SPRING / SUMMER 2021

ATRIUM THE ST PAUL’S SCHOOL ALUMNI MAGAZINE

George Amponsah is one of the creative Paulines ‘In Conversation’ with Jon Blair Need for a Reset

An Unconventional Pauline

Pauline Perspective

Ed Vaizey discusses how to fund the Arts

Michael Simmons reveals Martin Bradley

Tim Hardy on a Life in Theatre

Editorial French horn players rarely reach the star status of a violinist, pianist, cellist or conductor, but by the time of his tragically early death in a car accident at the age of thirty-six, Dennis Brain (1934-36) had established himself as one of the greatest French horn players and musicians of the twentieth century. It is his centenary this year. Paulines should celebrate him.

S

t Paul’s is often viewed as an academic hot house that through weight of numbers and facilities produces some excellent sports players, teams and crews. It is more than that and Dennis Brain is only one example of the exceptional creative talent nurtured at School. This magazine is unashamedly creative heavy and includes articles on war and Bloomsbury Set artists Paul Nash (1903-06) and Duncan Grant (1899-1902), as well as jazz musician Chris Barber (1946-47) and artist Martin Bradley (1946-47). Jon Blair’s (1967-69) cover article focuses on 10 Paulines who currently bestride the creative world. The Old Pauline Club’s next President Ed Vaizey (1981-85) also lifts the lid on his time as Culture Secretary to share his thoughts on Arts funding after a truly disastrous twelve months for the industry.

keep our community together by taking the events programme online. My highlight has been the only ever online Feast Service. School Chaplain, The Rev. Matthew Knox led the service that included the OPC President, the High Master, the Captain of School, the Chairman of Governors and OP clergy. It truly fulfilled the aspiration of the Pauline Community working together. I must add with much gratitude my appreciation of the work of all Atrium’s contributors (listed on Page 02) and the support I have again received from Kate East, Jessica Silvester, Hilary Cummings, Ginny Dawe-Woodings and Viera Ghods. Jeremy Withers Green (1975-80) jeremy.withersgreen@gmail.com

Bringing the Pauline Community together is our aspiration. So you can imagine my delight when late last year an email came in from Tim Hardy (1954-59), “I was the 'Scalchi' mentioned in Robin Hirsch's (1956-61) article in Atrium. I say 'was', because when finishing my training at RADA I was advised to adopt an English name. We were not so multi-cultural then.” Robin and Tim are back in touch after 60 years. Tim has written ‘A Life with The Bard’ alongside Robin’s ‘Leading Cadet Hirsch’; both richly colourful contributions. The School’s Development and Engagement team has done a wonderful job helping to

Cover photo: George Amponsah: photo by Paul Marc Mitchell Design: haime-butler.com Print: Lavenham Press

CONTENTS

18

28

26

03 Letters OPs comment on Sid Pask, Tom Howarth and Atrium

06 Pauline Letter Patrick Neate writes from Zimbabwe

08 Briefings Including Pauline Pews, Protestor and Poetry

18 ‘In Conversation’ with Creative Paulines: Jon Blair interviews

26 Martin Bradley Michael Simmons profiles an Unconventional Pauline

28 Paul Nash and Duncan Grant David Roodyn portrays the Pauline artists

30 Chris Barber Simon Bishop profiles the jazz and blues musician who loved motor racing

38

60

32 The Founding of the National Youth Theatre Michael Oliver describes his contribution

34 On The Hunt for Purpose-driven Unicorns Tommy Stadlen and Cameron McLain talk to Simon Lovick

36 Arts Funding Ed Vaizey suggests a post COVID reset

38 Shakespeare Has It Covered Tim Hardy describes a theatrical life

42 Et Cetera Robin Hirsch’s take on Monty Inspecting the Cadet Force

44 A Pauline About Town

52 Old Pauline Club News Brian Jones on Governance, the Archives and the Feast

54 Obituaries Including Basil Moss, former Old Pauline Club President

57 Old Pauline Club OP sport is set to resume this summer

58 Old Pauline Sport Old Pauline Football: A successful season cut short

60 Past Times Pauline Board 5 beats Grandmaster

61 Pauline Relatives The Elder Neates

63 Crossword

Rohan McWilliam on London’s West End

Lorie Church sets the puzzle

46 Bursary and Development Update

64 Last Word Ralph Varcoe on lessons learnt after leaving

Ellie Sleeman and Ali Summers report 01

ATRIUM CONTRIBUTORS

Listed below are those who contributed to the magazine. Ellie Sleeman is Director of Development and Communications at St Paul’s. She has worked in fundraising, marketing and crisis management since graduating from UCL, joining St Paul’s from Wellington College following an eight year stint as a Director at London’s Roundhouse. Michael Oliver (1946-47) first practised in London as a solicitor. He helped Michael Croft to found the Youth Theatre – later The National Youth Theatre – becoming its chairman. He was elected to the board of The National Theatre and assisted with the development of the British Academy of Film and Television Arts and was a founder of it in the USA where he practised State and Federal law. After ten years in the USA he returned to London before retiring to live permanently in Italy. Michael Simmons (1946-52) read Classics and Law at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. He qualified as a solicitor and after two years as an officer in the RAF practised Law in the City and Central London for fifty years. Since retiring, he has pursued a new career as a writer. Michael is in touch regularly with seven other members of the Upper VIII of 1952. Robin Wootton (1951-55) read zoology at University College London and continued there to a PhD in palaeoentomology. He taught for four decades at the University of Exeter and pioneered an engineering approach to insect wing design, now a hot topic in the development of tiny drones. He is still an honorary research fellow with continuing interests in insect flight mechanics, all kinds of folding structures, and C19th Devonians. Tim Hardy (1954-59) has had a stage career that has taken him from Peter Brook’s Marat/Sade for the RSC in London and New York, to the West End and Royal Court, to theatres all over the UK, and on extensive tours here and abroad of the one-man Trials of Galileo. He has played in Shakespeare all over the USA, in Vaclav Havel for the Hong Kong Festival, and in Peter Hall’s Lysistrata in Athens and London. He played Perchik in Fiddler on the Roof and all the lead bass operatic roles for Music Theatre London. His television work has ranged from Michael Gambon’s Oscar Wilde to Eastenders to Casualty 1909, while on film he has played Jesus (for US TV) and a fellow officer in Captain Corelli’s Mandolin. He has directed in Vienna, in Frankfurt, at many American universities, and regularly at RADA, specialising in Shakespeare. He also serves on RADA’s Admissions panel. Robin Hirsch (1956-61) is an Oxford, Fulbright and English-Speaking Union 02

ATRIUM

SPRING / SUMMER 2021

Scholar, who has taught, published, acted, directed and produced theatre on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1977 together with two other starving artists, he founded the Cornelia Street Cafe in New York’s Greenwich Village. In 1987 the City of New York proclaimed it “a culinary as well as a cultural landmark.” Cornelia Street Cafe is now ‘in exile’ having been forced to close by vile landlords.

Alistair Summers (1978-83) was a Governor at St Paul’s from 2007 until 2019 and Deputy Chair from 2014 until he retired from the Governing Body. Throughout his tenure he sat on the Governors’ Finance Committee. After St Paul’s, he went to LSE and then qualified as a Chartered Accountant with PricewaterhouseCoopers. Since 1992, he has been in private practice.

Simon Bishop (1962-65) is a former editor of Atrium. He has worked in publishing for most of his professional life including as art editor for Time Out magazine and for BBC Wildlife magazine.

Ed Vaizey (1981-85) read Modern History at Merton College Oxford. He was Member of Parliament for Wantage 2005-19 and served as Minister for Culture 2010-2016. He became Lord Vaizey of Didcot in 2020. In July this year he will take over as President of the Old Pauline Club.

Jon Blair CBE (1967-1969) was born in South Africa and was drafted into the South African army in 1966 but chose instead to flee to England entering St Paul's in January 1967. He has worked across the creative world winning four of the premier awards in his field: an Oscar, an Emmy (twice), a Grammy and a Bafta. He was appointed CBE in 2015 for services to film. Jon has also been awarded an honorary doctorate by Stockton University in the USA for his contribution to human rights awareness through his film-making work. In 1999 he endowed the Blair Prize at St Paul’s to be given to a student who has shown “outstanding cross curricular creativity” in his work or any other activity during the year. David Roodyn (1967-1971) after retirement moved to Brighton but spends time in the South Of France. His 65th birthday celebration at the Colombe d’Or, St Paul de Vence was attended by his Pauline friends Peter Fineman (1966-71) and David Soskin (1967-71). Sir Lloyd Dorfman (1965-70) expressed apologies for his absence. Luke Hughes (1969-74) was awarded an open history scholarship to Peterhouse, Cambridge and studied History of Architecture for Part II. He has since specialised in designing for public buildings. Clients include Harvard, Yale, more than 85% of Oxbridge colleges and 24 cathedrals. He also designed the library and court furniture for the UK Supreme Court, and the clergy furniture for Westminster Abbey, first used for the Papal visit in 2010 and the Royal Wedding in 2011. Rohan McWilliam (1973-78) is Professor of History at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge. He read History at the University of Sussex and is a former President of the British Association for Victorian Studies. His new book, London's West End, is the first ever history of the pleasure district that has been written. He has written on Victorian popular politics and the modern Labour Party. In addition, he contributes to the press on current affairs.

Patrick Neate (1984-1989) is an author and screenwriter. His latest novel is called Small Town Hero, published by Andersen. It is about football and quantum mechanics. He would like to take this opportunity to apologise to numerous Old Paulines for the unacknowledged appropriation of names, noses, complexions, haircuts, disco dancing skills and more in his fiction. Ralph Varcoe (1984-89) studied music at the Guildhall but got distracted by life, winding up with an accidental career in IT and telecoms, and an MBA. He has led sales and marketing teams at companies such as Orange, Tata Communications, and Virgin Media, and now runs his own business helping tech company founders deliver sales growth objectives for investors. Ralph is an NLP practitioner, has authored a couple of books on accelerating performance, hosts a podcast dedicated to helping people achieve results, and writes and records music. Jehan Sherjan (1989-94) is a Director for SRM Europe, a consulting firm focused on using data insight to improve customer experience and operational performance. He is current Chairman of Old Pauline AFC, having been involved with the club since 1997. He studied Social Policy at The London School of Economics and University of Kent. Lorie Church (1992-97) away from the workplace, Lorie encourages people to put letters in little squares. He has had puzzles published in various titles internationally. As well as contributions to the Listener series, Mind Sports Olympiad and Times Daily, he sets Atrium’s crossword. Simon Lovick (2008-13) is a writer and journalist in London, writing for BusinessBecause, an online publication focused around business education, and Maddyness, a UK tech and startup news website. He studied Politics at the University of Edinburgh.

Letters

Sid Pask remembered

Dear Jeremy, What a pleasure to read Barry Cox (1945-50) on Sid Pask (Master 1928-66) in Atrium. I was five years junior to Barry and two below the Miller/Korn/Sacks generation, but remember the young Jonathan Miller (1947-53) horsing about in the playground doing Danny Kaye impressions, and his wonderfully surreal contributions to the Colet Club’s Review with Eric Korn (1946-52) and later John Minton (1948-53). ‘A knoblick is a long stick, heavily weighted at one end with antimony, and used for hitting squirrels’. Did he ever use this line? – I remember him trying it out on us in the tuckshop. I was another of Sid’s students, and vividly recall the thrill of meeting for the first time the amazing littoral and sublittoral plants and animals at Millport, and the traditional haggis-hunt on the final day of the course, with Sid and senior students identifying haggis-nests (sheep hollows) “still warm”, and half convincing the first-timers that it was for real. I have sometimes wondered whether our generation was unusual in its habit of composing songs and verses about the masters. Probably not; but two relating to Sid perhaps merit recording. First, to the tune of ‘John Brown’s Body’: There’ll be no more cricket, rugby, boxing at St Paul’s There’ll be no more cricket, rugby, boxing at St Paul’s There’ll be no more cricket, rugby, boxing at St Paul’s When Sidney becomes High Man. They’ll do away with blazers, and we’ll all wear battered tweeds Etc. The concept of the unconforming, atheistic, sport-deriding Sid as High Master was gloriously absurd. And, to the tune of ‘Dear Lord and Father of Mankind’: There is an aged schoolmaster, And starry are his eyes A bush beneath his nose he grows And stuttering through this growth he shows The right way to tell lies, The right way to tell lies. Alas, poor man, he little knows How little we believe him For how can we who hear his song Of catfish half a furlong long With s-seriousness receive him? With s-seriousness receive him? Sid, who stammered, had taken part as a student in an expedition to Lake Tanganyika, and would frequently regale us with accounts of the giant catfish to be found there. With best wishes, Robin Wootton (1950-55) Honorary Fellow (Insect Biomechanics) University of Exeter

03

LETTERS

Pretentious and Ostentatious

Dear Jeremy,

I wonder if I am alone in finding the magazine Atrium as being both pretentious and ostentatious. The very name Atrium (an inner courtyard) seems wholly unnecessary whereas the previous title Old Pauline News was I suggest perfectly sufficient. Moreover, I find the posed full-sized image of the new High Master on the front cover unnecessarily flashy and the contents a combination of both samey-style and just plain showy-offy. A degree of quiet reserved humility – for want of a better choice of words – would be far more appropriate (especially for a school founded in the Christian tradition – albeit quite rightly wholly open to all creeds and multi-cultural backgrounds). But then of course I am an old fogey who intensely dislikes the ‘Look at me how important I am’ attitude of today. Yours sincerely, Martin French (1952-57)

Dear Jeremy,

Monty inspects the Cadet Force

I was in the Cadets in 1959 and I was lucky enough to be chosen to be in the Guard of Honour for both HM The Queen and Monty’s visits. All I remember of the Queen as she walked in front of me was seeing her hat go by. We had to look straight ahead. I remember Monty arriving in his armoured car, with its reversed angle front windshield. He cost me some credibility and the School rather a lot of money. During the rehearsal for the inspection of the whole cadet force there were a number of boys that fainted in the heat. I think that it was about twenty or so. Some of us opened a “book” on how many boys would faint when Monty came and inspected us. No money was to be exchanged, just the pleasure of being correct. I put down twenty as my guess. But clever Monty had us turn round so that we had less sun on us, and consequently fewer boys fainted proving that he really did care for the wellbeing of the soldiers that he was inspecting. But the big problem for the School came when he addressed us. He stood on the exterior Chapel steps and he had us all sit down on the asphalt parade ground while he talked. The problem was that due to the heat, the tar in the asphalt melted and most of us cadets got tar on our uniforms. We all had to bring our uniforms into school to be cleaned. That must have cost a pretty penny. With best wishes, Andrew Silbiger (1956-59)

Dear Jeremy,

I was interested in reading Bob Phillips’ (1964-68) benign appreciation of Tom Howarth (High Master 1962-73) in Atrium. In terms of his leadership of the School during a period of considerable cultural and educational change, I recognise unreservedly his undoubted achievement in leading the School and its community from West Kensington into the ‘promised land’ of Barnes despite the major problems posed by the then Government and GLC regarding the future of the old school site in W14. However, unlike Bob, for me and many others who were at the School in the 1960s, Howarth was a remote figure, primarily interested in the ‘high flyers’ of the time, with only limited interest in the average Pauline. In one brief meeting with him during his time as Senior Tutor at Magdalene, I probably had a longer conversation with him than in all my five years at the School. Although never a member of any of the three sections myself, I would certainly criticise Howarth for his entirely unjustified abolition of the CCF and for his failing to recognise the architectural, historical and wider cultural value and significance of many of the very fine features left behind in the West Kensington building – such as the excellent stained glass, colourful mosaics and beautifully carved oak fittings from the Chapel and the Walker Library that were subsequently sold off to dealers or otherwise disposed of, rather than being intelligently and sensitively incorporated into the new, Clasp Mark IV buildings at Barnes, providing continuity thereby. I am also surprised by Bob’s comments about Folio for which I wrote occasionally. Folio was certainly not ‘the official school magazine’ as Bob suggests in his article; it was produced by Paulines for Paulines unlike the official The Pauline magazine. Yours ever, Paul Velluet (1962-67)

Dear Jeremy,

ATRIUM

SPRING / SUMMER 2021

Don Pirkis – Rock Thrower

My choice of “A” levels gave me two years of the inspirational Don Pirkis (Master 1955-86). Geomorphology was his forte, rather than Human, Economic or Regional Geography. He showed us lots of landscape slides on ancient epidiascope. If we dozed off in the darkness, he had a supply of tennis ball sized bits of granite to throw at us. (Is that allowed now?) On a family trip to the Lake District, I remember the joy of seeing my first “U-shaped” glaciated valley in real life (Langdale) and some striations on a roche moutonnée, and thinking “Pirkis was telling the truth.” There were no residential field trips in those days, but we did have a day’s fossil hunting in a chalk quarry near Box Hill. I subsequently had a very happy working life – as a Geography Master – at St Clement Danes School. All best wishes, Tim Venner (1954-59)

04

Tom Howarth – a Different Perspective

Dear Jeremy,

Sid Pask’s teaching career book-ended by Ecology Professors

I read Barry Cox's (1945-50) article about Sid Pask (Master 1926-66) and found one thing particularly notable – Sid's tremendous concentration on an ecological context for all he taught. This is very surprising, really, for a London school in which the main biological concentration would naturally be on medicine or some other ‘townie’ sort of biology. Sid had so much influence on the subsequent development of his pupils’ studies of ecology. Several very significant professors and directors in this subject started with Sid at St Paul's. Of particular note are Professors David Goodall (1927-32) and Paul Dowding (1957-62). The first of these, was, until his death in 2018 (in that Zurich clinic) the most influential mathematical plant ecologist of the last century. And it is a very curious thing that both Sid's very first year at St Paul's, and his last, produced a professor of ecology. Both of these (the first being Goodall) changed from other subjects to Biology as a result of Sid's inspiration. I was the second of these, though I would hardly put myself in the same category of influence as David Goodall. Best wishes, Mark Anderson (1961-65)

Dear Jeremy,

“Oh, were you in Dad’s Army?”

Last week I received the latest edition of Atrium at my home in Connecticut, USA. When I was an editor at Fine Woodworking magazine the publisher once said magazines had three types of readers: those who swam through the issue glancing briefly at articles; those who snorkelled and read perhaps one or two articles; and finally those who dived and read the whole issue in depth. I read every page of Atrium and learnt that rabbis could be Masons, and that the birds that eat out of my hand each morning have passerine feet. The article about Tom Howarth (High Master 1962-73) and the move to Barnes reminded me of a couple of stories. When Tom came to lunch at our house one day he was recounting his days on Montgomery’s staff during WW2. My sister Charlotte (1980), then aged 6 or 7, brightly asked, “Oh, were you in Dad's Army?” Luckily Tom took it well! You might also recall that the playing fields at Barnes were not originally prepared properly so that chunks of concrete and rubble kept coming to the surface, to the detriment of rugger players. So for the first several years the fields were repeatedly ploughed and harrowed prompting the granddaughter of Henry Collis to say to Mrs Collis, “Granny, I didn't know you lived on a farm.” My very best wishes, Mark Schofield (1973-77)

Dear Jeremy,

Michael Manning – a Pauline Life Cut Short

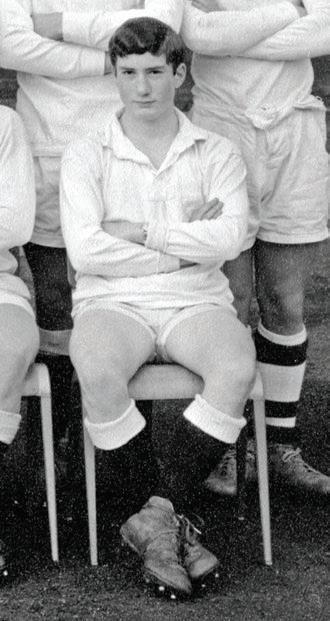

A recent virtual tour of the new buildings prompted me to enquire about the library, which the parents of Michael Manning (1962-66) founded in his memory. Michael was a brilliant student in the History Eighth and an enthusiastic cox in the Boat Club and scrum half on the rugby field and had many other interests. He left St Paul’s in December 1966 prior to taking up his award of a History Scholarship at Magdalen College Oxford the following October, but on 25 June 1967, aged 18, he was tragically drowned in the Thames at Goring whilst participating as a cox for the London Rowing Club in the Henley Regatta. Neither the School nor Magdalen nor the LRC have any record of a memorial library, or indeed any record now of Michael himself apart from the attached 4th XV photograph taken in 1965. He seems set to be forgotten forever but deserves to be remembered. As was written in some tributes at the time, “Michael’s scholarship was exceptional even by Pauline standards, but it was his distinctive personality which will be remembered by those fortunate to have known him. The variety and explosiveness of his non-academic interests made him a delightful and engaging person to talk to. Few people have ever tried to excel in so many fields and managed to make their mark.” If any alumni have information about the memorial library or recollections of Michael himself I would be pleased to know. He was the only son of the family and it has not been possible to trace any relatives. There is probably little more that can be done to commemorate him but in the absence of anything else perhaps this can serve as a brief obituary, memorial and epitaph for this Pauline born 71 years ago who would undoubtedly have risen to fame and fortune, and to golden years, had Isis not claimed him for her own. “So wise so young, they say, do never live long”. With best wishes, Rupert Birtles (1963-66)

Michael Ian Manning: 1965 4th XV Rugby Team

05

PAULINE LETTER

Patrick Neate (1984-89) writes from Zimbabwe Before our daughter was born in 2010, my Zimbabwean partner declared her intention to move home. She had never much liked London, loathing the weather, cult of the sandwich, and embedded sarcasm. “Brilliant” I said. I didn’t take her announcement too seriously. I considered it a manifesto promise, a half-baked idea that could later be kicked into the long grass; like, say, a referendum on UK membership of the EU. It was a surprise, therefore, when I found myself house hunting in Harare within six months. I have come and gone ever since, living the fabled jet set lifestyle of the moderately successful novelist. Initially, I was mostly coming, latterly mostly going. For the last year, I have been gone, thanks to the coronavirus. You may have heard of Zimbabwe. Greatest hits include Robert Mugabe, land reform (retitled “the land grab” in some territories), a three-decade HIV epidemic, deep-seated institutional corruption, hyperinflation, and “the coup that wasn’t a coup” (but was definitely a coup); to say nothing of two England cricket coaches, Makosi from Big Brother Six, and Waitrose mangetout (check the label). I won’t comment in detail on the thornier issues above; partly because I imagine the powers that be are avid readers of Atrium and prone to touchiness, and partly because everything you already think you know about Zimbabwe is probably both completely true and utterly wrong at the same time. It is a “both/and” kind of place – the more contradictory the better.

06

ATRIUM

SPRING / SUMMER 2021

Land reform, for example, is both an overdue attempt to rectify the structural inequities of a racist, colonial history, and a free-for-all for greedy kleptocrats. Likewise, Robert Mugabe was both an erudite, progressive, hero of African liberation, and a tin pot dictator who would sacrifice almost anything (and anyone) to retain power. Perhaps more pertinently (and contrary to the prevailing, western narrative), he was always both those things. He was both when knighted by HM the Queen in 1994 and remained so when stripped of that knighthood after refusing to accept election defeat in 2008. Mugabe didn’t change, we did. The place that Zimbabwe occupies in the western imagination has always fascinated me; likewise the place that the west occupies vice-versa. Although never quite achieving membership of George W. Bush’s “axis of evil”, Zimbabwe did make it onto the second tier “outposts of tyranny” in 2005, alongside North Korea. Heady stuff. Believe it or not, American diplomats are granted extra leave for the hardship of their posting. I have laughed about this while drinking gin and tonics prepared by local staff in the lush gardens of said diplomats’ opulent mansions.

When I return to the UK and tell people I have a house in Zimbabwe, they look at me like I must be quite mad: “It sounds so awful.” Sometimes, I wonder what they’re picturing. Sometimes, unforgivably, I indulge their imaginations with stories of awfulness, which make my life

“ You may have heard of Zimbabwe. Greatest hits include Robert Mugabe, land reform (retitled “the land grab” in some territories), a three-decade HIV epidemic, deep-seated institutional corruption, hyperinflation”

sound edgy and interesting. Zimbabwe can of course be awful but tends to be much less awful, less often, for a relatively wealthy white man. Who’d have thought? The Zimbabwean view of the west is little less puzzling; particularly the idea that we are profoundly interested in Zimbabwean affairs. Fuelled no doubt by a state media that bangs on about ongoing sanctions (only targeted at the elite) and neo-colonial ambition (indisputably a problem but one that’s largely Chinese these days), this belief is as entrenched as it is misplaced. Zimbabweans often think that their economy was first broken by the IMF’s brutal Structural Adjustment Programme in the 1990s and they are broadly (but not completely) right. However, I believe they are broadly (but not completely) wrong to consider this some fiendish plot to undermine national sovereignty. In fact, it speaks not to care and planning but the very opposite. A friend has suggested that the UK regards Zimbabwe as its “prodigal son”. But, to me, Zimbabwe is more like a girl we once snogged who subsequently made questionable life choices and has lately taken to contacting us on Facebook. Sure, we reply sporadically from a mixture of guilt, nostalgia and schadenfreude, but we’re mostly preoccupied with the conflagrating consequences of our own mistakes. And at this moment more than ever. After all, if the UK doesn’t have bigger fish to fry right now, it certainly has a surplus of smaller fish – herring, mackerel and the like … I have noticed attitudes towards the west begin to change over the last few years. And, what began with shock at Brexit, Trump and such, has only accelerated with the galloping pandemic. Here, the government has responded to the challenges much as elsewhere. Like the rest of the world, we have

been in some form of lockdown for a year. But, in this environment, the balance of risk and reward is an even knottier conundrum. If you resent being furloughed in a two bedroom flat in Hammersmith, try being locked down, six to a room, with no running water or state support (honestly, I have no intention of trying either). This, in a place where there is no public health service worth speaking of to protect. This, in a nation with less than 2,000 (official) Coronavirus deaths, which 20 years ago was losing that number to HIV/AIDS every week. The rules are arbitrary and incomprehensible – you can fly 700km to stay in a five star hotel in Victoria Falls but not drive seven to visit your parents. One might even suspect an unconscionable opportunism as those at the top break their own regulations and grant PPE contracts to their cronies. Imagine. And yet, somehow (and always touching wood), Zimbabwe has thus far managed to avoid the worst ravages of the pandemic and watches the UK in horror. Under-reporting? No doubt. Demographics? Probably. After all, life expectancy here is just 61 – most people are dead before the virus could kill them. And the weather’s nice and people spend a lot of time outdoors and aren’t generally obese. But perhaps Zimbabweans have also achieved a certain spiritual immunity, built up over years burying their dead beneath a tyranny of self-serving, mendacious, incompetent crooks; both local and international. Pity those poor Brits with their quaint, outdated faith in accountable government and the rule of law … Lately, when I told someone I hoped to return to the UK as soon as possible, he looked at me like I was quite mad. “It sounds so awful,” he said. Perhaps I’ll stay put for a bit.

07

Briefings Pauline Trainspotting From London Review of Books Vol. 43 No. 1 · 7 January 2021 The Railway Hobby by Ian Jack

On a wet and windy Saturday in October 2020 a few regulars of the Ian Allan (1935-39) Book and Model Shop gathered inside the premises for the last time. The shop – on Lower Marsh, behind Waterloo Station – would soon be a memory, like many things to do with the railway hobby. Stocked with books as well as models, Lower Marsh offered both forms of railway worship – textual and idolatrous – and in the most fitting location, within the squeal and scrape of the trains arriving and departing at Waterloo. It was at that station in 1942 that Ian Allan, then a young clerk in the offices of the Southern Railway, invented – or, more accurately, enabled – the hobby that became known as trainspotting. It made him a fortune, and popularised an affectionate interest in railways matched by no other country. Allan was sent to St Paul’s in London, where as a 15-year-old recruit to the Officers’ Training Corps he lost a leg in a camping accident. His subsequent failure to pass the School Certificate exams ended his hopes of taking up a traffic apprenticeship with the Southern Railway, the first step on the road to higher management, so he became a clerk in the publicity department instead. By 1955, the Ian Allan Locospotters’ Club had 230,000 members, and Allan was publishing lists of almost every mechanical moving object (I’m not sure about tractors) that could be seen on land, sea and air, devoting ABC booklets to British Liners, British Tugs, British Warships, British Airliners, British Buses and Trolleybuses, sometimes narrowing the field to sub-groups such as London Transport, Clyde Pleasure Steamers and the Battleships of World War One. There were specialist magazines – Trains Illustrated was one – as well as more ambitious books that had narratives rather than lists. Ian Allan died in 2015, a day before his 93rd birthday. 08

ATRIUM

SPRING / SUMMER 2021

Allan was sent to St Paul’s in London, where as a 15-year-old recruit to the Officers’ Training Corps he lost a leg in a camping accident.

Pauline Pair

Peter Judge (1930-33) was one of the best bowlers to have played for St Paul’s taking 84 wickets in the 1933 season. He also headed the school batting averages that year. He was good enough to play for Middlesex and Glamorgan over 14 years but he was no batsman, at least at first class level. He holds the record for the fastest pair (two noughts – a pair of spectacles) in cricket history. Coming in at a Number 11 against the touring Indians at Cardiff Arms Park in 1946 he was out first ball to complete Glamorgan’s first innings. The Indians enforced the follow on and, with little time remaining in the game, Judge stayed in the middle to open with his captain Johnny Clay. The usual ten-minute break between innings was even ignored and then Judge was instantly out first ball again.

Pauline Pews Luke Hughes (1969-74) describes the furniture in the new School Chapel Architecture, apart from that of monuments, has little function until there is a table to sit at or a chair to sit on. An unfurnished interior is just an empty space. Furniture articulates and, with luck, embellishes that space; it gives it meaning and enables it to be capable of being inhabited. Conversely, inappropriate furniture can dramatically diminish a building, not only aesthetically, but also for those that use or manage it. Individual pieces also convey stories – about people, places, buildings, events. As well as being symbolic, they are the tactile elements of a building that directly connect across time and space to other hands, other bodies. St Paul’s has, with its numerous previous buildings, rather lost many of those connections.

p The Mercers’ motto, ‘Honor Deo’ is carved across the front of the altar. Photos from Kate East.

The new chapel is part of a multipurpose area for large assemblies presenting an adjoining dedicated sanctuary area, capable of being re-arranged for different types of ecumenical worship (collegiate or eucharistic, with or without choir). The furniture designs are intended to be understated while still speaking of their purpose – namely to support appropriate liturgy and to offer some dignity to ritual. In the brief given to me by the Chaplain, Rev Matthew Knox, ‘the furniture should be a focal point, enabling both the drawing in and the raising upwards’. Quite so. A table for breaking bread in a chapel is not what you expect to find in a library or a dining hall, so there is a deliberate nod to the symbolism of a numinous space, using generous sections and shadows articulated by deep chamfers to bring out the character of the wood in a sculptural way. The furniture, in European oak, comprises an altar or Holy table,

lectern, credence table, and a set of stacking pews picked out with enamelled crests of the school arms. The altar carries on its front panel the three rings of the Trinity, from Colet’s family and the school crests but these are more closely entwined, as is common in Trinitarian interpretation. The school motto, ‘fide et literis’ is carved on the lectern; the Mercers’ motto, ‘Honor Deo’ is carved across the front of the altar and the words ‘non ministrari, sed ministrare’ (not to be served but to serve), from Matthew 20:28, are carved on the credence table. It also includes two handsome ‘presiding’ chairs from the rebuilding of the school in the City during the 1820s, two remarkable hundred year-old survivals from the third era of school buildings. It is surprising how little tactile fabric still remains of the school’s heritage over half a millennium (by comparison, say, to Eton, Westminster or Harrow) but these chairs tell their own story and it feels wholly appropriate they have found a new purpose and relevance.

We are grateful to Alan Rind (1954-59) for his generous donation which funded the furnishing of the chapel. 09

BRIEFINGS

Pauline Shutdown Chris Kraushar (1953-58) alerted Atrium to a term (or part of it) in the early 1950s when Colet Court was closed. He wrote, ‘the difficulties caused by school closures have reminded me of my time at Colet Court. One boy, Charles Foxworthy-Windsor (1953-55) had contracted polio, so the school was closed. There were of course no computers or mobile devices, no email or other methods of communication that we take for granted today. Throughout the term the teachers posted out lessons and homework to each pupil. The homework was posted back, marked and returned by post. There was simply no thought that education should suffer as a result of the closure, and it did not. Of course there were no school sports, and other social contact was discouraged for a time in case the infection had spread more widely. Otherwise life went on as normal. Adults were not considered to be at risk so went about their usual business, and the world at large was unaffected.’ Mike Drinkwater (1954-58) remembers that ‘Foxy’ had the bed next to him when boarding at Colet Court and he recalls them both being ill – Mike merely with flu but ‘Foxy’ with polio. There was some disruption in the Summer term with the Swimming Sports Day cancelled, although Francis Neate (1953-58) remembers a full cricket season including a match against St Paul’s Girls’ School with his sister playing for the opposition. It seems the Colet Court ‘closure’

In August we heard of the shocking disaster over Bulgaria, when a plane flying to Israel was shot down

10

ATRIUM

SPRING / SUMMER 2021

Pauline Prologue was during the autumn of 1952 – with the ‘Coletine’ magazine of spring 1953 having no record of rugby being played in the Autumn term and yet the Spring term football and boxing matches are given full coverage. ‘Foxy’ was a boarder in High House at St Paul’s. His terrible misfortune continued as he was killed in an air crash in 1955 with Alec Harbord (Master 1928-67) writing in The Pauline in 1955, ‘In August we heard of the shocking disaster over Bulgaria, when a plane flying to Israel was shot down. (Editor: Tim Cunis (1955-60) advises me that speculation at the time was that it was by the Russians fearing the plane was spying). Charles Foxworthy-Windsor was on board; he was flying out to spend some weeks in the sun, which it was hoped, would strengthen the muscles still impaired by the polio, which he contracted while at Colet Court. He was a cheerful and sociable member of the House and his death at the age of 15 is tragic’.

1955 plane crash over Bulgaria.

With thanks to Robin Wootton (1950-55) To Jack Strawson, (Chemistry Master 1947-75) and scoutmaster in charge of Troop 3 – in the manner of Chaucer’s Prologue.

And eke a Scoutere, worthy man, was there, That had atop a croppe of redde hair. A hat of brown, that had a wyde brim That was to keep the wette rain off him. A whistle had he to control his boyes With which he oftentimes made muchel noise And he was known to all the companie As he yclept was by his scouts – Jackie.

Pauline Protestor

Pauline Gallantry John Dunkin (1964-69) has alerted Atrium to the gallantry of Tony Jones (1936-41). The Battle of Arnhem in 1944 involved a number of Paulines. Among its commanders were Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery (1902-06) and Major General ‘Roy’ Urquhart (1914-19). Another was a sapper Lieutenant attached to the Guards Armoured Division, later Major General Anthony George Clifford ‘Tony’ Jones of the Royal Engineers. He was awarded an MC for preventing the demolition of the vital Nijmegen Bridge.

p Meenal Viz at Downing Street.

Nishant Joshi (2001-06) graduated in medicine in 2014. He works as a doctor, and early in the pandemic he and his wife, Meenal (also a doctor) launched a successful legal challenge to safeguard healthcare workers.

In his Daily Telegraph obituary in 1999 his Corps Commander, Lieutenant General Sir Brian Horrocks is quoted as writing: ‘Perhaps the bravest of all these brave men was Lieutenant Jones, a young sapper officer who ran on foot behind the leading tanks, cutting the wires and removing the demolition charges’. The obituary also mentions that in his younger days he was a vigorous front row forward for the Old Paulines, the Army, and Combined Services and for Middlesex, winners of the County Championship in 1951.

The BBC reported, “a couple working on the NHS front line say their legal action has led to major changes in how staff are advised to use personal protective equipment (PPE). Doctors Nishant Joshi and Meenal Viz were concerned over the use of PPE as the coronavirus pandemic took hold. Their ‘landmark case’ sparked changes, such as doctors no longer being asked to reuse masks. Both parties brought the judicial review to a close before it reached court, with Dr Joshi and Dr Viz saying both sides were satisfied appropriate changes had been made. The couple’s campaign was motivated by the death of pregnant nurse Mary Agyapong, who contracted COVID-19 and died at the Luton and Dunstable Hospital on 12 April. Dr Viz, who at the time was expecting the couple's first child, protested outside Downing Street during the first national lockdown. The couple said, “Once a detailed enquiry is completed it is likely that the PPE ‘omnishambles’ will be remembered as a national scandal.”

11

BRIEFINGS

Pauline Awards

Pauline Poetry Kintsugi: Jazz Poems for Musicians Alive and Dead

Sir Mene Pangalos

Kintsugi is the debut poetry collection from writer and musician Ammar Kalia (2007-12). A multi-sensory project, Kintsugi is 13 poems written for, about and in dialogue with jazz musicians both past and very much present, accompanied by an album of original drum compositions interwoven with Ammar’s own reading of his work. “Instrumental music has always spoken to me,” Ammar says. “This project was borne from a decade of listening to and playing jazz music, and the more I began to write professionally, the more these words started bubbling up through me, speaking via the collective weight of all that beautiful, improvisatory work to make their own poetic statements.” The result is a clutch of poems that sit in dialogue and in tension with each other, just as instrumentalists fluctuate between harmony and frictive movement in a musical setting. From the angular assertions of “Aromanticism”, a poem for Moses Sumney, to the forlorn aggression of “Someday my prince

will come”, for Miles Davis, and the biographical meandering of “Sphere”, for Thelonious Monk, the verses give a visual and visceral afterlife to these musicians’ work – one seen through the lens of Ammar’s own experiences. Recorded at his family home in Hounslow, where Ammar first learned to play the drums at the age of 6, producer and engineer Matteo Galesi set up a portable studio, collaborating with Ammar over the course of a day to document 45 minutes of rhythmic language and texture on which to set his words. You can find more information at: ammarkalia.bandcamp.com

Sir Mene Pangalos (1980-85) has been awarded a knighthood for his services to UK science. Mene is responsible for BioPharmaceutical R&D at AstraZeneca from discovery through to late-stage development covering Cardiovascular, Renal, Metabolism, Respiratory, Inflammation, Autoimmune, Microbial Science and Neuroscience areas. He has led the partnership with Oxford University in developing the COVID-19 vaccine. Since joining AstraZeneca in 2010, Mene has led the transformation of R&D productivity through the development and implementation of the “5R” framework resulting in a greater than four-fold increase in success rates compared to industry averages. In parallel, he has championed an open approach to working with academic and other external partners, changing the nature of academic-industry collaboration. Mene holds honorary doctorates from Glasgow University and Imperial College, London, is a fellow of the Academy of Medical Sciences, the Royal Society of Biology and Clare Hall, University of Cambridge. He has sat on the Council of the MRC, co-chairs the UK Life Sciences Council Expert Group on Innovation, Clinical Research and Data and is a member of the Life Sciences Industrial Strategy Implementation Board. He is also on the Boards of The Francis

12

ATRIUM

SPRING / SUMMER 2021

Crick Institute, The Judge Business School, Cambridge University and Dizal Pharma. Mene was awarded the 2019 Prix Galien Medal, Greece for his scientific research and named Executive of the Year at the 2019 Scrip Awards.

Sir Terence Etherton (1965-68) will sit as a cross-bencher in the House of Lords as the Lord Etherton of Marylebone. Commenting on the announcement of the peerage, the current Lord Chief Justice, Lord Burnett of Maldon, said: 'Sir Terence has made an outstanding contribution to the nation as a judge, developing the law in critical areas and bringing about lasting improvements to the administration of justice. This will provide Sir Terence with the opportunity to continue to provide service to the public though his contribution to the House of Lords as he retires from the judiciary.'

Sir Terence Etherton

Dean Godson (1975-79) has been made a life peer and will sit as the Lord Godson of Thorney Island. He has been Director of Policy Exchange since 2013 where he has worked since 2005. He has also been the Leader Writer for The Daily Telegraph and Deputy Editor of The Spectator when Boris Johnson was Editor. Broadcaster Iain Dale described Policy Exchange as “the pre-eminent think tank in the Westminster village”, noting that, “Dean Godson, who has

been the Director of Policy Exchange since 2013, has skilfully led Policy Exchange through three different Conservative administrations in a way that other think tanks can only marvel at. The softly-spoken Godson is often thought of as an ideological right winger, yet his pragmatism has enabled Policy Exchange to reach new heights of influence, with dozens of its alumni now sitting on the Conservative benches in Parliament.” Dean Godson

John Clark (1959-63) has received The Cross of St Augustine for Services to the Anglican Communion for an outstanding and selfless contribution to the life and witness of churches of the Anglican Communion, especially in the Middle East and specifically Iran, over 50 years. John’s citation included, “for over 50 years John Clark has supported the mission and ministry of Anglican churches in the Middle East – in the region as a missionary (1970s), as a desk officer (1979-87) and then Communications Director (1987-92) for the Church Missionary Society, as the Partnership for World Mission Secretary (1992-2000) and through decades of volunteering his time and talents as a trustee on the Board of several charities. He served on successive Anglican Communion Commissions for Mission (1989-2005), never seeking the limelight but skilfully navigating tensions to deliver the final report (often having drafted much of it). He was the Archbishops’ Council’s first Director for Mission and Public Affairs. In chairing the Friends of the

Diocese of Iran and the Diocese of Iran Trust Fund (both since 1994) and the Jerusalem & East Mission Trust (since 2008) as well on JMECA (since 1980) he has consistently demonstrated the tireless, level-headed, solutionorientated approach that has long characterised his outstanding contribution. John’s commitment to and support for Middle East Christians goes well beyond the Anglican Communion, making him an exceptional, if unofficial, ambassador for the positive contribution the Communion makes to the life of the Church.”

p The Cross of St Augustine was founded by Archbishop Michael Ramsey and first awarded in February 1965. It is a circular medallion bearing a replica of the 9th century Cross of Canterbury, infilled with blue enamel.

Other awards: Alan Rind (1954-59) has received a CVO for his work as a trustee of the College of St George.

Jonty Claypole (1989-95) has been awarded a MBE for services to the Creation of Culture in Quarantine Virtual Festival of Arts during COVID-19.

Alan Maryon-Davis (1956-62) has been awarded an MBE for services to Public Health.

13

BRIEFINGS

Pauline Books

Jonty Claypole (1989-94) Words Fail Us – In Defence Of Disfluency

Mark Bailey (High Master 2011-20) After the Black Death

Jonty Claypole (1989-94) was bullied at school because of his stutter and spent fifteen years of his life in and out of extreme speech therapy. From sessions with child psychologists to lengthy stuttering boot camps and exposure therapies, he tried everything until finally being told the words he had always feared: 'We can't cure your stutter.' Those words started him on a journey towards not only making peace with his stammer but also learning to use it to his advantage. He is now Head of Arts at the BBC. In Words Fail Us Jonty argues that our obsession with fluency could be hindering, rather than helping, our creativity, authenticity and persuasiveness. Exploring other speech conditions, such as aphasia and Tourette's, and telling the stories of the ‘creatively disfluent’ – from Lewis Carroll to Kendrick Lamar – he explains why it is time to stop making sense, get tongue tied and embrace the life-changing power of inarticulacy.

The Black Death of 1348-9 is the most catastrophic event and worst pandemic in recorded history. Mark Bailey’s (High Master 2011-20) After the Black Death offers a major reinterpretation of its immediate impact and longerterm consequences in England. After the Black Death studies how the government reacted to the crisis, and how communities adapted in its wake. It places the pandemic within the wider context of extreme weather and epidemiological events, the institutional framework of markets and serfdom, and the role of law in reducing risks and conditioning behaviour, drawing upon recent research into climate and disease and manorial and government sources. The government’s response to the Black Death is reconsidered in order to cast new light on the Little Divergence (whereby economic performance in north western Europe began to move decisively ahead of the rest of the continent) and the Peasant’s Revolt of 1381.

14

ATRIUM

SPRING / SUMMER 2021

By 1400, the effect of plague had worked through the economy and society, having wide-ranging implications. After the Black Death rescues the end of the fourteenth century from a little-understood paradox between plague and revolt, and elevates it to a critical period of profound and irreversible change in English and global history.

Rohan McWilliam (1973-78) London’s West End, 1800-1914

Simon Carne (1969-73) I Learned to Write…and to Love Public Speaking

Luke Hughes (1969-74) Furniture In Architecture – The Work Of Luke Hughes

London’s West End, 1800-1914 is the first ever history of the area which has enthralled millions. The area from the Strand to Oxford Street came to stand for sensation and vulgarity but also the promotion of high culture. The West End produced shows and fashions whose impact rippled outwards around the globe. During the nineteenth century, an area that serviced the needs of the aristocracy was opened up to a wider public whilst retaining the imprint of luxury and prestige. Rohan McWilliam (1973-78) explores the emergence of restaurants, grand hotels, concert halls, department stores, sites of curiosity and the sex industry. It is the first of a two-volume work. The second will cover the period from 1914 to COVID shutting down the West End for the first time in its history.

Simon Carne (1969-73) has published a web-book (free to access) called I Learned to Write … and to Love Public Speaking. It is a story about learning to write. Not as a 5-year-old, forming letters and words but as a twenty-fiveyear old business consultant, a thirtyfive year-old writing in the Financial Times and a fifty-five-year old teaching in business school. Simon explains: “I had a lot of fun creating the website and I’ve done my level best to ensure that readers can have at least as much fun reading it. The website is punctuated with links to many articles, news items and videos (not of me!) containing thoughts that reinforce the narrative. Videos on the site include content from Jerry Seinfeld, Greta Thunberg, Rachel from Friends, Tony Blair and a dance coach who prised his way onto the site through sheer force of personality.” The site is not just for entertainment: it is also a helpful practical tool for people who want advice on writing or on public speaking.

Through an introduction to the studio and 25 case studies, Aidan Walker explores the Arts and Crafts tradition and examines the philosophy and work of Luke Hughes (1969-74). The book sheds light on how to balance modern manufacturing technologies with abiding craft values, rendering the small furniture workshop a relevant and profitable proposition even when fulfilling large-scale commissions. This fascinating survey defines the elements of successful design and addresses the meaning of craft and craftsmanship in the digital age.

15

BRIEFINGS

John Shneerson (1959-65) MCC: More than a Cricket Club. Real Tennis and other sports at Lord’s John Shneerson (1959-65) studied medicine and was a consultant respiratory physician at Papworth Hospital in Cambridge from 1980, later specialising in sleep medicine as well. John has continued to play sport ever since leaving school and has written two books on real tennis. His new book looks at how and why MCC, the world’s most famous cricket club, came to play and excel at so many other sports. Lawn tennis, lacrosse, hockey, and baseball are all “lost” sports at Lord’s but real tennis and squash are flourishing. Their story connects closely with cricket at Lord`s but the equilibrium between them and cricket constantly changes. This account probes into the past, weighs up the present, and peers into the future.

16

ATRIUM

SPRING / SUMMER 2021

Christopher Gray (1979-83) Notes on the Piano Christopher Gray (1979-83) is a music teacher and has taught the piano in the Kew, Richmond area for the last twenty-seven years. His book Notes on the Piano by Christopher Russell (his stage and pen name) has just been published in paperback as well as in e-book form on Amazon. Writing in Piano Professional, Murray McLachlan, head of keyboard at Chetham’s School of Music, described Christopher’s book as touching “on vital issues that are of constant relevance to all piano students, teachers and players”.

Richard Hamilton (1978-1983) Tangier – From the Romans to the Rolling Stones Richard Hamilton (1978-1983) is a broadcast journalist for the BBC World Service and an author. His first degree was in Greek and Philosophy at Bristol University. He qualified as a commercial solicitor but had an early mid-life crisis and retrained as a journalist. He has a post-graduate degree in journalism from the London College of Printing and a Masters degree in African Studies from SOAS. He has worked for the BBC since 1995 and was their correspondent in Madagascar, Cape Town and Morocco. In 2011 his first book “The Last Storytellers: Tales from the Heart of Morocco” was published. “Tangier: From the Romans to the Rolling Stones” is a quirky portrait of this Moroccan city as seen through the eyes of writers, musicians and artists including Samuel Pepys OP, Henri Matisse, William Burroughs, Jack Kerouac and the founder of the Rolling Stones, Brian Jones. Richard lives in Acton with his wife Caroline and their two children, plays golf for the Old Pauline golf society and is wondering what to write next.

John Matlin (1956-61) Smoking Gun

Bruce Howitt (1952-56) Terror Redux

The story of newspaperman, David Driscoll who was introduced in “Truth to Power” by John Matlin (1956-61) continues. In the late 1940s, Driscoll is tempted by an offer to save The Durham Monitor, a newspaper heading for bankruptcy. Vanity drives him to leave an important job in Washington DC and head to North Carolina. There he finds he has been lied to by the banker who tempted him with the challenge. He meets the great and good of the state, in particular tobacco baron, Jeremiah Burns. As Driscoll peels away an onion of power and corruption, he places himself and his family in danger but he is determined to bring the guilty to justice.

Bruce Howitt’s (1952-56) first novel The End of Terror was published in November 2019. His second novel Terror Redux is out. After school, Bruce emigrated to Canada attending McGill University. Following a successful business career, he semiretired in 2015 to focus on his writing and his family. Terror Redux is the account of how Israel has destroyed the Middle Eastern arm of Hezbollah. It has regrouped in South America and allied with the drug cartels. Ari Lazarus in the course of his secret agency’s hunt for Hezbollah leaders uncovers a terrifying plot to bring carnage to the United States. Rogue elements in the Chinese Politburo enlist the aid of Hezbollah to carry out massive terror attacks in the heart of six US cities. Ari Lazarus and Israeli Special Forces join together with US Special Forces and SEAL Team 6 and thwart the Chinese plot. Their mission is to end the Hezbollah and cartel reign of terror.

Bernard O’Keeffe (Master 1994-2017) Terror Redux Bernard O’Keeffe worked in advertising before becoming a teacher. He taught at St Paul’s (Master 1994-2017). He has published two novels – No Regrets (2013) and 10 Things To Do Before You Leave School (2019). The Final Round, the first in the DI Garibaldi series, is to be published by Muswell Press in 2021. On the morning after Boat Race Day, a man’s body is found in a nature reserve beside the Thames. He has been viciously stabbed, his tongue cut out, and an Oxford college scarf stuffed in his mouth. The body is identified as that of Nick Bellamy, last seen at the charity quiz organised by his Oxford contemporary, the popular newsreader Melissa Matthews. Enter DI Garibaldi, whose first task is to look into Bellamy’s contemporaries from Balfour College. In particular, the surprise ‘final round’ of questions at this year’s charity quiz in which guests were invited to guess whether allegations about Melissa Matthews and her Oxford friends are true. These allegations range from plagiarism and shoplifting to sextortion and murder.

17

IN CONVERSATION

It did not break us Jon Blair (1967-69) Zooms in on ten Pauline Creatives

I

t was the history that did it for me. Aged just 16, I applied on my own initiative to St Paul’s. I was escaping the apartheid era military in South Africa who had already conscripted me. All I knew about the gothic red brick building on the Hammersmith Road, gleaned from my father during a brief holiday in London 3 years previously, was that this impressive edifice was St Paul’s Grammar School but it was only for clever boys, thereby apparently automatically, at least in my father’s eyes, disqualifying me. In spite of this I rang the School asking how I could apply, and after a hastily written letter delivered by hand that same day, I was summoned to an interview, first with the austere even terrifying Surmaster, Frank Commings (1931-36, Master 1946-54 and Surmaster 1964-76), and then the rather more genial Tom Howarth (High Master 1962-73). I was in.

18

ATRIUM

SPRING / SUMMER 2021

Yes, it was the history that most stirred me: the busts lining the corridors, the Victorian grandeur of Alfred Waterhouse’s edifice, the foundation by Henry’s VIII’s personal priest a century and a half before the first white settlers arrived in my homeland, and the long list of celebrated alumni. To an anglophile boy from the colonies determined to make his own way in a new adopted country it was irresistible. In the years since, with my school days now long distant, I have often wondered how, given its not entirely undeserved reputation as an exam factory, St Paul’s has yet managed to contribute what seems like a disproportionate number of truly distinguished creative men to the arts, whether in the worlds of music, literature, theatre, film or elsewhere. After all, from my own experience at least, while culture in all its various forms was certainly valued and promoted as something in which to be interested, the dominant ethos was that success would first be evaluated by one’s exam results in academic subjects, then by gaining entry to a distinguished university to study something academic, and then ultimately, by one’s career, whether winning a Nobel Prize in physics or chemistry, making a major contribution in medicine, getting to be a Field Marshal, being appointed a senior member of the judiciary, becoming a cabinet minister or perhaps simply becoming CEO of a global conglomerate. While distinguished Old Pauline musicians, actors or writers were to be recalled with genuine affection and even pride, you were rarely encouraged to think that you may join their number. So, what did some of the still living OPs of different generations who have made something of a reputation for themselves in what can broadly be called “the arts” make of their days at St Paul’s, and the degree, if at all, that those few years contributed to their distinguished careers. It would have been lovely to have done this in person round a dinner table, and then perhaps, as in the classic parlour game, moved on to imagine the answers of long and not so long gone Paulines: John Milton, Samuel Pepys, G K Chesterton, Jonathan Miller, Paul Nash, the Shaffer brothers, and many more.

“Given its not entirely undeserved reputation as an exam factory, St Paul’s has yet managed to contribute what seems like a disproportionate number of truly distinguished creative men to the arts”

“How incredible at age 14 or 15 to be given a fully equipped studio and a budget to direct a play”

Max Webster (1996-2001)

But in these days communication with the living is hard enough, let alone the dead, so I restricted myself to Zoom chats with ten very much alive assorted men who have received substantial recognition in their respective fields: two film and television directors, two musicians, two theatre directors, an actor, a biographer, an historian and a designer and builder of eccentric amusement machines. What, if anything, did they have in common with respect to their school days’ contribution to their careers; had they loathed or loved their time at the School; and, most important of all, had those adolescent years made a difference? If I pull one consistent theme from all my chats it is the recognition of privilege that comes from having spent time at St Paul’s. Not that everyone saw that privilege in the same set of experiences. For some it was the quality of the teaching, for others who felt under-valued academically it was the range of the guest speakers who visited, and for yet others, particularly those involved with performance in one form or another, it was the accessibility of high quality space and equipment the like of which almost no state school, and very few public schools, could boast. As actor Rory Kinnear (1991-96) told me, “Over the years there has been something of an arms race between independent schools vying with each other to provide better and better facilities, and St Paul’s seems to have led the way”. Or, as theatre and opera director Max Webster (1996-2001), said: “How incredible at age 14 or 15 to be given a fully equipped studio and a budget to direct a play. What more could an aspiring director want than money and resources?” My interviewees spanned the generations from the 1950’s to the ‘Noughties’, but all implied, or in some cases more explicitly stated, that a career in the arts was never projected by the school as something to aspire to. That certainly was my own experience too in the late 1960’s, and unless things have changed in the last few years, it seems that St Paul’s, while encouraging creativity in the arts, whether it is fine art, music, drama or writing, retains the expectation that Paulines will go on to “a good »

19

IN CONVERSATION

university” and then a more traditional career of one sort or another. Max Webster again: “Drama was seen as fine to do for GCSE, but best not for an A Level if you wanted to go to a good university”, and of course the notion that a Pauline would not want to go to a “good university” was unthinkable. Someone who did do the unthinkable was my oldest interviewee, Benjamin Zander (1954-55), the charismatic conductor and founder of the Boston Philarmonia, whose 2008 TED talk has been viewed over fourteen and a half million times to date. His St Paul’s career is almost the exact opposite of my own, but nonetheless a testament to how an imaginative teacher can change one’s life. Whereas in my case it was Tom Howarth’s willingness to take me into the school in spite of my highly unconventional application, in Zander’s it was the willingness of Anthony Gilkes (High Master 195362) to let him go that set him on his hugely distinguished career.

the summer holidays to study under the celebrated Spanish cello maestro, Gaspar Cassado at the Academia Musica Chigiano. However, when that short sojourn was due to end in late August Cassado could see no good reason why the 15-year-old Zander should ever want to go back to a conventional school education in London. So, Benjamin’s father went to see the High Master who, after listening carefully, asked: “How many times in his life will Ben get such an offer?” to which the reply from Zander senior, quite rightly, was “probably never again.” To his eternal credit Gilkes told the prodigy’s father to “give him a year” and if it did not work out the School would welcome him back. Suffice to say Ben never attended full time schooling again. Whereas Zander’s stay at St Paul’s was just a single year, hardly qualifying the school to even claim him as a distinguished alumnus, film and television director George Amponsah (1982-87), twin brother of Ben who was featured in the last

Benjamin Zander (1954-55)

Zander had transferred to St Paul’s from Uppingham because Jane Cowan, his renowned cello instructor had left and he needed to return to London to study again with his previous teacher. Then, at the end of his first year he went off to Siena for

20

ATRIUM

SPRING / SUMMER 2021

edition of Atrium in the article about Black Paulines, spent rather longer at Lonsdale Road, as the beneficiary of a local authority assisted place at Colet Court and then the senior school. He never felt the racial issue raised its head for him then but his route to a

“His [Zander’s] St Paul’s career is almost the exact opposite of my own, but nonetheless a testament to how an imaginative teacher can change one’s life.”

career in the arts was, how shall we say, anything but conventional: “I had never thought about doing art but one day I was walking past the art block and I peered in through the window in the door and saw a naked lady. I said to myself ‘I can be in there too’ and signed up for art A Level immediately.” For George, who went on to do a foundation year and then a degree in fine art with a speciality in film at North East London Polytechnic, “it was a relief to get away from Barnes to Plaistow. I wanted to be among real people and when I was 18 and on the train to Plaistow I would look at all the businessmen in their suits and feel contempt for them.” But for George it was, like many of the others I spoke to, who vividly made the case for the significance of a particular teacher who, by having faith in a pupil, could totally change their destiny. George believed he was about to be expelled for general rebellion and lack of application, but Ben Taylor (Master 1974-2006), recently appointed housemaster of School House where George and his brother boarded, “saved me. Unlike most of the teachers he had faith in me, and from that faith I got the chance to do art A Level, and now I direct films and television programmes.” George’s highly acclaimed BAFTA nominated feature documentary, Hard Stop, about the 2011 riots that came in the aftermath of the shooting by police of Mark Duggan in a London street, is now to be followed on the BBC by his documentary on the Mangrove trial, executive produced by Steve McQueen; a gig just about any documentary director worth their salt would have given their eye teeth to be offered. The biographer Adam Sisman (1967-71) was another rebel who recalls thinking that the School was “an awful fascist institution.” He told me how he remembered wishing that he could have gone to Holland Park Comprehensive. His main effort at reform in his school days however was, by his own admittance, “largely around uniform and hair length” though this did not stop Tom Howarth accusing him of being a paid agent of the Communist Party. Sisman now thinks that the School in general, and Howarth in particular, had a genuine fear,

George Amponsah (1982-87)

“But for George it was, like many of the others I spoke to, who vividly made the case for the significance of a particular teacher who, by having faith in a pupil, could totally change their destiny.”

this being the late 1960’s, that it was cultivating a new generation of Philbys, and that the revolution was just round the corner. This squares with my own recollection that unlike my South African schools where the staff and the institutional ethos was generally far more liberal than the state, while my peers were generally pretty conservative, the senior staff and leadership at St Paul’s was at least a decade behind the times in its responses to “swinging London” and the politics of the time. I even recall one teacher, a retired brigadier, actively supporting the idea of a military coup against Harold Wilson who was in his opinion, based on “top sources in MI5”, undoubtedly a Soviet placeman. But for all its labelling him as a subversive, Sisman is unstinting in his praise of individual staff members. “The School opened horizons on new worlds for me with stimulating teaching and by introducing and then encouraging conversation and debate.” Head of English, Patrick Hutton (Master 1965-69), encouraged him to write and “sustained me with a stubborn belief in what I could achieve which I would never have had without him. I recall, for example, him picking out a phrase I had used in an essay and reading it out in class, and the pride this instilled in me. In history I wasn’t taught what to think but how to think for myself. The teacher pupil relations were what made St Paul’s special.” I have to say that this chimes exactly with my own experience and I was certainly never as well taught at one of the UK’s top universities as I was by the Eighth Form »

Adam Sisman (1967-71)

21

IN CONVERSATION

English and History departments. Much of what I have taken into my career in terms of how to look at history along with a love of the rhythm of English language dates back to what I picked up from them. Max Webster, too, spoke of how he used his education every day. Engineer, cartoonist and creator of the most wonderfully eccentric arcade machines, Tim Hunkin (1964-68), my exact contemporary, could not have had a more opposite view. I find it almost impossible to do justice to his creations, but suffice to say his Under the Pier Show on Southwold Pier in Suffolk has provided thousands of visitors and residents with hours of fun and laughter. If you cannot get there or to his London Novelty Automation arcade, visit his websites. Some of you may also be familiar with The Secret Life of Machines, his 18 episode Channel Four series from the 1980’s and 1990’s, and the spinoff gallery at the Science Museum, The Secret Life of the Home, which is still one of the most popular installations in the museum. In my view Tim is one of the greatest creative geniuses St Paul’s has ever produced. That said, Tim Hunkin did not like his time at St Paul’s and when I asked him whether there was anything in his academic life there which gave him any sort of encouragement to follow his talent and his creative instincts, the answer was short and to the point: “No. Though the basic science I learnt there is still useful. I don’t have fond memories of St Paul’s. I remember it more as an obstacle to doing anything creative – and still think Saturday rugby was a form of abuse.” Like me Tim found that the School “felt very old fashioned and out of touch. I had no respect for the place. My friends and I took drugs and made bombs in our back gardens, though not at the same time.” And what of any teachers who made an impact? “The thing I was most proud of was keeping under the radar. I did like my friends there though,

22

ATRIUM

SPRING / SUMMER 2021

Tim Hunkin (1964-68)

particularly Hekmuth, who lived in a vast crumbling mansion in Putney where we used to hang out. My friends were always getting into trouble but I generally managed to avoid it and I often think it's the most useful life skill I learnt there.” Reluctantly Hunkin does grant that there was one benefit he got from the school: “It was probably easier getting into Cambridge from their “exam factory” and then I did get a lot out of my time there.” So, what would the 70-year-old Hunkin say to his 18-year-old self? “Have the confidence to follow your nose. Cambridge woke me up and its privileged environment gave me that confidence. Then the responsibility of being so privileged made me try to make the most of my life and contribute to society in some way.” Confidence and privilege. Those two words cropped up almost every time in my chats. As Max Webster said: “How many school boys can say they had lunch with Jonathan Miller, Richard Attenborough, Harold Pinter and more? It didn’t lead to contacts or jobs but it gave a kind of confidence.” Playwright and director

Charlie Fink (1999-2004)

John Retallack (1963-68) has a unique perspective on this as the son of a long serving St Paul’s master who was also in charge of a boarding house. But he was another who says that St Paul’s was “educationally terrible” for him. It made him feel stupid, and to make matters worse, his father also criticised him for not succeeding academically. “At one time I wondered if I should run away and become a journalist. I really didn’t get on with my teachers and remember thinking that there is nothing drabber than being taught by a man who wore the same tie day after day.” Now, more than 50 years on, John admits that another part of him can set that aside and see the school like his mother and father saw it. “I remember seeing my father in a corridor in the old school with Rowe (Master 1957-81) and Allport (1937-42 and Master 1953-87), drinking cups of tea, smoking and laughing. There was a strong collegiate atmosphere amongst them and they were characters who would have voted Tory but moved more left. They felt they were part of a tradition that worked educationally and socially. They had time for the boys. They were ‘masters’, not just teachers.” For John though, it was only when he himself became a teacher and was given charge of school drama at Frensham Heights that he discovered both a love of learning and a love of theatre. “That’s when I began to come into my own. I was placed in a maverick position at St Paul’s so I have lived a maverick life. In spite of, or perhaps because of my father’s criticism for not succeeding at the school I am now so grateful to have done so much. I have done everything I could have wanted creatively.” If John Retallack only came into his own once he had left the school, musician Charlie Fink (1999-2004) was already well set on his career by the time he departed Lonsdale Road. Charlie is better known perhaps as the lead singer of the indie rock and folk band, Noah and the Whale which rocketed to worldwide fame in the late 2000’s before they split in 2015 but more recently he has composed for theatre productions for the Old Vic, the Regents Park Open Air Theatre and elsewhere. “The music school was amazing,

John Retallack (1963-68)

“I was placed in a maverick position at St Paul’s so I have lived a maverick life.”

the facilities extraordinary. To have practice rooms with pianos where you could tuck yourself away at lunch time was such a privilege.” Fink was in a jazz band with George Davies (1998-2003) who was a year older than him and not only did they do lunch time concerts at the school but they graduated to paid gigs at the Kings Head in Putney in front of 250 people when he was just 15. “The thrill of public performance was fantastic.” Charlie is one of several who sing the praises of the Head of English John Venning (Master 1989-2014). “He was amazing and the way we studied John Donne’s Death Be Not Proud’ has definitely influenced my own lyrics. But the school didn’t encourage either music or art as something to do with your life. I suppose, though, it gave me something to push against. That’s important, as it’s what gives you drive. I don’t think I ever felt I really fitted at St Paul’s and by 18 I was furious…I was being told ‘you can’t do this’ and I guess that motivated me more. Too much encouragement is death.” Another who was “gagging to leave” towards the end of his time at School is film and television director Tim Fywell (1965-69). He is now more appreciative and even admits to “warm memories of »

Tim Fywell (1965-69)

23

IN CONVERSATION