the doctor

The magazine for BMA members

A tale of one city Our special investigation into austerity and health

A tale of one city Our special investigation into austerity and health

Give us a break The unsustainable pressure on junior doctors

Led all that way... For birth or death? A story of hope from a freezing night

The light still burns The unbreakable spirit of Ukrainian doctors as they face a hard Christmas 14-15 Every opportunity Helping international medical graduates get experience on the wards 16-20

Underpaid, underappreciated and under pressure

The pressures on junior doctors that are forcing them to consider industrial action

Phil Banfield, BMA council chair

This is the last edition of The Doctor of 2022 and I would like to take this opportunity to wish you a peaceful festive season – and a very happy new year.

This Christmas should have been a celebration of the return to ‘normality’; for all too many it will be anything but. As we keep our colleagues, peers, and all the people in conflict zones across our planet in our thoughts, we hear from doctors working in Ukraine about their expectations of a ‘hard and uncertain’ winter, how they are adapting to life during war, and their gratitude for the solidarity and support shown to them by countries around the world. They also tell us what Christmas might look like where they live and work.

In the December issue of the magazine we feature the first of a two-part investigation into the relationship between austerity and health – as told through the stories of people in one city: Nottingham. This is the most in-depth work we have ever published, the result of months spent meeting and interviewing doctors, patients, community groups, service users, charities, council staff, volunteers and politicians in Nottingham.

It happened to me A doctor has nothing left but his hope and prayers when on a home visit

Your BMA

Why doctors are saying enough is enough 23

On the ground An infl exible royal college tells a doctor to start her training afresh

The stories are difficult to read and are particularly harrowing in the context of a growing cost-of-living crisis. This investigation is one of the flagship pieces in the BMA campaign around health inequalities and austerity and will help us to lobby the Government for urgent action to halt the decline in the country’s health. It reminds us we are talking about people not statistics. We also investigate an initiative to support patients who are homeless, or at risk of homelessness, which is showing remarkable levels of success in Scotland.

We speak to three junior doctors about life on the front line ahead of the upcoming ballot on industrial action and find out about the medical support worker programme, which aims to give international medical graduates supported roles while they complete assessments. It is about valuing their essential skills and expertise, but also caring enough to support and understand their challenges and experiences. If those in power put themselves in the shoes of those without, we would be in a better place – one that values people before profit.

Keep in touch with the BMA online at instagram.com/thebma twitter.com/TheBMA

The BMA has produced two reports highlighting ‘inadequate’ IT provision and ‘appalling’ healthcare estates and is calling for protected and increased funding for upgrades and maintenance.

More than 13.5 million hours of doctors’ time is lost each year in England alone owing to delays resulting from IT systems and equipment – the equivalent of almost 8,000 full-time doctors, or nearly £1bn, according to Getting IT Right: A Prescription for Safe, Modern Healthcare.

The report looks at why four in five primary-care doctors report regular delays in accessing data from secondary care, and 57 per cent of secondary-care doctors report delays in the other direction.

It also looks at hardware provision, with just 11 per cent of doctors reporting ‘completely’ having the necessary equipment to perform their roles and 47 per cent saying they have it ‘only sometimes, rarely or not at all’.

Soft ware issues are also raised in the report, with 30 per cent saying soft ware is ‘rarely adequate’ or ‘not adequate at all’ while less than 4 per cent say it is ‘completely adequate’.

The IT report recommends ‘now is the time to invest’ in digital transformation, with 80 per cent of responding doctors saying improving IT infrastructure and digital technology would have a positive effect on tackling backlogs.

The BMA report urges Government to protect IT spending from budget cuts and increase funding for improvements in the long term.

The estates report, released simultaneously, found 83 per cent of responding doctors believe the condition of NHS estates limits their ability to use modern equipment and technology.

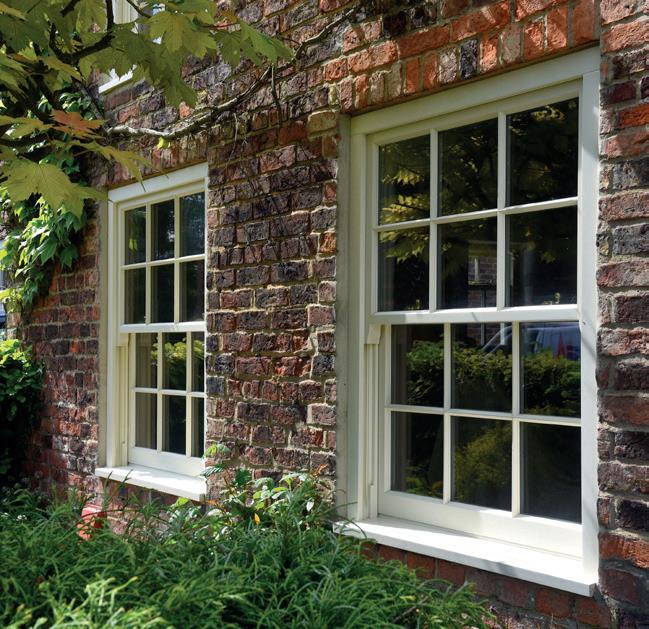

Brick by brick: The Case for Urgent Investment in Safe, Modern, and Sustainable Healthcare Estates reveals an ‘alarming’ 38 per cent of doctors consider the physical condition of their workplaces to be poor or very poor, and 43 per cent believe workplace conditions have a negative effect on patient care.

‘Crumbling’ buildings and infrastructure often force wards to close, it found, ‘compounding a wider lack of space’ and ‘contributing to ever-expanding waiting lists’ while insufficient space at hospitals and GP practices is hindering doctors’ training and preventing recruitment of additional staff.

Sewage leaks, burst pipes, leaking roofs, and mites in neonatal units were among the issues reported.

Doctors also raised concerns ventilation would be inappropriate for reducing infection in a future wave of COVID or another pandemic and that they were too often left out of the planning of estates projects.

Recommendations in the report include a national review of estates across the UK, dedicated funding for improvements and retrofitting, and urgently clearing existing maintenance backlogs and making sites accessible for all. ‘Substantial’ capital investment will be needed, it says.

Read the reports in full at bma.org.uk/news

BREMNER: Root causes must be tackled

Garry Lovelock is not a religious man. Yet, when the lonely nights sleeping on the streets, the ‘grubby’ washing in a McDonald’s toilets and the endless fines for boarding trains without a ticket become too much, he finds himself in church, praying – just hoping for ‘a helping hand’.

The other likely destination on those hopeless nights is the emergency department at Nottingham’s Queen’s Medical Centre. Mr Lovelock, 41, lost his house and employment after his wife died of leukaemia. When he is emotional and upset, he drinks. It is the causal spark of a repetitive cycle in which he is picked up by the police, taken to an emergency department, sees a doctor after sobering up and is told he is fit to go. Not go home, of course. But go. It is a costly cycle with the average interaction with emergency departments estimated at £297 by the NHS, not to mention the serious mental and physical toll this repetition has on Mr Lovelock, too.

‘There is so much of that – not addressing the root causes and just using sticking plasters [like seeing a doctor in emergency departments],’ says Ann Bremner, who runs The Friary homelessness charity in West Bridgford, Nottingham –where Mr Lovelock has been provided a meal and support with his search for employment.

The cycle between the streets and hospital is far from the only one in which the vulnerable are trapped. Others – each as dehumanising as the last – exist, too. Here at The Friary, there are scores of people who are regulars in other health services or the criminal justice system, for example. A Polish man being given a food parcel is one of those. He says he ‘lost everything’ because he was convicted of a crime and sent to prison for two weeks. He is now unemployed, and his only routines are going to places such as this for food and the regular check-ins with his probation officer.

‘I came straight from jail to the street,’ the man, who asks

to be called Grzegorz, says. ‘I have no home, no work and no money.

‘What do they expect me to do? A Universal Credit application takes at least a month and that means no money for five weeks and I have to start again every time [he is arrested].’ A friend, also at The Friary – who asks to be called Pavel – has epilepsy, which is difficult to manage while in and out of hostels or sleeping rough. Stephen Willott, a GP who does sessions with users of The Friary, manages his condition and is a ‘nice guy who does everything for me’ but it is clear Pavel needs significant support.

The Doctor has spent months in communities in Nottingham – meeting health professionals and their patients, people struggling to get by and the charities and organisations trying to hold together what remains of the UK’s disintegrating social-safety net. Everywhere the stories have similar themes – services have

The cost-of-living crisis is spiralling, and Government ministers propose further spending cuts and pay restraint in a country which has already suffered more than a decade of austerity. In the first part of a special investigation, Peter Blackburn examines the effects of slashed services and economic misery on the health of communities in NottinghamLOVELOCK: In search of a ‘helping hand’

‘I have no home, no work and no money’SHAWN RYAN

‘There’s so much demand. We won’t be able to help everyone and it is getting worse. It’s so worrying’

been pared back to the bone and society is often unable or unwilling to intervene.

The tales of tragedy are everywhere you look. When The Doctor visits The Friary there is a man slumped outside the front doors – knocked out owing to heavy use of the synthetic cannabinoid mamba, also known as spice. He has been in and out of emergency departments, crisis teams have been involved but because he has no home the authorities say there is no safe place for them to conduct a mentalhealth assessment. Instead, he is repeatedly charged with offences, offered no intervention, and continues to use vast amounts of drugs.

‘It’s incredible what he puts his body through,’ Ms Bremner reflects. And Dr Willott adds: ‘This is definitely an austerity issue.’

All of the horrors seen here in this one moment on one day in Nottingham are stark reminders of the deterioration of health in this country. Before the pandemic, life expectancy rates – an indicator of the nation’s health – had started to stall for the first time in a century. For some of the most deprived areas, such as many parts of Nottingham,

life expectancy was starting to decline – something not witnessed for 120 years. And the amount of time people spend in poor health has increased, with the gap in healthy life expectancy between the most- and leastdeprived areas now nearly 20 years.

The picture is particularly bleak here in Nottingham.

The ONS (Office for National Statistics) recently published a new health index, which scores the health of each part of the country based on a vast analysis of prevalence of conditions, access to services and living conditions. Nottingham is sixth worst out of 340. Much of the regression nationally, and locally, is being caused by preventable illness. Relative to comparable countries, the UK has a higher amount of preventable illness, and those numbers are rising.

An estimated 29 million people in the UK are living with one or more long-term health conditions. The number of working-age people in Britain reporting multiple serious health conditions has rocketed by 735,000 in just two years.

These figures are often worst in the most deprived communities. The evidence

suggests this deterioration in health is driven by austerity politics – political and economic decisions taken by successive governments. Billions of pounds have been cut from public services and social security since 2010, decimating welfare and the social safety net and there are now far fewer services promoting good health.

People are dying younger as a result, with the poorest areas hit the hardest. According to the Glasgow Centre for Population Health an additional 335,000 deaths have been caused by austerity in the five years before the pandemic –more than from the first two and a half years of COVID-19.

Cuts to central government funding for local government have meant cuts to public services that are essential to health – including housing, transport, children’s services, leisure and public health.

For example, spending on housing services and homelessness prevention declined by 50 per cent between 2009 and 2019. Street homelessness rose rapidly during this time, doubling between 2013 and 2018. The

GREGORY: ‘You don’t know how desperate you could easily be’

The ONS recently published a new health index, which scores the health of each part of the country based on analysis of prevalence of conditions, access to services and living standards

NOTTINGHAM IS SIXTH WORST OUT OF 340

number of homeless people dying also increased during these years and a reduction in funding for housing services is linked to increased deaths from drug misuse, accounting for an additional 1,000 deaths between 2013 and 2019.

In 2020, The Doctor reported the story of funding cuts and failed procurement processes at an outstanding-rated GP practice in Nottingham which looked after thousands of the most vulnerable and complex patients in the city.

Commissioners wanted to decrease the funding per patient given to the practice –anything from £160 to £211 a head according to NHS Digital –to around £110 a patient.

The non-profit provider running the surgery said it would lose around £400,000 a year or have to make 40 per cent of staff redundant under the new terms.

‘It basically just fell foul of austerity,’ Jane Turrill, then lead GP for NEMS, which ran the surgery, tells The Doctor. ‘We got paid more money to look after, to provide the same level of service, to patients who find it difficult to access general practice and for us that was predominantly patients with severe multiple disadvantage.

Over the years the amount of money that we got per patient was cut back and back and back. We just couldn’t fight a central thrust to move toward that goal of every GP practice getting the same amount per patient across the whole country.’

This austerity landscape is brutal for the most vulnerable and their health – but also remarkably complex and challenging even for those who feel able to advocate for themselves.

Sleeping rough Jerome Barton had been sleeping in The Arboretum, a small but historic and wellloved park at the heart of the city, for around two months when The Doctor met him. He has qualifications and, until recently, worked in industrial cleaning, but struggled with depression and housing debt and ended up sleeping rough.

The father-of-three says: ‘It doesn’t take a lot to fall out [of work and housing].’ For Mr Barton, who was in contact with local authorities and charities for housing, recent months had featured offers of beds in hostels surrounded by drug addicts. He chose to sleep on the streets instead.

St Ann’s ward, Nottingham

37 PER CENT of adults smoke

38 PER CENT of children aged under 15 live in poverty

46 PER CENT of children in year six are overweight or obese

Statistcs from: 2019 ward health profile

‘For people who are clean it isn’t healthy,’ he says. ‘It’s really difficult.’ Mr Barton could hardly be described as picky – he just wants somewhere with a roof over his head and access to buses to see his children. ‘If I can get a house, I can get a job – I’m confident about that,’ Mr Barton adds.

When speaking to health professionals, charities, and community groups across this city it is rare a conversation passes without reference to the loss of Sure Start. Spending on the programme declined from £1.8bn in 2010 to £600m by 2017/18, resulting in more than 1,000 Sure Start centre closures. These closures came despite an IFS evaluation, which revealed positive health effects, including 5,000 fewer hospital admissions of 11-yearolds each year for children who participated, benefiting disadvantaged children the most. Studies have also shown cuts in spending on Sure Start have contributed to an increase in childhood obesity.

Dr Willott describes Sure Start as ‘one of the few initiatives that actually reverses the inequality of the poorest getting the rawest deal’.

This sort of neglect has hit hard across the country, but

‘It doesn’t take a lot to fall out of work and housing’

:

‘The function of public health was fractured terribly and we’re trying to get that back now’

in few places harder than in St Ann’s – a particularly deprived part of Nottingham which has a tragic history of knife and gun crime. According to the 2019 ward health profile 37 per cent of adults in this corner of the city smoke, 46 per cent of children in year six are overweight or obese and 38 per cent of children aged zero to 15 years live in poverty.

‘End of their tether’ St Ann’s sits right on the edge of Nottingham city centre but retains a distinct sense of independence and isolation. In the 1960s the Victorian terraces here were knocked down as part of ‘slum clearances’ and replaced with a mazy prefabricated estate. Just 50 years later this area feels impenetrable and cut off. The shops at the precinct off the area’s Robin Hood Chase are boarded up and empty. There are precious few signs of life.

Just one door stands ajar on the precinct when The Doctor visits – a dimly glowing light fleetingly escaping out into the pedestrianised courtyard which

the abandoned buildings share. Inside, two apprentices – Dave Gregory and Fatima Woodward – are stacking tins, packets and vital supplies on shelving units which surround the rooms and corridors within the makeshift food bank.

Mr Gregory describes seeing people daily who are ‘at the end of their tether’ – many in employment whom you might not expect to see. ‘It’s really sad – you can’t put it into words that are strong enough and it’s getting much worse,’ he adds. ‘The truth is you don’t know how desperate you could easily be.’

Ms Woodward is a single mum and has taken on this apprentice role through a 13-week Government kick-starter scheme after initially volunteering. She has previously worked in hotels, doing housekeeping, but can only work during school hours now. ‘It can be sad,’ she says. ‘It’s quite hard –they are struggling to feed their kids. That is the most desperate moment.’

Bosses at Nottingham’s hospitals reacted to the

impacts of the cost-of-living crisis and austerity politics on staff in September by providing £2 subsidised hot lunches, with 2,500 bought on average each week. The food bank is part of The Chase Neighbourhood Centre – a local charitable success story which has been supporting people in this deprived community since 1997. Debbie Webster, manager of the centre, is something of a local hero having been involved in the local community since setting up a community group during the difficult 1980s in Thatcher’s Britain.

It started in the pub across the road and now there are 32 paid staff in a purpose-built community hub ‘delivering support to people in crisis’.

‘Sometimes I feel quite pleased, but I wish we didn’t have to have any [staff],’ Ms Webster says. ‘What a sign of the times that is.’ She adds: ‘There’s so much demand. We won’t be able to help everyone and it is getting worse. It’s so worrying. We’re not the solution – we’re the sticking plaster.’

Here at The Chase every

‘Definitely an austerity issue’SHAWN RYAN

opportunity is taken to wrap care and services around people who need help.

There are money-advice staff, benefits advisers, digital support and language classes available, among many other things.

Sherealyn McPherson is one of those being supported when The Doctor visits. The 32-year-old mum of one has struggled with a host of mental and physical health problems, including arthritis and anxiety.

Staff at The Chase are supporting Ms McPherson with a tribunal around sickness benefits after she felt she needed to leave her last job owing to illness. She also gets debt support here. With no money coming in, life is very tough.

She says: ‘If it wasn’t for this place fighting for me, I would have given up. It does get you down and that’s why my anxiety is so bad now. It all makes me wonder what the world is going to be like for my daughter.’

Sheila Jones, employment

support officer at The Chase, who has been working with deprived communities in Nottingham for 20 years, says communities have broken down. She adds: ‘Society needs to invest in people. There are so few things around them… Everything has fallen away.’

Few links between austerity and health are more obvious than in the cuts to the public health grant. With public health moved to local authorities from the NHS in 2012, owing to the Health and Social Care Act, budgets were under even more threat than those in the health service. This has also had the effect of creating silos and fragmenting services.

Nottingham consultant psychiatrist David Rhinds says: ‘It has made a big impact in what we can do as doctors. Before those changes I could see a patient in a clinic, prescribe for them, order investigations and scans and all that sort of thing.’

Now, few of those options are open to Dr Rhinds.

Jane Bethea, public health consultant, who up until recently worked for Nottingham City Council but is now employed by Notts Healthcare, the local mental and community health provider, adds: ‘The function of public health was fractured terribly and we’re trying to get that back now – but we’ve got such low capacity… Frontline public health is under massive pressure.’

The public health grant has been cut by 24 per cent since 2015/16. Within those cuts stop-smoking and tobaccocontrol projects have been cut by 41 per cent, drug and alcohol services by 28 per cent and sexual health services by

23 per cent. Dr Bethea says the cuts to smoking-cessation services, for example, have had a clear effect.

‘You can see that we are actually bucking the trend in Nottingham now, in that smoking prevalence is increasing,’ she says. Cuts have been higher in deprived areas such as Nottingham. And those cuts come despite public health interventions being known to provide value for money: each year of good health achieved costs of £3,800, compared with more than £13,500 if things are left until they require NHS intervention.

There are a hundred good reasons borne from health and simple compassion which mean this situation must change. Yet, even for those immune to such arguments, there is still another – it is more expensive to continue running society in this way than it is to invest in the relief of such widespread suffering.

The second part of this piece will appear in the January edition of The Doctor

‘Society needs to invest in people. There are so few things around them… Everything has fallen away’RHINDS: Public health cuts have affected what doctors can do ED MOSS ED MOSS WOODWARD:

‘[Parents] are struggling to feed their kids’

As a consultant in infectious diseases, Claire Mackintosh knows she has the skills, knowledge and expertise to diagnose and treat patients. But she equally knows she can’t always address the root causes of what is exacerbating their poor health.

to or irrelevant to their presentation.’

the 12 months prior to their referral to the project.

MACKINTOSH:

‘Housing should be treated as a health issue’

‘When you discharge someone to the street it’s just impossible that anybody will improve’

This is why she is so enthusiastic about an initiative to support patients who are homeless, or at risk of homelessness, which is showing remarkable levels of success.

‘When you discharge someone to the street it’s just impossible that anybody will improve, nobody will rehab or get better in that scenario. It’s just impossible to imagine,’ says Dr Mackintosh, clinical director of NHS Lothian’s regional infectious disease unit.

‘There’s almost a moral trauma in not being able to help people with the most important thing that’s causing their ill health. Housing should be treated as a health issue. It’s not separate

Having long had an interest in inclusive health, Dr Mackintosh has helped drive an initiative alongside Cyrenians, a charity that tackles the causes and consequences of homelessness, which operates across much of Scotland. The Cyrenians Hospital InReach service embeds a team of people with expertise in housing and homelessness to work alongside clinicians to identify patients who need support.

Within the first 18 months of a pilot project at Edinburgh’s Western General Hospital, the team supported more than 300 people experiencing or at risk of homelessness to maintain or access accommodation on discharge. They also help them with their needs, including food and attending appointments. An evaluation has shown that these patients were 68 per cent less likely to be readmitted to hospital compared with

‘As clinicians, we don’t carry with us a lot of knowledge around the complexity of the local council-housing situation and all the other strategies around that –this team does,’ says Dr Mackintosh.

‘So, allowing the clinical staff who have got all the training in the biological aspects of the disease and the wellbeing around whatever brought them into hospital to do their jobs by having experts in other parts of health – such as housing –supporting the clinical teams has been hugely helpful.’

People experiencing homelessness often have complex health as well as social needs, says Dr Mackintosh, and being in hospital can be an immensely difficult time for them.

‘You almost need to be an Olympic athlete, mentally and physically, to withstand a hospital admission,’ she says.

A project to support the homeless has reduced the likelihood of their return to hospital significantly.

‘And if you have suffered at the hands of authority, or live a lifestyle that’s lacking social and family support, then it’s even harder. What we’re trying to do is identify the additional needs of patients whose lives have otherwise been very difficult, and who are suffering the health complications of that, and to try to have a bespoke care plan that may encourage and optimise the chances they have of getting a better health outcome.’

This may include help with drug or alcohol misuse – and the consequences of that, such as lung, heart or infectious diseases –and supporting people (who might be on multiple medications) to manage their treatment and medical appointments. It also involves encouraging them to stay in hospital where appropriate, rather than self-discharging against medical advice.

According to Cyrenians, homeless men and women (who have an average age of death of 47 and 43 respectively), experience hospitalisation 3.2 times more than non-homeless patients. The admissions also last on average three times as long, driving up unscheduled secondary-care costs.

‘A vicious combination of inadequate shelter and pre-existing physical and mental health conditions, makes accessing appropriate healthcare and maintaining a healthy lifestyle exceptionally difficult for this vulnerable population group,’ says Cyrenians chief executive, Ewan Aitken.

‘These issues drive increased need for acute and emergency healthcare

among people experiencing homelessness. Our hospital in-reach service has been integral to securing better long-term health outcomes for those who have interacted with our team.’

One service user named Gavin benefited from the initiative following an admission to the Western General with a bad flare-up of psoriasis last Hogmanay. His in-reach support worker helped with practicalities, such as getting him clothes, but was also able to build a trusting and continuing relationship.

‘He made sure I had everything else I needed whilst I was in the ward. I had no one else who could do this for me, I was totally on my own in hospital. Chris has been great and nothing is too much trouble for him. Out of all the support workers I’ve had he’s the only one I’ve been able to talk to and tell things that I wouldn’t tell anyone else. The attention and practical support I got was way more than I expected or have had from other support workers.’

On discharge, Gavin moved to Milestone House, a residential interim care unit that offers support to people following discharge from secondary care. Despite further health problems, he is now doing well.

BMA Scotland council chair Iain Kennedy says the scheme demonstrates how vital access to appropriate healthcare is to those experiencing homelessness.

‘It’s a positive example of how a prevention-led approach can improve health outcomes. We know that as doctors we

can only do so much unless the wider determinants of health and health inequality are addressed and this is a positive initiative that allows doctors to do what we do best, while improving support for patients.’

The project has also helped improve the working lives of doctors. Robby Steel, a consultant liaison psychiatrist, says it has a big impact on him, as well as on individual patients.

‘In 20 years as a hospital consultant, the Cyrenians Hospital InReach service is the single most effective innovation I have seen,’ he says. ‘Sorting someone’s health problems without sorting their homelessness is futile – their health will inevitably deteriorate. Everybody working in the hospital knows this and it is profoundly demoralising. Now we have a team who we can call.’

The in-reach workers deploy kindness, knowledge and tenacity to solve unsolved problems, he adds. ‘Where previously I would discharge someone with a heavy heart, now I discharge them with optimism and the warm feeling of a job well done.’

‘Now we have a team we can call’

bma.org.uk/thedoctor

‘I

’m more than sure that most of the people will celebrate Christmas within their families but I’m afraid that those celebrations may be by candlelight and without electricity.’

As with millions of Ukrainians, Kyiv-based child psychiatrist Dmytro Martsenkovskyi has learned to endure the blackouts and power shortages which have become a daily reality in a nation fighting for its freedom.

The illegal Russian invasion of Dr Martsenkovskyi’s country back in February has seen 10 months of fighting, bloodshed and senseless destruction, as well as the displacement of millions of Ukrainians from their homes.

Despite continued international support and signifi cant advances towards liberation and repelling Russian forces, most notably at Kherson, Ukraine faces a hard and uncertain Christmas, which some celebrate in early January, if they follow the Eastern Orthodox tradition.

For Dr Martsenkovskyi, who has remained in Ukraine’s capital since the outset of the invasion, thinking about the festive season and what it and the future might bring is difficult.

‘Among my colleagues and friends,

compared to past years, there is no talk about celebrations as everybody is living in the moment,’ he says.

‘To my knowledge most of the population has asked not to decorate the cities and to instead spend money on the military or for those who are displaced.’

Reversals on the battlefield have seen the Russian military deliberately target Ukraine’s civilian energy infrastructure, a strategy that has left homes, businesses and public services without power.

With the winter months likely to see temperatures plummet, there is concern in Ukraine and internationally about a potential humanitarian disaster for health.

However, Dr Martsenkovskyi insists the blackouts have had the opposite effect intended by Russia’s president Vladimir Putin’s forces by strengthening, rather than breaking, the determination and resolve of the people and the health services they depend on.

‘We are learning to live without electricity and the internet,’ he says.

‘Some days, I wake up and there is no electricity. I go to work and when I come again at home, there is no electricity. But I feel it’s a

wake up and there is no electricity. But I feel it’s a small price to pay for victory’

Ukrainian doctors who celebrate Christmas will still be wishing ‘Veseloho Rizdva’ to their patients, and all will be sharing in their hardship, danger, and determination to prevail.

Tim Tonkin reports

small price that you can pay for victory.

‘Most of the hospitals where I’m working have their own system of heating – they are making their own electricity from solar panels. There have, however, been several occasions where there have been issues with power that have led to operations having to be delayed.’

Despite the intense pressures posed by power shortages, Dr Martsenkovskyi says most hospitals have managed to remain open and operational, a fact he views as all the more impressive considering the massive effect the war has had on Ukraine’s medical workforce.

Similar to Dr Martsenkovskyi, neurologist and medical director Natalia Zhhilova has remained living and working in Kyiv throughout the invasion.

As with the city’s hospitals, Dr Zhhilova’s practice has so far been able to contend with power cuts thanks to its petrol generator, while shortages of medical supplies are generally not as acute as they were in the initial months of the war.

She says Christmas Day this year is likely to be a challenging one for Ukrainians, but one that people will still be determined to observe and celebrate as best they can.

‘It will be a very hard day because a lot of people will be separated and a lot of people won’t see each other,’ explains Dr Zhhilova.

‘A lot of people have left Ukraine because of the war and a lot of other people are still

trapped in occupied territory.

‘I think it will be a terrible winter. But for me and for my friends and family, we are ready for this. We just want to win [this war].’

With Christmas traditionally a time for refl ecting on the things which matter most, Dr Martsenkovskyi says thousands of people throughout his country would want to send a message of determination but also of immense gratitude to the rest of the world for the solidarity and support shown to Ukraine.

He adds that, while the uncertainty wrought by the war is forcing most Ukrainians to adopt a ‘day-by-day’ approach to life, he remains hopeful his workplace will still be able to observe Christmas to some extent, something he feels is particularly important for young patients such as his.

‘In the hospital, we have psychological and social services that usually organise celebrations at Christmas,’ Dr Martsenkovskyi explains.

‘There is always something like a concert organised by volunteers and staff and there is also the children’s choir in the hospital.

‘In big cities Christmas traditions are less popular but in small cities and villages you will see children going from house to house and singing Christmas songs and I think the war will have no effect on this tradition.’

‘You will see children going from house to house singing Christmas songs’

When Kirti Singhal first arrived in the UK from India at the end of 2020, she was met by the usual and frequently daunting challenges which face doctors who have qualified overseas and who have little to no experience of the NHS.

Yet, to gain GMC registration and awaiting dates to complete her Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health exams, Dr Singhal’s situation was further complicated by the fact the UK had re-entered lockdown shortly after her arrival, which made finding clinical attachments almost impossible.

Today, Dr Singhal is a clinical fellow in the paediatric intensive care unit at St George’s Hospital in southwest London, a fact she credits in large part to the trust giving her the opportunity to gain hands-on experience through the MSW (medical support worker) programme.

‘I believe if I had not been enrolled in the MSW, I would probably have had much more difficulty getting a date for my clinicals,’ says Dr Singhal.

‘[The MSW programme] helped me develop my communication skills with the patients, it gives you practice on how to examine patients and you always get immediate feedback from the consultant because you’re always with them. It is a very good stepping stone to gain NHS work experience.’

Introduced during the height of the pandemic, the MSW programme aims to give

doctors, including IMGs (international medical graduates), the chance to work in supervised, supporting roles in the NHS, while working towards the completion of assessments such as the PLAB (professional and linguistic assessments board) examinations and, ultimately, medical registration.

The success of the programme, which was rolled out across England following a successful pilot, has meant NHS England has confirmed it will continue to fund the scheme until the end of March next year.

St George’s paediatrics unit was the first department in southwest London to adopt the MSW programme and has this year seen six IMG doctors join the scheme, of which four have since gone on to complete their GMC registrations.

The trust’s clinical director for children’s services and consultant neonatologist Sijo Francis was instrumental in implementing the MSW programme at St George’s roughly 12 months ago.

Having qualified in South Africa before coming to the UK, Dr Francis says he understands the challenges facing doctors coming from overseas such as cultural differences and unfamiliarity with NHS working practices.

‘I thought this is a really great idea,’ he says. ‘Rather than having doctors coming from overseas paying lots of money for courses on

‘It is a very good stepping stone to gain NHS work experience’

Doctors who qualified overseas have been given experience on the wards, which helps them obtain GMC registration and relieve workload pressures for colleagues. Tim Tonkin reports

SINGHAL : Communication skills enhanced

how to pass the PLAB exams, we get them into a hospital, train them ourselves [and] give them opportunities to learn by experience.’

Doctors who sign up to the MSW programme are normally contracted to work under supervised conditions for six to 12 months.

Without GMC registration, there are understandable limits to the responsibilities they can be entrusted with, and support workers are unable to prescribe medication or manage patients without direct supervision.

Dr Francis says, however, that incorporating highly skilled overseas doctors into an existing workforce has huge benefits for the doctors and the trusts taking them on.

‘The feedback from colleagues in the ward has been spectacular. Because this is a new role it’s effectively additional workforce that we haven’t had before [and] it has actually taken a huge load off the clinical team by having an additional group of people who are very highly skilled,’ says Dr Francis.

‘We’ve used [support workers] within their licence, but we’ve also seen this very much as an opportunity to train so [we’ve given] them access to the same training programme that our junior doctors have and tried to give them opportunities to do additional courses or have some additional time off to study.’

Originally from Nigeria, Taiwo Babatola is participating in the MSW at St George’s, having moved to the UK in February 2021. Having recently passed her first PLAB exam, Dr Babatola says she hopes to pursue a career in general practice eventually, specialising in paediatrics, and credited the support and experience she gained through the MSW programme.

‘I’ve learned so much working in the NHS and I have more confidence and examine patients more because I work under supervision and there are people [other staff] we can call on at any time,’ she says.

‘I’m so grateful for this opportunity to join the NHS and make a difference. Thank you to all my colleagues and clinical supervisors for believing in me and continuing to support me throughout this programme.’

With IMGs now making up more than half of new GMC registrations each year, the BMA has continued to call for greater resources and support to be provided to those students and doctors seeking further education and training or a new career in the UK.

This year saw the association launch its affiliate membership programme which aims to provide doctors with a broad range of advice, guidance and practical support to help them in their transition to the NHS before they arrive.

For St George’s and many other trusts, the MSW programme is not simply a short-term fix for boosting staff numbers, but an opportunity to invest in the doctors of the future and the NHS. Twenty per cent of those who have enrolled on the MSW programme are refugee doctors. The experience they gain helps to alleviate the challenges they would likely have faced in accessing clinical attachments, says the BMA.

‘The key measure of success is that we don’t keep people in these roles,’ says Dr Francis.‘We want these doctors to become successful and leave the MSW programme and go on and become a fully fledged doctor in our community.’

For more information about how the BMA is supporting IMGs through its international affiliate membership, go to affiliate.bma.org.uk

‘It has taken a huge load off the clinical team’BABATOLA

: Confidence has grown

Junior doctors in England will ballot for industrial action next month. Action would focus on restoring pay after years of real-terms cuts but – as doctors tell Ben Ireland – there are many other serious issues which undermine morale

THACKRAY: ‘It’s very difficult to take time out because there’s nowhere to rest’

‘J

unior doctors can’t take proper breaks,’ says Vassili Crispi. ‘We sit in front of our computer to work, eating a sandwich, sometimes holding a bleep.’

Dr Crispi, a foundation year 2 in West Yorkshire, explains: ‘Even if you’ve told colleagues you need a break, you’ll probably be bleeped.’

Many NHS hospitals’ staffing levels are so stretched now that junior doctors cannot escape bleeps on a fiveminute rest to grab a coffee or snack. These are doctors who invariably work beyond their contracted hours, often at unsociable times, for as little as £14.09 an hour.

‘That private time to regenerate is taken away from you,’ says Dr Crispi, currently on a neurosurgery rotation having started his F1 year during the peak of COVID. ‘It’s frustrating. The effect tiredness has on doctors, let alone on patients, is underestimated.’

Research by the BMA’s population health team found 46% of trusts have taken no action to ensure trainees get uninterrupted breaks overnight (except in emergencies), a recommendation of the BMA Fatigue and Facilities charter in 2018. Of those trusts, 89% have no plans in place to introduce this policy.

Doctors being sufficiently rested is critical for patient safety as well, night or day.

Dr Crispi says: ‘Even a 10-minute break is important to recharge, and I think patients would agree. You don’t want to see a doctor when they’ve worked overnight with no break and seen dozens of patients. You want a well-rested doctor with a clear mind.

‘I’ve worked with colleagues who have not taken

a break after eight to nine hours of a 12-hour shift or even none entirely. They’re very different people to when they started their shifts. We’re constantly seeing patients, putting up with high levels of stress, coping with emergency, making sure we’re prioritising the right patients, always running around – it uses up a lot of energy, mentally and physically.’

Norwich-based core surgical trainee Roshan Rupra says: ‘I’ve yet to have an uninterrupted break during my four years as a junior doctor. In an ideal world there would be enough staff available to cover. Then uninterrupted breaks would be feasible.

‘If I have lunch at all, it’ll be a working lunch. I end up having a shake because it’s fast, cheap and I can have it on the go. I’m frequently on the go.’

Kerrie Thackray, a specialty trainee 4 registrar in Hertfordshire, says: ‘As one of the more senior doctors overnight, I try to say how important it is to get a break to the foundation year doctors because there’s very little that can’t wait 20 minutes.

‘But I probably don’t often practise what I preach because we’re all so conscious of just how much needs to be done. You might have the emergency department phoning because patients have been waiting eight hours. You don’t know what’s waiting, so it’s often easier to carry on and try to deal with what’s in front of you.’

‘The effect tiredness has on doctors, let alone on patients, is underestimated’FRONT LINE: Junior doctors protest in July in London

Poor facilities in hospitals’ doctors’ messes are bringing down morale among juniors.

Dr Crispi says many doctors’ messes must be improved to offer ‘a base’ with ‘a sense of community’ to ‘meet your colleagues, unwind, rant, have something to eat or try to sleep a little bit when that’s possible’. Rooms might include rest areas, a kitchenette, toilets and computers for ‘some isolated space away from busy clinical areas’, he suggests.

‘As an F1 or F2 you change hospitals every few months,’ he adds. ‘By the time you’re embedded it’s time to move and you’re a brand-new doctor needing to acclimatise again. We need an area where we belong.

‘In one trust with hundreds of junior doctors there’s a mess the size of a bedroom with a collapsed sofa and another sofa propped against the wall because it’s unfit for purpose, a toilet with a flush that doesn’t work, leaking showers and one without a lock.

‘If you’re lucky enough to get some sleep on a night shift there are usually two solutions. One is to put chairs together and the other is to lie on the floor. Sometimes people end up using pillows taken from somewhere on the ward. Some facilities are better than others, but that’s quite common. It’s not the glorious profession many of us envisioned, let alone what the public think.’

Dr Thackray adds: ‘When I’m on as the medical registrar, I’ll be getting bleeps from all over the hospital. It’s very difficult to take time out because there’s nowhere to rest.

‘We know taking a 20-minute rest, or having a coffee, improves your cognitive ability significantly. But where? You could maybe squeeze in a 20-minute nap, but it would be in a brightly lit room on the floor or a sofa, and you’ll probably get repeated bleeps.’

Dr Rupra says: ‘Doctors often don’t have a protected, separate space or, if they do, it’s not clean. It’s normally two or three uncleaned sofas and a pillowcase that’s been on for months.’

He points out ‘some hospitals don’t even have a mess’, while others have off-site facilities, which are ‘not feasible’ for doctors carrying bleeps. ‘I’ve seen some pristine messes,’ he says. ‘But that’s because no one is using them.’

Supporting each other Juniors say it can be tense to eat in the same canteens as patients when hospitals are so stretched.

‘I’ve heard of doctors being booed in waiting areas, so going into a canteen might not be the most appropriate setting,’ says Dr Rupra. ‘There should be a

separate area for doctors.’

The 2020-21 NHS People Plan called for trusts to offer ‘safe spaces for staff to rest and recuperate’.

It also recommended each trust hires a wellbeing guardian ‘to look at the organisation’s activities from a health and wellbeing perspective and act as a critical friend’. But the BMA’s research found 45% of trusts had not and, of those, 66% had no plans to.

Dr Thackray says she has ‘never heard of’ wellbeing guardians. ‘Sometimes we get encouraged to do wellbeing activities and e-learning about how we can manage our time and stress, but that feels like giving us another thing to do without dealing with what’s causing the wellbeing issues,’ she adds.

Dr Crispi is ‘not surprised’ trusts haven’t followed through on the recommendation and says junior doctors have taken the role into their own hands by looking out for each other.

‘One of the strongest measures we’re taking is calling out when colleagues haven’t taken a break,’ he explains. ‘Someone else telling you that you need a break can be a stronger prompt. Quite often you don’t take a break because the workload is so significant.’

Dr Rupra set up a wellbeing hub in his trust off his own back during the height of COVID. ‘I wonder if I was

‘Doctors often don’t have a protected, separate space or, if they do, it’s not clean’

RUPRA: Bleep-free training is essential – but who else would hold the bleep?

supposed to be the wellbeing guardian at that point?’ he jokes.

He queries if such a role would work in practice, adding: ‘Junior doctors are very aware wellbeing is extremely important. We know we need to look after ourselves, but the job doesn’t lend itself to that.’

The BMA’s research found 32% of trusts had taken no action to implement a peer-to-peer mentorship programme. Of those, 50% reported no plans to introduce such a policy.

Dr Thackray did receive support when returning to work after seven years out to raise her children and found it ‘really helpful’ and ‘quite refreshing’. But she says she is ‘particularly concerned’ about foundation year doctors who have been ‘shifted around the country’ on rotation and ‘don’t have social support’, lacking access to mentors who she thinks would be ‘really valuable’ for them.

trusts aren’t fulfilling,’ he says.

It seems obvious that studying the ever-evolving subject of medicine is easier without interruptions. However, according to the BMA’s research, 29% of trusts have taken no action to ensure bleep-free training for junior doctors and, of those, 21% have no plans to.

Dr Rupra says: ‘Bleep-free training is essential to staying up to date with our knowledge.’ The issue, he says, is ‘who else is going to hold the bleep?’

He explains the number of gaps in junior doctor rotas means a more senior doctor would be required to step down to cover if juniors are in protected training, ‘and, if they did, they might have to give up their current duties and patients would lose out’.

mess the size of a bedroom’

Dr Rupra says he was asked about mentoring someone but was not offered a mentor himself. Instead, he has approached seniors for informal guidance and joined the Association of Surgeons in Training.

‘That’s one way doctors are plugging a gap their

CRISPI:

‘Private time to regenerate is taken away from you’

‘The reality is that doesn’t happen, and junior doctors are forced to hold a bleep and either not attend their teaching or attend while being interrupted and thus not learning. This means junior doctors feel less valued and will either try and remediate that work in their own time or leave the profession. And that’s really sad.’

Dr Thackray says a hospital she worked at relies on junior doctors’ personal phone numbers in place of bleeps, and they ‘sometimes get bleeped when they’re not on call’ as a result. She agrees ‘bleep-free training is important’ for career development.

Access to hot food might be seen as a basic right for employees regardless of profession. But the BMA’s research found only 18% of trusts have fully implemented the recommendation from its Fatigue and Facilities charter that staff should have access to hot meals 24/7.

‘Junior doctors are working incredibly long shift s without provision,’ says Dr Thackray. While she says ‘the overnight provision of food has been better in recent years’ she notes ‘some trusts only have vending machines with microwave meals’.

One of Dr Rupra’s colleagues brought in a microwave because ‘the department was so sick of not having access to hot food’, but that still required health and safety clearance. Car-parking charges are considered a de facto tax on doctors – and can be a risk to patient safety when those doctors are on call. But 71% of trusts have no plans to implement on-call designated parking spaces – something the NHS committed to as part of the BMA Fatigue and Facilities charter.

Dr Thackray, who pays £40 a month for a staff permit, says there is ‘almost never’ a space when

‘In one trust with hundreds of junior doctors there’s a

arriving for a twilight shift, so she ends up paying £10 extra a day to park in patient spaces to avoid a dark walk from an area where residents get frustrated at the overflow, and to save time so she is not late home for childcare responsibilities.

Many hospitals have removed provision of parking spaces for on-call doctors, adds Dr Rupra, who says: ‘If a doctor were not to attend their on-call shift because they couldn’t find or afford parking, I would be very worried they might get called to a meeting and be scapegoated. The hospital wants us to work, but isn’t helping us to.’

The combination of these wellbeing issues leaves junior doctors tired, frustrated and seeking change as part of the upcoming industrial action ballot. They feel paying staff more fairly will lead to fewer rota gaps and help begin to ease some of the wellbeing pressures outlined by the BMA’s research.

At the moment, as Dr Rupra says: ‘No one has time to look after their own wellbeing. Covering your own work is difficult but doing two people’s jobs is near impossible. We don’t even get a thank you for that, it’s become an expectation.

‘Junior doctors take a lot of pride in our work. We want to do it to a really good standard, which requires time. If it’s not done to a good standard, you don’t progress in your career and you’re stuck. The system is built so that we don’t get time to look after ourselves.

‘It leaves a really bitter taste in my mouth to have to say these targets are not realistic. The sad truth is the system we’re working in has so many rota gaps and leaves doctors not feeling valued. A big part of that reason is because we’re not being paid what we feel is correct. It’s a domino effect.’

Dr Crispi adds: ‘No matter how dedicated you are to your work, it’s affecting your personal life. Our days off are practically just spent recovering.’

But he is hopeful of change. While doctors may historically have been ‘reluctant to talk about ourselves and our mental health’, Dr Crispi says ‘a new generation of doctors are more willing to bring up these discussions and speak up when things aren’t going well’.

Profiles of each of the junior doctors quoted will be published at bma.org.uk/thedoctor

Ergonomically designed on the outside, inside it’s one of the most advanced reading lights in the world.

O ering crystal clear clarity and incredible colour rendition, a Serious Light is perfect for anyone who struggles to read small print for any length of time or who needs to see ne detail.

It will transform your visual experience.

Using Daylight Wavelength Technology™, inside every Serious Light are the latest special purpose purple LEDs, patented phosphors and bespoke electronics. The end result is a powerful light beam that closely matches natural daylight, something our eyes nd most comfortable to read and work by. When combined with the ability to adjust the beam width, dimming facility and fully exible arm, a Serious Light enables you to enjoy reading again in complete comfort and see colours like never before.

bma.org.uk/thedoctor

As the patient’s husband opened the door, I was vomiting into the snow. Although only a six-mile taxi ride, I have never travelled well.

Born dead it was, said the man, who waited for me to stand up.

I was a medical student, and for obstetrics we had to carry out 12 hospital-based deliveries and 12 domiciliaries. I still needed to carry out five domiciliary deliveries, but for this one I was too late in every sense.

When I entered the tiny bedroom, Mrs McGrath was lying in bed, as white as the paper I write on. She emitted almost animal-like sobs.

He’s over there, doctor. It’s no use.

There he was, encased in newspaper. A perfectly formed boy with umbilical cord and placenta attached. But he was blue, and not the waxy white I expected. I had to try, at least.

Milking the blood from the cord, I began to blow into the tiny mouth. The parents looked on almost in revulsion, feeling that my efforts were not only a waste of time but were cruel in that they pretended to create hope where they felt there was none.

I prayed a silent, almost feverishly threatening prayer. My thoughts being loosely translated suggested that if God really did exist, this was the time for him to get off his throne, or wherever he resided, and come and help me. I continued blowing into the tiny mouth.

Fortunately, I had only partially learnt the technique, for I forgot to take my mouth away when inhaling. Suddenly and quite accidentally, I dislodged a large plug of mucus. In an instant, that which seconds before had been an inert purple brick-sized bundle of flesh and bone, began wriggling and gurgling in my hands. Chameleon-like, the sombre colour was replaced by a vibrant pink.

No words of mine can convey the ecstasy; the elation and the sheer unbridled pleasure that that movement and that sound gave me, feelings shared by the two amazed parents.

The ambulance took mother and baby to Dublin and Mr McGrath embraced me. The top of my head was well below the level of his chin, and I felt his tears run down my forehead and cheeks, where they mixed with my own.

It was the winter of 1959. I took a last lingering look around the tiny bedroom, my gaze fixed on the torn crumpled newspaper that a short time earlier might have been the paper shroud of a man who hopefully somewhere recently celebrated his sixty-third birthday.

My first resuscitation, my only resuscitation, and the greatest event of my life.

Doctors’ experiences in their working lives

I regularly write about the state of the healthcare environment we work in and the brutal effects of facing relentless demand with continually dwindling resources.

To date, the Government has ignored our calls for action – and ministers have buried their heads in the sand despite our repeated warnings about staff burnout and patient safety.

However, those calls are going to become harder to ignore this winter because doctors and other healthcare staff are deciding enough is enough. At the time of going to press nurses are expected to take at least two days of industrial action, and next month junior doctors across England will be balloted on their own.

In the case of my colleagues, it is hardly surprising this question is being asked given the sustained and continued real-terms cut of more than a quarter to our salaries since 2008/09 while working in an increasingly impossible environment.

The statistics behind our demands for action could hardly be any starker. The NHS in England alone has 133,000 unfilled clinical vacancies. We have one of the lowest ratios of practising doctors per 1,000 inhabitants in the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) – we have 2.9 per 1,000 compared with Austria at 5.6 and the OECD average of 3.7.

BMA analysis suggests we would need some 46,000 doctors to meet the OECD average. And it’s not just about doctors. We are down at the bottom of the list when it comes to the number of hospital beds per 1,000 people and have one of the lowest ratios for CT scanners to population. The effects of all this under-investment are becoming ever clearer now. They include having 8.9 million people on the waiting list for secondary care in the UK, GPs managing ever-increasing risk in the communities and healthcare staff say they feel they have to take industrial action.

The numbers only tell part of the story. All of this is evidence for what most of us see in our daily working lives – that our colleagues are struggling under the burden of all this need, and that we aren’t able to give patients the safe, high-quality care they deserve. And this is a safety

issue. So often we are having to say to patients: ‘I’m sorry I’m late,’ or ‘I’m sorry you don’t have a bed’ and ‘I’m sorry I haven’t got the time to talk to you in more detail’. This leads to moral distress – to genuine moral injury. It leads to a broken workforce. And a broken workforce means poor care for patients.

If the Government needs any roadmap for how we ended up here – with industrial action being planned –this is it. Doctors, and other healthcare workers, are now saying ‘not only do I need to take this action for myself but I need to do it for my patients and society’. I applaud people who are taking this stand.

Beyond the under-resourcing, the relentless demand and the moral injury there is another reason why the NHS can be a brutal working environment: culture. Often, we are told we have to fill a rota gap because hospital staff need us to or the GMC would say we have to help out. This is nonsense – as doctors we are not responsible for fixing the existing unsafe staffing levels and management of health services. As we approach the festive season, typically a time of reflection, I want you to know your BMA sees the difficulties you face and is fighting for better and demanding change.

We recognise the pressures on you, and we are having these conversations with ministers and stakeholders day in day out, trying to drive positive change.

In the meantime what is really important is that our members aren’t put under undue pressure – and don’t feel a personal responsibility to solve the NHS’s problems, when those issues lie with politicians and health leaders.

This festive period, take time to reflect. If you need help and support please contact the BMA. We are your trade union and we have your back when you need us. We also offer counselling sessions completely free, with support available 24/7.

As always, you can also contact me via email at RBChair@bma.org.uk

In a health service starved of investment and with a brutal working environment, doctors are saying enough is enough@drlatifapatel Dr Latifa Patel is chair of the BMA representative body

When it comes to persuading a medical royal college to be fl exible, it might seem a combination of COVID, pregnancy, and repeated efforts to keep in touch would be enough. But one trainee was completely rebuffed.

The doctor was studying for a diploma commonly undertaken by those in her specialty. By the end of 2019 she had completed the inperson courses and e-learning modules, as well as the knowledge assessment. She was now advised to fi nd a trainer locally to complete the assessments. Unfortunately, the names on the website were out of date – one of the trainers had retired, and another was not offering training.

exposure, and the risk of contracting COVID, at a late stage of pregnancy.

She needed guidance on what would happen with her diploma. She had made contact in March and was told she would hear back shortly. She chased in June, then November, then December. When she fi nally heard back, she was told the deadline for the diploma had now passed, she could no longer complete it, and she would have to sign up to a new one, with a new curriculum, and start from scratch. And she would have to pay the course fees all over again.

Highlighting practical help given to BMA members in difficulty

The following year, the pandemic struck. The doctor continued her search for training but was advised locally none was available because of the pandemic. She contacted the body responsible for awarding the diploma by phone and email but received no advice or support.

In January 2021, she was told she could have an extension until the following December. But it was of little use. The country was back in lockdown, and there was still no training locally. In March, she told the college that she was pregnant. She was only able to have the COVID vaccine several months later, once it was deemed to be safe for pregnant women. While she was able to return to face-to-face working for a month before going on maternity leave, had she travelled for her assessments it would have increased her patient

Clearly, this was unacceptable. If she had not been pregnant, she would have been given the opportunity to undertake the assessments, but she had been given no alternatives in the circumstances, and this felt like discrimination.

With BMA support, she met three senior figures who were responsible for the course. She was able, at last, to express the diffi culties she had faced. They offered her a chance to sign up to the new diploma, waived the entry fee, and told her she did not have to duplicate any of the work she had previously completed for the previous one. She accepted this, and because she was happy with the outcome, decided not to pursue a claim for indirect discrimination.

BMA members seeking employment advice can call 0300 123 1233 or email support@bma.org.uk

The Doctor BMA House, Tavistock Square, London, WC1H 9JP. Tel: (020) 7387 4499

Email thedoctor@bma.org.uk Call a BMA adviser 0300 123 1233

@TheDrMagazine

@theBMA

The Doctor is published by the British Medical Association. The views expressed in it are not necessarily those of the BMA. It is available on subscription at £170 (UK) or £235 (non-UK) a year from the subscriptions department. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the editor. Printed by William Gibbons. A copy may be obtained from the publishers on written request.

The Doctor is a supplement of The BMJ. Vol: 379 issue no: 8364 ISSN 2631-6412

Editor: Neil Hallows (020) 7383 6321

Chief sub-editor: Chris Patterson

Senior staff writer: Peter Blackburn (020) 7874 7398

Staff writers: Tim Tonkin (020) 7383 6753 and Ben Ireland (020) 7383 6066

Scotland correspondent: Jennifer Trueland

Feature writer: Seren Boyd

Senior production editor: Lisa Bott-Hansson

Design: BMA creative services

Cover photograph: Getty

Read more from The Doctor online at bma.org.uk/thedoctor

A medical royal college’s lack of flexibility meant a doctor faced the prospect of starting her diploma all over again