MARK WHITE FINE ART

Mark White, Malibu Broad Beach 24 x 36, Oil on Canvas

Mark White, Malibu Broad Beach 24 x 36, Oil on Canvas

To draw does not mean simply to reproduce contours; drawing does not consist merely of line; drawing is also expression, the inner form, the plane, modeling. See what remains after that.

— Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867)

Celebration of fine art

Visit celebrateart.com

Live Event: Jan. 14–Mar. 26, 2023 | Open Daily 10am–6pm Loop 101 & Hayden rd, Scottsdale, Az 480.443.7695

Learn about our juried artists, view their work and add to your collection by experiencing our show virtually at celebrateart.com.

Where Art Lovers & Artists Connect

Pete Tillack, Stolen Moment, 34 x 40 in.

Pete Tillack Stolen Moment 34 x 40 in.

Pete Tillack, Stolen Moment, 34 x 40 in.

Pete Tillack Stolen Moment 34 x 40 in.

PUBLISHER

B. Eric Rhoads bericrhoads@gmail.com Twitter: @ericrhoads facebook.com/eric.rhoads

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

MANAGING EDITOR

Peter Trippi peter.trippi@gmail.com

917.968.4476

Brida Connolly bconnolly@streamlinepublishing.com 702.665.5283

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Matthias Anderson A llison Malafronte

Kelly Compton Da vid Masello

Max Gillies Louise Nic holson

Daniel Grant Char les Raskob Robinson

DESIGN DIRECTOR

Kenneth Whitney kwhitney@streamlinepublishing.com 561.655.8778

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Alfonso Jones alfonsostreamline@gmail.com 561.327.6033

DIRECTOR OF SALES & MARKETING

Katie Reeves kreeves @streamlinepublishing.com

VENDORS — ADVERTISING & CONVENTIONS

Sarah Webb swebb@streamlinepublishing.com

PROJECT MARKETING SPECIALIST

Christina Stauffer cstauffer @streamlinepublishing.com

SENIOR MARKETING SPECIALISTS

Dave Bernard dbernard@streamlinepublishing .com

Michael George mgeorge @streamlinepublishing .com

Megan Schaugaard mschaugaard@streamlinepublishing .com

Jennifer Taylor jtaylor@streamlinepublishing .com

Gina Ward gward@streamlinepublishing.com

MARKETING COORDINATOR

Brianna Sheridan bsheridan@streamlinepublishing .com

SALES OPERATIONS SUPPORT

Katherine Jennings kjennings@streamlinepublishing .com

EDITOR, FINE ART TODAY

CherieDawn Haas chaas@streamlinepublishing.com

through May 14

Old Lyme, CT • FlorenceGriswoldMuseum.org

Edmund Greacen (1876-1949), The Lady in the Boat (detail), 1920. Oil on canvas. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company

Edmund Greacen (1876-1949), The Lady in the Boat (detail), 1920. Oil on canvas. Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company

Painting the Faces of Chautauqua

by Katherine Galbraith, PSSOpening Reception November 11, 2022 from 5-8pm

The Westfield Train Station, Westfield, New York 14787

CHAIRMAN/PUBLISHER/CEO

B. Eric Rhoads bericrhoads@gmail.com Twitter: @ericrhoads facebook.com/eric.rhoads

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT/

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER

Tom Elmo telmo@streamlinepublishing.com

CHIEF REVENUE OFFICER

Jim Speakman jspeakman@streamlinepublishing.com

PRODUCTION DIRECTOR

Nicolynn Kuper nkuper@streamlinepublishing.com

DIRECTOR OF FINANCE

Laura Iserman liserman@streamlinepublishing.com

The exhibition will showcase more than 30 portraits of residents of Chautauqua County, NY, including fire fighters, teachers, lawyers, farmers, children, and grandparents. All are people who ordinarily would never have their portraits painted. Each portrait is 14x11”, on wood panel, painted from life in one 3 hour sitting.

Enjoy the art, conversation, and ambiance of the historic train station. For more information, please contact: Katherine@KatherineGalbraithFineArt.com

katherinegalbraithfineart.com

CONTROLLER

Jaime Osetek jaime@streamlinepublishing.com

STAFF ACCOUNTANT

Nicole Anderson nanderson@streamlinepublishing.com

CIRCULATION COORDINATOR

Sue Henry shenry@streamlinepublishing.com

CUSTOMER SERVICE COORDINATOR

Jessica Smith jsmith@streamlinepublishing.com

ASSISTANT TO THE CHAIRMAN

Ali Cruickshank acruickshank@streamlinepublishing.com

Subscriptions:800.610.5771

Also 561 655.8778 or www.fineartconnoisseur.com

One-year, 6-issue subscription within the United States: $39.98 (International, 6 issues, $76.98).

Two-year, 12-issue subscription within the United States: $59.98 (International, 12 issues, $106.98).

Attention retailers: If you would like to carry Fine Art Connoisseur in your store, please contact Tom Elmo at 561.655.8778.

005 Frontispiece: Alexandre-JeanBaptiste Hesse

018 Publisher’s Letter

022 Editor’s Note

025 Favorite: Suzanne Tucker on Henri Matisse

107 Off the Walls

130 Classic Moment: Burton Silverman

045

ARTISTS MAKING THEIR MARK: FIVE TO WATCH

Allison Malafronte highlights the talents of Marc Anderson, Varvàra Fern, Danny Glass, JuliAnne Jonker, and Angie Redmond.

050

DRESSED TO IMPRESS

By Max Gillies062

NICK BENSON: STONE CARVING & BEYOND

By Thomas Connors066

NORDIC REFLECTIONS: THE MARINE PAINTINGS OF EMIL CARLSEN

By Valerie Ann Leeds074

MARGUERITE LOUPPE: ON HER OWN

By Lilly Wei079

GIVING IT AWAY

By Daniel Grant083

GREAT ART NATIONWIDE

We survey 8 top-notch projects occurring this season.

087 IN LONDON, THE COURTAULD GLOWS BRIGHTER

By Louise Nicholson093 DISCOVERING DUTCH OLD MASTERS IN THE HAGUE

By Peter Trippi097

FLORENCE: WHERE PAST, PRESENT & FUTURE CONVERGE

By Michael J. PearceADRIAN GOTTLIEB: INSPIRATION & HARD WORK

By Peter Trippi

J O V E W A N G

LPAPA Gallery / Artist In Residence / Solo Exhibition

“The Great American West”

Signature Member Jove Wang

Exhibiton Dates: Nov 3rd - Nov 28th, 2022

The sun casts golden light on the mountains near Ghost Ranch as the day fades into the tranquility of night. Painted from a plein air sketch, the radiance is captured in thick, textural strokes of vibrating color.

BRAD TEARE discovered his love for thick paint at a Van Gogh exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum in New York City. Fascinated by the impact of the paintings, Teare began exploring texture and now travels the west painting the landscape in glowing, textured color.

WHAT ARE YOU BUYING, REALLY?

Why is it that an “artwork” designed by a well-known artist — fabricated by a studio of apprentices and untouched by the artist until he signs it — can be sold for millions of dollars?

Is it the concept that makes these works valuable? The signature? The materials? The artist’s “brand”? And why is it that two artists of equal skill and experience can end up so far apart in pricing and collectability?

I have asked around and found that no one can answer these questions definitively, though there are lots of opinions out there. At face value, a painting is worth only what its materials cost at the art supplies store — a canvas, a stretcher, and a few ounces of paint. In fact, that is all the Internal Revenue Service allows a living artist to deduct on her tax return if she donates her painting to a nonprofit organization, like a museum. Where, then, is the value?

Though I cannot speak for other collectors, I believe the artist’s brand is preeminent; it’s about whether experts and collectors harbor that almost emotional degree of trust in the artist’s quality, importance, and consistency. The higher the price, the greater the intangible value above and beyond that sum, and the greater the potential return when it comes time to sell.

Yet it’s so much more than that.

Plein air artists are often asked why their prices are so high when the potential buyer may have watched them paint that very canvas in just two hours. With apologies to Whistler, the correct response is, “You’re paying for two

hours of work and 40 years of experience.” But, of course, the artist’s brand and following also influence that pricing.

Though it’s impossible to specify exactly why an artwork sells, I do know that when you buy a piece of art, you’re usually buying what author Malcolm Gladwell calls the “tipping point” — the accumulation of 10,000 hours of experience or more. You’re buying the artist’s personality and passion, years of mentorship, study, and experimentation, thousands of failures, moments of frustration and joy, and worries about how to make a living.

Today more than ever, we tend to get caught up in status and resale values, when we should actually focus on the fact that art is personal, reflective of the artist who created it, and appropriate for the collector buying it. Unlike most non-essential purchases, artworks are forms of expression and intercommunication that live on long after the maker and the consumer.

Artists are still a special breed, and we must support them if our culture is to endure. Buying their works literally buys them more time to explore, create, and ultimately give other buyers the same pleasure you’re experiencing. And if you buy a historical work, you’re probably supporting a gallerist who has spent his or her life sourcing pieces to enhance clients’ lives.

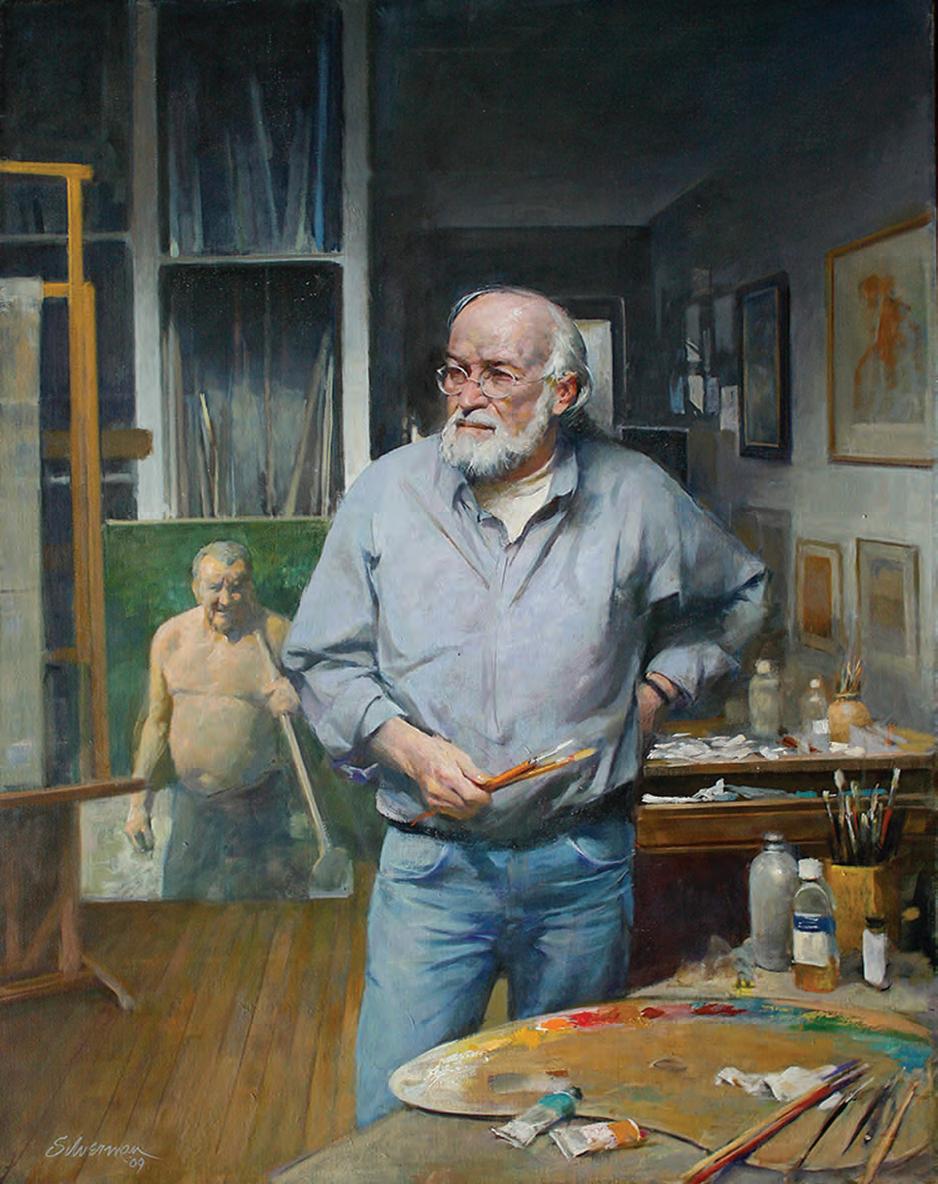

You’re also buying what that artwork does for you. Its stimulation of an emotion or a memory surely is worth more than its investment value, though it’s nice to imagine that someday your heirs may benefit tangibly from that value. (In the meantime, they can enjoy

living with something that delighted you, or they can sell it on and replace it with an artwork they prefer.)

Decades later, I still recall several artworks I failed to purchase promptly. Some I simply could not afford at the time, while others I just never got around to buying. Many times I’ve changed my mind and returned to a gallery, only to find the object of my desire has gone to another collector. Those that I have acquired have made my life richer, which is why I’ve never regretted an art purchase yet.

So what are you buying, really? I’m not sure it can be articulated definitively, but you’ll know it — and feel it — when it happens.

B. ERIC RHOADS Chairman/Publisher

bericrhoads@gmail.com

facebook.com/eric.rhoads @ericrhoads

Wild Now. WILD FOREVER.

The Departure

RYAN KIRBY

SEWE 2023 Featured Artist

FEBRUARY 17-19, 2023 | CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA | SEWE.COM

For more than 40 years, Charleston has hosted one of the most beloved events in the Southeast. SEWE is a celebration of the great outdoors through fine art, live entertainment, and special events. It is where artists, conservationists, collectors, and sporting enthusiasts come together to enjoy the outdoor lifestyle and connect through a shared passion for wildlife. This Is SEWE.

SEEKING AMERICA’S TOP COLLECTORS

Most of the artworks illustrated in this issue have been owned, or will soon be owned, by a living, breathing collector. It is, first and foremost, collectors that Fine Art Connoisseur aims to serve and inspire, and for that reason we have been running lengthy Hidden Collection articles ever since this magazine was founded.

In addition, since 2015 we have highlighted America’s leading collectors of contemporary realist art in a shorter format — two pages dedicated to an individual collector or a couple. So far, this unique initiative has covered 82 separate

collections, and now we are busy planning our next crop, to appear in the March/April 2023 issue of Fine Art Connoisseur.

There are great collections — many still being formed — in every region of this country, and no one person could possibly know all of them. Though our research is well underway and we already have some terrific names in hand, I hereby invite you to send me suggestions or nominations for other collectors. Our criteria are simple: they must be U.S. residents (still living) who have collected, or are continuing to collect, superb contemporary realist art created any time after 1980.

Ideas are welcome from everyone: the collectors themselves, their friends, families, dealers, advisers, curators, etc. Please just send me an e-mail (my address appears on page 8) and I will move it forward. Rest assured that our team is discreet; all communications with collectors will be virtual, and we will not turn up unannounced at their homes to take photos! The individuals selected will have an opportunity to fact-check everything, and in fact they themselves will provide the photos to be illustrated. That said, it ’s our editorial team’s decision who goes in, and who doesn’t.

In every field of human endeavor, role models are essential. Art collecting is no different, and we fully expect to be inspired by what our next group of connoisseurs have accomplished. Thank you for giving this request some thought; we look forward to sharing our findings with you next March.

11.20 - 12.10

MODEL J BY BRANDON SOLOFF [RA 2021]

HORSE FELL WITH RIDER TO THE BOTTOM OF THE CLIFF BY NEWELL

CONVERS WYETH (18821945) [NRA 19081945]

THE JESTER BY WILLIAM MERRITT CHASE (18491916) [RA 18771916]

COME ON OVER DO THE TWIST BY MARSHALL JONES [RA 2007]

ONE OF UNCLE SAM’S ASSETS BY NORMAN PERCEVEL ROCKWELL (18941978) [NRA19211978]

Henri Matisse’s scene of a window open to colorful boats bobbing in a Mediterranean harbor opened a window, of sorts, for Suzanne Tucker. The San Francisco–based Tucker, one of America’s leading and most prolific interior designers, recalls the first time she saw the work known as Open Window, Collioure, as an undergraduate at the University of Oregon. She evokes the classic setting for an art history class, with a slide projector clicking away and flashing images on a big screen in a dimmed room, dust motes dancing in the vector of light. “I was taking notes in the dark, and when this image appeared, I was gobsmacked by Matisse’s use of color.”

While she doesn’t exactly cite the painting as the impetus for changing her major to interior architecture and transferring to UCLA, it does seem as if this scene mirrors much of what Tucker does as an interior designer: her reputation has been earned in part through an exuberant embrace of color, texture, and pattern. “I also remember being struck by the coffee klatch of artists working at that time in the early 1900s,” she continues. “They were all so ingrained with what each other was doing — painting together, showing together, just being jealous of each other. That was such an interesting time

because the whole world of art was changing so quickly. A work like this, revered now, was criticized fiercely then.”

Often cited as an iconic example of fauvism, this particular Matisse, is, indeed, characterized by applications of that movement’s unmixed colors — expanses of the purest shade — and a variety of brushstrokes, some appearing almost haphazard. But Tucker, who works daily choosing color schemes for clients, discerned something else, years later, upon first seeing this painting in person at Washington’s National Gallery of Art, where it resides.

She possesses an uncanny ability to read colors and lighting effects, as if they were words or musical notes. “I love Matisse’s play with the color wheel — his juxtaposition of opposing hues of the wheel.” She points, for instance, to the fuchsia pink wall on the right side and then to the jade green wall opposite. “Those two hues are on opposite sides of the color wheel,” Tucker emphasizes, adding that throughout the work,

color opposites appear on opposite sides of the canvas.

“I first saw Open Window, Collioure in person probably 30 years ago, and then again about a decade ago,” Tucker recalls. “I am still mesmerized by the layers and the textures, how light was captured, and how light plays off the painting. I’m very layered and textured in my own design work, so looking at an artist’s way of treating such variables always fascinates me.”

Tucker’s newest monograph, Extraordinary Interiors (Rizzoli), her third such book, reveals her penchant for creating elegant interiors, many accented with namebrand artworks. While she admits to helping her (typically wealthy and enlightened) clients choose art, and is honored when asked to do so, she prefers to collaborate rather than dictate. “When clients ask me to ‘do’ the art for them, my quick answer is, ‘Sure, but I would prefer you be involved, too.’ Art is so subjective, obviously, and while I recognize that what might not resonate with me does for the client, I am able to respect their choices and understand the purpose the art holds for them. But I really do stress the need and desire to work together on choosing art.”

Many of Tucker’s commissions involve homes with views. “We live in our houses, we live in our apartments, but we don’t live in our views.” Tucker always takes into account those exterior elements as influences for what goes inside the rooms. “You look through Matisse’s window to see the boats in the harbor and the vista beyond, and you realize that we live with our views.” Though his colors are not realistic, she thinks of Matisse’s painting as “a brave use of color which makes for a delightful, happy work.” She says, “Certain favorite artworks are like visiting old friends. You get familiar with each other. You realize you like each other.”

F ounded in 1928, The American Artists Professional League is dedicated to the advancement of traditional realism in American fine art, through the promotion of high standards of beauty, integrity and craftsmanship in painting, sculpture and the graphic arts.

San

415.387.9754 | www.landseaandskygallery.com

ROBERT STEINER

Francisco, CA

Glacier, 16 x 24 in., acrylic on aluminum Point Lobos, 16 x 24 in., acrylic on canvas

Represented by Land, Sea and Sky Gallery, San Francisco, CA

ROBERT STEINER

Francisco, CA

Glacier, 16 x 24 in., acrylic on aluminum Point Lobos, 16 x 24 in., acrylic on canvas

Represented by Land, Sea and Sky Gallery, San Francisco, CA

LAUREN ROSENBLUM

Marlboro, NJ

Cherished, 48 x 24 in., oil on wooden panel laurensart@yahoo.com | 917.708.0817

www.laurenrosenblum.com

ANNIE STRACK, ISMP, IPAP

Kennett Square, PA Fishing Buddies, 12 x 16 in., watercolor on paper info@anniestrackart.com

www.anniestrackart.com

Visit website for gallery representation

LIN YANG

Brooklyn, NY

Michael D. Green, 24 x 18 in., oil on linen

Self Portrait, 24 x 24 in., oil on linen www.linyangstudio.com

AGHASSI

Glendale, CA

Remorse, 10 1/2 x 19 x 14 1/2 in., bronze info@aghassi.art | 747.272.4796 www.aghassi.art Gallery inquiries welcome

LEE ALBAN

Havre de Grace, MD

Two Cookie Buy In, 18 x 24 in., oil on panel leealban@comcast.net | www.leealban.com

Visit website for gallery representation

AKI KANO

Katonah, NY

Maki, 12 x 9 in., watercolor aki@akikano.com | www.akikano.com

Gallery inquiries welcome

HENRY BOSAK

Gilbert, AZ

Coffee with Close Friends, 11 x 14 in., acrylic on canvas henrybosakdesign@gmail.com | 602.677.0094 | henrybosak.com

Represented by 9 The Gallery, Phoenix, AZ

CATHERINE D. HAFER

Westport, MA

Framed by Forgiveness, 11 x 14 in., charcoal on mounted watercolor paper catherine@haferstudios.com | 774.320.5010 | www.haferstudios.com

Gallery inquiries welcome

PAMELA JENNINGS

Brooklyn, NY

Henry, 23 x 15 in., oil pjenn41694@aol.com | www.pamjenningsart.com

Crystal River, FL

Cougar Rising, 48 x 10 x 20 1/2 in., cast bronze (lost wax) bevdavisart@gmail.com | 914.433.8900 | www.beverlycrymesdavis.com

Gallery inquiries welcome

PATSY LINDAMOOD

Huntsville, TX

Alleyway, 36 x 24 in., graphite on cradled Ampersand Claybord

lindamood@lindamoodart.com | 352.339.2353 | www.lindamoodart.com

BEVERLY CRYMES DAVIS

BEVERLY CRYMES DAVIS

LARRY A. GERBER

Bellingham, WA

End of the Day, 44 x 34 in., acrylic on canvas gerberart@aol.com | 561.602.0432

www.gerberfinearts.com

JEAN LIGHTMAN

Concord, MA

Emergence, 28 x 36 in., oil on linen jeanlightman@gmail.com | 978.502.4418

www.jeanlightman.com

MITCH CASTER

Denver, CO

Egret’s Water Dance, 20 x 20 in., oil on canvas info@mitchcasterfineart.com | 720.333.1959

www.mitchcasterfineart.com

Represented by Heritage Fine Arts, Taos, NM; Spirits in the Wind Gallery, Golden, CO; Marta Stafford Fine Art, Marble Falls, TX

DIANE R KELTNER

Santee, CA

The Bribe, 19 x 10 x 8 in., bronze drkeltner1@gmail.com | 619.318.9000 | www.dianekeltnersculpture.com

Represented by White Sage Gallery, El Cajon, CA

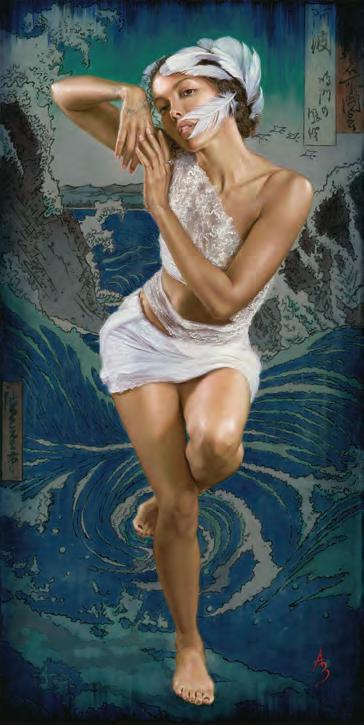

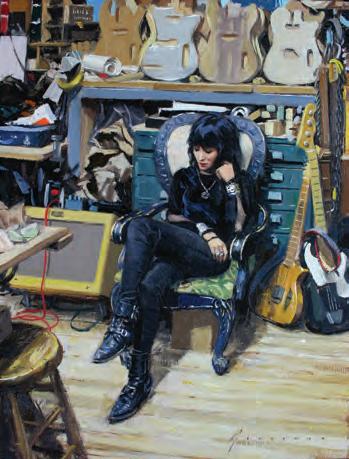

Everyone has one, so everyone is interested, to a lesser or greater degree. I’m referring to the human body, surely the most important touchstone in the history of art. Artists have been depicting the figure for millennia, sometimes in exacting detail and sometimes vaguely, but always with the understanding that every viewer has a direct connection with the subject — and also a way of assessing the rendition’s accuracy. The ongoing renaissance of realism means that figure drawing and painting have not looked this good in North America for more than half a century. For this issue’s Figurative Showcase, we have really mixed it up stylistically, and we hope you will enjoy this diverse array of approaches.

Nashville, TN

A Moment’s Breath, 16 x 16 in, oil on panel jess@jessica-lewis.com www.jessica-lewis.com

Gallery inquiries welcome

Tustin, CA

Enchanting, 9 x 12 in, oil on panel bakerli63@gmail.com www.echofineart.com

@echofineart

MARC ANDERSON (b. 1987) has called the Midwest home since he was a child, having been born and raised in the Rockwellian town of Wild Rose, Wisconsin. The young artist studied illustration at the University of Wisconsin-Stout and then went to work as a freelancer for several clients and publications. Eventually he decided, however, that fine art was more his speed and spent the next several years teaching himself how to paint through a lot of reading, workshops, and practice.

When the artist discovered plein air painting, he found his true passion. Painting outdoors was a far cry from the commercial illustration life and a welcome reprieve from endless hours in the studio. Right in his native state of Wisconsin, Anderson finds all the inspiration he needs, whether he’s painting industrial scenes, local lakes, or sprawling mountain vistas. As he has advanced in his perception and interpretation of his surroundings, the artist has found himself focusing on more conceptual elements. “I’ve been very interested in how light affects color lately,” Anderson shares. “Every scene has unique properties and infinite subtleties that I take great pleasure in trying to capture.”

Take, for instance, Giants of Little America, illustrated here. The foggy sky casting a misty pall on the structures below certainly took

a lot of attention to subtle value and color transitions, as well as compositional accuracy to convey the street-level, wide-angle view. This painting advertises a signature Anderson motif, in that it is about light and atmosphere but also a statement about a sense of place. “Giants of Little America is all about scale and atmosphere,” the artist says. “These feed mills are indicative of small, Midwestern towns, and the juxtaposition of these massive structures and rural communities has always piqued my interest.”

Today Anderson resides in Wauwatosa, Wisconsin, where he runs the M. Anderson Studio as a showroom, studio, and instructional space for workshops. His next solo show is set to open at Charleston’s LePrince Fine Art on December 2.

ANDERSON is represented by Bell Street Gallery (La Pointe, Wisconsin), Edgewood Orchard Galleries (Fish Creek, Wisconsin), LePrince Fine Art (Charleston and Naples, Florida), Lily Pad | West (Milwaukee), and Wantoot Gallery (Mineral Point, Wisconsin).

There is a lot of superb art being made these days. This column by Allison Malafronte shines light on five gifted individuals.MARC ANDERSON (b. 1987), Giants of Little America , 2022, oil on board, 24 x 48 in., Lily Pad | West, Milwaukee

JULIANNE JONKER (b. 1957) was primed from a young age to become the innovative painter, sculptor, and photographer she is today, as she grew up in a family of jazz musicians and creatives who encouraged experimentation, improvisation, and sensitive interpretation. She pursued both classical and contemporary training — first at the Minnesota River School of Fine Art and then with several professional artists in the U.S. and Europe — and today she combines many different disciplines and styles with her own creativity to best honor the subject she is capturing.

“My intention for my art is to serve as a conduit, a visual language for our ability to see and be seen,” the Minnesotabased artist says. “I hope to impart to the work the same beauty I catch a glimpse of when I view a scene or an individual.”

Currently, Jonker is making her works with encaustic, cold wax, and oil paints. This combination of materials allows her to achieve a sculptural quality, creating depth and texture while providing a soft matte patina. “Combining classical and contemporary styles, I use these materials to capture the nuances of each subject’s likeness,” she says. “Working in a rhythm layer by layer, wax and oil combined, I build then excavate, create then destroy, using an array of tools to evoke the history and depth that defines the texture of wax paintings.”

Jonker’s current series, Gods and Goddesses, began during the pandemic, when the artist was deep in introspection considering how to bridge the disconnect and invisibility people experienced during that prolonged period of isolation. Within that collection is her reinterpretation of Bouguereau’s masterpiece Cupid and Psyche (1889), seen through a new lens of inclusion. “The original painting had two little pink cherubs, probably taken from French models since Bouguereau was French,” the artist explains. “My granddaughters and other little people of color rarely see themselves depicted as cherubs, princesses, heroes, or in this case a butterfly/ moth. It’s so important for all children to see their own reflection in the real world around them, as well as in art and media.”

Jonker continues, “I created the little moth/cherub out of my imagination. She represents many ethnicities of brown-skinned little girls. The moth’s symbolist meaning is resurrection and transformation. A moth represents tremendous change, but it also seeks the light. Thus, the spiritual meaning is to trust the changes that are happening, and that freedom and liberation are right around the corner.”

This November Jonker will open a solo exhibition showcasing recent paintings, drawings, etchings, and sculpture, as well as

The diverse compositions, colors, and activities of urban street life and the human condition have held the attention of Florida painter DANNY GLASS (b. 1991) for well over 10 years. His portfolio of large-scale multi-figure paintings, individual portraits conveying psychological depth, and drawings in charcoal, graphite, and penand-ink tell of his desire to understand and make sense of the world through the work of his hand.

“Each of my paintings begins with my perception of contemporary society and my experience of truths revealed by that perception,” Glass says. “I invite viewers to empathize with my desire to express today’s truths and encourage viewers to recognize and explore their own truths and emotions as they view my work. I deeply believe that expressive, figurative art can clearly and emphatically communicate with viewers emotionally and intellectually.”

In Crossing, illustrated here, Glass tells a symbolic story through the eyes of someone who is confined to a chair at a busy city intersection. Her countenance is content and watchful, while the expressions of the others show telltale signs of anxiously being on the move to the next moment of their scheduled days. Color plays a significant role here, although only the artist himself likely knows its true symbolism. All the men are depicted in bright blue while the women,

including the woman watching, are in diluted shades of red. Glass asks the viewer to find and ruminate on just these kinds of subtle clues in his visual narratives.

Relatively new to professional painting, in 2015 Glass completed the dual degree program offered by Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), where he majored in art history and painting. After working as a research intern at the RISD Museum and participating in residency programs, he moved to New York City and earned a Master’s degree in art business from Sotheby’s Institute of Art while maintaining a consistent studio practice.

Today Glass is more committed than ever to using his skills to create images with care and intention that require the viewer to pause and reflect. “In a time when countless images flash before our eyes only to be quickly forgotten, we risk losing touch with the important intuitions and feelings we each have that guide our understanding of the world,” the artist observes. “The choice to commit to images is thus daunting, but for me it is more important than ever.”

ANGIE REDMOND (b. 1987) has been giving a voice to black experience and cultural individuality in America since long before Black Lives Matter rose to prominence. Her figure paintings and portraits have always celebrated beauty in all forms and championed the strength of selfidentity, while calling out injustices and misconceptions with intelligence and positivity.

“I use my art as a means to promote social change, encouragement in oneself, and resilience,” Redmond says. “I use the subject of social justice to insist on change in stereotypes of cultures through the concept of emotions, particularly with the negative way the black body is often viewed and treated in society. I use the psychology of color to emphasize the complexities of human emotions and behaviors.”

Redmond is based in Chicago, and prior to living in the Windy City she earned her B.A. in studio art and oil painting from Michigan’s Albion College, an M.F.A. in painting from Northern Illinois University, and an M.S. in digital art from Knowledge Systems Institute in Illinois. Assimilating the art approaches she encountered during her education, Redmond now uses heavy textural applications of oil paint and bright color to bring to life unseen aspects of her subjects. In Can’t Hide, Won’t Hide My Black – It Starts Here, for instance, the artist’s statement is clear: “This painting is about unapologetically loving yourself and where you came from and not living with the identities placed on you by others.”

Redmond often works in series to convey a cohesive message she feels strongly about, and she is currently developing a body of work titled Who Do You See?, which holds a mirror up to long-held

societal perceptions and judgments. “In a society often consumed with negativity based on different political views, racial identities, or financial statuses, my paintings will continue to emphasize the need for peace,” Redmond says. “My work is focused on people and the beauty in just being, released of the identities placed on them by others. It is not limited to the voice of one culture, but is speaking to all within our community, our society, our human race while we respect our differences and honor our similarities.”

REDMOND is self-represented.

VARVÀRA FERN (b. 1999) is a sculptor who grew up in Moscow. She studied classical figuration at the Moscow Academic Art Institute and then bravely embarked on a new life in America when she relocated to study at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA). Today she continues to live and work in Philadelphia, where she maintains a studio and is completing her M.F.A. at PAFA.

Fern has been a world traveler since the age of 13, and those voyages have greatly shaped her life and art. Her work today is inspired by the idea of movement and travel, in particular roadways and railways, as a means of shifting one’s life and perspective in a new direction. “Traveling is not only a process of going from one place to another, but also an emotional journey,” the artist says. “A person can always find something new in a journey, maybe even happiness. In my work I show people beginning their travel from trauma and unhappiness to finding themselves and reaching harmony.”

The artist’s most recent series, Travel, fully expresses these sentiments. In Travelers, shown here, three figures make their way uphill along a winding railroad track, with luggage and hopes for a new horizon in tow. “This work was inspired by my own travel experience and my love of road landscapes,” Fern says. “It’s also a reference to trainhopping, which I feel is one of the most beautiful, albeit dangerous, ways to travel. It

requires absolute trust and spiritual freedom, as train-hoppers never know exactly where a train is going to bring them. Sometimes a person has to be at a certain level of risk or even despair to make this kind of journey. At the same time, travel always helps one find something new, and maybe this will be harmony and happiness.”

Aesthetically, the artist also finds railroads fascinating because of their mesmerizing, sculptural shapes. To create her interpretations of these structures, Fern opts for working in oil-based clay, a medium that she has used since childhood and therefore is second nature to her. “This material is like a language that I can speak fluently,” Fern explains, “so it allows me to give full form to all of my ideas and imagination.”

DRESSED TO IMPRESS

Depicting the human figure convincingly is a challenge that confronts many realist artists on a regular basis. After all, the body is at the center of our very being, and we can all see when a hand doesn’t look “right” or a head seems out of proportion to the body. Artists who do it well deserve our admiration, and even more so when they complement the figure with a costume — a garment other than the usual “street clothes,” that is in some way performative or staged, that helps a “mere” person transform into someone else.

The artist’s challenge here is not so much selection of the costume — for example, we all expect a clown to wear a red nose — but to ensure that the essential humanity of the person is not drowned out by that garment. In the fashion world, they sometimes say, “That outfit is wearing you,” and they don’t mean it as a compliment.

In this portfolio, then, we present an array of recent artworks that deftly balance all of these competing factors. Diverse as they are, all reveal how clothing helps us to discern a person’s identity more clearly, to better appreciate both their uniqueness and their fundamental connection to the rest of humankind.

(CLOCKWISE FROM ABOVE) CHANTEL LYNN BARBER

(b. 1970), Come and Find Me , 2021, acrylic on panel, 20 x 16 in., private collection

ANDREAS CLAUSSEN

(b. 1988), Ready for the Flood, 2022, oil on canvas, 63 x 47 in., private collection

TERRY STRICKLAND

(b. 1960), Phoenix Rising , 2022, oil on panel, 16 x 12 in., 33 Contemporary Gallery (Chicago)

ALEXANDRA

MANUKYAN (b. 1963), The Wrinkled Sea Beneath Her Crawls , 2022, oil on linen, 36 x 18 in., Abend Gallery (Denver)

(CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT) DARYA DOLGAREVA (b. 1991), Tempting the Virtuous , 2022, oil on wood, 25 4/5 19 3/4 in., available through the artist KIMBERLY DOW (b. 1968), Charlie Steals the Show, 2020, oil on panel, 29 x 14 in., 33 Contemporary Gallery (Chicago) NANETTE FLUHR (b. 1965), Autumn , 2022, oil on Masonite, 21 4/5 x 18 in., 33 Contemporary Gallery (Chicago)

ROSE FRANTZEN (b. 1965), Attending , 2022, oil on linen, 72 x 48 in., available through the artist

(CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT) ADRIAN AGUIRRE (b. 1980), Control de Tráfico , 2020, oil on canvas, 42 x 32 in., private collection VINCENT N. FIGLIOLA (b. 1936), Gregory, 2022, oil on canvas, 26 x 28 in., available through the artist VICTOR GADINO (b. 1949), Pandora , 2021, oil on canvas, 30 x 24 in., available through the artist BARBARA HACK (b. 1957), It’s a Man’s World , 2020, oil on canvas, 22 x 21 in., available through the artist

(CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT) LORENA LEPORI (b. 1974), The Barbie Doll , 2021, oil on canvas, 78 3/4 x 47 1/4 in., 33 Contemporary Gallery (Chicago) TRACI WRIGHT MARTIN (b. 1980), Huntress , 2022, charcoal and pan pastel on paper, 18 x 18 in., 33 Contemporary Gallery (Chicago) DOUG WEBB (b. 1946), Daughter of Woman , 2022, acrylic on linen, 20 x 16 in., 33 Contemporary Gallery (Chicago) LINDA H. POST (b. 1950), Soliloquy, 2021, oil on panel, 16 x 16 in., available through the artist

(CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT) DEBBIE KORBEL (b. 1964), Wings of Thunder, 2017, mixed media sculpture (including steel, copper, aluminum, and resin), 8 ft. x 8 ft. x 24 in., Ernie Wolfe Gallery (Los Angeles) VAL SANDELL (b. 1952), Canary Islander Descendant, 2020, oil on linen, 32 x 20 in., available through the artist WILLIAM SCHNEIDER (b. 1945), Robber Baron , 2018, pastel on sanded support, 20 x 16 in., collection of the artist MARK R. PUGH (b. 1979), November, 2021, oil and ink on linen, 20 x 30 in., private collection

(CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT) YVONNE MELCHERS (b. 1948), Siena Palio XVIII (Tartuca/ Turtle) , 2021, oil on linen, 15 3/4 x 19 3/4 in., available through the artist JENNIFER STOTTLE TAYLOR (b. 1967), Ted Clayton , 2021, oil on linen, 30 x 10 in., private collection ZHIWEI TU (b. 1951), A Hope , 2022, oil on canvas, 20 x 16 in., Reinert Fine Art & Sculpture Garden Gallery (Charleston)

TODAY’S MASTERS

NICK BENSON STONE CARVING & BEYOND

As any visitor to Newport, Rhode Island, knows, Thames Street is where the action is. Hugging the waterfront, chock-a-block with shops, restaurants, and bars, it’s the money-making heart of town, a place plenty of residents avoid if they aren’t running a business there. At its end, in a neighborhood of 18th- and early 19th-century houses called The Point, retail and hospitality give way to sidewalks that may not see more than a few pedestrians all day.

There is one notable business here, though: the John Stevens Shop. A stonecarving enterprise founded in 1705, it was operated by six generations of the Stevens family until Newport native John Howard Benson (1901–1956) bought it in 1927. His son, John Everett Benson (b. 1939), started working there at age 15, departing only long enough to earn a degree from the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence. In 1964, he was commissioned to design and carve the inscriptions for the John F. Kennedy Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery. His own son, Nicholas Waite Benson (b. 1964), took up the mallet and chisel at 15; after studying drawing and design at the State University of New York at Purchase (followed by a year at Basel’s Schule für Gestaltung), he returned to the workshop, eventually taking it over in 1993.

In its early years, most work at the John Stevens Shop was devoted to tombstones. But under the stewardship of successive Bensons, institutional and civic projects have grown into a key part of the business. John Howard did work for the Groton School, Phillips Exeter Academy, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. John Everett counted the National Gallery of Art and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange among his clients. He also made his mark with

large-scale commemorative commissions, including Washington’s Vietnam Veterans and Franklin Delano Roosevelt memorials.

Nicholas (“Nick”) Benson has sustained that tradition, designing and executing the lettering for, among others, the Dwight D. Eisenhower and Martin Luther King, Jr. memorials in the nation’s capital and the FDR memorial in New York City. In 2010, his excellence in this arena won international attention when he was awarded a MacArthur Foundation (“Genius”) fellowship.

Nick lives and breathes tradition, not only that of his family, but of his craft. He traces the essence of the Stevens style to inscriptions found at the base of Trajan’s Column in Rome, a lettering his grandfather embraced and altered, experimenting with the weight and proportion of the characters to devise a singularly satisfying letter form. “My grandfather had this crazy strong artistic bent that shone through in everything he did,” Nick says. “Going to a cemetery today, I will spot a stone he did and what I immediately see is the aesthetic value. I think, that’s a beautiful thing. Only then do I consider what’s written there.”

As a teen, Nick Benson couldn’t wait to get out of Newport. He had some vague idea of becoming an artist (his uncle was the noted photographer Richard Benson and his brother, Christopher, is a painter), but after studying with type designers André Gürtler and Christian Mengelt in Basel, he returned to his father’s shop with a deeper, more informed appreciation of the aesthetic and communicative power of hand-carved lettering.

As soundly beautiful as the family’s work is, Nick does not claim for it the mantle of art. “My grandfather’s friends spoke of him as a great craftsman. Though he also made art, it was the craft, and his attention to process, that most people recognized. They saw his craft for what it was. What we are doing is conveying the client’s message. We design it very carefully and make it beautiful, but when John Q. Public sees it, what he sees first is the information the client wants conveyed. That is craft. I am being hired for that purpose. The aesthetic is secondary.”

Even though people still marvel at how the Bensons make such sweeping strokes with rough tools, or at how their letters (which can evoke anything from gravitas to whimsy) help convey the meaning of the words they spell, public appreciation of hand-carved stone inscription as craft is fading. “All this picking away with mallets and chisels isn’t really understood anymore, because there isn’t any context for understanding it,” Nick asserts. “Years and years ago, guys were great carpenters, they were blacksmithing, women were making beautiful quilts. In any town, people knew how to make stuff. People aren’t making by hand anymore in a way that the public is used to

seeing. And over the past 20 years, the entire digital realm has had a dramatic effect on our perception of aesthetics and of the physical world.”

SOMETHING DIFFERENT

Though still devoted to craft and to putting his “soul” into it, Nick has followed in the footsteps of his father (who retired from the shop to concentrate on his own figurative sculpture) by making time to exercise a purely creative muscle. The same intellectual curiosity that has led Nick toward deep understanding — of how the physical expression of language in stone is immediate, complex, and profound — also propels his work as an artist.

Nick’s artistic journey began in 2014, when his computer spewed out a mess of confusing, unreadable text. Having spent his life working with words and symbols, he was immediately drawn to this letterdriven image. “I recognized it as a giant piece of computer code, basically the lingua franca of today. So I thought, okay, this is symbolic of the evolution in human communication. I am going to take this stuff and make calligraphic interpretations of it. I am going to carve it in stone to highlight this radical shift from what was to what is. And I will ask, ‘Where is this all going? And what does it mean?’”

The building block of Nick’s endeavor is Base64, a computer code used for transmitting images over the Internet. It comprises the letters of the alphabet (upper and lower case), numerals 0 to 9, and the symbols + and /, with = at the tail end of a string. Cut into slate and then gilded, the seemingly random panoply of characters in one of his early pieces reads initially as a page from a calligraphy primer. But as our eye adjusts, taking in the stems and crossbars of the letters,

the serifs’ extravagant sweep and the almost bubble-like profile of the numbers three and five, the whole begins to assume, not intelligibility, but the intimation of a message.

More recently, Benson has employed code to ponder portraiture, running a photograph of himself through the Base64 algorithm, then interpreting those coded characters on paper with a broad-edge brush before incising them on stone and carving into it. (This is the same ageold technique used in his commercial work.) Once completed, the final self-portrait will comprise 22 panels that can be arranged in various ways — as a grid, or a line around a room’s perimeter — as long as they are in sequence. Taken together, the photograph, code, and carving form a triptych, one in which Benson tussles with the complexity of visual language to reclaim his likeness. “The machine, the computer, takes a face, takes humanity and turns it into a code. I take back the humanity by making a calligraphic version of that code, which says ‘This is me.’”

At the moment, Benson — who admits to getting “all hung up on extreme perspectives in science” — is working on a cosmically driven piece. It has been inspired, in part, by Particle Fever (a documentary that chronicles experiments at the Large Hadron Collider near Geneva) and by images from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope capturing the phenomenon known as gravitational lensing, in which the gravity of massive galaxy clusters containing dark matter distorts the light of even more distant galaxies.

Benson explains, “I get very interested in the subatomic and the cosmic and this incredible span between the two; in the fact that humanity — we have tremendously huge egos — is so wrapped up in this skin of atmosphere and the little rock we inhabit in a vast void. So I am going to make panels depicting the gravitational lensing effect; in the middle I will carve a piece of mathematics proposed by theoretical physicist Peter Higgs that describes the entire universe according to particle physics. This is meant to represent how our incredible human knowledge amounts to very little in light of the universe. I am going to use a broad range of metals — palladium, gold leaf, rose gold — to describe the universe, and I will oil the slate to get it even darker.”

Derived from a less complex source, an earlier piece encapsulates the tension inherent in Nick’s endeavor — the collision of an ancient craft with contemporary modes of communication within the rarefied universe that is the art world. Pointing to a luxuriously inscribed slice of slate hanging in his shop, he remarks, “It’s not easy to read, but it’s a quote from painter Anthony Terenzio, when he was being interviewed by some art muckety-mucks in New York City in the ’70s. They wanted to talk about

conceptual art and he replied, ‘Of course, no so-called style can continue forever, because then human consciousness would have to remain static. But on the other hand, you can’t pretend nothing ever happened.’”

MAKING CONNECTIONS

Nick Benson’s art is driven by a desire to address the complexity of communication and the permutations of expression, and to understand how his skills might make sense in a world defined by instantaneity and digital hegemony. Neither caught in the past nor fully committed to the present, he seeks a middle ground, a space in which multiple sensibilities and practices coexist, a dialogue in which each voice contributes to mutual understanding.

“Years ago, when I went to the National Gallery to add benefactors’ names to the walls, there were people there at their easels, copying the masters. Everybody flocked around them. They would say things to each other like, ‘Why are you adding this green layer? That doesn’t look like the sky. ‘Well, that’s the underpainting.’ So people would get engaged in the process. I want to do that in a museum — to carve on site and engage with the public. That’s the demystification art needs right now.”

Until then, Nick continues his novel explorations on that quiet block in Newport. “Art,” he explains, “is a huge part of my life now, and I think about it all the time. Thankfully, I am able to make it in a vacuum of creative freedom. I can head down this path of mystery to see where it leads. It can lead anywhere. It can lead to immediate failure. But you have to take a risk in order to make something that means anything. It’s a gamble, but one worth taking.”

Information: johnstevensshop.com, nicholaswbenson.com

NORDIC REFLECTIONS THE MARINE PAINTINGS OF EMIL CARLSEN

Lyricism, quietude, subtlety — these are the defining qualities of the landscape paintings of the Danish American artist (Søren) Emil Carlsen (1848–1932). In his lifetime, Carlsen was far better known for still life subjects, and the misconception that this was his primary genre has prevailed.1 In fact, landscapes represent a significant aspect of his production, including exceptional marine scenes painted throughout his career.

Warranting particular reappraisal are Carlsen’s compositions picturing open seas, coasts, and falls, which earned critical acclaim and bound him artistically to his Nordic seafaring heritage.2 Indeed, his lifelong connections to Denmark supplied an essential foundation for his art and especially informed his marine paintings.

Carlsen was born in Copenhagen and studied architecture at the Royal Danish Academy for four years. He then turned to art, and although the circumstances prompting this shift are unknown, art was

(RIGHT) Summer Cloud s, c. 1910, oil on canvas, 39 1/8 x 44 15/16 in., Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Joseph E. Temple Fund, 1913.5 (BELOW) Open Sea , 1909, oil on canvas, 48 x 58 in., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, gift of George A. Hearn, 1910, 10.64.1

part of his heritage, as his mother and brother were painters.3 Carlsen studied under the marine painter Christian Vigilius Blache (1838–1920) from 1866 to 1869, but in 1872 he immigrated to the United States and settled in Chicago, where he trained with another Danish-born marine painter, Lauritz Holst (1848–1934). He also studied in Paris in 1875, and returned there from 1884 until 1886.

Although Carlsen developed a unique style, the influence of the two older Danes and the traditions of his homeland are evident in the emphasis he gave to the natural world (especially open space, water, and sky), in his minimal and harmonious compositions, and in their entrancing light and atmosphere. All are features found in much Scandinavian art.4

EARLY MARINE SCENES

In 1876, the earliest published account of Carlsen’s marine paintings appeared in the Boston Evening Transcript (he moved to Boston that year after living in Chicago for four years): “Carlsen … has two or three pictures nearly completed which will soon be placed on exhibition in one of our galleries. They are marine and shore views and are remarkably effective.”5

His most noteworthy early water composition is a Massachusetts scene with a boat wreck on Nantasket Beach (1876). Created when he was only 28, it is arguably Carlsen’s first mature painting and possesses many of the hallmarks that became essential to his seascapes — the open and spare composition, wide expanse of sky, and horizontal stripe of land. The subtle palette and thin application of pigment are also typical of the technique seen in his early landscapes, but differ markedly from the dark, somber tonalities of his still life paintings.

Duncan Phillips, the critic, philanthropist, and (Carlsen’s later) patron who founded Washington, D.C.’s Phillips Collection, explained how the artist’s interest in landscape developed, noting that his early landscapes were executed in a manner that was “rather thin and tight, but of a fine tonality and sensitively observed. In those days, no one cared for ‘still life’ and he could not sell his canvases. The world might never have known his landscapes and ‘marines’ if the struggle had not become precarious, so that his friends advised him to abandon ‘still life’ for more popular subjects.”6

Carlsen had painted maritime subjects even while in Denmark, as early as 1870. Once in America, he attempted to establish his reputation with still lifes; in fact, he submitted them almost exclusively to major annual shows at the National Academy of Design and Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts through the turn of the century. Yet, he continued painting waterscapes, as noted in 1883 in the Boston Sunday Globe: “It will be a loss to one branch of art if Mr. Carlsen gives up his still lifework [sic], but if he succeeds as well with marine subjects the gain will quite evenly balance the loss.”7

After 1900, Carlsen became increasingly engaged with landscape and marine compositions and began showing fewer still lifes. It is possible that this shift was influenced partly by his friendship with American impressionist J. Alden Weir (1852–1919), which commenced around the same time. The two artists shared a poetic and suggestive approach to painting nature, although with different results.

Beginning in 1907, Carlsen presented his waterscapes more publicly, entering them in major annual exhibitions at the National Academy, Pennsylvania Academy, Corcoran Biennial, Carnegie International, and Art Institute of Chicago. Among those who observed the similarities in how he conceived waterscapes and still lifes was Phillips, who commented that “in many pictures, both of the sea and of the land, both by sunlight and moonlight, he has shown a power to stir our emotions as only great art can do…. Always his canvases seem to have been conceived and composed as still life.”8 Indeed, tranquility is as much a mark of Carlsen’s landscapes, especially his coastal views, as of his still lifes. In general, he maintains the same even-handed and tempered emotional tenor across all genres.

This subdued mood can also be traced to the Danish cultural temperament and the influence of Carlsen’s training, especially by Blache, who painted open coastal views, often with boats, that are defined by delicate light, a modulated tonal range, and restrained technique. Nantasket Beach and a much later scene, Summer Clouds (c. 1910), both resemble

works by his mentor. Summer Clouds trades the shipwreck for fishing vessels grounded on a stretch of beach. This stark, calm beachscape, which uses paler hues and an even more vast expanse of sky, became a crowning achievement for Carlsen in 1913 when it won the Pennsylvania Academy Lippincott Prize for an oil painting by an American artist. These compositions, which both adopt the expansive sky and low horizon format, underscore a key to Carlsen’s methodology — that of repeating thematic variations.

Carlsen embraced his life in America but made frequent visits back to Denmark, including its coastal areas, surely reinforcing the cultural bond with his homeland. The Jutland Peninsula and Kattegat were among his favorite sketching places and inspired copious sea and coastal paintings. He was also drawn to Skagen, where an art colony had taken root; Blache had been among the first painters to visit there in 1869.9

In America, Carlsen sought out comparable settings: the rocky coastline around Ogunquit and York, in southern Maine, is featured in a sizable number of views, often with roiling blue surf and white foam pulsing against russet-colored rock formations. Indeed, that scenic region may have reminded Carlsen of Denmark’s coastal cliffs and stirred his imagination. His aquatic subjects encompass areas farther afield, too, including Charleston, Cape Cod, Niagara Falls, St. Thomas, New Hampshire, and Venice.

Carlsen’s well-received The Surf (1907) depicts the coast near Ogunquit.10 Here the surf hurtles toward and pummels the rocks, something many other artists working in Maine also enjoyed capturing. What is notable about Carlsen’s interpretation is the impact’s hushed quietness, not tumultuousness. Fellow landscapist and art critic Eliot Clark observed that there is a “feeling of radiant gentleness and kindliness [that] pervades [Carlsen’s] work, the true emanation of his own character. Nature is never harsh, austere, or powerful. In his marines, it is the sea in quiet, undulating motion under a blue sky . . . . We have nothing of the power of [Winslow] Homer as seen in his rugged resisting rocks, turbulent water and onrushing waves. Carlsen’s work projects the serenity of nature.”11 This association of tranquility with the artist’s character and cultural heritage was noted by other commentators as well.12

The Surf was widely exhibited, beginning in 1907 at the Corcoran Biennial, then in such cities as Buffalo, Boston, Pittsburgh, and New York.13 When the Ohio industrialist and philanthropist Joseph G. Butler, Jr., finally purchased The Surf in 1923, he was concluding a sixyear struggle to own what he believed was one of the finest American seascapes.14 Carlsen had been extremely reluctant to part with it and had changed his mind about selling it several times, believing it to be one of his most important marine scenes.15

OPEN SEA

Carlsen soon followed in 1909 with another monumental seascape, Open Sea, enhancing his growing reputation for marine painting. This was a subject he would present in various versions over the next 10 years, with the original (now in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art) being the largest at 48 x 58 inches. One critic described it as “a study of the open sea from the coast line” of the Jutland Peninsula, from the northernmost

part of Denmark around Kattegat or Skagerrak.16 Other versions (with the same title) date from 1911, 1914 (two), and 1919, and Carlsen produced many other variations with different titles into his later years.17

The 1909 painting represents an archetypical composition for Carlsen — a near-square devoid of humanity with a low horizon line that separates frothy swells from a cloud-swept sky. He consistently deploys a diffuse and pearly, opalescent light countered by vivid, cobalt-blue seawater. His approach was extolled regularly by critics who perceived in it specifically Nordic traits. In response to a 1909 solo exhibition in New York, one writer said that “it is in the large pictures of the sea that Carlsen lives up to his Danish blood, in the presentation of what may be called his own seas.”18

When the Metropolitan’s version of Open Sea appeared in a 1910 solo exhibition in New York, it prompted one writer to note its “cold blues and the keen cold sunlight of the North.”19 Critic Elisabeth Luther Cary asserted that “Denmark was in [Carlsen’s] blood, in his vision, and in his craftsmanship” and that his “work is eloquent of the special quality of the Danish people, their poise at the middle point between coldness and emotionalism.”20 She also perceived a mystical quality shared by Carlsen and the well-known Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864–1916), while noting the simplicity and sincerity of Carlsen’s landscapes. A static quality, a minimal approach to the subject, and a cool palette link these artists, and, indeed, these are elements that characterize much Scandinavian art.21

In 1910, as Carlsen’s merit as a marine painter became better appreciated, one writer remarked that “Carlsen, good painter as he has always been, has only ‘struck his true gait,’ as it were, the past four years.”22 This observation coincided with his move toward the large-scale landscapes he showed and sold with growing success.

NIAGARA

A separate subject for Carlsen was Niagara Falls, which inspired at least eight compositions picturing different perspectives of that enthralling natural spectacle. The earliest work dates to 1912, when it is believed he first traveled there.23 Many artists have been moved to paint this uniquely American subject, including Rembrandt Peale, Albert Bierstadt, George Inness, Frederic Church, Jasper Cropsey, John Kensett, and John Twachtman.24 Its visual splendor is best conveyed by two Carlsen canvases, Niagara (Norton Museum of Art) and the larger Mist and Rainbow, now in the Owen-Yost Collection. The artist usually submitted his latest works to annual exhibitions right away, yet for some reason, the Niagara scenes were not exhibited publicly until about seven years later.25

Mist and Rainbow is the largest of them (39 x 45 inches) and is noteworthy for its direct, head-on perspective of the falls from below. Its dramatic impact is the result of the view upward as the falls seem to rise out of the spray capped by a rainbow, effecting an impressionistic, nearly abstract, vision of the scene. Few other artists portrayed it from this vantage point, with the exception of Church.26 Carlsen often expressed

his spiritual and religious faith through his art, frequently in suggestive ways; this is particularly evident in Mist and Rainbow, which highlights the transcendent quality of nature at its most sublime. (He also made more overt religious references in a number of seascapes that include spectral figures of Christ.27)

LATER CAREER AND LEGACY

Carlsen reprised his essential seascape compositions late into his career: for example, Moonlight and Sea (c. 1910) and The Heavens are Telling (c. 1918) are redolent of the 1909 masterwork Open Sea. Both focus on the moonlit sky and ethereal reflections on water, evoking a higher spiritual power in their majesty and serenity. In the 1923 Coast of Maine, Carlsen summons up his 1907 success, The Surf. The later effort elevates the horizon line, driving our attention toward the calmer sapphire blue water and the coppery-brown rocks through pure, jewel-like tones and diffuse light. Inaccurately characterized as an impressionist, Carlsen painted views that are both idealized and naturalistic, with his technique and approach becoming increasingly refined over time. His canvases are marked by a radiant light, lustrous surface, and a particular

opalescence he created by scraping and building up thin layers of pigment, along with a liberal use of white.28 His best paintings glow with a diffuse ambient light he achieved with a matte impasto facture, supple brushwork, and velvety hues.

After his death in 1932, Carlsen was lauded as a “great painter” by Elisabeth Luther Cary, and his prestige seemed assured.29 Yet the defining traits of his art — refinement, understatement, and poetic lyricism, as well as a style that defies classification — may have partially contributed to the decline in popularity it underwent from the 1940s. In recent years, there has been renewed interest in Carlsen, prompting both new scholarship and commercial attention.30

Today, Carlsen’s still lifes, landscapes, and seascapes come up regularly — in nearly equal numbers — at auction and through dealers such as Debra Force Fine Art, Thomas Colville Fine Art, Cooley Gallery, and Taylor Graham. His market is relatively stable, although somewhat undervalued considering how highly regarded his work was in his day. Lesser works can be found in the four-figure range, with more

important examples going for five or six figures depending on size, quality, and subject. (American scenes fare more successfully than foreign ones.) Carlsen’s record at auction is $325,000, paid for a still life in 2018.

In the context of the art market’s current vigor, these prices are modest, so it is the hope that the exceptional beauty and exquisite technique of Carlsen’s art will ultimately gain the appreciation it so richly deserves.

VALERIE ANN LEEDS is an independent scholar and curator specializing in late 19th- and early 20th-century American art. She has organized more than 50 exhibitions, and published and lectured widely on various topics in the field.

Endnotes

1 See Duncan Phillips, “Emil Carlsen,” International Studio 61 (June 1917): cv–cx. Also see Arthur Edwin Bye, Pots and Pans, or Studies in Still-Life Painting (Princeton University Press, 1921), who called Carlsen “unquestionably the most accomplished master of still-life painting in America today.” For a more modern viewpoint see, for example, Richard Boyle, American Impressionism (New York Graphic Society, 1974), 135–36, who states that “Carlsen’s special concern was still life” and does not mention his landscapes. Also see William Eric Indursky, “Emil Carlsen: An Overview of the Artist’s Life and Work,” in Emil Carlsen’s Quiet Harmonies, exh. cat. (Yellowstone Art Museum, 2018), 21, in which he states that “of the 887 catalogued examples of his work, 447 are landscapes, 209 are waterscapes and only 313 are still life, with the remaining split between portrait and genre.”

2 Ca rlsen received a number of awards for landscapes, outnumbering those received for still lifes. This is perhaps not surprising as, in the art historical hierarchy, still life was considered a lesser genre than

landscape. For sources on Carlsen’s life and art, there are few letters, no diary, and few primary sources apart from the paintings themselves. The most relevant publications include Kim Lykke Jensen, Søren Emil Carlsen: The Hammershøi of Manhattan (Narayana Press, 2008), a translation of which can be found on the important research website created and managed by William Eric Indursky, emilcarlsen.org. Also see The Art of Emil Carlsen, 1853–1932, exh. cat. (Wortsman Rowe Galleries, 1975); Phillips, “Emil Carlsen,” cv–cx; F. Newlin Price, “Emil Carlsen— Painter, Teacher,” International Studio 75 (July 1922): 300–308; Gertrude Sill, “Emil Carlsen Lyrical Impressionist,” Art and Antiques 3 (March/April 1980): 88–95; John Steele, “The Lyricism of Emil Carlsen,” International Studio 88 (Oct 1927): 53–60; Eliot Clark, “Emil Carlsen,” Scribner’s Magazine 66 (Dec 1919): 767–70. There has been a resurgence of interest

and recent scholarship that includes Ulrich W. Heisinger, Quiet Magic: The Still Life Paintings of Emil Carlsen, exh. cat. (Vance Jordan Fine Art, 1999); William H. Gerdts, William Eric Indursky, and Robyn G. Peterson, Emil Carlsen’s Quiet Harmonies, exh. cat. (Yellowstone Art Museum, 2018); and William Eric Indursky, Emil Carlsen: Conscious Painting (Emil Carlsen Archives, 2017).

3 See Indursky, “Emil Carlsen: Conscious Painting,” based on the essay by Kim Lykke Jensen, emilcarlsen.org/essay.

4 See Clark, “Emil Carlsen,” 767; Steele, “The Lyricism of Emil Carlsen,” 60; and “An Artist of Our Time, Emil Carlsen, 1853–1932,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, undated clipping, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Papers, Archives of American Art.

5 “Art and Artists,” Boston Evening Transcript, May 7, 1876.

6 Phillips, “Emil Carlsen,” cx. Still life was considered less important than landscape in the hierarchy of subject matter.

7 “Art and Artists,” Boston Sunday Globe, October 21, 1883, 10, cols. 6–7.

8 Phillips, “Emil Carlsen,” cvi. Also see Samuel Isham, The History of American Painting (1905; reprint, MacMillan Company, 1936), 450.

9 It has been asserted that Carlsen made frequent trips back to Denmark, including in 1875, 1877, 1890, 1908, 1909, 1910, 1911, 1912, 1913, 1917, 1918, 1919, 1922, and 1925, and possibly other occasions. It is, however, curious that Carlsen was able to travel back to Denmark so often as he was thought to have had little money until success came late in his career. He revisited Skagen and Vejle among other places, and was known to have stayed at Brøndum’s Hotel in Skagen during the 1908, 1909, and 1910 stays at least, sometimes with his family. See emilcarlsen.org.

10 “ Emil Carlsen Made Journey To Maine To Finish Painting,” Washington Times, April 7, 1907. The painting was first shown at the Corcoran Biennial in 1907, no. 280.

11 Clark, “Emil Carlsen,” 769–70.

12 For example, also see Elisabeth Luther Cary, “A Survey of the Art of the Late Emil Carlsen: Quietness and Slow Time,” New York Times, Jan 10, 1932, sec. 8, 11.

13 See emilcarlsen.org/portfolio/emil-carlsen-surf-1907.

14 In 1919, Joseph Green Butler, Jr. (1840–1927) established the first art museum dedicated solely to American art, in Youngstown, Ohio.

15 Robert McIntyre to Joseph G. Butler, Jr., Jan 26, 1923; and Butler to Henry A. Butler, Jan 27, 1923, Butler Institute of American Art archives.

16 “ Exhibition of Works by Emil Carlsen, Childe Hassam, and Frederick Ballard Williams,” Academy Notes (Buffalo Fine Arts Academy, Albright Art Gallery) 5 (April 1910): 21.

17 For the versions, see emilcarlsen.org. The Met painting was exhibited at the Carnegie International in 1910. Other versions were shown at Chicago in 1910 and 1912; Pennsylvania Academy in 1912; Corcoran in 1914, 1919, and 1923; National Academy in 1916 and 1919; 1915 PanamaPacific International Exposition in San Francisco; and at the Carnegie in 1921.

18 “ Emil Carlsen at Bauer-Folsom’s,” Independent 66 (April 29, 1909): 896–97.

19 “Carlsen at Folsom’s,” American Art News 8 (March 5, 1910): 6.

20 Ca ry, “A Survey of the Art of the Late Emil Carlsen,” 11. She added that Hammershøi’s work and this manner of painting was considered part

of a revival “linking . . . subtly nuanced aestheticism to a space, protomodernist classicism.”

21 In his Northern Light: Nordic Art At the Turn of the Century (Yale University Press, 1988, 21, 24), Kirk Varnedoe observed that Scandinavian artists tended to cultivate a sense of nationalism in their work and that “young Scandinavian painters were encouraged both to study the techniques of the Parisians and to isolate and depict the special conditions of light, topography and physiognomy that characterized their Northern homelands.”

22 “Carlsen at Folsom’s,” American Art News 8 (March 5, 1910): 6. His solo show was at Folsom Galleries in New York, a noted venue for American art.

23 This point may have been clarified in Carlsen’s papers, which were inadvertently destroyed. Only one Niagara paintings is dated: Above Niagara (1912, 15 x 18 in., Christie’s, Dec 1986). Other works are Moonlight on Niagara (14 1/2 x 14 1/2 in.) and Niagara Falls from Terrapin Point (25 x 30 in.; formerly George Pratt), both unlocated; and Niagara River and Goat Island (15 x 18 1/4 in.; Scripps College, California). The Scripps painting and Above Niagara do not depict the falls, but the Niagara River.

24 For example, see Jeremy Elwell Adamson, Niagara: Two Centuries of Changing Attitudes, 1697–1901, exh, cat. (Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1985).

25 They appeared at the Pennsylvania Academy in 1919, National Academy in winter 1921, and Chicago in 1924.

26 See Adamson, Niagara, 60, 67. The Norton Museum painting shows the falls from Goat Island.

27 See People-Religious subjects at emilcarlsen.org.

28 See Price, “Emil Carlsen—Painter, Teacher,” 308. As Price observed in 1922: “Gradually he developed a quality of surface that is an outstanding characteristic . . . the surface which he built and painted so carefully only to cut it down and paint again, and scrape and paint to make the canvas fine and still finer.”

29 Ca ry, “A Survey of the Art of the Late Emil Carlsen,” sec. 8, 11.

30 See recent publications listed under References at emilcarlsen.org.

HISTORIC MASTERS

MARGUERITE LOUPPE ON HER OWN

Women artists of talent have too often been overlooked. This is something not yet banished to the past, although, yes, times have changed, and for the better. A gratifying number of women — still not enough — have emerged from undeserved obscurity, some once eclipsed by a more successful husband, lover, or son. A nowfamous example is Suzanne Valadon, whose son was Maurice Utrillo. Marguerite Louppe (1902–1988) is another: her life spanned almost the entire 20th century, a period of enormous transitions of unparalleled rapidity.

Louppe’s husband was Maurice Brianchon (1899–1979), an artist celebrated in his day both in France and abroad. She was his active collaborator on many projects and managed his career. He, in turn, was surprisingly supportive of her as an artist in her own right, unusual in the context of the times and within a traditionally patriarchal society. By all accounts, they had an exceptionally close relationship that seamlessly merged the professional and the personal. (Even Christo and Jeanne-Claude, one of history’s most famous art couples — and from a later, more progressive generation — did not officially become a collective until 1994, three decades after they began to collaborate.)

Louppe was born in Commercy, in northeastern France, to a family of prominent engineers that included her father and an uncle, Albert Louppe, who guided construction of a strategically important bridge near Brest that was later named in his honor. Her parents moved to Paris soon after she was born and settled in the wealthy 16th arrondissement, where she was raised.

Rather than enrolling her in a Catholic school, her parents sent her to the Lycée Molière. This was the first French public school to accept girls; its rigor and high standards, as well as its more diverse

student body, suited Louppe and served her well later. There she studied literature, turning to art after graduation by taking classes for the next six years at several of the private art academies that abounded in Paris: the Julian, Grande Chaumière, Scandinave, and André Lhote.

These academies were quite progressive; both men and women (who were not yet accepted at more established art schools) flocked to them. The Académie Julian was noted for its radicalism and encouragement of independent thinking, which no doubt reinforced Louppe’s experimental inclinations and interest in the new. Among the fledgling artists there with her were Marcel Duchamp, Jean Dubuffet, and Louise Bourgeois. Julian’s older alumni included Pierre Bonnard, André Derain, and Édouard Vuillard. Louppe met Brianchon at a Julian function through the family of a friend; they married in 1934 and the following year their only child, Pierre-Antoine, was born.

Louppe mounted her last show in 1985 and died three years later in Paris, a decade after her husband. For many years their artworks were stored in a warehouse by their son, largely unseen, although now and then he sold some of his father’s paintings. Pierre-Antoine died in 2012, and, since he never married, he bequeathed his parents’ estate to relatives with whom he was close. Their son, David Hirsh, began to make inquiries in consultation with William Corwin, an artist and art historian. Now their estate is represented by Rosenberg & Co., the powerhouse gallery of modern art established in Paris more than a century ago and forced to

relocate to New York during the Nazi occupation. Thanks to its efforts and those of others, Louppe’s oeuvre is enjoying its moment in the sun, the focus of a string of exhibitions and overdue critical attention.

SEPARATE & TOGETHER

Louppe and Brianchon seem to have had an ideal marriage, if any relationship can be completely free from complications. She frequently exhibited where he did, no doubt at his urging, but that would have gotten her only so far without her considerable skills, even if they were not recognized as equal to his. At the time very few women artists were appreciated by critics, institutional power brokers, or the public, even when, like Louppe, they were showing at highly regarded galleries such as Charpentier, Charles Auguste Girard, and René Drouet, alongside artists like Bonnard, Georges Rouault, Georges Braque, and Maurice Denis.

Among the couple’s documented collaborations were three murals for Paris’s Conservatoire National de Musique et d’Art Dramatique, of which later renovations have left no trace. Louppe also made illustrations for a novel by Georges Duhamel, the celebrated critic, Nobel nominee, and member of the Académie Française — another indication that she was respected by others beyond her husband.

Louppe and Brianchon enjoyed a full social life and hosted salons for cultural luminaries — a power couple, we might say. But in 1959, after decades at the center of the Paris art world, they bought a property with a commodious farmhouse and garden in Truffières, a village in the Dordogne region of southwestern France. It simplified their life and gave them more time and space to devote to their work, something many artists long for at a certain point in their careers. Louppe got her own studio for the first time and no longer needed to juggle her workspace time with Brianchon’s. She doubled down on studio paintings of

still lifes, their house and garden, and the village, all filtered through her idiosyncratically diagrammed compositions.

Alas, Louppe did not date her works, although she signed them with a confident flourish in a distinctive lowercase imprint. Because of this, painstaking research has been necessary to establish a tentative chronology for her output. The timeline that has emerged is often based on stylistic evidence as well as content (e.g., was it painted in Paris or Truffières?), and linked to dated photographs and other archival documents. Even basic facts about Louppe are not always easily confirmed. Since there were no diaries and little correspondence between her and Brianchon, much of their relationship is based on the gathering of related data, from which an idea of their life together can be sketched.

EXPERIMENTS & EVOLUTION

Like many artists of her generation, Louppe’s earliest work was indebted to Vuillard, Bonnard, and other post-impressionists. Inevitably, it includes Parisian street scenes, women at their toilette, and still lifes, the latter a genre she explored throughout life in a range of styles. She was an adept draftsperson and painter, as well as a natural colorist, her earlier works enriched by a full-spectrum palette. The School of Paris was also a great influence.

Louppe’s next phase was based on a fascination with the radical theories of cubism. At first glance, Le violon rouge (The Red Violin), a painting in multiple shades of red that sometimes clash, appears to be cubist-derived, yet she never became a true cubist, even if her vision grew increasingly geometric, abstracted. Translating a threedimensional object onto a two-dimensional surface so that all its facets were simultaneously visible was less interesting to Louppe than mapping the space, diagramming it with an engineer’s eye. In her

investigation, rearrangement, and reconstruction of space, her work can be linked to that of Jacques Villon (the nom de plume of Gaston Duchamp), an artist who moved in the same circles as Louppe and Brianchon.