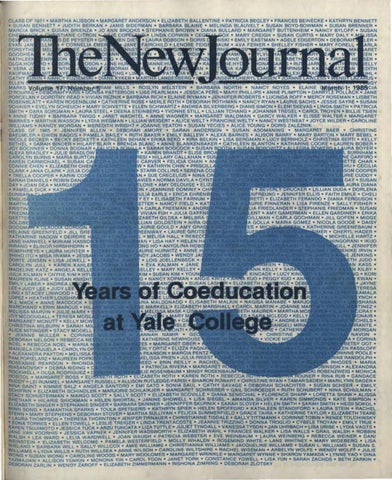

CLASS OF 1971 • MARTHA ALISSON • MARGARET ANDERSON • ELIZABETH BALLENTINE • PATRICIA BEGLEV • FRANCES BEINECKE • KATHRYN BENNETT • SUSAN BENNETT • JUDITH BERKAN • JANIS BIDERMAN • BARBARA BLAINE • MELINDA BLAUVELT • SUSAN BOYD-BOWMAN • SUSAN BRENNER • MARCIA BRICK • SUSAN BRIENZA • JO ANN BROOKS • STEPHANIE BROWN • DIANA BULLARD • MARGARET BUTTENHEIM • NANCY BYLOFF • SUSAN CHE' E CITRON LINDA CORWIN • C • MARY CREIGH • SUSAN CURTIS • MARY DALY • E PEYSTER • • LAURA DOBSON • • EMILY EASTMAN • ADELE EDGERTON • uo::.ou•"""•n CORNELIA E FAIRCHILD • LEN • AVA FEINER • SH FISHER • KATH OLGA • VER KAUFM CATI ELLE'. ,. .~~~~jij~~ijj~~~ijijM~~ji-.~~~~~ MARK:> \fof~ lf'JR~~~~IAM MILLS • ROSLYN MELSTEIN • BARBARA NORTH • NANCY NOYES • ELAI O'ROURKt.-DI:'BORAH'PA'roS'el>"CiNRA PATTERSON • LiSE PEARLMAN • JESSICA PEAS • MARY PHILLIPS • ANNE PLIMPTON • E PORCELAN • DOROTHY READ • VIVIAN REZNIK • BARBARA RICH • ELAINE RIVMAN • JENNIFER ROBERTS • LUCINDA ROFF • MERCY ROSEMAN • LISBETH ROSENBLATT • KAREN ROSENBLUM • CATHERINE ROSS • MERLE ROTH • DEBORAH ROTHMAN • NANCY RYAN • LAURIE SACHS • JESSIE SAYRE • SUSAN SCHAIER • EVELYN SCHEUCH • MARY SCHVETTE • ELLEN SCHWARTZ • ANDREA SILVERBERG • DIANE SIMON • ELENI SKEVAS • LINDA SMITH • PATRICIA SMITH • DARA SORGMAN • LAURA STEEL • DEENA STEINBERG • YVONNE STILL • LILLIAN TCHANG • JOHANNA TREGEL • CAROL TROYEN • BILLIE TSIEN • ANNE TUOHY • BARBARA TWIGG • JANET WACHTEL • ANNE WAGNER • MARGARET WALDMAN • DARCY WALKER • ELISSE WALTER • MARGARET WARN ES • MARTHA WASSON • LYDIA WEGMAN • LILLIAN WEIGERT • ALICE WELT • FRANCINE WELTY • NANCY WESTNEAT • JOYCE WILDER • CAROLINE WILLIAMS • NANCY WORGAN • MEREDITH WRIGHT • JOANNE YEATON • SUSAN YECIES • ALICE YOUNG • DORIS ZALEZNIK CLASS OF 1985 • JENNIFER ALLEN • DEBORAH AMORY • SARAH ANDERSON • SUSAN ASOMANING • MARGARET BAER • CHRISTINE BAEUMLER • GWEN BAGGS • PAMELA BAILEY • RUTH BAKER • EMILY BALLEW • ALEXA BARNES • ALISON BARRY • MARY BARTON • MARY BEBEL • NICOLE BECKER • BECKY BECKETT • KATHLEEN BEHAN • ERIKA BEKO • KIRA BELKIN • LISA BERGMAN • LUCY BERNHOLZ • CHRISTINA BERTI • KELLY BETHEL • SARAH BINDER • HILARY BLANC • ANNE BLANKENBAKER • LEEN N • KATHARINE COOKE • BOBER • • SARAH BOOCOCK • R• JOY BOCHNER • DONNA BODNAR • ALEXA BRADLEY • JULIE BRADLOW KAREN BRANDT • Ell CAROLYN BURNS • MARIA • HILLARY CALLAHAN KAREN CARMICHAEL • SUSAN • FELICIA CHAN CONNIE CHEN • ELIZABETH CH CHIN • ""'""~·•uu CLARK • JANA CLARK • JULIA COLLINS • SUE CRECELIUS • N • TRELLA COOPER • KARIN SARAH DANIELS • ROBIN ES • NORMA DAVILA • DAY • JOAN DEA • • AMY DELOUISE • JEANNINE DOMINY • • PAMELA DICK • A EARLE • ERICA EHREN • ELISABETH FARNUM • NANCY FIELD • • CARLA FREEMAN • VIVIAN FUH • JULIA GILDEA • MI::LC•M. . GOODM HELAINE GREENFELD KATHARINE HADOW • DEIRC,RE JANE HARWELL • MIRIAM H HIRANO • ELINOR HIRSHHORN • HUMPHREYS • LAURA HUNTER • SHIHO ITO • MISA IWAMA • DORTE JENSEN • LISA J CAROLYN JULL • KAREN MADELINE KATZ • ANGELA KE JULIA KILMAN • CHYHE KIM • H MAUREEN KLINE • SUSAN KNIG EMILY LABER • ANDREA L,.•u- · LEE • JUDY LEE • JUDY UNG • STACEY LINWOOD LOPEZ • HEATHER LOUGHR. M J MACE • ANNE MADDOCK • MARCHAND • ERIN MARCUS • MELISSA MARVIN • JULIE MARX JOY MCDOUGALL • TERESA M MARGARET MCNUTT • KELLY M CHRISTINA MILBURN • SARAH AUCE MITINGER • STACY "'"Juo~LL " JEANNE MULLER • CORIN DEBORAH NELSON • REBECCA N NA NOEL • REBECCA NOEL • MARIA OOT • MANUELA ORJUELA • CAROLYN PASSLOFF • ALEXANDRA PAXTON • M INNE POOLE • RANDOLPH • PAM POPIELARZ • MAUREEN DES • MARIA ROSEANNE REARDON • RH RIASANOVSKY • DEBRA RIDING • • ALEXANDRA ROCKWELL • OLGA RODRIGUEZ • ROSENZWEIG • MONICA ROSITOL • MARGARET ROSS • ROTH • KAREN ROTH • REBECCA • RINA RUB • CANDACE RUDDY • LEI RUMMEL • MARGARET RUSSELL • ALLISON RliTLEDGE·PARISI • SHARON RUWART • CHRISTINE RYAN • TAMAR SADEH • MARILYNN SAGER • N NA SAINT • KIMMIE SALZ • ANGELA SANTORO • EMI SATO • SONIA SAUL • CATHY SAVAGE • DEBORAH SCHACHTER • SUSAN SCHEER • • EMILY SCHIFRIN • ELIZABETH SCHINDLER • MARJORIE SCHLAIKJER • MARGARET SCHRIEBER • GAIL SCHROEDER • RUTH SCHUBERT • NINA SCHULMAN • STACY SCHUSTERMAN • MARGO SCOTT • SALLY SCOTT • ELIZABETH SCOVILLE • DIANA SENECHAL • FLORENCE SHARP • LORETTA SHAW • ALISSA SHETHAR • HILARIE SHICKMAN • HELEN SHORTAL • JANINE SHOWELL • LISA SIEGEL • AMANDA SILVER • KAREN SIMMONDS • KATE SIMPSON • ELIZABETH SINGER • STEPHANIE SINGER • BARBARA SKINNER • JENNIFFER SKURNIK • SARAH SLOVER • HELEN SMITH • SARAH SMITH • HEIDI SOKOL • M NN SONG • SAMANTHA SPARKS • TOULA SPETSIERIS • KATHRYN SPIER • HELEN SPOFFORD • KATHLEEN STANDIFORD • LAURA STEIN • RACHEL STENN • MARY STEPt1ENS • DEBORAH STOVER • MARTHA SULLIVAN • FELICIA SUMMERFIELD • GRACE TAIRA • KATHERINE TAYLOR • ELIZABETH TEARE • LAURA THOMPSON • THERESA THORNTON • JENIFER TIRNAUER • CHRISTIANNE TISDALE • SALLY TITTMANN • CORINNE TOBIN • RENEE TOLCHINSKY • EDNA TORRES • ELLEN TOWELL • LESLIE TREIGER • LINDA TRENTACOSTE • JEANNIE TRIZZINO • DONNA TROGLIO • CYBELE TROYAN • EMILY TRUE • KAREN TSUJIMOTO • JESSICA TUCK • ARZU TUNCATA • LIZA TUTTLE • JULIET TYNDALL • VANESSA TYSON • JAN UHRBACH • LISA URIBE • LYDIAVAGTS • JANE VAN VOORHIS • JESSICA VAPNEK • JENNIFER WADSWORTH • ELIZABETH WAHL • FRANCES WALKER • LISA WALLS • GRAIL WALSH • ROBBIN 'IIALSH • LEA WARD • LELIA WARDWELL • JOAN WAUGH • PATRICIA WEBSTER • EVE WEINBAUM • LAURA WEINBERG • REBECCA WEINER • DANI E NSTEIN • ELIZABETH WELCOME • PAMELA WESTERFIELD • MOLLY WHALEN • ROSEMIND WHITE • LANE WHITNEY • MARY WIDE BERG • LISA W ELAND • BARBARA WILL • SALLy WILLCOX • AMIE WILLIAMS • CHRISTIANNA WILLIAMS • JACQUELINE WILLIAMS • SUSAN L WILLIAMS • SUSAN S 'W LLIAMS • LYDIA WILLS • RUTH WILLSEA • ANNE WILSON • CAROLINE WILTSHIRE • RACHEL WISEMAN • ARBELYN WOLFE • WENDY WOLFF • JULIE WoNG • SUSAN WONG • CAROLINE WOODS • MARY WOOLOMES • MARGARET WRINKLE • MARGARET WYNNE • SHARON YAMADA • lYNNE YAO • DINA YAZMAJIAN • ALLISON YENKIN • MONONA YIN • CAROL YOON • JANET YORK • CONSTANCE YOWELL • USA YUN • SARAH ZACHOS • BETH ZARKIN • DEBORAH ZARUN • WENDY ZAROFF • ELIZABETH ZIMMERMANN • RISHONA ZIMRING • DEBORAH ZLOTSKY

Issuu converts static files into: digital portfolios, online yearbooks, online catalogs, digital photo albums and more. Sign up and create your flipbook.