WRECKING WOMEN’S HEALTHCARE

By JULIE POOLE

By JULIE POOLE

INVESTIGATING TEXAS SINCE 1954

Women’s Health on the Line

Low-income

By JULIE POOLE

By JULIE POOLE

Low-income

MAY/JUNE 2023

EDITOR- IN - CHIEF Gabriel Arana

CREATIVE DIRECTOR Ivan Armando Flores

SENIOR WRITER & EDITOR Lise Olsen

EDITOR-AT- LARGE Gayle Reaves

DIGITAL EDITOR Kit O’Connell

SENIOR WRITER & ASSISTANT EDITOR Gus Bova

SENIOR WRITER Justin Miller

STAFF WRITERS Delger Erdenesanaa, Josephine Lee, Michelle Pitcher

EDITORIAL FELLOW Sara Hutchinson

SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER Tyler Lewis

POETRY EDITOR EMERITUS Naomi Shihab Nye

STAFF CARTOONIST Ben Sargent

COPY EDITOR Adam Muro

FACT CHECKER Christopher Collins, Zein Jardaneh

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

John Burnett, Sergio Chapa, Kim Nall, Roberto Ontiveros, Julie Poole, James Russell, & Naomi Shihab Nye

CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS

Kathleen Fu, Clay Rodery & Drue Wagner

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Meridith Kohut, Gerald Kern, DEVELOPMENT MANAGER Lauren Benavides

MICHELLE PITCHERBUSINESS MANAGER Nikki Kobiljak

TEXAS DEMOCRACY FOUNDATION BOARD

Lize Burr (interim board president), Terri Burke, Carlton Carl, Mark Horvit, Carrie James, Kathleen McElroy, Peter Ravella, Lizette Resendez, & Skye Perryman; Ronnie Dugger (emeritus), Abby Rapoport (emeritus), & Ron Rapoport (emeritus)

EDITORS EMERETI: Jake Bernstein, Nate Blakeslee, Lou Dubose, David Mann, Bob Moser, Kay Northcott, Geoff Rips, Andrea Valdez, & Forrest Wilder.

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: M ichael Agresta, Asher Elbein, Alex Hannaford, Christopher Hooks, Steven G. Kellman, Robert Leleux, James McWilliams, Bill Minutaglio, Rachel Pearson, Robyn Ross, Brad Tyer, & Daniel Blue Tyx.

FOUNDING EDITOR Ronnie Dugger

OUR MISSION

We will serve no group or party but will hew hard to the truth as we find it and the right as we see it. We are dedicated to the whole truth, to human values above all interests, to the rights of humankind as the foundation of democracy. We will take orders from none but our own conscience, and never will we overlook or misrepresent the truth to serve the interests of the powerful or cater to the ignoble in the human spirit.

On the last Sunday of March, I was playing hideand-seek with our golden retriever when I got a call from the editor-in-chief of the Texas Tribune: “Gabe, we have a 2,300-word story coming out.” Our board, he told me, had voted to lay off the Texas Observer staff and cease publication. The blood drained from my brain. We have a staff member with a baby on the way, one who just quit another career to start here, and several with cats that need to eat. All were going to be jobless with just days’ notice. With dread, I started calling our team. Then, something shifted: We began to talk about whether we could stop it.

GABRIEL ARANA Editor-in-Chief

GABRIEL ARANA Editor-in-Chief

The staff decided to make a simple but profound request to the board the next day: Let us try to raise the money we need. Let us try to save the place. If we can raise $200,000, one editor suggested, will you consider rescinding the layoffs? A board member asked, “Where are you going to get 200K?”

What some seemed to have forgotten was that the Observer is more than a magazine—it’s a movement with followers who read us for many different reasons. As I tweeted, “This is not a Walmart you can just shut down. … It’s an idea in the minds of our readers. Of the people who work here now. Of everyone who has worked here before. It belongs to the public. “

We sought advice, designed ads, talked to the press. Most important, our former managing director launched a GoFundMe that attracted an awe-inspiring $350,000.And then a miracle happened: The board voted to rescind the layoffs. We now have a fired-up board with new and old members, and we’re working together to make sure this thing is around not just for six months but for 69 more years. The immediate crisis is over, but times are still dark, and we need you. Subscribe to the magazine. Sign up for our free newsletter. Get one of our t-shirts. Write and tell me what you want to read about. Support us.

Let’s keep fighting.

by

by

It’s become an inside joke among Capitol watchers that the best way to figure out what Governor Greg Abbott and the Republican Legislature are gonna do next is to read the Miami Herald—or better yet, follow Florida Governor Ron DeSantis on Twitter.

While that’s a bit overstated, it’s truer than Abbott and his allies would care to admit. Long the biggest, baddest political perch in red state America, the Texas governorship is no longer the singular juggernaut it once was in national politics. DeSantis, boy wonder of the Sunshine State, availed himself of a GOP power vacuum that opened after Trump’s 2020 presidential loss, becoming the frontrunner among 2024 Republican presidential contenders whose names don’t end in rump. That status was further solidified by his nearly 20-point blowout reelection in 2022,

making Abbott’s own 11-point drubbing of Beto O’Rourke look downright quaint.

With a new GOP supermajority in both chambers of the Florida statehouse, DeSantis has advanced an agenda that is obsessively focused on so-called anti-wokeism, punishing public schools and teachers, LBTQ+ folks, the Disney corporation, and the free press via state-sanctioned culture policing.

For the past few years, Abbott has engaged DeSantis in a not-so-subtle shadow boxing match over who could use their emergency powers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the most perverse fashion or who could sign the most oppressive legislation into law. But the political feedback loop between Tallahassee and Austin, telegraphed by way of Fox News and Newsmax, has become all the more transparent during this state

of the Florida man’s hateful innovations into the Texas Senate. The little gov is, for instance, leading the charge on a bill that would prohibit any discussion of sexuality or gender in Texas’ K-12 classrooms—a more far-reaching version of DeSantis’ “Don’t Say Gay” law that is limited to elementary schoolchildren. The Texas Senate has also passed a sweeping bill to ban all gender-affirming healthcare for transgender kids in Texas, which would go beyond Florida’s similar edict by outlawing care even for current patients.

While DeSantis’ allies have been speedrunning his political vendettas through the Florida legislature, the Yale and Harvard alum embarked on a national tour ostensibly to promote his literary opus entitled The Courage to Be Free: Florida’s Blueprint for America’s Revival Obviously, the book tour doubles as a dry run for his all-but-announced presidential bid. The tour brought him onto Texas turf this spring as an esteemed guest at two local GOP dinner events in Houston and Dallas, where he declared Florida to be an equal partner with the Lone Star State in the coming wars on wokeness.

“They know you don’t mess with Texas—and you don’t tread on Florida,” DeSantis declared at one event. “I really believe if it hadn’t been for Texas and Florida playing the role we have in this country in recent history, our entire country would be one big woke, neo-Marxist dumpster fire.” DeSantis never mentioned Abbott by name, referring to him only as “your governor.”

In April, DeSantis headed to Austin as

the marquee guest for an event hosted by the Cicero Institute, the personal think tank and lobbying operation of venture capitalist and Palantir co-founder Joe Lonsdale. Since fleeing Silicon Valley for Texas as a self-declared political refugee, Lonsdale has quietly become a player in GOP politics here, developing close connections with Abbott-world.

Daniel Hodge, Abbott’s former longtime aide, is an advisor to Lonsdale’s venture capital firm 8VC and arranged a lunch between the investor and the governor in 2020. Abbott’s daughter also works for 8VC as an events coordinator.

Lonsdale is also a DeSantis donor and said he could support him for president, though he hasn’t officially endorsed.

Meanwhile, when the topic of DeSantis-Abbott tensions is raised, Abbott is quick to note that Texas has outpaced Florida with passage of a total abortion ban and permitless carry law, while insisting that he and Ron are buds. “DeSantis and I do a lot of things together,” he said in 2021. “We talk in ways and times that people have no idea about … and so I just kind of roll my eyes and scoff a little bit when people say these things.”

In Tallahassee, DeSantis allies seem to think the whole Abbott-DeSantis comparison is a cute parlor game for Austin insiders. “Not to be disrespectful to Gov. Abbott, but I don’t think there are many people in the DeSantis orbit who consider that to be a rivalry,” Brian Ballard, a top Florida lobbyist and powerbroker, said earlier this year. “I never

have anyone say to me, ‘Did [DeSantis] get that from Gov. Abbott? Did you see what Gov. Abbott did in Texas?’”

While DeSantis has certainly gotten the better of Abbott in raising his national profile and becoming the postTrump voice of grievance ideology, the actual tit-for-tat in their political arms race may not be all that relevant in a presidential primary several months out. DeSantis’ stature has already made him a target for Trump—who has launched his comeback campaign and dubbed the former “Ron DeSanctimonious.” And in presidential politics, the first thoroughbred out of the gate is often the first to stumble and fall. Just ask the last Florida governor (“please clap”) or the last Texas governor (“oops”) to enter a presidential race with a supposed frontrunner pedigree. Abbott and his political aides have done the typical dance around presidential speculation, saying he’s solely focused on the tasks at hand in the legislative session. By the time summer comes, DeSantis may well have melted down—and an indicted Trump may have absconded to Riyadh. Abbott and his political handlers are keeping their powder dry regarding his own rumored presidential ambitions, while leaving open the chance that maybe he’ll start sniffin’ around after sine die. The question then: Will Abbott, who’s become something of a petty tyrant here in Texas, where he’s spoiled by the safety of one-party rule, prove to be anything other than yet another governor out of his league?

legislative season.

One of Abbott’s first moves this year, uncharacteristically for a governor who usually stays behind the scenes in a session’s early days, was to throw his support behind a Senate bill that would ban certain foreign entities and citizens of countries like China and Iran from buying land on Texas soil. The pronouncement came five days after DeSantis held a press conference pledging to do the same in Florida. In February, a week after DeSantis pledged to ban “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” (DEI) in state colleges, Abbott’s chief of staff Gardner Pate sent a memo to Texas agencies and universities warning that it was illegal to consider DEI principles in hiring decisions.

Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, a politician in the same anti-woke warrior mold as DeSantis, has eagerly imported many

A veteran NPR reporter tells all about his misadventures in covering religion in America.

By JOHN BURNETTMy late father-in-law, an Episcopal priest, had a cartoon taped to his kitchen wall in Sherman that skewers an obnoxious feature of American religion. In the cartoon, a grinning devil, sitting on a throne surrounded by flames, instructs a horned apprentice, suitcase in hand, who is about to head upstairs to torture the human race.

“Remember to quote lots of Scripture,” Satan says.

If you work as a reporter for more than four decades in Texas, as I have, you will—regularly—encounter the most inappropriate, unfortunate and downright bizarre invocations of the Almighty. It’s enough to make me, a church-going Episcopalian who has—until now— kept my beliefs in the closet as a reporter, ruefully agree with the quip I saw on a refrigerator magnet. A man says to the Prince of Peace: “Please Jesus, protect me from your followers.”

Case in point: my interview years ago with an ambitious Texas Baptist pastor who had his eyes on the prized presidency of the Southern Baptist Convention. He was—surprise, surprise!—virulently antigay. So I asked him, if Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount was all about agape, compassion, and selflessness, why did the preacher so forcefully condemn homosexuality?

“God did not intend for the human anus to be a sex object!” he blurted.

I thought to myself, “That’s the money

quote.” Too bad NPR will never let that on the air. But the parson, apparently, worried more how his proctological outburst would be received by his Baptist brethren. As soon as the interview ended and I’d put my microphone away, he asked brightly, “John, would you mind striking the anus quote?”

But wait, there’s more! Did you know that Jesus, who said the truth shall make you free, is also into banning books? Just ask right-wing Christians in Llano County who objected to a list of books in the public libraries in 2021.

The controversy began with a series for children: My Butt Is So Noisy!, I Broke My Butt!, and I Need a New Butt! (titles that I found satisfying to recite on the earnest airwaves of public radio.) Critics called the crude illustrations of bare bottoms “child porn.”

“I wrote the Butt Books for fun,” the bewildered author, Dawn McMillan, emailed me from her home in New Zealand. “They are silly stories bringing laughs while getting kids, especially boys, into reading.”

As I was covering that story, the role of the Divine in banning books eluded me, but not so for Bonnie Wallace, a conservative activist later appointed to the local library advisory board. In an email to county commissioners, she urged local pastors to “organize a weekly prayer vigil on this specific issue,” and concluded,

kids deserve the best.” I interviewed Rev. Richard Dortch, PTL executive vice president, at the Heritage Island water park. Should the millions spent on Heritage USA have been better directed to relieving suffering and poverty? I asked. He flashed a million-dollar smile and, without a note of irony, replied, “If Jesus were walking the earth today, John, I believe he would want a water park to minister to his followers.”

Bakker and Dortch ended up in federal prison for duping believers into investing in the development. Thanks to Bakker, PTL, which he intended to be Praise the Lord, has become known as Pass the Loot.

When someone comes and says, ‘I have all the answers,’ that’s seductive, especially for people who feel vulnerable.”

Of all the misguided religious movements I’ve chronicled, none comes close to the evangelical hordes that currently espouse Trumpism within the ideology of Christian Nationalism.

Early last year I traveled to Lenoir City, Tennessee—in the shadow of the Smoky Mountains—to attend a Sunday service at the Patriot Church, a barn-like building with a huge American flag painted on the outside. The name conflates Christian

Peters said as much in his sermon, “How Satan Destroys the World.”

I was sitting self-consciously on the front row, recording the service and taking notes.

“May God protect our children from this FILTH.”

The Llano County Commissioners Court ended up removing or restricting the Butt books and others about the KKK, racial castes in America, and teen sexuality. And in 2023, Texas—represented by selfanointed Christian book reviewers–still leads the nation in the spreading bonfire of book censorship.

The genius of aberrant Christianity, throughout history, seems to be how effortlessly it accommodates whatever the prophet du jour wants to get away with.

Part of the reason this bothers me is that, as a Christian, I find it repugnant to see the loving, peaceable teachings of Jesus distorted over and over. Worse, reporters often let conservative Christians get away with speaking for all believers.

Consider Heritage USA, one of my first stories for NPR, when I was a freelancer living in Atlanta. Back in the mid-1980s, televangelist couple Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker built this Christian wonderland in Fort Mill, South Carolina, to glorify God and line their pockets. It became America’s third-most popular theme park.

I had just been baptized and I was trying to figure out what it meant to live your faith, when I beheld Heritage USA. There was the “Christian shopping mall” and the Southern-baroque Heritage Grand Hotel where a guest told me, “The King’s

Remember David Koresh, the madman who led his Branch Davidians to mass immolation at their religious compound outside Waco in 1993? That was my first mega-story for NPR, and I practically lived at a cheap hotel in Bellmead throughout the 51-day standoff.

A lot has been written about the two disastrous raids launched by federal agents, but let’s not let Koresh off the hook. He was a beer-drinking, guitarplaying, skirt-chasing, gun-collecting rogue whose ability to quote long passages of Scripture apparently convinced his cult that he was a messianic figure right out of the Book of Revelation.

Koresh, né Vernon Howell, stockpiled assault rifles, raped underage girls, cuckolded male followers by sleeping with their wives, and told the Waco TribuneHerald, “Y’know, bein’ Christ ain’t nothin’.” Since I retired from NPR in January after 36 years, I’ve been trying to process all the church scandals and schisms and falls from grace that I’ve covered. They all shared the same throughline: People of faith trusted a man with Rev. before his name who seemed to have a hotline to God. I’ve asked myself how these charismatic figures, reeking with the musk of prophecy, led their gullible flocks into dark places over and over?

I posed that question to my friend, the Rev. Cynthia Briggs Kittredge, dean of the Episcopal Seminary of the Southwest in Austin.

“People are attracted to certainty, to non-ambiguity,” she said. “Making decisions for yourself and doing the work of discernment, that’s really hard work.

“The first lie was when the serpent told Eve to eat the apple!” thundered Peters, prowling the stage with a wireless mic. “And the second lie? The mainstream media. And NPR is sitting right over there.” The congregation eyed me suspiciously. I waved and smiled. When I finished my interviews and headed for the parking lot, several folks said they would pray for me. I’ve heard that line while reporting on religion for years. I’m gonna pray fer yew, John. To which I respond, “Great! I need the prayers and you need the practice.”

My wise father-in-law, the Episcopal priest, used to wince whenever I covered a Jim Bakker or a Jimmy Swaggart, because those scandals hurt all of Christendom and reinforced the age-old cynicism that organized religion is a con and all preachers are corrupt. I wish I had done more in my reporting life to quote the many inspiring, tolerant religious leaders. And I wish I had objected when conservative Christians piously purported to speak for all believers.

fervor with a truculent brand of American patriotism.

I asked a congregant, “Is this a Donald Trump church?”

“Yes,” replied Murray Clemetson, a law school student and father of three.“You go to flyover country and people have good moral values. They love the Lord and they want the best for our country. And that’s what Donald Trump represented,” he added, referring to the most explicitly selfinterested president in American history.

The Patriot Church believes that vaccinations violate religious freedom, the Jan. 6 rioters were freedom fighters, the Biden administration is illegitimate, and the media is the voice of evil. The Rev. Ken

Here’s where I get in trouble. I am a Christian so this might seem mildly heretical, but I disagree with people who say Christianity is the only way. Having reported on calamities in 30 countries, I’ve seen God at work in the world in myriad ways. At the end of the day, I agree with the sentiments of a popular muezzin (Muslim cantor) I interviewed at a Los Angeles mosque. Abdelwahab Benyoucef is an Algiers-born Hollywood actor—with classic good looks—who gets cast over and over as a Middle Eastern terrorist. Here’s what he had to say about the world’s major monotheistic religions.

“Think of Wilshire Boulevard as Christianity. Santa Monica Boulevard is Islam. Montana Boulevard is Judaism. Take any of those boulevards and they all reach the Pacific Ocean, which is God.”

CURRENTLY ESPOUSE

these people back in their place.”

Would you call the governor a white supremacist?

I think, obviously, that’s something to be more careful about. A lot of these things have white supremacist roots— whether or not that’s the reason they’re carrying it, whether or not that’s where it came from—I don’t know.

Now in his sixth regular legislative session as a member of a largely powerless minority caucus, state Representative Gene Wu, a 45-year-old Houstonian, has cultivated a number of strategies for a Texas Democrat to stay busy. He battles trolls on Twitter; he searches for marginal ways to make state systems work better for vulnerable kids; and lately he’s taken off as a political communicator on Reddit.

An immigrant originally from China, he’s spent years battling xenophobia in Texas’ Capitol. In 2017, he gave a memorable and tearful floor speech decrying that year’s anti-“sanctuary cities” bill, and this year he fought against a bill that would have banned land sales to citizens from certain countries, including China. He represents a district where 71 percent speak a language other than English at home. He’s long been pugnacious on Twitter, and when Democrats in 2021 broke quorum to oppose anti-voting legislation, he was among the most strident and stubborn holdouts. In a recent development, he’s posted videos on Reddit explaining topics from lobbying to marijuana policy, sometimes while sipping a whiskey rocks. The Texas Observer spoke with him about bomb-throwing, Democratic discourse, and white supremacy.

TO: You’ve spent a decade now in the minority party in the Texas House of Representatives. Why?

Because somebody has to do it. Ultimately, my heart is in public policy, and there’s a lot of stuff that needs to be done outside of red-meat issues for either side. We’re in the Juvenile Justice and Family Issues Committee right now reforming Child Protective Services, the juvenile justice system. Those kinds of things need people to work on them regardless of whether you’re in power.

Some of your fellow House Democrats seem to have taken a more conciliatory approach toward Republican leadership and, in turn, gotten committee chairmanships. Do you think it’s more impactful to stick to principles than to try to play the game in that way?

I don’t think there’s a right answer either way. It’s publicly known that I’m not someone who bows to the Republican leadership, but at the same time, I’m not

openly antagonistic toward them except on certain policy issues. Everyone should just play to whatever their personality is. And obviously, there are some people who are just natural bomb-throwers. Go throw bombs, then. And some people are naturally more collaborative and cooperative.

I remember I was at home, on my laptop, when you gave that House floor speech against the anti-”sanctuary cities” bill way back in 2017.

Ah, yes.

A lot of people saw that, of course.

It went viral, 80 million views.

Yes.

I get random people, I remember very clearly, I was outside of Houston, and some teenage girl came up to me and said, “Hey, I want to tell you something from my father,” and then he comes over and the young girl says, “My dad

doesn’t speak English very well, but he told me to tell you that he saw you on the video, and it was really important for him.”

I think it was so affecting because you were explaining that everything lawmakers were saying that night struck you a certain way because you’re an immigrant yourself, right there in the same chamber as all of them.

And I represent a district that’s 80 percent immigrants, including many who are undocumented. They still take care of everyone. They clean everyone’s office buildings; they clean up people’s houses; they mow their yards; they make your food; and you guys are happy when they’re taking care of you, but now you want to abuse them.

Fast-forwarding to now, there is the bill, which you’ve helped push to modify, about Chinese citizens, other citizens, not being able to buy property. There’s also a border militia

bill. What’s gone wrong with our state’s attitude toward immigrants?

I don’t think it’s a state issue. This is a national movement that’s antiimmigrant, that’s toward rolling back minority participation, minority rights—everything. The anti-DEI [diversity, equity, and inclusion] stuff, the anti-CRT [critical race theory] stuff, the antiimmigrant movement. It’s all tied together under

one auspice: A lot of these little things had a very strong white-supremacist basis. From the 20,000foot view, America goes through these waves of extremism, these waves of anti-immigrant feelings, anti-Asian feelings, antiLatino feelings, and we’re just now at the crest of this wave. The anti-immigrant wave is coinciding with the anti-Black wave, the anti-Hispanic wave, the anti-LGBTQ+ wave. There’s a sense of “We have to put

I have to touch on Reddit. That’s your new thing lately getting media attention is that you are the lawmaker on Reddit.

I’ve been on Reddit for many years and would never post—just lurk and see the funny memes and watch people fight over stupid things. But what made me finally register an account was I had to do an Ask Me Anything [AMA] for President Joe Biden. Those kinds of things kicked me off and made me start having a formal account, or at least a nonburner account. I have a burner account—don’t worry about that.

I am an investigative reporter.

You will not find my burner account, I promise you; I don’t post anything on it.

Strictly lurking?

Strictly lurking. But one of the reasons I like it, especially coming off Twitter, which is now more obnoxious than ever, is that I’m by nature kind of a troll—I mean

more than kind of—but I also enjoy having a real discussion with people if they’re willing to listen and not just call people names. Reddit is especially good for these kinds of discussions because the way posts are voted up and down creates a system where if you’re going to troll, you better be really funny, because if your trolling is pathetic you’ll just get voted down; your comment will disappear. And the thing that made me say, “Fine I’ll do this,” is that I watched so many different people on Reddit say, “I’m genuinely frustrated with government, with my representation, and I don’t know what to do.”

So I finally had to jump in saying, “You can still do stuff, this is how you do it.” That is hard to explain in a tweet—and after you do like ten tweets in a thread, people stop reading it. But on Reddit, you can write this giant post and people will read through it and they’ll criticize something that’s, like, at the very bottom.

It’s a better version of democratic engagement and discussion.

Yeah, and I felt bad for people on Reddit who genuinely seem like they care, but they felt frustrated. I wanted to be able to say there is at least one person here who is listening to you; somebody in the government cares that you have thoughts and feelings.

Flooding and bureaucracy drove Mary Kelleher to run for a spot on a powerful North Texas river agency board.

By JAMES RUSSELLMary Kelleher knew she was moving to a floodplain when she bought a farm on Fort Worth’s east side in 2003. But the risk was worth it. “I just fell in love with it because there was still so much country over here,” she said.

She did not expect that, nearly two decades later, the 100 acres she loved would nearly cost her her livelihood, propel her into public office, and drive her to become a flood control activist.

At first the high-water incidents were about what she’d expected for a floodplain: manageable if you prepared. Her house was on a high point on the property, safely away from flood-prone areas.

But the water rose faster than usual in 2010, killing some of her livestock and ruining thousands of dollars of equipment. “Our sheep were down by the barn, and they got confused. Instead of running to the house and up to high ground, they ran toward the water,” she recalled tearfully. “I still have nightmares about watching the sheep wandering off [into the water] and never coming back up.”

What’s more, the water didn’t return to normal levels for about eight months.

Tropical Storm Hermine played a major role in the flooding, local officials told her, adding it would never happen again. But massive flooding did happen again, just two years later. This time, there was no tropical storm to blame. Instead, many local people blamed the water release policies of the Tarrant Regional Water District (TRWD). On the strength of outrage over those

policies and others, Kelleher was elected to the district’s board the following year.

“When I needed help from my elected officials, they looked the other way. I ran for election so no one would have to experience that at the water district,” she said.

For many years, the TRWD was a littleknown, uncontroversial agency that provided water to numerous Tarrant County cities and was responsible for flood control for 11 counties in North Texas.

But critics charged that the agency had gone astray from its flood control mission, was riddled with nepotism, and was abusing its eminent domain powers to carry out its billion-dollar Trinity River Vision project, ostensibly designed to improve flood control but also to remake about 800 acres north of downtown into a San Antonio Riverwalk-type development.

Opponents question whether the project, which has gone by several names over the years, will improve flood control at all, although its continually increasing price tag and increasing focus on economic development has eaten up federal funds available for actual flooding problems in the area. They object to the water board’s practices in forcing some private owners to sell their land for the project, and then reselling the land to private developers. Since the project started, three new bridges have been built over dry land (where the river is supposed to be rerouted), plus one apartment complex, a brewery and a drive-in movie theatre in the area the water

district has dubbed “Panther Island.”

A broad coalition of opponents recruited Kelleher to run. They ranged from billionaire hotelier Monty Bennett, a major conservative Republican donor in Dallas who joined the fight when the agency tried to put a pipeline through his East Texas ranch, to former state Representative Lon Burnam, once named the most liberal member of the Texas House.

Burnam joked that he’s had issues with the water district since the 1970s when he drove from Austin, where he was studying at the University of Texas, to vote for a pro-environmental candidate running for the board. However, the Fort Worth native found out he didn’t qualify to cast a ballot: His parents’ home in Benbrook, a Fort Worth suburb, was not part of the patchwork map of areas included in the water district’s boundaries.

Two decades later, in 1996, Burnam won election to the Texas House from a Fort Worth district that included downtown and the future Panther Island. While in the House, he filed numerous bills to reform the TRWD.

The agency is also a textbook tale of cronyism: U.S. Representative Kay Granger, R-Fort Worth, chair of the House Appropriations Committee, is one of the project’s biggest advocates and also the mother of J.D. Granger, who served for years, until 2022, as executive director of the Trinity River Vision Authority (TRVA), an unelected board that acts as a buffer

between the public and the elected water board. Then-TRWD General Manager Jim Oliver also landed his nephew Matt Oliver a gig as TRVA’s communications director. Kelleher is warm, joyful, and tough. Working in juvenile services for Tarrant County for two decades, she saw many harrowing cases. But her first term on the water board often brought her to tears. She was officially censured by her board colleagues. Jim Oliver stonewalled her when she asked for agency records. Her relationships with other board members were fractious. Still, Kelleher inched the board toward further studies of flooding in other areas of Fort Worth, not only in downtown and the other places that the agency had treated as priorities.

“The water district started taking a much more proactive approach. If they knew that a lot of rain was coming, they would discharge depending on the levels of the lake,” she said.

Her critics still sought revenge. She was defeated in 2017, placing fourth among five candidates. But Kelleher ran again and won in 2021.

These days, the board sometimes has a kumbaya feel, with Kelleher often voting with the board majority. But she still dissents sometimes, usually objecting on eminent domain and equity grounds to what her fellow directors want to do.

Doreen Geiger is a longtime Democratic activist in Fort Worth. She’s also a founder, with Burnam, of the Water District Accountability Project, monitoring the agency’s dealings. They are regular visitors at the TRWD’s monthly board meetings.

Geiger has been a fan of Kelleher’s since she met her in 2013. “Mary is the best one on the board for a lot of reasons. She’s not there to financially benefit. She cares about water, flooding and good governance,” she said.

“Her being there has been critical,”

Burnam said, although he thinks she’s been too quiet in her second term.

Geiger hopes more members like Kelleher will be elected in May to the two at-large seats (of five) that are up for election. Members serve four-year terms, and elections are staggered. Kelleher is up for reelection in 2025.

For Kelleher, the top concern is not the next election but making sure North Texas has the water resources it needs and the policies in place to control flooding. “Water—you can’t live with too much of it, but you can’t live without it. I mean, it’s just probably the most important natural resource that we have,” she said. “We have to be good guardians of it.”

Freelance journalist James Russell of Fort Worth has written for state and national publications, including City Lab, Next City, and Arts and Culture Texas

The antics of Attorney General Ken “I’m still under indictment” Paxton could often earn a mention here doing his part to retain Texas’s tile as the “Strangest State.” But things got weirder than usual when Paxton asked lawmakers to fork over $3.3 million for a settlement with four ex-employees who are SUING him for firing them after they reported his illegal activities to the FBI. But legislators balked. Even weirder, the Texas Legislature wrote the law that makes the state liable for damages and granted officials like Paxton immunity from paying for their own misbehavior.

Since 1976, the Museum of East Texas has offered exhibits of art and sculpture in a historic building that once housed an Episcopal church. Museum officials often host inventive fundraisers, but after two long years of quarantine, they renamed their 2022 event the “Odd Ball,” inviting locals to don costumes and hats and act as weird as they wanted. For 2023, organizers prepared for lions, tigers, bears (and witches) since this year’s Odd Ball was set in Oz. Weeks in advance, tickets were already sold out.

Firefighters are used to rescuing pets from blazes, but members of the East Montgomery County Fire Department weren’t prepared for the menagerie trapped inside a Houston home in March 2023. “Albino pythons, milk snakes, chicken snakes, alligators. ... I don’t know all the different types of lizards, I just know there were iguanas, bearded dragons—you name it, she had it,” Captain Kyle Foster told FOX 26. The department published a photo on Facebook of one firefighter holding a rescued snake coiled around his muscular arm. “Not what you are expecting to hear but we will rescue your animals too if possible,” the department wrote.

Gabriel Arana & Michael Collis | Beatriz Pérez & Vincent LoVoi | Abi Mallick | Peggy & Matt Winkler Carol M. Barger | Carlton Carl | Lois Chiles | Marian & Paul Cones|

Roxanne Elder & Scott Borders

Kyle & Noah Hawley | The Neavel Family | Janis & Joe Pinnelli

Greg Wooldridge | Elliott Harris | Don Gardner & Pat Murfin (in memory of John Henry Faulk and Larry lee) Samuel England Carol Barger | Ramona Adams Wade Arledge | John Bailey | Thomas Belden Katy Bettner | Karen Brown

| Declan Dunne | Robert Frump James Galbraith Dicky Grigg Charlie Gustin | Emily Hartstein Melissa Hawthorne

David Lee | Elena Marks | Independent Media Arts Foundation Carol Messer Bill Minutaglio | Kimberly Moore Elliott

Naishtat Peter Ravella | Elizabeth Rowland | Ben Sargent | Katherine Sugg | Martha Wells

Pat & Bud Smothers | Blaine Wesner | Charles Zeller

Low-income Texans depend on family planning clinics. The clinics depend on a program that’s in trouble.

By: JULIE POOLE

Photography by: MERIDITH KOHUT

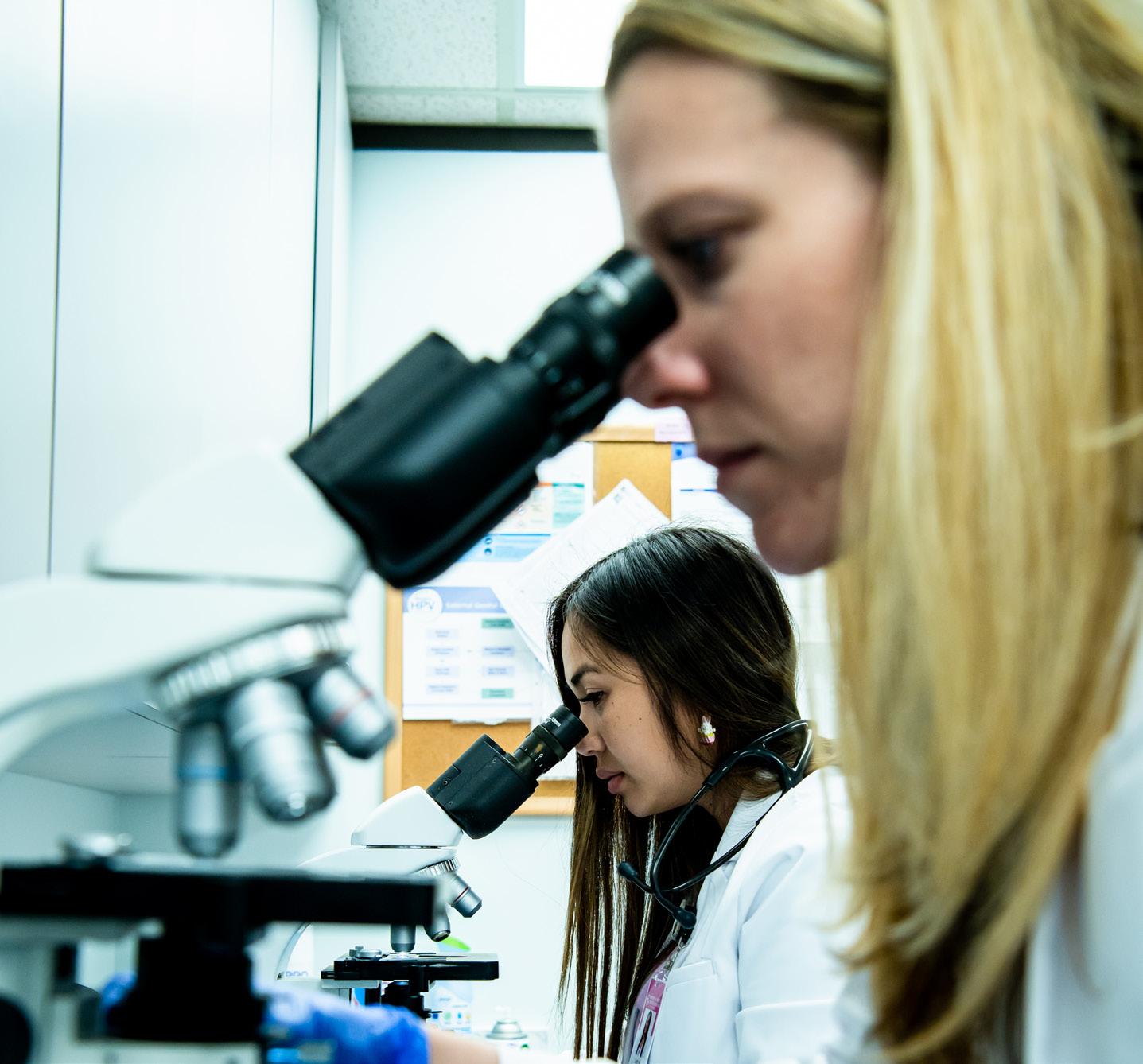

Certified medical assistant Letty Almazan helps family nurse practitioner Linh Nguyen with an exam at a Corpus Christi clinic.

By: JULIE POOLE

Photography by: MERIDITH KOHUT

Certified medical assistant Letty Almazan helps family nurse practitioner Linh Nguyen with an exam at a Corpus Christi clinic.

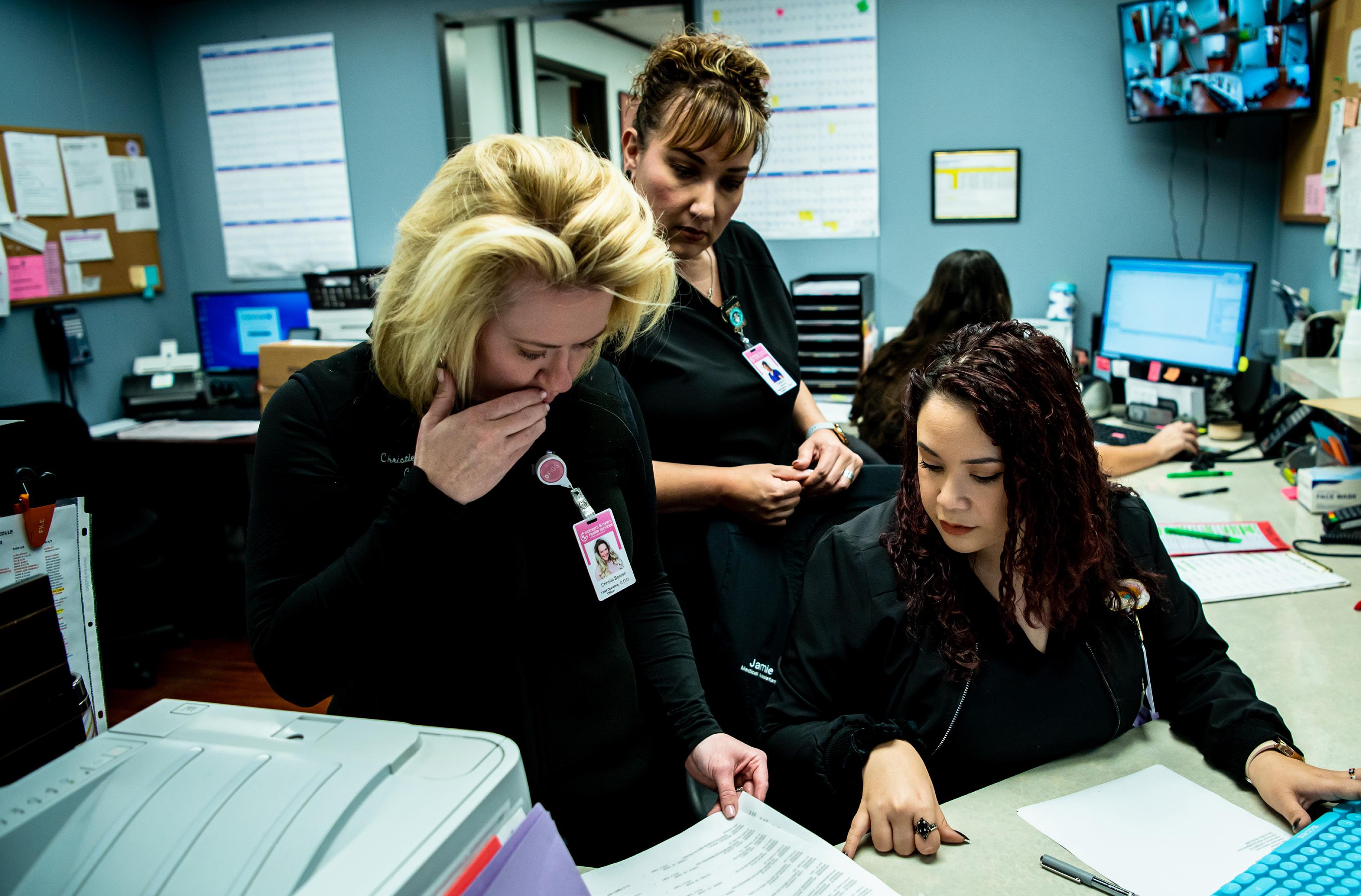

Mondays are Access Esperanza’s busiest days. Some of the women who come seeking care may wait for a couple of hours but, CEO Patricio Gonzales said, “We do not turn away patients.”

For his clients—most low-income and uninsured—waiting is worth it because the services are free.

Access Esperanza runs four family planning clinics serving roughly 15,000 patients a year in McAllen and nearby cities in the Rio Grande Valley where the average income is less than $20,000 per year. Gonzales said that for many of his patients, their yearly visit to one of his clinics may be the only time they even get their vitals checked. “We’re their only medical provider,” he said—it’s Access Esperanza or the emergency room.

In vast stretches of Texas, family planning clinics like Access Esperanza are a thin and threatened lifeline for low-income families. Getting any kind of healthcare can be difficult, especially in rural areas where the nearest hospital or clinic may be hours away and finding help to pay for it can be a nightmare. Until recently, patients could come in, fill out a relatively simple twopage application, and get care on the same day under a program called Healthy Texas Women (HTW). The program, which is the state’s largest safety net for reproductive healthcare, is a vital funding source for such clinics. It serves about 190,000 people a year.

In the past, clinic operators sent the applications off to the Texas Health and Human Services Commision (HHSC) in Austin and, usually within a couple of weeks, most were approved and the clinic was paid.

Not all the patients’ medical needs are covered by the program, but the basic screenings and exams save lives all the time—like the 55-year-old woman who came into Access Esperanza’s clinic in Mission “looking extremely pale, weak, and in need of a medical examination,” Gonzales said. Clinic workers determined she badly needed a blood transfusion and got her to a hospital ER. The next day, Gonzales got word that the clinic workers’ actions had saved the woman’s life.

But now the Healthy Texas Women program is unraveling, according to

providers and healthcare advocates interviewed for this story.

In March 2021, in the midst of the COVID19 pandemic and with little explanation to clinic operators, HHSC switched out the relatively simple HTW application for a 13-page application for Medicaid assistance. Things went downhill after that.

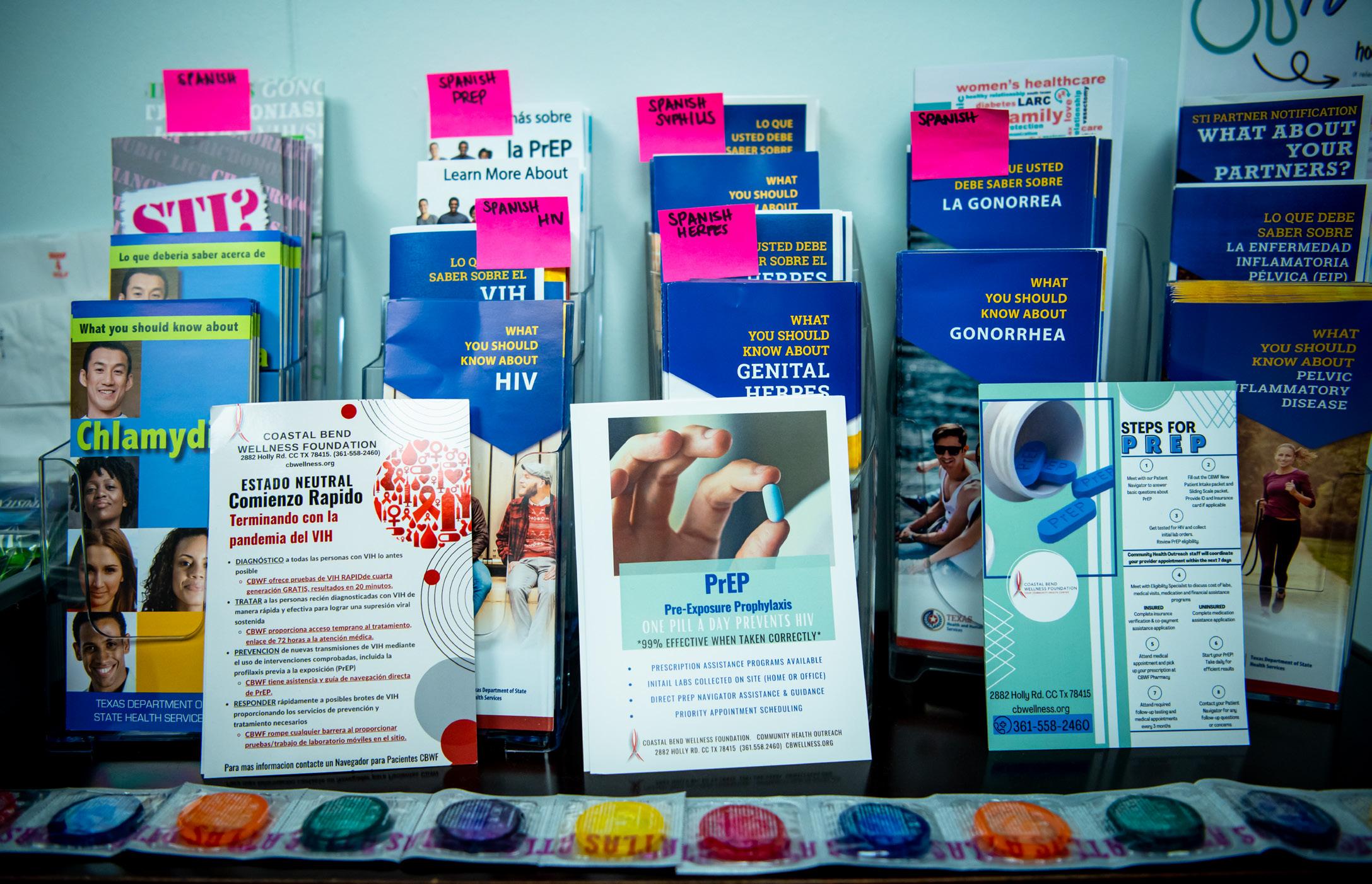

Family planning providers and others described the new paperwork as extremely complicated and, for many women, intimidating. As a result, they said, many applicants give up and go away, which probably means some will not get care anywhere else. Meanwhile, the health issues they bring to the clinics are often the kind that can’t wait. According to a state-generated report, the services most frequently sought by HTW applicants were treatment for gonorrhea and chlamydia or tests for pregnancy.

Gonzales said that, dating from the imposition of the new application, approvals of new HTW applications have ground to a near halt: Whereas most applications in the past were OK’d, now only about five out of every 100 are approved, he said.

That pattern has continued. Martha Zuniga, director of South Texas Family Planning, a nonprofit that operates six clinics in the Corpus Christi area, said that as of mid-February of this year, new HTW application approvals were down by 80-90 percent compared to that same time in 2021.

According to information provided by HHSC, in fiscal year 2020-21 application denials far outpaced approvals for women’s health programs in Texas—more than 461,000 were denied compared to about 292,000 approved and about 190,000 who actually received services.

There’s another problem: The speed at which HHSC either approves or denies applications has slowed tremendously. Whereas a turnaround of about two weeks had been standard, Zuniga said, some applications were still in limbo 45 or even 90 days after being filed.

That was a problem, Zuniga said, because such delays meant they couldn’t then bill that claim to another program. As a nonprofit with a mission to serve the uninsured and low-income population, she said, “We really do depend on those resources to work efficiently.”

In February, HHSC told Zuniga by email that until August 1 she will no longer have to hold pending HTW claims for 45 days before billing them to another funding source, the Family Planning Program. However, if Family Planning funding remains stagnant, this temporary reprieve won’t help much long-term.

The Family Planning Program, among other roles, acts as a fallback for clinics to get reimbursed for providing care to patients who can’t pay or whose bills don’t get paid by HTW or otherwise. When

a patient’s claim under HTW is denied, clinics can roll the unpaid claim over to that program.

Clinics contract with the state to receive lump-sum Family Planning grants on an annual basis, but the grants haven’t increased to keep up with the rising needs of people seeking care. As a result of that and the problems with HTW, grants frequently run out before the end of the fiscal year, and yet clinics are required by law to continue providing care to patients. Clinic operators can file “funds gone” claims with

the state—and then wait until sometime in the new fiscal year to be repaid, potentially adding months to the payment process.

All of this is threatening the financial viability of the family planning clinics that play a vital role in women’s healthcare in Texas. One provider said she already had to shut down one clinic last fall and suspend the operations of a second clinic temporarily.

Gonzales isn’t sure that the Healthy Texas Women program will make it through its current woes, and he knows that lives

are at stake. “I think [we’re] going to see this program bottom out, I hate to say this, by May or June,” he said.

Christina Bonner, chief operating officer of Women’s & Men’s Health Services of Coastal Bend, also got the OK for her clinics, for the next several months, to roll over HTW claims to Family Planning without delay. She said HHSC leaders and legislators have stepped up their advocacy for added funding for Family Planning and are looking for other ways to help. The clinics depend on HTW, and the lives

of low-income Texas women depend on those clinics. People like Brigitte Pittman and Erica Garcia Ginnett owe their lives to safety-net programs. In the case of Ginnett, a 34-year-old college student and mother of two young girls, South Texas Family Planning clinics in Kingsville and Corpus Christi saved her life twice—once after an ER doctor had refused to treat her uncontrollable bleeding and more recently when she developed breast cancer.

On March 8, the Corpus Christi clinic received a gift basket with things like juice packs, Lifesavers and Peeps candy, and a letter from Ginnett. “All of you are my lifesavers. You are my Peeps!” it said. “I can’t thank y’all enough for my life, because I might not have one if it weren’t for y’all.”

Stacey Pogue, a senior policy analyst at the nonprofit Every Texan, said that the clinics funded by the Family Planning Program (which also rely on Healthy Texas Women funding) “are the workhorses of the family planning network in Texas—they are the high-volume clinics, the long-standing clinics, they see a lot of

pregnancy testing, cancer screenings, and more. But when HTW applications are rejected or simply sit in the limbo of an HHSC backlog, the effect is to deny patients access to a program that has sufficient (mostly federal) funding and shove the costs of their care onto the underfunded Family Planning Program, thus increasing clinics’ financial woes. According to an HHSC report, the “funds gone” claims submitted by providers in fiscal year 2021 was $3.2 million—a figure that’s expected to rise.

For clinic operators, it has been a nailbiter. Waiting months for reimbursements can cause clinics to limit the amount of birth control packs provided to patients; cut doctors’ hours; struggle to cover rent, utilities, and salaries; and ultimately, close either temporarily or for good.

HTW into a Medicaid-funded program. The simple application had been negotiated away when the waiver was finally approved in January 2020.

According to HHSC Press Officer Tiffany Young, it was the federal agency that oversees Medicaid that forced the change in the application. Young said the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) insisted, as part of the waiver negotiations, that the new HTW application capture information needed to determine a number called MAGI—the patient’s Modified Adjusted Gross Income. Instead of basic income questions, applicants are asked to calculate the amount of their “pretax contributions per pay period, how often contributions are made, as well as the date contributed” for all members of their household.

people.” (Every Texan is the nonpartisan policy institute formerly known as the Center for Public Policy Priorities.)

Individual doctors make up the bulk of the practitioners who help provide reproductive healthcare to low-income Texans, Pogue said, but most reserve only a tiny fraction of their appointments for uninsured patients. Family planning clinics, on the other hand, serve low-income people almost exclusively.

To keep their doors open, the clinics rely on multiple funding streams: Healthy Texas Women, the Family Planning Program (which serves men and women), Breast and Cervical Cancer Services, and Title X, the federal program that provides affordable birth control and reproductive healthcare to low-income people. Each funding source is administered differently, and not all Texas clinics have access to the full range of funding. For patients without private insurance—the vast majority—clinics are required to screen first for Healthy Texas Women eligibility.

HTW patients can get annual exams, screenings for sexually transmitted infections, HIV testing, contraception,

For patients, moving claims to the Family Planning Program isn’t a great solution, Bonner said. “HTW as a health insurance is much more useful to a patient than the Family Planning Program because with [FPP], it’s not like you get a card that you can take anywhere. Whereas your HTW card is like private insurance. You can take it to any HTW provider.”

In September, Kristén Ylana, executive director of the Texas Women’s Health Caucus, organized a roundtable discussion to address concerns about the Healthy Texas Women program. Twelve clinic leaders from all corners of the state—Beaumont to Amarillo, the Rio Grande Valley to Dallas—made the trip to meet with legislators and HHSC officials.

Over the summer, a lot had transpired. In June, the U.S. Supreme Court had overturned Roe v. Wade. Providers with HTW funding are not allowed to provide or pay for abortions, but the decision affected them nonetheless: In May, when news of the impending decision leaked, clinics began seeing more patients seeking contraceptive care, a trend that has continued.

Gonzales and other providers were baffled about why the application had changed, when the simpler version was easier for both patients and staff. The reason, they learned, had to do with something called an 1115 Demonstration Waiver, submitted by Governor Greg Abbott in 2017 to turn

The tone of the form shifted as well, stressing that the patient is signing “under the penalty of perjury,” and that HHSC checks answers against “electronic databases and databases from the International Revenue Service (IRS), Social Security, the Department of Homeland Security, and/or a consumer reporting agency.”

If patients or their household members work informally at jobs where they don’t have to file income tax withholding forms, they’re at a disadvantage. So are people who work multiple jobs or who may have a hard time tracking down former employers for verification. If family members have clouded immigration status, patients may decide that completing the application is too much of a risk.

Providers noticed another issue: The 13-page application didn’t provide protection for victims of domestic abuse. On the simpler form, joint insurance information (with a parent or spouse) could be waived if the applicant was a victim of abuse, as are about 20 to 25 percent of patients seeking family planning care.

According to a CMS spokesperson, states can use a separate application for family planning coverage. But Texas chose to use the same application it uses for other Medicaid programs.

To complicate matters more, during HHSC’s negotiations with CMS a feature called “adjunctive eligibility” was stripped away. In the past, people who had

already qualified for other income-tested programs—like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or the Women, Infants, and Children supplemental nutrition program—automatically qualified for HTW. Now, however, they must submit the same documentation all over again.

The Healthy Texas Women program website is confusing. The “How to Apply” section says that applying for services is “easy” but also notes that the online application “works on desktop computers, but not on mobile phones or tablets”—a challenge for people who don’t have access to a computer or the internet.

Patients can download the form and print it instead, but that requires access to a printer. It also assumes they were able to find the form in the first place—there is no form labeled “Healthy Texas Women.”

Instead, it is listed under “Medicaid or CHIP, form H1205” (the 13-page version) or form H1010 (the 33-page version for HTW only).

Providers seldom know why applications

for HTW coverage are denied. Patients themselves get denial letters, but those may provide little information. In one case, a patient returned to share her letter with Access Esperanza. The letter didn’t list a reason, just six-digit codes. While at the clinic, the woman called HHSC to ask for clarification, Gonzales said, “but the wait time was over an hour, and she couldn’t complete the call.” A recording suggested she fill out the application all over again.

Clinic staffers help patients with applications, but extra visits to the clinic can be a struggle themselves, requiring childcare arrangements, time off from work, and reliable transportation. So clinic operators do their best to make healthcare a one-stop task. Bonner, of Women’s & Men’s Health Services of Coastal Bend, said her clinics offer gas cards and bus passes. Thanks to onsite pharmacies, women don’t have to make a return trip to get birth control supplies or to have IUDs inserted.

Gonzales said that when people first see the 13-page HTW form, their eyes widen. It takes patients as long as two hours to complete, pushing the overall visit time to four hours or more. “Sometimes people get

so frustrated they leave.”

Peggy Smith sees the same problem among the 13- to 24-year-old students she serves as CEO of Teen Health Clinics, a program run by Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. She said the application process for HTW coverage is incomprehensible and intimidating to young patients who are usually seeking birth control or STI treatment and who seldom have the family income information needed for the HTW form. That pushes their care costs onto the clinic’s Family Planning Program grant. When that money, as a result, ran out too quickly, Smith was forced to close one clinic and pause operations at another last fall. Three of her clinics are located in innercity high schools where few students have primary care doctors. Those schools are safety nets for such kids, she said, and also their “medical homes.”

Brigitte Pittman didn’t have a “medical home” until she found out about HTW, when she was more than a year into postpartum depression.

At the private Christian high school she attended in the Dallas area, Pittman said, abstinence was the only sex education taught. She was a college student before she learned about sexually transmitted diseases and birth control. Stephenville, in Erath County southwest of Fort Worth, where she went to college and still lives, has about 42,000 people, but according to the nonprofit group Power to Decide, not one publicly funded health center with a full range of contraceptive options is available. The group lists Erath County as a contraceptive desert.

Pittman was in her mid-30s—and the mom of three boys—before a friend told her about the Healthy Texas Women program. Pittman said the enrollment process was frustrating and difficult (she couldn’t find the short form online). But she got approved in 2017, kept up her eligibility by resubmitting information on her husband’s income every few months, and says HTW saved her life.

By 2017, Pittman had been without comprehensive healthcare for years, sometimes ending up in the emergency room “because I waited so long to seek help.” Her last pregnancy had been deemed high-risk: Her gestational diabetes had turned into long-term diabetes and her

postpartum anxiety had hung on. The dangers of another pregnancy have made her “highly uncomfortable [about] ever having more kids.”

Pittman said HTW gave her access to essential services such as birth control, annual exams, diabetes screenings and, finally, treatment for depression and anxiety. Now a single mom, she works from home for a company she likes and is training for a new position. Working from home gives her more time with her boys—a 12-year-old and 9-year-old twins.

Pittman was nervous and excited in February when she spoke in front of the Capitol for the first Texas Women’s Healthcare Coalition Advocacy Day. “I know that it”—HTW saving her life—“sounds like a stretch to say right now,” she told the audience. “I was in such a dark place.”

In October 2022, HHSC Deputy Executive Commissioner Wayne Salter told a Texas House panel on healthcare reform that 400 staff vacancies at his agency had led to a backlog of 70,000 Medicaid applications over 45 days old. By mid-February of this year, according to HHSC, that backlog had grown to 159,860 applications.

Also in February, Young, the HHSC press officer, said there is “currently no backlog for HTW-only applications. However, if an individual applies for HTW and other programs or Medicaid and other programs, HHSC must first assess eligibility for Medicaid programs before determining eligibility for HTW. There currently is a backlog for these types of applications.”

When the Texas Observer asked for clarification about HTW-only applications, Young pointed to form H1010, by which a patient can agree to forego other benefits and just apply for HTW. That would be faster, right? Apparently not. Young noted that Texas still requires all applications to go through a tiered screening system that checks patients for eligibility for Medicaid and another program as well as HTW. In short, there is no fast track for individuals just seeking help with birth control and STI screenings.

Zuniga, of South Texas Family Planning, pointed out that if HHSC was behind in processing applications, it would have been helpful for providers to know earlier.

“Providers like us are the backbone for the uninsured and low-income,” she said. “We are where they come and who they trust.”

Another bureaucratic threat is also about to hit the family clinics and their patients. The pandemic-related federal waiver that had extended Medicaid coverage for about 2.7 million Texans—mostly children and mothers—expired on March 31. HHSC has now begun a federally required review of the state’s entire Medicaid rolls, about 5.9 million people. Advocates fear that the health agency, already dealing with staff shortages and application backlogs, may be overwhelmed by the task.

If the path to family planning healthcare in Texas seems filled with potholes, it’s partly because the route goes through the battlefield of abortion.

Many of the holes in the healthcare coverage system for women in this state were once filled by Planned Parenthood health centers. But Republican state leaders fought a long and ultimately successful legal battle to bar Planned Parenthood—and any other organization associated with abortion—from receiving state-managed healthcare funds in Texas.

In 2011, the state cut funding for family planning programs from $111 million to less than $38 million. When Texas asked the Obama administration for a waiver that year to allow its Medicaid-funded programs to bar abortion providers from participating, the request was denied.

The Trump administration had no problem with the state excluding any abortion provider (or its non-abortionproviding affiliates) from Medicaid funding and approved the waiver. Before the Texas Legislature went after their funding, Planned Parenthood health centers “provided care to more than 40 percent of Texas’ Medicaid women’s health program patients,” said Sarah Wheat, chief external affairs officer at Planned Parenthood. Texas policies on women’s healthcare now are “a mess with lots of detours and roadblocks,” she said.

The waiver that denied funding to Planned Parenthood clinics will expire at the end of 2024. HHSC officials plan to seek a renewal. But Texas’ justification for banning an organization that no longer provides

abortions in the state is wearing thin.

Some clinic operators and women’s health advocates see glimmers of hope for Texas’ family planning clinics and the Healthy Texas Women program.

Pogue, for instance, is optimistic about legislation that would increase access to care: Senate Bill 807 would require health insurers to give patients the option of receiving 12 months of birth control supplies at one time.

House Bill 141 would make contraception available through the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Texas is one of only two states that don’t do that now, even though the program covers young people up to age 18 and part of their 19th year.

Kristen Lenau, health policy director with the Texas Women’s Healthcare Coalition, pointed out that the basic state budget proposal for the next two years includes $87 million—a 25 percent increase—for women’s healthcare programs.

Smith, CEO of Teen Health Clinics in Houston, is hoping Texas will adopt a

fast-track application for young patients. She knows of two states, Oregon and Mississippi, that use a two- page form that’s simple enough for underserved youth to fill out.

Bonner is hopeful that the proposed increase in funding for the Family Planning Program and possible midyear allocation to the program will help close her clinics’ funding shortfall created by Healthy Texas Women’s bureaucratic challenges.

“The new 13-page HTW application is an outrageous barrier to care, when you consider how limited the services it provides are, but HHSC is assisting providers in finding ways to work around it,” Bonner said.

Ayear ago, it seemed unlikely that Erica Garcia Ginnett would live long enough to watch her kids grow up.

Ginnett is a journalism student at Texas A&M UniversityKingsville who’s also active in theater. Her daughters are now 8 and 12. She was rehearsing a play in March 2022 when another actor shoved her during

a scene. As she pushed back, she felt a sudden loss of blood that soaked her pants. She’d been experiencing uncontrolled vaginal bleeding that had worsened over the course of a year, but this was urgent. Her husband, an EMT, was there and rushed her to the ER, where the doctor confirmed what the couple already suspected: Ginnett had a prolapsed uterus. She was prescribed birth control to help slow the bleeding, but a couple days later she lost consciousness after stepping out of the shower. That led to another ER visit, at which she saw a different doctor—or actually, he refused to see her, saying that someone so young couldn’t possibly have a prolapsed uterus. A concerned nurse practitioner encouraged Ginnett to go to another location where the practitioner worked, the local South Texas Family Planning Clinic. There, the nurse practitioner examined her, confirmed the prolapsed uterus, and prescribed a different birth control and a Depo-Provera shot to get the bleeding under control. And clinic staff helped her sign up for Healthy Texas Women coverage. It was wonderful, Ginnett said, to find

Informational pamphlets about sexually transmitted diseases are available free at the Corpus Christi clinic.

“organizations that are there to help people who don’t know the system, don’t know what routes you have to take, what forms you have to fill out … and they say, ‘Come sit in my office and let’s work on this together.’”

Ginnett and her husband couldn’t afford health insurance through his employer; the $800 biweekly premiums would have eaten most of his paycheck. Their kids are on CHIP. She had tried earlier for Medicaid benefits but was only approved for them during her pregnancies. Without continuing Medicaid help, she had lost her regular OB-GYN care. In September, Ginnett found a lump in her left breast. The nurse practitioner at South Texas Family Planning recommended she get it checked out. When doctors found that the lump was cancerous and recommended a partial mastectomy, the clinic staff helped her to enroll in the Medicaid for Breast and Cervical Cancer program. Two months later she had a partial mastectomy. Unfortunately, because her cancer was estrogen driven, she had to stop taking birth control, which brought back the uncontrollable bleeding and led to anemia. She was grateful that her Medicaid policy covered a full hysterectomy in February.

She’s about to head into five years of chemotherapy, just as the unwinding of Medicaid in Texas begins. She’s less concerned about losing coverage herself— she’s been assured she won’t—than about her kids who need to stay on CHIP for their medications.

When Ginnett was able to begin seeing a gynecologist regularly through Medicaid for Breast and Cervical Cancer, she finally learned that the bleeding had been caused by a large fibroid tumor in her uterus, which was found after her hysterectomy. When she dropped off the gift basket at the South Texas clinic’s Corpus Christi location, Ginnett hugged the staff member who accepted it, and cried.

Ginnett said she hopes that people looking for healthcare won’t get discouraged.

“You’re going to get a lot of ‘No’s’ when you’re searching for something, but when you finally get the ‘Yes, I can help you,’ the ‘Yes, I know what we need to do,’ it’s worth it,” she said. “Because it means your life. It’s the difference between getting to see your kids graduate from high school or not.”

A bizarre Dallas case involving the alleged impersonation of a judge on Zoom tests the state’s opaque system of judicial accountability.

By: MICHELLE PITCHER

By: MICHELLE PITCHER

Illustrations by CLAY RODERY

ike most judges, Amber Givens moved much of her court’s business online as the pall of COVID-19 hung over Dallas in the summer of 2021. On August 3, what initially seemed like a routine Zoom meeting with lawyers turned into the impetus for a prolonged public and legal drama with the 43-year-old district judge at its heart.

Givens, who has presided over the 282nd District Court in Dallas since 2015, had trouble logging in to her Zoom account that morning, a familiar woe for all who transitioned to virtual work during the pandemic. It didn’t seem like too much of a problem—she had a relatively light docket that day. One meeting involved a man named Floyd Aaron, who’d been accused of violating the conditions of the deferred adjudication of his 2015 burglary charge.

Before the meeting, Givens asked her court coordinator, Arceola Warfield—known by many regulars at the courthouse as “Arce”—to log into the judge’s account and announce that the judge would participate via speakerphone, according to affidavits obtained by the Texas Observer.

Longtime defense attorney Tim Jefferey, representing Aaron, attended the Zoom meeting while Assistant District Attorney Eduardo Carranza represented the state. A handful of others, including probation officers, logged on.

Some participants understood that Warfield, the court coordinator, continued to use the judge’s Zoom account, although the video was off and a photo of Givens appeared onscreen. To courtroom regulars, Warfield’s voice sounded distinct from Givens’ confident, orotund tone. At one point, the coordinator asked the court reporter to go on the record—something the judge normally does.

At least one lawyer said it wasn’t clear Warfield was the one behind the Zoom picture—during the meeting, the defendant addressed Warfield as “your honor” on at least one occasion—and word of this ambiguity made its way to leaders of the Dallas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association (DCDLA), which represents more than 600 lawyers. The group’s board of directors filed a formal complaint against Givens with the State Commission on Judicial Conduct, alleging that Givens had instructed her court coordinator to

impersonate her.

Givens has denied that she instructed her employee to impersonate her, calling the allegation “absurd,” according to the Dallas Morning News.

In an affidavit, Warfield later said her request to go on the record was tonguein-cheek. “I jokingly said to Lisa Jackson, our court reporter, ‘Let’s go on the record.’ This was a joke because I said it after Judge Givens told the parties she was getting off the call,” Warfield wrote. “I recall that several people in attendance on the Zoom call laughed in response.”

Other participants in the Zoom call— including court reporter Lisa Jackson and Dallas County sheriff’s deputies Kenneth Brame and David Podraza—also provided sworn statements saying they knew the voice behind Givens’ photo was her staff member.

“Arceola Warfield never presented herself as Judge Givens,” Podraza said in an affidavit. “When she was addressed as ‘Judge,’ Arceola Warfield quickly corrected and identified herself as ‘Arce.’”

The accusations spurred the Public Integrity Unit of the Texas Rangers to launch its own investigation, which is ongoing.

Dallas County District Attorney John Creuzot recused himself from investigating the claims, leaving the task to the DA of nearby Kaufman County. Creuzot and the Texas Rangers declined to comment.

But this wasn’t the first time the DCDLA had raised concerns about Givens. The group lodged at least three previous complaints about the judge’s behavior toward attorneys and about the way she streamed hearings on Facebook. In part because of the number of attorneys involved with the complaints, Givens either recused herself or was removed from a staggering number of cases in 2022. Ray Wheless, the administrative judge in charge of the region since 2018, told a Dallas news station, “I’ve never seen this many recusals in one county. I’ve never heard of it, never seen it.”

Behind the scenes, prosecutors have joined defense attorneys in criticizing Givens’ courtroom behavior. In March, prosecutors in a high-profile murder case requested Givens be removed from the trial, claiming she was biased against the state based on her courtroom comments. Voters, on the other

hand, have continued to back her.

Givens, who took home $172,000 annually as of last year (the maximum pay allowed by law for a judge in her position with her experience) was elected to her third term in 2022. Givens provided publicly filed documents but declined to comment further. But she told the Dallas Morning News, “These claims are unsubstantiated” in a statement issued in response to the 2021 complaint. “This is a false narrative motivated to suppress the will of the community and to pressure me to discontinue the progress we are making toward change in the court system.”

The situation in the Dallas County Courthouse remains tense as defense lawyers and prosecutors who want Givens off the bench wait for the results of multiple investigations.

So far, both sides seems to be trusting the process.

But Givens’ critics say the drawnout criminal and judicial misconduct investigations are only worsening the damage in Dallas courts. In contrast, Givens and some supporters suggest that the way the allegations against her have been made public show how the Texas judicial accountability system, normally bureaucratic and secretive, can be weaponized.

The pandemic has ushered in its share of unusual judicial misconduct complaints. Just last year, the commission disciplined judges in 78 cases. In February 2022, Clyde Black, a justice of the peace in Houston County, was publicly admonished after he said he would release anyone brought into court for violating the “stay at home” orders imposed in the pandemic’s early days. In April, Barbara Stalder with the 280th Family Protective Order Court in Harris County was reprimanded for ordering attorneys to be shackled during court proceedings. Judge Bonnie Rangel with the 171st District Court in El Paso County received a public warning in August based on complaints that she verbally abused attorneys—in one instance yelling at lawyers for 20 minutes during a Zoom hearing.

All of these decisions came from the State Commission on Judicial Conduct, a

—Kim Nail

I want to live in the negative space of your landscapes, recede into shadows on the horizon soft like an echo, a ghost note. Desert mother, I see you cloistered in your Model A in a swarm of bees, painting fever dreams in gold and ochre—

I want to be still. I am a lens, setting fires in the sand with insolent focus. Teach me to be an aperture, quiet and clean as bleached bones, speaking only to water.

Dallas poet and educator Kim Nall co-curates and emcees the Raising Our Voices Alumni Reading Series for Carlow University, from which she holds an MFA degree.

13-member appointed board responsible for holding elected judges accountable in Texas. Every state has some form of judicial conduct oversight body meant to determine whether elected or appointed jurists violate laws, judicial canons, or ethical norms. Texas’ commission was established via a constitutional provision in 1965. The commission is made up of unpaid appointees who serve staggered six-year terms. A considerable portion of the commissioners—judges, attorneys, and nonlawyers—are avowed Republicans (the governor, the Texas Supreme Court, and the

said she’s certain that some of Abbott’s staff and lawyers knew how she’d voted because of questions they asked her in a meeting held afterward. In response, she asked if they were expecting her to vote in line with Abbott’s views because she was an appointee. They told her they would never try to direct a person’s vote. “Well, that’s exactly what it sounds like you’re trying to do,” the member said she replied. Her nomination was revoked just two months after the meeting.

In 2022, the agency had 14 full-time employees—including attorneys and investigators—who do the legwork of sifting through, analyzing, and investigating complaints. But it’s understaffed, and its leadership claims its $1.2 million budget is a stretch for its growing workload. New York State’s Commission on Judicial Conduct has a budget over $7 million, and the agency reported receiving about the same number of complaints as Texas as of 2021. Last year was the first time since fiscal year 2018 that the Texas commission managed to dispose of more complaints than were filed. By the end of FY 2022, only 169 complaints had been pending a year or more, a significant decrease in its prior backlog.

But in the FY 2022 report, Chairman David Schenck—a Dallas appellate judge who was appointed to the commission by the Texas Supreme Court in 2020—warned the small agency won’t be able to keep up that pace.

state bar all appoint members).

The political nature of these appointments is sometimes obvious: In 2019, Governor Greg Abbott revoked the nominations of two members—who served several months while awaiting Texas Senate confirmation—after they voted to sanction a Waco judge who had refused to conduct same-sex marriages.

One of those members, who asked not to be named, said there is “no question” in her mind that she was removed because of how she voted. Commission votes are supposed to be secret, but the member

“The Commission’s recent high level of productivity is not likely to be sustainable given current staffing levels. Our commission oversees far more judges than its … counterparts in other large states, and yet it operates with a fraction of the authorized staff,” he wrote. The commission already spends most of its budget on staff and travel, but also must shell out money to hire outside counsel to defend itself against two lawsuits after Attorney General Ken Paxton declined to help. Schenk said he was unable to speak with the Observer due to statutory limitations on his public comments.

The commission resolved a record number of complaints—2,229—in FY 2022. Its workload grew in part because of a constitutional amendment Texas voters passed in November 2021 that expanded the agency’s authority to include candidates

for judicial office.

In some ways, the judicial accountability system mirrors the court system over which judges preside. But key differences contribute to the massive caseload for the agency’s relatively small size. Complaints to the commission can arise from anywhere, including news stories. Unlike in civil court, people can file complaints anonymously or on someone else’s behalf since the commission does not “require a complainant to have firsthand knowledge of the alleged misconduct.” In Givens’ case, the DCDLA board as a group submitted complaints related to the judge’s treatment of individual defense attorneys and prosecutors. Nationwide, more than 90 percent of

named), a recommendation to the Texas Supreme Court for the judge’s removal, or even a referral for a criminal investigation.

The commission issued 40 public sanctions and 38 private sanctions. Two judges were referred to law enforcement for potential criminal charges.

Action is most common against justices of the peace and slightly more rare against district court judges—powerful jurists who handle the state’s felony criminal cases, including death penalty trials, or oversee high-stakes civil disputes. Twenty-five of the 856 complaints issued against district judges in FY 2022 resulted in disciplinary action.

“Judicial conduct commissions hold an awkward position in the justice system,”

take action against a judge directly rather than just making recommendations to the Texas Supreme Court. It’s one of 34 state commissions that keeps complaints confidential until the commission finds probable cause that misconduct occurred, according to the National Center for State Courts. Oregon is the only state that allows hearings to be public—in most other states, proceedings generally remain confidential unless the commission recommends public discipline or until the Supreme Court issues an order.

For all its power, the body has precious little oversight. The agency has argued that it’s immune even from review by the Sunset Advisory Commission, which evaluates the

complaints submitted to state judicial misconduct commissions get dismissed, often because complainants asked agencies to weigh in on something outside their jurisdiction, according to Cynthia Gray, director of the Center of Judicial Ethics at the National Center for State Courts. And this is a crucial point: These commissions remain leashed in order to protect the independence of the courts. Only about 1 percent of filings result in judges stepping down or being publicly disciplined, and nine out of 10 misbehaving judges kept their jobs after committing misconduct, according to investigations by NBC News in 2021 and Reuters in 2020.

In FY 2022, only 78 of the 2,229 complaints (about 3 percent) disposed of by the Texas commission resulted in disciplinary action—which can include everything from a private sanction (where the judge is not

writes Gray in a paper titled “How Judicial Conduct Commissions Work.” “The public, pointing to the high complaint-dismissal rate, accuses them of white-washing judicial misconduct. The media generally discovers them only in the event of a scandal, accusing them of being secretive and obscure. Some judges accuse them of engaging in witch hunts and acting as kangaroo courts or Star Chambers or, at most, grudgingly accept them as a necessary evil.”

But Gray told the Observer that she’s never heard of another complaint like the one against Givens. “No judge has been publicly disciplined for having a staff member impersonate her during a Zoom meeting, and I have not heard of any other allegations of a judge doing that,” Gray wrote in an email.

The Texas commission, and similar bodies in 21 states, are empowered to

efficiency of other state agencies.