BROKEN PROMISES

The Biden Administration is still separating immigrant kids and their families.

By JOHN WASHINGTON & ANNA-CATHERINE BRIGIDA

By JOHN WASHINGTON & ANNA-CATHERINE BRIGIDA

CATASTROPHE #88

By TEXAS OBSERVER STAFF

TEXAS’ “RED WAVE”

By ERNIE MORÁN

BREAKING THE BRAZOS

By KATHRYN JONES

since 1954 JANUARY/FEBUARY 2023

INVESTIGATING TEXAS SINCE 1954

EDITOR’S NOTE

Breaking the Brazos Development is straining

By KATHRYN JONES

By KATHRYN JONES

CONTENTS

01 EDITOR’S LETTER

02 POLITICAL INTELLIGENCE

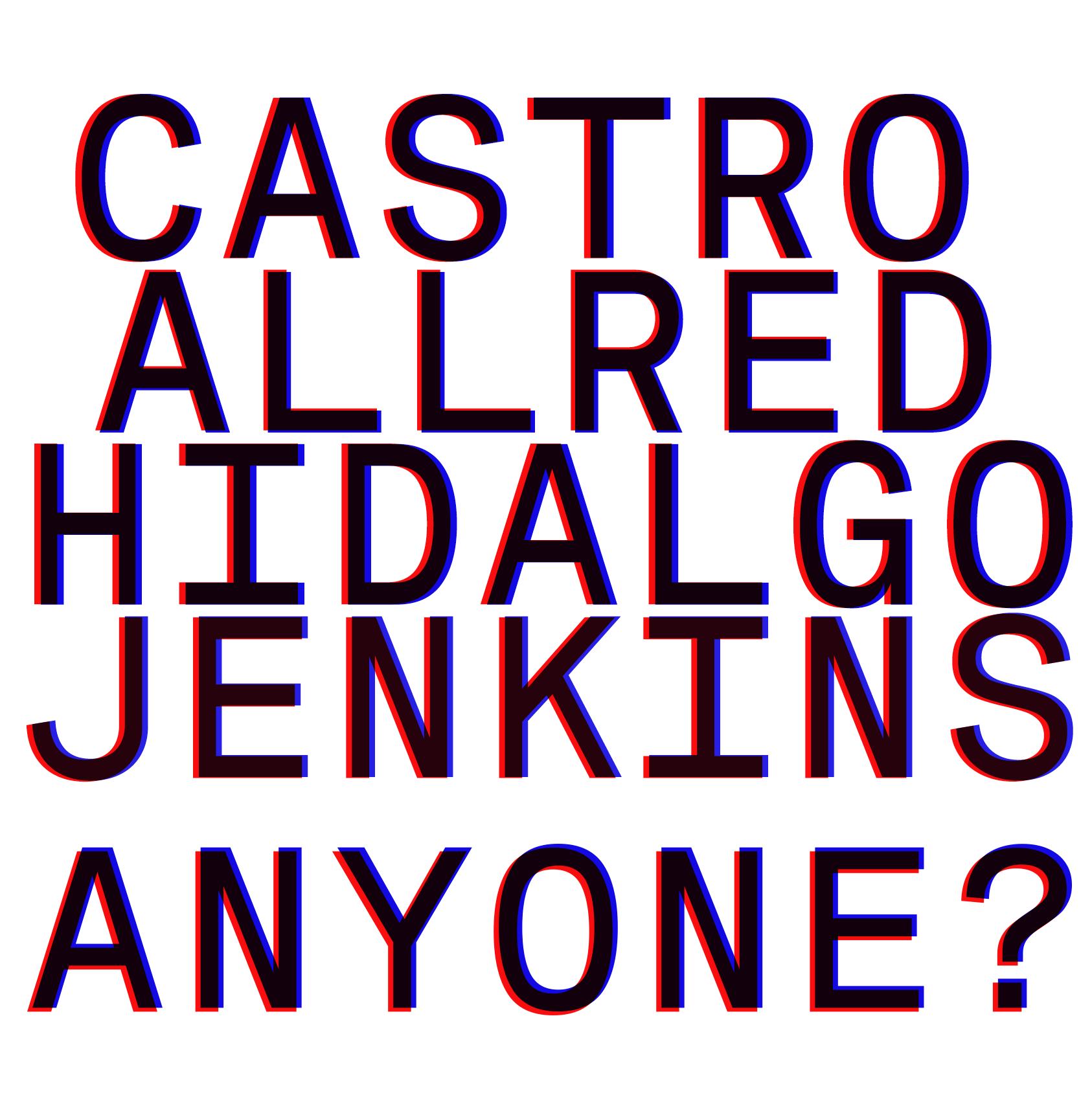

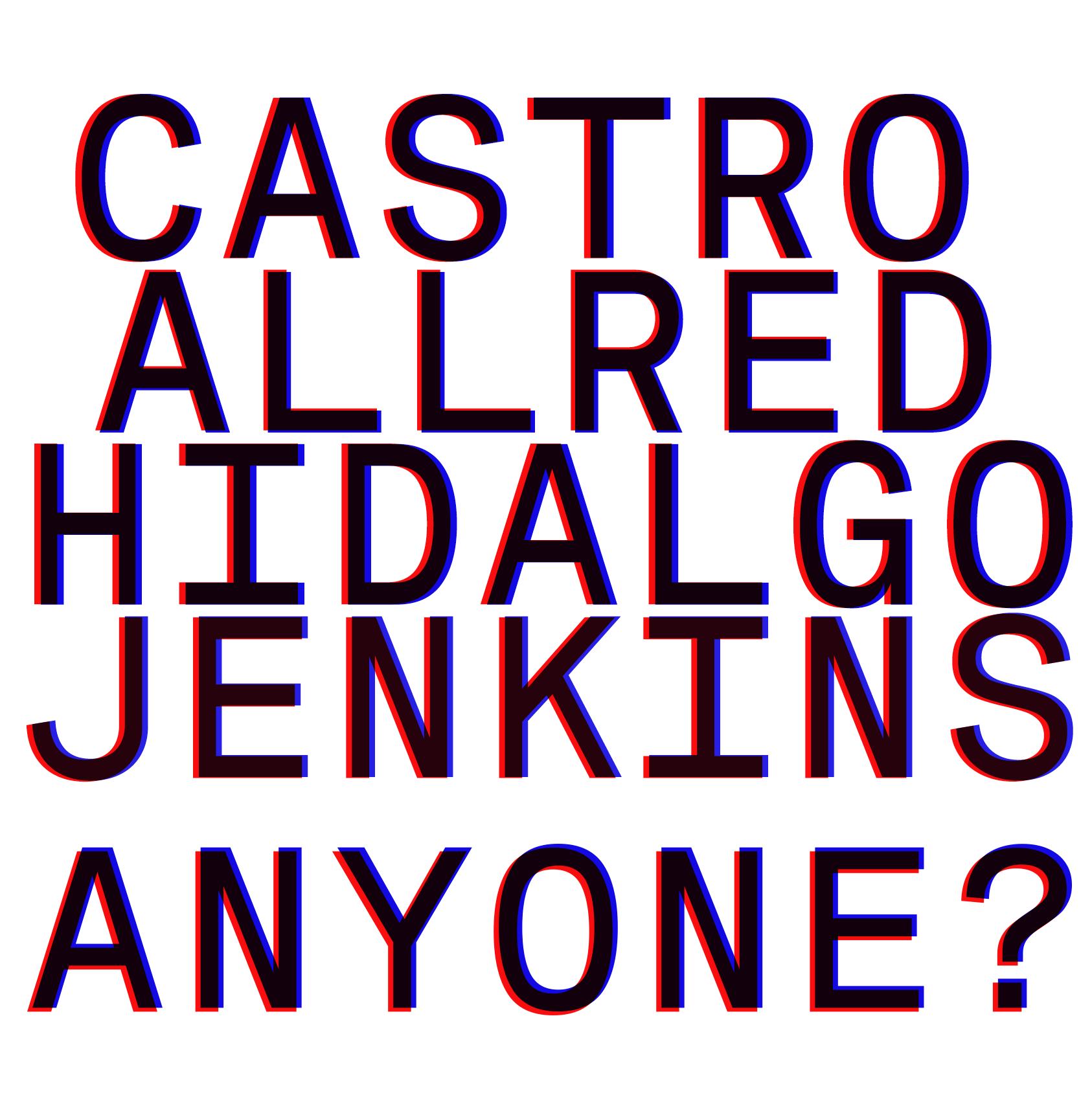

Who besides Beto O’Rourke can progressives in Texas now hang their hopes on? by JUSTIN MILLER

04 EYE ON TEXAS

The “red wave” fizzled nationwide but swept Texas as expected.

What now? by ERNIE MORÁN

06 THE INTERVIEW

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023

EDITOR- IN - CHIEF Gabriel Arana

CREATIVE DIRECTOR Ivan Armando Flores

SENIOR WRITER & EDITOR Lise Olsen

EDITOR-AT- LARGE Gayle Reaves

DIGITAL EDITOR Kit O’Connell

SENIOR WRITER & ASSISTANT EDITOR Gus Bova

SENIOR WRITER Justin Miller

STAFF WRITERS Delger Erdenesanaa, Michelle Pitcher

EDITORIAL FELLOW Arman Badrei

INTERN Ikram Mohamed

POETRY EDITOR Naomi Shihab Nye

STAFF CARTOONIST Ben Sargent

COPY EDITOR Adam Muro

FACT CHECKERS Zein Jardaneh

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Anna-Catherine Brigida, Matt Byers, Kathryn Jones, Andrew Logan, Ernie Morán, Roberto Ontiveros, John Washington, and Byrd Williams IV

CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS

Sarah Bell & Drue Wagner

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Fred Ramos, Christopher Lee, Mathew Busch, and Shelby Tauber

MANAGING DIRECTOR James Canup

DEVELOPMENT MANAGER Lauren Benavides

SPECIAL ADVISOR Bob Frump

TEXAS DEMOCRACY FOUNDATION BOARD

The Biden Administration

Is Still Separating Families

Children and their guardians are being cleaved apart in Texas—and elsewhere—two years into the new president’s term.

By JOHN WASHINGTON & ANNA-CATHERINE BRIGIDA

Newly elected Democratic caucus leader Trey Martinez Fischer of San Antonio on what the opposition has in store for the next legislative session by GUS

Laura Hernandez-Holmes (president), Lize Burr, Carlton

Carl, Saneta Devuono-Powell, Kate Donaho, Carrie James, Vince LoVoi, Cari Marshall, Ronald Rapoport, Peter Ravella, Lizette Resendez, Ronnie Dugger (emeritus), Abby Rapoport (emerita)

FOUNDING EDITOR Ronnie Dugger

OUR MISSION

We will serve no group or party but will hew hard to the truth as we find it and the right as we see it. We are dedicated to the whole truth, to human values above all interests, to the rights of humankind as the foundation of democracy. We will take orders from none but our own conscience, and never will we overlook or misrepresent the truth to serve the interests of the powerful or cater to the ignoble in the human spirit.

The Texas Observer is a progressive nonprofit news outlet and print magazine covering the Lone Star State. The Observer strives to make Texas a more equitable place through investigative reporting, narrative storytelling, and political and cultural coverage and commentary. We dig

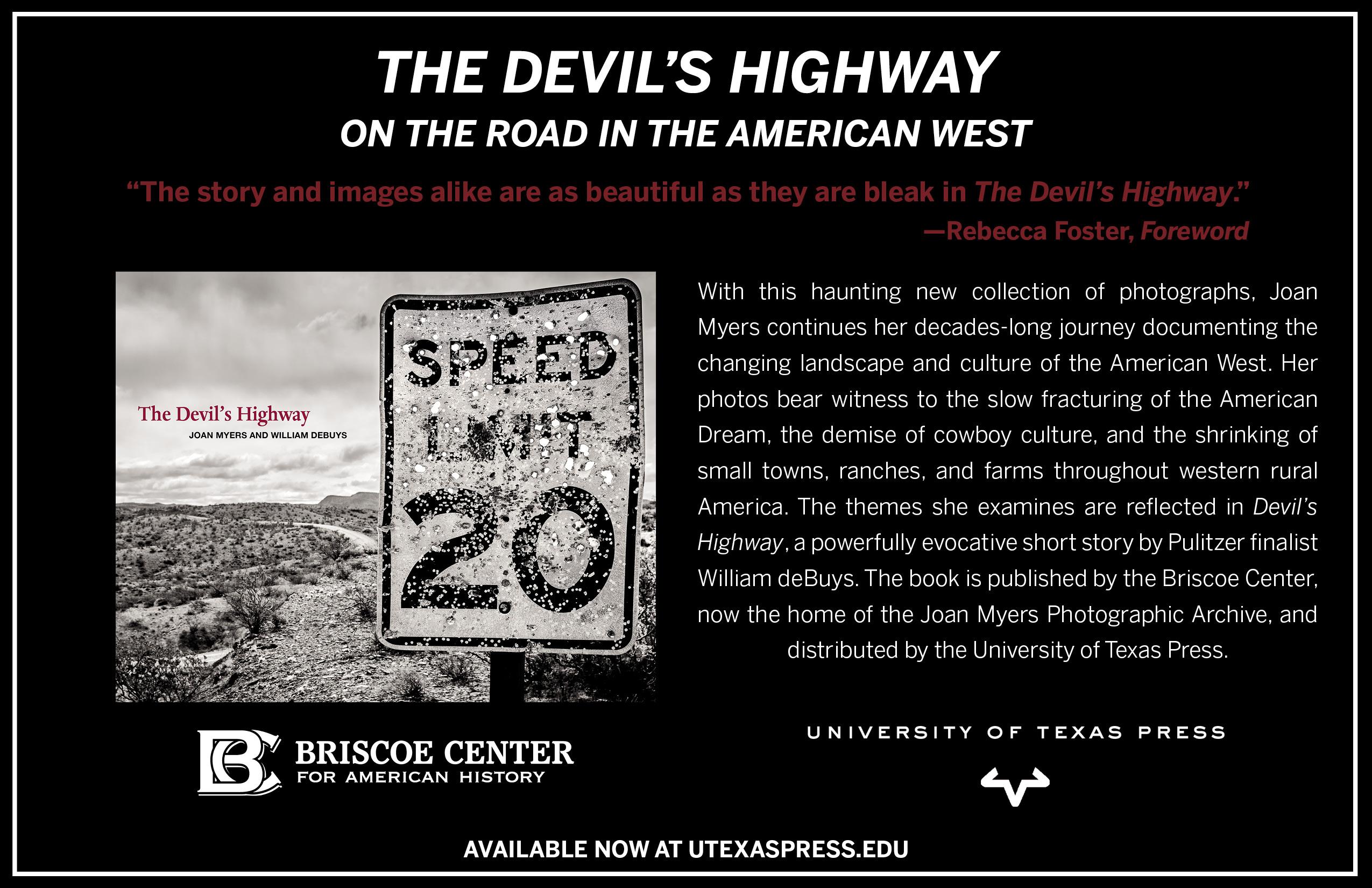

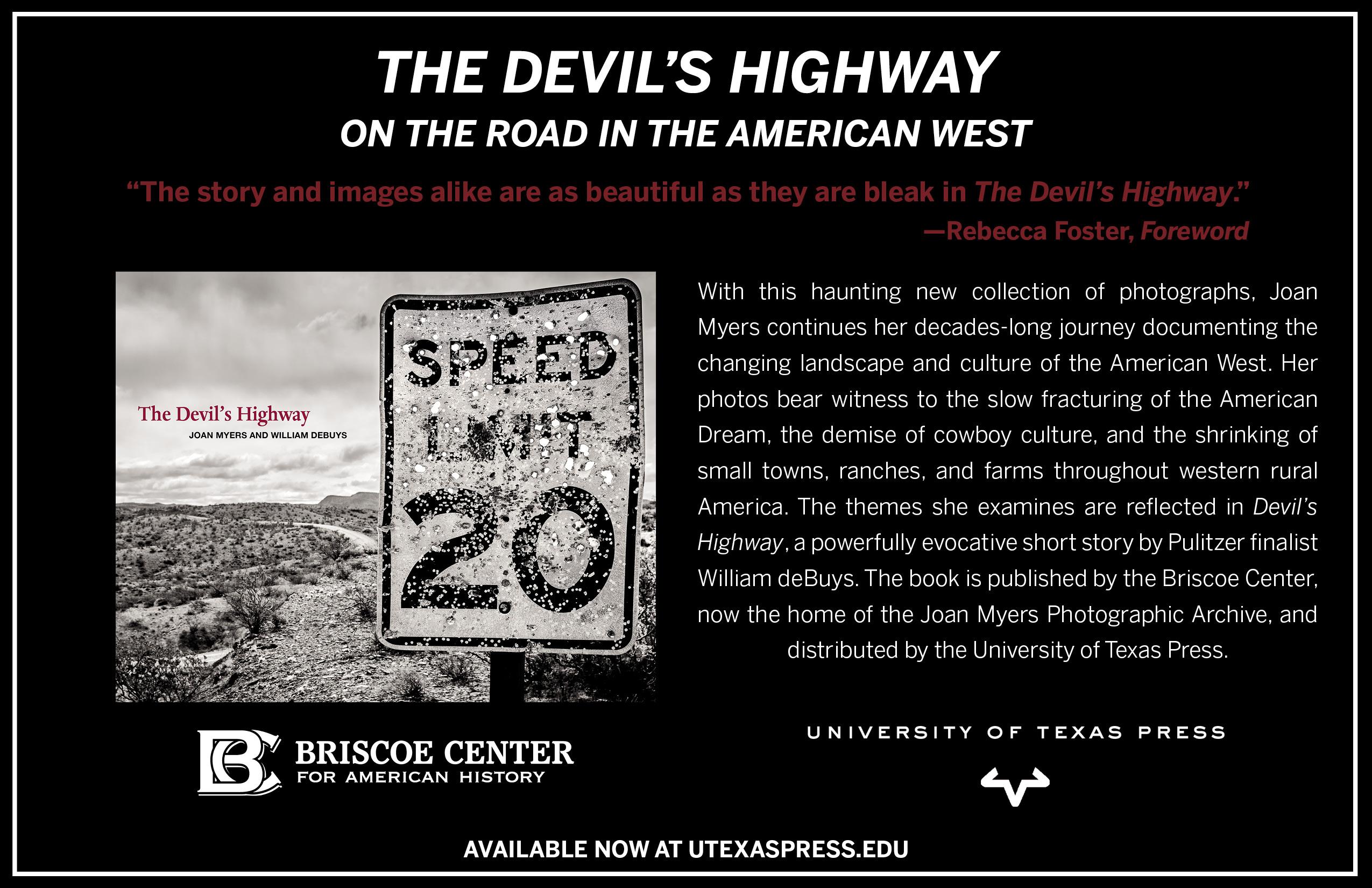

President Joe Biden promised to end the cruel, Trump-era policy of tearing immigrant kids away from their families. But as Contributors John Washington and Anna-Catherine Brigida’s investigation documents in our cover story, family separation is alive and well in this country. As one advocate told the reporters, “We said, ‘Never again,’ but here we are.” And in the next installment of our series on Texas rivers and the threats that endanger them, “Drifting Toward Disaster,” Contributor Kathryn Jones wonders how much longer the Brazos River can provide what a skyrocketing state population is going to need.

With midterm elections behind us, progressives in Texas have yet another session of the Legislature to dread. Senior Staff Writer Justin Miller takes inventory of the damage while Contributor Ernie Morán offers a postelection salve and call to action. Looking ahead, the staff of the Texas Observer consider how legislators could address the myriad social problems facing Texas denizens—and what they’ll likely do instead.

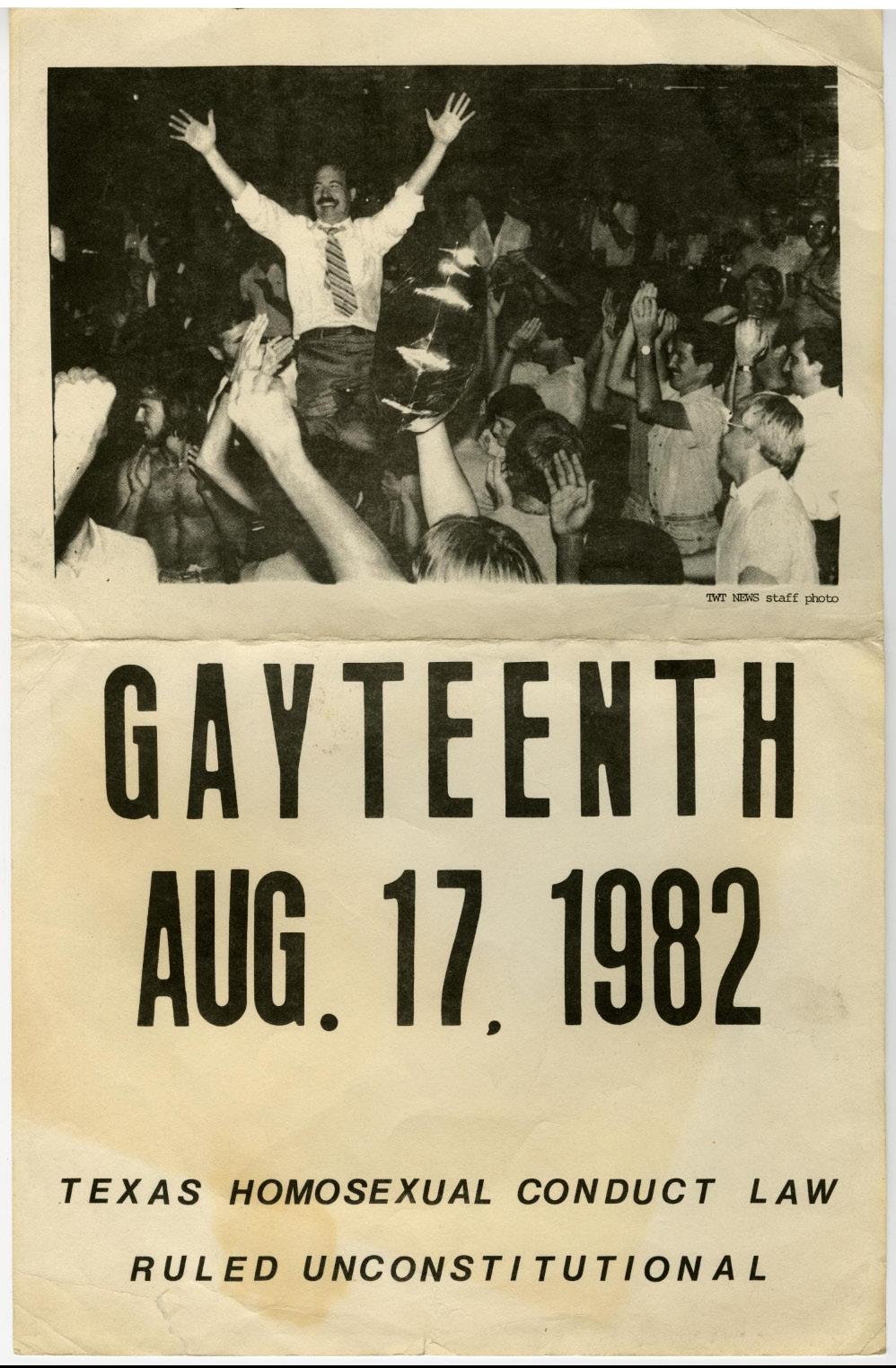

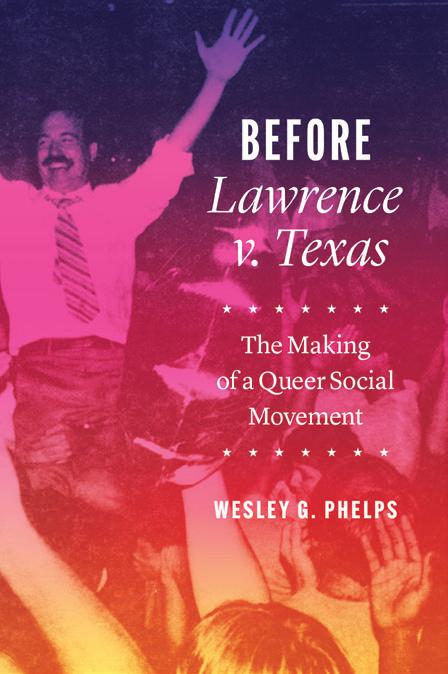

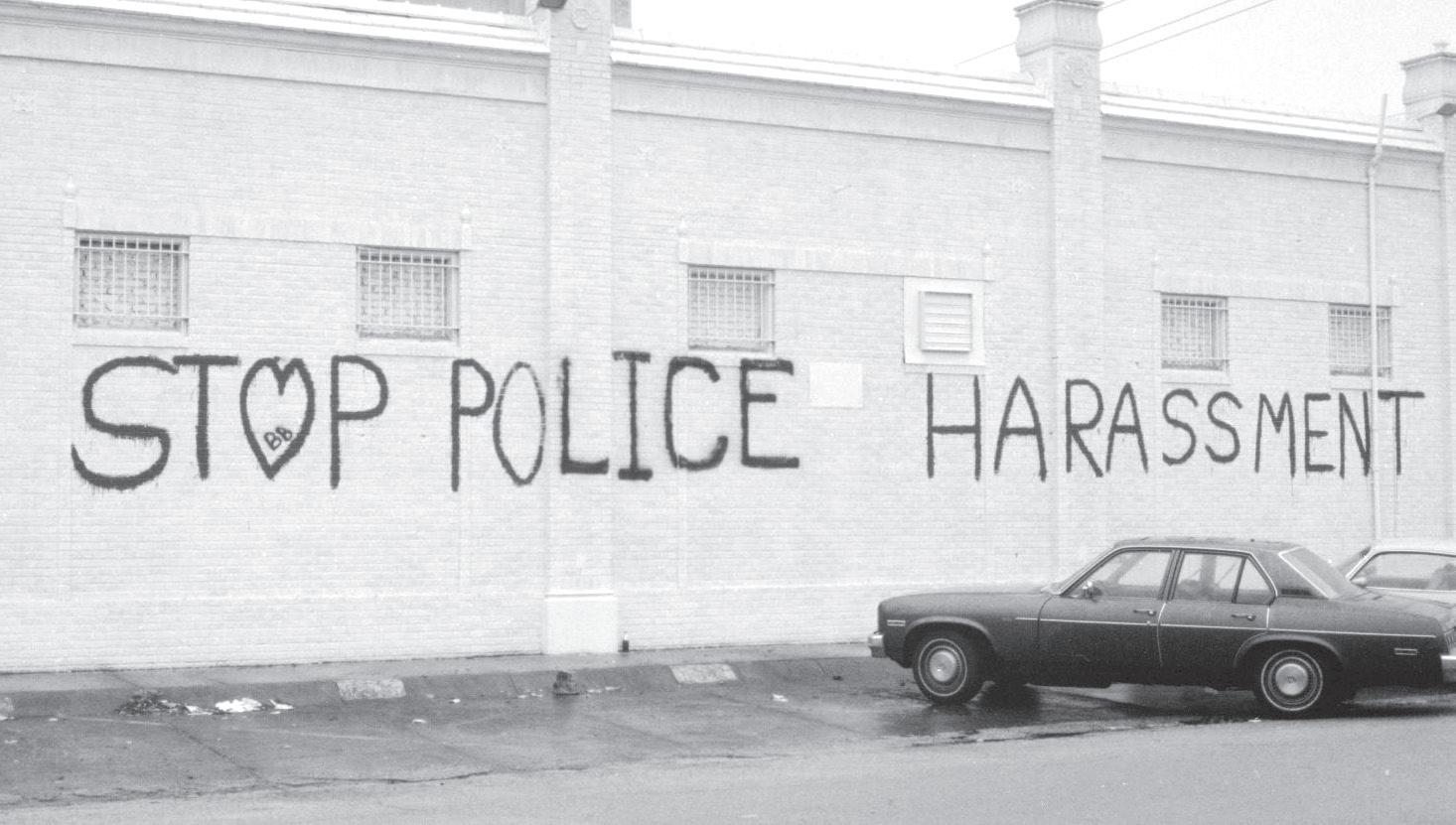

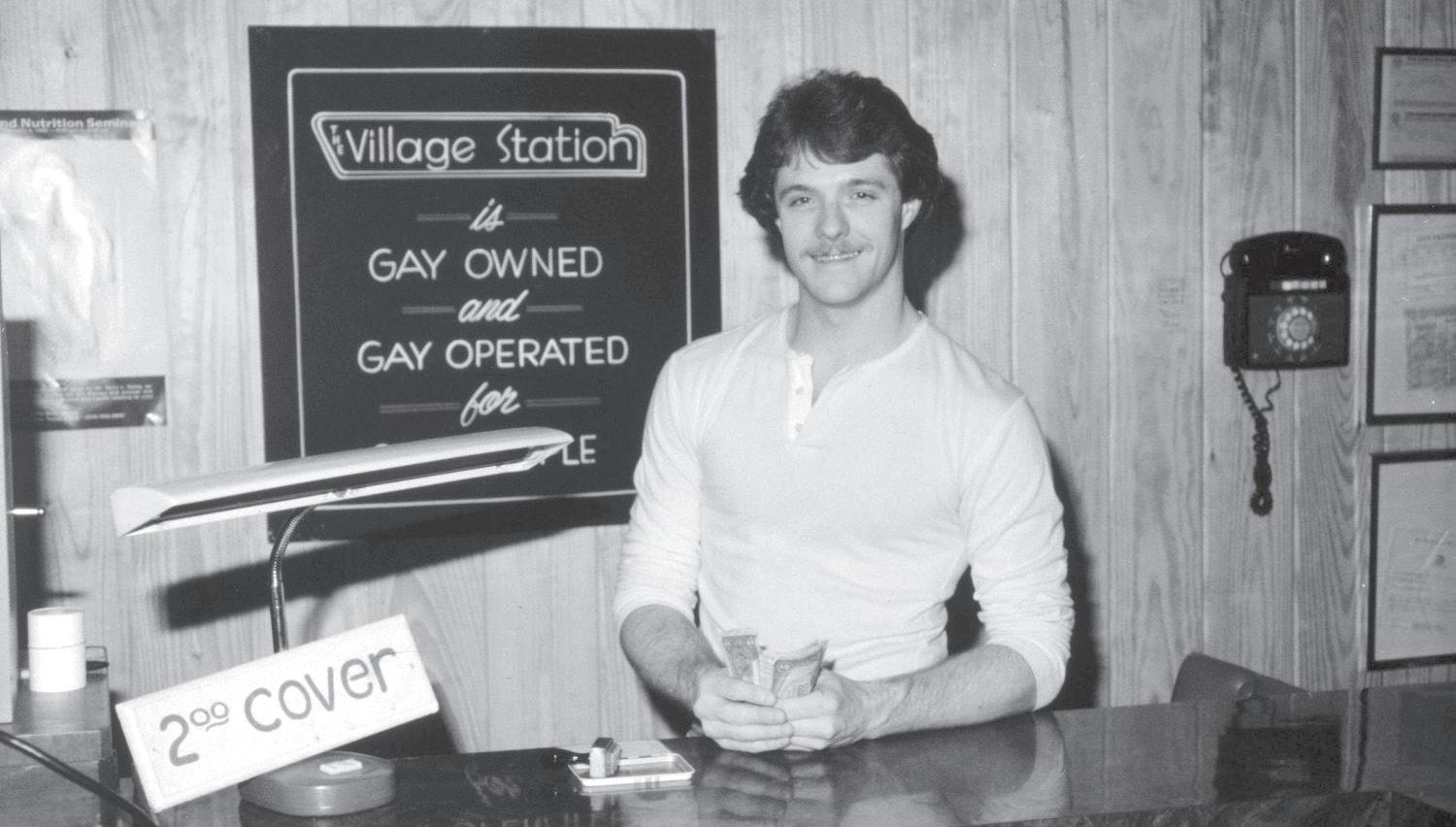

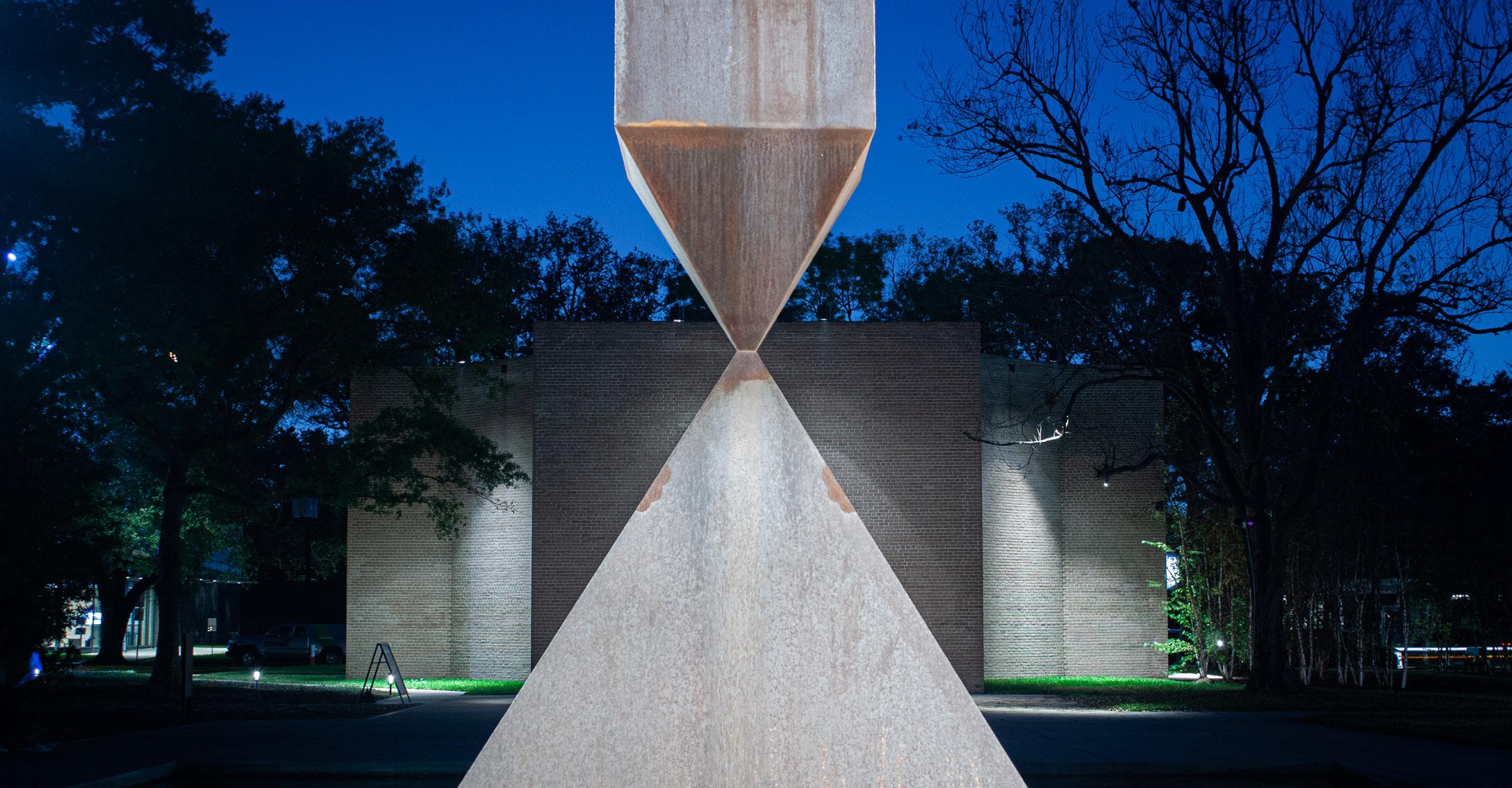

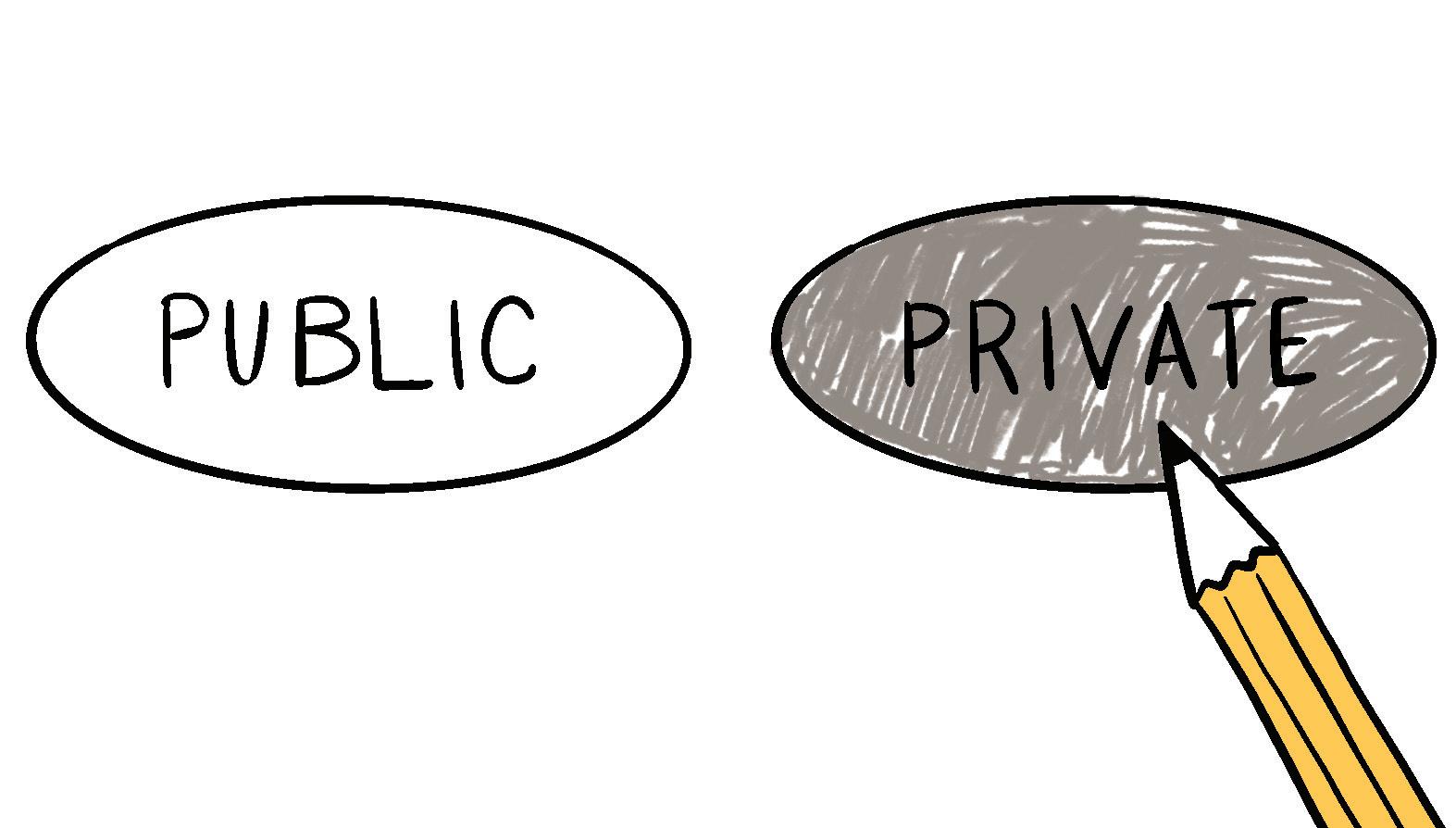

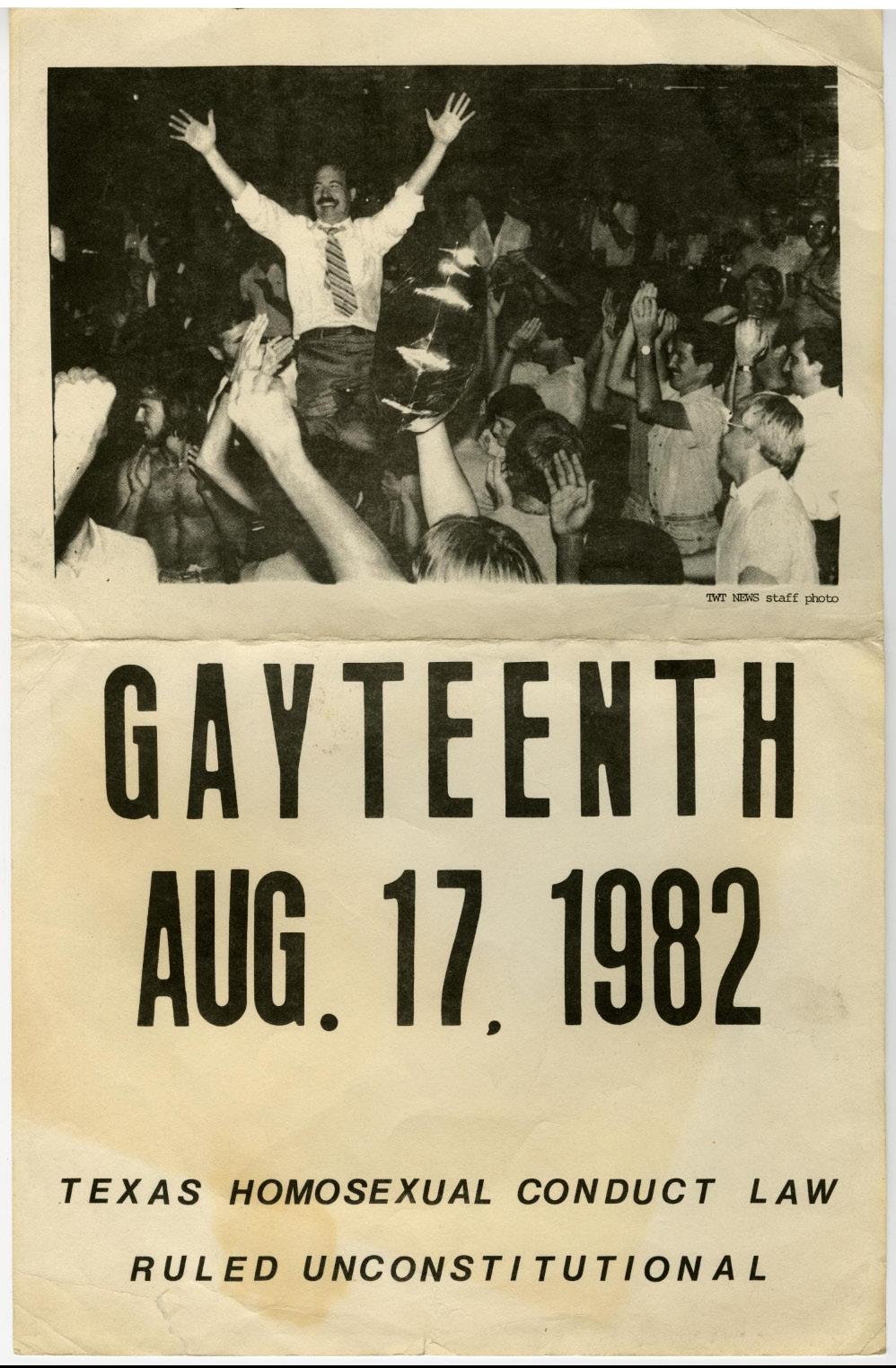

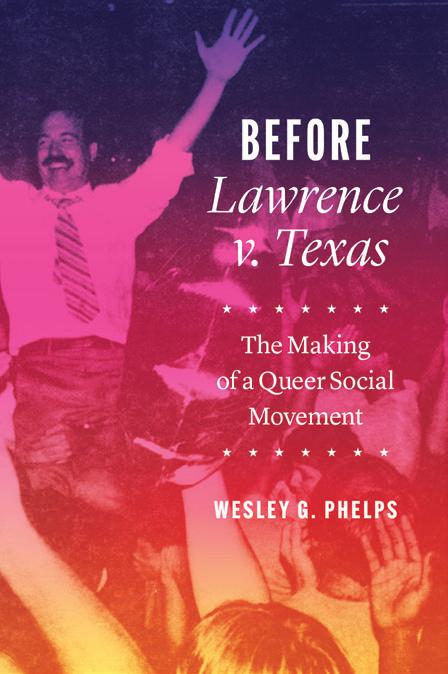

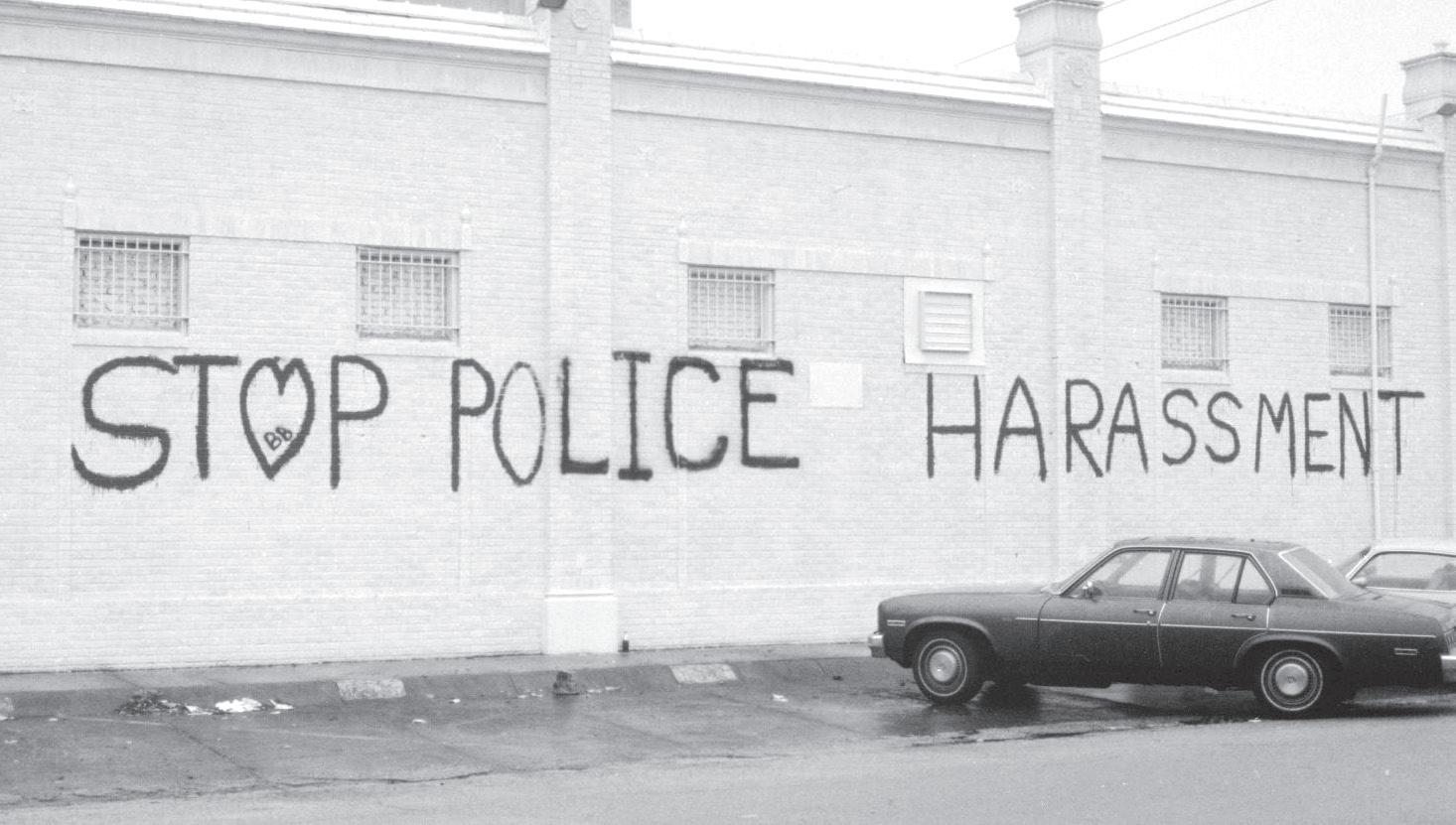

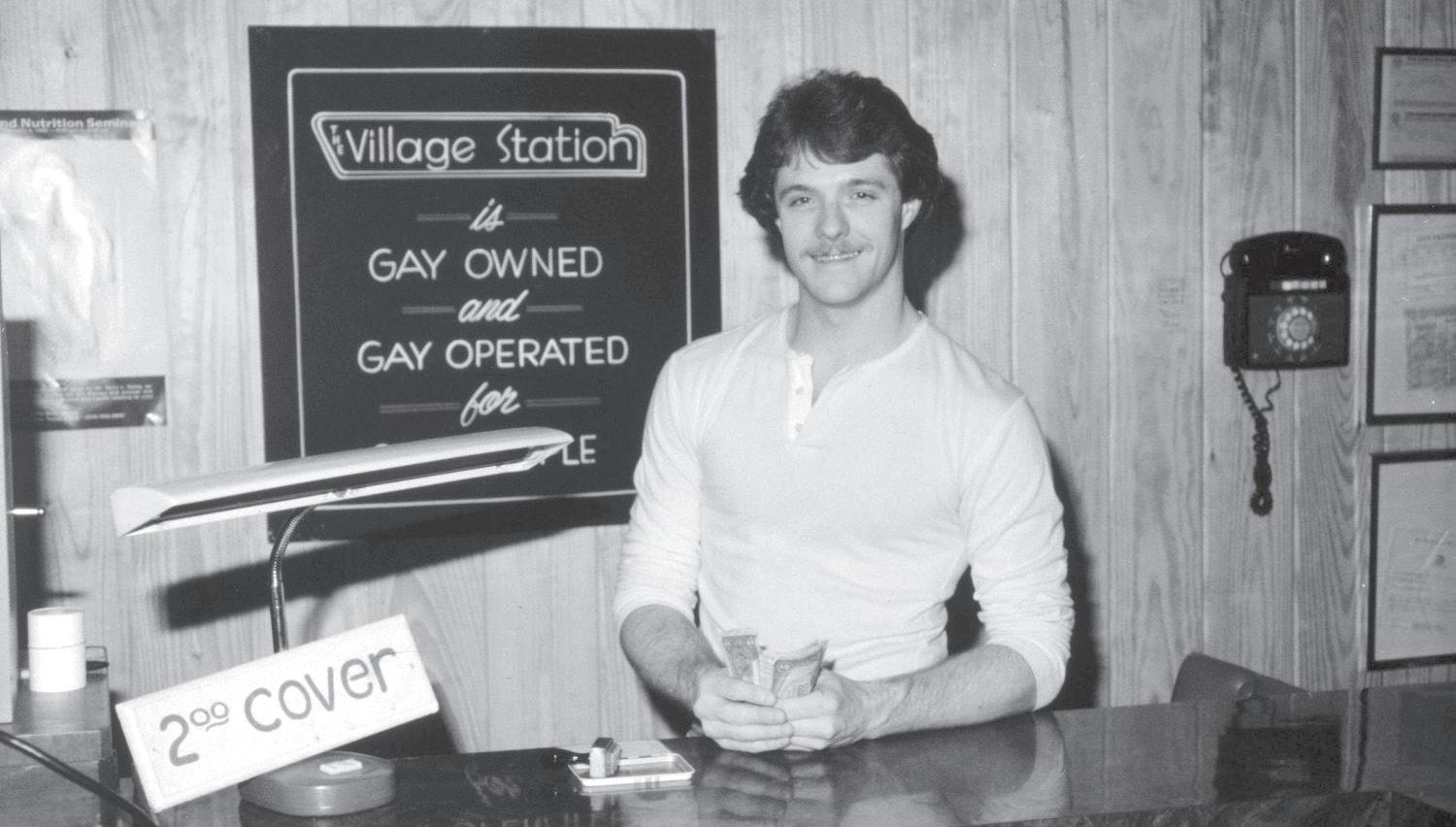

In our culture section, Contributor Roberto Ontiveros heralds the rebirth of pre-eminent Chicanx literary magazine Huizache , named for the resilient tree that grows everywhere in South and East Texas. Much as queer families are being run out of Texas by the charlatan in the Governor’s Mansion, Huizache had to flee to California to flourish. In books, Digital Editor Kit O’Connell reviews a new legal and social history of Lawrence v. Texas —the Texas-born Supreme Court case that decriminalized sodomy nationwide. In a stunning photo collection, Byrd Williams IV examines how Texas workers speak to posterity across four generations of his family of photographers.

beyond the headlines and contextualize news events. Our essays, reviews, and criticism seek to create a new cultural canon and challenge existing mythologies.

Since our founding in 1954, the Observer has focused on communities whose stories are too often ignored or poorly told.

We seek not only to inform, but to empower our readers, as we work to hold public officials and corporations accountable. Our reporters recognize that oppressed people are experts on their own lives and trust their expertise. Our journalism is factbased and rigorous, and we prize writing

that entertains as it informs. We value history as a reporting tool that allows us to interrogate the origins of policies and to correct narratives that whitewash exploitation, dispossession, and genocide. Our founding mission statement continues to guide our work.

TEXASOBSERVER.ORG |

THE TEXAS OBSERVER (ISSN 0040-4519/USPS 541300), entire contents copyrighted © 2022, is published six times per year by the Texas Democracy Foundation, a 501(c)3 nonprofit foundation, PO Box 3000, Denville, NJ, 07834-9947. Telephone (512) 477-0746. Email: business@texasobserver.org. Periodicals Postage paid in Austin, TX, and at additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER Send address changes to: The Texas Observer, 54 Chicon St., Austin TX 78702. Subscriptions: 1 yr $42. Foreign, add $13 to domestic price. Back issues $10. Airmail, foreign, group, and bulk rates on request. Microfilm available from University Microfilms Intl., 300 N Zeeb Rd, Ann Arbor MI 48106. INDEXES The Texas Observer is indexed in Access: The Supplementary Index to Periodicals; Texas Index; and, for the years 1954 through 1981, The Texas Observer Index. Volume 116, No. 1.

GABRIEL ARANA Editor-in-Chief

the “River of the Arms of God.”

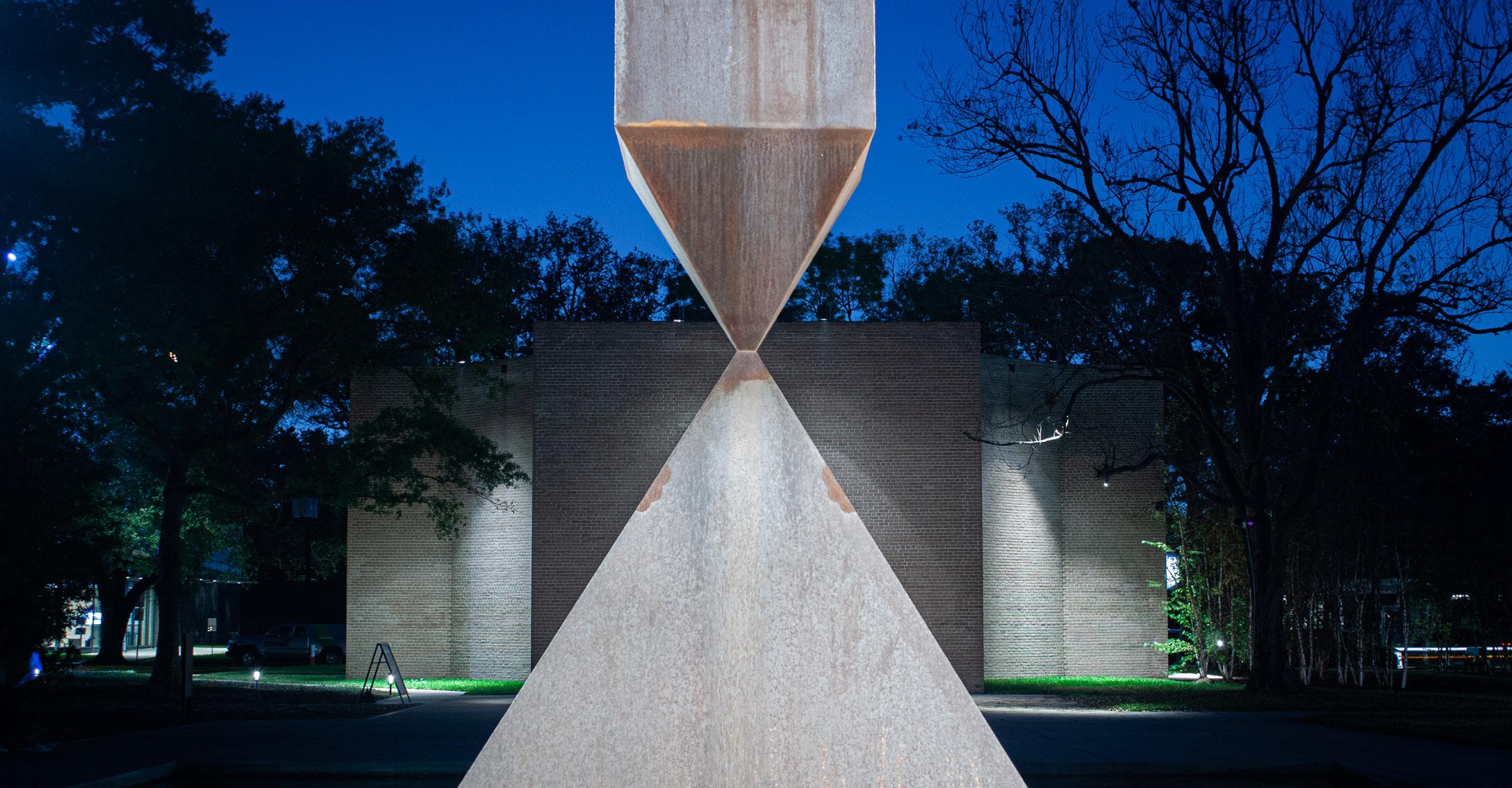

BOVA 08 STRANGEST STATE by TEXAS OBSERVER STAFF 10 PROFILE A former political operative, the owner of Tumbleweed + Sage Coffeehouse in Wolfforth discovers home is where the activism is. by ANDREW LOGAN 36 PHOTO ESSAY Across four generations, one family of photographers has captured the history of Texas workers. by BYRD WILLIAMS IV 46 POSTCARD Rothko Chapel, Houston’s 1972 temple to art and contemplation, is still revealing its magic to visitors. by ARMAN BADREI 48 REVIEW A new history of the fight to overturn antisodomy laws reveals how persecution in the Lone Star State spurred the struggle for queer civil rights nationwide. by Kit O’Connell 52 CULTURE Named for the resilient plant that grows in South and East Texas, premier Chicanx literary magazine Huizache had to flee the state to find a home. by ROBERTO ONTIVEROS 54 POEM Cold by MATT BYERS 12 The Lege 2023: Catastrophe #88 What Texas lawmakers should do to mitigate the state’s cascading crises—and what they are liable to do instead By TEXAS OBSERVER STAFF 26 32 ON THE COVER: PHOTOGRAPH BY FRED RAMOS ABOVE: MERIDITH KOHUT; MATTHEW BUSCH; FRED RAMOS

Gabriel Arana ¡Adelante!

POLITICAL INTELLIGENCE

TEXAS DEMS’ POST-BETO ERA

Who will carry the torch now that the Democratic phenom’s star has fallen?

by JUSTIN MILLER

In the fall of 2021, a national reporter from Politico was in Austin writing another profile of Beto O’Rourke as the El Paso Democrat geared up to follow a failed presidential campaign with a run for governor. The reporter asked Mayor Steve Adler whether it was a sustainable political strategy for Texas Democrats for O’Rourke to keep running for statewide office again and again—in 2022 and beyond.

“Why not?” Adler said. “Just for a while.” At the time, the logic was clear. No one else had the name recognition, the fundraising abilities, the talent, or the political will to run against the state’s incumbent Republican Governor Greg Abbott. If not Beto, then who?

But after a dismal defeat by 11 points in November, O’Rourke probably does not hold the key to breaking the Democrats’ longest statewide electoral drought in the country.

While O’Rourke helped reinvigorate the liberal cause in Texas and is sure to play a significant role in party politics going forward, it’s time to move on from the “Beto or Bust” mentality.

But who else is there? The GOP’s long domination of the state means that the Democrats’ bench is rather bare. Many of their most prominent and experienced leaders in the state Legislature or in Congress represent safe blue districts and have come to enjoy the creature comforts of incumbency and seniority—even if it’s in the marginal minority. Only in the past few years has a new generation of Democrats begun to make its mark, largely in local government, but this cohort of younger rising party stars is still largely untested and unknown.

So who will carry the torch forward? What’s the future of Democratic politics in the 2020s, not just statewide but at the local level, in the Legislature, and in Congress? The next big statewide political contest will be in 2024 against Senator Ted Cruz should he run for another term.

For years, San Antonio’s Castro brothers have been flirting with runs for statewide office without pulling the trigger. This would be the perfect time for San Antonio Congressman Joaquin, who’s thus far been second chair to brother Julián’s political career, to finally make the leap.

Colin Allred, the former Baylor football star-turned-Dallas congressman, is another possibility. While he’s kept his head down during his two terms in Congress, Allred has more recently been working to build up his statewide profile in Texas. Congresswomen Lizzie Fletcher of Houston and Veronica Escobar, who succeeded O’Rourke in El Paso, could also be contenders. The traditional incubator for political talent is at the local level, and right now that’s especially true in Harris County. There, Lina Hidalgo overcame Texas Republicans’ all-out attempt to oust her from the county judge’s

office as she narrowly defeated Republican Alex Mealer in November.

Already an up-and-comer, Hidalgo has proven able to hold her own against foes from within her own party in Houston, like District Attorney Kim Ogg, as well as top Republicans like Abbott and Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick in Austin.

That easily puts Hidalgo on the Dems’ shortlist of possible statewide candidates. Another young progressive, Harris County Attorney Christian Menefee, is also carving out a name

for himself using his post to go after corporate polluters and do battle with state Republicans.

Still, the political promise of Texas’ big cities— ostensibly the laboratories of progressive power—remains in question. In Houston proper, Mayor Sylvester Turner was first elected back in 2015 with the support of a progressive coalition. However, many of his promises have failed to come to fruition, and his office will be up for grabs in 2023.

Moderate Dem John Whitmire, who has

represented Houston in the Texas Senate for 40 years, announced his bid in December with backing from local casino mogul Tilman Fertitta and other Republican mega-donors from the Bayou City’s ruling class—most of whom backed Hidalgo’s opponent.

The 73-year-old Whitmire is a political institution and the automatic frontrunner for the mayoralty, but he won’t be uncontested. So far, there are at least two other challengers who are part of the city’s younger generation: former City Council member Amanda Edwards and former County Clerk Chris Hollins.

Up in Dallas, Eric Johnson’s tenure as mayor has been a disappointment to many progressives. He’s been divisive within city hall and has a penchant for playing footsie with Abbott. But so far, he has no clear challenger for a second term. Fort Worth remains

under the thumb of the local GOP establishment. December’s mayoral runoff in Austin was between former state Senator Kirk Watson, who was mayor once before back at the turn of the century in the early 2000s, and state Representative Celia Israel. Neither are what you’d call political visionaries.

Elsewhere in the big cities, San Antonio Mayor Ron Nirenberg was easily reelected to another term in 2021, as was longtime Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins this year. Jenkins frequently made headlines for battling with Abbott during the height of the pandemic, while Nirenberg has been a more low-key operator. Both have been eyed as potential candidates for higher office.

But with a firmly Republican-dominated Legislature that’s made a mission of restricting progressive power at the local level, ambitious Democrats in Texas are increasingly opting for the national stage.

Just a couple of years ago, Austin City Council member Greg Casar considered running for a seat in Dan Patrick’s Texas Senate; instead, he’s now headed for the U.S. House in Washington. In a punishing single term in the state House, Dallas Representative Jasmine Crockett made noise as a rabble-rouser. She also promptly opted to run for Congress, successfully winning the seat of the legendary Congresswoman Eddie Bernice Johnson. As part of the state’s freshman class in Congress, Casar and Crockett will have to cut their teeth under a new Republican majority, but they could be important figures in the House’s growing Progressive Caucus—and part of Democratic Party’s long-term future back in Texas.

Of course, it’s quite possible someone else—currently off the state’s political radar—will become the next beacon of hope for Texas Dems. Part of O’Rourke’s fleeting success was that no one saw him coming. He emerged into political celebrity from obscurity, famously jumping into the 2018 U.S. Senate race with little support from traditional party apparatchiks while snubbing his nose at conventional campaign wisdom.

O’Rourke rewrote the playbook for how to run, if not win, in Texas. Now, some other fresh face needs to figure out how to get over the top.

LOON STAR STATE

2 TEXAS OBSERVER TEXASOBSERVER.ORG | 3

BEN SARGENT’S

AUSTIN

DON’T LIKE TEXAS POLITICS? WAIT FIVE MINUTES

by ERNIE MORÁN

by ERNIE MORÁN

Watching the national media’s reaction to last fall’s midterm elections made my head spin. While the cable news pundits and legacy media headlines spoke of the failure of a “red wave” to materialize, we here in Texas had to swallow the fact that our neighbors had chosen to reelect a governor who took no meaningful action to shore up our energy infrastructure after more than 200 fellow Texans died in an ice storm; who made guns easier to carry after the mass shootings in Sutherland Springs, at Santa Fe High School and the El Paso Walmart and leading up to the Uvalde elementary school tragedy; and whose version of “securing the border” meant sending busloads of migrants to faraway states with false promises. Oh, and we also reelected an attorney general who’s been under indictment for the past seven years.

And in Tarrant County, where I live, Tim O’Hare was elected county judge. As a Farmers Branch city councilmember, he had tried to make it illegal for undocumented persons to work or even rent a place to live. In the GOP primary, he won by running to the right of a conservative and popular former Fort Worth mayor.

It reminded me of how I felt in the summer of 2020, when two years of activism on the part of myself and hundreds of others in Fort Worth seemed to have done nothing for those we were trying to help. But it also made me want to tell people what I’ve been doing here in North Texas rather than throwing in the towel.

In May 2018, as the Trump administration’s policy on family separations at the border took shape, I led an effort to get my representative in Congress to halt it. As the son of immigrants and a bilingual teacher, I care deeply about the issue.

U.S. Representative Kay Granger, a Republican in Congress since 1997, had worked her way into senior leadership positions on various committees and task forces. I felt if anyone was going to be able to get the White House to listen to our pleas for humanitarian action, it would be her.

I started a weekly sidewalk protest near her office that grew from six people to a couple dozen, then 40, then 80. The press covered our actions and more people joined each week, culminating in more than 200 protesters during the week of the Texas State Democratic Convention that June. It was remarkable to get that kind of consistent turnout in Tarrant County, where for decades Republicans have run unopposed in far too many local races. We kept at it for two more years. But then we had to stand down. The COVID outbreak made it too dangerous to get together in such groups, and our numbers dwindled. We faced a heartbreaking reality: All those hours of trudging up and down in all weather, visiting her office and logging our complaints with her staff hadn’t reunited a single child with their parents nor

nudged Granger into action.

What’s more, by 2020, progressives and people of color in Fort Worth were seething over two police abuse cases that seemed to show nothing had changed here, including one in which a black woman, Atatiana Jefferson, had been killed by a police officer responding to a request for a wellness check at her home. Then came the murder of George Floyd in Minnesota, and the Summer of Justice, and protests through downtown Fort Worth, outside City Hall, and in the popular West 7th Street district. By the end of that summer, I knew I had to do something

beyond marching in the streets. I wasn’t ready to give up fighting for real change in Tarrant County.

About that time, a young science educator and nonprofit leader named Jared Williams announced his candidacy for Fort Worth City Council in my district in southwest Fort Worth.

Donald Trump won a little less of the vote in my precinct in 2020 than he did in 2016: 49 percent to 54 percent. But John Cornyn won reelection to the U.S. Senate with 52 percent of the vote in my precinct, and Granger took 54 percent on her way to another term.

My precinct is not blue.

So I reached out to Jared directly and offered to volunteer for his campaign. That’s where I thought I could have an impact on my community: the city council race in my district.

Over the next several months, we phone banked, we texted voters, and we knocked on doors—virtually every door in the district.

Despite being outspent 4-to-1, we forced a runoff in the three-way general election.

So we kept knocking on doors and calling and texting voters. And despite being outspent 6-to-1 in the month leading up to the runoff election, we finished the job and made a little Fort Worth history, unseating 16-year incumbent Jungus Jordan and electing the first person of color to the District 6 seat in the city’s history.

Elsewhere, Tarrant County has become ground zero in the school board culture wars. Opponents of racial and gender equity work, backed by the resources of political action committees, have gone after superintendents, school board trustees, and teachers who seek to improve policy and curriculum for underrepresented students. They have organized and drawn media attention—at times flattering coverage. These PACs are laser-focused on school boards.

But while awful things have happened in Southlake and Grapevine, to say nothing of some rural school districts in neighboring counties, the Fort Worth Independent School District has held steadfast in its commitment to equity work, replacing its ousted superintendent with one who has a track record of championing such work.

That is due in no small part to the support that citizens showed for those values through emails to trustees and speaking up at forums and school board meetings.

The ultimate takeaway for a progressive such as myself—a husband, dad, teacher, and advocate—is this: In order to create the world we want, the one we envision, we have to find allies and encourage them to get in the fight. Right here, where we live.

Our efforts can’t be limited to complaining on our social media accounts. If you have the means financially, pick a candidate or cause and support them. Donating has never been easier. Make regular contributions every few weeks.

If you can’t give money, find time to devote to the candidate or cause. Get involved. Stay involved. Go to city council meetings or school board meetings. Sign up to speak or give words of support to those who do. Write your local leaders and tell them what matters to you, how you want them to govern. Make these things part of your weekly or monthly routine.

Little by little, we’re making it happen in Fort Worth with small victories. Doing that across the state, we could build a Texas that is a model of progressivism for the nation. If that sounds unlikely, remember that nothing in Texas politics should be taken for granted. The Republican margins of victory in Texas are getting smaller. Democratic strength is growing in many major cities.

This is the struggle of our lives. We have to spend our lives winning it.

4 TEXAS OBSERVER TEXASOBSERVER.ORG | 5

EYE ON TEXAS DALLAS

Ernie Morán is a public school teacher and campaign volunteer. He lives in Fort Worth.

Or, better yet, try for change. It worked for this North Texas activist.

Illustration

Credit: Ivan Flores, Gus Bova, AP Images

THE OPPOSITION

San Antonio political pugilist Trey Martinez Fischer will lead the state House Democratic caucus in yet another bleak year.

For what feels like the hundredth year running, Democrats in 2023 will hold no positions of structural import in Texas state government. As such, the party is left only to decide what sort of opposition it will be—loyal or defiant, supplicant or obstructionist, scheming or strident? Enter Trey Martinez Fischer.

On December 7, House Dems elected Martinez—who’s served 10 terms in the lower chamber representing a majorityLatino swath of San Antonio—to chair the party caucus in the 88th legislative session. Martinez beat out Austinite Gina Hinojosa along with Williamson County Representative John Bucy, who withdrew before the vote. Over two decades, Martinez has established a reputation as a legislative brawler, unafraid to derail GOP bills with aggressive parliamentary maneuvers. He will succeed Chris Turner, an Anglo lawmaker from a diverse chunk of Tarrant County, and will inherit a Democratic caucus that’s shrunk to 64 members (out of 150) following the loss of three Hispanic-majority seats since 2021.

The Texas Observer spoke with Martinez about life in the minority, quorum breaking, and democracy.

TO: How did the caucus vote go down? There is nothing more humbling than to be evaluated by your peers. This is the ultimate job interview. And we had fine candidates.

I’m a huge fan of Gina Hinojosa. We’re partners. We’ve worked very well together. John is a younger member who has really come a long way in a short amount of time, and everybody ran a good campaign. This wasn’t a campaign based on ideology or one camp versus another. I mean, relationships are very personal in the Texas House.

If you think about it, we don’t have any statewide officeholders. When it comes to being the front line for the Democratic Party across the state, we are it, and we are the closest folks on the ground. We represent the smallest districts. So we’re in the proverbial foxhole, and when you’re in a foxhole fighting a battle for progressive principles, you want to know who

you’re in that foxhole with. And so I think this race was, you know—we clearly need a fighter.

Did it come down to a sort of “San Antonio versus Austin, which city has the better tacos” debate?

You’re damn right it was a taco debate, man—it was like come and take it, man. No, look, again with John out of the race my heart was warm because I knew that Gina and I work very well together, and nothing would make me more proud than to be by her side, letting her lead. And then, of course, I felt that if I was at the helm, I would bring just a few more years of experience and a few more battles that I have been tested in.

How would you rate House Democrats’ effectiveness as a minority over the last 15 to 20 years?

You always have to improve. You can always do a better job. So people think and believe that Leader Turner and I don’t get along. We actually get along fine. We have

a different style, and we have different tactics. But Chris worked very hard for this caucus and really has built it up to a level that it’s performing as one of the best caucuses I’ve seen since we’ve been in the minority.

What’s that stylistic difference between you and Turner?

Just the way we engage, how we approach legislation, how we build coalitions. I’ve got nothing critical [to say]. Chris did a good job. Chris left everything on the field. But we are very different. We come from different places. I’m a Latino from inner-city San Antonio. So my life experience is much different from his.

Democrats fled Austin to D.C. in 2021 to try to stymie voter suppression legislation, but the bill ended up passing anyway. So was that quorum break successful?

I think it was. Number one, if you just look baseline, they changed the freaking legislation. So for those who say we should just sit at our desks

and take our medicine, we would have had one of the crappiest voter suppression bills in the country. And we would have done nothing other than give speeches and push [voting buttons] to change that. Walking out and telling people that we’re not going to take that BS, and identifying real problems publicly that they knew privately, forced them to change. And so I know now we can have a “souls to the polls” program

Would you consider the tactic again? And if so, what would your red line be?

You know, they have this saying about Fight Club that the first rule to it is that you don’t talk about it. So I don’t talk about what I’m going to do or what I’m thinking. But you’ll know when the time comes.

In the November election, there were two House seats, HD 118 in San Antonio and HD 37 in the Cameron County area, that were winnable seats for Democrats. Republicans won them both by three points. And the Democrats were outraised financially. I don’t hear Democrats really talking about why these winnable Latino-majority seats were lost.

I like: Every single day, this state changes. Every single day somebody turns 18 and is eligible to vote. And those people who are turning eligible to vote are a very diverse group. So where we go forward for the next 10 years, I’m very bullish about that for Texas Democrats.

What is the path back to a House majority and how long will it take?

because they had to answer to the public about that. And taking it a step further, [we went and told] our friends in Washington to proverbially get off their ass and get to work. I think that meant something. Even to this day, you hear the president talking about our democracy being under attack and the need to have new voting rights, and I think that we contributed to that.

You know, I don’t know that I’ve ever been asked. A lot of us worked very hard in San Antonio. That district [118], you need to know, was strategically drawn to guarantee a Republican outcome.

It was still winnable for Democrats.

I mean, it’s easy to say, sitting on this call, you and I. Let’s talk to Frank [Ramirez, the Dem candidate] about that, who did all the hard work. But your point is well taken. There are seats out there that are competitive, no doubt about that. That being said, here’s what

With partisan gerrymandering and with a partially functioning Voting Rights Act, it is really hard to have justice for redistricting purposes. It’s very difficult for districts to be drawn fairly and respect communities of interest and the voting rights of minorities. Technology has done a lot to really draw districts to maintain political majorities. And so it’s hard to win those fights. But I think the number-one strategy is to not give up. I think the number one goal of Republicans in this state is to force us to wave the white flag. And we’re not going to do that. If you have the ability to fight, you have hope. I’ll take those two things over anything else when it comes to rebuilding our party, rebuilding our brand, and taking back our majority. So I’m gonna start with those.

6 TEXAS OBSERVER TEXASOBSERVER.ORG | 7 THE

AUSTIN

INTERVIEW

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

INTERVIEW BY GUS BOVA

Representative Trey Martinez Fischer speaks outside the Texas Capitol.

Credit: Eric Gay AP Images

EL PASO

UPS has thrown the higher education plans of dozens of El Paso High School students into disarray. The young people had just taken the SATs and handed their answer sheets to school officials, who handed them to UPS. En route to the College Board, the papers flew out of an unsecured truck. UPS and the school district salvaged most of the exams, NPR reported, but 55 unfortunate students’ work was lost to the wind.

AUSTIN

The unreliable Texas grid could not stop one man’s pursuit of reliable family planning. When his urology clinic suddenly lost power, Dr. Christopher Yang thought he would have to cancel a patient’s impending vasectomy. But a staffer reminded the doctor about his brand-new electric truck parked outside. WGLT reported that Yang ran an extension cord out to the vehicle, which had plenty of battery juice to power a cautery device for the 15-minute procedure.

Lynne Dobson & Greg Wooldridge | Dale Linebarger | The McHam Project

Abby Rapoport | Ron Rapoport | Alec Rhodes

Gabriel Arana & Michael Collis | Beatriz Pérez & Vincent LoVoi | Abi Mallick | Peggy & Matt Winkler

Carol M. Barger | Carlton Carl Lois Chiles Marian & Paul Cones| Roxanne Elder & Scott Borders

Kyle & Noah Hawley | The Neavel Family | Janis & Joe Pinnelli

Cathy Brown Brownstein Family Foundation | Lon Burnam | Lize Burr & Chris Hyams | Ted Chauviere

Consuelo Duroc Danner | Mandy Dealey | Anne Dobson Edward Espinoza Bob Frump | Cheryl & Jim George | Clint Hackney Danielle Hayes | Sarah Heather | Laura Hernandez-Holmes | Charlotte Herzele MEd, PhD, MPH | Tom Houseman |

David Kanin | Sissy & Denny Kempner | Chula Sims & Dick Lavine David Lee | Siobhan & Greg LeRoy | Susan Longley

TERLINGUA

An opportunistic black bear has been helping itself to leftovers in dumpsters outside a barbecue joint and a taqueria, leaving steaming scat behind. Neither noise from business owners nor rubber bullets from a sheriff’s deputy have deterred the ursine gourmand, so state officials have resorted to shooting the poor creature with paintballs, reported the Big Bend Sentinel . Black bears, extirpated from the area decades ago, returned to Big Bend country in the 1980s.

SAN ANTONIO

A debate over energy efficiency and equity in the nation’s seventh-biggest city was derailed by the siren call of petty drama. In September, City Councilman Mario Bravo publicly berated council colleague and exgirlfriend Ana Sandoval for disagreeing with his suggestion to use public utility revenue to weatherize low-income homes, saying her lack of support showed why he broke up with her. Bravo brought his parents and current girlfriend to defend his character. Unmoved, the council voted to censure him, according to the San Antonio Report

Cari Marshall & Eric de Valpine | Lynn & Tom Meredith | Marie Moore Peter Petkas | Jim Philips John Shockley

Pat & Bud Smothers Blaine Wesner | Charles Zeller

Margaret & Robert Ayres Donna Bolding & Roger Hamilton | Rodney Brown Sarah Buttery & Greg Sheff | Diana & Kevin Callaghan

James Canup Andy Carson Kristen & Rick Casey

David Claunch A. Colby | Kate Donaho | Thomas Doneker

Pam & Hal Fuson Michael Hershey Andrea Klose | Virginia Marshall John B. McFarland

Robert Mennel Celina Montoya | Barbara Moscher Allison Orr Jill Runyon

Rhetta van Auken Kathleen Watkins Wright Williams

Our generous supporters listed above believe, as we do, that a free press is imperative for a functioning society, and that the Observer is a critical component of that. If you feel the same and are interested in giving $ 500 or more annually, or would like to learn more about our Free Press Circle, which gives donors the opportunity to provide the Observer strategic, stable funding with a three-year commitment pledge, email James Canup at canup@texasobserver.org.

8 TEXAS OBSERVER STRANGEST STATE NOTES FROM FAR-FLUNG TEXAS by TEXAS OBSERVER STAFF ILLUSTRATIONS: DRUE WAGNER

JANUARY/FEBUARY 2023 BROKEN PROMISES By JOHN WASHINGTON ANNA-CATHERINE BRIGIDA CATASTROPHE #88 By TEXAS’ “RED WAVE” By ERNIE MORÁN BREAKING THE BRAZOS By KATHRYN JONES The Biden Administration is still separating immigrant kids and their families.

T H I S IS S UE M A D E P O SSIBLE I N P A R T BY S U P PO R T FROM :

DESTINY’S DESTINY

She left her conservative community to make a difference, only to find she could make the biggest impact at home.

by ANDREW LOGAN

Photography by SHELBY TAUBER

When the U.S. Supreme Court overturned almost 50 years of legal precedent last June by stripping away the constitutional right to abortion, Destiny Adams was horrified. She foresaw devastating consequences for her community in Wolfforth, a tiny West Texas suburb of Lubbock with little access to contraception. She couldn’t stand by and do nothing.

“Women that aren’t prepared to have a child should have the right to say, ‘Hey, I can’t give this child the best life it could have. I need an abortion,’” Adams told the Texas Observer. “It shouldn’t be anyone else’s choice except for the mother.”

At Tumbleweed + Sage Coffeehouse, the bustling little shop Adams owns across the street from the Frenship High School football stadium, she started distributing free reproductive kits including Plan B pills, pregnancy tests, condoms, and informational pamphlets. In response, conservative members of her community have protested at her store, called the police on Adams, and are organizing to change city laws to stop her advocacy. “Initially, I was scared,” she said. “I’m putting my business and my livelihood on the line to help others. Was it really worth it?”

Adams says she’s not a troublemaker. She just wants to create a safe space for people who might otherwise feel alienated in her conservative, rural town. As the Observer previously reported, Tumbleweed + Sage hosted the first drag queen story time in Wolfforth last summer, sparking what the local police chief said was the only protest he’d seen in the city in three decades.

Before opening Tumbleweed + Sage in June 2020, Adams—a Lubbock native—had left her hometown to travel with her husband, Cole Adams, fighting for health care reform, civil rights, and women’s equality. For six years, she labored as a field director for the Texas Democratic Party and as an organizer for the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee. The chaotic world of political activism was invigorating, but eventually the pull of family became overwhelming.

“Our parents were getting a little bit older,” Adams said. “My mom had health issues, and I wanted to come home and be with her.”

Having given up their political aspirations, the couple returned to Lubbock. As they evaluated their career options, they knew they wanted to do something that made a difference. Inspired by the sense of community in the local coffee shops they’d frequented on the campaign trail, Destiny

wanted to provide an accepting and inclusive space in her own hometown.

Tumbleweed + Sage opened for business three months into the COVID-19 pandemic. During its first year, the coffee shop offered only drive-through service. When the location finally opened its doors to the public, it hosted quirky, pop culture-themed events—Harry Potter Movie and Trivia Night, Mean Girls Shop Takeover, Twilight After Hours PJ Party, etc.—along with accompanying specialty drink and pastry menus.

”We’re a true mom and pop shop. You get what you get when you come here because it’s a resemblance of me and Cole,” Adams said.

The shop’s events also reflect the Adamses’ past as political activists. Despite the public outcry, Tumbleweed + Sage has continued to host drag events in recent months. And so far, they’ve distributed around 150 free reproductive kits, which are provided by Jane’s Due

Process, a nonprofit organization that helps teens access reproductive health services.

The backlash from conservative members in the community has been swift. Phone calls flood the office line so often that Destiny rarely keeps it plugged in, and protesters have held demonstrations outside of the shop. But Adams is resolute: “To enact change you have to make people feel uncomfortable,” she said.

Even though Adams is not breaking any laws by providing over-thecounter contraceptives, right-wing evangelicals are organizing to take drastic measures against her. Mark Lee Dickson, the radical anti-abortion advocate who lobbied for Lubbock to become a “sanctuary city for the unborn,” led a recent meeting at Flatland Bible Church in Wolfforth to discuss how to draft city ordinances to prevent the activism at Tumbleweed + Sage. The first ordinance discussed would ban the distribution of Plan B by anyone in Wolfforth. The second would ban all-age drag queen story times unless the venue hosting them is licensed as a sexually oriented business.

“We don’t want [Tumbleweed + Sage] to go out of business, per se,” said Jim Baxa, president of West Texas for Life, who attended the meeting. “We want them to repent, and we want them to stop doing the evil deed [of providing Plan B] and just provide coffee.”

Others in the community, meanwhile, note how important access to free contraceptives is, especially in a city like Wolfforth, where Adams said Plan B is not available in any store. When Evangelina Zubia—who attended high school in Lubbock—became pregnant at age 16, she was afraid to ask her mother for help. A cousin gave her the information for Jane’s Due Process, which provided Zubia with the same reproductive kit that Destiny distributes.

“It was really comforting to just know that someone’s putting in the effort to make sure that I don’t have to deal with teen pregnancy in the state of Texas. It made me feel like these people have my back,” said Zubia, now a first-year student at Texas Tech who volunteers for Jane’s Due Process as a reproductive kit deliverer, occasionally refilling the kits at Tumbleweed + Sage. ”At the end of the day, the most meaning we’re getting from this is that we’re educating our community and actually providing a service that is truly needed,” Adams said. “Yes, you can get free Plan B here. Yes, you can get free condoms here. Yes, you can get high quality coffee and pastries here. We’re just like the cool, big cities but in the middle of two dirt fields.” However, Adams’ advocacy has taken a personal toll. After she and Cole hosted the first drag queen story time event, Cole’s parents severed ties with them. “I almost got blindsided by it all. It was really depressing and really hurt my feelings,” he said.

Despite the personal ramifications and community backlash, Adams said there’s been an overwhelming swell of support too, and she has no plans to slow down.

“When I came home, I realized ... the right answer is to stay at home and actually enact change in a place I actually care about,” Adams said. “I know about the history. I know the people’s stories from here. I could have gotten more done here than I could have in politics ever. And I can see the people that it actually affects.”

10 TEXAS OBSERVER TEXASOBSERVER.ORG | 11 PROFILE LUBBOCK

Bottom: The reproductive health kits available at Tumbleweed+Sage include Plan B pills, pregnancy tests, condoms, and information.

Top: Destiny Adams now works on progressive causes from her Wolfforth coffeehouse.

Andrew Logan is a writer and producer based in Austin.

B reaking B razos the

is straining the “River of the Arms of God.”

Editor’s note: This is Part 2 of “Drifting Toward Disaster,” a Texas Observer series about challenges facing Texans and their rivers.

Development

By

Kathryn Jones

Photography

By Meridith Kohut Nick

Dornak, president of the nonprofit group Friends of the Brazos River, canoes the John Graves Scenic Riverway with his 11-year-old daughter Emery.

Few rivers can claim as strong a connection to Texas’ natural and cultural history—and its very identity—as the Brazos.

It drains the second-largest river basin in Texas, meandering for 840 miles from the Llano Estacado near Lubbock, cutting across prairie and limestone hills to woodlands, through farms and ranches, cities, towns, and coastal marshes before finally merging with the Gulf of Mexico south of Freeport’s giant petrochemical plants.

Spanish explorers named it Los Brazos de Dios, “the Arms of God,” because of the river’s many tributaries and lifesaving waters. Texas’ first capital, when it was a colony authorized by the Spanish government, was founded on the Brazos at San Felipe de Austin. When it won its independence and became a short-lived republic, Texas established its capital at Washington-on-the-Brazos. The river has inspired poetry, art, and music. Perhaps most importantly for the Brazos’ own survival, it inspired an enduring book.

Fort Worth native and author John Graves wrote Goodbye to a River about a three-week canoe trip he had made on the Brazos in fall 1957. He wanted to memorialize the river he had hunted, fished, and paddled before it could be changed forever by a string of dams that had been proposed from Possum Kingdom to Whitney. Graves wrote of the beauty of the free-flowing river; the stories of the Comanches and Anglo settlers who had lived on its banks; and even mentioned the encroachment of industry in the form of a gravel pit.

The book—still in print since its publication in 1960—sparked a conservation movement and helped lead to the abandonment of plans for all but one of the downstream dams. In 2005, the Texas Legislature created the John Graves Scenic Riverway on the segment of the Brazos from below Possum Kingdom Lake to just above Lake Granbury and gave it stronger protections from rock mining.

The legislation tightened rules so that any quarry operating within a mile of the river must obtain a special permit. It banned new quarries or expansions located within 200 feet and those between 200 and 1,500 feet of the river unless they could

meet specific criteria set to control erosion and protect wildlife habitats. The criteria also required a reclamation plan and the use of best-available technology.

Many quarries shut down as a result of the new restrictions, but tourism has flourished. Thousands of people a year kayak, canoe, fish, and swim in one of the state’s most picturesque stretches of river, framed by high rocky bluffs.

However, the rules that created the riverway are set to expire in 2025 unless activists can convince the Legislature to renew them. In the meantime, a much tougher fight faces the Brazos—and not just on the scenic section.

That’s the Gordian knot of development in the Brazos basin. Urban, suburban, and industrial growth is creating everincreasing demands on the Brazos’ finite supply of water. It’s also adding to pollution as cities, farms, ranches, and industrial complexes return the Brazos’ water—sometimes clean, often polluted—to the river once they’ve used it for drinking, cooking, cleaning, raising livestock, watering crops, lightcommercial to heavy-industrial processes, recreation, and watering hundreds of thousands of lawns.

And, as the federal Clean Water Act turns 50, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) is again taking fire from various directions for not better protecting the state’s water resources. A staff report by the Texas Sunset Advisory Commission this year called TCEQ commissioners “reluctant regulators.” In 2021, more than 20 environmental groups filed petitions asking the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to force Texas to fix its “broken” water system and accused the state agency of giving developers and other polluters a “green light to a huge contamination” of Texas’ public waterways.

Throughout Texas, more than 460 stream segments are classified by TCEQ as “impaired,” meaning they fall short of water quality standards because of pollution. Of those, 75 flow in the Brazos River Basin, which has more impaired streams than any other river basin in Texas. The reasons those streams are classified as impaired, according to TCEQ, include too much bacteria in the water,

14 TEXAS OBSERVER TEXASOBSERVER.ORG | 15

A man fly fishes with his dog in a segment of the Brazos River named the John Graves Scenic Riverway, protected from mining by the Texas Legislature in 2005. Those protections are set to expire in 2025.

toxic sediment, excessive algae growth, impaired fish communities, and mercury found in edible tissue, meaning in fish or shellfish.

Alex Ortiz, an attorney and water resources specialist for the Sierra Club Lone Star Chapter, said the Brazos—and other Texas river basins for that matter— are “really strained. They’re under a lot of pressure from pollutants that really don’t have the regulatory oversight the Clean Water Act intended.”

That strain shows in once-clear parts of the Brazos now muddy with sediment, its flow interrupted by islands of sand and vegetation. It shows in massive fish kills, especially during periods of drought such as one that occurred in Lake Granbury in 2011 and one in 2022 around Waco. It is evident in numerous algae blooms in the middle Brazos around Glen Rose, and one in 2021 at Belton Lake that produced toxins strong enough to kill several dogs that drank from it. It shows in more than 60 segments of the river basin considered too polluted for safe swimming, boating, and other recreational uses.

These days, protecting the Brazos is an uphill struggle against powerful industries,

monied developers, and expanding cities that view the river as a natural resource to be exploited. The Texas Water Development Board estimates that by the time the Brazos reaches the Gulf, it has served almost 4 million Texans who need water for their daily lives, homes, businesses, industry, and agriculture.

As Texas’ population continues growing, the bottom line is, “How much can the river take and absorb?” said Nick Dornak, president of the nonprofit group Friends of the Brazos and director of watershed services at Texas State University’s Meadows Center for Water and the Environment. “That’s the question, because I feel like the Brazos, like so many rivers in Texas right now, is at a potential breaking point.”

The Brazos’ beginnings in some way presage its current problems: human habitation, mining, many-timesused water. It starts in the high, dry plains of the New Mexico-Texas border, where the land drains into draws that eventually create the Brazos. There, between Portales and Clovis, lies one of the most significant sites of

early human occupation in North America: Blackwater Draw, the uppermost tributary of the Brazos, which flowed in the ancient past but went dry as the climate changed thousands of years ago.

After unusual, fluted projectile points— now called Clovis points—were discovered there in 1929, archaeologists arrived and uncovered animal bones and artifacts showing that humans had lived in North America as far back as the Ice Age 13,000 years ago, hunting animals like bison, mammoth, and ground sloths.

The Clovis discoveries eventually put a stop to gravel mining that had been going on there since the 1920s. The federal government stepped in in 1982 to protect the draw as a National Historic Landmark. The draw runs north of Lubbock to Yellow House Canyon where the North Fork of the Double Mountain Fork of the Brazos begins. Here, effluent discharged from wastewater treatment plants in Lubbock County contributes to the river’s flow.

The Brazos’ main stem begins downstream in Stonewall County near Old Glory where the Double Mountain Fork meets the Salt Fork, so named for its

TEXASOBSERVER.ORG 17 16 TEXAS OBSERVER

Dornak says he fears the Brazos “is at a potential breaking point.”

Possum Kingdom, a water supply lake, has been affected by drought. State officials fear water shortages will grow all along the Brazos.

18 | TEXAS OBSERVER TEXASOBSERVER.ORG | 19

Drought conditions expose the red soils derived from Permian deposits that line the river bottom near the source of the Brazos River, where the Salt Fork joins the Double Mountain Fork.

natural salty quality. The river picks up the Clear Fork in Young County and heads south to Palo Pinto County, site of the basin’s first dam at Possum Kingdom.

The Morris Sheppard Dam was built in 1941 for hydroelectric power, water supply, and recreation. The dam held back silt from upstream runoff so the Brazos below the dam ran crystal clear and drew people to its scenic beauty.

By the dawn of the 21st century, however, those who lived near the Brazos in Palo Pinto and Parker counties noticed the river’s quality was deteriorating. After heavy rains, tons of dirt and clay surged down the river, threatening fish and wildlife habitats. The once free-flowing Brazos turned shallow and brown, and sediment formed islands of silt overgrown with vegetation like cattails and weeds.

Residents complained that fish were disappearing. The white sandy beaches and blue waters were replaced with thick, brown mud and tea-colored water. Much of the mud was coming from illegal quarries mining stone for building purposes.

Tiffany Malzahn was the Brazos River Authority’s (BRA) upper basin environmental planner. She was working in the field when she witnessed quarry miners dumping what they didn’t want into the river. “I observed some [mine workers] taking those layers and just shoving those materials into the riverbed,” recalled Malzahn, now the BRA’s environmental and compliance manager.

Concerned residents banded together to form the nonprofit Brazos River Conservation Coalition. They asked TCEQ for help, but nothing much happened until Walmart heir Alice Walton, who owned a Palo Pinto County ranch along the Brazos, got involved. TCEQ sent inspectors into the county and shut down a quarry for stormwater violations. Other quarries closed.

In 2004, TCEQ launched a statewide “Clear Streams Initiative” that enforced quarry regulations, examining 316 sites in 62 counties and even using helicopters to inspect remote areas. Inspectors found dozens of mines operating without permits. The investigations resulted in 128 notices of violations (most of them for construction sand and gravel operations), 38 notices of enforcement, and more than $1 million in penalties. Six cases were referred to the attorney general

for prosecution. The AG’s office issued temporary restraining orders against three quarries, prohibiting discharges, and two temporary injunctions requiring modifications to plant sites; another quarry shut down.

A year later, the John Graves Scenic Riverway was created and a pilot program was launched by TCEQ and other state agencies to respond to citizen concerns about water quality.

“Closing the hole in the regulations and the permitting process that came out of it have been the greatest successes” of the scenic riverway legislation, Malzahn said. “The strongest thing was stopping the bad actors.”

TCEQ currently lists six pits operating under general permits in the John Graves Scenic Riverway. At times, facilities have applied for the more stringent individual permit and then withdrawn because they could not meet the requirements.

The scenic riverway designation was significant because it set a precedent for future river protections, Dornak said.

“While it wasn’t easy and has not been easy to duplicate, it showed what can be done when stakeholders stand up and work together to protect critical lands and waters,” he noted.

The result is visible—clearer water that has made the John Graves Scenic Riverway one of the state’s most popular areas for canoeing, kayaking, and fishing.

It’s a different story downstream where the Brazos doesn’t have the same protections from mining.

East of Glen Rose in Somervell County, a sand mining pit operated by minerals and materials giant Covia Holdings Corp. racked up 19 permit violations from 2013 to 2019, according to EPA data. Most were for exceeding the amount of total suspended solids discharged. Total suspended solids are a concern with mining facilities, TCEQ has said, because excess sediment can destroy aquatic habitat.

Also east of Glen Rose, the MW Ranch, where for years Friends of the Brazos held annual fundraisers, has leased part of its property to Vulcan Materials Company, the nation’s largest producer of construction aggregates, to crush rock several hundred feet from the Brazos. Worried residents formed a group called SCRAM—Somervell

County Residents Against Mining—and protested, but by March 2020 the rock crushing operation was up and running.

Ralph Hawkins, a Dallas architect who has been involved with SCRAM, bought land adjacent to MW Ranch where he lives part time and raises hay along the river. TCEQ required only an air quality permit for the MW Ranch mining site, but Hawkins objected that the site was within the Brazos floodplain and wetland areas that potentially could pollute the river. TCEQ’s response was that “issues regarding water use, water quality, or water availability are not within the scope of this permit review.”

“I would absolutely think they need a stormwater permit,” said Dornak, whose family owns property nearby on the Brazos. “At bare minimum.”

SCRAM’s research found that 60 percent of the river in Somervell County had rock crushing, sand, or gravel operations. TCEQ said it cannot limit the number of surface mines or deny an air quality permit application as long as it meets rules and requirements.

“There’s so much history with the Brazos and to have so much of it being excavated … it’s really kind of sad to see such a recreational draw for Somervell County be treated like that,” Hawkins said.

Sorrow for what has been happening to the Brazos and rivers in general resounds in Don Henley’s song “Goodbye to a River,” released on his 2000 solo album, Inside Job. It’s a collective, universal cry against “killing everything divine.” The captains of industry, Henley sings, “Put that river in a box/ Well, it was running wild/And men must have control.”

That control takes the form of dams and 11 reservoirs that make up the Brazos River Authority’s water supply system and another eight owned and operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for flood control. The BRA, established in 1929 as the first state agency in the United States to develop and manage water resources for an entire river basin, leases water supply storage from the federal reservoirs.

Already, the demand for water in the Brazos basin is exceeding the estimated supply in some areas. In less than 20 years,

demand is expected to outpace supply along the whole river.

At the same time, drought is having a palpable impact on the Brazos watershed.

In November 2021, the basin’s reservoirs were collectively almost 94 percent full. A year later, they were about 72 percent full, according to data from the Texas Water Development Board.

The biggest supply pressure in the future won’t come from industry, but from cities and towns. Lubbock, Abilene, Temple-Belton, Waco, and Round Rock in the upper-middle Brazos basin all had populations of more than 100,000 as of the 2020 census. Those cities and others not only draw water out of the Brazos basin but return it in the form of effluent—also called wastewater.

“Everything can be tied back to the fact that our population is exploding,” Malzahn said.

As demand for water is forecast to outpace supply by 2040 and beyond, many options are being considered to augment it, from building more reservoirs to aquifer storage, desalination plants, and more creative ways to reuse wastewater and conserve potable water.

Population growth also means that as more water is being requested from the river, more effluent is being put back into it. As Malzahn put it, wastewater is a “doubleedged sword”—it’s necessary for water flow in the river, but accidental wastewater spills and discharges beyond what is permitted are common in the Brazos River basin. A few have been massive.

In 2021 a City of Waco wastewater treatment plant dumped 4.5 million gallons of untreated household sewage into the Brazos. The city blamed the spill on heavy rains and a mechanical failure at the plant. The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s (TPWD) Kills and Spills Team, which investigates fish and wildlife kills after spills or natural events, explained that sewage spills can cause fish kills when bacteria consume the organic matter in the sewage and use up all the dissolved oxygen in the water, causing fish and other aquatic organisms to suffocate.

Farther downstream, Texas A&M University discharged illegal levels of E. coli into the Brazos River from a wastewater treatment plant on its main College Station campus a dozen times over

a 21-month period ending in September 2017. Some of the releases were five times the maximum allowable amount under the law. The university blamed the discharge on an “operational issue” at its wastewater treatment plant and flooding from Hurricane Harvey. It was fined once for $12,600.

TPWD’s Inland Fisheries Division staff found no reports in their files of fish kills in Waco or in College Station after the sewage spills. That doesn’t mean a fish kill didn’t occur, an agency spokesperson said, but “if fish kills did take place, they were not reported to TPWD.”

When a treatment plant failure is due to heavy rains and flooding, the agency said, “the volume of water may be high enough, and the flow fast enough, that the sewage spill doesn’t impact fish.”

In addition to equipment failures due to weather, unintentional discharges while upgrading equipment also happen. Among Texas municipal wastewater dischargers, the City of Lubbock had the most exceedances of any city from December 2019 to July 2022, EPA data show. The violations included excessive amounts of E. coli, nitrogen and ammonia, phosphorus, and high biochemical oxygen demand, which is measured over five days and indicates polluted water.

Aubrey Spear, Lubbock’s director of water utilities, said the city began installing more efficient equipment in 2020. “Anytime you have to upgrade any of your wastewater treatment facilities, it’s like working on your Ford pickup while it’s running down the road,” Spear said.

“So during that process we have had some exceedances that were discharged.”

Although it was one event, it was counted as multiple violations in the data, he said. The city also had some equipment fail in early 2021 because of icy weather from Winter Storm Uri.

“We’re working with TCEQ on all of this,” Spear said. “Our goal is to have zero [problematic discharges].”

Comprehensive federal standards for water didn’t exist until the Clean Water Act passed in 1972. Under it, the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System, or NPDES, permit program authorizes state governments—TCEQ, in Texas’ case—to handle

permits and enforcement.

Environmental groups, though, have taken TCEQ to task for being too lax in regulating air, water, and land pollution. Since the groups filed their petitions in 2021, the EPA has repeatedly asked for more information and documentation of TCEQ deficiencies, as recently as November 2022.

Also in November, the Texas Sunset Advisory Commission, which periodically evaluates state agencies for their effectiveness and recommends changes to lawmakers, agreed. It found TCEQ needed to be more transparent and do a better job of enforcing compliance by increasing penalties on polluters. Lawmakers will take up the recommendations at the next legislative session that begins in January.

Section 303(d) of the Clean Water Act authorizes the EPA to assist states, territories, and authorized tribes in listing impaired waters and developing what is called Total Maximum Daily Loads, or TMDL. They establish the maximum amount of a pollutant allowed in a water body and serve as the starting point for plans to restore water quality.

The lists of waters impaired by a pollutant and in need of a TMDL and the lists of water quality status of all waters in the state are combined into a single “Integrated Report,” an important document that gives a snapshot of the health of Texas rivers, creeks, lakes, and other bodies of water. Once a body of water is listed as impaired, it remains there until the state develops a TMDL and the EPA approves it.

“When a segment of a stream, lake, river, whatever becomes so impaired from a particular pollutant, there’s supposed to be a rehabilitation plan,” Ortiz explained. “That’s something the Clean Water Act requires, that you actually have a plan to get impaired waters off the impaired waters list. And for the most part, TCEQ kicks the can down the road. It’s a very backlogged system.” In other words, TCEQ hasn’t developed those plans, or even developed TMDLs, for lots of these streams.

The fact that so many streams in the Brazos basin don’t even have TMDL scores worries environmentalists because that means “there are no pollution caps on Texas’ already most vulnerable waters,” Ortiz said. “That’s kind of frightening to think about.”

20 | TEXAS OBSERVER TEXASOBSERVER.ORG | 21

The list of so-called “impaired” waters in the Brazos River basin includes segments of major tributaries—the Leon, Lampasas, Little, and North Bosque rivers and Double Mountain, Clear, and Salt forks of the Brazos. Numerous creeks made the list, as did lakes Somerville (impaired for pH levels since 2002); Pat Cleburne and Graham (both for excessive algae growth); and Lake Alan Henry, which has been impaired since 2010 for mercury in edible tissue. The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department has placed a fish consumption advisory on that lake, recommending limits on eating catfish, crappie, and bass, and advising that children and pregnant women should not eat those fish at all.

TCEQ, through a spokesperson, responded that streams may remain on the list for various reasons—other strategies, such as water quality standards evaluations, can also take a long time to develop.

“It also takes a long time to develop TMDLs or watershed protection plans, which can contribute to the length of time a waterbody is on the list,” the agency added. “Waters with watershed protection plans, rather than TMDLs, remain on the list until water quality standards are attained. In some instances, it may take many years after implementing a strategy or several different strategies before water quality improvements are documented and a water body is delisted.”

Even the Brazos segment above Possum Kingdom Lake has been on the impaired waters list since 2008 because of too much bacteria in the water.

That segment is, in TCEQ parlance, a “Category 5c” for impairment, meaning that, for 14 years, the agency has been collecting data and information and evaluating it for a plan to manage the stream.

“They’re not close to selecting a management strategy, and that’s sort of one of the clear failures,” Ortiz said. “There’s a lack of thinking on TCEQ’s part in terms of the real interconnectedness of Texas waters. And there’s no environmental nonprofit that has the staff or funding to really take a holistic look at statewide water quality.”

Conservationists and environmental activists have scored some impressive wins when it comes

to protecting the upper to middle Brazos.

Dallas restaurateur and river paddler

Ed Lowe founded Friends of the Brazos after he grew alarmed by the BRA’s action in 2004. The river authority had asked the state to more than double the BRA’s water rights, adding about a million acre-feet of water to the 700,000 acre-feet it already held in reservoirs. (An acre-foot is about 326,000 gallons, or enough water to cover an acre of ground with one foot of water).

Lowe, Graves, and other conservationists hired scientists and lawyers to challenge the plan. They claimed it would give the BRA power to take possibly every drop from the river for future sale to cities, industries, and others without having to reveal at what points it would be taken or the potential impacts on water quality or fish and wildlife.

TCEQ rebuffed the BRA’s request.

Lowe was not as successful in convincing legislators to extend the John Graves Scenic Riverway protections to the Brazos in Hood and Somervell counties.

The Texas House’s Natural Resources Committee, many of whose members accept campaign contributions from the

and, recently, into a controversy that makes it a microcosm of what is happening in the Brazos basin.

Friends of the Brazos supported a group of concerned citizens who formed Granbury Fresh to fight that city’s plan to build a new second wastewater treatment plant and discharge 2 million gallons of effluent daily into the Rucker, a scenic creek lined with boat ramps and where residents routinely kayak, canoe, swim, and fish. The new plant would add capacity that the fast-growing city, now a retirement and recreation refuge for people from all over urban North Texas, badly needs.

City officials said that if it does not build the new plant, they have no choice but to prohibit new development. The city in 2020 issued a moratorium on approving new plats and construction permits. It estimated that the city would lose hundreds of jobs over the next decade if the plant isn’t built. “This creates spinoff consequences of loss of state and local tax revenues, which will negatively impact local government services,” city officials said in documents filed with TCEQ.

as “absolutely symbolic” of the clashes taking place around Texas between growth and conservation.

“Clearly, the Brazos is a resilient river. It’s a large river, so it can absorb a little more,” Dornak said. “The canaries in the coal mines will be a lot of these streams like Rucker. ... Do you flip that pretty, pristine stream to ‘impaired’ and change the aquatic ecosystems and do long-term impacts to the health of those streams?”

In May 2021, the Texas House passed a bill banning the dumping of wastewater into stream segments deemed “pristine” because of their low phosphorus levels. The so-called “Pristine Streams Bill” received bipartisan support and passed by a vote of 82 to 61, but a companion bill died in the Senate.

Most of the 22 streams identified as “pristine” are in the Hill Country. (Rucker didn’t qualify as an official pristine stream.) The only bodies of water in the huge Brazos River basin considered to be pristine were the north and south forks of the San Gabriel River in Burnet and Williamson counties.

Canoe Rental by the bridge, couldn’t contain his excitement that the BRA had released water from the dam that morning—the authority said it was doing so to balance the drawdown levels between lakes Possum Kingdom and Granbury. Rochelle said he thought it was done because of Granbury’s swanky new lake developments and wealthy, politically influential people.

Regardless, the release would give his customers who rent canoes and kayaks plenty of water and even some rapids to enjoy.

“I’ve heard all kinds of little horror stories downstream from us about the Brazos being completely dry in some places,” he added. “We’re just in a bad state right now.”

Rochelle’s family has lived here since 1928 and has owned and operated the business near Graford since 1969. Many of their customers have read Graves’ book or even bring it with them, Rochelle said. “I’m talking about a lot of people,” he added, pointing at a copy of Goodbye to a River on his office shelf.

aggregate industry, killed the bill to extend protections in 2013 before it ever made it out of the committee.

Graves died in 2013 at his home in Glen Rose, and Lowe died in November 2018 during a paddling trip to Big Bend. But Friends of the Brazos is carrying on without the two men who did so much to make so many people care about the river. Both men’s families are still involved.

Dornak is Lowe’s son-in-law, and Sally Graves Jackson, one of Graves’ daughters, contributes to Friends of the Brazos. Its current mission is one of stewardship— keeping water in the Brazos, keeping trash and pollution out, and holding an annual river cleanup.

“What kind of permanent damage are we doing in the long term and how climate change will impact all this is really important,” Dornak said. “So that’s what gets me going every day. This conservation effort must go on.”

East of Granbury, Rucker Creek runs through wooded areas and past affluent housing developments like those springing up all over Hood County. It eventually flows into the Brazos and Lake Granbury

Victoria Calder, a Friends of the Brazos board member and president of Granbury Fresh, said that if a storm and power outage caused a spill in Rucker Creek such as happened in Waco, it would be devastating to residents and the environment.

“It’s a matter of when, not if, a spill happens,” she said. “The severity of consequences in a high recreational, narrow, shallow creek is over the top. It really ruins the public welfare, which is supposed to be protected under the Clean Water Act.”

The contested case went to the State Office of Administrative Hearings.

Last June, administrative law judges recommended that the TCEQ issue a draft permit. In October, TCEQ commissioners voted unanimously to grant the permit.

Granbury city officials declined to comment on the new wastewater treatment plant because of “possible future litigation.” In a news release, they said that once the new plant is built and begins operating, the wastewater system issues “will be resolved,” implying that’s when it would lift the moratorium.

Dornak described the Rucker Creek case

Even though it didn’t become law, the bill made it further than any previous proposed legislation on wastewater discharge. Conservationists filed a petition with the TCEQ to create a rule against issuing wastewater discharge permits on pristine streams. The commission received more than 1,200 comments and in March heard over an hour of in-person comments but denied the petition. However, it left the door open for continued stakeholder talks on how to better protect Texas’ last few pristine streams.

“We need leaders at the state and national level that can inspire and move the needle on how we’re managing our land and our water resources,” Dornak said. “That Pristine Streams legislation getting through the House shows we can achieve some really good bipartisan solutions on water if it’s done right.”

The “John Graves Scenic Riverway” sign appears just before Farm Road 4 crosses the Dark Valley Bridge in Palo Pinto County. On a sunny day last October, the Brazos flowed steadily, rippling over rocks under the bridge.

Buddy Rochelle, co-owner of Rochelle’s

Sally Graves Jackson said her father’s book “encouraged people to pay attention and perhaps feel responsibility for a landscape that has a history and a value that’s not just recreational, or agricultural, or industrial. The Brazos has a past that mattered.”

Its future matters, too.

Before he died, Lowe left what now sounds like an ominous warning on Friends of the Brazos’ website. Lowe said he was worried that the river, especially the part from Possum Kingdom to Glen Rose, has suffered “significant ecological damage—stream fragmentation, channel sedimentation, frequent golden algae blooms which devastate fish populations and significantly reduced instream flows.”

He added that before you can save a river, you first have to fall in love with it. “That’s what John Graves did more than 50 years ago,” he wrote. “Now it’s our turn to save this wonderful place before it’s too late.”

Kathryn Jones, a veteran journalist, author, and longtime Texan, has also written for The Dallas Morning News, Time magazine, The New York Times, and the Texas Monthly She has been inducted into the Texas Institute of Letters.

22 | TEXAS OBSERVER TEXASOBSERVER.ORG 23

Aubrey Spear, director of water utilities for Lubbock, said polluted discharges there happened while the city was installing new equipment.

24 | TEXAS OBSERVER TEXASOBSERVER.ORG | 25

Residential, commercial, and industrial wastewater is processed through the sludge process basin at Lubbock’s water treatment plant.

By TEXAS OBSERVER STAFF

Illustrations By DRUE WAGNER

LEGE THE 20 23: ASTR CAT OPHE#88

E

Elections have consequences. This political bromide is overused for a reason—it’s reliably true. And this year, the fallout for vulnerable Texans could be particularly destructive.

After something approaching a blue wave swept across Texas in November 2018, a chastened Republican majority in the Legislature kept its focus in the 2019 session on serious policymaking— school finance and property tax reform—while largely forgoing their typical red-meat fare.

Republicans thwarted expectations of another Democratic surge in November 2020, and the next year the GOP ignored the problems laid bare by the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing economic crisis, instead focusing on passing as much right-wing legislation as possible over the course of a regular session, plus three painful specials.

The final outcome was ugly: Abortions were effectively banned by threat of bounty, handgun permits were done away with, voting laws were made more restrictive, transgender kids were targeted with statutory bigotry, and school curricula on race and history was whitewashed. Profound policy problems, meanwhile, were left to fester.

Critically, the state’s electoral districts were redrawn for the next decade to ensure incumbent Republican majorities will be insulated from electoral backlash while the state’s growing numbers of people of color and Democratic-aligned voters are kept at bay.

This fresh gerrymander set the table for another Republican rout last November as the GOP maintained strong majorities in the state House and Senate and easily

swept the state’s high-powered executive offices—led by Governor Greg Abbott’s 11-point defeat of Democratic challenger Beto O’Rourke.

Firmly in control, Abbott, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, and GOP lawmakers are now free to do as they please—to pick up where their vengeful 87th legislative session mercifully left off just over a year ago.

Some top Republicans hinted during campaign season that they might want to soften the sharpest edges of their draconian and unpopular ban on abortion or pull back on the most extreme parts of their so-called “election integrity” laws. But there’s little reason to think this legislative session will yield moderation. The party’s activist base is eager to continue the march toward one-party authoritarianism, punishing political enemies and catering to political patrons as they go.

Many bills have already been filed to further expand prosecution under Texas’ abortion ban, along with measures to concentrate power over elections in the office of GOP Attorney General Ken Paxton and to continue persecution of transgender children and their families.

Lawmakers will also be charged with allocating a projected massive surplus of state revenue—over $25 billion—from inflation-fueled sales tax receipts and huge oil and gas production taxes. Republicans are salivating as they plan to shovel money into tax relief for homeowners, likely without alleviating the fundamental problem of soaring property taxes. Many other political pet projects, like Abbott’s bloated Operation Lone Star border scheme, are likely to get a taste too. But that shiny surplus figure contains plenty of smoke and mirrors, budgetary gimmicks, and external uncertainties that can only be resolved by transparent fiscal governance—not hide-the-ball, kick-the-can budgeting. Meanwhile, there is plenty of serious work to be done. There are billions in once-in-a-generation federal funds for infrastructure and energy projects that could set Texas up for the future. The electric grid still needs fixing. The public school system still needs help recovering from the pandemic. Government

agencies and public services are crying for significant reform and investment.

Ahead of every new legislative session in Texas, there’s always a glimmer of hope that lawmakers will rise to the occasion, that reason will at least get a public hearing. This is usually coupled with the well-earned suspicion that, instead, the next race to the bottom will take us to parts previously unknown and unimaginable. Here, we do our best to survey what we believe will be some of the most highprofile policy topics facing Texas—what could and should be done, and, more likely, what will happen instead. —

Justin Miller

Justin Miller

MAKE GOVERNMENT GOOD AGAIN

For years, lawmakers have failed to heed warnings from leaders of Texas’ biggest and most important state agencies about a growing inability to provide critical services to a booming population, often due to depleted workforces and antiquated technology.

Instead, legislators have repeatedly cried poverty, demanding departments do more with less. Now GOP policymakers are confronted with the consequences of their indifference and hostility toward the state’s moribund bureaucracy.