Defending Sex Crime

Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association

speakers topic

Thursday, December 1, 2022

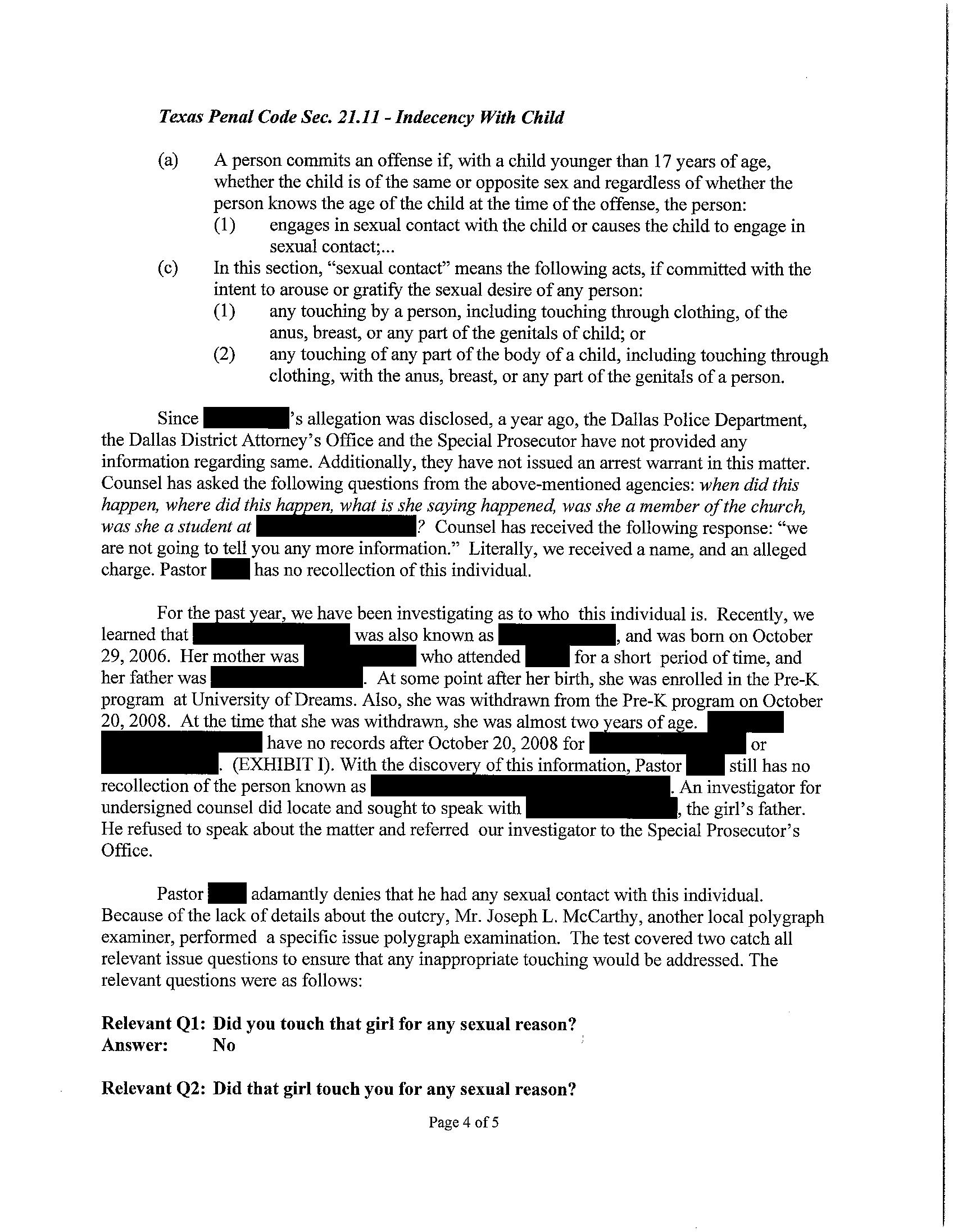

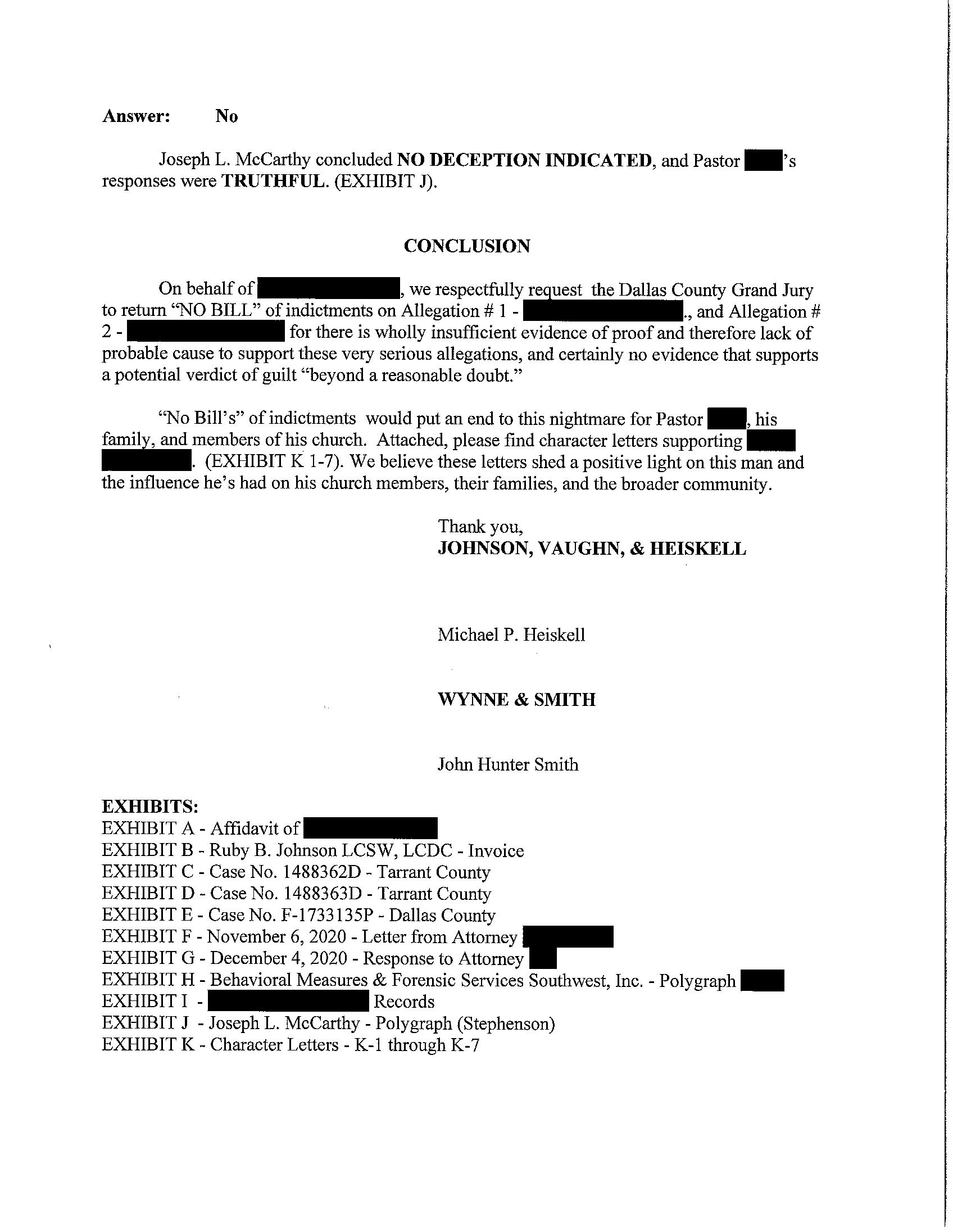

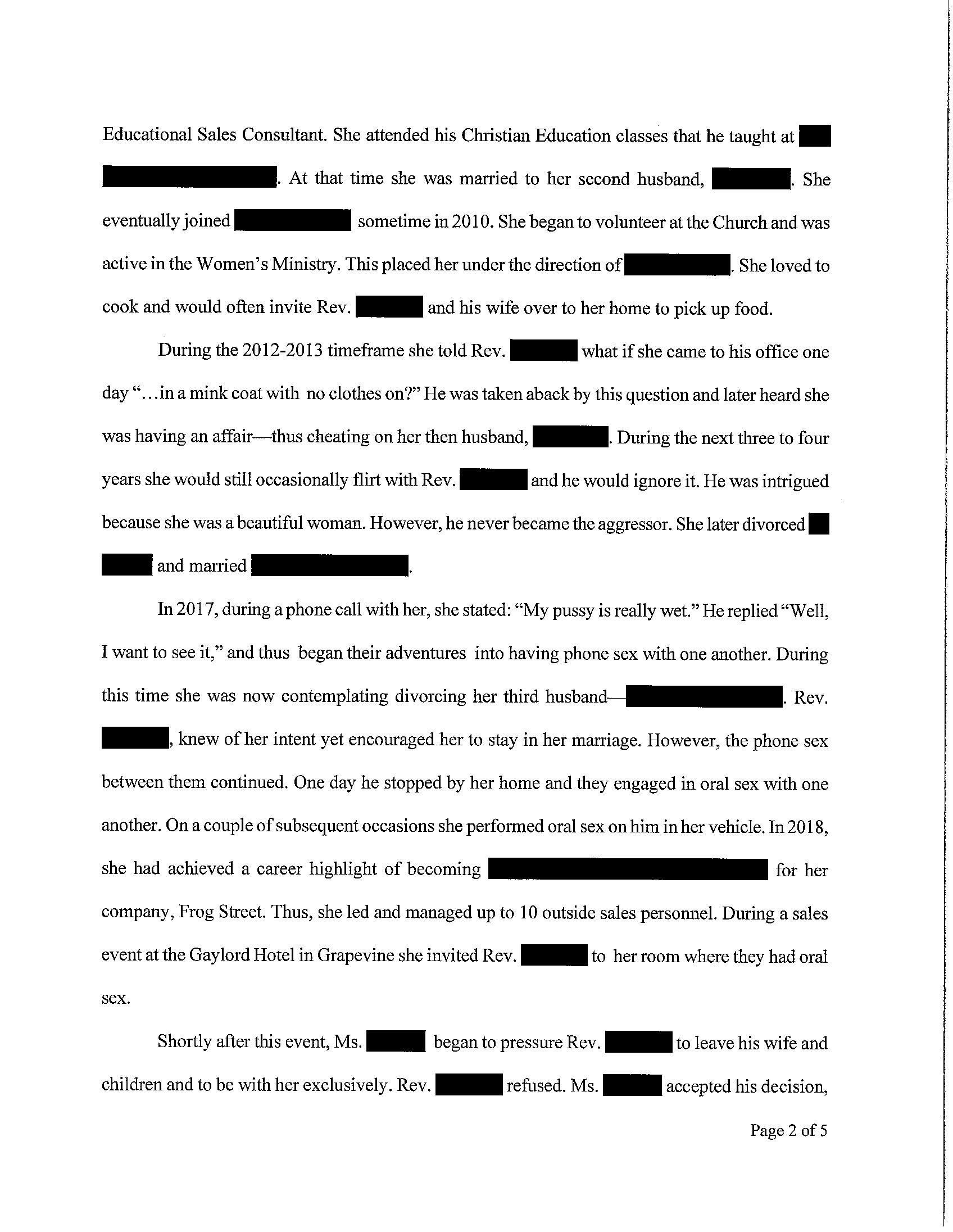

Michael Heiskell Grand Jury Packets

Eric Davis Cross of Child

Alyse Ferguson Mental Health and Mitigation

Sam Bassett Ethical Issues: Defense of Sex Crimes

Frank Sellers Computer Crimes: Child Porn and Solicitation

Friday, December 2, 2022

Dr. Stephen Thorne Understanding the Role of Childhood Memory

Gerry Morris Voir Dire in Sex Cases

Michael Gross Punishment and Collateral Consequences in Sex Crimes

Clay Steadman Investigation of Sex Crimes and Creative Motions

Brian Roark Evolution of Sex Crimes and Title IX in the New Age

6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

Date December 1 2, 2022

Location Magnolia Dallas 1401 Commerce St., Dallas, TX

Course Director Kerri Anderson Donica, Mark Daniel, and Jeff Kearney

Total CLE Hours 13.0 Ethics: 1.0 ###

Thursday, December 1, 2022

Daily CLE Hours: 7.0 Ethics: 1.0

Time CLE Topic Speaker

7:45 am Registration and Continental Breakfast

8:25 am Opening Remarks

8:30 am 1.0 Grand Jury Packets Michael Heiskell

9:30 am 1.0 Cross of Child Eric Davis

10:30 am Break

10:45 am 1.0 Sexual Assault Exams and Understanding Injuries Dr. Nancy Downing

11:45 am Lunch on Your Own

1:00 pm 1.0 Forensics Interviews and False Accusation Cases Dr. Aaron Pierce

2:00 pm 1.0 Mental Health & Mitigation Alyse Ferguson

3:00 pm Break

3:15 pm 1.0 Ethical Issues: Defense of Sex Crimes Sam Bassett Ethics

4:15 pm 1.0 Computer Crimes: Child Porn and Solicitation Frank Sellers

5:15 pm Adjourn

Date December 1 2, 2022

Location Magnolia Dallas 1401 Commerce St., Dallas, TX

Course Director Kerri Anderson Donica, Mark Daniel, and Jeff Kearney

Total CLE Hours 13.0 Ethics: 1.0 ###

Friday, December 2, 2022 Daily CLE Hours: 6.0 Ethics: 0.0

Time CLE Topic Speaker

8:00 am Registration and Continental Breakfast

8:25 am Opening Remarks

8:30 am 1.0 Understanding the Role of Childhood Memory

Dr. Stephen Thorne

9:30 am 1.0 Jury Selection Gerry Morris

10:30 am Break

10:45 am 1.0 Punishment and Collateral Consequences in Sex Crimes Michael Gross

11:45 am Lunch on Your Own

1:00 pm 1.0 Investigation of Sex Crimes and Creative Motions Clay Steadman

2:00 pm 1.0 Experts Witness and Challenging Expert Testimony

3:00 pm Break

Nicole DeBorde Hochglaube

3:15 pm 1.0 Evolution of Sex Crimes and Title IX in the New Age Brian Roark

4:15 pm Adjourn

December 1-2, 2022 Magnolia Dallas Dallas, Texas

Johnson, Vaughn, and Heiskell 5601 Bridge Street, Ste 220 Fort Worth, TX 76112 817.457.2999 phone 817.496.1102 fax firm@johnson-vaughn-heiskell.com email www.johnson-vaughn-heiskell.com website

6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

December 1 2, 2022 Magnolia Dallas Dallas, Texas

Speaker: Eric J. Davis

Chief of the Felony Trial Division Harris County Public Defender’s Office 1201 Franklin St. Rm 13 Houston, TX 77002 713.274.6730 phone 713.437.8563 fax Eric.davis@pdo.hctx.net email

6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

Cross-examination is perhaps one of the most fundamental components of an accused’s rights at trial. Through cross examination the accused is able to challenge the evidence and assertions against him. Through cross examination, lies can be exposed and the truth advanced. Effective and meaningful cross examination can vindicate the innocent. Despite the intrinsic value of this constitutional right to ensurejustice,numerouspeopleaccusedofcrimesare deniedeffectivecross examination in their cases some are denied this tool of justice because of the courts… others because of their advocates.

Cross examination is one of the most difficult trial skills to master. Few attorneys have the raw talent to conduct an effective, impromptu cross examination. Most lawyers struggle with cross examination. Besides talent; there are numerous factors that impact counsel’s conduct of cross examination including training, experience, preparation, organization and creativity. To an extent, courts have restricted cross examination in some cases.

It is myhope that through this paper, you will be presented with an effective tool to enable you to conduct an effect cross examination regardless of your level of skill or expertise. It is also the goal that the experienced practitioner will be presented with a tool to enable him or her to sharpen their skill as a cross examiner.

The Sixth Amendment’s Confrontation Clause provides that, “In all criminal prosecutions, the Accused shall enjoy the right . . . to be confronted with the witnesses against him.” The United States Supreme Court has held that this bedrock procedural guarantee applies to both federal and state prosecutions. Pointer v. Texas, 380 U.S. 400, 406, 13 L. Ed. 2d 923, 85 S. Ct. 1065 (1965).

And in Crawford v. Washington, 541 U.S. 36, 42 52 (U.S. 2004), the Supreme Court expanded an accused’s right to cross examine.

The Supreme Court has observed that the right to confront one’s accusers is a concept that dates back to Roman times. See Coy v. Iowa, 487 U.S. 1012, 1015, 101 L. Ed. 2d 857, 108 S. Ct. 2798 (1988); Herrmann & Speer, Facing the Accuser: Ancient and Medieval Precursors of the Confrontation Clause, 34 Va. J. Int'l L. 481 (1994). The framers of the Constitution would get this concept from the common law. English common law has long differed from continental civil law in regard to the manner in which witnesses gave testimonyin criminal trials. The commonlaw traditionisoneoflivetestimonyincourtsubjecttoadversarialtesting,whilethecivillawcondones examination in private by judicial officers. See 3 W. Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England 373 374 (1768). Specifically, in Crawford the Supreme Court observed that history supports two inferences about the meaning of the Sixth Amendment:

First, the principal evil at which the Confrontation Clause was directed was the civil-law mode of criminal procedure, and particularly its use of ex parte examinations as evidence against the accused. It was these practices that the Crown deployed in notorious treason cases like Raleigh’s; that the Marian statutes invited; that English law’s assertion of a right to confrontation was meant to prohibit; and that the founding-era rhetoric decried. The Sixth Amendment must be interpreted with this focus in mind. Accordingly, we once again reject the view that the Confrontation Clause applies of its own force only to in court testimony, and that its application to out of court statements introduced at trial depends upon "the law of Evidence for the time being." 3 Wigmore § 1397, at 101; accord, Dutton v. Evans, 400 U.S. 74, 94, 27 L. Ed. 2d 213, 91 S. Ct. 210 (1970) (Harlan, J., concurring in result). Leaving the regulation of out of court statements to the law of evidence would render the Confrontation Clause powerless to prevent even the most flagrant inquisitorial practices. Raleigh was, after all, perfectly free to confront those who read Cobham's confession in court.

This focus also suggests that not all hearsay implicates the Sixth Amendment's core concerns. An off hand, overheard remark might be unreliable evidence and thus a good candidate for exclusion under hearsay rules, but it bears little resemblance to the civil-law abuses the Confrontation Clause targeted. On the other hand, ex parte examinations might sometimes be admissible under modern

Cross Examination By: Eric J. Davis, Assistant Public Defender Harris County Public Defender’s Office eric.davis@pdo.hctx.nethearsay rules, but the Framers certainly would not have condoned them.

The text of the Confrontation Clause reflects this focus. It applies to "witnesses" against the accused in other words, those who "bear testimony." 2 N. Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828). "Testimony," in turn, is typically "[a] solemn declaration or affirmation made for the purpose of establishing or proving some fact." Id. An accuser who makes a formal statement to government officers bears testimony in a sense that a person who makes a casual remark to an acquaintance does not. The constitutionaltext,likethehistoryunderlyingthecommon-lawright of confrontation, thus reflects an especially acute concern with a specific type of out-of-court statement.

Crawford, 541 U.S. at 42 52. Through Crawford, an accused has the right to examine the maker of any testimonial statements against him. The Supreme Court through the most unlikely source, Justice Scalia, affirmed that the Constitution ensures that every testimonial assertion against the accused should be challenged.

Without Cross examination, the accused is left with his life and libertybeing decided bylies, untruths and examination in private by judicial officers. There is great value in meaningful cross examination.

Courts and the rules of evidence provide some limitation on cross examination. Texas Rule of Evidence 611 provides,

a) Control by the Court; Purposes. The court should exercise reasonable control over the mode and order of examining witnesses and presenting evidence so as to:

(1) make those procedures effective for determining the truth; (2) avoid wasting time; and

(3) protect witnesses from harassment or undue embarrassment.

(b) Scope of Cross Examination. A witness may be cross examined on any relevant matter, including credibility.

(c) Leading Questions. Leading questions should not be used on direct examination except as necessary to develop the witness's testimony. Ordinarily, the court should allow leading questions:

(1) on cross examination; and

(2) when a party calls a hostile witness, an adverse party, or a witness identified with an adverse party.

Cross Examination By: Eric J. Davis, Assistant Public Defender Harris County Public Defender’s Office eric.davis@pdo.hctx.netA. Preparation. Effective and meaningful cross examination starts with thorough and active preparation. Know your client’s story, the facts and evidence against him. Investigate the facts (people,places andallegedoccurrences). Investigatetheallegedscene. Analyzethescene against the facts. Investigate people to find out about their backgrounds and their reputations. Investigate theirexperienceandtheir educational background. Be prepared to challenge thetestimonyin light of the “big picture.”

Once you have a good working knowledge of the facts, try to anticipate the testimony of every witnesspriortotrial. Prepareforeachwitness. Considerwhateachwitnessoffersthatcanadvance your client’s story. And prepare to blunt the effect of adverse testimony you anticipate will be offered against your client. Do not be afraid of avoiding cross examining a witness.

Consider writing out every question in advance. But do not be married to your questions because the testimony might vary from what you anticipate it will be. With experience, one can become more flexible and use an outline or use a list of subjects about which to cross examine. Formulate some questions from known sources of information that you can readily access (police reports, prior testimony, medical records, prior statements, etc.). Formulate some questions that fit the theory of your case.

B. Conducting the Examination. One of the keys to effective cross-examination is to listen. Listen to the answers to questions asked on direct examination and take good notes. Listen for inconsistencies in the evidence as you know it. Listen for illogical answers and answers that are inconsistent with the state’s theme and state’s witnesses. Listen for inconsistencies with common experiences.

Testify. Use cross examination to tell the jury your client’s story. This is one of the few times the advocate has to opportunity to challenge the assertions of the witness and to advance the client’s position. Take advantage of the opportunity to talk with the jury. Do not just repeat direct examination, unless you do so to discredit it.

Cross Examination By: Eric J. Davis, Assistant Public Defender Harris County Public Defender’s Office eric.davis@pdo.hctx.netPrimarily use leading questions, but do not be afraid to ask non leading questions when appropriate. Use tools of impeachment prior statements, prior recorded statements, etc. Use extrinsic evidence or testimony of other witnesses who can contradict the first witness’ untruthful statement. Orusecross examinationto showbiasor motive to demonstrate to the jurythe witness’ reasonforlying. Ifthewitnesshasnotbeenconsistentinhisorherstatements,impeachthewitness with prior inconsistent statements video, audio, pre trial witness interviews, or with statements made to other people. Remember to start and end on a strong note. C. Types of CrossExaminations:

The Soft Cross examination is a type of cross examination where in the lawyer modifies the style and/or the content of the cross examination to appropriate the emotions of the case. Instead of being “in your face and aggressive,” the lawyer is aware of the effect of the mode of questioning on the jury. For example, a jury might become upset at a lawyer who aggressively questions a young child. So a lawyer might speak to a child witness gently, as if he were speaking to a child. Additionally, some jurors might see some fact witnesses (like nurses or medical personnel) as simply doing their jobs. They might react adversely to a lawyer who attacked a witness they perceived as merely doing their job. During the soft cross, the lawyer modifies the style of the cross examination to take into account how a jury might react to the lawyer (seeking to avoid a negative reaction).

The soft cross examination also involves a modification of the content of the crossexamination. Instead of attacking the witness head on, the lawyer seeks to peel back emotional layers to reveal bias or other elements. For example, in attacking a snitch/cooperating witness a lawyer engaged in a soft cross might focus on the collateral emotional losses that the witness is facing instead of focusing merely on the punishment the witness faces. A typical cross of a snitch might look like this:

Lawyer: Mam, you have agreed to testify against my client in this case, right?

Snitch: Yes.

Lawyer: You are charged in a conspiracy case, true?

Snitch: Yes.

By: Eric J. Davis, Assistant Public Defender Harris County Public Defender’s Office eric.davis@pdo.hctx.netLawyer: You are facing twenty years in the pen, true?

Snitch: Yes.

Lawyer: You are saying whatever you can to avoid doing that time, true?

Snitch: I am telling the truth.

Lawyer: But a different truth wouldn’t get your time off, would it?

The content of the Soft cross might look like:

Lawyer: Mam, you are a mother of three, true?

Snitch: True.

Lawyer: You are in jail now?

Snitch: Yes.

Lawyer: You aren’t able to see your kids while you are lock up, are you?

Snitch: No.

Lawyer: You can’t take them to school?

Snitch: No.

Lawyer: You can’t talk to their teachers to find out what’s going on with them can you?

Snitch: No.

Lawyer: You aren’t at home to greet them when they come home from school, are you?

Snitch: No.

Lawyer: The longer you are incarcerated, the less you will be able to do this are you?

Snitch: Yes.

The soft cross attempts to pull back emotional layers to develop bias, interest or motive. Many lawyers who use this method also employ psychodrama to further develop their cross

examinations. They urge that psychodrama gives them insight into the emotional layers of the witness by helping them “get into the skin of the witness.”

The Story Telling Cross examination is another form of cross-examination. A story-telling cross merely tries to tell the story of the witness, of the case, of a theory or of an object through cross examination. With the story telling cross an advocate is trying to communicate with and persuade jurors. During the story telling cross, the advocate is trying to have a conversation with her neighbor over the fence as she is working in her yard. Or the advocate takes the approach that she is having a conversation in the lobby after church. Speak in plain English. (Talk as if you are talkingwith everydaypeople,otherwiseknownas potentialjurors.)Put awaylawyerlanguagelike “calling your attention to the date on which the occurrence in question took place” and references to “exiting vehicles.” Real people get out of cars, they do not exit vehicles. So instead of calling the witness’s attention to the date in question in which the occurrence took place, instead simply state “Let’s talk about what you did on April 4, 1968, before you left the Lorraine Hotel after Dr. King was shot.”

Try to use short declarative statements during the story telling cross examination. While much of the traditional cross examination requires control of the witness, it is not necessaryto use the “prefixes” and “suffixes” of the leading question format the prefixes “Is it a fact that . . . ?” “Isn’tit true that.. . ?”orthesuffixes “... ,correct?”or“...,isn’t that true?”or “...,am Icorrect?” You can use these leading question techniques, but you can obtain the information without using them. And they have a tendency to break up the story. For example, “You are James Earl Ray.” You do not need to say “Isn’t it a fact that you are James Earl Ray?” or “You’re James Earl Ray, correct?” Just state the fact and have the witness affirm it or deny it. Generally, during the story telling cross most of the answers to questions should be “Yes.” That is because you are using the cross examination to tell your story and enhance your credibility. It is also a fast, efficient way to provide the jury with information. It also allows the cross examiner to tell a storyandtostatethefacts. Theonlyrolethewitnessplaysistoaffirmthetriallawyer’sstatements.

Cross Examination By: Eric J. Davis, Assistant Public Defender Harris County Public Defender’s Office eric.davis@pdo.hctx.netA good way to employ the story telling cross examination is to first write the story you want to tell through the witness as a narrative. Simply write out a paragraph (using short, declarative sentences) telling the story you want to tell. For example,

Martin Luther King, Jr., was a prominent American leader of the African American civil rights movement. Dr. King won the Nobel Peace Prize. He was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968. He was 39 years old when he was assassinated. On June 10, 1968, James Earl Ray was arrested in London at Heathrow Airport. Ray was a fugitive from the Missouri State Penitentiary. He was later extradited to the United States, and charged with the crime. On March 10, 1969, Ray entered a plea of guilty. He was sentenced to 99 years in the Tennessee state penitentiary. Ray later made many attempts to withdraw his guilty plea. He was unsuccessful. He died in prison on April 23, 1998.

The question and answer might look like this,

Q. Martin Luther King, Jr., was a famous?

A. Yes.

Q. He was a leader of the civil rights movement in the 60s?

A. Yes.

Q. The Civil Rights Movement was a National Movement? A. Yes.

Q. It ended Jim Crow? A. Yes.

Q. It ended the forced separation of people by race in our nation? A. Yes.

Q. Dr. King won the Nobel Peace Prize?

A. Yes.

Q. The Nobel peace prize was an international award?

By: Eric J. Davis, Assistant Public Defender Harris County Public Defender’s Office eric.davis@pdo.hctx.netA. Yes.

Q. He was one of the youngest winners of the prize ever?

A. Yes.

Q. He was assassinated? A. Yes.

Q. He was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee?

A. Yes.

Q. He was killed on April 4, 1968?

A. Yes.

Q. He was only 39 years old when he died?

A. Yes.

Q. On June 10, 1968, James Earl Ray was arrested in London at Heathrow Airport? A. Yes.

Q. Ray was a fugitive from the Missouri State Penitentiary?

A. Yes.

By: Eric J. Davis, Assistant Public Defender Harris County Public Defender’s Office eric.davis@pdo.hctx.netQ. He was later extradited to the United States?

A. Yes.

Q. He was charged with killing Dr. King. A. Yes.

Q. On March 10, 1969, Ray pled guilty to killing King. A. Yes.

Q. He was sentenced to 99 years in the Tennessee state penitentiary.

A. Yes.

The Traditional Cross examination generally serves two primary purposes and they manifest themselves in either a Destructive Cross or a Supportive Cross. The goal of a destructive cross is to discredit the testifying witness or another witness. This type of cross is designed to reduce the credibility of the witness or the persuasive value of the opposition’s evidence. The use of impeachment material is a key to destructive cross, as it is the ability to attack and discredit the bases for the witnesses’ statements or opinions. The questioner’s goal is to establish control of the witness. The goal of the supportive cross is to bolster the questioner’s own theory of the case and tell the defense story. It should develop favorable aspects of the case not developed on direct examination or expand on these aspects. This testimony may support your witnesses or help to impeach other witnesses.

Control is the keyto the traditional cross examination. The lawyer never asks a question to which he does not know the answer (or what the answer will be). The lawyer always asks leading questions with a suffix or prefix. The lawyer never relinquishes control.

Raising prior inconsistent statements is the most frequently used impeachment method at trial. More than any other impeachment method, however, impeaching with prior inconsistent statementsrequiresaprecisetechniquetobeeffectivebeforeajury. Ruleofevidence613,requires

By: Eric J. Davis, Assistant Public Defender Harris County Public Defender’s Office eric.davis@pdo.hctx.netthat the witness have an opportunity to admit, deny or explain making the inconsistent statement. Prior inconsistent statements can be either collateral or non-collateral. If it is non-collateral, and the witness does not admit making it, you must prove it up with extrinsic evidence.

The basic structure of the impeachment technique involves three steps: recommit, build up, and contrast. First, recommit the witness to the fact he asserted on direct, the one you plan to impeach. Tryto do this in a waythat does not arouse the witness’ suspicions. Use thewitness’ actual answer on direct when you recommit him because he is most likely to agree with his own statements. (You could also challenge the witness to admit the facts he stated in a prior inconsistent statement and get a denial of them).

Second, build up the importance of the impeaching statement. Direct the witness to the date, time, place and circumstances of the prior inconsistent statement, whether oral or written. Show that the statement was made when the witnesses recollection was fresher or under circumstances that the witness would be likely to tell the truth (under oath, closer in time to an event, made to assist in an investigation, etc.).

Third, read the prior inconsistent statement to the witness and ask him to admit having made that. Use the actual words of the impeaching statement. And project your attitude to signal to the jury what its attitude should be during the impeachment. If your attitude is that the witness was lying, confused, or forgetful; then broadcast it with your tone, facial expressions, cadence, demeanor, etc.1

Besides prior inconsistent statements witness can be impeached many different ways on cross examination. Witness can be impeached by showing bias, interest and motive; through the use of priorconvictions; throughtheuseofpriorbadacts; throughotherwitnesses; throughcontradictory facts; through reputation and opinion testimony.

Consider this blog post by Bobby G. Frederick from the internet blog Trial Theory 2

1 See Thomas A. Mauet, Fundamentals of Trial Techniques, p. 242 43. 2 http://trialtheory.com

Cross Examination By: Eric J. Davis, Assistant Public Defender Harris County Public Defender’s Office eric.davis@pdo.hctx.netJuly 22, 2011

“Nobodybelieves aliar…even when heis telling thetruth!” Myson is four years old now, soon to be five. He’s gotten into the habit of coming in while I’m working on the computer and telling me “daddy, dinner’s ready!” After a few times of walking into the kitchen to see dinner still cooking on the stove, I’m thinking I need someindependent confirmation before Ibelievethat dinneris ready. I ask him, “are you telling the truth?” and of course he responds “yes!”

Last night I was reading The Boy Who Cried Wolf to him before bed, and it occurred to me that this story contains a most basic explanation of how to demonstrate the un truthfulness of a witness’ testimony. Notthatthisis alwaysthe goal of cross examination,but when a witness is not being truthful about something critical to the case it becomes an important part of the cross examination.

How do you prove that a witness is lying? In some cases it can be proven by extrinsic evidence or testimony of other witnesses who can contradict the first witness’ untruthful statement. Or we can show bias or motive demonstrate to the jury the witness’ reason for lying. If the witness has not been consistent in his or her statements we can impeach the witness with prior inconsistent statements video,audio, witnessinterviewspre trial, orstatements they have made to other people.

But if these tools are not available, or in addition to these tools, can we show that the witness is simply someone who lies even if we are unable to prove the witness is lying about the most important fact, what if we are able to show that the witness is lying about other facts? If the witness has lied about other facts, has given inconsistent statements on other subjects, and can be impeached on other statements that he has made to the jury, why should the jury believe anything that the witness says?

The Old Man’s advice to the young shepherd boy, as he laments the loss of his sheep to the wolf, and wonders why the village folk did not come to help him, is as valuable a lesson for cross examination as it is for myson: “Nobodybelieves a liar…even when he is telling the truth!” If you are not a consistently honest person, how can we know that you are telling the truth?

Cross Examination By: Eric J. Davis, Assistant Public Defender Harris County Public Defender’s Office eric.davis@pdo.hctx.net

December 1 2, 2022 Magnolia Dallas Dallas, Texas

Chief Attorney, Collin County Mental Health Managed Counsel 2100 Bloomdale Rd., Ste. 20209 McKinney, TX 75071 214.491.4805 phone 214.491.4825 fax aferguson@co.collin.tx.us email

6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association

Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association

Capital cases and other serious crimes commonly involve a client with mental health issues. Many issues may be encountered in development of the mental health background of your client. Prisons are the new asylums as state hospitals are overflowing and there are no beds for those suffering a mental crisis. According to the Urban Institute “An estimated 56 percent of state prisoners, 45 percent of federal prisoners, and 64 percent of jail inmates have a mental health problem.” i

Studies have shown and we as defense lawyers know it to be true that “In the criminal justice system sexually based offenses are considered especially heinous” ( CBS SVU series.)

Coverage of sex crimes commonly utilizes “highly sensational wording and content” to evoke fear and anger in the public and harsher sentences for the sex offender population Ducat, L., Thomas, S., and Blood, W., 2009.) Lifetime registration and stricter laws follow sex offenders their entire lives and there is very little differentiation in punishment regardless of the offense. One study by Mears, Mancini, Gertz, and Bratton (2008) found overwhelming support for sex offender registries (92%) and residency restrictions (76%) with 46% agreeing that incarceration is the best response even in non contact crimes like indecent exposure. Prosecutors offer opening and closing statements about the monsters under the bed and the community is encouraged to fear every person charged with a sex crime.

A stigma already surrounds the offense and now it is coupled with mental illness of the offender which possesses its own stigma. Prosecutors leverage the stigma of mental illness by presenting the defendant as dangerous due to hallucinations and other symptoms of psychosis, as well as the defendant’s failure to take medication, and the lack of approprate resources in the community.

Persons suffering from mental illness such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder commonly exhibit anosognosia, a condition in which a person with a disability is cognitively unaware of having the condition due to an underlying physical condition. This contributes to the defendant’s refusal to take medication, since they do not believe they have the illness and

therefore do not believe there is a need for medication. A shortage of mental health beds, shortage of psychiatrists, laws that fail to provide alternatives and appropriate care, as well as inadequate treatment for mental health concerns are all highlighted by the prosecution to explain why treatment can neither be successful in the community nor provide for the safety of the community. Mass shootings and other such events generally highlight the shortcomings of our mental health system and escalate the public’s fear of those who suffer from these debilitating illnesses. Despite the fact that vast research on the relationship between mental illness and violence have shown the majority of individuals with mental illness are not violent. Most violent acts ar not committed by persons with mental illness (Glied, S., & Frank, R.G. (2014.)

There is a high prevalence of mental illness in the sex offender population, which further compunds a lawyer’s need for effective mitigation efforts in these cases. Mental illness may be up to seven times more likely in sex cases than in the general population (Chen, Chen & Hung, 2016.) Research in the correlation of sex crimes and mental illness is sparse. Only one direct study was identified. However, research has suggested that serious mental illness such as psychotic disorders often mitigate culpability in public opinion (Barnett, Brodsky and Price, 2007), yet this may not extend to the sex offender population (Rogers and Ferguson, 2010). Sex offenders exhibit a wide range of mental illness symtoms. There is a general perception that offenders suffering psychosis are especially dangerous and evidence of mental illness may be construed as particulary aggravating (Berkman 1989.) 70% of Respondents in one study belived that those with schizophrenia or alcohol/drug problems were dangerous and 80 % believed they were unpredictable.

Mental illness may negatively influence a defendant’s behavior, contributing to the crime committed (Roseman v. Dep’t of Treasury, 1997.) Berkman (1989) explored mental illness as an aggravating factor pointing to one case in which the mental illness directly contributed to a death penalty sentence. The jury believed the mental illness rendered the defendant unredeamably dangerous. Conversly Barnett, Brodsky, and Davis (2004) researched ten particular mitigating factors such as sexual abuse as a child, being under the infuence of drugs or alcohol, hospitalization for mental illness, head injury, and church attendance. Their

study found schizophrenia and psychiatric hospitalization were two of the top mitigating factors. Thus it suggests at least serious mental illness can be a recognized mitigating factor.

Research is limited as it relates to the idea of mental illness mitigation in sex offenses, but one thing is true; both mental illness and sex offenses carry a stigma that make mitigation difficult. Much like the mitigation in a sex crime case sans the mental health issue the jury’s concern in a mental health case is safety, safety of children and safety of the community. Cases involving a serious offense and a serious mental illness, which I have observed through the last twelve years, have hinged on the jury’s fear. Fear, which the prosecutor uses to drive home the necessity for incarceration. Yes this was a one time incident, yes the client was off his medication, yes there is no prior history, but…..we just can’t be sure he will take his medication. We just can’t be sure the system won’t fail again and what if …

The truth is that our mental health system is failing. In Texas we have nine state mental hospitals. These hospitals have 2385 beds. While there are also private psychiatric hospitals as well, the numbers are still critically low. Texas Health and Safety Code requires a serious risk of harm to meet the involuntary hospitalization requirement. Thus a person may be deteriorating for an extended time before hospitalization is required, if ever. Hospitalization then only continues for so long as the person continues to meet the criteria. Very often this is 1 5 days. While the person may be stabilized and released, the short period of time does not ensure the medication regimen is back on track and the person will voluntarily continue a postive course of treatment. These factors make it incredibly difficult to develop a plan to ease the jury’s fears, but a plan for ongoing mental health care is a critical component of the mitigation.

Attorneys often hire an expert such as a psychologist or psychitatrist or other forensic expert and leave development of the mental health evidence to the expert. Attorneys will request full psychologicals or a neuropsych evaluation with no real understanding of what these exams include or whether the exam will produce the information needed. Further this is often done very early in a case, before all discovery and evidence has been reviewed.

Counsel should consider the benefit of narrowing the scope of the evaluation, gathering records prior to requesting a particular evaluation, and then determining which type of expert

may be most appropriate. Valenca, et al. found the systematic psychiatric evaluation of persons who commit sexual offenses contributes to the the intervention strategy, prevention and evaluation of the specific motivations, related to the manifestation of violent sexual behavior as well as allows characterization of groups or situations of risk. Schizophrenia, bipolar and Intellectual Developmental Disorder are the mental disorders and developmental disorders most frequently related to the perpetration of sexual offense.

A thorough review of the bio/psycho/social history will assist counsel in determining the type of expert needed, what type of testing is needed and develop the working theory of the case. However a client actively in need of psychiatric treatment, one who is floridly psychotic, or one who may not be competent necessitate action very early on and likely prior to the bio/psycho/social history completion.

The bio/psycho/social history investigation may indicate other types of experts are necessary such as:

1) Medical Expert: Many medical conditions can cause psychiatric symptoms thus it may also be important to consult with a medical doctor to rule out a medical disorder.

2) Mental Health Consultant: A mental health consultant can assist the attorney in understanding mental health conditions and symptoms, as well as to understand data and assist in theory development.

Attorneys wil need to become familiar with the signs and symptoms of the client’s particular mental illness. In these cases a mitigation specialist may be more beneficial than a law enforcement investigator.

Texas Appleseed offers a great deal of informaton on representing clients with mental illness in the handbook, Mental Illness, Your Client and the Criminal Law: a Handbook for Attorneys Who Represent Persons With Mental Illness, “ Good mental health experts can provide testimony at the punishment phase to helpt the jury understand hwo your client is, how he or she experiences the world, and why your client behaves as he or she does. You must show the relationship between the illness and the disability. Specific Mitigation Strategies are

A Mitigation Expert will be able to:

• Conduct a through bio psycho social history investigation;

• Interview your client;

• Gather medical records; and

• Determine what cultural, environmental, and genetic circumstancesmight have factored into your client’s case.

The Mitigation Expert will look to your clients history for:

• Mental disorders;

• Cognitive disabilities;

• Neurological impairments;

• Physical sexual or psychological development issues;

• Substance abuse issues;and

• Other influences on the development of client’s personality and behavior

Experts you may need For testimony:

• Psychiatrist with forensic specialization: Diagnosis, treatment, and medication for mental disorders and medical issues;

• Psychologist as testifying expert: testimony related to personality or behavioral disorder, intellectual or cognitive functioning, or administering and interpreting tests;

• Neuropsychiatrist or neuropsychologist:for brain injuries or problems with memory, language, or orientation functions.

Work with your experts to ensure inquiry into the client’s mental health history. The expert should interview outside sources and request records identified in your review. The comprehensive exam includes:

• Appropriate brain scans

• Neuropsychological testing

• Diagnostic testing

• Physical examination

• Neurological examination

• Psychiatric and mental status examination

Mitigation begins in jury selection to identify juror feelings related to mental illness. The incidence of mental illness are prevalent enough that a number of jurors in the jury pool are likely to have a close family member with a mental health diagnosis. Their feelings and understanding may range from empathy and understanding to fear and anger. This is an opportunity to educate jurors on symptoms and behaviors as well. An accused has the right to question jurors about their attitudes about a potential insanity or lack of capacity defense, including questions about psychiatry books read, contacts with psychiatrists, members of their family receiving treatment and inquire about their feeligs on insanity. U.S. v Robinson 475 F2d 376 (D.C. Cir. 1973, U.S. Jackson, 542F.2d 403 (7th Cir. 1976). A veniremember is challengeable for cause for having a bias or prejudice in favor or against a defendant under Tex. Code of Crim. Proc. Ann. Art 35.16(a)(8). The venire members potential bias or prejudice towared a defendant that suffers from mental illness can be investigated by the defense.

During the guilt/innocence phase of trial other witnesses may be used to open the discussion on mental health issues that will be addressed in mitigation. One example is Police officer witness. They are required to have mental health training in at least a 40 hour course on Crisis Intervention. Course outlines are available online at the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement Standards Website. Addtionally, law enforcement departments have policy’s and procedures on the officers interactions with the mentally ill, which offer further opportunities to address mental health mitigating factors.

Mitigating mental health concerns will be an additional challenge to a a complex and uphill defense. You must be sure to have obtained all available records and evaluations, so that you can make the most informed choices as to the theory, defenses, and mitigation evidence.

The main consideration will be deomonstrating that providing mental health treatment will provide for community safety.

Texasappleseed.org (2015), https://www.texasappleseed.org/sites/default/files/Mental_Health_Handbook_Printed2015.pdf (last visited Aug 20, 2021).

Barnett, Michelle E., Brodsky, Stanley L. & Davis, Cali Manning, When mitigation evidence makes a difference: effects of psychological mitigating evidence on sentencing decisions in capital trials, 22 Behavioral Sciences & the Law 751 770 (2004).

Chen, Yung Y., Chen, Chiao Yun & Hung, Daisy L., Assessment of psychiatric disorders among sex offenders: Prevalence and associations with criminal history, 26 Criminal Behavior and Mental Health 30 37 (2014).

Ducat, Lauren, Thomas, Stuart & Blood,Warwick, Sensationalizing sex offenders and sexual recidivism: Impact of the Serious Sex Offender Monitoring Act 2005 on media reportage, 44 Australian Psychologist 156 165 (2009).

Glied, S., & Frank, R.G. (2014). Mental illness and violence: Lessons from the evidence. American Journal of Public Health , 104(2), e5 e6.

Mears, Daniel P. et al., Sex Crimes, Children, and Pornography, 54 Crime & Delinquency 532 559 (2007).

Valenca, Martins, Nascimento, Isabella & Nardi, Antonio, Relationship between sexual offences and mental and developmental disorders: a review, 40 Archives of Clinical Psychiatry (São Paulo) 97 104 (2013).

Rogers, Darrin L & Ferguson, Christopher J., Punishment and Rehabilitation Attitudes toward Sex Offenders Versus Nonsexual Offenders, 20 Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 395-414 (2011).

Tex. Code of Crim. Proc. Ann. Art 35.16(a)(8).

U.S. v Robinson 475 F2d 376 (D.C. Cir. 1973).

U.S. Jackson, 542F.2d 403 (7th Cir. 1976).

Speaker:

December 1 2, 2022 Magnolia Dallas Dallas, Texas

Minton, Bassett, Flores, Carsey, P.C. 1100 Guadalupe St. Austin, TX 78701 512.476.4873 phone 512.479.8315 fax sbassett@mbfc.com email www.website.com website

Co Author: Betty Blackwell

Board Certified in Criminal Law 1306 Nueces St Austin, TX 78701 512.479.0149 phone bettyblackwell@bettyblackwell.com email www.website.com website

6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

BETTY BLACKWELL

Attorney at Law Board Certified in Criminal Law 1306 Nueces Street Austin, Texas 78701 512-479-0149 bettyblackwell@bettyblackwell.com

Minton, Bassett, Flores, Carsey, P.C. 1100 Guadalupe St. Austin, Texas 78701 512-476-4873 sbassett@mbfc.com

The Basics. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . 3

Use a written contract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4

Neglect . . . . . . . . 5

Malpractice and ineffective assistance of counsel . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . 6

Failure to Communicate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Who can File a grievance?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Fee Disputes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Non-refundable retainers. . . . . . . . . . . 10

Trust Account Violations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Duty on Termination . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Perjury . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Perjury by Defendant . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Advising Subpoenaed and Potential Witnesses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16

Conflict of Interest . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Compulsory Discipline upon Conviction . . . . . . . . . 17

Rule changes as of 2021 . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Grievance System . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

Investigaion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Investigatory Panels. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22

Just Cause . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22

Grievance Committee .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .24

District Court . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Grievance Referral Program . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Important State Bar Phone numbers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . 25

Butterfield v. State, 992 S.W.2d 448 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999). . . . . . . . . . 16

Cluck v. Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 214 S.W.3d 736 (Tex. App. Austin 2007) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11

Ex Parte Wilson, 724 S.W.2d 72 (Tex. Crim. App. 1987) . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

Helton v. State, 670 S.W2d 644 (Tex. Crim. App. 1984) . . . . 15

Hines v. Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 2003 WL 21710589 (Tex. App. Hous 14th ) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

In re McCann, 422 S.W.3d 701 (Tex. Crim. App. 2013). . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

In re Lock, 54 S.W.3d 305 (Tex. S.Ct. 2001) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . 19

Lafler v. Cooper, 132 S.Ct. 1376 (2012). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

Missouri v. Frye, 132 S.Ct. 1399 (2012) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

Nix v. Whiteside, 106 S.Ct. 988 (1986) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . .15

Padilla v.Kentucky, 130 S.Ct. 1473, (2010. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Santos v, Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 140 S.W.3d 397 (Tex. App. Hous 2004) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

Strickland v. Washington, 462 U.S. 1105 (1984) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Walter v. Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 2005 WL 1039970 (Tex. App. Dallas) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Weiss v. CFLD. 981 S.W.2d 8 (Tex. App. San Antonio 1998) . . . . . . . . .12

Wiggins v. Smith 539 U.S. 510, 123 Sct. 527 (2003) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

Willie v. CFLD, 2014WL586226, (Tex. App.-Houston 1st Dist. 2014). . . . .11

All lawyers licensed in Texas are required to abide by the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct. A violation of any of the disciplinary rules can result in a lawyer being sanctioned by the State Bar of Texas’s office of the chief disciplinary counsel. Sanctions can range from private reprimands up to disbarment.

Last year (through May 2020) the State Bar of Texas received 7505 complaints about lawyer misconduct. 5123 were dismissed because the complaint does not describe or allege a violation of the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct. 2202 were sustained complaints which proceeded as a grievance against the attorney. After an investigation,1705 cases were submitted to the summary disposition grievance panel for a dismissal. The following is a discussion of the most common complaints that result in a sanction by the State Bar of Texas and how to avoid them.

The Basics:

Have a written contract

Return phones calls if only to say that there is nothing new to report

Communicate with clients in writing to document

Return files upon termination of employment

Keep the attorney’s address current with the State Bar at all times

Return unearned fees

Do not advise anyone to avoid a subpoena or advise them to ignore a subpoena

Have a trust account for all fees that are prepaid or advance fees paid for services in the future

Answer any State Bar grievance

Do not have sex with your clients

(c)when the lawyer has not regularly represented the client, the basis or rate of the fee shall be communicated to the client, preferably in writing, before or within a reasonable time after commencing the representation.

A written contract will spell out exactly what work the lawyer has agreed to undertake and at what fee. Many complaints to the State Bar arise between the lawyer and the client about exactly what the lawyer had agreed to do. Rule 1.02(b) states that a lawyer may limit the scope, objectives and general methods of the representation if the client consents after consultation. However, without a written contract it is a swearing match as to what was said and the grievance can go forward if the State Bar disciplinary counsel has just cause to believe that a rule violation has occurred. Since it is a civil case, the burden to prove the allegations is by a preponderance of the evidence.

Limiting the extent of the representation is one of the most useful aspects of a written contract. Most clients believe that the fee for representation includes the appeal of an adverse decision. However, most lawyers do not intend to include the appeal in the original fee structure.

Explaining whether expert witnesses and other costs of the litigation are the client’s responsibility to pay for or the lawyer’s, is another area of common confusion. In criminal law, explaining that the expunction process is a separate civil proceeding that will not occur without additional fees being paid, is almost always an area of frustration on the part of the client.

Recently malpractice carriers have asked that attorneys include in their written contract exactly the length of time the lawyer will retain the client’s file and that the file will be destroyed unless the client takes possession of the file. Rule 1.14(a) requires that trust account records be kept for five years, so it is recommended that the time period of retaining a file be at least five years. A grievance must be filed within four years so that keeping the file at least five years will insure the records are available to defend any grievance.

Rule 1.04 (d) requires that a contingent fee agreement be in writing and that it must state the method by which the fee is to be determined. It also requires an accounting at the end of the case.

Neglect has been traditionally the number one most common complaint filed by former clients against their attorneys and it is the most likely rule violation to result in an attorney being sanctioned by the State Bar.

A Lawyer shall not neglect a legal matter entrusted to him or frequently fail to carry out completely the obligations that the lawyer owes the client.

Santos v, Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 140 S.W.3d 397 (Tex. App. Hous 2004). The lawyer was sanction for the conscious disregard of a legal matter. He had been paid for an immigration matter and though told of the court date, the lawyer failed to appear. In contrast to the result in Santos, a simple calendaring mistake usually will not cause a lawyer to be sanctioned by the Bar as the comments to Rule 1.01 say “A lawyer who acts in good faith is not subject to discipline, under this provision for isolated inadvertent or unskilled act or omission, tactical error, or error of judgment”

Malpractice is not always a violation of the Rule of Ethics and ineffective assistant is not necessarily a violation of the Rule of Ethics. An example of malpractice maybe telling a defendant that deferred adjudication will not show up on their record. But this probably doesn’t rise to the level of neglect, only incompetence. Malpractice can occur when a lawyer gives bad legal advice. However, that does not meet the definition of neglect to cause the lawyer to be sanctioned by the State Bar.

The duty to investigate, is part of the effectiveness standard. A lawyer must make a reasonable effort to investigate the case or after discussions with the client, make a reasonable determination that investigation is not necessary. Strickland v. Washington, 462 U.S. 1105 (1984). Wiggins v. Smith 539 U.S. 510, 123 Sct. 527 (2003). Failure to investigate a case may not rise to the level of neglecting a case in violation of the Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct.

Failure to convey the plea offer to the defendant can be neglect and cause a writ to be field. Failure to advise the client of the consequences of a plea offer is ineffective assistance and may also rise to the level of neglect or failure to properly communication with a client as discussed in the next section, under the rules of Professional Conduct.

For example some of the most common criminal cases: Any plea to a DWI case can result in substantial non criminal consequences for the person convicted. There are many areas of employment that prohibit a conviction for DWI, including Police Officers, Firefighters, and emergency medical technicians. Many employers have there own employment guidelines which can include dismissal for a DWI. School district often fire teachers if they are convicted of DWI. Canada will not allow anyone to enter the country if they have a DWI conviction.

In POM cases, a jail sentence results in a driver’s license suspension of up

to 180 days. A jail sentence is a final conviction and can not be expunged nor can it be sealed if it occurred before September 1, 2015. Drugs cases are eligible for deferred adjudication, which can be eventually sealed, but not expunged. A regular probation stays on the person record for the rest of their life. Many employers will not hire someone with a drug conviction. Many scholarships to colleges prevent people from applying who have drug convictions. Drug convictions can result in severe immigration consequences as do violation of gun laws. Many apartment complexes will not rent to individuals who have drug convictions on their record.

These are just a few of the collateral consequences and many clients will file grievances upon their lawyer if they feel that the lawyer failed to properly advise them of the consequence of their plea.

The most common allegation of neglect in a civil case, is the failure to file a lawsuit within the statute of limitations. Though clearly this is malpractice and the lawyer can be sued, the defense to the grievance is that it was an isolated inadvertent act or omission or a calendaring mistake. But the comments to Rule 1.01 caution that delays can cause the client anxiety and the lawyer has a duty to communicate reasonbly with the client, suggesting that a grievance might be upheld for failure to communicate.

Malpractice refers to negligence or misconduct that fails to meet a standard of care that is recognized in the profession and that results in harm to the client. In Texas it is very hard to sue a criminal defense lawyer for malpractice. The Supreme Court of Texas has decided that only innocent clients have a viable malpractice cause of action against their criminal defense attorney.

Strickland v. Washington, 104 S.Ct. 2052 (1984) set out a two part test. First the counsel’s representation must be deficient and secondly, that deficient performance must have prejudiced the defendant. The bench mark for judging any claim of ineffective assistance of counsel must be whether counsel’s conduct so undermined the proper functioning of the adversarial process that the trial cannot be relied on as having produced a just result. Under the 6th amendment, the defendant must show a reasonable probability that but for the counsel’s errors, the outcome would have been different.

Three important Supreme Court cases have reviewed the performance of criminal defense counsel to determine whether the client should be afforded a new trial. 1. Padilla v.Kentucky, 130 S.Ct. 1473, (2010) held that it was ineffective assistance of counsel to fail to advise a defendant that his plea of

guilty to a drug distribution charge would make him subject to automatic deportation. However, Padilla is not retroactive to cases already final. 2. Failure to inform the defendant of a plea offer is ineffective assistance of counsel. Missouri v. Frye, 132 S.Ct. 1399 (2012) 3. In Lafler v. Cooper, 132 S.Ct. 1376 (2012), the defendant was prejudiced by counsel’s advise to reject the plea offer and proceed to trial. The trial counsel’s opinion that the evidence was legally insufficient to convict the defendant, was not sound advice. The defendant was entitled to effective assistance of counsel during the plea negotiations.

When deciding to accept a case, a lawyer should be aware of Rule 1.01(a) which states that a lawyer shall not accept or continue employment in a legal matter which the lawyer knows or should know is beyond the lawyer’s competence. The only exceptions are if the attorney associates another competent attorney on the matter with client consent, or it is an emergency situation. If in doubt, don’t take the case.

Immigration issues have been a focus of the Chief Disciplinary Counsel’s office. In their annual report for 2020, they stated that they received 19 immigration complaints, imposed 11 sanctions and referred 5 to the Grievance Referral Program.

Failure to communicate.

This is the second most common grievance filed and it is usually filed in addition to the allegation of neglect.

A lawyer shall keep a client reasonably informed about the status of a matter and promptly comply with reasonable requests for information. Rule 1.03 (b) states that a lawyer shall explain a matter to the extent reasonably necessary to permit the client to make an informed decision.

In reference to a criminal case the Rules require a lawyer shall promptly inform the client of the substance of any proffered plea bargain. Failure to do so has been held to be ineffective assistance of counsel. Ex Parte Wilson, 724 S.W.2d 72 (Tex. Crim. App. 1987). Failure to communicate a settlement offer in a civil case would be the same misconduct. Under the Rules, the lawyer is allowed to withhold information if believes the clients would react imprudently or if the client is under a disability.

Failure to communicate is alleged in close to half of all grievances filed. The duty is an affirmative obligation and it not dependent on a client’s request for information. Failing to advise a client of an adverse development in a case would be a violation. A lawyer must respond to reasonable requests for

information.

Failure to provide adequate information for the defendant to make a decision about whether to have a jury trial or whether to accept a plea offer or a settlement offer can result in an attorney being sanctioned by the State Bar.

Lawyers must be aware of immigration consequences, employment consequences, and licensing consequences, as discussed under the section on Neglect.

Lawyers are not required by the rules to communicate with family members or loved ones. However, one of the biggest misunderstandings by attorneys is who can file a grievance upon them. Many lawyers will answer a grievance filed by a family member saying that they have no attorney client relationship and therefore are not required to answer this grievance. This is wrong.

Complaints with the State Bar may be filed by anyone. The complaint does not have to be filed by the client. There does not have to be an attorney client relationship for the person to file a complaint with the State Bar. Hines v. Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 2003 WL 21710589 (Tex. App. Hous 14th ) The Father of the client filed the complaint and the respondent attorney’s theory was that there could be no sanction because he represented the son. The Court made it clear that anyone can bring to the attention of the bar a rule violation. In addition, any alleged misconduct does not have to be in the course of an attorney client relationship for the State Bar to prosecute a violation under Rule 804(a)(3) which states that a lawyer shall not engage in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation. Walter v. Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 2005 WL 1039970 (Tex. App. Dallas). For example, a lawyer can be disciplined for actions taken as the executor of an estate, even though the lawyer may have no attorney client relationship with the beneficiaries of the will. Rule 803 (a) requires a lawyer having knowledge that another lawyer has committed professional misconduct that raises a substantial question as to that lawyers honesty, trustworthiness or fitness as a lawyer, to inform the Chief Disciplinary Counsel’s office (CDC). The only exception is for mental illness or chemical impairment in which the lawyer can report the conduct to the Lawyer Assistant Program or the information is protected by confidentiality under Rule 1.05 or is obtained through counseling programs. Rule 1.05, Confidential Information, includes both privileged information and unprivileged client information which a lawyer shall not reveal except if provided by the rules.

Texas Lawyers Assistance Program’s phone number is 1 800 204 2222 ext. 1460. Conversations are confidential and referrals are available for help

with mental illness, substance abuse or impairment by physical illness. The goal is to rehabilitate lawyers and help them resume practicing law.

Fee disputes constitute a large number of complaints. Those complaints are first referred to the client attorney assistant program (CAAP) and to the local fee dispute committees of local bar associations. CAAP’s stated purpose is to try and work out a settlement so that the case does not proceed to a grievance. Their number is 1 800 204 2222 ext. 1777. If a reasonable settlement can not be obtained, the case is referred by the Chief Disciplinary Counsel’s office to be filed as a grievance. Returning a phone call from CAAP at 1-800-204-2222 ext. 1777 could save a trip to the grievance committee.

A lawyer shall not charge or collect an illegal or unconscionable fee. A fee is unconscionable if a competent lawyer could not form a reasonable belief that the fee is reasonable.

Consider: 1. Time and labor required including difficulty

preclude other employment

fee charged

time limitations imposed by client

amount involved and results

nature of the relationship with client

experience and ability of the lawyer 8. whether fee is fixed or contingent.

A lawyer may not charge a contingent fee in a criminal case. Rule 1.04 (e).

When the lawyer has not regularly represented the client, the basis or the rate of the fee shall be communicated to the client, preferably in writing, before or within a reasonable time after commencing the representation. The Rule strongly recommends that a lawyer use a written contract of employment, effective March 1, 2005 which is the most recent change to the Rules, as the other Rules were adopted January 1, 1990.

Many lawyers put in their contracts that the fee is a non refundable retainer fee. The thought is that this would prevent the client for asking for a refund and prevent the client from being able to pursue a grievance if no refund was made. These types of contracts and employment agreements are not recommended by the State Bar of Texas. One problem is the appearance of overreaching. The court decisions have made it clear this is not an arms length transaction and the client it at a particular disadvantage in the contract negotiation process.

What is a true retainer fee?

A true retainer is not a payment for services. It is an advance fee to secure a lawyer's services, and remunerate him for loss of the opportunity to accept other employment. If the lawyer can substantiate that other employment will probably be lost by obligating himself to represent the client, then the retainer fee should be deemed earned at the moment it is received. If, however, the client discharges the attorney for cause before any opportunities have been lost, or if the attorney withdraws voluntarily, then the attorney should refund an equitable portion of the retainer

Cluck v. Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 214 S.W.3d 736 (Tex. App. Austin 2007) made it clear that simply calling a fee non refundable does not make it so.

Calling the fee a retainer fee does not change an advance fee into a retainer fee. In that case there was a fee of $15,000.00 that the lawyer then billed against. By billing an hourly rate against the fee collected, the lawyer was demonstrating that in fact it was an advanced fee, not a retainer. Because it was an advance fee for services in the future and it had not been earned at the time of the payment, the fee was required to be placed into a trust. Because the lawyer did not place the money into a trust account, the sanction imposed by the State Bar was appropriate.

In Willie v. CFLD, 2014WL586226, (Tex. App. Houston 1st Dist. 2014) the Court of Appeals affirmed the Cluck decision stating that a fee is not earned simply because the contract stated that it was non-refundable. Because the fee was to be billed against, it was an advance fee that must be deposited into a trust account.

A lawyer shall hold funds and other property belonging in whole or in part to clients or third persons that are in the lawyer’s possession in connection with a representation separate from the lawyer’s own property. Such funds shall be

kept in a separate account, designated as a trust or escrow account. Complete records of such account funds shall be kept by the lawyer and shall be preserved for a period of five years after termination of the representation. Unearned fees must be placed into a trust account.

Ethics Rule 611 further complicated the issue of non refundable retainers deposited into an operating account by stating that the Rules of Professional Conduct prohibit such arrangements if the fee charged includes payment for the lawyer’s services on the matter up to the time of trial. The Professional Ethics Committee for the State Bar of Texas decided that such an agreement would be a payment for future services, and as such, an advanced fee which must be deposited into a trust account. The fee can only transferred to the operating account when earned under the terms of the agreement with the client. See State Bar Journal November 2011 p. 944

The Ethics opinions are not binding on the Supreme Court, but they are used by the State Bar as presuasive arguments in grievance matters. According to Larry Boyd’s paper written for the State Bar “Mythology of Nonrefundable flat fees” in which he presents an excellent analysis of Ethics Opinion 611, he writes that the opinion creates an “absolute prohibition of non-refundable flat fees”.

Upon termination of representation, a lawyer shall take steps to the extent reasonably practicable to protect a clients interest, such as giving reasonable notice to the client, allowing time for employment of other counsel, surrendering papers and property to which the client is entitled and refunding any advance payments of fee that has not been earned. The lawyer may retain papers relating to the client to the extent permitted by other law only if such retention will not prejudice the client in the subject matter of the representation.

The Texas Rule is that the file belongs to the client. Upon request and/or termination, the file must be returned to the client. If the lawyer wishes to make a copy and retain one for himself, he is responsible for making the copy. This section also results in a lot of sustained grievances against lawyers who mistakenly believe that they can hold the file hostage for payment of attorney’s fees. Ethics Opinion 610 says that it is not proper to include in the employment contract a statement that there will be a lien on the file for attorney’s fees as rule 1.08 (h) prohibits a lawyer from acquiring a proprietary interest in the cause of action.

However, in order to prove an ethical violation, there must be evidence that the retained file prejudiced the client in the subject matter of the representation. Weiss v. CFLD. 981 S.W.2d 8 (Tex. App. San Antonio 1998). Many questions have arisen about the effect of the Michael Morton Act, that amended Article 39.14 Code of Criminal Procedure, effective January 1, 2014. Section (f) specifically states that the attorney representing the defendant “may not allow that person to have copies of the information provided...” The issue has been raised about whether an attorney could face disciplinary action from the State Bar for refusing to turn over an offense report to a defendant, after the defendant requested his file. It is clear that state law prohibits the attorney from making copies of information obtained from the prosecutor’s office. Subsection (g) states that this can not be interpreted to limit an attorney’s ability to communicate with their client within the Texas Disciplinary rules of Professional Conduct, except for information identifying any victim or witness.

Ethics Opinion 570 from 2006 states that the attorney must turn over all notes unless there is a right to withhold a document pursuant to a legal right or the lawyer is required to withhold the document by court order. This opinion would cover any attorney who refuses to turn over discovery to their client as a part of the request for the file. It states that work product and notes of the attorney must be produced, but the attorney can rely on Article 39.14 C.C.P. in refusing to turn over witness statements and offense reports provided to the attorney. This would comport with Section (d) of Article 39.14 C.C.P. which sets out that when a defendant is pro se the State is not required to provide copies as required when an attorney requests discovery. The argument to be made is that this is not “papers and property to which the client is entitled” as the rule sets out, but the last line of the rule is problematic because these documents will be needed by the client.

In 2014 the Professional Ethics Committee of the State Bar of Texas issued Opinion 646. The question presented was whether as a condition for allowing criminal defense lawyers to obtain information in the prosecutor’s file, a prosecutor may require defense lawyers to agree not to show or provide copies of the information to their clients and agree to waive court ordered discovery in all of the lawyer’s cases. The opinion specifically stated that under the Michael Morton Act, the prosecutor’s office can not demand such conditions for obtaining discovery. The opinion says that the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct require that the prosecutors comply with the Morton Act including making disclosures required by the Act. Unfortunately, the opinion confuses the issue by also stating that a prosecutor is prohibited from requiring the lawyer to not provide copies to their client. In the sentence preceding this statement, the

opinion says that Texas now has an “open file” policy and prosecutors can not require lawyers to agree to any restrictions except those provided by the Act. Opinion 646 does not give lawyers the right to turn over copies to the defendant, in violation of Article 39.14, Code of Criminal Procedure. Another interesting issue came up when the client expressly refused to allow his trial attorney to turn over his file to his appellate/habeas attorney. In re McCann, 422 S.W.3d 701 (Tex. Crim. App. 2013) issued a mandamus to prohibit a trial court from finding the attorney in contempt and to reverse the trial court’s order that the lawyer turn over the file. The Court recognized that since 1918 the Supreme Court of Texas has held that the file belongs to the client and without the client’s consent, the lawyer could not turn over the file. The work product belongs to the client because the lawyer is considered the agent of the client.

Rule 3.03(a)

A lawyer shall not knowingly:

(1) make a false statement of material fact or law to a tribunal;

(2) fail to disclose a fact to a tribunal when disclosure is necessary to avoid assisting a criminal or fraudulent act;

(3) in an ex parte proceeding, fail to disclose to the tribunal an unprivileged fact which the lawyer reasonably believes should be known by that entity for it to make an informed decision;

(4) fail to disclose to the tribunal authority in the controlling jurisdiction known to the lawyer to be directly adverse to the position of the client and not disclosed by opposing counsel; or

(5) offer or use evidence that the lawyer knows to be false.

A lawyer must refuse to offer evidence that he knows to be false. If it comes from the client, the lawyer is justified in seeking to withdraw from the case. If the lawyer does not withdraw or is not allowed to withdraw, he must advise the client that he can not offer the false evidence and he must advise the client of the steps the lawyer will take if the false evidence is offered. If the lawyer discovers the false evidence after its use, the lawyer must seek to persuade the client to correct the false testimony and if that is ineffective, the lawyer is allowed to reveal confidential information under Rule 1.05 (f) which states a lawyer shall reveal confidential information when required to do so by Rule 3.03 (a)(2), 3.03(b) or by Rule 4.01(b).

Dealing with the possibility of perjury by a criminal defendant is complicated by a number of legal issues. The defendant has a due process right guaranteed in the 5th amendment of the U.S. Constitution to present his defense and he has the absolute right to testify, if he chooses. The rules recognize that these rights are attached to the criminal defendant in Rule 1.02(a) (3) which states in a criminal case, the lawyer shall abide by a client’s decision as to a plea to be entered, whether to waive jury trial and whether the client will testify. If the lawyer learns of the proposed perjury prior to trial, and he is unable to dissuade the client from doing so, the lawyer must withdraw from the representation. Rule 1.15.

However, Rule 1.15(c) overrides the ability to withdraw in many criminal cases. It states when ordered to do so by a tribunal, a lawyer shall continue representation notwithstanding good cause for terminating the representation.

Three possible resolutions have been recognized in the United States. The first would allow the defendant to testify by narrative without any guidance from the lawyer. The second proposal would excuse the lawyer completely from any duty to reveal perjury if the perjury is that of the client. Texas has specifically rejected this option.

The rules in Texas require that the lawyer take reasonable remedial measures which can include disclosing the perjury. A defendant has the right to assistance of counsel, the right to testify and the right of confidential communication. However, the client does not have the right to assistance of counsel in committing perjury. The lawyer is to try and dissuade the client from committing perjury or if it has already occurred, the lawyer must try to get the client to correct the false testimony. This needs to be done in the present of another attorney to document the lawyer’s efforts.

Then the lawyer must file a motion to withdraw under Rule 1.15 (a) (1) alleging the representation will result in the violation of the rules of professional conduct or other law. In the motion, the lawyer should quote the language in either Rule 1.15(b) (2) that the client persists in a course of action involving the lawyer’s services that the lawyer reasonably believes may be criminal or fraudulent or as in Rule 1.15(b)(3) that the client has used the lawyer’s services to perpetrate a crime or fraud or Rule 1.15(b)(7) other good cause for withdrawal exists, including vague ethical considerations.

If the motion to withdraw is denied, the lawyer is permitted to reveal the perjury. 3.03(b) if the efforts are unsuccessful, the lawyer shall take the steps to remedy including disclosing the true facts. This should be done to the tribunal

and then the lawyer must abide by the decision of the court. Helton v. State, 670 S.W2d 644 (Tex. Crim. App. 1984) ruled that the lawyer was excused from the rules of confidentiality and he could reveal potential perjury to the court in order to prevent a fraud on the court.

Nix v. Whiteside, 106 S.Ct. 988 (1986) involved a murder defendant who complained that his lawyer threatened to withdraw and inform the court, if he took the stand and committed perjury. On appeal he alleged ineffective assistance of counsel and a denial of his 6th amendment right to counsel. The Supreme Court held that the attorney had acted properly in threatening both to withdraw and to disclose the perjury, as the right to testify does not include the right to testify falsely and the right to counsel does not include the assistance of counseling committing perjury. The Court specifically found that there was no breach of the lawyer’s professional responsibility.

Perjury is such an obvious and flagrant affront to the judicial proceedings, that the Court of Criminal Appeals has held in Butterfield v. State, 992 S.W.2d 448 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999) that a defendant could be compelled to testify, violating his 5th Amendment rights, and then prosecuted for perjury if he lied. His statements made in violation of his 5th Amendment rights could be admitted at his perjury trial.

A lawyer can not advise a lawfully subpoenaed witness to not appear in court. Rule 3.04 states that a lawyer shall not:

(a) unlawfully obstruct another party’s access to evidence....or counsel or assist another to do any such act.

(b) falsify evidence, counsel or assist a witness to testify falsely..... (e) request a person other than a client to refrain from voluntarily giving relevant information to another party unless:

(1) the person is a relative or an employee or other agent of a client; and (2) the lawyer reasonably believes that the person’s interest will not be adversely affected by refraining from giving such information.

Rule 3.04(c)(5) states that in representing a client before a tribunal the lawyer shall not engage in conduct intended to disrupt the proceedings. §36.05 of the Texas Penal Code, Tampering with a witness: A person