Welcome to the third edition of STAHS German magazine Der Wendepunkt, Der Wendepunkt is created by students Year 10 to 12 Instead of emphasising linguistic knowledge, our focus lies in exploring cultural aspects, particularly topics related to German culture and history In this edition, 'Melting Pot Germany', we will delve into the multicultural society of present-day Germany.

Our aim is to showcase the vibrant diversity within German society, from an insightful discussion on the essence of German culture to a poem on the delicious flavours of a Döner kebab and the guest workers that brought it with them

You will have the opportunity to explore Jewish life in modern Germany, learn about the inspiring political figure and role model Aminata Touré, and get to learn about the fascinating linguistic phenomenon of Kiezdeutsch

Furthermore, we will shed light on the unfortunate reality of xenophobia in Germany, using the example of Mesut Özil, a German footballer.

We sincerely hope you enjoy this issue of Der Wendepunkt!

It is a clear fact that people want to feel like they belong, whether that be to their country, village, place of work, or even just family The world is overflowing with different cultures and ways of life that people use as a way of identity. However, culture can sometimes be used to exclude people from places, for example immigrants who have moved to a new country, as some people have a firm definition in their mind of what belongs and what doesn’t, causing divisions and frictions in society.

In Germany, the term Leitkultur or “leading culture” is consistently used when discussing immigrant policy, particularly amongst rig politicians, for example the AfD (Alternative für Deutschland). The term a debate around it became mainstream start of the millennium, when it was launc CDU member (Christian Democratic Friedrich Merz. The term was originally the agricultural sector, describing the ma types in an environment Merz believe immigrants moving to Germany should c to the “German culture” by using the la and following the constitution and key va the German people, such as equality – quite ironically

by Mattie Thomas

by Mattie Thomas

This rejection of multiculturalism caused divide in politics, with some politicians labelling Merz’s ideas as extremist ideology Furthermore, many politicians critisised the debate around Leitkultur as it distracts from more important matters, such as poverty, violence and crime.

During the 2017 elections, the term was revived by CDU politician Thomas de Maiziere, who compiled a list of 10 points for the tabloid “Bild” depicting what Leitkultur meant and what it stood for Some points included good work ethic, respect for others and being a strong patriot for Germany. However, he received backlash for points such as ‘showing your face’, a dig against Muslim women who choose to wear the full-face covering, called Niqab Furthermore, he claimed that ‘Germans should greet each other by shaking hands’, another dig at religious minorities that don’t touch members of the opposite sex outside of family People on social media created their own list in retaliation, listing things stereotypically German in order to mock de Maiziere, including wearing socks with sandals, and Bratwurst, a typical German sausage dish

The controversy surrounding Leitkultur also has another layer Following the horrors of the Nazi regime and the Second World War, patriotism was destroyed for many along with the idea of what it is to be German. It wasn’t until 2006 when Germany hosted the FIFA world cup that flying German flags prompted no negative connotations, more than 60 years after the end of World War II. But despite this shunning of patriotism, some Germans are yet to embrace a multicultural society, despite one fifth of Germans having a migrant background

I asked my German exchange partner for their opinion on Leitkultur and they said it was “difficult to say what it meant to be German,” and that they could “only think of clichés.” They also brought up the impact of World War II, and mentioned how the younger German generation consider it their duty to make Germany a welcoming place and condemn racism in allforms Overall, many Germans are still uneasy about the question “what does it mean to be German?” and often go with stereotypical, slightly comical answers, such as “drinking beer,” “Bratwurst” or “bread.” This identity crisis is not unique to Germany; many countries use big, stereotypical ideas in order to define themselves and link themselves to where they are from However, belonging to a place and what it means to be part of something is often on a much smaller scale than people realise

When I went to Germany over the Easter holiday to stay with my exchange partner, I encountered many things that were part of the German culture on many different levels. People rode their bikes everywhere, and teachers wore jeans and t-shirts to school With school finishing early in the afternoon, many teenagers went to hang out with their friends multiple days a week They were also very jealous of the fact I don’t have to do maths anymore, as they have to continue studying certain subjects up until they leave school There were so many things that were so different to the UK, which in my opinion, create what it means to be German and what it means to grow up in Germany.

My exchange partner also argued that Germany doesn’t have its own Leitkultur and is instead made up of lots of different parts. For example, in the 1980s, a large influx of Turkish people moved to Germany as part of the guest-worker programme, and the Turkish culture still has a major impact in Germany today The mix of multiple different countries and influences has created a new culture unique to Germany, one that is ever changing and growing Culture can be seen as a broad picture, but should also be seen on a smaller scale in the everyday lives of those who live in Germany, regardless of whether their families have lived there for centuries or if they are newly arrived immigrants Culture means something different for everyone, and should be celebrated in all of its different forms, since it is such diversity that shapes the whole picture of a country and the people in it.

In the mid-1950s, Germany desperately needed workers to fulfil labour demands in factories and mines after World War II. This was because over 4 million Germans died in the war and there were not enough workers from Germany alone to rebuild its economy Therefore, foreign skilled workers were sought after and many people in need of jobs moved to West Germany, along with their families, in search of financial stability.

Initially, Gastarbeiter were supposed to be a temporary fix to Germany’s lack of workers, with short-lasting contracts and treaties regarding only Germany and its European counterparts. However, soon, multiple micro-societies were formed – most of which had some trouble integrating into the rest of Western Germany In 1955, Germany and Italy entered a tr Spain closely following suit and in largest group of Gastarbeiter, th confirmed a treaty on October 30th

In the beginning, the contracts of Ga were supposed to be limited to t maximum However, in 1964, the tr amended to allow Turkish workers to much longer periods of time Additona allowed for their families to stay w leading to the micro-societies, which shaped Germany’s cultural identity an the multifaceted country it is today

Literal Translation:

Refers to the foreign or migrant workers who moved mostly to West Germany (1955-1973) in search of work

Döner kebabs are a Turkish dish – highly popular in Germany. With 600 tonnes of Döner meat consumed per day, it’s safe to say that Döner kebabs are a favourite late-night snack for many

The Döner kebab was created by a Turkish Gastarbeiter, Kadir Nurman, in Berlin in 1972

Turkish people are the largest ethnic group of non-German citizens living in Germany, and Kadir Nurman emigrated from Turkey to Germany alongside many others in 1960 to be a part of Germany’s growing work force.

Döner kebabs are made up of meat skewers, vegetables, and a delicious sauce, wrapped up in a Turkish flatbread - YUM!

From Istanbul all the way to Berlin, delicacy of a new-found cuisine. Flavourful meat going round in a spin

A fuse no one could have foreseen

Oh Döner kebab how rich and divine, Your aroma fills the air, so fine.

My longing for you never ending to my every need you are tending

Oh, delicious kebab, how I adore thee!

With your savoury meat and flavours so free; Spiced meat, grilled to perfection, Topped with veggies, a true reflection of flavours from the Middle East, a culinary delight, a feast.

Oh Döner kebab, you are my go-to

My taste buds dance, with every chew

I cannot resist your delicious charm!

Your beauty causes my heart to warm

For you are not just food, but a cultural treasure, a symbol of diversity beyond measure.

by Isabel Gokcek

by Isabel Gokcek

Holocaust, whilst others had actively immigrated to the country Nevertheless, several thousands of Jews qualified for German citizenship and therefore rekindled Germany’s dwindling Jewish community.

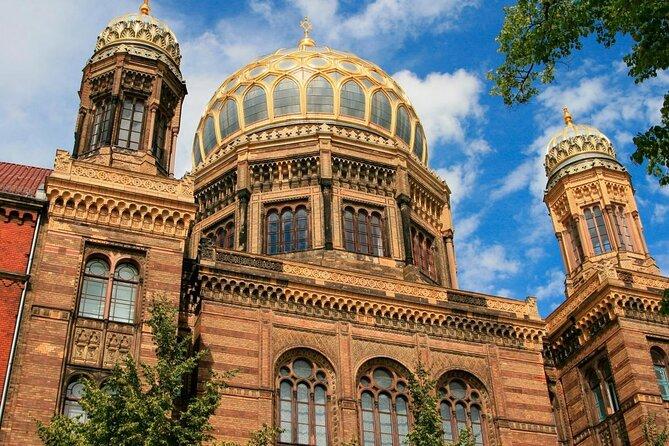

Prior to the Second World War, in 1933, approximately 565,000 Jews resided in Germany. By the 1950s, merely 37,000 were left, as the vast majority had been massacred by the Nazi powers. Almost a century later, Germany’s Jewish population is rapidly growing, with over 200,000 estimated to be living in the country as of 2023. Although the prospect of reviving a Jewish community in Germany seemed to be unthinkable after the events of the Holocaust to both Jewish and non-Jewish Germans, there are many communities present within the country today, all with the freedom to exercise their religious and cultural beliefs.

In an attempt to rekindle German-Jewish relations, Germany’s post-war government passed a law that anyone with at least one Jewish parent from the Soviet Union would qualify for German citizenship, thus receiving an influx of Jews seeking to resettle in their country However, the vast majority of these Jewish immigrants did not trace back any of their roots to Germany but instead were mostly of Eastern European descent Some of these Jews had found themselves unwillingly in Eastern Germany, formerly known as the GDR, after the

It is currently estimated that roughly 90% of the country’s Jewish population is of Eastern European descent. By the time Germany had changed its laws on immigration, approximately 200,000 Jews had already resettled in the country Despite the rapid increase in their numbers, the different Jewish communities clashed with one another, namely in terms of culture and assimilation into Germany. Whilst the Jews of German descent were already very well integrated in the country through having multiple connections with non-Jews and other German citizens, the other Eastern European Jewish communities found it significantly more difficult to adapt to the German way of life

Moreover, the majority of the Jewish immigrants from the East of Europe considered themselves to be secular, thus clashing with the many traditional Jewish communities already established in Germany However, with the help of the German government and their funding, these Jewish immigrants were supported in terms of integrating within the country and exercising their right to practice their culture and beliefs in the German society

Today, Germany has one of the most rapidly growing Jewish communities in the world, with many more Jews from other countries such as Canada, the United States and Argentina, wishing to immigrate to Germany and resettle there Additionally, many campaigns have been established in attempts to familiarise Germans with German-Jewish citizens in their country and to no longer see them as victims of war but instead to bring attention to their culture and way of life.

Although the German-Jewish relations seem to, overall, be very promising for the future, there have also been cases of anti-Semitic behaviour in the country. In 2019, a German man was arrested for carrying out an attempted attack on a synagogue in the East german city of Halle. After unsuccessfully trying to break into the building, the man proceeded to shoot two civilians, namely a woman on the streets and a shop owner This attack occurred on ‘Yom Kippur’, the holiest day of the Jewish calendar. Other anti-Semitic behaviour includes the resurgence of Nazi and far-right beliefs in the country, with neo-Nazi groups using the internet to spread messages of racism and hate which targets the Jewish communities in Germany

However, despite the anti-Semitic beliefs of the German far-right , the newer German-Jewish population seems much more willing to fight for Jewish rights publicly, no longer hidden behind closed doors Furthermore, the increasing efforts to help integrate Jews into the German population by the country’s government can be seen as a big step forward to help reconnect themselves with the Jewish citizens, thus improving the German-Jewish relations after the events of the Holocaust during the Second World War.

by Aanya

by Aanya

youth, LGBTQ+ rights and anti-racism policies. These desires of hers are clearly cited in her memoir “Wir können mehr sein: die Macht der Vielfalt” (“We can be more: the power of diversity”) which was published in 2021 and outlines the story of her life and policies so far.

Touré’s two greatest concerns that her party, Bündnis 90 Die Grünen (Alliance 90/The Greens), tries to address are immigration and the climate crisis. Touré has called frequently for a "European solution" to issues surrounding asylum and faster integration of refugees into Germany

Aminata Touré is truly a powerhouse in German politics At age 30, she is already the first Black minister in the German Parliament, the youngest minister of Germany’s northernmost state, Schleswig-Holstein, and is pushing this Bundesland into a more sustainable future Born in 1992 in the German town of Neumünster, Aminata Touré is the child of two Malian refugees who fled Mali in 1991 following the coup d’etat there. She describes herself as Afrodeutsche (Afro-German), a term coined by the Black feminist movement in Germany, and feels very connected to her roots but also the country she grew up in.

Being the child of refugees, Aminata spent the first 5 years of her life in a refugee camp, only becoming a German citizen at age 12. It is this unique and personal insight into many deep rooted social issues that gives Touré a special political power to represent other migrants and highlight some of Germany’s social issues with which she personally identifies and sympathises. Within her state seat in Schleswig-Holstein, she has already spoken up about migration, equality,

"We must unlearn racism I expect non-black people to listen to us and show solidarity."

Apte

"Wir müssen Rassismus entlernen Ich erwarte von nicht-schwarzen Menschen, uns zuzuhören und sich zu solidarisieren."

She has also addressed her concern for the environment in 2017 through her climate policy, stating that she was not concerned with lifestyle issues, but with global poverty reduction

In 2022, Touré became the Vice-President vice president of the Landtag, local state government, and in doing so became the first Afro-German and the youngest person to ever to take up a position at a federal level

Aminata Touré also strives to be a role-model for young people of colour in Germany, who have very few role models to look up to She remembers an election campaign in which a four-year-old black girl waved at her - Touré recalls this moment as the moment she knew how important her image in the public eye was: as a minister, an immigrant and a woman

by Arshya Bommaraju

by Arshya Bommaraju

Germany, a nation rich in culture and historical heritage, has evolved into a captivating melting pot where diverse ethnicities and languages intermingle. Amidst this vibrant multicultural landscape, a remarkable linguistic phenomenon has taken root, giving rise to an intriguing array of dialects and ethnolects, a dialect which is specific to one or more ethnic group(s). As people from various backgrounds merge their languages and cultures with the German fabric, a tapestry of unique language varieties is woven, transforming communication patterns and fostering a deeper understanding of cultural identities.

A prominent example of this cultural and linguistic evolution is Kiezdeutsch, or "neighbourhood German," a distinctive variety of the German language predominantly used by youth in urban areas with high proportions of immigrants The term originated in Kreuzberg, a district in Berlin, and is prevalent in other areas, such as Wedding. The origins of Kiezdeutsch can be traced back to the immigration waves of the 1960s and 1970s, when many Turkish and Arab migrants arrived in Germany as Gastarbeiter (guest workers). These immigrants settled in urban areas, forming their own communities within the larger German society Over time, a distinct linguistic variety began to develop amongst these communities as a result of language contact and the bilingual upbringing of second-generation immigrants. The classification of Kiezdeutsch has sparked debate among linguists Some consider it a dialect, due to its use in specific areas with high immigrant populations, whilst others argue it falls under the categories of ethnolect or multiethnolectal German youth language, as it is

used primarily used amongst urban youth and is influenced by multiple heritage languages As well as including a variety of grammatical and syntactical differences, Kiezdeutsch is heavily characterised by its incorporation of foreign words from languages such as Turkish and Arabic, but also American English These loan words are used following the rules of German grammar and their pronunciation is Germanised, creating a unique solution for migrants to culturally assimilate whilst preserving their heritage Examples of adopted terms include "yalla," meaning "let's go, " and "lan," meaning "dude," which originate from Arabic and Turkish

However, Kiezdeutsch has often been portrayed negatively in popular media. It is depicted as corrupting the German language and associated with poorly integrated immigrants who have not mastered German effectively Films and television programs often portray Kiezdeutsch speakers as uneducated and unruly. One example is the comedy duo Erkan and Stefan, who derisively used an artificial dialect combining Turkish and Bavarian accents infused with English slang, reminiscent of Britain's Ali G.

Critics also argue that Kiezdeutsch is a lazy or uneducated dialect due to its tendency towards grammatical simplification For instance, particles and prepositions are frequently omitted, especially when the context is clear. Instead of saying "Ich gehe in die Schule" (I go to school), speakers might simply say "Ich gehe Schule" (I go school)

However, linguists assert that such criticism of Kiezdeutsch as detrimental to the German language reflects social issues of racism, xenophobia, and other such negative attitudes towards migrant groups, rather than inherent linguistic deficiencies. Is the ethnolect any more corrosive than the variation of German spoken by young ethnic Germans, who seamlessly adopt English words they consider to be cool? Moreover, linguistic evolution naturally tends towards simplification as native speakers abbreviate and omit longer grammatical structures for ease Thus, linguists argue that Kiezdeutsch, far from causing long-term damage to German, should be viewed as an innovative expansion of Hochdeutsch (Standard German)

The linguistic influence of Gastarbeiter is further highlighted by the use of Gastarbeiterdeutsch and Türkendeutsch in Germany. Gastarbeiterdeutsch is a German pidgin (a language variety that has developed from a mixture of two or more languages, used as a way of communicating by people who do not speak each other's languages), which emerged in the 1960s with the influx of Gastarbeiter into Germany It was mainly spoken by the first generation of foreign workers from Southern Europe, North Africa, and later, Turkey, and was used by these newcomers to communicate with their employers and German workers The use of Gastarbeiterdeutsch is limited to this first generation of immigrants, as subsequent generations of immigrants attended the German public-school systems and thus grew up bilingually

Meanwhile, Türkendeutsch is an alteration of the German language whereby Turkish sounds and lexical features are mixed into the grammatical structure of German. An example of this unique linguistic fusion can be shown through the following sentence: ’Thomas I simdi bi vergessen et fuer ne zeitlang ‘ (English: ’Well, just forget Thomas for a while’ )

The sentence structure is German, but the lexicon is mixed; the words in italic belong to the Turkish language, whilst the words in nonitalic belong to German Unlike with Gastarbeiterdeutsch, some Turks belonging to the second or even third generation of ‘Gastarbeiter’ continue to deliberately utilise this mix of Turkish and German, albeit only in private settings, to express their connection to both cultures. Sadly, however, both Gastarbeiterdeutsch and Türkendeutsch are highly stigmatized and connected to the stereotyping of immigrants, similarly to many other pidgins and ethnolects (as shown by Kiezdeutsch).

Gastarbeiter, however, whilst highly linguistically influential, were not the only source of varieties of German. There are also dialects such as Pommersch, a fascinating linguistic phenomenon which combines elements of both German and Polish, which originated in the border region historically known as Pomerania, encompassing parts of modern-day Germany and Poland. The vocabulary of Pommersch draws from German and Polish words,

incorporating terms from various domains such as everyday life, agriculture, food, and folklore It is not uncommon for Pommersch speakers to seamlessly switch between German and Polish vocabulary within the same conversation; a linguistic phenomenon known as 'code-switching'. This fluidity and adaptability make Pommersch an expressive and versatile language

Overall, the role of immigrants and multiculturalism in enriching the German language can be clearly seen through the vast array of language variations they have given rise to. However, these variations are unfortunately viewed with negative attitudes, and are often used by those with racist, xenophobic, or Islamophobic mindsets to deride or stereotype their speakers Moreover, there are challenges to the preservation of these forms of German Increased mobility, globalization, and the dominance of standard German pose a threat to minority language and dialects, endangering the diversity of Germany’s rich linguistic landscape. Efforts to raise awareness, document dialects, and promote their use in various media can contribute to the preservation and destigmatisation of such significant cultural markers.

Unlike the others, Özil took two months to address this scandal, during which time the defending champions Germany had left the World Cup at the group stage. Özil then became the main scapegoat for the disappointing performance at the World Cup, which exposed deeply rooted tensions surrounding issues of identity, integration and national allegiance.

Mesut Özil, born and raised in Gelsenkirchen, Germany, as the grandson of a Turkish guest worker was one of Germany’s most successful footballers in the 2010s He has played for teams such as Real Madrid and Arsenal and became the most expensive German player in 2013, when signing for Arsenal. In 2006 he renounced his Turkish passport and became a German citizen in order to be able to the national youth team Özil was a ke for Germany’s football team in the 201 Cup (where Germany came 3rd), as we 2014 World Cup which Germany won. H in 2018 he stopped international following a controversial photoshoot wit President Erdogan.

n 2018, three footballers born in Germa Turkish descent, Mesut Özil, Ilkay Gündo Cenk Tosun, all met with Turkish Presiden Tayyip Erdogan in London for a photosh seemingly innocent act quickly ign firestorm of controversy with the Germa and public highly criticising the politicians alleged human rights vi Gündogan and Özil were particularly criticised, as they were both German internationals.

During this time, the DFB (German Football Association) exacerbated the issue A decision was made to keep Özil on the national team for the World Cup, yet following their surprise early exit, they increasingly focused on the photoshoot with Erdogan "Therefore, it is not good that our national team players were misused as part of election campaign manoeuvre.

With this move, the two players certainly did not further our work on the issue of integration." said DFB President Reinhard Grindel. In a climate were people openly questioned Özil’s dual identity as a Turkish-German individual and even his loyalty to Germany as a whole, the DFB’s lack of support only further intensified the controversy.

The DFB has since apologised for the way it managed the situation: "Regarding the racist attacks, I could have taken a clearer position at some points and stood by Mesut Özil" Comparisons were also made between former Germany skipper Lothar Mätthaus and Özil. Matthäus, who was photographed shaking hands with Vladimir Putin, suffered not consequences, with no reaction from the DFB, press and public, partly revealing the xenophobic undertones of the media and public reaction.

Mesut Özil responded to the criticism on twitter on July 22nd, 2018, in his scathing address of the response he received, he detailed the racism he has faced, criticism of the DFB and his decision to retire from international football: "I am a German when we win, but an immigrant when we lose " He believed that the photoshoot was not political, but rather respecting the highest office of Turkey.

Following the lack of support for Özil, there has been increased attention placed on the lack of diversity and acceptance within German football. For example, as of March 2020, the DFB's executive board includes eighteen men and only one female member In the most recent World Cup in Qatar, the FA banned the German team from wearing ‘One Love’ armbands and covered their mouths prior to their match in protest In response, the Qatari fans showed photos of Mesut Özil in order to express the hypocrisy of the German public. The dual nature of German football is exposed through the treatment of Mesut Özil; the apparent support for diversity which was then shown to be lacking when it was indeed needed

‘I am a German when we win; an immigrant when we lose.’

„Wenn wir gewinnen, bin ich Deutscher; wenn wir verlieren, bin ich Immigrant“.The first part of Özil's statement in English.

Thank you to everyone that participated in this issue of Der Wendepunkt!

A special thank you goes out to the exceptional Wendepunkt journalists whose dedication crafted a wonderful edition full of vibrant and captivating articles.

Your remarkable efforts have truly made a difference. Thank you for your invaluable contributions.

If you are interested in joining der Wendepunkt-team, don't hesitate to come along to a meeting. You simply need an interest in German culture.

Amina Kacimi (German assistant) - Writer, Editor, Design

Frau Rachel Gupta - Editor

Aanya Apte (Y10) - Writer

Arshya Bommaraju (Y12) - Writer

Charlotte Chapman (Y12) - Writer

Ella Newton-Smith (Y10) - Writer

Isabel Gokcek (Y12) - Writer

Mattie Thomas (Y12) - Writer

"Ourcolourfulrepublicof Germany"

Christian Wulff, Berlin, July 2nd 2010

St Albans High School for Girls

Townsend Avenue, St Albans, Hertfordshire AL1 3SJ

info@stahs.org.uk

stahs.org.uk