Table of Contents

00 INTRODUCTION

Course Background

The Community of Claverito

Learning about Community Needs, Desires, Priorities

Study Abroad: Experiencing the Urban + Ecological Context

01 ONE HEALTH CONTEXT

Understanding One Health Issues in Claverito

Climate Change

Waterborne Pathogens

Malnutrition

Parasitic Diseases

Jungle Mosquito Diseases

Food Insecurity

Chagas Disease

Proximity-Related Respiratory Infections

Urban Biodiversity

Urban Mosquito Diseases

Asthma

Leptospirosis

Anxiety and Depression

Falling, Injury, and Drowning

Chronic Disease Risk

Animal Bites and Stings

02 HUMAN SCALE PROTOTYPES

Constructed designs to target One Health issues in Claverito at the family scale

Bamboo Bottles Barge Walkways for Health

The Floating Spring Home Helper Modular Multipurpose Chair

Bamboo Bottles Barge Walkways for Health

The Floating Spring Home Helper Modular Multipurpose Chair

CAUGHT IN THE REEDS

Bio-Floats , Habitat , and Opportunity

03 COMMUNITY SCALE DESIGNS

Conceptual designs to target One Health issues in Claverito at the community scale

04 REFERENCES

Caught in the Reeds: Biofloats, Habitat, and Opportunity

MARKETS)

Camu Camu Healthscape: Unexpected Interactions Between Ecology, People + Place

Food and Medicine Pods: A New Way to Grow!

Women’s Economic Empowerment

(Em)bracing Claverito’s Hillside for Sustainable Community Health

Earthwork! Exploring the Potential of the Hillside

(Em)Bracing Claverito’s Hillside for Sustainable Community Health

Dragonfly Sanctuary: Habitats to Address Mosquito-Borne Diseases in Claverito

The Plastic Program

Lands Acknowledgement

As landscape stewards and advocates for the environment, we wish to acknowledge we learn, live, and design on taken lands. The Penn State Stuckeman School and Department of Landscape Architecture occupy the traditional lands of the Lenape, Haudenosaunee, Shawnee, Susquehannock, and other Indigenous Peoples. As a land grant university, Penn State was granted close to 778,000 acres of Indigenous land from across the present day United States through the Morrill Act of 1862, most of which was sold to fund the University’s endowment. This land was the traditional land of over 112 Indigenous tribes, including the Yakama, Menominee, Apache, Cheyenne Arapaho, Pomo, Ho Chunk, Sac and Fox Nation, and Klamath.

We benefit from and are accountable for our widespread impact on these lands, peoples, and property ownership systems that shape our relations to the past, present, and future.

In addition, in this course, we are benefiting from the past and present Indigenous and urban Indigenous peoples who live in Iquitos, Peru, and in particular, in the community of Claverito. We acknowledge the role the United States and Europe played and continues to play in colonialism, structural racism, and resource extraction that has widespread impacts on the lands and their connection to culture, ecological destruction, health inequity, land insecurity, and more.

We will work hard to not contribute further to these inequities in the context of this class.

Recommended citation for this book: Andrews, Leann, Rebecca Bachman, Olivia Boon, Christopher Coughlin, Thomas Darlington, Keith Faminiano, Parker Kingshipp, Andrew Kuka, Anne Lai, Tegan Lochner, Megan Cherpak, Yael Andrade, Stephen Mainzer, Justin Brown. PennStateLARCH414DesignActivismStudio:DesigningforOneHealthintheAmphibiousInformal CommunityofClaverito,Iquitos,Peru . The Pennsylvania State University. 2023. ISBN: 979-8-218-23594-9.

Acknowledgements

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE STUDENTS

Olivia Boon

Christopher Coughlin

Thomas Darlington

Keith Faminiano

Parker Kingshipp

Andrew Kuka

Anne Lai

Tegan Lochner

ONE HEALTH SCHOLARS

Yael Andrade, M.S., Public / Global Health

Megan Cherpak, B.S., Veterinary Sciences

INSTRUCTION TEAM

Dr. Leann Andrews, Primary Instructor

Rebecca Bachman, Guest Instructor

Alejandra Jhonston, On-Site Coordinator

Xiomara Valdivia, Community Support

Juan Noa Tuanama, Community Liaison

SUPPORT

Hamer Center for Community Design Curriculum Support Grant

Institutes of Energy and the Environment Seed Grant

Penn State Department of Landscape Architecture

ADVISORS TO ONE HEALTH SCHOLARS

Dr. Leann Andrews, Landscape Architecture

Dr. Justin Brown, Veterinary Sciences

Dr. Robert Lennon, Hershey Medical Center

Dr. Stephen Mainzer, Landscape Architecture

GUEST CRITIQUE

Peter Aeschbacher, Architecture / Landscape Architecture

Coco Alarcon, Public Health, Landscape Architecture

Dr. Clarissa Albrecht, Architecture

Dr. Andy Cole, Landscape Architecture, Ecology

Dr. Kristina Hill, Landscape Architecture, Ecology

Dr. Robert Lennon, Hershey Medical Center

Lauren Sosa, Landscape Architecture

Alec Spangler, Landscape Architecture

Dr. Peter Stempel, Landscape Architecture

Dr. Roxi Thoren, Landscape Architecture

We are especially grateful to the residents of Claverito for the warm welcome into their community and their collaborative spirit.

Forward

Dr. Leann Andrews Assistant Professor, Landscape ArchitectureE+D (Ecology Plus Design)

PI, One Health Scholars Program

Penn State

This design activism studio builds upon an existing relationship I and my Peruvian and U.S. colleagues have nurtured with the community of Claverito through the InterACTION Labs program over the last seven years. Through the lens of a real community, this course helps students understand how much of an impact design of the built environment can have on human and non-human life, and that change for the better can happen through informed and inspired design. The work that you see in this studio book tackles a wide range of “wicked problems” that loom in our interconnected global community: climate change, pandemics, species and ecosystems loss, rapid urbanization, fading of Indigenous cultures, informal settlements, and extreme social inequity. This studio also connects to the One Health Scholars program to provide a unique applied and transdisciplinary education opportunity for graduate and undergraduate students in landscape architecture, veterinary sciences, and public health.

While grounded in the realities of the community of Claverito, the design ideas found in this book are to be seen as academic exercises, and the residents have been informed, and reminded, of this throughout the semester and afterward. That said, these ideas are intended to spark conversations, both amongst themselves and with decision-makers and external advocates, on how the community of Claverito sees their future. It is the hope that both vernacular and professional built solutions may evolve from the conceptual ideas of students. It is also the hope that students will carry these skills with them to positively impact the many communities they will encounter in their future careers.

The final design ideas were presented to the community of Claverito on July 16, 2023, and received with excitement, hope, and planning. The results of the hard work of students, the One Health Scholars, the teaching and administration team, and especially the residents of Claverito may be seen with time.

Course Background

COURSE PREMISE

Significant increases in mining, agriculture, and oil extraction and related wildfires in the Amazon Rainforest in the last decade have degraded Amazon ecosystems, spurring mass species loss, interrupting local to global climate regulation, and causing rapid migration of Indigenous peoples to jungle cities such as Iquitos, Peru. With nowhere to go once arriving in the city, the cash poor families find themselves settling in informal slum communities, yet continuing their familiar traditional practices of living on the floodplain in floating and stilted houses. Without assistance with sanitation, water, or infrastructure, the intertwined health of the people, the animals, and the environment — or One Health — suffers. Issues such as chronic diarrhea, infectious and zoonotic diseases, injuries, poor mental health, malnutrition, biodiversity loss, and severe stigma toward their Indigenous roots hinder quality of life.

This studio connects with the informal amphibious slum community of Claverito to address these interconnected health issues through the design of their built environment. This studio also builds upon the InterACTION Labs program, a transdisciplinary action research and training program with partnerships between the Community of Claverito, Penn State, the University of Washington, the Centro de Investigaciones Tecnológicas Biomédicas y Medioambientales, the Universidad Nacional de la Amazonía Peruana Traction, and the National Institutes of Health in both the United States and Peru.

Specifically, students in this studio explored:

One Health. Students learned about interconnections between the health of humans, animals, and the environment and how specific One Health issues can be addressed through the design of the built environment.

Transdisciplinary Collaboration. This course connected to the Penn State One Health Scholars program and students and faculty across the veterinary and medical sciences to stimulate evidence based designs and ideas influenced by different disciplinary perspectives. It also connected with residents in the informal community of Claverito in Iquitos, Peru, through interviews and workshops.

Design Making Across Scales. Students worked with their hands to design practical yet bold solutions at the small household scale, and built upon their skills in prior coursework to design and plan community scale solutions.

Ethics. This course emphasized empathic design, cultural mindfulness, social and ecological responsibility and accountability, and non-Western ways of thinking and making. The travel component emphasized best practices in visiting a non-Western country, sensitive ecosystem, and vulnerable population. Students nurtured individual critical stances and questioning to further their personal design ethics.

COURSE OBJECTIVES

Explore design activism within landscape architecture, and learn about need initiated design as opposed to client initiated design.

Develop an in-depth understanding of how the built environment is a determinant of health for both humans and animals.

Acknowledge your personal biases and backgrounds, absorb non-Western cultures and non academic epistemologies, and design from diverse perspectives other than your own.

Strengthen applied empathy skills and community engagement techniques.

Learn about evidence-based design and the use of research and assessment to increase accountability.

Nurture and expand upon digital, verbal, and written communication and cross-cultural translation skills.

Critically engage in the course topics to nurture personal design stances and ethics.

The Community of Claverito, Iquitos, Peru

Claverito is a vibrant community within a unique “amphibious” floodplain ecosystem that supports the life of 280 people, 240 domestic animals, and hundreds of species of wild birds, insects, fish, amphibians, and reptiles. Claverito is also an informal community and lacks safe water, sewer, electricity, and infrastructure. The community’s extreme poverty and traditional lifestyle are often met with negative stigma from those who live in the upper parts of the city, resulting in trash and construction dumping and a further lack of support and degraded health. Yet, the people’s traditional lifestyle also supports a rich ecosystem and unique riverine culture, both of which are under threat.

All photos except bottom four on this page © Gemina Garland-Lewis; Drone imagery by Kevin Mauro Rodriguez Arce

All photos except bottom four on this page © Gemina Garland-Lewis; Drone imagery by Kevin Mauro Rodriguez Arce

LOW RIVER SEASON

August to December the 53 houses rest on the ground and residents are busy with agriculture, gardening, sports, and revitalizing their houses and infrastructure.

HIGH RIVER SEASON

February to June the traditionally-designed community floats on the river and residents fish, swim, and boat within a rich floodplain ecosystem.

Experiencing the Ecological and Urban Context

Students traveled to Iquitos, Peru for 10 days over spring break to learn about the urban and ecological context in which Claverito is situated.

Learning About Community Needs, Desires and Priorities

Over the course of the semester students gained insight into the community of Claverito in a variety of ways:

1. SURVEY

In February 2023, local team members conducted a survey with residents to understand their daily life.

Resultados

2. GUEST PERSPECTIVES

Students met with community leader Juan Noa Tuanama several times via Zoom and in-person to ask questions and gain insight into community preferences. Students also heard from local designers Gabriela Vildosola, Coco Alarcon, and Rebecca Bachman about physical and health challenges and the data findings of the InterACTION Labs program which has been working closely with Claverito since 2016.

To support interdisciplinary learning, students heard lectures on related One Health topics from Dr. Kristina Hill (ecological design), Dr. Sona Jasani (health of women and babies), Dr. Larry Gorenflo (traditional cultures and biodiversity), Dr. Robert Lennon (riverine community health), and Dr. Justin Brown (human-animal disease transmission). Dr. Andy Cole (ecology and design), Dr. Lauren Sosa (landscape architecture), and Alec Spangler (landscape architecture) also joined the class for design critiques, and our class had a design idea exchange day with Dr. Clarissa Albrecht’s class of architecture students who were working with a lowincome community in Brazil.

In addition, this course connected with the One Health Scholars program. Penn State students Megan Cherpak (veterinary sciences) and Yael Andrade (public health) joined the class to act as human and animal health consultants to the students’ environmental health projects.

3. TOURS

Community members led students on both a walking and boating tour of Claverito in which students could experience the community firsthand. Drone videos from the InterACTION Labs program also offered a helpful perspective of the community throughout the seasons and years.

4. COMMUNITY MEETING

Students presented their initial design ideas to residents, and residents then voted on their favorite ideas. In exchange for their time and knowledge, students co-created a sign at the entrance of Claverito designed to attract tourists and combat stereotypes.

CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS ON HEALTH

In Claverito, Peru

Climate change is the biggest health threat to life on Earth (WHO, 2021).

GLOBAL CAUSES

AMAZON IMPACTS

Spread of infectious diseases

The burning of fossil fuels increases global temperatures. To avoid catastrophic health impacts and millions of deaths, the world must limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C (UN, 2022) (WHO, 2021)

Increased insect infestation

GLOBAL IMPACTS

Species and biodiversity loss due to changing weather, habitat destruction, and invasive species

Drought causing crop loss, ecosystem damage, and lack of water access

Food shortages as fisheries, crops, and livestock are damaged

Extreme weather events and sea level rise threaten ecosystems and communities

Displacement as weather-related events force populations to move (UN, 2022)

Decreased agricultural yield

Degredation of fresh water systems

Soil loss

DID YOU KNOW? Althought it makes up only around of the planet’s surface, the Amazon rainforest is home to 10% of all known wildlife species (WWF, 2022)

Water pollution

Flooding in Iquitos

Increased insect infestation

Infrastructure damage

Flooding causes extensive health effects, including decrease in food production, water provision, ecosystem disruption, and infectious disease outbreak. Longer term effects of flooding include post-traumatic stress and population displacement (WHO, 2022)

WATERBORNE PATHOGENS

In Claverito, Peru

WATERBORNE ILLNESS CAUSES

Waterborne illness is caused by recreational or drinking water contaminated by disease-causing microbes or pathogens. Many waterborne pathogens can also be acquired via contaminated food or beverages, from contact with animals or their environment, or through person-to-person spread (WHO, 2022)

WATERBORNE ILLNESS IMPACTS

Contaminated water can transmit diseases such as cholera, dysentery, typhoid and polio. It is also estimated to cause 485,000 deaths from diarrhearelated complications each year (WHO, 2022).

Personal contact

Undercooked food

Contaminated water

SYMPTOMS

PREVENTION

Wash hands Wash produce Cook meat (WHO, 2022)

(Mayo Clinic, 2022)

Escherichia coli

CHOLERA CAUSES

DID YOU KNOW? In Claverito, water hyacinth reduced E.coli in shallow water to levels deemed safe by U.S. EPA for recreational use. (Rebecca B Neumann, Susan Cilene Paredes Fernández, Leann Andrews, et al., 2022)

Water hyacinth in Claverito

Vibrio cholerae

Possible contaminated water

CLAVERITO IMPACTS

Undercooked shellfish

Contaminated water

SYMPTOMS

• 11% of houses in Belén, had fecal matter in their water from the municipal water company (Faldetta et al., 2014)

• Cholera caused 9,000 deaths from 1991-1993 in Peru (Bachman, 2020)

PREVENTION

Wash hands Wash produce Cook meat

Epidemic (CDC, 2022)

• The United States EPA recommends E. coli stay below 126 CFU/100 ml- Claverito is at levels of 7700 CFU/100 ml (Rebecca B Neumann, Susan Cilene Paredes Fernández, Leann Andrews, et al., 2022)

Drink bottled water if possible to prevent cholera (CDC, 2022)

MALNUTRITION

[MAL·NYOO·TRISH·UHN]

Malnutrition is an imbalance between the nutrients your body needs to function and the nutrients it gets. It can mean undernutrition or overnutrition. You can be malnourished from an overall lack of calories, or you might have a protein, vitamin or mineral deficiency. You might also have more excess calories than your body knows what to do with.

STUNTING SYNDROME

We view this condition as a ‘stunting syndrome’ in which multiple pathological changes marked by linear growth retardation in early life are associated with increased morbidity and mortality, reduced physical, neurodevelopmental and economic capacity and an elevated risk of metabolic disease into adulthood. Stunting is a cyclical process because women who were themselves stunted in childhood tend to have stunted offspring, creating an intergenerational cycle of poverty and reduced human capital that is difficult to break.

DIET PREDOMINANTLY FISH & WHOLE GRAINS

DEFICITES OF VEGETABLES, GRAINS, FATS AND OILS FOR BOTH ADULTS & CHILDREN

SUGAR & GRAINS INTAKE ABOVE RECOMENDATIONS

FISH INTAKE EXCEEDS RECOMENDATIONS

MAIN CONCERNS REGUARD LACK OF CORRECT FOODS

PARASITIC DISEASES

[PARR

· UH · SIT · IK] [DI · ZEEZ · UHZ]

Parasitic disease, in humans, is any illness that is caused by a parasite: an organism that lives in or on another organism (known as the host).

SYMPTOMS

DIARRHEA

BLOATING

NAUSEA

ABDOMINAL PAIN

FEVER

VOMITING

HOW TO PREVENT

ITCHY SKIN

COUGH

VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY

LOSS OF APPETITE

FATIGUE

GROWTH RETARDATION`

WASH YOUR HANDS REGULARLY

BOIL WATER BEFORE DRINKING

WEAR SHOES WHEN OUTSIDE

STAY AWAY FROM SPOILED FOOD

KEEP CHILDREN’S HANDS OUT OF MOUTH

BATHE AS REGULARLY AS POSSIBLE

Percent of Peruvians with Parasites

Percent of Clavarito

Residents with Parasites

Percent of Harmful vs Harmless Parasites in Claverito 66%

Trich (Trichomonas h. vaginalis)

1 Transmitted during sex; not common to infect other body parts

Threadworm (Larva Strongyloides stercoralis)

3 Penetrates bare skin on infested soil, also sheets, clothing, sitting on soil

Hookworm (Uncinarias stenocephala)

2

Exposed skin comes in contact with infective larvae in contaminated soil or grass

Giardia Intestinalis (Giardia lamblia)

4 Fecal Ingestion (food, fecal-oral contact, water)

Whipworm (Trichuris triciura)

5 consume contaminated food, water, ingesting contaminated soil

Tapeworm (Ascaris lumbricoides)

6 consume contaminated soil and water, children playing in soil, soiled toys

JUNGLE MOSQUITO DISEASES

Malaria 1 2 Encephalitis

Vector: Anopheles Mosquito

Symptoms: flu-like illness, chills, headache, muscle aches, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea (CDC, 2022)

IQUITOS CLAVERITO

Vector: Culex Mosquito

Symptoms: flu-like illness, fever, headache, confusion, speech difficulty, lost conciousness (NHS, 2022)

TRANSMISSION CYCLE

AT-RISK POPULATIONS

Children Pregnant Impoverished Rural Limited Healthcare

2-12km, 40-290m above ground

Flight Radius (Kaufmann et al., 2004)

residents travel to visit family, to fish, to claim land for Chakras (farms) in low-river season

20 min. - 2 hrs+ boat ride

~3 2km, 4 7m above ground

Flight Radius (CDC, 2022)

FOOD INSECURITY

Anxiety about food (source, situation)

Insufficient quantity (adults and children)

Closest grocery store “Los Portales” unaffordable

“Mercado de Productales”: place to sell farm products and eat

Reduced intake (adults and children) !

Insufficient quality (nutritional value, preference, diversity)

Consequences of reduced food intake (children and adults)

Feelings of shame for the way food is obtained

Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS)

(Fanta Project, 2007)

Seasonal Chakras

High-River Season

Low-River Season

IQUITOS CLAVERITO

Sitgma as “slum” from city Access carrier: fringe location

Generational poverty Compounded chronic illness cycles Exposure to disease and pollutants

FOOD SECURITY

11 pigs (1 household)

1 pig feeds 50-100 people

157 chickens (14 households)

1 chicken feeds 4 people, ~1 egg/day

12 ducks (4 households)

1 duck feed 2-3 people

InterAction Labs, 2016-2018

HEALTH CONSEQUENCES

Adults: diabetes, high blood pressure, other diet-related chronic illnesses

Children: delayed development, asthma, anemia, behavioral issues, etc.

(Feeding America, 2023)

Low-River Season Chakras

Informal agroforesty farms (family members in jungle)

AMAZON JUNGLE

Anthropogenic climate change will affect supply and diversity of fish

COOKINGG MATERIALS IN CLAVRITOS

ASTHMA

Asthma triggers. Asthma & Allergy Foundation of America. (2023, January 17). from https:// aafa.org/asthma/asthma-triggers-causes/

COAL OR BIOCHAR 25%

FIREWOOD

41% GAS 34%

ALLERGIES EXERCISE

Bachman, R. A. Rottle, N. Reimagining the Amphibious City: From Health Data to Ecological Design in an Amazonian informal community.

OCCUPATIONAL

LEPTOSPIROSIS Transmission

INFECTED WATER, URINE, AND OTHER BODILY FLUIDS OF HUMANS, RODENTS, AND BOTH WILD AND DOMESTIC ANIMALS

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infection of Leptospirosis.

LEPTOSPIROSIS ANTIBODIES

Symptoms

High fever

Headache

Chills

Muscle aches

Vomiting

Jaundice (yellow skin and eyes)

Red eyes

Abdominal pain

Diarrhea

Rash

GREY AREA (FADED ANTIBODIES) 33%

POSITIVE 55%

NEGATIVE 12%

ANXIETY & DEPRESSION ANXIETY & DEPRESSION ANXIETY & DEPRESSION

Age, Gender, and Socio-economic Status

Women, the elderly, and members of minoritized groups are at relatively high risk of anxiety and depression. These groups are especially likely to be targets of abuse, leading to trauma, fear, stress, and subsequent mental health issues (Rondon, 2009).

MAJOR RISK FACTORS

In Iquitos, Peru

Health (Sleep, Nutrition, Exercise, & Illness)

Stress

Environmental stressors like exposure to loud noises, pollution, crowds, and extreme weather/ temperature and social stressors like civic unrest and poverty can contribute to anxiety and depression.

63% 63%

Good physical health, a balanced diet, and adequate rest and exercise are critical in maintaining good mental health. of Peruvians in the Loreto region live below the poverty line, challenging their ability to stay healthy (Loreto, n.d.).

Memories of painful experiences can trigger anxiety or depression. This includes but is not limited to the death of a loved one, physical or emotional abuse, and political violence like that seen in Peru through the 1980’s (Rondon, 2009).

Trauma

(Raza, 2020)

(Kumar, 2018)

(Castaneda, 2022)

(Caretur Loreto, n.d.)

Trauma

(Raza, 2020)

(Kumar, 2018)

(Castaneda, 2022)

(Caretur Loreto, n.d.)

EFFECTS

PHYSICAL

Fatigue, muscle aches, pain gastrointestinal issues, rapid breathing and an increased heart rate.

PERUVIAN ACCESS TO CARE

MENTAL & EMOTIONAL SOCIAL

Sense of impending doom, difficulty focusing, constant irritibiliy or sadness, suicidal thoughts.

“In 2012, just of Peruvians estimated to need mental health services actually received them”

(Icon0.com, n.d.)

Withdrawl from social activity, drug/ alcohol abuse and addiction.

of Peruvians in need of mental health care do not seek help because they lack either information or ability to pay.

12.8% 12.8% Access to Care

Genetics Illness Stress

Socioeconomics Drugs & Alcohol

Claverito

Sleep, Diet & Exercise

(Chang, 2020) (Sadino, n.d.)

Risk factors accumululate, and become overwhelming.

Severity of Anxiety (GAD-7)

2018-19

Severe

Severity of Depression (PHQ-8)

2016-19

Severe

Moderately Severe

None

Moderate

None

Moderate

Minimal

Mild

Mild

FALLING, INJURY, & DROWNING

Environmental Hazards

FALLING, INJURY, & DROWNING In

Conditions in amphibious communities including: unmaintained and slippery paths, muddy or uneven ground, animals, and thick vegetation can lead to falls, injury, and drownings.

Access to Care

Wounds from falls and injuries risk bacterial infection. This risk is especially high where there is limited access to clean water and medical care.

Iquitos, Peru

Economic Situation

63% 63%

Major Risk Factors

of Peruvians in the Loreto region live below the poverty line (Loreto, n.d.). When injured, they may still be compelled to work or go without meals or other necessities.

Safety Standards & Informal work

Age & Health

Children, the elderly, and those with mobility issues

Managing Risk with Updated Infrastructure

Claverito

A newly constructed staircase connecting Claverito and downtown Iquitos substantially reduces risk of falling and injury.

Falls & Injury on Staircase

3 months Before/After New Construction (2016/17)

Continuing Risk

Claverito’s floating paths continue to present a tripping hazard. Risk of injury is compounded by the garbage and bacteria rich riverwater just below the path.

Falls & Injury on Floating Path in 2

Months (2018)

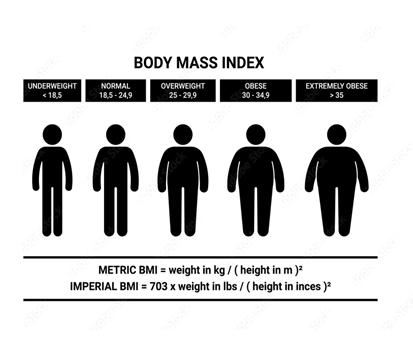

Chronic Disease Risk

Root Causes

. Lack of Medical Resources

. Environmental Dangers

. Unclean Environment

Blood Pressure

Glucose Levels

80 Beats Per Minute Heart Rate -

Less than 140mg/dL mmHg <

120 80

Out of Normal Range Could Cause Stroke, Heart attack, Other Diseases

Mayo Clinic 2023 - https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/high-bloodpressure/symptoms-causes/syc-20373410

Data from Professor Andrews Study

APR 2017 FEB 2018 JUL 2018

Low Glucose Levels

“This can lead to blurred vision, difficulty concentrating, confused thinking, slurred speech, numbness, and drowsiness.”

American Diabetes Association - https:// diabetes.org/healthy-living/medication-treatments/ blood-glucose-testing-and-control/hypoglycemia#:~:text=This%20can%20lead%20to%20blurred,coma%2C%20 and%20very%20rarely%20death.

9% High 5% High 10% High

Claverito Blood Pressure Data

High Glucose Levels

“Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) – a condition caused by the body needing to break down fat as a source of energy, which can lead to a diabetic coma; this tends to affect people with type 1 diabetes”

NHS INFORM, 2023 - https://www.nhsinform.scot/ illnesses-and-conditions/blood-and-lymph/hyperglycaemia-high-blood-sugar#:~:text=Very%20high%20blood%20sugar%20 levels,people%20with%20type%201%20diabetes

Claverito Glucose Data

APR 2017

62% Have High Glucose

Claverito Body Mass Index

Data

Data from Professor Andrews Study

Healthy Weight

Spiders

Animal Bites and Stings

Root Causes

. Close Proximity to wild animals.

. Daily interactions with animals

. Hunting and eating animals

Piranhas

. Teeth Replace in Quarters

. Will Only Attack if Provoked

. Attracted to Noise, Blood, and Splashing

Helen Thompson, 2014

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/14-fun -facts-about-piranhas-180951948/

Some Build Webs

Around Trash

Some Live on the Wood Planks

Bird Watching HQ, 22 Common Spiders

Found in Peru

https://birdwatchinghq.com/spiders-of-peru/

Dog Bite Care

Text From Stephanie Watson, 2022, Fetch By Web MD, https://pets.webmd.com/dogs/dog-bites

Eats

Mosquitoes

Some Species

Bites Hurt Bad

Insects

1169 reported species of wasps in Peru.

Zookeys, 2009

Use card to scrape out Stinger not tweezers

Snakes Cats

Iquitos

Map From Chippaux, Jean-Philippe , 2017. Found on Research Gate - https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Geographical-distribution-of-incidence-of-snakebites-in-Peru-2000-2015-Guillermo-Romero_fig12_317820265

Eels

Up to 2 Meters +

20Kg

Jaguars, Pumas, Ocelots

Bartonella henselae Infection - (CSD) Cat Scratch

Feral and Domestic Cats

Ripple Effects

Disease. Could cause a fever, headache, and poor appetite in people.

CDC, 2020 - https://www.cdc.gov/ healthypets/diseases/cat-scratch.html

. Can Cause Illness or Death, Resulting in Trauma for the Community.

. A Continuous Threat, Could Cause Anxiety

Tadashi, 2022, Facts.net - https://facts.net/electric-eel-facts/

Produce 860 Volts

Electricity

Lives in the Amazon River

02 HUMAN SCALE PROTOTYPES

Constructed designs to target One Health issues in Claverito at the family scale

BAMBOO BOTTLES BARGE

THE BAMBOO BOTTLES BARGE THE BAMBOO BOTTLES BARGE

EXISTING CONDITIONS

Injuries from Falls: ~74% of residents report falling on the floating path. Rainy weather amplifies slipping risks.

Trash Pollution: Collected from upstream, the city, and the neighborhood, this increases disease transmission and reduces the aesthetic quality of life.

Waterborne Pathogens: Contaminated water (particularly from fecal matter) increases prevalence of cholera, dysentery, typhoid, and polio.

PROPOSED PROTOTYPE

Bamboo: Used for increased scarcity of Topas

Safety Edge Fencing: Found in community

Twine: Tying (rope, belts, etc.) common way of securing; sealed with wax for durability

Plastic Bottles: Abundance of trash (upstream and city)

Low River Season High River Season ~60cm

1. TRASH COLLECTION 2. FRAME CONSTRUCTION

Construction does not require the use of power tools. Instead, fishmouth cuts are paired with combinations of cross joints, lateral joints, and corner joints, and bound together with clove hitch knots, square, and cross lashing.

Storage Access

Upstream collection of trash using fishing nets and Camu Camu trees during high river season, in addition to community collection during Mingas. x 2

3. WALKWAY

For a 1m pathway segment, both sides together hold ~500 plastic bottles.

Bamboo has a tensile strength of ~60 pounds per meter. The direction of the split bamboo (perpendicular to foot traffic) and a guard rail mitigate slipping and falling risks.

Testing dead and live weight buoyancy!

Prototype on land holds >300 pounds!

Prototype on land holds >300 pounds!

MODULAR PATHS: WALKWAYS FOR HEALTH

Modular Paths: Designing Walkways for Health

Construction Harvest Trim Shape Lash Assemble

1. Layering bamboo gives the path more bouyancy and traction.

2. Native floating vegetation adds biodiversity and creates habitat.

3. Verticle poles lock the modular paths into one plane of motion.

4. Bamboo frames the vegetation neatly, provding a sense of order and adding aesthetic value.

5. Horizontal poles prevent the path from touching the ground in the low river season, resulting in a slower decomposition rate.

Expected Health Outcomes

Reduce Trips and Falls

Building new stable paths with better traction can help reduce trips and falls in the community. Many community members do not have access to healthcare, leaving them at risk of more extreme injuries after a fall.

Decrease Waterborne Pathogens

Floating plants absorb bacteria in the water, reducing E.coli and Cholera. Cholera levels in Claverito are at 7700 CFU/100 ml.

This is over 6,000% more than reccomended by the EPA.

Decrease Vector-borne Dieases

Vegetation provides habitat for mosquito predators such as frogs and dragonflies. This aids in reducing their population in the

community resulting in a lower chance of people contracting vector-borne diseases.

Increase Biodiversity

Increased vegetation will establish habitat for more animals such as frogs, spiders, dragonflies, and butterflies.

Decrease Depression and Anxiety

The new path system will allow people to leave their homes during inclimate weather, reducing social isolation. Additionally, it will increase

the safety in their community, resulting in a decrease of environmental stressors.

Leptochloa scabra Gramalote

Leptochloa scabra Gramalote

La Primavera Flotante

The Floating Spring

The Floating Spring IQUITOS

The capital city of the Maynas Province and Loreto Region, and home of our prospective clients: the residents of Claverito. Locationally positioned where the ever-growing oil industry along with an accumulating amount of trash plague the bordering water of the Amazon river, the call for a One Health mindset could not be more apparent. Many communities, both amphibious and not struggle with this lack of access to potable water but nowhere is it felt more than in the floating slums that border the city itself. The pressing question then becomes, how do we change this?

WHICH ASPECTS OF HUMAN HEALTH ARE ADDRESSED?

-Any access to clean water is a highly valuable resource with numerous positive health effects

-Parasites such as Whipworm, Tapeworm, and Giardia intestinalis are highly prevalent and are commonly contracted through access to contaminated water

-The design caters to the fluid and moving existence of the rest of the community with easy means of transportation

-With a shortened trip needed to collect water, different community members have more time to tend to other responsibilities

-With health risks such as chronic diahrea plaguing the community, the new access to cleaner water aims to better the health situation for everyone

-The materials used in the design are intended to be easily accessible for the community of Claverito, therefore, making the construction a realistic possibility

BUCKET FILTER

HORIZONTAL SUPPORT SLATS

VERTICAL TOWER BEAMS

TRANSFER HOSE

WATER COLLECTION JUG

WATER SPICKET

WATER PUMP

WATER PUMP MOUNT

CLEAN WATER/ DRINKING WATER

LACK OF STANDING WATER (MOSQUITOS)

THE FLOATING SPRING

SEPERATED FROM HUMAN HOUSING

ABILITY TO USE RIVER AND RAIN

INCOME (FROM LEFT OVER WATER)

SUPPORTED PLATFORM

HUMAN HEALTH

ECOLOGICAL HEALTH

ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH

TOWER FOOTPRINT STABILIZERS

STANDING DECK

FLOATATION BINS

The Design

With floating platform, tower support, water collection, bucket filter, and water pump elements present within this design the detail can’t be questioned. What can and should be questioned however is the effectiveness of the design itself. As separate elements, the design would be incomplete with only fragments of what is needed by the community. It’s not until you bring them all together and position them within the community that their impact would be free to grow.

HOME HELPER

Home Helper

a kit of parts

an aid to every family

Health Benefits

Eels

Injuries/ Falls

Water Hazards

Reduced Eel Stings

Reduced by up to 25 persons monthly using rope fence

Reduce drowning of children and elderly

Sun and Rain Cleanliness

Community Formalities

Celebrations

Model overlay on an individual house - Showing scale in context

Protect against by using umbrella or tarp top

Organize clothes and trash

Grid and unify homes with same start kit pole

Decorate and enjoy any holiday

Organization

Hang tools, and wires

Activities

Attach soccer net or basketball net

Mental Health

Gathering space, community engagement, unity and identity, individuality, recognition

Multiple models in community showing connections and how they work together.

SILLA MODULAR: MODULAR MULTIPURPOSE CHAIR

Disease

Microplastics

Habitat Loss

Foodchain Disruption

Disease

Microplastics

Recreational Space

Foodchain Disruption

Mental Health Impacts

Habitat Loss

Microplastics

Foodchain Disruption

Species Loss

03 COMMUNITY SCALE DESIGNS

Conceptual designs to target One Health issues in Claverito at the community scale

CAUGHT IN THE REEDS

Bio-Floats , Habitat , and Opportunity

WHATS THE GOAL?

This project’s main goal is to propose a possible option for solving the main problem of the sinking houses of Claverito. By focusing on subjects such as Mental health, Physical health and One health as a practice, the following culmination of information and grafics seeks to give an understanding of both the construction and installation of the design, along with an in

depth dive into the possible effects upon the community itself the design could have. With focuses ranging from habitat growth for fish and other animals within the community to Para-sympathetic responses to design, this proposal’s main goal above all else is to better the lives of those who live within and are directly affected by the community of Claverito.

FLOTATION PULLEY SYSTEM

(SISTEMA DE POLEAS DE FLOTACIÓN)

THE PULLEY SYSTEM ALLOWS FOR THE PLACMENT AND REMOVAL OF FLOATS AS NEEDED FOR DRYING

PONTOON CONSTRUCTION PROCESS (PROCESO DE CONSTRUCCIÓN DE PONTONES)

COSECHA DE LAS CAÑAS

HARVEST THE REEDS

CONSTRUYE EL MARCO BUILD THE FRAME

INSERTAR LAS CAÑAS

INSERT THE REEDS

ATARLOS JUNTAS TIE THEM TOGETHER

INSTALAR INSTALL

TOTORA GROWTH & HARVESTING (CULTIVO Y COSECHA DE TOTORA)

2,100 LBS (952.5 KG) OF WEIGHT IS DISTRUBUTED BY EACH PAIR OF BIO-FLOATS

1466 REEDS ARE REQUIRED FOR ONE HOUSE TO HAVE A SUFFICIENT AMOUNT FOR INSTALATION

15m2

OF LAND IS REQUIRED TO SUPPLY ENOUGH REEDS FOR ONE HOUSE’S BIO-FLOATS

1 HECTARE WILL SUPPLY ENOUGH MATERIAL TO FLOAT 6.5 HOUSES

8 HECTARES

WOULD BE REQUIRED TO SUPPLY THE ENTIRE COMMUNITY WITH SUFFICIENT REED PRODUCTION

EACH SECTION WILL BE HARVESTED WITH THE RISE AND FALL OF HIGH AND LOW RIVER SEASON

IMPLEMENTATION TIMELINE (CRONOGRAMA DE IMPLEMENTACIÓN)

1 2

BEGIN CONSTRUCTION OF FLOAT ATTATCHMENTS

IMEDIATETLY IN PREPERATION FOR USE

LOW POINTS (PUNTOS BAJOS)

PLANT THE REEDS IN FLOODPLAIN AS WATER

LOWERS TO GAIN THE MAXIMUM AMOUNT OF GROWING TIME

TODAY (HOY) PLANT THE

HIGH POINTS (PUNTOS ALTOS)

HARVEST THE REEDS (COSECHAR LAS CAÑAS)

REEDS (PLANTAR LAS CAÑAS)

3 4

HARVEST THE REEDS FOR USE IN FLOAT MAKING AND DRY FOR 15-20 DAYS IN DIRECT SUNLIGHT

MAKE THE FLOATS (HACER LAS FLOTADORES)

FASHION DRIED REEDS INTO FLOATS READY FOR USE AS SOON AS POSSIBLE

MENTAL STRAIN / SURVIVAL MODE (TENSIÓN MENTAL / MODO DE SUPERVIVENCIA)

LOW STRESS HIGH STRESS EXTREME STRESS

WHAT DO WE DO?

Stress is often much stronger of a feeling than we give it credit for. As one of the leading causes of heart attack and stroke here in the US, its physical and longe-term effects are not to be played with. But what does it look like for the habitants of Claverito, who are living in a prolonged state of stress everyday? Effecting everything from fertility to digestion, the levels of stress we experience shape how we live. The choice then becomes how you will react.

FISH HABITAT (HÁBITAT DE PECES)

ACARAHUAZÚ

MAX LENGTH: 45.7cm FRESHWATER

PREFERS SAND AND MUD BOTTOMED CANALS

PAICHE

MAX LENGTH: 450cm FRESHWATER

OBLIGATE AIR BREATHING FISH

PIRAÑA

MAX LENGTH: 50cm FRESHWATER

PREFERS TO FEED AT DUSK AND DAWN

ABRAMITES

MAX LENGTH: 14cm

FRESHWATER FEEDS ON INSECTS AND PLANT MATTER

INCREASED HABITAT PROVIDES EASIER ACCESS TO FISHING CLOSER TO HOME

BOTH ECONOMIC AND HEALTH OPPORTUNITIES ARE HIGHTENED WITH EXTRA FISH

CAMU CAMU HEALTHSCAPE

Improving health through unexpected interactions between ecology, people, and place.

Camu camu is a small floodplain tree native to the Amazon region. Berries on the tree are highly sought after, both within the Amazon region and further abroad. Claverito currently maintains a robust and resilient camu camu patch within its community that is cared after by a few key residents. This patch of camu camu is an untapped resource that residents have the opportunity to capitalize on. Expanding the bosque, scaling up fruit production, building light landscape interventions, and introducing seasonal programming can create the basis for a thriving environment and economy.

It is estimated that roughly 120,000 people live within the urban floodplain (InterACTION Labs). Once proven to be successful, Claverito may act as a model for other floodplain communities to follow. This project explores how minimal changes to the landscape with readily available materials can eventually lead to large scale improvements in health across the city of Iquitos.

GOALS:

1. Improve the mental and physical health of residents of Claverito.

2. Increase biodiversity within Claverito to reduce vulnerability to disease and environmental disturbances.

3. Establish a self-sustaining economic system for residents to further expand.

4. Create a framework that can be scaled up for other floodplain communities.

Iquitos

Iquitos

CAMU CAMU BERRY

Medicinal Properties:

Antioxidative

Antiinflammatory

Antiobesity

Hypolipidemic

Antihypertensive

Antidiabetic

Camu camu berries are harvested in large baskets by boat right before the peak of the high river season.CAMU CAMU IN TRADITIONAL MEDICINE

Camu camu is widely used in traditional medicine in the Amazon region.

• Arthritis

• Diabetes

• Hypercholesterolemia

• Bronchitis

• Asthma

• Atherosclerosis

• Depression

• Flu

PROCESSED CAMU CAMU

• Gingivitis

• Glaucoma

• Hepatitis

• Infertility

• Migraine

• Osteoporosis

• Parkinson’s disease

• Malaria

Camu camu patches should be large enough to support different animals along the edges and deep within the bosque.

Healthy tree populations have the potential to produce up to 12.7 metric tons of fruit per hectare.

Productive

Legend

Existing Camu Camu Bosque

Proposed Expansion of Camu Camu Bosque

Floating Pathway

Way-finding

Harvest for Food

Harvest for Planting

Maintain Habitat

Bird Watching Tower

AERIAL VIEW OF CLAVERITO AND THE CAMU CAMU BOSQUE

The current bosque produces about 30,000 berries during a good harvest.

80 berries makes 5 gallons of camu camu juice which can then be sold in the local market.

MAINTAIN PROCESS

Berries that are not harvested provide plentiful food for birds and fish.

MAINTAINING HABITAT AND ENHANCING BIODIVERSITY

1. Increased levels of biodiversity can increase the Knowledge, engagement, perception, and curiosity of nature within a community..

2. Urban biodiversity ensures the access of plants and animals to communities who practice traditional medicine. Over 80% of the world’s population uses traditional medicine as their primary form of healthcare.

3. Less biodiversity increases vulnerability to shocks and disturbances. It can also lead to the emergence of new infectious diseases.

4. Good biodiversity maintains an equilibrium between predators and prey, hosts and vectors, and parasites in plants, animals, and humans.

Amphibian fuliginosa Speckled Worm Lizard

Helicops angulatus Brown-banded water snake

Dendropsophus triangulum Triangle Treefrog

Dendropsophus haraldschultzi Many-lined Treefrog

Dendropsophus leali Plain-colored Treefrog

Coragyps atratus Black vulture Jacana jacana Wattled jacana Sternula superciliaris Yellow-billed tern

Psarocolius angustifrons Russet-backed oropendola

Sporophila castaneiventris Chestnut-bellied seedeater

Amphibian fuliginosa Speckled Worm Lizard

Helicops angulatus Brown-banded water snake

Dendropsophus triangulum Triangle Treefrog

Dendropsophus haraldschultzi Many-lined Treefrog

Dendropsophus leali Plain-colored Treefrog

Coragyps atratus Black vulture Jacana jacana Wattled jacana Sternula superciliaris Yellow-billed tern

Psarocolius angustifrons Russet-backed oropendola

Sporophila castaneiventris Chestnut-bellied seedeater

Species documented in Claverito by InterAction

SEASONAL RECREATION

Way-finding poles are tall enough to be used in the high river and low river seasons.

Boat tours through the community, bosque, and surrounding floodplain communities create a steady revenue stream for community members.

Low river season is prime for fishing

Bird-watching towers can be used in the high river and low river seasons.

Parts of the bosque completely dry out during the low river seasons. This allows people to run, walk, and relax amongst the trees.

ANNUAL HARVEST FESTIVAL

Luminescent paint will provide way-finding in the dark.

Lanterns shaped like the camu camu blossom will float throughout the community. Pink light will create visibility after sunset but does not attract disease ridden mosquitoes.

People from all over Iquitos will come to Claverito to celebrate the bountiful harvest. The festival will give community members a vibrant event to look forward to during the high river season.

MATERIALS AND SUPPLIES

Camu Camu Trees

Wood Paint

Boats

Small Pots

Juice Container

HEALTH IMPACT

Decrease water borne pathogens

• Floating plants absorb bacteria in the water, reducing E.coli and Cholera. Cholera levels in Claverito are at 7700 CFU/100 ml. This is over 6,000% more than recommended by the EPA.

Increase Biodiversity

• An expanded bosque doubles the habitat and resources available for animals allowing their populations to grow and thrive.

• Increased biodiversity acts as a buffer against disease, environmental disturbances, and climate change.

Increase Access to Food and Resources

• Creating a steady source of income will reduce anxiety about obtaining food and feelings shame in the way the food is obtained.

Decrease Malnutrition

• Increased incomes can help community members buy food with higher nutritional quality in higher quantity.

• A surplus of camu camu berries ensures that everyone in the community has access to the berry’s high nutritional value.

Decrease Depression and Anxiety

• Hosting a vibrant festival during the peak of the high river season can change the feelings of isolation, depression, and negativity that persist around that time of year.

Estimated 120,000 people

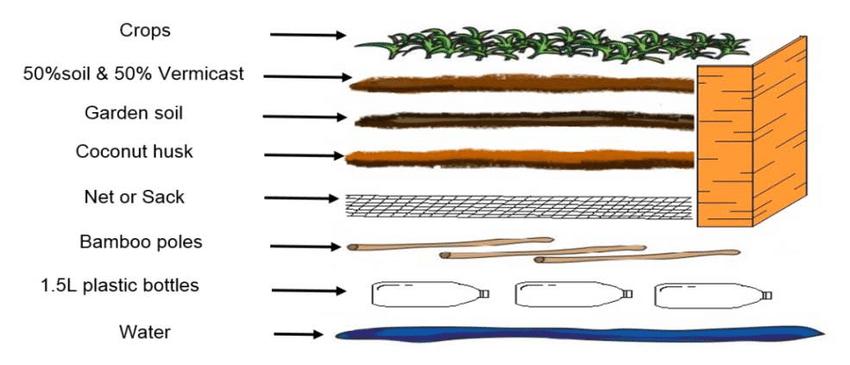

FOOD AND MEDICINE PODS

A new way to grow! Section

This model has two side gardens, two chicken coops, a walkway, and a fishing hole

Dry Season Wet Season

Layout Wet Season Layout Dry Season

Goals

Precedents and the Science Behind the Concept

Garden Study One

(Research Gate)

Both ideas can be tested and merged to see which works best

Garden Study Two

(Research Gate)

Harvest and Seeds

. Harvest by boat during wet season

. Seeds compacted into dirt balls and placed in soil for growth

. Adapted as needed to fit area

(Global Center on Adaptation)

(Bangladesh Study)

(Bangladesh Study)

(Bangladesh Study)

(Global Center on Adaptation)

(Bangladesh Study)

(Bangladesh Study)

(Bangladesh Study)

More Research

Historical Precedent - Aztecs

Example in India

Halfway across the world, with a different culture, these gardens still happen. It shows how important floating agriculture is to humankind.

Lake Titicaca Reed Islands Study in Peru

Highlights that this practice has been done for many years. It has been tried and tested by many tribes, including the Aztecs

Climate Map - Same Climate as Precedents

A recent study done in the Andes Mountain Region of Peru. Shows that floating gardens work today.

All of the precedents are in the same climate as Iquitos Peru

Design Adaptability To Fit Community Needs

Radial Dry Season Option

Linear Option

Option that uses less materials if there is a shortage

Hexagonal Garden Option

Good for smaller spaces

Alternative

Material Options

Wood Pallets

Recycled Tires

Bamboo Growth Timeline

Quick regrowth for a sustainable design

(Adapted from Lewisbamboo.com) (Amazon) (Greenball)

How the Floating Gardens are Helping with Food Security in Claverito

Will assist in feeding the community of Claverito

Medical gardens are present. Nutrition needs will also be helped. There is also the benefit of beauty, green space, and exercise that will come with the garden care

Selling food will assist with economic growth

The gardens will help the local ecosystem by adding vegetation and creating animal resting spots on the water

The floating gardens can catch trash and other debris keeping it from the homes of Claverito. The goal is to clean the water with the extra water lilies

The people of Claverito will learn how to produce food in a new way. They will be able to teach others about responsible food consumption and ways to reduce waste

The city of Iquitos will eventually reap benefits from the gardens as well. They can use similar ideas elsewhere and build a large agricultural industry

By becoming a farming community, the goal is for Claverito to gain recognition from the city and to lessen the current inequality the community faces

One Health Benefits

Data shows the current state of Claverito is that of moderate to severe food insecurity. A problem that desperately needs a solution

Current Malnutrition Stats

Current data shows that many residents are overweight or obese. The goal is for the gardens to help bring access to healthier food.

Animal Species that Benefit From the Gardens

Cant Have One Without the Other

77 bird species around Claverito Many fish swim the Amazon River

The needs of the people of Claverito is very important. These gardens will reduce hunger, will provide an economic opportunity, and will hopefully provide future opportunities with the city of Iquitos

14 species of reptiles and amphibians documented around Claverito

11 Species of butterflies and beetles around Claverito

Gardens will add biodiversity and fill in vegetation gaps in the area

Many local animal species will benefit either directly or indirectly from the presence of the floating gardens

Economic Benefits

Dimensioned floating garden for calculations in Meters

Family run food carts and stands

About 48 chickens per pod (24 in each coop)

48 eggs daily. Thats

336 eggs per week!

Varies based on type of fish. Potential for large quantities raised (100s)

Approx 42 square meters of garden space per pod

Collaboration with the Belen Market

Large variety of food sold

Great economic opportunists at the market

Lots of natural medicine for sale

WOMEN’S ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT

Claverito | Iquitos | Peru

Project Focus

The Indigenous, amphibious community of Claverito experiences extreme poverty and public neglect from the City of Iquitos, resulting in limited ability to address human health and environmental concerns (Andrews et al., 2022). Women experiencing poverty in the Loreto region, especially those of Indigenous descent, face greater barriers in accessing healthcare and economic opportunity (Shannon et al., 2017). This project aims to provide a sustainable model of income generation, so the women of Claverito can have the freedom to make decisions about the health of their community and the built environment.

Women’s OneHealth in Claverito

Poverty, Gender, and Health

Community members surveyed by InterACTION Labs in 2022 reported economy, access to healthcare, and support for youth amongst the top ten things that would improve the quality of life. Women in the Loreto region have less access to economy and healthcare, making them a key population for a targeted intervention (Shannon et al., 2017).

ONE HEALTH ISSUES

- Indigenous women in the Peruvian Amazon are more disadvantaged in accessing healthcare (Shannon et al., 2017)

- Without access to healthcare, water-borne pathogens and parasitic diseases spread unregulated between humans and animals

- 5,211 pieces of solid waste, like plastic bottles were collected in June 2022 (InterACTION Labs, 2022)

- Plastic waste disrupts ecological cycles and breaks down into toxic microplastics, which poison and choke fish, people, and animals

- Trash in the community affects the mental health of residents and perpetuates harmful stereotypes

- Diet is mainly fish and whole grains

- Deficit of vegetables, grains, fats, and oils and sugar, grains, and fish intake exceeds recommendations (InterACTION, 2015)

- Previous edible garden intervention damaged by acid wash dumped on the hillside

- Women in Claverito (and globally) carry out 2.5x more unpaid labor than men, like caretaking, cleaning, and cooking (UN Women, redistribute unpaid work)

- There is little time left over for economic earning, leaving women financially dependent on partners and family members

- Peru has some of the highest global rates of gender based violence (Shannon, 2017)

Under water

A large driver of health issues is polluted water quality. The community is running out of topas, or floating logs, to keep their houses afloat and out of water. Alternative solutions cannot be obtained without outside intervention or economic stimulation.

IQUITOS

1 Terraced Community Garden

2 Women and Family Center

3 Stabilized Path

4 Age 3-6 Play Space

5 Age 6 and Up Play Space

6 Raised Wall

7 Plaza Clavero

Project Goals

1 Generate an internal economic system for women

2 Provide space for working while caretaking

3 Protect the ecosystem and stability of the hillside

4 Foster purpose, confidence, and leadership in women

5 Create safe play space for year-round use

6 Promote food sovereignty

Women and Family Center

SUSTAINABLE INCOME SYSTEM

The ultimate goal of women’s economic empowerment is to enable women to make decisions (Gates Foundation). This system brings economy inside of the community, instead of outsourcing to Iquitos for day labor, as is typical for Claverito residents.

Women and Family CenterLearn and Work

The center provides a space for women to work and learn about economic empowerment and the traditional craft of weaving chambira.

Minga Peru- Community Partner

Minga is a nonprofit organization based in Iquitos that runs female leadership programs, as well as handicraft training workshops.

Chambira Palm- Resource

The chambira palm (Astrocaryum chambira) is native to the Amazon rainforest and can be harvested sustainably for it’s fiber, fruit, and medicinal purposes (Larson, 2019).

4

Market- Profit

Chambira crafts, like baskets and bags are commonly sold in Iquitos to tourists. One article reported women making as many as 15-20 baskets/month, earning $10 each (approx. $14 today) (Guel & Penn, 2009).

RENDERED PERSPECTIVE OF FAMILY CENTER

Terraced Community Garden

Sustainable

Mental Health Improvements Pre and Post June 2018 Garden Intervention

Adopted from InterACTIONLabs, 2016

Health Benefits

1 Accessible produce and medicine

2 Nutritional value

3 Ecological habitat

4 Water runoff purification

5 Reduce anxiety and depression

- The palms of the Amazon rainforest are greatly ecology

- The chambira palm is already promoted as a method agroforestry, given its rapid growth and availability

- Women in developing countries are almost half of sustainable agricultural management, making socially viable target demographic for the chambira (Vilcarromero, 2023).

Chambira fibers drying

Hillside Garden (InterACTION Labs, 2016)

Sustainable Agroforestry

important to local method of sustainable availability the workforce them an already chambira industry

Harvesting- Rule of Thirds

One study reported methods of sustainable chambira harvesting. One Indigenous woman recommended the following:

- Harvest from palms that are at least 3 years old

- Avoid palms that have 3 or less leaves yet/have been harvested from 3 times

- Leaves are ready to be harvested again after 3 months

Chambira Palm Tree

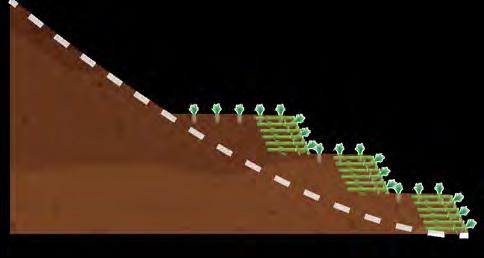

Earthwork!

Exploring the Potential of the Hillside

Settling on the Amazonian floodplain proposes a variety of health concerns, from water-borne pathogens and vector-based disease to food insecurity and mental illness. Compounded by Wicked problems like resource scarcity and the Topography of Wealth, these issues present themselves in the infrastructural conditions of Claverito as sinking houses and a degraded hillside. Embracing the topographic qualities of the neighborhood through strategic manipulation accentuates the hillside’s potential for improving the quality of life, and provides opportunities for municipal recognition.

Sinking Houses

Poverty (Global South)

Resource Scarcity

-unreliable source (Topas)

-preserve vernacular building approaches

-structural instability

-contact with contaminated water

Globalisation

Topography of Wealth

-stigma from Iquitos

-low elevation

Respiratory Health

Mental Health

Cardiovascular Health

Degraded Hillside

-trash dumping

-erosion

-underuse

Reproductive Health

Health Issues

Food Insecurity

Malnutrition

Vector-Base Disease

Colonial Imperialism Floodplain Settlement Water-Borne Pathogens Injury from Trips and FallsCOMMUNITY CENTER & SEATING

HILLSIDE WATER FILTRATION

DECORATIVE PLANT NURSERY

AGROFORESTRY

FLOODED CHANNELS AND WALKWAYS

1

FLOODED CHANNELS AND WALKWAYS

Construction Phases

1 - High River Season: push houses into water ~90m

2 - Low River Season: cut and fill earth

3 - High River Season: return houses to float above channels

4 - Low River Season: fill and finalize pathways

Channel Wall Details

92.5m

Filled Earth

Flex Mechanically Stabilizied Earth Wall (FlexMSE, 2023)

-geobags twice as durable as concrete, 97% less GHGs in installation

-high settlement tolerance

Staked Brush Mattress

-further weathering control

-foster riparian habitat

Preserving Topas

Approximate Dimension Details

Separate topas from decomposing micro-organisms on the ground in order to reduce replacement

Full submersion in water

RAMMED EARTH RETAINING WALLS

Sustainable Construction Capacity Building

Wood cap for protection and seating

Leftover formwork for strength and emergency building supply

Gravel (dumped from construction)

Silt (riverbed)

Clay (existing soil)

Erosion Control

HILLSIDE WATER SOURCE

Layers

Applications

Seating (around community center)

Pathways for walking on hillside

Planter boxes

Water filtration containers

Diseases from Contaminated Water (Boon, 2023)

Cholera E.Coli

Gravel

From hillside tapping and collected rainwater

Wood cap for protection and seating

Different water purity levels for different puposes

Silt (preferably sand)

Charcoal

*May need sheltered protection from leaves, etc.

Sunken foundation of wall to replace concrete footing Moist earth mixture compacted with tamper added, process repeated until finishedDECORATIVE PLANT NURSERY (TO SELL IN MARKETS)

Calathea lancifolia

Canna sp.-achira

Cymbopogon citratus

AGROFORESTRY 5

Heliconia acuminata

Patiquina jaspeada

Spathiphyllum cannifolium

Trees for Topas

Plants for Food Cocona

Sloped for extra flood prevention

Charapita Pepper

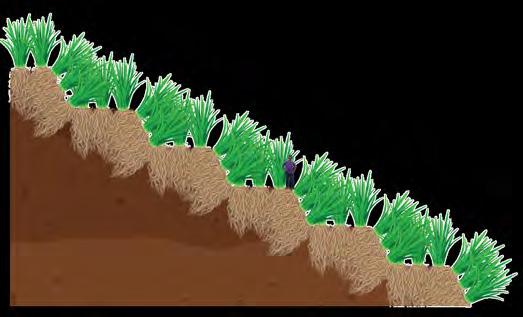

(Em)bracing Claverito’s Hillside for Sustainable Community Health

The people of Claverito are currently facing serious immediate and long-term challenges. A scarcity of topas and other building materials is leading to sinking homes. The pollution and erosion of the nearby hillside is harming plant and animal life and threatens an eventual collapse of the plaza above, cutting off safe access to the city. While protecting the hillside from further damage is paramount for the survival of Claverito, exploring the unrealized potential of the hillside may also hold the key to community flourishing. Terracing supported first by bamboo retaining walls and then by plant life has the potential to protect the hillside from further erosion while creating space needed for the growing and harvesting of useful food, herbs, and timber.

DUMPING HARMS ECOSYSTEM & BEAUTY

• Chemicals dumped on-site have killed plantings and degraded the soil.

• Litter attracts insects, and may hold water, creating breeding grounds for mosquitos.

• Litter encourages further dumping.

EROSION THREATENS INFRASTRUCTURE & PLANT LIFE

• Loosened foundations of stairs, utility poles, and other structures reduces community safety.

• The 30% slope and absence of nutritous topsoil discourages plant growth, limiting the ecosystem’s potential.

• A lack of topas and other building materials is causing amphibious homes to sink, threatening resident health.

RESIDENTS GROW FOOD AND MEDICINE

• Residents are experienced gardeners who harvest nearby plants for personal use and sale.

BUILDING MATERIALS ARE NEEDED FOR REPAIRS

Local Context

ACCESS TO CITY IS IMPORTANT TO RESIDENT LIVELIHOODS

• Residents sell and trade excess goods at a nearby market.

POOR DRAINAGE DAMAGES

PLAZA

• Flood damage to the plaza directly uphill from Claverito increases the risk of a plaza collapse, endangering Claverito and reducing safe access to the city.

EXPOSED SOIL RISKS FURTHER EROSION

• The loss of vegetation and disassembly of community structures for home repair leaves soil unsupported.

Health Implications

INCREASED RISK OF VECTOR OR ANIMAL BORNE DISEASE

Dumping Attracks Insects and Harms Plants & Animals

REDUCED FOOD SECURITY FROM POOR SOIL QUALITY

INCREASED RISK OF INJURY, ANXIETY, & DEPRESSION

Rain Impact and Fast-flowing Stormwater Causes Erosion

Goals & Objectives

CLAVERITO’S HILLSIDE IS STABLE AND PROTECTED FROM EROSION NOW AND IN THE FUTURE 1

• Terraces slow runoff, reducing erosion and encouraging water infiltration

• Ornamental plants discourage littering/dumping

• Intensive plantings protect and stabilize soil

CLAVERITO’S HILLSIDE IS PRODUCTIVE, AND SUPPORTS COMMUNITY HEALTH 2

• Increased gardening space imporoves food security and access to traditional medicines

• Fast growing bamboos and other plant species improve access to building materials for home and infrastructure repair

ExistingSlope(avg.30%)

Increased Soil Protection and Water Infiltration

BLOOMING PLANTS DETER DUMPING/LITTERING

• The installation of ornamental plants on Claverito’s hillside in 2015 led to lower rates of littering in the following months.

TERRACING SLOWS RUNOFF, REDUCING EROSION

• Steep slopes cause runoff to flow quickly, picking up soil and taking it downhill.

• Terracing creates nearly flat sections of earth about 3 meters deep that periodically slow water, allowing it to be absorbed into the ground.

BAMBOO & OTHER TIMBER INCREASE ACCESS TO BUILDING MATERIALS

• Fast-growing, strong, and buoyant materials like bamboo and balsa grown on the hillside make building materials readily available for home and infrastructure repair.

NEWEXISTINGHIGHRIVERLINE

HIGHRIVERLINE

COVERED WORKSPACE ALLOWS FOR MATERIAL PROCESSING & STORAGE

• A covered workspace allows harvested materials to be treated and processed for greater durability.

(Astley) (“Bamboo Treatement”) (“Phyllostachys Edulis”) (Tardio) (Kuikel)DESIGN

FORMAL GARDEN SPACE SUPPORTS HEALTH

• Plants grown on-site creates a reliable source of food and medicine.

STORMDRAINS REDIRECT RUNOFF, REDUCING EROSION

• A stormdrain installed in the flooding portion of the plaza will prevent further erosion beneath the plaza’s foundation.

(“Walkways”)

PLANT ROOTS AND RHIZOMES HOLD SOIL IN PLACE, REDUCING EROSION

(Ramos-Arcos)

• Plants well suited for erosion control like vetiver, bamboo, and paspalum, protect the soil from becoming disturbed and hold it in place.

KEY PLANT SPECIES

Key Plant Species

‘Tropical Lalo’ Paspalum

Paspalum hieronymii

• Low-growing,

• Low-maintenance

• Dense, Resilient Grass

WELLNESS

Parakeet Flower

Heliconia psittacorum

• Vibrant ornamental

• Rhizome spread

• Wind-pollinated

Vetiver

Chrysopogon zizanioides

• Fiberous roots extend up to 4m deep within 1 year.

• Root oil used as natural insect repellent

• Dried leaves and roots used in crafts and construction

Balsa Tree

Ochroma pyramidale

• Among the lightest known timbers

• Traditonally used in raft construction

Giant Bamboo

Dendrocalamus giganteus

• Culms grow up to 30cm in diameter

• New shoots grow up to 30cm/day

Colombian Timber Bamboo

Guadua angustifolia

• Strongest known bamboo species

• Rhizomes spread up to 2.5m and roots extend up to 2.5m deep

Ficus Tree

Ficus guianensis

• Extensive root system

• Latex used to treat abdominal pain

Ají charapita

Capsicum chinense

• #1 most grown plant in Claverito’s floating gardens

• Variety of medicinal uses

• Especially profitable

BUILDINGMATERIAL

Orégano

Origanum vulgare

• #2 most grown plant in Claverito’s floating gardens

• Variety of medicinal uses

Phases 1-6:

ExistingSlope(avg.30%)

Phase 8: Within 2 years of being built, the bamboo crib-walls fully decompose. Plant roots hold soil in place in perpituity.

Terraces can be constructed in sections as materials become available. Bamboo grown on earlier sections can be used to construct later sections.

begin to decompose while plants grow. (Vecteezy.com; iStockphoto.com)

GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ‘ONE HEALTH ISSUES’

2 2

3 3 4

Reduce the cases of mosquito-borne diseases such as dengue, zika virus, and malaria among the residents of Claverito by suppressing local mosquito population.

Support the livelihood, safety, and well-being of the residents of Claverito through relevant and inclusive landscape strategies.

Establish a balanced ecosystem that will support animal lives such as dragonflies, bats, birds, and frogs, and potentially control the population of other vectors of diseases.

Seasonal dragonfly ponds, scattered lily pads, and necessary vegetation that will support the life cycle of dragonflies.

A floating bamboo pier that can be used by outsiders to dock their boats for a fee and enhanced walkways with rope railings for safety and ease of circulation among all types of people.

Scattered camu-camu trees that will utilize fecal matter as fertilizer to grow fruit for the residents and serve as habitats for birds and bats.

Batboxes that will support mosquito-eating bats especially at nighttime.

1 1 DESIGN ACTIVISM STUDIO // IQUITOS, PERU K FAMINIANO 149

FLORA LIST AND THEIR SEASONALITY IN CLAVERITO

Nymphaea ‘Water lily’

Myrciariadubia‘Camu camu’

Typhalatifolia‘Cattail’

Victoriaamazonica‘Amazon water lily’

Irispseudacorus‘Yellow iris’

Pontederiacrassipes‘Water hyacinth’

FAUNA AND THEIR HABITATS IN CLAVERITO

Dragonflies

Bats Birds

Damselflies

Fish

Frogs

LILY PAD CORRIDOR

CAMU CAMU WALK BATBOXES EXISTING CAMU CAMU THICKET

DRAGONFLY POND

HILLSIDE

DRAGONFLY HABITAT REQUIREMENTS IN CLAVERITO AND THE DRAGONFLY LIFE CYCLE

Clean water with substantial amounts of sunlight that will enable female dragonflies to lay their eggs and suppress mosquito larvae.

Plants that filter water contaminants and support the life cycle of dragonflies from mating to the time the emerging dragonflies shed their exoskeleton to fly away.

Lily pads and plants with blooms to attract dragonflies.

Wood and rocks for dragonflies to nest on.

Bamboo edge that will float, shape the water area, and keep the water hyacinths out of the water area during the high flooding season.

Bamboo edge that can be used as a planter edge to grow vegetables or other plants.

DID YOU KNOW?

Mosquitoes are an important component of a dragonfly’s diet. According to a study conducted at a research farm of the University of Ghana, dragonflies can dominate a mosquito-populated site especially if it’s not in a shady area. Sunlight is a crucial part of a dragonfly’s habitat (Acquah-Lamptey and Brandl, 2018).

PROPOSED SPACES

Dragonfly Pond

Edible Garden (Dry Season)

Camu camu walk

Floating bamboo pier

Social Space (Dry Season)

Bamboo walkway (with rails)

Lily pad corridor Batboxes area

ONE HEALTH ISSUES

Mosquito-borne Diseases

Malnutrition

Depression Injuries

Food Insecurity Biodiversity Issues

Camu camu thicket

Hillside Soccer field/play area (in Dry Season)

LANDSCAPE FUNCTION

EXISTING SPACES DESIGN INVENTORY

Habitat Source Barrier Filter Conduit Sink

16 300+ 9

Floating bamboo pier Rope railings

Batboxes

Dragonfly ponds Lily pads

FLOATING BAMBOO PIER

Lily pad corridor connected to the nearby water areas for dragonflies to utilize during the dry river season.

Existing Camu camu thicket to remain and serve as additional habitats for birds.

Floating bamboo pier where non-Claverito residents can dock their boats for a fee.

Rope railings are incorporated on the walkways for safety.

Victoria amazonica

Victoria amazonica

Batboxes for bats that feed on mosquitoes especially at nighttime.

ISOMETRIC VIEW OF THE PROPOSED DESIGN

DRY RIVER SEASON PERSPECTIVES

During the dry river season, the pier can be used as an extra space for events and parties.

BAMBOO PIER IN DRY SEASON

The dragonfly pond area can be used as a space to cultivate vegetables or other plants during the dry river season.

THE PLASTIC PROGRAM

The amphibious community of Claverito has a trash accumulation problem. The current from the river brings plastic waste into the community and this has a toll on the community. This project aims to use this material in new ways to clean the community and provide the residents with a new construction material and revenue streams.

ONE HEALTH

The plastics cycle in Claverito begins when the a bottle is tossed into the river or community.

THESE PLASTICS AFFECT THE PLANTS, ANIMALS, AND HUMANS INVOLVED

The plastic breaks down while in the water and forms microplastics. These are then absorbed or consumed by the wildlife

The cycle is complete when the community members throw plastic back into the water.

The human population then ingests the wildlife and all the toxins within.

INFLAMMATION

HEART DISEASE, BOWEL DISEASE, RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

CELLULAR DAMAGE

DNA MUTATIONS, CANCER, IMPAIRED

METABOLISM

CHRONIC DISEASES

CANCER, DIABETES, CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

SOLID WASTE IN CLAVERITO

PLASTIC BAGS

BURIED PLASTICS

FOAM PLASTICS

25% 18% 10% 5%

OTHERS

42%

PLASTIC BOTTLES

Almost half of the waste in Claverito is clasified as plastic bottles. The second largest category, ‘Others’, contains materials like metals, clothes, and construction materials. Even when cleaned, the community still gathers a large amount of plastics in the water.

RECYCLING PLASTIC

The plan to combat this abundance of plastic in the community is to create a recycling center. This recycling center is a place where the community can gather, sort, crush, and melt the plastic found in their waters. This program uses community labor, partnerships, and innovative recycling practices.

BINS

The collection bins are then moved to the recycling center where the bottles can be sorted, washed and chopped. The plastic is placed in the collection bins located throughout the community. When full, these bins are taken to the recycling center

COLLECTION

The first step is for the community to collect plastic in their communtiy. This is already seen in their occasional Mingas.

SHREDS

Bottles are cleaned and sorted at the recycling center before being shredded. Plastics are sold in shreds, and it conserves more space. Before shredding the bottles need to be separated.

This project proposes a partnership with LOOP, a group out of Lima Peru that is promoting the collection and reuse of plastic waste. They use plastic waste to create products to sell that also promote an awareness of the rising levels of plastics in the oceans. This partnership could include educational sessions, economic connections, and

REPURPOSING

USE

The chopped clear plastic is valued higher than colored plastic so this is packaged to be sold. Sold through a partnership with LOOP. The chopped colored plastics can either be packaged and sold, or placed in the parabolic mirror and melted.

The melted plastic can then be used for injection molding of construction materials for the community or products to sell.

The community can use a parabolic mirror heating system to melt the plastic without releasing toxic chemicals. This process was developed by FLIPFLOPI working in Kenya to create a traditionaly designed boat constructed out of recycled plastics. The mirror uses the power of the sun to heat a metal tube filled with the plastic shards. The melted plastic can then be injected into molds of items to sell at markets or construction materials to use in the community.

COMMUNITY BENEFITS

EDUCATION

Some of the best benefits that this plan brings to the community is the partnerships with thirdparty groups. Both LOOP and FLIPFLOPI are great sources of knowledge on new techniques for recycling plastics in innovative ways. This knowledge is something that the community of Claverito can benefit from greatly.

HEALTH

The removal of plastic from the community will have great impacts on the health of the community. A lot of diseases fester in contaminated and polluted water so it is important to keep the space clean. Removing plastics will decrease the amount of longterm and dangerous illnesses in the community.

ECONOMY

New streams of revenue are created by the sale of chopped clear plastic and reformed colored plastic merchandise. The revenue from these sources will be used to improve infrastructure in the community on a needed basis.

COMMUNITY SPACE

When the recycling center is not actively being used the space can be cleared for community gathering events. This could include community meetings, large construction projects, celebrations, and educational events. This can be a valuable space during the high river season when usable space is limited.

01 Health Context

Animal Bites and Chronic Disease Risk

InterACTION Labs, Research APR 2017, FEB 2018, JUL, 2018 Claverito

Bird Watching HQ. (2022, October 31). 22 COMMON Spiders Found in Peru! (2023). https://birdwatchinghq.com/spiders-of-peru/