10 minute read

SUNDAY MARCH

from 20 03 12

LEE DAMUTH

SEAN DUGAN

As Chief Investigator for the 9th Judicial District Attorney's Offi ce, Damuth has had the opportunity to work with Carbondale PD and has always been impressed.

He's also involved in the new antitraffi cking group and is a longtime supporter of Advocate Safehouse.

“I think being familiar with the area and what the town is like and what it expects is my best advantage," he noted.

“I think local politics has a much greater infl uence on people’s daily lives, and I like how involved the citizens are," he added. “It seems like there’s a lot of support for the police department as it is. I don't think it needs any drastic changes."

“I’m looking forward to meeting everybody who can make it out.”

Although much of his experience came in Littleton — he responded to Columbine with a daughter inside — and he now runs the Red Rocks Community College PD, Dugan is familiar with the Roaring Fork Valley. He's particularly fond of Glenwood, while Aspen is a bit too rich for his blood.

“I have a lot of diverse job experience," he noted. “Th ere’s not much that I haven’t seen in law enforcement, and there’s not much that gets me too shook up.”

He likes the idea of settling in someplace quiet and cultivating a great force.

“Th ey say the two most important decisions a chief makes is who they hire and who they promote," he said. “We are the community. We are part of the community. It’s never us against them.”

DAVID SHAFFER

Th e current Deputy Chief of Champaign, IL has family ties in the area and has long hoped to relocate West. He's certain he can make the transition comfortably.

"I've just been waiting for the spot to open so I can apply and be considered," he said.

Shaff er has 30 years of experience in law enforcement and worked as a paramedic before that.

"Your safety is my responsibility, and I would take that very seriously," he said. "I've worked for a larger agency and a smaller agency, and there are pros and cons to both. Th is position opens up the door for more interactions with the community. I want to be the visibible face of the department and for people to feel that they can pick up the phone and call me."

KIRK WILSON

When someone stopped through Rifl e to recruit applicants for the job, Sergeant Wilson's chief pointed him out. He just graduated with a masters in public administration and is always looking to take on a bit more responsibility — as illustrated by his support of the 4H program "My PI," which teaches high schoolers about emergency response in an eff ort to build community resilience.

“I am a relationship builder by nature. "I kind of feel like I can fi t in pretty much anywhere and build trust and rapport pretty quickly," he said. "Th e Police Department is the most visible face of the Town. My goal is to show that the badge is very human. You have some fantastic offi cers there that truly have a vested interest in the community."

CARBONDALE IMMUNIZATION CLINIC

RED HILL ROAD (CR-107) REALIGNMENT PROJECT Recreational Users and General Public Open House

When: March 18, 2020, 4-7p.m. Where: Carbondale Town Hall

is spring, Gar eld County and the Town of Carbondale will be realigning the lower portion of Red Hill Road and moving the parking area. During construction, access to the Red Hill Trail System from Red Hill Road (CR-107) will be closed due to safety concerns. Please stop by Town Hall in Carbondale anytime between 4 and 7p.m. on Wednesday, March 18, 2020, to learn more about the project and the impact to trail access. Representatives from Gar eld County and the Town will be available during the open house to answer questions. and moving the parking area. During between 4 and 7p.m. on Wednesday, March 18, 2020, to learn more about the project and the impact to trail access.

Garfield County Public Health is offering immunizations at The Orchard Church, 110 Snowmass Drive in Carbondale. Appointments are available the second and fourth Wednesday of each month. Please call Garfield County Public Health at 970-945-6614, ext. 2030, to schedule an appointment.

eff ect,” Barnes said. “It’s prey animals’ primary anti-predator behavior.”

Cattle — indeed, all kinds of prey — can move the weakest members of the herd to the middle, and defend themselves using their hooves.

Miranda, who raises water buff aloes, thinks his animals stand a pretty good chance against wolves because of their herding behavior.

“I know that the water buff aloes that I have are probably going to have a better instinct protecting themselves and the younger animals as far as protecting themselves against a pack of wolves,” Miranda said.

But Perry and Fales say the landscape where their cattle graze make herding up very diffi cult. Th ere aren’t many open fi elds on the Forest Service land where their permit is, and there’s also limited access to water.

“We try to not have the cattle in a big bunch in order not to hammer the riparian areas,” Perry said. “Our whole strategy has been to keep cattle strung out. And so far, it seems like it’ll be really hard to remedy that.”

Wolf advocates also say range riders can help minimize losses; a rider who is out with the cattle daily can watch for injured or weakened cows or calves that might become targets and keep an eye out for wolves. But Fales doesn’t think that would work, either, especially with the challenges of fi nding reliable labor. “We do a lot of range riding. Th ere’s never a day when there’s not someone out there,” he said. “But Wolves fr om page 3

it would be totally insuffi cient to manage for wolves.”

Th e management strategy that Perry and Fales think would work in their situation is one that currently isn’t an option in Colorado: killing the problem wolves that prey on cattle.

“Th e only thing I would really advocate for would be lethal control,” Perry said. “You can’t have wolves without forevermore killing them.”

Killing wolves is illegal in Colorado because the species has federal protection under the ESA, but the future of that status is uncertain. Some ranchers, including Miranda, are hopeful that reintroduction would mean a larger voice in how wolves are managed than if the animals return to the state on their own.

“Some of these programs are very progressive,” Miranda said. “As long as there’s that kind of help and communication, that’s very fortunate.” In fact, the CSU survey found that nearly 80 percent of people who identify as ranchers intend to vote for reintroduction. Th at number, according to Niemiec, includes people who self-identify as ranchers “a slight amount” (124 respondents), “a moderate amount” (111 respondents), or “a great deal” (74 respondents), and so may include people who identify with a ranching lifestyle but are not currently in the business.

Th e online survey asked respondents a series of questions about how offi cials could manage wolves — including lethal control and compensation for ranchers for lost livestock — before asking whether people support the ballot initiative.

Th e initiative does not include any promise of lethal control, and management depends on a series of questions — namely, if wolves are removed from protections under the ESA. Even then, Barnes said control measures need to be carefully executed. “For lethal control to make sense, it’s got to be targeted to the specifi c individuals that are involved in the confl ict,” Barnes said. “Preemptive lethal control does not work.”

Also, he said, the number of cattle and sheep actually killed by wolves in states such as Montana and Wyoming is surprisingly low.

Wolves kill few cattle, sheep

In Montana in 2018, the U.S. Department of Agriculture confi rmed the loss of 71 livestock — 64 cattle and seven sheep — and two dogs to wolves. Th e USDA received 93 complaints of wolves killing livestock that year, while the state was home to an estimated 2.55 million cattle, 225,000 sheep and 819 wolves.

Th e numbers are similar in Wyoming, where wolves are considered “predatory animals” in most of the state, meaning they can be killed at will. In 2018, wolves were confi rmed to have killed 71 head of livestock: 55 cattle, 15 sheep and 1 horse.

Wolves do kill livestock but not in big numbers.

“Th e rhetoric, the exaggeration, the myth is our biggest challenge,” Malone said. She said wolf advocates have work to do to assure ranchers that wolves won’t devastate their livelihood.

“We need to do work with the ranching community to be sure that they are whole and that they’re fairly treated,” Malone said. “But we can do that. We have good examples of it.”

Initiative 107 includes direction for the Colorado Parks and Wildlife Commission to create a plan to compensate for livestock lost to wolves. Similar plans exist in other Western states, including Montana, where the state paid $82,959 to 40 livestock owners.

Funding for such a program in Colorado would come from an existing wildlife cash fund, and Malone says the goal is for public input to help shape policy on how to fairly compensate ranchers for their losses.

Still, Fales and Perry worry that wolves in Colorado would mean a signifi cant economic hit — and an emotional one, too.

“Th ere’s an emotional attachment (to the cattle), even though you’re selling them for a beef animal. You’re taking care of them, we’re with them just night and day when they’re calving,” Perry said. “And to go out and fi nd them just shredded and eaten up is not something I would ever vote for.” If Initiative 107 passes, Perry says she might quit. And her husband, Fales, thinks others might follow suit. “I think a lot of people will quit, and certainly in this part of Colorado, there are a zillion developers ready to help you quit,” he said.

Historically, confl icts between ranchers and wolves have not ended well for the predators. “Because of their depredations of domestic animals, wolves in Colorado were systematically eradicated by shooting, trapping and poisoning,” reads the CPW informational website on wolves.

In recent years, CPW offi cials say there have been no reports or evidence of people killing wolves in the state, except for a widely publicized incident in 2015 where a hunter shot a wolf that he said he thought was a coyote.

While wolf advocates point to the ecological benefi ts of restoring wolves to their historic range, the social implications might be harder to pin down. Perry says she understands why people might be attracted to the idea of wolves, but she believes the implications on the ranching industry will be far-reaching.

“Th ere could be unintended consequences (of wolf reintroduction),” Perry said. “Loss of ranchland, which means more fragmentation, more housing development, more decline for all animals, prey and predator.”

Barnes, who has experience in both wildlife conservation and raising livestock, says part of having domestic animals is the risk of predators.

“Very little in nature gets to live out its life without the risk of getting eaten,” Barnes said. “Coexistence is possible, but it’s probably not peaceful.”

Your Story, Digitized Your Story,

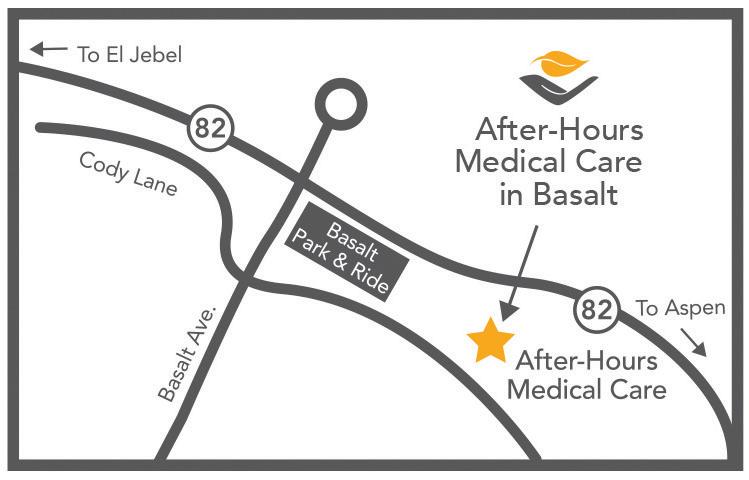

After-Hours Medical Care in Basalt

Craft your online narrative

Cool Brick Studios world-class multimedia studio

Beautiful Website Design

Effective Email Campaigns

Best in Social Media Tactics

Compelling Search Marketing

photography • film • video 360° virtual tours

When you have unexpected medical needs, we are here for you. No appointments necessary. Walk-ins welcome!

Monday – Friday 3:00 – 11:00 pm Saturday & Sunday 8:00 am – 5:00 pm NEW, EXTENDED HOURS!

Audio and visual excellence all under one roof!