CROSS EXAM VOIR DIRE & Available In-Person, Livestream, & On-Demand! MARCH 2-3, 2023 The Whitehall, Houston, TX COURSE DIRECTORS: Stan Schneider, John Hunter Smith, Clay Steadman, & Patty Tress P: 512.478.2514 • F: 512.469.9107 • www.tcdla.com • 6808 Hill Meadow Dr, Austin TX 78736

Date: March 2-3, 2023

Location: The Whitehall, 1700 Smith Street Houston, Texas

Course Directors: John Hunter Smith, Clay Steadman, Stan Schneider, and Patty Tress Total CLE Hours: 14.50 Ethics: 1.0

A: Theater in the Courtroom | Bluebonnet A

B: Voir Dire in Sex Cases | Bluebonnet B

C: DWI Voir Dire| Cougar

C: Theater in the Courtroom| Bluebonnet A

A: Voir Dire in Sex Cases| Bluebonnet B

B: Theater in the Courtroom | Bluebonnet A

Group C: Voir Dire in Sex Cases| Bluebonnet B

A: DWI Voir Dire| Cougar

and Jennifer Lapinski

VOIR DIRE & CROSS EXAM SEMINAR INFORMATION

TCDLA :: 6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

March 2, 2023 Daily CLE Hours: 7.25 Ethics: 0 Time CLE Topic Speaker 7:45 am Registration & Continental Breakfast 8:10 am Opening Remarks John Hunter Smith and Patty Tress 8:15 am 1.0 Voir Dire

Jennifer Lapinski 9:15 am .75 Theater of Voir Dire Ron Estefan 10:00 am Break 10:15 am .75 Voir Dire Sex Cases Jeff Kearney 11:00 am .75 DWI Voir Dire David Burrows 11:45 am Lunch Line 12:00 pm 1.0 Lunch

Jessica Canter 1:00 pm Break 1:15 pm 1.0

Ron Estefan

Jeff

Group

David Burrows 2:15

Break 2:30

1.0

Ron

Group

Jeff Kearney

David Burrows 3:30 pm Break 3:45 pm 1.0

Ron Estefan

Jeff

David

4:45

Adjourn

Thursday,

101

Presentation: PowerPoints in Voir Dire

Group

Group

Kearney and Jennifer Lapinski

pm

pm

Group

Estefan

and Jennifer Lapinski Group B: DWI Voir Dire| Cougar

Group

Kearney

Group

Burrows

pm

Location:

VOIR DIRE & CROSS EXAM SEMINAR INFORMATION

Date: March 2-3, 2023

The Whitehall, 1700 Smith Street Houston, Texas

CLE Hours:

Ethics: 1.0 TCDLA :: 6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com Friday, March 3, 2023 Daily CLE Hours: 7.25 Ethics: 1.0 Time CLE Topic Speaker 7:45 am Registration & Continental Breakfast 8:10 am Opening Remarks Clay Steadman and Stan Schneider 8:15 am 1.0 Ethics Cross of Snitches Rob Fickman 9:15 am .75 Cross of Law Enforcement Letitia Quinones 10:00 am Break 10:15 am .75 Cross of Complaining Witness Lisa Greenberg 11:00 am .75 Cross of Expert Brent Mayr 11:45 am Lunch Line 12:00 pm 1.0 Lunch Presentation: Cross Exam 101 Michael Gross 1:00 pm Break 1:15 pm 1.0 Group A: Cross of Law Enforcement| Bluebonnet A Letitia Quinones Group B: Cross of Complaining Witness| Bluebonnet B Lisa Greenberg Group C: Cross of Expert| Cougar Brent Mayr 2:15 pm Break 2:30 pm 1.0 Group C: Cross of Law Enforcement| Bluebonnet A Letitia Quinones Group A: Cross of Complaining Witness| Bluebonnet B Lisa Greenberg Group B: Cross of Expert| Cougar Brent Mayr 3:30 pm Break 3:45 pm 1.0 Group B: Cross of Law Enforcement| Bluebonnet A Letitia Quinones Group C: Cross of Complaining Witness| Bluebonnet B Lisa Greenberg Group A: Cross of Expert| Cougar Brent Mayr 4:45 pm Adjourn

Course Directors: John Hunter Smith, Clay Steadman, Stan Schneider, and Patty Tress Total

14.50

Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association

Voir Dire & Cross Exam

Table of Contents

speakers topic

Thursday, March 2, 2023

Jennifer Lapinski Voir Dire 101

Ron Estefan Theater of Voir Dire

Jeff Kearney Jury Selection in Sexual Assault Cases

David Burrows DWI Voir Dire

Friday, March 3, 2023

Rob Fickman Cross Examining Rats and Snitches

Letitia Quinones Going Through the Back Door with the Issue of Race in Voir Dire

Lisa Greenberg Cross of Complaining Witness

Brent Mayr Cross Examination of the Expert Witness

Michael Gross Cross Exam 101

6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association

Voir Dire & Cross Exam

March 2-3, 2023 The Whitehall

Houston, Texas

Topic:

Voir

Dire 101

Speaker: Jennifer Lapinski

Trial Consultant at Cathy E. Bennett & Associates, Inc. 217 S Stemmons Fwy Ste 203 Lewisville, TX 75067 972.434.5879 phone jl@cebjury.com email

6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

Page 1 of 36 VoirDire101 Jennifer Lapinski Cathy E. Bennett & Associates, Inc. 2300 Highland Village Dr., Suite 470 Highland Village, TX 75077 (972) 434-5879 jl@cebjury.com Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association Voir Dire and Cross Exam March 2, 2023 Houston, Texas

INTRODUCTION

No matter how many times you have conducted voirdire, truly great lawyers are always striving to learn new things and to better themselves and their craft. I have been fortunate enough to work alongside so many incredibly talented criminal defense lawyers and am constantly inspired by the work that they do so well.

This document is split into three sections: Before Voir Dire, Conducting Voir Dire, and Additional Voir Dire Tips. I have also included materials that you can print and use during voirdire. It is my sincere hope that whether you are about to try your first case or your 100th, that you find these tips, tricks, and tools helpful the next time you are picking a jury.

Page 2 of 36

BEFORE VOIRDIRE

Great defense lawyers know that voirdiredoes not begin on the day you seat the jury. It begins from the moment you agree to take your client’s case. From thinking about the issues, to drafting a juror questionnaire, to knowing what to expect from your judge – all of that requires preparation well before the day of voirdire.

StartPreparationsEarly

The time to start thinking about your voirdireis not as your trial date nears. The most successful criminal defense lawyers start thinking about voirdireas they learn the case, from their first client meeting up until the day of jury selection. Whether it’s a legal pad or your laptop, you should begin corralling ideas and drafting voir dire questions from the moment you accept your case. The method is not as important as consistency. If you start thinking about voirdireearly and build it consistently over time, you will find as you near your trial date that you are fine-tuning your voirdirerather than preparing it from scratch. Remember, be consistent!

After you have set yourself up to start building your voirdireearly, the next task should be to start what we refer to as your “fear list.” A fear listshould identify any weaknesses in your case. In other words, if you lose the case, these are the reasons why. This is not an academic exercise, but a critical part of preparing for trial. It is vital to address these early and add to your fear list as necessary. You cannot outrun the weaknesses in your case, you must deal with them, and it is how you deal with them that determines your success.

Once you have identified the weaknesses in your case, prioritize the items on your fear list. Which weakness is the biggest problem? Which are issues, but not as critical? After prioritizing the weaknesses on your fear list, carefully go through them one by one. If there is a way to fix that weakness, move on to the next. If there is no fix, is there another approach you can take? See if there’s another factual route to get to the same conclusion. If there’s a different road you can take to get to the same destination, then you will need to voirdireon that new road. After you have reviewed your prioritized fear list, start thinking about how to turn any remaining weaknesses into strengths.

If, come trial, you are still faced with one or more weakness on your fear list, always be up front with the jury about your weakness, and if possible, try to be the one who brings it up first. The jury will forgive just about anything as long as you are honest about it, and even more so if you are the one to tell them.

Page 3 of 36

Great criminal defense lawyers are honest not only with the jury, but also with themselves. Be realistic about the weaknesses in your case, address them head on, and do so early on so you can continue to gather information and ammunition to turn those weaknesses into strengths.

DecidetheGoalofYourVoirDire

One of the first questions you must ask yourself is if you should conduct an elimination or education voirdire. In an elimination voirdire, your questions are focused on getting your unfavorable jurors off for cause. In an education voirdire, your focus is teaching your prospective jurors about the law or other concepts related to your case. Although your voirdirewill sometimes be exclusively focused on elimination or education, oftentimes it will need to be a combination of both. To determine where your focus should be, there are several factors to consider.

First and foremost is your case itself and the issues you must cover during voir dire. In a case with a straightforward fact pattern and few, if any, difficult legal concepts that require educating your prospective jurors, the focus will likely be on eliminating individuals who will require your client to testify, will convict on a lower burden of proof, or cannot consider the full punishment range. A more complicated case such as fraud or tax evasion, on the other hand, usually deals with complex legal concepts and technical terminology that are not common knowledge or easily understood and must be taught. The makeup of your jury panel the day of jury selection can ultimately dictate the direction of your voirdire. If you draw a really great panel, it is not necessary to focus on elimination, and you can instead educate all those really great jurors about the issues in your case. On the other hand, if you happen to draw a really adverse panel, you have to lock and load on eliminating as many unfavorable jurors for cause as you possibly can. Finally, the focus of your voirdireis also going to be somewhat dictated by whether or not you have a time limit. If you have unlimited time, you can structure your voirdireas a combination of both elimination and education questions as needed. However, if the court has given you only 30 minutes for attorney-conducted voirdire, you are almost always going to have to focus exclusively on elimination.

You also need to decide whether you are picking a not guilty jury or a punishment jury. A not guilty jury is one who believes, accepts, and would easily follow the judge’s instructions and the law with regards to the evidence and burden of proof. A punishment jury is one who believes, accepts, and would easily follow your suggestions on what an appropriate sentence is in your case. While each of these juries has its obvious benefits, we caution you not to try and select a jury that combines the two. Attempting to pick a

Page 4 of 36

jury with elements of both usually results in a blend of the worst of both worlds. This is why it is crucial to decide which type of jury is best suited for your case and develop your voirdireaccordingly.

JurorQuestionnaires

More and more courts, both state and federal, are permitting the use of juror questionnaires. Regardless of whether the court has previously allowed questionnaires, please ask. Some judges have said that they have never used juror questionnaires and would be open to doing so, but no one has asked! You also cannot expect a judge who has never before used a juror questionnaire to allow it when the first time you ask is the day of jury selection. Remember, the worst thing your judge can say is no, but you will never know if you never ask.

You must start the process sooner rather than later, at least three to four weeks before trial. Keep in mind that you will need time to draft the questionnaire, send it to the prosecutor for their agreement, submit the questionnaire to the court for their approval, then coordinate the logistics of your jury panel completing the questionnaire prior to voirdirewith the court. You simply cannot do all of that at the last minute.

When you draft the juror questionnaire, make sure that that questions are fair to both sides, proper, and are not argumentative or objectionable. Your questionnaire is unlikely to be approved by the court if you include questions that are argumentative or objectionable. The general rule is anything that is a proper voir dire question can be asked on the questionnaire.

Include a hardship question on your questionnaire. Your judge is much more likely to be convinced to take up hardships before voirdireif the jurors have already identified themselves and their hardships before voir dire has begun. Most judges also like a hardship question on the questionnaire because it reduces the likelihood of jurors educating each other on what to say to get excused. Your hardship question should also appear at the beginning of the questionnaire, with an instruction that the juror should complete the remainder of the questionnaire regardless of their answer.

Do not duplicate information that you will already have from a juror list or information from the jury summons. This information varies by jurisdiction. In some jurisdictions you only receive names, while in others you receive their name, age, education, employment, and more. Although it may be convenient for you to have all the jurors’ information in one place, you must look at it from the juror’s perspective. When

Page 5 of 36

you ask the jurors to answer the same questions again, they feel undervalued and unappreciated, which usually translates into less participation during voirdire.

Make sure you also include at least one scaled question on your juror questionnaire. Scaled questions ask your prospective jurors to select a number from a range in answer to a question, such as how strongly they agree or disagree with the law. For example, asking prospective jurors to choose a number on a scale of 0 (Very Uncomfortable) to 10 (Very Comfortable) that best represents their level of comfort with giving full and fair consideration to the full range of punishment for someone convicted of murder.

There are three questions you should include on every single juror questionnaire, at or near the end of your questionnaire:

(1) What three words or adjectives would you use to describe yourself?

Rather than asking the prospective jurors to select adjectives from a list, have them write down three words of their choice. By not giving the prospective jurors words to choose from, you gain valuable insight as to how each prospective juror sees themselves.

(2) Please list the three people you admire most, and please list the three people you admire least.

The prospective jurors’ answers to these questions can tell you their political leanings, how much and what type of entertainment they enjoy or dislike by the actors or celebrities they name, if they are particularly religious, or if they are social activists. Their answers can also tell you if what is most important to them are their personal connections because they list family members as the three people they admire most and former coworkers, friends, or spouses as those they admire least. This can also be significant information to consider when you need the jury to bond with your client. For example, if you have a client who is a devoted husband and father, but a prospective juror lists “Dad” as someone they admire least, you most likely do not want to take the risk of that person sitting on your jury. Someone who lists their father as someone they admire least usually has a good reason, and your client will start out behind with this juror simply because of the juror’s life experience with their own father.

(3) A catch-all question

Always include a catch-all question such as, “Is there anything else you feel the judge and the parties should know about you?”, “Is there any reason why you feel you could not or should not serve as a juror in this case?”, or

Page 6 of 36

“Is there any reason you would be unable or unwilling to serve as a juror in this case?” Never use the words “fair and impartial”, as all that accomplishes is to increase the likelihood of getting a fair and impartial answer instead of an honest answer. The goal with this question is to give the prospective jurors an opportunity and option to tell you anything that is on their mind that might affect their service.

You should also make sure that there is an instruction of what to do if a juror wishes to discuss their answer privately. This can be as simple as instructing the panel that they have the option to write the word, “Private,” if they wish to discuss their answer privately with the judge and lawyers. Finally, you should always include a catch-all question at the end of your questionnaire in case there is something the prospective juror wants the lawyers, parties, and/or the judge to know.

Coordinate questionnaire logistics with the bailiff or court staff in advance. Oftentimes the court will want to handle passing out and picking up the questionnaires without the parties’ participation for neutrality’s sake, but it never hurts to ask. Even if they decline, they will appreciate the offer.

Make sure you bring sufficient copies of the questionnaire, and always bring at least ten extra copies than you think you will need. You never know when the court may call extra jurors, one of the copies is missing a page, or someone spills a cup of coffee.

Make sure the jurors have a hard writing surface such as a clipboard or chipboard. Jurors will write more if it is easier for them to do so.

Bring black ink pens that do not smudge, such as ballpoint. Felt tip and gel pens tend to smudge, even those marketed as “quick dry”, especially for left-handed jurors. Make sure you have plenty of extra black ink pens—sometimes you get a dud when buying in bulk.

Bring someone to help you and have this person be in charge of the questionnaires. The only items in your hands during voirdireshould be your notes and/or a seating chart. You can keep your notes on the questionnaire unless you have to return the questionnaires to the court at the conclusion of voirdire. The person helping you should have all of your copies of the completed questionnaires, and if you need it during voirdire, they should be able hand it to you quickly.

Your juror questionnaire needs to be consistent with the amount of time you have to review it. The general rule in your typical case is no more than a one-page juror questionnaire is necessary. That said, not all cases are created equal. Ask yourself these questions when deciding how many pages your juror questionnaire should be:

Page 7 of 36

• How much time will I have to review completed questionnaires? If you have a week or more to review completed juror questionnaires, then your questionnaire can be several pages in length. If you have an hour or less, your questionnaire should never be more than one page.

• How many issues do I need to explore with the jury? If your case has a straightforward fact pattern, then a one-page juror questionnaire is probably all you need. If your case has multiple and/or complex issues, has received a great deal of publicity, or a long list of parties and witnesses to which the seated members of your jury should have no connection, then sometimes an extra page or two is simply necessary.

• Are there any sensitive topics that should be on the questionnaire? We know that jurors are already reluctant to speak up in a room full of strangers. Their reluctance increases exponentially if there are sensitive topics such as sexual misconduct, racial discrimination, or an issue that has recently affected many within the community. Jurors will often sit silently during voirdireon these topics simply because they do not want to describe their life experiences in front of others. They are much more likely to tell you about these same life experiences in writing.

• Will the prosecutor and/or the court be more or less likely to agree to a questionnaire if it is multiple pages? While certainly not at the top of the list, you still should consider if submitting a long questionnaire to the prosecutor or the court will be an exercise in futility. We have seen long, thoughtful questionnaires rejected by the court simply because it was perceived as too lengthy. Right or wrong, the end result was that questionnaire was not used even though someone had clearly spent considerable time on it. In other words, know your audience, or ask someone who does.

• Willtheuseof alongerquestionnairebenefittheprosecution more than you? Longer questionnaires are not always better. There are instances when the use of a longer questionnaire provides you with more information, but also provides the prosecution with more ammunition to get your good jurors off for cause. Only you know your case and the prosecutor well enough to make this call, but oftentimes less is more. With few exceptions, you can do more with a shorter questionnaire than a longer one.

Page 8 of 36

Regardless of the length and format of your juror questionnaire, you should always include a cover page. The cover page should always include the following:

• Why weare askingprospectivejurors to completea questionnaire. Always look at the process of jury selection from your prospective jurors’ point of view. They have waited to get through security, waited to check in with jury administrators, and waited to get to the courtroom. After all of that, they are now asked to complete a potentially lengthy juror questionnaire. You will virtually eliminate any pushback by telling the prospective jurors up front that the use of the questionnaire will shorten the process of jury selection.

• An assurance to the prospective jurors that their information will be kept confidential. Especially in this day and age, people are protective of their personal information, and rightfully so. If it is the policy of your jurisdiction, tell the prospective jurors when and how the questionnaires will be destroyed.

• General instructions. Always remember that this will be the first time many of your prospective jurors are reporting for jury duty. They need to know that their questionnaire must be completed by themselves with no outside help or influence, and their oath to answer honestly under penalty of perjury extends to the questionnaire.

• What the prospective jurors should do if they do not understand or do not want to answer a question. Again, this is one of those things that prospective jurors will not know unless you tell them. Let them know they have a way to alert the court if they do not understand a question or would prefer to speak privately.

• An instruction against conducting internet or other research, and the potential consequences if any prospective juror does so. It has become second nature to take out our phones and look up names and subject matters with which we are unfamiliar. Some will inevitably do it anyway, but if you want to greatly reduce the number of prospective jurors googling your case, instruct them that doing so will be subject to contempt of court charges and may be punishable under an Order from the Court.

• There are no right or wrong answers, just honest answers. Do not instruct your prospective jurors that you are looking for “fair and impartial” jurors, otherwise you will get fair and impartial answers rather than honest ones. Instead, ask your prospective jurors to be honest.

Page 9 of 36

If you are lucky enough to have lots of time, you obviously want to thoroughly review every completed questionnaire. Unfortunately, most of the time you will only have 30 to 90 minutes, or over the lunch break, to review completed questionnaires. Since you asked the court before choosing the length and format of your juror questionnaire, you should already know how long the judge will give you to review completed questionnaires.

If your time is limited, look at all the questions and identify the question(s) that could identify a potential challenge for cause. Those can range anywhere from connections to the complaining witness, exposure to pretrial publicity, or an inability to consider the full range of punishment, to a reason why they cannot serve. Those are the questions which you need to look at on every questionnaire. Anything that goes to cause or hardship, review first, and review JUST those answers. Do not look at any other answers before doing this. Next, review the answers to your one or two most important questions. In every questionnaire, you have one or two questions that are “magic bullet” questions. Magic bullet questions are those that identify who you need to get excused for cause, who you should try to keep, and who you need to follow up with. At the very least, your “magic bullet” questions will tell you something important about that person. If you have time remaining, then look at the answers to questions such as the individuals they admire most and least, words to describe themselves, age, and education.

You also need to have a method with which to organize all this information. We are huge proponents of using the index card method because index cards are easy to manually manage. Whatever method you use, group similar answers together: potential cause and hardship answers, magic bullet questions, and, time permitting, other answers of note. Hardships and reasons for a potential challenge for cause should be notated without exception. With regards to magic bullet questions, these answers should only be notated if the answer matters. For example, you will want to know which prospective jurors have family members in law enforcement. There will be a consistent place on the index card, seating chart, spreadsheet, or whichever method you choose to indicate this. For prospective jurors who do not have any family in law enforcement, leave that designated space blank. There is no need to use time and energy writing, “none.”

Page 10 of 36

Great defense lawyers are prepared trial lawyers. Know the law of your jurisdiction and case law, all local rules, and your judge and court personnel well in advance of voir dire. How many people will make up your jury panel? Will the judge impose a time limit on voirdire? How many peremptory strikes do you have? If applicable, how many strikes do you have for alternate jurors? Are strikes to the seated jury and alternate jurors done together or separately? When does your judge hear challenges for cause and hardships? Does your judge hear challenges for cause and hardships in front of or outside the presence of the jury panel? What is your judge’s propensity for granting excusals for hardships and challenges for cause? Is it standard procedure for the court reporter to keep a record of voirdire, or is that something you must request in advance? You need to be armed with the answers to all of these questions before the day of jury selection.

KnowYourJudge

Knowing your judge is essential to a successful voirdire. Find out if your judge has any written rules or unwritten customs of their own. Watch a jury selection in their court. Talk to someone who has tried a case recently in front of that judge for their insight. Many rules, customs, and preferences are completely within the judge’s discretion. Some questions to keep in mind include:

• Has your judge ever used a juror questionnaire? If not, do not let that automatically dissuade you from asking.

• Does the judge have any rules about visual aids, such as whether or not they can be used during voirdireor if you need to exchange with the prosecutor?

• Does the judge ask prospective jurors to stand or use a microphone when answering questions?

• Does your judge regularly impose time limits on voirdire?

• Does your judge typically handle hardship at the beginning or end of voirdire? We strongly believe that the judge should do hardship first, before the lawyers’ voirdire. The judge has to qualify valid excuses and hardships from invalid ones and give the jury panel examples.

• Does the judge allow additional questioning for challenges for cause or do they rule based on the record?

• Does your judge handle hardships and challenges for cause in front of the panel or outside their presence?

• How much time will your judge give you to confer with your co-counsel and client on peremptory strikes?

• Does the judge have any particular preferences or pet peeves?

Page 11 of 36

BePrepared

KnowtheCourtroom

Being prepared for voirdirealso means being familiar with the courtroom. The best thing you can do is to be honest with yourself: even if you have appeared in this courtroom for pretrial hearings or other matters, have you reallypaid attention to its conduciveness to conducting voirdire? Probably not, because you were focused on the task at hand. Familiarize yourself with the layout and floor plan of the courtroom. Make note of where the jury box and counsel tables are in relation to the bench as well as the gallery. Is the furniture fixed or can it be moved? And if it is movable, be sure to get the court’s permission before you rearrange anything. Then, determine where and how the prospective jurors will be seated.

Courtroom technology is another critical item to familiarize yourself with prior to voirdire. What technology, if any, is already available for your use? Will the court allow, and is the courtroom able to handle, bringing your own? You do not want to bring equipment if the courtroom does not have adequate or available electrical outlets or space. You definitely want to test the technology before you stand to begin your voirdire. Ask the court if you can do a trial run with the technology you plan to use during voirdire at a time where the courtroom is not being used. There are corresponding logistical issues to consider with the use of any courtroom technology. Wherever your prospective jurors will be seated, will they all be able to see the projection screen, or would more than one monitor on rolling carts be better for the space? Does your judge have their own monitor, or do they need a sightline to your projection screen? Even if the judge has a monitor, the projection screen should never block the view between the prospective jurors and your judge. You should also take note of what type(s) of audio equipment the court uses and/or has available. Does the court have devices to assist prospective jurors who are hearing impaired? Does the court use microphones for the lawyers at their counsel tables, at the podium, or ask the lawyers to use a wireless microphone during voirdire? Does the court ask prospective jurors to use a microphone when answering questions, and if so, how many will there be? Voirdirecan go a lot slower if there is only one microphone. It is nothing that you cannot handle, but it is all part of being prepared.

If there are microphones affixed to the counsel tables, keep in mind that they all may be on one master switch. Meaning, if the bench’s microphone is on, so is yours. Ask the court if your microphone can be disabled while you are not speaking. If not, be mindful of live mics!

Page 12 of 36

KnowtheProsecutor

Part of any good voirdirepreparation is also knowing your prosecutor. Your goal should be to learn what to expect from the prosecutor, during both your voirdireand theirs. A great source for learning about prosecutors is to speak with other lawyers who have gone up against them in court. If possible, get voirdiretranscripts from other trials. When asking for feedback on a prosecutor’s voirdire, find out what they typically say. Lots of lawyers have go-to openers and questions they always ask. Do they always open with a joke? If so, maybe work in, “. . . this is no laughing matter . . .” into your own introduction. Do they always reveal something personal about themselves? For example, many lawyers tell prospective jurors about their military service or their children. If you know the prosecutor does this, bring up your own personal anecdote. If the prosecutor has certain voirdirequestions that they always ask, reframe a couple and incorporate them into your voirdire. Also ask about any habits or patterns. Do they always object midway through the defense lawyer’s voirdireto disrupt their flow? If you know this ahead of time, you’ll be ready if it happens and can arm yourself with a response, for example, “Your honor, we exchanged PowerPoints in advance per your request, and counsel had no objection at that time. I believe this is a proper question.”

The best way to learn how a prosecutor conducts their voirdireis to watch them pick a jury in another case. Do not send an associate or paralegal. You do not have to stay for the whole trial, but take the time to watch the prosecutor conduct voirdire. The information and insight you will receive is worth the time investment. Do not let the first time you personally see them conduct voirdirebe right before you conduct yours.

Always assume that the prosecution has done the same homework on you. This is reason enough to not follow the same script every time you pick a jury, but this goes double in smaller jurisdictions. You never know when you might have a repeat juror! But with regards to the prosecutor, do not make it easy on them to anticipate your entire voir dire. If you are putting in the time and effort to get to know them, they very well may be doing the same.

KnowWhatInformationisAvailableAboutYouandYourClient

One aspect that should never be overlooked during your voirdirepreparation is knowing what information is available to prospective jurors about your client, as well as about yourself. Always assume that prospective jurors are googling you and your client. Prospective jurors are often left waiting for long periods of time with nothing to do. Even though they are instructed not to do any online research about the case or the parties, we know from experience that many do anyway. This goes double for any courthouse

Page 13 of 36

that offers free Wi-Fi. You must know what the search results contain to know what those jurors may see.

The biggest offender by far of unintentional oversharing, for both lawyers and clients, is social media. It is really difficult, if not impossible, for jurors to change their opinions of you and your client once they have seen your social media postings. If your social media accounts are not private, stop reading this and immediately set your social media accounts to the highest privacy settings available. Then, contact your clients. They should change their privacy settings, suspend their accounts, and under no circumstances should they post, text, email, or otherwise share anything about the trial. Advise your clients that, if they have concerned or curious family members or friends, the client needs to tell them thank you for their well wishes, but that their lawyer has advised them that they cannot share anything about the trial until it is over. Recognize that this will be harder for some clients than others. As an extra step, you must remind the client every night not to share anything about the trial until a verdict is reached.

Your law firm’s website is something else to consider. If prospective jurors are googling your name, it is likely one of the first search results listed. Like your social media presence, it is hard for prospective jurors to change their opinions of you once they have viewed your website. Keep in mind that prospective jurors will view your website with a completely different frame of reference than prospective clients.

Perhaps most importantly, be honest with yourself about your relationship with your client. Prospective jurors spend a lot of time waiting, and the ones not googling you and your client are watching while they wait. Prospective jurors watch other prospective jurors, the judge and court personnel, and the prosecutor, but they also watch you and your client. Always be mindful that every interaction with (or not with) your client will be noticed!

PracticeMakesPerfect

Practice your voirdire. The most successful trial lawyers always practice their voir direin advance of jury selection. Practice by yourself as well as in front of others. If you know the court will impose a strict time limit, time yourself during your practice runs. No matter your experience, practice makes perfect.

Page 14 of 36

CONDUCTING VOIR DIRE

BringSomeonetoHelpYou

One of the most important and helpful things you can do for yourself is to have someone with you to be your eyes, ears, and scribe. Your job during voirdireis to get as many responses from as many prospective jurors as possible in order to effectively exercise your challenges for cause and intelligently use your peremptory strikes. Very few lawyers are able to accomplish this while simultaneously taking good notes, keeping track of those who qualify for a challenge for cause, and recording answers to scaled questions. Having someone to assist you with jury selection is a game changer when you are able to focus solely on your voirdire.

AlwaysUseJurorNumbers

Use the prospective jurors’ names whenever possible, but always use their juror numbers. The only item consistently in your hands during voirdireshould be a seating chart with the names and numbers of your prospective jurors. If you have the ability to memorize names, use it, but make sure you always use juror numbers as well. We recommend telling the jury panel at the beginning of your voirdirethat while you may refer to each of them by their number, your intent is not to make them feel like a number, but saying their juror number really helps both the court reporter and the person assisting you, and you truly hope they understand.

Use laminated cards with juror numbers. Print juror numbers in bold font as large as the page will allow and have each page laminated. Bring these laminated cards with you and ask the court if they will permit their use during jury selection. The court can place them in each prospective juror’s seat and ask them to please raise their card rather than their hand when answering a question or asking to be heard. When jury selection is over, offer to leave them with the court. It is a small investment in future cases you try in that courtroom.

SpeakLikeaPerson,NotaLawyer

Your prospective jurors know you went to law school and already assume you are a smart person. Some will not understand, and others will be unimpressed if you use complicated language when simpler words will do.

Page 15 of 36

TellthePanelThereAreNoRightorWrongAnswers

Before you ask your first question, let your prospective jurors know that there are no right or wrong answers. If you tell the jury panel you are looking for fair and impartial jurors, you are conditioning them to give you fair and impartial answers. Instead, tell them there are absolutely no right or wrong answers, only honestanswers.

UseVisualAids

Using visual aids in your voirdireis an incredibly helpful tool. You must assume you have some visual learners on the jury, but in general we also know that people learn and recall information better if they are presented this information as images with text or verbal instruction. Even if your focus during voirdireis elimination rather than education, you still want your prospective jurors to understand your questions so they are able to intelligently answer whether or not they have a bias or prejudice. Not only do people better learn and understand concepts when visual aids are used, but the use of visual aids also helps the jury panel get and stay engaged.

If you are not at least using PowerPoint, Keynote, or similar during your voirdire, please start. Using programs such as these is an easy introduction to using visual aids during your voirdire. Using visual presentation software also helps with asking scaled questions much more smoothly, as you can display the question and the scale from which the prospective jurors should answer. Another benefit of using visual presentation software is it can double as your outline to help you stay on track.

The one caveat about using visual aids in your voir dire is this: if you are not accustomed to doing this, do not let your next trial be the first time. Meaning, practice your entire voirdiremore than once with the visual aids before you use those visual aids in court.

The following are some basic do’s and don’ts with regards to using any type of visual presentation software during your next voirdire.

DO prepare your slides, but DON’T assume your judge will allow you to use them. If your judge says you cannot use one or more of your slides, you have to be ready and able to adjust your slide or do without that question.

DO include proper questions, but DON’T try to sneak in objectionable questions. It is not helpful to you if your judge disallows your PowerPoint because of one objectionable or improper question. That said, the general rule is if your question is a

Page 16 of 36

proper question, then it is equally proper to have it appear on a PowerPoint slide. In other words, if you can say it, you can show it.

DO use your slides as your outline to help you stay on track, but DON’T read your slides to the jury.

DO print and bring three copies of your PowerPoint deck (one for your judge, one for the prosecutor, and one for yourself), but DON’T email or share your PowerPoint with the prosecutor prior to the morning of voirdire(unless, of course, the court requires you to do so).

DO have a slide for each scaled question, but DON’T have a slide for every single question. Asking scaled questions to your entire panel go a lot smoother when the panel members can see the answer choices and the question on your slide.

DO use layman terms rather than legalese whenever you can, and DON’T assume spellcheck will catch all typos.

DO limit the number of slides in your presentation, but DON’T limit yourself unnecessarily. In general, limit the number of slides to twenty or less. That said, use your best judgement if you have a lot of issues to cover. Just do not design a presentation to have fifty or one hundred slides. The reality is you will lose the interest of the jury panel if you have that many slides.

DO get creative, but DON’T assume your presentation will translate from computer screen to projector screen. Test your presentation with a projector in the courtroom or in conditions as close to those in your courtroom as possible. View all your slides from all angles (far away, close up, etc.). Is the text size large enough? Do colors remain true on the slide once the slide is projected?

DO use color to emphasize certain words or phrases, but DON’T use yellow as a text color. Yellow text almost never works once projected. If your goal is to draw the panel’s attention to a particular item or text on your slide, black text that has been highlighted almost always looks better on a screen than yellow text.

InternetSearchesofJurors

Unless your jurisdiction or judge expressly forbids it, an internet search of your jury panel is another useful resource. Internet searches and social media can tell you what is important to your prospective jurors, their political affiliation, involvement with their community, religious affiliation and/or church memberships (which can be particularly helpful in smaller jurisdictions, as several of your prospective jurors may

Page 17 of 36

attend the same place of worship), and whether they have children or pets, as well as their hobbies and leisure time activities. An internet search of your jury panel can be accomplished by a member of your trial team or law office, by your investigator, or there are companies that offer large-batch internet searches as one of their litigation services.

There are a few important things to remember when performing an internet search of your jury panel. While companies who regularly perform such searches likely ensure the following as a matter of standard procedure, it is still worth mentioning whether your internet search is performed by a litigation services company, trial consultant, your investigator, or if you perform the internet search in-house:

• Do NOT, under any circumstances, communicate with the prospective jurors. This includes direct messages, posts on their social media pages, or even “liking” one of the prospective juror’s posts. This can be viewed by the court as improper communication with a juror.

• If a prospective juror’s social media accounts are private, do not send any type of friend request or otherwise request access to view their account. Again, this is improper communication.

• Before the internet search begins, have the person conducting the internet search sign out from all their social media platforms or use a computer on which no one has or could sign into their social media accounts. Most social media platforms have the ability for the user to see who has been viewing their accounts. While technically not improper, you run the risk of the juror viewing it as a violation of privacy if they know you or anyone connected to your firm has been looking at their social media presence, so it is best avoided.

• Know the court’s position on internet searches of the jury panel. Some courts require that you disclose that you have performed such a search not only to the prosecutor and the court, but also to the jury panel. If the court requires that you disclose an internet search to the panel, our position is you are better off not performing one at all.

Regardless of who performs the internet search, make sure you think about what type of information will be most useful to you, and ask the person or company performing the search to limit their search to those topics. For instance, we know that people generally like people like themselves. What information can you find out about the prospective jurors that is similar to your client, key witness(es), and/or your expert(s)?

Biases towards or against certain groups or issues can also be discovered through an internet search. For example, if your client is a police officer, it would be very helpful to know which jurors “like” posts about Defund the Police and which “like” Back the Blue posts.

Page 18 of 36

Lastly, your search results will not be helpful if they are overly broad or contain so much information that you just do not have time to absorb it all. Ask the person or company performing your internet search to give you the results in the form of a onepage summary for each juror.

TypesofVoirDireQuestions

There are three main types of voirdirequestions: Open-ended, Closed-ended, and Scaled. All three are valuable types of questions but serve different needs.

Open-ended questions are truly wonderful in that you learn so much about your prospective jurors. Unlike yes or no questions or multiple choice, open-ended questions give your prospective jurors the opportunity to tell you how they feel in their own words. To use open-ended questions most effectively, limit them to your most important topics.

The downside of open-ended questions is that unfortunately they take the most amount of time in practice. The reality is, if you have a very short time limit, asking a lot of open-ended questions may take more time than you have. Consider a panel of sixty prospective jurors and a 30-minute time limit: in this scenario, that only allows each prospective juror 30 seconds to answer one question. Obviously, that is not the best use of your time. However, asking an open-ended question such as the following examples to someone who has been silent is a great way to learn something about that person, even when navigating a short time limit:

• What is your opinion about the criminal justice system?

• When you saw [Client’s name] and heard the charges against him, what was the first thought that came to your mind?

• In your opinion, is there a benefit to the community to sentencing a first-time offender to probation instead of prison? Why or why not?

Another way to effectively use open-ended questions is on a juror questionnaire. Try to include at least one or two open-ended questions in your juror questionnaire. This is particularly important if your time to conduct voir dire will be limited, but it is an effective use of open-ended questions even if you have unlimited time. This way you get feedback from your entire panel on one or two of your most important topics before you ask your first voirdirequestion.

Regardless of how much time you have to conduct voirdire, be careful that one prospective juror doesn’t eat up all your time. This is, of course, good voirdireadvice in general, but is especially important when asking open-ended questions.

Page 19 of 36

Closed-ended questions give you absolutes. They are helpful when you need information on education and experience, such as prior jury service, involvement in a criminal case as a complainant or witness, or employment experience in a specific industry, but they often require follow-up questions. When used on a juror questionnaire, a closed-ended question should always include a follow-up, such as, “If YES, please explain” or “Why do you feel this way?” During voirdire, closed-ended questions are most effectively used when trying to get someone off for cause:

Q: So what you’re telling us is, even though the law says the State has the burden of proof, you personally would require me to prove my client is not guilty. Is this correct?

A: Yes, that’s correct.

Q: Is this a strongly held belief that you have?

A: Yes, it is.

Q: And this strongly held belief will affect the way you view this case, from listening to the evidence all the way to deliberations, is that fair to say?

A: Yes, that’s fair.

Q: And because you have this strongly held belief, no matter what anyone says, even the judge, you will require me to prove my case instead of requiring the State to prove theirs, fair to say?

A: Yes. I just think you should have to show proof that he didn’t do it.

Q: Thank you, I really and truly appreciate your honesty. Because you disagree with the law in this case, is it okay with you if I ask the judge to excuse you?

A: Sure.

In the example above, the lawyer has just gotten this prospective juror to confirm not once, but multiple times that they will require the defense to prove their client’s innocence rather than hold the State to their burden. Any judge would be hard-pressed not to grant a challenge for cause based on this exchange.

Closed-ended questions can be used as an opener to get someone on the panel talking who has not yet spoken, but just like using closed-ended questions on a juror questionnaire, requires some follow up questioning. A good question in this scenario is, “If you were the plaintiff, would you want a juror like yourself on your jury?” Regardless of their answer, ask them to tell you more.

Be mindful of someone who has only answered closed-ended questions and provided little to no follow up. Perhaps this person is just shy, but you do not have much information on someone who has only given you one-word answers. It might be time to ask this person a follow-up question or an open-ended question. You do not want to have someone on your jury that you know little to nothing about.

Page 20 of 36

Scaled questions are all about measuring belief systems, and in the most efficient manner, to determine if those belief systems will be beneficial or detrimental to your case. Scaled questions allow you to get the opinion of every single panel member on important issues. Depending on the size of your panel, you can get an answer from every single member of your jury panel within two or three minutes.

On their own, scaled questions are not intended to get someone off for cause, however, you can use them to identify your unfavorable jurors. Then, you can focus on those jurors and use closed-ended questions to get them off for cause. Scaled questions are also not commitment questions. You are asking the prospective jurors about their beliefs or opinions, not a commitment to a specific scenario or set of facts.

Scaled questions only work the way in which they were intended if you keep everything consistent. First, the scale you use should be the same for all your scaled questions. Which scale you use is less important than keeping your scale the same for all your scaled questions. Whichever scale you choose, make sure it has an uneven number of choices, so your median is a true neutral.

Do not label your median number with the word, “Neutral”; only label the lowest and highest ends of your scale. Eyes often naturally gravitate to the center of the screen, and if “Neutral” is the first word your prospective jurors see, it can condition them to give you a neutral answer instead of an honest answer.

Next, decide if your “good” answers are high or low and keep it the same for all your scaled questions. For example, if you use a scale of 0 to 10, all your “good” answers should be the choice represented by 10 and “bad” answers should be the choice represented by 0. By keeping your scale consistent, you create a scoring system that can be used when it comes time to exercise peremptory strikes. If you have two jurors for which you are considering using your last peremptory strike, you can look at their overall “score” to decide which of the two individuals you strike.

Do not use too many or too few scaled questions. In order to use scaled questions as an overall scoring system, you have to ask at least two scaled questions on two different topics. But do not use too many scaled questions, either. A good general rule is to ask no more than two scaled questions for every 15 minutes you have for voirdire. Also, scaled questions work best when you are able to show both the question and the scale on a PowerPoint slide or similar visual aid. This way the panel does not need to remember the question or the scale, nor do you need to repeat the question or scale very often, if at all.

Page 21 of 36

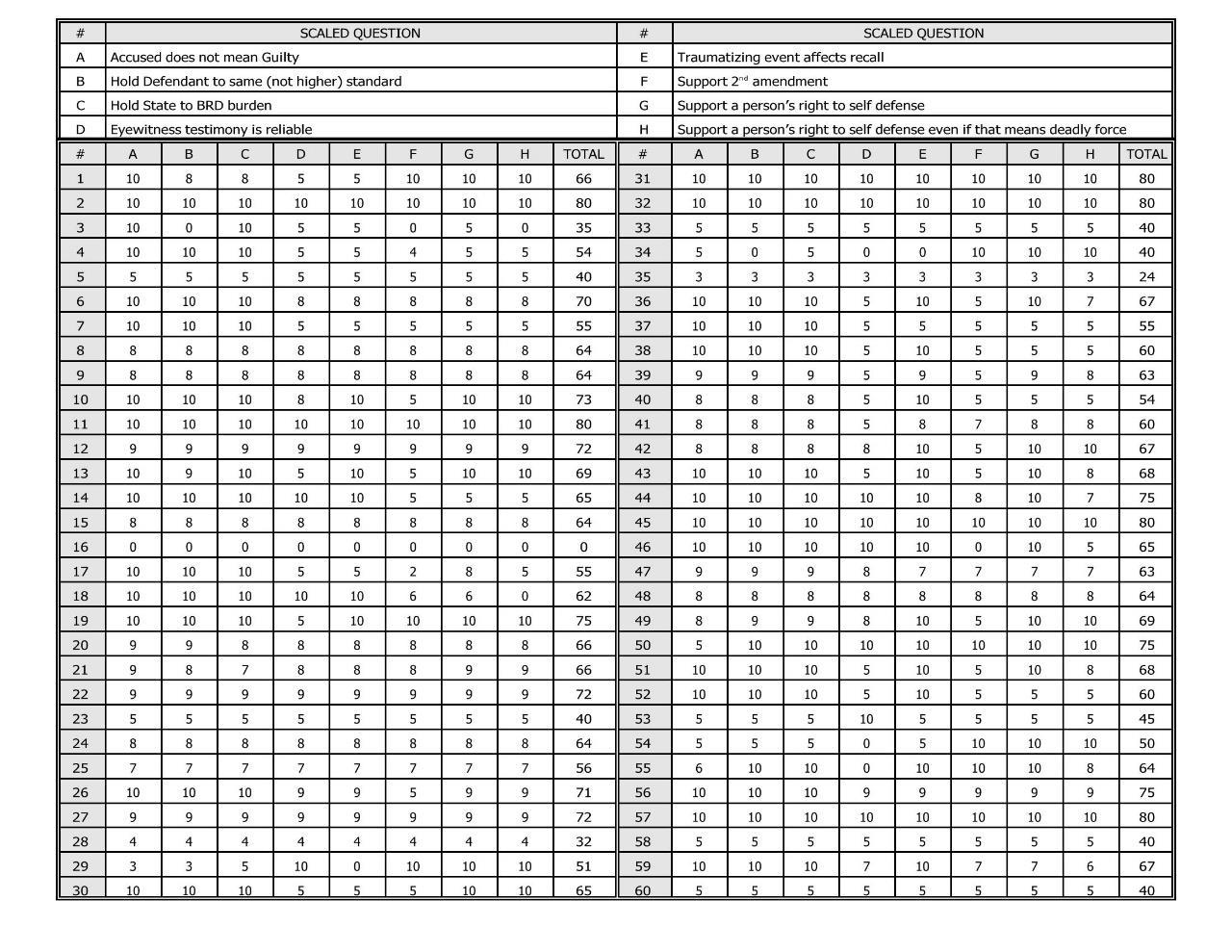

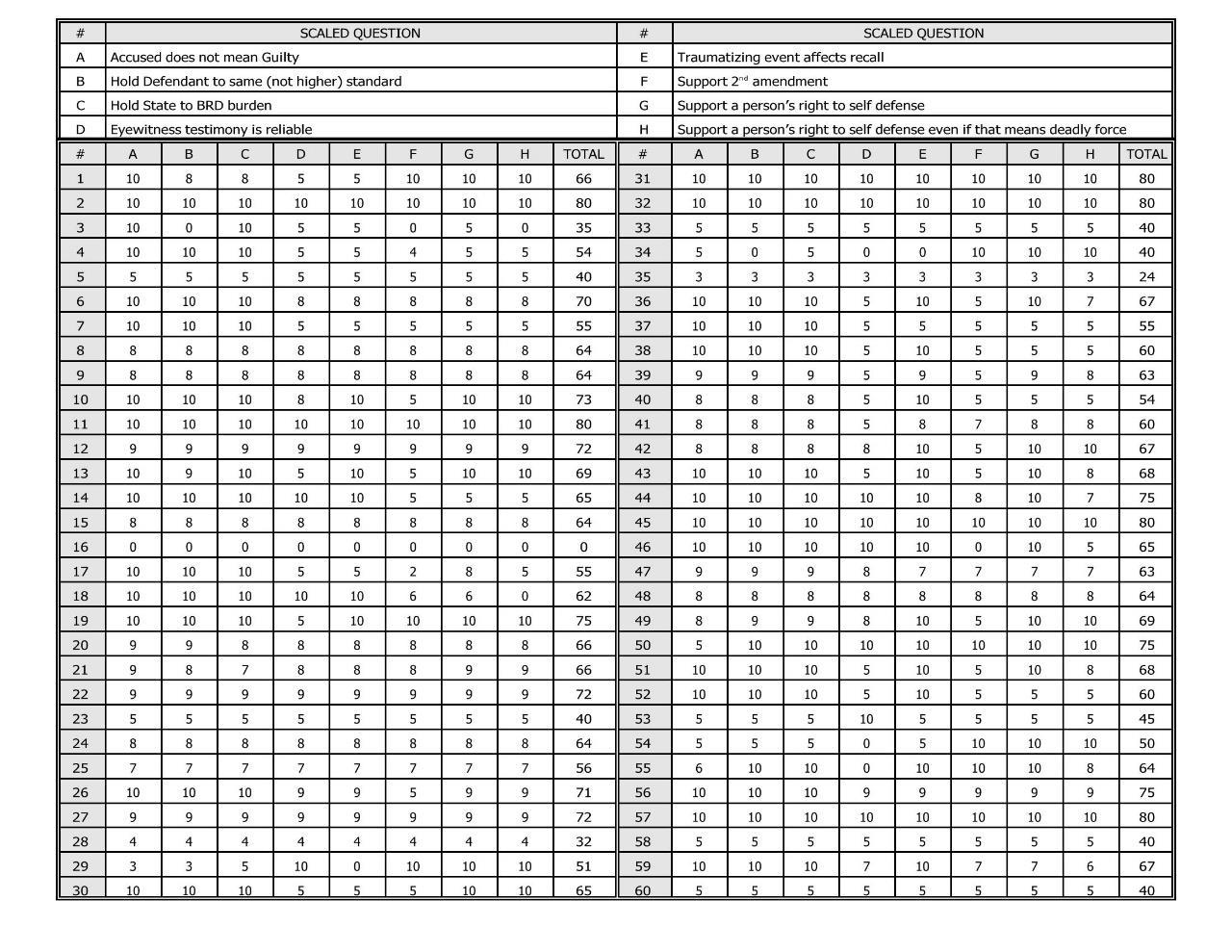

Using the scaled question chart is essential to organization of your scaled question answers. At a glance you can see the answers to every single scaled question and the overall score for every member of your jury panel. In the example below, eight scaled questions were asked on a scale of 0 to 10. All of the worst answers for the defense were represented by a 0 answer, and all of the best answers for the defense were represented by an answer of 10, but the prospective jurors were instructed that they could choose any number within the 0 to 10 scale. With this scale, the most favorable overall score for the defense would be 80.

As you can see, out of the first five prospective jurors, Juror No. 2 would be the most favorable juror for the defense, and Juror No. 3 would be the most unfavorable juror. In this example, you should try your best to get Juror No. 3 off for cause. While Juror No. 3’s answers to the scaled questions are not enough by themselves to challenge them for cause, you have now identified Juror No. 3 as an individual who likely cannot follow the law of self-defense, and you can proceed accordingly.

Page 22 of 36

Next look at Juror Nos. 1, 4, and 5. If you only had one peremptory strike left, which one would you choose? Knowing nothing else about these jurors, Juror No. 5 is probably the most likely candidate for exercising your last peremptory strike. When the judge has only given you 10 minutes to exercise your peremptory strikes, having a scoring system created by your scaled questions becomes an unbelievably helpful tool.

When using scaled questions, do not forget to look at individual answers as well. Consider Juror No. 4: This juror’s answers to the first three scaled questions were 10, but their answer to the final scaled question was 5. If you are picking a not guilty jury, Juror No. 4 is a good choice to leave on the jury. However, if you are picking a punishment jury, it would not be advisable to leave someone on the jury who told you they were Neutral or Not Sure (which is what a 5 answer would indicate in this example) when asked about whether or not they supported a person’s right to self-defense even if that meant using deadly force. In fact, you could try to get Juror No. 4 off for cause using the same line of questioning for Juror No. 3.

Scaled voirdirequestions are truly wonderful tools that allow you to find out how every single prospective juror feels about a certain topic. However, every so often when asking scaled questions, a prospective juror might say, “My answer isn’t up there”, or gives an answer that is not an option, such as 7.5 instead of 7 or 8. There can be a few reasons why a prospective juror would do this. Sometimes the juror thinks they are a comedian. Sometimes the juror is a mathematician, an engineer, or otherwise just truly does not think in terms of whole numbers. Sometimes the prospective juror feels so strongly that they give you a negative number or a higher number than the highest value on your scale. In the event this occurs, thank the juror, tell them you understand how they feel, and then ask, “Out of the options on the scale, which number comes the closest to your opinion?” Most of the time the prospective juror will give you an answer. Thank the juror again, and then continue asking your scaled question to the rest of the panel. If the juror still will not choose an answer from the options on the scale, do not push it, just move on. By trying once and moving on, the remainder of the panel will likely see that one prospective juror as the troublemaker and the rest of the panel will give you their answers without further interruption.

Treat the scaled question chart the same way as your notes, in that they are attorney work-product and therefore privileged. You are under no obligation to share them with the prosecutor or the court.

Page 23 of 36

IncludeQuestionsAboutLifeExperiences

Do not make the mistake of having your voirdirebe just about opinions on, and ability to follow, the law. While those are of course important, you need to know more about your potential jury. One of the ways to learn more about your prospective jurors is to ask voir dire questions about their life experiences. Voir dire questions on life experience are usually asked through the use of closed-ended questions. For example:

• Have you, any family members, or close friends ever worked in law enforcement, either currently or in the past?

• Do you know anyone who has experienced any type of unwanted or forced sexual contact?

• Do you know anyone who has ever been involved in a criminal case as a victim, witness, or the defendant?

While voirdirequestions on life experience, by themselves, are not sufficient to get people off for cause, they can be used to identify possible challenges for cause. In order to use this information to establish a valid challenge for cause, you must then ask follow-up questions to determine that the juror has a bias due to their life experience. For example, say you have a panel member who tells you that their father is a police officer. If you do not explore this further, the fact that their father works in law enforcement is not enough for most judges to grant a challenge for cause. However, if you follow up with questions about the juror’s experience with their father being in law enforcement and how it has affected them, and then they admit that they cannot be fair to someone accused of a crime because of that experience, now you have established that the juror cannot be fair to both sides, which is a valid challenge for cause that should be granted.

Catch-all questions are also voirdirequestions on life experience, but do not make them so broad that you inadvertently identify a good juror for you (and a challenge for cause for the prosecution). If you ask, “Is there any other reason why you feel you cannot be a fair juror in this case?”, this may invite a prospective juror who is great for your case to disclose that they cannot be fair to the prosecution. Instead, consider asking, “Is there anything about an experience in your life that would cause you to start this case favoring the State?”, or “Is there anything in your life experience, background, or any reason at all you cannot be fair to [Client’s name]?” Phrasing your question in this way invites those unable to be fair to your client to talk themselves into a challenge for cause. The lesson in using catch-all questions in your voirdireis to make sure the wording of your question is tight.

Page 24 of 36

Looping

One of the most powerful and effective voirdiretechniques is called looping. First, the lawyer asks one prospective juror a question and the juror responds. Next, the lawyer uses that juror’s name, repeats the juror’s exact words, and then asks another juror for a reaction to what the first juror said. A third prospective juror is then asked to respond to the answers given by the first two jurors, repeating their answers exactly and always using their names. Through the looping technique, the members of the panel are educating each other. By repeating the juror’s exact words, any juror who disagrees is, essentially, disagreeing with another panel member rather than the lawyer. Using the jurors’ names makes them feel valued and appreciated and inspires them to keep talking. In short, looping makes the jurors more likely to share honest feelings and opinions.

Pick your battles with looping and choose the ones you cannot lose. You do not want to lose an otherwise good panel. The only exception is inoculating jurors who are likely candidates to serve on the seated jury to a specific concept, such as burden of proof. As a general rule, do not loop your good answers. All that does is identify who the prosecutor will strike. Loop your BAD answers instead, especially when you are contending with a limit on your time. When looping bad answers, always thank the juror for being honest. This will make it much more likely for others who feel the same way to speak up. By thanking jurors who give you bad answers, it gives permission to others to tell you their opinion because now they are not alone in their belief or opinion. This is important because you are getting your worst juror to identify other bad jurors. Remember to keep your poker face: voirdireis when you want the bad answers, not when the jury is reading the verdict.

Another way to handle a bad answer is to compare it with a good answer and then ask who agrees with whom. Say to the panel, “You see, that’s the beauty of the jury system, we are all entitled to our own opinions and beliefs. You heard Mrs. Smith say that she believes the burden of proof should be lower than beyond a reasonable doubt, but Mr. Jones said if beyond a reasonable doubt is the law, then that is the burden of proof he will hold the state to in this case. I want to see who agrees with Mrs. Smith and who agrees with Mr. Jones. Mr. Doe, let me start with you. Who do you agree with, Mrs. Smith or Mr. Jones?” You can then go juror by juror, row by row, and ask each person which juror they agree with instead of asking the panel whether or not they agree with you.

Page 25 of 36

UseActiveListening

There are two types of listening: Inactive and Active. Inactive listening is when you hear what someone says. Active listening is when you understandwhat someone says. Most of us tend to be inactive listeners because it’s easy. Active listening is much harder. Try actively listening to a teenager and you will know exactly what we mean. With active listening, focus on the answer and not on what your next question will be. The best way to demonstrate to someone that you are actively listening to them is by repeating some of the key words they just used. For example, a prospective juror might tell you that they have already formed an opinion about your client’s guilt by saying, “I know what I read, and I definitely have opinions about this case.” The trial lawyer using active listening would respond with, “What I hear you saying, Ms. Jones, is that because you know what you read, you have already formed an opinion about this case before any evidence has been presented, is that fair to say?” The prospective juror will feel heard and that her opinion is validated and will be more inclined to agree with you when you begin developing your challenge for cause on her. You can also use active listening as you use the looping technique: “Ms. Jones just told us that because of what she read, she has already formed an opinion about whether my client is not guilty or guilty. Does anyone else feel like Ms. Jones, that you too have already formed an opinion about my client based on what you heard, read, or seen before you came to court today?” When you use this technique of active listening, people really feel like they are being heard and they tend to believe you, like you, and gravitate to you.

Page 26 of 36

ManageJurors’Expectations

Part of what makes jury service so unpleasant for potential jurors is not knowing what to expect. You have the power and opportunity afforded you during voirdireto speak directly to the jurors, and you can use that opportunity to manage their expectations.

One way to manage the prospective jurors’ expectations during voirdireis to tell them how much time you have or how many topics you will cover. In other words, give the prospective jurors a road map to your voirdire. This gives the jurors a way to gauge how far along you are and, more likely, how close you are to being finished. Another way to accomplish this is, instead of using slides or a legal pad for your voirdireoutline, use index cards and place them face down on your counsel table after covering the topic on the card. Your jurors will see when you are close to finishing by how many cards remain in your hand.

Another way to manage the jurors’ expectations is to tell them what to expect during the trial if they are seated on the jury. This can include lowering expectations of a witness who you know will not come across well: “I fully expect that no one on the jury will like my first witness. He is someone who mumbles and is very uncomfortable looking people in the eye when he speaks.” You can also set expectations for yourself. Some lawyers who plan on being aggressive with an adverse witness tell the panel that they will go straight for the jugular if the witness is lying. Then, they ask the jury panel if this will offend anyone. If anyone tells you they will be offended you can use that to develop a challenge for cause, but more importantly, now your jury knows what to expect from your witness, the evidence, or the way you try the case.

The last portion of managing juror expectations is that the jury will forgive anything as long as you are truthful. They will forgive the gruesome photos if you have warned them ahead of time and asked the jurors for their permission. They will forgive the lengthy video if you have already told them that it was cut down from eight hours of footage. Some lawyers disclose learning disabilities or speech impediments, because if they don’t, they run the risk of the jury thinking typos are laziness instead of dyslexia, or stumbling over words is nervousness or incompetence rather than a persistent stutter. By disclosing such things about themselves, these lawyers have shared something very personal (which is humanizing), gives a reason for any perceived missteps, and asks for the jury’s permission and forgiveness, even though it’s for something they cannot help.

Page 27 of 36

ChallengesforCause

Once prospective jurors have identified themselves and acknowledged that they cannot be fair or follow the law, now you need them to confirm that this is how they feel, no matter who is asking the question. This is what we refer to as the Cause Coffin. You must use the appropriate language to lock in your bad jurors:

• You won’t change your mind, no matter what anyone asks, fair to say?

• You feel very strongly about this, don’t you? Is it fair to say that it would be impossible to set aside those feelings, given how strong those feelings are?

• No matter who asks you about this, whether it’s the prosecutor or even the judge, you’re not going to give them a different answer because this is really how you feel, fair to say?

• That sounds to me like an answer you’re not going to change, am I correct?

You must know the magic words for your jurisdiction, and you have to incorporate those words into your cause questions. It is also very important that you end with, “If the prosecutor or the judge asks same kinds of questions, your answer will be the same, correct?” By doing this, you are letting the juror know they can anticipate the prosecutor’s attempt at rehabilitation and you are empowering the juror to stand their ground.

Always, alwaystell the juror who you will later be challenging for cause that it is okay that they have these opinions or feelings, and never forget to thank them for their honesty. This exponentially increases the likelihood of any other jurors who share these feelings to speak up, whether you invite them to do so or not.

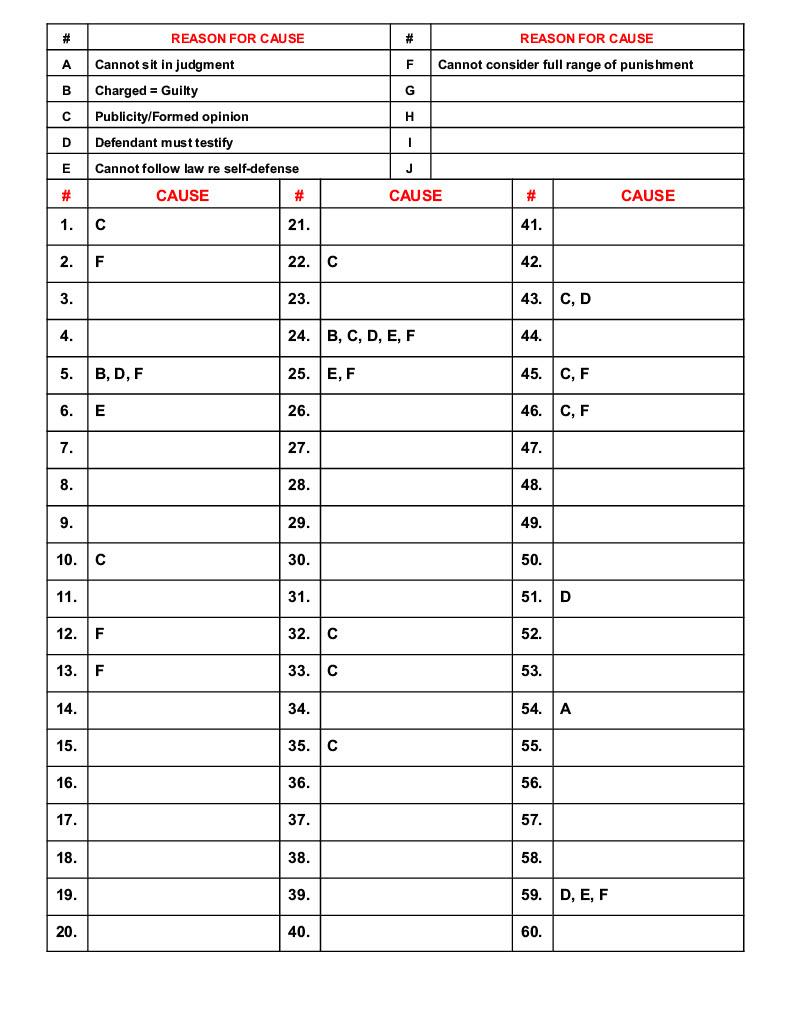

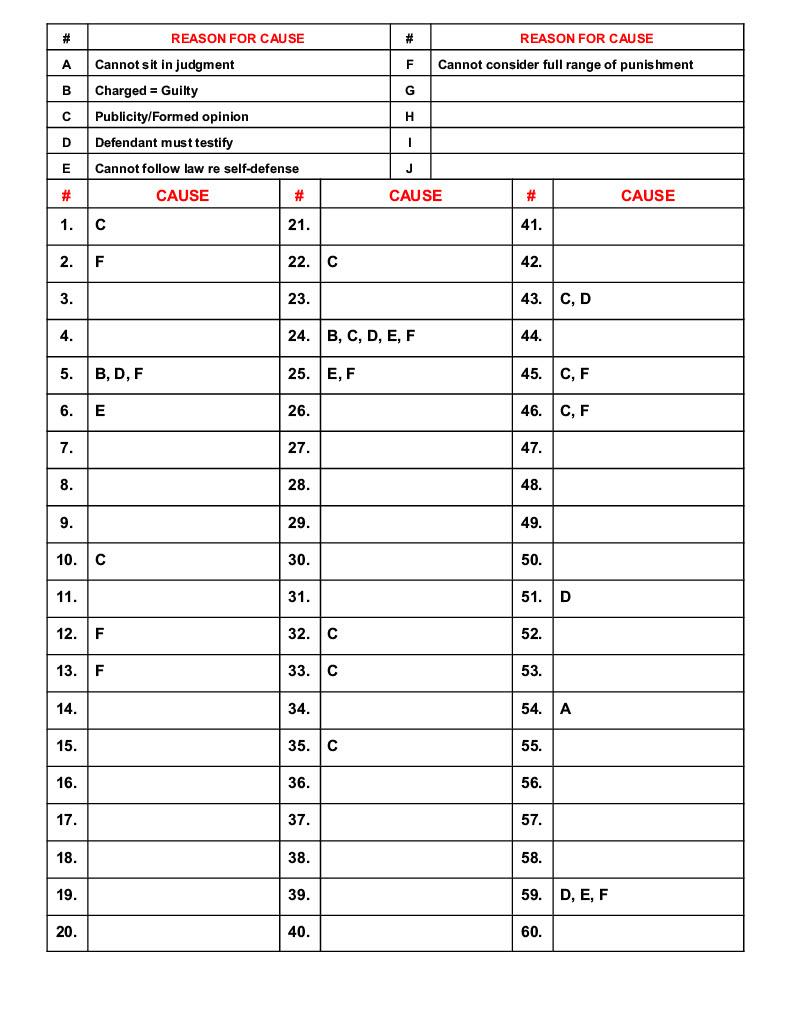

The Challenge for Cause chart is a way to organize all your challenges for cause in one place, eliminating the need to quickly create a separate list. The chart on the following page displays what a completed Challenge for Cause Chart might look like after your voirdire.

Page 28 of 36

In the example above, you could make challenges for cause for nineteen jurors (Nos. 1, 2, 5, 6, 10, 12, 13, 22, 24, 25, 32, 33, 35, 43, 45, 46, 51, 54, and 59) for a variety of reasons. Let’s look at the first five jurors. By using the key at the top of the Challenge for Cause Chart, you can see that Prospective Juror No. 1 stated during voir dire that they had heard or seen publicity about the case and have already formed opinions (C), Prospective Juror No. 2 said that they cannot consider the full range of punishment (F), and Prospective Juror No. 5 said they believed that someone charged with a crime was presumed guilty (B), that they would require the defendant to testify

Page 29 of 36

(D), and they cannot consider the full range of punishment (F). The other sixteen challenge for cause candidates have additional and varying reasons to make those challenges, such as an inability to sit in judgment (A), and/or an inability to follow the law regarding self-defense (E). The Challenge for Cause Chart also easily shows you which prospective jurors have more than one basis for a challenge for cause.

You now have every single prospective juror on one page and the basis for your challenge. When making your challenges for cause, this allows you to go down your list in numerical order and clearly and quickly state the basis for each of your challenges. When a challenge for cause is granted, you can strike through that juror on your chart. Then, when making peremptory strikes, you can easily see if there are any prospective jurors for whom you made a challenge that was not granted.

Remember, treat your Challenge for Cause Chart just like your notes. It is work product, so you are not obligated to share this with the prosecutor or the judge.

EffectivelyExercisingPeremptoryStrikes

Many trial lawyers have been in a situation where they are asked to submit their peremptory strikes immediately or with very little time to confer. If you have used your index cards and Challenge for Cause Chart, you should already know on which jurors most, if not all, your peremptory strikes will be used. The following are tips and tricks for exercising your peremptory strikes quickly but effectively:

• Plan ahead and do not get caught off guard with regards to time. Ask before voirdirebegins how much time the judge will give you to confer with your team before submitting your peremptory strikes.

• Knowing your math as it applies to the strike zone and/or your local rules comes into play.

• Use your index cards. Lay out the cards for the jurors who are within the strike zone on a table. Turn over the index cards for those you will definitely strike, turn the index cards sideways for those you might strike, and place a sticky note or flag on cards you are confident the prosecutor will strike.

• Always volunteer to use the jury room to confer with your team so the prosecutor cannot see your index cards, Challenge for Cause Chart, or Scaled Question Chart. There is absolutely no reason to show them your system.

Page 30 of 36

• Do not only pay attention to who you will be striking, pay attention to who remains. Be cognizant of what the jury will look like if you strike certain people.

• In close calls, use your scaled questions as a scoring system. Meaning, if it comes down to two prospective jurors on whom you were considering using a peremptory strike, but you only have one peremptory strike available to use, look at how those two prospective jurors answered your scaled questions. The prospective juror with the lower overall score is usually the one on whom you should exercise your last peremptory strike.

BatsonChallenges

In 1986, the Supreme Court ruling in Batsonv.Kentuckystated that peremptory challenges could not exclude a juror on the basis of race, as doing so would violate the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. The protections of Batson have been broadened by the courts over the years to include ethnicity (Hernandezv.NewYork, Allenv.Hardy) and gender (J.E.B.v.Alabamaexrel.T.B.). There have also been lower court rulings in recent years that indicate that this protection may eventually be extended to sexual orientation and gender identity as well.

When making a Batsonchallenge, not only must you know the law, but you also must know your judge and the remedy of putting people back on the jury. The main factor is timing. Your Batsonchallenge needs to be made before the jury is sworn in and the judge excuses the rest of the panel. For example, many judges will tell the parties who the members of the seated jury are before the official seating and swearing in of the jury. That is a perfect opportunity to raise Batsonif appropriate. Before the jury is sworn in, but also before panel is reseated or worse, excused.

The other factor is the ability to look at the prosecutor’s notes to see if they wrote anything that shows a bias. If their notes only indicate the prospective juror’s race, ethnicity, or gender, and they cannot articulate a race, ethnicity, or gender-neutral reason for their peremptory strike, most judges will err on the side of caution and grant your Batson challenge. If your judge denies your Batson challenge, make sure you clearly articulate your reasons for making the challenge on the record. Having a gut feeling that the prosecutor is making their strikes based on a prospective juror’s race, ethnicity, or gender will not be enough for the judge to side with you. Use clear and specific language. Remember, if the need arises, the person reviewing the record will not have been in the courtroom with you when you made the challenge.

Page 31 of 36

ADDITIONAL VOIR DIRE TIPS

ChooseYourWordsCarefully

It is very important to consider who your audience will be. Your jury panel will likely be made up of individuals from a cross-section of the community, which means the panel members will likely span different generations. The first rule of thumb is to leave any stereotypes at the door. Individuals born in 2000, who are members of Generation Z (a/k/a “Zoomers”), are now in their twenties. In 2023, the generation known as Millennials are already in their thirties, and many are parents. Generation X is middle aged. Baby Boomers are retiring and eligible for Medicare. The point is, your perception of “older” and “younger” generations is likely skewed depending on many factors, not the least of which is which generation you are a member of yourself.

Be mindful of the language and terminology you use. One example is the phrase, “ . . . and now, the other side of the story.” This was something Paul Harvey, an American radio broadcaster, would often say during his broadcasts. The phrase was adopted by many trial lawyers for several years because Mr. Harvey was popular, most jurors had at least heard the phrase before, and it lent itself well to getting the point across that there are two sides to every story. Although Mr. Harvey consistently worked in the broadcasting industry until his death in 2009, that was well over a decade ago, and the majority of jurors no longer get that reference.

Millennials and Generation Z tend to abbreviate words, sometimes down to a single letter, such as the use of “v” instead of “very” or “p” for “pretty” (as in, “I’m p excited”). Individuals within these generations also frequently use acronyms, such as JOMO (joy of missing out) and tbh (to be honest), but acronyms are often seen as lazy or frustrate older jurors. Some words (or new meanings for words) have been invented by these generations, such as stan, flex, salty, and lit. These words should never be uttered in a courtroom in an attempt to bond with jurors from these generations. Being completely honest with yourself, if you know that your child, niece or nephew, or other child you know well would cringe if they heard you use a certain word, you should not use it in the courtroom. When in doubt, don’t. Older jurors will not know what you mean, and younger jurors will not think you are cool.

Skewing your speech to only favor older jurors is just as problematic. Words and phrases such as loaded, snatched, low-key, keep it up, and knock yourself out are unfamiliar to younger jurors or have different meanings. If you want to be understood by your entire jury panel, it is far better to use language that will be understood by your entire jury panel.

Page 32 of 36

BodyLanguageSpeaksVolumes

Open body language is critically important during voirdire. It communicates to the jury panel that you are receptive to listening to their honest feelings and opinions. Here is a list of tips to ensure you maintain open body language:

1. Whether sitting or standing, uncross your arms. Crossing your arms communicates conflict and creates a physical barrier between you and the jury panel.

2. Do not cross your legs while standing.