ATRIUM

The Interview

Anand Shah –Unicorn Founder

The Educator David Herman meets Ralph Blumenau

The Interview

Anand Shah –Unicorn Founder

The Educator David Herman meets Ralph Blumenau

SPRING / SUMMER 2023

A Brave Front Pauline Sacrifice in WW1

ST PAUL’S ALUMNI MAGAZINE

Atrium now has an editorial board. It has become increasingly evident that the magazine would benefit from having the views and perspective of OPs from across the age range of its readership and the OPC’s membership, which is quite possibly 19 to 105 years old. I am delighted that David Herman (1973-75), Jonathan Foreman (1979-83), Theo Hobson (1985-90), Neil Wates (1999-2004) and Omar Burhanuddin (2017-22) have joined me on the board. It has been a pleasure working as a team over the last few months.

There is a list of Atrium’s contributors on page 3. These include Howard Bailes who is the St Paul’s Girls’ School Archivist, and OPs who were at School between 1939 and 2022; a period that spans ten decades, three school buildings and ten High Masters. It is also important to recognise the contributions made by Kate Wallace and Viera Ghods with the obituaries, Kelly Strickland who has recovered the images from the archives, John Dunkin (1964-69) for his diligent spotting of all things Pauline and our gracefully anonymous proof-readers who catch every typo and much more.

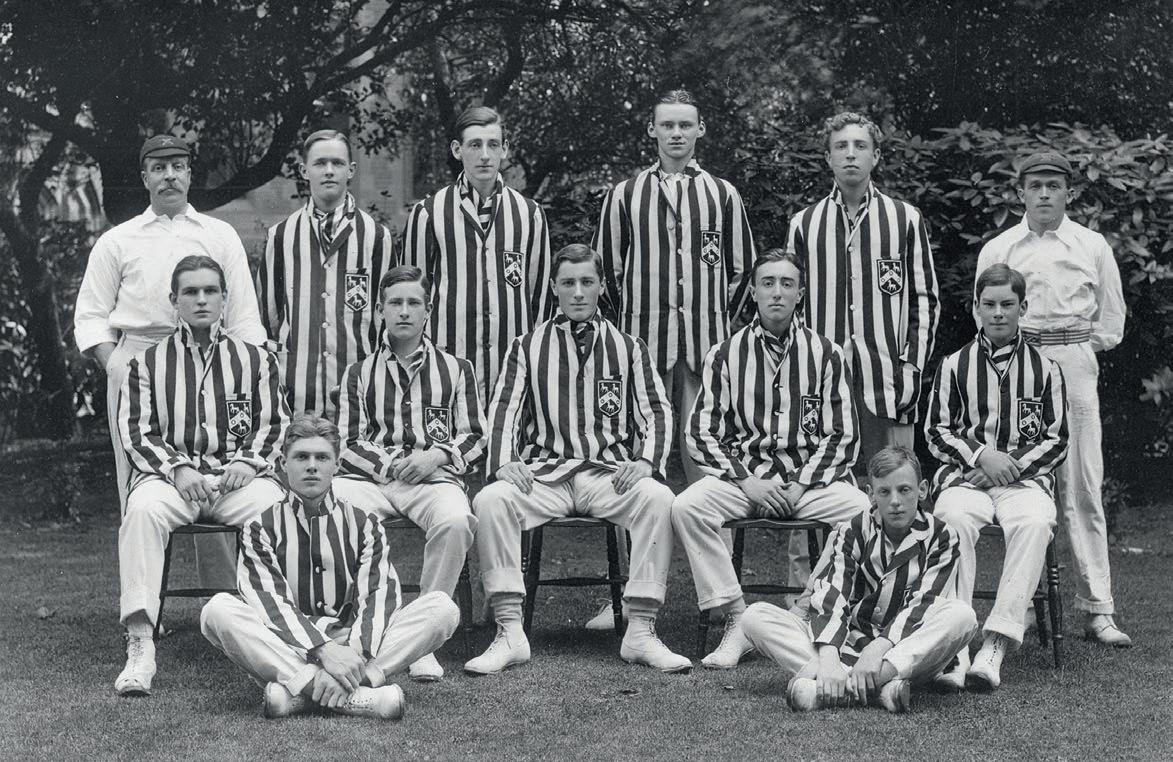

Our front cover is taken from Graham Seel’s wonderful book Scholars and Soldiers: a History of Alumni of St Paul’s School and the First World War. It shows boys from the St Paul’s Officer Training Corps’ camp in the summer of 1914. There is that eternal teenage cocktail of seriousness and cheekiness. Theo Hobson’s article “A Brave Front” based on Graham’s scholarship captures both these.

Thanks to Graham (former Head of Humanities), we now know that 511 Paulines died in the Great War. At last year’s Service of Remembrance, the current cohort of boys and young men of St Paul’s and St Paul’s Juniors

were lined up on ‘Big Side’. From the visitors’ platform one could imagine over a third of them lying down and never getting up. It brought the extent of their predecessors’ sacrifice charging home.

The School’s ‘Shaping Our Future’ campaign is proving brilliantly successful with over £16m raised so far, the majority of which is being directed towards the bursary programme. The goal of 153 pupils receiving a bursary is in sight. A more inclusive future is being shaped. But being an OP is not all about the future, as the Remembrance Service and hopefully this magazine show, it is also about celebrating our past. Whether it is visiting John Milton’s cottage, remembering remarkable members of staff or interviewing an OP German refugee who has dedicated his very long life to education, we have much about which to reflect in the centuries since Henry VIII was our monarch and our School was founded.

One of the main purposes of Atrium is to help all OPs’ experience of St Paul’s to be more than the five years of their time at School. It is a shame if any of us walk out of the gates at 18 and never look back, think back or give back.

Jeremy Withers Green (1975-80)

2 ATRIUM SPRING / SUMMER 2023

Cover photo: Paulines at 1914 Summer Camp Design: haime-butler.com

Print: Lavenham Press

Editorial

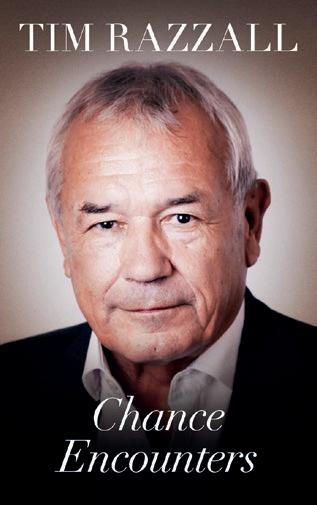

David Herman profiles Ralph Blumenau

Archives, the High Master in the USA, Sport

40 Obituaries

Theo Hobson tells the story of the 511 Paulines who died in WW1

Including Brian Jones OPFC Captain and President and Oscar winner Robert Blalack

44

Pauline Relatives

Omar Burhanuddin meets Anand Shah

Trapp

Howard Bailes reveals Paulina life in WW1

Theo Hobson explores the cottage of one of his heroes

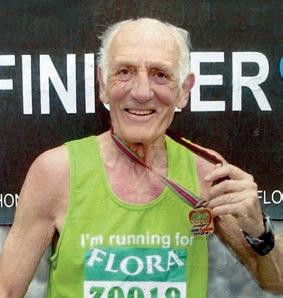

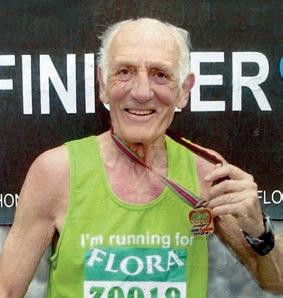

Simon Bishop profiles Pete Murray

Pauline writings about their time at School

Michael Simmons contrasts his and his grandson’s years at School

46 Past Times

Ralph Blumenau remembers WW2 evacuation to Crowthorne

47 Crossword

Lorie Church sets the puzzle

48 Last Word

Matthew Stadlen shares his passion for birds

01 17 46 38 CONTENTS 44 04 Letters

comment on Leaver’s Reports, the

and

06 Pauline Letter

from

remembers his days in the Air Scouts 08 Briefings

memories of

Neill and

Beesley, founders and

17 The Interview

OPs

Aldershot Badge

Tony Richards

Mark Lovell

Vancouver

including

Hugh

Ed

psephology

21 China

more

The Educator

James

asks for less condemnation and

courtesy 24

26 A Brave Front

30 SPGS and the Great War

Milton’s Haven

32

Pauline Pop Picker

34

36 Et Cetera

37 Old Pauline Club News

ATRIUM EDITORIAL BOARD

Omar Burhanuddin (2017-22) is a recent St Paul’s leaver. He has previously held placements at Oxfam and the House of Commons. Now on a gap year, he is currently working as a Development and Engagement Assistant at St Paul’s, and will be taking up a fellowship with the non-profit Project Rousseau over the summer of 2023, serving low-income students across New York City. He aspires towards a career in public policy. Omar is also an amateur violinist and plays for the Fulham Symphony Orchestra and the Central London Orchestra.

Jonathan Foreman (1979-83) read History at Cambridge University, then Law at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. He has been a war correspondent, a film critic, a leader writer, and has reported from Africa, the Middle East and South Asia. He is the author of two books, one on Foreign Aid and its challenges (Aiding and Abetting, Civitas 2015), and the other an anthology of American history (The Pocket Book of Patriotism, Sterling, 2005). He has written for many publications on both sides of the Atlantic and in Asia. He is currently writing a book on empires.

David Herman (1973-75) spent almost twenty years working in television and another fifteen writing for various newspapers, magazines and academic publications.

Theo Hobson (1985-90) studied English Literature at York, then Theology at Cambridge. He has written books on religion, and many articles. He has worked as a teacher as well as a writer and journalist. He recently went to art college, so he is now a struggling artist as well as a struggling writer.

Neil Wates (1999-2004) worked in the property sector for 15 years, latterly as Managing Director of his own firm. He is a trustee of a UK based charitable trust and an NGO committed to the alleviation of social violence in East Africa. He is the founding director of Friendship Adventure, a craft brewery and taproom in Brixton. Neil is the 30s age group representative on the OPC Executive Committee.

Jeremy Withers Green (1975-80) has worked on Atrium for four years. After thirty years in investment banking, he has worked at not-forprofit organisations for a decade as a trustee. He is Deputy President of the Old Pauline Club.

ATRIUM SPRING / SUMMER 2023 02

Members of the Editorial Board met at the St Paul’s Hotel, 153 Hammersmith Road, site of the School from 1864-1968 to plan Atrium Autumn/Winter 2023

Howard Bailes taught History at St Paul’s Girls’ School for some thirty years. He retired from teaching in 2014 but has stayed on as archivist. As well as earlier publications on the Victorian army, he has written a general history of the school (Once a Paulina, James & James, 2000) and supplemented this with various articles on Paulina history. He has also published an illustrated monograph on the architect of the 1904 school and the 1913 Music Wing (Gerald Callcott Horsley: Architect, 2017).

Graham Seel taught at St Paul’s from 2012 to 2021. He was Head of History from 2012 to 2017 and was then Head of Humanities. Graham realised that there were important gaps in the Pauline Community’s knowledge relating to the Great War and that there was a wealth of war-related material in the archives of The Pauline, and so proposed a major research project. The result is Scholars and Soldiers: a History of Alumni of St Paul’s School and the First World War It is in two volumes: the first is a general history of the school and the war, including its commemoration; the second is an in-depth study of OPs who fell in the Ypres area.

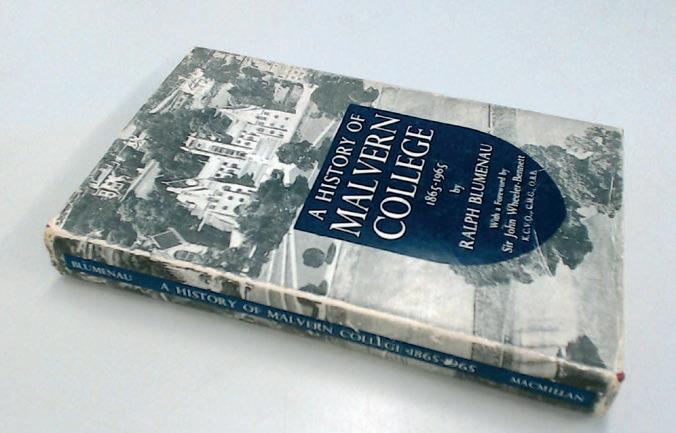

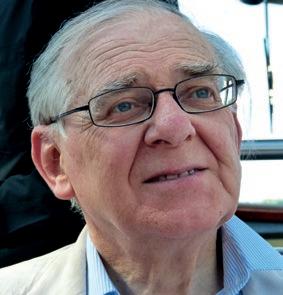

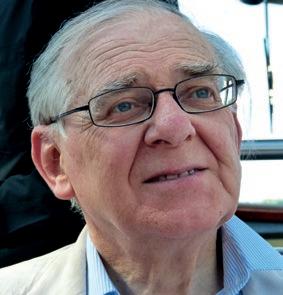

Ralph Blumenau (1939-43) arrived at St Paul’s as a refugee from Nazi Germany. He spent two years teaching at a prep school and then went to Wadham College, Oxford, from 1945-49, where he was awarded a First in History. By the time Ralph left Oxford he had been naturalised and was a British citizen. He became a schoolmaster at The King’s School, Canterbury. After four years he moved on to Malvern College. He became Head of History (1959–1985) writing a history of the school for its centenary. In 1985 Ralph retired, and then spent another thirty years lecturing on European history, the history of Philosophy and the history of the Jews at the University of the Third Age and wrote his best-known book, Philosophy and Living (2002).

Michael Simmons (1946-52) read Classics and Law at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. He qualified as a solicitor and after two years as an officer in the RAF practised Law in the City and Central London for fifty years. Since retiring, he has pursued a new career as a writer. Michael is in touch with a sadly diminishing number of members of the Upper VIII of 1952.

Mark Lovell (1948-1952) became a Russian interpreter and a sublieutenant (RNVR) during his national service. Then he graduated from Jesus College, Cambridge, with an unusual double first: Pt.1 in Classics, Pt.2 in Natural Sciences (Psych.) His business career was in marketing research. He moved from the UK to Canada in 1976, where he became president of the Canadian marketing research association. Mark had several books published between the early 1970s and the early 2000s. Some were under his own name, others under a pseudonym, Peter Rowlands. The best-known is probably Saturday Parent. Mark lives in Montreal.

Simon Bishop (1962-65) is a former editor of Atrium. He has worked in publishing for most of his professional life including as art editor for Time Out magazine and for BBC Wildlife magazine.

Bob Phillips (1964-68) went to Churchill College, Cambridge. Since then, he has been a GMWU shop steward in a bleach works, a social worker, a university lecturer in psychology at Cambridge, a director of a Midlands company making sewers, and a partner in E&Y, running their Philadelphia management consulting office. In retirement, he writes books.

James Trapp (1972-77) graduated from SOAS, University of London, with an Honours degree in Chinese. He worked for 10 years as an art dealer in the West End of London before the art world became disillusioned with him and he with it. While waiting for

China and Chinese to rejoin the mainstream, he trained as a nurse and worked in the operating theatres at Queen Mary’s Roehampton, spent several years as the primary carer of his three daughters and trained as a primary school teacher. He spent seven years as the China Education Manager at the British Museum and went on to run a 5-year project at the UCL IoE Confucius Institute for Schools, developing Primary Mandarin. He now works as a free-lance literary translator, mainly translating prize-winning contemporary Chinese novels but he has also produced new translations of three of the Chinese classics: The Art of War, The Dao De Jing and selections from The Book of Songs

Lorie Church (1992-97) when he is away from the workplace, Lorie encourages people to put letters in little squares. He has had puzzles published in various titles internationally. As well as contributing to the Listener series, Mind Sports Olympiad and Times daily, he sets Atrium’s crossword.

Matthew Stadlen (1993-98) went to Clare College, Cambridge. He graduated with a first in Classics. Since then, he has presented and produced TV series at the BBC, written an interviews column for The Telegraph, hosted his own shows on LBC, interviewed hundreds of public figures on stage, appeared on Sky, the BBC, Channel 5, Radio 5 Live and elsewhere as a political commentator and recently launched a podcast, 20 Questions With.

Guy Ward-Jackson (2016-21) after finishing St Paul’s online during the first year of the Coronavirus pandemic, Guy went on to study History at Oxford and is currently in his third and final year. At Oxford, he has edited The Oxford Blue newspaper and is currently writing his undergraduate thesis on late Victorian magic.

03

ATRIUM CONTRIBUTORS (not on Editorial Board)

a liberal, secular and moral ethos

Dear Editor,

I am an Old Malvernian (1957-1962), who envies the St Paul’s alumni for Atrium. I am passed on the magazine by an OP, Sawanit Kongsiri (1956-1960), a valued colleague and close friend at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Thailand and the Thai Red Cross Society for 53 years.

I wish to refer to David Herman’s article “Refugees at St Paul’s”, which appeared in Atrium, Spring/Summer 2022. At Malvern, I was taught by an OP, Ralph Blumenau (1939-42). His family had immigrated from Cologne in 1936. He went from St Paul’s to Wadham College, Oxford, got a First, taught at King’s Canterbury before coming to Malvern where he became Head of History (1959-1985). He was a brilliant and inspiring teacher who taught me everything; not just history, but art history, classical music appreciation, even French and Latin in History with Foreign Texts A level. He carefully corrected our essays and style of writing and made sure that we cited our sources. Thanks to his superb teaching, I won an exhibition to King’s, Cambridge, where the senior history scholar of my year was Alan Howarth (now Lord Howarth of Newport), son of St Paul’s High Master Tom Howarth.

At Malvern, Ralph wrote “A History of Malvern College 1865-1965” (Macmillan 1965), which is the standard history of the school. In his retirement, he became a teacher at the University of the Third Age where, if I recall correctly, the Times Education Supplement called him a “star”. There he published “A History of the Jews in German-Speaking Lands” (University of the Third Age in London, 1995), followed by his translation of Joel Kotek’s Students and the Cold War (St. Antony’s Series, Macmillan, 1996). Ralph had been International Vice-President of the National Union of Students from 1949 to 1951. Finally in 2002 came his masterpiece. “Philosophy and Living” (Imprint Academic), where he distilled western philosophy from the Greek Cosmologists to Foucault.

I write the above to you for the record in gratitude to my teacher and mentor, Ralph Blumenau. He taught me everything especially instilling a liberal, secular and moral ethos, which has guided me throughout my life.

Yours sincerely,

Tej Bunnag – Secretary General, Thai Red Cross Society

exam results 90%, interview 20% and school reports minus 10% Dear Jeremy,

I enjoyed Jon Blair’s witty and perceptive piece on reading his Leaver’s Report. Knowing Jon, I was not surprised. I have not read mine but have no difficulty imagining what it might have said – not all flattering, to be sure!

Jon ends with the statement that “Reports are far more indicative of the prejudices of our teachers than of who we were or what we would make of our lives”. Undoubtedly true, but I wonder how many of us realise that this was already recognised even as long ago as Jon’s time and mine, at the end of the 1960s. I vividly remember the Admissions Tutor at my College saying that he scored exam results 90%, interview 20% and school reports minus 10%. Mind you, King’s College Cambridge was a bit radical in those heady days, so maybe not all tutors took the same approach.

Mike Segal (1964-68)

04 ATRIUM SPRING / SUMMER 2023 LETTERS Letters

Malvern College

Tony Richards remembered Dear Editor,

Congratulations to you, your Deputy Editor, contributors and proof-readers on the latest issue of Atrium

A well-chosen front cover given the recent passing of Her late Majesty, but why no mention of Tony Richards (ANG Richards MA of Magdalene College, Cambridge) who features so prominently in the photo showing the Queen in the Walker Library on her visit to the School in May 1959?

Sadly, only those who left the school before c.1970 will recognise him – as he retired from over forty years’ full-time teaching at the School at the end of the summer term, 1966 – as form master of the Lower Classical Eighth from 1929 to 1966; as Senior English Master for many of those years; as Librarian of the Boys’ Library from 1930; as Librarian of the Walker Library from 1946; as editor of The Pauline from 1930 to 1966; and as Housemaster of Edgebarrow Hostel during the School’s exile at Easthampstead Park between 1939 and 1945; and continuing as School Archivist until December, 1968.

For me, I am eternally grateful to Tony Richards for his support and encouragement in my researching the history and development of Waterhouse’s school buildings at West Kensington during my last term at School, from which he drew for his slim, red volume – St Paul’s School in West Kensington, 1884-1968 – published in 1968, and for his wise counsel in the correspondence we maintained in the years thereafter. For me, too, as a reader of MR James’s ghost stories, I always valued and enjoyed Tony Richards’ recollections of his conversations with the famous author, antiquarian and Provost of Eton College (1918–1936) during his time as a scholar at Eton in the 1920s.

Yours ever, Paul Velluet (1962-1967)

Pothunters Dear Jeremy,

I write in connection with the leading letter from the former OPC archivist in the recent Atrium which included a most interesting photograph of the St Paul’s School Gymnastics Team of 1911.

I observe the letter just focused on the partially obscured arm tattoo of a PT instructor and the ‘Pauline Tattoos’ caption is a bit misleading as in those days it would have been risible for any Pauline scholar to sport such adornments.

Mention could have been made of the ‘Aldershot Badge’ on the vests of the Pauline team members which was introduced in 1895 for those competing in the prestigious ‘Public School Gymnastic, Boxing & Fencing Championships’ held annually at Aldershot. The original badge included boxing gloves, crossed swords and the School Arms.

Paulines were successful at the Aldershot Championships as were Old Paulines in the many Army, Navy and civilian boxing competitions of the era.

St Paul’s School’s reputation in boxing was mentioned in literature of the time. This is an excerpt from P G Wodehouse’s novel The Pothunters (1902):

“Any idea who’s against us?”

“Harrow, Felsted, Wellington. That’s all, I think.”

“St Paul’s?”

“No.”

“Good.”

Pip pip, John Dunkin (1964-69)

5 05

St Paul’s School in West Kensington 1884-1968

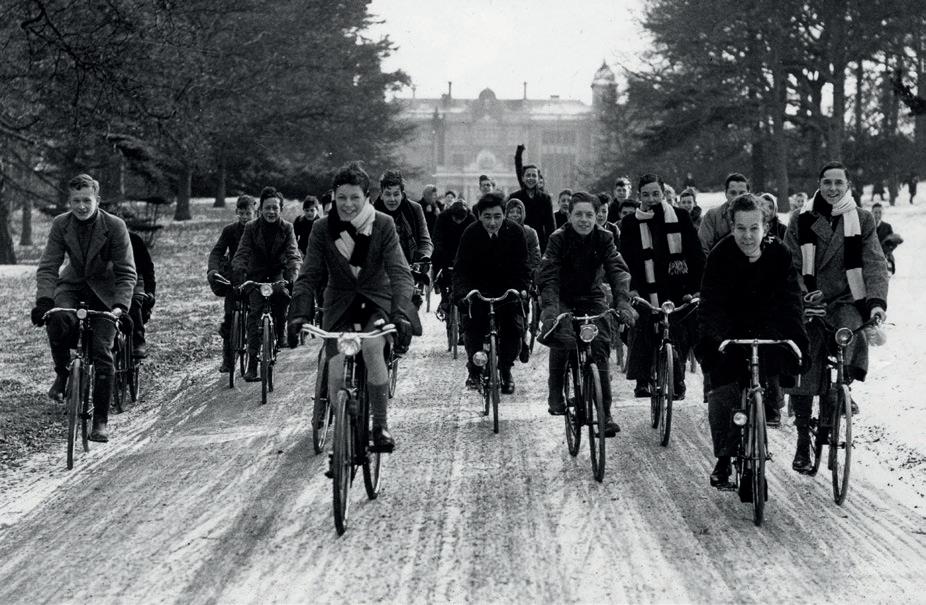

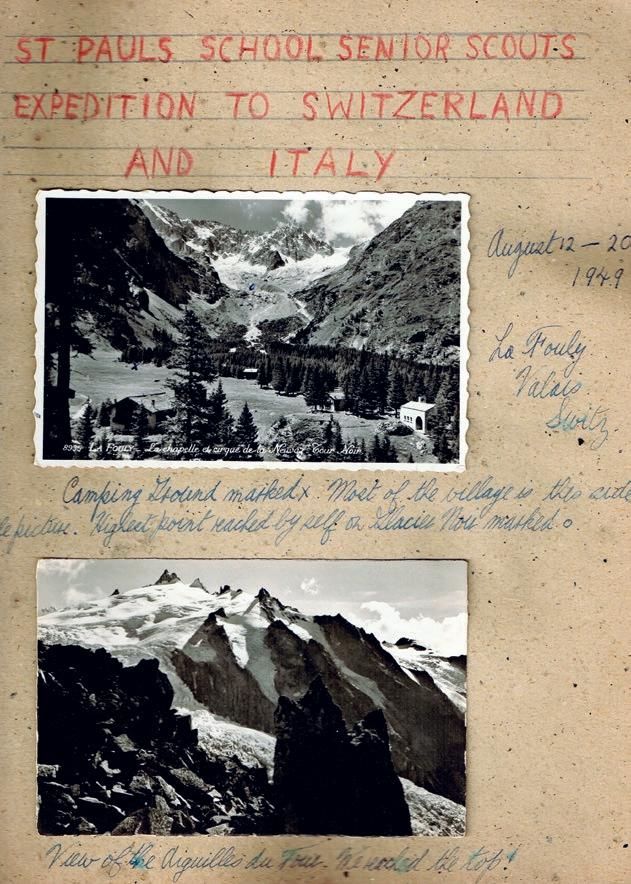

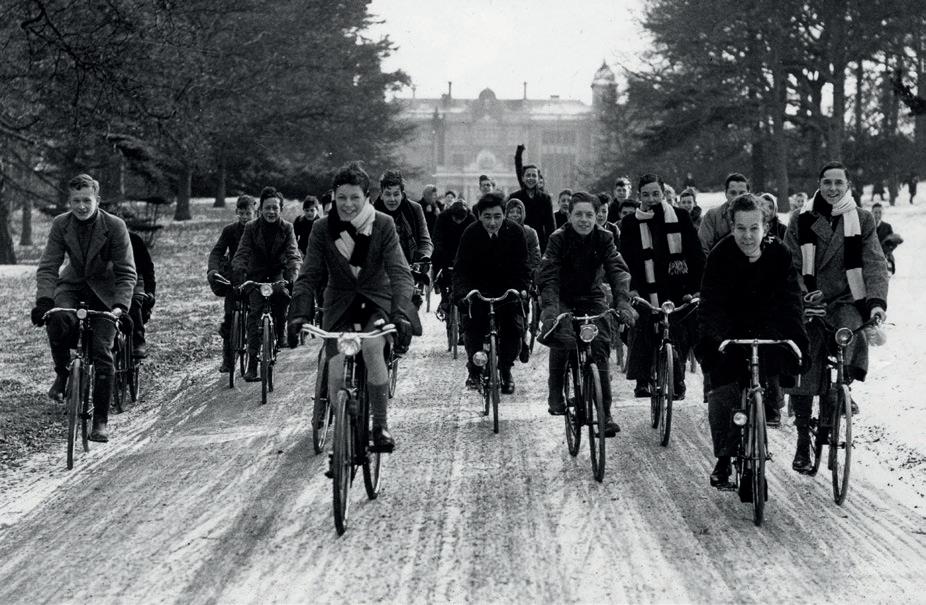

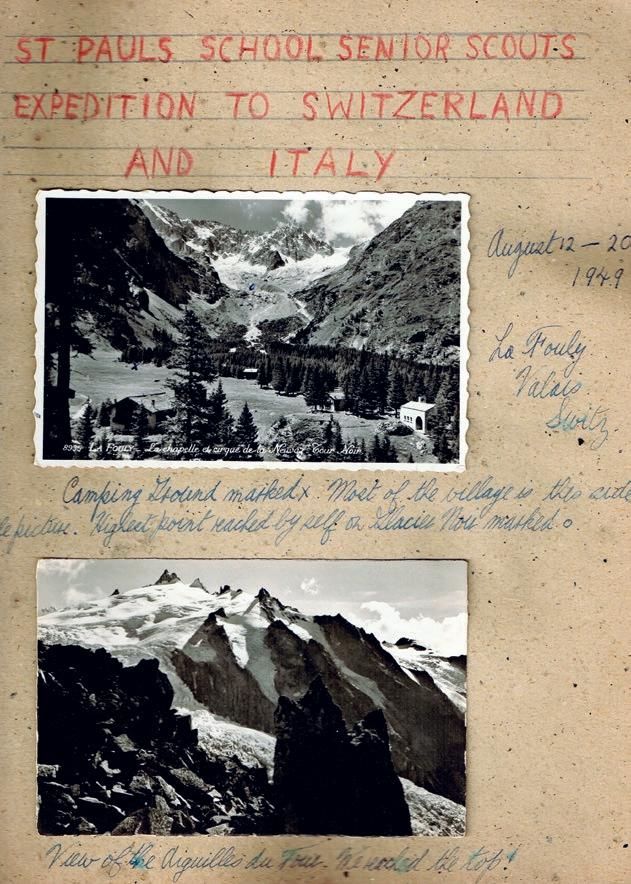

Letter from Vancouver: A Scout’s Road to Fiesole

Mark Lovell (1947-53) writes from Vancouver about his travels with the St Paul’s Air Scouts

“No, the Combined Cadet Force is not the only option for Monday afternoons.” My parents had been waiting hopefully for this message. I was 13: in a month’s time I would make my transition from The Hall to St Paul’s. I had got a scholarship, so they did not look elsewhere.

My father was glad I would be switching from soccer to rugby. He was less enthusiastic about khaki uniform once a week or my learning to clean a rifle. My mother wondered aloud “Is this obligatory?”

The alternative, my parents learnt, was to join one of the school’s two troops of Boy Scouts. One troop wore light brown, as had Baden Powell. The other uniform was grey, more up-to-date, and appealed to me personally: I became an Air Scout.

Most of my new St Paul’s friends went into the CCF. The Second World War had officially ended but a sense of military duty lingered. Opting to join the scouts seemed to some to be less than patriotic. Conscription disappeared but National Service (two years’ worth) loomed ahead. There was a widespread rumour that CCF experience gave you an edge there, if only because you saluted appropriately and knew the difference between the front and back of a rifle. Others, however, believed that SPS was offering a choice between individuality and premature regimentation.

There was another angle that certainly motivated me. The scout troops made trips abroad. A year before my entry, a lucky batch had gone to Sweden in the summer holidays. Foreign travel by British school children post-war was very limited. European expeditions organised by the Scouts opened the door just a chink. Many British families hungered to widen it.

Expectations of a better future, of a world without world wars, were high. This was during the period when the Cold War was still not fully apparent. “Going into Europe, are you? Next summer?” Note the personal pronoun my parents used: the Scouts had become ‘You’. My real European education was about to begin.

No description of Pauline scouts in the late 1940s and early 50s would be complete without mention of James E Pretty (Maths department and scoutmaster 1946-53). We added an ‘E’ to his initials and knew him as ‘Jeep’. He liked that. It meant more than acceptance, it registered proximity. Occasionally he added the second ‘E’ himself when signing a note. Jeep was a war hero, but this was rarely discussed. He had been held in a brutal Japanese POW camp for years in the Far East. Jeep himself rarely mentioned this spontaneously. He had somehow turned the page.

He was a great organiser where travel was concerned. He had acute perception of the individual potential of each scout at his disposal, calculating how much responsibility each could handle.

PAULINE LETTER

Mark Lovell’s scrapbook

06 ATRIUM SPRING / SUMMER 2023

A good organiser realises he cannot be everywhere. Jeep studied us individually and assigned duties appropriately. Small teams were sometimes put together: this meant I could be drafted in to help with French if an argument with locals turned sour. Similarly, I could summon a maths whizz if I was struggling with the budget and expenses.

In retrospect, Jeep’s skills were focussed mainly on encouraging everyone not just to perform, but to enjoy –to keep a sense of humour, even if given the laundry or the state of the tents to observe and improve.

I was fortunate in being able to participate in two major trips, in summer 1949 and summer 1950. Each was split between a week or so in the mountains, followed by time in cities that had impressive things to offer. There was always something unexpected and memorable to take away.

In the French Alps we put up our tents wherever seemed best. In Assisi, we were allowed into an olive grove beside a monastery. How this improbable deal was put together I simply do not know. Probably it resulted from Jeep’s smile and enthusiasm. I overheard him once explaining our needs to somebody important – an abbot, maybe – once we had scrupulously cleaned our campsite after breakfast. They shook hands warmly.

Later, a monk warned us against an imminent rainstorm. “Oh no, we’ll be fine in our tents,” was our answer. Mercifully the storm was short-lived. Then there was music: the monks were singing ‘Santa Lucia’ and the monastery windows were open.

I described this afterwards to my parents. “Very romantic, I’m sure,” was my father’s comment. He preferred me to talk about Giotto’s 14th century frescos in the San Francesco church nearby.

Memorable moments were sometimes linked to major sights, sometimes not. The first view of the cathedral in Florence was breath-taking, as was the Ponte Vecchio. But the moment that has lived in my memory most vividly was an afternoon visit by bus to neighbouring Fiesole.

Just three of us were the sub-group that made it to Florence: Michael Dale (1944-49) was the senior scout in charge, while Chris Westwick (1946-51) and I made up his team. We stayed in a youth hostel, making friends with a few French scouts. This kind of loose arrangement would probably have been anathema to an insurance company in the later 1950s.

“What’s in Fiesole?” A bus trip added to expenses. We were not exactly sure, but Dale felt it merited a try. There was supposed to be a Roman amphitheatre and a great view. Both materialised. And there was more…

We climbed up the amphitheatre levels, sometimes whispering to each other, testing the famous acoustics as suggested by a guidebook. At one point we heard an answering whisper, from a man in his forties dressed in grey. Bob greeted us politely. He was an American visitor. He told us he had been here before, with a US army unit on a ‘combined op’.

“See that little hill? …just to the right of the red rooftops?” He did not wait for an answer. “That’s where we were,” he said. “Advanced position.”

He switched to the battle without warning. They had been observed, studied and almost wiped out. Bob was the only survivor aside from two others still in hospital. He had already made two earlier trips to see it all again. Now he waved us goodbye.

He had taught us something we could not forget.

7 07

But the moment that has lived in my memory most vividly was an afternoon visit by bus to neighbouring Fiesole.

Briefings

Masters Remembered Hugh Neill (Maths Department 1966-72) –“Well? Has anyone got it?”

Bob Phillips (1964-68) shares his memories of his inspirational maths teacher, who died in 2022.

Hugh Neill, who died in August 2022, was a Head of Maths at St Paul’s who presided over revolutionary change. His predecessor A J Moakes was something of a visionary, seeing the coming transformation in maths teaching that went under the label of “New Maths”. But, as this new wave approached, Mr Moakes was into retirement age. The appointment that he, and the then High Master, Tom Howarth, made to meet this challenge was revolutionary.

Hugh Neill was a very young man, catapulted into the lead of one of the most prestigious departments of mathematics in any school. I met him in my first year in the school, in 5X, in 1964, and I think that was also his first year at St Paul’s, too. A J Moakes was still around for a year – teaching the A level classes – so I guess that Hugh Neill did not formally take over the department until 1965.

he was asking from the front “Well? Has anyone got it?” A couple of boys had – in no time at all.

They were asked to explain, but Mr Neill put it in general terms – “Make a transformation. If the man crosses the river at right angles to the banks, you can transform the diagram as if the river didn’t exist. Then the path follows the straight line from A to B. Simple.”

I was devastated. I felt as if he had cheated and was prevailing upon us to cheat. That was not mathematics –mathematics is hard grind. That was sleight of hand.

of UK industry. The standard model A had a huge 16K memory. BP allowed the consortium – St Paul’s and a couple of other schools – to submit programs for execution on the night shift, when possible. Hugh Neill invested in a Hollerith machine for hand punching the 80-column cards that fed the computer. Another school invested in an interpreter that read the cards and printed the contents across the top.

Mr Neill created, over a summer holiday, a fat duplicated file of problems amenable to attack using the FORTRAN language. The enthusiasts among us, me included, picked a problem or two. There ensued a painful round of coding, punching, sending in the mail, interpreting, sending in the mail, correcting, etc., etc., before BP would mail to the school a printout on fan-fold paper that would tell the eager student what a mess he had made.

He certainly shook up the maths class. I can tell a personal story from 5X that shook me. It was probably my first maths class at St Paul’s.

Problem. A man needs to get from A to B but there is a river in the way. He can only cross the river at right-angles to the banks. What is his shortest route?

Terribly simple, isn’t it? The 13-yearold me set about diligently with trigonometry, but Mr. Neill allowed no time for that. In no time at all,

It took me weeks to come to terms with this, and more jolts kept coming. Matrices. Sets. Probability. He was setting the whole realm of mathematics in a new framework.

There was one “New Maths” innovation that I took to instantly. Hugh Neill introduced computer programming to St Paul’s after he had been there a couple of years. I guess that he had been working at this innovation for some time, because it took a collaboration of several different institutions to pull it off.

It was BP that had the computer – a magnificent ICL 1904 mainframe, pride

But it was so exciting! That is my chief memory of Hugh Neill –he made all of this so exciting. That mark of a brilliant teacher. Didn’t Howarth do well to bet on him as such a young man?

Hugh Neill’s list of publications runs to over 70 titles, including the one that marked the revolution at St Paul’s: by A J Moakes and H Neill, Vectors, Matrices and Linear Equations. The paperback edition was printed in 1967. Hugh Neill moved on from St Paul’s, and found a huge audience for his brilliant teaching through his authorship of all these books. Hugh Neill was Chief Mathematics Inspector for the ILEA. He also taught at Durham University for 10 years and was Staff Inspector of Mathematics.

ATRIUM SPRING / SUMMER 2023 08

Dr Ed Beesley (History Department 2018-22)

Guy Ward-Jackson (2016-21) shares his memories of Ed Beesley who died in December 2022.

A keen, fresh-faced group of Lower Eighth students sit tentatively in a classroom laid out like a seminar-room, waiting to receive the feedback from their first A-level history essay. Shortly, an uncombed Dr Beesley with an untucked shirt (as ever) walks in holding a stack of papers, grinning as though he is about to have a lot of fun.

He leans against the side of his desk and looks up at all of us, still grinning, and with a slight twinkle in his eye which only finds itself on the best kinds of teachers. “They’re all crap”, he says, of our essays on post-war reconstruction in America. Our hearts sink as we ask ourselves why we decided to take history A-level. He relishes in our despair. Dr Beesley then proceeds to explain to us that this is not GCSE history anymore, and that listing a bunch of ‘factors’ is not going to get us anywhere. We nod silently. Then the devil’s advocate is unleashed upon us like a bursting dam: “Surely it’s not that complicated?”, he asks. “Reconstruction failed because they were all racist and didn’t want to offer African Americans real freedom. No?”. We sit, discombobulated. A class of eight supposedly clever Paulines –amidst all their clever factors and short-term, medium-term, and longterm causation – had failed to consider this simple question. After having his fun grilling us, he eventually reassures us that we have a lot of potential, but that we need to pull ourselves out of GCSEish ideas of causation.

From that moment, though, we all knew we had stumbled upon something special. Those Lower Eighth American history lessons still feel like some of the best and most lucid learning I have experienced. We were tackling the biggest issues of the most influential country in the world, sitting around that little seminar table, with Dr Beesley always leaning over desks or pacing around the room, bringing energy to every conversation. It was almost as if that room on the second floor was a gateway into a whole different world of thinking and academia. Dr Beesley reminds me of the young temporary teacher, Irwin, in The History Boys who invites intellectual dissent amongst the boys to get away from stuffy teaching

norms. Any discussion could be had, just so long as Ed was able once in a while to take a puff of his industrialsized vape. From American history, to witchcraft, to the English Civil War, he sparked endless interest in areas which still fascinate me (I decided to write my undergraduate dissertation on magic, a topic originally introduced to me by him).

I like to think that I had a special relationship with Ed but looking back on it I think that was his great skill. In his own way he had a close relationship with all his students, nor did he really have favourites or prefer the better historians (in fact he would often just tell me to chill out, especially in the run up to Oxbridge interviews when I epitomised the overly anxious Pauline). This much was clear on the tributes page to him: Dr Beesley to so many was not just a teacher but the teacher. The teacher every person dreams of but only some are lucky enough to have. The one who really made them interested in learning for learning’s sake. One contemporary of his described him as a ‘colossus’, and I think that is strangely apt.

A friend of mine also wrote about one run-in he had with Ed when the student had been particularly under the cosh: “I remember that after a particularly painful meeting during which it had become apparent, I had done not one iota of the work required for my coursework, he decided to compliment me on a recent theatrical performance. This, to me, embodies the man. Academically ruthless, but always in service of his student’s attainment. And, when all was said and done, and the textbooks and gobbets and love of all things ‘early modern’ was put away, he always made sure to say a kind word before running off to another hopeless Pauline”. His words are as accurate as

mine in trying to capture the man. He was intellectually razor sharp but all the while humble and wearing his capabilities lightly. Having said that, he did often boast about how he had beaten a fourteen-year-old Tim Henman back in his peak tennis days. A few decades and more than a few pints later you would never have guessed…

After I left St Paul’s we stayed in touch, at one point over the summer he called me to discuss my dissertation. Unsurprisingly, we ended up spending most of the time lamenting Liz Truss’s leadership campaign and our plans on moving country were she to become Prime Minister. In hindsight, I wish we had met in person to catchup. But, then again, Ed was always reminding his history students of the dangers of hindsight.

For so many I know, Ed Beesley opened a door to intellectual curiosity and interest in a way that only very rare teachers can. Some dent the door, but he threw it open. When you really think about it, it is a spectacular legacy to have. For every single student Ed Beesley taught, that door will always remain open.

09

Paulines Streaming

Whether it is Netflix, Amazon Prime, Sky, ITV or the BBC, there are Paulines everywhere in what was once the post watershed drama slot when all good children were tucked up in bed.

It could be Blake Ritson (1991-96) playing the camply subversive Oscar van Rhijn in The Gilded Age, Leo Suter (2007-12) fresh from Sanditon playing Harold Hardrada in Viking Valhalla, the Lloyd-Hughes brothers – Ben (200106) in The Ipcress File or Henry (1998-2003) in Killing Eve, Shubham Saraf (2005-10), on stage recently in The Father and the Assassin at the National, as Firoz Ali Khan in A Suitable Boy, Will Attenborough (2004-09) as Lieutenant Hurst in

Our Girl, playing the slightly out of his depth officer struggling to be respected by his troops or Rory Kinnear (1991-96) playing a community hero on Netflix in Bank of Dave

On the other side of the camera, BAFTA winner Patrick Spence (1981-84) as Creative Director at ITV Studios is one of the forces behind the acclaimed dramas Maternal, Spy Among Friends and Litvinenko

Pauline Gallantry

The Pauline June 1914 reported on an interclub boxing tournament.

‘SENIOR BANTAMS (8 st 4 lb). Final – Neville (C) beat Johnston (C). Neville was the more experienced. He attacked with his left and his footwork was good. Johnston was rather of the novice class; he tried hard to stave off his more experienced opponent, but was not quite able to do so.’

Johnston lost a more important scrap 3 years later.

Flight Commander Philip Andrew Johnston (1911-14) – Royal Naval Air Service. Served in 8th (Naval) Squadron and was accredited with 6 victories. He was killed in action on August 17th, 1917.

The Pauline October 1917 has an obituary which includes this eulogy from his Commanding Officer: “He was quite one of the finest pilots I have ever seen, and he was absolutely wrapped up in his profession. He loved flying, and also made a special study of the science of aviation and constructional problems. Before he came to me, he had made a big name for himself in the Service as an experimental and test pilot, and he proved his all-round efficiency when he came out to the Front with this squadron and did equally excellent work as a fighting pilot”.

10 ATRIUM SPRING / SUMMER 2023

BRIEFINGS

Will Attenborough

Blake Ritson

Leo Suter

Shubham Saraf

Henry Lloyd-Hughes

Ben Lloyd-Hughes

Sopwith Pup 9917

Pauline Psephologist

Pauline Appointments

Matthew Gould (1984-89) has been appointed the director-general of the Zoological Society of London. It appears to be his dream job.

Matthew had been the CEO of NHSX, The NHS’s digital transformation arm, where he was responsible for the largest digital transformation in the world. He was previously the British Ambassador to Israel and the Government’s cyber-security chief. In December 2022 Matthew wrote in The Times,

Sir David Butler (1938-42) who helped to invent the ‘swingometer’ and became an essential part of BBC Television’s all-night general election coverage, died on November 8, 2022, aged 98.

David was born on October 17, 1924, the day of the first radio election broadcast by the prime minister Stanley Baldwin. At School he was friends with Nicholas Parsons (1937-39) who later in life commented. “I remember him talking about Abyssinia, and the Italian invasion, he had great knowledge for a youngster." His masters were not as convinced with one school report bizarrely including, “Butler has many very nice traits but he is a bit whimsical, puerile, and I think probably suffers from having elder sisters.”

After St Paul’s, he read Philosophy, Politics and Economics at New College, Oxford for two terms before joining the Staffordshire Yeomanry. He did officer training at Sandhurst and found himself – still only 19 – leading a daring crossing of the Rhine. On his return to Oxford, he struggled with the philosophy part of his PPE degree. Sir Isaiah Berlin (1922-28) regarded him as the “most unphilosophical pupil” he had taught. “I can’t remember which is deductive and which is inductive for more than ten minutes,” he told Berlin. As Butler was an ex-serviceman, Berlin was able to arrange for him to take a shortened course in PPE in 1946 which avoided any more philosophy. Butler dealt in numbers and facts not thoughts.

The founder of Polling Report, Anthony Wells said of David: “As a student of elections it was always sort of awe inspiring to be able to sit and talk to David Butler. It was like a mathematician getting to sit and talk to Archimedes, or a Physicist getting to meet Newton.”

At St Paul’s, David’s first love was cricket, especially working out the batting and bowling averages. The County Championship was suspended during World War Two and, when not in action he found himself with time on his hands, he applied the same mathematical rigour to past election results. The rest is psephological history.

and “Do I miss my old life? I suppose I miss the car and driver, the house with a flag, the unearned respect that ambassadors get. Sometimes I am even wistful for the shenanigans and politics of Whitehall. But then I get to watch tiger cubs play.”

Old Paulines who received honours in the New Years’ Honours included James Reed (1976-80) CBE for services to business and to charity, Floyd Steadman (Colet Court Common Room, 1990-2001 and Honorary OP) OBE for services to Rugby Union Football, to education and to charity, Philip Souter (1982-86) OBE for services to medical research and Dominique Jacquesson (1984-88) MBE for services to technology and to entrepreneurship.

11

“It is a job I have coveted for decades. When a friend and fellow ambassador was appointed to the role a few years ago, any joy I felt for him was obliterated by a sharp jealousy that he had got my job”

Matthew Gould in conversation with Ed Vaizey as part of The Future Of series at St Paul’s School

Sir David Butler

Pauline Founders

John Dunkin (1964-69) has shared with Atrium his research into Pauline founders of clubs, societies and organisations.

The Royal Humane Society

Co-founder and first Register

Dr William Hawes (c. 1748) in 1774 when known as The Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Drowned.

Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade

Co-founder Thomas Clarkson (17751779) in 1787 who helped achieve passage of the Slave Act in 1807 which ended British trade in slaves.

Society for the Promotion of Permanent & Universal Peace

Co-founded by Thomas Clarkson and his brother Lieutenant John Clarkson (c. 1779) RN in 1816. Also known as the International Peace Society, this pioneering pacifist organisation was active until the 1930s.

The Cambridge Camden Club, later the Ecclesiological Society

Benjamin Webb (1828-1838) cofounder with John Mason Neale established in 1839 as an architectural society to study gothic architecture.

The Jesus College Society, Cambridge

Founded by Dr Henry Menzies (18801886), it was launched in 1903 with Menzies as Hon Secretary which he remained until his death in 1936. Henry Menzies was a first-class cricketer, he played for Middlesex CCC 1892-93 during which time he was credited with stumping the great ‘WG’ at Lord’s.

Toc H – Talbot House was co-founded in 1915 by The Reverend Philip Thomas Byard ‘Tubby’ Clayton (1897-1906) MC and Neville Talbot at Poperinge, Belgium. Tubby and Neville opened Talbot House, named after Neville’s brother, Gilbert who had recently been

killed in action. Over the entrance to the chaplain’s room at Talbot House were the words “All rank abandon, ye who enter here”. Tubby’s aim was that Toc H (morse signaller’s language for T.H.) should be open to anyone and everyone, to be a place of fun and games and God.

On his return to London, Tubby established Toc H in London with All Hallows by the Tower becoming the movement’s guild church in 1923. What had worked with all ranks at Poperinghe also worked as an ecumenical Christian movement focused on fellowship, service, fairmindedness and the kingdom of God. It caught the mood after the devastation of war and the Spanish flu. It gave meaning during the hard economic years of the late 1920s and 1930s. Toc H grew to have thousands of branches in the UK (there are still over a 100), hundreds overseas and a women’s association was set up.

The Jesters Club

A sports club founded by John Forbes ‘Jock’ Burnet (1923-29) while at School when he and a few friends wanted to play cricket in the holidays. It expanded into fives, squash and rackets and continues to flourish. Jock Burnet later became Bursar and Fellow of Magdalene College, Cambridge.

The Osler Club of London

Dr Walter Reginald Bett (1919-22) co-founded this club in 1928 in order to encourage the study of the history of medicine and to preserve the legacy of Sir William Osler, a celebrated international physician. The Club still meets eight times a year at the Royal College of Physicians.

British Exploring Society

Originally the Public Schools Exploring Society, the BES was founded in 1932 by Surgeon Commander George

Murray Levick (1891-1895), who had taken part in the final, fatal Scott expedition to the Antarctic in 1910-13. Based at the Royal Geographic Society building in London, it provides opportunities for young people to take part in wilderness expeditions. It received unfortunate publicity in 2011 after an Eton boy was killed by a polar bear while camping on Svalbard. Surgeon Commander Levick was also the founder of the Royal Navy Rugby Union.

The Royal British Legion

The premier veterans’ association and military charity of the UK – the red poppy is its trademark – was cofounded in 1921 by Major General Sir Frederick Barton Maurice GCB GCMG, GCVO, DSO. After the death of co-founder Earl Haig, he became the Legion’s president until 1947. Gen. Maurice (1917-18) was also a President of the Old Pauline Club and attended the official opening of the Old Pauline Football Club clubhouse at Thames Ditton in 1930.

The Labrador Club of South Africa

Founder and first Chairman – George Alfred Jenkin (1936-39) in the 1950s and on return to England in 1965 a member of the Labrador Club for 30 years and foremost expert in the country of the breed. As a young officer in East Yorkshire Yeomanry in June 1944 he won an immediate MC within 24 hours of landing in Normandy. The citation reads “exemplary coolness and courage”.

The Rhino Cricket Club

Co-founded in 1966 by John Dunkin, Peter Dunkin (1969-73), Colin Dring (1959-64) with Richard Felton nephew of Robert ‘Bob’ Felton (1924-29) who played for Middlesex CCC.

12 ATRIUM SPRING / SUMMER 2023 BRIEFINGS

Tubby Clayton

Jock Burnet

Pauline Books

Atrium unless otherwise described uses ‘reviews’ provided by authors or their publishers.

Todd M Endelman

The Last Anglo-Jewish Gentleman: The Life and Times of Redcliffe Nathan Salaman

David Herman (1973-75) reviewed Todd M Endelman’s: The Last Anglo-Jewish Gentleman: The Life and Times of Redcliffe Nathan Salaman for the TLS. We republish with permission.

For more than forty years Todd Endelman has been a leading historian of Anglo-Jewry, the author of The Jews of Georgian England, 1714-1830: Tradition and Change in a Liberal Society (1979), Radical Assimilation in Anglo-Jewish History, 1656-1945 (1990), and The Jews of Britain, 1656-2000 (2002). His latest book is a biography of Redcliffe Nathan Salaman (1886-92), who became a physician, philanthropist and botanist.

Salaman’s father, Myer, made a fortune out of ostrich feathers and London property dealings and his children, including Redcliffe, lived off it. There was a darker side to Redcliffe’s personal life. One child died young; another was mentally disabled. His first wife and two brothers died in their forties, another brother died in his twenties and a fourth in early childhood.

Redcliffe Salaman was educated at home until he was 10, when he was sent to live in a boarding house in West Kensington for Jewish boys attending Samuel Bewsher’s Preparatory School for St Paul’s. He entered St Paul’s in 1886. In the late 19th century few Jewish boys attended Britain’s public schools. According to Endelman, ‘the first Jewish boy entered the school only a few years before Salaman arrived.’ During his time at the school there were about thirty other Jewish boys, including his older brother Euston. He encountered anti-Jewish sentiment and was never really happy at the school but it does not seem to have scarred him, unlike Leonard Woolf, who arrived just after Salaman left. Later he and his wife did not send their sons to St Paul’s, writes Endelman, ‘because the current headmaster was antisemitic.’

In 1892 Salaman was awarded a science scholarship at Trinity Hall, Cambridge. He then studied at medical school in London and briefly in Germany. He went on to live the life of a country gentleman in a grand house near Cambridge for the rest of his life (hence the book’s title) but served as an army doctor during the First World War. He became a major figure in Anglo-Jewish communal life between the wars, developed a lifelong interest in studying potatoes and published widely on race science and eugenics, until the rise of Nazism. Perhaps his greatest achievement, though, was as a philanthropist supporting Jewish charities. He helped found the Jewish Health Organization of Great Britain, set up to help improve the health of Jewish immigrants in the East End, became a governor of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and was a key figure in the Academic Assistance Council, which helped many distinguished Jewish refugees from Nazism come to Britain during the 1930s.

Most interesting of all, though, Endelman constantly puts Salaman’s interests in a larger historical context, exploring British antisemitism, the rise of race science in the early 20th century, the history of the British Mandate of Palestine and the debates which divided Anglo-Jewry. All of Endelman’s strengths as a social historian come to the fore and what emerges through these chapters is a rich account of Anglo-Jewish history over a century.

13

Rob Stewart (1981-85) How to Do Research, and How to Be a Researcher

There are many textbooks on research methods, plenty of books on popular science, and specialist texts on a whole range of academic fields. However, few bring these together as a framework for a career involving research, and few attempt a practical appraisal of the challenges and opportunities involved in being ‘a researcher’. Here, the principles underlying humanity’s past and continuing acquisition of knowledge are illustrated across a variety of academic fields, from history to quantum physics – telling stories of clever and inventive people with good ideas, but also of personalities, politics and power. This book draws together these strands to provide an informal and concise account of knowledge acquisition in all its guises.

Having set out what research hopes to achieve, and why we are all researchers at heart, Rob Stewart, Professor of Psychiatric Epidemiology and Clinical Informatics at King’s College London in the early chapters describes the basic principles underlying this – ways of thinking which may date back to the philosophers of the Athenian marketplace but are still powerful influences on the way research is carried out today. Drawing on a broad range of disciplines, Stewart takes the reader well beyond the pure ‘scientific method’, which might work well enough in physics or chemistry but falls apart in life sciences, let alone humanities. Later chapters consider the realities of carrying out research and the ways in which these continue to shape its progress – researchers and their personalities, their employers, funding, publication, political forces, and power structures.

Written in an accessible and engaging style, this book is for anyone embarking on a research project or beginning to think about a career involving research, and for those in need of refocusing on why they started research in the first place.

Erik Jensen (1947-50) The Struggle for Western Sahara: The UN and the Challenge to Diplomacy

The dispute over Western Sahara between Morocco and the Polisario Front evolved into full-scale war and after four decades remains unresolved. UN military observers separate the Polisario forces from Morocco’s vast army but progress towards a settlement has been halting and the UN mission in Western Sahara is now among the longest running peace-keeping operations in the world. Here, Jensen provides a unique insider’s account of the UN’s involvement in Western Sahara, how the UN Settlement Plan was, after numerous obstacles, eventually put into operation and why it stalled. The Polisario is now adamant that only a referendum of self-determination with the option of independence is acceptable while Morocco offers a compromise settlement based on regional autonomy under Moroccan sovereignty. Both entrenched positions are constantly reaffirmed and unlikely to vary without major political change in the region.

14 ATRIUM SPRING / SUMMER 2023 BRIEFINGS

Damian Dibben (1979-83) The Colour Storm

The Evening Standard describes The Colour Storm as ‘an epic tale of love, of courage, of hope’ and The Mail on Sunday suggests the reader should ‘bask in the brilliance’.

Enter the world of Renaissance Venice, where the competition for fame and fortune can mean life or death. Artists flock here, not just for wealth and fame, but for revolutionary colour. Yet artist Giorgione ‘Zorzo’ Barbarelli’s career hangs in the balance. Competition is fierce, and his debts are piling up. So, when Zorzo hears a rumour of a mysterious new pigment, brought to Venice by the richest man in Europe, he sets out to acquire the colour and secure his name in history.

Winning a commission to paint a portrait of the man’s wife, Sybille, Zorzo thinks he has found a way into the merchant’s favour. Instead he finds himself caught up in a conspiracy that stretches across Europe and a marriage coming apart inside one of the city’s most illustrious palazzos.

As the water levels rise and the plague creeps ever closer, an increasingly desperate Zorzo is not sure whom he can trust.

Will Sybille prove to be the key to Zorzo’s success, or the reason for his downfall?

Atmospheric and suspenseful, and filled with the famous artists of the era, The Colour Storm is an intoxicating story of art and ambition, love and obsession.

John Matlin (1956-61) End Game

The San Francisco police are totally baffled when the leading Democratic candidate for California Governor is murdered. There are no clues or witnesses. San Diego police investigate another murder where there is only one piece of physical evidence. But there is nothing yet to connect the two killings. A major industrialist and the new Democratic contender for governor are in the frame but the evidence is merely circumstantial.

Retired journalist, David Driscoll, finds himself thrust into helping a candidate in the Democratic Governor race and the San Francisco Police Department by using contacts he made two years previously as a journalist in the Las Vegas criminal fraternity.

Police inquiries hit one dead end after another, driving the drama through California’s big cities and important towns, Congressional committee hearings in Sacramento and the underworld of Los Angeles. When suspicion arises that a murder for hire business is being marketed, the evidence that leads to solving the murders is startling and shocking. “Politics, murder, and the darker side of a bright California – End Game is faster than a Disneyland roller coaster and just as exciting” – Scott Lucas: Professor of International Politics, The Clinton Institute, University College, Dublin.

15

Peter Cromarty (1966-71) Death or Grievous Bodily Harm

Peter Cromarty spent his paid working life in aviation, first as an air traffic controller and pilot, and later as an air traffic control safety regulation specialist and manager. He finished his aviation career with nine years as an executive manager at the Australian Civil Aviation Safety Authority. Peter is now a homemaker, aircraft builder, and writer.

In Death or Grievous Bodily Harm, Tobias Richmond is quietly enjoying his retirement until he plays good Samaritan at his local shops. Soon, he and his family are sucked into the violent world of ruthless drug dealers, police corruption, and competition for the lucrative drugs markets of Southeast Queensland.

This is a fast-paced story about a man drawn, against his will, into fighting for his life and the lives of his family. Not knowing who they can trust or where to turn for help, the Richmond family face threats to their lives and take on vicious killers who want what they know.

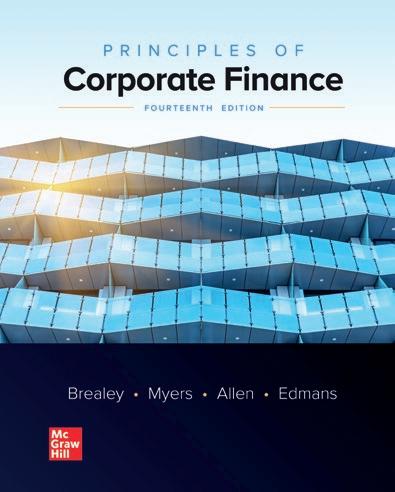

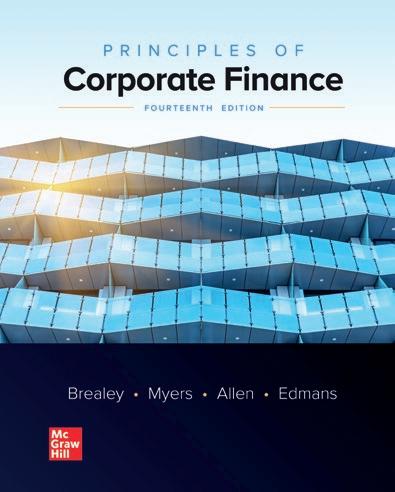

Alex Edmans (1993-98) Principles of Corporate Finance

Principles of Corporate Finance, first published in 1980, has long been known as the “bible” of finance. It was the core finance textbook when Alex read Economics and Management at Oxford University. After graduating, Alex joined Morgan Stanley’s investment banking division, where all new analysts were given a copy and the book sat on the shelves of all the senior bankers. Alex then embarked on a PhD in Financial Economics at the MIT Sloan School of Management, where he used it as a teaching assistant for Professor Stewart Myers, one of the original co-authors. His first academic position was at the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, where he taught it as a professor for the first time. After earning tenure, he returned to the UK in 2013 as a Professor of Finance at London Business School. He was named worldwide Professor of the Year by Poets and Quants in 2021.

After studying, using, and then teaching the book for 24 years, Alex was invited to be the new co-author of the 14th edition, which was published in 2022. This new edition is more modern. Most notably, it stresses how a CEO has a responsibility to wider society (customers, employees, the environment, suppliers, communities, and taxpayers), rather than just generating short-term profit for his shareholders. But it equally emphasises that this responsibility is not “woke”, but good business – a manager that promotes the interest of all stakeholders will typically outperform his peers in the long-term. The new edition recognises that markets are not always efficient, but affected by psychological biases, building on Alex’s work on how the stock market is affected even by World Cup football results and music listening choices. It is truly global, rather than focused just on the US, and highlights ways in which FinTech is changing financial practice.

The new edition uses female pronouns for CEOs throughout (and male pronouns for investors). This is not a gimmick, but out of recognition for the role language plays in reinforcing or neutralising biases – particularly in a book which, to many, is their first experience of finance.

16 ATRIUM SPRING / SUMMER 2023 BRIEFINGS

Anand Shah (1993-98)

Have you done an interview for St Paul’s before?

No, unfortunately not. I have lost touch with St Paul’s over the last decade when I left the UK – although I did recently meet with Nick Troen (Geography Department) to discuss the entrepreneurship work that he’s leading. That said, my way of staying in touch with St Paul’s is through a group of six mates that I’ve met regularly now for 30 years, one of whom is a co-founder, Alex Barrett (1993-98).

That leads into something I wanted to ask you about. Considering that you founded a company with someone who came from St Paul’s, I wonder if you could reflect on the importance of an alumni network and maintaining connections with your school. Do you think that is important? Yes, I definitely do think it’s important, although it was more serendipity for me and Alex in the way we came together. I know there’ve been some alumni meet-ups after 5, 10, 15, 20 years: I left the UK in 2011 so unfortunately, I’ve not been able to make the last couple. But those types of thing really help: it’s going to happen naturally through the friendships made at school, sometimes through sports teams, or boarding house for example. I spent all my time – I don’t even know whether St Paul’s still has a bowl – but I spent all my lunch breaks down at the bowl with these guys playing five-a-side football. That was great – that was something we did 5 days a week throughout the year, and those sorts of opportunity don’t come back again.

17 THE INTERVIEW

Omar Burhanuddin (2017-22) discusses founding and running the tech ‘unicorn’ Databook with Anand Shah (1993-98)

It’s been written elsewhere that your path – from St Paul’s, to Imperial, to Goldman Sachs, to ICMA, to Columbia and LBS, and then Accenture – is more the path of a Senior Partner, and less that of an entrepreneur. What motivated you to diverge from that path, and set up your own business?

Looking back, I definitely could’ve stayed on that path. However, it became more and more obvious over time that all the entrepreneurs in my family had instilled a burning desire to create and innovate. When I was looking for a job out of university, I wanted to be a professional in a big corporate job, because I wanted to spend more time with my family on weekends – something I didn’t do with my parents growing up. The mythical allure of a Monday-to-Friday job at a large Corporate with time available on the weekends was attractive. The opportunity came with Accenture which I was very grateful for: I had many interesting projects whilst I was there. But every couple of years I felt quite itchy about whether I was doing the right thing, whether I should be somewhere else. After about six years at Accenture, and an MBA, I made the shift towards entrepreneurship but still internally, call it ‘intra-preneurship’. However, it’s a very different thing, when you’re creating something new within an existing organisation with a large safety-net. But it gave me a taster of building a team, funding the operation, training people, marketing, and delivering value for customers. Spending five years doing that within a larger organisation, it got to the point where I felt: ‘OK, I’m really getting itchy now, I really need to go and do something outside’. And so, I created a business plan, and here we are. I think, to go down the Senior Partner track, I would have needed to conform more. I’m very focused on improving the way the world works and I didn’t fit the constraints of a partnership model that was defined by others.

Another aspect of your shift to entrepreneurship I’d like to ask you about is the role of AI in your work. It’s something many people in our younger alumni network are looking at getting into. Surely AI is one of the most central aspects of Databook, as the world’s

first AI-powered customer intelligence platform. When did you spot the potential for AI to be used in that way?

I had a very interesting post-Accenture experience. Actually, leaving Accenture wasn’t an obvious choice with a young family and moving to California. So, we came to an agreement where I would lead a project between Accenture and the World Economic Forum: the project was called the ‘Digital Transformation Initiative’. The project was looking into the impact of technology on business and society to 2025. That was really a spark for me. I saw that there were technologies, such as robotics, drones, cybersecurity, AI, cloud computing and mobile, that were coming together and creating what we called a ‘combinatorial effect’, that was driving significant productivity improvements. For example, Google Maps now uses AI to predict the best time to leave from home and the best route to travel. That’s a very big change from 20 years ago when you had to open up your AA road map and plot your way from A to B.

The idea of a fully autonomous, functioning and thinking computer is still the end result everyone’s thinking of and wary of. That’s still a pipe dream, but the advances in deep learning such as DALL-E and ChatGPT are examples of where the future of AI is headed. When I started Databook with Alex [Barrett], we used more simple AI techniques such as natural language generation and natural language processing to help us to do things which a human could do but would take a really long time. We are now starting to use more advanced techniques that amplify human expertise by 100x. All that said, we use AI in our platform, but it’s certainly not our only technology, since we’ve had to build up a lot of skill and IP in other areas.

While Databook was essentially a first-of-its-kind, it now faces competitions in the Sales enablement market, from Seismic and Highspot to Showpad and Outreach. Where, whether technological or cultural, do you believe Databook’s differentiating edge lies?

If you build an AI system in 3-6 months and put it out on the market, it’s likely that someone else can build something very similar and put it out on the market

18 ATRIUM SPRING / SUMMER 2023

THE INTERVIEW

Anand and his business partner at Databook, Alex Barrett

immediately afterwards. We’ve instead been able to take decades of experience, and embed that into our algorithms and platform directly, allowing us to stack new insights on top of these. AI is a way of building mechanisms to speed up the algorithms and improve them, but it still requires a human expertise and practical experience to make ethical and business judgement calls. That’s a critical part of utilising AI: making sure that there’s good controls and explainability on the results. We’re still working with it, and I think there are going to be huge leaps about the way we’ll use AI in the future.

Databook has done brilliantly, with 300% growth year-on-year for the last four years. Do you think you’ll take the company public in the foreseeable future?

Growth at smaller scale isn’t easy but it certainly looks better in percentage terms! In terms of going public, not any time soon and especially in this market, but yes that is one of our stated goals. We hope to become a public company at some point, but you’ve got to grind away at these things for long periods of time and we just completed five years so we still have a way to go.

I want to go back to your family. You said your father, and his incredible work ethic, was one of the greatest motivating factors for you. Are there any figures in the corporate world today – or, considering your recent interest in history, from the past – who you would consider a role model?

Yes, for sure. A few examples – perhaps not necessarily role models, but people I think have done an exceptional job over long periods of time, say 30, 40, 50 years – are founders like Marc Benioff, the Founder-CEO of Salesforce, and Bill Gates, the founder of Microsoft, and Peter Gassner, Founder and CEO of Veeva Systems. I admire individuals like them who’ve started companies, created jobs and innovation, and later tied it back to philanthropy and sustainability. It’s not a surprise that both Salesforce and Microsoft are strategic partners and investors in Databook. I’m keen to see how we can follow their footsteps in that regard. One of the things I was reflecting on recently was the case of my grandfather.

He started a civil engineering company in India and ran it for over 40 years. It takes a sustained amount of effort over a long period of time to do something like that.

I’d now also like to ask you some broader, more cultural questions about Databook. You’ve previously spoken about the importance of diversity for a workforce and leadership team. Are there any examples you can share of how a multiplicity of experiences and perspectives has streamlined and fuelled the work that Databook does?

Growing up in London, there really is such a diversity of cultures and ideas. You’ve probably seen that during your time at St Paul’s, looking at how many pupils are not only British, but Indian, Pakistani, maybe African, French – a wide variety. We had boys in our year from Japan and Malaysia. And that was just school, but I stayed in London for university and I was always accustomed to diversity – it wasn’t really unique – I just thought it was normal. We have over 150 people from around the world, from California to Canada to New York to London to Amsterdam to Sweden to India to Sydney. With our employees, we bring in different ideas and promote cultural differences amongst us – for example we celebrate Chinese New Year, Hanukah, Diwali and Eid throughout our offices. That builds awareness, something that not everyone will have experienced growing up in their local regions.

At the beginning of the pandemic, you talked about the importance of ‘serving, not selling’, when approaching sales conversations. This seems to be in line with a general trend towards promoting ‘empathy’ and flexible accommodation that permeated lots of corporate cultures post-March 2020. Now, however, there seems to be a reaction underway to this. As a CEO, do you worry about these reversals and what they might suggest? I think it’s easy to cherry-pick some examples, such as Elon Musk, whose approach is radically different to most others. At Meta for example when they’ve had to make changes and let people go, they’ve done it in a sensitive way. They’ve given people 5-6 months’ worth of salary on their transition out. That’s quite unprecedented in corporate history.

19

“We hope to become a public company at some point, but you’ve got to grind away at these things for long periods of time and we just completed five years so we still have a way to go.”

“Just keep in mind that it’s a long road and there are few opportunities that are quick wins. It requires a lot of iteration, innovation, pivoting, trialand-error, before results come.”

They’re also looking at private placement support, and future alumni communities. There’s a host of things these organisations are doing that haven’t been done in the past. Despite our difficult global market environment, from commodity prices to inflation to interest rates to stock market volatility, I see most organisations being more empathetic with their employees than less. I don’t think it’s transient, and one of the reasons why is that there’s a lot more transparency in corporate communications. This is all for the better. When I started my career, everyone in the company was invited to dial in to listen to the CEO once a month. Now we have Zoom meetings, videos, presentations, Q&As, and internal and external social media channels on a daily and weekly basis. I think there’s a lot going on right now that’s improving how communication and collaboration happens across organisations.

Do you feel that’s true of Databook itself: from before COVID to now, do you feel there’s been a shift in how you’ve been operating? Prior to COVID, we had 10-12 people in our company. Today we’re 150+. So, I don’t think we’re the best bellwether for tracking the larger shifts – you’d need to look at more established, mature companies for that.

I remember my first job: it was a construction internship during one of my summers at St Paul’s. I was working in the Docklands on a civil engineering project to build the Millennium Bridge (which is still there) and I spent most of the summer sitting in a cabin with a chain smoking senior engineer! This was back in the mid-90s, when there was no law against smoking inside versus outside, and certainly no employee wellness programs. You came in, did your work, and left. Flash forward 25 years, and there’s a vast difference in the way things are done. For example, we just made improvements to our health benefits for employees and now offer them support for behavioural

health coaching, therapy and support if they need it. Most companies are now supporting employees much more than ever before. They may not always get it right, but I think we will continue to see even more improvements.

Is there any advice you can give to Paulines who are looking to create a start-up like you did?

I started my first start-up when I was 17 at St Paul’s. It was a web-design agency. Back in the late 90s, there were few websites and for example no arsenal.co.uk – it literally didn’t exist. I took an interest in technology and design and so I started my first company with a friend of mine (not from St Paul’s) and pitched to Arsenal’s Chairman. Unfortunately, we didn’t win that bid but it was my first taste of entrepreneurship and we made some money along the way creating websites and business cards for smaller organizations. I was also involved in the Young Entrepreneurs program at the school. There were about 15-20 of us that decided to do

this. We brainstormed a lot of different ideas and ended up finding a simple arbitrage opportunity – buying Jansport backpacks from Costco for a tenner each and we then sold them to Paulines for 20 quid. Good margins and within six months I think we had about 50% of the school carrying Jansport backpacks, plus we made about £1,000.

My main advice for Paulines who are considering a business is to just try something. I would say that it’s never too late. The average age of getting into entrepreneurship is in the early 40s. It’s not easy but if you have something you’re passionate about and want to create something new and differentiated then it can be a huge opportunity. Just keep in mind that it’s a long road and there are few opportunities that are quick wins. It requires a lot of iteration, innovation, pivoting, trial-and-error, before results come. I’m happy to offer any assistance to folks who might be thinking of an entrepreneurial future, but the best way to do it is by trialand-error and learning on the job.

20 ATRIUM SPRING / SUMMER 2023 THE INTERVIEW

Anand during his time at St Paul’s

China Less Condemnation and More Courtesy

“Has he changed his mind yet?” was the basic tenor of several telephone calls the School made to my parents in late 1976. I had emerged from A Levels with results that surprised me as much as my masters and I was causing mild consternation with my determination to study Chinese at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Even now, more than 45 years later, it is a sad truth that I still find myself swimming against the tide when it comes to China.

A visit to an exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1973 changed my life and opened a door to a world of different understandings of language, art, philosophy, history, human relationships and politics. There are, of course, far more points of similarity and shared understanding between China and the West than there are of incomprehension and irreconcilable difference, but it is always the latter that are highlighted and magnified. As a recognised Sinophile, people might expect that I would mount some kind of defence of the Chinese

government’s actions in Xinjiang, but I cannot and do not. I do understand better than many, the historical and political reasons behind them, but that is to no purpose weighed against the human cost. I am also neither an epidemiologist nor an expert in military strategy so this article will not cover the Chinese government’s handling of Covid or its aspirations regarding Taiwan.

Hong Kong, however, is a major stick currently used to beat the Beijing regime, and is something of a different matter, because there, knowledge of the history of the place, how and why it was “acquired” and how it was run for 90% of its time as a British colony, should give some critics pause for thought.

Staying with history, most Westerners are unaware that for more than three-quarters of the last 2,500 years China has been one of the most powerful countries in the world economy. What has happened over the last 40 years since Deng Xiaoping’s “opening up and reform”, is nothing new. Monopolies on the production of silk, then porcelain, then tea, guaranteed China a dominant place in world trade. The influence of these commodities on national economies and societies was enormous from very early times. The Romans’ taste for Chinese silk (there was no other kind) led to them banning it twice, once on financial grounds because it was

21

PAULINE PERSPECTIVE

James Trapp (1972-76) argues that greater perspective is needed on modern China

bankrupting the Roman exchequer and once on moral grounds because the Senate believed it was corrupting Roman youth. Fast forward some 1,800 years, and the British taste for Chinese tea (there was no other kind) was emptying the British treasury so fast, urgent action was required. The British answer was to create the model for the international drugs trade: produce cheaply in industrial quantities, smuggle into your target country and sell cheap.

The British did this, at the start of the 19th century, using opium grown in British India, with which they flooded China, causing huge damage to the Chinese economy and Chinese society

Some aspects of Chinese attitudes to the West are still coloured by echoes of the Opium Wars and the subsequent attempt by Western powers to carve up China between them to exploit economically. British attitudes in particular are still influenced by the images of the devious, cruel, “fiendish” Chinese common in the British press of the time, starting with the Opium Wars and magnified by the Boxer Rebellion.

More recently, fear of Communism and of Red China undeniably influences the average Briton’s picture. In the mid-2000s I used to lead groups of well-educated, well-travelled Brits on tours of China. Many of them arrived in Beijing still expecting to see crowds of people in Mao suits waving little red books. Within days they had pretty much

as a whole. The enterprise was backed, sometimes reluctantly, by the British government, and proved so lucrative that they sanctioned two wars with China, who had the temerity to object, to cement the drugs trade in place and push for further foreign encroachment. Hong Kong was acquired at cannonpoint at the end of the First Opium War, to ensure a safe harbour for the drugs runners. In order further to undermine the Chinese trading power based on tea, the British also engaged in a form of “industrial espionage” and “intellectual property theft” by sending an undercover agent, a plant hunter called Robert Fortune, into China, disguised as a Chinese, to steal the secrets of tea cultivation and production. The aim was to start a British tea industry in India to undercut the Chinese. Does any of that sound familiar in a more modern context?

It is unfashionable in some quarters, to allow opinions on current affairs to be informed by history because, of course, history was the backward “then” and we are in the much more advanced “now”. Yet we are beset by ongoing national, racial and religious stereotypes and prejudices that hobble attempts at more enlightened international and intercultural relations.

all their preconceptions about the country turned on their heads and by the time they returned to the UK, if not as total China converts, they at least held very different views.

The best way to start understanding China properly is to visit, because so many aspects, its size, its scale, its diversity are impossible to comprehend from the outside. Equally difficult to appreciate second-hand is how it combines social cohesion with a vivid individuality, which most Westerners assume has been squeezed out of the populace by an over-bearing authoritarian regime. Free enterprise and free thinking thrive in modern China but sometimes find different ways of expressing themselves from those in the West. I acknowledge that I am laying myself open to attack as a Brit trying to “explain” China, but I do so with a greater depth of understanding and experience than most.