Care, virtually Monitoring patients at home

Chaotic and unsafe

The risks of new anti-strike legislation

Devolution’s back

But can it help the Northern Ireland health service?

3

At a glance

New safety guidance on physician associates

4-7

Let down by society

The crisis in mental healthcare

8-11

A heavy load

Will the newly restored government in Northern Ireland be up to the task?

12-15

Heal at home

The growing role of ‘virtual wards’, where patients are monitored remotely

16-17

Continuing resolve

Junior doctors are determined to carry on with industrial action

18-19

‘From rescuer to coach’ Encouraging patients to take more responsibility for their own health

20-21

Industrial action under attack

Why new legislation could cause chaos and risk patient safety

22-23

Your BMA

The importance of mutual respect

This Government has unified doctors more than ever before. After years of being taken for granted and undervalued through real-terms wage cuts, being patronised with applause while we burn out in our workplaces, and juggling the soaring demand caused by a sicker and poorer society – we are standing up together and you are taking action. Junior doctors, consultants, SAS doctors and GPs are all now in dispute with a Government which has its head in the sand while our NHS falls apart. You can find out all the latest on industrial action across the profession in this edition of the magazine.

Not only do ministers fail to come to the table or produce pay offers which respect the work we do, they are also trying to drive through minimum service level legislation, which would undermine our right to win better terms and conditions for our members. In the March edition of The Doctor, BMA deputy council chair Emma Runswick explains the latest with this legislation and the effect it would be likely to have. Your BMA has campaigned against these proposals and will continue to do so, taking lessons from our colleagues across the trade union movement as we go.

In this issue of the magazine we look at the growing phenomenon of ‘virtual wards’, speaking to doctors, patients and organisations making use of them. We know hospitals are often not the right place for patients – particularly those who may just be waiting for tests or having relatively basic monitoring – and technology can create opportunities for doing things differently. As this piece identifies, however, while the wards themselves are ‘virtual’ they still need to be staffed. We already have an acute workforce crisis, and the Government has failed to come up with a viable plan to address this desperate situation.

We report on a landmark BMA publication looking at the experiences of doctors working across mental health services in this country. It follows brilliant work in The Doctor’s award-winning Paucity of Esteem series in exposing the parlous state of mental healthcare and shines a spotlight on the stark realities of life for doctors trying to care for some of the most vulnerable people in society.

By no means lastly, also in this edition of The Doctor, doctors from across the branches of practice in Northern Ireland set out their hopes and concerns after the return of devolution, in a part of the UK which suffers far worse waiting times than the mainland. It is sobering reading and reminds us the BMA still has so much to do across all four UK nations.

Keep in touch with the BMA online at instagram.com/thebma twitter.com/TheBMA

‘Make no mistake. The current situation on the ground is a failure that today’s publication seeks to address.’

This was the sober and uncompromising assessment delivered by BMA council chair Philip Banfield to assembled members of the press, as the BMA launched its landmark national guidance on how MAPs (medical associate professionals) should be safely utilised within the NHS.

The guidance, which was unveiled during a press conference on 7 March, is the first framework devised by doctors which provides a safe scope of practice for MAPs, a term which encompasses physician and anaesthesia associates.

Setting out six general principles governing the deployment of MAPs, the guidance also uses a simple traffic light-style system determining which procedures, from a by-no-means exhaustive list, should and should not be tasked to such staff.

Among the red lines in the guidance is an absolute prohibition on MAPs being responsible for undifferentiated patients, and a requirement for close supervision when caring for triaged patients.

‘MAPs have an important role in the NHS, but only if we can provide a framework for safe and effective practice,’ Dr Banfield explained.

‘The public does not understand that physician associates work as doctors’ assistants, or that they have increasingly been placed in positions with inadequate supervision and with huge local variation in what they are expected to do.

‘This is a crucial guide for safe practice, drawing on doctors’ expertise and experiences. It is a clear explanation of how MAPs can be employed to maintain the provision of high-quality safe patient care in the NHS.’

The role of MAPs within the NHS is one that has garnered increasing controversy and concern in recent years, owing to uncertainty with the level of responsibility and supervision MAPs should receive, and

confusion among many patients as to the professional status of these staff.

This lack of clarity was tragically emphasised in 2022 following the death of Emily Chesterton, with Ms Chesterton having been incorrectly diagnosed by a physician associate working at her GP surgery, whom she had believed to be a doctor.

Attending the launch of the guidance, Emily’s parents Marion and Brendan made clear their belief that had such a safety framework been in place two years ago, their daughter would still be alive today.

‘In our daughter Emily’s case, we did not find out she had seen a physician associate on two consecutive occasions and not a GP, until the week before her inquest on 21 March 2023,’ Marion said.

‘We believe that the present title of physician associate is confusing, inaccurate, and sounds grander and superior in qualification and status to a general practitioner and should be changed to “doctor’s assistant”.’

Despite a survey of more than 18,000 doctors revealing that 87 per cent of respondents felt the way in which MAPs are used in the NHS either ‘always’ or ‘sometimes’ posed a risk to patient safety, the Government is pushing ahead with plans to expand the numbers of these staff greatly during the next decade.

Ministers have also succeeded in passing legislation that will see physician and anaesthesia associates being placed under the remit of the GMC, a move the BMA has warned risks further blurring the distinction between doctors and MAPs.

‘We wholeheartedly agree that the Health and Care Professions Council must regulate the use of MAPs and not the GMC,’ warned Marion.

‘If the GMC is the regulator, and there are no plans to set parameters on the scope of practice of MAPs, the confusion and potential risk to patient safety will continue.’

To read the safety guidance on MAPs, visit bma.org. uk/UncertainIsUnsafe

bma.org.uk/thedoctor

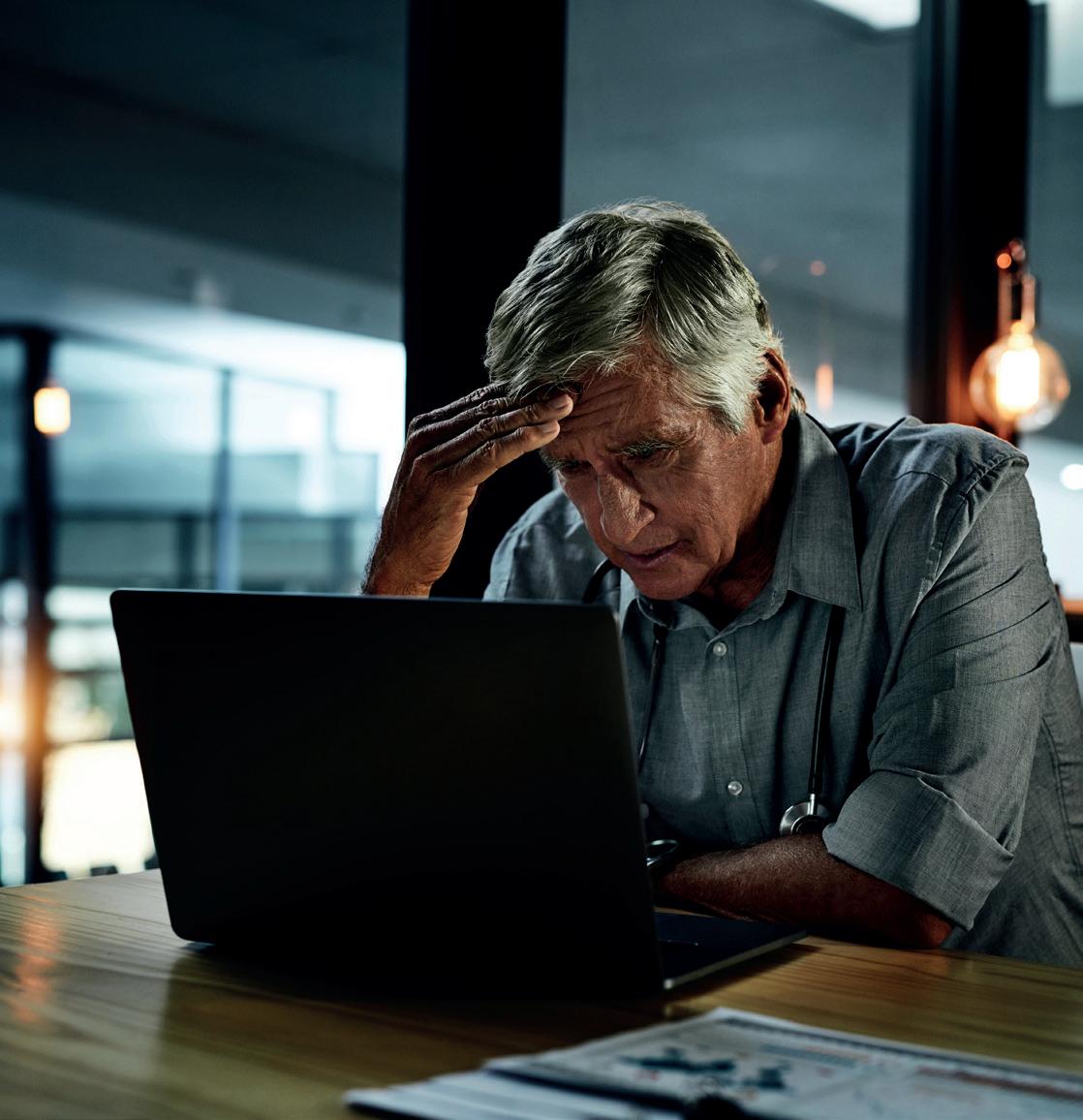

IN NEED: Services, including those for young people, are struggling to meet demand

Mental healthcare in England is in crisis – it is ‘dysfunctional’ and ‘broken’. These are the revelations of a BMA study of mental health services, which brings together findings from interviews with doctors on the front line, analysis of data and input from charities and patients.

Peter Blackburn reports‘When we (society) make people mentally unwell, we do not have the staffing, funding or physical space to enable them to become well again.’

This assessment – from an English psychiatrist whose anonymity has been protected as part of an indepth investigation into the state of mental health services across the country – lays bare the truth: society is making people mentally unwell and our systems and structures are unable to respond adequately when this happens.

These are painful, and costly, truths. It has long been clear good mental health is essential to a functioning society. Mental illness carries a huge cost to individuals and society as well as the health and social care system – some £101bn in England alone at the last estimate, roughly 5 per cent of the UK’s GDP. Without appropriate treatment or support, mental illness can lead to lost productivity and the need for informal care. And away from the balance sheets, poor mental health can cause huge anguish to individuals, families and communities.

A recent review of more than 150,000 people in 29 countries found that around one in two people will develop at least one mental health condition in their lifetimes. And rates appear to be increasing, with the COVID-19

pandemic, in particular, having a significant effect on people’s mental health.

Rates of mental health conditions among children and young people seem to be rocketing, too. Between 2017 and 2022, rates of probable mental disorder in England increased from around one in eight young people aged seven to 16 to more than one in six.

In England, following decades of neglect, there have been moments of hope surrounding mental healthcare – with many ambitions and plans outlined to tackle the paucity of esteem between mental and physical healthcare.

Commitments to various areas have been made alongside the introduction of waiting-time targets and access standards for services.

However, demand continues to outstrip investment and many targets are not met. Services are widely reported to be overwhelmed by the numbers of people requiring care or seeking help and the system is under huge pressure. Government figures show that the number of people unable to access the treatment

they need in a timely manner continues to increase.

It is in this desperate landscape the BMA has published a study investigating the state of things through the eyes of doctors, patients and other experts. The report included in-depth interviews with 10 doctors from across the mental health system, including those working in psychiatry, general practice, emergency medicine and public health.

This group of doctors were asked about their experiences of providing care, what helps and hinders them in their workplaces, how things have changed during their time in the service, and how the challenges of today affect patient care. These interviews were supplemented by discussions with patient groups and charities.

The BMA study found doctors are struggling to ensure patients receive the care they need in the face of inadequate funding, insufficient workforce and unsuitable infrastructure. The report also revealed doctors’ ability to support patients or provide highquality mental healthcare is compromised by a society not designed to support good mental health and wellbeing.

Funding was at the heart of the concerns raised by all of the doctors spoken to. They highlighted how resource

‘Services are widely reported to be overwhelmed by the numbers of people requiring care’

£2.3bn a year in real terms by 2023/24 compared with 2018/19. The National Audit Office’s analysis of available mental health funding data shows that, based on national and local spend, NHS England was on track to meet this target but suggests recent rises in inflation may put the target in jeopardy.

‘The entirety of society seems designed to make people mentally unwell’

constraints are resulting in a system working beyond its limit. They said operating in an environment of scarcity means staff do not have the resources they need, and a lack of funding has wide-ranging effects including insufficient workforce and inadequate estates. It also makes it harder for different parts of the system to work together when there is competition for limited resources.

One consultant psychiatrist said: ‘The quality of the staff hasn’t changed, but the ability to deliver and give time and properly establish a relationship with a patient has really been impacted by lack of funding … I’ve been in the same trust for all these years ... so I’ve seen it change completely.’

The NHS has clear targets for mental health investment and spending, set out most recently in the NHS Long Term Plan for Mental Health (2021). Most notably this included a commitment to increase mental health funding by

The NHS also has a target for local healthcare bodies to increase their annual spend on mental health services at a faster rate than their overall allocation. In addition, there is a commitment that funding for children and young people’s mental health services would grow faster than overall NHS funding and mental health spend. But, in the face of such need, and decades of a lack of focus, these targets are unambitious – and there is a big difference between increased funding and sufficient funding.

One of the psychiatrists interviewed said: ‘More funding applies if it’s £1 more than last year… [There needs to be] capital investment, workforce planning, training and then obviously spending on those staff to keep them employed and on their development.’

A consultant psychiatrist said: ‘I think lack of funding is a major issue. We haven’t had, well I can’t recall, any major investment for a while. Morale is low… I’m fed up. You know, I don’t enjoy my job as much as I used to.’

Perhaps the other most significant area highlighted by doctors in the report is the state of the workforce. Ultimately, it finds, there are just not enough trained staff to meet the needs of people with mental illness.

One psychiatrist said: ‘If

someone is meant to be on the two-to-one [observation ratio] but you’ve not got enough staff, naturally that’s not going to happen … Or if you decide that that needs to happen, it means some of the other patients might not get the observation level they need. You have to make really difficult decisions. With the limited resources we have, who do we prioritise? Who do we look after?’

The data tells a story of high vacancy rates, and low levels of recruitment and retention. Despite overall growth in the mental healthcare workforce, it is not keeping up with demand. Overall, the mental health workforce increased by 22 per cent between 2016-17 and 2021-22. Over the same period, the number of medical staff has increased by 13 per cent and nursing staff by 9 per cent.

Yet, while the workforce is increasing, the number of people in contact with services has increased at a much greater rate. The result is the growth in workforce is insufficient to meet demand.

It is a brutal situation which directly affects doctors and patients. One consultant psychiatrist said: ‘We don’t have any crisis workers after nine o’clock at night. So, if there’s a problem after 9pm, they’re basically on their own. There’s a telephone line you can call, or it’s the police.’

Another said: ‘Historically what I’ve seen was … an issue around nursing recruitment and retention [and] medical recruitment and retention. But now I realise you’re having issues even with psychology and occupational therapy.’

A lack of qualified staff is a particular problem for child and adolescent mental health services. More children and young people are asking for help than ever before, and there are not enough staff to respond to that demand. Since 2016 the number of children and young people in contact with these services has grown at over three-anda-half times the pace of the psychiatry workforce.

The BMA report attempted to be constructive in the face of crisis and also sets out examples of good care and collaboration, as well as tangible recommendations to address the challenges and issues identified.

On funding, it calls for the Government to determine levels of funding and funding targets for mental health services to be based on a full assessment of unmet need to ensure everyone who needs mental health support can access it. It also calls for ringfenced funding to be provided for mental health infrastructure.

On workforce, the report urged a plan to expand the professionally trained mental healthcare workforce – supported by genuine incentives. It also suggests NHS England restore the number of training places for addiction psychiatry within the NHS to improve doctors’ ability to treat patients with substance-abuse issues. The report also calls for clarification on where funding withdrawn from NHS staff mental health and wellbeing hubs is being diverted to.

Away from funding

bma.org.uk/thedoctor

January 2019 – January 2023 (Baseline April 2016)

and workforce, among a host of other areas of concern, a wide range of policy recommendations are suggested including government regulating IT-system supplies to make sure their products are interoperable by default and mental health social care being embedded in the NHS. It also calls for a major expansion of NHS-funded talking therapy training and the collection and publication of national data on ADHD referrals and waiting times.

The report laid bare a mental healthcare system in which doctors are struggling to provide the care they want for patients. They are working in environments which are simply not conducive to supporting people and, while there have been recent focuses on mental health nationally and locally, there has been no overall improvement

in services owing to insufficient funding and workforce among a host of other factors.

Perhaps most troublingly of all, the report paints a stark picture of a society which makes people unwell without the tools to help them when they are. As one psychiatrist said: ‘The entirety of society seems designed to make people mentally unwell … if we had less poverty, if we had nicer workplaces, if we had, you know, housing that wasn’t rubbish.

‘If our social services system worked and supported families where there was abuse or neglect or indeed removed children from those environments and looked after them well. If we didn’t have a society that very heavily promoted body dysmorphia, we wouldn’t have as many eating disorders.’

Read ‘It’s broken’ at bma. org.uk/mentalhealthcare

‘The ability to deliver and establish a relationship with a patient has been impacted by lack of funding’

Doctors welcome the return of devolved government to Northern Ireland but with the health service in such a mess, they question whether it will be up to the task. Jennifer Trueland reports

BRENNAN: ‘Sometimes I’m looking at patients thinking “what’s going to be the least worst thing I can do for you?”’

‘Every day it’s winter. Every day we’re preparing for winter, and every day we’re in crisis mode. When will spring and summer come? The healthcare family in Northern Ireland is so tired – and you really can’t fix that overnight.’

Belfast GP Ursula Brennan sounds despairing. Although she welcomes the return of devolution to Northern Ireland and is hopeful that it might begin to repair some of the long-standing damage to the country’s health and care system, she can’t help but fear it might have come too late.

‘We’ve had no government for two years, so there’s been a hiatus; I get that,’ she says. ‘But the place feels like it’s been on fire. Our roads are in a desperate state, our schools are in a desperate state as well, and health is just the worst I have seen it. I have elderly patients sitting on plastic seats for hours and hours, I don’t want to send patients to A&E because I know their experience is going to be horrific. Sometimes I’m looking at patients thinking “what’s going to be the least worst thing I can do for you”, knowing that it’s not what I want for them in their health and social care journey. It’s really distressing because I don’t know how we can get a lot of this fixed.’

Dr Brennan isn’t alone in her views. The Doctor spent some time in Northern Ireland the week after Stormont started sitting again and heard from doctors from different branches of practice as well as patients and members of the general public. And the consensus was that, while people wanted to be optimistic, grim experience had all but hammered out any possibility of hope.

Patients and their families feel in a terrible position, she says, because they are told there will be long waits for an ambulance, even if they are in pain and in need of care. ‘I’ve had two patients with fractured neck femurs who have been brought in, in a car because they’ve been told it will be some hours before an ambulance gets to them. My friend’s husband had chest pain last week and phoned for an ambulance and was told it would be more than an hour, so she brought him to hospital – he had an infarct and was taken to the cath lab. It’s a dangerous thing to put someone with chest pain into a car, but she felt she had no choice.’

All this has a knock-on effect on healthcare staff.

‘The health service is failing if it hasn’t failed already’

‘Something has to be done about the health service,’ says Siobhan Quinn, an associate specialist who works in the emergency department of Belfast’s Royal Victoria Hospital.

‘I was pleased when I saw signs that the [politicians] were about to come to some sort of agreement, because I thought maybe at least we’ll see some movement, because the health service is failing if it hasn’t failed already. My patients that I see every day at work are suffering because of its failings.’

‘As a doctor, whenever you see how people are treated in the emergency department, you feel bad. You feel sorry for the patients that are treated in such an undignified way. You feel sorry for the loved ones who can’t be with their relatives because of the crowding, and then you start to see the effect it has on yourself as well, because you feel when you’re going into work, you’re not necessarily making the difference that you thought you were going to make.’ She has a very clear wish list for the new health minister Robin Swann and his colleagues. She wants to see more focus on social care, and for care staff to be valued and paid properly to improve flow in and out of hospital.

She also wants measures to retain doctors, including improved pay and, specifically for specialist, associate specialist and specialty doctors, better career progression.

Meanwhile, she and her colleagues are considering options they never thought they would, such as moving to the Republic of Ireland to work, or taking early retirement.

‘I didn’t think I’d be retiring at 60 – I thought I’d go on longer than that, because I like my job,’ says Dr Quinn. ‘But now it’s all about trying to manage the department and manage the crowding. And for the people leaving to go to Australia or Canada or the Republic of Ireland, it’s not all about the money, although it’s a factor. But the waiting lists for treatment are a lot shorter – you can see someone, put them on a waiting list, and know the wait won’t be that long. That must give you a lot more job satisfaction than we have here.’

‘I want to make this work for the people who have paid their taxes ... but we’re failing these people’

Fiona Griffin is a GP trainee working in hospital. Having worked in Scotland before moving back to her native Northern Ireland, she is outraged at how poor terms and conditions are and is determined to drive change. ‘My own experience of being a junior doctor in Aberdeen was very different to what it is here in Northern Ireland, and our circumstances are much worse. In Scotland there are more rota protections, time off after night shift, better protections for working hours, how many long shifts you can do, how many days you can work in a row. These are things we don’t have here.’

she wanted – but doesn’t see why she should. ‘I have commitments to stay in this country, and why should we leave? This is where I grew up, the community that raised me. There’s never a day that I don’t meet someone in the hospital or as a patient that I don’t know from having lived there. Why should I just be expected to clear off? I want to make this work for the people who have paid their taxes and have raised their kids here to be part of the community as well. But that’s not the way it is, and we’re failing these people.’ Since Dr Griffin spoke to The Doctor, junior doctors in Northern Ireland have voted overwhelmingly for industrial action with the first strike having taken place on 6 March (see page 16).

‘I have commitments to stay in this country, and why should we leave? This is where I grew up’

Commitment to full pay restoration for doctors would help retain staff, she says, which would be a good start. But steady, recurrent funding is needed to tackle other long-standing issues, such as long waiting times. Whether the restoration of devolution will make a difference, she doesn’t know. ‘Is a minister going to be able to fix things in one fell swoop? Absolutely not. Do I think the health service is beyond repair? I think it might be. I consider myself an optimist but it’s hard to see optimism when you see how far things have come.’

Like Dr Quinn, she has seen doctors opting to leave Northern Ireland for better pay and work-life balance elsewhere – adding to the strain on already tight rotas. ‘So many of my colleagues have been leaving to go to Australia, or to New Zealand, or to leave medicine altogether within their first two or three years. That’s such a waste.’

She is aware she could move to another country if

Tom Black, chair of BMA Northern Ireland council, is sounding unusually downbeat – even angry – when The Doctor visits him in his practice in the deprived Bogside area of Derry. While having politicians back in Stormont is better than having no politicians, he fears it’s come too late. ‘The health service has collapsed,’ he says bluntly. ‘It’s difficult to get through to a GP even though

Doctors’ optimism dented after meeting with Department of Health

David Farren admits he was hopeful when the news broke that Stormont was sitting once more. But now, after a disappointing first meeting with officials, the chair of the Northern Ireland consultants committee is feeling quite the opposite.

‘If you’d spoken to me before I went to the meeting with the Department of Health, I’d have said actually, I’m quite optimistic. Time and time again at meetings we’d been told that they couldn’t make a decision without a minister; that was the barrier. But now that barrier has been removed because we have got a minister.

‘We went into that meeting thinking one barrier had been removed, but another had been erected.’

‘I hope that now that devolution has been restored that they’ve finally got their act together’

GPs are talking to and seeing more patients than ever. It’s difficult to get an ambulance –there’s a danger now that people are being harmed by poor ambulance response times. We can’t get patients seen by surgeons, when they really need to be seen.

‘We can’t solve the health service in Northern Ireland, not when we’re haemorrhaging staff across the border, not when we don’t have adequate resources. I hope that now [that devolution has been restored], that they’ve finally got their act together, that things become more sensible. But at the moment, everything is broken, and nothing works.’ He comes to the end of his six years as

BMA Northern Ireland chair this summer, and will be handing the baton to someone else. It’s fair to say his successor will have their work cut out, whether Stormont is sitting or not.

bma.org.uk/thedoctor

Officials had previously blamed the fact that Stormont wasn’t sitting for many problems, including the fact that doctors hadn’t yet been paid even the 6 per cent pay uplift recommended by the Review Body on Doctors’ and Dentists’ Remuneration for the current financial year.

Now, he says, officials have told him they don’t know if it can be paid until the next financial year, potentially creating problems with tax and pensions if doctors technically receive two uplifts in one year. Officials also told them that negotiations on pay and conditions could only take place after the conclusion of negotiations in England, despite health being a devolved matter.

Consultants have had enough, he says, and many are voting with their feet. Soon, he might be among them. ‘In an ideal world I would quite happily stay here – I love my job,’ says Dr Farren, a consultant microbiologist with the Northern Health and Social Care Trust. ‘I love what I do for a living, and I will continue to do that job, the question mark is where I will continue to do it.’

He has looked at posts in the Republic of Ireland, he says. ‘I’m left with a choice – do I stay where I am, and take home less money in an under-resourced system where I’m not valued? Or do I slightly increase my commute and apply for a job in the Republic of Ireland where my take-home pay will be twice what I currently receive, I will receive a generous study budget to do things that will further my education and give me more skills, in a system where doctors are valued and the health service is being resourced adequately? It’s very difficult to balance up.’

PEACEFUL ENVIRONMENT: Mr and Mrs Kaye at home

An increasing number of patients are avoiding hospital admissions and long stays through being monitored on ‘virtual wards’ at home.

Ben Ireland finds out how they work

‘It’s been much easier,’ says 79-year-old Stephen Kaye, who has Parkinson’s Disease. ‘I feel more comfortable at home.’

Mr Kaye’s wife and carer Jillian recalls how being told her husband would be able to go home so soon after being admitted to hospital initially gave her ‘the collywobbles’.

He had previously spent 19 days at Watford General Hospital being treated for pneumonia before discharge, and after 10 days at home was readmitted for a fall and urine infection. This time, he was offered early supported discharge on the Hospital at Home pathway –a virtual ward run by CLCH (Central London Community Healthcare NHS Trust).

Mrs Kaye tells The Doctor : ‘I was tearful, I thought there was no way I was going to cope when he’d had a whole team looking after him. I was petrified, I didn’t sleep and couldn’t see how it was going to work. But they said it would be safer at home and they were right. It’s worked brilliantly.’

She describes a ‘mindset change’ and ‘learning curve’ where she gradually became more comfortable with hospital-level care taking place in their home in Hertfordshire.

At home, Mr Kaye – who also has prostate cancer – is more mobile than he was in hospital. He spends less time in bed and has more homecooked meals.

patients to reduce their lengths of stay through safe, early supported discharge. The service is for patients who would otherwise be in acute hospital beds, and typically cares for them for up to two weeks.

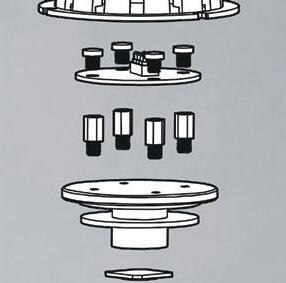

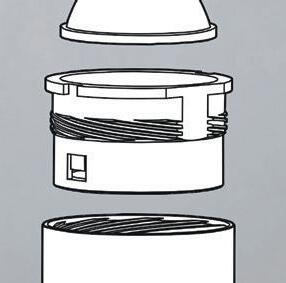

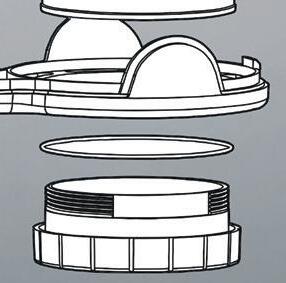

Remote monitoring

Patients, usually older and frail, receive hospital-level care in their homes, enabled by remote monitoring technology including SATS probes worn on the finger and ESG monitors.

Common conditions include COPD, heart failure and dementia. Palliative care can be offered when appropriate.

Patients are cared for by multidisciplinary teams, with either a consultant or GP-level doctor overseeing from a remote hub.

For West Hertfordshire Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, this is based at Watford General Hospital and led by consultant cardiologist Niall Keenan. They work together with the community team from CLCH, led by the trust’s deputy chief medical officer, complex care GP John Rochford. Virtual wards were rolled out widely at the height of the pandemic for COVID patients but have since been adapted to treat more conditions.

‘ The care in hospital was great, but he’s home now’

His observations and interventions are conducted by nurses and physios who make regular visits, and Mrs Kaye is pleased to know extra advice is just a phone call away, and that treatment can be escalated if needs be.

The family is looking ahead to Mr Kaye’s 80th birthday party in November and hope to go on a cruise holiday. ‘Anything is better than being in hospital,’ says Mrs Kaye. ‘The care there was great, but he’s home now.’

The intention of virtual wards is two-fold: to reduce the number of patients admitted to hospital and allow more

Dr Rochford had been aware of an early initiative in Oxford and recalls: ‘What really struck me was the technology that was bubbling up. We saw you can do bloods at the bedside, you can remote monitor more easily, all these things which allow community practitioners to do more with patients at home.

‘Given the pandemic was pushing for people to be managed at home and not come in to hospital, I decided we needed to look at this and train our teams to give them the skills, free up hospital beds and do right by our patients. Barriers that previously existed seemed to go away more easily so we could get things done at pace.’

In Watford, Dr Keenan says ‘circumstances forced

innovation’ as the number of COVID patients began to recede.

‘We thought other patients could benefit,’ he adds, explaining how the team focused on COPD and heart failure patients before expanding into other pathways.

NHS England is keen on the idea, too. Its Long Term Workforce Plan includes an ambition to provide 40-50 virtual ward beds per 100,000 population, which would mean about 25,000 beds in England. An initial target to have 10,000 virtual ward beds before this winter was met ahead of schedule – with more than 240,000 patients treated on virtual wards by October 2023.

NHS Providers head of policy and strategy David Williams says virtual wards are ‘often better for people’s recovery’ and ‘can help relieve pressure on the NHS by freeing up hospital beds for those who need them most’.

That said, he warns they are ‘no magic bullet’ and highlights the need to address workforce shortages and invest in technology to enable the model, with public and staff buy-in also ‘key’.

Doctors at both trusts stress the virtual ward model has been set up to ‘do right by patients’ by reducing the risk of deconditioning or picking up viruses — and is based on evidence which shows better outcomes for older adults whose discharge is not delayed.

Studies have shown that mortality in patients aged 85 and over admitted to hospital with acute illness approaches 50 per cent at one year, five times higher than patients under 60 years of age.

‘Holistic care’

Trusts say patient feedback has been positive, too. ‘Hospital doctors sometimes massively underestimate what it means to a patient to be at home,’ says Dr Keenan.

Ed Hiller, a general medical consultant and GP who works at Watford’s virtual hospital, says virtual wards can offer greater continuity of care than most hospital treatment as they allow clinicians more time to monitor symptoms, signs and medications to gauge how a patient is recovering in what he calls ‘sub-acute care’.

‘A couple of days in hospital doesn’t give the full clinical picture,’ he says. ‘In hospitals, people get labelled as “this condition” – and everyone knows the standard treatment for “that condition” – but there might be more complexity. And they might never know if what they did was successful. Having that wider arc [by monitoring patients virtually] helps avoid readmissions and gives people joined-up holistic care.’

‘There are a lot of natural anchors at home, understanding where they are, how to move around’

Dr Keenan reports ‘huge success’ in early discharges of patients who have, for example, lung cancer and pneumonia, with ‘really moving’ feedback. Through virtual wards, he notes ‘patients say it’s a much softer landing in the community’.

The NHS Confederation records how many beds are ‘filled with patients no longer meeting the criteria to reside in hospital’, with an average of 13,776 such beds a day in the week commencing 5 February and similar numbers throughout winter. The National Audit Office estimates the NHS spends £820m caring for older patients in hospital beds who are no longer in need of acute treatment.

As of January 2024, West Hertfordshire’s acute virtual hospital had cared for about 1,800 patients – with roughly two thirds given early supported discharge and the other third avoiding admittance to hospital.

And up to January, virtual wards at CLCH had supported 3,138 patients; more than three quarters on early supported discharge. According to the trust’s modelling, it had saved 9,136 acute hospital bed days through early supported discharge.

‘Case finders’ are tasked with identifying hospital patients who might benefit from moving on to a virtual ward. Patients, or their next of kin, must consent but Dr Rochford says refusal is rare. He also notes instances of consultants asking the virtual ward team to assess patients who have self-discharged but they would like to keep in. GPs sometimes call with concerns about patients who refuse to go to hospital despite advice to do so, who Dr Rochford says can often be monitored appropriately on a virtual ward which ‘gives them their biggest opportunity to stay at home’.

Dr Hiller says going into hospital ‘can be very upsetting’, especially for a confused patient. He explains: ‘There are a lot of natural anchors at home, understanding where they are, how to move around, keeping their independence. In hospital, they can get upset and delirious. Is that the

best environment for that patient?

Most frail patients do better at home.

They know where everything is, if you take them out of that environment it might be more difficult.’

Dr Rochford says virtual wards offer a ‘wrap-around service’ with hospital-level care and a long-term plan. He notes the ability to escalate is there if needed but says this is rare because of ‘constant conversations’ with hospital consultants who ‘really value’ the service.

and they can check the notes if they get a call.’

A similar collaborative approach is intended with partners in social care too – as some Hospital at Home patients may be living in social care environments. Bridging services can help social care residents being treated on virtual wards, and sometimes virtual ward staff help carers with those patients’ needs.

Part of the nurses’ role is to show patients and carers how the technology works. This is usually done the day before they go home if it is an early supported discharge. Support is always there for questions. If patients don’t have capable smart phones they are given tablets, connected to a phone signal so those without WiFi can still benefit. Patients open an app and attach their monitoring devices which send recordings to the hub, then answer questions about how they are feeling. If this isn’t completed an alert is sent to the hub.

Heart failure and COPD patients receive ‘more techheavy’ treatment, explains Dr Keenan, who emphasises: ‘This is about the patient, not about the tech.’

‘This is about the patient, not about the tech’

In the acute virtual ward, teams are constantly monitoring patients’ vitals. If, for example, oxygen levels become low, the system alerts them.

In that instance, someone calls the patient and a community nurse may visit. They might then need a face-to-face assessment or scan at hospital, which can be arranged on a priority basis, and can be brought in urgently in an emergency – although Dr Keenan says this ‘very seldom’ happens. Patients and carers are urged to deal firstly with the virtual-ward team – which in Watford operates from 8am-6pm seven days a week – but can always call 999, 111 or their out-of-hours GPs. For this reason, some GPs had concerns about how this might affect their already considerable workload when NHS England announced plans to expand virtual ward beds.

Drs Keenan and Hiller say in practice it is rare patients would contact their GPs, as they are in such regular contact with virtual ward teams that it is the natural point of contact. Dr Rochford says GPs find virtual wards ‘reassuring’ despite ‘naturally having concerns’ when they launched.

‘GPs have been crying out for the support to manage these complex patients for years,’ he says. ‘For the first time, there’s an answer. These patients are complex and frail, they need an MDT both short-term and long-term – not just one person.’

The advent of shared care records, Dr Rochford says, makes the process transparent for GPs. ‘The patient is our patient throughout,’ he adds. ‘GPs can see what we’re doing – so we don’t need to bother them with questions,

As many patients are older adults, he says there is always a manual alternative option –with some observations taken over the phone and others from visits.

Dr Rochford says the technology involved ‘is becoming very, very good’ after initial ‘teething issues’.

While the wards themselves are virtual – they still need to be staffed. NHS England’s proposals require recruiting for 8,500 roles, something critics say is difficult in an already acute workforce crisis.

Dr Rochford acknowledges ‘the workforce crisis isn’t going away’ but says surveys show staff empowerment and greater levels of retention in virtual ward teams.

Dr Hiller says that, as an early adopter, the Hertfordshire virtual ward team has been able to ‘build the road in front of us’ and the next challenge is ‘how to expand while keeping it clinically relevant’.

Doctors running the virtual wards agree with Mrs Kaye it takes time for patients to get used to the idea of hospital-level care in their homes. The same goes for doctors.

‘There is a bit of a mentality change about what happens in hospital and what happens outside hospital,’ says Dr Keenan. ‘A lot of doctors feel it’s perfectly fine to have a patient sitting in a hospital bed waiting for a blood test in two days’ time, we feel that is not acceptable.

‘Patients very rarely challenge that, but they should. Why can’t they have that blood test at home in two days’ time? This idea is to try and deliver that for people.’

Years of real-term pay decline and an unsustainable workload mean junior doctors in England, Wales and Northern Ireland are determined to carry on with industrial action.By Tim Tonkin, Seren Boyd and Ben Ireland

Junior doctors in England, Wales and Northern Ireland have stressed their continuing determination to strike for fair pay.

In England, there was a 133-hour walkout last month, which was the 10th round of industrial action.

‘We are united, we have the strength of resolve to get this dispute done’

South Thames BMA regional junior doctors committee chair Daniel Zahedi says: ‘We believe our demands are valid, we’ve had two historic ballots, we’re in the process of getting a third, and I’m confident we’re going to get it. It shows there is this level of discontent amongst

doctors, but also that we are still united, we still have this strength of resolve to get this dispute done.’

The latest strike action in England came after the Department of Health and Social Care failed to meet an 8 February deadline of presenting a revised offer on pay to the BMA.

While the BMA junior doctors committee offered to suspend the strikes in exchange for a four-week extension of the mandate for industrial action by health secretary Victoria Atkins, the absence of such a

commitment left thousands of doctors in England with no alternative.

As well as attending the picket at St Thomas’, one of three super picket lines in England along with those in Manchester and Birmingham, foundation year 2 Callum Parr was one of many junior doctors who used the period of industrial action to donate blood for the first time.

‘I know many colleagues who’ve gone and done it for the very first time and each time you donate blood it can save up to three lives so it’s a great initiative.’

BMA junior doctors committee deputy co-chair Sumi Manirajan says the continued support of patients was something she and her colleagues valued deeply, and did not take for granted.

‘We want the public to be with us on this because we’re doing this ultimately so they get better care, and we get better doctors in the NHS,’ she says.

Junior doctors on a 72-hour strike in Wales last month spoke of a profound sense of hurt and frustration that the pay offer made to them by their government was lower than in any other part of the UK.

Speaking at a demonstration outside University Hospital of Wales in Cardiff, foundation year 1 Imogen Potter said: ‘The Welsh nation is already more poorly funded than other nations, and the incentive to stay is now less.’

Specialty trainee 2 Rachel Kerr was concerned that retention across all sectors of the health service would not improve until pay rose. She said junior doctors deserved pay restoration to 2008 levels not least because of the considerable responsibilities they shouldered and the emotional toll of the work.

‘We’ve got an everincreasing workload, we’ve got an ageing population, and there’s just less and less of us,’ said Dr Kerr. ‘When you’re on call on a weekend or overnight, and there’s just you and you’re covering multiple wards, it’s a lot. We have people’s lives in our hands.’

BMA Welsh junior doctors committee co-chair Oba Babs-

Osibodu says junior doctors in Wales had ‘absolutely no choice’ but to strike until a ‘credible’ new pay offer is made.

‘I’d much rather be in work,’ says Dr BabsOsibodu. ‘But that feeling is dwarfed by the gargantuan pay cuts that we’ve received and the ridiculous levels of burnout that we’re seeing. And I’ve seen the impact that this is having on patients; chronic understaffing means we’re not able to deliver the care we want to.’

They didn’t go on strike. That represents an effective relationship with their devolved government.’

He says doctors are being drawn to better-paid roles in the Republic of Ireland.

In Northern Ireland, doctors staged their first strike of the campaign as they walked out for 24 hours earlier this month.

BMA junior doctors committee chair Fiona Griffin says: ‘We had to get the ball rolling. At some stage someone had to listen to us. We couldn’t leave it until our pay had eroded by 50 per cent.’

Junior doctors in Northern Ireland have been told that the devolved government is unable to act until an agreement is reached in England – even though health is a devolved issue.

Marcus Hollyer, an internal medicine trainee 2 demonstrating with colleagues outside Belfast’s Royal Victoria Hospital, cast doubt on the logic of the devolved government’s position.

He says: ‘Scotland were able to negotiate an offer that their members accepted.

‘A lot of people live here and work over the border,’ he says. ‘They also have challenges with their working conditions, but they are significantly better remunerated for that work.’

In Northern Ireland, GMC survey results found 49 per cent of trainees reported working above their rostered hours –higher than the UK average of 42 per cent – and a higher proportion (38 per cent) reported rota gaps than in the UK (28 per cent).

Foundation year 1 Ross Brown said: ‘It’s hard enough to recruit to Northern Ireland anyway, and the low pay makes it even worse.

‘Rota gaps have become permanent gaps. There’s a permanent staffing shortage, it’s the new normal. If someone else is off sick, you are left doing the work of two doctors. It’s not sustainable, and more and more people are leaving. We don’t feel like we’re giving the care we want to give.’

‘Chronic understaffing means we’re not able to deliver the care we want to’

Serious concerns about her own wellbeing led GP Katharine Jones to come to an important realisation. She tells Jennifer Trueland how she has embraced lifestyle medicine, encouraging patients to take responsibility for improving their health

When Katharine Jones decided to go back into general practice after a spell in medical leadership, she was aware it might involve a bit of adjustment.

However, she was surprised – and dismayed – to find her new job (as a salaried GP in a practice on the Isle of Skye) was much, much harder than anticipated.

When she discovered her own health – specifically the menopause – was a major contributor to this feeling, it inspired her to focus on the wider wellbeing needs of other doctors. It also led to a significant change in her approach as a GP.

‘I really struggled getting back into general practice – I thought I was just getting used to it again,’ says Dr Jones, who is now a salaried doctor in a practice in Alness in the Scottish Highlands. ‘But after about two years, I realised I was having significant problems with processing and memory and decision-making, to the point that I felt I was borderline fit for practising.

‘And as a doctor, what do you do? Do you go to occupational health, do you go to your own GP? You’re scared to be honest, because you don’t know what’s happening to you.’

At this stage Dr Jones was in her early 40s, but feared she was developing dementia. She found everyday tasks at home almost beyond her: packing for a holiday became extremely stressful and she had notes and timers all over the house to remind her of what she should have been doing.

Several things contributed to her growing understanding of what was happening to her. Firstly, she had some coaching that started to restore her confidence, which in turn led to her taking up running. Then she heard an educational talk from a menopause expert who said the brain needs oestrogen. ‘As soon as she said that, I thought “that’s what’s wrong with me”. I started taking HRT and it’s been absolutely incredible for me – particularly, I think because I had that period of feeling like I was never going to be able to do anything again with my brain. It was the springboard to me embracing learning, I’ve started my own company, I’ve done some training in coaching and qualified as an accredited lifestyle medicine physician. It’s been the total joy of knowing I don’t have pre-senile dementia, that I have a useful purpose.’

She wishes doctors had more information and understanding about the menopause – and includes herself in that. ‘I think now of all the women I’ve seen over the years, and I’m sure there are numerous times that I’ve started talking about antidepressants or counselling, or arranged tests that maybe weren’t necessary, because I didn’t understand how the menopause could present,’ she says. ‘I feel quite guilty about that.’

Dr Jones’ own experiences made her rethink the way she practised as a GP – and she believes her approach has wider lessons for the profession. Too many doctors think of themselves as ‘rescuers’, responsible for solving all the problems of patients, she says. But this leaves

WADE

doctors exhausted and burnt out and doesn’t do patients any favours either.

‘The problem with this dynamic is that rescuers think they’re being really good people, going above and beyond, taking on extra shifts, and doing things for the patients that they could be doing themselves. But what they’re actually doing is holding the patient in the “victim” or “helpless” mode,’ she says.

This dynamic might work in a scenario where a patient comes in with an infection or injury that is fixable, she says, leaving clinician and patient happy with the outcome.

But she adds: ‘The problem we’ve got now, particularly in primary care, is that in 80 per cent of consultations, the patients are coming in with problems that aren’t fixable in that way. They’re caused by lifestyle, and the patient can only fix that themselves. But they come in expecting the clinician to fix it, and the clinicians expect to fix them, because they’ve done years of training, they’re altruistic, and they’ve been driven into this role to help people. This means you get huge frustration in the system because the clinician is trying to “fix” the patient, but it doesn’t work.’

She has found that by incorporating the principles of lifestyle medicine in her practice and moving from being ‘rescuer’ to ‘coach’ – encouraging patients to take responsibility for their own wellbeing, is flipping that dynamic to create a much healthier relationship. This includes using techniques such as motivational interviewing – where the patient is encouraged to come up with and implement their own solutions, with guidance – but also by prescribing activities which are good for wellbeing, such as saunas and exercise classes.

‘Using this approach has been transformative. I’m not saying it works for everyone, but I’ve had people saying they’ve been waiting for this consultation for years. And, as a GP, it literally feels like you’re releasing people from a cage of perceived reliance on the health service, where they are waiting for an appointment, waiting for a

diagnosis, waiting for the drugs to kick in. Instead, you’re giving them the tools to make the change themselves.’

She agreed to take on her NHS role as a GP at the practice in Alness only if she could integrate lifestyle medicine into her consultations. The health board agreed (presumably at least in part because of the difficulty of recruiting GPs to rural general practice) and this means she has extended consultations for patients with complex physical, mental and emotional problems. She also is working on a project to assess the effect of this approach.

The practice is also introducing group consultations for people with long-term conditions to encourage peer support and have access to community link workers who can take a holistic view of people’s needs and direct them to available help.

At the same time, she continues to develop her business, called Wild-Ness Spa & Retreat, which runs courses for the general public and local community, on topics including navigating the menopause and the benefits of ‘wild’ activities, including cold-water swimming. But it also has retreats solely for health professionals, promoting the benefits of a lifestyle medicine approach. This is important to her, because clinician wellness has always been an interest of hers, even before she had her own health problems.

‘What’s happening is that my business and my NHS work are tracking along in parallel – what I’m learning from the business, I’m using in the NHS work, and what I’m learning from the NHS work in terms of delivering this approach to people in the practice – and I most actively seek out the most complex patients – I’m applying to the business.’

It has also transformed her own attitude to her role as a GP, she says, and reignited her enthusiasm for the job.

‘It’s been really amazing – it’s a cliché, but it’s really been an amazing journey.’

See more information – including details of forthcoming events – at www.wild-ness.co.uk

The Government’s imposition of minimum service levels during strikes could lead to chaos, and harm patient safety, argues BMA deputy council chair Emma Runswick

The Government is continuing to blame striking doctors for its own failure to bring down waiting lists and address patientsafety concerns, as it attempts to justify its latest anti-strike legislation.

‘The BMA will continue to campaign against the proposals and for the act to be repealed in its entirety’

The NHS is collapsing around us and the idea that imposing MSLs (minimum service levels) on strike days will solve this makes little sense.

Although the Conservative Government first introduced a commitment to MSLs for railways in its 2017 manifesto, it was only after a wave of strikes that the Government sought to expand this to include many other parts of the public sector including education, border security, and hospital services. It represents another layer of British anti-union law, already some of the most restrictive in the Western world, and mostly applies to non-emergency services.

The BMA has opposed the Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Act at every opportunity. We have serious concerns about the safety of the MSL proposals, the shift of clinical control away from doctors, and the effect on our ability to take effective industrial action.

The exemplary work of medical managers and senior medical colleagues across the country in keeping urgent, emergency and critical care safe during strike action demonstrates an incredible commitment to patients. Crucial to this are local knowledge, good working relationships, advanced planning and the rate card. When we take strike action, care continues – but you and colleagues serving as clinical or medical directors discuss what is safe and what can wait according to clinical priorities.

Under the MSL regulations, the decision about what care is essential, and therefore who is needed, will be removed from you as doctors and clinical managers, and placed with politicians. While regulations were not released at time of writing, initial proposals suggest they will seek to continue all priority 2 work, which can include non-urgent surgery. Elective surgical care requires cover from various specialties (eg ICU, radiology) to be completed safely. Employers will be able to issue work notices to all the doctors required to keep that service running, with

DANIELS:

‘It’s about understanding doctors’ perspective and appreciating their problems are between them and the Government’

threats against you (dismissal) and your union (financial and legal) to enforce compliance. The BMA will be legally required to tell you to cross picket lines. The intended effect is to make it impossible to win better pay and conditions.

We in the BMA do not believe that employers, particularly lead employers for ‘junior’ doctors, have the local knowledge or administrative support to meet the requirements of the legislation – consulting unions and producing work notices in just a week – and maintain patient safety.

Hospitals already struggle to provide correct rotas, cover known absence, and pay colleagues correctly. Some derogation requests have included wildly incorrect information. Trying to implement the legislation without the top of the organisation readily having the necessary information available means the possibility of chaos undermining patient safety is significant.

Campaign continues

The NHS will likely request we hobble our own industrial action through voluntary arrangements, and there will be Government pressure on chief executives to use the legislation. Employers may face a set of options: decline use, attempt to prevent the vast majority of doctors taking strike action, or force doctors and patients into dangerous conditions.

The BMA will continue to campaign against the proposals and for the act to be repealed in its entirety. In the meantime, we all need to engage with and learn from our colleagues across the trade union movement dealing with anti-union legislation. The next issue of The Doctor will look at some strategies from other groups of workers.

You as our members, those striking and those planning safe care during strikes, can lead our strategy through local organising, local negotiating committees and conference motions. Please keep an eye out for further updates and suggestions on how you can help. Email me at depcouncilchair@bma.org.uk

Strikes have taken place safely without the need for draconian legislation. A medical director tells Tim Tonkin good communication is essential

The challenges around maintaining safe levels of staffing during periods of industrial action are something consultant paediatrician Justin Daniels has become well versed in.

Following his appointment as medical director at East and North Hertfordshire NHS Trust in April 2023, Dr Daniels has had to navigate and help oversee his trust’s response to numerous bouts of strike action and, in his words, frequently relying on the ‘expertise and goodwill’ of those around him.

Almost one year into his post, he says he has learnt that successfully negotiating strike days consists of several factors including clear and honest communication, good forward planning and maintaining good relationships between different groups within the trust.

‘From my perspective [managing strike days] revolves around lots of things. It is around really good communications between junior doctors’ local negotiating committee and me,’ says Dr Daniels. ‘It’s about knowing what’s going on with them and understanding their [doctors’] perspective and appreciating that their problems are between them and the Government.

‘Something that I’ve said really, really clearly is that this [dispute] is a BMA versus government not an individual doctor versus their trust,’ explains Dr Daniels.

‘That’s been in all of our communications, and also in all of the inductions that we do. I think that for the most part, doctors have been incredibly grateful that we’ve managed to retain really good relationships, and that this hasn’t become personalised and it hasn’t become more difficult than it needed to be.’

Dr Daniels says that, in addition to good communication, taking a proactive approach to rotas ahead of periods of planned industrial action and the co-operation of wider medical workforce are crucial to ensuring that disruption to services is minimised.

‘I think most trusts have tried hard with the communications and most trusts have tried incredibly hard to ensure that there is safe staffing all the way through this. I think because of the way some organisations are configured, it’s harder in some organisations than others,’ he explains.

‘We’ve got a fabulous operations department at East and North Herts, and they’ve worked really, really hard before each strike to make sure every single rota is covered safely. We are [also] quite lucky in that we have a relatively low vacancy rate amongst our consultant body and that gives us a little bit more flexibility [on strike days].

‘I know the consultants in the trust support the junior doctors and therefore want to make this safe to happen [and they] therefore are prepared to work hard, and we all have been in order to make it happen.’

We should always remember to be respectful when exchanging views

I’ve always been keen for this column to be as responsive and engaging as possible. In recent weeks I’ve seen discussions on social media – and had direct messages about – a couple of themes, which I thought merited response and discussion.

For those who like to get straight to the punchline, I can more or less sum up what I want to say with four words: Get involved. Be respectful. These two things I want to discuss are recent comments from doctors who say they don’t understand how the BMA and the structures of our association work and a number of less-than-respectful engagements and interactions between members and representatives across various platforms. These issues clearly have a relationship, too, because we desperately want members to get involved – as many of you as possible – in the many areas of the BMA, but I must also encourage everyone who does so to be respectful through the process of standing for democratic elections and becoming a representative.

The BMA does try to explain its functions and structure – we send members a great deal of messages and content through emails, texts, social media including Facebook, X, Instagram and through other mediums such as this magazine. But, in the busy world most of us work in it isn’t always easy to engage and I do understand that. However, I would really like to encourage you to make this a twoway street and engage with what we send and learn about your union so it remains representative of you.

The BMA has networks all the way from national

is accountable to members and tries to ensure that policy is followed at all times. And each branch of practice – the professional area you work in – has its own national committee whether that is for general practice, public health doctors or SAS doctors, for example.

More locally, we have regional committees for each area of professional practice. So, for example, in my patch there is a North West regional SAS committee which feeds into the national committee. All branches of practice have those. There are also regional councils and divisions which aren’t for doctors from specific branches of practice but represent members from all backgrounds locally. So, returning to my patch, we have a North West regional council and several divisions, such as Manchester and Salford, for example. Beyond those structures there are also local negotiating committees in hospitals.

We also have the representative body and the annual representative meeting. The RB are the representatives who attend ARM and make policy on behalf of members. This group of people is formed mainly from divisions and branch-of-practice conferences. Recently, changes have been made to divisional elections to bring them in line with the rest of the association by utilising electronic nomination forms and voting systems. Previously, only

people at particular divisional meetings could vote for candidates and clearly not everyone is able to be at every meeting. Now, all people represented in a division will be able to vote.

As your RB chair, I remain neutral and have no authority in this change. This change was voted by BMA council as advised by the organisation committee. I do have an interest though. The BMA is under representing women, ethnic-minority colleagues, disabled colleagues and LGBTQ+ colleagues. I am interested to see if these steps will increase the diversity of representation and, using the demographic data we can collect, we will monitor the effect these changes make.

There have been a number of derogatory comments on social media about members and representatives, recently. Criticisms of the BMA include suggestions that we are undemocratic or not representative and accusations that the association hasn’t followed the paths or taken the decisions some commentators would like.

Some of these discussions haven’t been held in the most respectful of manners and I would like to remind all members that this isn’t OK. More than that, I would like to remind everyone the BMA is its members. It can only be guided and led by those members and the people who stand to be representatives. The people who have guided this association have done so as elected representatives and have driven policy voted by representatives of members. I was elected into my first role as deputy chair of RB in 2019. I stood on a mandate to make certain changes and I have helped to achieve many of those. That’s how you influence the change you want to see.

Our colleagues who have been in elected roles in the BMA have similarly done their best to represent the membership. They will have dedicated time and effort into their roles and many will have influenced our policy driven actions over the years.

If you want to see change, if you want to be heard, stand for election. It is unfair for those who haven’t tried to make a difference to criticise those who have. It is unfair for the starting position to be an assumption that previous members have done anything less than their best and in the best interest of our members.

I’d also like to remind members – and it’s unfortunate that I have to say this – there is no place in our BMA for any form of discrimination.

If you would like to get in touch to share your ideas or views please write to me at RBChair@bma.org.uk

Dimmer wheel allows you to adjust the light output. Standby switch and ergonomic handle helps you direct light beam precisely where you need it.

Light Engine simulated high definition natural light. Guaranteed

O ering crystal clear clarity and incredible colour rendition, a Serious Light is perfect for anyone who struggles to read small print for any length of time or who needs to see ne detail. It will transform your visual experience.

For Advice. For a Brochure. To Order: 0800 085 1088 seriousreaders.com/8983 2024 Trusted Platinum Merchant 4.9/5 (10,358 Reviews) SAVE £100 when buying any HD Light. Quote o er code 8983 at checkout or when calling. While stocks last. Plus FREE Delivery worth £12.95 available at checkout HD Floor Light Was £399.99 Now £299.99 HD Table Light Was £349.99 Now £249.99

That’s how often someone is admitted to hospital with an acquired brain injury (ABI) in the UK.*

An ABI can cause lasting disability and feelings of grief, anger and isolation. You can help us be there for the survivors of ABI today. We offer 24/7 care and rehabilitation for ABI survivors, as well as support for their families.

Yes! I’d like to support a disabled person at the Royal Hospital for Neuro-disability today. I enclose a cheque/postal order (payable to RHN) for: £20 £50 £100 My own donation of £ or please debit my VISA / MasterCard / Delta / Maestro / Charity Card.

Card No

Start Date M M Y Y Expiry Date M M Y Y Issue No.

Name:

Address:

Postcode:

Email:

Phone:

Signature:

We will send you mailings occasionally when we feel they may be of interest or you may be able to help. You can change the way we contact you at any time by speaking to our friendly fundraising team on 020 8780 4568, emailing them at fundraising@rhn.org.uk or writing to them at RHN, FREEPOST, West Hill, Putney, London, SW15 3SW.

For further information, and to find out how the RHN looks after your personal data see our supporter privacy notice at www.rhn.org.uk/help/privacy PressAdMar24TD

Please send this donation form to: Freepost RTKU-TLTC-JUCK, Royal Hospital for Neuro-disability, West Hill, London, SW15 3SW