Hitting a brick wall

The premises crisis facing GPs

Escape from Sudan

NHS doctors found themselves stranded

Van with a plan Drive to boost prostate checks

Root cause Doctors tackling the climate crisis

Welcome

Phil Banfield, BMA council chair

It has been heart-breaking to see the horrors unfolding in Sudan as a result of brutal power struggles within the country’s military leadership. Our thoughts are with the people of Sudan during this period of great anguish and pain. It has been particularly hard to see cases of NHS doctors being trapped – and even turned away from evacuation flights.

The BMA has urged the Government to do all it can to ensure the safety and the rescue of all NHS doctors who give so much to patient care in the UK. In this issue of the magazine we hear from doctors who have found themselves at the heart of the conflict – their eye-opening stories include a perilous 12-hour bus journey, fleeing to other countries, and the terror of bomb explosions in neighbouring buildings. The BMA is working with NGOs and Sudanese doctor organisations to help raise awareness and much-needed funds too.

Here in the UK our growing workforce crisis leaves more and more doctors burning out, quitting or hanging on day to day amid staff shortages, rocketing demand and dwindling resources.

This strain is particularly true of our colleagues in primary care who are provably and demonstrably working harder than ever – yet they continue to face vilification from the media and Government, often leading to criticism and abuse from patients.

In this magazine we constantly highlight the reality on the front line. We visit GP surgeries in Coventry to find out how practices are being left behind in tired and crumbling buildings in dire need of expansion and investment.

We delve into some good news stories where the NHS is making positive progress towards its net-zero emissions targets, hear about the healthcare being delivered in the car park of Croydon’s IKEA, and analyse the challenges facing forensic medical examiners in increasingly fragmented and stretched health services and judicial systems.

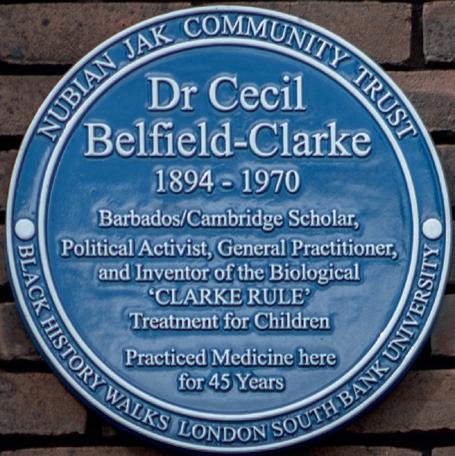

We pay tribute to Cecil Belfield Clarke – a truly remarkable doctor, one of the first black medics in the UK, a passionate civil rights activist and the man responsible for the eponymous Clarke’s rule in paediatrics. Dr Clarke’s legacy was recognised last month with the unveiling of a historical London blue plaque at the former site of his capital practice.

This month the BMA will ballot consultants on industrial action. Your BMA will continue to stand up for doctors and for our NHS.

Keep in touch with the BMA online at instagram.com/thebma twitter.com/TheBMA

Senior doctors open strike ballot

Consultants have opened a formal ballot for industrial action as other branches of practice ramp up their campaigns for fair pay and working conditions.

The ballot opened on 15 May after the Government failed to offer a substantive proposal to fix pay and the pay review process. If it is successful, consultants will offer staffing levels comparable to Christmas Day on strike days.

Consultants have seen an average 35 per cent fall in real-terms take-home pay since 2008/09. If a 10-programmed activity consultant’s pay packet had kept pace with inflation, they would earn £31,000-£42,000 more than they do now –the equivalent of four months’ pay.

The BMA consultants committee wants the Department of Health and Social Care to make an acceptable pay award offer for 2023/24 and reform the Review Body on Doctors’ and Dentists’ Remuneration.

CC deputy chair Mike Henley said: ‘The impact of this pay erosion is hugely significant.’ He noted recent ‘significant improvements to pension taxation’ but said: ‘It is still imperative we fix pay, now and for the future.

‘This can still be fixed – and must be fixed for good, if the Government addresses your concerns, industrial action can still be avoided.’

Meanwhile, consultants in Northern Ireland are to open an indicative ballot on 22 May.

The actions come as junior doctors in England announced a third round of strike action, which is scheduled if the Government fails to make a credible offer the BMA junior doctors committee

RUNSWICK: ‘A real shame it’s taken strike action to get Government to the table’

can take to its members.

Emma Runswick, deputy chair of BMA council, pointed to the Government’s ‘trudging’ pace of negotiations at a Commons select committee evidence session on 9 May.

She told MPs: ‘The dispute could be over tomorrow, with no further strike action. It’s a real shame that it’s taken strike action to get Government to the table on this issue.’

Junior doctors in Scotland are threatening to walk out for 72 hours after 97 per cent voted in favour of taking strike action on pay, from a turnout of more than 71 per cent, in a ballot that closed on 5 May. Negotiations with the Scottish Government are under way.

BMA Scottish junior doctors committee chair Chris Smith said: ‘We are no longer prepared to stand aside, feeling overworked and undervalued.’

Meanwhile, GPs voted to ballot for industrial action in England in the coming months if the Government does not renegotiate ‘disastrous’ contract changes imposed on doctors.

By Ben IrelandNO SAFE PASSAGE

Amid a growing humanitarian crisis in Sudan, NHS doctors who were visiting the country found themselves trapped, without the support they expected from the British Government. Seren Boyd reports

Sudan’s tentative steps towards democracy have taken a dramatic wrong turn.

The nation which threw off military dictatorship four years ago is now trapped in a power struggle between the two generals who ousted President Omar al-Bashir.

Civilians have been caught in the crossfire between the Sudanese army and the paramilitary RSF (Rapid Support Forces) – and a growing humanitarian crisis.

Up to 70 per cent of hospitals in conflict areas are closed, mostly owing to lack of supplies, water and electricity, according to the Sudanese Doctors Union.

Hospitals have been bombed, ambulances attacked, medical supplies looted.

The few facilities still functioning – often without

power or water – are overwhelmed. Medical supplies are desperately low.

‘Most of the doctors who are working in the hospitals are volunteers: surgeons, doctors, nurses, and some people from the community trying to assist,’ says Sudanese doctor Khalid Elsheikh Ahmedana of medical charity MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières).

The Turkish Hospital in Khartoum, which MSF supports, has set up about 30 beds for the war-wounded. Some days, it needs twice that number.

Dr Elsheikh Ahmedana fears the health crisis will escalate rapidly: water is scarce, dengue fever widespread.

‘There are dead bodies outside, and rubbish is gathering along with flies and mosquitoes,’ he says.

The MSF-supported hospital in El Fasher, North

‘We were woken up by cannon fire, missiles and gunfire’

Darfur, is the only functioning health facility for half a million residents.

Many of the war-wounded require surgery and blood transfusions: people with now unmanaged conditions such as diabetes are becoming seriously ill.

The violence means many simply cannot get to hospital.

‘Some people trying to access the hospital are telling us they’ve become trapped: they can’t reach the hospital or go back to their homes,’ says MSF’s Dr Mohamed Gibreel Adam.

‘People are dying in the community.’

Impossible choices

At least 78 NHS doctors who had travelled to Sudan to celebrate Eid with family found themselves trapped in a war zone.

Consultant cardiologist Mustafa Al Hassan, a British national, was holed up in the family home in Khartoum for 10 days, mostly without power or water.

‘We were woken up on Saturday 15th [April] by cannon fire, missiles and gunfire,’ says Dr Al Hassan. ‘Houses around us had stray missiles hitting them: our neighbour’s daughter died from a stray bullet while she was out in the garden.

‘The only response we got from the British Embassy was to “stay indoors and stay safe” but people were dying in their homes.’

Dr Al Hassan, his mother and brother eventually secured overpriced bus tickets to the Egyptian border. An email from the Foreign Office about the RAF evacuation plan arrived the morning they left Khartoum.

Dr Al Hassan stayed in Cairo with his mother for several days until his brother, initially denied entry to Egypt, could join them. Dr Al Hassan has since returned to work in the UK – but is applying for his mother to be able to come to Britain as his dependant. Several other NHS doctors face the same predicament.

‘She wants to go back to her home: I’ve been working in the NHS since 2007 and she’s never wanted to live here. She just needs a place of safety.’

Perilous escape

Shaza Faycal Mirghani, a French-Sudanese surgical trainee based in the Midlands, is one of many doctors in the UK who have lobbied for relatives and colleagues caught up in the conflict.

Her own daughters, aged two and five, were visiting Khartoum with relatives when fighting broke out. They were airlifted out to Djibouti by the French as the family have dual nationality – but not before enduring an

anxious few days.

‘The RSF were stationed just outside the door and the house just behind our house was hit by a bomb,’ says Dr Faycal Mirghani.

‘The RSF questioned my brother one night: that’s the point they decided to leave.’

Dr Faycal Mirghani’s family had to make a dangerous car journey to the French Embassy, but thereafter had a military escort.

The British response compares poorly.

The RAF began airlifting out British nationals and their immediate dependants on 25 April – days after embassy staff were extracted.

People were told to find their own way to Wadi Saeedna airfield beyond Omdurman, Khartoum’s twincity – at their own risk.

Dr Faycal Mirghani, a member of the Sudanese Junior Doctors Association, says that in the absence of a British evacuation plan, many made their own escape.

One NHS doctor, who asked not to be named, made the perilous 12-hour bus journey with her family to Port Sudan on the Red Sea coast. Her baby and toddler are British nationals: she and her husband have indefinite leave to remain.

But when they arrived in Port Sudan, the Foreign Office said they needed to return to Omdurman for evacuation.

‘I felt that the country that had been my home for the past six years didn’t value me,’ she says.

They were eventually evacuated from Port Sudan by the Saudis.

After pressure from the BMA, foreign secretary James Cleverly reversed an earlier decision and let NHS doctors with British residency permits and their dependants board evacuation flights.

But the distress continues: many NHS doctors have relatives in Sudan. At the time of writing, at least three NHS doctors were known still to be in Sudan: one caring for a pregnant sister, two looking after relatives made homeless in the fighting.

‘I felt that [the UK] that had been my home for the past six years didn’t value me’

ROOT CAUSE

Against the dark clouds, it’s easy to miss the good news stories unfurling across the NHS. They tend to be small and local – and green.

Trials are under way using drones to fly chemotherapy medicine across the Solent to the Isle of Wight, and electric ambulances have been pressed into service in north-west England and the Midlands. A hospital near Hull is now fully powered during the daytime by an 11,000-panel solar farm.

These innovations are still in their infancy, but the NHS is making good progress towards its net-zero emissions targets. It must: the NHS accounts for more than 4 per cent of the UK’s emissions. And it needs to change faster.

The worsening health effects of the climate and environmental crises are impossible to ignore. Last year’s summer heatwaves caused 2,800 excess deaths among those aged 65 and above in England alone; extreme heat on 19 July crashed IT servers at Guy’s and St Thomas’ hospitals in London, causing chaos for weeks. Food supplies shrivelled on their stalks.

Last year’s report by England’s chief medical officer Chris Whitty said poor outdoor air quality contributes to 36,000 deaths a year in the UK.

The heated debate about global warming can be overwhelming. But there is a large and growing band of sustainability champions in the NHS – including many doctors – who are determined to remain optimistic and to see challenge as opportunity.

‘The climate and ecological crisis is the defining health crisis of our time,’ says climate campaigner and public health registrar Anya Gopfert. ‘Whether you choose to make it part of your job or not, it will become part of your job.

‘We need major change, with everybody on board. Every bit of decarbonisation we achieve, every bit of warming we prevent, it all helps. And there are huge benefits: much of the change we need to see to make healthcare more sustainable is doing less but doing it better.’

Better-quality care

Frances Mortimer left clinical medicine, reluctantly, to devote herself to helping the health service become more environmentally responsible.

She helped set up the CSH (Centre for Sustainable Healthcare) in Oxford in 2008 and as its medical director works with all levels of health systems, from individuals to specialties to organisations, to help ‘mainstream sustainability’.

CSH’s work is wide-ranging, everything from establishing fellowships to support specialtyspecific research into greener practice and process, to helping health sites create green spaces as part of an NHS Forest, to helping trusts develop green plans.

Among the innovative pilots it has supported, often in the context of inter-team competitions, are many ‘Green Surgery’ projects. For example, the Leeds Global Health Research Group has designed a mechanical device that enables keyhole appendicectomy without the need for medical gases, which have a large carbon footprint.

As well as focusing on low-carbon alternatives, there is also a strong emphasis on streamlining care and processes. A CSHsupported pilot in Southampton which trialled early mobilisation and intensive physio for heartsurgery patients was found to reduce patients’ time in resource-intense ICU, for example.

Dr Mortimer says interest in sustainable healthcare and CSH support has grown rapidly over the past three years.

Yet, the picture is patchy: almost a third of trusts surveyed recently by the BMA were not monitoring their emissions – and 16 per cent of

MORTIMER: Interest in sustainable healthcare has grown rapidly

‘Every bit of decarbonisation we achieve, every bit of warming we prevent, it all helps’

Making the health service more sustainable will improve not only the environment but the nation’s health, and everyone has a role to play. Seren Boyd reports

trusts that were monitoring emissions in 2020 had stopped doing so in 2021.

For those more wary about ‘going green’, CSH’s strong emphasis on quality improvement is surely compelling: all projects are assessed on their health outcomes as well as financial, social and environmental cost savings.

‘Most people don’t disagree that sustainable healthcare is a good thing,’ says Dr Mortimer. ‘They just don’t have time to think about it. Or they think it’s going to be about a recycling bin. It’s about showing them what’s achievable, what others are already doing. But if we don’t connect it to better quality care, it isn’t going to have traction because that’s the prime motivation for the whole health service.’

Partnership with patients

Primary care is a relatively minor contributor to the NHS’s carbon footprint but its potential to contribute to wider change is significant.

GP registrar Advaith Gummaraju is an enthusiastic advocate of the Green Impact for Health Toolkit, created by the Royal College of GPs, which has helped him and his colleagues at their Oxfordshire surgery become more sustainable.

The practice uses a council-owned building, but they have been able to make swaps such as LED lighting and recycled paper, as well as cuts in energy and PPE use. They’re also committed to low-carbon pharmaceutical options, where appropriate: dry-powder inhalers are 25 times less polluting than metered-dose inhalers, for example.

But it’s the potential for influence through the closer doctor-patient relationship in primary care that most excites Dr Gummaraju.

A large part of sustainable healthcare is health promotion and prevention – or what Dr Mortimer of CSH refers to as ‘helping patients be partners in their own care’.

Dr Gummaraju believes helping people understand the links between human and

planetary health can help them adopt better lifestyle choices, which tend to be more sustainable too.

‘A lot of the chronic diseases that we see in general practice are exacerbated by things like air quality, poor diets low in plant matter, low levels of physical activity,’ he says. ‘I find people are generally receptive to things they could change to make their lives better.

‘An emphasis towards self-management, prevention, better disease control, as opposed to letting things get to a stage in which they need to become medicalised, can only reduce the GP workload and make our work more rewarding.’

Dr Gummaraju may sound ambitious but he has made a conscious choice to move away from ‘climate doom’ and reframe the debate around positive action.

‘There are things that we can all do, to start to enact bottom-up changes. As we start to make changes within our lifestyles and our professional lives, and influence the communities around us, that can trickle upwards towards wider action on a global scale.’

Speak truth to power

Of course, individual clinicians, even individual health organisations, are limited in their ability to effect and influence wider change. Switching to LED lightbulbs is one thing; retrofitting an ageing NHS estate is an entirely different proposition.

The solar farm powering Castle Hill Hospital near Hull was made possible by a £4.2m government grant through the Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme. Yet, over half (54 per cent) of the organisations that responded to the BMA’s recent emissions survey said they had not received funding for sustainability initiatives. On average, threequarters (75 per cent) of their energy usage still relied on fossil fuels.

‘Chronic diseases we see in general practice are exacerbated by things like air quality’Staff enjoy the ‘secret garden’, a restored Victorian walled garden at Glenfield Hospital in Leicester A nature recovery ranger creates a courtyard garden at Southmead Hospital, Bristol The Fern Garden beside the chemo suite, Mount Vernon Cancer Centre, London DORA DAMIAN / CSH PHOEBE WEBSTER / CSH VICKI BROWN / CSH

Furthermore, the NHS’s own carbon footprint – the emissions it controls directly – is only part of the picture. Reducing ‘the NHS carbon footprint plus’ – the emissions it can influence, such as its supply chain or patient/staff travel – is much more complex.

That’s why Bill Stableforth, a consultant gastroenterologist in Cornwall, stresses the need to join with like-minded others, to build momentum as well as for mutual encouragement.

A staff meeting in a lecture hall was the catalyst for Royal Cornwall Hospitals Trust declaring a climate emergency and later setting a net-zero target of 2030.

Climate action at trust level needs to go hand in hand with advocacy at national level, Dr Stableforth believes, and to be effective, advocacy needs to build movements for change.

‘The NHS is leading the world towards net-zero but it needs to happen rapidly. And the NHS is constrained in many ways, most importantly by everything being so busy: people can’t draw breath to think about this stuff,’ he says.

‘We need to put the onus to act on the Government and the fossil fuel industry. Telling individuals to go and buy a bamboo toothbrush is a deflection tactic: that’s not the answer. But when healthcare people speak up on these issues, people listen.

‘What’s not to like about cleaner air, safer streets, less noise, less pollution, being able to go and see your mates on your bike, your children playing in the street?’

Start somewhere

Like Dr Mortimer, Dr Gopfert believes that addressing climate change is critical to the future of health and healthcare, and she’s shifted her focus away from clinical work towards policy change.

‘For me, everything else is dwarfed by this

issue,’ says Dr Gopfert, who’s based in Devon. Encouraging others to understand and engage with it too has become an important part of her work.

The Faculty of Public Health’s Sustainable Development Special Interest Group, which she co-chairs, now offers ‘reverse mentoring’ where junior practitioners work with more senior members to communicate why action on climate change and health is so important to them and to ensure that they use their seniority to enact change.

She is working with UCLPartners, a health innovation partnership on a mission to solve the biggest health challenges through research and innovation. One focus of its climate work is considering the feasibility of trusts engaging in power purchase agreements (long-term energy contracts) that invest in renewables capacity.

But Dr Gopfert urges people to find their own role in this – whether that’s introducing change to their team, lobbying their institution or pushing for wider systemic change.

Like Dr Gummaraju, she encourages people to connect with others who can offer ideas and support, and to try different things, whether that’s giving a talk at a grand round or asking questions of employers. And she urges doctors to write to their MP, taking advantage of their status as ‘trusted messengers’.

‘Find the thing that you feel able to do, find good people to do it with, and then start tomorrow: don’t delay. We need people to try things and learn from them.

‘And don’t be thwarted by failure: it just provides lessons for the next time. And make sure it’s a little bit fun because that’s what keeps you going.’

‘Find the thing that you feel able to do, find good people to do it with, and then start tomorrow’

Undercut and undermined

Even after 33 years, Margaret Stark still loves the challenges and unpredictable nature of her work providing healthcare to those in police custody.

Serving as an FME (forensic medical examiner) for the Metropolitan Police, a typical day for Prof Stark might see her assess injuries and prescribe medication to a detainee, determine whether a suspect is fit to be interviewed by police and collect and document forensic samples as part of a criminal investigation.

Historically known as ‘police surgeons’, FMEs are today responsible not only for ensuring the health of those in police custody, but also for assessing and treating victims of crime in settings such as sexual-assault referral centres and providing expert testimony to courts.

Despite the demanding, complex and hugely important nature of an FME’s work, it is a role that often exists under the radar of the wider medical profession and one that, for a variety of reasons, faces an increasingly uncertain future.

‘Most people have no idea really about this area of practice,’ says Prof Stark.

In forensic medicine, doctors are being supplanted by cheaper and less-qualified alternatives. They warn of serious potential implications for patient safety. Tim Tonkin reports

‘I go in at half-past six in the morning and am embedded for 12 hours [so the work] is incredibly variable. It could be anything from prescribing two paracetamol for a detainee with a headache to taking forensic samples from rape suspects or drink drivers.

‘You also have to assess anybody who has a [long-term] medical condition such as asthma, diabetes or epilepsy and determine whether they’re fit to be detained. Then there are assessments for fitness to interview and determining whether the suspect knows what’s going on or whether they need an appropriate adult.’

Until 2003, healthcare and forensic medical services in police custody were provided solely by medical professionals working directly for a particular constabulary.

In that year, however, a change in the law allowed other healthcare professionals such as nurses and paramedics to undertake this work.

Limited service

Having spent decades providing medical services to police stations in London, recent changes in the way care is delivered has seen Prof Stark increasingly having to limit her clinical expertise to a phonebased advice service, with direct care instead being provided by a nurse-led service.

‘In 2021 the Met got rid of doctors because they wanted a nurse-led service, but they can’t at the moment run the service without the doctors because there are too many gaps,’ says Prof Stark.

‘I think there will be a huge push to get rid of us completely, and I suppose our concern is where else in medicine are

there no doctors?’

As with prison inmates and those detained in other secure environments, suspects in police custody should be afforded access to the same standard of healthcare they could expect to receive in the community.

Unlike prisons and immigration-removal centres, however, the provision of healthcare within police custody settings in England and Wales does not automatically fall to the NHS but is instead commissioned at the discretion of individual forces’ police and crime commissioners.

Although a small number of police forces continue to employ doctors directly, the majority commission healthcare services from private-sector firms.

These organisations tend to favour a model of service led by HCPs (healthcare professionals) such as nurses or paramedics, with some staff (including doctors) having limited experience of, and having received inappropriate training to prepare them for, working in police custody settings.

Under these HCP-led models, and without a national system for enforcing minimum standards in staff training and experience, there is concern as to what this might mean for the wellbeing of suspects and victims of crime and for the integrity of the justice system.

‘One of the most concerning things is we simply don’t know whether variability in healthcare, whether it be from doctors, nurses or paramedics, impacts on a broader clinical and criminal outcome,’ says consultant forensic physician Jason Payne-James.

‘If somebody, for example, documents an injury inadequately or takes a biological sample with poor technique or believes that somebody is fit to be interviewed when they’re not, it’s at that point where it is possible that miscarriages of justice may occur.

‘These miscarriages of justice could mean people who should have been convicted aren’t convicted because sampling or injury documentation has been inappropriate and conversely those who should not have been convicted are inappropriately convicted.’

Fragmented care

A specialist in forensic and legal medicine, Prof PayneJames is a renowned expert witness whose testimony is regularly sought by prosecution and defence counsel in criminal cases.

He last year co-authored a study into healthcare services in police custodial settings in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, which sought to

gather information on how police forces delivered their forensic healthcare services, the types of healthcare professionals used, and the minimum experience, training and qualifications required of these staff.

Based on the findings of this study, Prof PayneJames says care models in police custody are hugely fragmented, resulting in a clinical-care postcode lottery in which many services have seen doctors replaced by underqualified HCPs.

‘I’m not naive enough to think that the police aren’t under huge pressure in the same way as every other public body in terms of finance, [but] I am not aware of any other medical specialty where doctors have been removed because it improves care,’ says Prof Payne-James.

‘The problem I think that we have with having some services funded by commercial private providers is that, inevitably, the commercial providers are there as businesses to

generate income potential for shareholders.

‘It would seem sensible that every police service has exactly the same requirements in terms of minimum qualifications of the doctors, nurses and paramedics, which has been established, but it’s certainly not followed.’

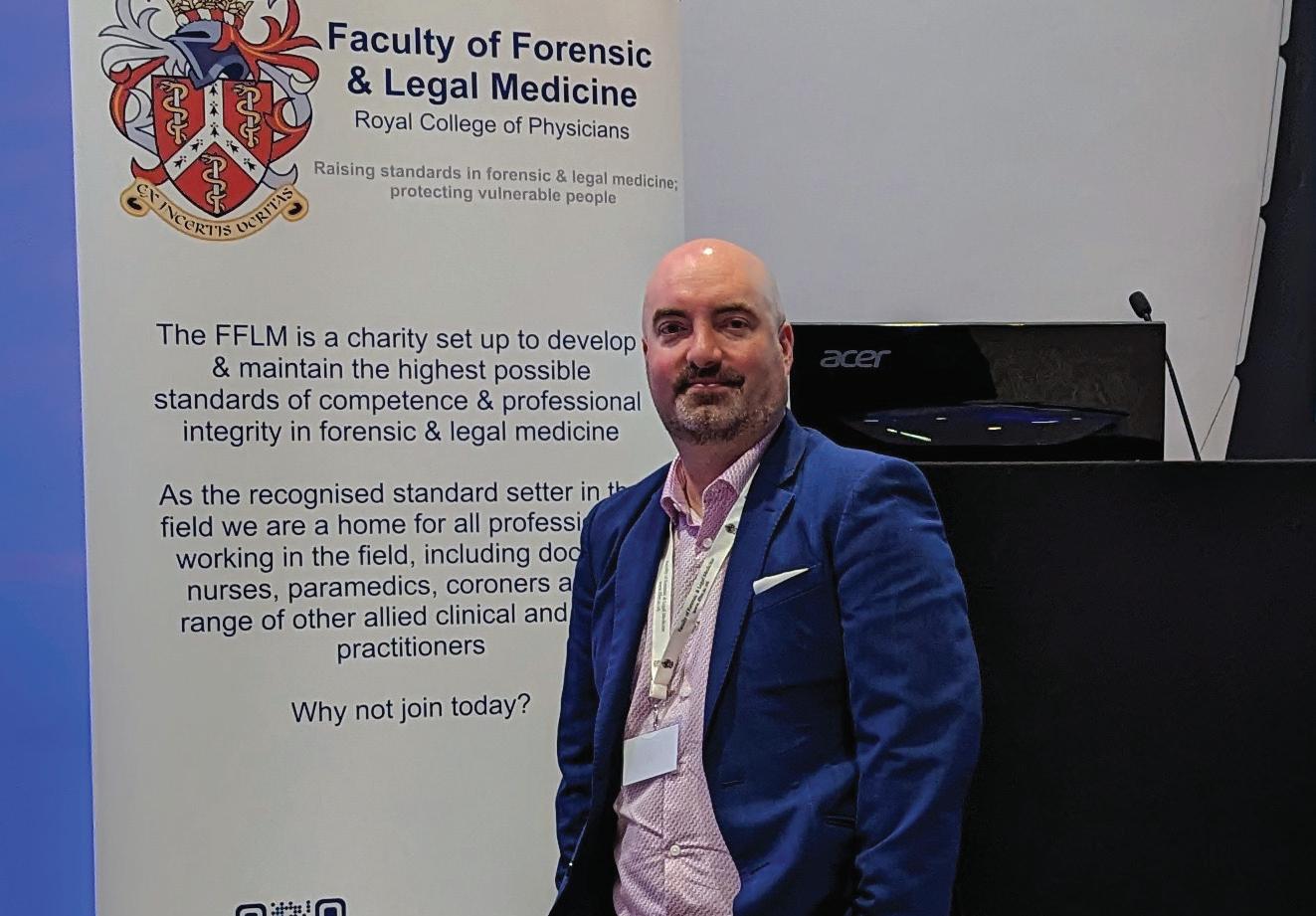

Quality standards concerning the level of training and experience of healthcare staff being employed to deliver custody healthcare do exist, having been developed by the Royal College of Physicians FFLM (Faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine).

Forensic physician Alex Gorton believes, however, that many police forces treat these standards as advisory guidelines rather than something that should be strictly adhered to when commissioning services.

As part of a 2022 paper Quality standards in forensic medicine , co-authored with Prof Stark, Dr Gorton argues: ‘Without a robust system enforcing agreed quality

‘It is possible that miscarriages of justice may occur’

‘I am not aware of any other medical specialty where doctors have been removed because it improves care’

standards there is little incentive for such standards to be followed.

‘We know every healthcare model works better when you do have a true multidisciplinary team but, in reality, what we’re seeing on the ground is that we have leapfrogged multidisciplinary to be nurse or paramedic-only,’ he says.

‘These are advancedpractice roles, effectively diagnosing, treating and discharging independently, therefore if we are expecting nurses and paramedics to undertake them without any medical support we should be deploying [advanced clinical practitioners] or equivalents (these would normally attract band 7 or band 8 scales in the NHS). We don’t see these qualifications widely in custody as they are too expensive for the procurement envelopes so they aren’t being trained to that level.’

Dr Gorton says one notable effect of having less experienced or inadequately trained staff working in custody settings is the increased likelihood for detainees with health complaints to be referred to hospital, thus placing strain on the police and the NHS.

‘One of the mantras in custody is “if in doubt, send them out” because obviously you don’t want a death in custody,’ Dr Gorton explains.

‘If you have more risk-averse clinicians, perhaps because they’re less well trained, they’re going to send more people to hospital. Every time you send a detainee from police custody to hospital, you’re sending two police officers with them.

‘With a modern emergency department wait, you’re looking at probably eight to 10 hours,

so that’s two officers eight to 10 hours off the street, with a detainee and on top of that, the NHS is then providing that healthcare input.’

NHS transfer delay

Responsibility for the commissioning of police custody healthcare services in England and Wales had been set to transfer to the NHS, but the process was halted in 2016 by the then home secretary Theresa May.

This decision remains in effect despite the findings of a 2017 independent review into deaths and serious incidents in police custody, which stated that placing healthcare under the remit of the NHS would enable ‘a consistency of approach’ and ‘provide for minimum standards for medical staff within the police station’.

Scotland is the only part of the UK in which police custody healthcare comes under the auspices of the NHS.

‘I’m not sure if it’s already too late. To be brutally honest although I love this work it

seems to be a dying specialty with no space for doctors who want to keep doing it,’ laments Dr Gorton.

‘Police procurement seems focused on “bums on seats” filling rotas rather than recognising the need for specialist skills. This means there is little incentive for profit-focused providers to up their game. Politically it can be hard to argue for quality care of suspected perpetrators of offences, but, even if one takes that heartless view, high-quality assessment and support of alleged offenders increases quality of evidence and thus supports victims of crime’

The issue of delivering effective healthcare in custody settings is set to be an area of focus of a one-day conference being staged by the BMA’s forensic and secure environments committee on 17 July.

For more information about the event and how to register, visit bma.org. uk/events/forensic-andprison-doctors-conference

bma.org.uk/thedoctor

‘If you have more riskaverse clinicians, perhaps because they’re less well trained, they’re going to send more people to hospital’

‘Although I love this work it seems to be a dying specialty’GORTON: Some police forces not meeting quality standards

BURSTING AT THE SEAMS

GPs are being forced to work in cramped premises which hold them back from recruiting staff and meeting patient needs.

Ben Ireland visits three practices which highlight the need for urgent investment

Kensington Road Surgery has outgrown its longstanding home in a Victorian end-terrace house in Coventry.

On the day The Doctor visits, one nurse had been turfed out of her room twice before midday.

‘It not only puts me behind,’ she says. ‘I had to kick one of the doctors out of his room. It was like we were playing musical chairs. We’re very productive, but we could be even more productive if we weren’t faced with this.’

Huma Latif, a GP partner at Kensington Road, says the pressures to keep up with everrising patient demand have taken their toll on the practice’s workforce who she feels deserve to work from a site with sufficient space to do their jobs.

The practice has been innovative with its space but is bursting at the seams. The back of the reception area also serves as a staff kitchen, with a fridge a makeshift table. There is no room to add a lift, so patients in wheelchairs must be seen in ground-floor consulting rooms. The medical secretary works among boxes of gloves and toilet rolls. The only staff room is in the loft with a slanted roof, so anyone over 5ft 4ins can’t stand upright.

Staff take the brunt of the inconvenience so patients don’t have to, but some effects are unavoidable. The midwife has been forced upstairs and on-street parking is not readily available given competition from customers of the nextdoor tyre shop.

Foundation of care

‘Patients have come to expect an excellent service,

which we provide,’ says Dr Latif, who joined Kensington Road as a partner in February 2022. ‘I want to ensure we continue to give that, but it’s not sustainable in the current building.’

She adds: ‘We pride ourselves on giving really personal care. That was honed by the partners before me. I saw how hard everyone works, the potential in the practice and how we can build on that – a big part of that is the building.’

Partners welcome the relatively recent development of ‘additional roles’ staff, but Dr Latif says they are ‘constantly playing merry-goround’ for space to work from. As well as three first-contact practitioners and a clinical pharmacist on-site, there is a visiting paramedic, an occupational therapist who mainly does home visits and social prescribers reluctantly based off-site.

With space at such a premium, ‘if an emergency comes up, and we need to do an ECG, we might have to kick someone out of one of the downstairs rooms which immediately puts us behind,’ Dr Latif adds.

‘There’s a knock-on effect to the whole practice; receptionists do an amazing job but if things change or get held up it upsets patients in the waiting room, which can be heard in the consulting rooms.’

Recruitment and retention is ‘an issue’, Dr Latif notes.

‘We need more staff, but there is nowhere for them to work. When locums come in, I ask them what might make them consider a salaried role. The premises always comes up. It’s a major barrier to recruitment. If we had the

building, the rooms, we could recruit. It would be so much more appealing. We could take on trainee GPs, or a junior pharmacist, but our existing pharmacist doesn’t even have the room they need.’

Kensington Road’s list has grown by about 2,000 patients over the last 20 years, peaking at nearly 7,000 pre-COVID. But because of how tight services are, this has dropped slightly to about 6,500. Dr Latif says: ‘Patients were getting frustrated they couldn’t get appointments – which comes down to the lack of space.’

‘We can make it sustainable and continue to give that level of care if we have some support for that investment,’ she insists. ‘We need a new practice that’s purpose-built.’

Dr Latif went to the Best Practice exhibition in Birmingham and spoke to banks and architects about possibilities. It gave her plenty of ideas, but a funding ‘minefield’ remains an obstacle.

When NHS improvement grants are offered, a practice’s notional rent will be subject to an abatement depending on how much is funded. So the practice pays long-term. The only other option without involving a third party is

‘If we had the building, the rooms, we could recruit. It would be so much more appealing’TIGHT SPOT: Staff at Stoke Aldermoor practice work from the surgery’s break room

self-funding, which usually involves bank loans given the costs involved.

Dr Latif says: ‘There needs to be some clearly earmarked money to support investment in GP premises which is easily signposted so we know where we stand.’

In Dr Latif’s experience, ‘banks seem more amenable to the idea of two practices merging under one roof. But that could get messy, and lead to disagreements. Plus, I believe in old-school general practice. Our patients love that we’re a family practice they can walk to.

‘It can be quite demoralising as a new partner. When you come up against such brick walls it makes you question your attempts to improve the practice and quashes aspirations.’

Daily struggle

Kensington Road is not the only practice in Coventry desperate for investment.

Stoke Aldermoor Medical Centre was purpose-built in

1992, when it had a list size of 500 patients, and extended in 2006. Its three GPs now care for about 6,600 patients.

Partner Parveen Aggarwal says: ‘We’re bursting at the seams. It’s so busy we have people doing admin work on laptops in the kitchen around others who are trying to take a break.

‘Some staff use the practice manager’s office. Staff are essentially hotdesking, but in practice leaving your room to write up your notes somewhere else doesn’t work. And you might need to make confidential phone calls. We’ve run out of shortcuts.’

There are six consulting rooms at Stoke Aldermoor, not enough for the doctors, nurses, pharmacist, physiotherapist and physician associates. Dr Aggarwal is keen to become a training practice but feels that is impossible given the daily battle for rooms. ‘There isn’t enough space,’ he tells The Doctor

Dr Aggarwal paid architects to draw up plans back in 2019, sought council planning

approval and developed a business model.

But improvement grant funding has still not been forthcoming. As a last resort, he has considered splitting one consulting room in two, turning the rest area into another and moving that into the loft – giving eight consulting rooms.

He fears going ahead with such temporary measures could make it harder to claim funding long-term.

Such funding was available back in the late 1980s, when Dr Aggarwal received a loan of more than £80,000 as a new GP partner. ‘I was very grateful for that support,’ he recalls. ‘I have so much more expertise behind me now, I know we can provide a good service for today’s challenges with the right support.’

His oven-ready expansion plans – which he sees as the ‘bare minimum’ – would cost £250,000, and Dr Aggarwal is not even asking for all of that, just a contribution. If it came to fruition, he could accommodate two GP trainees and two medical students and allow ARRS (additional roles reimbursement scheme) staff their own rooms.

‘If we compare it to PFI funding, it’s much better value,’ he adds. ‘It’s not a lot to ask. In an ideal world we would have a much bigger expansion so the practice could cope as its list size grows.

‘This is the only GP practice serving a growing population in a deprived area. We have 15-20 patients applying to register every day. I’m going to have to stop taking new patients if I

‘We can provide a good service for today’s challenges with the right support’LATIF: Barriers to expanding practices

can be demoralisingCRAMPED: Space is at a premium at the Kensington Road surgery in Coventry

can’t get access to funding. If we want to offer a good service, even a basic service, we need space.’

Provision potential

One Coventry practice where staff feel happy is Broomfield Park, which was the beneficiary last time any practice in Coventry and Warwickshire LMC received estates funding – back in 2016.

The £2m project, completed in 2019, enabled it to grow its list size, including a satellite site at the University of Warwick, from 14,000 in 2016 to 20,500 in 2020.

Broomfield Park houses four partners, five salaried GPs, three to four GP trainees and 12 ARRS staff in a combination of full- and part-time roles. Its modern, airy building has spacious consulting rooms and good accessibility.

Walls in the waiting areas are decorated with intentionally calming floral wallpaper and there are designated admin and meeting rooms.

Monica Green, a partner since 2002, says the results show what can be achieved when GPs are given financial support for their premises.

‘Thankfully, we have room for everyone currently. But we are running out of space. We probably went for more rooms than we needed at the time but wanted to futureproof the practice.’

Need for investment

Doctors at the BMA’s 2022 ARM called for ‘HS2-type investment’ in GP estates as 91 per cent backed a motion calling for extra funding and to look at the limits to disabilityadapted consultation rooms. A rider to the motion, backed

by 95 per cent, called for more space for GP trainees.

A BMA report published in December 2022 laid bare the ‘alarming’ condition of healthcare estates and recommended ‘substantial’ capital investment is made available to GP practices and hospitals.

It found 26 per cent of respondents to its survey working in primary care said the building in which they work is in a poor or very poor state and concluded: ‘Shortage of space is a major challenge in general practice, making it harder for GPs to see patients quickly and even preventing some practices from expanding their patient list.’

In 2018, only half of the 1,000 GPs responding to a BMA survey said their practice was fit for present needs – and two in 10 said their practice was fit for future needs.

The NHS Confederation made investment in estates one of the 10 priorities of its Delivery Plan for Recovering

Access to Primary Care, published in March.

Peter Holden, who sits on the BMA GPs committee, and gave evidence about the state of GP estates to the Commons health select committee last year, says: ‘The Government wants us to do more in general practice, the Government wants more GPs, and the Government has provided more people through the ARRS scheme –but they need somewhere to work from, and our buildings are bulging at the seams. One of the reasons patients can’t see a doctor is that there’s nowhere for us to consult from.’

Dr Latif at Kensington Road sees the difference funding could make to her practice and believes the state of general practice sets the tone for patients’ experiences of healthcare.

As she puts it: ‘Politicians talk about general practice as the “front door” to medicine. But if your front door is in tatters, what do you expect for the rest of the service?’

‘If we want to offer a good service, even a basic service, we need space’

At a time of endemic discrimination, Cecil Belfield Clarke was a black, gay doctor who thrived in mid-century Britain. His civil rights legacy is now being celebrated, as Tim Tonkin reports

A forgotten hero

For doctors and other healthcare professionals, ‘Clark’s Rule’ is a well-established aspect of paediatric medicine.

A simple mathematical formula based on body mass, it is still used throughout the world as a means of determining the safe dosage of medication to give to a child patient from the equivalent amount that would be given to an adult.

The fact, however, that this rule is commonly misspelled perhaps gives some indication as to how little-known the trailblazing doctor responsible for it remains.

Dr Cecil Belfield Clarke was a truly remarkable figure in UK medicine during the first half of the 20th century, and a man whose legacy continues to be felt to this day even if it is one that is not immediately recognisable.

Dr Clarke was not only one of this country’s first black doctors, but a passionate civil rights activist at a time when the so-called colour bar, an informal yet pervasive system of racial discrimination, enabled black and minority ethnic people in the UK to be treated as second-class citizens.

Born in Barbados in 1894, Dr Clarke was a pupil at the island nation’s Combermere School where he succeeded in obtaining a scholarship in natural science which secured him a place to study medicine at St Catharine’s College, Cambridge.

Departing from his home in the summer of 1914, the then 20-year-old student made what was to become an increasingly perilous journey across the Atlantic, landing in England just weeks following the outbreak of the First World War.

Campaigner

After completing his medical training at Cambridge and at University College Hospital, London, Dr Clarke opened his own medical practice in Elephant and Castle, south London, which he subsequently ran for almost 50 years.

Despite his commitments to the patients of his south London community and to supporting the developing medical professions in the West Indies and Ghana, Dr Clarke was also a committed pan-Africanist and a prominent advocate for the UK civil rights movement.

Together with Jamaica-born physician Harold Moody, the two doctors founded the League of Coloured Peoples in 1931, with Dr Clarke cultivating international links with other black civil rights activists, while also investing much of his personal income as a doctor towards funding the league’s campaigns.

Dr Clarke continued to serve his community as a doctor throughout the Second World War, despite the enormous physical devastation and loss of life wrought on the capital during the Blitz of 1940-41.

WARNER: Dr Clarke’s legacy deserves recognition

Having fought to study and practise medicine as a black man in the 20th century, as well as being a vocal proponent in the movement for racial equality, Dr Clarke was clearly a person of immense courage and fortitude.

This aspect of his character was perhaps further evidenced through his personal life, with Dr Clarke now known to have been a gay man living with his long-term partner Edward Walter, at a time when homosexuality was a criminal offence punishable by imprisonment.

Dr Clarke maintained a life-long affection for Cambridge, and in 1952 his former college established the Belfield Clarke prize for outstanding performance in biological natural sciences Tripos examinations.

Memorial effort

It was also in the 1950s that Dr Clarke became one of the first black doctors elected to the council of the BMA where he served as representative for the West Indies, and was appointed a medical adviser and later a senior medical officer to Ghana following the country gaining its independence from the UK in 1957.

Fortunately, efforts to raise awareness and to celebrate Dr Clarke, who died in 1970, have recently taken a step forward following the unveiling last month of a historical London blue plaque at the former site of Dr Clarke’s London practice.

Despite St Catharine’s College continuing to award a prize bearing Dr Clarke’s name, many people still knew little about the man behind the prize.

Following a research project in 2019, Cambridge graduate L’myah Sherae uncovered details about Dr Clarke’s life which helped to draw greater awareness of his legacy.

Tony Warner is the founder of Black History Walks, an organisation dedicated to promoting and preserving the history of black people in the capital, and the person chiefly responsible for commissioning Dr Clarke’s memorial plaque.

Having already successfully campaigned to get a plaque erected in honour of Dr Moody, Mr Warner says he felt Dr Clarke’s legacy was as important and

deserving of recognition.

‘His name is not as well-known as it should be yet his contribution to medicine and civil rights is incredibly immense,’ says Mr Warner.

‘Not just by the example of him being a doctor, but by him fighting to get equality when it came to black health professionals [and the colour bar].

‘He was able to break through that by virtue of him being a black doctor, but also by virtue of him investing his money into campaigns, protests and letter-writing.’

BMA representative body chair Latifa Patel, who was among those who attended last month’s unveiling, says Dr Clarke was a man who should never be forgotten in our society.

‘Throughout our history, many ethnic minorities have made significant contributions, but their achievements have often been overlooked or forgotten due to systemic racism and discrimination,’ says Dr Patel.

‘As a junior doctor with my specialty in paediatrics, the contribution by Dr Clarke in the form of the Clarke’s Rule resonates deeply with me.

‘The medical profession has always been ethnically diverse, and international medical graduates and doctors from ethnic minority backgrounds have been and continue to be the backbone and the bedrock of the NHS.

‘Dr Clarke, a black doctor from Barbados, is today a pillar of our medical story.’

‘His contribution to medicine and civil rights is incredibly immense’

‘Fighting to get equality when it came to black health professionals’PATRICK LEWIS/PAL ASSOCIATES

Reaching out

Outside a church congregation, on a construction site, in the car park of Croydon IKEA – they’re not locations you would typically associate with delivering healthcare.

Yet that’s exactly where patients have found a mobile outreach clinic aiming to speed up prostate cancer diagnosis and provide better outcomes for Black men, who are twice as likely as others to get prostate cancer, which leads to more than 12,000 deaths a year in the UK.

The Man Van, an initiative developed by The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, The Institute of Cancer Research, and RM Partners West London Cancer Alliance, is in the second stage of a pilot – funded by NHS England – testing as many south London men over the age of 45 as possible.

Doctors behind the initiative hope it can become a cost-effective model for early intervention and targeted care, not only in the most common male cancer – but to help detect cardiovascular and psychological risks or signs of diabetes and liver disease.

The van has also been parked at a community

centre in Sutton, outside Croydon University Hospital, near a recycling centre and by GP practices. Locations being considered include a football stadium and shopping centres.

Nick James, a professor of prostate and bladder cancer research at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and consultant clinical oncologist at The Royal Marsden, came up with the concept before COVID, when he was working in Birmingham.

He says the initial idea was to go to people’s places of work but found ‘the demographics weren’t right’ because ‘people don’t necessarily live where they work’.

The 20-minute appointments are booked in advance through GP practices, which send texts to targeted patients on behalf of the mobile clinic.

‘If you can get to people, it’s easier for them to access your service,’ says Masood Moghul a clinical research fellow funded by The Royal Marsden Cancer Charity which runs the service.

‘It has been a bit of trial and error. Ideally, we want places with good access, and parking. We do a lot of

A group of medical organisations have decided to hit the road to improve rates of prostate cancer diagnoses. Ben Ireland reports

‘Lots of organisations are raising awareness, this is about increasing access’ROYAL MARSDEN NHS FOUNDATION TRUST

groundwork to find locations. Lots of organisations are raising awareness, this is about increasing access.’

Good feedback

A walk-in service was considered but ‘doesn’t quite work’, says Dr Moghul. ‘It’s not like a blood pressure or diabetic check. Because we’re dealing with potential cancers, you need a bit of privacy.’

‘We are managing to get people through the door who normally don’t engage in healthcare services’

staggering’. Pilot results show 28 per cent of those tested have hypertension, 5.4 per cent have diabetes and a further 15.6 per cent have pre-diabetes states. The pilot has also started looking at liver function and using mental health questionnaires. At the end of the pilot, results from embedded studies looking at health economics, genetics and why people chose to turn up will be collated.

Results of PSA (Prostate-Specific Antigen) tests are typically given two to three days after an appointment, usually over the phone. Referrals are often made to The Royal Marsden, and can be with the same team who work at the van, offering patients continuity. Polygenic risk scores telling patients their likelihood of getting prostate cancer in the future can also be offered.

It is hoped the Man Van may take some pressure off general practice. Prof James says the current route to getting a PSA test involves ‘three or four visits’, noting: ‘If you’re on a zero-hours contract, taking time off to go to the doctors means you’re leaving behind money.’

Dr Moghul agrees men ‘have to be quite committed’ to get a PSA test via a GP appointment, cooling-off period and returning for blood tests. By contrast, patients ‘have control’ of when and where they visit the Man Van.

‘Feedback from GPs [in the pilot area] has been really positive,’ he says. ’We see ourselves as a helping hand. We’re finding problems that are already there, not creating problems.’

The service, continually evolving in its pilot, looks for red flags such as weight loss or lumps and feeds those back to GPs – which can help lead to earlier interventions and better outcomes.

Dr Moghul explains: ‘You’re putting in the same amount of effort to find people, so it’s about how much time they’re spending with you. If they’re spending five to ten minutes doing urological tests, adding another five to ten minutes doesn’t add much in terms of cost – but could potentially add a lot in terms of value.’

Prof James notes ‘the pick-up rates are

‘We’re very interested in how cost-effective it is if you test for other things as well,’ says Prof James. ‘We’ll be seeing whether knowledge of your future, knowing of conditions you haven’t got yet but are at high risk of getting, modifies people’s behaviour. The question is “if you are obese but not diabetic, and told you’ve got a 90 per cent chance of developing diabetes in the next 10 years, do you go on a diet or not?”. We are going to get all sorts of interesting data back.’

Targeted testing

A big part of the pilot is using its results to improve prostate cancer outcomes for ethnic minority men. Pilot results include data from a high proportion of groups that are often underrepresented in clinical trials. For instance, 29 per cent of the men are Black/Black British, higher than the 15 per cent Black ethnicity in Croydon. A further 13 percent of the men are Asian/Asian British.

‘Different diseases behave differently in different ethnicities,’ explains Dr Moghul. ‘We know so much more about European genetics than any other ethnicity. With prostate cancer that can be a problem because it affects Black men more.’

The Man Van uses targeted testing, not screening, which the doctors note is not recommended in NICE guidelines for prostate cancer but is used to help detect breast, cervical and bowel cancer.

The data it is collating may, however, be used in future assessments of screening for prostate cancer – which the EU began recommending in 2022.

Prof James believes screening is ‘only partly an answer’ for increasing diagnosis rates for serious diseases, but one worth exploring alongside targeted testing.

‘If you look at screening programmes, 50 per cent don’t turn up,’ he says. ‘We are managing to get people through the door who normally don’t engage in healthcare services.’

The Man Van is now seeing about 100 patients a week and expects to see 3-4,000 men this year.

‘We want to prove the concept, show it works and that it’s cost-effective,’ says Dr Moghul. It would be great if this could continue and expand, helping to target those high-risk groups that always seem to slip through the cracks.’

Your BMA

One of the BMA’s biggest ambitions is our pledge to end sexism, and all forms of discrimination, in medicine.

I think we can quickly make sexism, and other forms of discrimination in medicine, horrors of the past.

On 27 April we met with 48 representatives from 40 organisations from across the health and care landscape in a bid to discuss best practice, share our learning and challenge colleagues and partners to do much better on tackling sexism and discrimination in medicine.

These organisations have all signed up to the BMA’s pledge to end sexism in medicine – a pledge which recognises the barriers medical students and doctors face around gender-based discrimination.

The pledge follows a sexism in medicine report the BMA produced in 2021 after working with Chelcie Jewitt, co-founder of the Surviving in Scrubs campaign, who had gathered an array of testimony of sexist behaviour from women doctors across the NHS. The subsequent survey found that a shocking 91 per cent of women doctor respondents in the UK had experienced sexism at work with 42 per cent feeling they could not report it.

What we found in that room was a group of people, and a collection of organisations, who agreed that we needed change and were prepared to advocate for their members and support us in our mission.

One of the ideas we discussed, and a suggestion the BMA will look to take forward with partner organisations as quickly as possible, is that we look to link sexism in medicine to ARCP (Annual Review of Competency Progression) and to revalidation. ARCP takes place every year if you are a junior doctor and revalidation is every five years depending on when you graduated and if you are a GP or a specialty doctor. If it was linked – if every

@drlatifapateltime you ARCP or went through revalidation there was a list of complaints against you – that would make change happen. I see two fantastic benefits to a process like this. Not only would we quickly make sexists and misogynists accountable for their behaviour, but we would empower those people who are victims to come forward and speak up – rather than feeling, as so often is the case in the NHS, that they are unheard and uncared for.

It is vitally important we take action in this area. Sexism in medicine is a malign influence and, as Roshana Mehdian-Staffell and other female surgeons recently told The Times , is something many of us have experienced. Those brave doctors described a ‘boys club’ mentality and detailed the misogyny, discrimination and sexual harassment they had experienced during their training and careers.

If you’re involved in one of the organisations who have signed up to our pledge, how are you going to drive change? Will you take the pledge and hold others to account? And if not, why not? What’s stopping you?

To anyone not in positions of power in these organisations, if you are facing sexism please use this pledge. Together, we can eradicate sexism in medicine – and your BMA won’t stop fighting until we do.

Please get in touch and tell me how we can do more – or how we can help you. You can contact me directly via Twitter or email me at rbchair@bma.org.uk

Dr Latifa Patel is chair of the BMA representative body

Editor: Neil Hallows (020) 7383 6321

Chief sub-editor: Chris Patterson

Senior staff writer: Peter Blackburn (020) 7874 7398

Staff writers: Tim Tonkin (020) 7383 6753 and Ben Ireland (020) 7383 6066

Scotland correspondent: Jennifer Trueland

Feature writer: Seren Boyd

Senior production editor: Lisa Bott-Hansson

Design: BMA creative services

Cover photograph: Ed Moss

Read more from The Doctor online at bma.org.uk/thedoctor

Banishing sexism from medicine may happen sooner if we adopt a radical, novel approach