The Canadian Jewish News

Luxury • Culture • Activities • Connections

Move into our well-appointed, pet-friendly condominium rental suites and enter the world of purposeful living at Two Neptune Drive. This is senior independent living at its best: a thriving active community, deluxe amenities and exciting social activities all with Covid-19 protocols in place.

Flex your muscles in our renovated fitness centre, find a quiet reading nook in our extensive library or join friends in our large social for rousing games, stimulating conversation, movies, thoughtprovoking lectures and more! Life on your terms with conveniences, peace of mind and security.

Explore the possibilities. We’d love to show you around. Book your tour today and ask about our move-in incentives.

Contact Laurie Banks at LBanks@Baycrest.org or 416-785-2500 ext. 2270

TwoNeptune.ca

The Time to Thrive is Now so Come and Explore . . .

The Newly Renovated Baycrest Terraces

Offering Independent Living with Supportive Services, Assisted Living and Memory Care, utilizing the Possibilities by Baycrest TM model.

We offer unmatched health care, social activities, and cultural programs that enhance the physical, cognitive, emotional, and spiritual health of our residents.

Book your tour today. We would love to hear from you!

Contact Reesa Soto at RSoto@Baycrest.org or 416-785-2500 ext. 2263

BaycrestTerraces.com

As we gather with family and loved ones around the Seder table to celebrate the unparalleled strength of our community, we want to thank you for your enduring support.

57 Esther Gelcer’s hagaddah illustrations

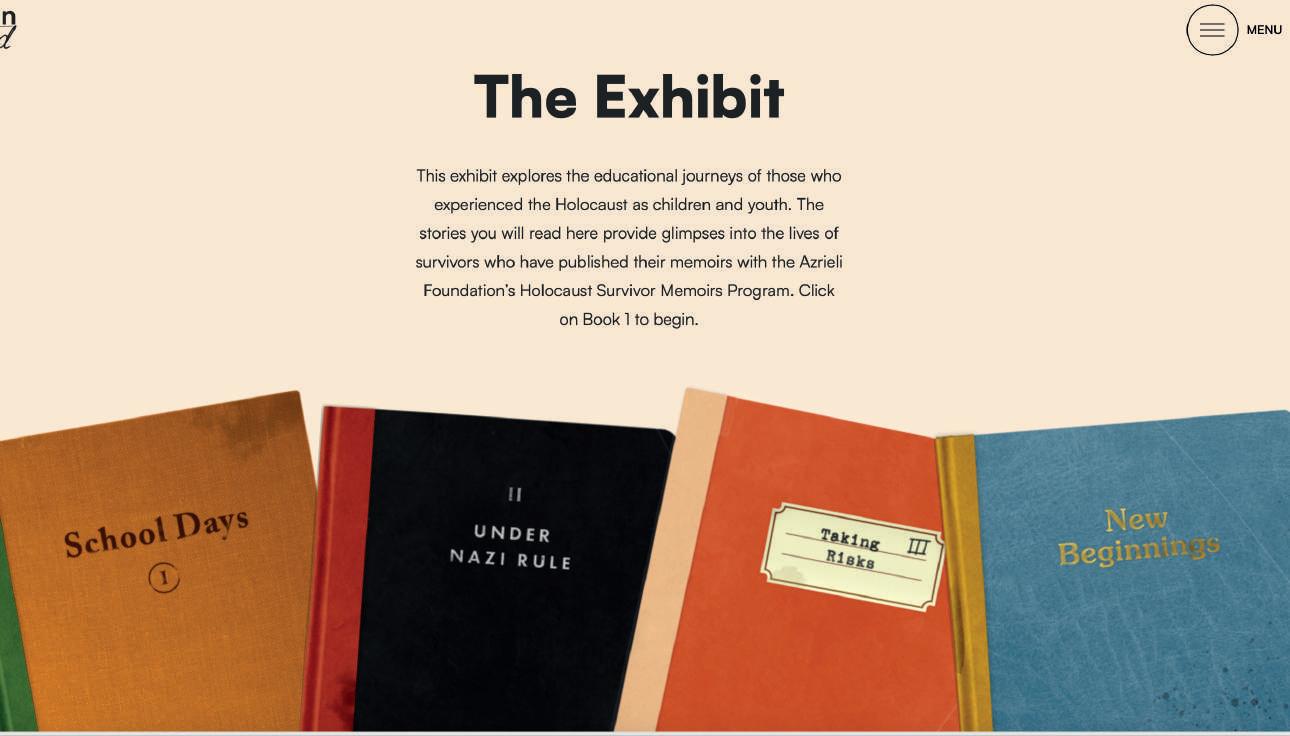

65 She’s a Mensch!: Judy Feld Carr and Rosalie Silberman Abella

ANNE DUBLIN

70 The Hagaddah Collective’s development of Dippin’ Dabbers

Esther Gelcer is a registered clinical psychologist, currently in private practice in Toronto. She is the author of many articles on family therapy, training and supervision of professionals and students, gifted children and bereavement and loss. Her hagaddah illustration is featured on the cover of this magazine.

Eva Mroczek is the incoming Simon and Riva Spatz Chair in Jewish Studies in the Department of Classics at Dalhousie University, Halifax. The author of the award-winning book The Literary Imagination in Jewish Antiquity, she currently directs the Jewish Studies program at the University of California, Davis.

Philip Slayton is a Canadian lawyer and writer. He is the best-selling author of Lawyers Gone Bad: Money, Sex and Madness in Canada’s Legal Profession, Mighty Judgment: How the Supreme Court of Canada Runs Your Life, and Mayors Gone Bad among other books. A Rhodes Scholar, he has been a Woodrow Wilson Fellow and President of PEN Canada.

Marc Weisblott

Managing EditorPhoebe Maltz Bovy Senior

EditorRonit Novak Art Director

Etery Podolsky Designer

Sarah Zahavi Design Associate

Lila Sarick News Editor

Michael Fraiman Podcast Director

Grace Zweig

Sales Director

Kathy Meitz General Manager

Board of Directors:

Bryan Borzykowski President

Sam Reitman Treasurer and Secretary

Ira Gluskin

Mark Sherman

Jacob Smolack

Elizabeth Wolfe

Ofall the iconic Jewish images evoked annually by the Passover haggadah, the parting of the Red Sea sticks with me most. The 10 plagues, the burning bush, even the Egyptian exodus were prophesized and enacted, we read, from high above. There wasn’t much for the Jewish nation to do but go along with the plan, and eventually get ready to leave for the promised land.

When they got to the sea, with Pharaoh’s army in hot pursuit, it was the people themselves who had to initiate the next chapter. Most understandably hesitated to dip their toes in. But that’s when—according to the Talmud—a Judean prince named Nachshon ben Aminadav stepped forward and walked right into the water. Seeing this, God ordered Moses to plunge his staff into the sea, which then parted… and you know the rest.

You might call Nachshon’s actions a leap of faith, but to me they signify something else.

Trust is fundamental to the success of any community, and of course to society in general, but it has been eroded in recent years by a variety of forces, some well-meaning and many that are more insidious in nature. The ongoing efforts by political, social and religious leaders to target and blame the media are mostly misplaced. Journalism outlets, beset by cutbacks in the digital age, haven’t inspired confidence with reporting that’s shoddy and slanted. On top of it all,

social media has guttered any meaningful conversation or exchange of ideas, while spreading misinformation more quickly and widely than verifiable facts.

That’s why we rebuilt The Canadian Jewish News the way we did. We wanted to prove that The CJN is different by investing in stories that speak to you. We’ve built a roster of Jewish personalities you can trust, because they are just like you in many ways.

We believe that our community—and every community, for that matter—requires and deserves no less. Without reliable and dependable media, trust can wane, and we know where that road leads better than most.

If you agree, the good news is that you can help by investing in media you can trust. As the growth of The CJN continues in 2023, we’re accepting charitable donations through the Canada Revenue Agency. Your monthly contribution will help us continue our vital work of rebuilding in a sustainable manner. We’ll make sure you keep receiving our print magazines along with yearly tax receipts.

For more information, check out thecjn.ca/support or write to support@thecjn.ca, and you’ll be investing in something we can all place a little faith in, for this Passover and beyond.

— Yoni Goldstein

If you’re reading these words, you probably fit into one of two categories: You’ve been preparing a family seder for the past few weeks—and it’s been your pride and joy to do it for decades— or you’ve been handed this magazine by a parent or grandparent who invites you for Passover like clockwork, every single year.And now, I’m here to inform you that these routines need to stop.

Look, I get it. Bubbe’s brisket. Saba’s boisterous singing. Cousin Ronnie who’s in rabbinical school and insists on

explicating things in detail next to Aunt Sylvia—an atheist who only shows up every year because “it’s a tradition.”

Reading from the wine-stained haggadahs prompt the familiar rituals of hiding the afikoman, and spark arguments over who needs to read the paragraph about the wicked child—or maybe a debate about how the patriarchy is to blame for the 10th century text specifying it’s a son.

It’s all part of the annual evenings where we get together and reenact the

Exodus in our own unique ways.

But something happens when grandma and grandpa always host the seder: Jewish life and ritual become synonymous with them, and only them.

Yes, many of you still live robust Jewish lives independent of those older family ties. But too many Canadians who fall between graduation and retirement have never hosted a seder—and a lot of them have offspring destined to follow in their footsteps.

You know what that leads to? A weekly

Shabbat dinner also becomes something that only exists elsewhere, whether it’s done by parents or grandparents or hosted by a synagogue. And you know what that leads to? A lack of ownership of one’s own Judaism—and the inability to initiate doing Jewish.

If you’re a seder host, think back to when you first took the lead, and why it ended up happening. Likely, it was one of several steps toward being an adult, approached with the typical combination of trepidation and pride.

As time passed and you began to do it more often, your confidence grew. You were able to add bits and pieces to the rituals and augment your immediate family with a guest or two.

And yet, while the seders have grown and become legendary family lore, your offspring haven’t experienced the opportunity you seized long ago.

What becomes of those lively seders in the long run? Some will do a better job with the brisket. And the singing may get better, too. But the familial associations might also fade away forever.

Now, speaking as the rabbi in the room at The Canadian Jewish News— where I host the Bonjour Chai podcast each week— I’m here to tell you there’s an easy fix for this. Stop inviting them.

I know this is much easier said than done, to the point where your objections are at least partially right. Good thing our diaspora Jewish traditions have a solution for that.

Welcome them for one seder. Bring everyone together. Make it the best you’ve ever had.

And then cut them loose for night two.

It isn’t easy—but maybe it shouldn’t be. Maybe the best things in life involve hard work. Maybe you’ll help them a bit… send them some sides… a bagful of extra haggadahs… assist them with a bit of bubbesitting so that they can get on with the prep. Maybe you won’t give these grown kids any help at all.

Now, for all of you who

I’m pushing to walk into the Red Sea without any assurance of parting waters, let me give you some help. It’s not all that hard.

You may have never hosted a seder before, but if you’ve attended a few then you have a pretty good idea of how they go. I’ve learned about a saying from medical school: Watch One, Do One, Teach One. The best way to learn is to just make it happen. The next step after that is inspiring somebody else.

Besides, the hagaddah is quite literally the instruction manual for running every seder. Go buy one that looks interesting. Heck, get four different ones and pick out the parts you like. There’s nothing sacreligious about switching between editions or tuning out the bits that don’t do much for you. (The seders you’ve been going to have probably been skipping more than anybody is willing to admit.)

One of the most moving lines of the night is found at the start, when we extend an invitation to all who are hungry to come and eat—which can prove a delicious deal when you’re on the receiving end. But we can’t understand the dynamics of hosting when we’re always the guest.

If you’re a serial attendee of somebody else’s seder—and you’ve read this far without turning the page—I’m here to tell you that you’ve got this. A few tips are enough to make you feel like you’ve been doing it forever.

Go forth, lead with confidence, and get accustomed to inviting the older family members who spent all these years inviting you. They’ve earned the right to kvell a little bit. n

Now, for all of you who think I’m pushing to walk into the Red Sea without an assurance of parting waters, let me give you some help. It’s not all that hard.

Focus on your audience and tailor it to them

Will the guests be family members who’ve done the same thing for years? Try changing-up their customs and expectations—but don’t take it too far. Or will it be a “friendseder” with everyone coming together for the first time? You know what they’re into and their tolerance for communal singing, so plan accordingly. Don’t expect people to young kids to be attentive into the night. Create something light but full of active participation by all.

Recognize that there are very few essential parts

The Four Questions. The 10 Plagues. The afikoman. Whatever they happen to be, find the parts that are important to you and your audience and focus on those. Do some research into their meaning and history and find creative ways to present them. As for the rest of the haggadah? You can skim some, you can skip some, but make sure to straddle the line between treating the seder as a big event and treating it as a boring prelude to the food.

You don’t need to have an elaborate seder meal

Focus on dishes you know well and can make without a sous chef and three interns. Maybe add one dish that wows the crowd. Elevate the karpas from a sad sprig of greens to a full-on spread—anything that can be dipped to fulfill a blessing is fair game: Crudites and Bagna Cauda? Chips and salsa? Strawberries and balsamic glaze? All will be welcomed and get you into the hagaddah with so few complaints that people won’t be hungry along the way.

Any wineglass is fine for Kiddush or Elijah’s Cup. No special plate is required for symbolic foods. Get creative for the ritual items and you’ll be surprised how they end up cherished. (And if they don’t on the first try—then just buy one new thing a year going forward.) A good rule of thumb is to mix heirloom items with modern ones, get one from a friend or make an item rather than buying. Something old, something new, something borrowed, something glued.

Bonjour Chai continues its annual tradition of asking prominent Canadians to share their thoughts about Passover. Join us at the podcast table for a supersized April episode designed to get you in the holiday spirit—or to keep you tuned in during the week. thecjn.ca/seder

Saul Fenster and his older brother, Henry—two siblings from Poland who had survived the Holocaust—bought a swampy plot of land an hour north of Montreal in 1961. And so, the Belle Neige ski hill in the Laurentien mountains was born. Saul had learned to ski after the war, in Switzerland, where he had been sent to try and cure his tuberculosis after the pair survived a half-dozen death camps. A 25, which

Lev Goldfarb may not realize it, but this event was good for the Jews. Not only did he spark a whole lot of goodwill in the tiny Lake Ontario resort town between Toronto and Kingston—now the Metro store manager has promised to start stocking some kosher food items for the community of about 100 people. Lev’s fascination with the supermarket prompted his mother, Hadas Brajtman, to approach the managers with an unlikely request. The result was beyond the Israeli expatriate family’s wildest dreams.

Hanina “Hank” Hoffman originally didn’t want to accept the offer to write a macabre flick with a Jewish theme. But he changed his mind once he realized he could help change the way Hasidic Jews are so often portrayed on screen. The resulting film is called The Devil’s Offering. Hoffman channeled his upbringing in Toronto as the son of a former ritual director at Adath Israel Congregation, who held his own teenaged job at a shomer who sat with the recently deceased at Benajmin’s Park Memorial Chapel.

The popular Montreal comedy duo of Jamie Elman and Eli Batalion is betting that they’d have worldwide appeal if what they’re saying in Yiddish was more widely understood. That’s why a 2015 video explaining why some Jews eat Chinese food on Christmas Eve has been translated… into Mandarin. The revamped video premiered on a social media platform in China around the same time that Radio-Canada’s streaming service brought YidLife to francophone audiences with subtitled episodes like “Le schmaltz.”

While conspiracy theories abound over who did it and why, interest heated up this winter as two major Canadian news outlets gave the story the true-crime audio treatment, although the two shows took very different approaches. Toronto Star investigative journalist Kevin Donovan brought five years of reporting to The Billionaire Murders around the same time Kathleen Goldhar unveiled The No Good, Terribly Kind, Wonderful Lives of Barry and Honey Sherman, a podcast production being distributed through the CBC.

Ronen Hoffman announced on Jan. 21, just over a year after he moved to Ottawa, that he plans to leave his post this summer due to “the transition to the new government and to different policy in Israel.” The political shift was also covered this winter in interviews with former McGill University law student Dan Illouz, who’s now a member of the ruling Likud government, expressing his support for court reform—while Canadian philanthropist Charles Bronfman talked about signing an open letter in opposition to it.

Irvin Studin used to be a professional soccer player, and the policy expert, academic and think-tank head likes sporting terminology. Which means, in the aftermath of the pandemic, this nation needs to win the next game. He shares 10 theses for our survival between the covers of Canada Must Think for Itself

While credited with saving the lives of 200,000 Hungarian Jews, the killing of more than a million victims at Auschwitz haunted him until his death in Vancouver in 2006. The Escape Artist, a new book by British journalist Jonathan Freedland, makes the case for Vrba being one of the greatest Holocaust heroes.

Word that the Aroma Espresso Bar’s only kosher location in Canada was closing prompted The CJN Daily to kick off 2023 with a visit to the Toronto intersection of Bathurst and Wilson to find out why.

The letters on the sign had already been taken down, while a moving truck was parked outside as appliances and other fixtures were being removed.

After seven years, the Bitton family decided to pull the plug on this unique location among the cafés in the Toronto area—and they had just a few days to vacate the premises.

Michelle Bitton cited three factors in the closure: the death of family patriarch Claude Bitton in 2018, the impact of COVID lockdowns on the business, and having to follow menu rules instituted by head office in Israel.

Further investigation led us to discover that two other locations were shutting down. We also discovered an ongoing legal dispute between the former owners of Aroma Canada and the Israeli parent company.

An arbitrator ruled in 2022 that the head office owed $10 million (plus $1 million more in court costs) to Earl Gorman, the entrepreneur who first brought Aroma to Toronto in 2007, starting with a now-closed Annex neighbourhood location on Bloor Street.

The master franchise agreement with Aro-

ma allowed Gorman to be the middleman, who could in turn sell sub-franchises to local entrepreneurs. A team led by Israeli expat Anat Davidzon helped realize the vision.

But after expanding to 46 locations across Ontario—located from Niagara Falls to Oshawa—the Canadian branch found itself in financial straits by 2017. Consultants were hired to look for savings and explore other options, including a sale.

Gorman was advised he could save $900,000 off the bat by finding a domestic coffee roast, rather than importing it from Israel. Head office worried a cheaper brew would hurt the brand’s reputation. Plus, they

blamed the Canadians for putting the business in a state that required a big infusion of cash.

According to documents, the Toronto team felt their contract allowed for changes to the coffee supply.

Today, the originators of the Canadian operation are long gone. Current franchisees deal with CEO Elad Keren, an Israeli expat, who runs Aroma Global Inc.

The parent company owners were in a Toronto courtroom in mid-January arguing to have the $10-million award to Gorman set aside. Stay tuned to The CJN Daily podcast to hear how this saga turns out.

The official Twitter account of New Jersey gets attention for throwing shade at the claim that Nike is saluting the bagel capital of the world: “Guess we’ll just have to dunk these right in the garbage until they get that typo fixed…” replies the state, with a picture of them headed for the trash.

Nike Dunk Low Montreal Bagel sneakers make news due to a press release: “Bringing fresh-baked style to the streets, this delicacy of a design rings you in with carb-lover colours, plus a pinch of Montreal blue for an extra shout-out to the city from la belle province.” Canadian retail price: $160.

A snowstorm doesn’t stop people from lining up outside the Off the Hook boutique on Ste-Catherine Street, which will be the first store to sell the sneakers. Sneakerheads started showing up at 7 p.m., with hundreds more waiting in line by morning, when a food truck served coffee and bagels.

The first buyers are asked whether they plan to wear their sesameseed shoes, keep them as a collector’s item, or resell their pair for a tasty profit. The following week, Philadelphia Cream Cheese unveils “Schmear Socks” in three flavours—and gets media attention despite never going on sale.

Montreal illustrator Felipe Arriagda-Nunez (a.k.a Chien Champion) reveals in an Instagram posting that he was commissioned to design a shoebox that captures his own pride in the city. It features cartoon images of locations like Olympic Stadium, Chinatown, the Old Port and Mount Royal.

Sketches on a restaurant napkin, a notebook draft of “Hallelujah”, black and white Polaroid snapshots of his naked chest: Leonard Cohen kept it all for posterity. Julian Cox, the chief curator of the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), convinced the Cohen estate to dig into the icon’s personal treasures and stage a never-before-seen exhibit of the very intimate collection. Everybody Knows runs until April 10 at the AGO, but The CJN Daily scored an exclusive audio tour from the curator. Listen to it online at thecjn.ca/leonard

Leonard Cohen, One of those days (Watercolour Notebook), 1980-1985. Watercolour notebook. Overall: 21.1 x 32.5 cm.

WE REMEMBER AND HONOUR

A devoted family man, inspirational community leader, and successful businessman whose enduring dedication to Israel and those injured in its defence will forever motivate us.

May Saul’s memory be a blessing to Toby, our beloved National President, and her entire family.

Wishing you good health, happiness and peace.

David Yabrov

Jerry Dykopf

Elias Benaim

Howard Bergman

Je Westreich

Jay Feingold

(416) 928-0111 | 111 Avenue Road, Toronto

Monthly rates starting at only $5,675 including 3 meals a day, rec. programs, housekeeping and 24 hour emergency nursing response.

Allan Jubenville

Jay Benaim

Colin Reitsma

Justin Abrams

Jason Simon

Kelvin Lam

Ralph Benmergui visits smaller Jewish communities across Canada (and beyond) for The CJN Podcast Network

Aryana Rayne moved to Bowen Island years ago on a spiritual search. Once she discovered a small Jewish community on the island of 3,600 people—mostly ad hoc gatherings, meeting in people’s homes and celebrating potluck holidays, with an emphasis on the mystical side of Judaism— something clicked. She began reading up on her religion and becoming a linchpin of the community. Today, the Jews of Bowen Island have a driftwood hanukkiah and a Torah scroll they bought on eBay.

When Heidi Coleman moved to Kamloops from Montreal in 2012, she had to seek out its Jewish members—asking around, searching for information that was not widely available. Once she found them, however, they welcomed her warmly… and then quickly asked her to become their president. Today the charismatic leader is still the community’s president—mostly because, as she says, nobody else wants to do the job.

Goldie Morgentaler is a literature professor and Yiddish expert who’s been active in local synagogues, engaged her university’s administration on antisemitic incidents and translated into English the work of her mother, poet Chava Rosenfarb. You might assume she lives in a hub of Jewish culture—but you’d be wrong. In 1997, Morgentaler moved to Lethbridge, where she teaches at the university. The city has fewer than 20 Jews left, but that hasn’t stopped Morgentaler from keeping the spirit of her community alive.

Prairie Sonata is the debut novel by Sandy Shefrin Rabin. Based on her own childhood growing up Jewish in Manitoba after the Second World War, the book follows a teenage girl’s relationship with a recent immigrant from Prague, who teaches her Yiddish and violin. While the story may be fictional, its roots feel very real to anyone who grew up Jewish in a small town—part of the universal experiences felt by so many Jewish Canadians.

Over the past generation, the Jewish community of Quebec City has been decimated—first by the Quebec Referendum, slowly by an outward migration of young people, and finally by COVID-19, which coincided with a loss of funds to keep any paid staff. The outlook for the couple dozen active remaining Jews looked grim. But Debbie Rootman wouldn’t accept that. She moved there in September 2019, and swiftly took it upon herself to revitalize the newsletter, organize events and galvanize community members as best she could.

Sheina Lerman wanted a quiet life when she settled in Deer Lake, a town of 5,000 people— probably none of whom are Jewish. But then she shook things up by running for the provincial NDP against Andrew Furey, who wound up becoming the premier. Furey won with 2,838 votes; Lerman came in third with 107. But when you’re a come-from-away Jew in small-town Newfoundland, you’re no stranger to being the odd person out in a crowd.

Few Canadian Jewish communities have experienced such tumultuous changes as Glace Bay. In 1902, the coal mining town became home to the first synagogue built in the Atlantic provinces, and a booming economy drew a strong Jewish population—until the city’s overall population began slipping in the 1970s. The island’s oldest synagogue closed down in 2010, and many of its Jews ended up moving away. But some stayed— and they’re eager to share their stories.

You wouldn’t expect to find Jews in Sioux Lookout, a rural town of fewer than 6,000 people in Northern Ontario that’s a launching pad for fly-in First Nations communities. But enough Jews happen to be doctors that physicians with an adventurous side embrace those challenges and have flocked there, resulting in a surprising community that bakes challah, builds ice hanukkiahs and makes gefilte fish out of river fish caught on outings with their Indigenous neighbours.

During the pandemic, congregants of Niagara Falls’ only synagogue agreed to sell the building to a developer who plans to tear it down to build a new hotel. But the spirit of the community is not entirely lost. Its stained-glass windows will be relocated to a nearby cemetery as part of its Holocaust memorial. They may not attract the region’s 13 million annual tourists, but they will remind locals of what stood before.

What does it mean to launch a 21st-century Jewish Studies program in one of Canada’s fastest-growing cities? I take up the Simon and Riva Spatz Chair in Jewish Studies at Dalhousie University in Halifax with two great inspirations: the global diversity of Jewish communities and the tradition’s remarkable ability to adapt and survive in the face of crisis. My religiously and ethnically diverse students have taught me something precious: Jewish texts and history are for everybody because they are a lens for their deepest concerns. How to live well in a society full of difference, and what does meaningful inclusion look like? Where do we belong when our identities have many parts? How to deal with loss and trauma— and what do the traditions have to teach us about them? Where do these traditions come from, and what do we do with them when our world has changed so much?

Jewish Studies is for all: Jewish students who seek to understand their heritage, and everyone interested in the big questions Jewish texts and history address. Dalhousie, one of Canada’s top research universities, and the affiliated King’s College already boast marvellous faculty in Jewish thought and Holocaust Studies. And now our Classics Department expands its reach with two new experts in Bible, Judaism, and the ancient world they come from.

Halifax has always welcomed Jewish students—unlike other universities, Dalhousie has never had a quota on them. Today the city’s growing Jewish community boasts two synagogues, Beth Israel and Shaar Shalom, as well as Chabad and Hillel, and hosts the Atlantic Jewish Film Festival.

I dedicated the Spatz Lecture, excerpted here, to the memory of Simon and Riva Spatz, who met in Germany after the war. Simon escaped a labour camp the day before the Nazis murdered all its occupants, and Riva survived with the resistance in the woods of Poland. They built new lives and a thriving family in Halifax. Their story—of survival and vitality in the face of great loss—is one of those classic Jewish stories that is also for everybody.

We know the story of Moses’s mother saving him from death by sending him down the Nile in a “basket”—the Hebrew word is tevah “ark,” as in Noah’s flood—so he could later save his people and receive the Torah. But much later, Jews told a similar story about the Torah itself, sealed up in an “ark,” sent down a river, and saved from destruction. In the later story, the river was the Rhine, and the threat was not a murderous Pharaoh, but zealous Christian censors who burned the Talmud in the streets of Paris.

Stories about rescuing Jewish books from destruction—by fire, flood, or war—are almost as old as the Torah itself. From ancient Israel and Rome to medieval France and wartime Poland, Jews have long imagined their sacred texts as damaged, lost, or partly destroyed–and in need of preservation and salvage.

What do we make of this connection between the Torah and disaster? And does it have anything to teach us about how we might live in the face of loss and catastrophe today?

We might start with a recent and familiar example: Nazi book burnings. In the 1930s, Warsaw poet Yisroel Shtern expressed the horror of watching Jewish books go up in flames:

Torah scroll, consumed by fire—ask how it goes for those who survive you, on ash-covered roads, whose eyes were prised open by pain, in amazement before the blaze of your burning parchment….

Oh, Torah, inscribed with fire upon fire— can it be that you have crumbled into cinders –transformed by earthly flames to red-hot embers— while the hand of your foe remained unsinged?

Were you given to us through lightning, Torah, that your life might end in smoke upon a pyre?

- translated by Miriam Leberstein (2006)

Shtern was drawing on a long tradition of Jewish texts from the past to respond to what he saw in his present. The Bible describes the revelation of the Torah on Mt. Sinai accompanied by lightning. Later rabbinic traditions see the original Torah as being made of fire itself: the original tablets are written by God with black fire on white fire and revealed to Moses, who smashes them when he sees the Israelites worshipping the golden calf. The second set of tablets that replaced the fiery divine Torah were just stone, written by the human Moses, and then copied on fragile, flammable parchment. The Torah is given as fire—and destroyed in fire too.

“Is there a new Torah?”

But Shtern’s Yiddish poem was not a new creation. It was a “free translation” into Yiddish of a medieval Hebrew lament, Shaali serufah baeish, by Rabbi Meir of Rothenburg,

called Maharam. He was said to have witnessed the burning of the Talmud in 13th century Paris, and his lament is still included in the liturgy for Tisha b’Av, the day of mourning for the destruction of the Temple and all other catastrophes. The Talmud is “Torah” in a broader sense—the entirety of written and oral tradition. Twenty-four wagonloads of its manuscripts— all known copies—went up in flames in the streets. “Is there a new Torah?” Maharam asked, “is that why the scrolls have been burned?”

Maharam (whose books were burned by medieval Christian censors) and his poetic heir Yisroel Shtern (whose books were burned by Nazis) witnessed destruction unique to their times, but they described it in the language of tradition. For centuries, Jews had written powerfully about the loss of sacred texts, and reflecting on the destruction of Jewish books was a poetic way to respond to catastrophe more broadly.

In Shtern’s time, the Gestapo searched for books to burn. Then they searched for human beings. Historians point out that book destruction often precedes genocide, and those of us who read Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 in school know that a burning book is a powerful symbol for the destruction of culture and of life. Bradbury himself said that human beings and books are “one and the same flesh”: articulated like this, his equivalence is grotesque, but some early Jewish writers also saw a symbolic equivalence between written texts and human beings. Rabbinic sources, for example, relate that the 2nd century Rabbi Hanina ben Teradion was burned to death by the Romans wrapped in the Torah scroll from which he had taught—blurring the boundaries between his person and his Torah. The community and its ancestral writings, closely linked, share the same fate.

But the oldest Jewish traditions about rescuing texts from disaster are not about fire, but water. Ancient Jewish writers believed that, long before Sinai, books had already been revealed to ancient heroes, like Adam and Enoch, who lived before the great flood. How could their knowledge have survived such a mass catastrophe? The historian Josephus (1st c. CE) wrote that Adam himself knew of a planned “destruction of the universe, at one time by a violent fire and at another by a mighty deluge of water.” To ensure that the knowledge of the pre-flood generations would survive either way, Josephus and other ancient Jewish and Christian writers suggested it was copied on two different tablets: one of stone and one of clay. A stone tablet could be damaged by fire but would survive a flood. A clay tablet would dissolve in water, but would be hardened by fire, like pottery in a kiln.

By the first few centuries of the Common Era, backing up your data--copying texts in two different formats, to prepare for two different catastrophes--was a wellknown idea. For Jews (and Christians too), it was not a given that the memory of God’s acts or other inspired writing would survive a major catastrophe, when generational transmission from teacher to teacher was broken. Divine wisdom exists as fragile matter, and people have to deliberately protect it, even from God’s own acts!

Fast forward to a later, historical disaster— the Babylonian Exile, which began in 586 BCE. We know that the Babylonians burned Jerusalem to the ground and destroyed the Temple, but ancient Jewish writers also worried about another kind of loss: was the Torah itself destroyed as well? How could it survive the fires of war?

Many Jewish texts imagine that the Torah was temporarily lost or damaged when the Babylonians burned down Jerusalem. They speculate about slapdash attempts to hide and save sacred books–or new revelations to restore them. One example is the Fourth Book of Ezra, an apocalyptic text from about 100 CE. Fourth Ezra was written after the Romans destroyed the second temple in 70 CE, but is set during the first destruction, with Ezra, the hero of the biblical books of Ezra-Nehemiah, as its protagonist. This reimagined Ezra cries alone

in his bed over the destroyed city–and the lost Torah: “the holy Torah of our fathers was nullified, and the written covenants are no more…” “the Torah has been burned!” But the story solves the problem: the missing Torah is revealed to Ezra once again. He is a second Moses, dictating to scribes for 40 days and nights, eventually writing not just a new Torah, but 94 books: 24 for the public, and 70 for a wise elite.

In other sources, Ezra is a more downto-earth figure, doing the work of salvage and scribal reconstruction. This motif was a widespread aspect of premodern knowledge about the Torah. Premodern Jews and Christians both suspected that sacred texts did not come down from antiquity intact, but were damaged by marauding armies, barely rescued or hidden, and perhaps

not fully restored.

One variety of this tradition comes from Timothy I, a Christian bishop in Baghdad in 800 CE. Timothy describes a second-hand report about biblical and non-biblical Hebrew scrolls found in a cave near Jericho by an Arab hunter and his dog. The letter has become famous among scholars because it’s so similar to the story of how the Dead Sea Scrolls were found in caves in the 1940s by a shepherd and his goat—but over a millennium earlier. We don’t know anything else about this alleged discovery, but Timothy tells us how he thinks these manuscripts, which he believes are the most original copies of the Bible, ended up in the cave: the prophet Jeremiah, he believes, “hid the manuscripts among the mountains and in caves and concealed them so that they

would not be consumed by fire nor pillaged by despoilers.”

Timothy was probably inspired by 2 Maccabees (ca. 2nd c. BCE), where Jeremiah hides precious ritual objects—including the Ark of the Covenant, where the tablets of the Torah were kept—rescued from the Babylonians. There, Jeremiah hides them for safekeeping in a cave on the very mountain where Moses had died, like Moses in reverse: if Moses brought the Torah down from a mountain, Jeremiah stashed it back inside one.

Stories about the Torah hidden away in a dark cave reoccur across Jewish history. We find another example in the so-called “Khazar correspondence,” which presents itself as an exchange of Hebrew letters between Hasdai, a Jewish dignitary in 10th century Spain, and the allegedly Jewish king of Khazaria.

Khazaria was a central Asian kingdom best known from Yehuda Halevi’s Kuzari, a treatise he framed as a disputation between Jews, Christians, and Muslims, ending with the conversion of the kingdom to Judaism. It is unlikely that much about the Khazars is historically accurate, and the story has been deployed in some disturbing ways—for example, claims that Ashkenazi Jews are genetically descended from central Asian peoples, a debunked conspiracy theory championed by antisemites. Yet some of these texts are nevertheless fascinating medieval Jewish cultural products: lore about a faraway, powerful Jewish kingdom would appeal deeply to minority communities in medieval Europe.

Hasdai’s letter relates a tale he had heard in Spain about Khazaria’s origins: some Jews who had lived near Mt. Seir, in danger from the Babylonian invasion, hid their holy books in a cave. They prayed there daily, even long after everyone had forgotten what made the cave distinctive. Generations later, one man went deeper into the cave to discover it was full of books, and a new era of Torah study began. Another medieval fragment contains a related account, saying that the Jews were “without Torah and Scripture” until the scrolls were recovered from a cave—heralding a mass conversion.

The story of hidden scriptures, protected from invaders, forgotten, and recovered again, becomes a founding legend: you have to lose the Torah to find it again. The idea that Jews are a people whose scrip-

tures are threatened, saved, forgotten, and recovered is now so traditional that it’s the way the story of Jewish Khazaria, too, must be told.

I collect these stories because I trained as a scholar of the Dead Sea Scrolls: my work depended on an ancient community who once hid a massive corpus of ancient texts, including various versions and types of Torah, in desert caves. The people who used and hid the scrolls perished in the Roman invasion in 70 CE. We might imagine them rushing to hide these texts, the story of Jeremiah concealing sacred objects in a cave to protect them from enemy fire alive in their minds. These texts remained hidden for nearly two thousand years, and now give us precious insight into how Jewish texts and practices developed. Our scholarship, too, starts with a story of catastrophe and concealment for a future time, and real acts of salvage and reconstruction.

What does all this tell us about Judaism and Jewish history—and about living in the face of catastrophe? Nearly 100 years ago, the Jewish historian Salo Baron critiqued “the lachrymose conception of Jewish history.” Lachrymose means “tearful,” and Baron argued against seeing Jewish history as an unrelenting tale of suffering and woe. Virtually all scholars of Judaism have had to engage this challenge in some way. We have focused on loss and disaster—a “lachrymose” set of stories indeed. But these lost Torah tales are not so much about loss as about preservation, about what can be saved and how. Our writers were resigned to disaster: there was no stemming of the flood waters, no turning back the Babylonian troops—and no convincing the medieval censors who burned the Talmud to change their minds. But some things could be rescued or preserved.

Recently, Jewish philosophers and ethicists have been considering how to respond to the climate crisis from a Jewish perspective. Canadian Jewish philosopher Dustin Atlas moves away from the common idea of stewardship of the earth, which, he says, is inadequate to a crisis that is already here. Instead, he uses the history of interpretation of the flood story–of enclosing animal species in an “ark” to ensure their survival—to highlight elements in Jewish thought that focus on protecting small but important things. God does not build the ark, Atlas notes:

God gives a blueprint (as he is prone to doing), but the building is human… we too are not only going to have to think about spaces that protect relations, but we are also going to have to build them, materially, socially, politically, and religiously. This idea of protection goes beyond the flood story: it implicates the Torah itself. The Torah’s intimate relationship with disaster, its history of human acts of rescue, is baked into Judaism’s oldest and most durable stories about itself. The Torah is born in fire, and destroyed as soon as it’s given. It is continuously lost, hidden, salvaged, reconstructed after flame, flood, and war. Through these myths of a lost Torah across centuries, we see ways that Jewish tradition has lived in relation to disaster—to respond to it through acts of protection and repair.

We began with a Yiddish reprise of a medieval Hebrew lament by Meir of Rothenburg, who saw the Talmud aflame in the streets of Paris. He asked, “Is there a new Torah to replace the scrolls that were burned?” His question received an unexpected answer in a much later folktale, which built on an ancient rabbinic tradition that Moses wrote thirteen Torah scrolls: twelve for the nation, and the thirteenth to keep in the Ark of the Covenant in the Temple. After the Temple’s destruction, this thirteenth Torah was kept in heaven. This tradition is at the heart of a later story about Rabbi Meir’s experience in prison. The angel Gabriel visited him and showed him this thirteenth scroll to copy. He sealed his copy of the celestial Torah in a waterproof container and threw it into the Rhine—a mini-ark, more like Moses’s than Noah’s. It was discovered downriver by some Jewish fishermen and placed in their synagogue. No new Torah has been given—but Maharam could write a spare copy and protect it from harm.

Moses receives the Torah on a mountaintop in thunder and lightning, but centuries of Jewish stories about preserving and salvaging books are more down to earth: make an extra copy; back it up in two ways, on stone and clay; run from the soldiers to stash it in a cave; cobble it back together from fragments; and, here, put a copy in a vessel, toss it out your prison cell, and hope some fishermen will catch it. There is no single heroic act that will turn the tide, but simple and practical acts to protect what’s worth saving. n

Watch the entire lecture at thecjn.ca/spatz

Experience amazing challenges with a purpose, create social impact and economic independence for women entrepreneurs, and be the change to create a sustainable tomorrow. Find the full trip itinerary and learn more at:

MAKE AN IMPACT.

THE JOURNEY BEGINS WITH YOU.

Thanks to a $1-million gift from donor Miriam Roland, Concordia University will partner with Ben-Gurion University of the Negev to find more sustainable approaches to urban development.

An event like the Dreyfus Affair, with a complicated and protracted timeline, doesn’t really lend itself to anniversaries.

It began in 1894, when French Jewish army officer Alfred Dreyfus was accused (and in 1895, convicted) of treason, for having allegedly sold secrets to Germany. Dreyfus was pardoned in 1899 and exonerated in 1906. That stretch between 1894 and 1906 was chock-full of key turning points, relating both to the Dreyfus case itself and to how it was received in France and beyond.

But what we’re looking at now is the 125th anniversary of the moment that turned the Dreyfus case into the bigger phenomenon now known as the Affair. On Jan. 13, 1898, the French novelist Émile Zola published his pro-Dreyfus open letter, “J’Accuse…!” in the French newspaper L’Aurore. Zola’s intervention became a cultural force in its own right, evoked whenever anyone wants to righteously accuse others of a miscarriage of justice. The French expression, “J’Accuse”, is also used in English, in homage to Zola. While central to modern history generally and Jewish history in particular, the Affair remains somewhat obscure to non-historians. It is rather understandably overshadowed the Holocaust. But it is key to understanding that and more.

Heather Camlot, a Toronto children’s-book author and journalist, is the author of The Prisoner and the Writer, a middle-grade novel, in verse, about the Affair. Illustrated by Sophie Casson, the book alternates between depicting Dreyfus and Zola, through Dreyfus’s imprisonment on Devil’s Island and Zola’s growing involvement in the fight to free him and clear his name:

“After more than four years on Devil’s Is-

land, the prisoner can read / A note handed to him by the chief guard. / The most important message of his life: / His sentence has been annulled. / Alfred is going home.”

The Prisoner and the Writer is already getting quite a bit of attention, including a review in the New York Times. It has lots to offer for older readers as well. (Younger, too, if your baby’s feeling patient.) Camlot’s previous books include The Other Side, which tells the story—inspired by family histor—of a Canadian Jewish boy whose German non-Jewish grandfather fought for Nazi Germany in the Second World War. She also has a forthcoming book, Becoming Bionic, a middle-grade nonfiction book that uses superheroes to educate about scientific advancements such as prosthetic limbs.

Camlot is one of the most exciting writers in Canadian Jewish letters today—and it was my honour to interview her.

The Dreyfus Affair is wellknown to students of French Jewish history but not a part of household knowledge in North America. When and how did you first learn about it?

When I was a teenager, I used to watch a lot of late-night movies. You know, old classic silver screen type of movies. And one night, the life of Emile Zola was on. And I watched it.

I grew up in a in a Jewish neighborhood in Montreal, Dollard-des-Ormeaux, on the West Island. I went Hebrew school, and everyone I knew as a child was Jewish. That was kind of everything I knew.

When I went to high school, at West Island

College, all of a sudden, we were only a handful of Jewish kids in the grade, and even in the school. And it opened up my eyes to the greater world. High school led me down a path of learning about the world and other cultures and what was going on.

Learning about the Dreyfus Affair, even if it was through a movie to start with, really hit home. I mean, I lived a French city. I’m Jewish. And seeing what happened to a French Jewish man who did nothing wrong has stayed with me forever.

What do you see resonating about the Dreyfus Affair for young readers?

We’re seeing a lot more hate in the world today, of all kinds. We have to start educating children about hate, and how to rise above it, because once we’re adults, it’s too late. Adults are so ingrained in our thinking, whether we’re right or wrong. So that I think is why I wanted to write about the Dreyfus Affair for children, so they could have the same kind of eye-opening experience I had when I was a little older. They can learn what is going on in the world, how they can do something, how they can stand up and speak out. The Dreyfus case itself, where everything was fabricated, lets kids know that adults aren’t always right.

So that’s one point. And then the second point is, we’re so surrounded by news and “news,” and kids don’t really know the difference. I wouldn’t have known the difference. But kids learn things on social media or on the Internet, or from friends, and believe it.

And I think this story, because it was a story fought in the newspapers, offers media education for kids as well.

What led you to opt for this telling, where Dreyfus and Zola are side-by-side?

That was the idea of my editor, Karen Li. She’s now the publisher of Groundwood. When I originally brought her the story, it was just written in prose, just your typical kind of biographical book. She had this vision of how to make it even more powerful. And the more research I did into it, I realized that even though their stories are not perfectly parallel, it lined up.

It does work, really well! But the story itself can be confusing even for adults.

It has a complicated chronology, and hinges on something called the bordereau, a document that supposedly proved that Dreyfus was spying for Germany, and thus guilty of treason. How did you approach simplifying the narrative while maintaining accuracy?

That bordereau was tricky to figure out. I called it “six torn pieces of handwritten paper found in the garbage,” which is essentially what the bordereau was.

Do you think the Affair is better understood as a prelude to the Holocaust, or rather as an example of justice triumphing and of France being ultimately not as antisemitic as imagined?

I don’t think I’ve ever thought of those two scenarios side by side, in order to have to choose one. It undeniably leads up to the Holocaust, because Dreyfus’s granddaughter was killed at Auschwitz. In the Affair itself, everything was fixed and patched up, and Dreyfus was pardoned. But his quote, “My only crime was to have been born a Jew,” repeated itself, a few decades later, on a much larger scale. I don’t know if I could. I can’t pick.

I agree that it’s both.

The Dreyfus Affair polarized France politically. To what extent do you see it as possible to make parallels between that period of French history and contemporary North America? Are there modern-day equivalents of Dreyfusards and anti-Dreyfusards?

This is going to sound horrible, but it’s quite similar. We have people like Kanye West speaking out. He’s got such a following. People just kind of dismiss it, right?

Like, Oh, he’s got a mental illness, or, Oh, he’s Kanye, he says silly things. It’s almost a way to sweep something under the rug. And that is what was done during the Dreyfus Affair. They were trying to just sweep the whole thing under the rug. They were hoping that nobody would question it when they sent Dreyfus away. But people did question it.

It’s the same thing here. People are saying, No, we can’t sweep this away. As a result, Kanye has lost professional relationships.

The Dreyfus Affair offers what is in retrospect a fairly simple story of good versus evil. Apart from the occasional ultra-conservative Christian publication, no one these days is taking the anti-Dreyfusard stance. Today, political polarization—or figuring out who the good and bad guys are—sometimes seems more complicated.

I think it’s always been complicated. I remember reading once upon a time about the Holocaust Museum in Washington. This particular feature was that when you walked in, you had to choose a door. And one door said something like, “I have prejudices,” and the other door said, “I don’t have prejudices,” and the door that said, “I don’t have prejudices” was locked.

Everybody has some sort of prejudice. We’ve all been taught some, from our parents, our community, or what we read in the newspaper. What we have to do is accept

that we have biases and prejudices, and work on them.

How can North American Jews balance a love of Europe, maybe Paris in particular, with the knowledge of all the terrible fates Jews have met in that part of the world? This tension exists in The Prisoner and the Writer, which is at the same time this terrible story of French antisemitism, and this beautiful document showing illustrations of France.

I’ll put it this way, and I don’t know if it’s an answer to your question or not. I never wanted to go to Germany, because I’m Jewish. I learned in school everything about the Holocaust, and World War Two, and Hitler and all that kind of stuff. I never wanted to set foot in Germany.

Now. I’m married to a man of German descent. His parents were German. His father was a child soldier during the Second World War. We had to talk a lot about that before.

Eventually, my husband said, I want to show the children where my parents are from, and technically where they kind of come from, their heritage. Both his parents had passed by then. I was like, what am I going to do?

And I said, OK, let’s go. I did research for my book, The Other Side, at the same time, because it was inspired by the story of his father. And, you know, when I got there, I loved it. I love Germany. It’s beautiful. The people are friendly. They’ve tried very hard to make reparations.

I learned that there are new generations, people who are trying to fix things. But I can say that for Canada as well, which turned around the MS St. Louis ship many of whose passengers ultimately died in the Holocaust. Do I hate Canada? I mean, that was a horrible thing to do! Cuba turned it away; the United States turned it away. Canada was the last hope—and they turned it away.

So, to answer your question, I think you have to look at the good and the bad. You have to see the positivity, and hope that change has come to all these places, including where we live right now. But not forget about the history.

We need to keep learning history, we need to teach history to children, because that’s how things change. And yes, Paris is a beautiful, bright, wonderful, fun-loving city, ala Emily in Paris. But it does have a dark history, as does Germany, as does Canada, as does the United States. Look at slavery in the United States. None of us are unscathed. None of our pasts are 100% good.

The Dreyfus Affair isn’t really a History 101-type topic. Those learning about it today tend to already have a broader historical background and will be putting it into that context. Do you think middle-grade students have the Holocaust as a reference point, or that The Prisoner and the Writer might wind up being their introduction to that as well?

There are startling statistics on how Canadians in their teens and 20s, and even later, don’t know anything about the Holocaust. They don’t know it happened. I love the fact that Ontario elementary schools are getting a Holocaust education in the grade six curriculum. And I know that in high school, because my kids have already done it, they’ve included Holocaust education through literature. I don’t know if that’s across the board in Ontario, but I do know that he had it at his school in Toronto.

I think we need not just Holocaust education, but to teach stories of other cultures that have undergone similar.

This leads rather perfectly to my next question, which is that at the end of the book, after the story itself, there’s an educational prompt asking readers to consider Dreyfus’s remark, “My only crime is to have been born a Jew,” replacing “Jew” with other marginalized identity groups. Do you think relating antisemitism to other hatreds is the best way to engage young people?

I should say that I’m torn because on the one hand, people can benefit from a nudge towards relating to others different from themselves. On the other, there’s the danger of getting into a situation similar to the thing where people respond to “Black Lives Matter” by saying that “All Lives Matter,” and while yes, all lives do matter, it doesn’t quite work in that context to say this. I guess I’m admitting that I’m also confused about how to approach this!

The reason I asked people to replace the word Jew in Dreyfus’s quote is as a way of likening a situation to what might be their own. We all know what issues we have. You have to put yourself in somebody else’s shoes in order to understand what they’ve gone through. And you need to understand your own situation in order to empathize with other people.

The problem I see right now is that we’re all siloing each other. Everybody is seeing their own issues, and dealing with their own issues, as they should. But I think we’re so focused on those individual issues that we’re not seeing how all of this plays together in the world. We must work together. We can’t just be like, I’m Jewish, I’m going fight antisemitism, or I’m a woman, I’m going to fight for women’s rights. If we want to make the world a better place, we have to do it together. n

At VIVA Retirement Communities , you could be

Whether you’re making a splash with an AquaFit class in our heated, indoor saltwater pool, kibbitizing over a coffee in our bistro-café Perks! , or simply enjoying a gourmet meal. At V!VA Retirement Communities we take care of the cooking and cleaning so you get to enjoy what matters most – precious time with good friends doing what makes you smile.

To learn more, please call Wendy at (905) 417-8585 or email thornhillwoods@vivalife.ca.

Wishing you happiness and health at Passover

Vaughan’s Premier Jewish Retirement Community 9700 Bathurst Street, Vaughan, ON. Across from the Schwartz/Reisman Centre | (905) 417–8585 | vivalife.ca

INDEPENDENT & ASSISTED LIVING | ANYTIME DINING

In the spring of 2020, when I was not getting out much and thus even more entrenched than usual in online debates, I was asked to sign what would turn out to be a viral phenomenon that would be dubbed The Harper’s Letter: an open letter on the subject of illiberalism which, while it did not use the expression “cancel culture,” was a condemnation of that phenomenon:

Editors are fired for running controversial pieces; books are withdrawn for alleged inauthenticity; journalists are barred from writing on certain topics; professors are investigated for quoting works of literature in class; a researcher is fired for circulating a peer-reviewed academic study; and the heads of organizations are ousted for what are sometimes just clumsy mistakes.

When the draft first landed in my inbox, it seemed like a well-meaning statement from some academics, and I didn’t think much of it. I did not know at the time that it was destined to be published on the website of

highbrow magazine Harper’s, or that famous people would be signatories. But I read the letter to see if it was something I agreed with, and it was. What I liked about it was that it spoke out against left censoriousness, while making it clear that there were at least as significant dangers from the right:

Some are critical of left excesses because they want liberalism stronger, others because they want to see it destroyed; this was clearly a message from the former, which is where I place myself. (The big clue in that regard was the reference to Donald Trump as “a real threat to democracy.”) The letter was not about mocking the politically correct for kicks, but about defending liberalism.

Was the letter, with its emphasis on “the value of robust and even caustic counterspeech,” somehow…Jewish?

An open letter is a curious form of writing. Open letters tend to involve somewhat grandiose remarks, sketched so broadly that it may seem as though no one could possibly disagree with their contents. As such, they derive much of their meaning from who’s written the letter and who’s being addressed.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy looks between the lines of public statements we’re invited to co-sign

Open letters are sometimes about internal institutional concerns, but only when there is some general interest in those matters outside those organizations. The latest splash-making open letter, at the time of my writing in February 2023, is from New York Times contributors, critical of the paper’s coverage of transgender issues.

An open letter is about harnessing the voices of many to reach the powerful—and, perhaps, otherwise unreachable—few. But it is not a petition. A petition has a measurable goal, whereas an open letter is usually a statement of principles, such that it may never really be known if an open letter’s signatories got what they wanted.

Also unlike a petition, which is typically democratic from the get-go, an open letter will at least begin with a set of original, invited, signatories. As such, an open letter is as

much about the reputations of the signatories as it is about the ideas expressed in the letter itself. It functions as a who’s-who, in multiple senses: it tells you who stands where on a given issue, but also derives much of its impact through bold-facenames, community stalwarts, subject-matter experts, and prominent organizations that endorse it.

Émile Zola’s 1898 newspaper article, “J’Accuse…!,” the earliest and most famous example of the form, certainly mattered because of what was said, but also because of which strong-willed fiction writer was saying it. It’s credited with turning the Dreyfus case into the Dreyfus Affair, not merely because Zola called out the French president and others for falsely accusing French Jewish army officer Alfred Dreyfus of treason, but because he highlighted all of this to the general public. What might have remained an internal squabble amongst elites became instead a topic that captured public debate in France and beyond. It took J’Accuse…!” for the case to become the Affair, a shift

that can be credited with Dreyfus’s ultimate exoneration.

Zola himself was not Jewish, but the relationship between the form of the open letter, and the act of defending Jews, seems to have stuck. There was a gentile-allies Guardian open letter in 2019, from famous British non-Jews (among them Joanna Lumley, who played Patsy on “Absolutely Fabulous”) who refused to support a Jeremy Corbyn-led Labour party. But we Jews cannot be accused of sitting by and letting others compose open letters about us. We are extremely, impressively, on the case.

What follows, then, is a journey though Jewish open-letter-writing of the last few years. Whether motivated by a Jewish interest in contentious debate, a Jewish urge to protect liberalism, or the sadly timeless Jewish activity that is defending ourselves from our enemies, Jews have composed and signed many an open letter in our time. They’re perhaps a fitting genre of writing for a group of people of tremendous symbolic significance to the wider world, but whose own voices have a way of getting drowned out.

Explicitly Jewish open letters abound. Seemingly every day, my Twitter feed alerts me to a new one, each one shared like the press release it effectively is. Each one presents itself as a supremely important statement from people who simply must be heard. And maybe they all are! That said, it can be difficult to keep up.

The natural place to begin our journey through Jewish open letters of the past few years would be the Jewish Institute for Liberal Values’ 2021 missive, “A letter to our fellow Jews on equality and liberal values,” a defense, on Jewish grounds, of free speech

Some news outlets referred to as the “so-called ‘Jewish Harper’s letter.’” It shared a few signatories with, and took some inspiration from, the original. (Hello again Bari Weiss, Steven Pinker, et al.) The gist was that it is bad for the Jews—and not just bad generally—that these days, you can’t say anything anymore without getting cancelled:

[The]suppression of dissent violates the core Jewish value of open discourse. Jewish tradition cherishes debate, respects disagreement, and values questions as well as answers. In ancient times, the Beit Midrash––the House of Study––encouraged passionate argument “for the sake of heaven.

This letter soon elicited an unstated response in the form of “A Letter to Fellow Jews on Open Discourse, Rigorous Inquiry, and Generosity of Spirit ” The letter is not so much a defense of social justice ideology as pushback against “strawman caricatures” of ideas about which critics are sometimes ignorant. It’s basically saying, don’t throw the intersectionality baby out with the antisemitic bathwater:

Any discussion about [social justice] concepts must take them seriously and read them fairly, and we are concerned that the attempt by some in the Jewish community to present such theories as inherently offensive, dangerous, or (paradoxically) censorial is in effect demanding the suppression or dismissal of important conversations the Jewish community should be having.

communal professionals. Both came to the conclusion that racism is bad and free speech is good.

Someone not immersed in these debates would be forgiven for thinking they’re reading about the same letter twice—except then they realize the letters are arguing with each other, and the poor naïve observers find the whole thing reminiscent of Monty Python’s Life of Brian, in which the Judean People’s Front clashes with the People’s Front of Judea.

But there are clues, from both the signatories (Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg will probably have a take on things somewhat to the left of Liel Leibovitz) and the letters themselves, that they actually express two different stances.

Per the Liberal Values letter, “An ideology is taking hold across the country that insists there is only one way to look at the problems we face, and those who disagree must be silenced.” This is later clarified as referring to “the dominant social justice ideology,” and is, per the letter, particularly worrying for Jews. “Because this dominant narrative creates a worldview in which groups are only oppressors or oppressed, it encourages pernicious notions of ‘Jewish privilege,’ even implicating Jews in ‘white supremacy.’”

To this, the Jews for Open Discourse retorted, “Sweeping statements that such theories (for example) make crude divisions of the world into ‘oppressor’ and ‘oppressed’ classes, or explicitly identify Jews as White supremacist dominators, must be supported with evidence, not simply stated as if fact.”

Both letters made fair points. Yes, the current social justice framework is often hopeless at making sense of antisemitism. (Roughly the David Baddiel, Jews Don’t Count, argument, though it predates that book.) Also, yes, critics of social justice ideology have been known to wholesale dismiss ideas that come from academia or activism, even when those ideas are beneficial to Jews, because they think the language sounds silly or jargony.

Taken together, the two letters illustrate that Jewish values lead some to embrace, and others to reject, so-called wokeness. Yet as much as they reveal an ideological schism, they also point to a shared Jewish value in thinking the people you disagree with are still worth arguing with. And open letters are a perfect venue for hashing such things out.

In May 2016, as part of a decades-long project to arrive at an agreed-upon description of anti-Jewish hate, the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance published a definition of antisemitism. That definition includes, among others, the claim that “denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination, e.g., by claiming that the existence of a State of Israel is a racist endeavor,” is a core form of antisemitism. As such, rather than establishing antisemitism’s parameters once and for all, the IHRA definition has been a source of contentious debate. Some critics of Zionism have viewed it as conflating criticism of Israel with antisemitism, while some free-speech advocates—whatever their own views on Zionism—have seen it as stifling free expression.

Unsurprisingly, the IHRA definition triggered not just one open letter but spurred the development of what has become a veritable genre.

An early entrant in this new body of literature came, in February 2020, from the organization Independent Jewish Voices of Canada. Its “Open Letter from 650+ Canadian Academics Opposing the IHRA Definition of Antisemitism” argued that the IHRA definition would impede free expression: “We urge all those who value honest debate and academic freedom to reject the imposition of a definition that would imperil the pursuit of truth and the legitimate expression of dissent.”

In May 2021, Michael Mostyn’s “An open letter to Canada: It is starting to be unsafe to be a Canadian Jew” appeared in the National Post, from the opposite perspective. Addressing “Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, premiers, mayors, university presidents and all Canadians of good conscience,” Mostyn, chief executive officer of B’nai Brith Canada, summed up then-recent antisemitic incidents (spontaneous harassment of Jews; fallout from pro-Palestinian and pro-Israel rallies) and determined that this was, for Canadian Jews, a “time of crisis.” Unusual for an open letter, Mostyn’s gave concrete suggestions, including the need to “adopt the IHRA working definition of anti-Semitism without delay, especially within universities where the problem is most acute.”

Also taking on antisemitism, more recently, was the Union for Reform Judaism’s Letter to Elon Musk.

Both letters were signed by illustrious rabbis, academics, journalists, and Jewish

***

Open letters have also played a key (which is not necessarily to say effective) role in the ongoing fight against antisemitism

The letter, also signed by the Reform Jewish Community of Canada, as well as many Reform congregations in the States, and some progressive Jewish organizations, asks Musk to make Twitter less hospitable to

antisemites. Antisemites possibly including… Musk himself. “We are equally concerned by several of your own posts that suggest sympathy for white supremacists. This includes your tweets of a photo of a Nazi soldier and Pepe the Frog, which has become a popular meme among the alt-right.”

There’s a certain poignancy to this attempt at reasoning with a billionaire edgelord. Who knows what Elon Musk is doing at the moment, but one imagines it’s not reading what Reform Jews think about him. I can only wish the letter-writers well.

***

Remember intermarriage? The topic too earned its own 2021 open letter.

Matthew Bronfman, Canadian-adjacent businessman and philanthropist, had given an interview to the website eJewish Philanthropy, in which he was asked: “What worries you, keeps you up at night?” Bronfman’s answer was “intermarriage.”

I think the Jewish communal fixation on tsktsking intermarriage has been at best futile

and at worst insulting. Matthew Bronfman evidently does not. Having been married four times, he is doubtless well-versed in marriage-related topics. And if he managed to find not one but four Jewish wives, more power to him. Whatever.

“Whatever” was not the sentiment of interfaith Jewish non-profit 18Doors. In response to Bronfman’s remark, the group put out “An Open Letter to Matthew Bronfman On Behalf of Interfaith Families.” In it, the organization’s leader, Jodi Bromberg, pointed out that hostility from the community (and apathy from donors) has led to intermarried Jews and their offspring feeling left out. True enough, although it’s unclear that someone who defines Jewishness differently than Bromberg does (or than I do, for what it’s worth) would be persuadable via a letter along these lines.

***

We are now in a new phase of Jewish open letters, as North American Jews critical of the recently elected right-wing

Israel government have not just spoken out against it but asked their fellow diaspora Jews to do the same. February 1 saw a missive from 169 U.S. Jewish leaders including “the former executives of rabbinical seminaries, Jewish Federations, AIPAC and the Conference of Presidents.” The letter, “A Leadership Call for Critical and Necessary Debate About Israeli Policies,” takes an unanticipated stance: “There is no contradiction between combating antisemitism and criticizing the deeply troubling policies of the new Israeli government.”

Unanticipated, that is, from those speakers. Typically, anyone associated with pro-Israel advocacy is not also associated with open letters that state several times throughout that it’s not antisemitic to criticize Israel. What’s interesting here is that this refrain comes up not to appease Israel’s critics, but because the signatories themselves actually are the critics.

The following day, this letter was joined by “An open letter to Israel’s friends in North America,” signed, “With blessings from Jerusalem,” by Matti Friedman, Daniel Gordis, and Yossi Klein Halevi. The three writers, all of whom had moved from North America to Israel, take the unusual step of asking diaspora Jews to get busy… criticizing Israel.

Open letters criticizing the Israel—or Canadian news coverage thereof—are not new, but are associated with the pro-Palestinian, or anti-Zionist, left.

The novelty with these new letters, then, comes from the speakers. These two latest letters criticize the Israeli government to defend Israel’s existence. It’s not entirely unlike the Harper’s letter’s criticisms of progressive pieties, aimed, as they were, at maintaining, not dismantling, progress. They show a perhaps Jewish tendency—knowing that extremism doesn’t work out so well for us—to want to preserve all that is working while critiquing that which is not. ***

Jewish open letters are, then, a way for a group of people often spoken about as an abstraction to speak up for ourselves. And they’re a way for a community famous for holding wide ranging opinions to force itself to find at least partial common ground. But the question with Jewish open letters remains the same as that with open letters generally: Is anyone listening? n

If there’s an open letter you cannot believe we left out, please address your open letter to pbovy@thecjn.ca.

Idecided to write a book about antisemitism mostly out of curiosity, to explore a subject I knew little about. In a long career as a law professor, practicing lawyer, and writer, I’d witnessed some antisemitism, and even occasionally experienced mild forms myself, but to me most modern expressions of this ancient prejudice seemed inconsequential and not very interesting.

The fact that I knew little about the subject seemed like a good thing. Perhaps, just perhaps, I could approach this difficult topic largely free from initial judgment and prejudice, without an axe to grind.

In the book I start with the surprisingly complex basics: Who is a Jew? What is antisemitism? Why does it happen? I explain how contemporary identity politics sidelines Jews in favor of other historically oppressed

populations.

I describe the very different experiences, in history and today, of Jews in Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, and America, and the longstanding tensions between Jews and Muslims, and Jews and Christians. I examine the Holocaust, which brought the fight against antisemitism to new heights, and Zionism, which has set the fight back. I ask: Are modern Jews victims or superheroes? I tell of Jews as wanderers (the book is dedicated to “those who wander the world”). And, in the chapter excerpted here, I consider the relationship between Jews and the media. Most people think they know what antisemitism is, but their conviction doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. Contemporary definitions—particularly the widely-endorsed 2016 International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance

(IHRA) “working definition” adopted by the Government of Canada—are weak, grasping unconvincingly for meaning and content, and are formulated principally in a political context to serve a political purpose. These definitions blur important distinctions, confuse issues, and inflame passions, sometimes intentionally. I argue that we need to think differently about antisemitism. We need to discard ideas and attitudes that have been routinely accepted without critical appraisal and have been encouraged by those on both sides of the argument in order to manipulate opinion and politics. We need to quit worrying so much about antisemitism in the form of incivility, conspiracy theories, and Holocaust denial, and concentrate on expressions that are organized, institutionalized, and violent. I try, in my book, to reframe the antisemitism debate.

How a person and a community think of themselves, and how others think of them—the identity they acquire and possess—depends on how they are depicted. There will be competing depictions. A person and a community will describe themselves, but the world will see that as self-serving and apply a big discount. What really counts is what outsiders say. At the end of the day, we do not create our own identity. Others do it for us, directly and indirectly. Our identity is thrust upon us. Alain Finkielkraut quotes Sartre: “It is sufficient that others look at me for me to be what I am.” Or, as the central character in Luigi Pirandello’s play Right You Are (if you think so) puts it, “I am whoever you think I am.” When it comes to describing us and our community, outsiders may be prejudiced, misinformed, and badly motivated, perhaps cynically seeking some kind of strategic advantage. And they may disagree.

We may even disagree, amongst ourselves, about our identity. We may be unsure who we are. Outsiders may be more certain. It’s easier for them. And more fun. Once upon a time, starting in the 15th century, much creation and depiction of identity happened in print— books (particularly novels), pamphlets, then newspapers—and sometimes on the stage. The reach of these media, initially small, quickly became big. By 1500, in Europe, there were printing presses in more than 150 places, and probably at least 13 million books in circulation (Europe then had a population of about 100 million). It is estimated that 200 million books were printed in Europe in the 16th century. This was the beginning of what Benedict Anderson calls “print-capitalism.” Anderson argues that the biggest consequence of print-capitalism was the development of “national print-languages” allowing many people to read the same thing at the same time. Few more important things have happened in history. It made possible “imagined communities” leading to modern nation-states. Thus was born nationalism, a new and potent force. Nationalism begat xenophobia. Nationalism and xenophobia made a particular enemy of the Jews, a displaced people without a country. There was no room for Jews in somebody else’s nation-state. The only solution for Jews was to become nation-

alists themselves and acquire their own nation-state. Zionism was the solution. Or so many Jews (not all) thought.