We look, too, at the in-betweens. The things that make our lives feel especially funny, embarrassing, too-much-too-quick, distinctly ours. Kinnia Cheuk visits a local thrift store, tracing past lives of witchiness and finding new queer magic. Abigail Sylvor Greenberg shares the life of a “Kitty Waxer” and all the ways she makes you feel vibrant and alive. And Arden Yum takes us from Manhattan to Oceanside, following the pace of other lives and finding hers, too.

Thank you to our lifeblood—the writers, editors, designers, website directors, and photographers of our magazine. The New Journal is a labor of love, and we hope to share that with you in these pages. We are grateful for the opportunity to explore these lives with you.

TNJ love, The Managing Board

Editors-in-Chief Jabez Choi

Abbey Kim

Executive Editor Paola Santos

Managing Editor Kylie Volavongsa

Verse Editors

Amal Biskin Cleo Maloney

Senior Editors

Meg Buzbee Jesse Goodman

Nicole Dirks Zachary Groz

Lazo Gitchos Jasmine Wright

Ella Goldblum

Associate Editors

Naina Agarwal-Hardin Chloe Nguyen

Kinnia Cheuk John Nguyen

Viola Clune Ingrid Rodríguez Vila

Grace Ellis Netanel Schwartz

Aanika Eragam Etai Smotrich-Barr

Maggie Grether Anouk Yeh

Samantha Liu

Copy Editors

Yvonne Agyapong Adam Levine

Connor Arakaki Ella Pearlman-Chang

Lilly Chai Victoria Siebor

Mia Cortés Castro Lukas Trelease

Iz Klemmer

Creative Director Chris de Santis

Design Editors Issy Po

Cate Roser

Jessica Sánchez

Photography Kris Aziabor

Nithya Guthikonda

Nour Tantush

Web Design Makda Assefa

Serena Ulammandakh

Members & Directors: Emily Bazelon • Haley Cohen

Gilliland • Peter Cooper • Andy Court • Jonathan Dach • Susan Dominus • Kathrin Lassila • Elizabeth Sledge • Fred Strebeigh • Aliyya Swaby

Advisors: Neela Banerjee • Richard Bradley • Susan Braudy

Neela Banerjee*

Anson M. Beard

James Carney

Andrew Court

Romy Drucker

Jeffrey Foster

David Gerber

David Greenberg *

Matthew Hamel

Makiko Harunari

James Lowe

Chaitanya Mehra

Ben Mueller

Sarah Nutman

Peter Phleger

Jeffrey Pollock

Adriane Quinlan

Elizabeth Sledge

Gabriel Snyder

Fred Strebeigh

Arya Sundaram

Stuart Weinzimer

Steven Weisman

Suzanne Wittebort

• Lincoln Caplan • Jay Carney • Joshua Civin • Richard Conniff • Ruth Conniff • Elisha Cooper • David Greenberg •

Daniel Kurtz-Phelan • Laura Pappano • Jennifer Pitts • Julia Preston • Lauren Rawbin • David Slifka • John Swansburg • Anya Kamenetz • Steven Weisman • Daniel Yergin

Friends: Nicole Allan • Margaret Bauer • Mark Badger and Laura Heymann • Anson M. Beard • Susan Braudy • Julia Calagiovanni • Elisha Cooper • Peter Cooper • Andy Court

• The Elizabethan Club • Leslie Dach • David Freeman and Judith Gingold • Paul Haigney and Tracey Roberts • Bob Lamm • James Liberman • Alka Mansukhani • Benjamin Mueller • Sophia Nguyen • Valerie Nierenberg • Morris

Panner • Jennifer Pitts • R. Anthony Reese • Eric Rutkow

• Lainie Rutkow • Laura Saavedra and David Buckley • Anne-Marie Slaughter • Elizabeth Sledge • Caroline Smith

• Gabriel Snyder • Elizabeth Steig • John Jeremiah Sullivan

• Daphne and David Sydney • Kristian and Margarita

The Witches on Whitney

Kinnia Cheuk explores a local thrift store that brings an inclusive, queer, and modern notion of witchhood to New Haven. profile

The Kitty Waxer and Me

A writer’s conversations with waxer Bianca Cali go more than skin deep.

By Abigail Sylvor Greenbergpersonal essay

Twin Cities

A writer explores life from Manhattan to Oceanside.

By Arden Yumaside

Cake By Isabella PanicoParents and educators alike struggle to navigate New Haven’s patchwork of early childhood care.

By Chloe Nguyen

By Chloe Nguyen

cover story

Connecticut’s commutation policy offers incarcerated individuals a second look and a chance at a shortened sentence. But what does it take to get there?.

By Miranda JeyaretnamAs the dispute over medical aid in dying persists, local advocates voice differing ideas on how to protect those in pain.

By Anouk Yeh

By Anouk Yeh

photo essays

poems

Meditation on Monday Honey

By Isabel Menoncrossword

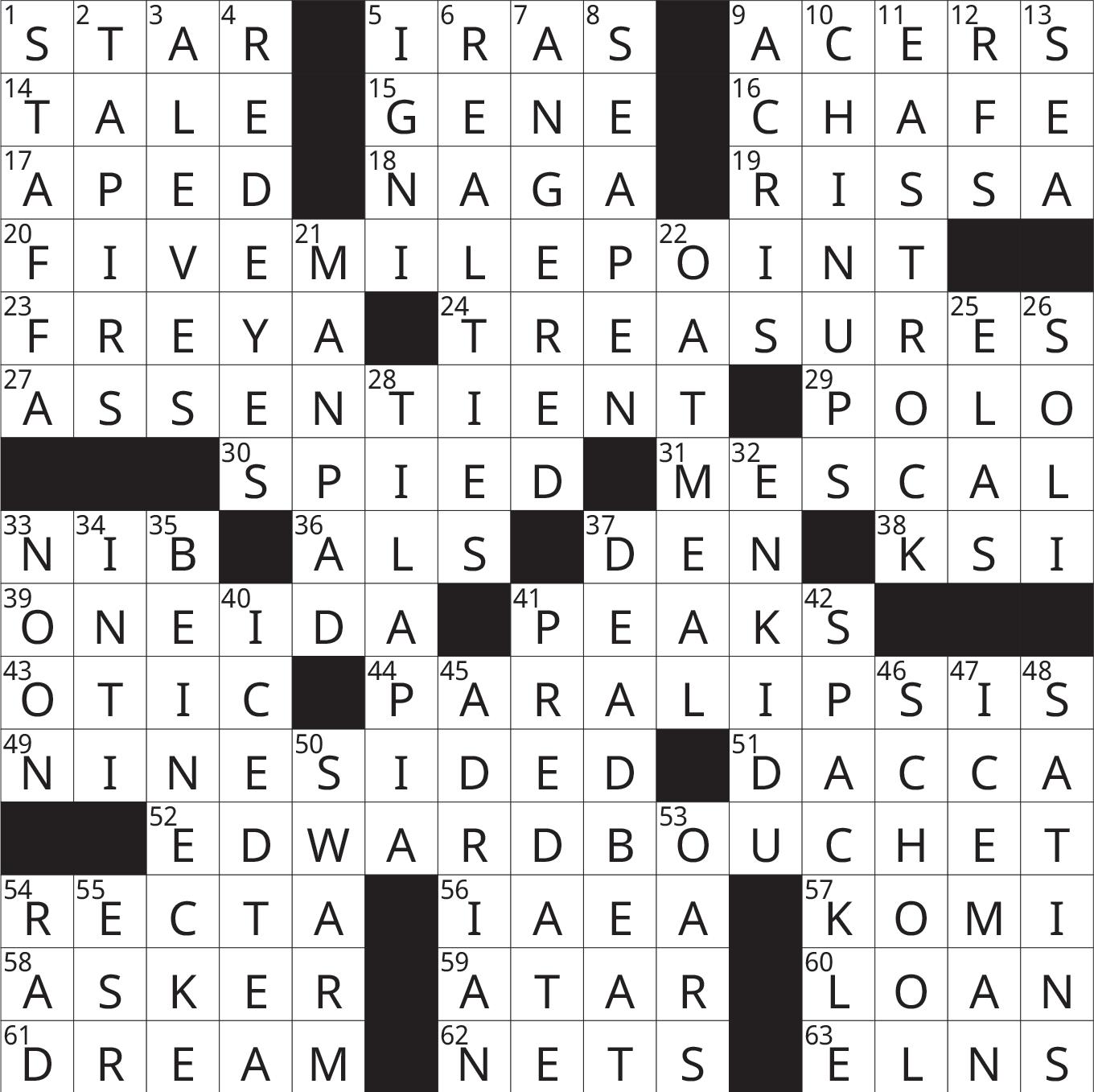

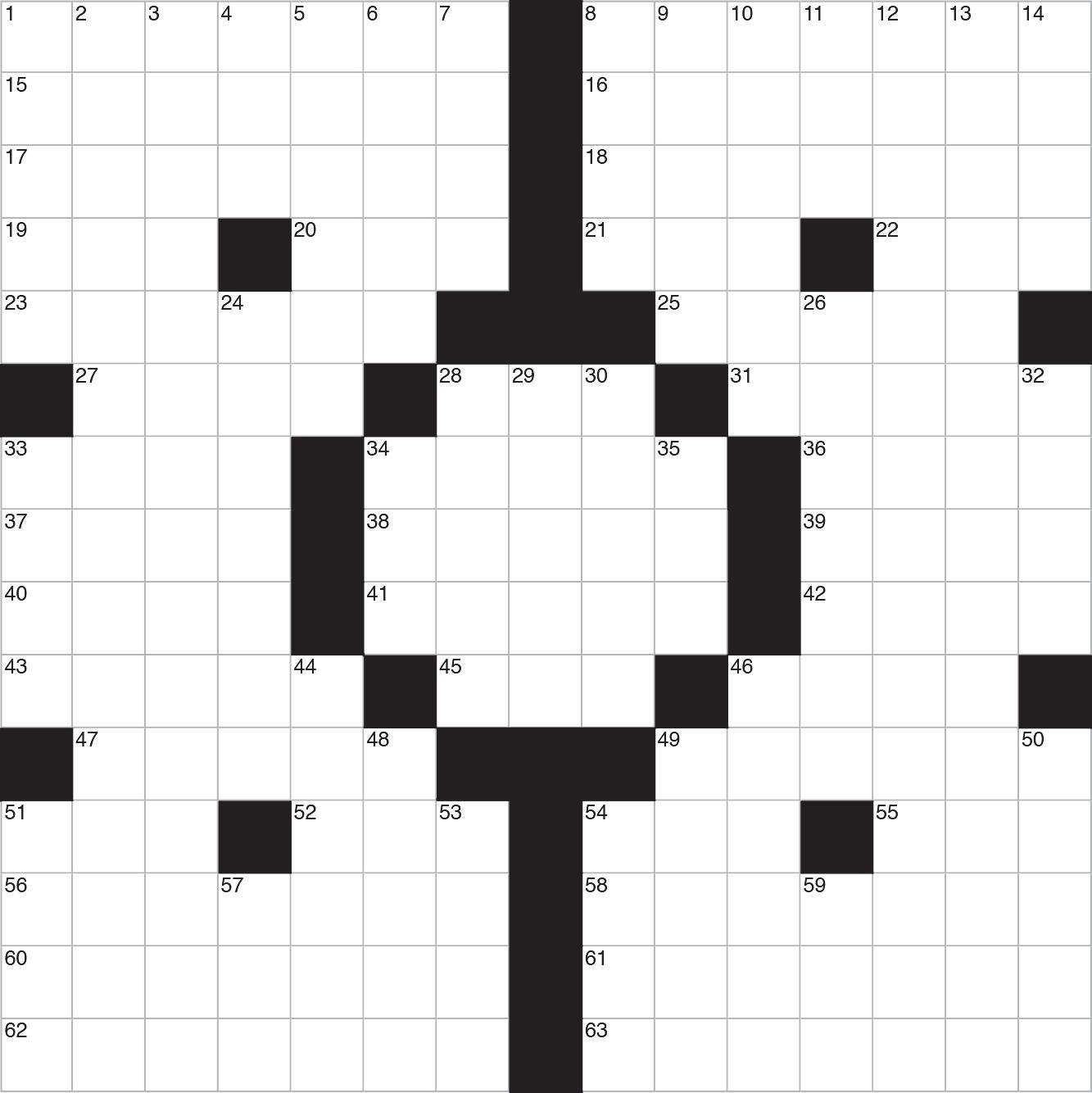

Lost in Elm City, crossword , by Adam Winograd, page 47.

My first time between the clothing racks at Witch Bitch Thrift, I was a stranger at an intimate conference on the workings of witchhood. A stone cat-owl stared at me silently. Galaxy-colored soaps carved to resemble human torsos stood nearby, bound by lengths of black rope in ostensibly kinky ways. I found my reflection in a small object, labeled a “scrying mirror.” The unfamiliar term unnerved me—had I violated some unwritten rule by looking directly at it? I turned to Wikipedia for some relief: “Scrying, also referred to as ‘seeing’ or ‘peeping,’ is a practice rooted in divination and fortune-telling.” I looked up and saw no enlightening vision, but noticed the friendly fine print underneath the label: “Yep, you can take them off the wall to look at them!” I heaved a sigh of relief.

A few days later, I sat and talked with Virginia Semeghini and Eva Ray, who met in music school in Connecticut a few years ago and are now life partners who run Witch Bitch together. Ray was wearing a black t-shirt that said “PLACEBO,” her undercut visible beneath a headband from which felt coconut trees protruded. Semeghini wore a long dark flowy skirt and holographic-framed glasses, sporting winged eyeliner and pointy nails, too. Together, we traced the origin of Witch Bitch Thrift.

One morning in 2020, Semeghini was sipping coffee, pinching herself awake, when she stopped to muse on how she wished an “alternative, cool, kind of witchy, kind of queer” second-hand clothing store existed. “I was just throwing words around my brain, being like witch bitch thrift, witch bitch thrift...? Wait, that sounds really

cool.” Immediately, she signed up for as many social media handles under Witch Bitch Thrift as possible and bought the domain for the website.

In retrospect, Semeghini says that her sense of urgency to create Witch Bitch Thrift stemmed from her desire for both accessibility and aesthetic in thrifting. Semeghini remembers hearing lots of “horror stories” from queer people about walking into the women’s or men’s section in a thrift shop, only for a staff member to direct them the other way. With Ray and Semeghini also struggling to find plus-size clothing in mainstream thrift stores like Goodwill and The Salvation Army, she decided to make Witch Bitch Thrift into a space where clothing of all sizes and a wide range of aesthetics could be found.

Witch Bitch Thrift began by selling clothes online out of Semeghini and Ray’s Bridgeport living room. The business then moved into the Bridgeport Innovation Center, where it was open to the public. After outgrowing the space, Witch Bitch Thrift—along with Ray and Semeghini—officially moved to New Haven in January 2023. Even before the big move, Witch Bitch Thrift had always been inseparable from the city of New Haven. After all, the store’s largest customer base came from New Haven; Ray and Semeghini’s first two dates were in the city; and many of their regular customers, friends, and collaborators lived nearby. Semeghini recalls Ray telling her, “Well, if we want to be a big deal, New Haven’s definitely the best place.”

Centuries before Witch Bitch Thrift played its part in furthering Connecticut’s fascination with all things witchy, witchhood had already captivated the popular imagination. In the seventeenth century, national attention to witchcraft first took form as an ostracization of the other, resulting in the shunning and killing of suspected witches. The mass paranoia surrounding the Salem Witch Trials was just as much about alienating the atypical as it was a fear of witchcraft.

Witch Bitch Thrift sets out to serve the witch and the witchy alike. Witchcraft, broadly encompassing solitary practitioners and followers of religions like Wicca, is part of the larger contemporary pagan movement based on pre-Christian religions and cultures. But beyond spiritual affiliation, there has been a rise of the

witchcore aesthetic online. Witchcore reclaims and embraces traditional witchhood’s unorthodoxy, with feminine-presenting people wearing all black, sporting piercings, and reading tarots and crystal balls, expanding traditional boundaries of femininity and organized religion.

Perhaps the alternative nature of witchiness encourages its associations with queerness. On TikTok, videos under the tag #witchylesbians have accrued more than one hundred fifty-two thousand views. Yet, in the popular imagination, witchiness has remained in that same narrow stereotype of feminine women in black gowns, or as Ray puts it, in the style of “black goth,” “something you can get out of Hot Topic during Halloween,” and “chains, D-rings, studs, heavy makeup.” Though this aesthetic may seem hyper-specific to some, this does not limit Witch Bitch Thrift’s cultivation of an open, queer community space.

When Witch Bitch Thrift first started posting on Instagram, Ray and Semeghini constantly received comments and direct messages from people who thought that their items were “not witchy enough,” because most of Witch Bitch Thrift’s stock strays from all-black clothing. But at Witch Bitch Thrift, being witchy is less about meeting a set of criteria and more about following one’s own intuition and beliefs. To Semeghini, who identifies as a practicing witch, “putting out

your moon water” or “performing your rituals regularly” only matters if your heart’s in it. To Ray, witchiness does not come in any defined form for a non-follower of specific sects of witchcraft. “You can be witchy and dress like anything, it’s about you...There can’t be a box, if you forget there’s four walls there.”

Witch Bitch Thrift is size-inclusive and does not categorize its clothes by gender. All items that go through the shop are hand-measured, then sorted into categories clearly delineated on their universal size chart, such that customers are not confused by the arbitrary sizes that different companies label their clothes. In an Instagram Reel, Semeghini speaks about how, on their online store, there are even armhole or thigh hole measurements for each garment, as well as fabric tags that flag textures like wool and velvet for people with sensory sensitivities. She ends with “What else could we do to make it easier? Let us know!”

And customers let them know: last year, after pushback, the two decided against selling Harry Potter merchandise, considering that J.K. Rowling had recently come under fire for her

transphobic comments on social media. If Hogwarts is a demonstration of false inclusivity, then Witch Bitch Thrift is its antithesis, a place dedicated to being a warm and vibrant haven for everyone who steps into it.

Nicholas Shamp and William Rosedale, regular customers at Witch Bitch Thrift, appreciate that the store fills the niche of an alcohol-free, homey LGBTQ+ friendly space. To them, Witch Bitch Thrift is more than just a thrift shop; it’s family. Shamp handpainted the store mannequins’ nails. He also sewed the curtains for the Witch Bitch Black Box, which is a community space within the store with a mini stage and couches. It’s where Ray and Semeghini organize events like drag king nights, tarot readings, biweekly open mic nights, and a series of concerts by acoustic queer artists (aptly named Acoustiqueer), attracting audiences from New Haven and beyond.

One time at the store, Ray told me that she really liked my sweater. On the way out, I stopped in front of the scrying mirror and saw my reflection. I thought about how my sweater was plain, white, and frankly uninteresting. I looked myself in the eyes—and felt a little bit witchy. ∎

A writer’s conversations with waxer Bianca Cali go more than skin deep.

Bianca Cali has two tips for a better, less painful Brazilian wax.

1. For a wider spread, hang one leg over the side of the waxing table. This makes it easier to access your crevices.

2. When the wax comes off, cough as loudly as you can. This will distract you and force you to exhale.

She shares these tricks with me while my body settles into the waxing table. The butcher paper underneath me crackles. I rest my head on a pink children’s pillow decorated with the felted ears and tail of a piglet.

Bianca produces a bottle of baby powder and shakes a bit onto the relevant area. I’m told this will create a protective layer between the hot wax and the skin so that when the wax is pulled off, it will only bring hair with it, and not stray pieces of epidermis. Between the pig pillow, the baby powder, and my positioning (pantless, belly-up), I can’t help but feel like a giant infant on a changing table.

she dips her wooden stick into the pot, the wax coils in perfect ribbons around the instrument.

A design flaw of the human body is that you can’t really see your own crotch when you’re lying down. But when I can no longer see Bianca’s wand-wielding hand, I start to feel it. Hot. She spreads a layer of wax, stickier and thicker than honey. The viscous glue hardens on my skin, plaster-like.

“We’re gonna apply all the preeeessure. We’re gonna do the bikini line fiiiiirst. We’re gonna create that liiiiip,” Bianca talk-sings, narrating her process. The “liiiiiip” (lip), the raised rim on the border of a strip of hard wax, allows Bianca to grip and tear away the wax when it dries (which takes three minutes, give or take). She flicks the edge of the strip, upturning the lip, and grabs onto it for traction. Then, in one rapid yank, she pulls the wax off, uprooting a garden of tiny hairs. Per Bianca’s guidance, I cough as hard as I can, making a guttural, throat-clearing noise. Bianca peers down at me.

“Not so bad with the cough, right?” she asks.

I blink tears out of my eyes and respond: “Totally!”

to her friends, her friends’ friends, and her friends’ friends’ friends.

She speaks in a high-pitched, syrupy East Coast fry. Her pale, heartshaped face is dominated by big eyes and even bigger glasses that could easily accoutre a “slutty nerd” Halloween costume. She has narrow, groomed eyebrows and dark hair. At 32 years old, she’s not as thin as she used to be. Recently diagnosed with the hormonal disorder polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), she has gained an estimated 30 pounds in the past few years. This, she maintains, has only made her hotter.

When she’s waxing, she wears leggings and tank tops. And at Stella

She’s an indiscriminate hugger, a serial compliment-giver, and a tried and true friend to her friends, her friends’ friends, and her friends’ friends’ friends.

My wax today will be longer and a bit more uncomfortable than it would be for a returning client, she explains. I have arrived with “four phases of hair”—in other words, an unkempt bush. Bianca will need to work slowly, in small sections. She promises that she’ll also give me a break between strips. “They never do that at the wax centers,” she boasts.

Bianca shuffles between the waxing table and a cart to its right where she stores her equipment. She keeps the wax in a metal warmer that plugs into the wall. The wax is a dazzling royal blue that gleams like hard candy. When

Over the course of the next twenty-ish minutes, I undergo this same process maybe eighteen times. Wax is applied. Wax dries. Bianca flicks. I cough. Bianca yanks. We both take a break.

Because this is a Brazilian wax, every hair must go, front and back. She coaches me into different positions. Legs up. Legs down. Open wider. I even lie on my side for a second so she can access a hard-to-reach spot. (This is something, she tells me, she only ever makes Jews and Italians do.)

It’s not my first time getting a Brazilian wax, but it is my first time getting a Brazilian wax from someone I’ve gotten to know, someone who’s told me about her past lovers and her broken washing machine. The strangeness of this dawns on me, opportunely, as Bianca is probing her wooden stick into my butt crack. I almost laugh out loud.

Blues, the jazz club where she sings in a monthly variety show, she sports lace tights, a black A-line mini dress, and a metal headband with cat ears. The ears are a nod to vaginas, so often made to sound feline. On social media she promotes her waxing business under the name “Cali the Kitty Waxer.”

Bianca lives in a second-floor walk-up apartment inside a multi-family home on Winchester Avenue in New Haven, Connecticut. Her apartment doubles as her salon, the workspace cordoned off from the living room by a coral and gray paisley tapestry.

Next to the window is a plastic-wrapped pedicure chair with an empty foot basin. A pop-up spray tan tent leans against the back wall, left fallow while her tanning gun awaits repair.

Bianca is a girl’s girl. She’s apt to start a text with “Hi bubby” or “Hey boo.” She has the mettle to castrate a bull, but she’d never cut a bitch. She’s an indiscriminate hugger, a serial compliment-giver, and a tried and true friend

A poster for Ariana Grande’s 2018 pop album Sweetener hangs on the wall. On the original album cover, Grande’s head is upside down, descending phantom-like from above. But in Bianca’s house, the poster has been rotated. The text is flipped, unreadable, and Grande is right-side-up.

One of Bianca’s friends, a graffiti artist known as La Croix Artistry,

spray-painted a mural on the walls of the stairway; it includes a mélange of geometric abstractions, a cartoonish portrait of Marilyn Monroe, and a particularly yonic crop of pink, petaled flowers.

If there is a precise border between free spirit and hot mess, that’s where Bianca lives. A “third shift gal,” she regularly sleeps till noon, starting her workday as her service-industry clients wake up and her Yale student clients get out of class. She is constantly effusing apologies for petty misdeeds—she’s a few minutes late; she missed your call; there’s clutter in the living room; she just woke up from a nap and forgot to put away her bong.

Most of her clients, I think, like this chaos. I certainly do. When the one-time director of my college comedy group referred me to Bianca, it was with the promise of a rollicking time. A wax and a performance, like dinner and a show.

co-ed counterpart. And even for those who can tolerate mention of female genitalia, pubes are a bridge too far.

But most everyone has them.

Pubic hair has a few basic adaptive purposes, including regulating body temperature, retaining pheromones, and protecting against invisible (but apparently very threatening) dirt and bacteria. It’s not great to get rid of it, but it’s not terrible either.

Even in the days of yore, women groomed their nether parts. Egyptian art showcases women with neat triangles of black hair; the edges are ruler-straight. Greek statues have hairless wedges of crotch between their lush marble thighs. These figures speak of undiscussed self-mutilations—razoring with copper blades, singeing with fire.

proprietary “ingrown hair serum.” The woman at the front desk tried to schedule me for a standing monthly appointment. Balking at this commitment, I didn’t return for years.

Then, at 17, the arrival of my first serious boyfriend brought the topic back to the fore. Thorough research on the now-defunct website Yahoo Answers indicated that all men found women’s pubes disgusting. I discovered that a lot of my friends had gotten laser hair removal, undergoing serial, painful procedures throughout high school to weaken their follicles. It felt like the task of managing my grooming was a test for which I hadn’t studied.

There seems to be an infinity of code words for female pubic hair. Bush. Fuzz. Forest. Muff. Beaver. Landwing strip. Happy trail. Carpet. (Does it match the drapes?) Grass on the field. (Is there any? Play ball!) The language is opaque, positing all kinds of bizarre feminine analogues. Woman as garden. Woman as airport runway. Woman as…baseball diamond?

The earliest intimate waxes in the modern-day U.S. were bikini waxes, which aimed to remove the hairs that poked out the sides of a high-cut swimsuit. This form of waxing emerged in the nineteen-forties as beachwear trends skewed skimpier. Navels were exposed, cleavage popped, but pubes were a different, less negotiable manner of private part. The idea was, and still is, to feign ease—to suggest that there was never any hair down there to begin with.

When Hollywood chooses to show waxing scenes on-screen, it opts for the farcical and slapstick. In an episode of Sex and the City credited with popularizing the Brazilian wax among its viewers, the camera trains its gaze on Carrie Bradshaw’s twisted brow. A miscommunication leads to more hair removal than Bradshaw bargained for, and her mouth puckers into sexy shock as her stiletto-clad leg remains impossibly high in the air. (The double punchline: Bradshaw loves her new hairless snatch and returns for repeat treatments.)

Why do we do it? Because it feels… cleaner? Because it looks…younger? These answers seem inescapably misogynistic and perverse.

I think, optimistically, that the factors driving women to the waxing table are subtler and more varied than mere bikinis and boyfriends—a matted tangle of our wishes for ourselves, our anxieties about how our partners will see us, our impressions of what kind of women we are, some basic sensory preferences. These negotiations are usually private and often subconscious.

Yet, no matter how personal and intimate our waxing practices are, the choice feels inescapably supervised.

After doing her own brows for years, Bianca started waxing other women in 2008, when she enrolled at Central Connecticut State University. Just eyebrows at first. She declined formal pay in favor of free drinks at the school bar. She loved it. If not for her mother’s admonition, Bianca would have simply dropped out and pursued beauty school. Grudgingly, she finished her degree in fine art, then entered esthetics training the same year. This was where her waxing repertoire grew to include bikini waxes and Brazilians.

It’s no surprise. Even in a post-pussy hat world, people still hate vaginas—the word “vagina,” images of vaginas. The schoolyard game in which children compete to say “penis” the loudest has no

I’m not sure why I got my first intimate wax. I was in eighth grade, and I was mystified by my own body, always searching desperately for cues from friends and older women to know what was expected. I ambled into my local branch of the popular waxing chain European Wax Center and asked for a clean-up job ahead of a family vacation. It was terribly painful and not very thorough. On my middle school allowance, I couldn’t afford the salon’s

The first few professional waxing jobs brought frustration. At a men’s barber shop, she was stuck in a back room and gossiped-about in “really dialect Italian” by the otherwise male staff. She eventually realized she was working for a mafia front, and quit.

Even worse than working for the mob was her job at the European Wax Center branch in Greenwich, Connecticut. There, she waxed rich soccer moms for poor pay. “You’d have to wax six vaginas an hour to make more than $15,” she estimates.

When she tells me that she supplemented this meager income by working

The idea was, and still is, to feign ease—to suggest that there was never any hair down there to begin with.

at a go-go bar in Yonkers, New York, I note that this sounds retro and not like something they have in Yonkers. Quickly, she corrects herself. “It was a topless strip club,” she admits.

being a stripper made her a better waxer, someone impervious to the garishness of naked bodies. She grew comfortable enough in her own skin to set others at ease in theirs.

Bianca returned to the comparatively dull world of Connecticut salons emboldened by the enterprising spirit of her stripper days. She started a new racket. She took jobs at established chains, among them Tommy’s Salon and Bluemercury, then poached clients and began to build her home salon between gigs.

all together.” It was just the two of us in the room, and I was confused by the plurality, girls, and I didn’t know where we were back from. Still, I liked the ring of it:

The girls are back. We’re all together.

Bianca gives the best wax I’ve ever had. She’s the fastest and the thorough-est, and the most adept at loosening the grip of my self-consciousness. “Naked is naked,” she says of the presumed awkwardness of her job. “Fluid is fluid.” She’s seen it all, and it’s all more alike than different.

The managers of City Lights Strip Club originally gave Bianca a position as a shot girl—defined on Urban Dictionary as a “beautiful woman at the club that is too hot to strip, too stupid to bartend.” Bianca made good tips but feared she was a thorn in the side of the harder-working strippers. To really earn her keep, she needed to become a dancer herself.

The more experienced strippers at the club taught her how to twerk, took her to the Bronx to buy her first pair of Pleasers (a type of stripper heel favored for its grip), and introduced her to a woman named Miss Jamaica who sewed luxury brand logos onto wholesale leotards. This delighted Bianca, who aspired in her youth to be a burlesque dancer, and in her even earlier youth to be Liza Minelli.

As a stripper, she learned to grift like never before, traversing the club circuit with a dancer from Russia who posed as her twin sister: Lana and Natasha, they called themselves. “She taught me,” says Bianca, “that there is always a way to make money.”

Bianca also quickly realized that nobody needed consistent hair removal more than strippers. She carved out a niche for herself, waxing the dancers at her own club and the surrounding ones. By the summer of 2015, Bianca had something of a monopoly on East Coast stripper pubes. Her domain stretched from New York to Rhode Island. She drove to different cities, rented hotel rooms, and waxed the dancers en masse.

To this day, Bianca maintains that strippers are the best clients. They’re friendly and appreciative. They tip well. They get it. She also believes that

Other than one occasion when she was giving a “Manzillian” and accidentally tore off a piece of a client’s testicle, Bianca has had remarkably few waxing disasters. This is because she is a very good waxer. Good enough that she could do it in her sleep, she tells me. Good enough that she’s done it while drunk, she also tells me.

At 21 years old, I’ve now had more Brazilian waxes than I can count. But I still feel a childlike ineptitude every time I get waxed. My hastily-folded underwear, dropped on some chair beside the waxing table, looks incongruous, ratty, juvenile. My legs are hideous on the table—wide and veiny and gray, with their own crop of suddenly-obvious stubble. I wonder: Is my body the worst, weirdest body that this waxer has ever seen?

I know that forking over $80 to get all my pubic hair painfully pulled off is a transaction in a rigged economy whose two currencies are money and hotness.

The best evidence of how good she is, however, is that she’s earned the right to have fun while she works. She sings, and gabs, and monologues, bitching about the ex-boyfriend she keeps sleeping with. She’s found that being in an exclusive relationship with him makes him “protective, and, like, annoying.” She still walks his dog.

A man, to Bianca, is a lot like a dog that needs to be walked, or at best, a big tipper at the strip club. Her focus is on women. She has seen the vaginas of moms and mommies, strippers and shot girls and sorority sisters. She calls everyone a “girl,” to their faces and behind their backs, whether they are 18 or 80 , old friends or new acquaintances.

Once, as I lay on the waxing table, she incanted: “The girls are back. We’re

But still, I am fearful from the first strip to the last, not because I’m scared it will hurt—hell, I know it will hurt—but because, even though all I have to do is lie there, I feel like I’m doing it wrong.

On a few occasions, I try to bait Bianca into confessing that she sees what’s problematic in the whole ordeal. I expect she might say that she knows waxing is a patriarchal con, but she’s learned to profit from it like a sleazy girlboss.

I say, “I wish they’d invent an easier way of doing this.”

She says, “This is pretty easy.”

I tell her that some of my friends from college are “rockin’ full bush.”

“We gotta tell them,” she says, as she begins to scheme for a punch-card system.

I ask her why she thinks people get waxed.

“I feel like it takes half your life to shave your body.”

Eventually, I stop trying to force this concession. I know that forking over $80 to get all my pubic hair painfully pulled off is a transaction in a rigged economy whose two currencies are money and hotness. I know it’s something men don’t have to do, something I shouldn’t—and really don’t—have to do.

But the body is wracked with problems, and there is a comfort in Bianca’s determination that at least some of those problems can be solved.

an animation she sets up for ambiance: a table, set al-fresco with coffee mugs, doodled lines of steam trailing upward. In the corner, a black sandwich board bears the inscription “CAFE VIBES.”

When I get on the table, Bianca tries, as always, to give me a good wax, quick and painless. She complains about the same dude as always, who borrowed her car and ran the gas down to zero and didn’t refill it.

When she’s finished, she goes back in with tweezers for any rogue hairs she’s missed. It’s a series of rapid pricks, and each one hurts a different way, a different amount. The surprise is the worst part.

In a few weeks, each hair will return, poking to the surface as if to say: think again, bitch.

own hip bones rising, my muscles seizing. My body never gets used to the shock of the heat, the fury of the pull. She rips it off with abandon.

“That last one,” she says, “is because I love you.”

PCOS, the hormonal condition from which Bianca suffers, brings a host of frustrating and intractable metabolic and fertility problems. But its telltale symptom is the growth of an above-average amount of face and body hair. Because of this, Bianca’s own grooming routine includes not only frequent self-waxing, but also perpetual plucking and even facial lasering—a multi-front effort to keep her body hair at bay.

Knowing how PCOS works, I can understand why Bianca might feel that hair is a manifest badness to be excised. A thick strand protruding from the skin is a weed in a garden—pesky, unwanted, and always growing back. This is a feeling I can relate to. Hand me a pair of tweezers and I will wage war on a lone chin hair. It can feel heroic to purge oneself of the brittle, wiry enemy.

Yes, hair is “natural,” but if you think every natural bodily function is perfect and good, you probably don’t have a period, or thighs that touch. Some parts of the female body are bad, not because the patriarchy said so, but because they hurt, or itch, or feel weird.

Waxing might be a trap, but so is the body. So what if I want to be smooth as a seal?

She smears a last blue strip on my lower abdomen. This part I can see—my

On one rainy day, when it is already dark outside, I step into Bianca’s apartment, and she greets me with a hug.

The air is musty with stale weed and incense. The bottom hems of my pants are wet. Bianca’s cat, Boxer, sleeps with heaving breath. On the TV, there is

When I get my haircut I like to imagine The barber is you.

I don’t notice the Eminem playing or the feline purr of the clippers or the whir of electricity from the shop’s neon Suavecito sign.

I think about his big and soft hands that press my ear to my cheek and crane my neck back showing me that I’m handsome.

Me looking into the mirror You looking at me and finally asking

How was your day? Got plans this weekend?

and you are beside me grazing my temples measuring and sectioning out strands of me, carefully untangling each one

while I gaze, dimly thinking about those fake silver rings that leave turquoise specters around your giant fingers that once petted my stubble like a stray cat.

So when I see my haircut is uneven and I know it’ll have to grow it out again I still tell him

It’s just what I asked for! I’ll see you again! That way I leave without losing more than that to an EyeVac.

—Dean Farella By Chloe Nguyen

By Chloe Nguyen

Throughout her decades-long career , Georgia Goldburn vowed never to close the doors of her childhood development center. Goldburn, Executive Director of Hope for New Haven and a child care industry veteran, was determined to run her programming— despite tens of thousands of dollars worth of debt, high staff turnover, and overall financial instability. After navigating the risks of operating through COVID-19, Goldburn reviewed her business’s 2022 finances. She realized the sum she could afford to pay her teachers was less than the amount they would receive from unemployment benefits.

Goldburn’s motivations to operate exceed a financial bottom line. They have to. Goldburn has committed herself to providing early childhood education to Black and brown communities. She has observed firsthand how a lack of targeted childhood support services, insufficient teacher compensation, and inaccessibility of high-quality educational programs influences outcomes in the community she calls home.

Goldburn’s program Hope for New Haven centers under-resourced communities of color. Her mission is to consolidate educational resources for minority groups emerging from her community.

“What we want is for people of color to still have those connections without having to leave a community to achieve economic success,” Goldburn told me. She emphasized that it is not enough to haplessly invest money into underserved populations without being conscious about keeping those groups connected.

“You have to be intentional in how you bring money into child care,” she said.

The system of reallocation is not always an equitable one. According to Eva Bermúdez Zimmerman, Coalition Director of Child Care for Connecticut’s Future, the state’s solution for early education is a general stabilization fund for licensed child care programs, leaving everyone haggling. Subsequently, the investment can bypass communities most in need and manifest in short-sighted solutions, such as inserting children into affluent neighborhoods rather than fortifying their local resources.

Before 2021, universal early child care in Connecticut was unheard of until the formation of Child Care for Connecticut’s Future, a coalition with campaign goals of securing fair compensation for educators and more affordable child care for all.

Providers, who range from close relatives taking care of children to those working at childcare centers like Goldburn, understand that when they show up to their jobs, parents can show up for theirs. The effect bolsters the economy and the broader state community. As Executive Director of the Buffett Early Childhood Institute, Dr. Walter Gilliam quips: “Child care is like the road…if it doesn’t work, you can’t get to work.”

But nationwide, legislators and policymakers do not treat early childhood care as a fully subsidized public good. Unlike kindergarten through high school, early childhood education does not fall under the funding and discretion of a standardized public school system. The closest thing Connecticut has to a universal early child care system is its twenty-two Head Start programs, state-subsidized school readiness preschool programs that serve more than 5,539 children and families. But these programs often contain waitlists of over a hundred families and struggle to employ qualified teachers. The local government’s other stopgap—a program called “Care 4 Kids” that subsidizes the cost of child care from a wide range of providers—can prove inadequate or simply too obscure. Parents and educators alike are thus primarily left to navigate a complicated patchwork of funding, care options, and availability alone—with plenty of barriers to access.

Every dollar spent on child care, Gilliam noted, yields $7.30 in “society savings.” These savings represent the money gained back when a child has a safe educational environment, the chance to secure their degree and employment, and ultimately the tools to become a productive citizen. According to the Early Childhood Alliance, the first one thousand days of life is the most significant time for secure attachment and brain development. Goldburn noted that 80 to 90 percent of a child’s brain has already developed by the time they are 4 and 5 years old. For this reason, early childhood educators are pivotal in nurturing those basic, life-altering skills that are underestimated yet critical.

Despite the need for these crucial skills, policymakers and lobbyists alike often neglect to fund early childhood education. This is perplexing because, as Gilliam notes: “Anytime something is considered an infrastructure and essential to life and the general public can’t afford it, the government subsidizes it.” If that were the case, early childhood education should have been queued years ago.

“If someone isn’t gonna get rich off of it, [a bill] might not pass,” Gilliam told me. He noted that to pass a policy funding early child care, the proposal must characterize the care as necessary to other things constituents care about, namely their own assets. While child care buttresses familial life, business often takes precedence.

Early childhood education, then, presents a difficult business model. Many childcare centers struggle to generate revenue and fairly compensate staff, incentivizing fewer people to join the field. A third of programs operate in debt, and 71.8 percent are short-staffed. Providers and parents

across Connecticut, particularly those who belong to and serve marginalized populations, are often forced to make decisions in a broken, contradictory market.

In the spring of 2022, the median wage of a childcare professional was $14.97 per hour, hardly exceeding the state minimum wage of $14 at the time. Many of these professionals have earned their associate’s and bachelor’s degrees, and yet they are compensated like entry-level workers. Bermúdez Zimmerman told me that both locally and nationally, solutions for recovering the funding deficit are still in the early stages. While there are state-subsidized readiness programs, they struggle to employ and retain qualified staff members.

“It’s a rotating door, it’s not sustainable,” Bermúdez Zimmerman said. Educators seek security amidst a shortage of qualified staff, the backbone but most challenging aspect of the industry.

competitive landscape with three thousand, eight hundred staff vacancies and an essential service barely treading water. The money parents pay is not streaming into teachers’ pockets; rather, it is financing overhead costs.

Lottie Brown, another New Haven-based childcare provider, runs her decade-old business out of her home, a completely baby-proofed facility with a colorful array of puzzles, art supplies, and occupied gardening trays. In Brown’s experience working in her own business and the New Haven public school system, classrooms serve as safe havens for young children. According to Brown, some of these children were born surrounded by drug usage—3year-olds have come into Brown’s care cursing and sporting “drug paraphernalia.” “What happens to that child who found her mother unresponsive?” Brown asked. Her experience with children who have been brought up in unsafe circumstances propelled her to step in as a childcare professional.

Developing and operating an early childcare program requires a level of attention and care that far transcends the glorified babysitter stigma—that the extent of the job is merely monitoring children.

Devonna Lewis, who currently teaches at a New Haven public school pre-kindergarten program, experienced the impact of this pay firsthand. Lewis began her career in early education at a private center. At the time, she was a 24-year-old single mother seeking child care for her daughter. Now, decades later, even after receiving her associate’s degree, little has changed as far as financial insecurity in the industry. Lewis told me that there is no way to win—either hardly subsist on minimum wage or make $10 beyond the threshold and lose out on food stamps, healthcare, and other government assistance covered under state general financial assistance programs.

Yet while childcare professionals struggle to make ends meet, infant care in Connecticut is still prohibitively expensive—25.5 percent more per year than in-state tuition for a four-year public college. According to Goldburn, educators mostly use revenue for technical maintenance like fixing licensing issues, facility repairs, and citations. Despite the need for these programs, many childhood educators are struggling to swim in a market of contradictions—a highly

Developing and operating an early childcare program requires a level of attention and care that far transcends the glorified babysitter stigma—that the extent of the job is merely monitoring children. Early childhood educators find themselves preparing both academic and emotional toolkits. To help build their confidence and self-esteem, Brown encourages her students to engage with one another and their surroundings.

“Children need structure, but they also need opportunities to learn without teacher-directed things,” Brown told me. Purging her program of digital devices, teaching her students how to garden, and helping them pick up a paintbrush all allow the children under Brown’s care to advance lifelong skills.

But a solid curriculum is not enough for a program to thrive, according to Goldburn. The program has to be marketable. Improving retention rates and appealing to wealthy patrons means that her program and many others must spend their income to comply with industry standards and bring in quality resources. When facilities are struggling to meet those expectations, Brown reflects, licensing divisions and families alike may perceive the program to be lower in quality. Yet centers can only work within their means. Less than a third of childcare centers in Connecticut report a positive cash flow.

Without the money to afford expensive facilities and equipment, childcare programs must try to circumvent whatever judgment that might be

easy for onlookers to pass. “All people are left with is what they see,” Goldburn said. And what many see are centers that are providing high-quality care without high-quality resources. Achieving such standards has a price tag, namely, the enormous wage penalty paid by early childhood educators. It is a financial burden taken on primarily by women of color—whose labor is underpaid and undervalued.

“Had it been a male-dominated industry, would we be facing the same challenges?” Anna Witkowski, Chief Education Officer for the Children’s Learning Centers of Fairfield County, asked me pointedly. Out of her one hundred forty employees, two are men. A previous male employee left to work at a Target, which paid $27 an hour compared to the $17.50 he made hourly as an early childhood educator.

In an industry sustained by women—who comprise about 94 percent of childcare workers—these professionals struggle to disband the notions of glorified babysitting and passivity often associated with their jobs.

Friends Center for Children

Executive Director Allyx Schiavone explained that the societal denigration of contemporary early childhood educators exists within a history of exploitation. She urges us to confront a parallel reality: “The childcare system was born out of slavery.” Throughout antebellum America, Black enslaved women cared for the children of white slave owners. Modern disparities in education staffing and access embody the legacy of centuries worth of subjugation.

“When we become so habituated to neglecting and exploiting a group,” Gilliam explained, “it becomes easier to not think about them at all.”

Disregarding the experiences and histories of women of color perpetuates a childcare system that exploits their labor. Goldburn confirmed that the financial struggles experienced by childcare industry professionals are most acute in marginalized communities. Black early educators are paid on average $0.78 less per hour than their white peers, which adds up to more than one thousand dollars lost annually.

Connecticut provides a state-subsidized childcare program—Care 4 Kids—to families with an income of less than 60 percent of the state median income. It is the only subsidy-based

childcare program in the state of its kind in that it supports independent providers. And while many families benefit greatly from the financial assistance, most still have to make partial payments, upwards of 30 percent of their income, to keep their children enrolled in child care.

According to the state’s plan for the federal Child Care and Development Fund, Care 4 Kids reimbursed 52 percent of the market rate for infant and toddler care and 30 percent of that for preschoolers. A discrepancy between the true cost of child care and what providers receive leaves parents struggling to pay the difference on their own. This divide—coupled with slow processing time and a lack of easily available knowledge—limits Care 4 Kids’ ability to fully aid Connecticut parents.

The Care 4 Kids website defines childcare providers as early childhood centers licensed by the Connecticut Office of Early Childhood or a close relative designated to watch over a child. Care 4 Kids sends a Child Care Certificate to admitted applicants, which authorizes payment for services for up to a year. Families must undergo an annual redetermination process to reaffirm their eligibility for the program.

Throughout the final months of 2022, Care 4 Kids covered a considerable portion of New Haven mom Christina Moore’s childcare fees. Like the families of more than twenty-five thousand other children enrolled in Care 4 Kids, Moore met an income limit of less than 60 percent of the State Median Income. She needed a daycare to supplement her efforts to support her son’s learning while she worked full-time. With the promise of these subsidies, Moore enrolled her 2-year-old son in daycare.

But even with the state aid, her son’s child care placed an increasingly heavy financial burden on her family. Due to a marginal increase in her income, Moore had to pay a “family fee”—an outof-pocket cost based on her gross income—to keep her son enrolled in daycare when he turned 3. As Care 4 Kids withdrew part of their financial assistance, Moore started sending her son to daycare two days a week instead of five. She had to adjust her work schedule to accommodate her son being home.

Moore moved her son into another pre-kindergarten readiness program this past year. But the new center had not been inspected. Childcare centers in Connecticut are expected to undergo state-mandated health and safety inspections, including training requirements in CPR, medication administration, and other forms of emergency preparedness. But centers are expected to front the cost of inspection—a cost that some cannot afford.

If Moore had been forced to foot the bill while seeking Care 4 Kids coverage, she would have had to sacrifice a third of her mortgage in the name of keeping her son enrolled in daycare. Luckily, the

education center held off on charging her from February through June while Care 4 Kids evaluated its case. Moore was not interested in paying a “second mortgage” for child care—and neither was her sister, Karla Hicks. Following Moore’s advice, Hicks applied for the Care 4 Kids subsidy in September of 2022 and was approved within a month, just before the annual wave of fall applications. Hicks attributes her acceptance to the good fortune of insider knowledge: “If you don’t know about [Care 4 Kids] on your own, you would never know about it.”

Jameila McKee, a full-time working mother of two infants and a New Haven resident, also found Care 4 Kids’ uncertain process to interfere with her job. In McKee’s experience, the stress was not only in affording daycare but also in finding an available one. McKee’s Care 4 Kids application was a several-month-long process that could not begin until after her acceptance and commitment to a daycare, many of which have sizable waitlists. McKee was working full time and struggled to simultaneously tour daycares and continue paying her bills. While daycare providers aim to uphold their commitment to foster partnerships between educators and parents, not every parent can afford to take on their part of that commitment.

Another New Haven parent, Asia Huff, had heard of Care 4 Kids, but her knowledge of the program was limited until after giving birth, when a woman started visiting with check-ins, plug covers, pantry items, gift cards, and the suggestion that she apply. The woman was an agent for the Nurturing Families Network, a state-funded program that strives to work collaboratively with “high-risk first-time parents” by providing educational and emotional relief. Free of charge, she supported Huff postpartum, including advising her on the Care 4 Kids application. “Without the woman that comes to visit me, I would be lost,” Huff told me.

The parents I spoke with emphasized how Care 4 Kids is wrapped in an implicit exclusivity—and these barriers to entry complicate its mission to help families most in need. Each of the mothers I spoke with—Moore, Hicks, Huff, and McKee—shared an anticipation for the glory age of 5 when they could finally defer to the public school system to receive guaranteed state-funded education. Only then will they no longer have to strictly budget their family finances just to ensure their children are cared for.

After Class

Ultimately, educators and parents alike seem to realize the only way to achieve more state and national support—including

desperately needed financing—is to advocate for themselves, time and time again.

Over the last few years, the pandemic compounded frustrations that had always existed among parents and educators. In 2021, Connecticut received $346 million in federal COVID-19 relief funding, dedicated specifically to providing operational support for stability and expansion in the childcare industry. But that one-time funding has now dried up. Meanwhile, childcare professionals risked their lives daily to uphold their commitments to their students and their communities, as well as the broader economy. There was no better opportunity for the state to show its appreciation than the 2022-2023 Biennial Budget Report, the first iteration of which was approved by the legislature in 2021.

A year later in February of 2022, upon the release of forecasted budget adjustments, Goldburn waited three days to allow the policy team at the Connecticut Voices for Children and Connecticut Early Childhood Alliance to analyze childcare centers’ budgets. The Alliance confirmed her worst fears: Connecticut legislators had allocated no additional funding to support the industry. In the next two weeks, Goldburn and her colleagues—Bermúdez Zimmerman from Child Care for Connecticut and Schiavone, along with other providers and policy experts representing childcare centers, coalitions, and universal child care campaigns across the state—mobilized. On March 15, 2022, three hundred and fifty childcare professionals, parents, and their children staged a “Morning Without Child Care” demonstration on the New Haven Green from 8 a.m. to 9 a.m. Goldburn and her colleagues stepped away from their work lives to demonstrate what would happen if the childcare industry withdrew their services, even if just for an hour.

“We struggled about removing what [families] need to survive to ‘punish’ or raise awareness for decision-makers,” Schiavone said about the ethical dilemma of hitting pause on the workforce. Educators feared if they had not called people to action, no one would have.

The action worked. In May of 2022, Connecticut boasted a shiny new armistice: “The biggest investment in child care [and] education… in our state’s history.” The amended 2022-2023 biennial budget report allocated $183 million to the early childhood education industry, a more than twofold increase in what they had been previously receiving from the state. “There was a straight line between what we did in that rally and what was put in the budget,” Goldburn told me. And still, this figure represented just a quarter of the investment needed for survival.

The message of the first “Morning Without Child Care” rally in 2022 resonated with childcare providers, parents, and families nationwide. Advocates in Connecticut more than doubled their state’s investment in early childhood and

saw legal recognition from President Biden as he issued an executive order to support affordable care and quality jobs for care professionals. The work of Goldburn and her colleagues reignited within a nationwide effort on March 8, 2023— International Women’s Day—demanding an equitable and just care system. Schiavone said that this second effort “solidified us [childcare professionals] as workers that could turn out constituents. It brought us together as a community in ways we’ve never been connected.” In this second wave of rallying, advocates were motivated by the residual unfulfilled costs from the previous fiscal year and the latest budget report released in February which boasted what Goldburn described as mere “marginal increases.”

The 2024-2025 state budget added $67.5 million to Care 4 Kids, an 11 percent increase since the initial forecast which was projected to account for seventeen thousand children statewide. But there were still 18,384 unenrolled children to be accounted for who were left without child care upon the forced closures of 11.3 percent of classrooms that could not afford to stay open as of this past May. So while more money was made available to providers amid the withdrawal of federal COVID-19 relief funding, supply remained limited. With fewer openings, families who could pay the competitive rates of child care out of pocket would take precedence over those who could not. Ultimately, the names of the families with the least means would be the ones collecting dust on the waiting lists.

Change is about turning power over to the early childcare workforce, one that has been long neglected and underestimated. The Connecticut legislature recently passed a bill that would push the eligibility for kindergarteners so that a third of children born in 2019 would have their enrollment delayed into elementary school. The educational system skeleton is delicate and disjointed. The additional strain this would place on educators and parents speaks volumes about who should get to decide the flow of money and resources in this industry. Nonetheless, there will be educators who show up to their jobs so that everyone else can show up for their communities, even when it brushes the impossible.

Bermúdez Zimmerman raised the proposition of a flexible spending account, ideated by those at the Child Care for Connecticut’s Future coalition. In April, Governor Lamont issued an executive order to initiate a Blue Ribbon Panel on Child Care made up of parents, educators, and legislators that would be charged with developing a five-year strategic plan for the childcare system. The American Rescue Plan is set to issue another round of funds for Connecticut’s cities.

At the time of publication, $10 million is slated to be allocated to New Haven’s youth, and the city intended to reserve $3 million for child care, to be partly administered by Goldburn’s

advocacy non-profit organization CERCLE, a component of Hope for New Haven.

“This is the beginning of a conversation,” Bermúdez Zimmerman told me.

Establishing some type of trust or giving private businesses public features are other ways in which people could orient their solution-forward thinking. Bermúdez Zimmerman gave the example of a quasi-public structure, which would provide private programs with a public mandate to deliver their services. Converting money and power into the hands of industry professionals would make it so that “legislature does not have authority to dip their hands into whatever they want,” according to Bermúdez Zimmerman. Early childhood educators are entrusted with the lives of the community’s children daily, they should also be entrusted with their financial independence.

“I’m more optimistic than I’ve ever been,” Bermúdez Zimmerman admits. “The last two years have been the most fruitful in getting legislators to pay attention. Things are tough now, but we’re doing our work.” ∎

By Audrey Coombe

By Audrey Coombe

Connecticut’s commutation policy offers incarcerated individuals a second look and a chance at a shortened sentence. But what does it take to get there?

Darrell Atkinson’s hands trembled as he carved at the metal bar, sharpening it till it was a kind of knife. “Forever My Lady” by Jodeci dragged through the air, cranked out over 94.3 WYBC. Up until that day, he still had hope. He had spent two years in the jail on Whalley Avenue and at Northern Correctional Facility, Connecticut’s only supermax prison, awaiting his day in court. He’d rejected a plea bargain of forty-eight years and instead insisted on a jury trial, maintaining his innocence. But that day, March 4, 1994, he was found guilty and sentenced to ninety years in prison.

That night, the first night of his lifelong sentence, he held the makeshift knife to his chest. He closed his eyes and saw the face of his mother. The look on her face said: Boy, don’t you do it. He sighed, dropping the knife. He had four children—three sons and a daughter—and he wanted to see them grow up. He wanted to be able to hold them again someday.

Twenty-nine years later, Atkinson’s voice grew softer as he told me about his family, and about how painful it was not to see them for the thirty-one years he served in prison. I’m the second person to learn of his attempted suicide, he said. The first was his mother, who died while he was incarcerated.

Atkinson is out of jail, now—living in a halfway house, speaking with me—because of Connecticut’s commutation policy. He was one of the 106 people in Connecticut to receive a sentence commutation since December 2021, reducing his sentence by fifty-nine years.

While Atkinson knows it as the tool that gave him his freedom, Connecticut’s commutation policy has proven both contentious and precarious. In just the past five years, the process has been halted and amended with stricter parameters multiple times. Debates between victims’ advocates, incarcerated people, lawyers, and political figures configure commutations in a perpetual state of flux—seemingly straddling the lines between justice and injustice, rehabilitation and punishment.

In Connecticut, people like Atkinson those incarcerated for certain violent crimes including felony murder—are ineligible for parole. Instead, incarcerated individuals serving lengthy sentences have several avenues for amending their sentence. The first option, and probably the most difficult, is a direct appeal within thirty days of a conviction. The second is to file a habeas corpus, a petition for a new trial. The third is a sentence modification, which is decided by a judge. And the fourth is a sentence commutation.

A sentence commutation, rather than an appeal or habeas, does not reverse a conviction.

But the chances of winning an appeal are low: Atkinson filed multiple habeas corpus petitions for an appeal while incarcerated, in both cases arguing ineffective counsel. Each time, a judge denied his petition.

The crux of the debate around commutations lies in whether or not individuals convicted of violent crimes deserve a second look. Miriam Gohara, a Clinical Professor of Law at the Yale Law School, said that second-look statutes—like parole or commutations—are not a constitutional right in the same way that the right to a jury trial is. “It’s purely discretionary,” Gohara said. “But it’s so critical as a safety valve.”

When a judge hands down a sentence, Gohara said, they cannot know whether a sentencing standard will hold up over time. In 2012, for instance, the Supreme Court ruled in Miller v. Alabama that life without the possibility of parole for juveniles was unconstitutional for non-homicide crimes and could not be mandatory for homicide crimes. Additionally, Connecticut abolished the death penalty for future crimes in 2012 but continued to have eleven men on death row until 2015, when the Connecticut Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional. In other words, judges rely on second-look provisions to know that a sentence can be changed if circumstances beyond the crime itself change.

Over time, sentencing standards for the same types of crimes have gotten shorter. Given that a significant percentage of the prison population in Connecticut was sentenced decades ago, this means if they were to commit the same crimes today, they might receive a much shorter sentence. There are about half as many people incarcerated in Connecticut today as there were fifteen years ago, with a little more than ten thousand today compared to about twenty thousand in 2008.

In other states, the power to commute a sentence typically resides with the governor of a state. But in Connecticut, that power is instead held by the Board of Pardons and Paroles, whose members are appointed by the governor and have experience in social work, law enforcement, criminal justice, or substance abuse treatment and prevention. When deciding whether to commute a sentence, the Board previously considered factors including the seriousness and recency of a conviction, the incarcerated individual’s conduct while serving their sentence, the impact on victims and the community, the extent of the individual’s rehabilitation, whether the length or form of the individual’s sentence is consistent with contemporary sentencing standards, and the extent to which continued service of the individual’s sentence is in the interest of justice.

In order to apply for a commutation, incarcerated individuals must have served at least ten years of their sentence. And, Atkinson’s attorney Alexander Taubes LAW ’15 said, if you get denied, you have to wait another five years before applying.

Incarcerated individuals thus have to decide which types of sentence modifications to apply for and in what order, in case having been denied for one hearing might prejudice them in the other.

In the early nineteen-nineties, Connecticut legislators removed the possibility of parole and good time credits for homicide offenses, which includes felony murder. That means the only option available to a majority of the people serving lengthy sentences—which tend to be for violent crimes—is a sentence commutation. These commutations are, in criminal justice professor at the University of New Haven and former state legislator Michael Lawlor’s words, the “extraordinary” option.

Taubes represented forty-three of the 106 sentences that were commuted between December 2021 and April 2023. In total, his clients had 751 years taken off their sentences, with an average of 17.5 years.

These victories were largely unprecedented. Previously, from 2016 to 2021—including a hiatus in 2019 and 2020 to reevaluate the commutation process—the state had averaged only one commutation a year. Many advocates both for and against the state’s commutations policy attribute the jump to a natural increase in applications following the pause, but this rise in commutations raised alarm bells for some.

The push against commutations for violent crimes picked up at the start of 2023, with some victim advocates and several Republican legislators advocating for limiting commutations to non-violent crimes. In March, Governor Ned Lamont replaced the chair of the Board— who some legislators felt was too liberal when commuting sentences—with Jennifer Medina Zaccagnini, a former social worker who served on the board since 2008. Lamont also suspended commutations entirely while the Board reviewed its policies, following pressure from Republicans and some victims’ families.

Part of the outrage was because forty-four of the seventy-one sentences commuted in 2022 were for murder. For people like Atkinson— those serving lengthy sentences without the possibility of parole—a sentence commutation can seem like the only shot at freedom. And as Lawlor suggested, the minimum of ten years served for eligibility explains why so many of the commuted sentences are for violent crimes: the people applying for a commutation have to be serving a long enough sentence to begin with.

“How are you supposed to have a second chance on anything at life if people want you to get out of jail when you’re 80, 90 years old?” Atkinson said. “They’re just clearing the path for your funeral.”

The uptick in commutations sparked concern from some victims’ families, who worried their own perpetrators would be released from prison. The Board of Pardons and Paroles notifies the family of homicide victims of the application, even if the hearing ends up being denied. The board also takes into consideration statements from the victim’s family and prosecutors.

Plea bargains—which often include waiving the right to appeal—further complicate the avenues through which incarcerated individuals can have another chance at freedom. Some victims’ families feel that commutations undermine the strength of these plea bargain stipulations, acting as a loophole for freedom.

“It can almost be insulting to them because it’s like a contract,” said Jessica Pizzano from Survivors of Homicide. “‘[The accused individual] willingly accepted their sentence, and then to turn around how many years later and change that is extremely difficult for our families.”

“How are you supposed to have a second chance on anything at life if people want you to get out of jail when you’re 80, 90 years old?” Atkinson said. “They’re just clearing the path for your funeral.”

Survivors of Homicide is a Connecticut-based, nonprofit organization that provides support and advocacy to anyone connected with a homicide victim. Pizzano stressed that the organization is apolitical with the sole goal of providing support to its members. Pizzano also emphasized that most of the families the organization works with do not have a problem with commutation hearings as a whole, but do believe that violent crimes like murder, sexual assault, and felony murder should be excluded from commutations.

Today, murder charges often come with shorter sentences, or the charge itself may be lowered to manslaughter or felony murder, Pizzano said. “That’s very hard for our families right now to be told that due to the current trends, this is the sentence that we can give,” Pizzano said. “Fifteen years for killing someone, that doesn’t sit well with our families.”

Over the last few months, the Board met with various stakeholders on both sides in order to develop a new commutation policy. On August 30, the Board heard three cases in its first commutations hearings since the pause. All were for murder convictions from the mid-nineties. And one, Miguel Sanchez, was granted a commutation. Sanchez had been incarcerated since 1997 and the Board reduced his sentence by fifteen years, bringing his new effective sentence to forty-five years.

Attorney David Bothwell, the legislative and administrative advisor to the Board of Pardons and Paroles, said the Board is now

looking for individuals to show “extraordinary and compelling” circumstances towards rehabilitation, beyond participating in programs the Department of Correction offers. This is the main change to the policy. Victim input, the nature of the crime, and the seriousness of the individual’s involvement will also continue to be taken into consideration.

The new policy is vague to a fault, Taubes said.

More critically, it raises the issue of what rehabilitation means in a prison setting. How does someone who maintains their innocence demonstrate accountability for a crime they may not have committed? And can a prison environment really allow for “extraordinary and compelling” forms of rehabilitation?

Atkinson grew up in the Hill, a neighborhood composed mainly of Black and Hispanic residents just south of downtown New Haven. When he was 3 years old, his mother picked him up and walked to her sister’s two streets down. She put him down on the porch steps, rang the doorbell, and walked away. Atkinson stayed with his aunt for a day before she called the Department of Children and Families. For the next twelve years, he bounced around foster homes and group homes. His mother never knew that he lived just a few streets down for most of that time. He walked past her once, when he was 14, at the King’s Department Store. She didn’t recognize him. It felt like a gut punch.

A year later, Atkinson ran away from a group home in Massachusetts. When he arrived at his mother’s home, she pulled him in. They sat for hours, running over everything that had happened. “Why did you give me up?” he asked her. She told him that she hadn’t been ready to be a mother.

How does someone who maintains their innocence demonstrate accountability for a crime they may not have committed? And can a prison environment really allow for “extraordinary and compelling” forms of rehabilitation?

Over time, Atkinson felt like he could go to his mother for anything. She was a stern woman, someone you wanted as a friend but not as an enemy. He picked some of that up from her, he said, but he was also committed to softening his anger so he could make her proud.

When Atkinson was 17, he met Michelle, who was a few years older than him. She came up to his bedroom window to get his attention on behalf of her friend. Right away, he found her “intoxicating.” A few days later, his mother called out to him from the front door. There was a girl at the door for him: Michelle. “She was the love of my life,” he said. “And I don’t throw that word love around.”

At 18, Atkinson had his first son, Bobby. Michelle told Atkinson he had to get serious—he couldn’t keep getting in trouble for petty crimes.

But Atkinson, at the time in his late teens, frequently found himself face-to-face with cops. The Hill has historically had the highest number of people in New Haven living below the federal poverty line. Atkinson recalls the police making frequent rounds in the area. In the late nineteen-eighties, this was far from unusual: intentional policies pushed from 1970 onward had brought about the era of mass incarceration in the U.S., as legislators pushed for stricter sentencing laws, tough-on-crime policing—which targeted primarily Black and Brown neighborhoods—and growing prison populations. From 1970 to 1985, the national prison population rose from 196,429 to 502,507, according to data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics’s Prisoners series.

Connecticut was no exception to this national trend. In 1968, Connecticut established the Department of Correction—the first central authority in the nation to oversee all youth and adult correctional institutions and parole functions in the state. Connecticut’s prison population grew rapidly, in part due to legislating definite sentences and eliminating parole for crimes committed after July 1981. Between 1980 and 1990, the incarcerated population doubled, the number of prison staff tripled, and the DOC budget quadrupled.

“How am I supposed to return? To love you?” Atkinson paused—it isn’t an easy subject. His instinct was to protect himself, to resist the mother who had once abandoned him. I asked him how he was able to forgive her.

All families are complicated, he said. But when you make it back home, when you walk through the door, you feel like you’re 2 years old again, running into your parents’ arms. “I always wanted to be loved by my family; I didn’t want to leave this earth not feeling loved,” Atkinson said.

Those effects are still felt today. An October 2022 report by the Prison Policy Initiative on redistricting data in Connecticut found that six cities— Hartford, Waterbury, New Britain, Bridgeport, New London, and New Haven—were home to over half of the state’s incarcerated population, despite making up only 17 percent of Connecticut’s total population. High incarceration rates disproportionately affect Connecticut’s communities of color: in April 2020, the DOC reported that 44 percent of the prison population was Black, while only 13 percent of Connecticut residents are Black.

Atkinson served his first prison sentence at age 19, a fifteen-month sentence for drug-related charges. After being released, in November 1991, Atkinson was ready to turn his life around. He

wanted to commit himself to looking after his four kids, finding a consistent job, and making his mother proud.

But on February 29, 1992, the police were at Atkinson’s door again. The body of a young man named Edward Moore had been found in the Roberto Clemente field on February 27, the two detectives standing before Atkinson—New Haven Police Department officers Joe Greene and James Ponteau— thought he had something to do with it.

“I always wanted to be loved by my family; I didn’t want to leave this earth not feeling loved,” Atkinson said.

According to the affidavit for Atkinson’s arrest, a friend of Moore told police that a man approached them and then walked quickly ahead of them. Three other men, all in masks, ran up and robbed Moore and his friend at gunpoint. While Moore’s friend was on the ground, he heard two gunshots. He got up and ran, and heard another gunshot go off in his direction. Police later received a tip that Atkinson was involved, although the affidavit does not mention from whom that information came or how the informant knew it.

Police interrogated Atkinson, who said he had been at the field with the other men, but left when they suggested robbing Moore. Atkinson told police he learned of Moore’s death on the TV at home. An eyewitness later identified two of the subjects, one of whom she said was unmasked; neither of whom was Atkinson. Atkinson claims the police fed him information about the crime during the interrogation. The affidavit notes that they read Atkinson his constitutional rights midway during the police interview. But Atkinson believes the fact that he had a criminal record and that the police knew who he was mattered.

Atkinson was arrested alongside two co-defendants for Moore’s robbery and death. Police could not establish who shot Moore, so Atkinson was charged with felony murder, robbery in the first degree, conspiracy to commit robbery, and attempted assault. The felony murder rule allows anyone accused of committing a dangerous felony to be charged with first-degree murder for a death that occurs during the felony, even if the defendant was not the killer.

But Atkinson maintains that he was not there for the crime at all. According to reporting by Will Sutherland, Ryan Myers, one of Atkinson’s co-defendants, also maintains his innocence but made the choice to take an Alford plea—a rare type of guilty plea wherein the defendant does not admit to committing the crime—for a shorter sentence. Detective Greene had been implicated in cases of wrongful arrest and improper investigation in the past. This includes a federal civil rights case against

him and another detective, Michael Sweeney, in August 1991 for false arrest and malicious prosecution. Eric Ham, who had brought the case, was awarded nearly one million dollars.

Between December 2021 and April 2023, the commutations policy was more generous, Taubes said, including a more liberal view of accountability. Taubes represented four clients during that period who applied for a sentence commutation while they had habeas corpus actions in court— in other words, they continued to maintain their innocence. All four commutations were granted.

Although Atkinson did not have a habeas petition at the same time as his commutation hearing, his application package includes several letters from family and friends that emphasized their belief in his innocence. On August 30, at the first commutation hearings since the pause, another of Taubes’ clients, Corey Turner, had his application denied in part because he had a habeas corpus action and was still maintaining his innocence. Turner’s case appears to break a pattern in how accountability and rehabilitation are considered by the Board, although it is difficult to say for certain what that means for potential wrongful convictions.

Incarcerated people who say they have been wrongfully convicted must make a difficult choice: maintain their innocence and potentially remain behind bars, or accept responsibility for something they didn’t do in order to earn their freedom.

“So much of the talk about rehabilitation and change and transformation comes around the notion of the person accepting responsibility for the crime, and how can you accept responsibility for the crime if you maintain your innocence?” Taubes told me. “But that question goes both ways. How do you expect someone to take responsibility for something they didn’t do?”

The new commutations policy means that many more people may have to face this dilemma. According to Taubes, the traditional view in sentence reductions is that maintaining your innocence can be held against you. Incarcerated people who say they have been wrongfully convicted must make a difficult choice: maintain their innocence and potentially remain behind bars, or accept responsibility for something they didn’t do in order to earn their freedom.

At the beginning of Atkinson’s sentence, he struggled.

“I was younger back then,” he wrote in his commutation application, “and very immature, and I did very stupid things.”

For Atkinson, rehabilitation meant accepting that the life he’d been living before his arrest needed to change. Though he maintains that he was not involved in the murder, he asserts that he knew he had to do more in order to be a father to his kids.