ALL THE SCARY HOUSES

Neighborhoods fight the giant companies pushing the shortterm rental tidal wave.

By EVA RUTH MORAVEC

By EVA RUTH MORAVEC

QUEENS DEFIANT

LGBTQ+ performers are battling Texas’ “drag ban.”

By KIT O’CONNELL

THE LAST TEXAN TO DIE

IN AFGHANISTAN

A Marine’s story reveals how the military targets Latinos.

By REYNALDO LEAÑOS JR.

TOPPLING STATUES

Getting rid of Confederate monuments won’t erase racism.

By GABRIEL ARANA

since 1954 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

By NEELANJANA BANERJEE

Short-Term

RUTH MORAVEC

RUTH MORAVEC

Death Row Reconciliation A baby’s due date and a killer’s execution date made one Texan think hard about fatherhood.

THE TEXAS OBSERVER (ISSN 0040-4519/USPS 541300), entire contents copyrighted © 2023, is published six times per year by the Texas Democracy Foundation, a 501(c)3 nonprofit foundation, PO Box 3000, Denville, NJ, 07834-9947. Telephone (512) 477-0746. Email: business@texasobserver.org. Periodicals Postage paid in Austin, TX, and at additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER Send address changes to: The Texas Observer, 54 Chicon St., Austin TX 78702. Subscriptions: 1 yr $42. Foreign, add $13 to domestic price. Back issues $10. Airmail, foreign, group, and bulk rates on request. Microfilm available from University Microfilms Intl., 300 N Zeeb Rd, Ann Arbor MI 48106. INDEXES The Texas Observer is indexed in Access: The Supplementary Index to Periodicals; Texas Index; and, for the years 1954 through 1981, The Texas Observer Index. Volume 115, No. 4.

Rental Rebellion What began as an economic boon for homeowners has spawned housing shortages and, in some cases, violence. By

CONTENTS 01 EDITOR’S LETTER 02 POLITICAL INTELLIGENCE Impeachment, Texas-style By LISE OLSEN 04 EYE ON TEXAS Why racism survives after statues fall By GABRIEL ARANA 06 THE INTERVIEW Houston author and physician Ricardo Nuila says public hospitals treat us better for less. By LISE OLSEN 08 STRANGEST STATE By TEXAS OBSERVER STAFF 38 PHOTO ESSAY The Eagle Pass Fire Department has lots of ground to cover—and smaller crews to do it with. By KAYLEE GREENLEE BEAL 46 POSTCARD Do Confederate women and children still haunt this Austin office building? By MICHELLE PITCHER 50 REVIEW Hidden Roots of White Supremacy offers a long view of our nation’s history. By DAVID BROCKMAN 52 CULTURE The “drag ban” isn’t stopping Texas queens. By KIT O’CONNELL 56 POEM West Texas Sage By CADE HUIE 20 Latinos Lured to the Military A Laredo high school graduate became a Marine, with tragic results. By REYNALDO LEAÑOS JR. 10 30 ON THE COVER: ILLUSTRATION BY DRUE WAGNER ABOVE: CHRISTOPHER LEE, SHELBY TAUBER, CHRISTOPHER LEE

EVA

INVESTIGATING TEXAS SINCE 1954

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

EDITOR- IN - CHIEF Gabriel Arana

CREATIVE DIRECTOR Ivan Armando Flores

SENIOR WRITER & EDITOR Lise Olsen

EDITOR-AT- LARGE Gayle Reaves

DIGITAL EDITOR Kit O’Connell

SENIOR WRITER & ASSISTANT EDITOR Gus Bova

SENIOR WRITER Justin Miller

STAFF WRITERS Josephine Lee (McHam Fellow), Michelle Pitcher

SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER Tyler Lewis

GUEST POETRY EDITOR Logen Cure

POETRY EDITOR EMERITUS Naomi Shihab Nye

STAFF CARTOONIST Ben Sargent

COPY EDITOR Adam Muro

FACT CHECKER Chris Collins

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Neelanjana Banjeree, David Brockman, Reynaldo Leaños Jr., & Eva Ruth Moravec

CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS

Peter Charlap & Drue Wagner

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Kaylee Greenlee Beal, Cindy Elizabeth, Christopher Lee, Shelby Tauber, & Joseph Rushmore

BUSINESS MANAGER Nikki Kobiljak

TEXAS DEMOCRACY FOUNDATION BOARD

Lize Burr (president), Peter Ravella (treasurer), Terri Burke, Carlton Carl, Mark Horvit, Kathleen McElroy, & Skye Perryman

EDITORS EMERETI: Jake Bernstein, Nate Blakeslee, Lou Dubose, Dave Mann, Bob Moser, Kaye Northcott, Karen Olsson, Geoff Rips, Andrea Valdez, & Forrest Wilder

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Michael Agresta, Asher Elbein, Alex Hannaford, Christopher Hooks, Steven G. Kellman, Robert Leleux, James McWilliams, Bill Minutaglio, Rachel Pearson, Robyn Ross, Brad Tyer, & Daniel Blue Tyx

FOUNDING EDITOR Ronnie Dugger

OUR MISSION

We will serve no group or party but will hew hard to the truth as we find it and the right as we see it. We are dedicated to the whole truth, to human values above all interests, to the rights of humankind as the foundation of democracy. We will take orders from none but our own conscience, and never will we overlook or misrepresent the truth to serve the interests of the powerful or cater to the ignoble in the human spirit.

EDITOR’S NOTE

Dear Observer Community,

Short-term rentals—for which companies like Airbnb serve as brokers—are sucking up housing inventory across Texas, driving up prices for renters and home buyers alike. For longterm residents whose neighborhoods have been taken over by tourists, there’s also the noise, trash, and parade of strangers who lack community roots.

Our cover story by Contributor Eva Ruth Moravec examines the toll on neighborhoods and how residents and cities have fought back. But any modest progress local governments have made in regulating the industry may soon fall victim to Republicans’ quest to wrest control away from cities with the recently passed “Death Star” bill.

In a collaboration with Latino USA, Contributor Reynaldo Leaños Jr. looks at the military’s efforts to recruit Latinos, which oversell the benefits and understate the risks, as enlistments dwindle. Contributor Neelanjana Banerjee tells the story of how an approaching execution changed an Indian-American family and a killer.

In our culture pages, Digital Editor Kit O’Connell explores Austin’s thriving scene as a new law limiting drag performances comes into effect. With Halloween around the corner, Michelle Pitcher ghost-hunts at an Austin office building where Confederate women and children still haunt the halls. And Senior Writer and Editor Lise Olsen previews Attorney General Ken Paxton’s upcoming impeachment trial.

Since bidding farewell to beloved Texas Observer Poetry Editor Naomi Shihab Nye, we have invited other Texas poets to help with our selection for each issue. Thanks to Guest Poetry Editor Logen Cure, who curates Inner Moonlight, a monthly reading series and podcast for The Wild Detectives venue in Dallas. Her debut poetry collection Welcome to Midland was shortlisted for the Reading the West Book Awards.

TEXASOBSERVER.ORG | 1

GABRIEL ARANA Editor-in-Chief

¡Adelante!

Gabriel Arana

CAN TEXAS SOLVE A PROBLEM LIKE KEN PAXTON?

The upcoming impeachment is guaranteed to provide a jaw-dropping spectacle of how Lone Star State politicians grapple with corruption.

by LISE OLSEN

by LISE OLSEN

The forthcoming impeachment trial of Attorney General Ken Paxton is guaranteed to provide a colorful show and a lesson on how Texans occasionally confront the corrupt through a highly anachronistic political tool. Many Americans may only recall the impeachments of U.S. Presidents Donald Trump or Bill Clinton—fraught theatrical affairs in which the House voted to impeach and a politically divided Senate then failed to convict.

But such political trials are centuries-old, having been imported by the Founding Fathers from England, where an impeachment conviction could lead to beheading for egregious rogues. Under today’s U.S. and Texas constitutions, the most dire result is simply an embarrassing spectacle and possible removal from office. No one dies or goes to jail.

Although it still seems unlikely that

Paxton, the ultimate survivor, will lose his job for good, the rules made by the Republican-dominated Texas Senate are surprisingly by-the-book—and some of the state’s top attorneys are assisting the prosecution.

As Alexander Hamilton, the same dude who centuries later inspired the hit musical, once wrote: The subjects of impeachment are “those offenses which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust. They are of a nature which may with peculiar propriety be denominated POLITICAL, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself.”

In other words: Impeachment was created to protect society from elected scoundrels.

Paxton, a former state representative and senator, stood accused of violating various laws and abusing his power well

before his first term as attorney general began in 2015. It took eight years for the House of Representatives to decide Texans needed protection from him.

In some ways, Paxton’s articles of impeachment resemble the charges in his pending state criminal case for stock fraud (a matter stalled in criminal courts) and in the allegations made in a civil lawsuit filed by ex-senior employees in the AG’s office (which is stalled in civil court after state lawmakers declined to foot the bill for a settlement).

But impeachment is entirely separate and is nothing like a criminal or civil trial. The impeachment trial, scheduled to begin in September in the Texas Senate, will be purely political by design.

The impeachment trial judge will be Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, an ultraconservative ex-radio talk show host who lacks legal training. And the trial rules are

2 | TEXAS OBSERVER POLITICAL

AUSTIN

INTELLIGENCE

The impeachment is the latest drama for Texas state government. (Shutterstock)

being written by the senators themselves.

Today’s Texans are relying partly on records from Texas’ last truly high-profile impeachment: that of Governor James “Pa” Ferguson, impeached for embezzlement in 1917. Ferguson, a colorful character, also stood accused of profiting by mixing personal and political business. (He’s also remembered for having propelled his wife “Ma” Ferguson into the governorship after the Senate removed him and barred him from running again.)

Ferguson appealed his impeachment to the courts, which upheld the Texas Senate’s decision and underscored its authority. Essentially, the Senate “becomes a court and continues as such regardless of legislative sessions.”

In some ways, the Texas Constitution is stronger than the feds’. An impeachment vote here results in immediate suspension from office, so Paxton was ousted in May after house members voted 121-23 to approve 20 different impeachment articles.

But Texas senators serve both as rule-makers and as jurors in Paxton’s case. They must decide whether he’s guilty of any of the allegations and, if so, whether his exile from office should be permanent. If the Senate does vote to convict, they could also ban Paxton from holding other Texas public offices—though such a decision might favor the political fortunes of Paxton’s wife, state Senator Angela Paxton, as they did for Ma Ferguson, who became Texas’ first female governor.

For Paxton, who served in the Legislature’s upper chamber until 2015, a trial by the Texas Senate means a trial by his former colleagues and his wife’s

current ones.

In typical civil or criminal court cases, prospective jurors can be struck from any panel for conflicts of interest—but not in the Paxton impeachment. Paxton’s wife has been excluded from voting. But senators have not barred state Senator Donna Campbell, who once employed a woman who’s been identified as Paxton’s mistress and who was supposedly given another job as a favor to Paxton by his developer friend, Nate Paul. Nor have they barred state Senator Bryan Hughes, an ally, former roommate, and ex-tenant of Paxton’s.

In order to win a conviction, the lawyers who will be presenting the case for impeachment, including Houston celebrity criminal defense attorneys Rusty Hardin and Dick DeGuerin, will have to convince twice as many people as in a standard courtroom’s 12-member jury.

Hardin, a former state prosecutor, is famous for successfully defending celebrity clients like Major League Baseball pitcher Roger Clemens, once accused in a high-profile report of using performance-enhancing drugs. DeGuerin, among other things, is renowned (in cynical legal circles at least) for having convinced a Galveston jury to acquit millionaire Robert Durst after Durst killed and cut up his neighbor.

These two, working together for the first time, must convince two-thirds of the majority-Republican senate.

This will be only the third impeachment in Texas history. At the federal level, there have been only 21 impeachments, mostly of federal judges. Curiously, both Hardin

and DeGuerin were peripherally involved in the impeachment of Samuel B. Kent, once the lone U.S. district judge in Galveston. Kent enjoys particular infamy as the first and only federal judge to be impeached for sex crimes on June 9, 2009.

Like Paxton, Kent stood accused of a pattern of abuse of power that had endured for years. Like Paxton, Kent—who called himself “King Kent”—had been accused of retaliating against employees. The allegations that eventually brought down Kent were that he sexually assaulted female staff members, then lied to investigators.

In that matter, DeGuerin and Hardin stood on opposite sides: DeGuerin was the judge’s criminal defense attorney and Hardin represented Cathy McBroom, the whistleblower who accused the judge of sexually assaulting her. By the time Kent was impeached by the U.S. House, he’d already been criminally convicted of perjury and imprisoned. Only after being impeached did he resign, avoiding a U.S. Senate trial.

In contrast, Paxton has successfully stonewalled his state criminal charges, avoided federal prosecution, and steadfastly denied wrongdoing. Indeed, he has profited by using allegations against him as an opportunity to stockpile campaign cash.

Like Pa Ferguson before him, Paxton will stand and fight.

And there’s another curious link in Paxton’s case to the disgraced “King Kent.” One attorney Paxton chose as his ally in his upcoming impeachment trial is Anthony Buzbee, a powerful Houston trial attorney, who got his start as Kent’s former law clerk.

LOON STAR STATE

TEXASOBSERVER.ORG | 3

BEN SARGENT’S

DARK HISTORY

Once we take down Confederate statues, Texans must still grapple with monsters in the past.

By GABRIEL ARANA

My great-grandfather, José-María Arana, was a racist.

After the United States barred Chinese men from immigrating under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, tens of thousands sought a new life in Mexico, where they faced no warmer a welcome as they established themselves. A former schoolteacher and businessman, José-María led a vicious campaign against the Chinese in the Mexican states of Sonora, Sinaloa, and Baja California in the early 1900s.

Seeking “all legal means to eliminate the Asian merchant,” whose growing prosperity he viewed as a threat to the working class and Mexican national identity, José-María formed a junta of local businessmen in 1912 to address what he called “the tremendous calamity of the Chinese jaundice.” He launched a newspaper, Pro-Patria, whose masthead boldly proclaimed, “Mexico for the Mexicans and China for the Chinese.” Featuring racist jokes and caricatures, the broadsheet portrayed Chinese immigrants as carriers of disease and a threat to Mexican women.

“We cannot live together because there exists an absolute incompatibility in race, social customs, and economy,” José-María wrote in its pages.

My great-grandfather carried his message throughout Northern Mexico, making speeches in working-class towns like Cananea—whose poor copper miners he thought ripe for radicalization—and urging city and state leaders to restrict

the types of businesses that Chinese immigrants could run, relegate them to ghettos, and expel them de manera definitiva [in a definitive way].

I’ve thought increasingly about my great-grandfather and his ignoble legacy as I’ve settled into life in Texas, where the Confederate cause is memorialized on statues, flags, and street signs. Growing up on the U.S.-Mexico border in Nogales, Arizona—where José-María’s widow, my great-grandmother, settled after his death in 1921—I knew little about my family tree’s racist roots. Like a lot of gay kids who come from a small town, I left to find people like me in bigger cities and only much later started to contemplate my origins.

A few months after moving here in the summer of 2022, I visited the Capitol grounds with my in-laws from London. The Texas State Capitol is an imposing Renaissance revival structure made of pink granite with a dome that, Texans remind you, is taller than the U.S. Capitol. But what impressed us all the most on that first visit was the enormous Confederate Soldiers Monument on the right as one walks up to the entrance from 11th Street.

A bronze statue of Confederate President Jefferson Davis stands atop one of five pillars. The other four support figures representing the branches of the Confederate military. The inscription on the pedestal below commemorates the 437,000 soldiers who

“died for states [sic] rights guaranteed under the Constitution” and asserts that “the People of the South, animated by the spirit of 1776, to preserve their rights, withdrew from the federal compact.”

“It’s Texas,” I said preemptively, feeling defensive and embarrassed at the same time as my in-laws looked on in horror. It’s the same way I feel when an outsider mentions the state’s abortion ban or attacks on LGBTQ+ people.

The Confederate Soldiers Monument is one of 12 memorials on the grounds that perpetuate the “lost cause”—the historical myth that the Confederate cause was heroic and not about slavery.

It is a lie easily debunked by looking at Texas’ Ordinance of Succession, which laid out the state’s own reasoning for withdrawing from the union. The document declares that Blacks were “rightfully held and regarded as an inferior and dependent race” and that “the servitude of the African race … is mutually beneficial to both bond and free” as well as ordained by God. Even the monument’s Confederate death count, scholars have pointed out, is inflated.

The endurance of the Confederate cult here does not, of course, reflect the prejudices of most Texans, which is what makes these symbols so corrosive to a shared sense of state identity. An implicit endorsement of white supremacy, they most directly exclude Black Texans, whose struggle for freedom offers a far more

4 | TEXAS OBSERVER EYE ON TEXAS FORT WORTH

edifying narrative to rally around—one that embodies our national values and unity rather than doubling down on a lost war. But they set up an identity conflict for anyone of good conscience who wants to claim Texas as their own: Every assertion of Texas identity must come with a “but.”

Reminders of the Confederacy abound here in Austin, considered the state’s bluest city: In the Texas State Cemetery, civil rights hero and Congresswoman Barbara Jordan and former Governor Ann Richards lie yards away from Albert Sidney Johnston, a slave owner and Confederate general whose Gothic tomb looks out on the Confederate Fields on the cemetery’s southeast side, where 2,200 Confederate veterans are interred, each plot marked by a white cross.

Some of my Southern friends have said that when you grow up in the South, the paraphernalia is so commonplace, it can blur into the background. But if you’re new to it, it’s striking to see the resentments of the 1800s enshrined in what are supposed to be shared expressions of our civic ideals.

It was perhaps easier to dismiss them before the Obama and Trump presidencies brought the Nazis and white, Christian nationalists out of the woodwork, when it was at least a bit more plausible to reassure oneself that “America is getting better.” It’s become harder to think of racism as a healing wound on the body politic when white nationalists demonstrate openly in public and Republicans in the Legislature try to ensure K-12 students only get taught a sanitized fairy tale about Texas history.

“Most Texans do not support erasing our history … out of political correctness,” Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick wrote in an August 2022 letter to Senate Democrats who had urged the Legislature to remove Confederate monuments on the Capitol grounds.

The irony is that whitewashing Texas history is the very purpose of Confederate propaganda—and the impetus behind state Republicans’ attacks on education. Last year, Governor Greg Abbott signed a law that limits how K-12 teachers can talk about racism and slavery; it bans educators from discussing the New York Times’ 1619 Project, which reframes the nation’s founding as inextricably linked to

the arrival of slaves on American shores in 1619.

Since the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, and the George Floyd protests in 2020, some Texans have begun to change their minds about memorializing the Confederacy. While a bare majority once opposed their removal, now 52 percent say they should be taken out of public view or relocated to museums where they can teach us about the past rather than help keep its prejudices alive.

Amid our national reckoning about race, reminders of the Confederacy have started

nine monuments, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.

My great-grandfather has no monuments dedicated to him, nor do I think he deserves any. What he represents is too corrosive to memorialize.

I don’t have trouble condemning JoséMaría as racist and acknowledging the harm he caused the Chinese community in Northern Mexico. I have come to take a qualified pride in my Mexican heritage, but to the extent it is synonymous with the racism José-María espoused, I must condemn it. Being members of a pluralistic society requires us to put our civic ideals, like the belief in human equality, above allegiance to our ancestry.

I never heard about José-María as a kid. My grandparents died when I was young, and my father never spoke of him. One Christmas when I was home, I happened upon a collection of my grandfather’s writing about our family history. His father, he wrote, had been mayor of Magdalena, Sonora, and his papers were preserved in a collection at the University of Arizona.

I looked up the collection online, which featured speeches, newspaper clippings, and correspondence, including hate mail from Chinese Sonorans. A quick trip to Google Scholar filled in his biography.

to come down in Texas. In 2017, the Texas State Preservation Board voted to remove the Children of the Confederacy plaque, which proclaimed that “the War Between the States was not a rebellion, nor was its underlying cause to sustain slavery,” from the Capitol. The University of Texas at Austin relocated four Confederate statues on its campus in 2015 and 2017. But this only scratches the surface: Statewide, only 34 of 240 Confederate symbols have been removed, including

José-María was indeed elected mayor of Magdalena in 1919 after running twice, his first campaign derailed by a stint in prison for inciting violence against Chinese immigrants. As mayor, he was only able to pass laws taxing Chinese businesses, but his advocacy helped inspire the Sonoran legislature to relegate Chinese immigrants to ghettos and expel them in 1919—a move later overruled by the federal government. He died in 1921, supposedly from being poisoned, after which his widow moved to Arizona with my grandfather, where the family was reduced to poverty.

Though I think it is good to have learned about the monster in my bloodline, I’m glad that ultimately, his name will only exist only for those who want to discover it. That’s where I think my great-grandfather’s shameful legacy belongs—in the historical record, the subject of debate and reflection about the mistakes of our ancestors, as a warning of what happens when one is too proud of one’s identity.

TEXASOBSERVER.ORG | 5

IT’S BECOME HARDER TO THINK OF RACISM AS A HEALING WOUND ON THE BODY POLITIC WHEN WHITE NATIONALISTS DEMONSTRATE OPENLY IN THE STREETS.

THE PEOPLE’S DOCTOR

Physician and Author Ricardo Nuila thinks public hospitals could help save patients trapped in our troubled medical system.

INTERVIEW BY LISE OLSEN

Ricardo Nuila is a third-generation physician at Ben Taub Hospital, a busy public facility operated by Harris Health in the Texas Medical Center. An internal medicine specialist, he’s part of a staff dominated by residents and graduates of Baylor College of Medicine. And in his spare time, he writes. His compelling essays and new book, The People’s Hospital: Hope and Peril in American Medicine (Simon and Schuster, 2023), focus on how many people get stranded in healthcare limbo—or needlessly lose their limbs or lives—in America’s cumbersome and costly healthcare system because of uncontrolled costs, overbilling, and greed promoted by health insurance companies and for-profit hospitals. Nuila thinks a good public hospital network across America could outperform even the most expensive private alternatives. He spoke to the Texas Observer about why.

You became a doctor partly through your roots: Your father is an OB-GYN and your grandfather is a physician in El Salvador. Why are you drawn to tell patients’ stories?

I just knew that these stories had not been told before. And also, just gut feelings. Being on the wards with patients and being like—whoa!—I can’t believe this person’s going through this. Their odyssey sticks with you. And there came a realization: Well, if I’m shocked, everybody will be shocked by this. … I just want to artistically render the stories of patients going through what they do and what their medical odysseys say about life or about the world. This book certainly did not start off as a treatise on healthcare!

Your book recounts gripping tales of five patients who face life-and-death struggles without insurance: Roxana, a former Saks salesperson who has limbs

that are literally rotting off, but she can’t afford treatment; Stephen, a conservative former restaurant manager saddled with massive cancer-related bills; Ebonie, who nearly dies in childbirth after moving to Texas from California; Christian, a young man who can’t find anyone to diagnose mysterious debilitating health problems; and finally Geronimo, a man who loses coverage because he worked. Why did you choose them?

Roxana—she and I connected immediately. She was from El Salvador and given the drama she had to go through, she was forced to demonstrate her specialness. She was very resilient and inspiring. She remained graceful despite those dead limbs.

Stephen’s story I could write from talking with him, though he looks at life in one way and I have different views. This book is not meant to preach to the choir—I don’t want to write only for liberals. It’s literally written to exist in the middle

to see how we can take steps forward in healthcare. He was trying to do everything self-pay. Christian’s story came about because of all these twists and turns in his journey.

Ebonie was more obvious— we know that maternal death is a huge problem. … Her story was about what somebody who’s at high risk has to deal with in Texas.

Geronimo got his Medicaid taken away from him because of a few bucks. It ranked my injustice bone. He was my own age and that was another, “If I’m shocked by this, I need to write something about it!”

You write of Jan de Hartog, who prompted Harris County voters to fund a better public healthcare system by writing a book-length exposé called The Hospital in 1963 that “alerted the city to the deplorable state of its safety-net hospital.” Your book argues that today, Ben Taub, a huge public hospital and major trauma center, saves many more patients’ lives than its

6 | TEXAS OBSERVER THE INTERVIEW AUSTIN

pricey Texas Medical Center competitors. Why?

There was a dirty secret going around. It was just that everybody who staffs Ben Taub is a Baylor College of Medicine doctor. … And it’s crazy, but we feel that the care is better here at Ben Taub than at the nice, fancy hospitals. And to me that was an interesting intellectual pursuit: Why is it that we think this public hospital is better than private hospitals? And why is it that me and my colleagues only want to work here, and why do we love it?

Yet you describe Texas as

“quite possibly the most restrictive healthcare environment for the poor in the country” and as a place where maternal healthcare remains dismal—and has gotten worse since the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. Are you worried doctors will flee?

There’s so much pressure on the medical personnel who are very caring and who are tasked to care for women in precarious situations. The pressures have been ramped up because one way to make sure women’s health was guaranteed has just been taken away. It does weigh

on me as an internal medicine doctor, especially thinking about my OB-GYN colleagues.

You called COVID-19 “an invader” that made things immeasurably worse. Even after the pandemic waned, waves of new patients still arrived at Ben Taub after losing jobs and insurance, right?

It’s an enormous challenge because COVID has really made the labor markets very volatile, and since, in America, we peg health insurance to that, [and insurance] is gone. That means we are extremely busy as the safety net hospital. And then inflation has also made it so that the cost of healthcare grew so much that people can’t afford it.

No spoilers here by sharing how your patients’ sagas turn out. But you reveal some of your own struggles after a revered mentor of yours committed suicide during the pandemic.

It was a very difficult situation. … He was my closest friend in the hospital and he was my boss and mentor. We could all see ourselves growing into him because he had this idealism [mixed] with pragmatism. He was a doctor who wanted to care for people, but he also had been an administrator. He wasn’t a zealot. He was there to do medicine for people who needed it.

It was so sudden—and it was at a time when there was this existential dread. I think a lot of us wondered if that could become us.

I think suicide is so complex, but I felt that what he was seeing on a daily basis was what I was seeing. … It’s also just an

unmasking of just how vulnerable the profession could be.

You strongly criticize private insurers and nonprofit hospitals that overcharge and perform unnecessary tests or get lots of tax breaks but do comparatively little for the poor—like the one that claims in ads to erase cancer. Although you don’t name these hospitals, they’re recognizable. Have you gotten pushback?

In an event at the Baker Institute, someone got up and said, “You talk about all the private hospitals—what about the insurance companies?” I wondered if he had read the book, because I go off on the insurance companies, too. We found out later he was an administrator at a private hospital. But I have not gotten huge pushback, and that’s been kind of interesting. The wave could be coming.

I’m scared there’s not more pushback. It might just mean that people are entrenched and this isn’t going to change. … There are such clear incentives and there’s so much money behind these institutions, that it’s hard to fathom that the lobbyists will go away or anything like that.

We need to look back to the 1960s in Houston, when the people voted for public support of a hospital that became a successful public healthcare system.

We should combat the stranglehold of “Medicine, Inc.,” as I call it. We need a public healthcare system that competes with it.

TEXASOBSERVER.ORG | 7 This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The “shocking” predicaments of patients ensnared in the healthcare system inspired Ricardo Nuila to write The People’s Hospital.

(Courtesy Jonas Mohr)

STRANGEST STATE

SANGER

Weather has been really weird with heat waves, hail, Saharan dust, and Canadian smoke swirling everywhere. Suddenly, the National Weather Service predicted hail as big as DVDs would hit Texas. And voilà: In Sanger, chunks of ice as large as 6 inches in diameter fell from the sky. One Texas TV station received photos from viewers who collected ice balls bigger than golf balls, tennis balls, and even that summer treat: a ripe tomato.

RICHMOND

It looked like yet another attack on Texas public education when a 5-foot-long alligator wandered to the sidewalk of a Richmond elementary school. School leaders responded rapidly to this threat. “The rumors are true. We had to turn away a visitor from registration this morning,” one posted on social media. A local game warden responded, jumped on the beast’s back, and hauled it away.

FORT WORTH

Texans head for spring-fed rivers or hide out in air-conditioned homes and cooling centers during heat waves. But what do animals do? At the Fort Worth Zoo, tigers, lions, and primates play with huge ice cubes, and elephants and gorillas cavort in sprinklers. “Just like humans,” a Zoo spokesperson told the Guardian, “we’ve all kind of adjusted.”

8 | TEXAS OBSERVER

NOTES FROM

ILLUSTRATIONS: DRUE WAGNER

FAR-FLUNG TEXAS by TEXAS OBSERVER STAFF

Lize Burr & Chris Hyams

Lynne Dobson & Greg Wooldridge

Dale Linebarger

The McHam Project

The Rapoport Family Foundation

Alec Rhodes

Carlton Carl

Paul & Marian Cones

Vincent LoVoi

John Parten Winkler Family Foundation

Gabriel Arana & Michael Collis

H.L. Bryan

Zeph Capo

Kate Donaho

Robert Frump Headliners Foundation

Laura Hernandez

Carrie James

THIS ISSUE OF THE TEXAS OBSERVER IS POSSIBLE DUE THE GENEROSITY OF OUR COMMUNITY OF SUPPORTERS AND READERS.

We are grateful to our more than 7,000 members, the more than 5,000 individuals who gave to the Save the Texas Observer GoFundMe campaign, and the 50,000 readers of our newsletter. Additionally, we would like to thank the following individuals and foundations for their support of the Texas Observer over the past 12 months.

Kathleen McElroy

Ronald Moore

Rene & Jimmy Wisch Memorial Fund

Margaret & Robert Ayers

James Canup

Andy Carson

Joan Cheever

Lois Chiles

Debra Danburg & Randy Chapman

Jo Didner & J. Michael Hershey

Thomas Doneker

Edgemon Family Foundation

Yodo Faulk

Cindy Fisher & Mike Kanin

Noble G Fortson

Gil Glover

Tom Griebel

Donna Bolding Hamilton

Noah & Brittany

Kyle Hawley

Charlotte Herzele

Kelly Inselmann

Mr. & Mrs. I.H. Kempner III

L.U. Kint, Jr.

Darlene Lanham

Dick Lavine

Lifshutz Foundation

Susan Longley

Cari Marshall

MFI Foundation

Stewart R Mott Foundation

Elliott Naishtat

Jim Phillips

Barbara Ann Radnofsky

Peter Ravella

Jill Runyon

Martha Claire Tompkins

Retta van Auken

James Wieck

Mark Winkelman

The following individuals gave to the Observer in memory of the late Larry Sauer. We are grateful for their support, and to Larry and his wife, Judy Doran.

Becky Beaver, Jennifer Bradley, Katherine Butler, Carlton Carl, David Cunningham, Eric H. Nelson, Daniel R. Richards, Ann J. Robinson & GregGladden, Texas Appleseed, Diane C. Van Helden, Steve Vandegrift

Additonal support by:

Our generous supporters listed above believe, as we do, that a free press is imperative for a functioning society, and that the Observer is a critical component of that. If you feel the same and are interested in giving $ 500 or more annually, or would like to learn more about our Free Press Circle, which gives donors the opportunity to provide the Observer strategic, stable funding with a three-year commitment pledge, email business@ texasobserver.org.

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023 ALL THE SCARY HOUSES Neighborhoods fight the giant companies pushing the shortterm rental tidal wave. By EVA RUTH MORAVEC THE LAST TEXAN TO DIE IN AFGHANISTAN A Marine’s story reveals about how the military targets Latinos. By REYNALDO LEAÑOS JR. QUEENS DEFIANT LGBTQ+ performers are battling Texas’ “drag ban.” By KIT O’CONNELL TOPPLING STATUES Getting rid of Confederate monuments won’t erase racism. By GABRIEL ARANA

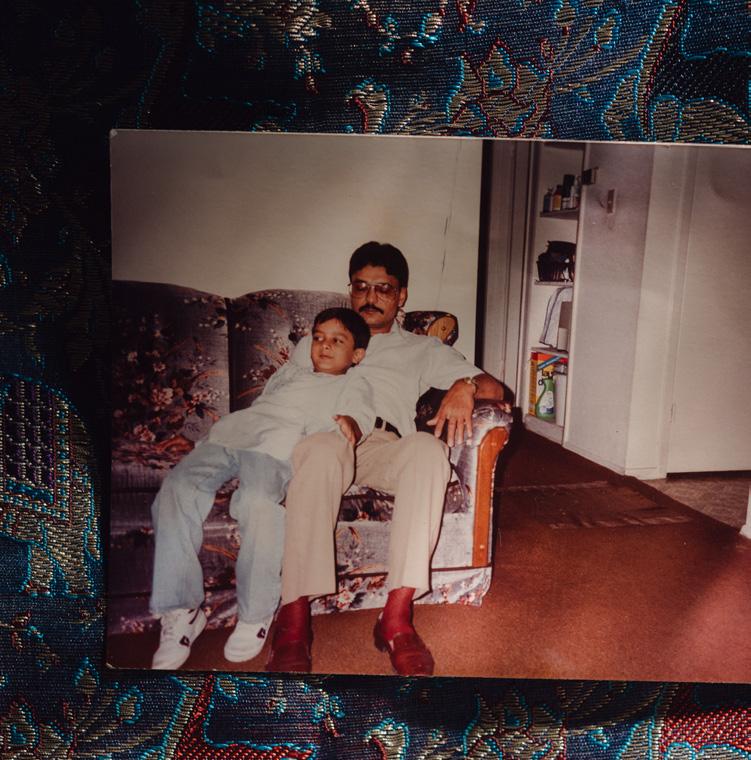

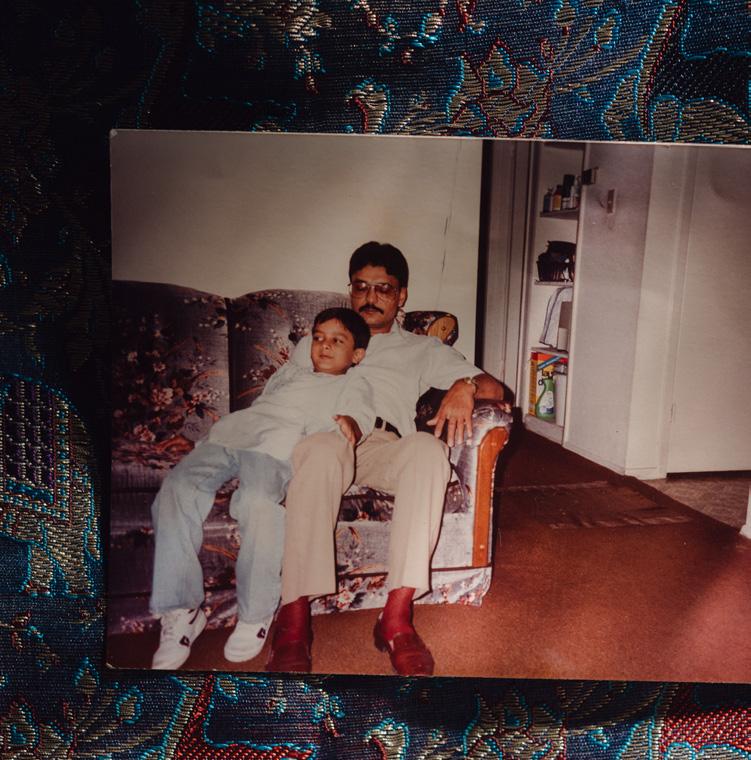

BETWEEN TWO DEATHS: HOPE FOR THE FUTURE

A MURDER AND AN EXECUTION DATE CHANGED THOSE ON BOTH SIDES OF THE BARS.

By NEELANJANA BANERJEE

Hasmukh Patel built a life around his store and was killed there in 2004.

Photography by CHRISTOPHER LEE

Hasmukh Patel built a life around his store and was killed there in 2004.

Photography by CHRISTOPHER LEE

t was a busy day for Mitesh Patel and his wife Shweta in May 2018. Both 36, they were working from their home office in the Alamo Heights suburb of San Antonio while their two sons were at school and daycare. Shweta, a financial manager for a major medical group, was on a call. Mitesh, who managed assisted living facilities, was going over administrative reports.

Then Mitesh opened the email he’d been waiting 14 years for, from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ): An execution date had been set for Christopher Young, the man who killed Mitesh’s father. Hasmukh “Hash” Patel was fatally shot in 2004 at the family’s convenience store in Southeast San Antonio.

That email “felt like a sense of closure, a sense of relief for my family,” Mitesh said.

He read over the attachments to the email and told Shweta what he had said many times: He planned to attend the execution. Then he walked down the hall to tell his mother, who had lived with them since 2007.

Shweta remembers standing up to stretch at that moment. She was seven months pregnant with their third child, and it had become increasingly difficult to sit for a full day of work. It struck her that her due date was around the same time that Young was to be executed. She thought again of the message that had been hand-delivered by two men a few weeks earlier, from Young himself to Mitesh and his family. She wondered if it could possibly change her husband’s mind.

The execution date was two months away.

The facts about Texas’ death penalty are well-documented and, in many parts of the world, infamous. The state has executed 577 people since 1976. What is less well known is that, once appeals have been exhausted and an execution date is set, the inmate’s lawyer can petition for clemency—a longshot attempt to reduce a defendant’s sentence, usually to life without parole. The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles votes on the petition, then sends its recommendation to the governor. Few requests are granted.

A motley crew of people decided to try to stop Christopher Young’s execution. This is the story of that case—of a murder, a death penalty, and how the progress

toward execution changed both the killer and the family of the man he killed.

Hasmukh Patel arrived in the United States in 1976, sponsored by his sister’s husband in Pennsylvania under a preference system for immigrants with needed skills and family ties in the United States. Raised in a family of farmers in Gujarat, India, he went to college, earned a bachelor’s degree in engineering and, in the 1970s, began fielding job offers from various countries.

His family arranged for him to marry the sister of his brother’s wife in 1975. Mina was seven years younger, a slight, smiling woman with glasses. They had a year together before he left for the United States, a time Mina remembers with pleasure: Hasmukh taking her to movies, ordering delivered meals instead of requiring his young wife to cook. Before he left, their first child, a daughter, was born. “I enjoyed that time in my life,” Mina said with a sigh.

In the United States, Hasmukh started working right away rather than continuing his education so he could send money home. His wife and daughter needed support, and his family had paid for a new water well that came in dry. He got a job flipping burgers at a Roy Rogers fast-food outlet for $2 an hour. His willingness to do whatever it took to support his family is something they remember.

Mina joined him in Pennsylvania a few months later, leaving their daughter with relatives temporarily. She, too, went to work right away, first in a sewing factory and later at other blue-collar jobs. For her, America was about working hard but also about being by her husband’s side. In 1981, a college friend invited Hasmukh to move to Houston for a job designing fire protection systems. Their daughter Rinal came to the United States that year, and Mitesh was born in 1982.

Hasmukh spent eight years in fire protection but never really found his niche. So, as other Gujarati Americans have done, he founded a small business. In 1988, he moved the family to San Antonio, where friends helped him lease a shuttered gas station in the southeast part of town.

Mitesh, then 6, remembers the

move— the borrowed cargo van, the eerie red glow over the empty gas station’s exit sign. With the help of family and friends, Hasmukh built a successful convenience store and dry-cleaning business there.

That store was young Mitesh’s universe. For 16 years, his parents were its main employees. If he or his sister were sick, his parents made them a bed under the front counter. The family moved into a twobedroom apartment nearby, and both sets of grandparents joined them there from India shortly after.

“We lived with eight people in that apartment for years” before moving to a nearby home, Mitesh recalled. They had one car, a 1970 Buick Skylark that his father bought for $500. But Mitesh said that, as a kid, he never felt any sense of financial struggle, even when his father went through a series of layoffs before buying the store. Hasmukh never shared such worries with his family.

Mina would get the kids to school and then report to the store, working until it was time to pick them up. She learned to run the cash register and improved her English by talking with customers. For the first several years, the Patels were the area’s only Indian-American family, and they and their store were well known. Today, Texas has the second-largest IndianAmerican population of any U.S. state.

In Houston, Hasmukh and Mina had helped build a Swaminarayan Hindu temple, and they did the same thing in San Antonio. When the temple moved to an old church building, Hasmukh worked on the plumbing or in the garden— whatever was needed.

In the meantime, the neighborhood around the store was slowly changing, and so the store changed as well, selling more rolling papers than packs of cigarettes. There were some robberies, mostly kids trying to steal beer.

Mitesh began to resent his father’s 14-hours-a-day, seven-days-a-week work schedule and that so many of his own weekends were spent running store-related errands. When Mitesh intentionally failed three classes in high school, Hasmukh opened up to him about his own struggles, encouraging him to create something of his own. Eventually, he inspired Mitesh to become the businessman he is today. “I felt

12 | TEXAS OBSERVER I

like he transitioned from being my dad to really becoming my best friend,” Mitesh said.

Hash, as his customers called him, was known for his generosity. If a customer came up short, Hash would often front them the money. Among the customers who benefited from Hash’s help were Christopher Young and his girlfriend. Mina advanced money to Young’s girlfriend for diapers for the couple’s baby. However, one day Hash and Young’s girlfriend got into an argument.

The next day was Sunday, November 21, 2004. Mina, on her way to the temple, detoured to bring chai to her husband. She remembers that he looked like a light was shining on him. “I could see his brightness,” she said. He had followed her to the car when a regular customer came by for a lottery ticket. “Today, my wife is first, then you,” he joked with the customer.

After Mina left, Young arrived, driving a stolen car. He had been drinking heavily the night before, and his girlfriend told him Hasmukh had disrespected her.

At the store, Young was angry and aggressive. When Hasmukh reached for the

alarm button under the counter to call 911, Young shot him twice, killing him. Young left and was arrested later that day.

Mina heard the news, returned to the store, and fainted. Mitesh was living in Houston with his sister. They got to San Antonio as fast as they could.

Hundreds of people came to the funeral: Indian-American community members, dozens of customers. It was overwhelming for Mitesh; the Hindu rituals of touching the body before it was cremated drove home that his father was really gone. Mitesh couldn’t speak. He let his sister do the talking that day.

When Young killed Hasmukh Patel in a drunken haze, he arguably prolonged his own life. At 21, he was a self-professed “knucklehead” who’d grown up in poverty. A mental health evaluation diagnosed him with PTSD from major childhood trauma.

His mother had two children— Christopher was her second—before she

was 18. She broke up with Christopher’s father, Willard Young, then moved the kids to Wisconsin, married again and divorced, and moved back to Texas after breaking up with yet another boyfriend. It was later discovered that one of her former partners had raped Christopher’s sister and another had abused Christopher. Being back in San Antonio meant Christopher got to spend time with his father—but not for long. In 1991, Willard Young was shot and killed, allegedly in a drug deal connected to his gang affiliation. Christopher was 8.

After that, Christopher “really lost his way,” said his aunt, Valerie Harris, Willard’s sister. He found a new father figure in an uncle who was also in a gang, so Christopher joined one too, associated with the Bloods. Soon after, according to Christopher, his uncle was sentenced to 50 years for the murder of a rival gang member.

In a 2014 psychological evaluation, Christopher spoke of growing up around the Bloods. “I remember seeing my uncle … the day after he was shot,” he told the evaluator. “He showed me the gunshot wound. … I have seen people get stomped out and have seen people get their ass beat.” He later attended a school dominated by the rival gang, the Crips. “I would have fights with Crips every day,” he said.

Not surprisingly, Christopher lost interest in school, though he was extremely bright. In middle school, he began to have run-ins with authorities, often due to fights with his mother. His aunt said he attempted suicide several times, feeling like he’d lost the only person who really loved him—his father.

According to documents put together for his clemency plea, by the time Young stopped attending school regularly, around the ninth grade, he had been a drugdealing gang member for several years. When he was arrested for Hasmukh Patel’s murder, he was also charged with car theft (which he later admitted to) and sexual assault (which he denied). In his trial, prosecutors presented evidence about both the car theft and, in the punishment phase, about the assault charge.

TEXASOBSERVER.ORG | 13

On Texas’s Allen B. Polunsky Unit in Livingston, death row inmates live in single-person, 60-square-foot cells and are not allowed to

For Mina Patel, their early years in the United States were about working hard and being with her husband Hasmukh.

work. They receive one hour of solo recreation per day. At least eight death row inmates have committed suicide in the past 20 years. Christopher would spend a dozen years in one of these cells.

His aunt believes Young’s transformation began on death row. Harris hadn’t seen him in years, but she wrote and began to visit him in Polunsky.

“When I first saw him, he was so angry,” Harris said. He learned from the other inmates how to protest when they were treated inhumanely. When inmates refused to move, a “force team” of guards came in to physically move them. Because force team actions had to be documented on video, inmates used the recordings as a tool to voice their grievances.

Another Polunsky inmate, Ronald Prible, writing in support of Young’s bid for clemency, recalled an incident when guards were punishing the person in the adjacent cell by denying food. In protest, Young “jacked his bean slot,” jamming the horizontal slot through which food trays are delivered. The force team was called, and Young was disciplined. The incident stuck with Prible because Young, who was Black, had been advocating for a white man.

“Most people here wouldn’t stick their necks out for anyone, especially someone of another race,” wrote Prible, whose death sentence was overturned in 2020 because of allegations of prosecutorial misconduct by a white prosecutor.

Harris said Young repeatedly looked out for fellow inmates. When he learned one of his neighbors was planning to kill himself, he stayed up all night and talked him out of it. He began to read incessantly, wrote, painted, and connected with fellow inmates and his family—especially his daughter Chrishelle, who was only 2 years old when he was sent to prison. Through his aunt, he began to connect with troubled young people outside prison.

When youths she knew were struggling with disciplinary or mental health issues, Harris started bringing them to Young. He would share his story but also encouraged them to find creative outlets. Those discussions sparked something in him.

“It was like he found a purpose,” Harris said.

Texas Innocence Project founder and attorney David Dow, with the help of another

lawyer, students, and volunteers, handles the appeals of some Texas death row inmates and took on Young’s case in 2013. Dow said he found Young to be an exceptional person, “easily a guy who would’ve been a friend of mine if he hadn’t been on death row.”

New York artist Peter Charlap had never thought much about prisons until he heard an NPR interview with Dow about his death row work. Wanting to help, he contacted Dow, who put him in touch with Young. Charlap began visiting the prison to paint portraits of the incarcerated.

When he first met Young, Charlap asked what he dreamt about in prison. Young’s answer was to ask whether the artist had read Carl Jung. “And I realized, I’m talking to a highly intellectual person,” Charlap said. “Very well read. Very charismatic.” His portrait shows Young behind a chessboard.

Charlap was fascinated with how the men played chess in their separate cells, calling out moves to one another. He said Young could play four games at once.

In 2016, Los Angeles-based filmmaker Laurence Thrush and other writers were working on a pitch for a series based on Dow’s work, and Dow put him in touch with Young. They began corresponding, and while the TV show was never made, Thrush’s friendship with Young grew. They began collaborating on a documentary film. When Thrush met British actor and producer Chike Okonkwo (Being Mary Jane, La Brea), who had moved to Los Angeles and was increasingly interested in the criminal justice system, he introduced him to Young as well. Okonkwo found Young to be “kind and smart, artistic,” he said in an interview, and they, too, became friends.

Harris said the collaboration with

14 | TEXAS OBSERVER

“I was a typical Texan who was waiting for him to get executed.”

Mitesh Patel, center; his mother Mina at left; and wife Shweta, right, all eventually supported Young’s petition for clemency. They are shown with Mitesh and Sweta’s children.

Thrush built a fire under Young to bring about serious change. Thrush and Okonkwo, like Harris and Young, felt that the documentary could help troubled young men on the outside and also tell a story of the prison system from the inside.

Then the news came that Young’s execution date had been set.

When an inmate has exhausted all appeals, he is, in the lingo of Innocence Project workers, “on the brink” of having an execution date set. An inmate with an execution date is called a “crisis case.”

“We keep track of all of the cases that are on the brink, and we identify issues that we will raise if it becomes a crisis case,” Dow explained.

Dow’s team began to work on a

clemency petition for Young to the Texas Board of Paroles and Pardons, whose five members make recommendations to the governor. They consider the defendant’s crime, the defendant’s behavior while incarcerated, and the wishes of the victim or victim’s family.

Getting someone off death row doesn’t happen often—in 30 years, Dow has gotten 14 clients’ sentences changed from death to prison time and gotten four out of prison entirely. Even when he can’t do that, he said, “We still manage to keep our clients alive for months and sometimes years, sometimes many years longer than if we weren’t representing them. … It’s time that they get to spend [communicating and visiting] with their friends and their family and their loved ones.”

Dow had recently won relief for another client. Thomas Whitaker, a white man,

had hired a hitman to kill his family for insurance purposes. His mother and brother were killed. His father survived the shooting and advocated for his son’s clemency. The Pardons and Paroles Board voted unanimously for clemency, and Governor Greg Abbott commuted Whitaker’s sentence to life in prison without parole.

Thrush and Okonkwo thought Young might have a good chance for clemency because his crime, unlike Whitaker’s, was not premeditated, and Young had transformed his life while on death row. They decided to ask Mitesh Patel for help.

Mitesh Patel was 22 when his father died, and he shouldered much of the murder’s fallout. He inadvertently saw the security video of Young shooting Hasmukh. Mitesh identified his father’s body and testified at trial

TEXASOBSERVER.ORG | 15

to spare his mother and older sister Rinal the trauma of doing so. Over the next 14 years, whenever a major life event came along—marriage, becoming a father himself, business successes and failures—he drove to that store and sat in the parking lot, where he felt closest to his father.

He had kept tabs on Young’s case. “I was a typical Texan who was waiting for him to get executed,” he said with characteristic candor. “I really felt like the state was wasting all this time and money. This guy killed my dad with a 30-cent bullet. For years, I was like, ‘I will gladly provide the state with a 30-cent bullet and we can take care of this much, much faster.’”

Shweta and Mitesh had met in graduate school a few months before Hasmukh Patel was murdered, and she’d always felt the loss of not knowing this man who was so

important to her husband. But Mitesh’s idea of attending the execution to achieve closure had never sat right with her. She feared it wouldn’t give him the relief he sought.

As the execution date approached, Okonkwo had begun to worry about the clemency team’s plan to show up unannounced at the Patels’ house. He talked to Rebecca Weiker, a transformative justice expert who told him that at all costs he should avoid retraumatizing Mitesh. Okonkwo and the others decided to leave a letter saying they had a message from Young.

The actor and Thrush drove to the Patels’ house, got out, and put the letter in the mailbox. But as they headed back to the car, Shweta came out to speak to them. Mitesh was out of town, but she wanted to know who they were. Okonkwo noticed

that she was pregnant.

“As soon as we told her who we were, and that we had the message, she started talking to us excitedly, saying that maybe this would help Mitesh,” he remembered. Shweta went inside and called Mitesh right away. He was furious that she would speak to and be manipulated by these strangers.

A few weeks later, Thrush and Okonkwo came back, asking if they could show Mitesh a video message from Young. This time, Mitesh agreed, they met for breakfast, and Mitesh watched the video. In it, Young says that killing Hash Patel was the biggest regret of his life, that he wanted Mitesh and his family to know how sorry he was. Mitesh recoiled at hearing his father’s name coming from Young’s mouth. He didn’t trust the video or these men.

Thrush tried to tell Mitesh what he knew of Young’s background, the hardship he had gone through as a child, and how much it would hurt his 14-year-old daughter Chrishelle to lose her father.

“I was like, ‘What the fuck are you talking about?’” Mitesh said. “They were presenting stuff to me about how Chris is this great artist, eloquent, how they visit him often and it just pissed me off—here are two people from Hollywood … and Chris is their pet project, and they are shitting on me and my family and what Chris did to my family with this ‘Oh, poor Chris’ take.”

When he saw the meeting derailing, Okonkwo changed direction. “I told him that there is real evidence that watching an execution can retraumatize people who [have lost] someone to murder,” Okonkwo said. “I told him that I was honestly worried about him.”

Mitesh remembers his reply. “I was like, ‘Worried about me? You don’t know me, man. Worry about your own damn self.’”

Dejected, Thrush and Okonkwo headed back to Los Angeles. Okonkwo, though, couldn’t stop thinking about Mitesh. Over the next few weeks, he emailed, texted, and called. Eventually, Mitesh started picking up the phone when Okonkwo called.

“He’s so damn persistent,” Mitesh recalled, laughing. “And he always came at me with such sympathy.”

16 | TEXAS OBSERVER

Mitesh has just fed his father a piece of cake at his 50th birthday celebration

On one call, Okonkwo told Mitesh about how Young, in visits with his daughter, always said he was in prison solely because of his own actions and that she should “stay away from people like me and find good people to surround you.”

After the call, Mitesh found himself staring into his computer screen. It was late. Shweta was already in bed; the pregnancy had been hard, and the fact that her due date and Young’s execution date were so close had started to bother him, too.

“I was like, ‘Holy shit, I’m a dad, and here is another guy who is a father, and he is trying to impart something positive to his daughter, and if the state takes him away, that fatherhood stops,’” Mitesh said, thinking of how much he missed talking to his own father. “I finally thought, if there is a chance for me to stop it, then I could help his daughter Chrishelle not go through what I went through.”

Mitesh went to the bedroom and woke Shweta to tell her. The next morning, he told his mother, who also agreed. Mitesh called Okonkwo back and said he wanted to help with the clemency attempt. Okonkwo connected him with Dow, who was surprised by the development. It wasn’t often that he saw this in Texas.

The execution was only three weeks away.

Over the next few weeks, with Okonkwo’s help, Mitesh attended rallies and spoke to local and national reporters. Thrush edited some of his footage into a video to accompany Dow’s legal brief. In addition to Young’s family members, it included testimony from 12 other Polunsky inmates attesting to the positive force he had become on death row.

Mitesh called TDCJ’s Victim Services Division to request a meeting with Young but was told that was impossible. Mitesh could write a letter, they said, and they would bring back Young’s recorded answers.

“It started to bother me, like, why can’t I go and talk to him?” Mitesh said. Both Victim Services representatives and the prosecutor who had tried the case contacted Mitesh to ask if he really wanted to do this. They warned him that Dow was known for theatrics, and they didn’t want Mitesh and his family to be manipulated.

“I really didn’t know who to trust at that point,” Mitesh said. It was “like everyone had their own agenda.”

Dow arranged for Mitesh to meet with the parole board in Austin. “They wanted to know why I was doing this and who had put me up to it,” Mitesh said. When Mitesh told them what he knew about Young’s early life, they told him about the man’s rap sheet and infractions from his early years in Polunsky. Mitesh left feeling as though he was doing something wrong.

A few days later, on Sunday, July 8, Shweta was feeling off and told Mitesh that she was going to take a nap. He got worried. Shweta said everything was fine, but he took her to the hospital anyway. Mitesh was right to worry: The baby was in the breech position and his heart rate was erratic. Shweta was rushed into surgery

for an emergency cesarean section. They named the baby boy Rushabh Hasmukh Patel, after Mitesh’s father.

Shweta and the baby were still in the hospital when Okonkwo arrived to say he’d arranged for Mitesh to do an interview on Good Morning America. National pressure on Abbott might make a difference, but the interview was the next day. In New York City.

“I remember Chike asking me if it was OK if [he took] Mitesh, and I was like, no question—you have to go,” Shweta said. She had her parents and Mitesh’s sister to help.

When they arrived at the TV studio in New York, however, a producer said the story had been bumped for one involving former President Donald Trump and a Scottish golf resort. Shortly after, they got the news from Dow that the pardons and paroles board had voted unanimously to

TEXASOBSERVER.ORG | 17

“Christopher Anthony Young” 24” x 20” oil on panel (Copyright 2014 Peter Charlap)

move forward with Young’s execution. The bid for clemency was over.

Okonkwo couldn’t believe that he had dragged Mitesh away from his newborn son for nothing.

But Dow had another idea. He and his team sued, claiming that the Texas Board of Paroles and Pardons’ action was racist, citing the evidence that they had voted in favor of Whitaker’s clemency, but ruled the other way when it came to an IndianAmerican victim and family and a black defendant. Dow pointed out other cases in which survivors of a victim opposed the execution of the perpetrator. In all the cases where the parties were people of color, he said, clemency was unanimously denied. However, in the case of Whitaker, a white man, it was unanimously granted.

The judge who heard the suit seemed bothered by those facts, Dow said.

According to the Texas Tribune, U.S. District Judge Keith Ellison expressed frustration that he felt required to reject the appeal because Dow’s team had so little chance of proving racial discrimination.

Mitesh was on his way home from the airport when his cellphone rang. Someone from U.S. Representative Sheila Jackson Lee’s office was asking if he’d still like to meet Christopher Young in person. Mitesh said he would.

Later, Mitesh got an angry call from the head of Victim Services.

“He said, ‘I don’t know who you know, but I am on vacation out here on my ranch, and I got a call that I need to arrange a visit for you in Huntsville tomorrow, so you need to be there at 9 a.m. sharp,’” Mitesh recalled.

The next morning, Mitesh drove three and a half hours to the Walls Unit in Huntsville, where Texas executions are carried out. When he arrived, the parking lot was empty—the prison had been put on lockdown. A Victim Services staffer accompanied Mitesh to the meeting.

On the phone in a visitation room, separated from Mitesh only by a glass wall, Young apologized, saying that he should have never gone into the store that day and that Mitesh’s father should be alive. Mitesh asked questions about Young’s time in prison and about his daughter. Young

told him how he’d tried to reach young people from inside prison.

“Then I apologized to him,” Mitesh said, “I told him that I was sorry I didn’t come around earlier, that if we had more time, maybe I could have done more to make sure he got his sentence commuted.”

Mitesh told him that he would be there as a witness the next day, not for closure or vengeance, but so Young did not have to die alone—and that he knew that’s what his father would have wanted.

Young held his hand up to the 3-inchthick glass and motioned for Mitesh to do the same—their two hands similar in color and size. “You don’t have to do that. It was enough for you to have to watch your father die on that security video,” he told Mitesh, “I don’t want anyone to have to see that. I need to do it alone.”

Young took all his friends and family off the execution-day list, but he made his Aunt Valerie his spiritual advisor so she could be with him on July 17, in the hours before his execution. He was excited to tell her about his meeting with Mitesh. He called his family, who had all gathered in one place to say goodbye, which was joyful and painful.

“Then we got into an argument,” Harris recalled. She told him she would be there at the execution. He got mad and began to cry.

“It was the first time I had ever seen him cry,” Harris said, her voice breaking, so she backed down and agreed to stay away from the execution room. “He said, ‘But I’m not done yet.’”

Young told her he might fight the injection to protest the system one last time. But Harris said she understood now that she had been praying the wrong way in those last few days. Instead of praying for clemency, she should have been praying for peace.

“I said, ‘Baby, you don’t have to ever go back into that prison today. You gonna be free.’ … I said, ‘I’m not telling you not to fight, but fight with your words, think about the children. Show them the way with your words.’ I said, ‘Unless a seed is planted in the ground and dies, it bears no fruit. Be the seed.’ And he told me to go back to death row and tell his brothers to take the torch he had lit and run with it,

and we prayed together, and I told him to go and take his rest.”

As she left to go to the chapel, she heard him laughing with the guards. Who does that, she thought. What kind of man can laugh with the guards that are going to kill him?

The Patel family had gathered in San Antonio. The two boys, Rishaan, 4, and Roshan, 2, played while the adults passed the new baby around. Before 6 p.m., Mina went to her altar.

Then the family fell silent as the TV news reported Young’s final words: “I want to make sure the Patel family knows I love them like they love me,” he had said. “Make sure the kids in the world know I’m being executed, and those kids I’ve been mentoring, keep this fight going.”

For days afterward, Harris couldn’t get out of bed or eat. But she made the trip to Polunsky a few days later. She visited all of her nephew’s closest friends and told them about his final day, sat with them as they cried and mourned, and made plans to continue his outreach work.

Thrush and Okonkwo were banned from visiting Polunsky because they’d used footage from the documentary to advocate for Young.

A year and a half after Young died, the COVID-19 pandemic swept through the country and shut down normal life, making it hard to visit Polunsky. But Harris kept up her work. Today, the Christopher Young Foundation: Love, Forgiveness, and Second Chances has its 501(c)(3) classification as a formal nonprofit organization.

Work continues on the documentary. Thrush said Young’s story will be there for future generations to learn from. Mitesh and Okonkwo remain close. They text each other often and talk about how they can make a change together somehow.

“People get it wrong,” Mitesh said. “I never forgave Chris for killing my dad, but I thought there was value to his life and that he was trying to do something good for his daughter, for other kids.” He wants to share his story in the hope that others will help him “make a change in this world as a way to honor my father and the values he instilled in me.”

18 | TEXAS OBSERVER

Neelanjana Banerjee is a writer and editor based in Los Angeles.

Mitesh Patel, shown in the store where his father was killed, said he didn’t forgive the killer, “but I thought there was value to his life.”

TEXASOBSERVER.ORG | 19

SHORT-TERM HOUSING , LONG-TERM MESS

GIANT RENTAL PLATFORMS ARE CREATING DRAMA IN THE STREETS—AND PUTTING MONEY IN THE COFFERS OF TEXAS CITIES.

By EVA RUTH MORAVEC

Photography by SHELBY TAUBER

By EVA RUTH MORAVEC

Photography by SHELBY TAUBER

In this Plano neighborhood, when a party at a short-term rental turned violent, a bullet went through a neighbor’s window.

Gunfire jolted Zoey Sanchez awake that night in February, not something she heard often in her usually tranquil neighborhood in Plano, north of Dallas. Then she heard screeching tires. After a few minutes, Sanchez peeked out a window to see police officers detaining a young woman.

Sanchez eventually went back to sleep. Then it was sunrise, and her husband was jostling her awake. You need to get up, he said. There’s drama. She grabbed a bathrobe and walked out of the front door—and into chaos.

Outside, news crews and upset neighbors had descended on remnants of an active crime scene. And everyone seemed to be looking at her house—specifically, at a window in her young daughter’s playroom. She learned that a party at the shortterm rental house across the street had turned into a gunfight, and one bullet had ricocheted around her daughter Luna’s playroom, crossing the nook where Luna likes to read. Thankfully, Luna had been asleep in her bedroom, tucked away from windows facing the street.

The two-story brick rental house had become a frequent source of trouble for the neighborhood Sanchez loved. An outsider had bought it, sunk a lot of money into it, tried to sell it, and then turned it into a bed-and-breakfast. For months, loud tenants and their guests had disrupted the street. Neighbors had seen partygoers peeing in the yard, hanging out of windows, and screaming. Their cars filled the block. To neighbors, police had seemed unable, and the owner unwilling, to address the stream of complaints. Now the partying had escalated to violence that could easily have killed Sanchez’s daughter.

Shootings, with horrific consequences, have become almost commonplace at Texas schools, houses of worship, restaurants, shopping malls, and concerts. This time, Sanchez feared she’d have to explain to Luna that she might not even be safe from gunfire in her own home.

“As a mom, you don’t care about yourself. But your biggest thing is, you want to have your kids safe,” said Sanchez, an occupational therapist. “So when your house is not safe anymore, you’re like, ‘Well, that sucks. I failed.’”

When Sanchez began researching the

situation, she found that the problems at B&Bs in other neighborhoods were equally serious. The previous fall, police busted a sex trafficking ring operating a brothel out of a short-term rental three miles away. In nearby Wylie, a woman allegedly used an Airbnb in fall 2021 for sex trafficking her 8-year-old daughter. In northwest Dallas, according to news reports, an Airbnb unit owner fired his management company after neighbors complained about visitors and armed security guards.

What had once been a way for visitors to find charming, off-the-beaten-path lodgings—and a way for local property owners to make extra money with little neighborhood disruption—has become a global business dominated by corporate investors that in many places threaten the safety and character of residential neighborhoods. How short-term rentals (or STRs) fit into the local landscape varies, but it’s becoming universally accepted

that, left uncontrolled, their impact can be immense. In some places, they are making rental housing so lucrative as tourist lodging that it is becoming unavailable and unaffordable to local workers, students, and other residents. Selling for higher prices, they drive up property values and neighborhood tax bills and replace families with a steady stream of strangers—whom locals see as producing more crime and less accountability than traditional renters.

Neighborhoods tend to be—or used to be—a strong force in Texas politics. Often, angry neighbors’ comments have been loud enough to kill off affordable housing or commercial developments. But short-term rental companies with highly paid lobbyists, worldwide reach, the offer of hotel-tax millions to local and state governments, and the support of local B&B owners and operators, are a formidable force. Cities around Texas and the world, from San Juan to Taipei to Barcelona, are scrambling to

22 | TEXAS OBSERVER

Zoey Sanchez and her daughter, Luna, sit in the playroom of their home in Plano, which was struck by a stray bullet fired from a party at a nearby Airbnb in February.

address resulting problems.

Some neighborhoods in Fredericksburg appear deserted during the week because so much housing is aimed at weekend guests—while the popular tourist town has a labor shortage because of the lack of affordable housing. In Galveston, shortterm rentals are worsening the lack of housing for working-class and middle-class residents. In Arlington and Fort Worth, residents fought for regulatory measures, with threats of lawsuits always in the air. In Dallas, it took four years for a strong neighborhoods coalition to win city council approval of an ordinance banning such rentals from single-family residential areas.

“We stand together, although there were more of us earlier today, and we represent about 500,000 other homeowners, and there are renters too, who unfathomably find ourselves as the underdog in this fight,” said Olive Talley, one of the leaders of the fight against short-term rentals in Dallas, a few hours before the city council passed the ordinance.

In the meantime, B&B corporations have crafted deals to pay hotel taxes on behalf of rental property owners to the state and some cities. For individual owners, those deals help shield them from state scrutiny over how much they should be paying in taxes and being identified as short-term rentals for tax and zoning purposes. At the same time, they provide the kind of income to states that engenders a lot of goodwill. Since May 2017, Airbnb, one of the largest companies, has paid Texas more than $229 million, and HomeAway has paid more than $57 million, according to the state comptroller’s office.

Bills to prevent cities from regulating short-term rentals have been filed—and thus far defeated—in the Texas Legislature repeatedly since 2017 and likely will be filed again.

For now, city councils continue to struggle to pass rules that can pass muster in expensive court challenges, where by a slight margin, rental property owners are ahead. The result has been a patchwork of partially enforced regulations, dwindling housing stock, and, in some cities, the continuing degradation of neighborhoods.

In 1995, a retired teacher started a website to rent out his Colorado ski resort condo. Five

years later, Vacation Rental By Owner, or VRBO, was advertising properties in all 50 U.S. states and 28 countries. Then, in 2005, venture capitalists in Austin started a company called HomeAway with six employees who quickly bought up similar companies. Within two years, HomeAway raised $160 million and bought VRBO. The combined company, called VRBO, operated more than 130,000 properties in almost 100 countries. It had no real competition until a new San Francisco-based website called Airbed and Breakfast officially launched at South By Southwest in Austin in 2008. Built with less than $20,000, the website helped hundreds of people find accommodations in places where hotels were already sold out—in Denver, for instance, for the Democratic

National Convention.

Bed-and-breakfasts were already popular in Fredericksburg by the 1990s. They were mostly the kinds of places where hosts fixed breakfast for visitors, and owners often lived onsite. A few reservation services popped up to help manage bookings at hundreds of such lodgings.

That picture changed by the new millennium, with VRBO going strong and Airbnb newly launched. Homeowners like Austin’s Sharon Walker were getting involved. She and her husband were in trouble on the mortgage on their dream home downtown. They had to sell it or figure something out.

“We’d heard about this company, HomeAway. I contacted all of the five listings that were there at the time for Austin, and one woman took the time to talk to me,” Walker said. “She said it was successful.”

Walker and her husband moved across the street and put their house up for shortterm rental on HomeAway. In 2010, Walker rented her house for $500 a night, almost every weekend, and watched through the kitchen window as visitors checked in across the street. She learned to avoid problems by asking potential guests about the nature of their trips and groups. At first, she thought of it as “not a business” because it was “still the residential use of a home.”

The next year, prior to SXSW, Walker heard from desperate Google and Apple executives who’d found local hotels sold out. Walker emailed 30 friends to see if they’d host people in their homes and got 15 yeses. She coordinated the guests’ stays as a festival rental manager. The next year, she rented out 150 houses for SXSW. By 2012, Walker’s management gig had become a business.

While the lodgings offered by Walker and other “hosts” on HomeAway and Airbnb were becoming popular, they were also attracting the attention of cities. In 2011, the Austin City Council, alerted to the tax income potential of short-term rentals, approved a study. They found that, while some operators had been paying hotel occupancy taxes—money traditionally used to promote tourism—only 80 of 200 originally identified short-term rentals were paying it. And then an audit found that the number of units was closer to 1,500.

Kathie Tovo, then a council member

TEXASOBSERVER.ORG | 23

“AS A MOM, YOU DON’T CARE ABOUT YOURSELF. BUT YOUR BIGGEST THING IS, YOU WANT TO HAVE YOUR KIDS SAFE.”

and a strong opponent of short-term rentals in residential neighborhoods, said that opposition to a proposed ordinance usually comes from owners who have only one or two rental properties. But as the city accumulated information, she told the Texas Observer, “More often it looked like … people were making their living this way—you know, they were acquiring four or five properties.”