The Gender & Sexuality Issue

Jabez Choi explores the histories inside New Haven gay bars. 16

Theia Chatelle and Iz Klemmer follow three trans kids seeking gender-affirming care in New Haven. 34

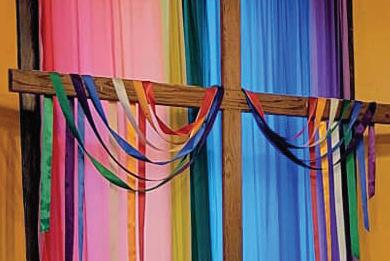

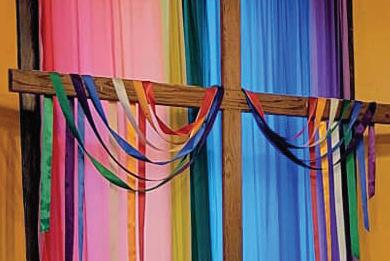

Abbey Kim finds how queer Christians enrich their spiritual lives. 42

Volume 55, Issue 4 March 2023 The Magazine About Yale and New Haven

Letter from the editors

Dear readers,

The New Journal ’s tagline has always been: “The Magazine about Yale and New Haven.” Our mission, as we understand it, is to represent these spaces through the stories of the people who occupy them. Recently, we’ve been thinking more about how best to do so.

We began our year as a managing board by discovering a trove of dusty archives—hundreds and hundreds of time capsules of the University and the city. We ended the year with TNJFest, where the past collided with the present as alums of the last fifty years descended on the Branford Common Room. These bookends on our term have affirmed to us that TNJ is a living history, and journalism can do essential record-keeping. More than that, we’ve been reminded that longform can follow the narratives behind the numbers, make human the abstractions of headlines, and in doing so disrupt assumptions; contradict generalizations; and reveal gaps in the common discourse.

Across the nation, queer people are facing renewed threats. Dozens of bills have been passed in state legislatures this year that restrict transgender people from accessing gender-affirming care, despite medical consensus that this care is sound and necessary. Anti-LGBTQ + violence is on the rise, and the tired caricature of queer people as predatory “groomers” has reappeared in popular media. At what may be a regressive inflection point for LGBTQ + rights in America, the future hangs uncertain.

In this issue, Abbey Kim explores queer Christians’ ongoing battles for acceptance in their churches. Jabez Choi chronicles the decline of gay bars, and asks the question: what is the meaning of a “safe” space? Sasha Carney traces the history of lesbian social life on campus, and Jools Fu navigates the complicated masculinity of the Singapore Armed Forces. Theia Chatelle and Iz Klemmer explore the obstacles trans kids face when seeking genderaffirming care, while Hannah Szabó remembers the spaces and people that supported her own journey during childhood.

These stories aim to situate some of New Haven’s queer life in both history and experience. We hope to do in this issue the same thing we have sought to do since 1967, a purpose reiterated in our October 2001 issue’s letter from the editors: to put our moment in context.

Masthead

Editors-in-Chief Nicole Dirks

Dereen Shirnekhi

Executive Editor Jesse Goodman

Managing Editor J.D. Wright

Associate Editors

Amal Biskin Abbey Kim

Meg Buzbee Yosef Malka

Jabez Choi Cleo Maloney

Lazo Gitchos Paola Santos

Ella Goldblum Kylie Volavongsa

Yonatan Greenberg

Senior Editors

Beasie Goddu Madison Hahamy

Alexandra Galloway Zachary Groz

Copy Editors

Marie Bong Edie Lipsey

Adrian Elizalde Lukas Trelease

Rafaela Kottou Yingying Zhao

Creative Director Kevin Chen

Design Editors

Meg Buzbee Charlotte Rica

Camille Chang Karela Palazio

Etai Smotrich-Barr

Photography Lukas Flippo

Anson M. Beard

James Carney

Andrew Court

Romy Drucker

Jeffrey Foster

David Gerber

David Greenberg*

* Donated twice. Thank you!

Matthew Hamel

Makiko Harunari

James Lowe

Chaitanya Mehra

Ben Mueller

Sarah Nutman

Peter Phleger

Jeffrey Pollock

Adriane Quinlan

Elizabeth Sledge

Gabriel Snyder

Fred Strebeigh

Arya Sundaram

Stuart Weinzimer

Steven Weisman

Suzanne Wittebort

Members & Directors: Emily Bazelon • Peter Cooper • Jonathan Dach • Kathrin Lassila • Elizabeth Sledge • Fred Strebeigh

Advisors: Neela Banerjee • Richard Bradley •

Susan Braudy • Lincoln Caplan • Jay Carney • Andy Court • Joshua Civin • Richard Conniff •

Ruth Conniff • Elisha Cooper • Susan Dominus

• David Greenberg • Daniel Kurtz-Phelan • Laura

Pappano • Jennifer Pitts • Julia Preston • Lauren

Rawbin • David Slifka • John Swansburg • Anya

Kamenetz • Steven Weisman • Daniel Yergin

Friends: Nicole Allan • Margaret Bauer • Mark

Badger and Laura Heymann • Anson M. Beard •

Susan Braudy • Julia Calagiovanni • Elisha Cooper

• Haley Cohen • Peter Cooper • Andy Court • The Elizabethan Club • Leslie Dach • David Freeman and Judith Gingold • Paul Haigney and Tracey

Roberts • Bob Lamm • James Liberman • Alka

Mansukhani • Benjamin Mueller • Sophia Nguyen

• Valerie Nierenberg • Morris Panner • Jennifer

Pitts • R. Anthony Reese • Eric Rutkow • Lainie

Rutkow • Laura Saavedra and David Buckley

• Anne-Marie Slaughter • Elizabeth Sledge

Caroline Smith • Gabriel Snyder • Elizabeth Steig

• Aliyya Swaby • John Jeremiah Sullivan • Daphne and David Sydney • Kristian and Margarita

Whiteleather • Blake Townsend Wilson • Daniel Yergin • William Yuen

•

2 TheNewJournal

Thank you to our donors thenewjournalatyale.com

TNJ love, The Managing Board

Neela Banerjee*

A Scene of Outsiders

At Space Ballroom, Danya Blokh is in for a night of “non-denominational, non-binary” hardcore. snapshots

Yalesbians, Sappho, and the Lesbian

Life of the Party

A genealogy of lesbian social spaces at Yale.

By Sasha Carney

By Sasha Carney

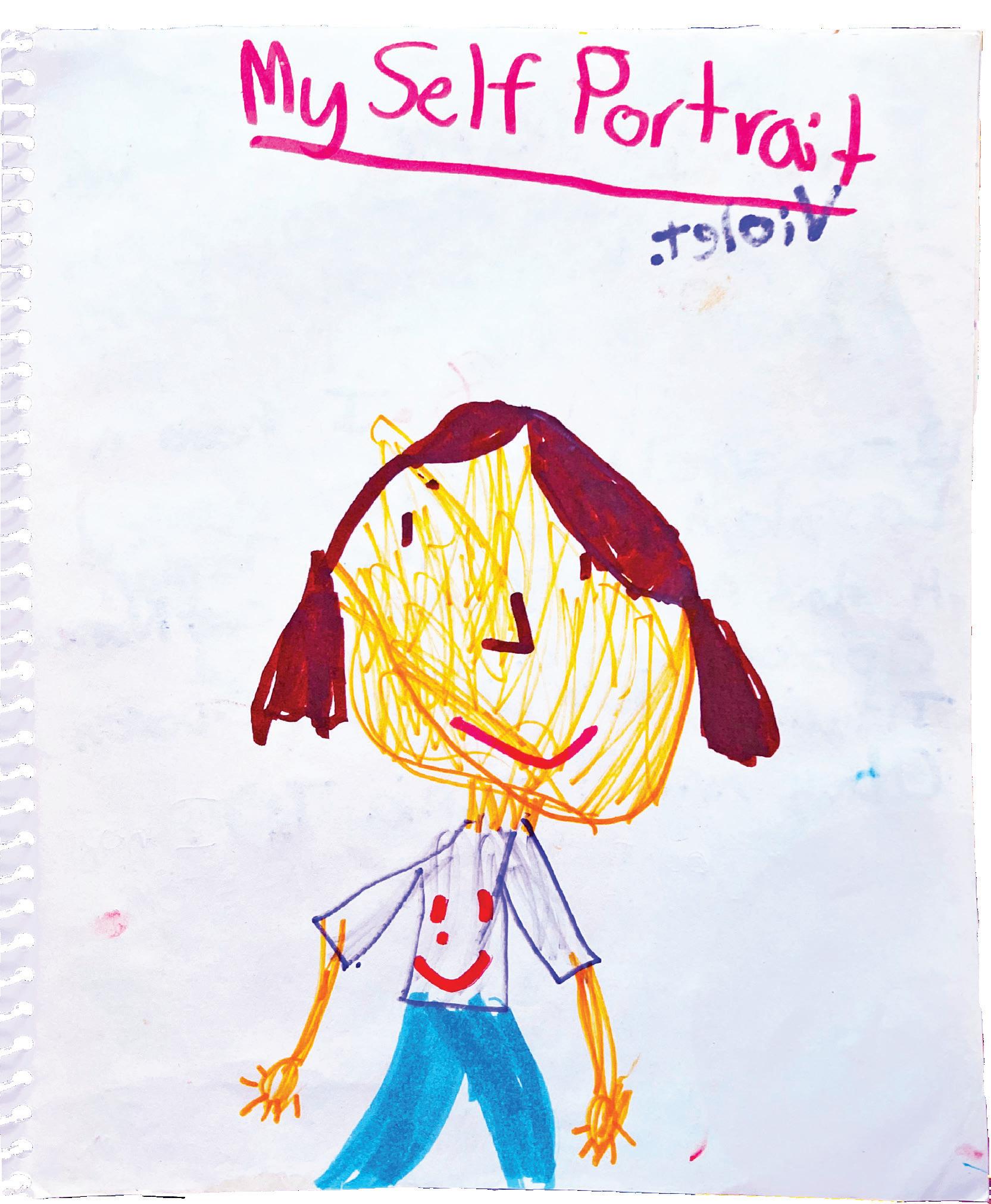

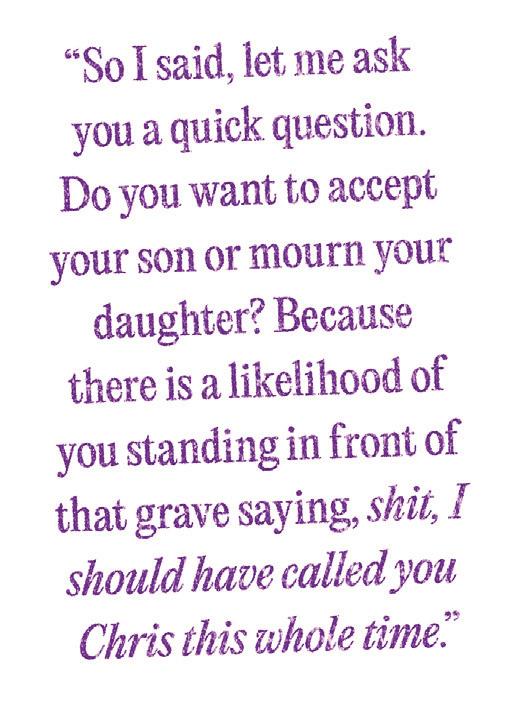

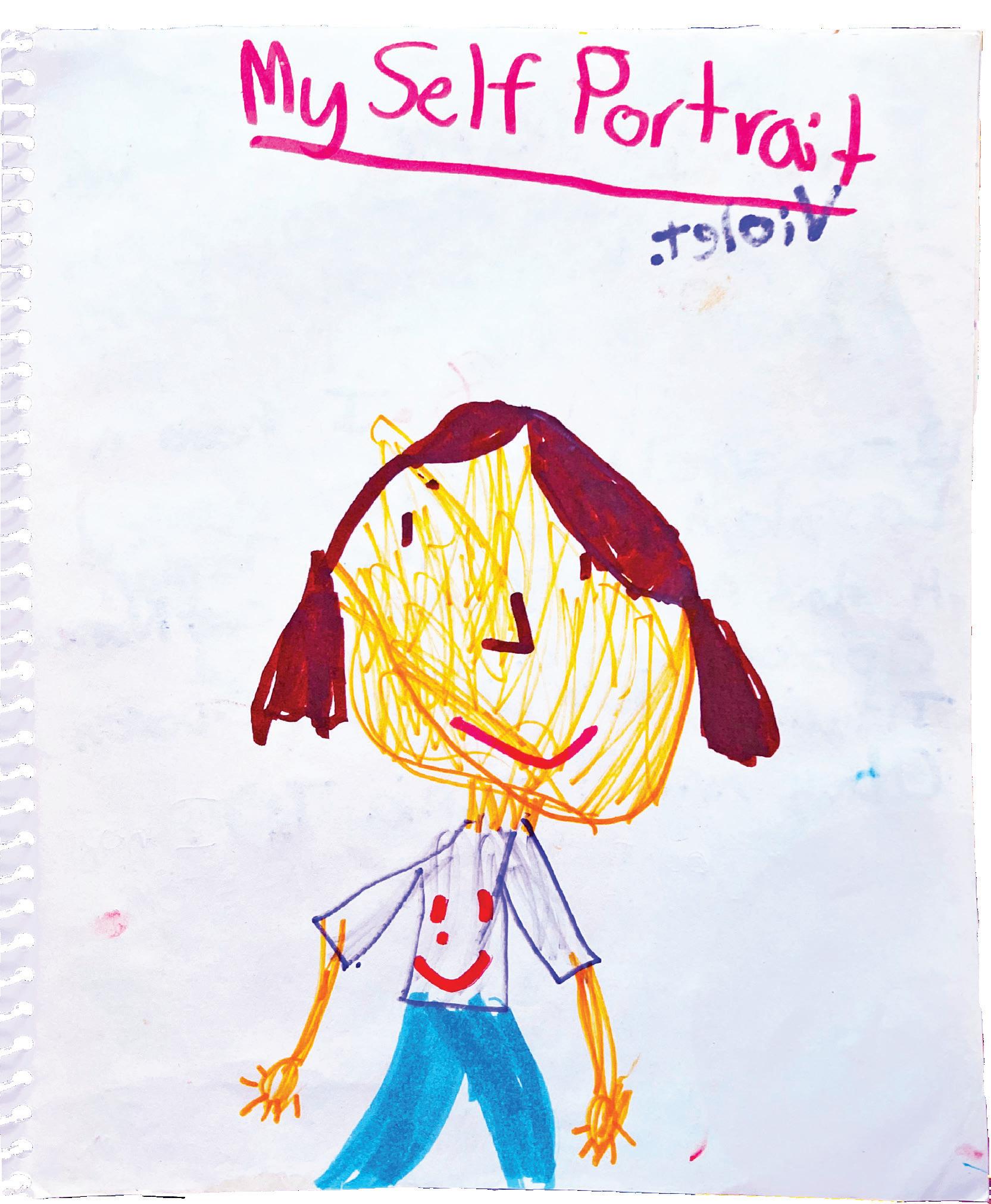

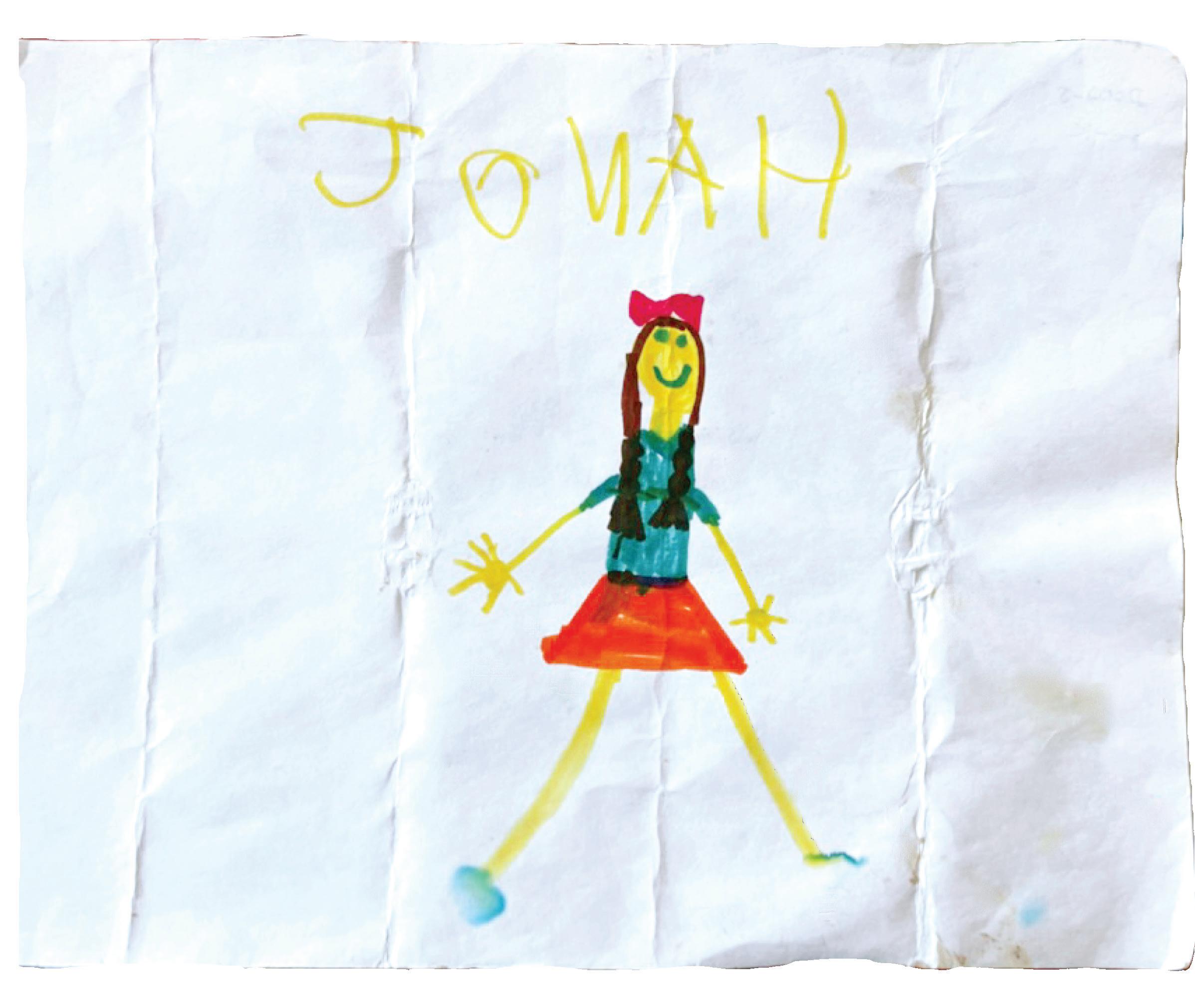

Drawing it Out

Local advocate Tony Ferraiolo guides trans youth—and their parents—through the complications of their gender journeys.

By Hannah Szabó

Counter Memories

cover story

Is gay nightlife getting quieter? A writer explores the histories inside New Haven gay bars.

By Jabez Choi

Waiting for Care

At the Yale Pediatric Gender Program, trans kids say they receive great care—but it’s not easy to get.

By Theia Chatelle and Iz Klemmer

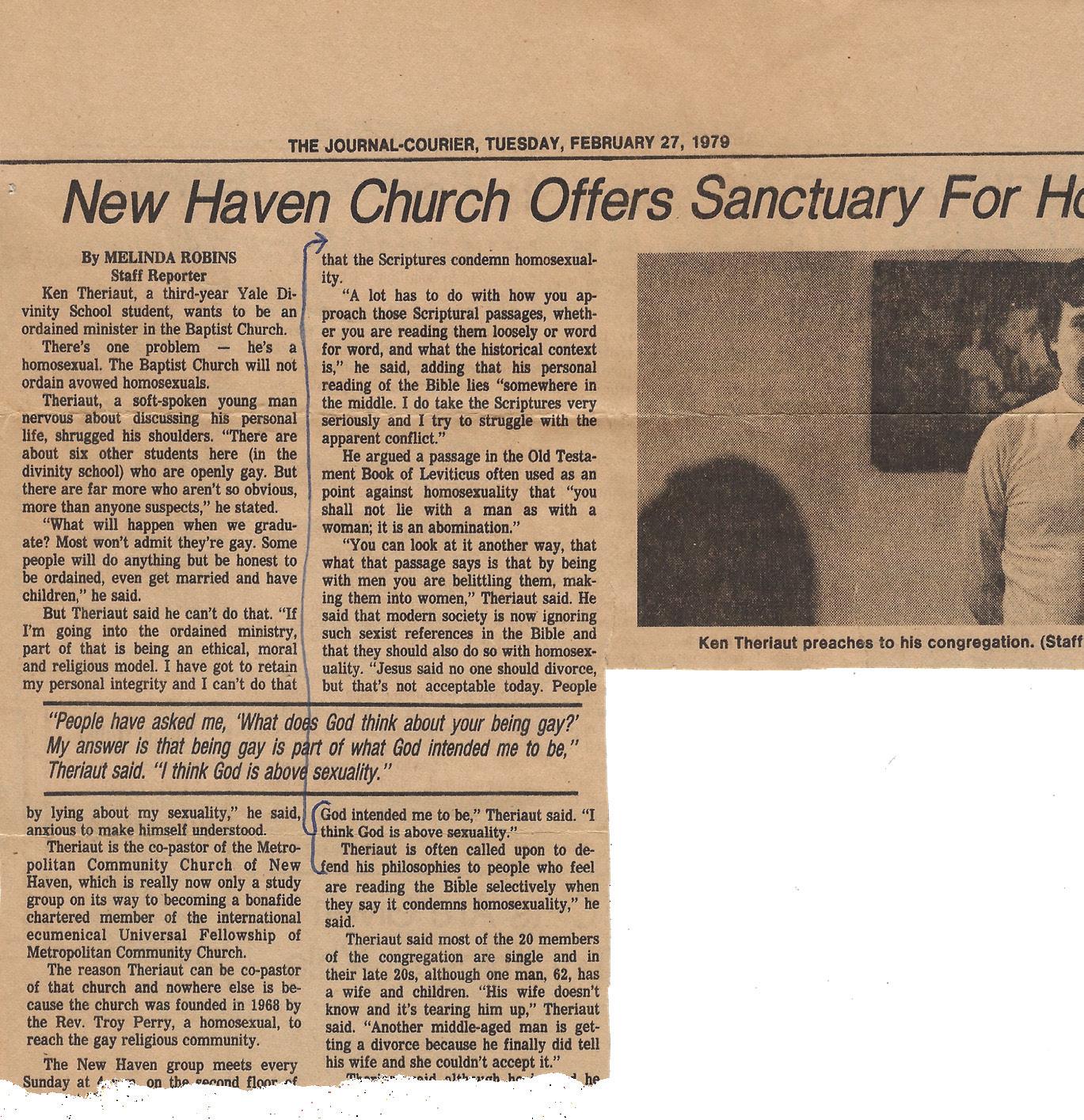

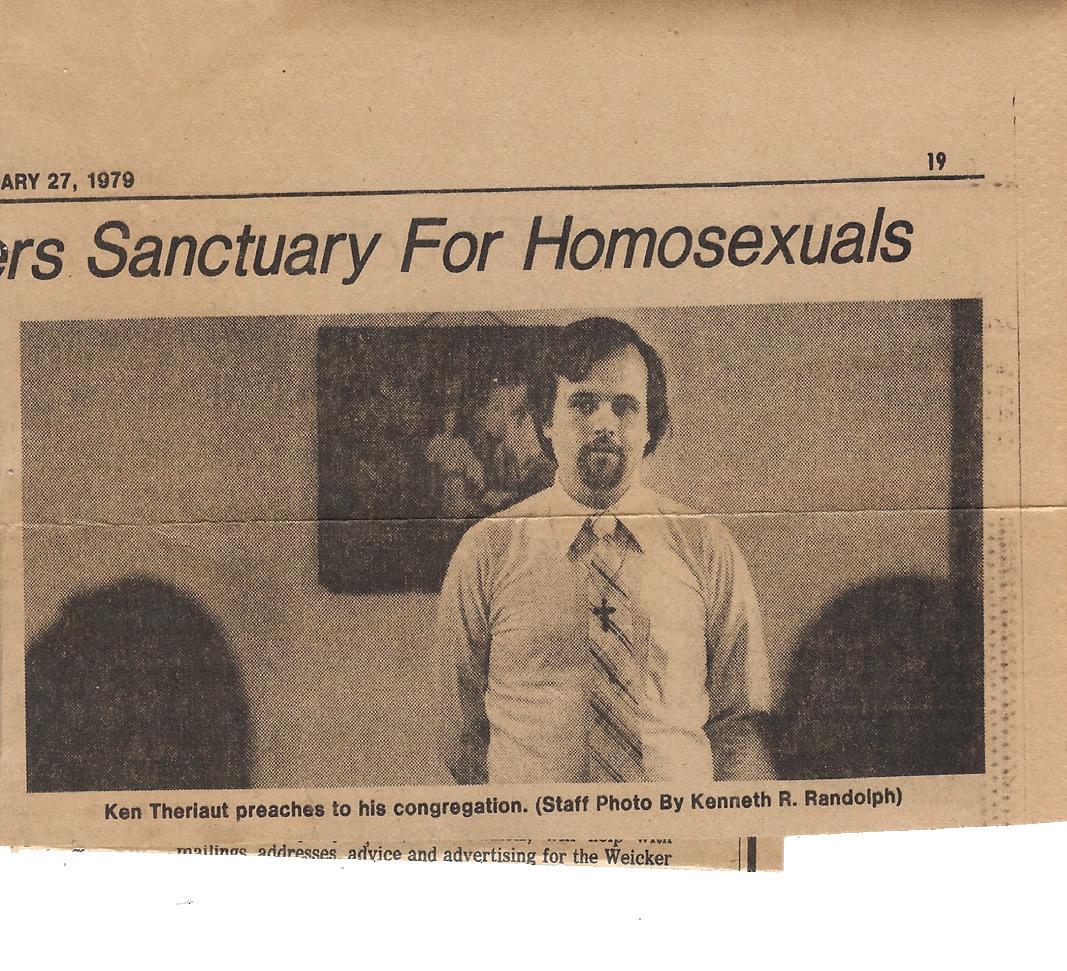

Coming Out, Coming Home

Queer Christians in New Haven and at Yale are finding ways to enrich their spiritual lives through their lgbtq + identities.

By Abbey Kim

By Abbey Kim

We Will Live in a Corner House

By Anaiis Rios-Kasoga

asides

Jennifer’s Body

By Anaiis Rios-Kasoga

Dash of Fancy

By Amal Biskin

poems for Abel

By J.D. Wright

Where Boys Become Men

Violence and masculinity in the Singapore Armed Forces.

By Jools Fu

Grocery Store

By Amal Biskin

Berlin Poem for Owen

By Ella Goldblum

Kissing One of Your Queer Awakenings

By Adrian Elizalde

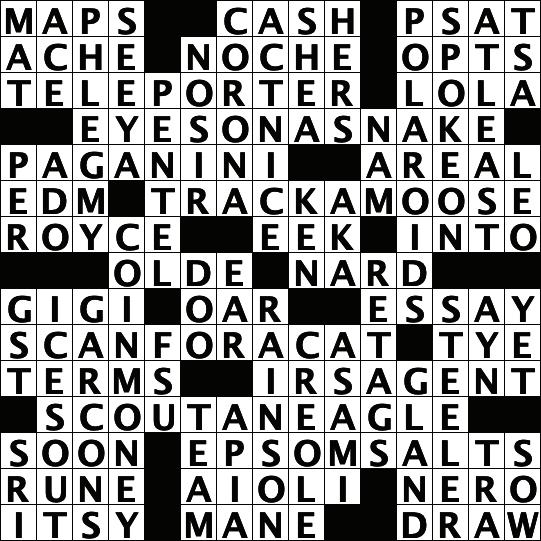

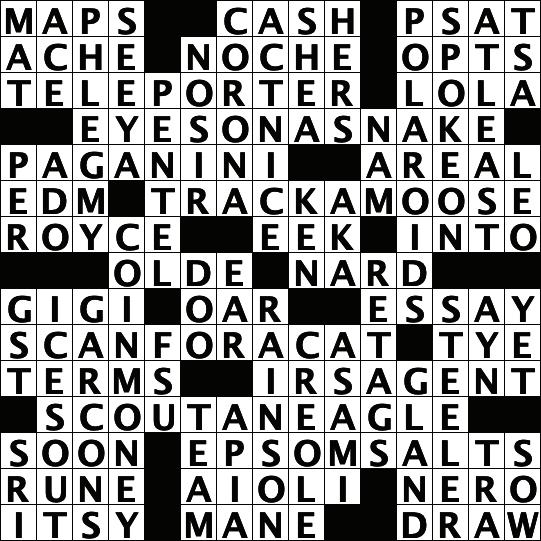

crossword

**REDACTED**, crossword , by Jesse Goodman, page 55.

3

fiction

flash

March 2023 Contents 42 16 4 6 10 28 53 33 54 14 9 14 40

point of departure

personal essay

image credits: Nour tantush; kevin chen; aaron miller 34

A Scene of Outsiders

At Space Ballroom, Danya Blokh is in for a night of “non-denominational, non-binary” hardcore.

On February 12, 2023, Hamden’s Space Ballroom was a veritable convention of musical subgenres. Millennial hardcore fans in gray hoodies with the hoods up, older bearded metalheads wearing band T-shirts, and young queer punks with piercings and tattoos milled about the small, dim venue. The crowd’s energy felt more like a school dance than a punk show, and even though small mosh pits formed for hard-hitting local hardcore bands Intercourse and Kidnapped, they fizzled out quickly once it became clear that most fans preferred watching to dancing. As a casual fan of hardcore who had always enjoyed the collective catharsis of a good mosh-pit, I came toward the front of the audience and hoped for some mayhem as the headliner, Space Camp, ascended to the stage.

I got mayhem, alright. June Aino and Daisy Josefa, the two vocalists and core members of Space Camp, led a plethora of supporting musicians up to the platform, packing the small stage with an upright bass, a cello, a sousaphone, a trombone, a synth and a drum set, with a second drummer set up in the middle of the audience. The musicians smiled broadly as they sound checked, their classical instruments contrasting starkly with their tattooed arms and all-black outfits. But nothing could have prepared me for the overwhelming cacophony of orchestral punk that followed. Somehow, with no guitar or bass, Space Camp’s music was more forceful than any punk band I’d heard.

With the drummer in the middle of the crowd, there wasn’t any room to

start a mosh pit. But there was no need for one; the crowd’s attention was fixated on the hardcore symphony before us. The chaos I’d expected in the audience was happening on stage instead: June and Daisy screamed powerfully, the brass instruments boomed, and the second drummer wielded a drill during one song and a bugle horn during another. One local reviewer noted in their article about the concert that the sheer force of Space Camp’s sound shattered a lightbulb in the bathroom, but no one around me blinked an eye. As one of the attendees, Connecticut resident Myles Vincent, phrased it afterwards, “it’s just an explosion. Rather than going to see a band go to play their songs, it’s like you’re going to see something go down.”

Brass instruments and power tools are rare at most live shows, but particularly in hardcore, an aggressive offshoot of punk music with a relatively strict sound and ethos. While the genre varies between bands and over time, there is nonetheless a defined set of expectations for hardcore songs: fast and brutal riffs, deeply screamed vocals, and climactic song sections called “breakdowns” intended to make listeners go wild in the mosh pit. Historically, hardcore’s aggressive attitude, as well as its lyrical preference for themes like hometown pride and the straight-edge lifestyle over the progressive politics of anarchist bands, attracted mostly male musicians and listeners to hardcore shows. Space Camp’s novel sound, which their bio calls “non-denominational, non-binary hardcore,” is unique in a genre as stylistically codified as hardcore. Consequently, whenever they’re booked on a show with a bunch of hardcore bands, “it’s a mixed bill, because we have single handedly mixed the bill,” says Daisy.

Yet this very love for instrumental play created Space Camp in the first place. June and Daisy became friends in fourth grade after finding themselves to be among the few fourth graders registered to learn trombone at their South Windsor Elementary School. “Our houses were so close together that we could walk through a neighborhood and some woods and be at each other’s houses,” says June when I speak with the band a few days after the show. Daisy started playing guitar and drums, while June kept learning trombone and picked up keys, and they briefly experimented with surf rock in high school before

officially forming Space Camp in March 2013. Their playful debut record consists of Daisy playing drums, June playing synth, and a friend reading passages aloud from books they found in their practice space. “At the time we were like, this is a cool concept,” says Daisy. “It’s since been wiped from the internet.”

In 2014, the band added a bassist, June introduced a full piano in addition to their microKORG synth, and Space Camp began booking more shows and seriously recording music. Their stylistic influences at the time were hardcore bands like Ceremony, Punch, and Code Orange Kids, whose influence is still evident in Space Camp’s roughly screamed vocals, ominously dissonant chords, and punchy song sections. “We’ve always been suckers for a lip-curling hardcore breakdown,” Daisy tells me. Yet instrumental diversity remained integral to their ethos; listening through their Bandcamp releases, you’ll hear just about everything—tuba, guitar, contrabass, oboe—all absorbed into their heavy punk sound. Their latest album Gold Star was released in January of this year and continues this tradition with twenty-nine minutes of magnificent auditory havoc.

Space Camp’s take on hardcore has thrived in Connecticut largely because of the state’s unique music scene. Whereas more densely populated states tend to stratify into separate subgenres with minimal overlap, Connecticut’s small size leads to a melding of styles perfect for Space Camp’ eclectic blend of genres. As Daisy says, there’s a distinct charm to a place where only one show is happening on a given night: “If it’s a Friday night in Philadelphia in July, there’s six shows going on. You can get the best line-up at a sick venue, and everyone you know will still text you and say, sorry, we’re going to another show. But if we’re playing in Connecticut, everyone who’s interested is there, it is the thing to do.”

4 March 2023 TheNewJournal Points of Departure

illustrations by meg buzbee

Space Camp is only one example of Connecticut bands’ propensity for music experimentation. Tarek, the lead singer of Intercourse, says there’s an entire scene of local experimental punk—“I call it outsider hardcore ”—dedicated to fostering a left-leaning, welcoming milieu opposed to the exclusivity of more regimented music scenes. “We’re not into that macho, gatekeepy shit,” he says proudly. Intercourse, which has been playing since 2014 and is soon releasing their new album Halo Castration Institute, is itself a genre-bending project too, with “one foot in hardcore and one foot in noise rock.”

The Connecticut scene’s inclusivity doesn’t just apply to the music, but also to the community itself. While hardcore is often perceived as a hypermasculine boy’s club, Connecticut’s outsider hardcore shows are “a place for a lot of people where they can go and be themselves,” says Tarek. “If you want to wear make-up and goth out, no one’s gonna bat an eye.” Tarek, whose family is Egyptian, grew up as one of the only people of color in the small town of Naugatuck, Connecticut. His upbringing was full of alienating and aggressive encounters with white

schoolmates. Connecticut’s music scene was also exclusionary, though in different ways. “People at shows used to tell me, don’t wear a Marilyn Manson shirt or you’ll get the shit beat out of you, make sure to wear a Cannibal Corpse shirt or something neutral,” Tarek remembers, laughing. Yet the young, left-leaning audience of Connecticut’s current outsider hardcore scene makes no space for such hostility, from musical elitism to racism and misogyny. “There’s lots of trans people, there’s lots of queer people, there’s lots of people of color. This is a really inclusive scene for everybody, and we’re really proud of that. We’ve had people come through and say, wow, this little niche of Connecticut is really special.”

This warm and welcoming attitude suffused the venue after Space Camp’s set concluded. Young newcomers to the scene and longtime outsider hardcore fans alike chatted eagerly with me about what we’d just experienced together and about other shows they’d recently attended. If the disparate contingents had struggled to gel at the start of the night, the singular intensity of Space Camp’s eclectic sound seemed to have bonded everyone at the Space Ballroom, dissolving any residual awkwardness in the space.

I shook hands with Daisy and Tarek, who both warmly thanked me

for coming and told me they’d be glad to interview. In the merch line, one fan told me he’d grown up in Connecticut, moved to Austin for nearly a decade, and only just returned. The scene in his time had been aggressive and intimidating, he told me, and the warmth of Space Ballroom’s crowd shocked him. Though this was his first time seeing Space Camp, his beaming smile while talking about his experience at the concert suggested he was bound to become an outsider hardcore regular.

I left with a newly purchased Space Camp T-shirt tucked under my arm. Every time I’ve worn it since, at least one person has stopped me to ask if I caught them at Space Ballroom. Daisy was right about the perks of a small music scene; these people really had all been to the same show as me. The next time I find myself toppled over in a Connecticut hardcore mosh pit, I’m certain one of these familiar faces will be around to lift me up. ∎

Points of Departure

Danya Blokh is a junior in Timothy Dwight College.

285 Nicoll Street, New Haven CT 06511 203-936-9446 www.mactivity.com Fitness Center

Title illustration: Space Camp’s June Aino, left, and Daisy Josefa, right.

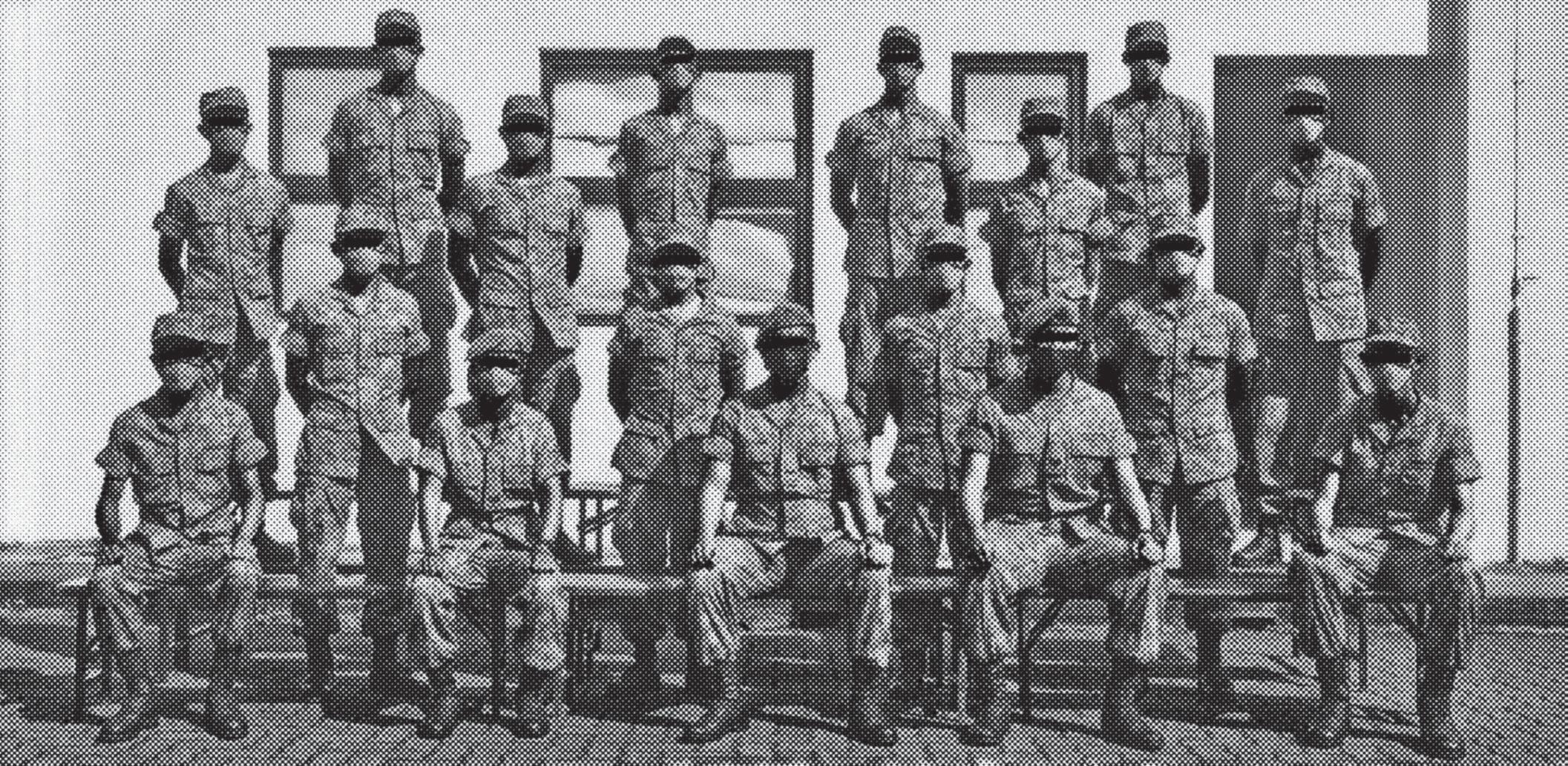

Where Boys Become Men

Violence and masculinity in the Singapore Armed Forces.

By Jools Fu

By Jools Fu

Content warning: This piece contains a description of self-harm.

My combat boots were still flecked with dirt and my forest-green fatigues were covered in mud and sweat. Somehow, my beret sustained its creases despite soaking up the bits of camouflage face paint that I hadn’t managed to properly wash off. The city was dead quiet. It was 3 a.m., my phone was out of battery, and I had to walk home from the hospital.

My nineteen-year-old recruit, Bing Jie, was hooked up to an IV and probably fast asleep. Two months ago at this time, he probably would’ve been at home, awake maybe, playing video games, watching TV. At the time when he first enlisted, he told me, he was a professional League of Legends player. He had come fourth in a national competition the year before. In terms of national service, he really wanted to serve in the cyber security division. Instead, he was tossed into infantry, and he came under my charge. Rhabdomyolysis had

broken down his major muscles. Now, he couldn’t walk without excruciating pain in both legs. The moment when he had collapsed into a messy heap of limbs and grass, he couldn’t even call out for help.

While we were in the waiting room, Bing Jie’s dad and older brother arrived. After a terse conversation with me, they sat with him on the other side of the room, away from me. They tried their best not to talk to me directly, and neither of them used my name. I was “sergeant,” a tool of the state’s military apparatus.

6 March 2023 TheNewJournal

Personal Essay

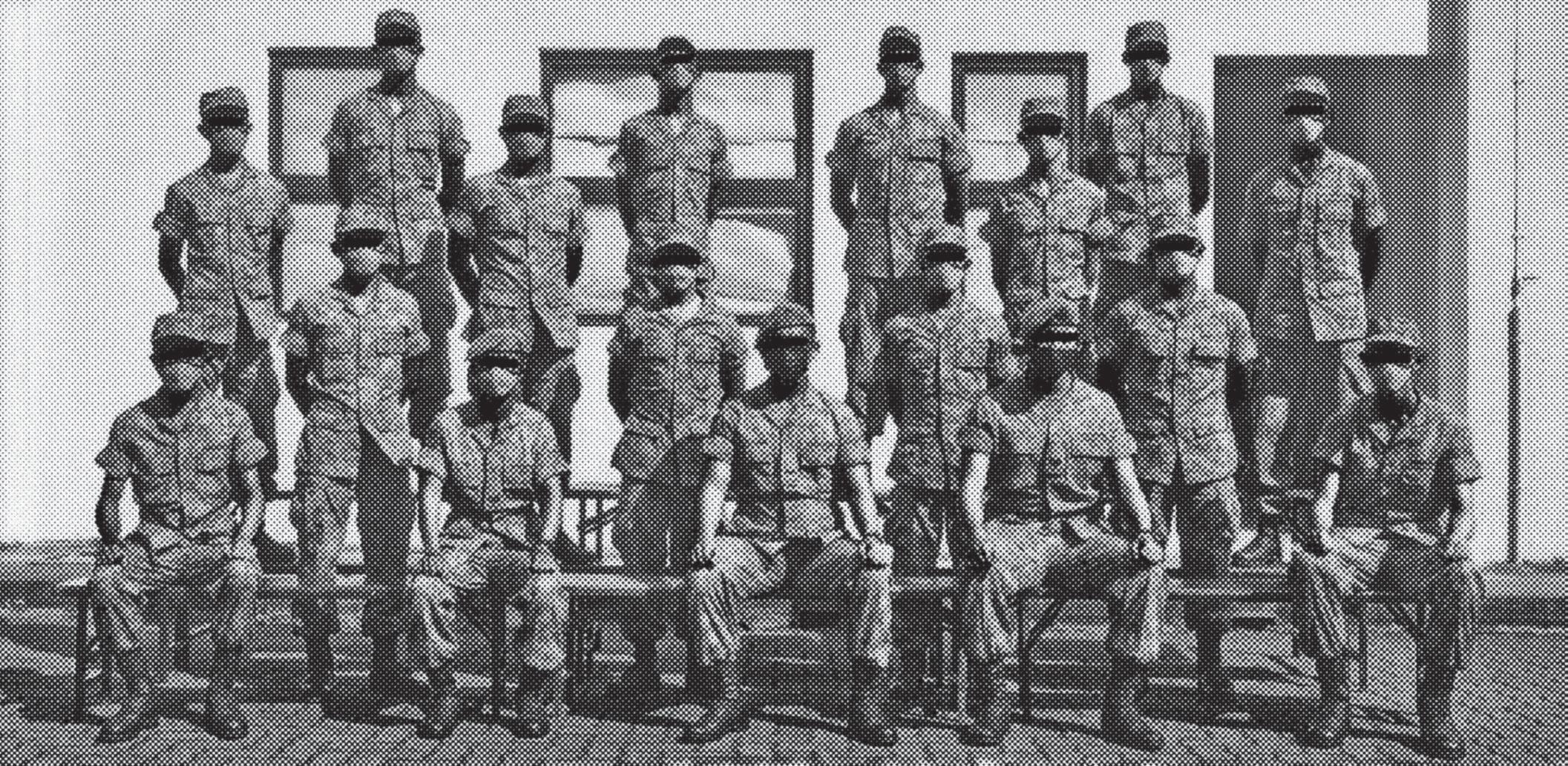

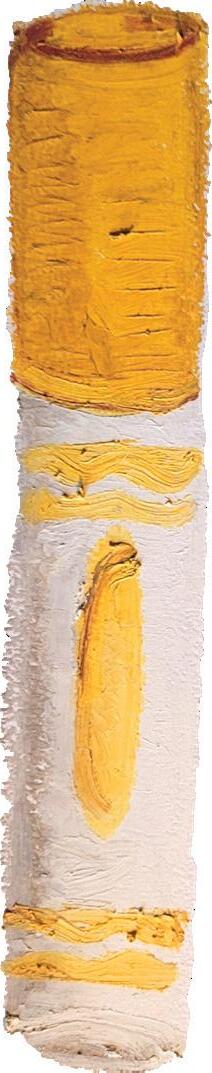

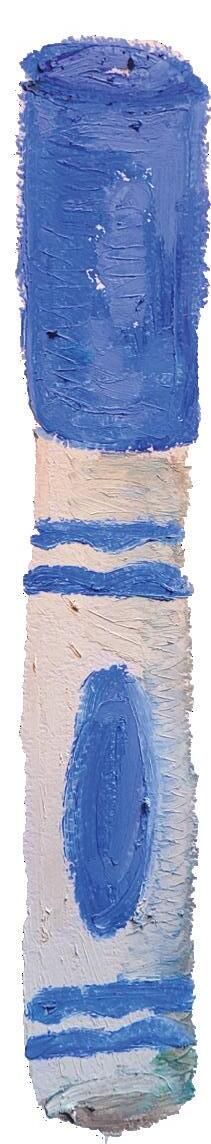

photos by jools fu

Basic Military Training (BMT) is a milestone in the lives of all Singaporean men. It marks their mandatory enlistment into the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF). The training center isn’t even on the mainland; boys are packed onto ferries and shipped to Pulau Tekong, an island right off the coast of Singapore. It’s where their identification cards are exchanged, and suddenly they are no longer “citizens” but “NSF” (Fulltime National Servicemen). It’s where the SAF shaves the boys’ heads and the tropical sun burns their scalps. It’s where they fire their first rifle, where they dig their first trench, and where they start the endless cycle of physical and strategic combat training. After two months of grueling regimentation, recruits graduate and are then assigned to military vocations. The top 20 percent of recruits are sent to command school to undergo further combat training, Officer Cadet School (OCS) to become an officer, or Specialist Cadet School (SCS) to become a sergeant. But BMT is the start of any military career. Its motto: “Where boys become men.”

I entered BMT as an 18-year-old, having gone to high school in the United Kingdom and therefore largely unfamiliar with Singaporean society. National Service had always been something I dreaded. All throughout high school I had been bullied by other boys, who called me a “faggot” and kicked me when teachers weren’t looking. I was often reduced to tears, made to feel unfathomably small, and helplessly alone. If high school was like that, I couldn’t imagine what the army would be like. I considered myself a progressive, I thought militaries shouldn’t exist, and I knew my queerness was not accepted. I made the conscious choice to remain closeted. I enlisted with the bold assumption that the army was not going to change me or my beliefs. But to avoid being criticized or belittled, I tried my best to excel in this performance of masculinity.

I did well. My athleticism translated well to military training. I accepted the torrent of insults and verbal abuses my sergeants hurled at me. And when I was commended for my abilities, a part of me truly enjoyed it. For the first time in my life, I was considered tough and strong. I completed BMT fifth in my platoon of sixty-four, and I earned a position in SCS. A week later, I started my training to become a sergeant and a commander.

In SCS, I spent six months learning

more advanced forms of combat and familiarizing myself with a diverse array of weapons, from machine guns to RPGs. I navigated miles of dense vegetation while carrying a seventy-pound field pack. I survived in the jungle for nine days without any contact with the outside world. With the completion of each exercise, the joy I found in the military became more real. I enjoyed infantry training in a way that would have been entirely alien less than a year before, intoxicated with my adaptation to an ideal masculinity. When I graduated, I was assigned to be a BMT trainer. Upon receiving my posting order, I promised myself I would be different, patient. “Be the change you want to see” was what I kept repeating to myself.

I remember the first time I made another person cry. He was part of the

alienated. I was barely sleeping, and I hardly had time to eat. So, when I caught a glimpse of a recruit running out of his bunk to grab an extra bun from the parade square after lights out, I lost it. What came out was closer to barking than yelling, and it echoed so loudly that some heads peeked out from the fifth floor. “What the fuck do you think you’re doing?” He dropped the bun instantly, keeping his head down as I unleashed my wild wrath on him. As he walked away, I realized the blotches on his shirt were not sweat marks, but tears. When I reentered the company office, my friends and fellow commanders dapped me up. Later, my captain pulled me aside and commended me for enforcing discipline. As I went back to my bunk, I smiled for the first time in a while.

first batch of recruits I ever trained. In the first few weeks of their training, the recruits are given snacks to eat at night, as a part of their grace period: packaged buns, stuffed with artificially flavored cream the color and texture of playdough. The buns tasted like nothing but sugar, which was pure heaven compared to the nauseating food that we ate at the cookhouse. I’d had a rough day—contrary to my expectations, being a trainer was not simple and I was growing more and more frustrated with how ineffective I felt. My strategy of patience seemed completely inept compared to the fear other commanders were able to strike into their recruits. As much as I wanted to be morally strong, I felt myself becoming

Bing Jie was in my third and final batch of recruits. By then, I had grown into a seasoned trainer. I had learned to harness my unbridled fury on my recruits, breaking them down physically and mentally into passive bodies, moldable soldiers. My rage was a defense mechanism, a way to throw others off my trail. If I could be “tough” and harsh on my recruits, no one, not even the boys from high school, could call me a “faggot” anymore. Before enlistment, a batch is given a grade based on their expected physical and mental competency. My first two batches had been A’s; Bing Jie’s was a C, and I felt the difference immediately. No matter how hard I pushed, they couldn’t meet my timings. They were consistently late, none of them could perform any marching drills in sync, some couldn’t even hold up a rifle without shaking from the effort. It was a combination of physical inability and mental disinterest. But I had to be the one that got them there.

The Combat Circuit is BMT ’s most difficult physical training. It requires recruits to dress in full battalion order, including field packs, suffocating armored vests, and heavy helmets. Then, they’re thrown into an outdoor training ground, made to climb steep hills, dash from tree to tree, and crawl through thick mud. The exercise is supposed to simulate the motions of jungle warfare. When I was a recruit, our sergeant shouted insults at us as we did the circuit, and I did the same to my recruits. Nothing was off limits. I was telling them how worthless they were as they scrambled about, their rifles swinging

7 TheNewJournal March 2023

layout design by Kevin Chen

wildly by their neck, knocking into their chins. Suddenly someone shouted out in alarm. Bing Jie had disintegrated into a crumpled heap underneath his field pack, which was larger than him. I thought he was faking it. Three hours later, after the medical staff had evaluated he needed to be sent to a hospital, I volunteered to go.

My commanding officer gave me the next few days off, and my house wasn’t far from the hospital. Under moonlight, the quiet roads felt like burgeoning gulfs. I reached into my pocket to find a crushed pack of Marlboro Reds for a smoke, a habit I had picked up in SCS, but I couldn’t find my lighter. Somewhere along the way, a car drove past me, its headlights illuminating my dirty silhouette against an empty shopping mall. At the sight

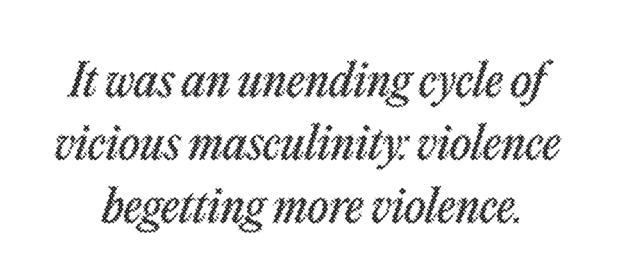

of me, the driver was startled. I felt like a ghost from the jungle, a savage specter haunting the city. About a mile from my house, I passed by the twenty-four-hour McDonalds that I used to beg my mum to take me to when I was a kid. A group of drunk teenage boys was there, trying to scale the attached playground. I was reminded of combat obstacle courses. In a couple years at most, they too would be starting BMT, like I had, like Bing Jie did, like all of us would. It was an unending cycle of vicious masculinity: violence begetting more violence. Staring at them, I felt a shuddering discomfort. I averted my eyes and walked home.

In the next two months, I graduated from the military and arrived at Yale. On my first night out in New Haven, my combat boots soaked up sticky concoctions of beer, vodka, and fruit

mixers instead of the squelching dirt, dead leaves, and rifle shells of the jungle floor. As I danced in the middle of the sloshing crowd, a group of men snaked their way in, bluntly pushing through me. A couple months prior, I would’ve shoved back, maybe more. But, something had shifted since that night walk. To protect myself, I had adopted the violent tools of those before me, leaving Bing Jie in the hospital. Performing masculinity had not caused more harm. So I simply stared at them, not wanting to engage anymore.

I thought that I’d find solace in queer spaces, because it was the first time I could be so open about my own queerness. At an Office of LGBTQ Resources mixer, I was handed a nametag. “What do I write here?” I asked someone. “Your pronouns!” they answered. I tentatively put down “he/him,” unsure if it was

8 March 2023 TheNewJournal

Where Boys Become Men

who I wanted to be anymore, but equally terrified of the alternative. The group shared their collective trauma: the ways in which they were shunned, bullied, and derided for their difference, largely by the men in their lives. I thought about every punishment I had ever subjected my recruits to. With each anecdote getting heavier and heavier, I left early, ashamed of myself. I hadn’t said a word to anyone.

I felt helplessly alone those first few months, but I refused to ask for help. On Halloween night, while everyone around me prepared their costumes and left for parties, I laid paralyzed in my dorm. Without thinking, I grabbed a pair of scissors from my table and made around a half-dozen slashes on my forearm. Later that night, one of my suitemates called 911, and I was escorted to the psychiatric ward of Yale New Haven Hospital. While undergoing innumerable administrative, psychological, and medical procedures, what struck me the most was how easily my body fell into the monolithic category of “male.” I kept thinking about my position in the genealogy of manhood that I had known before: from the boys in school, the sergeants that trained me, and finally me to Bing Jie. I didn’t want to be a part of the lineage anymore. When I left the hospital, I walked back to my dormitory in the clear, cold New Haven morning air. The sun was the brightest thing I could see and a part of me strangely felt stable. Being a “man” was eating me alive, so I decided to stop.

In five months, I will have spent more time outside the military than in it. There is always an impulse to romanticize those times: the late night instant noodle parties, the raves we went to on our days off, the satisfying sense of exhaustion after finishing an exercise. I still miss catching crabs off the old bridge that we snuck out to when our recruits were asleep, and the genuine moments of tenderness in between smoke breaks and barking orders. That’s what I instinctively remember about all of it. But the SAF’s commands are all still there, in encrypted WhatsApp messages on my phone. When writing this piece, I spent hours sifting through them. The image of Bing Jie, unable to even crawl in that field, is still there. ∎

Jennifer’s Body

The first time I watch Jennifer’s Body I am a budding adolescent huddled under my comforter during the first few months of the pandemic. Stale bedroom air presses into my lungs while crumbs brush against my unshaven legs. Over the next hour and forty minutes I am overcome by an unfamiliar zeal as I take in the bright outfits, hilarious dialogue, and mid-2000s emo soundtrack that plays while Jennifer Check and her best friend Needy unconvincingly pretend they aren’t in love with each other. The twentieth time I watch the movie is on 35mm at The Roxy in New York during my first summer on my own. I linger at the entrance and smile when I realize I can’t spot a single man. In fact, I am surrounded by women who definitely had a crush on Megan Fox when they were 14. And in the velvet enclosure of the theater, we are teenagers again. The salt and butter of fresh popcorn mingles in the still air. We are suspended in a collective coming of age. We are filled to the brim with the kind of zeal you experience when you are finally seen.

9 TheNewJournal

Jools Fu is a sophomore in Pierson College.

Aside

Anaiis Rios-Kasoga

Snapshot

Yalesbians, Sappho, and the Lesbian Life of the Party

A genealogy of lesbian social spaces at Yale.

By Sasha Carney

Anna tender was “already very out” as bisexual when she came to Yale in 2018. Her first week on campus, she followed the stream of nervous first years to the fraternity houses on High Street, towards what seemed to be the archetypal college party: red Solo cups, a watered-down keg, and unremarkable music shaking the sticky walls. As she relaxed into the party, she began to dance with a girl next to her, letting her hands rest easily on her waist. Half-drunk, and thinking of very little except enjoying the night, Anna kissed her.

“Huge mistake,” she says of the public kiss now. A man leaned in and asked, leering, “Can I join?” They broke apart. Over the next few days, she found that the news of the kiss had spread through her residential college, without her knowledge or consent. People she barely knew “freaked out” at the fact that Anna, with her long hair and more femme style of dress, hadn’t been what they expected of her. A carefree moment turned into a public dissection of her sexuality. “After that,” she says about the party, “I was like, ‘Oh, okay. I get it. This is not a space for me.’”

She stopped going to frat parties, and started befriending more queer women: people she met in classes, her modern dance group, mutual friends, and hookups. Somebody added her to an email list for an organization called “Sappho,” an informal social group that hosted a semesterly party for queer women and nonbinary people. They promised a night out free from the

anxiety that Anna felt at frats. Her sophomore year, she arrived at a “Euphoria”themed party in the basement of the women’s rugby team apartment on Elm Street. This was no Bud Light-ruled rager: attendees adorned themselves with glitter, sipping colorful, intricate cocktails made by student bartender Lauren Lee. She had already started to

in 1987, at least “one in four” students are some kind of gay, lesbian social life is hardly an underground niche. But over the decades, Yale’s lesbians and queer women have wrestled with how to carve out a social life that is safe but still exciting.

1970s: Yalesbians begins

In September 1975, a record twelve women attended a meeting of the Gay Alliance at Yale (GAY), a mostly male discussion and advocacy group. It was the height of the lesbian feminist movement, and some young lesbians were growing frustrated with what they saw as the patriarchal focus of gay activism across the United States. Four years before, the Yale Women’s Center was founded as a space for undergraduate women to gather. In 1970, the activist Del Martin published an essay, “If That’s All There Is” in the lesbian review The Ladder, where she condemned gay rights organizations as sexist. Lesbians—growing doubly frustrated by the homophobia they experienced from straight women and the marginalization within gay spaces—felt they needed a space to breathe.

attend “smaller, more intimate” parties dominated by queer women, from wine nights hosted by girlfriends of friends to a set of lingerie parties hosted by an all-woman society. But Sappho was the largest gathering of queer women she’d seen in one space.

At “the Gay Ivy,” where, according to a Wall Street Journal article published

Two lesbian undergraduates, the out-and-proud Tara Ayres and a partially anonymous woman identified only as “Sarah” by The Yale Daily News, formed a Yale-registered sister group to GAY known as “Yalesbians.” On a balmy September night, twenty lesbians and self-identified “straight woman” allies met for the first time at the GAY room

10 March 2023 TheNewJournal

Lesbians—growing doubly frustrated by the homophobia they experienced from straight women and the marginalization within gay spaces— felt they needed a space to breathe.

in Hendrie Hall. They adopted the format of “consciousness-raising circles,” open feminist discussions where women connected wider political issues to the struggles of their everyday lives. The organization also co-ran multiple projects with GAY, including a telephone counseling service and a weekly radio hour called “Come Out Tonight.”

Yale’s Weekly Bulletin and Calendar initially ignored requests to publicize Yalesbians’ weekly meetings. After a few weeks, they finally responded and began to reluctantly spread the word. Through word of mouth and print ads, membership grew to about one hundred people. As co-founder, Tara noted Yalesbians’ membership was a low estimate of the true proportion of lesbians on campus, arguing in a 1977 report to the Yale Corporation that the average gay woman at Yale “is probably not vocally a lesbian, and is afraid to be identified as such.”

On New Year’s Eve in 1976, a fire destroyed part of Hendrie Hall, burning out the room where Yalesbians and GAY met, as well as the headquarters of the service frat Alpha Psi Omega. While the frat was re-housed almost immediately, the administration dodged Ayres’ inquiries about finding a space for Yalesbians for over a month. In late February, Tara and GAY member Jack Winkler were finally able to march up to the Associate Dean of Student Affairs’ office to secure a new space in Bingham.

Off campus, meanwhile, many lesbians could still find social and political community in the lesbian feminist scene in New Haven. “By the end of the [1970s],” Yale alum and former Yale LGBTQ history professor George Chauncey wrote in The Yale Alumni Magazine, “New Haven was home to an extraordinarily vibrant and complex women’s culture and lesbian feminist movement: the Feminist Union; feminist bookstores, women’s health centers, self-defense classes.” While Yale lesbians (and Yalesbians) found political homes in New Haven’s more radical feminist scene, they often came cleaved closer to campus to party.

1980s: Lesbians after hours

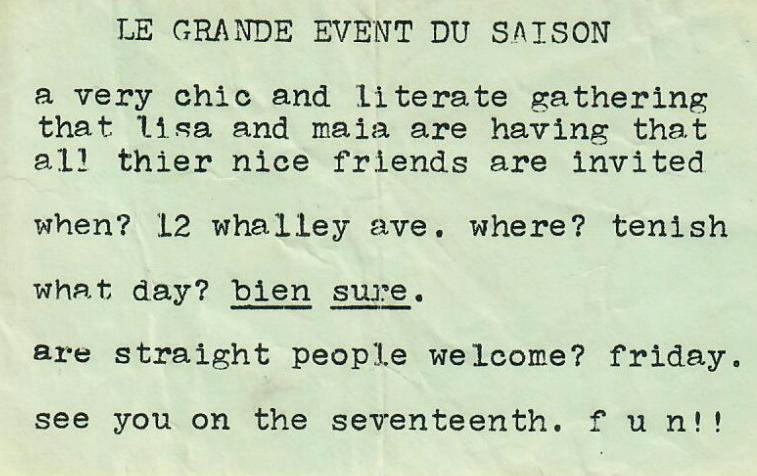

By the late nineteen-seventies and early nineteen-eighties, separatism was no longer the word of the day. Maia Ettinger, a former official leader of Yalesbians, told me that by the nineteen-eighties, the gay “scene” was more

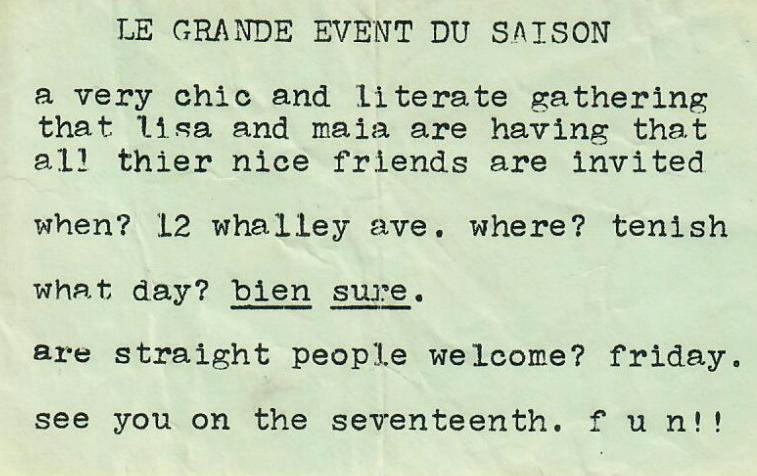

multiracial and cross-gender than the “pretty white” nineteen-seventies separatist world. She moved off-campus to 12 Whalley Avenue, where she lived with fellow Yale gays Judith Rodenbeck, Lisa Kennedy, and the late Donald Suggs, who later became known as a Black gay activist and journalist during his postgraduate life in New York City. While Maia was a leader of on-campus lesbian life at weekly Yalesbian meetings, the household threw after-hours parties that brought campus gays together on more relaxed terms.

Rather than being exclusively lesbian, the household “invited everyone cool, which was cool with us,” explains Maia. Though the parties skewed gay, they allowed proud lesbians and straight lefties alike to dance to Boy George, Annie Lennox, and Prince, who were bringing queer aesthetics and sensibilities into popular music for what felt like the first time.

Listening to Maia sketch out her gay world, I was enthralled by the vibrancy of her social and political life. I also started to wonder how my life would have unfolded on the gay campus of 1982. I certainly wouldn’t have identified as nonbinary the way I do today—Maia confirms that while “androgyny” was the word of the day, and something many campus lesbians pursued, the language just “wasn’t available” to identify outside of womanhood.

Romantic and sexual relationships flourished—most queer women that Maia knew had both casual encounters and long-term girlfriends. On nights out at several gay off-campus apartments, open lesbians made out with the girls who had attended weekday Yalesbians meetings as “straight allies.” The mood was both celebratory and anxious, and increased visibility came at a cost. In 1982, Yale’s LGBT Co-operative held the first Gay and Lesbian Awareness Days (GLAD), which culminated in an on-campus dance for which the administration gave permission. Maia remembers a group of football players had overheard that a girl they knew, someone they certainly didn’t think was gay, was attending.

One athlete stood outside the door, trying to intimidate her, and Maia “just hauled off and punched him in the eye.” She was proud to see him later that week with a black eye. The gays danced on. Hostility continued to accumulate. In February 1984, the senior class threw a party at what is now Grace Hopper College, where the 17-year-old daughter of a Yale faculty member was kicked in the stomach by male students. The men taunted the girl, and the female friends she was dancing with, with chants of “Lesbos!” Susan Arkun, a Yale College student who was verbally harassed at the event, explained to the News that in social spaces she was often met with derision owing to her short dyed hair. “I wish those lesbians would leave so we could tap the keg,” she overheard once. Strangers shouted “Yalesbians!” at her on the street.

Maia freely accepts that in the face of these explosions of homophobia, some of her football player-punching bravado was bluster. She wishes the gay communities on campus had the language

11 TheNewJournal March 2023

layout design by kevin chen

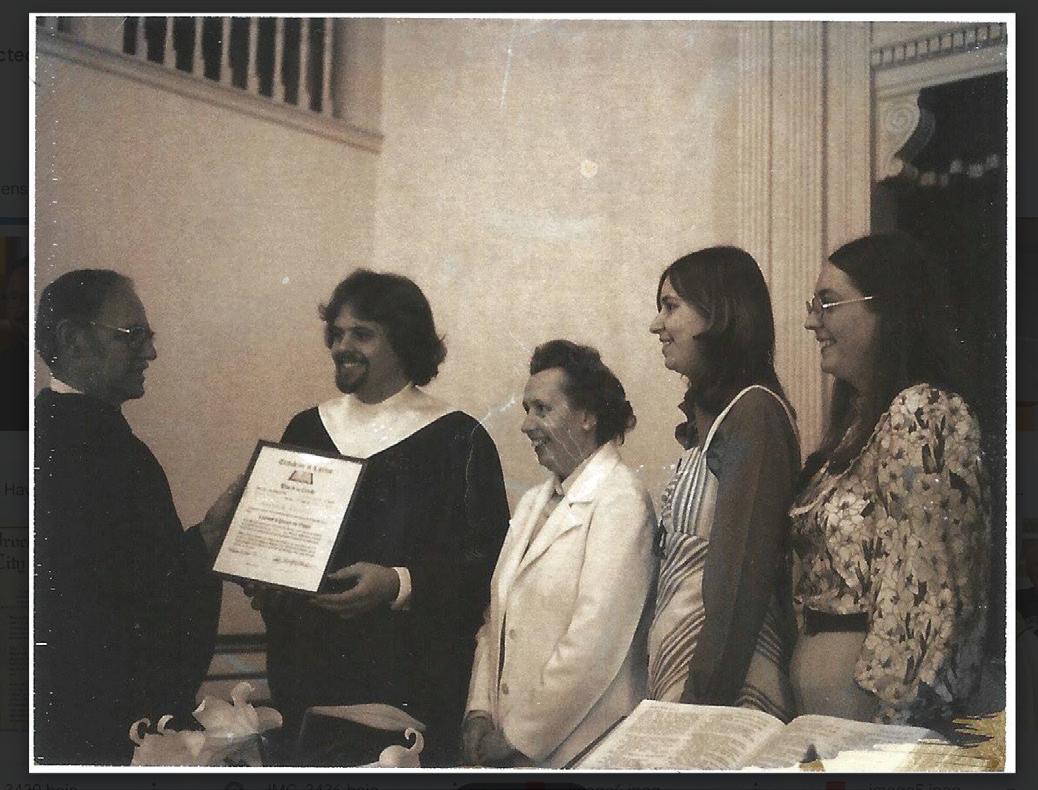

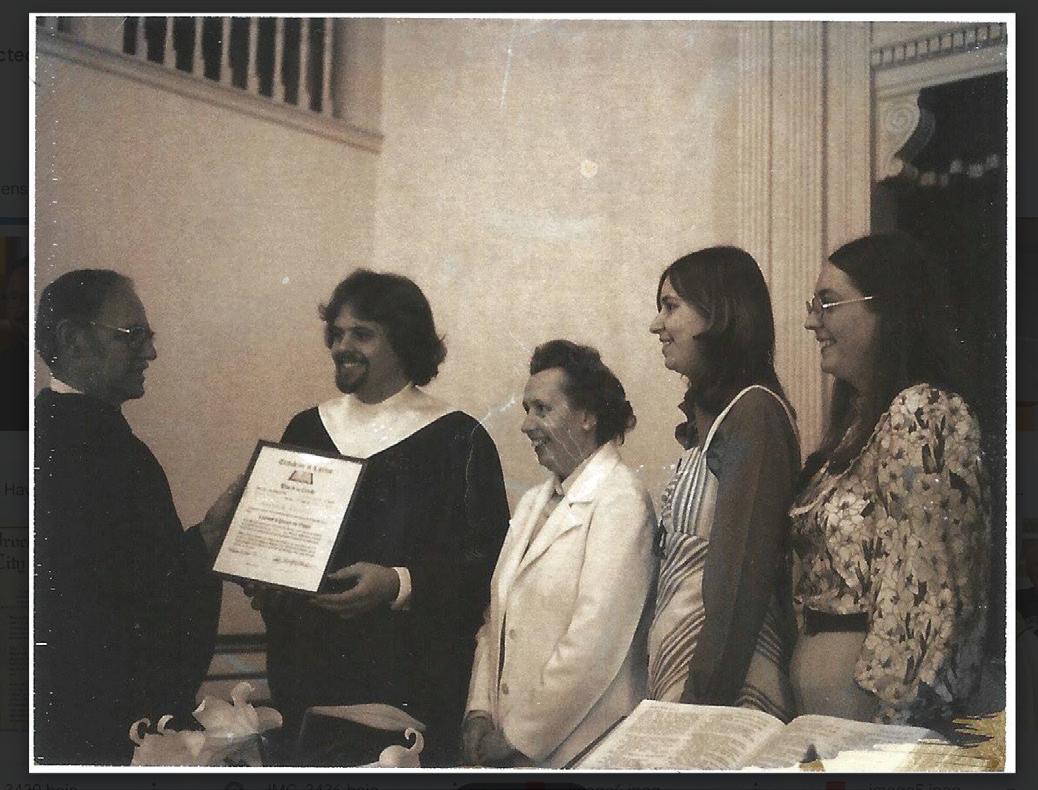

Above: Maia Ettinger and her off-campus “household.” Below: a Yalesbians party invitation.

Photos courtesy of Maia Ettinger

at the time to articulate “how frightened we actually were.” At 18 or 19, she explains, “maybe you access anger more easily than you access your own vulnerability.” Parties are a good way to deflect from the fact that it is often difficult to be young and gay and alive.

Sappho comes out

Yalesbians faded, let down by a quick student body turnover and a lack of institutional memory. The group’s archives were smaller and more informal than a lot of other, larger, official student orgs. Leadership changed hands, over and over again. By the time the third millennium rolled around, Yalesbians’ weekly, Wednesday meetings had stopped. I combed through campus newspaper archives to find some concrete reason for the organization’s dissolution, but came up with nothing. The last mention of the group I could find came in 1995, when the News advertised a regular Yalesbians meeting as part of “Sexuality Awareness Week.”

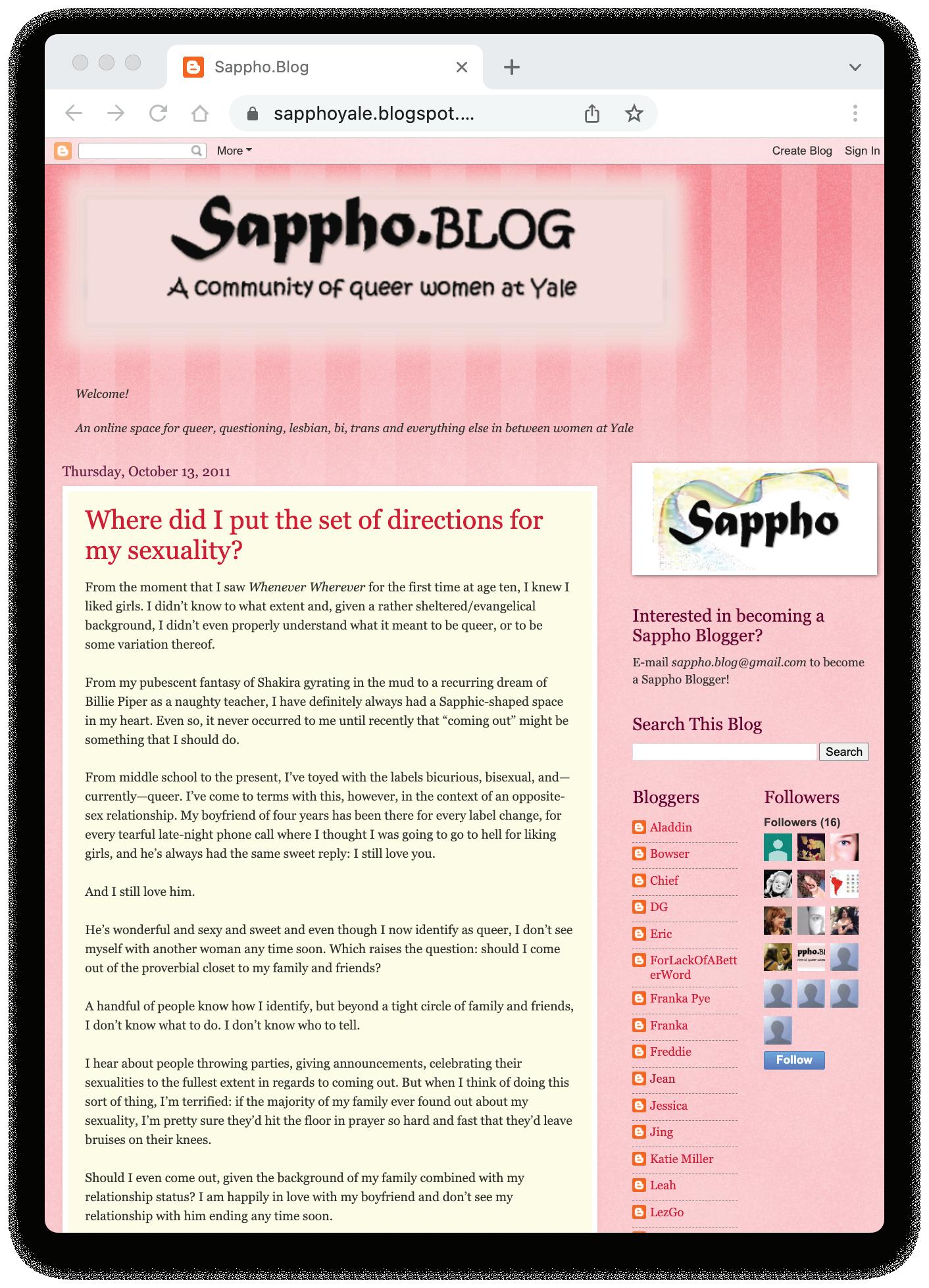

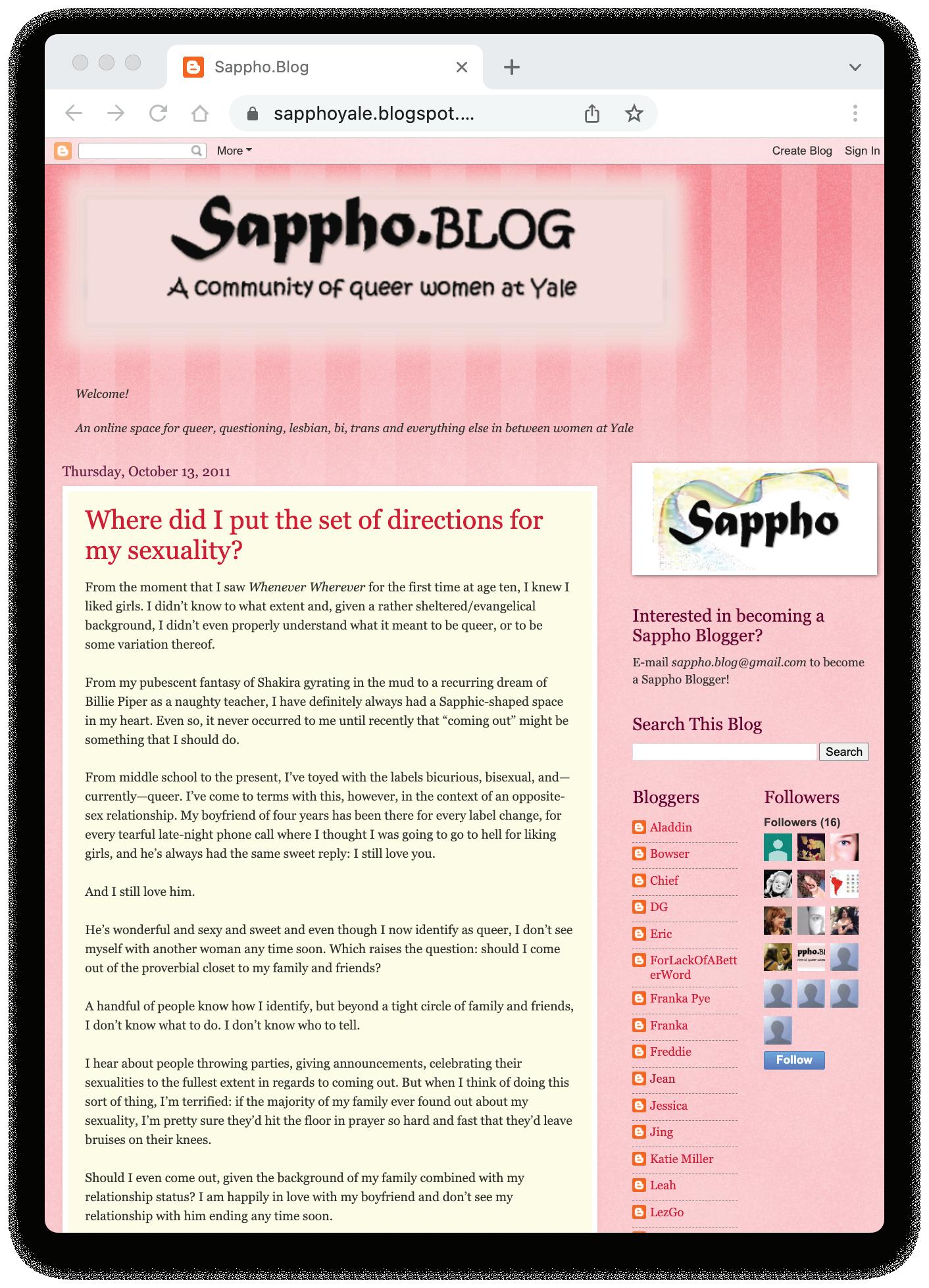

But lesbians, specifically, still wanted a space to come together. Sappho, named after the Greek poetess who gave us the word “lesbian,” was founded by an unknown group of queer women in 2004. Unlike Yalesbians, who were a registered student organization receiving Yale funding, Sappho began—and remained—an informal social collective. Sticking true to Yalesbians’ 1979 declaration to “never again turn to the YDN” to publicize their work, Sappho in 2010 started to reach other on-campus queers in the most 2010 of ways: a blog.

On sapphoyale.blogspot.com, “queer, questioning, lesbian, bi, trans, and everything else in between women at Yale’’ could post, anonymously or not, about anything that came to mind. In the style of full-on early 2010s hyper-enthusiasm, they gushed about their sexual awakenings (“I LOVE TOPPING Eeeeee.”), brought gay political news to the blogosphere (“Yay, queer people can now visit thier [sic] partners in hospitals just like married people!”), and rejoiced over queer pop culture (“how awesome was glee in so many ways? way awesome.”) The blog encompassed the complexities of lesbian social life in the emerging digital age. On the one hand, queer women on campus could now stay connected to each other at all times, even in physical isolation. Dozens of posts popped

up over summer and winter breaks, lamenting homophobic households and celebrating hometown pride parades. But in some ways, with the arrival of the internet, lesbian spaces were also in the process of becoming more isolated, more dispersed. Websites like Tumblr, which flourished in the early 2010s, allowed younger queer people to “come out” under digital aliases, while remaining closeted in their day-to-day life, not taking the risk (and thrill) of venturing into physical queer spaces. Lesbians could raise their consciousness from the

comfort of their home, without looking another queer in the eye.

The blog only lasted a year before being replaced in September 2012 by a series of zines called “Hey Girl!” Perhaps Sappho’s new leadership, tiring of the dispersed nature of the digital, wanted to throw it back to the heyday of analog feminism. The DIY-style zines, frequently thrown together over the span of one night, were a deliberate aesthetic homage to the anarchist, punk, and Riot Grrrl subcultures of the nineteen-eighties and nineteen-nineties. They set out

12 March 2023 TheNewJournal

Yalesbians, Sappho, and the Lesbian Life of the Party

sapphoyale.blogspot.com provided a way for queer women on campus to stay connected amid the emerging digital age.

an ambitious agenda for what Sappho would bring to the “queer ladies’’ of Yale, including guerilla art, skillshares, protests, “parties and pregaymes,” and—supposedly—naked parties in the Yale Women’s Center. The zine was earnest, funny, and pro-Beyonce. One full-page spread of collages and hand-scrawled slogans encouraged readers to “queer up Yale ‘’ in any way they knew how. “GET OUT

THERE! YOU DO YOU!” the caption blared over a drawing of a Venus symbol, a printed-out picture of the Hulk, and an invitation for lesbians everywhere to

“make friends’’ and “make enemies.”

The zine folded after four issues. The idea of “parties and pregaymes” stuck around. Though it’s incredibly difficult to track down the “official” emergence of Sappho parties, in 2014, a Silliman student named Zoe heard, through Facebook groups and word of mouth, about a semesterly party for sapphic people only. The series of Sappho parties, which was funded entirely by the friend groups of juniors who put them on, was “passed down” each year to a new friend group of queer women deemed sufficiently cool,

with enough off-campus space to host. “Everyone seemed to know about it, but I can’t tell you how,” she recalls.

This sense of uncertainty and anonymity, which persisted throughout Sappho’s existence, is a kind of double-edged sword: these social spaces are at once unconstrained by official channels and institutional funding, and difficult to historicize or pin down. Of course, “everyone” can also never entirely encompass “everyone.” Though Sappho invitations were entirely open, most knowledge of the parties, like in Maia’s day, boiled down to who already knew who.

As sophomores, Zoe and her roommates were selected to throw next year’s Sappho parties, but with few guidelines and no funding by the women who came before them. With money they had saved from campus jobs and donations from attendees, they put on a couple successful events where “people were definitely there to hook up.” Zoe recalled these parties as “more mixed-race and more genderfruity” than most other campus parties, and found herself encountering butchness as a possibility she could pursue for the first time. Attendees felt at ease picking up women in ways they didn’t elsewhere on campus—ways Anna didn’t at the frat party her first year. The next year, Zoe and her friends passed the baton to another Silliman friend group. She confesses that she has no idea if they carried it on.

They did, although some people grew frustrated with the slowness of the parties’ semesterly format. “I think we need more parties to cruise at and have sex at,” recent Yale alumnus Mia Arias Tsang told me bluntly. She spent most of her time on campus surrounded by other queer women of color through her work at Broad Recognition, a campus feminist publication. Though she was already in those environments in her day-to-day life, she was looking for more explicitly sexual and romantic lesbian spaces afterhours. She remembers her disappointment at missing a Sappho party in 2017 where attendees reportedly did body shots. Anna both expressed to me that although she wasn’t seeking sex at the parties, being in multiple monogamous relationships through her time at Yale, she enjoyed their distinct atmosphere, at once both electric and celebratory.

When Mia did attend the fall 2019 Sappho party in the rugby basement, she felt a huge “pressure to fuck” owing to how infrequent and unpredictable the

13 TheNewJournal March 2023

Yalesbians, Sappho, and the Lesbian Life of the Party

Pages from the Sappho zine “Hey Girl!”

Sasha Carney / The New Journal

Asides

Dash of Fancy

At seventeen, I devoted myself to the pursuit of eroticism. Evolutionary imperatives necessitated a baseline sexual appetite, but I was more concerned with Sontag. “In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art,” Sontag contends in her 1966 essay “Against Interpretation.” In a miasma of theory, she believed that art had lost its fervor. Now, with heads cocked to analysis, audiences set out on interpretive undertakings at the first twitch of a curtain rising, at the edge of a frame, in the didactic aisles of a title page. We no longer laid ourselves bare and let art wash over us. We no longer felt the acerbic burn when its saline waves seeped into wounds we had forgotten.

I was no different. An erudite floozy, I had taken to reading the wall text before looking at the painting. No longer! With “Against Interpretation” in tow, I set out to let art stir me. Orgasm was the endgame. But like an addict whose senses were dulled by their fix, I could no longer get off on art alone. I craved a hit of theory, chased the electric jolt of recognizing classical allusion. I was Paolo and Francesca in Dante’s fifth Canto, tossed about by blustering waves of desire. Fuck, that was good.

Music was my first exception. If I sat very still in the dark and turned my headphones as loud as they would go, I could start to detect the buds of excitement. Alone in my room, I had no one to tell that Berlioz was quoting the dies irae in the fifth movement of “Symphonie Fantastique.” Instead, I let the crashing gongs throb unanalyzed. I trembled with emotion. I was redeemed.

Amal Biskin

Grocery Store

I learned desire in the aisles of the grocery store. It was a world of pleasure, of throbbing stimulation and tantalizing unknowns. So many things were off-limits: cheese puffs beckoning me with their curved fingers; cookies in perfect rows, glistening through plastic windows; bottles of soda, jewel-like in their translucent vibrancy (surely the liquid itself was not that bright green, I reasoned, and what did a mountain taste like?); rows and rows of cereal boxes like a city on the cutting edge of nightlife, fractal-like in their varieties—this one chocolate and that fruity, this with raisins and that oat clusters, this frosted and that with marshmallows and another frosted and with marshmallows! The hope that these delicacies could one day be mine helped me cope with the profound emptiness I felt knowing that there existed flavors and textures beyond my wildest dreams. With the barebone constituents of my existing culinary experience, I cobbled together succulent fantasies to tide me over until I could satiate myself for real. I imagined frosting so creamy it felt like the softest part of a child’s palm, chocolate so expertly balanced between sweet and bitter it could remain upright on a tightrope, gelatinous candies that my teeth would sink into like they were slipping into sleep.

Amal Biskin

14

parties were. She felt that these opportunities were somewhat scarce, and felt anxious about not taking full advantage of them. “I went with friends who all peeled off and found other people to have sex with,” she recalls. She adds that she was pleasantly surprised by the amount of lesbians of color there, but “at any Yale space,” she acknowledges, “as a queer [woman of color], if you’re trying to get laid, it’s going to be hard.” Still, she came away grateful for the experience, and excited for next semester. But before the next party, Covid hit.

Today: Everyone is gay

As of 2023, “lesbian life” or “queer women’s life” spills out into much of everyday life at Yale. With outness not only encouraged at Yale, but essentially the default in vast swathes of the campus’ academic and social world, many lesbians don’t have to look for “lesbian groups” or “gay issues” to find the comfort and community they seek. “It felt like my life was inherently a queer space in a way I never experienced before college,” Mia explains. Many other queer students echoed this sentiment, feeling that while they variously enjoyed Sappho parties, they didn’t feel the need to attend them to find sex, love, or friendship.

“I don’t think I hang out with anyone who isn’t queer,” Ava Dadvand, an Iranian trans lesbian, decided after thinking for a moment. She finds most of her queer friends through Beyond the Binary, an official on-campus trans and nonbinary social group, as well as through social media, friends of her partner, and other mutual friends. A lot of it is incidental. On an increasingly “out” campus, you can meet other lesbians and sapphic people with ease from a class seminar to the line for lunch. Add in the queer-centric social spaces of Yale Twitter, as well as the opportunities for casual sex and romance from dating apps, and you’re giving Sappho-specific bulletins like Sappho.blog and Hey Girl! a run for their money.

The definition of a “lesbian social space” is also increasingly changing as the idea of “lesbianism” does. While the Sappho of the early 2010s nominally included trans women in the labeling of their organization (if not in the content of their blogs and zines), the language of the world of “lesbians” has become more complex and gender-diverse as medical and social transition become increasingly

possible. Last semester, I had top surgery through Yale Health. Newly healed this semester, I feel more comfortable at parties and excited to dance, but more anxious in things closer to “women’s spaces.” I jump back at the thought of throwing someone off in a bathroom or changing room. I believe “lesbian spaces’’ can, and should, include people like me, but I don’t always feel at ease in those dominated by cisgender, gender-conforming women. The concept of a “lesbian-only” or “woman-only” space can sometimes be code for “cis women-only,” something Maia worried

is bioessentialist. “It’s drilled into our heads, for better or for worse, that lesbianism is associated with pussy.”

While campus “lesbian life” has become more trans, Sappho parties have arguably become less so. After the onset of Covid-19, what events have popped up feel distinctly lackluster. Lily, a senior who started attending Sappho events in 2022, describes the two parties they stopped by simply as “boring.” The music was soft, the drinks were sparse, and the energy was conversational—more of an “affinity group” than a party space. After recently beginning to present more masculine, they were acutely aware that the people they met at a fall 2022 Sappho party were “almost all femmes, and pretty white too.” They headed home early.

Attendance at these last two parties was small, something exemplified by the relative lack of undergraduate knowledge about Sappho. When I asked her about Sappho parties, Ava, who arrived at Yale in 2021, confessed “I don’t know what that is.” The same things that make Sappho exciting, flexible, and cool—the lack of Yale institutional ties or funding, the informality of leadership, word of mouth—also make the whole operation hard to maintain. By the time someone intending to throw a Sappho party has the means to bring their idea to fruition, they may have already graduated. Not to mention, there’s no unified vision behind what makes a Sappho party “good.”

about when I described Sappho parties to her over the phone. “The parties aren’t trans-exclusionary, right?” she asked sharply. I assured her that they weren’t, at least not in their advertising. But it’s certainly possible that some trans people stay away.

Ava is perfectly happy finding a home in what she calls “dyke spaces,” but also notes that she’s found it a lot easier since she had bottom surgery last summer. She concedes that this sounds “bioessentialist” of her, overly focused on genitalia as the site of sexuality. But, after all, she explains, our society

I, for one, don’t want the Sappho party tradition to die out. Lesbian nightlife on campus—the kinds experienced by Ettinger in the nineteen-eighties, or what Anna reveled in as a first-year—is facing a number of challenges. The difficulties of resurrecting marginalized party spaces after Covid, the hesitancy around where exactly to define “lesbianism” or “queer womanhood,” and the uncertainty around whether exclusively gay social life even needs its own space on such a strongly queer campus, all seem to lead people to pause before they send out an invitation to a naked party in the Women’s Center. I say, there’s value in taking the extra, deliberate effort: to carve out a semesterly space, to reach queer women beyond your social group, to confront the contradictions of a lesbian night out. Let the gays dance on. ∎

15 TheNewJournal March 2023

Sasha Carney is a senior in Silliman College.

The definition of a “lesbian social space” is also increasingly changing as the idea of “lesbianism” does.

Yalesbians, Sappho, and the Lesbian Life of the Party

Counter Memories

Is gay nightlife getting quieter?

A writer explores the histories inside New Haven gay bars.

By Jabez Choi

16

17

Layout design by Kevin Chen & photographs by nour tantush

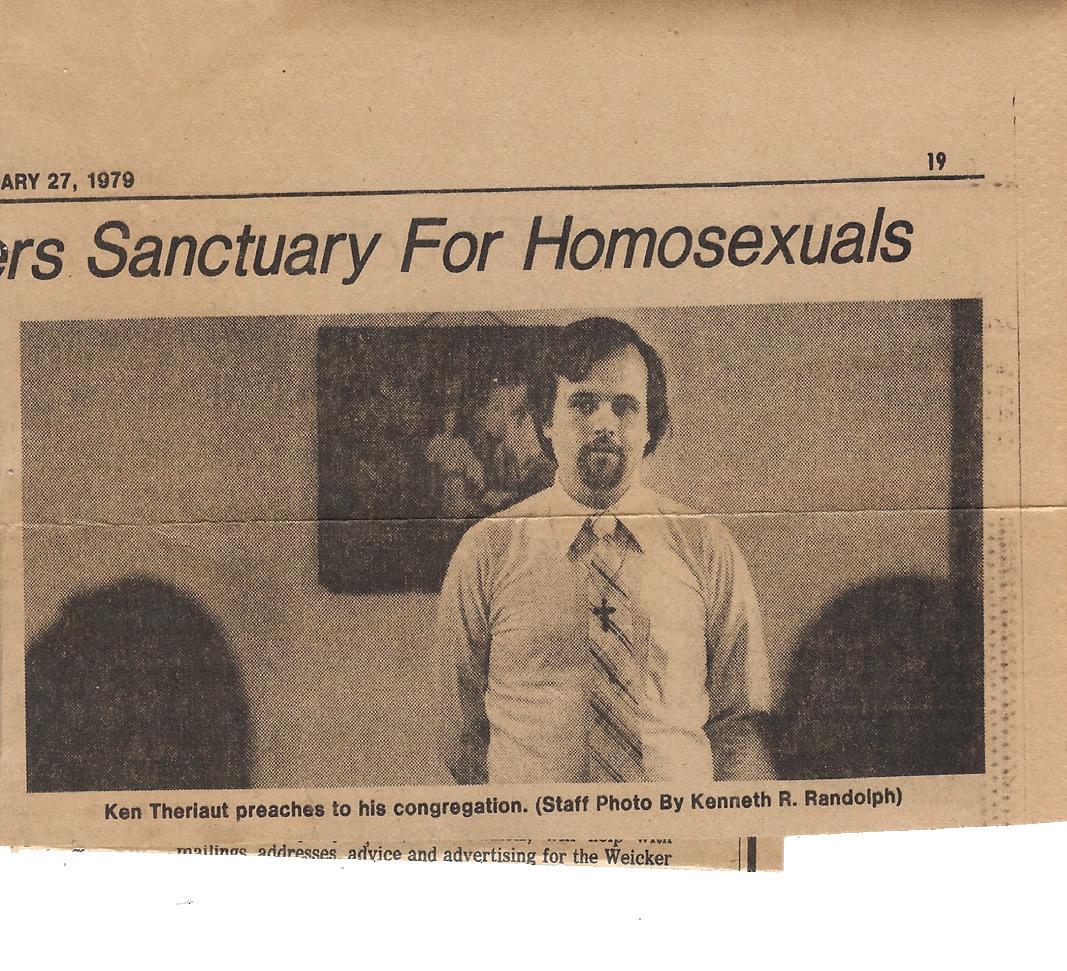

It is a building that looks like it is hiding. Some windows are blurred with frosted glass. Others are boarded up. The walls are painted an aged white, peeling at some parts. On the side of the building, a small, orange sign names the building: Partners. Underneath a piercing streetlight, just next to the mural of a smiling Anne Frank, a man stands by himself, a lit cigarette in his mouth. Nothing on the outside reveals that the building is one of the oldest gay bars in New Haven.

On Fridays and Saturdays, Partners opens its second floor to reveal a glittery night club. There, mirrors cover the walls and a spinning light shines on young, dancing bodies in the dark. Those are the endless nights—loud and hazy and crowded. On Sundays, the second floor closes, leaving the ground floor open for karaoke night. It draws in a smaller crowd. Now, it’s Monday night in February and the bar is barren—except for Paul, me, and two drunk men. The two men had waited outside the bar’s front door before he’d arrived. Now, they sit at the counter with me, babbling over each other. They interrupt Paul while he talks to me, asking for another drink. Paul leaves to fill up their shot glasses.

“I was telling him how annoying it is when people showed up to the bar at seven fifty-nine, knocking on the door,” Paul says, nodding towards me.

They cackle in response.

“If your ass is open at eight, you better be open,” one of them shoots back.

Paul half-smiles. Then, he turns to me and rolls his eyes.

I like Paul for two reasons. The first is that he speaks to me like a friend. By nature, I am an anxious person. Despite this, we quickly chat like two old gossips. The second is that he is seasoned. He moved to New Haven from Massachusetts over a decade ago to work at Partners. This is his eleventh year behind the counter, and it shows—he is fluid, quick with his words. He’s seen more than me.

“So what was the gay bar scene like when you first started working here?” I ask.

“I want to say it was more gay men. Today, we have everything. Like, sometimes I’m working and I’m like, when did this become a straight bar?” he says, pouring another drink for one of the men. “There’s a lot of different types of people that come in and out of here all the time.”

As he talks, these broad terms—“everything,” “different types of people”—become clearer. Paul tells me that Partners defines itself as a gay bar, a gathering ground that has historically served queer people in New Haven. However, the events that the bar hosts—karaoke open-mics, bingo nights, goth dances, drag shows—now draw in straight people alongside the typically queer crowd. It isn’t abnormal to run into straight couples on a Friday night. Partners’ clientele widened over the years; the bar became a space for a broader, open-minded community, rather than a specific queer one. Though these capacities still have queer communities in mind, the formerly rigid boundaries have blurred.

“So the culture of the clientele has changed?” I ask.

“Yeah, absolutely. I mean, it doesn’t ruin the vibes or anything. It’s just that times are changing. Gay bars, straight bars, you’re going anywhere you want,” Paul says. “No one’s really afraid to come here anymore. I mean, ten years ago, the straight men, they’d be like, ‘Oh, my God, I’m not going to a gay bar.’”

I understand. The culture change Paul talks about is something that has manifested in my generation, my lifetime. I was twelve when the Supreme Court recognized gay marriage as a legal right. I watched characters on television proclaim their gayness to accepting arms. I had openly queer friends who I fought and reconciled and grew up with. Whenever I hated myself, I could look at my queer friends and recognize that they were lovable. And through my love for them, I knew I was lovable too. In an odd way, I recognize that my ability to do this is evidence of an undeniable societal shift. Could this shift change landscapes of queer gathering? What happens to a space when the stigmatization that used to define it is dissolving? I think these questions as Paul talks.

“Then, does this mean gay bars are not needed anymore?” I ask. “As opposed to, say, any old bar?”

“Well, we still need them. I mean, Partners? It’s always going to be Partners. Everyone’s going to be coming here,” he says, assuredly. “It’s just now, it’s like a space for almost everybody.”

“So what does Partners mean to you?” I ask.

“A paycheck,” Paul jokes. The two drunk men next to me laugh.

I meet Bernard at Partners, two hours before opening. I have never seen the bar so empty and quiet. The main room is dark except for two spotlights that shine overhead. We sit in adjacent seats by the counter. I begin to fidget. When I look at Bernard’s hands, I notice that he, too, is fidgeting.

Bernard mentions growing up in a conservative family in a small town in Mexico. In 1993, Bernard immigrated to the United States. He was in his twenties and exploring New Haven gay bars. At Partners, he met Dave Klemens. Today, the two are married and run the bar together as co-owners. According to Bernard, not much has changed over the years in how they run their business. They have their cheap drinks, their drag shows, their busy weekends and softer weekends.

“The community has been evolving but we don’t exactly change with them, you know,” he says. “You can do everything on phones. But I mean, person-to-person is better. I don’t know how to explain it.” He pauses. Then—“That was the model the previous owners founded. And Dave kept doing the same thing. If it’s not broken, why fix it?”

Gay bars depend on the “person-to-person” model that Bernard emphasizes in a way that differs from any other bar. Usually, people go to bars to meet other people over a drink, to form a community, to relax and let loose. But the notion of a gay man letting loose is a radical act in this context. It means sexual identities could finally be actualized. It means camaraderie in a society that has condemned

18

Counter Memories

Could this shift change landscapes of queer gathering? What happens to a space when the stigmatization that used to define it is dissolving?

19 March 2023

Counter Memories

The unassuming exterior of Partners and its accompanying mural of Anne Frank.

queer lives. These often anonymous communities were essential to an entire generation of gay men; these bars were one of the few places they could gather. Outside the normative hours, into the nighttime, one could experience their first sexual encounters with other queer people in the liminality of the gay bar. With little barriers to self-expression, the gay bar becomes a place of genesis. Unique queer aesthetics were born: leather and kink sub-cultures, drag personas, cruising codes, creations a heteronormative society might find abnormal. Bernard puts it in a simpler way.

“For me, it was just liberating to come to a gay bar. I knew I was gay, always. But it wasn’t talked about until I came here.” he says. “You see your gay friends. It’s gay community so it’s fun, you know?”

Bernard tells me that Partners was founded in 1974 by Jack Garity and two friends, who ran the bar for fifteen years before handing it off to Dave. Almost fifty years later, the bar is still open. It had survived the peak of the epidemic and the twenty-first century decline of gay bars nationwide. In March 2020, the bar closed due to the coronavirus pandemic. The face-to-face intimacy that the bar provided for the queer community momentarily disappeared. Nevertheless, once Bernard and Dave got state approval, they opened their doors again in May 2021. People flooded the bar and lined up out the door, clamoring to get inside and dance. In a time in which businesses were closing left and right, the community showed out for Partners.

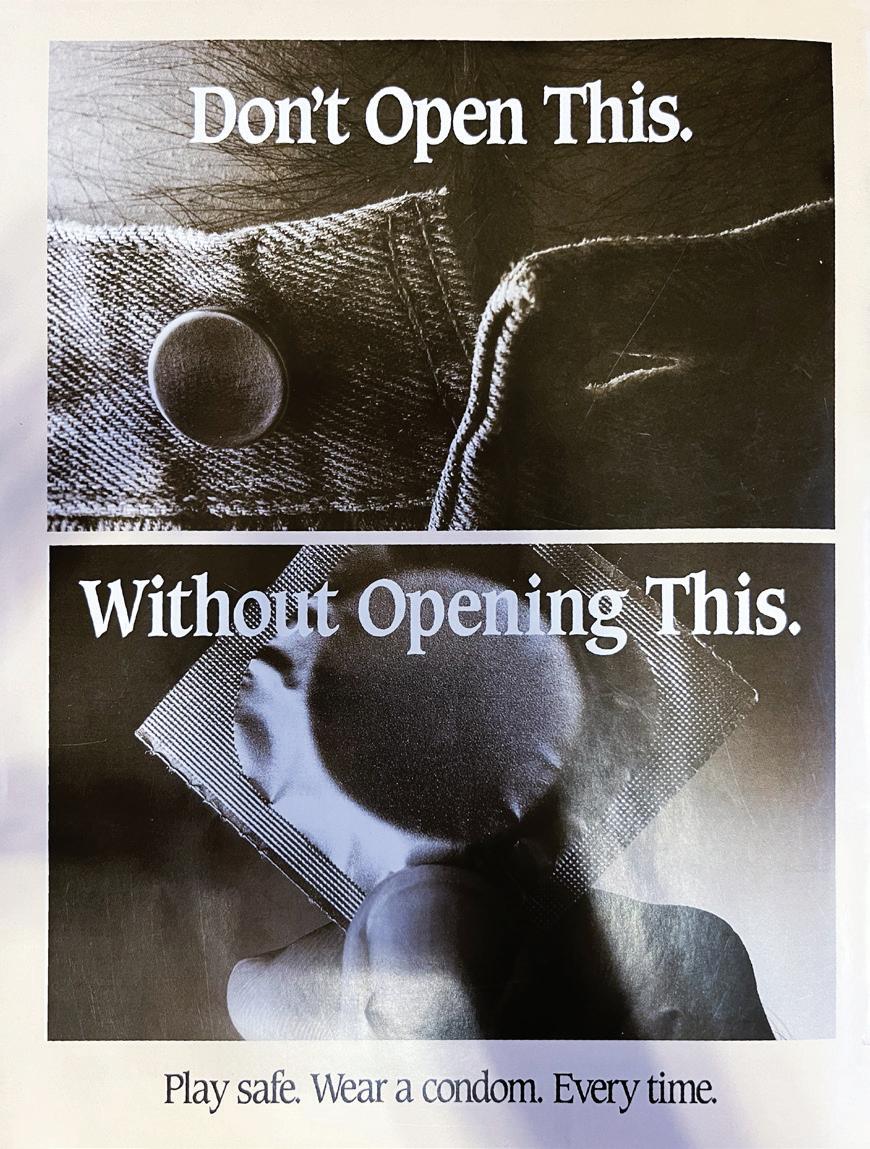

Perhaps Partners is one of the lucky ones. The years between 2007 and 2019 saw a closure of 37 percent of gay bars across the United States and the pandemic ensured the closure of even more. More dire, around 200 lesbian bars have closed since the 1980s, leaving twenty-seven lesbian bars in the nation today according to the Lesbian Bar Project. There have been numerous theories to explain this sudden uptick in closures. Some blame dating apps like Grindr or Scruff that have replaced the gay bar’s person-to-person model. Some blame an exhaustion among gay consumers, resulting from the extensive marketing of spaces and products as “gay” or “queer.” But others seem to hint toward a changing of attitudes within the LGBTQ+ community. Namely, that with a new generation marked by queer acceptance, the need for specific gay spaces as safe spaces is diminishing. In the context of the gay bar, acceptance almost seems like a contradictory phenomenon.

“There will always be the same need for gay people: love and acceptance,” Bernard tells me. “And we’ll provide that here. Because you can make a fool of yourself here. You can go to another place that accepts gay people but you need a safe space. You know that you are different and you always need a place to see your friends.”

He holds his hands up: “This is it.”

In my head, I repeat love and acceptance. I decide to take him for his word.

In between interviews, I stop by the New Haven Pride Center. Inside, I meet Juancarlos Soto, the interim director of the center. When I enter, he has just gotten off the phone. After we talk, we find out both of our fathers are pastors. I laugh at this coincidence. We sit in a room covered with rainbow flags. On the wall beside us, there is a mural of men dancing. Queer history books line the bookshelf next to him. The room is warmly lit by a lamp, illuminating his face. We’re sitting in a chapel of queer paraphernalia.

“I think sometimes we can create harm when we call something a safe space, because the reality is violence still happens, even within our own community. I still interact with queer spaces that don’t feel safe,” Juancarlos says. “Unfortunately, the same things we were fighting fifty years ago are still the same things we’re fighting today. In terms of how anti-trans folks are describing trans individuals and non-binary folks, it’s really the same playbook that we were using in the eighties. It’s just we swapped around terms.”

When Juancarlos describes “safe” queer spaces, such as the Pride Center or New Haven’s gay bars, he likes to call them “brave” spaces. It is an acknowledgement—though aspects of safety have arrived with acceptance, in Juancarlos’ eyes, acceptance has not fully arrived. And if safety cannot truly be guaranteed, why offer a false promise? Any queer space demands the bravery of queer people to exist.

It feels strange to assume acceptance has arrived. Less than halfway through 2023, the United States has seen more anti-LGBTQ bills than the past five years combined. These bills have included a wide range of attacks, from bans on gender-affirming care and drag shows to the discontinuation of LGBTQ education in schools. Last year saw the murders of at least thirty-eight transgender people in the United States according to the Human Rights Campaign. And memories of Colorado Springs, where a 2022 shooting at a gay club left five dead and seventeen wounded, are still fresh on the minds of many gay club-goers. Yet, though queer violence continues to persist, Juancarlos and I both agree that the queer community has changed dramatically.

“The ways the HIV epidemic and guilt have marked older generations compared to how its marked younger generations are very different, right? Because of how much more we know around prevention and how fewer deaths we have now in comparison, when you talk to younger generations, the way you talk about the virus is almost flippant in younger generations compared to older adults,” Juancarlos says. “I think all of those things create differences in their experiences and the issues that they face. But I think if we pause and talk to each other, we may realize that they’re more like the same things that we were fighting.”

He’s right. Scrolling through TikTok, I come across influencers like Zach Willmore, who has been vlogging his life since his positive HIV test results. The videos are mundane. In some, he powders his face with makeup while talking about his medication treatment. In others, he shops for shoes.

20 TheNewJournal Counter Memories

It feels strange to assume acceptance has arrived. Less than halfway through 2023 ,

The end result, even on an interface like TikTok, is revolutionary—HIV is no longer seen as a death sentence. But with this cultural shift, a strange dilemma arises: is normalization synonymous with forgetting? Juancarlos celebrates these generational changes. At the same time, he still seems concerned, unconvinced. We are still fighting the same things.

“The movement sort of went dormant and silent. We were like, ‘Oh, we have gay marriage. We have a president on TV talking about his evolution on same sex marriage. We don’t have to worry about high risk infections of HIV.’ Mind you. Black and brown, specifically, black trans women, were getting murdered at incredible rates,” he says. “Honestly, the LGBTQ community sort of got complacent. It feels like we are going backwards these days.”

Astreet over from Partners, another gay bar called 168 York Street Cafe hides in the basement of a brick townhouse. Its windows are shy, peeking just barely above ground level. From the outside, I don’t notice too much. Maybe the movement of a dim shadow. And a faint Whitney Houston melody. When the night falls, loneliness calls . . .

When I enter, I hear the disco of the seventies, the divas of the eighties—Whitney Houston, Cyndi Lauper, Donna Summer. It’s a far cry from the glitzy dance-pop that had reverberated from Partners’ speakers. Nobody here dances. There is no need to. 168 York is a pub, not a nightclub. Instead of movement, there is the warm clamor of voices. The handful of patrons all seem familiar with one another, sitting on the long counter, talking over each other, laughing. Once in a while, a man walks in and the noise crescendos. People look up, nod, hug, say hello, then goodbye. Amidst the noise, Joey Goodwin, the owner of the bar, sits at the very end of the counter, a seat usually reserved for him. I sit next to him.

“Look at this handsome gentleman interviewing me,” Joey tells a leaving friend. “Oh, who am I kidding. You look old enough to be my grandson.”

I laugh. It’s true. I am the youngest in the room by many years. As I sit next to Joey, I realize I have never in my life been surrounded by older gay men. Age, I realize, is a strange privilege. For an older generation of gay men, lives seemed quickly lived. In a way, escaping youth was an odd accomplishment. Here, all these men sit laughing, in a future they have created for themselves. The wooden walls—a worn brown—testify to the bar’s age. The floor’s faded planks creak at certain steps. Joey used to sand the floors when he needed to deep clean. Now, after so many years, he can’t sand them down anymore without their nails breaking loose. Between the previous owners and Joey, 168 York has existed in some form for about sixty years, making it Partners’ senior. The bar, like Partners, has stood through the heights of the AIDS epidemic and COVID -19, as well as a fire that burned down its old location in 1978.

Joey talks about the levels of caution that used to exist for gay bars. He tells me bar-goers would park

streets away from the bar and wear reflective jackets to obscure their identities as they entered and left. Anonymity was synonymous with nightlife.

“You had nicknames when you were going out, you know. People said ‘Call me Charlie, call me this, call me that,’ So everyone had names until you’re going back to the pub again and all of a sudden Charlie didn’t show up,” he says. “Then you found out that Charlie wasn’t his real name. And then you found out that if you didn’t see him in six months, you were sure he passed away.”

He quickly says goodbye to a departing friend. Turning back, he takes a sip of his drink.

“People who were different came to a gay bar because there was no place else to go. Gay bars were shelters for them,” Joey says. “You wouldn’t see too many straight people in the gay bar back then. They were homophobic. We lived undergroundpurposely.”

Joey sees more straight people entering 168 York now. This isn’t anything that bothers him. In fact, he finds it humorous. He describes how a straight man will walk in, bypass the rainbow flags hanging above the drinks, the trans pride colors on the refrigerator, the drag show advertisements on the walls, and sit down for a drink. As more of the regulars walk in, the man will slowly realize where he is. Joey describes the man’s sudden nervousness when he asks the bartender if 168 York is a gay bar.

“I love it. It just entertains me the most. I’m saying to myself ‘God, I hope so-and-so doesn’t come in. They’re going to give the whole thing away!’” Joey says, laughing.

“Do you think the gay bar should in some way be gate-kept?” I ask. “As in just for gay people?”

Joey shakes his head. “No. I always wanted to be an educator. Being a bar owner, you have a responsibility to say this is unacceptable, this is acceptable.” he says. “I thought the only way that I would ever fulfill that dream was to have people come in here and let them know that we’re not as bad as they think.”

How Joey sees it, gay bars are used as a kind of guided discovery. By having straight people confront queerness in the gay bar, the fear regarding sexuality becomes obscured and ideally, leads to an obvious reckoning—that queer people, at their foundation, are human too. In the gay bar, the straight man becomes othered by his straightness. Sexuality is not defined by its relation to heterosexuality. It is defined, for once, in the context of queerness.

“Are people trying to start new gay bars these days?” I ask.

“I don’t see anyone waiting in line to open up a gay bar, that I can tell you,” he says. “They don’t want any more duplications of a gay bar anymore, because everything’s so diluted now. Most people don’t have to go to a gay bar anymore.”

“Do you think at one point . . .” I start to say.

He interrupts me, already knowing my question. “Your question is, okay. There was a need for a gay bar but because of cultural changes, you’re thinking how long I can stay in the game for.”

I nod. He looks back at me knowingly. In the background, there is an eruption of laughter. Someone,

21 March 2023

Counter Memories

the United States has seen more antiLGBTQ bills than the past five years combined.

22 TheNewJournal Counter Memories

In the gay bar, the straight man becomes othered by his straightness.

Sexuality is not defined by its relation to heterosexuality. It is defined, for once, in the context of queerness.

23 March 2023

Counter Memories

Outside (left) and inside (above) 168 York Street.

another friend of the bar, must have walked in.

“I question myself every day about that,” Joey says. “More and more people keep accepting the fact that there are different people. And because of that, our customer base is dropping. Now people are accepted. They can go anywhere they want right now, and have a really good time.”

As he says this, I look at his face. His voice does not change, nor does he look upset.

“Why do you think the bar has lasted as long as it has?” I ask. “Through so much?”

“We are resilient,” he says. His voice quiets. “But why? That’s the question.”

I pause when he says this. Joey had asked a question that I often think of: Why do we have to be resilient? Put another way, why does it cost so much strength to live?

The next day, 168 York is empty. The noise that filled the bar the night before has slipped out the window. Behind the counter, a bartender shuffles a set of cards, then lines them facedown on the counter. He plays by himself. I do not bother him.

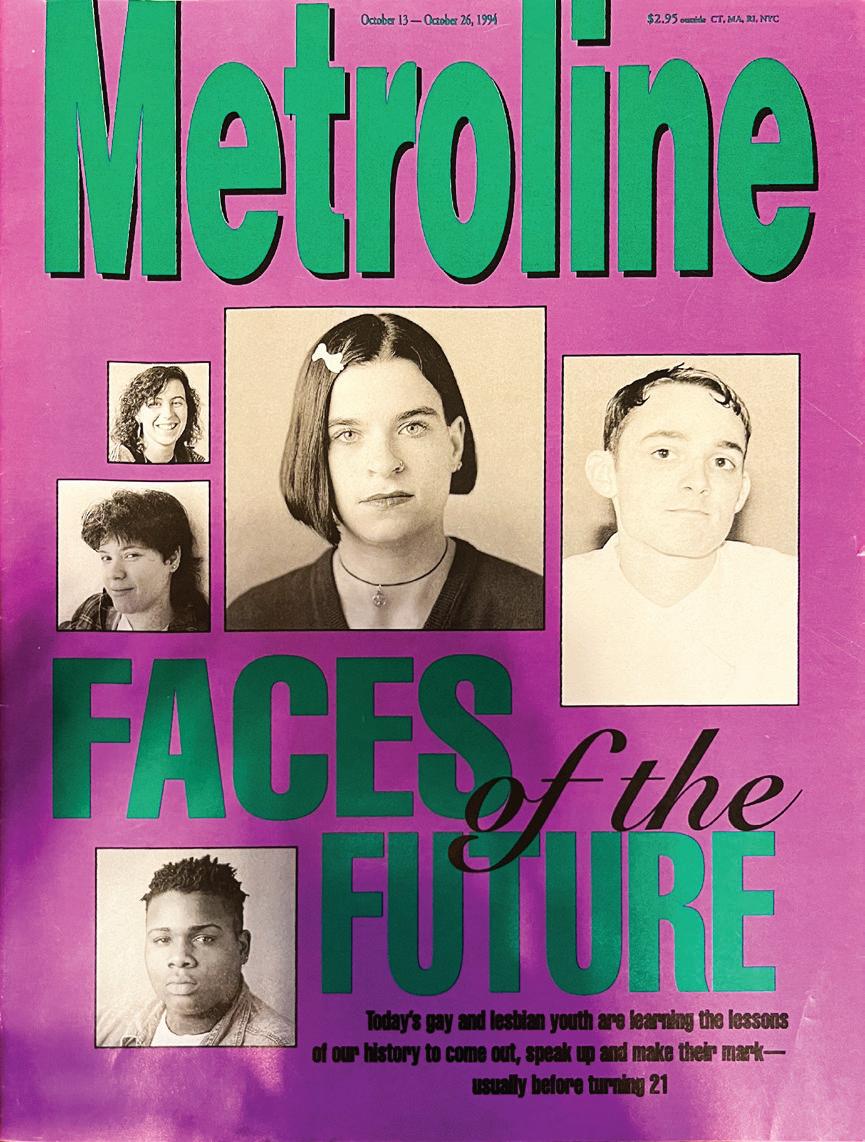

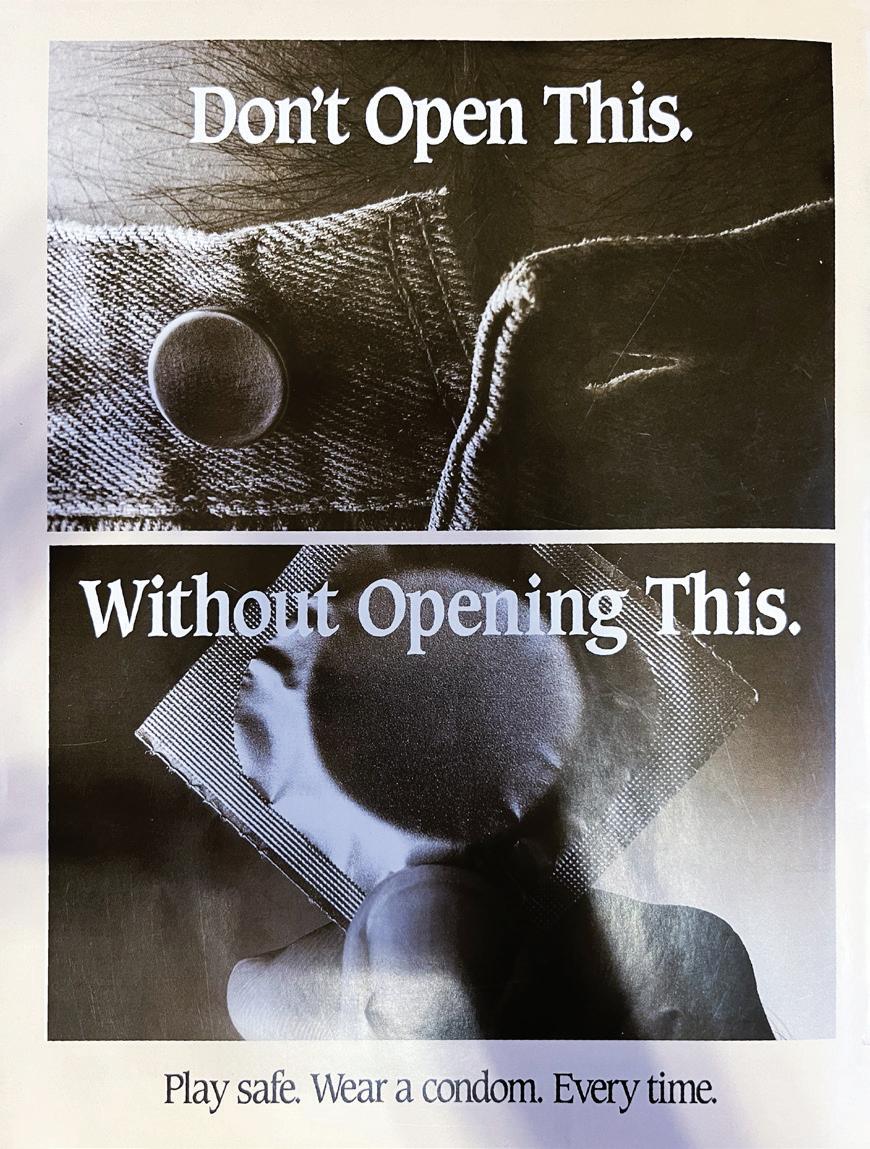

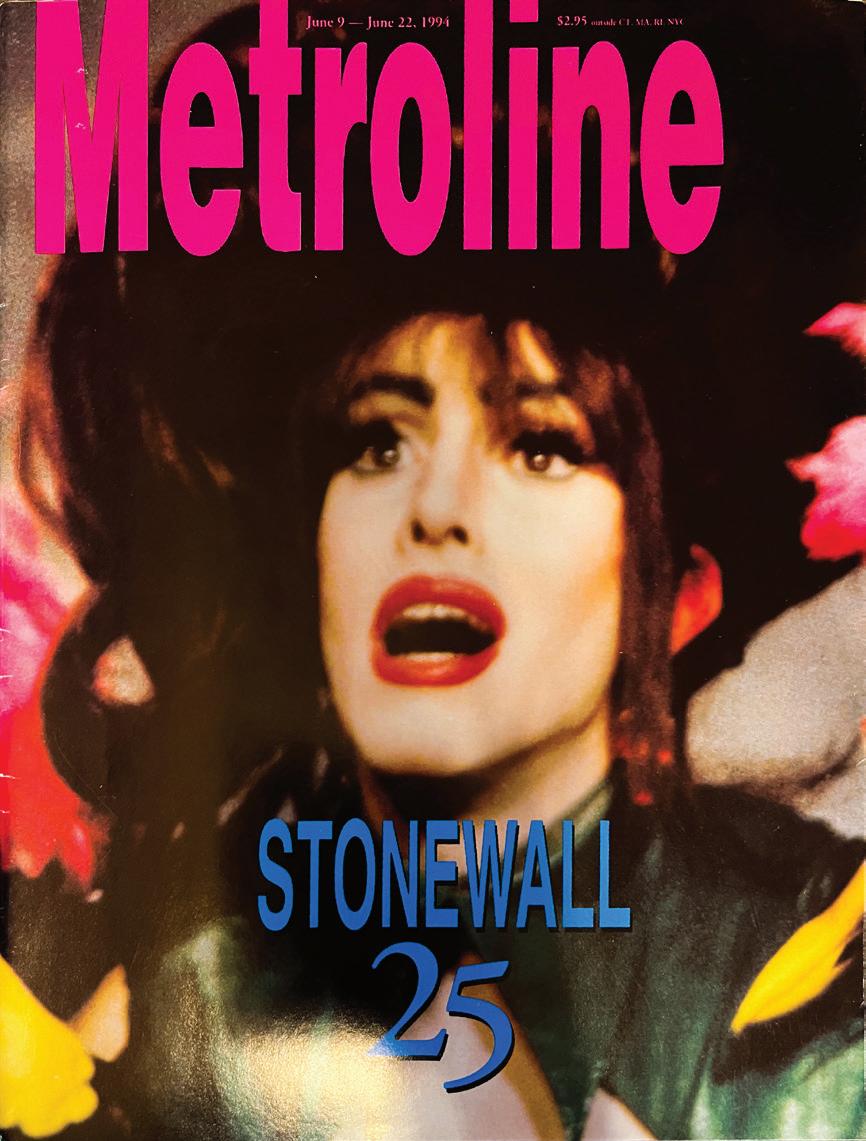

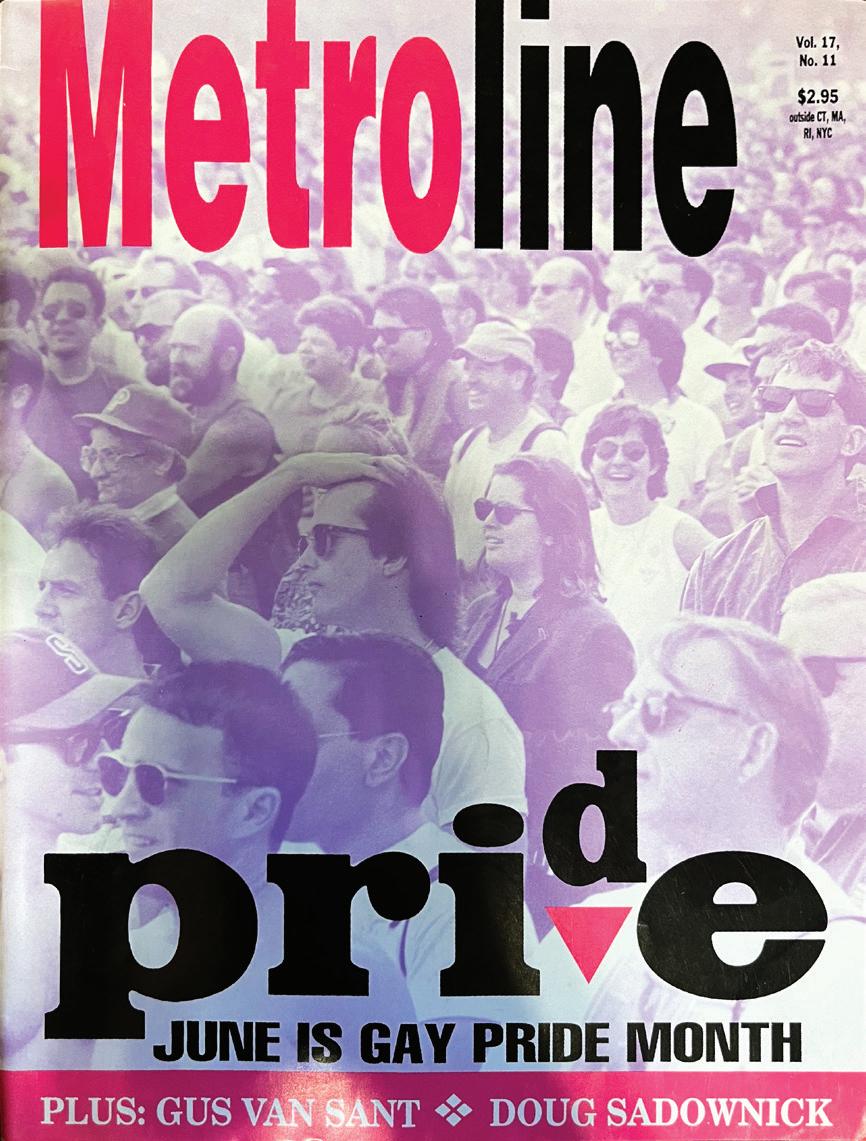

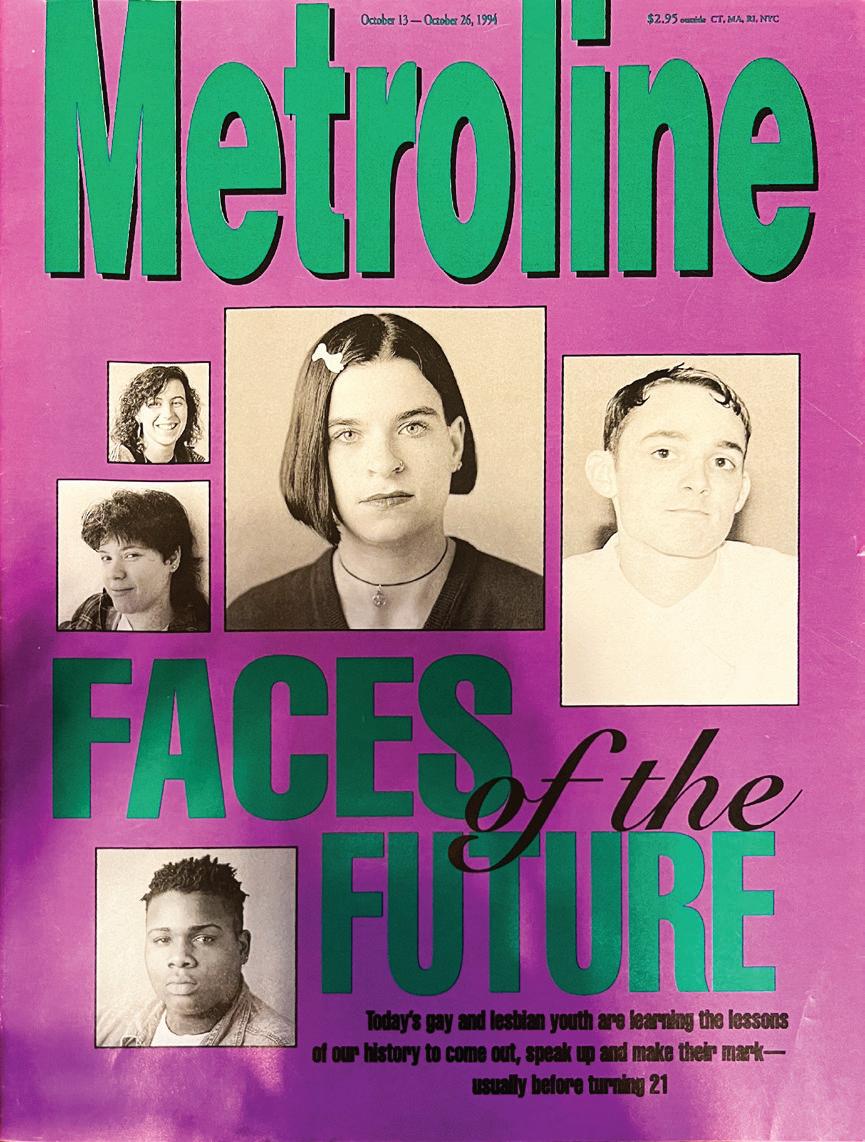

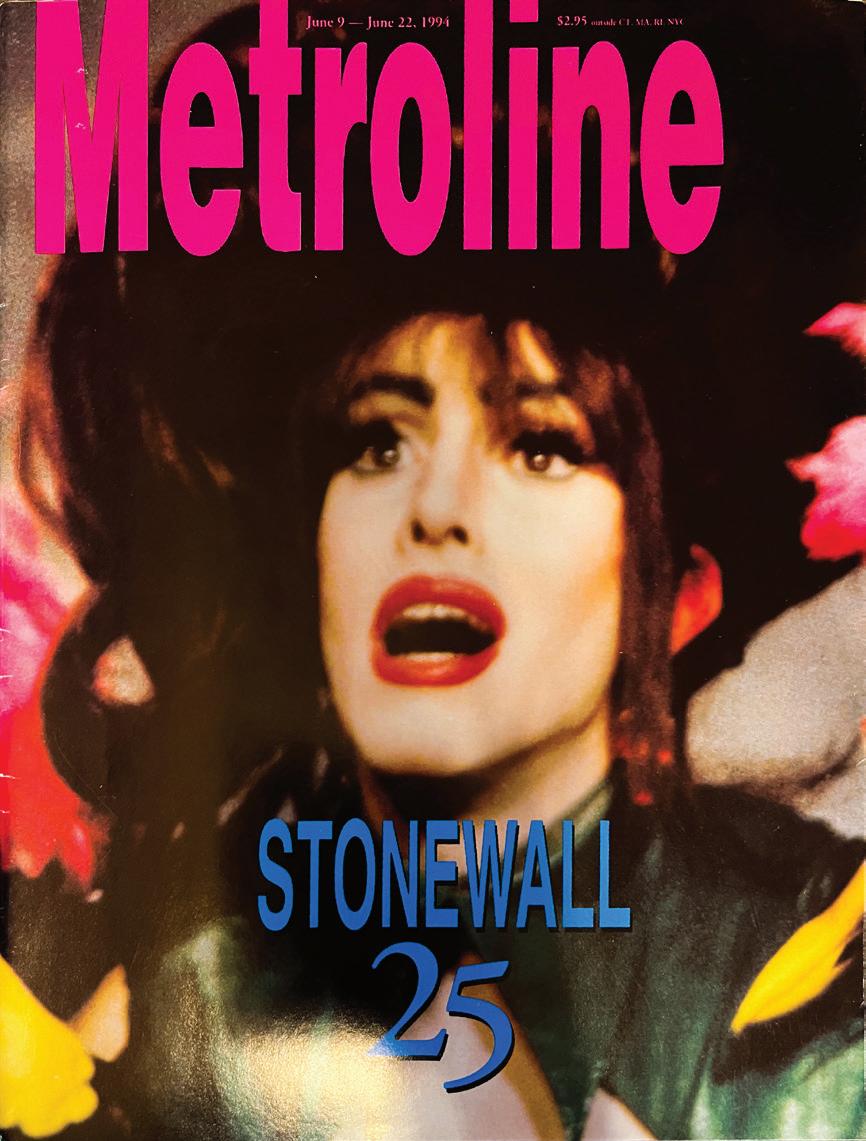

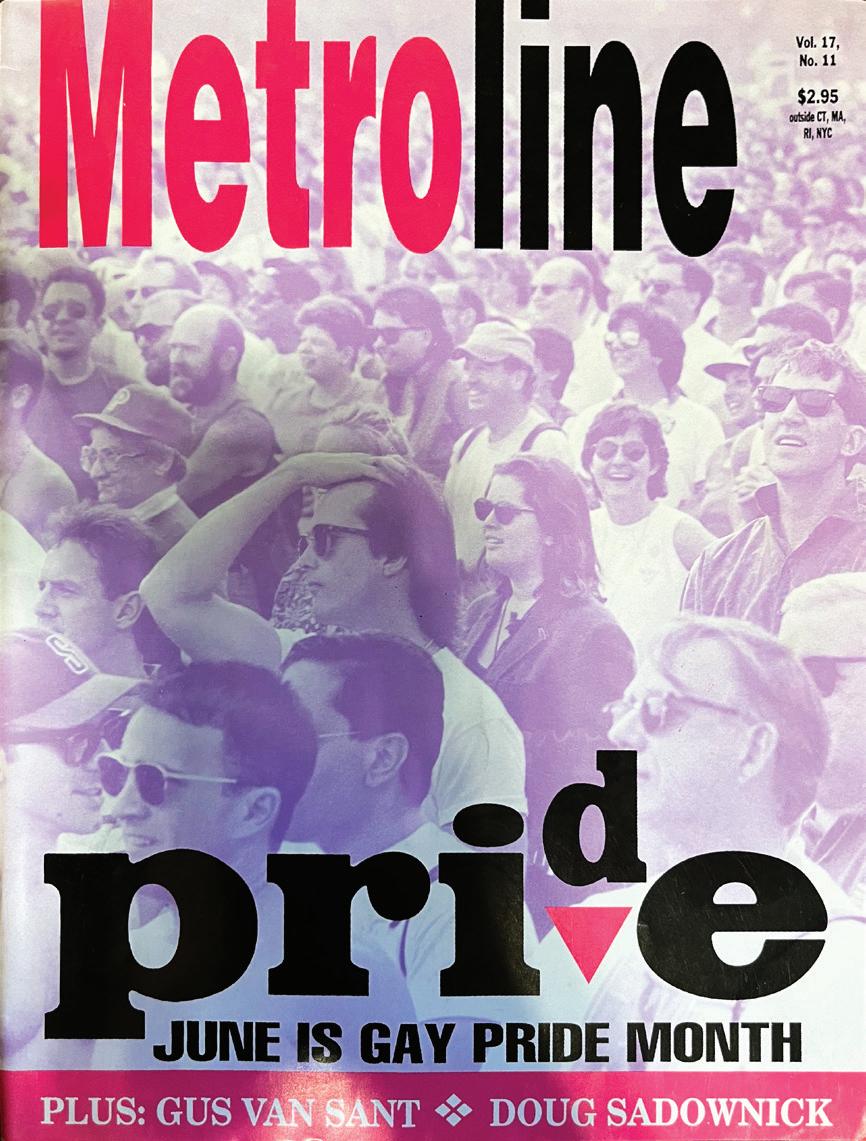

In the next room, I meet Seth Evans. He is just about to have his weekly dinner here at 168 York. He sits under a dim spotlight, sipping on a golden drink. It glows in the light. Seth was the last editorin-chief of a Hartford-based LGBTQ+ publication called Metroline. The magazine intimately captured queer New England life from the AIDS epidemic to just after Connecticut’s legalization of gay marriage in 2008. Between their coverage of the epidemic and interviews with activists, the magazine advertised the Connecticut bar scene. Seth knows many of the bars closely, especially 168 York, where he would write many of his own articles for Metroline at the counter.

“What does the gay bar mean to you?” I ask.

“The bar scene means to me what it means to the first person that walked into the oldest gay bar in Connecticut,” Seth says. “Sanctuary.”

“Sanctuary,” I repeat back to him.

“The normal kid grows up in a home environment where they’re seeing Mom and Dad, and all the normal heterosexual way things are supposed to be. Where does that kid get guidance?” Seth said. “If you don’t come out to the clubs and allow yourself to be yourself, you’ll never know who you are.”

This form of sanctuary is well-encapsulated in the pages of Metroline. Near the beginning of most issues, there are pictures of New Haven gay bars at their prime. A camera’s flash reveals wide smiles, sparkling drinks, bare skin. The dark rooms are filled to the brim with bodies. Queer joy is abundant. Underneath, captions read their locations: Chapel Pub Cafe, Choices, Maxie’s, Saloon —all older New Haven bars. Large bar advertisements adorn almost every other page. The back of each Metroline edition reveals a list of clubs for each Connecticut city, all of which have advertised in the issue numerous times. The sentiment was clear—the clubs were open and alive.

“We started doing the magazine spreads of all the photos,” Seth says. “People would be very, very interested. They would go ‘Oh, I might be in it’ and they all started grabbing the magazine to look at it.”

As the years passed, though, Metroline began to falter. As more advertisers began using online mailing lists and other digital methods, Metroline, alongside other advertisement-reliant publications, took a hit. By the early 2010s, the magazine had become defunct.

“The internet started coming in. And that started killing the magazine,” Seth says. “The bar owners more and more started saying, ‘Why should I pay an ad in your magazine?’ It just became financially not feasible to keep the magazine in print because the bars weren’t paying.”