10 a.m. to 6 p.m., Monday-Thursday; 10 a.m. to 10 p.m., Friday; and 1-6 p.m., Saturday

Clyde H. Wells Fine Arts Center

Help

Hero, A&M Chancellor

tarleton, A&M Began Accepting African-American

Presidency Marked by Growth,

to

University status Comes in

Heritage

Musical Genesis for

regent Clyde H.

Commemorates History

with

The importance of community support was vital to Tarleton when classes first began in Stephenville, through the drive to become part of The Texas A&M University System a century ago, and persists today as Tarleton continues to expand as the second largest university in the System.

Building

Tarleton’s ever-present connections to the military became even more pronounced when it became part of The Texas A&M University System.

To help entice the Aggies to take Tarleton College under its wings, Tarleton’s supporters purchased 500 acres of nearby land for a school farm.

As World War II was winding down, so was the administration of Dean J. Thomas Davis, who had been charged with guiding John Tarleton Agricultural College through nearly three decades in The Texas A&M University System.

It has been almost 100 years since Tarleton State University joined The Texas A&M University System. The upcoming centennial provides an incredible opportunity to reflect on this great university’s amazing history. Much like my alma mater, Texas A&M University, this school is steeped in tradition and enjoys deep military ties.

Our century-long relationship has proved beneficial for both Tarleton and the A&M System. Joining the System made it possible for Tarleton to establish its agricultural programs, which have gained national prominence and continue to serve the region and the country. By growing and nurturing academic programs in Killeen, Tarleton also played a key role in establishing Texas A&M University-Central Texas, now one of the System’s youngest standalone institutions.

This is also a moment to look forward to the next 100 years. There are many exciting and important things happening on the Tarleton campus. The Stephenville campus is being rejuvenated and made more pedestrian-friendly, the stadium will soon be renovated and expanded, a new 80-acre campus in Fort Worth is underway, and I am particularly glad that the school’s Corps of Cadets has been re-established.

Tarleton has been an integral member of the A&M System for the last century, and I believe this important connection will only become stronger as Tarleton and the A&M System continue to flourish in the future.

This year, we celebrate a significant benchmark in our history: the 100th anniversary of our becoming a foundational and historic member of The Texas A&M University System.

On occasions such as this, we not only look back at our unique heritage, but look forward with momentum and pride.

Our vision is clear: Tarleton will be the premier student-focused university in Texas and beyond.

This vision is born of John Tarleton’s dream of an institution where students have access to an education that improves their lives and communities. It is a vision consistent with the Land Grant charge to Texas A&M University to bring a broad-based and practical education to all.

In 1917, Tarleton’s President James Cox and Texas A&M’s W.B. Bizzell realized the potential of our union. They shared gratitude for John Tarleton and all that this pioneer made possible. The power of one person to impact so many lives is an example for all of us.

We are inspired to ensure the quality and extend the reach of a 21st century university. In 100 years, our tools have changed. The body of knowledge has grown exponentially. Our curriculum and student body have grown as well.

We are committed to the success of each student and to the faculty, staff, programs and infrastructure that will lead them to their academic goals. We are preparing graduates for leadership and service in a global society. And, we are preparing this university for the next 100 years. To adapt. To change. To serve. To lead.

What I believe will not change are our core values. Tradition, integrity, civility, leadership, excellence and service. They remain important guideposts for the Tarleton family, on campus and well beyond.

Here we value history and tradition. The cannon. The gates. The L.V. Risinger Memorial Homecoming bonfire. Silver Taps. The statue of John Tarleton.

These are the foundations on which we can keep the spirit of Tarleton alive for the next century and more.

Many thanks to all of you on whose shoulders we have reached this Texas A&M System Centennial Celebration.

F. Dominic Dottavio President, Tarleton State University

The marriage of a tiny, struggling but well-intentioned private school with one of Texas’ educational behemoths celebrates its 100th anniversary in 2017.

An anniversary whose historical significance is marked by the dedication and commitment of supporters of John Tarleton Agricultural College’s effort to join with Texas A&M.

Among the key players in the century-old drama were a steadfast college administrator in Stephenville, the visionary head of Texas Agricultural and Mechanical College, various local boosters, benefactors and staunch supporters.

The courtship began innocuously enough when Tarleton President James F. Cox, who took the reins of the school in 1913, realized the dire straits facing the school in the early decades of the 20th Century.

According to Dr. Christopher Guthrie’s John Tarleton and His Legacy: The History of Tarleton State University, 1899-1999, Cox knew the job of just keeping Tarleton operational was a massive one.

“The buildings were in bad repair,” Cox reported. “The library was depleted and entirely inadequate, even for a second-rate junior college. Laboratory equipment and furniture and fixtures for the college were very poor.”

The endowment fund, which launched the school 14 years before, had been depleted by a quarter and Tarleton’s academic reputation was sagging.

“No college president ever faced a more discouraging set-up than was mine at Stephenville in 1913,” Cox said.

Through sheer determination and resourcefulness, Cox and a dedicated, underpaid faculty guided the school’s survival.

Cox envisioned success for Stephenville’s private, self-supporting junior college through joining forces with a larger, stronger state-supported school. His plans revolved around improving Tarleton’s educational quality, thereby boosting the school’s reputation and making prospects for a marriage more appealing to suitors.

Three years after implementing this strategy, Cox contacted Texas A&M President Dr. W.B. Bizzell, suggesting a plan for Tarleton to become a branch institution of the College Station school. Bizzell was intrigued at the prospect.

With the University of Texas beginning to expand, why had Cox and the Tarleton board decided to approach the Aggies?

Agriculture. The College Station institution was the only school in Texas that offered an agriculture-based curriculum. The educational opportunities at Texas A&M dovetailed perfectly with Tarleton’s rural environment and the career requirements of a majority of area students.

Cox’s proposal for the two schools’ promising union depended mightily on supporters of the Stephenville college uniting to impress both A&M higher-ups and the Texas Legislature.

A key provision was for area backers to donate funds to buy 500 acres northeast of Stephenville on which to build a college farm. Additionally, money was needed to reinvigorate the shrinking original John Tarleton

It was a match made in academic heaven.

endowment back to $75,000. The money, land and existing buildings and facilities on campus would be donated to the state, which would result in Tarleton becoming part of Texas A&M.

Local organizations tried diligently to raise the funds, but were significantly short as the deadline drew near. Local philanthropist Pearl Cage, a supporter of Tarleton aligning with A&M, convinced friend and Texas Pacific Coal and Mining Company owner Edgar L. Marston to make up the shortfall.

With the financial portion of the plan ensured, the merger was widely supported in the halls of state government. Still, well-connected Aggies opposed the union on the grounds that it might affect academic programs and enrollment at the home campus. Some of the Maroon and White faithful feared that Stephenville might take state funding otherwise targeted for College Station.

According to Guthrie, Bizzell assuaged those fears by promising that “…every effort will be made to so correlate the work of these institutions so as not to result detrimentally to the Agricultural and Mechanical College.”

The critical theme of teamwork to achieve the goal was impressed upon Tarleton students and faculty members, who worked to publicize the hoped-for marriage.

Students in the mechanical arts department created a 3-D model of the proposed college farm, featuring outbuildings, a silo, corrals and a two-story home. The model, presented in Austin by a pair of JTAC students and their teacher, was reportedly favorably received, a sign of snowballing support for the project.

On Feb. 20, 1917, three-and-a-half years after Cox took over at Tarleton, the combined work on the campuses of the two schools, the Legislature and Stephenville as a whole, came to fruition. The bill wedding John Tarleton Agricultural College to Texas Agricultural and Mechanical College was adopted by the Legislature.

During the ceremony announcing the acceptance of the proposal, Cox officially delivered the deed to the farm and the agreed-upon financial package to the A&M board of directors.

Now celebrating the 100th anniversary of this union, Tarleton and Texas A&M continue to live happily ever after.

“

A school will do more for the town than any other enterprise it could get. It will beat two or three Thurber railroads, a cotton oil mill and an ice factory all together.”

Eugene B. Moore, Editor of The Stephenville Empire, in an 1893 editorial promoting the benefits of a college in Stephenville.

“

A building of this character must be built with an eye not only to convenience but also with the view of ministering to the comfort and health of students. The lighting and heating must be perfect that the health of the students not be impaired.”

C.r. Coulter, editor of The Stephenville Tribune, seeking contributions for additional dormitory space on campus in a 1909 editorial headlined “For a Greater Tarleton.”

“ I remind you that John Tarleton still lives through his benefaction. His memory will not vanish from the earth. The students who come here in increasing numbers to profit by the intellectual heritage that this old pioneer has left to them, will not cease to reverence his memory and feel grateful for the educational opportunities that he made possible for them.”

texas A&M President W. B. Bizzell upon Tarleton joining the A&M System.

“

So long as I live I want to see the Purple and White honored and revered…”

Dean J. thomas Davis

“ Our 1934-35 basketball team at Tarleton went undefeated for the second year in-a-row. Two undefeated seasons in-a-row began to get statewide, even national attention.”

Col. Willie l. tate, 1915 and After

“

…the good name of the college depends on proper conduct on the part of individual students. Be a positive factor in the elevation of the moral tone of the student body.” the Purple Book, 1925 edition

Legislative approval and a Herculean fund-raising effort would be necessary to accomplish the joining of Tarleton and Texas A&M a century ago. Stephenville and area citizens were called upon for both, and their tireless efforts proved crucial in making the dream a reality.

They showed up in droves when a committee of five state senators, five legislators and Secretary of State Churchill Bartlett, standing in for Gov. James Ferguson, were greeted in a 1917 inspection tour.

Groups representing communities across the county, from Dublin, Lingleville, Morgan Mill, Thurber, Alexander, Oak Dale and Valley Grove, showed their support, as well, according to Richard King, author of The John Tarleton College Story

“I see you people in Stephenville have been quite busy,” said one lawmaker observing the crowd of an estimated 3,000. “For one thing sure, the proper spirit for building great schools exists in this town to a very marked degree.”

Local women served as hostesses, feeding the visiting dignitaries at the college dining hall, paid for by donations from Stephenville service organizations, including the 20th Century Club and the Knights of Pythias Lodge.

With legislative approval secured, supporters turned to raising an estimated $80,000 in just two weeks to buy the college farm. When A&M President Dr. William Bizzell’s planned visit was postponed, local leaders gained a little extra time to address the $10,000 shortfall.

“This delay will give several of our wealthy citizens who have not been so liberal as they should opportunity to open their purses as well as their hearts,” read a newspaper editorial. “It is too big a prize to lose and it must not be lost.”

It wasn’t.

The funds were gathered in time for Bizzell’s arrival, and Tarleton’s inclusion into the A&M System was assured.

While the mutually beneficial partnership between Tarleton and area residents began 100 years ago, the importance of that alliance remains. Benefactors keep John Tarleton’s vision of educational availability alive.

The Tarleton State University Foundation, incorporated in 1989, has provided more than $9 million in support since then and continues to generously fund scholarships and other university priorities. The Tarleton Alumni Association, founded in 1912, donates all member dues to the university for scholarships, in addition to other continuing support.

Longtime faculty member and local leader Dick Smith left more than a half-million dollars in 1974 for scholarships for students in English, mathematics, science and social science. Thousands of students have reaped the benefits from Smith’s largesse, many finding the Smith scholarship the key to continuing their studies and achieving their degrees.

Similarly, Joe Long, one of Dick Smith’s former students, along with his wife Teresa, provided $3 million for student scholarships and for an endowed chair in social sciences, enhancing both opportunities for students and the university’s academic quality.

Tarleton alumnus and Iredell businessman and rancher Roscoe Maker also endowed scholarships with an estate gift in 2012, exceeding $2 million.

Most recently, long-time faculty member and administrator Dr. Lamar Johanson and his wife, alumna Marilyn Timberlake Johanson, made a life estate gift estimated at more than $5 million, including 1,700 acres of farm and ranch land that the university is using for research and academic programs.

The largest gift in university history, $6 million from Mrs. W.K. Gordon Jr. and the Gordon Foundation, provided $1 million for scholarships and $5 million to continue funding the W.K. Gordon Center for the Industrial History of Texas, a Tarleton historical research facility, museum and special collections library in the ghost town of Thurber. In total, Mrs. Gordon and the Gordon Foundation provided nearly $10 million in support of Tarleton.

Organizations supporting various university functions are also dependent on the support of Stephenville and area residents. The Ultra Club provides scholarships to university fine arts students, as well as travel expenses to conferences and funds for visiting artists.

Similarly, The Texan Club has existed for more than three decades funding athletic scholarships and offering support for Tarleton’s men’s and women’s sports teams.

Additionally, The Friends of the Dick Smith Library, established in 1990, features volunteers and donors in support of library enhancements.

Community support continues to flow to Tarleton to aid its students, improve its programs and advance its contributions to the region, state and nation.

For information about supporting Tarleton, please view www.tarleton.edu/giving

In the heart of the Tarleton campus is the elegant Trogdon House. The home, originally called the Dean’s House, was built in 1923 for the college’s top administrator. Dr. Trogdon, who resided on campus with his family from 1966 to 1982, was the last school president to live there prior to current President F. Dominic Dottavio and his wife, Dr. Lisette Dottavio, who moved into the home in 2010.

Tarleton underwent a multitude of changes during the 16 years Trogdon served as president, including a third name change, the upgrading of the school’s farm facilities, an evolving campus skyline and new four-year study programs.

A swine lab, a meats lab, a pair of poultry buildings, a horticulture building and an agricultural engineering building all became part of Tarleton’s iconic college farm under Trogdon. Additionally, the school added a pavilion, a horse center and updated and improved its dairy facilities during his tenure.

That has been true at Tarleton, which has faced shortages of student housing space since its first day of classes.

When the first 175 students gathered for classes in Stephenville, the college that was John Tarleton’s vision had no dormitory space. That remained the case for 11 years. That first academic year, nearly half the students left school and, while there were several issues involved, some left because there were simply no places to live. Thenpresident Dr. W. H. Bruce resigned after just one year, frustrated over his inability to secure funds to build student housing.

But Trogdon didn’t just work on bettering the ag department. His other innovations included instituting a graduate program in 1968, erecting Wisdom Gym in 1970, including space for the Home Economics Department and ROTC classrooms, as well as a new basketball home for the Texans. The football team’s home field got an upgrade under Trogdon, too. Memorial Stadium was renovated during a four-year stretch of the 1970s.

Other key additions to campus were the construction of Hunewell Hall in 1968 and the purchase of Crockett Hall in 1969. The just-completed three-story humanities building was the showcase of the campus in 1973, when the school officially became Tarleton State University.

One of the most significant campus additions under Trogdon was the Clyde H. Wells Fine Arts Center in 1980. The perfoming arts center was named for the chairman of the A&M Board of Regents and former Tarleton student, whose father had worked at the college farm.

The building consolidated the college’s fine arts programs, which had previously been scattered across the campus.

Tarleton State University; The Traditions Remain reports that the college had no dorm space whatsoever as classes began. Private citizens opened their homes to students, earning around $8 per month for boarders.

The first student housing erected on the Tarleton campus, built in 1910, was a women’s dorm financed by a land donation from an area widow. In an early 1908 editorial, C. R. Coulter, publisher of the Stephenville Tribune, saw several urgent needs on the Tarleton campus—needs that would have to be addressed if the school were to flourish.

“To make John Tarleton College serve the purpose for which the founder gave his fortune many, many changes are necessary,” Coulter penned, pointing out the must-haves as he saw them. At the end of the piece, he called for building a women’s dormitory. In Coulter’s view, the $8,000 edifice could be paid for with a combination of private funds and board appropriations.

Coulter’s request made its way to a recent Erath County widow, Mary Corn Wilkerson, who became the catalyst for construction of the dorm, donating land in Hamilton and Bosque counties valued at $7,500 to be sold to finance the new structure.

Successful businesses recognize that, as their customers increase, they need to add the infrastructure to accommodate their needs.

Wilkerson wrote in the May 7, 1908 deed, that her decision to fund the building came, “…in consideration of the deep interest I possess in the education, the intellectual and moral development of the girls and young women of Erath County and in consideration of and for the purpose of assisting in the erection of a girls dormitory in connection with John Tarleton College and in greater consideration of the abiding faith reposed in the ability and integrity of Prof. J. D. Sandefer, president of John Tarleton College.”

The Mary Corn Wilkerson Dormitory, a two-story, red brick building was almost luxurious for the time, featuring steam heat, electric lights, hot and cold running water and indoor lavatories. Over the next 30 years, additions to the original edifice included Chamberlain Hall in 1925, Lewis Hall 10 years later, Moody Hall in 1936 and finally Gough Hall in 1938.

After World War II, President E. J. Howell, under a state mandate banning new construction, brought in several former barracks buildings from Eagle Mountain Lake Naval Air Base in Fort Worth for student living space.

Campus housing construction has been constant in the century since joining the A&M System. Of the Tarleton residence halls currently occupied, Bender Hall is the oldest, having stood since 1953. Ferguson Hall was added in 1958, followed by Hunewell in 1961 and the Hunewell Annex in ’68.

A half-dozen housing structures have been added since 2000.

In the past three years, the university has opened four new halls and renovated one under a new philosophy of creating Living and Learning Communities designed to aid in retaining students—just as the first dormitory served that purpose. In 2014, Tarleton opened Heritage Hall, in 2015 Integrity Hall, in 2016 Traditions North and South and an expanded and renovated Honors Hall.

The additions create sufficient housing for all freshmen and sophomores –another factor that contributes to keeping students and helping them graduate.

With nearly 4,000 students now living on campus, it’s a far cry from the dearth of housing experiences by Tarleton’s first students.

The 1917 changing of the Stephenville college’s name to John Tarleton Agricultural College marked a pivotal emphasis on an updated curriculum.

Prior to joining The Texas A&M System, Tarleton had no degree program in agriculture, despite the fact that a majority of students came from farming backgrounds. As A&M’s resources began filtering to Stephenville, programs, personnel, courses of instruction and facilities all merged to form the early backbone of the reinvigorated school.

To help entice the Aggies to take JTAC under their wings, Tarleton’s supporters purchased 500 acres of nearby land for transition to a school farm. The farm, located northeast of Stephenville, grew quickly from a sparse acreage to a facility featuring separate barns for horses and dairy cows, sheds for sheep and pigs. Ultimately the farm was divided into different sections for each of the agriculture departments – agronomy, agricultural engineering, animal industry, veterinary medicine and horticulture.

Oddly enough, the school’s poultry activities, a key portion of Tarleton’s agricultural legacy, were housed on campus, rather than on the college farm.

Students and agriculture department faculty took care of the Tarleton flock, which was located in a series of coops on what was then the southwestern border of campus. Tarleton gained national notoriety as generations of hens here participated in egg-laying contests spanning three decades.

C. Richard King reported in his book, Golden Years of the Purple and White: The John Tarleton College Story, that as of 1927, there were 16 official egg-laying contests in the nation. Tarleton’s was ranked first. The school claimed an international title, as well in later competitions, with several local hens earning accolades for their production.

One, a single comb white leghorn, was tops in a 1936 matchup, meeting an untimely end 13 days before the end of the contest

when she choked on a grain of feed corn. She laid the last of 312 eggs five minutes before her death.

The current College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences consists of three departments—wildlife, sustainability and ecosystem sciences; agricultural and consumer sciences; and animal science and veterinary technology.

Today’s program is nationally known for its FFA involvement, providing leadership training for FFA officers and attracting thousands of high school FFA participants for judging events annually. The Career Development Events (CDE) feature more than 20,000 high school agriculture and science students and have been hosted by Tarleton for more than three decades. Tarleton played a part in initiating at least two of the events prior to their adoption into the annual contest.

To keep up with the expanding agriculture curriculum, learning venues have also improved vastly. The original wooden edifice was

replaced in 1951 with the current Joe W. Autry Building in the heart of the Tarleton campus.

Additionally, ag-minded students and faculty are drawn to Tarleton’s Southwest Regional Dairy Center, which opened in 2011 to help develop solutions for sustainability and productivity in the dairy industry.

The cutting-edge Tarleton Agricultural Center is the modern iteration of the college farm that started it all.

That streak came through the instruction of an accidental football coach, aided by a well-known shoe salesman.

Coach W.J. Wisdom, a football coach for the then-Plowboys, had never played basketball. He actually was hired by the school in 1920 as business manager and head cashier at the College Store.

He became head football coach when A.B. Hayes abdicated the position, and proceeded to guide Tarleton to a 71-35-15 career mark, including an undefeated season in 1925. His gridiron success made him the popular choice to take over the basketball team in 1930 as the Great Depression and hard financial times locally forced the fortuitous combination of duties.

Boasting a 111-2 record between 1930 and 1940, Wisdom and the Plowboys were aided in their record quest by Charles Taylor, a shoe company representative from Columbus, Indiana, better known as Chuck, the inspiration and designer of the iconic canvas and rubber high top basketball shoes that still bear his name.

Besides selling footwear, Taylor, a well-traveled semi-pro basketball player, freely shared his knowledge of the game, including innovations in strategy and execution.

Most basketball players of the time had been taught to shoot using both hands—a two-hand set shot that required the shooter to stop and face the goal, allowing defenders to more easily block shots.

During a team clinic, Taylor showed Wisdom a new scoring weapon, the one-handed shot. Using the new shot allowed players to shoot from virtually any spot on the floor, even while moving.

The change in technique, which became a major Tarleton offensive weapon, helped account for an almost 3:1 scoring advantage for the Plowboys during the latter stages of the streak.

Biographer Abraham Aamidor noted that Taylor began his professional career as a 17-year-old high school student, and during World War II became a physical fitness instructor for the Army and Navy pre-flight program at Marquette University.

Besides his contribution of footwear for the game, Taylor also is credited with developing the laceless basketball.

And he had a hand in a record-setting 86-game college basketball winning streak.

The cornerstone of Tarleton’s athletics complex is Wisdom Gym, built in 1970 and renovated in 1977.

Constructed under the direction of President Dr. William O. Trogdon, it is named for highly successful coach and Athletic Director W.J. Wisdom, who was an unqualified success as a coach in two sports.

He became Tarleton’s football coach in 1920 and guided the Plowboys to a 71-35-15 career record, including an unblemished mark in 1925. Financial woes led Tarleton to add to Wisdom’s workload as he took over the school’s basketball fortunes in 1930, despite having little background in the sport.

Though he had attempted coaching basketball prior to coming to Stephenville, he had been knocked down three times during practice by a player and resigned. That player was the center of the girls’ team at Paducah High School.

The lack of experience didn’t hinder the novice coach at the collegiate level as he guided the Tarleton team he nicknamed the Plowboys to a then national record of 86 consecutive wins over a four-season span. Wisdom’s mark was broken in 1970 by UCLA under legendary coach John Wooden.

According to Tarleton State University—The Traditions Remain, Wisdom’s lack of knowledge of basketball made him a detail-oriented student of the game. He was one of the first coaches in the nation to teach the one-hand shot, creating about 80 percent of the Plowboys’ offense during the latter stages of the streak.

An all-around athlete, the future coach also played semiprofessionally in the Colorado State League. Wisdom, born in Pottsville, went to high school in Hamilton and received his teaching certificate from North Texas Normal College before taking classes at the National School of Recreation in Chicago. Outside of sports, he was a talented singer and violinist. No longer the Plowboys, Coach Lonn Reisman’s Texans continue to add to the legacy of excellence begun by Wisdom.

Reisman, coach of the Texans since 1988, coached his milestone 600th win during the 2015-16 campaign. Overall, Reisman, has claimed 13 various Coach of the Year honors, while compiling a stellar 397-64 record as of the start of the 2016-17 season.

What is common knowledge and a point of particular pride for Tarleton sports fans is the 86-game basketball winning streak, covering five seasons in the middle to late 1930s.

It may be right or it may be wrong; it may be good or it may be bad; but right or wrong, good or bad, it has always been done this way. We like it done this way and we plan to continue to do it this way

– L. V. Risinger

– L. V. Risinger

Through the roaring ‘20s, the Great Depression and beyond, Tarleton was establishing its identity among Texas schools.

Dean J. Thomas Davis, who served the longest term for any Tarleton chief executive, took over the school in 1919 and became the catalyst for many of the changes that helped create its character.

He was first to live in what has been named the Trogdon House, part of an extensive building boom on campus. Davis also oversaw the construction of a new conservatory, a science building, additions to the women’s dormitory, a central heating plant and the installation of the famous stone gates at the college’s entrance.

The improved facilities brought with them a corresponding jump in enrollment. Student numbers were boosted three-fold to more than 1,800 in the decade of the 1920s, prior to a downturn as a result of the Great Depression.

One tradition, not invented by Davis but enforced by his administration, was the annual publication of “The Purple Book,” which served as a student conduct guide.

Members of the 1945 Ten Tarleton Sisters (TTS), now known as the Purple Poo, promote school spirit amongst students.

The book, among a myriad other regulations, dictated that female students were to be in their rooms by 7 p.m. on weeknights. Men, many of whom were residents of boarding houses off campus, got an extra 30 minutes. Additionally, the book stated students were not allowed to ride in cars, had to take the most direct route possible when going to town, and not partake of alcohol, tobacco or dancing. Plus, girls had to have a chaperone to talk on the phone.

While the restrictive tone set a formidable list of “don’ts,” students of the Stephenville campus nonetheless set about formulating some of the university’s most beloved traditions. As with other colleges across the nation, a big part of Tarleton’s identity came with the advent of these student-led traditions, many of which revolved around athletics, especially the annual homecoming football game.

For example, the beating of the drum, one of the best-known rituals, starts on an autumn Tuesday with students pounding a 55-gallon barrel for 24 hours a day until Saturday’s yearly homecoming football game.

The tradition initially began in the ‘20s as a way to defend the bonfire from rival North Texas Agricultural College. Now, threats to the bonfire site appear to have diminished, but the symbolic drum beating and the connected bonfire have become integral parts of homecoming festivities.

While working hard to establish its own traditions, Tarleton still shares some of its long-held customs with Texas A&M, including not walking on campus grass, the annual Silver Taps and the yearly lighting of the bonfire.

Student organizations, Ten Tarleton Peppers (TTP) and Ten Tarleton Sisters (TTS) began in 1921 and 1923, respectively, to anonymously boost the Plowboys, who before 1924 were called the Junior Aggies. The groups met nocturnally and painted signs, initially on canvas, for upcoming games. Senior students’ identities were revealed annually upon publication of the yearbook.

The Purple Poo, originally TTP and TTS, is a secret organization still with a sign-creating presence on campus. Members dress in costume for public appearances to conceal their identities, unmasking at the annual Leadership and Service Awards Ceremony each April.

Students had been working for months collecting fuel for the annual homecoming bonfire.

Scrap wood had been donated, some perhaps unknowingly, to the mass of lumber that would light up the sky prior to the Plowboys’ annual battle against the archrival Grubbs of North Texas Agricultural College (NTAC).

Another tradition, one less official, had emerged as the two schools battled each season. Each student body sought to light the other’s bonfire prematurely, to have the flames burn and go down before scheduled celebrations.

Tarleton’s annual beating of the drum tradition began as a deterrent to rivals seeking to slip in and torch the heap early. In fact, a horde of Tarleton students had, in 1939, driven to Arlington and done just that.

In response, an army of Grubbs supporters planned a unique air attack on the Plowboys’ 30-foot-high structure awaiting Friday night’s lighting.

Shortly before 5 p.m. on the Tuesday before homecoming, the sound of a propeller buzzed overhead, noticed by Tarleton football player L. V. Risinger. A plane, flown by two NTAC fans, swooped directly toward the bonfire site with a payload of phosphorous bombs intended to ignite the scrap lumber.

The plane was supported on the ground by truckloads of Grubbs, who were intended to distract Tarleton students and allow the plane to glide in and destroy the woodpile. One bomb dropped, was recovered before burning and buried by local students.

Mickey Maguire, an eye-witness to the event, stood atop the wood stack with a garden hose in hand to battle any flames that might erupt. He recalls how low the plane was flying.

“There were two men in the airplane,” he said, “They were so low I was eye-balin’ the men in the cockpit.”

As the plane circled for another try, Risinger hurled a two-by-four from the lumber heap into the air. The board hit its low-flying target, forcing the damaged plane to make an emergency landing on campus, barely missing the home of Dean J. Thomas Davis, and landing in his garden.

Thomas came to the rescue of the pilots, taking them from the clutches of angry Plowboys supporters and escorting them to the dining hall to await pick-up by NTAC administrators.

Risinger’s heroics resulted in having the yearly bonfire named after him. For a first-hand account from a participant in the 1939 bonfire defense, watch the video and hear the story from Maguire, ’40: www.tarleton.edu/maguire

About the end of World War II, leaders from both schools decided enough was enough and temporarily halted the annual bonfires, choosing instead to award the season’s football game winner a trophy Silver Bugle, the subject of another lasting Tarleton tradition.

Football player L.V. Risinger holds his brother aloft. Risinger famously threw a 2x4 piece of wood at a rival plane, which hit the propeller and took the plane down.

As political conditions eroded in Europe and America’s entry into war seemed inevitable, Tarleton’s administration prepared the school to do its part.

Dean J. Thomas Davis had joined forces with municipal leaders in 1939 to petition the Civil Aviation Authority to offer pilot training at Tarleton in anticipation of the United States’ entry into World War II. Additionally, the school offered ancillary courses in airplane engine mechanics and a preparatory class for air corps hopefuls.

In 1942, Davis even rearranged the school’s class schedule in the summer, making it a regular semester so students anxious to enlist in the military could graduate quicker.

Dean. J. Thomas DavisWomen who wished to join the effort were included in a course instructing them to perform traditionally male duties at defense plants, now scattered across the country.

Tarleton also became a selected campus for the Army Specialized Training Program, as college professors instructed soldiers in specific high-need areas, including engineering, medicine, science, mathematics and languages.

Among the college’s graduates who served with distinction in World War II were pilots Lt. Col. William Dyess and Bob “Bullet” Gray.

Dyess, who was forced into the infamous Bataan Death March after being captured by Japanese soldiers, is credited with shooting down five enemy planes and destroying a 12,000-ton ship in the Pacific theater.

Gray, one of 80 pilots selected by well-known fighter pilot Lt. Col. James Doolittle to participate in the Raid over Tokyo, targeted a Japanese munitions factory before being hit and forced to bail out over China.

But the school was not just educating soldiers. It was supplying them.

Obviously, students were flocking to recruitment offices, but Tarleton’s faculty also answered the call sent out for men to defend the nation. Among them were professor of auto mechanics E.A. “Doc” Blanchard, who became a quartermaster; O.H. Frazier, who went from teaching animal husbandry to serving in a tank destroyer unit; and Plowboy football coach James Earl Rudder, who became an Army Ranger.

Rudder was in the first wave of U.S. soldiers to storm Normandy Beach on D-Day. He is credited with leading a cliff-side raid that disabled German artillery. By the time the war had ended, Maj. Gen. Rudder had become one of the nation’s most decorated soldiers. He was later installed as President of Texas A&M University and Chancellor of The Texas A&M University System.

Tarleton’s ever-present connections to the military became even more pronounced when it became part of The Texas A&M University System. The Aggies shared their servicebased traditions of drill and military tactics that were part of the curriculum for male students in the fall of 1917.

Preparing for the eventuality of joining World War I, local students marched in their street clothes with wooden rifles to perfect their close quarter skills.

By Thanksgiving, each cadet was swathed in an official uniform and training evolved into a national duty. Doing its part in the war effort, Tarleton formed a branch of the Students’ Army Training Corps so men in classes in Stephenville could continue studying while training for deployment overseas.

Administrators were initially leery of the plan, arguing that students shouldn’t be expected to carry a full academic load and train for combat. However, the $30 stipend offered for trainees proved to be more of an enticement than that argument could subvert.

Many of Tarleton’s young men were called upon in WWI, including Ammon Turnbow, the first in Erath County to sacrifice his life in the conflict.

In a letter from Turnbow to then college President James Cox, the soldier described his connection to the school, as well as some of the difficulties he and his fellow doughboys faced.

“No doubt you will be surprised to hear from an old student like me,” Turnbow wrote in September of 1918, “but when one has gone to the old college as long as I have, I think about how things are going about now.”

His reminiscences were short as his situation took over the letter’s tone.

“I have been having some real times over here,” Turnbow penned. “Have been in the front line once and stayed there three days and nights. No sleep nor rest while you are there. You don’t want to sleep very much.”

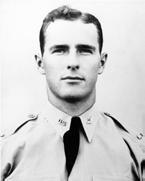

Ammon Turnbow, who attended Tarleton, was the first in Erath County to sacrifice his life during World War I.

Chancellor John Sharp (right) talks with members of the Corps of Cadets, including the first female corps commander, Kelley Rumsey, following an exhibition of military drill on campus.

The end of World War I did not end Tarleton’s military contributions.

In the middle of World War II (1943), 2,500 would-be soldiers were based in Tarleton’s Army Specialized Training Program. Among those training in the program were war hero Lt. Col. William Dyess, academy award-winning actor George Kennedy, and Gen. James Earl Rudder.

The ASTP program originally was intended for four-year colleges only, however Tarleton administrator E.A. “Doc” Blanchard, convinced the army brass that the school and the training program were a good fit. It was fortuitous for the Stephenville school as the war had resulted in drastically declining enrollment numbers.

Blanchard himself joined the Army Intelligence Corps, making him one of very few with Tarleton ties to serve in both World Wars.

World War II Gen. Mayhew Wainright was honored at Tarleton with the 1949 formation of the Wainright Rifles drill team. Entry into the group required an audition and a vote by existing members.

The team made appearances at various drill competitions, at every home football game with its finest hour coming in a performance at the presidential inauguration of John F. Kennedy in 1961.

The group reformed in 2013 after two decades of inactivity.

The Texan Corps of Cadet program was revived in the fall 2016 with the goal to develop leaders of character, instilled with the values essential for service to the nation and exceptionally qualified to succeed in business, government and the military.

As World War II was winding down, so was the administration of Dean J. Thomas Davis, who had guided John Tarleton

Agricultural College through nearly three decades in The Texas A&M University System.

In 1945, Davis handed the reins to President E.J. Howell, who would oversee the school through a period of unprecedented campus growth and change.

Realizing he was building upon the foundation supplied by Davis, Howell was quick to offer his appreciation.

“This fine physical plant, the strong faculty, the high academic standards and the thousands of men and women who are former students of the college stand as a monument to his wise leadership and administration,” Howell said.

Challenges confronted him. Overcoming space shortages in housing and classrooms with resourceful additions of student living space and new agriculture and science buildings, a women’s gym and a student center, Tarleton took on the aspect of a major educational center.

To draw more female students, Tarleton added an education program. Howell felt, however, that the John Tarleton Agricultural College moniker limited the scope of perceived educational opportunities on campus. He proposed a name change to Tarleton State College, which won the approval in 1949.

The most enduring change—offering bachelor’s degrees—required the heavy lifting of public support. Howell turned to Stephenville community stalwarts in 1952 for help, and they responded by creating the Tarleton State College Booster Committee, chaired by Dr. Vance Terrell, and including Hugh Wolfe, Brad Thompson, Bill Oxford, Lucy King and a virtual Who’s Who of local leadership.

The committee’s credo, “If Tarleton College Grows, Our Town Grows,” produced a three-year strategy to attract more students. Included in the plan were an additional 100 scholarships and a far-

reaching publicity campaign. Enrollment rose in 1953, topping the 1,100 mark by decade’s end.

Terrell, Joseph Chandler and other Booster leaders were convinced that regional educational needs could only be met by a four-year school. Easier said than done.

After a failed attempt in 1955, a second effort in 1957, highlighted by a presentation to lawmakers by Terrell and Jack Arthur, gained legislative sanction. Although lack of support by the Commission on Higher Education held up final approval until 1959, Gov. Price Daniel signed the bill into law in a ceremony attended by Howell and Booster members, including Arthur and Rufus Higgs.

The Class of ’63, 29 strong, was the first to graduate under the fouryear curriculum.

As the ‘60s opened, the growth in programs and the changing times prompted Tarleton students to replace the Plowboy mascot, electing instead to be called Texans for the men’s sports teams, and TexAnns for the women’s squads.

The symbol of the “Texan Rider,” a cowboy on the back of a rearing horse, was adopted. The Class of ’67 gifted the iconic mosaic in front of the Tarleton Center, modeled on the first Texan Rider, Mike Moncrief, who later became a state legislator and Mayor of Fort Worth.

The commander was among the first to take the beach at Normandy on D-Day.

Bullets flew, artillery raged and about half the Allied soldiers deployed in the historic offensive were casualties. Still, his Rangers hit the sand at Pointe du Hoc under withering German fire and disabled enemy gun batteries perched atop 100-foot cliffs.

He was injured twice in the fighting, but still achieved his mission – to establish a beachhead for Allied forces.

He was also part of the action in the Battle of the Bulge and received numerous commendations, including the Distinguished Service Cross, Legion of Merit, Silver Star and the French Legion of Honor with croix de guerre avec palme.

For his outstanding service and dedication, he wound up a general.

Tarleton football coach James Earl Rudder, like thousands of other Americans in the early 1940s, was called upon to take up arms and put off his daily life for the good of the country. He responded by becoming one of the United States’ most decorated war heroes.

His connection to John Tarleton Agricultural College began as a student from 1927 to 1930. He earned a spot on Coach W.J. Wisdom’s state junior college champion Plowboy football team as center and displayed leadership traits even then, becoming team captain in his second season.

Rudder’s first taste of military training came in ROTC classes while at Tarleton and continued at Texas A&M, from which he graduated in 1932.

After building a budding high school football powerhouse in Brady, Rudder was tabbed to take over for Wisdom in 1938, and guided the football Plowboys until his war-related resignation in ’41.

Rudder’s public service continued after his Army career ended. The former Plowboys coach was elected mayor of Brady and Texas Land Commissioner before becoming vice-president, then president of Texas A&M University and ultimately Chancellor of The Texas A&M University System.

In commemoration of Rudder’s heroism and his leadership of The Texas A&M University System, Tarleton has named a pedestrian walk Rudder Way and plans to install a statue of him in November.

Racial integration on American college campuses was a divisive, hotbutton issue during the 1960s. African-American students, long restricted to colleges in certain areas of the nation or to historically black institutions, attempted to broaden their reach throughout the South. Including Texas.

While Texas A&M admitted its first African-American students in 1963, Tarleton quietly, and through a small act of subterfuge by several faculty members, admitted its first in 1965.

Shirley Ann Durham of Stephenville wanted to attend college, possibly as a result of an interaction with Lewis Woodward, a voice teacher at Tarleton, according to historian Christopher E. Guthrie in John Tarleton and His Legacy: The History of Tarleton State University, 1899-1999.

The two apparently met in a Stephenville drug store, where Durham and a friend were staging a sit-in. Woodward, in support of their cause, sat in their booth. They discussed the civil rights movement and later he invited them to bring their families to Tarleton’s musical productions.

“We really needed to see Negroes in the audience,” Woodward said, “so that people would see that it was OK and they were part of the community.”

Several high-profile faculty members, notably Dick Smith, O.A. Grant, Hilmar Wagner and John Pratt learned of Durham’s goal to attend college and reportedly broached the subject to President E.J. Howell, who rejected the idea.

Nonetheless, the professors pooled money to pay Durham’s tuition and fees, then helped her register for spring semester. By the time Howell found out, she was enrolled, leading to a terse “Tarleton is integrated this semester,” statement from Howell accompanying enrollment reports.

Integration in the A&M System actually occurred almost two years earlier when three African-American men enrolled in summer classes at College Station.

Already facing public scrutiny for new policies admitting women, A&M President Earl Rudder’s administration carefully planned its integration in 1963 to avoid the media exposure affecting many southern state universities fighting integration.

George D. Sutton and Vernell Jackson, high school science teachers, were signed up to attend an institute at A&M funded by the National Science Foundation. Leroy Sterling, a junior at Texas Southern University, a predominantly black college in Houston, wanted to enroll in summer classes closer to home so he could finish his degree the next academic year.

He had been denied admittance to A&M in the spring with the written response: “We are not admitting Negroes at this time.” Returning home for the summer, Sterling was surprised to receive a telegram reversing the initial decision.

Sterling reported to the registrar’s office where he met Jackson, his high school science teacher, and Sutton, according to Thomas M. Hatfield’s book, Rudder: From Leader to Legend The three were enrolled and, by the time their presence on campus was noted, the story barely made the newspapers.

In 1999, Shirley Ann (Durham) Thompson received the Trailblazer Award from Tarleton’s Office of Multicultural Services for breaking the university’s color barrier.

Sterling became an educator, eventually an Assistant Professor, Director of Honors and director of a national writing project at Alabama A&M University.

Today, minority students make up more than 27 percent of Tarleton’s student body. That number has been growing each semester. This past fall, the number of minority students, including African-American and Hispanic, totaled more than 3,500.

System-wide, minorities in 2016 make up more than one-third of total student enrollment.

A campus-wide building boom and transformation into a four-year school were the hallmarks of the administration of Tarleton President E.J. Howell.

Howell, a Texas A&M graduate, former registrar and Commandant, served in World War II, commanding officer training schools.

His military expertise translated into a highly successful run in charge of a booming John Tarleton Agricultural College.

Under Howell’s guidance, Bender, Ferguson and Hunewell halls were erected to handle an unprecedented influx of students. Prior to the flurry of additions to student housing, Howell had to prove his resourcefulness to give his students campus living space.

A shortage of materials had resulted in a post-World War II building ban but that did not keep Howell from finding space for students. While prevented from building new dorms, funds were available for repairs to existing buildings. The Tarleton president used renovation and repair dollars to transform several campus buildings into temporary dormitories.

Additionally, he contacted a naval air station in Fort Worth and arranged for the college to accept donation of two wooden barracks. The Federal Housing Authority also lent a hand by giving the school 52 trailer houses.

Student housing was not the only construction going on as the moratorium was lifted. Tarleton’s face was ever changing as Howell’s projects were completed—a science building, an agriculture building, a women’s gymnasium, a library, a student center and Memorial Stadium.

Besides adding tremendously to campus resources, Howell returned the school’s curriculum to pre-war standards, adding education and psychology departments and was instrumental in changing the name to Tarleton State College, converting the two-year institution to a four-year school.

In honor of Howell’s success during his 21-year presidency, the education building, built in 1919 was named in his honor in 1997. The building, which has undergone four renovations, originally housed the college administrative offices, then the agriculture department and the department of fine arts.

Texas Gov. Dolph Briscoe had few ties to Stephenville or to Tarleton, but he is forever bound to both as the signatory of the 1973 proclamation granting university status to the school.

Earlier as a state legislator, Briscoe gained fame for a bill to build farm-to-market roads in rural Texas. Those same roads brought students to John Tarleton Agricultural College, then Tarleton State College, and finally, to Tarleton State University.

Probably the most influential issue leading up to the school’s advancement to a university was the offering of master’s degrees beginning in 1971, according to Dr. Christopher Guthrie, author of John Tarleton and His Legacy: The History of Tarleton State University, 1899-1999. Graduate degrees were offered in agriculture and education, initially, but within a decade grew to include health, physical education and business administration.

The Student Senate was the first group to officially seek university status, passing a 1972 resolution asking for Tarleton State College to be renamed. The request was unanimously approved by the Academic Council.

Those actions gave President W.O. Trogdon the necessary examples of broad campus support for the change, which led to approval by the Texas A&M System Board of Directors.

As was the case 14 years prior when Tarleton had sought to become a four-year college, the change also needed approval from Austin.

State Rep. C.C. “Kit” Cooke and Sen. Tom Creighton each presented identical bills to the Texas Legislature to change Tarleton’s status, and Briscoe added his signature on June 13.

Among those attending the bill-signing were Trogdon, Cecil Ballow, J. Louis Evans, Clyde Wells, and Dean of Men Mike Leese of Tarleton, along with Stephenville Mayor Don Jones and other local leaders.

Tarleton State University’s initial graduating class in August 1973 included 179 students -- 128 receiving bachelor’s degrees and 51 master’s degrees.

The commencement address was delivered by Rep. Cooke at Wisdom Gym, but to those graduating then and at each graduation ceremony since, Gov. Briscoe’s signature enabled the name, Tarleton State University, to reflect not only the students’ expanded educational opportunities but also university status on their diplomas.

Governor Dolph Briscoe signing the bill on June 3, 1973, which made Tarleton State College a university. Looking on are (from left to right) Dr. W.O. Trogdon, Tarleton President; Dr. J.W. Autry, Tarleton VicePresident; Representative C.C. Cooke; and Clyde Wells, Texas A&M University System Board of Directors President.

“You get what you pay for” may be a widely accepted aphorism but a wistful look back at the cost of a college education reveals that those expenses actually yield higher than expected dividends, especially at Tarleton.

Tuition for students of Stephenville College in 1894, Tarleton’s precursor, ran $4 per month, and students and their families could barter the charges with livestock or produce. By 1896 the fees had jumped to $16 per semester. When the school began operating under John Tarleton’s name, tuition dropped to $3 per month with students furnishing their own books.

According to research noted in John Tarleton and His Legacy; The History of Tarleton State University, 1899-1999 by Dr. Christopher E. Guthrie, the cost of a semester of full-time learning as the 1970s

were dawning was $113.50, plus any lab fees, a one-time $10 breakage fee and $2.50 for parking. Over the course of a four-year program, basic tuition costs would have amounted to less than $1,000.

That compared to the national average of $358 per semester for public, four-year institutions at the time. When comparing then-and-now costs, however, it is important to note that in 1970 the average annual income was less than $8,000.

According to information from American Public Radio, only 26 percent of middleclass workers had any post-high school education in 1970. Today, almost 60 percent of all jobs in the U.S. economy require higher education.

Still, the cost of a college degree was an investment that paid off like never

before in the history of the country as incomes soared in the 1980s and 1990s for graduates of the 1970s.

Today, Texas residents pay around $4,000 per semester for tuition, according to collegecalc.com, making Tarleton one of the lowest priced four-year schools in the state.

The value continues, as Tarleton graduates enter their professional careers. A recent economic impact study noted that Tarleton students will earn $3.40 for every dollar spent on their university education, an average annual return of 14.2 percent on their investment. That means that a typical Tarleton graduate can expect at mid-career to make almost $32,000 more a year—or $1.2 million more during a career—than a high school graduate working in North Texas.

It was the very definition of an uphill battle.

Upon taking charge of the struggling John Tarleton Agricultural College in 1913, President James Franklin Cox noted that weeds were taking over the grounds, the few buildings were quickly becoming dilapidated, money was in extremely short supply, and his faculty consisted of just two instructors.

Not science or math professors. Not vocational teachers for home economics or agriculture.

Two music teachers who began Tarleton’s educational legacy in the fine arts.

Charles and Edna McKenzie Froh, husband and wife, took on the daunting task of initiating a music program at the cashstrapped institution, often working for IOUs in lieu of paychecks prior to Tarleton joining the Texas A&M System.

In the genesis of the music program, the Frohs taught beginning piano lessons sporadically to very few serious music students. Their unswerving dedication gave way to an eventuallyexpanded curriculum including courses in percussion, brass, woodwinds and strings, as well as vocal and choral performance.

Charles Froh, who taught at Tarleton from 1909 to 1947, was an Indiana-born music teacher educated at the Bush Conservatory of Music in Chicago. He left the Midwest to take a part-time job with Charles Landon of the Landon Conservatory in Dallas. Though the position, unbeknownst to Froh, turned out to be that of a janitor, he so impressed Landon that he eventually became an instructor.

While in Dallas, Froh met harmony student Edna McKenzie and the pair fell in love. They married prior to graduation. They moved to California to teach, then to Tarleton, where, according to Golden Days of Purple and White; The John Tarleton College Story by C. Richard King, hard fiscal times meant the duo sometimes were not paid.

“Many times the faculty would be compelled to do without their salary checks for three or four months,” wrote Cox during the 1913 school year. “The board would borrow the money in order to pay the teachers. This money borrowed was guaranteed by the board and meant a great responsibility for them.”

Froh’s job included developing a faculty that, early on, featured his wife, who, based on a listing in the college catalog, had “at her command a highly imaginative, poetical and musical temperament and sound, well-developed technic (sic) to sustain it. She possesses a large and varied repertoire and is constantly adding to it.”

With the infusion of resources that followed as Tarleton became part of the Texas A&M System, Froh and Tarleton were able to construct a top-notch music program, featuring faculty members who carved out their own places in Tarleton history. Instructors like legendary band director D. G. Hunewell, and Eastman School of Music graduate Donald Morton, who would become the department head.

The program has gone on to gain national distinction, with recent appearances at Carnegie Hall by two groups, the Chamber Choir and the Wind Ensemble, appearances in Chicago’s Thanksgiving Day parade by The Sound and the Fury marching band and performances in Japan and Italy by the Chamber Choir and Jazz Ensemble, respectively.

Froh birthed those programs. During his more than three–decade tenure, Froh is credited with spearheading the creation of the marching band, an all-girl band, the Little Symphony Orchestra and choral groups including a glee club and later, the Tarleton Singers.

Upon his retirement, Tarleton boasted a six-person music faculty and several hundred majors.

Today, Tarleton’s music programs continue to evolve and improve. One example is the All-Steinway initiative, a $1.5 million fundraising effort to upgrade the university’s piano inventory, much of which is nearing a half-century in use.

“The Clyde H. Wells Fine Arts Center is one of the most important cultural arts centers in this area of Texas,” said Music Department Head Dr. Teresa Davidian. “We want the best for our community and for our students.”

A total of 41 pianos are slated for eventual replacement and donations of more than $100,000 have been made to purchase the first three.

From struggling genesis to stalwart successes, Froh guided Tarleton music toward its current status.

Named for a distinguished Tarleton alumnus and chairman of The Texas A&M Board of Regents, the Clyde H. Wells Fine Arts Center was the most expensive building on the Stephenville campus when it opened to students in June 1980 at a cost of $7.5 million.

The building, which took almost three years to build, consolidated all of Tarleton’s Fine Arts classes in one facility, an 85,000 square foot structure featuring a theater, an auditorium, two workshop theaters, band and choir rehearsal halls, a half dozen music labs, three art design labs and an art gallery. Upon its completion the Center was immediately recognized as the largest, most modern theatrical complex within a 150-mile radius.

The facility’s namesake had supported the project from its inception.

“I am always amazed at the difference that some new facilities make in the quality of life for those who use them,” Wells said in a 1977 J-TAC story. “It’s not possible to measure the major impact of common-use facilities such as auditoriums, theaters, exhibit halls…The Texas A&M System has long been dedicated to providing a well-rounded education―for the ‘whole man.’ This project is consistent with that philosophy.”

Wells, a Stephenville native, was a Tarleton student in 1935-36, graduated from Texas A&M in 1938 and returned home to teach in 1942-43. He served as president of the Tarleton Ex-Students Association from 1952 to 1954.

His appointment to the Texas A&M Board initially came from Gov. Price Daniels in 1961. His tenure was extended in 1967 by Gov. John Connally, during which time he became board president, then again in 1973 by Gov. Preston Smith.

Under his watch in College Station, Tarleton also received substantial System aid to upgrade its college farm and added a horse program to the agriculture curriculum.

The campus library, resting in the same spot for nearly 60 years, is named for a colorful history instructor and one of Tarleton’s most celebrated long-time academicians.

Dr. Dick Smith was characterized by Tarleton historian Chris Guthrie as being imbued with a “devotion to excellence and impatience with mediocrity, sterile pedantry and bureaucratic nitpicking” in John Tarleton and His Legacy; The History of Tarleton State University, 1899-1999.

Smith brought his Breckenridge High School diploma to Tarleton in 1926, finished his undergraduate studies in Austin at the University of Texas, where he also studied for his master’s before achieving his doctorate at Harvard.

Becoming a history instructor at Tarleton in 1933, he became an associate professor just a year later. He enlisted during World War II, serving as an artillery corporal in Europe. After the war, Smith returned as Tarleton’s head of the Department of History and Government, which later became the Department of Social Sciences.

According to Guthrie, Smith was among Tarleton’s most active scholars, writing two Texas government textbooks, numerous articles and two well-regarded booklets on government in the Lone Star State. He stepped down from department leadership in 1967 to return to full-time teaching.

His last six years at Tarleton saw Smith honored as Outstanding Educator in America (1971), Distinguished Faculty Member (1972), and finally Professor Emeritus following his retirement in 1973.

Upon his death in 1974, Smith directed his inheritance of more than a half-million dollars to go toward scholarships to help prospective students of Tarleton’s College of Arts and Sciences. The Dick Smith Scholarships still help educate English, mathematics, science and social science majors.

The Dick Smith Library, built in 1957 with additions in the late 1960s and in 1985, went through extensive renovations in 2004. The latest expansion into the old math building in 2014, added a student lounge, coffee bar, a dozen group study rooms and a classroom. The renovation supported the library’s role as a major resource for student study, team work and research as well as in providing access to technology, including a 3-D printer.

In 1998, Tarleton’s lynchpin agriculture department named its venerable campus building in honor of former department head Dr. Joe Autry, who had participated in dedicating the same building 47 years earlier.

The building, used since 1951, houses classrooms, laboratories, office space and a small auditorium for agriculture students.

Like so many of the school’s early supporters, Autry was a product of Stephenville schools prior to beginning his higher education at Tarleton, then a two-year college.

After studying at Tarleton, he earned his bachelor’s degree from Texas A&M before joining the Navy to serve in World War II. In 1947 he began a more than three-decade relationship with Tarleton, starting as an associate professor in 1947 and becoming the head of the Agriculture Department just four years later, a position he held for 16 years.

After earning his doctorate, Autry moved into the newly-created position of Vice President and Dean of Instruction in 1971. Additionally, he was part of a Tarleton contingent that traveled to Austin to witness the signing of the 1973 proclamation changing the name of the school to Tarleton State University.

His association with the Purple and White continued even after his retirement with part-time teaching assignments in the business administration department. Dr. Autry was chosen Distinguished Faculty Member in 1982 and was named Vice President Emeritus by the Texas A&M Board of Regents in 1984.

The O.A. Grant Humanities Building was named in 2007 to posthumously honor a faculty member who served during a critical time in Tarleton’s growth.

Grant, hired in 1948 as a political science professor, served in that capacity for almost 20 years before becoming the head of the social sciences department. He returned to teaching full-time in 1976.

Naming the building honored Grant’s “dedication and farreaching involvement with the university.”

Those characteristics were proved in 1965 as a small consortium of teachers, including Grant, pooled resources and paid for Tarleton’s first-ever African-American student to attend classes.

In 1954, he was awarded the Ford Foundation Grant for a year’s study at Stanford University. Grant was Tarleton’s first professor to receive the Minnie L. Piper Award for outstanding teaching in Texas colleges and universities, which he won in 1962. In addition, he received the Outstanding Educator of America in 1973.

Local recognition included the Tarleton Distinguished Teaching Award in 1981 and the Distinguished Faculty Member award in 1983 from the Tarleton Alumni Association.

After 39 years of service to the university, Grant retired in 1987. In light of his numerous contributions to Tarleton, Grant was conferred with the professor emeritus title by The Texas A&M University System. The Tarleton Alumni Association and the Tarleton Alumni Relations Office also honored Grant by

establishing the O. A. Grant Excellence in Teaching Award, which recognizes faculty members who have had a profound effect on the lives and careers of Tarleton students.

The building that bears Grant’s name, originally built in 1973, was upgraded to the tune of more than $13 million in 2014, adding needed classroom and office space, special study and resource areas such as the Writing Center, state-ofthe-art communications, broadcast and journalism learning environments and technology.

Dr. Barry B. Thompson had a memorable 1994, which concluded with his being named Chancellor of The Texas A&M University System.

Thompson served as chancellor until his retirement in 1999, but his trek through higher education began at Tarleton some 40 years before, when, as a student, Thompson was tasked with traveling to Austin to lobby for the first “Tarleton Bill” to make the school a fouryear institution. Unsuccessful in that attempt, he graduated with an associate’s degree and headed to Lubbock for his bachelor’s from Texas Tech.

Working as a teacher and administrator in West Texas, Thompson earned his master’s, then, while heading the Secondary Education Department at Pan American University, earned his Ph.D. from Texas A&M.

From there he accepted Tarleton President William O. Trogdon’s offer of the newly-created position of executive vice president. When Trogdon abdicated the presidency in 1982, Thompson began his own era at the helm.

During the Thompson administration, Tarleton’s campus added a new business building, new facilities for hydrology and engineering and the school’s first co-ed residence hall. Additionally, Dr. Thompson was at the helm when Tarleton’s enrollment topped 6,000 students, and when baseball was reinstated as a varsity sport.

Before he left to take over at West Texas A&M in 1990, Thompson also pioneered computer online registration and created the campus Office of Minority Affairs, now called Multicultural Services.

Tarleton’s Barry B. Thompson Student Center, a hub of campus activity, houses 14 organizational offices, the Tarleton bookstore, a post office and the Texan Food Court.

The building, originally called the Student Development Center at its 1994 dedication, was renamed in ceremonies in 2002 honoring Tarleton’s 13th president.

Following Thompson’s death in 2014 at the age of 77, his memorial service was held at the Clyde H. Wells Fine Arts Center and the ensuing reception was at the Student Center bearing his name.

Tarleton State University’s science building got a new title in 2014 as the edifice was named in honor of long-time professor and dean Dr. Lamar Johanson.

Johanson began his 40-year career at Tarleton as a biology professor prior to becoming chairman of biological sciences, then dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. In addition, he was the first executive director of Tarleton State University in Killeen, now Texas A&M University–Central Texas.

In 1961, after a stint in the Air Force, Johanson came to Tarleton. He took a four-year leave of absence to earn his doctorate in plant physiology and biochemistry from Texas A&M, returning to Tarleton in 1967 and remaining until his retirement in 2001.

Johanson’s time at Tarleton was marked by a keen interest in the school’s athletic programs. He served for two decades as a faculty

athletics representative, was a director of the Tarleton Texan Club and was one of the first recipients of the school’s All Purple Award. Plus, he was the president of the Lone Star Conference from 1997-1999.

He and his wife, Marilynn, in 2012 donated their ranch to Tarleton as a life estate gift. The 1,700 acres of farm and ranch land, including mineral rights, is in San Saba and Mills counties of Texas. The donation was estimated to be in excess of $5 million.

The Dr. Lamar Johanson Science Building, a $30 million facility featuring 160,000 square feet of computer labs, classrooms, lecture halls, research labs, an auditorium and planetarium was completed in 2001. The new structure replaced the original science building from 1931.

Johanson commented on the naming of the science building in his honor, thanking the university “for providing the place, the environment and the culture for me to do what I enjoyed the most – teach and work with students. Nothing is more satisfying.”

Serving as university President for nearly two decades, Dr. Dennis McCabe had a major influence on improvements both academic and in facilities.

Taking office in 1991, McCabe vowed to continue the progress started during the administrations of both Dr. W.O. Trogdon and Dr. Barry Thompson. By the time he retired in 2008, he had more than fulfilled that promise, guiding more than $100 million in construction projects and a ground-breaking partnership within The Texas A&M University System that extended Tarleton’s reach.

Tarleton’s sphere of influence expanded past Stephenville under McCabe as The Killeen campus of the University of Central Texas became Tarleton State University System – Central Texas on Sept. 1, 1999.

From the beginning, the new school had a definite Tarleton flavor as McCabe named Dr. Lamar Johanson the new entity’s first executive director. Johanson, part of the Stephenville campus for almost four decades, had been a professor and Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences.

A unique agreement between Tarleton, the A&M System and the new campus stipulated that after meeting established enrollment goals, the college became an independent university. That milestone was reached in 2009.

Now titled Texas A&M University – Central Texas, the Killeen school is home to more than 2,500 mostly non-traditional students studying in bachelor’s and master’s degree programs in three schools – Arts and Sciences, Business Administration and Education.

Students’ average age at TAMU-CT is 34 and most students attend classes on a part-time basis. Not surprisingly, given its proximity to Fort Hood, more than 40 percent of the student body has some affiliation to the United State military. In fact, there are extension facilities on the Army post.

At home, McCabe-led projects featured the university’s recreation sports complex and Tarleton’s first new dining hall in nearly eight decades. Plus, planning for the $24 million nursing building, the cuttingedge Southwest Dairy Center, and renovation and upgrades to the library and science building also happened under his guidance.

Former President Dr. Dennis P. McCabe speaks at the inauguration of Tarleton’s 15th President Dr. F. Dominic Dottavio.

Tarleton State University’s 100-year affiliation with Texas A&M has proved to be a boon for both schools, as well as for generations of Tarleton students.

While history has shown the decision to join with the Aggies was a solid one, decisions pertaining to Tarleton’s future, some which will impact students who have yet to be born, are already being made.

Under Tarleton’s 15th President, Dr. F. Dominic Dottavio, the university has doubled in size while maintaining a vision to be “the premier student-focused university in Texas and beyond.” Not only have new programs of study been developed in engineering, veterinary technology, fashion studies, geography, environmental sciences and other fields, but Tarleton has established academic centers in Fort Worth, Waco and Midlothian and offers degrees through its Global Campus online. A new College of Health Sciences and Human Services focuses attention on expanding fields such as nursing and social work while the new School of Criminology, Criminal Justice and Strategic Studies draws international attention to the university.

“Tarleton, with the support of The Texas A&M University System, has entered an era of dynamic growth and development, which

benefits not only north central Texas but the entire state and nation,” Dottavio notes. “Our economic impact on the region has surpassed $500 million a year, equating to more than 8,000 jobs. Our graduates — grounded in our core values of tradition, integrity, civility, leadership, excellence and service — have become vital contributors and leaders in their professional fields. We can look back and see how much of this was made possible by our affiliation with Texas A&M in 1917, and we can look forward and see the marvelous opportunities for our future as a member of the System.”

A future that includes new areas of study, more advanced degrees, and, of course, plans for state-of-the-art facilities from which to launch students’ academic careers into the next century.

Consider a planned $54 million, 170,000 square foot engineering building to support engineering, computer sciences and engineering technology programs. The facility will house new civil and environmental engineering programs, energy and mechatronics studies.