1 minute read

& DAY

from TCT Europe 31.3

by TCT Magazine

componentry like batteries and computers take up a significant portion of the satellite's overall weight. But it is one they backed themselves to overcome with the combination of their engineering prowess and 3D printing technology.

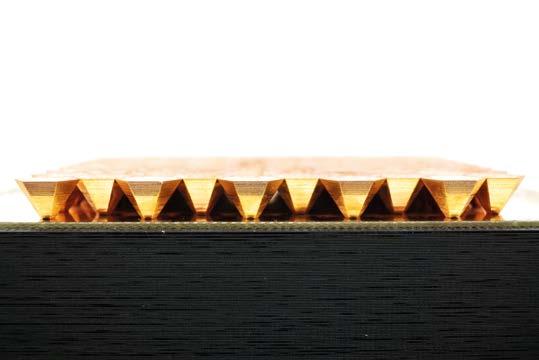

In the design of the LizzieSat, they have applied Markforged’s composite 3D printing technology to the entire structure of the 31 x 31 x 18 inch satellite, harnessing the company’s Onyx FR and Onyx FR-A materials on eight vertical and eight horizontal components that hold in place a honeycomb structure. With this use of carbon-fibre filled nylon, Sidus says it is able to leverage similar strength qualities to aluminium, while reducing the weight and iterating on designs much more quickly.

During design iteration, Boschi incorporated fastening functionality into the structural components so that parts fit into a slot and lock into place. This has not only helped to shave off weight by removing screws and bolts but has also made the satellite sturdier.

“When we started doing the preliminary analysis, you could see that when the parts were bolted together, they were all separate,” Boschi says. “But when we made the locking feature, then the entire ring became one piece, so that we’re only pulling on one structure, as opposed to 16 pieces –because there are eight columns and eight pieces in between to hold them together. Now we put everything together, they all get bolted to the honeycomb or the aluminium pan on the other side, it’s more of a stronger, stout structure.”

At the time of writing, Sidus is in ‘full print’ mode ahead of the prospective SpaceX launch later this year. The design has been locked in, the honeycomb and base plate are due for arrival in April, and then the satellite will go through an extensive testing process to prove out its durability. The LizzieSat satellite has been built for a five-year life, while Sidus has had to keep in mind that as it is launched into outer space, it will have to take 5G loads, withstand solar radiation, and deal with vast temperature swings of around 200°C as it goes from the exposure of direct sunlight to

For Boschi, he’s never been more sure that 3D printed parts can manage it. “When I first did parts years ago with SLA machines, we would break them taking them out of the machine. If you didn’t put it down right, it would break. And it’s advanced from that point forward. Now we’re in nylon. Better materials, it’s changing everything. From that point when I was first [using 3D printing], it’s night and