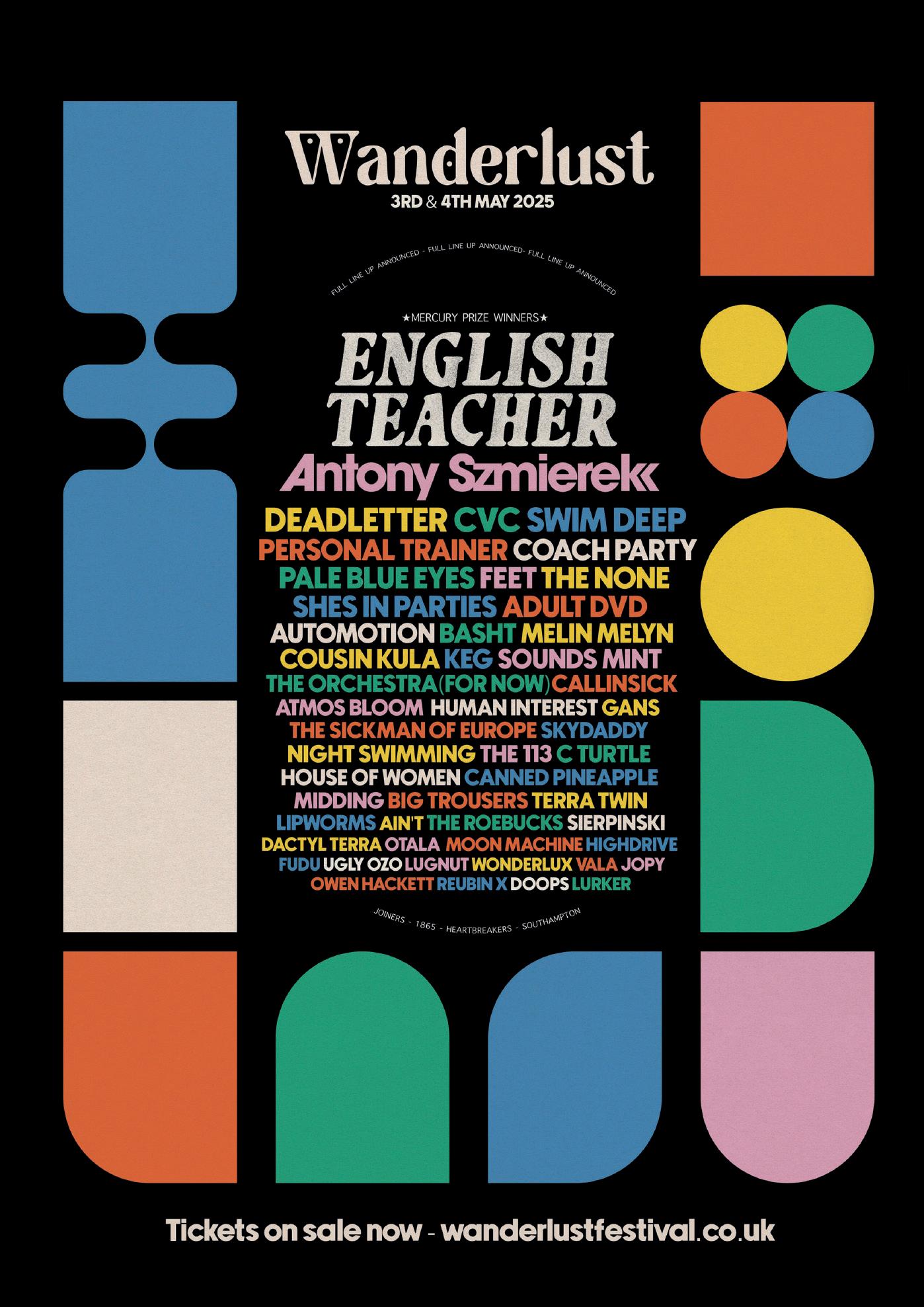

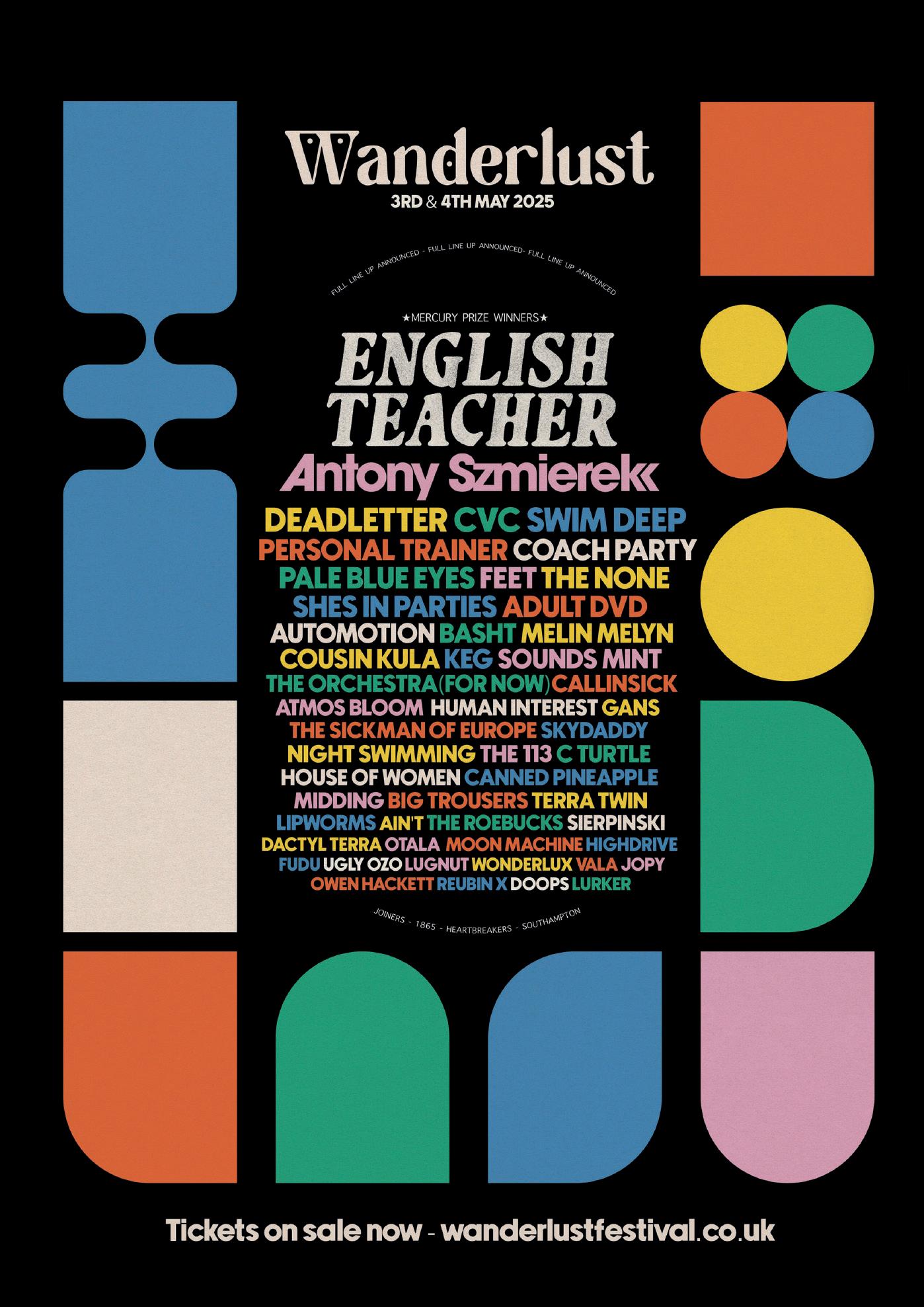

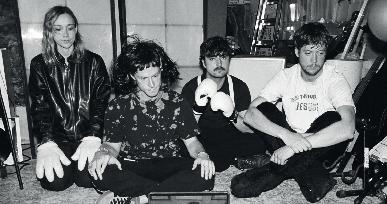

One band with a new record and a particularly interesting new dynamic are Black Country, New Road. With their third studio album ‘Forever Howlong’ announced and single ‘Besties’ signalling the future sound of the group, we call to discuss their relationships with each other, retaining humour in their songs and only making music that represents the current version of themselves. Black Country, New Road are on the cover.

Having recently made the move from the active DIY scene in Chicago to the hustle and noise of NYC, you’d be forgiven to assume that new music from Horsegirl may mirror the hecticness of their new city, however the opposite is true. On new album, ‘Phonetics On and On’, the three piece cherish the space in their music and find new freedom via the guidance of Cate Le Bon and the evergrowing confidence in their relationship as a band. We chat on all of the above inside.

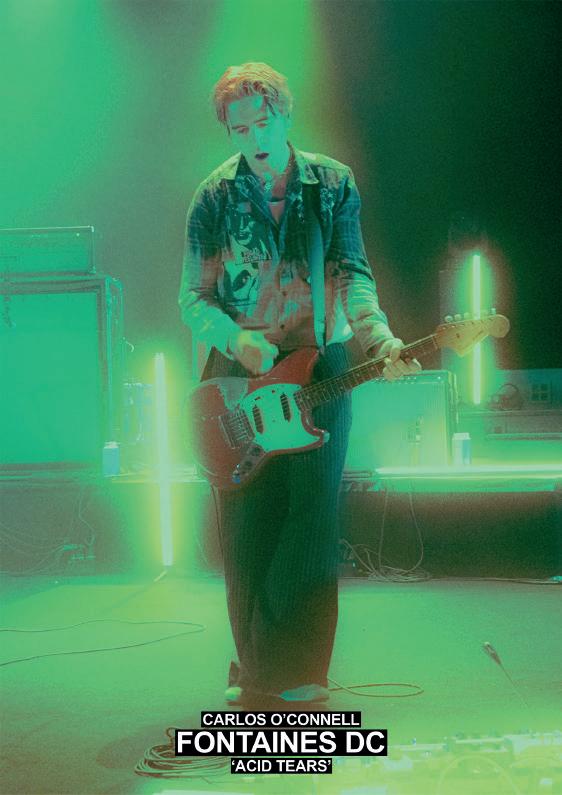

The Murder Capital are preparing for the release of their third album ‘Blindness’. It’s their first record without any bruising from the pandemic and the surrounding measures, yet its with this record they find themselves indiviudally split across countries whilst more intact with a singular view of their music than ever. Discussing the music, the necessity of continuing to ‘work’, and the understanding of modern day patriotism, we interview frontman James McGovern inside.

More records discussed inside include ‘Evenfall’, the debut album from South London’s Sam Akpro, and ‘Debunker’, the second album from London-viaBarcelona’s Eterna. The former details the patchwork of influences and locations that built the record, while for Eterna’s Guillem Peeters the process was a more isolated affair.

Squamish, British Columbia is home to new band Cistern whose EP ‘New Standard’ was released in November 2024. With single ‘Crisis’ on repeat and a debut album being worked on, we thought it a great time to learn a little more about the projects beginnings. They take our call while walking the streets of Squamish. Another recently released debut EP is ‘Four Potraits of the Same Ugly House’ from Cork’s Pebbledash. Following a practice and ahead of their trip to London for our We Are So Young night, we gave them a call to discuss their sound and their development away from 6 minute epics.

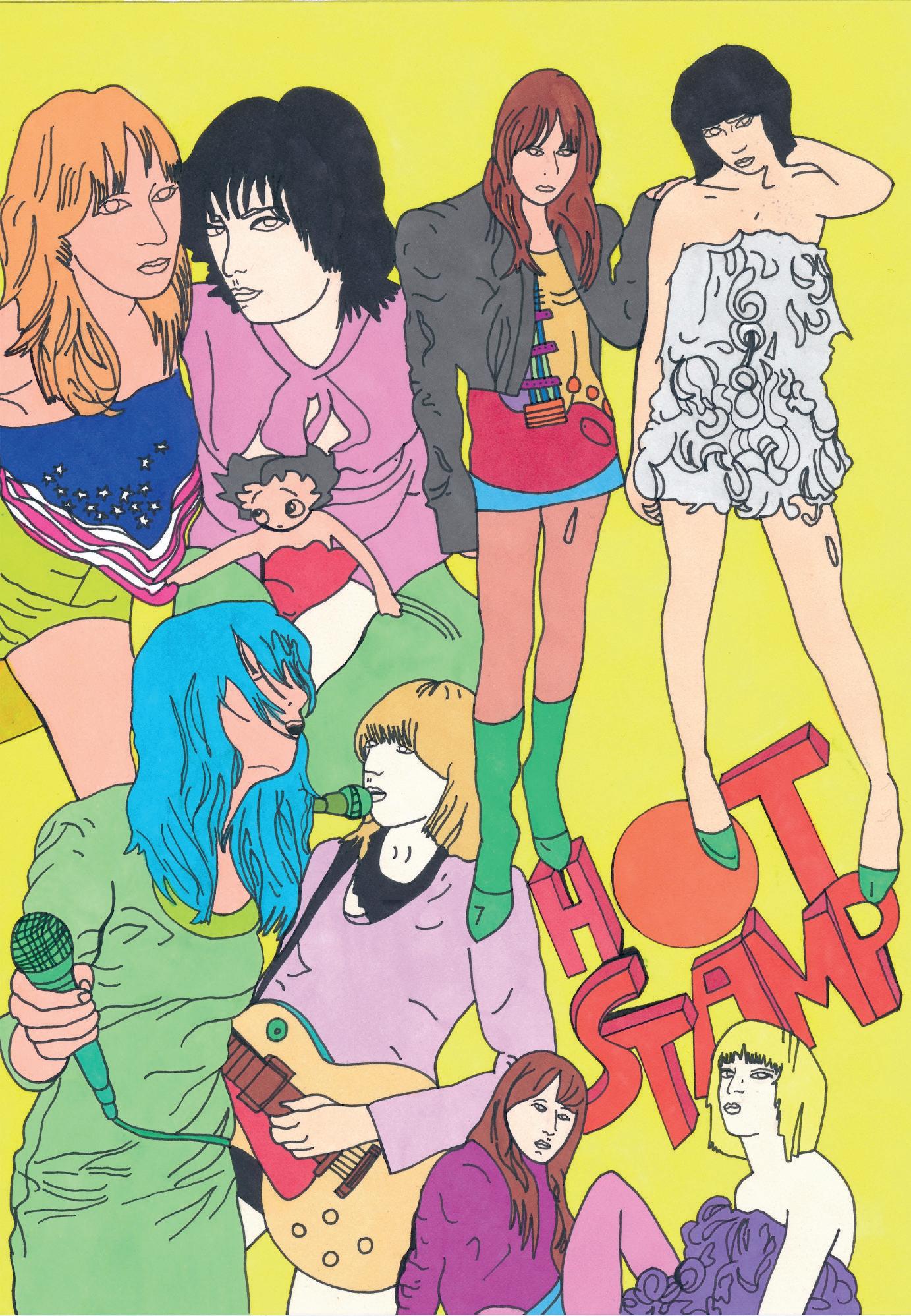

Rounding up our artist features are conversations in the capital with Hot Stamp and Green Star, plus a trip to Stockholm for a chat with young new favourites, Clutter.

We chat with Jordan Kee, the incredible artist behind the visuals for Black Country, New Road’s current album campaign. We also speak with exciting Welsh artist, Caitlin Flood-Molyneux as well as Morgan Sidle, the creative behind DIY fashion brand, Atelier.

Having existed in their current form for less than a year, London-based trio green star have already released two captivating singles and are now on the cusp of releasing their debut EP. With influences such as Sonic Youth and Autolux, green star move freely within the grittier end of shoegaze and grungy noise pop. Splitting the vocal and writing duties three ways, the project is a meeting of like-minded creatives, each melding their input with their respective disciplines, spanning from music production to visual arts and dance.

Immersed in an abundant creative community, green star played their first live set in the warehouse where two of the members live, keeping things charmingly close to home yet distinctly ambitious. In the middle of recording their debut—and almost a year to the day since this inaugural gig—the trio met me in an East London pub to talk me through their first year.

So, how did you guys meet?

Pedro: Alberto and I were at uni together studying graphic design and we were both looking to start a project. We both had other bands, but nothing too tied to what we wanted to do. We connected on a lot of references so we started jamming together and we had such great chemistry—it was super easy. After some time, we needed a new bassist, and we found Lilah…

Lilah: On the website joinmyband.com, I put something up months before anyone contacted me because you have to pay to talk to someone. I had actually forgotten about my profile—I don’t even know what I put on there!

Alberto: Lilah had the exact same reference as us, and to be honest, it was mostly 50 year old men on that website.

I can’t say I’ve ever heard of joinmyband.com! I can imagine it’s a niche crowd.

P: It’s a rarity to find someone who’s aligned with what you want to do. I saw her and was like Alberto, we need to find a way to contact her.

A: I got her Instagram in like 30 seconds.

P: The internet is weird!

L: Yeah, but you messaged, I responded, I went to your flat–everything’s good!

Lilah, had you been in bands before?

L: No prior band experience! I’m a dancer, so I’ve been training my whole life. I’m at dance uni at the minute, and it’s crazy. I really wanted to be more involved in music, but it’s hard to find people looking for members. Then it just happened. I was like, “amazing!”

And you moved to the UK to study dance! At your uni, do people talk about or play music in the way you were looking for?

L: Not necessarily the student body, it’s more just dance oriented, but we do have live musicians for classes which is incredible. They’re all a bit older though and they don’t want to do projects with me…

Oh wow! Is it all classical?

L: It’s actually quite experimental! We get guitarists with their pedal boards and crazy drummers and stuff. It’s rare that it’s just a pianist for a ballet class.

That’s really cool! Has that fed into how or what you play?

L: Oh, for sure. Everything is so interlinked, even the way I move around on stage. People have commented on it before, like, “you’re moving and grooving!”

P: We ask her for directions.

A: Lilah did actually choreograph our video for ‘replication’.

That video is beautiful! I feel like it looks exactly how it sounds.

P: Thank you! The music video was shot by one of my closest friends, Rodrigo Morán, he’s a Spanish director. I admire him so much. He has this crazy mind and he understands a lot about what we like and what we don’t.

You have quite a concise visual identity, how does that play into what you do?

P: I’ve been doing creative direction, shooting, and graphics for bands for about five years, so I’m very close to the role visuals play in musical creation. You’re making the roots of the world that you want the music to live in. I think visuals—the videos, how we present ourselves—it’s all part of the world we want to create. Luckily, we are very aligned in what we like, so it was very easy to make decisions in that sense.

Do you have other creatives around you that you can bring in? It can be so different for a new band when they have creative people around them to bounce off of.

P: Yeah! I feel like that’s something I’ve always defended. Having this band is also a great platform to bring in our creative friends. It’s such an important thing to us to build up a community and use whatever platform we create to collaborate with people. Music is the core of everything we do in green star, but there are so many little branches that you can play around with. I had this great conversation with Cole from C Turtle about this: London can feel quite solitary, and it’s difficult to make deep connections. You’ll put a lot of effort into things that sometimes don’t happen—it’s a bit miserable at times! There is a warmth that comes with creating something with people we like and admire.

Of course, how have you found doing your first shows?

A: Our first gig was almost exactly one year ago to the day! We did it in our warehouse, actually. It was really great; a lot of people came in. I remember playing the first song, playing the chords, and seeing it for the first time— it was really exciting.

P: Obviously, it was also our space, so it felt like such a beautiful place to start the birth of our project. The past year, we’ve been gigging so much—almost too much. Now we’re in a position where we just want to sit back and get new things done.

I get that—you’re at that point where you can play the shows you want to play. And Lilah, had you ever played live? How did you find it?

L: No, I hadn’t. I was pretty terrified, but also, I’ve been a performer my whole life. I know that I have a very good memory, and I guess playing is kind of physical, so I was like, “This is dance, I am dancing!” It happened, and I survived. Sometimes you just need to not think about things too much. It was just going to happen, and now I don’t feel like that anymore.

That’s so interesting! To focus on the movements. When it comes to recording too, do you record separately or are you recording live?

A: We are actually in the middle of recording our first EP right now. We’ve recorded five of the songs with separate tracks but one of the songs was recorded live.

And Alberto, you’re producing the EP, what was the reason for recording that one live?

A: That song actually came as an intro for another song, it was like a transition and then we decided to make a song out of it with Lilah on vocals. I think because we wrote that song whilst jamming it just felt right.

P: Also, in our music, the noise is such an important factor. There are certain songs we write where we have to embrace the errors in many ways, and this song is super noisy so it was the only way to naturally bring in those errors.

A: Our way of writing is to produce at the same time. Some bands make everything and then go into the studio but we make the song at the same time we produce, that’s the way we work best.

I guess because you’re the producer as well you have that freedom.

P: That’s real. We don’t have a deadline.

A: Well, we have deadlines! But we don’t have to pay for it.

Would you like to keep producing?

A: Yeah! I love producing it. The same way Pedro’s picky with the visuals, I’m picky with the production. But when we have more resources, I would also love to co-produce and work with more people. We’re very open to that.

P: It is quite easy for us, in a sense, that we rehearse, record, and live in the same place! There have been times when we’ve been jamming or rehearsing, and we’re like, “This is really cool—let’s go do a quick demo.” We’re in a position where we can do that without going to a studio or bringing in someone else! We’re very lucky.

That’s great! When can we expect to hear the EP?

A: It should be out in Spring. We literally came here from the studio! We played the last chord and then jumped on the bus here. We’re finishing it up right now.

Exciting! What would you like people to take away from it?

P: Personally, as our debut EP, the most important thing is that it defines our world. We want to present ourselves and bring our world to life. Conceptually, I feel like all the songs are part of the same sound and tone.

A: There is a lot of lyrical romance with a lot of noise and chaos. It’s a mixture. I’d say this EP is like a recap of this year. These are the songs we’ve been playing live; we really like them, but we also want to move on to new things. So, we can recap this first period of the band, present it, and then start working on new stuff!

L: I agree, it’s about setting the tone, the space and atmosphere of this world we’ve created…

P: …that we are creating!

What are your plans so far for the rest of this year?

P: Make music! We just want to experiment. We want to bring the band to other spectrums in a way.

@clemencemira_

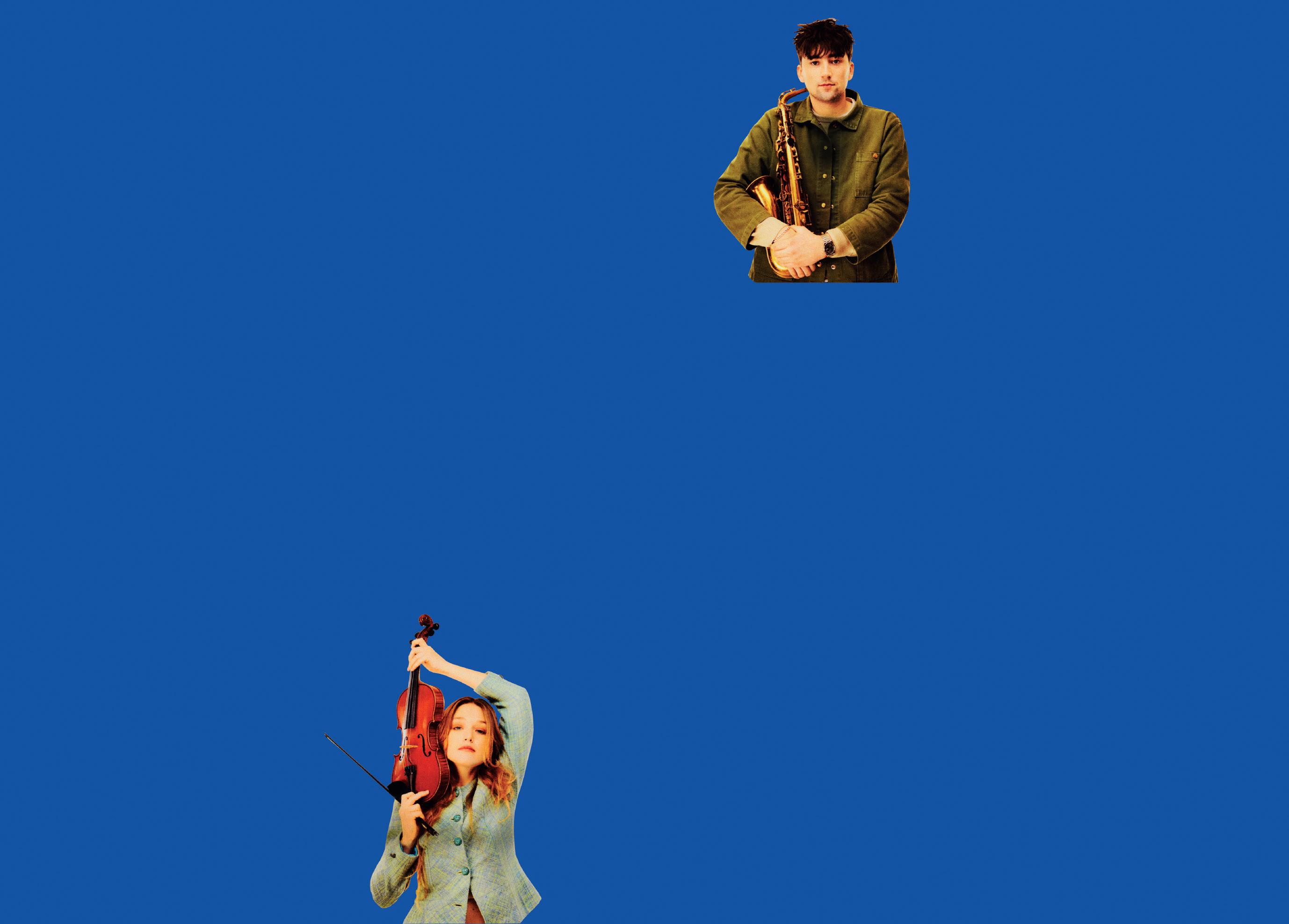

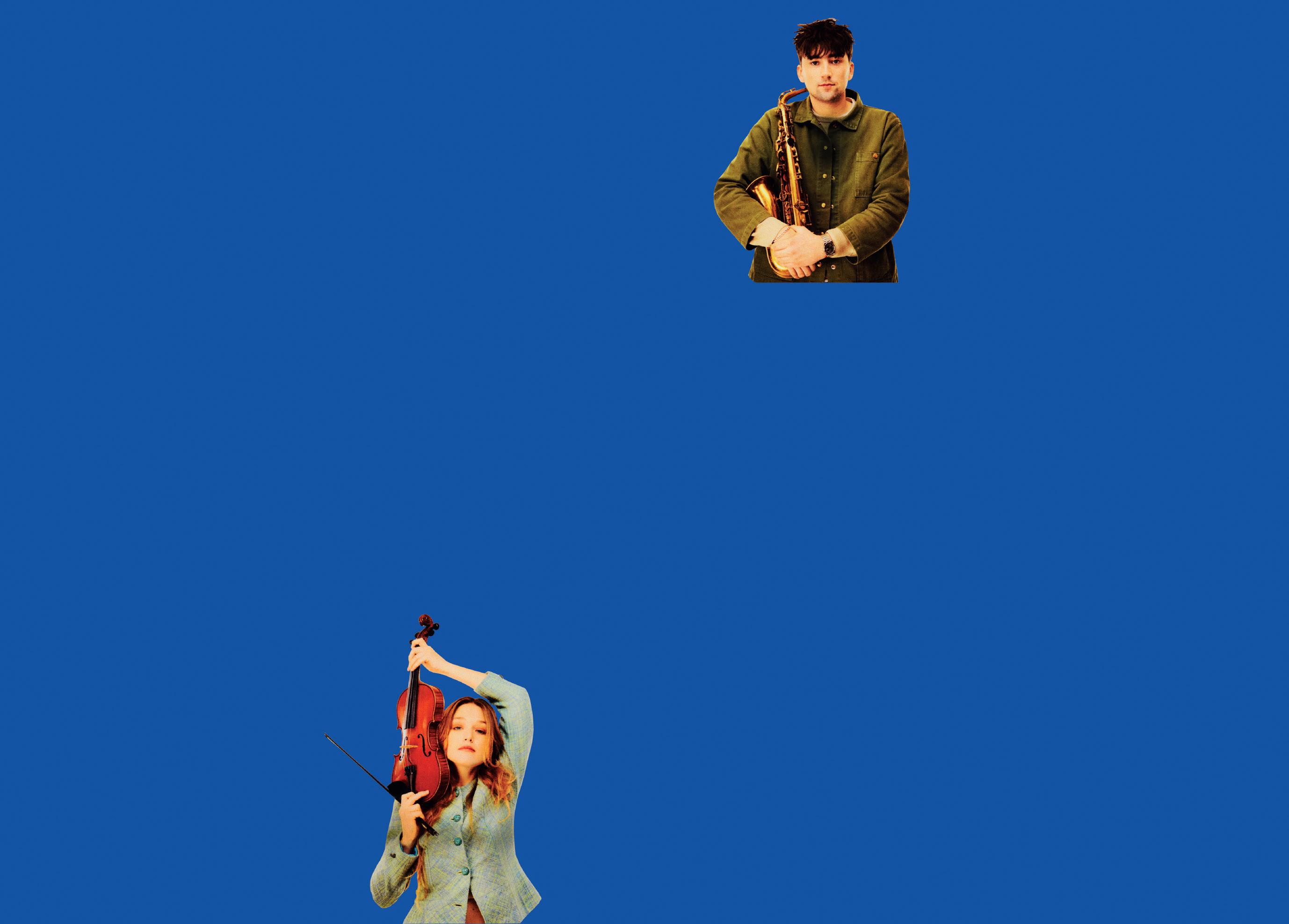

Horsegirl once sculpted their world from thick layers of distortion, filling every inch of silence with a youthful urgency. But on their sophomore album ‘Phonetics On and On’, Penelope Lowenstein, Nora Cheng, and Gigi Reece turn toward a sound that stretches and breathes, trading that heavy saturation for something brighter, more pastoral, and unexpectedly vulnerable.

The distance between their heroes and themselves is shrinking. They’ve grown from playing Sonic Youth covers in Chicago basements to working with Steve Shelley and Lee Ranaldo on ‘Versions of Modern Performance’ and then touring with The Breeders. Now, under the guidance of Cate Le Bon, they let the light in— embracing delicate textures, unexpected instrumentation, and the beauty of imperfection. This time, curiosity leads the way, making ‘Phonetics On and On’ feel ever so much more intimate.

Between juggling school lectures and the whirlwind of pre-album press, I spoke with Penelope about how their songwriting has deepened, and the freedom that comes with letting go.

Sorry to nerd out about basses for a wee bit, but I’ve always been fascinated by the Bass VI. How much does it influence what you play?

I think it’s a bigger part than what I give it credit for.

I don’t think what I write would translate well onto a standard bass. I really love to use that higher voicing on the VI, which is a completely different sound.

What initially drew you to it?

When we started, I was solely a guitarist, but we realised we needed a bass. I thought there was no way I was gonna become a bassist, but I started playing a friend’s VI and really loved it. I do think I approach it like a guitar in a lot of ways. The way Nora and I approach our parts, even the drums, we really talk about how they interact with each other. Being a trio allows me to play more melodic bass parts without things feeling too busy.

As a trio, how do you find you build up that empty space?

Space is a huge topic of conversation for us. On the first record, noise and how much space we could fill was the most exciting thing. When we started writing again, we found a natural emptiness to three people. Those moments when something stops are actually so interesting; things shine. That’s part of what makes the vocals feel so vulnerable. There’s this really beautiful interplay between the three instruments that leaves this super vulnerable emptiness, where a more emotional song can really come forward in a way that it can’t when you’re trying to blow everyone’s ears out.

And working with Cate Le Bon, that was almost like having a fourth member for you. How did opening your work up to someone else feel?

From the start, we’ve always made our own album artwork and our own videos. Letting go of anything has always been the hardest thing. The idea of having someone hear our parts and say, “You should do it like this,” we were really nervous about what that would look like.

We knew if there was anyone we were gonna let into that process, it was Cate. Her direction and tone of voice were more artist to artist than producer to artist. Yeah, she became this mentor figure for us.

How did getting in contact with Cate come about?

We actually wanted to work with her for a really, really long time, but we never thought she would; I guess we thought she was above our level. We had demoed out the early versions, like really early ideas, clean guitar tones, experimentation with percussion, etc. We sent it to Matador, and they responded thinking Cate would be a really awesome fit. As soon as we knew she was an option, we never spoke to anybody else. It was a dream.

That’s really sweet! I really do love how much more you’ve added in terms of experimenting. How much of that had you decided before going into the studio?

We knew we wanted to push ourselves in a new direction, which is part of why we asked Cate to produce it. We knew we would never choose someone like her to just hit record. We wanted someone who would have a dialogue with us and really push us in new directions. We did come to the studio with finished songs, but we didn’t know to what extent they would grow until we were there.

You mentioned the vulnerability these vocals held on this album; they do feel very different from your first record. How did you approach writing these lyrics?

That was one of the biggest changes. I wrote a lot of the lyrics on this record, and I think that was a really natural progression. I felt a new way of connecting with music moving to New York and just getting older. I don’t think I was old enough to have tapped into any sort of genuine love songs when I was 17. Once I wrote my first song with genuine personal lyrics, I felt so connected to it that I became almost addicted to it.

I feel much more connected to these songs because the lyrics remind me of my own life, realising that for myself is something that will change my songwriting.

What was that moment for you that changed that?

‘Julie’ to me was just like a moment that really changed how I write. That, and ‘Front Runner’ is a song that Nora and I wrote together here in our apartment in a really sweet way. Both of those really stand out to me.

Another thing I love is how much fun you seem to have with all your music videos.

I think we’re still finding ourselves in our place a little bit. As teenagers, there’d be an element of putting yourself in a video, feeling very out of control of your image, not knowing who you were presenting. Now we feel more grown; we can do something fun, feel more confident, and give real opinions about the aesthetics. We’ve always been super controlling of all the visuals, but I’ve found the process of making them and expressing the band much more fun this album cycle.

How many takes did ‘2468’ take?

You know, actually, so few, as it was shot on film. Where I feel like I’m messing up, that’s sort of the spirit of the whole thing. Embracing the awkwardness and realising that that is part of our dynamic and owning that. So I’m happy with the one take ‘2468’.

That’s crazy; I thought it must have taken so long to get right. You all met as teenagers, and you’ve grown up together through this band. Looking back, how has being in Horsegirl shaped your lives?

Oh my god, completely. I doubt I’d be living here if the band hadn’t happened. I probably would be going to liberal arts school in the middle of nowhere.

They moved here before I did, so I thought I might as well go live in the same city as them, so I feel like we’re kind of committed to this friendship and career together that has already changed my life. All the friends I’ve met here have been through them, and our lives are just incredibly integrated. My family thinks of them as their kids basically.

How’d you compare Chicago and New York?

There’s just no DIY spaces here. Someone recently said to me that a DIY space hasn’t been able to stay open in New York for more than a couple months. Everything is busy; there are so many people here. It’s almost kind of hard to find your place. New York is just really expensive, so that in itself makes it challenging for art scenes.

As well as its DIY movement, Chicago’s a place with so much political history. Can I ask a little bit about how you’re feeling about the current state of the US politically?

Yeah, I’m terrified. For a long time, things have been very scary in this country, and for many people. But recently, it has been feeling pretty existential. I kind of don’t exactly know what the proper response for myself is. How do you feel? Freaked out, or do you try and have life go on?

There’s often a disconnect between how things feel online versus in real life. Does that tension feel the same for you, or do you see these changes more clearly?

I agree, though I’m not really on social media. Like I only use Instagram on my laptop, so for the most part, I’ve managed to avoid that side of things, but I still feel that tension. But then I read about things going on in my community. For example, ICE agents are now trying to deport kids in schools in Chicago. So it’s hard to know at what point you really feel like your community is changing.

Black Country, New Road have shown continued resilience, no matter what the test or trial, or the changing of the times; together they have continued to press onwards. Together being of the utmost importance. From their meteoric rise and the critical acclaim of their debut album, ‘For the first time’ with its Mercury Prize nomination, through to their sophomore ‘Ants From Up There’ and now their third studio album, ‘Forever Howlong’, released on Ninja Tune, out on April 4th. Black Country, New Road have shown their singular ability to reconfigure their process and procedure, trusting their capabilities and their particular sound. A sound that arises only when this group of talented musicians come together in articulate arrangements that press the listener into a transcendental experience. With its bold vulnerability and sense of unity, ‘Forever, Howlong’ provides a map through the contemporary landscape of isolation and loneliness. Its thread being that of connection, seeking a path that becomes realisable through appreciation and reliance on those whom one surrounds themselves with.

To look beyond the confines, or coffin of individuality and understand that only through removing the bars of being self-absorbed can we truly find the beauty of a meaningful existence. Although, such an interpretation, Black Country, New Road were tentative to apply to the album, perhaps, they believe that such a realisation cannot be forced-upon the album, it is rather given as a musical offering, a gift through which the listener must themselves find the answers, the musicians themselves just giving the point of departure.

With the vocal duties shared between members, Tyler Hyde, Georgia Ellery, and May Kershaw - a sharing first, and successfully attempted on ‘Live from Bush Hall’ –now comes fully to life.

It feels utterly natural as they change between songs and fill the album with affective harmonies that embody the nature of ‘Forever, Howlong’. That community, that trust and mutual adoration can be delicately heard in those moments of collective harmony. Creating an essence related to feminist discourses of ‘sisterhood’, ‘friendship’, and a ‘politics of care’. The self-referentiality in the album creates a multi-layered musical dialogue, whereby a narrative is held and connects themes which traverse beyond singular songs.

A method they see as both amusing and humorous, whilst maintaining that it allows for the serious moments, of melodic expression and quiet sensitivity, to shine forth. Speaking to May Kershaw, Luke Mark and Lewis Evans, we delved further into the album, from its conception to emotions surrounding the upcoming tour. Attempting to understand what makes Black Country, New Road so unique, where their drive to constantly create newness comes from and advice for the next generation of musicians. Furthermore, their empathy for each other and love for music itself; what can the music industry do to protect the mental health of artists? And… being Radiohead for the day.

It wasn’t a surprise at all that Black Country, New Road have continued given what happened – with Isaac Wood leaving - but, how was that transition period for you, doing the Bush Hall Live album, and now coming into ‘Forever Howlong’?

Lewis: It was good. We did about two, two-and-a-half years of straight touring. So, we didn’t have that much time to write for the first couple years, we just played the Bush Hall album.

Then, we slowly started seeping new tunes into the setlist, which was quite refreshing because it got quite boring playing those songs, over and over again. Last year we had quite a lot less touring to do, so we did some quite rigorous rehearsal, writing sessions, Monday to Friday. We also had a residential set of gigs at The Cornish Bank in Falmouth. It was really lovely, we stayed in the venue and we played three shows, testing out different ways of doing the songs in front of a live crowd every night. After that it really felt that the album was there.

How did it differ from your previous album recordings, what was the velocity of the process, was there space for experimentation, feeding off each other, really how did the album come together?

May: A lot of that was done before we went to the studio in terms of, we’d played them a bit at The Cornish Bank shows. So, I’d say they were 80 to 95 percent, depending on the song. Even though three weeks is a lot, once you’re in the studio it doesn’t feel like that. You know, it was like one day per song, and then at the end, we had a few days to kind of go back around. The main difference was, there were more overdubs for this, the other albums, we all played at the same time, and tried to keep as much of that. I feel this felt a bit more like we were allowing ourselves to take a different approach.

We’re constantly called the ‘lonely generation’, or the ‘isolated generation’. But this album specifically feels rooted in connection, moving beyond that boundary of being self-absorbed. It has feminist perspectives of ‘sisterhood’, ‘friendship’ and a ‘politics of care’. Where did that come from, was it a narrative you were trying to push through the album?

Luke: That’s very interesting observation and very astute, may I say. It’s partly born of the process of making this album specifically.

When it came to Bush Hall, there wasn’t much sharing of lyrics and stuff and everyone was quite nervous to be doing that for the first time. With this record, we really wanted to make something that felt like a real album, that was very considered; in spite of there being different people bringing original song structures and lyrics.

It forced us to think about how they fit together a bit more, and that meant, being open with lyrics and being more vulnerable. To really understand what makes each song click, so that you can find what goes next to it. The other element is touring all of Bush Hall was quite, as Lewis referenced it, becoming quite tedious, playing the same songs. Coupled with just generally how difficult touring can be, not to complain about it, but, just on an individual level. I think through that, we learned to be more considerate of one another. We’re still working on it, but we’ve definitely improved. We were just talking about it earlier, the fact that we all need to feel good and be enjoying ourselves and getting along.

M: It’s interesting. Maybe every generation feels like the loneliest one? We didn’t really talk about it as let’s have these as the themes. But reading through the lyrics, I thought that as well, and that a lot of the songs are about trying to connect, or feeling connected to someone. I think that just came out as opposed to us planning it. Whatever songs we brought in, we would kind of work on and then slowly they felt more cohesive as it went along.

There is a lot of self-referentiality in the album, little discourses, and multi-layered dialogues. How do you go about creating those?

LE: There’s a good humour element to that. I think most of us really like the quite 60s, 70s style of referencing something musically that you’re saying in the lyrics like that happens a few times on the record. There’s a line in ‘Forever Howlong’ where May says ‘certainly causing my blues’ and then there’s a little blues embellishment on a recorder.

We’ve always liked that kind of stupid, immediate, almost really obvious connection between music and lyrics. We like for our music to be humorous in some ways because a lot of us find music that’s too sincere, or at least that doesn’t have any sense of humour, it lacks something.

LM: If you’re trying so hard to appear serious, you look really unserious. So you’ve got to be a bit funny if you want people to be like, Oh, they really mean it when they’re doing the sad bits.

So, you need both elements to balance each other out?

LM: It’s like life, you know?

LE: I also think that our musicianship is very unique, and the way that we play our instruments and interact with each other musically, has its own sound and so that can be heard throughout the record. That creates a kind of selfreferential thing. Doesn’t really matter what the source material is, we usually sound a certain way as a band. All that ties up with trying to create an album that makes sense, that feels cohesive, even with different singers.

The notions of liminality and space or restraint are present on the album. What caused that change?

LM: An interesting point. Yeah, I think we definitely did try and bring the peaks down. Although, none of our music has been particularly subtle. I mean, I would argue that this album is not particularly subtle.

LE: It is more restrained.

LM: Yeah, we’re finding new paths through the thicket. You know, I think that vocal harmonies, it’s definitely something that we tried, maybe it was ‘Cold Country’ first.

As soon as we did that and realized how great May and Georgia and Tyler sounded singing together, we were like that can be a bit of a thing that we can use throughout the album because it was compositionally like novel to us and felt effective. Partly because it was just the sound of unity, people singing together.

LE: I think also in terms of restraint, we maybe didn’t discuss it as restraint, but we definitely discussed with every song - is what we’re doing to this song serving the song, and is it doing the best for the song? And if it wasn’t, then we needed to pull it down a little bit and bring down the arrangement that we were doing to it because the essence of the song was lost.

You have had some complications with touring your studio albums. Are you looking forward to really being able to tour one for the first time properly?

LM: Getting to tour at all and play shows is an amazing privilege and a great, fun thing to do. The shows themselves are always the best bit. Getting to go to cool places is amazing as well. I’m personally quite excited about trying to represent the record a bit more accurately than we might have been able to before. To try and really put it across as best we can, rather than, sort of, we’ve kind of been flying by the seat of our pants for like, years, you know.

LE: Yeah, we have the jankiest gear as well. Like, honestly, the stuff that we were touring with until last year, it was just ridiculous. Like, whenever there’d be a festival where you load in all of your stuff in the backstage or whatever, and you just see your gear compared to, like everyone else’s. It’s just it was crazy on a ramshackle budget. I’m definitely looking forward to, it is crazy that we’ve never toured a record before, like, that’s really nuts. And we’ve been really lucky to, you know, to be at the point we’re at and be able to play the venues we’re at, the venues that we can play at, and to have the demand that we have from not touring a studio album before, that’s pretty amazing.

LM: You know what May; I’m interested to hear what you think about this. Georgia said to me earlier, because she’s obviously toured with Jockstrap, and she said as soon as everyone knew all the lyrics to the songs and was singing along, it was like the easiest thing in the world, and it made the shows much more fun. But I can imagine that’s like, probably a bit of a double-edged sword. It might be a bit weird. What do you think that’s going to be like, everyone singing back at you?

MK: Yeah, I think it will be weird. I think it would be quite impressive if people could sing along to, say, ‘Forever Howlong’. I guess when we play that live I’m conducting, so maybe.

LM: Maybe you can start conducting the crowd?

MK: I don’t know if that will be a sing-along, to be honest, I’m not sure if any of the ones I’ve brought are particularly sing-along.

I couldn’t really imagine one of you doing a Jacob Collier-esque show for BC,NR, it would be a bit complicated… How do you go about creating that constant newness of your sound, was that always part of who Black Country are, a core identity?

LE: I don’t think it’s ever discussed. I think it’s because we really love music, and we’re big music fans, and we love to listen to music. And if you’re a music fan and you love to listen to music and you spend a lot of time doing it, your taste evolves loads. This new album is what I’d want to listen to, you know, we change lots, and we change as people as well.

So, there’s no point in continuing to make the music that came from older versions of ourselves.

LM: Oh, that’s good answer.

New music is littered with your influence and inspiration. I was wondering how you feel about, or deal with that? And was there a group you saw that made you truly believe; we can actually do this?

LE: black midi. Black midi were about a year ahead of us in everything we did. We had the same booking agent, so we played the same festivals, and they would be on the stage that we were going to go and play the next year. So, we became really good friends from that experience. We both had Speedy Wunderground singles; they released an album and did the Mercury Prize a year ahead of us. We were just like, following in their footsteps a little bit. So that definitely that made me feel like everything that they’re doing is possible for us. In terms of bands taking inspiration from us, this is maybe a cliché thing to say, but like, they’re probably just tapping into stuff that we were tapping into as well, music that inspired us for ‘Ants From Up There’. It’s probably on people’s playlists or on people’s radar a lot more now. But I think there’s a lot that young bands are tapping into that isn’t us as well.

What can musicians, labels, the industry, and then similarly fans and critics do to protect the mental health of artists, of musicians who have intense touring schedules and commitments whilst being in the public eye?

LM: That’s interesting. First of all, I think I would say the fans and critics thing, I don’t really think it’s on them to make sure bands are okay. Obviously human decency goes without saying. But, you know, I do think that criticism in whatever world you’re in is kind of a good thing broadly. And it’s a thing that everyone should take from what they will. You know, it’s not like anyone’s word is the be all and end all of anything, it’s generally a vehicle for good and for making art more broadly seen. With fans, I don’t think there’s a world in which the fans are making any artist’s life more difficult, it’s generally the reason that people are able to do what they do. The industry side is maybe more difficult.

LE: We have an easy ride in the industry. We are on an independent label that don’t push us to do things as hard as a major label would. They have no input on our music, at the end of the day, we do what we want. I think the problem is when you see bands like Wet Leg and The Last Dinner Party a couple years ago when they were playing like 150 shows in a year. Massive respect to the bands that do it, but I felt worried for them. There’s a lot of artists who are pushed to play a lot of shows and that can come from label pressure. I don’t know if it did in that case, it’s hard to know, they may have just taken on a lot of gigs. But it all kind of comes down to the fact that’s really the only way you can make money. So, I would just say the main one is if Spotify, Apple Music and all the other streaming platforms paid artists properly then people wouldn’t have to put themselves in such vulnerable positions.

MK: Tour is a different way of life, that just suits some people. I think for us, we are just careful trying to get the balance right, and we talk about it a lot. I think it’s good that we have culture within our band, talking through everything and feeling heard by each other, our management and our booking agent. Hopefully there are more people like that in the industry, which I’m sure there are.

Is there somewhere you haven’t been, or a venue that you’re most excited to play?

LM: Mexico City. We are supposed to be going there this year and I’m excited for that, it’s just a new experience.

LE: Excited to go back to Vega in Copenhagen. Where you get cooked a Michelin star meal for lunch and dinner. And, the chef has a dog called Ruby, a really well-behaved dog. You get there on the tour bus, and you wake up in the morning, roll out of bed, go into the kitchen where he prepares you a ridiculous lunch. It’s pretty amazing.

LM: It’s like being in Radiohead for a day.

MK: Maybe going back to Japan. I’d like to play some other cities.

Any message about the album, the tour, gigs, that you would like to share?

LE: Just Keep Rocking in the Free World - Obviously.

Emerging from the bustling but underreported Cork alternative scene, bands like Pebbledash don’t fall from trees. Like many bands hailing from the Rebel City, Pebbledash are a sleeping giant; understated and predominantly unknown, but utterly fantastic. When the single ‘Killer Lover’ appeared in my inbox, I fell in love with the band and their immense capability to marry human emotion with their love for abstract noise and melody; and now after a long road, they’ve released their debut EP ‘Two Portraits of the Same Ugly House’.

The EP is a project with class that seeps eerie moments of noise rock anchored by the tale of creatives in modern day Ireland. For a band so new there is a clear sense of heart and care placed into their craft as they work to define themselves completely in just four tracks. Ahead of an evening practice session, I sat down with Fionnbharr, Cormac, Asha, Jack and Eoin of the band as we covered all the bases of Pebbledash.

Your Debut EP ‘Two Portraits of the Same Ugly House’ is out now, what are the emotions going into a release week?

Asha: It’s been a long time coming and it’s a relief in some ways that we can get it out there. Some of the material on the EP predates people being in the band so we’re excited to get to work on creating fresh music together. I think the EP captures the time of starting working together as a band and is a great representation of us figuring out how we wanted to sound while also getting to know each other.

Fionnbharr: Yeah making this EP was basically us trying to see what’s going on inside each other’s heads

Debut EP’s often end up being all the songs they have written put together but yours definitely feels more conceptual..

F: All the songs were written at the same time and I think I’ve always had the belief they’d be released together. They’re all connected thematically and I hope when people listen to it back to front they’ll digest the personal journey and all the emotions that we tried to get across.

I think an easy place to start is Cork City. You wrote the EP in and about cork, what importance does location have for your songwriting?

Cormac: Certainly there’s a big influence through the lyrical imagery and the instrumental from Cork and someone from Cork or a musician would definitely pick up on that. The music scene here is such a fertile environment that all creative fields here are a massive influence on our songwriting.

F: I’ve been saying recently that Cork City creatively is like a floodplain; It starts up at the Shely Mountains and flows down through the county and all the good stuff ends up getting soaked up in the city.

It’s been nice to see a peak in interest in Irish music from the mainstream recently…

C: It’s definitely been nice especially with the success of Lankum giving a modernisation of folk traditions and these drawn out long form tracks, but alternative music like this definitely hasn’t only come around recently there’s been so many great acts coming out from Cork alone. There’s a brilliant band called She who’ve been a big influence to us. Even going back to the 80s there were great bands like Microdisney and Nun Attax. The scene has always been there under the surface but we’ve waited a long time for wider appreciation and it’s great to see that moment has come around.

Atmosphere is a big part of your songs, they’re almost scary at points. What do you intend the listeners to feel when they hear this EP?

A: I think it’s an even bigger part of the live show. We always tried to make our set as much of a performance as possible atmospherically and we wanted to translate that into the recordings. When I’m on stage I like thinking that I’m not really there and I’m in some transcendent place. I’m more interested in being a conduit for whatever emotions I’m trying to get across. Something I love about Irish culture is the ability to go to these really dark places and find your way back to the light and we try to achieve that throughout our live sets and recordings.

F: As much as there is power in words, sometimes there’s only so much they can do and it’s important to translate our feelings into what we play or what we don’t play.

A: Also we like to think of our project as world building in a way; it’s more than just an atmosphere, it’s an emotional landscape that we want to take the audience to.

Many of these tracks involve grand endings that build themselves from a flurry of noise, I was wondering what your songwriting process looks like? Do you intend for tracks to end in such a grand manner or does it happen naturally?

F: I think up to now it’s happened naturally, especially with the songs I wrote. It came just from playing the song and drawing it out.

C: Part of it is the amount of members we have; we’ll all contribute different chord progressions and riffs and when all our ideas come together the songs will end up being these lengthy tracks. The structure of the band blends itself into our expanded song. Also all of the bands we take influence from have these atmospheric elements with massive bursts of noise and feedback.

F: I like to think we do it in a controlled manner and I think the next phase of Pebbledash will have less 6 minute songs.

Do you have a 3 minute ‘pop banger’ coming soon then?

F: I don’t think we could, physically I don’t think it’s possible.

A: We wouldn’t be able to say what we need to say!

You’re building up lots of interest from considerable radio airtime and major discourse online, does this attention motivate you to achieve bigger things moving forward?

F: It’s nice to get attention and it being able to prolong you making art. It’s helping us make this a full time thing. I still feel we’re quite underground as snobbish as it sounds; I think we’re still overshadowed by the Dublin bands.

A: It’s encouraging to see people turning heads because we want to do more and more work. We’re all loved up by this project and we want to keep going as much as possible.

Your first shows outside of Ireland are taking place this month, how do you expect new audiences to react to your sound?

A: I’m intrigued to see how people will perceive songs especially ‘Carriag Annor’. I Think it’ll be some people’s first time hearing people sing in Irish.

F: I think it’ll go down well, I think our difference will be to our advantage. The musicality of it is universal and that I think will translate well to audiences.

Jack: You can’t rely on the audience too much, you have to enjoy yourself!

If you can summarise your sound in 3 words for new listeners what would you say?

F: Just simply delightful.

C: Hoarse, beautiful and ugly.

A: Bathing, whaling and brooding.

J: Ominous, sombre and mossy.

Frontman, James McGovern, greets me from across the English channel, over Zoom, from a rainy evening in Paris. Doing his best Owen Wilson impression, he says. It’s Paris Fashion Week, and he’s visiting, as rockstars are wont to do, to see friends, as well as what one imagines is to mingle amongst the social elite at various canapé-laden cocktail parties (pure conjecture on my part, of course).

It’s been six years since The Murder Capital released their debut, ‘When I Have Fears’. Now on the brink of releasing their third album, ‘Blindness’, our conversation traces their evolution through writing, patriotism, balancing artistic integrity with commercial success, and never truly being able to grasp more than a tiny part of one’s emotions, ideas, or even self. We are, to pardon James’s own pun, blind to the rest.

It’s been six years since ‘When I Have Fears’. Is it all still as exciting as it was at the beginning?

Our story like many bands of recent years is coloured with the stain of the pandemic. Before that, releasing the first record was exciting and, due to its content, it was necessary to make…without sounding too self-righteous. But it did feel like, for us, all the albums since then have kind of remained like that in different ways. For the first time, this album felt free from that waste of a very particular event. So that was nice but it created its own friction because that’s what I was used to. We were used to facing this monster.

Has heavy touring replaced that monster?

I don’t think people realise how much free time you have when you’re on the road, it’s a blessing and a curse. It’s a killer if you’re spending it hungover or depressed, it’s like waiting at hell’s gate. But I try to just keep writing, keep working.

How do you find motivation to write when your reality on the road can be static and stagnant?

It’s a fool’s game to think it really matters because all of a sudden you’re confining your idea of inspiration as needing to be a part of the writing process, which it doesn’t.

If you’re an artist you become inspired at different times but you can’t predict that, so the best thing to do is to keep working.

How was going back to L.A. to work with John [Cangelton], who produced ‘Gigi’s Recovery’?

There’s not really anything easy about John, the same way there’s not much easy about us. But when we come together to record, there’s an interesting reaction. That’s why we went back, he drew a lot out of us.

Was the fevered energy of this album a reaction to the last?

Nail on the head. When we made Gigi we had enough time to make the decisions that we did and we wanted it to be quite grand at times, we wanted the intros to be novels in themselves. It’s definitely indulgent in a cool way I think, and we wanted to cut the fat off that way of setting up structures within our music. We’re still doing that a little bit on this record but overall once the needle drops, you’re coming up in it.

Did the difference come naturally?

Making an album is a strange old game.

You’re led down all these garden paths, and you’re semi in control but you’re writing with other people, and we mostly live in different countries so we’re growing in our own way. Some people told me I was ridiculous to say it, but I genuinely feel like we’re an actual band now. A lot of this music I really wanted to make for a long time. The lads share that, everyone loves this record.

There’s a natural pressure in music when it comes to charts and all that stuff and you become, pardon the phrase, blinded by that. But on this record I really don’t care, it’s nice if it does well but I don’t feel any pressure to get a number one or a top ten.

Creativity doesn’t lend itself to a corporate world, I imagine it’s a hard thing to balance.

Yeah, I’ve tried. I’m happy with where we’re at in our career. You work for so long on this music that you love and put so much of yourself into it, and then for a number to lay out the path of your pride, that is sad.

So there’s a maturity to this album?

There’s a self-assuredness. I don’t really give a shit what anyone thinks about it, in the best way. There’s still the human desire for people to connect with it and like it. You can’t really turn that off unless you fall into some sort of sociopathic headspace. But we’re not 18 anymore, I just turned 30. So I feel mostly whole in my body, even if it’s uncomfortable at times. I think I know myself now.

And yet its themes are consumed by uncertainty.

‘Blindness’, the album itself, is just about how much we’re missing. It’s an admission. I hope that it’s an acceptance of that because I think that’s the jumping off point to a deeper understanding of the (sometimes) shallow nature of life. You can’t be an expert on everything. When it comes to our needs, our desires, we don’t know what we need half the time. There were times when I was writing these lyrics where I would step back and think, I feel like I’m getting closer to something. Am I getting closer? I don’t know. There’s parts that feel close in the process and others that feel totally unknown. I think that’s a reflection of an apparent sort of truth…

For the first time. I always felt our music was coming from a universality. But ‘Love of Country’ is summing that relationship up for me. I’ve wrestled with patriotism for a long time. Certain actions of nationalistic ideologies definitely marred or distorted my view of Irishness and national pride. I’m just now coming out of those woods where I can see what it means to be truly patriotic in a constructive way.

Speaking as an Irishman, there’s a vibrating sense of pride I feel in annotating myself as that. I have pride for the culture. There’s so much to be proud of. And this goes for any country, but if you want to talk about protecting culture – which is the hardest word I could use from a nationalistic vernacular – you need to welcome diversity into it. Having pride for where you’re from has no room for total ownership. We were all born into a lottery and we should be proud of our culture and be aware of the missteps in history that were taken both against us and by us. I think that’s something that’s missing in British culture. But I wouldn’t ask for anyone in Britain to feel a deep sense of shame for something they didn’t do themselves. But to learn from that as we watch these nationalistic ideologies rising across the world. It’s scary. And I think we’re all scared. This is what patriotism can be warped into. And what it should be is a pride for where you’re from and an openness to diversify that because culture is made of human beings. Irish culture was not made solely by the Irish, it’s made by all these interesting people coming from all over the place. And that’s the way the world works, whether people like it or not.

Shane MacGowan is the subject of ‘Death of a Giant’, what does he represent to you?

A vulnerability and almost superhuman closeness to the essence of humanity. He was obviously vulnerable just due to his alcoholism. But all that aside, whatever pain he was in, he was able to put his fingers so accurately on the pulse of frailty and the vulnerability and beauty of life itself.

Where were you when he died?

I was in Heathrow, flying to play Other Voices in Ireland. We went straight from there to the studio in Dublin. His funeral procession came down Pearse Street before it headed on to Nenagh, Co Tipperary. It was a very striking day, the imagery was almost impressionistic. These gallant horses with feathers coming out of their attire, and the marching band – all adolescents – and at the end of it, this beautiful chemist with this old man sat outside it singing old Pogues tunes. I didn’t really think about writing a song about it, it just came out.

As the best things often do.

That’s right.

Sam Akpro’s is held in very high regard in South London’s music scene and for no shortage of reasons. He has earned it.

The music he makes is a rich and immersive alchemy that pulls you in and dissolves the world around you. It might sound like one, but it is no over-exaggeration to say the live shows restore your faith and hope in the world.

Chatting to Sam about his debut album ‘Evenfall’ it feels like the culmination of all his graft in this enormous, sprawling city and the record a vivid portrait of its neondrenched, shadowed streets. It is a collision of post-punk grit, dub echoes, and trip-hop haze, alive with London’s restlessness. But at its heart, ‘Evenfall’ isn’t just about sound; it’s about movement, disconnection, and the weight of the everyday.

Poet James Massiah described it much more succinctly ‘ Play the record. Be you sane or wild.”

Your debut album is finally on its way. How does it feel to have ‘Evenfall’ announced?

Yeah, it’s exciting man. I’d been thinking about making something longer for a while, but I really locked into it around the middle of last year. EPs are great, they teach you what works, what doesn’t, and what you want to explore. But at some point, I just wanted to put it all into one thing—something that says, this is what I do. No jumping around, just a body of work that makes sense as a whole. And I wanted to prove to myself that I could do it.

So does it feel like the album represents who you are as an artist? Or is it more a snapshot of that time and feeling?

Bit of both. It’s cohesive, but there’s also this bipolar energy to it—like, one moment it’s driving forward, and then it’ll stop you in your tracks.

That’s just how I feel sometimes. I think that’s who I am as a person too. The album flows in a way that captures that, even if I didn’t sit down with a plan to make it that way.

That push and pull, the contrast between control and chaos, really comes through. Were you conscious of balancing those elements, or is that just how the music naturally comes out?

It’s just how it flowed. I wrote everything at different times, so there’s this mix of intention and spontaneity.

Take ‘Baka’, that instrumental track, the weird electronic one, I wrote that four years ago, just messing around. No plan, just playing with sounds. Then there’s ‘I Can’t See The Sun’ which came out of a really specific moment, summer 2022, late at night, free house, just sitting in my mum’s living room. It felt different to anything I’d made before, like something I’d been searching for. And then ‘Evenfall’ was me trying to write but feeling stuck. I didn’t like it at first. But then I listened back the next day and caught something in the guitars. That’s how it goes, each track comes from a different moment, and then they all end up together.

It’s interesting that you mention ‘Baka’—it’s a real standout moment on the record. Have you always played around with instrumentals like that?

Yeah, that’s how I started making music. Even now, the instrumental side of things is still where my head is first— it’s the foundation. Lyrics are important, but the music leads. ‘Baka’ was one of those rare ones where everything clicked. I’ve tried to do stuff like that so many times and failed, but that one just worked. Probably my favourite track on the album for that reason.

It feels like a turning point in the record too. And I know you worked with different musicians across the album—how did you bring that group together? Were you ever all in a room at the same time?

Not really, man. Finding access to studios isn’t easy, so it was more like a patchwork of different places, and different times. The sax on ‘I Can’t See The Sun’ came from a jam with my guitarist Cameron Jacobson and Isaac Robertson. We were in the studio, just playing, and I ended up cutting pieces of that into the track. Other bits were just recordings from random sessions. I was sampling myself, sampling other people, just stitching things together.

You recorded all over London - Peckham, Brockley, Tottenham, Camberwell. Do you think those locations influenced the sound?

Maybe subconsciously, yeah. I get different vibes in different places. Brockley is home, so that’s where I write most of my stuff - it’s where I’m comfortable. Camberwell is where I worked with Finn Billingham, who’s helped me make my music sound good from the start. Then there’s Shrink in Tottenham, who pulled everything together. So yeah, all these places shaped it in different ways.

The album is called ‘Evenfall’ - that word really captures something. What made you choose it?

It’s that time of day, just after sunset, when the air shifts. That’s when I like to be outside, when everything feels a bit calmer. I made ‘I Can’t See The Sun’ around that time, and it felt like the right word for it. I literally Googled: “what’s the word for this feeling?” and found it. It just sounded right. There was maybe one other name in the running, but it was a bit cheesy.

Can you tell me what the cheesy title was?

Oh, I can’t tell you that, man. I can’t tell you that.

Fair enough! The album comes with a poem from James Messiah - how did that come about?

Me and my manager were trying to find ways to describe the album that weren’t just the usual press release stuff. We had the music, the videos, but we wanted words too; something that really captured the feeling of it. James just nailed it. It’s cool to have someone else’s perspective on the record, not just mine.

It does add a whole extra level to it. And listening to the album, there’s a cinematic feel to it - it flows almost like a concept record. Was that intentional?

Not at first, but yeah, once we had four or five tracks, it was like, okay, there’s a vibe here. I didn’t set out to make a concept album, but I do like having a thread running through. It helps that each song was written at different times of day, some in the morning, some late at night. That gave it a kind of natural order.

Your music blends a lot of influences, jazz, soul, rap, post-punk. Does your listening jump around like that when you’re writing?

Yeah, always. Before the album, I was listening to everything, then when I was finishing it, I barely listened to anything. I was burnt out, just fully locked into making it sound right. Now I’m rediscovering music again.

What’s in your ears at the minute?

Let me check… A lot of hip-hop. The Alchemist, Larry June, Roc Marciano. Some weird 80s post-punk. There’s this band called The Low Yo Yo Band, they had one album, produced by Charles Bullen from This Heat. Just odd, mad guitar stuff. And a lot of 70s records. I’ve been deep into YouTube, finding things to sample.

With the album out, you’re heading into live shows. How are you planning to bring that atmosphere to the stage?

Yeah, that’s what I’m most excited about. I want it to feel more ethereal, more droney, less heavy. Less like a rock band, more like a moment. You can play as loud as you want, but if there’s no emotion, it doesn’t hit. Playing quietly, but with intensity—that’s where the feeling is.

Yeah, someone once told me, if everything’s loud, nothing is.

Exactly, man. Facts.

I’m in the Netherlands and loved seeing you play in Rotterdam at Left of the Dial. How did Europe compare to the UK?

That was one of the best experiences we had. European crowds are different, they just turn up for the music, no expectations, and no need to win them over. London, you have to prove yourself every time. But over there, people are just locked in.

What’s next? Are you already thinking about new music?

I’m in a really creative mode right now and just making as much music as possible, trying to move forward. I’ve learned so much from making this album. I wouldn’t say I fully know what I’m doing, but I know enough to figure out the next project, whatever that may be. I don’t want to speak on something that doesn’t exist yet, but I’m excited to see how people connect with ‘Evenfall’; whether they love it or not. I listened to it so much while making it, it felt like my child. And now, it’s like sending it off to uni. Out of my hands, off into the world …

I will let James Massiah’s close us out: “Here’s the story of the night. Up for all of it. Right till the sun rises. We played the record.”

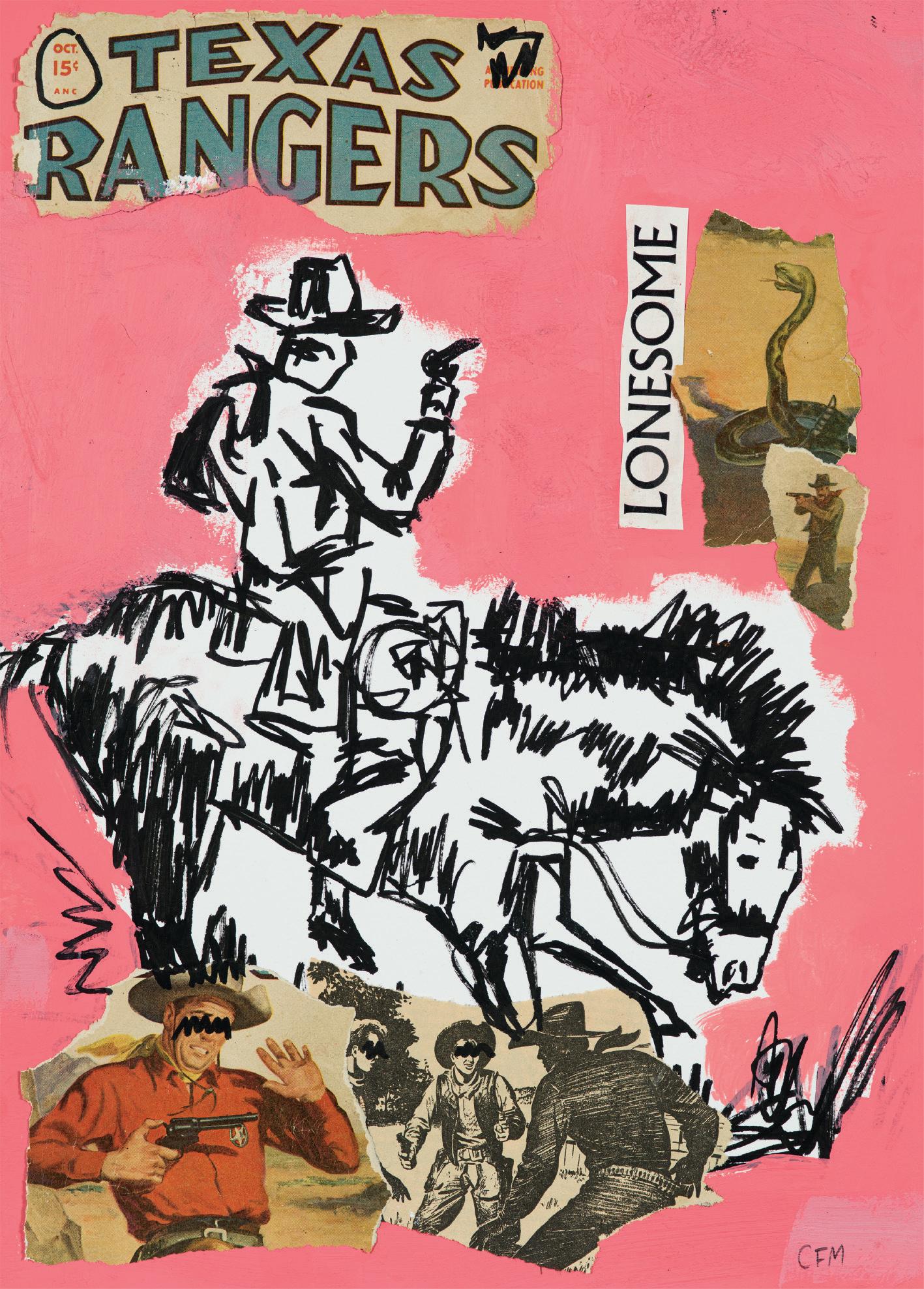

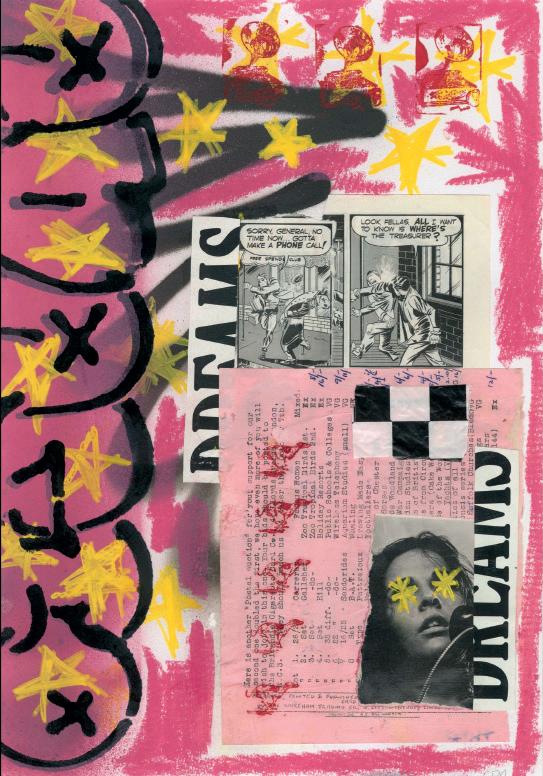

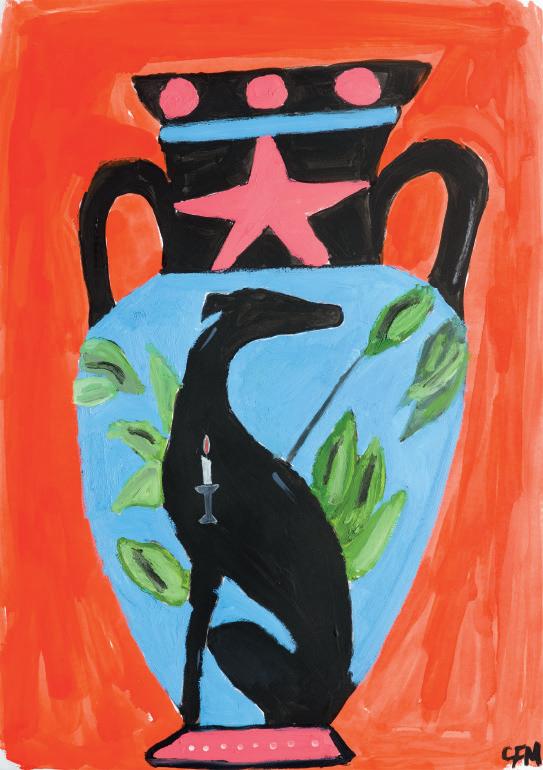

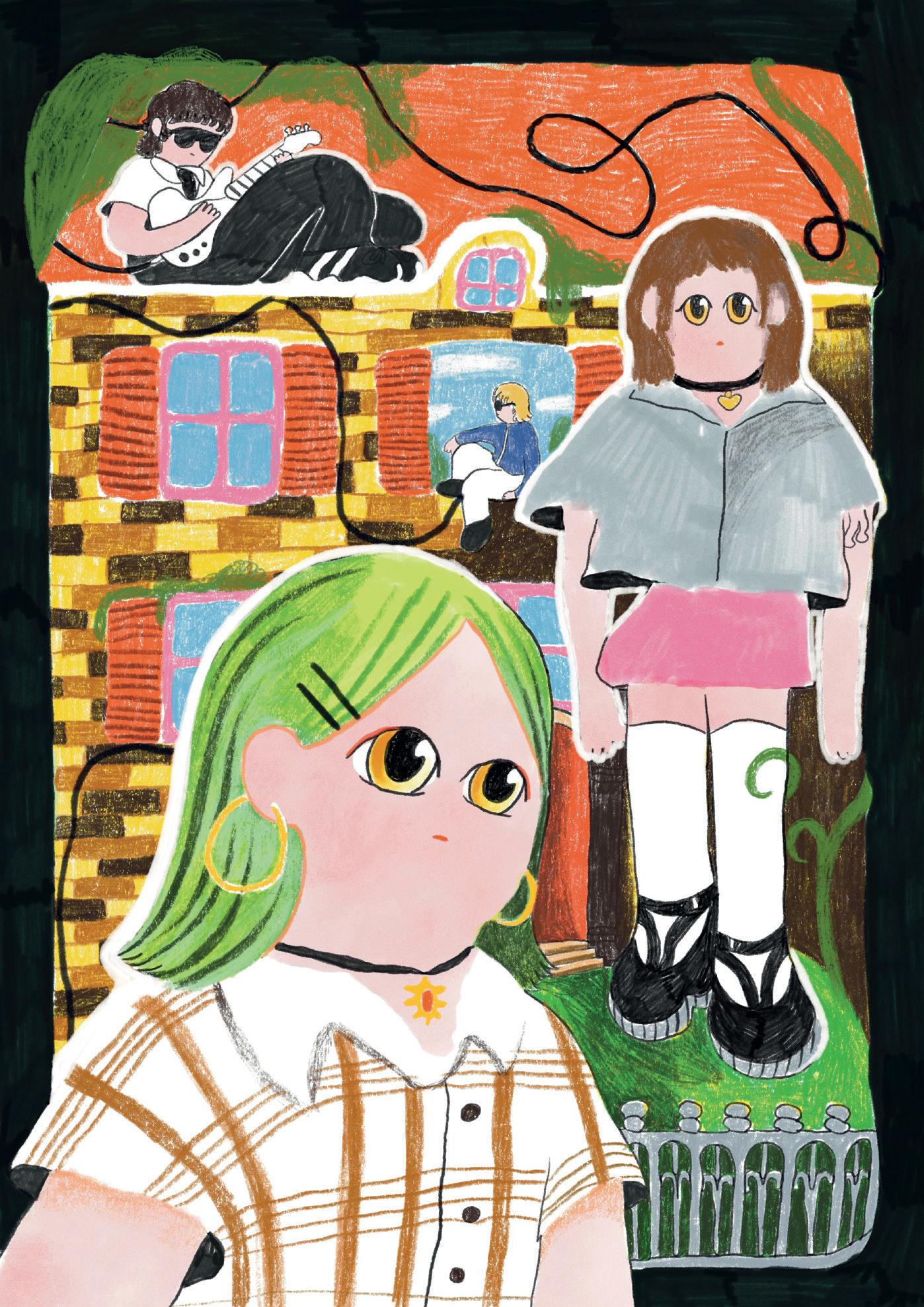

Caitlin Flood-Molyneux grew up in Pembrokeshire, South Wales. Viewing art as an escape from the challenges of School, Caitlin went on to study art at college as soon as possible. Beginning with graphic design before moving on to a foundation degree in art and design. Caitlin then pursued a fine art degree and a master’s in Cardiff, with a year abroad in Norway during their degree at Bergen University. This experience was to broaden Caitlin’s perspective and shape their artistic journey. Caitlin’s work has since received critical acclaim and has certainly caught our eye here at So Young. We asked some questions to find out more.

How would you describe yourself and your practise?

I would describe myself as ambitious, always striving to push my creative boundaries and grow both personally and artistically. I’m constantly seeking new challenges and experiences that inspire and elevate my work. My artistic practice investigates the relationship between pop culture imagery and the way in which we attach emotion and memory to images. I use this to narrate experiences of love, loss, grief, and nostalgia. My work invites the viewer to reflect on their own memories, much like the way a familiar song can transport you back to a specific moment in time.

How has growing up in Wales affected your work and career?

Growing up in Wales, especially in a working-class family, I never thought being an artist could be a reality but I’ve always been a big dreamer. My work is deeply connected to my life experiences, and a significant part of that is rooted in my upbringing in Wales.

Recently, I toured a solo show, including an exhibition in my hometown, featuring paintings inspired by the place and experiences that shaped me. That experience made me realize just how important Wales is to my practice.

At the same time, I’ve always been incredibly ambitious, and being in Wales has never stopped me from pushing to get my work out into the world. I’m proud to be able to travel with my work and say that I’m from Wales. Finding a balance between working in Wales and showing my work elsewhere feels essential; it allows me to stay connected to my roots while continuing to grow and reach new audiences. I strive to maintain a balance between working in Wales and exhibiting elsewhere, as both are essential to my growth as an artist. My work is a reflection of my journey, rooted in my past but always looking forward.

What inspires you to start a piece of work?

I feel inspired to make work when I see something that reminds me of an event or experience in my life. Certain images, objects, or moments trigger memories that I feel compelled to explore through painting. My process often starts with that initial spark of recognition, something that resonates emotionally or nostalgically which then evolves into a collage, painting or drawing that recontextualizes the memory. In a way, my work is about capturing and transforming these fleeting moments into something tangible and expressive.

What’s your routine like? How do you begin your painting process?

I don’t have a set routine when it comes to scheduling my work, it’s entirely driven by urgency and instinct. When inspiration strikes, it’s a feeling of ‘the time is now,’ and I can’t focus on anything else until I create. My process begins with imagery and memory, something that sparks a connection to an experience or event in my life then I start working through it visually. I develop drawings and collages to explore compositions, which later evolve into larger paintings.

Painting is a way for me to process my life; it allows me to navigate emotions and memories. Most of the time, I paint at night when my mind is at its busiest, it becomes a form of escapism. Sometimes, the process starts with an urgent need to express something, almost like journaling, where I can translate thoughts and feelings into visual form.

How do you source the materials for the collage elements of your work? What’s that process like?

All the collage elements in my work come from vintage magazines, mostly from the 1940s and 1950s. I have hundreds covering different topics, and I started collecting them in college while studying graphic design, initially focusing on typography. Over time, it became part of my process. Sometimes, I also create my own collage pieces by ripping up old paintings and drawings. I love searching for vintage magazines in charity shops, it’s exciting to find inspiration in something with a history that resonates with me.

Do you remember when you were first exposed to Art, in a way that resonated with you?

Growing up, my house was filled with large, colourful abstract paintings, which I later realized were my mum’s. Art has been part of my life for as long as I can remember. My mum, a talented artist who became a staff nurse instead of pursuing her creative dreams, always encouraged me to be creative. My earliest memory is painting with her. I was lucky to have such a supportive parent who nurtured my passion. I also remember looking through art books, like those on Matisse, at a young age. Art has always been there, shaping me from the start.

Are there any questions you’re trying to answer in your work?

It’s less about asking questions and more about reflection through my work, I find myself discovering more about who I am. But if there is a question at its core, it might be: how do past experiences shape us? My work explores that answer, using memory, nostalgia, and found imagery to piece together moments that feel both personal and universal.

How much of your personal experiences are in your paintings?

My personal experiences are at the heart of my paintings. Every piece is connected to a memory, emotion, or moment from my life, even if it’s not always obvious. I use found imagery, abstraction, and collage to explore nostalgia and personal history, transforming experiences into something both deeply personal and open for interpretation. While my work starts from my own story, I want viewers to find their own connections within it.

There are many artists I admire, but Robert Rauschenberg has always inspired me with his use of mixed media and collage, transforming images and narratives in a way that feels dynamic and unexpected.

I also love Gillian Ayres for her bold use of colour, abstract forms, and collage, as well as her energetic and expressive approach to painting.

What creative activities do you take part in outside of painting?

Outside of painting, I love photography and filming. I have a huge collection of vintage cameras and have always enjoyed capturing moments through photos and video. If I wasn’t a painter, I’d probably do something with cameras. I also have a big interest in fashion, and honestly, I enjoy anything creative. Creativity in all forms excites me and feeds into my work in different ways.

Is there specific meaning or personal narratives attached to some of the objects/subjects you paint?

All my work carries symbolism connected to my life. I used to be vague about these meanings, almost as a way to protect myself, but the truth is that everything in my paintings is deeply personal. Many of the symbols and imagery depict scenes and places from my past. For example, the three stars that appear in my work represent me, my mum, and my brother. It was always the three of us. Threes have been a recurring theme in my life, and the stars serve as a reminder of home, of what was, and of the importance of remembering my past. They also symbolize grief not just as loss, but as a reminder of love, something that never fades.

What are you currently working on? And what can we expect to see from you in the near future?

I’m in an experimental phase right now, exploring new symbols, media, and ways of working. I’m thinking about what I want to say with my work and how I want to say it. I’m particularly interested in incorporating textiles into my paintings, and at some point, I’d love to create clothing. This year, my focus is on making new paintings and pushing myself creatively. I’m excited to see where this exploration takes me, I always say I never know what my paintings will look like in a year, and that’s what keeps it exciting.

Eschewing minimalism for an unconstrained blend of garage-punk, Swedish newcomers Clutter come armed with a riot of different influences and an unfettered love for what they do. Each just twenty years old, the four-piece join the video call from a variety of different locations, rushing to find a quiet spot after leaving a class at university, or ensconced in a Dalston Starbucks to exploit the chain’s free Wi-Fi. There’s something joyous about being briefly invited into their world – colourful and chaotic – especially from my tonsilitis-imposed isolation. For half an hour, their commitments and busy lives are put aside to talk about the one thing at the centre of their friendship with one another: the band.

How do you want to introduce Clutter to the world?

Emma: The video to ‘Jesus’ is a great introduction to the band. I think it’s just the core of the whole thing – both the song and the video.

Hilda: It’s a good introduction, better than us saying something about the band.

That makes sense – start with the music. How did you guys all meet, and how did Clutter form?

Ove: We all met in school, four years ago now. Five years almost. Then we started playing together three years ago, and the band just formed.

Did you guys grow up around music?

O: Yeah, everyone did in their own way, I think.

H: I remember playing a lot of ‘Just Dance 2’, and finding a lot of music through that game. I found Avril Lavigne, Britney Spears… I don’t know if there were any cool bands. Well, Avril Lavigne is cool, but I don’t know if I can say something “alternative”!

O: I started listening to music when I got into Nirvana and grunge, when I was twelve. That really changed a lot of things for me.

You touched on the idea of whether or not Avril Lavigne is “cool”. Do you think that matters?

H: I think she’s really cool! I just meant that I don’t know if I can name something underground from my childhood. But she’s amazing, and she’s the person who made me want to start playing.

With Avril Lavigne as well, her whole aesthetic is just as important as her music, and I know that’s something you guys have talked about. What would you say your current influences are, both sonically and aesthetically?

Ville: We all have different influences. To speak for myself, I guess I would bring up a lot of sludge metal and hardcore bands, just in terms of drumming style. But I don’t know if I’m really qualified to speak on the visual or aesthetic part.

O: I think visually we’re quite inspired by a lot of the aesthetics from the 90s and 2000s, but also we try to see what’s going on around us in the present time.

You’re all 20, and you’re all very busy. How do you balance Clutter with the other elements of your lives?

H: I think it’s been quite easy so far, for me at least! I only have uni two or three days a week, so I always prioritise the band. It’s a good centre point.

E: I think it works as well because we all really want to do this. Hilda was starting another school, but that would have taken up a lot of time, and she made another decision just to play with the band instead. So I think we all just put the band in first place, and the other things beside.

V: But it’s not impossible to find balance. If I’m going to talk about university, it’s pretty flexible with when you decide to study, and the band is also that way. You have to have foresight, but we’ve never had a big crisis with schedules.

O: As long as the four of us are involved socially with each other, the band is moving forward. Even if we’re not playing music.

That ties into what you’ve said previously about how the band is ‘more than just the music’. How does that perspective inform Clutter?

O: Music always comes first, but content and the visuals nowadays can feel just as important.

But if you care about the visuals and the aesthetic, it’s not a problem to involve that in the music.

E: I also think that our friendship really has affected the music. So, even though we’re just hanging out, that’s part of making music. We wouldn’t make the same songs ourselves; it’s us four in a group.

What would you say the music and arts scene in Stockholm is like at the moment?

O: It’s thriving. We got in the music scene as soon as we turned eighteen, and it’s been very overstimulating. There are always things happening.

E: It really feels like a community. We know a lot of different bands and DJs and that’s really fun to be a part of.

How does gigging in Stockholm compare to London?

V: Whenever we play in Stockholm, it’s in the same circles. It was hard to gauge, when we played at the Shacklewell Arms, if it was the regulars. It felt more like random people who had just decided to stop by! The engagement was a bit broader, and spanned across more people.

O: When you play in Stockholm, you’ll reach out to the more niche group that might have seen you two or three times before. It’s fun to play in the UK just to see new reactions.

E: In Sweden, it’s not really a big thing to just go to a concert that you don’t know anything about. You only go to bands you already listen to a lot, or if your friends are making music, or some other context. So it’s also fun to play in Stockholm because all our friends are there, but now we’ve done that many times, with not many different people showing up!

The Shacklewell Arms is definitely a venue that people will go to just because they trust that promoters are going to put on good music there.

O: We don’t really have promoter culture in Sweden. That’s a big difference – you do it with the venues. Every venue will have their own sort of promoter, but you still arrange a lot of things yourself. The live industry over here in the UK is a bigger system, and there’s a lot more people involved with it.

To circle back to your single ‘Jesus’, I read that you described that song as being about ‘everything and nothing’. How do you think that idea ties into the religious themes suggested by the song’s title?

E: I think the lyrics are very existential. I don’t know if it means anything when you read them all the way through. I guess you can see many different things in the lyrics.

O: I think it’s fun that you can try and make sense of it all, and maybe you can find something that’s deep and poetic and has that greater meaning, but it doesn’t matter if you just take them as they are. They can be nonsense.

H: I interpret the ‘Jesus’ lyrics as being about everyday life. And if that’s not the most important thing in your life, then you can’t really live with happiness. You need to make everyday life seem holy, because otherwise you’re going to get bored.

O: I think Jesus is a great character to write about, because he can be so meaningful, but to some people he can also have no meaning whatsoever.

E: Maybe it’s also just sending out a question; it’s not me answering anything.

Are there any other Swedish artists that we should be listening to in the UK right now?

H: There’s so many! I can shout out La La Superstar. They’re amazing, we played with them last year. I also really like Sibille Attar.

What can we expect from Clutter in 2025 and going forward?

H: We’re playing our first headline show in London in April. And we’re releasing an EP!

Some records feel like frozen moments in time, kept just as they were made. Others look ahead, outlining what’s to come before it’s even been named. Eterna’s ‘Debunker’, the second album from Barcelona-born, South Londonbased Guillem Peeters, exists in a transitional space between the two. ‘Debunker’ is an album that evolves, pulling at the tension of remembering and forgetting. Melodies dissolve and reform, songs flicker between clarity and distortion, each decision a delicate choice between instinct and obsession. Yet, under all the layers of reverb and grit, there is a quiet, unshakeable honesty - a record that carries the weight of distance, the ache of missing home, the bittersweet realisation of watching family and friends grow from afar.

I think something that really draws me into this record is the production and the way everything sounds. How much of your sound comes from the production part of creating?

I used to make electronic music, so my approach is very hands-on from the beginning. When I record something, I’m already experimenting - mixing it, tweaking it - not to perfection, but to see how far I can push it. For me, I’m actually better at post-production than at traditional guitar playing. So, a lot of my creativity comes from experimenting in that space. It’s what I enjoy the mostit’s one of the areas where I feel most confident. Listening to this album, I think you can hear that - there’s a lot of experimentation in the production, and that was very intentional.

Songs have changed quite drastically from their first demo to the final version. Do you ever miss earlier versions of songs? Have you ever been tempted to release a collection of abandoned or alternate versions?

Yeah, for sure.

There’s songs that were written quite a long time ago, but I’ve taken those chords and moved everything around. When you’re mixing, you’re always soloing different ideas, checking how they work together. At some point, when everything blends well, and the mix feels right, you know you’re done. But then, doing this so many times, I sometimes think, “Maybe the simpler version was actually better?” But that’s also very hard to know because you miss certain things - you can’t ever fully know what the ‘right’ version is. You end up listening to the same song over and over again; it’s important to try to remember what you had in mind and go for that. It’s best not to allow yourself to destroy the song and rebuild it every day. So yeah, I miss the demos, but more in a loving way.

Listening to something over and over again, how many times do you find yourself having to put it away for a second and then come back to it?

Sometimes I measure how much I like an idea based on how long I can work on it without getting tired. If I’ve been at it for four or five hours and I’m still engaged, that’s when I start to think, “Hey, maybe I’m doing something here.” Other times, I’ll play a riff and think, “This is sick!” But then, 20 minutes later, I’m already over it. And that’s when I know that wasn’t it. Sometimes, you’re forcing an idea, and it’s not working.

Have you got any plans to celebrate the album’s release?

Yeah, I’ve got a gig on the 15th of February at Sebright Arms. A band called Sydenham High Road is also playing. And two friends, Braden and Jezmi, are DJing. So yeah, it’s a day in which I shouldn’t be nervous; it should just be fun.

Do you still get nervous a lot before you play?