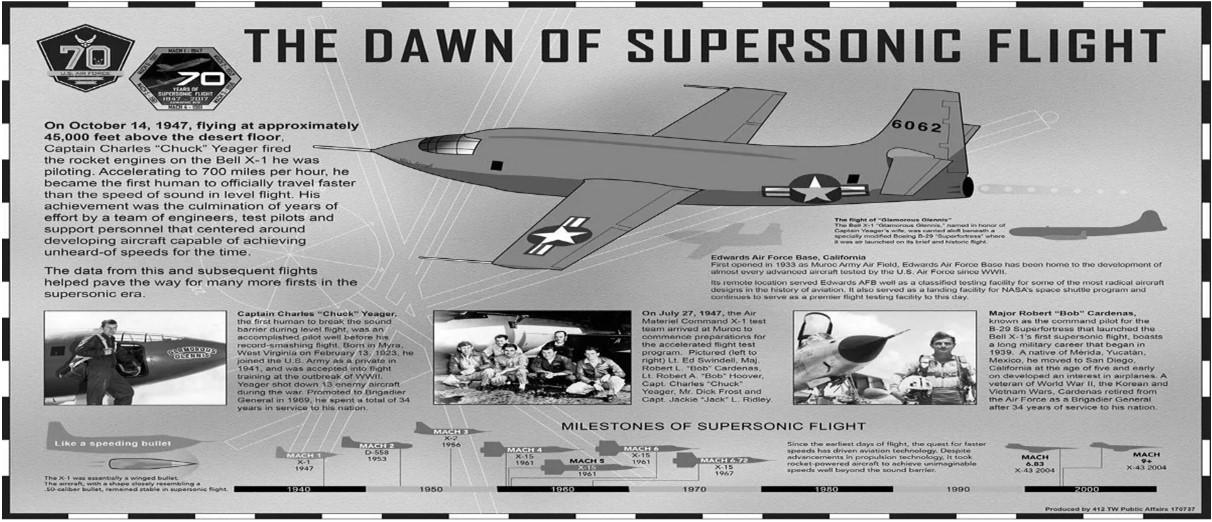

Stuart

Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association

Thursday, November 3, 2022

Betty Blackwell Ethics Dos and Don’ts with Clients

Michael Gross DWI Case Law Update

Gary Trichter Discovery and Pretrial Motion

Friday, November 4, 2022

David Burrows Voir Dire

Doug Murphy Cross of the State’s Blood Expert

Larry Boyd Significant Recent Decisions & Emerging (Disturbing?) Trends in DWI & ALR Law

Lisa Greenberg Punishments and Collateral Consequences of DWI Cases

Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas ::

::

::

Date November 3 4, 2022

The Menger Hotel

Alamo Plaza, San Antonio, Texas

Course Director Bobby Barrera, Michael Gross,

Total CLE Hours 13.5

Thursday,

Kobs, and Gary Trichter

Hours:

Time CLE Topic Speaker

7:30 am Registration and Continental Breakfast

8:10 am Opening Remarks

Bobby Barrera, Michael Gross, Adam Kobs, and Gary Trichter

8:15 am 1.0 Ethics

Betty Blackwell ETHICS

9:15 am 1.0 Case Law

Michael Gross 10:15 am Break

10:30 am 1.0 Discovery and Pretrial Motions Gary Trichter 11:30 am 1.0 Defending Citizens Accused of Drugged Driving Deandra Grant

12:30 pm Lunch on Your Own

1:45 pm 1.0 Cross of the Breath Test Officer and Technical Supervisor Adam Kobs

2:45 pm 1.0 Cross of Arresting Officer

3:45 pm Break

4:00 pm 1.0 SFST

5:00 pm Adjourn

Bobby Barrera

Lisa Martin and Gary Trichter

Date November 3 4, 2022

The Menger Hotel 204 Alamo Plaza, San Antonio, Texas

Course Director Bobby Barrera, Michael Gross, Adam Kobs, and Gary Trichter

Total CLE Hours 13.5

Friday, November 4, 2022

CLE Hours:

Time CLE Topic Speaker

7:45 am Registration and Continental Breakfast

8:10 am Opening Remarks

Bobby Barrera, Michael Gross, Adam Kobs, and Gary Trichter

8:15 am 1.0 Voir Dire David Burrows

9:15 am 1.0 Cross of State’s Blood Expert Doug Murphy

10:15 am Break

10:30 am 1.0 ALR Larry Boyd 11:30 am Lunch on Your Own 12:45 pm 1.0 Investigation Secrets

1:45 pm 1.0 Collateral Problems

2:45 pm Break

Jim Reeves

Lisa Greenberg

3:00 pm 1.0 Blood Evidence Challenges Nnamdi Ekeh

4:00 pm Adjourn

Speaker:

Menger

Alamo Plaza San Antonio, TX 78205

Nueces St

BETTY BLACKWELL Attorney at Law Board Certified in Criminal Law 1306 Nueces Street Austin, Texas 78701 512-479-0149 bettyblackwell@bettyblackwell.com

The Basics. . . . . . . . .

Use a written contract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Neglect . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Malpractice and ineffective assistance of counsel . . . . . . . . . . . .

Failure to Communicate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Who can File a grievance?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Fee Disputes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Non-refundable retainers. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Trust Account Violations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Duty on Termination . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Perjury . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Perjury by Defendant . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . .

Advising Subpoenaed and Potential Witnesses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Conflict of Interest . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Ethics Opinion 690

Compulsory Discipline upon Conviction . . . . . . . . .

Rule changes as of 2021 . . . .

Grievance System . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Investigaion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Investigatory Panels. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Just Cause . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22

Grievance Committee .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .24

District Court . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Grievance Referral Program . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Important State Bar Phone numbers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . 25

Butterfield v. State, 992 S.W.2d 448 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999). . . . . . . . . . 16

Cluck v. Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 214 S.W.3d 736 (Tex. App. Austin 2007) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11

Ex Parte Wilson, 724 S.W.2d 72 (Tex. Crim. App. 1987) . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

Helton v. State, 670 S.W2d 644 (Tex. Crim. App. 1984) . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Henderson v. State, 962 S.W.2d 544 (Tex. Crim. App. 1997)

Hines v. Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 2003 WL 21710589 (Tex. App. Hous 14th ) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

In re McCann, 422 S.W.3d 701 (Tex. Crim. App. 2013). . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

In re Lock, 54 S.W.3d 305 (Tex. S.Ct. 2001) . . . . . . . . . . .. . 19

Lafler v. Cooper, 132 S.Ct. 1376 (2012). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7 Missouri v. Frye, 132 S.Ct. 1399 (2012) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Nix v. Whiteside, 106 S.Ct. 988 (1986) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . .

Padilla v.Kentucky, 130 S.Ct. 1473, (2010. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Santos v, Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 140 S.W.3d 397 (Tex. App. Hous 2004) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Strickland v. Washington, 462 U.S. 1105 (1984) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Walter v. Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 2005 WL 1039970 (Tex. App. Dallas) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Weiss v. CFLD. 981 S.W.2d 8 (Tex. App.- San Antonio 1998) . . . . . . . . .12

Wiggins v. Smith 539 U.S. 510, 123 Sct. 527 (2003) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

Willie v. CFLD, 2014WL586226, (Tex. App. Houston 1st Dist. 2014). . . . .11

All lawyers licensed in Texas are required to abide by the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct. A violation of any of the disciplinary rules can result in a lawyer being sanctioned by the State Bar of Texas’s office of the chief disciplinary counsel. Sanctions can range from private reprimands up to disbarment.

Last year (through May 2020) the State Bar of Texas received 7505 complaints about lawyer misconduct. 5123 were dismissed because the complaint does not describe or allege a violation of the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct. 2202 were sustained complaints which proceeded as a grievance against the attorney. After an investigation,1705 cases were submitted to the summary disposition grievance panel for a dismissal. The following is a discussion of the most common complaints that result in a sanction by the State Bar of Texas and how to avoid them.

Rule 1.04 Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct

(c)when the lawyer has not regularly represented the client, the basis or rate of the fee shall be communicated to the client, preferably in writing, before or within a reasonable time after commencing the representation. A written contract will spell out exactly what work the lawyer has agreed to

undertake and at what fee. Many complaints to the State Bar arise between the lawyer and the client about exactly what the lawyer had agreed to do. Rule 1.02(b) states that a lawyer may limit the scope, objectives and general methods of the representation if the client consents after consultation. However, without a written contract it is a swearing match as to what was said and the grievance can go forward if the State Bar disciplinary counsel has just cause to believe that a rule violation has occurred. Since it is a civil case, the burden to prove the allegations is by a preponderance of the evidence.

Limiting the extent of the representation is one of the most useful aspects of a written contract. Most clients believe that the fee for representation includes the appeal of an adverse decision. However, most lawyers do not intend to include the appeal in the original fee structure.

Explaining whether expert witnesses and other costs of the litigation are the client’s responsibility to pay for or the lawyer’s, is another area of common confusion. In criminal law, explaining that the expunction process is a separate civil proceeding that will not occur without additional fees being paid, is almost always an area of frustration on the part of the client.

Recently malpractice carriers have asked that attorneys include in their written contract exactly the length of time the lawyer will retain the client’s file and that the file will be destroyed unless the client takes possession of the file. Rule 1.14(a) requires that trust account records be kept for five years, so it is recommended that the time period of retaining a file be at least five years. A grievance must be filed within four years so that keeping the file at least five years will insure the records are available to defend any grievance.

Rule 1.04 (d) requires that a contingent fee agreement be in writing and that it must state the method by which the fee is to be determined. It also requires an accounting at the end of the case.

Neglect has been traditionally the number one most common complaint filed by former clients against their attorneys and it is the most likely rule violation to result in an attorney being sanctioned by the State Bar.

A Lawyer shall not neglect a legal matter entrusted to him or frequently fail to carry out completely the obligations that the lawyer owes the client.

Santos v, Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 140 S.W.3d 397 (Tex. App. Hous 2004). The lawyer was sanction for the conscious disregard of a legal matter. He had been paid for an immigration matter and though told of the court date, the lawyer failed to appear. In contrast to the result in Santos, a simple calendaring mistake usually will not cause a lawyer to be sanctioned by the Bar as the comments to Rule 1.01 say “A lawyer who acts in good faith is not subject to discipline, under this provision for isolated inadvertent or unskilled act or omission, tactical error, or error of judgment” .

Malpractice is not always a violation of the Rule of Ethics and ineffective assistant is not necessarily a violation of the Rule of Ethics. An example of malpractice maybe telling a defendant that deferred adjudication will not show up on their record. But this probably doesn’t rise to the level of neglect, only incompetence. Malpractice can occur when a lawyer gives bad legal advice. However, that does not meet the definition of neglect to cause the lawyer to be sanctioned by the State Bar.

The duty to investigate, is part of the effectiveness standard. A lawyer must make a reasonable effort to investigate the case or after discussions with the client, make a reasonable determination that investigation is not necessary. Strickland v. Washington, 462 U.S. 1105 (1984). Wiggins v. Smith 539 U.S. 510, 123 Sct. 527 (2003). Failure to investigate a case may not rise to the level of neglecting a case in violation of the Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct.

Failure to convey the plea offer to the defendant can be neglect and cause a writ to be field. Failure to advise the client of the consequences of a plea offer is ineffective assistance and may also rise to the level of neglect or failure to properly communication with a client as discussed in the next section, under the rules of Professional Conduct.

For example some of the most common criminal cases:

Any plea to a DWI case can result in substantial non-criminal consequences for the person convicted. There are many areas of employment that prohibit a conviction for DWI, including Police Officers, Firefighters, and emergency medical technicians. Many employers have there own employment guidelines which can include dismissal for a DWI. School district often fire teachers if they are convicted of DWI. Canada will not allow anyone to enter the country if they have a DWI conviction.

In POM cases, a jail sentence results in a driver’s license suspension of up to 180 days. A jail sentence is a final conviction and can not be expunged nor can it be sealed if it occurred before September 1, 2015. Drugs cases are eligible for deferred adjudication, which can be eventually sealed, but not expunged. A regular probation stays on the person record for the rest of their

life. Many employers will not hire someone with a drug conviction. Many scholarships to colleges prevent people from applying who have drug convictions. Drug convictions can result in severe immigration consequences as do violation of gun laws. Many apartment complexes will not rent to individuals who have drug convictions on their record. These are just a few of the collateral consequences and many clients will file grievances upon their lawyer if they feel that the lawyer failed to properly advise them of the consequence of their plea.

The most common allegation of neglect in a civil case, is the failure to file a lawsuit within the statute of limitations. Though clearly this is malpractice and the lawyer can be sued, the defense to the grievance is that it was an isolated inadvertent act or omission or a calendaring mistake. But the comments to Rule 1.01 caution that delays can cause the client anxiety and the lawyer has a duty to communicate reasonbly with the client, suggesting that a grievance might be upheld for failure to communicate.

Malpractice refers to negligence or misconduct that fails to meet a standard of care that is recognized in the profession and that results in harm to the client. In Texas it is very hard to sue a criminal defense lawyer for malpractice. The Supreme Court of Texas has decided that only innocent clients have a viable malpractice cause of action against their criminal defense attorney.

Strickland v. Washington, 104 S.Ct. 2052 (1984) set out a two part test. First the counsel’s representation must be deficient and secondly, that deficient performance must have prejudiced the defendant. The bench mark for judging any claim of ineffective assistance of counsel must be whether counsel’s conduct so undermined the proper functioning of the adversarial process that the trial cannot be relied on as having produced a just result. Under the 6th amendment, the defendant must show a reasonable probability that but for the counsel’s errors, the outcome would have been different.

Three important Supreme Court cases have reviewed the performance of criminal defense counsel to determine whether the client should be afforded a new trial. 1. Padilla v.Kentucky, 130 S.Ct. 1473, (2010) held that it was ineffective assistance of counsel to fail to advise a defendant that his plea of guilty to a drug distribution charge would make him subject to automatic deportation. However, Padilla is not retroactive to cases already final. 2. Failure to inform the defendant of a plea offer is ineffective assistance of counsel. Missouri v. Frye, 132 S.Ct. 1399 (2012) 3. In Lafler v. Cooper, 132 S.Ct. 1376

(2012), the defendant was prejudiced by counsel’s advise to reject the plea offer and proceed to trial. The trial counsel’s opinion that the evidence was legally insufficient to convict the defendant, was not sound advice. The defendant was entitled to effective assistance of counsel during the plea negotiations.

When deciding to accept a case, a lawyer should be aware of Rule 1.01(a) which states that a lawyer shall not accept or continue employment in a legal matter which the lawyer knows or should know is beyond the lawyer’s competence. The only exceptions are if the attorney associates another competent attorney on the matter with client consent, or it is an emergency situation. If in doubt, don’t take the case.

Immigration issues have been a focus of the Chief Disciplinary Counsel’s office. In their annual report for 2020, they stated that they received 19 immigration complaints, imposed 11 sanctions and referred 5 to the Grievance Referral Program.

This is the second most common grievance filed and it is usually filed in addition to the allegation of neglect.

A lawyer shall keep a client reasonably informed about the status of a matter and promptly comply with reasonable requests for information. Rule 1.03 (b) states that a lawyer shall explain a matter to the extent reasonably necessary to permit the client to make an informed decision.

In reference to a criminal case the Rules require a lawyer shall promptly inform the client of the substance of any proffered plea bargain. Failure to do so has been held to be ineffective assistance of counsel. Ex Parte Wilson, 724 S.W.2d 72 (Tex. Crim. App. 1987). Failure to communicate a settlement offer in a civil case would be the same misconduct. Under the Rules, the lawyer is allowed to withhold information if believes the clients would react imprudently or if the client is under a disability.

Failure to communicate is alleged in close to half of all grievances filed. The duty is an affirmative obligation and it not dependent on a client’s request for information. Failing to advise a client of an adverse development in a case would be a violation. A lawyer must respond to reasonable requests for information.

Failure to provide adequate information for the defendant to make a decision about whether to have a jury trial or whether to accept a plea offer or a settlement offer can result in an attorney being sanctioned by the State Bar.

Lawyers must be aware of immigration consequences, employment consequences, and licensing consequences, as discussed under the section on Neglect.

Lawyers are not required by the rules to communicate with family members or loved ones. However, one of the biggest misunderstandings by attorneys is who can file a grievance upon them. Many lawyers will answer a grievance filed by a family member saying that they have no attorney client relationship and therefore are not required to answer this grievance. This is wrong.

Complaints with the State Bar may be filed by anyone. The complaint does not have to be filed by the client. There does not have to be an attorney client relationship for the person to file a complaint with the State Bar. Hines v. Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 2003 WL 21710589 (Tex. App. Hous 14th ) The Father of the client filed the complaint and the respondent attorney’s theory was that there could be no sanction because he represented the son. The Court made it clear that anyone can bring to the attention of the bar a rule violation. In addition, any alleged misconduct does not have to be in the course of an attorney client relationship for the State Bar to prosecute a violation under Rule 804(a)(3) which states that a lawyer shall not engage in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation. Walter v. Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 2005 WL 1039970 (Tex. App. Dallas). For example, a lawyer can be disciplined for actions taken as the executor of an estate, even though the lawyer may have no attorney client relationship with the beneficiaries of the will.

Rule 803 (a) requires a lawyer having knowledge that another lawyer has committed professional misconduct that raises a substantial question as to that lawyers honesty, trustworthiness or fitness as a lawyer, to inform the Chief Disciplinary Counsel’s office (CDC). The only exception is for mental illness or chemical impairment in which the lawyer can report the conduct to the Lawyer Assistant Program or the information is protected by confidentiality under Rule 1.05 or is obtained through counseling programs. Rule 1.05, Confidential Information, includes both privileged information and unprivileged client information which a lawyer shall not reveal except if provided by the rules.

Texas Lawyers Assistance Program’s phone number is 1-800-204-2222 ext. 1460. Conversations are confidential and referrals are available for help with mental illness, substance abuse or impairment by physical illness. The goal is to rehabilitate lawyers and help them resume practicing law.

Fee disputes constitute a large number of complaints. Those complaints are first referred to the client attorney assistant program (CAAP) and to the local fee dispute committees of local bar associations. CAAP’s stated purpose is to try and work out a settlement so that the case does not proceed to a grievance. Their number is 1-800-204-2222 ext. 1777. If a reasonable settlement can not be obtained, the case is referred by the Chief Disciplinary Counsel’s office to be filed as a grievance. Returning a phone call from CAAP at 1 800 204 2222 ext. 1777 could save a trip to the grievance committee.

A lawyer shall not charge or collect an illegal or unconscionable fee. A fee is unconscionable if a competent lawyer could not form a reasonable belief that the fee is reasonable.

Consider:

1. Time and labor required including difficulty

2. preclude other employment

fee charged

time limitations imposed by client

amount involved and results

nature of the relationship with client

7. experience and ability of the lawyer

8. whether fee is fixed or contingent.

A lawyer may not charge a contingent fee in a criminal case. Rule 1.04 (e).

When the lawyer has not regularly represented the client, the basis or the rate of the fee shall be communicated to the client, preferably in writing, before or within a reasonable time after commencing the representation. The Rule strongly recommends that a lawyer use a written contract of employment, effective March 1, 2005 which is the most recent change to the Rules, as the other Rules were adopted January 1, 1990.

Many lawyers put in their contracts that the fee is a non-refundable retainer fee. The thought is that this would prevent the client for asking for a refund and prevent the client from being able to pursue a grievance if no refund

was made. These types of contracts and employment agreements are not recommended by the State Bar of Texas. One problem is the appearance of overreaching. The court decisions have made it clear this is not an arms length transaction and the client it at a particular disadvantage in the contract negotiation process.

A true retainer is not a payment for services. It is an advance fee to secure a lawyer's services, and remunerate him for loss of the opportunity to accept other employment. If the lawyer can substantiate that other employment will probably be lost by obligating himself to represent the client, then the retainer fee should be deemed earned at the moment it is received. If, however, the client discharges the attorney for cause before any opportunities have been lost, or if the attorney withdraws voluntarily, then the attorney should refund an equitable portion of the retainer.

Cluck v. Commission for Lawyer Discipline, 214 S.W.3d 736 (Tex. App. Austin 2007) made it clear that simply calling a fee non-refundable does not make it so.

Calling the fee a retainer fee does not change an advance fee into a retainer fee. In that case there was a fee of $15,000.00 that the lawyer then billed against. By billing an hourly rate against the fee collected, the lawyer was demonstrating that in fact it was an advanced fee, not a retainer. Because it was an advance fee for services in the future and it had not been earned at the time of the payment, the fee was required to be placed into a trust. Because the lawyer did not place the money into a trust account, the sanction imposed by the State Bar was appropriate.

In Willie v. CFLD, 2014WL586226, (Tex. App. Houston 1st Dist. 2014) the Court of Appeals affirmed the Cluck decision stating that a fee is not earned simply because the contract stated that it was non-refundable. Because the fee was to be billed against, it was an advance fee that must be deposited into a trust account.

A lawyer shall hold funds and other property belonging in whole or in part to clients or third persons that are in the lawyer’s possession in connection with a representation separate from the lawyer’s own property. Such funds shall be kept in a separate account, designated as a trust or escrow account. Complete records of such account funds shall be kept by the lawyer and shall be preserved for a period of five years after termination of the representation. Unearned fees must be placed into a trust account.

Ethics Rule 611 further complicated the issue of non-refundable retainers deposited into an operating account by stating that the Rules of Professional Conduct prohibit such arrangements if the fee charged includes payment for the lawyer’s services on the matter up to the time of trial. The Professional Ethics Committee for the State Bar of Texas decided that such an agreement would be a payment for future services, and as such, an advanced fee which must be deposited into a trust account. The fee can only transferred to the operating account when earned under the terms of the agreement with the client. See State Bar Journal November 2011 p. 944

The Ethics opinions are not binding on the Supreme Court, but they are used by the State Bar as presuasive arguments in grievance matters. According to Larry Boyd’s paper written for the State Bar “Mythology of Nonrefundable flat fees” in which he presents an excellent analysis of Ethics Opinion 611, he writes that the opinion creates an “absolute prohibition of non-refundable flat fees”.

Upon termination of representation, a lawyer shall take steps to the extent reasonably practicable to protect a clients interest, such as giving reasonable notice to the client, allowing time for employment of other counsel, surrendering papers and property to which the client is entitled and refunding any advance payments of fee that has not been earned. The lawyer may retain papers relating to the client to the extent permitted by other law only if such retention will not prejudice the client in the subject matter of the representation. The Texas Rule is that the file belongs to the client. Upon request and/or termination, the file must be returned to the client. If the lawyer wishes to make a copy and retain one for himself, he is responsible for making the copy. This section also results in a lot of sustained grievances against lawyers who mistakenly believe that they can hold the file hostage for payment of attorney’s fees. Ethics Opinion 610 says that it is not proper to include in the employment contract a statement that there will be a lien on the file for attorney’s fees as rule 1.08 (h) prohibits a lawyer from acquiring a proprietary interest in the cause of action.

However, in order to prove an ethical violation, there must be evidence that the retained file prejudiced the client in the subject matter of the representation. Weiss v. CFLD. 981 S.W.2d 8 (Tex. App. San Antonio 1998).

Many questions have arisen about the effect of the Michael Morton Act,

that amended Article 39.14 Code of Criminal Procedure, effective January 1, 2014. Section (f) specifically states that the attorney representing the defendant “may not allow that person to have copies of the information provided...” The issue has been raised about whether an attorney could face disciplinary action from the State Bar for refusing to turn over an offense report to a defendant, after the defendant requested his file. It is clear that state law prohibits the attorney from making copies of information obtained from the prosecutor’s office. Subsection (g) states that this can not be interpreted to limit an attorney’s ability to communicate with their client within the Texas Disciplinary rules of Professional Conduct, except for information identifying any victim or witness.

Ethics Opinion 570 from 2006 states that the attorney must turn over all notes unless there is a right to withhold a document pursuant to a legal right or the lawyer is required to withhold the document by court order. This opinion would cover any attorney who refuses to turn over discovery to their client as a part of the request for the file. It states that work product and notes of the attorney must be produced, but the attorney can rely on Article 39.14 C.C.P. in refusing to turn over witness statements and offense reports provided to the attorney. This would comport with Section (d) of Article 39.14 C.C.P. which sets out that when a defendant is pro se the State is not required to provide copies as required when an attorney requests discovery. The argument to be made is that this is not “papers and property to which the client is entitled” as the rule sets out, but the last line of the rule is problematic because these documents will be needed by the client.

In 2014 the Professional Ethics Committee of the State Bar of Texas issued Opinion 646. The question presented was whether as a condition for allowing criminal defense lawyers to obtain information in the prosecutor’s file, a prosecutor may require defense lawyers to agree not to show or provide copies of the information to their clients and agree to waive court-ordered discovery in all of the lawyer’s cases. The opinion specifically stated that under the Michael Morton Act, the prosecutor’s office can not demand such conditions for obtaining discovery. The opinion says that the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct require that the prosecutors comply with the Morton Act including making disclosures required by the Act. Unfortunately, the opinion confuses the issue by also stating that a prosecutor is prohibited from requiring the lawyer to not provide copies to their client. In the sentence preceding this statement, the opinion says that Texas now has an “open file” policy and prosecutors can not require lawyers to agree to any restrictions except those provided by the Act. Opinion 646 does not give lawyers the right to turn over copies to the defendant, in violation of Article 39.14, Code of Criminal Procedure.

Another interesting issue came up when the client expressly refused to allow his trial attorney to turn over his file to his appellate/habeas attorney. In re McCann, 422 S.W.3d 701 (Tex. Crim. App. 2013) issued a mandamus to prohibit a trial court from finding the attorney in contempt and to reverse the trial court’s order that the lawyer turn over the file. The Court recognized that since 1918 the Supreme Court of Texas has held that the file belongs to the client and without the client’s consent, the lawyer could not turn over the file. The work product belongs to the client because the lawyer is considered the agent of the client.

A lawyer shall not knowingly:

(1) make a false statement of material fact or law to a tribunal;

(2) fail to disclose a fact to a tribunal when disclosure is necessary to avoid assisting a criminal or fraudulent act;

(3) in an ex parte proceeding, fail to disclose to the tribunal an unprivileged fact which the lawyer reasonably believes should be known by that entity for it to make an informed decision;

(4) fail to disclose to the tribunal authority in the controlling jurisdiction known to the lawyer to be directly adverse to the position of the client and not disclosed by opposing counsel; or

(5) offer or use evidence that the lawyer knows to be false.

A lawyer must refuse to offer evidence that he knows to be false. If it comes from the client, the lawyer is justified in seeking to withdraw from the case. If the lawyer does not withdraw or is not allowed to withdraw, he must advise the client that he can not offer the false evidence and he must advise the client of the steps the lawyer will take if the false evidence is offered. If the lawyer discovers the false evidence after its use, the lawyer must seek to persuade the client to correct the false testimony and if that is ineffective, the lawyer is allowed to reveal confidential information under Rule 1.05 (f) which states a lawyer shall reveal confidential information when required to do so by Rule 3.03 (a)(2), 3.03(b) or by Rule 4.01(b).

Dealing with the possibility of perjury by a criminal defendant is

complicated by a number of legal issues. The defendant has a due process right guaranteed in the 5th amendment of the U.S. Constitution to present his defense and he has the absolute right to testify, if he chooses. The rules recognize that these rights are attached to the criminal defendant in Rule 1.02(a) (3) which states in a criminal case, the lawyer shall abide by a client’s decision as to a plea to be entered, whether to waive jury trial and whether the client will testify. If the lawyer learns of the proposed perjury prior to trial, and he is unable to dissuade the client from doing so, the lawyer must withdraw from the representation. Rule 1.15.

However, Rule 1.15(c) overrides the ability to withdraw in many criminal cases. It states when ordered to do so by a tribunal, a lawyer shall continue representation notwithstanding good cause for terminating the representation.

Three possible resolutions have been recognized in the United States. The first would allow the defendant to testify by narrative without any guidance from the lawyer. The second proposal would excuse the lawyer completely from any duty to reveal perjury if the perjury is that of the client. Texas has specifically rejected this option.

The rules in Texas require that the lawyer take reasonable remedial measures which can include disclosing the perjury. A defendant has the right to assistance of counsel, the right to testify and the right of confidential communication. However, the client does not have the right to assistance of counsel in committing perjury. The lawyer is to try and dissuade the client from committing perjury or if it has already occurred, the lawyer must try to get the client to correct the false testimony. This needs to be done in the present of another attorney to document the lawyer’s efforts.

Then the lawyer must file a motion to withdraw under Rule 1.15 (a) (1) alleging the representation will result in the violation of the rules of professional conduct or other law. In the motion, the lawyer should quote the language in either Rule 1.15(b) (2) that the client persists in a course of action involving the lawyer’s services that the lawyer reasonably believes may be criminal or fraudulent or as in Rule 1.15(b)(3) that the client has used the lawyer’s services to perpetrate a crime or fraud or Rule 1.15(b)(7) other good cause for withdrawal exists, including vague ethical considerations.

If the motion to withdraw is denied, the lawyer is permitted to reveal the perjury. 3.03(b) if the efforts are unsuccessful, the lawyer shall take the steps to remedy including disclosing the true facts. This should be done to the tribunal and then the lawyer must abide by the decision of the court. Helton v. State, 670 S.W2d 644 (Tex. Crim. App. 1984) ruled that the lawyer was excused from the rules of confidentiality and he could reveal potential perjury to the court in order to prevent a fraud on the court.

Nix v. Whiteside, 106 S.Ct. 988 (1986) involved a murder defendant who complained that his lawyer threatened to withdraw and inform the court, if he took the stand and committed perjury. On appeal he alleged ineffective assistance of counsel and a denial of his 6th amendment right to counsel. The Supreme Court held that the attorney had acted properly in threatening both to withdraw and to disclose the perjury, as the right to testify does not include the right to testify falsely and the right to counsel does not include the assistance of counseling committing perjury. The Court specifically found that there was no breach of the lawyer’s professional responsibility.

Perjury is such an obvious and flagrant affront to the judicial proceedings, that the Court of Criminal Appeals has held in Butterfield v. State, 992 S.W.2d 448 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999) that a defendant could be compelled to testify, violating his 5th Amendment rights, and then prosecuted for perjury if he lied. His statements made in violation of his 5th Amendment rights could be admitted at his perjury trial.

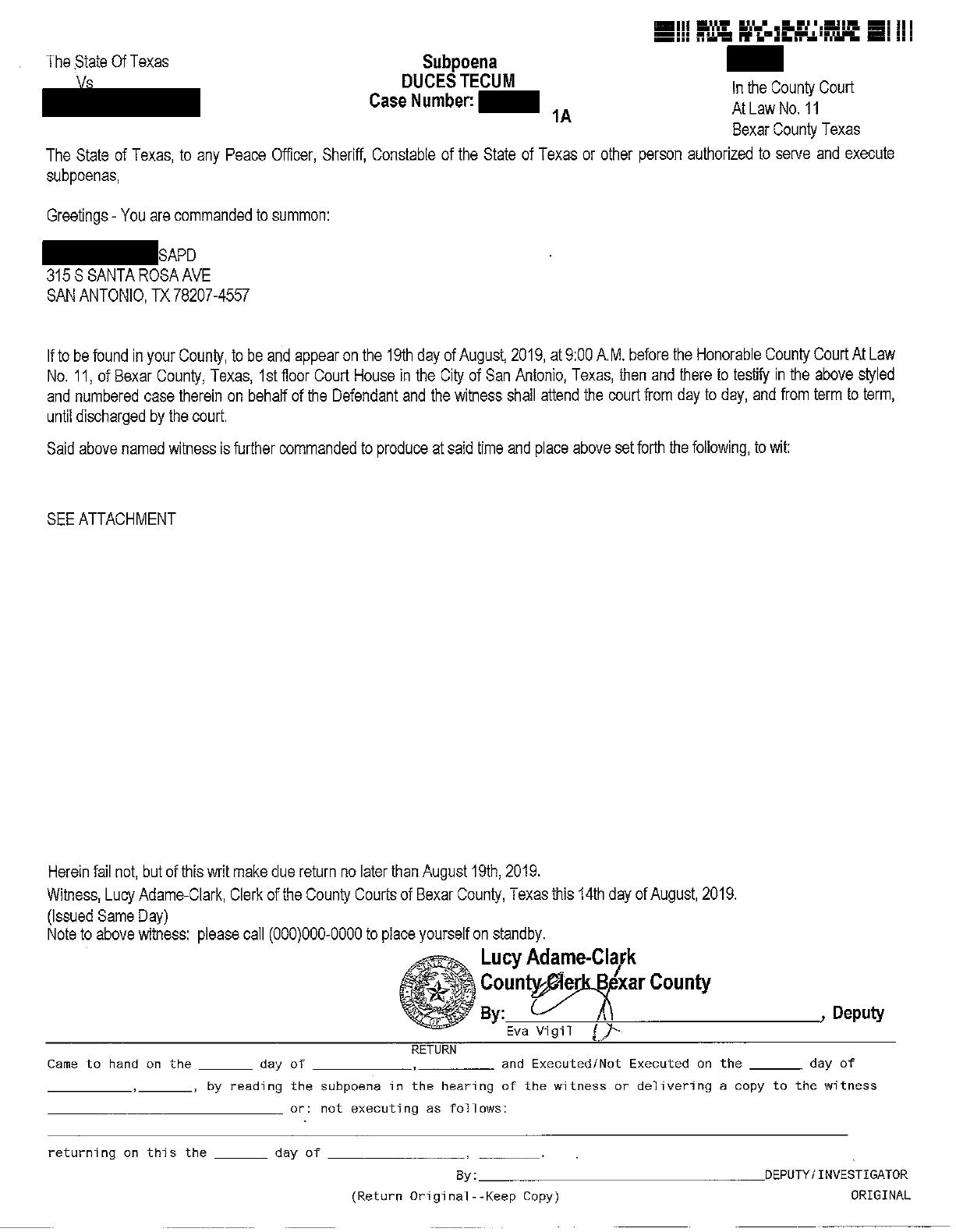

A lawyer can not advise a lawfully subpoenaed witness to not appear in court. Rule 3.04 states that a lawyer shall not:

(a) unlawfully obstruct another party’s access to evidence....or counsel or assist another to do any such act.

(b) falsify evidence, counsel or assist a witness to testify falsely.....

(e) request a person other than a client to refrain from voluntarily giving relevant information to another party unless:

(1) the person is a relative or an employee or other agent of a client; and

(2) the lawyer reasonably believes that the person’s interest will not be adversely affected by refraining from giving such information.

Rule 3.04(c)(5) states that in representing a client before a tribunal the lawyer shall not engage in conduct intended to disrupt the proceedings.

§36.05 of the Texas Penal Code, Tampering with a witness: A person commits an offense if, with intent to influence the witness, he offers, confers, or agrees to confer any benefit on a witness or prospective witness in an official proceeding or coerces a witness or prospective witness in an official proceeding: (1) to testify falsely;

(2) to withhold any testimony, information, document or thing, (3) to elude legal process summoning him to testify or supply evidence; (4) to absent himself from an official proceeding to which he has been legally summoned; or

(5) to abstain from, discontinue, or delay the prosecution of another. Article 24.04 of the Code of Criminal Procedure sets out how a subpoena can be served:

(1) reading the subpoena in the hearing of the witness;

(2) delivering a copy of the subpoena to the witness;

(3) electronically transmitting a copy of the subpoena, acknowledgment of receipt requested, to the last known electronic address of the witness; or

(4) mailing a copy of the subpoena by certified mail, return receipt requested, to the last known address of the witness.

It is both unethical and under the above circumstances illegal for an attorney to advise a subpoenaed witness not to appear in court. Rule 8.04(a) A lawyer shall not (4) engage in conduct constituting obstruction of justice.

The comments to the Rules of Disciplinary Procedures discuss that fair competition in the adversary system is secured by prohibitions against improperly influencing witnesses.

(a) A lawyer shall not represent opposing parties to the same litigation.

(b) In other situations and except to the extent permitted by paragraph (c), a lawyer shall not represent a person if the representation of that person:

(1) involves a substantially related matter in which that person’s interest are materially and directly adverse to the interest of another client of the lawyer or the lawyer’s firm; or

(2) reasonably appears to be or become adversely limited by the lawyers or law firm’s responsibilities to another client or to a third person or by the lawyers or law firm’s own interest.

(c)A lawyer may represent a client in the circumstances described in (b) if:

(1) the lawyer reasonably believes the representation of each client will not be materially affected; and

(2) each affected or potentially affected client consents to such representation after full disclosure of the existence, nature, implications, and possible adverse consequences of the common representation and the advantages involved, if any.

(e) If a lawyer has accepted representation in violation of this Rule, or if multiple representation properly accepted becomes improper under this Rule, the lawyer shall promptly withdraw from one or more representations to the extent necessary for any remaining representation not to be in violation of these Rules.

Comment 2 to Rule 1.06 gives guidance as to the meaning of conflict of interest. The term opposing parties as used in this Rule contemplates a situation where a judgment favorable to one of the parties will directly impact unfavorably upon the other party. Moreover, as a general proposition loyalty to a client prohibits undertaking representation directly adverse to the representation of that client in a substantially related matter unless the client’s fully informed consent is obtained and unless the lawyer reasonably believes that the lawyer’s representation will be reasonably protective of that client’s interest.

Comment 3 recommends that ordinarily a lawyer should decline to represent multiple defendants in a criminal case due to the grave potential for conflict of interest. Comment 8 on fully informed consent recommends that the disclosure of the conflict of interest and the consent be in writing, though it is not required. It would be prudent, the rules states, for the lawyer to provide potential dual clients with at least a written summary of the considerations disclosed.

Most believe that having sex with clients is an automatic conflict of interest.Though technically difficult fit under this Rule, this behavior will cause the State Bar to take a heightened view of any Rule violation however minor Comment 4 to the Conflict Rules discusses the conflict that may occur with a client and the lawyer’s own interests (insert sexual interest at this point) and how it can cause a lawyer to not be able to consider, recommend or carry out the appropriate cause of action for one client because of his/her own interests. This results, for example, in a client alleging a lawyer did not conclude the representation in a timely manner in order to continue the sexual relationship. This would be a violation of Rule 1.06(b)(2).

Sometimes the clients who have engaged in sexual relationship with their attorney will claim a violation of Rule 1.08(h). A lawyer shall not acquire a proprietary interest in the cause of action or subject matter of litigation the lawyer is conducting for the client… {with some exceptions that do not apply here}. The scenario that the aggrieved client can allege is that the attorney proposed marriage, thereby potentially giving the attorney an interest in the cause of action. All of which forces the State Bar’s Office of Disciplinary Counsel to investigate the private life of the attorney.

After years of debate, planning and discussion that began in 2003, the

Bar recommended in 2010 to attorneys that the Rules be amended to specifically prohibit sex with clients, to bring Texas in to conformity with almost every other state. On February 17th, 2011, the lawyers of the State of Texas voted to reject the proposal, so there is still no specific Rule prohibiting sexual relations with clients, other than common sense.

New Rule 6.05 approved in 2021, makes it clear that if an attorney engages in representation on a limited pro bono basis, or for a nonprofit, there is no imputed conflict of interest and Rules 1.06, 1.07 and 1.09 do not prohibit the representation.

A prosecutor requested an ethics opinion from the State Bar’s Professional Ethics committee on whether a defense lawyer violated the Rules of Professional Conduct by failing to turn over tangible evidence from the lawyer’s client, when requested. The prosecutor alleged that the Rule 3.04(a) requires the lawyer to not obstruct another party’s access to evidence and rule 8.04(a)(4) prohibits a lawyer from engaging in conduct constituting obstruction of justice.

The facts were that the lawyer went to jail to visit his client and the client gave him several letters written to the client from the victim in the case containing relevant information. The prosecutor asked to inspect the letters and the lawyer refused, only allowing inspection after being ordered to do so by the court after a hearing.

The Committee correctly notes that there is no authority holding that it is a crime for a lawyer to accept and retain ordinary tangible evidence from a client accused of a crime, so that this would not violate Rule 8.04. They also note that there is no discovery process in Texas that allows the State to obtain evidence from a criminal defendant, so that maintaining custody of ordinary evidence would not be unlawful and therefore not violate Rule 3.04(a).

The Committee recognizes that there are types of special criminal evidence that the lawyer has a self executing obligation to turn over. Generally this type of evidence includes contraband, the instrumentalities of a crime, or the fruits of a crime. Examples are illegal narcotics, a murder weapon, and stolen property. The rationals for such duty are that (1) possession by anyone is illegal, (2) prepare the client’s defense does not reuqire the lawyer to possess the evidence and (3) any evanescent evidence (such as fingerprints) could degrade while in the lawyer’s possession.

Henderson v. State, 962 S.W.2d 544 (Tex. Crim. App. 1997) held that the trial court properly compelled the defense lawyer to turn over maps of the location of the kidnapped child received from the client when the child might possibly still be alive, but the Court noted that neither the client’s communication

to the attorney nor the attorney’s communications to law enforcement could be admitted at trial.

The Committee comes to correct conclusion that the lawyer did not violate any of the Rules of Professional Conduct. The lawyer had no obligation to turn over this ordinary tangible evidence to the prosecuting attorney. The Committee goes on to state that the lawyer also had no obligation to accept custody of the evidence, and assuming that the lawyer knows the client won’t destroy the evidence, the Committee’s view is that the prudent course is for the lawyer to decline the client’s request to accept custody of the evidence relate to an alleged crime.

When an attorney licensed to practice law in Texas has been convicted of an Intentional Crime or has been placed on probation for an Intentional Crime with or without an adjudication of guilt, the CDC shall initiate a disciplinary action seeking compulsory discipline pursuant to this part. Proceedings are not exclusive in that an attorney may be disciplined as a result of the underlying facts as well as being disciplined upon the conviction or probation through deferred adjudication.

Intentional crime means (1) any serious crime that requires proof of knowledge or intent as an essential element or (2) any crime involving misapplication of money or other property held as a fiduciary.

Rules. Rule 8.04(a)(2) A lawyer shall not commit a serious crime or commit any other criminal act that reflect adversely on the lawyers honesty, trustworthiness or fitness as a lawyer in other respects. Serious crime is defined as barratry; any felony involving moral turpitude; any misdemeanor involving theft, embezzlement or fraudulent or reckless misappropriation of money or other property; or any attempt, conspiracy or solicitation of another to commit any of the foregoing crimes. Possession of cocaine, is not a serious crime for which a lawyer can receive a compulsory discipline based upon the sentence alone of probation, deferred adjudication, or a final conviction. In re Lock, 54 S.W.3d 305 (Tex. S.Ct. 2001).

During compulsory discipline proceedings, the Board of Disciplinary Appeals decides if a lawyer has been convicted or placed on deferred adjudication for an intentional crime, which is defined as a serious crime in 8.04(b). The Board shall disbar the lawyer unless the Board suspends the license during the term of probation. Rule 8.05 and 8.06 of the Texas Rules of Disciplinary Procedure.

When an attorney has been convicted of an Intentional Crime, and that conviction has become final, or the attorney has accepted probation with or without an adjudication of guilt for an Intentional crime, the attorney shall be disbarred unless the Board of Disciplinary Appeals, suspends his or her license to practice law.

If an attorney’s sentence upon conviction of a serious crime is fully probated, or if an attorney receives probation through deferred adjudication in connection with a serious crime, the attorney’s license to practice law shall be suspended during the term of probation. If the probation is revoked, the attorney shall be disbarred.

8.03 was amended in 2018 to require that an attorney convicted of or placed on deferred adjudication by any court for barratry, any felony, or for a misdemeanor involving theft, embezzlement,or fraud, or reckless misappropriation of money, or property, including a conviction or sentence of probation for attempt, conspiracy, or solicitation, must report the conviction or deferred adjudication to the State Bar of Texas. The lawyer must also notify the CDC when the lawyer has been disciplined by an attorney regulatory agency of another jurisdiction. Notice must be given within 30 days. New rule 8.03(f) approved in 2021 requires notice of any sanction imposed on the lawyer in federal court or by a federal agency, except a letter of warning or admonishment.

Rule changes adopted 2021:

Rule 1.16 in reference to diminished capacity was amended at the proposal of the probate lawyers. It allows a lawyer to consult with family members, other providers concerning the mental health of a client, and if the lawyer chooses to do so, there is no confidentiality violation. If a lawyer has a reasonable belief that a client maybe suicidal, the lawyer may, but is not required to, seek treatment, or outside help without the lawyer violating any confidences of the client.

The advertising rules were substantially re written to allow Tradenames to be used and to address probono programs, and social media. Rule 7.01 was amended to address constitutional distinctions of those substantially motivated by puncuniary interests, so that non profits are not covered.

The Supreme Court of Texas has the power to regulate the practice of law as set out in the Texas Constitution. The statutory authority to regulate the practice of law is established in the State Bar Act which directs the State Bar to establish disciplinary and disability procedures. The Supreme Court has adopted the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct (TDRPC) which are the substantive ethics rules.

The Texas Rules of Disciplinary Procedure (TRDP) sets out the procedural grievance process. The Commission for Lawyer Discipline (CFLD) is a permanent committee of the State Bar comprised of 12 members, 6 attorneys and 6 public members. The CFLD is the client for all complaints not dismissed by a summary disposition panel. The Commission reviews the structure, function and effectiveness of the discipline system and reports to the Supreme Court and the Board of Directors.

CFLD monitors and evaluates the Chief Disciplinary Counsel (CDC). The CDC administers the attorney disciplinary system. The CDC reviews and screens all information relating to misconduct. It rejects all inquiries and investigates all complaints to determine just cause. CDC recommends dismissal of complaints to the Summary Disposition Panels. CDC is accountable only to the Commission for Lawyer Discipline.

The District Grievance Committees are divided into state geographic disciplinary districts. They act through panels of 2/3 attorneys and 1/3 public members. The local grievance committees conduct summary disposition dockets, investigatory and evidentiary hearings.

If the grievance is determined to be a Complaint, the Respondent (attorney) shall be provided a copy of the complaint with notice to respond in writing to the allegations. The Respondent shall deliver the response to both the CDC and the Complainant within thirty days of the receipt of the notice.

No more than sixty days after the date by which the Respondent must file a written response to the Complaint, the chief Disciplinary Counsel shall investigate the complaint and determine whether there is Just Cause. Rule 2.12 TRDP. A Just Cause finding is made if a reasonably intelligent and prudent person would believe that an attorney has committed one or more acts of

professional misconduct requiring that a sanction be imposed. If the CDC determines that Just Cause does not exist, they shall place the complaint on a Summary Disposition Panel docket. This is presented to the local grievance committee without the appearance of the Respondent (attorney) or the Complainant. There is no appeal from the Panel=s determination that the complaint should be dismissed. If they fail to dismiss the complaint, it shall be placed on a hearing docket.

At this stage of the investigation the CDC may issue subpoenas in accordance with Rule 21a of the Texas Rules of Civil Procedure. The Respondent, attorney or witness must present any objection to the chair of the Investigatory Panel, if one is set, or to the Committee Chair. The CDC may seek enforcement through district court.

The Chief Disciplinary Counsel may set a Complaint for an investigatory hearing. It is a nonadversarial proceeding that may be conducted by teleconference. The chair of the Investigatory Panel may administer oaths and may set forth procedures for eliciting evidence, including witness testimony. Witness examination may be conducted by the Chief Disciplinary Counsel, the Respondent, or the Panel. An investigatory hearing is strictly confidential and any record may be released only for use in a disciplinary matter. An investigatory hearing may result in a Sanction negotiated with the Respondent or in the Chief Disciplinary Counsel’s dismissing the Complaint or finding Just Cause. The terms of a negotiated Sanction must be in a written judgment with findings of fact and conclusions of law. The judgment must be entered into the record by the chair of the Investigatory Panel and signed by the Chief Disciplinary Counsel and the Respondent.

If the investigatory panel hearing does not resolve the complaint and the CDC or the investigatory panel has determined Just Cause exists, they shall give the Respondent written notice of the acts and/or omissions engaged in by the Respondent and the Rule of Professional Conduct that the CDC contends has been violated.

A Respondent who has been give notice of the allegations and Rule violations complained of must serve the CDC with his Election of District Court or an Evidentiary Panel of the Grievance Committee. The Election must be in writing and it must be served upon the CDC no later than twenty days after the

receipt of the notice of the allegations. Failure to timely elect shall conclusively be deemed as an election to proceed before the evidentiary panel of the local grievance committee.

If the Respondent elects or defaults by failing to timely elect, the hearing will be held in front of the local grievance committee. A Private Reprimand is only available at this proceeding and is not available if the Respondent elects a district court proceeding. The CDC must file a petition within 60 days of the election deadline. All proceedings are confidential, and the burden of proof is on the CFLD by a preponderance of the evidence. Respondent must be served with the petition by certified mail or other means permitted by the Rules of Civil Procedure. Respondent must file an answer to this petition.

The committee can dismiss and refer the matter to CAAP (Client Attorney Assistance Program). The grievance committee can find that the Respondent suffers from a disability and refer the case to BODA (Board of Disciplinary Appeals) or they can find professional misconduct and impose sanctions. There is a separate hearing on sanctions. Sanctions can include private reprimands, public reprimands, probation, suspension or disbarment. CFLD or Respondent has the right to appeal the decision to BODA, but the complainant does not. Judgment of disbarment cannot be stayed.

The Texas Rules of Civil Procedure apply and the CDC files a petition on behalf of the CFLD with the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court appoints a judge who does not reside in Respondent=s administrative district. The Respondent may request a jury trial, and like the Evidentiary Proceeding the Respondent once served with the petition must file an answer. If misconduct is found, the judge determines the appropriate sanction. A Private Reprimand is not available and the court retains jurisdiction to enforce its judgments. A final judgment of the district court is appealed as in any other civil case. A judgment of disbarment or order revoking probation can not be stayed.

For more explicit details of the procedures used in District Court or in the local grievance committee hearings, see the Texas Rules of Disciplinary Procedure that can be found online at Texasbar.com

To participate in the program, the lawyer must meet certain

eligibility criteria and agree to meet with the program administrator for an assessment of the issues that need to be addressed. The lawyer must agree in writing to complete specific terms and conditions, including restitution if appropriate, by a date certain and to pay for any costs associated with those terms and conditions. If the lawyer agrees to participate and completes the terms in a timely manner, the Office of Chief Disciplinary Counsel will recommend to the Commission for Lawyer Discipline that the underlying grievance be dismissed. If the lawyer does not fully complete the terms of the agreement in a timely manner, the underlying grievance will move forward through the usual disciplinary process.

Respondent Attorney has not been disciplined within the prior 3 years.

Respondent Attorney has not been disciplined for similar conduct within the prior 5 years.

Misconduct does not involve misappropriation of funds or breach of fiduciary duties.

Misconduct does not involve dishonesty, fraud or misrepresentation.

Misconduct did not result in substantial harm or prejudice to client or complainant.

Respondent Attorney maintained cooperative attitude toward the proceedings.

Participation is likely to benefit respondent attorney and further the goal of protection of the public.

Misconduct does not constitute a crime which would subject respondent attorney to Compulsory Discipline under Part VIII of the Texas Rules of Disciplinary Procedure.

Important Numbers at the State Bar:

Client Attorney Assistant Program:

1 800 204 2222 Ext. 1777

Ethics Hotline

1-800-532-3947

Law Office Management

Lawyers Assistance Program

1 800 343 8527

Advertising Review

1-800-566-4616

2022 The Menger Hotel 204 Alamo Plaza San Antonio, TX 78205

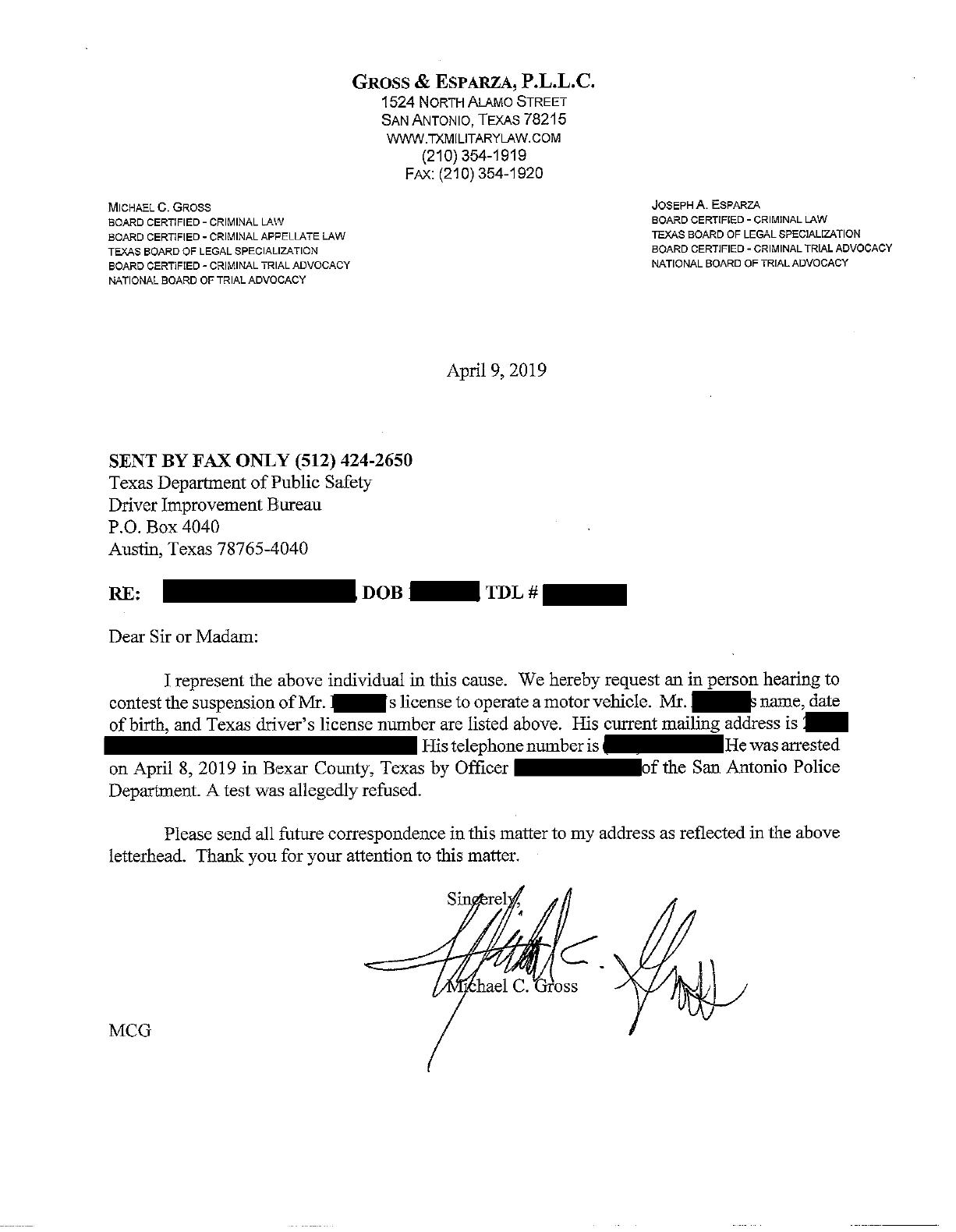

Speaker: Michael Gross 1524 N Alamo St, San Antonio, TX 78215 (210) 354 1919 Phone (210) 354 1920 Fax bettyblackwell@bettyblackwell.com Email www.bettyblackwell.com Website

::

Michael C. Gross Gross & Esparza, P.L.L.C. 1524 North Alamo Street San Antonio, Texas 78215 www.txmilitarylaw.com (210) 354-1919 (210) 354-1920 Fax lawofcmg@gmail.com

18th Annual Stuart Kinard Advanced DWI Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association San Antonio, Texas November 3-4, 2022

GROSS & ESPARZA, P.L.L.C.

1524 North Alamo Street San Antonio, Texas 78215 lawofcmg@gmail.com www.txmilitarylaw.com (210) 354-1919

B.A., Trinity University, San Antonio, Texas, 1984 J.D., St. Mary’s University, San Antonio, Texas, 1987

Judge Advocate, U.S. Marine Corps, 1988-1992

Associate, Zimmermann & Lavine, P.C., Houston, Texas, 1992 - 1996

Law Office of Michael C. Gross, P.C., San Antonio, Texas, 1996 - 2012

Gross & Esparza, P.L.L.C., San Antonio, Texas, 2012 - Present

Board Certified, Criminal Trial Advocacy, National Board of Trial Advocacy, 1997

Board Certified, Criminal Law, Texas Board of Legal Specialization, 1995

Board Certified, Criminal Appellate Law, Texas Board of Legal Specialization, 2011

President, Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association, 2011-2012

President, San Antonio Criminal Defense Lawyers Association, 2011-2012

Board of Disciplinary Appeals, Vice Chair 2021-present, Member 2018-present Defender of the Year, San Antonio Criminal Defense Lawyers Association, 2008

Defender of the Year, San Antonio Criminal Defense Lawyers Association, 2009

Named in Best Lawyers in America, 2005 - 2021

Named Best Lawyers 2015 San Antonio Non-White-Collar Lawyer of the Year - 2015, 2017

Named in Texas Super Lawyers in Texas Monthly Magazine, 2004 - 2021

Named Top 50 Texas Super Lawyers in Central and West Texas Region, 2010 - 2012, 2014

Named in Best Lawyers in San Antonio by Scene in San Antonio Magazine, 2004 - 2021

Named Top 10 Criminal Defense Attorneys in San Antonio by Scene Magazine - 2013 AV rated by Martindale Hubble

Supreme Court of the United States, 1991

Supreme Court of the State of Texas, 1987

United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces, 1990

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1990

United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, 1998

United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas, 1990

United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas, 1991

United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, 1991

United States District Court for the Western District of Texas, 1992

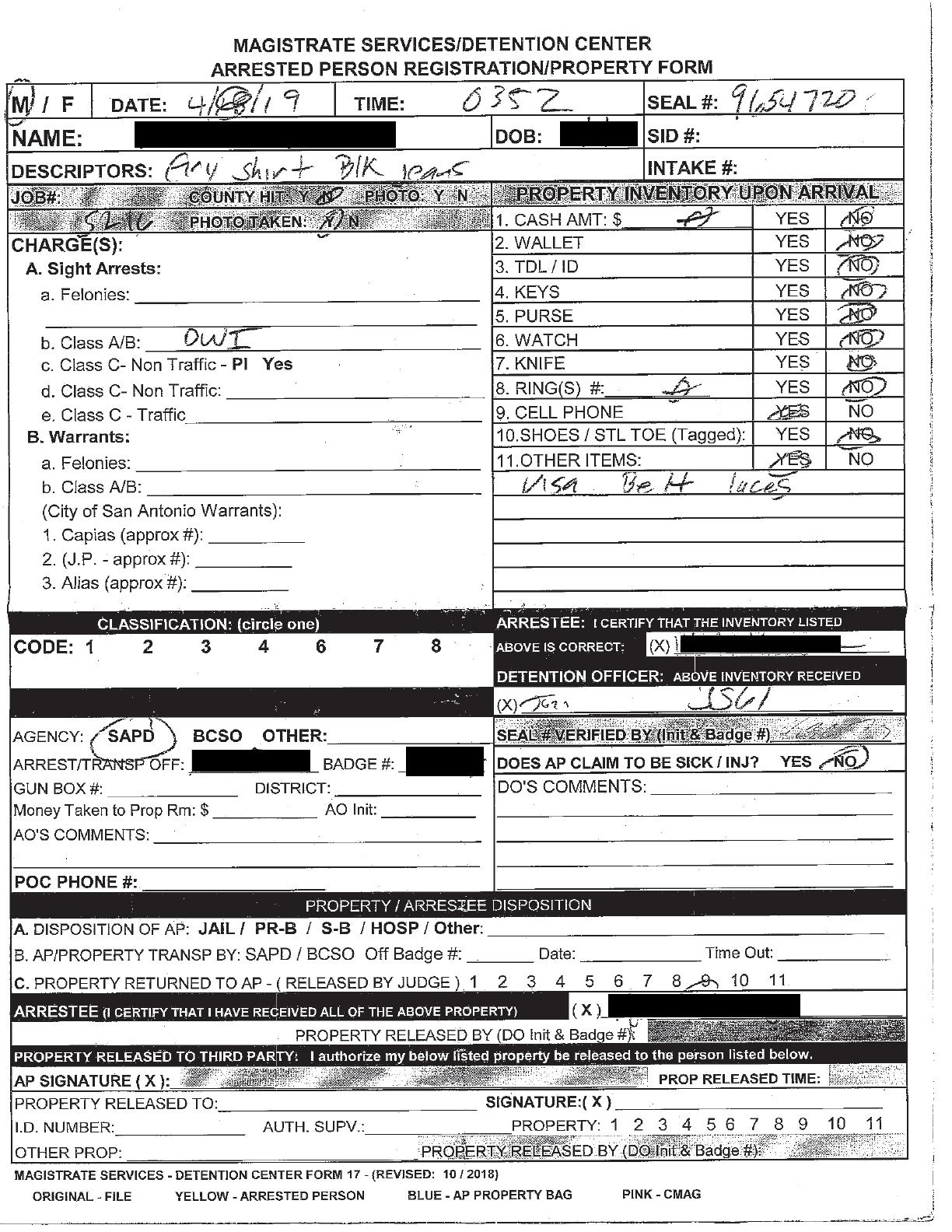

A. DWI deferred available for MB DWI after 9-1-19

B. Ignition interlock is now mandatory for DWI deferred adjudication

C. Surcharge is now a fine upon conviction .

D. Nondisclosure for DWI deferred. . . .

E. ODL supervision by pretrial services authorized . . .

1

1

1

1

F. Ignition interlock required as condition of bond if DWI with child passenger. . . . 1

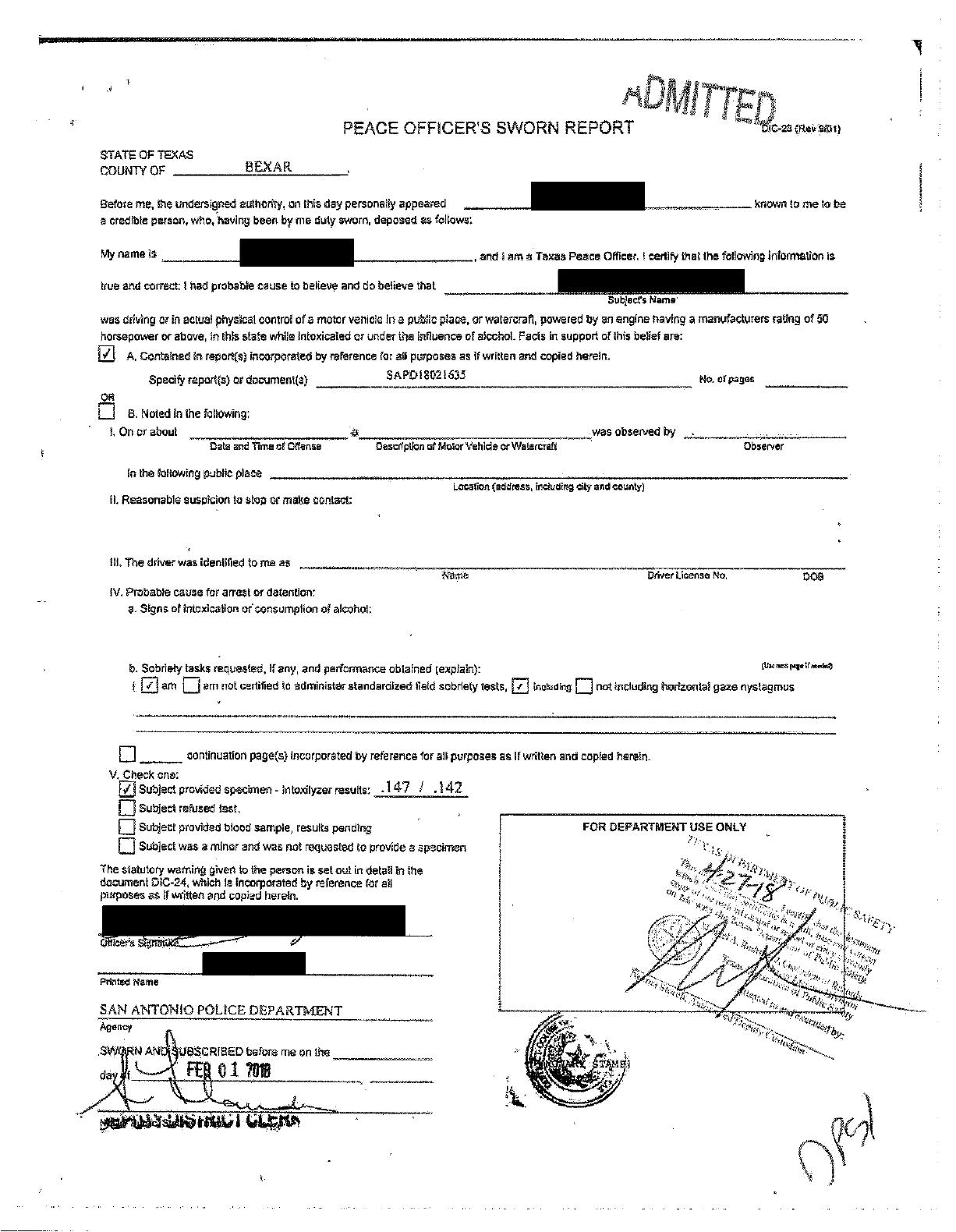

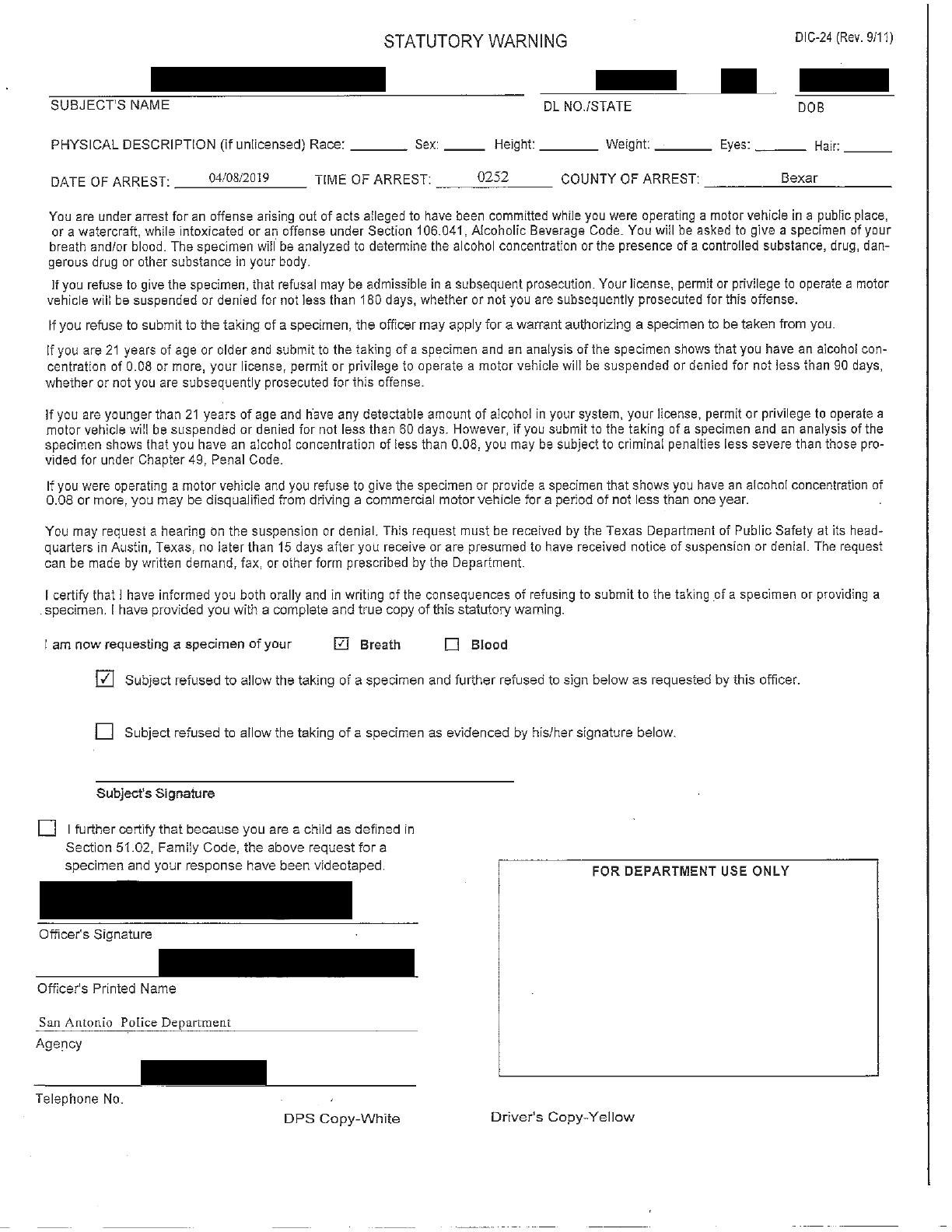

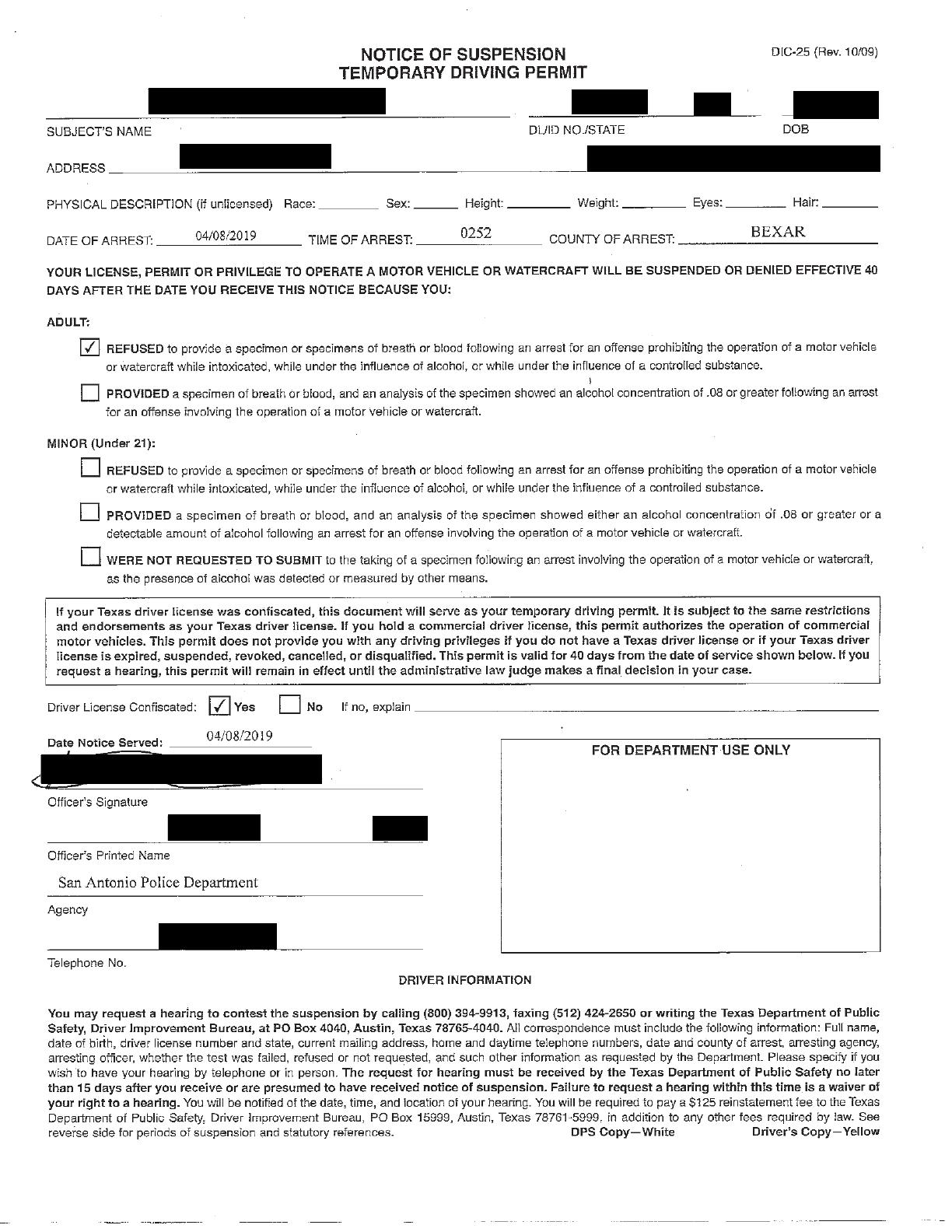

A. Littlepage and the DIC-24 statutory warning form for the hearing impaired 2

B. Turcios and typographical errors and McNeely violations at ALR level

C. Jaroszewicz and speeding error preservation at an ALR hearing .

A. Driving factors and reasonable suspicion to stop . .

1. Leming and reasonable suspicion of DWI for weaving & FMSL. .

2

3

3

3

3

Dugar and FMSL 4

Yoda and speeding 5

Reyes and reasonable suspicion for straddling two lanes

Cortez and touching the fog line is not a traffic violation

Jones and cross white line and swerve within lane is reas susp stop

Bernard and driving on lane divider is not reas susp intox .

Pritchett and stopping in crosswalk/intersection is reas susp stop

Colby and stopping in intersection for officer not reas susp stop.

.

7

8

9

Gonzalez-Gonzalez and disregarding traffic control device is reas susp 10

Rodgers and road rage is prob cause to arrest 10

Torrez and officer incorrectly thought headlight out is reas susp stop 10

Varley and one brake light out but two break lights working is reas susp 11

Speck and failure to signal in optional exit lane is reas susp stop.

Wood and cigarette tossed from car is reas susp stop for littering

Babel and no headlights on 30 minutes after sunset is reas susp

Martinez and partially obscured license plate reas susp stop

Ellis and FBI/DPS database reliable for reas susp stop

Smith and police follow directive to stop car so no reas susp

Binkley and state vehicle insurance database not reliable for stop

Oringderff and 911 call sufficient to stop.

and 911

sufficient

12

Evans and reas suspicion but no prob cause and duration of stop

22

Scott and probable cause to arrest D for traffic offenses 23

Arrington and reas susp to detain b/c cumulative knowledge PO’s 23

Villalobos and warrantless temporary detention in a suspicious place 23

Cagle and 21-minute prolonged investigation is reasonable

Kuether and custody analysis re handcuffs.

Koch and custody v. detention and Miranda

Ivey and not in custody during hospital statement

C. Reading the DIC-24 and observation periods

26

28

1. Dorr and reading obsolete DIC-24 to defendant no affect on consent 28

2. Serrano and 15-minute observation period 29

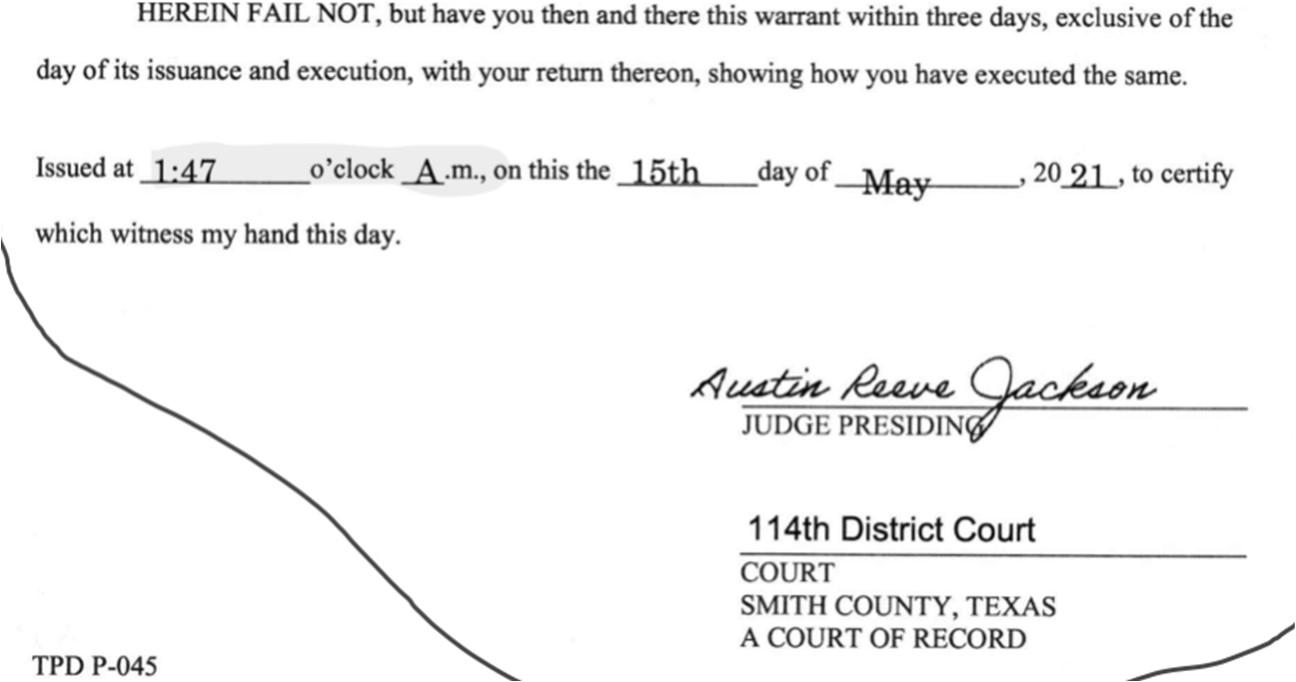

D. Blood draws without a warrant 30

1. McGruder and 724.012(b)(3)(B) re warrantless blood draw unconst. . . . 30

Mitchell and “almost always” can draw blood from unconscious driver . 30

Ruiz and can draw blood from unconscious person for exigency. . . . . . . 30

Cole and warrantless blood draw proper b/c exigency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Cosino and warrantless blood draw proper b/c exigency . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

6. Couch and warrantless blood draw improper no exigency (FOF/COL) . . 32

Weems and warrantless blood draw improper b/c no exigency 33

McGuire and warrantless blood draw improper b/c no exigency 34

Bonsignore and warrantless blood draw improper b/c no exigency 34

Sanders and warrantless blood draw improper b/c no exigency. . . . . . . . 35

Garcia and warrantless blood draw improper FOF/COL; evid destroy . . 36

Bell and warrantless blood draw improper b/c no exigency or consent . . 37

Colura and warrantless blood draw improper b/c no consent . . . . . . . . . 38

Fears and warrantless blood draw improper; delay/anger/no exigency . . 38

Perez and warrantless blood draw improper; PO’s good faith insuff 39

Molden and warrantless blood draw improper; PO’s good faith insuff 39

Hill and warrantless blood draw improper; PO’s good faith insuff 40

Swan and warrantless blood draw improper; PO’s good faith insuff . . . . 40

Roop and warrantless blood draw improper; PO’s good faith insuff . . . . 40

Kressin and officer incorrectly thought warrantless blood draw

Martinez and blood seized/tested beyond scope hospital blood draw

Hyland and warrant not required to retest blood.

Crider and

Ramirez and 2d

Davis and length of time

required to

blood

after blood seized

40

Smith and failure to get ruling on Fourth Amendment issue

Huse and the state obtaining medical records for blood & HIPPA

Trigo and right of confrontation regarding intoxilyzer results

Williams and right of confrontation regarding blood analyst

Gore and no right confrontation for blood analyst if only raw data used

Diamond and no Brady viol failure reveal analyst’s error in other case.

Rodgers and flawed felony DWI indictment

Oliva and prior DWI is not an element of DWI 2d.

Meza and must prove 0.15 at time of analysis

Ramjattansingh and 0.15 jury charge

Ashby and TFMPP admissibility

Matamoros and intoxication manslaughter and causation

Burg and must object to improper DL suspension to raise on appeal.

Rodriguez-Cruz and reversible error to deny motion continuance

Bara and double jeopardy with two children in car

Nelson and unanimity . .

Couthren and deadly weapon finding disapproved. .

Moore and deadly weapon finding approved . . . .

57

Mills and deadly weapon finding approved 58

Burnett and same transaction contextual and intox definition 59

Navarro and acquittal for MA DWI not bar to retrial for MB DWI 60

Clement and in-court HGN of D by officer; right vs self-incrimination. . 60

Strehl and lack of proof of prior DWI in felony DWI case. . . . . . . . . . . . 60

Crawford and asleep in veh and state refused stipulate to prior DWI . . . 61

Siddiq and technique of blood draw and recorded jail conversations. . . . 61

Haas and authenticity of prior DWI’s in enhanced DWI case

Corley and retrograde-extrapolation evidence was reliable

Ortiz and absence of retrograde extrapolation and guilty finding

Bowman and IAC for failure get payroll records for impeachment

Voda and speedy trial

Taylor and corpus delecti

Harrell and corpus delecti

Cabral-Tapia and no

NHTSA HGN

Screws and probation conditions in the court’s charge.

Flores-Garnica and ATV

Cook and two children in

Martinez and judge

and

motor vehicle for DWI

sponte

.

Article 42A.102 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure (TCCP) has been amended effective 9-1-19 for offenses committed after 9-1-19 to allow a judge to grant deferred adjudication for MB DWI but not for DWI with child passenger, flying while intoxicated, operating amusement ride while intoxicated, intox assault, intox manslaughter, DWI while having a CDL or CDL permit, 0.15 or higher, or punishment may be increased under PC49.09.

Article 49.09 of the TCCA has been amended effective 9-1-19 to state that a DWI deferred is treated like a conviction for enhancement purposes.

Article 42A.408 of the TCCP has been amended effective 9-1-19 to state that a judge who grants deferred adjudication for DWI shall require II on vehicle owned by D or vehicle most driven by D and prohibit D from driving vehicle without II. In indigent cases, judge may allow scheduling order for II payments or waiver of installation charge and 50% reduction of monthly monitoring fee.

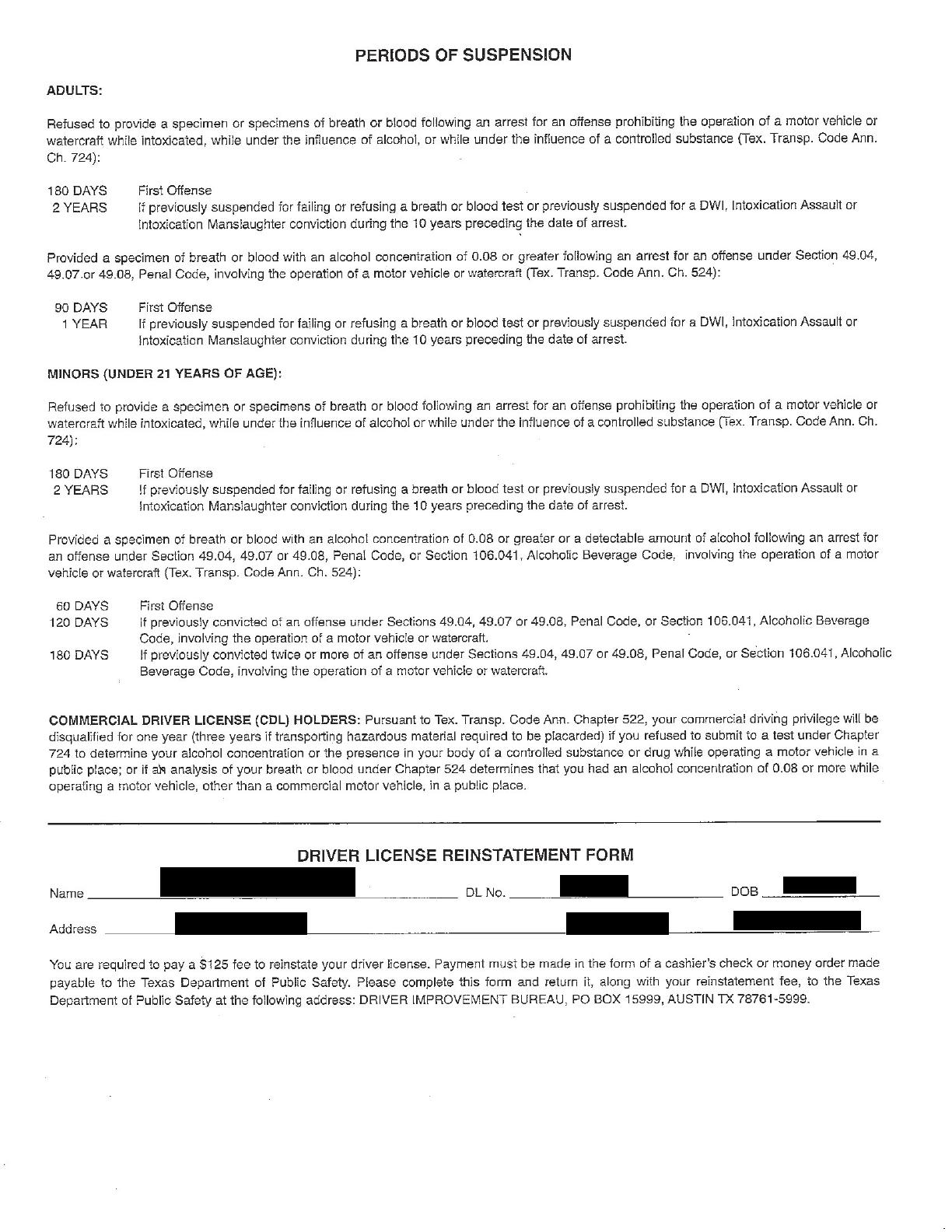

Surcharges are gone as of 9-1-19 and, pursuant to Tex. Trans. Code § 709.001, a person finally convicted for DWI type offense shall pay a fine of: (1) $3K for first conviction within 36-month period; (2) $4500 for second or subsequent conviction within 36-month period; (3) $6K for first or subsequent conviction if 0.15 or more at time of analysis.

If D produces tax return or recent wages statement or government agency proof of assistance and judge finds that D is indigent, judge shall waive all finds and costs under this section.

Tex Gov’t Code § 411 0726 allows for a nondisclosure of a DWI/BWI deferred adjudication 2-years after completion of deferred and discharge/dismissal of case if: (1) the judge did not enter a finding that nondisclosure would not be in the best interest of justice; (2) no new offenses other than a traffic offense; (3) no prior offenses other than a traffic offense; and (4) the State does not present evidence that the offense included an accident involving another person including a passenger.

Tex. Trans. Code § 521.2462 allows a judge granting an ODL to order supervision by pretrial services to ensure compliance with the ODL requirements.

Article 17.441(a) of the TCCP now requires II as a condition of bond if the DWI charge includes a child passenger.

Tex. Dep’t of Pub. Safety v. Littlepage, No. 03-14-00194-CV (Tex. App. Austin, July 8, 2016, no writ) (unpublished) - Officer at scene saw D communicating with others by texting in English on his phone. The officer decided to do the same. By texts with the officer, D admitted recently drinking a Blue Hurricane preceded by six beers. Officer also texted questions and instructions to D by writing in English on a notepad, including while administering the SFST’s. Officer structured several questions as yes-or-no choices in which D circled the correct answer. Other questions had elicited written answers from D.

Officer admitted on cross that some of these answers were difficult to understand and had unusual grammatical structure, but officer attributed this at least in part to D’s intoxication. Officer claimed D had appeared to understand and capable of communicating in written English. D did not make any request for an ASL interpreter Officer showed D DIC-24 form at least twice before transporting him to jail. Officer wrote D a note asking whether he would read the DIC-24 form, providing as before “yes” and “no” answers for him to circle and also wrote D a note explaining the statutory warnings in the form. D then became uncooperative, glanced over the form, but refusing to respond to the question posed. Instead, D then wrote he wanted a phone call and “something (un-legible) about a deaf law.”

At jail, officer again provided D a copy of the DIC-24 form. D refused to read the form and further refused to provide an answer on a portion of the form inquiring whether he was refusing the breath-sample request. Based on this conduct, officer concluded D was

refusing to provide a breath specimen and confiscated his driver’s license.

At the hearing, D emphasized the text of Section 724.015, which states that “the officer shall inform the person orally and in writing” of the statutory warnings before requesting the specimen. Because ASL is the equivalent of an oral communication for a deaf person, D argued officer failed to comply with Section 724.015.

Court stated, however, that the law requires only that a driver “was requested to submit to the taking of a specimen” and “refused to submit to the taking of a specimen on request of the officer.” The ALJ could reasonably have inferred that D was able to read and understand written English and even to communicate responsively in writing. The ALJ had a reasonable basis to infer that D’s conduct reflected D understood the nature of the request being made and the statutory warnings and refused through inaction to comply. It was sufficient that D received and could read the written warnings, and D presented no evidence to dispute the reasonable inference that D understood warnings the officer twice provided for him and the additional explanation that the officer provided.

Tex. Dep’t of Pub. Safety v. Turcios, No. 13-14-00332-CV (Tex App. - Corpus Christi, June 9, 2016, no writ) (unpublished)

ALJ suspended D’s driver’s license finding, in part, that D’s vehicle had a “non-working from headlight” and D refused a breath test rather than a blood test.

D appealed ALJ’s suspension order to county court claiming: (1) there was no evidence that his vehicle had a “non-working from headlight” as the ALJ stated; (2) there was no evidence that D refused to provide a “breath” specimen as the ALJ stated; and (3)

A. Littlepage and the DIC-24 statutory warning form for the hearing impaired

the ALJ’s decision violated McNeely.

Court held that, regardless of a typographical error “from” headlight by ALJ, the officer’s report stated D was stopped for driving with a defective “front” headlight and D admitted at ALR hearing that a headlight was out. No prejudice from ALJ misstating in FOF that D refused a breath test rather than a blood test.

No Fourth Amendment issue in an ALR hearing based on refusal to submit a blood test, because the mere suspension of a driver’s license does not implicate the driver’s expectation of privacy. The Court held that McNeely strongly suggests the Supreme Court did not intend to prohibit ALR hearings as a legal tool to enforce drunk driving laws. McNeely does not directlyaddress whether the Fourth Amendment forbids the State to administratively suspend a driver’s license for refusing a blood draw, but the plurality opinion stated such an administrative suspension based upon refusing a blood draw is a constitutionally permissible “legal tool” to further the State’s interest in preventing drunk-driving. The county court erred by finding the ALJ’s suspension order violated McNeely

Jaroszewicz v. Tex. Dep’t of Pub. Safety, No. 03-15-00340-CV (Tex. App.Austin, August 26, 2016, no writ) (unpublished) - D’s attorney at ALR hearing did not provide any basis for the objection to the challenged evidence of speeding prior to its admission other than to identify the objectionable areas of the officer’s affidavit “wherein the officer states that he is – his visual ability to determine an excessive rate of speed and also wherein he states he used radar to determine the actual speed ” Counsel also did not provide any rule of evidence or other authority to support the exclusion of this

evidence until after both parties rested and during closing arguments.

Raising the specific objections for the first time during closing argument is untimely and fails to preserve error. On appeal, D claimed evidence of vehicle’s speed clocked by radar was not admissible and that the non testifying officer’s written legal conclusion that D was speeding, without more, also was inadmissible. D claimed an absence of Kelly evidence to show officer’s knowledge and experience of the radar unit, how it operated, whether he calibrated it or knew how to calibrate it, whether he tested it or knew how to test it, or how long he had been using radar to detect speed, if ever. D claimed that without the radar results, the officer’s observation and estimate of rate of speed was a mere hunch or suspicion.

Court held that DPS is not required to show that D was actually speeding to justify the officer’s traffic stop, but only that the officer reasonably believed D was speeding.

Leming v. State, 493 S.W.3d 552 (Tex. Crim. App. 2016) - Officer (and also on dash cam video) saw Jeep traveling unusually slowly, swerving, nearly strike the curb twice, and continued to drift back and forth within its lane. This corroborated tip from caller to dispatch.

TCCA held that officer had reasonable suspicion to stop D’s vehicle to investigate the offense of FMSL even if officer could not quite tell whether D had actually entered adjacent lane because officer saw D drive on the divider stripes and several times came

close to entering the adjacent lane. Under Tex. Transp. Code Ann. § 545.060, it is an offense to fail to remain entirely within a marked lane of traffic so long as it remains practical to do so, regardless of whether the deviation from the marked lane is, under the particular circumstances, unsafe.

The TCCA held it need not decide if driving on the divider stripes constitute a failure to stay “entirely within” a designated lane because, “for a peace officer to stop a motorist to investigate a traffic infraction, as is the case with any investigative stop, ‘proof of the actual commission of the offense is not a requisite.’” The officer had an objectively reasonable basis to suspect D was intoxicated because a partially-identified informant saw vehicle swerving from side to side and the officer corroborated the observation.