MARK WHITE

On the Road to Chama 15 x 30, Acrylic Gesso on Canvas

On the Road to Chama 15 x 30, Acrylic Gesso on Canvas

SANDY SCOTT SCULPTURE

Little Blue

An exhibition of new works by Sandy will be presented in October of 2023 at these fine galleries.

The Red Piano Art Gallery 843.247.2226

redpianoartgallery.com

Cheryl Newby Gallery 843.979.0149

cherylnewbygallery.com

kaitee@cherylnewbygallery.com

11096 Ocean Highway Pawleys Island, SC 29585

ben@redpianoartgallery.com 40 Calhoun Street, Suite 201 Bluffton, SC 29910

Celebrating Over 50 Years of Fine Art in The Lowcountry

on a Branch, 18”h x 10”w x 10”d, bronze, ed. 35

on a Branch, 18”h x 10”w x 10”d, bronze, ed. 35

The artist who has his mind… filled with ideas, and his hand made expert by practice, works with ease and readiness; whilst he who would have you believe that he is waiting for the inspirations of genius, is in reality at a loss… The well-grounded painter… is contented that all shall be as great as himself who are willing to undergo the same fatigue: and as his pre-eminence depends not upon a trick, he is free from the painful suspicions of a juggler, who lives in perpetual fear lest his trick should be discovered.

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

jenny buckner

PUBLISHER

B. Eric Rhoads bericrhoads@gmail.com Twitter: @ericrhoads facebook.com/eric.rhoads

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

MANAGING EDITOR

Peter Trippi peter.trippi@gmail.com

917.968.4476

Brida Connolly bconnolly@streamlinepublishing.com 702.665.5283

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Matthias Anderson A llison Malafronte

Kelly Compton Da vid Masello

Max Gillies Louise Nic holson

Daniel Grant Char les Raskob Robinson

DESIGN DIRECTOR

Kenneth Whitney kwhitney@streamlinepublishing.com 561.655.8778

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Alfonso Jones alfonsostreamline@gmail.com 561.327.6033

DIRECTOR OF SALES & MARKETING

Katie Reeves kreeves @streamlinepublishing.com

VENDORS — ADVERTISING & CONVENTIONS

Sarah Webb swebb@streamlinepublishing.com

PROJECT MARKETING SPECIALIST

Christina Stauffer cstauffer @streamlinepublishing.com

SENIOR MARKETING SPECIALISTS

Dave Bernard dbernard@streamlinepublishing .com

Megan Schaugaard mschaugaard@streamlinepublishing .com

Jennifer Taylor jtaylor@streamlinepublishing .com

Gina Ward gward@streamlinepublishing.com

MARKETING COORDINATOR

Brianna Sheridan bsheridan@streamlinepublishing .com

SALES OPERATIONS SUPPORT

Katherine Jennings kjennings@streamlinepublishing .com

EDITOR, FINE ART TODAY

CherieDawn Haas chaas@streamlinepublishing.com

CHAIRMAN/PUBLISHER/CEO

B. Eric Rhoads bericrhoads@gmail.com Twitter: @ericrhoads facebook.com/eric.rhoads

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT/ CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER

Tom Elmo telmo@streamlinepublishing.com

CHIEF REVENUE OFFICER

Jim Speakman jspeakman@streamlinepublishing.com

PRODUCTION DIRECTOR

Nicolynn Kuper nkuper@streamlinepublishing.com

DIRECTOR OF FINANCE

Laura Iserman liserman@streamlinepublishing.com

CONTROLLER

Jaime Osetek jaime@streamlinepublishing.com

STAFF ACCOUNTANT

Nicole Anderson nanderson@streamlinepublishing.com

CIRCULATION COORDINATOR

Sue Henry shenry@streamlinepublishing.com

CUSTOMER SERVICE COORDINATOR

Jessica Smith jsmith@streamlinepublishing.com

ASSISTANT TO THE CHAIRMAN

Ali Cruickshank acruickshank@streamlinepublishing.com

Subscriptions:800.610.5771

Also 561 655.8778 or www.fineartconnoisseur.com

One-year, 6-issue subscription within the United States: $39.98 (International, 6 issues, $76.98).

Two-year, 12-issue subscription within the United States: $59.98 (International, 12 issues, $106.98).

Attention retailers: If you would like to carry Fine Art Connoisseur in your store, please contact Tom Elmo at 561.655.8778.

Copyright ©2022 Streamline

005 Frontispiece: Samuel William Reynolds

016 Publisher’s Letter

020 Editor’s Note

023 Favorite: John Searles on Justin Liam O’Brien

114 Off the Walls

130 Classic Moment: Tina Orsolic Dalessio

055

ARTISTS MAKING THEIR MARK: FIVE TO WATCH

Allison Malafronte and Nicole Borgenicht highlight the talents of Erin Anderson, Jared Brady, Bradley Hankey, Marissa Oosterlee, and Matt Ryder.

060

SANDY SCOTT’S PRODUCTIVE PANDEMIC

By Kelly Compton066

GO WILD

By Max Gillies076

JOHN KOCH: PAINTINGS THAT PUZZLE

By Daniel Grant084

THOMAS HART BENTON: ARTIST IN THE HEARTLAND

By Allison Malafronte088

DRAWING: THE INTIMATE ART

By Richard Halstead092

LETTING GO

By Shirley M. Mueller094

THE FINE ART OF FABRIC

By Leslie Gilbert Elman097

GREAT ART WORLDWIDE

We survey 12 top-notch projects occurring this season.

103

ART IN THE WEST

There are at least 7 great reasons to celebrate the American West this season.

107

A NEW DAY AT OLD LYME

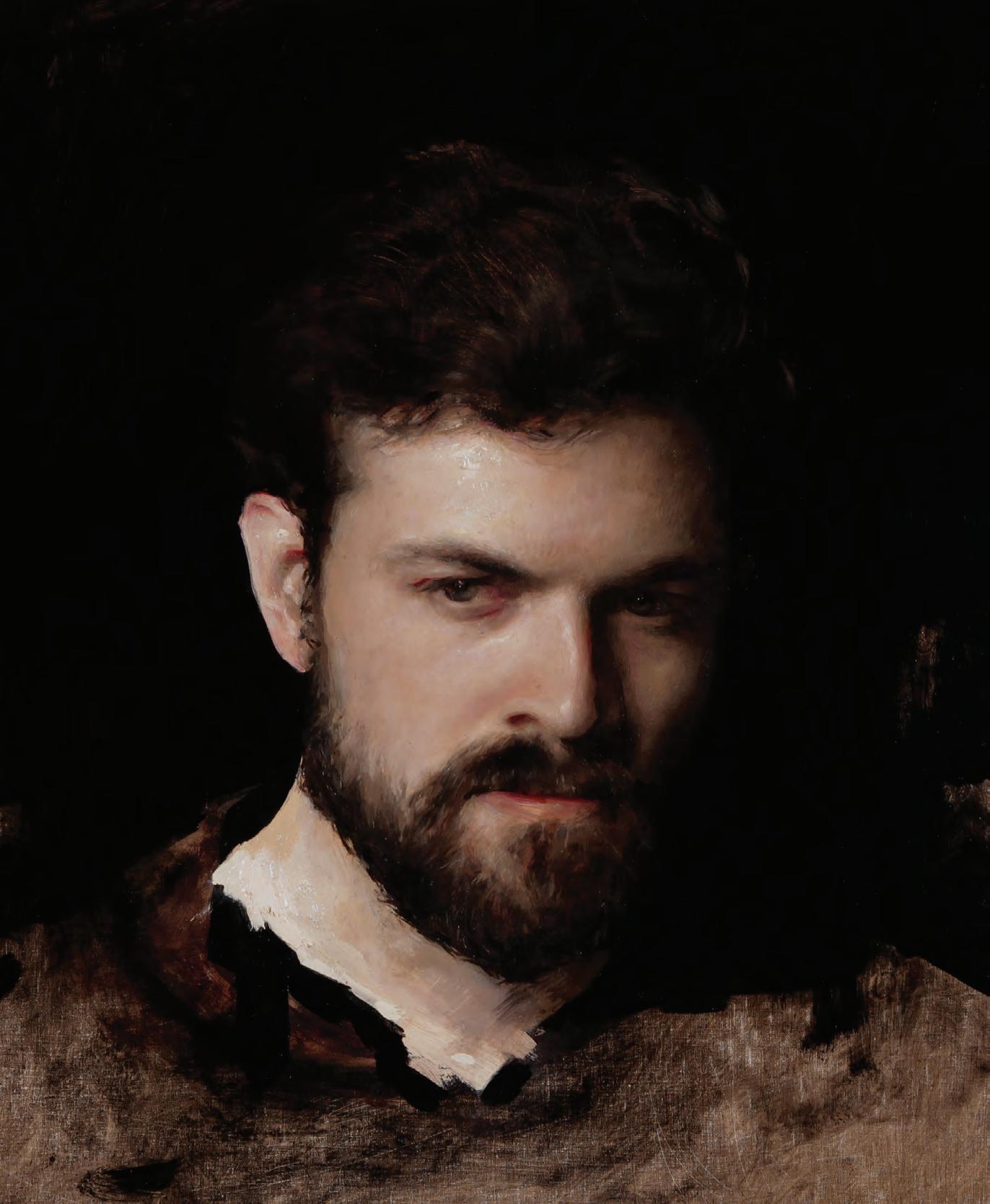

By Peter TrippiJORDAN SOKOL (b. 1979), Portrait of Edmond Rochat (detail), 2016, oil on

13

12 in. (overall), collection of the New Salem Museum and Academy of Fine Art, Massachusetts. For details, please see page 107 .

Fine Art Connoisseur is also available in a digital edition. Please visit fineartconnoisseur.com for details.

Artwork Mediums Artists

Experiences

Live Event:

Jan. 14–Mar. 26, 2023 | Open Daily 10am–6pm Loop 101 & Hayden rd, Scottsdale, Az 480.443.7695

ART AS INVESTMENT

Whether it’s your intention or not, you are making a financial investment every time you buy a work of art for your collection. Even if you have acquired art for enjoyment only, it’s likely that what you own will grow in value over time.

As you continue collecting, it’s wise to consider the longer term. Over the years, I’ve witnessed too many mistakes resulting in unrecoverable losses, tax assessments on heirs that could have been avoided, and massive collections with no remaining “street value.” One collector I know invested $1 million in paintings by a “hot” artist who is now forgotten, which is a shame because my acquaintance could really use that money. (Laurence C. Zale and I have co-authored a report, “The 7 Most Serious Financial Mistakes Made by Art Collectors,” available for free at collectormistakes.com.)

So what will become of the art that adorns your homes and offices? What is your long-term plan? Will your heirs recognize the value of your artworks, or will your “old things” end up mislabeled and underpriced at Goodwill and eBay?

You already have a strategy for your financial investments, so now establish one for your art. Without a plan, you can pretty much expect the worst possible outcome. Depressing as it may sound, you should start at the end of your journey: what will happen after you pass? Do you want to endow your own museum so that your collection — and your name — live on? Do you want to leave the artworks to existing museums? (Note: They probably don’t want most of your collection, so check before you designate them in your will. If you don’t do so, your art may end up in storage, or worse.) Finally, if the collection need not remain intact, how can

you help heirs obtain maximum value if or when they decide to sell? Trust and estate attorneys are perfectly positioned to help you pose and answer important questions like these.

Returning to the present, many collectors focus on a single artist whom they believe will grow in value. (It’s easy to learn if an artist’s sale prices are rising.) Buying the best piece from that artist once each year is a great strategy. Of course, what goes up sometimes goes down, so spreading your “risk” is even smarter. (My aforementioned friend later regretted not diversifying his “exposure.”)

If you can, follow and buy from four artists every year or, ideally, even more. (Experts say that buying regularly from 14 different artists seems to be the magic number, but that’s a lot of art!) Always buy the artist’s best work, expect to pay a slightly higher price each year, and be thankful that the artist is indeed growing more valuable.

Like many other collectors, I kick myself for passing on opportunities to buy works by certain younger artists who were selling low at the time. What once brought a couple of thousand dollars can, in some cases, soar to a couple of hundred thousand within a decade. Fortunately, I did not pass on all of them.

So which artists are worth watching? One of our jobs at Fine Art Connoisseur is to highlight artists we admire, and because we don’t run articles in exchange for advertising, you can trust our judgment. You can also learn who’s noteworthy by consulting reputable dealers and advisers.

Though people keep saying the Internet has eliminated the need for galleries, that is simply not true. The best dealers follow their markets closely, know which artists are on the move, and ultimately drive prices upward as scarcity grows, which is a good thing. Building a strong relationship with at

least two or three dealers or advisers is critical; you already know that’s true for financial advisers. Though you may pay a modest premium for their expertise (in the form of commissions or mark-up, for example), it will always make a significant difference in the long run.

To me, art possesses significance far beyond financial value, but that doesn’t mean I lack a collecting plan for the present, or for the future.

Disclaimer: I am not a professional adviser and am sharing my opinions only, so I recommend you meet with a qualified adviser soon.

B. ERIC RHOADSChairman/Publisher

bericrhoads@gmail.com

facebook.com/eric.rhoads @ericrhoads

08.29 - 09.23

SUN PRAYER BY ANTHONY WINTERS

DAYS END BY KATHRYN MCMAHON

THE RED DOOR BY JOHN DORCHESTER

LOOKING FORWARD

It is hard to believe 10 months have passed since we concluded the second edition of Realism Live — a virtual art convention that teaches realist techniques for painting and drawing portraits, figures, landscapes, flowers, other still lifes, and more. Like the inaugural edition in 2020, last year’s was a huge success, and now the team from Fine Art Connoisseur and RealismToday. com are busy finalizing Realism Live 3.0.

their eyes and enhancing confidence in their ability to paint and draw. On offer for the following three days are art instruction demonstrations, critiques, and roundtable discussions among artists and other experts.

For all sorts of reasons (not just pandemicrelated ones), the art world has gone digital in a big way. Once again, Realism Live participants will use Streamline Publishing’s sophisticated community platform to interact; it is set up so that you deal only with our faculty and your fellow registrants. This is not an event open to the general public. Our participants have hailed from 30 countries, and now we are expecting an even broader turnout.

As ever, this event has been designed for artists and enthusiasts at all levels of experience, from the highly accomplished to those just starting out. Beginner’s Day will occur on Wednesday, November 9, and the main program will follow on November 10, 11, and 12. By press time we were thrilled to have secured for our faculty some of the most outstanding artists in the field, including Clyde Aspevig, Michelle Dunaway, Daniel Graves, Lisa Egeli, Rose Frantzen, Alex Kelly, Michael Mentler, Chuck Morris, Ned Mueller, John Pototschnik, Sarah Sedwick, Terry Strickland, Dustin Van Wechel, and Glenn Vilppu. More renowned talents are being added to the roster every week. Beginner’s Day will help all viewers — not just novices — get to the next level, opening

The beauty of it all, of course, is that everyone can participate safely from their own homes and studios. Our previous registrants have learned from the faculty, built a community and support network for themselves, and made lifelong friendships. They tell us that what they learned has kept their work looking real, but not like a photograph; that they can give their impression of a scene without going too far; that they feel better equipped to convey the truth in their own artistic voice; and that they have created a signature look. Best of all, they continue to grow and learn from what they experienced. These are impressive results after only four days together.

Please visit realismlive.com now to learn more and register, and see you this November, at the latest.

P.S. If you can’t make the actual “live” dates, don’t worry: replays are available to all who sign up (but not to those who don’t).

JACKSON: (307) 733-3186 | SCOTTSDALE: (480) 945-7751 TRAILSIDEGALLERIES.COM

KRYSTII MELAINE

Melaine“Flamingos are such elegant birds, with their beautifully sinuous curving necks and pink feathers making them one of my favorites to paint. These two face in opposite directions but are of one mind. Where one goes, the other and their entire flock goes. They all rouse from sleep, seek food, then preen and socialize at the same time. Seeing a huge flock of thousands take off and fly together or display together is an amazing sight. I wonder how they all decide to partake of the same activity at once. Is it a meeting of minds in some silent communication system? We may never know, but we can enjoy their colorful presence in our world.” — Krystii

John Searles is always looking for a story he can tell, often on the page to his many readers. One of America’s bestselling novelists, he has published four books to date, including his most recent, Her Last Affair. Indicative of his ability to find or invent stories, Searles says of this drawing by the artist Justin Liam O’Brien, “When I look at this work showing three figures, I see the same person — as a young man, a middle-aged man, and an older man. When I mentioned this to my husband, Thomas, he insisted that the drawing shows three people. But I still see the same person picking reeds at the shoreline at different stages of his life.”

Searles recalls coming upon O’Brien’s art at the Monya Rowe Gallery in New York City — and being instantly engaged. “I knew that Justin was a young gay artist, and that interested me in particular. I love the storytelling that goes on in his scenes. I’m also a sucker for anything blue and beautiful and peaceful,” which aptly describes the Sag Harbor locale where Searles and his theater-director husband live much of the time. In that bucolic, decidedly literary town on Long Island’s East End, the couple and their dog, Ruby, walk daily by the calm, blue bay.

As for his increasing familiarity with O’Brien’s growing oeuvre, Searles says,

“When something or someone gets my interest, I go into a deep dive of researching. The more I saw of his work, the more I responded to his aesthetic.” As another example of Searles’s penchant for research, it was while he kept passing an abandoned drive-in theater in upstate New York that the idea for Her Last Affair arose. Upon learning the drive-in’s history and the roster of films once shown there, Searles invented a storyline so compelling that it reads with the speed and immediacy of a movie. “I think all good writing is cinematic, and because this book is set at an old theater, I started a story about film and I kept writing.”

While Searles’s novels are often categorized as thrillers, that description is too facile. “Each book is its own thing with original characters, and the process of developing plot is always trial and error. I think of my

books as genre hybrids — part character study, part thriller, part noir fiction, a study of the human condition.”

And so it makes perfect sense that Searles would respond viscerally to O’Brien’s paintings, many of which convey narratives with often erotic undertones. “Phrygian Gates, which is more subtle than O’Brien’s others, makes me think of Sag Harbor, which is serene and peaceful, but which also has a lonely feeling to it. I often have a bit of a lonely feeling. There’s a melancholy about this painting.”

As for his writing process, Searles admits, “I’m really an eavesdropper. My sister gave me a T-shirt saying, ‘Careful or you’ll wind up in my novel.’ I’m always noticing things.” He definitely noticed Justin Liam O’Brien’s art.

2022 Best of America National Juried Exhibition

The Wilcox Gallery

1975 N US Highway 89

Jackson, WY

September 8-October 8, 2022

Opening Reception September 16, 5-7pm

Visit www.noaps.org for details and events

EXHIBITIONS FOR 2023

2023 Best of America Small Works

National Juried Exhibition

Mary Williams Gallery

5311 Western Ave. #112

Boulder, CO

May 18-June 17, 2023

Opening Reception: May 18, 5-8pm

2023 Best of America National Juried Exhibition

The Principle Alexandria

208 King Street

Alexandria, VA

August 11-September 10, 2023

Opening Reception: August 11, 6-8:30pm

Spring International Online Exhibition

Entries open January 1, 2023

Fall International Online Exhibition

Entries open July 1, 2023

Associate Online Exhibition

Entries open April 17, 2023

SEPTEMBER 15 - OCTOBER 22, 2022

23rd ANNUAL NATIONAL JURIED EXHIBITION

OPENING WEEK!

Events include painting at multiple locations, critiques, painting demos, presentations and receptions with no fee for all current AIS members!

September 13-14 Workshop

September 12-17 AIS All-Member Paintout

Thursday, September 15

Opening Reception and Awards

Exhibition features 175 artworks in oil, watercolor, pastel, gouache and acrylic. All work available for purchase and publ ished in an exhibition catalog.

Saturday, September 17

Wet Wall Exhibition and Sale

View and purchase artwork created on site in Boulder during the Paintout!

American Impressionist Society was founded in 1998 to promote the appreciation of Impressionism through exhibitions, workshops and events. Four exhibitions are offered each year--two in galleries and two online.

Memberships are open to American Impressionist artists who are United States residents and anyone who wishes to support American Impressionism and our mission. Today over 2,000 artists are AIS members!

FOR MORE INFORMATION: americanimpressionistsociety.org 231-881-7685

LAURIE HENDRICKS MFA

South Pasadena, California

Café de L’Etang, 20 x 24 in., oil on canvas lauriehendricksart@gmail.com | www.lauriehendricksart.com

Artist Member, California Art Club

JENNIFER RIEFENBERG

Cedaredge, Colorado

Autumn Harmony, 20 x 24 in., oil on canvas jennifer@artofsunshine.com | 303.250.2015 www.artofsunshine.com

Represented by Mary Williams Fine Arts, Boulder, CO

THERESA

Gulf Breeze, Florida

Shaped by Tides and Time , 12 x 16 in., oil on linen-covered birch panel art@theresagrillolaird.com | 850.261.6006 | www.theresagrillolaird.com

MO MYRA

Hartford County, Connecticut Naptime , 11 x 16 in., watercolor momyrawatercolor@gmail.com | www.momyra.com Gallery inquiries welcome

GRILLO LAIRD FINE ART

GRILLO LAIRD FINE ART

HEATHER ARENAS

Myakka City, Florida

Your Move!, 24 x 30 in., oil on cradled wood artist@heatherarenas.com

720.281.4632 www.heatherarenas.com

Represented by Reinert Fine Art, Charleston, SC; Mary Williams Fine Art, Boulder, CO

BARB WALKER

Canton,

CAROLYN LINDSEY

Cuervo,

BRENDA BOYLAN

Beaverton, Oregon

A Secret Place , 48 x 60 in., oil on gallery-wrapped canvas, $23,970 503.702.2403 www.brendaboylan.com

Represented by Art Elements Gallery, Newberg, OR; Illume Gallery of Fine Art, St. George, UT

SHELBY KEEFE

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Made in the Shade , 18 x 24 in., oil on canvas, 2020 shelbykeefe@me.com www.studioshelby.com

This summer and fall, Couse-Sharp

Historic Site presents Taos painter Jivan Lee’s exciting new installation of multipart works focused on the sunlit, cloud-kissed landscapes of northern New Mexico. The pieces act as records of immersion in the landscape, akin to maps of the experience of being in a place on a given day.

TheInfiniteLandscape explores how artifacts of our attention and the dynamics of weather and light coincide to shape what we see.

EXHIBITION IN THE LUNDER RESEARCH CENTER 138 Kit Carson Road through November 30 Open Mon–Sat 1–5 Free admission, donations welcomed

575.751.0369

admin@couse-sharp.org

thecousesharphistoricsite

cousesharp

@CouseSharp

couse-sharp.org

Taos, New Mexico, USA

•

Beauty in the Hamptons

C4C 2022 Arts Weekend

BEAUTY EXHIBITION & SALE - DEVON COLONY IN THE HAMPTONS

OPENING BY INVITATION - OCTOBER 7, 4PM-8PM

PUBLIC VIEWING - OCTOBER 8, 11AM-4PM

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Reservations & C4C Hamptons Schedule of Events: www.windowstothedivine.org (Upcoming Events)

Shannon Robinson, Chairperson 303-679-1365 or shannon@artistcalling.com

Lu Cong

Scott Fraser

Ron Hicks

Quang Ho

Dan McCaw

Danny McCaw

John McCaw

CW Mundy Daniel Sprick

Adrienne Stein

Vincent Xeus (Fra Angelico Artist of the Year)

Scott Fraser • Queen Alexandra • Oil

Lu Cong

Scott Fraser

Ron Hicks

Quang Ho

Dan McCaw

Danny McCaw

John McCaw

CW Mundy Daniel Sprick

Adrienne Stein

Vincent Xeus (Fra Angelico Artist of the Year)

Scott Fraser • Queen Alexandra • Oil

BARBARA JAENICKE

ANN GOBLE

Gainesville, Georgia

Chasing the Sun, 9 x 12 in., oil on board goble@charter.net | www.anngoble.com

Represented by Reinert Fine Art, Charleston, SC

Society of Animal Artists

62nd Art & the Animal Exhibition

PREMIERE

Turtle Bay Exploration Park, Redding, CA turtlebay.org

September 24, 2022 – January 1, 2023

TOUR

The Hiram Blauvelt Art Museum, Oradell, NJ blauveltartmuseum.com

November 19, 2022 – January 15, 2023

The Ella Carothers Dunnegan Gallery of Art, Bolivar, MO dunnegangallery.org

February 11 – April 2, 2023

www.societyofanimalartists.com

POKEY PARK

Tucson, Arizona

Tom Cat, 8 x 11 x 9 in., bronze pokey@pokeypark.com | 520.869.6435 | www.pokeypark.com

Represented by K. Newby Gallery, Tubac, AZ; Lovetts Gallery, Tulsa, OK; Smith Klein Gallery, Boulder, CO

The Red Queen by Jeremy Bradshaw

The Red Queen by Jeremy Bradshaw

ROSETTA

Loveland, Colorado

Balancing Act, 9 1/2 x 17 1/2 x 4 1/2 in., bronze rosetta@rosettasculpture.com | 970.667.6265 | www.rosettasculpture.com

Represented by Bronze Coast, Cannon Beach, OR; Sorrel Sky, Durango, CO; Wilcox Gallery, Jackson, WY

CARRIE COOK

Austin, Texas Louie, 40 x 20 in., oil on canvas carriecookstudio@gmail.com

www.carriecook.com

Represented by Worrell Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

JILL CORLESS

North Redington Beach, Florida

On the Rocks, 20 x 28 in., pastel corlessp@bellsouth.net | www.jillcorlessfineartgallery.com

Gallery inquiries welcome; Woodfield Fine Art, St. Petersburg, FL; Lowcountry Artists Gallery, Charleston, SC

The sun lowers on the spire of the San Miguel Mission as afternoon light illuminates the distant clouds. Painted from a plein air sketch, the fleeting light is captured in thick, textural strokes of vibrating color.

BRAD TEARE discovered his love for thick paint at a Van Gogh exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum in New York City. Surprised by the impact the paintings had in person, Teare began exploring texture by painting with palette knives in rich, multi-hued strokes.

WESTERN ART SHOWCASE

“The American West” means many different things to many different people, and that fact should make us all glad. At Fine Art Connoisseur we have long been keenly aware of how art of the West differs from — and overlaps with — art made in or about the rest of this remarkable country. That’s one reason every issue of this magazine contains a separate section called “Art in the West” — to underscore that very point. Its existence does not mean we have passed on a comparable section titled, say, “Art in the Northeast.” Rather, it’s recognition of the fact that Western vitality in the fields of historic and contemporary realism is so noticeably strong that it shouldn’t be overlooked or made to wait on the sidelines. It makes perfect sense, then, that this Western Art Showcase appears in our pages annually as yet another reminder of all the good things going on there, artistically and otherwise. Enjoy, thanks and congratulations to everyone involved, and please keep up the great work!

Peter Trippi, Editor-in-Chief Fine Art Connoisseur

Peter Trippi, Editor-in-Chief Fine Art Connoisseur

DAVID FREDERICK RILEY

Midway, Utah

Zeroed In, 60 x 48 in., oil on canvas info@davidfrederickriley.com www.davidfrederickriley.com

CHRIS KOLUPSKI

Rochester, New York

Morning Gossip, 10 x 20 in., oil on linen panel

Three Sisters and the Thumb, 10 x 20 in., oil on linen panel ckolupski@gmail.com 585.313.3543

www.chriskolupski.com

Gallery inquiries welcome

BRUCE PIERCE

Manhattan, Montana Sage Creek Surprise, 32 x 48 in., oil on linen artistbdp@yahoo.com 406.209.4484

www.brucepierceart.com

GEORGE LOCKWOOD

California Central Coast Heart of the North, 24 x 30 in., acrylic on board geolockwood@verizon.net www.glockwoodart.com

BRENT FLORY

Wallsburg, Utah

Changing Seasons, 48 x 24 in., oil on board Of Blankets Bells and Beads, 48 x 24 in., oil on board bpflory@hotmail.com 435.671.7518

www.facebook.com/brentfloryfineart

Represented by Going to the Sun Gallery, Whitefish, MT; Native Gallery, Jackson, WY; Western Skies Fine Art, Afton, WY

MATT RYDER (b. 1981) is a British painter based in Dubai who is steadily becoming better known in the U.S. His journey in art started early but took a bit of a circuitous path — in his 20s Ryder left art school and abandoned painting for 10 years after a discouraging experience with an instructor — but eventually he returned to his true passion. In 2005, he moved to Dubai to embark on a full-time career as a professional painter and has never looked back.

For many years, large-scale landscapes from the scenic mountains and deserts surrounding Dubai were Ryder’s forte and focus. “It’s very difficult to explain the feeling of standing at the base of one of these mountains, how grand it is,” the artist says in a short film describing his work and motivations. “The way the light filters into these big mountain ranges, it’s very reminiscent of America’s Southwestern landscape. The paintings I’m doing, they are big, they are bold. I work on a large scale generally when I’m in the studio in order to capture this grandeur.”

Ryder then started exploring a subject he has long loved: flowers. A crowded genre to be sure, but Ryder nonetheless found his place in this arena, and today he paints large floral scenes as if they were vast landscapes, even if just a few flowers are center stage. Other times, he’ll paint smaller, detailed floral portraits, as in Ascension, illustrated here. Designed in a 2:1 format, these garden roses get all the glory and

attention, with the artist taking time to give each pillowy bloom the variegated color and fine detail it deserves.

Regardless of the subject, Ryder’s love of light and the way it creates movement, rhythm, and patterns in and around objects is often the theme. “I always seek light patterns and shapes that will form interesting and strong compositions,” he explains. “I find that the more I paint, the more I’m drawn to naturally lit subjects, whether it’s a still life by the window or a desert landscape.”

Ryder plans to be in the U.S. quite a bit in the coming months. In October, filming an instructional video for Streamline Publishing will bring him to Texas, and in February 2023 he’ll visit the Scottsdale Artists’ School to teach his second workshop there. And there will be plenty of time back home in the studio. “I have a very clear vision of the future,” Ryder says. “I know where I want to be, and what I have to do to get there. Now it’s just about putting in the work to make sure that happens.”

There is a lot of superb art being made these days, so this column shines light on five gifted individuals. All profiles were written by Allison Malafronte except Bradley Hankey’s by Nicole Borgenicht.MATT RYDER (b. 1981), Ascension , 2022, oil on linen, 10 x 20 in., private collection

MARISSA OOSTERLEE

(b. 1981) is recognized the world over for her hyper-realistic portrayals of women submerged or floating in water, a symbolic representa tion of the passing of time and life’s changing tides. Her preoccupation with water and the ocean is apropos, considering that “Marissa” means “from the sea/mermaid” in Latin and that another of her other passions is raising awareness and funding for environmental causes.

Currently residing in Spain, Oosterlee grew up in the Netherlands and was always an artist at heart. At 20, she found her way back to the studio after sustaining a serious injury on the road to becoming a semi-professional cyclist. Today Oosterlee creates polished, glistening portraits of women in the sea using an airbrush technique with either oil or acrylic paint.

In 2019, the artist began a series of paintings called Washing Away My Sorrows, using water as a symbol of purity, clarity, and tranquility. “This series was originally based on my own feelings involving personal issues (health, past relationships, and family matters) and also on my active involvement in environmental issues, particularly ocean life,” Oosterlee explains. “It grew from there and became about the empowerment we experience when we remove ourselves from the fires that forge and shape us as women.”

In 2020, at the height of the BLM movement, a woman named Saraa Kami contacted Oosterlee to say how much she admired her art, and also to ask why it never featured women of color. “She had just posted a preview of some upcoming releases,” Kami recalls. “As a longtime follower of Marissa’s work, I felt slighted and reached out.

Much to my surprise, she responded right away. Shortly after, we chatted on WhatsApp and she heard me out.”

Oosterlee told Kami that George Floyd’s recent death had struck a deep chord and she was ready to make a shift toward more diversity. In the next few months, she partnered with Kami to create an additional segment to the Washing Away My Sorrows series, of which Hope is a part. Kami secured a group of models of color for a shoot, photographed them, and sent the results to Oosterlee to work from. “I’m not a professional photographer, just a woman of color who wanted future generations to see beautiful depictions of women of color hanging on the walls of museums and galleries,” Kami says of their collaboration, for which she willingly volunteered her time.

“Washing Away My Sorrows — BLM was my attempt to place the beauty of all women on full display,” Oosterlee shares. “Although I’ve always celebrated the beauty of black and brown women as a person, admittedly that wasn’t always evident in my work. So being a part of the healing process for brown and black women in 2020 is something I’m extremely proud of. I’m also excited for the other paintings in this series to be introduced throughout 2022, and for the world to behold the beauty of a human being on its face, not by placing an adjective before it. Our ethnic identities are just that, and the only race that exists is the human race. That is what Washing Away My Sorrows — BLM is all about: seeing and celebrating beauty.”

Oosterlee is self-represented.

If you happen to stumble upon a young man in a Colorado forest wielding his brush with both fierceness and finesse, it may well be the painter JARED BRADY (b. 1998). Out in the wilderness, he is not only able to engage in the challenging yet therapeutic act of painting, but also to document his adventures while communing with nature. “Something about the forest has always transfixed me,” Brady explains. “The abstraction, flow, and complexity have always drawn me in. When a subject seems too difficult or out of reach, I gain so much when I push myself to take it on.”

Brady paints in the mountains and valleys near his Colorado home in every season and at every time of day. In the fall, he may arise before sunrise to hike to his favorite spot and paint studies and gather reference photos of the early-morning glow. In winter, a twilight scene after sunset with cool light and shadows dancing may catch his eye, or perhaps it’s the graceful morning light after the previous day’s snowfall, as in Softly Falls the Light, illustrated here. “This is a scene from my favorite valley near my house,” Brady notes. “It had snowed the night before and the next day we had sunshine and clear blue skies. It was a perfect day to hike around with my pups to look at all the beauty. I came upon this scene and was instantly hooked. I did a small study on location and then used the study and photo references to paint this larger piece in my studio.”

When not traversing the great outdoors in search of subject matter, Brady can be found in his studio painting still lifes in a

romantic realist style. Particularly evident in this genre is the influence of two of his teachers, Quang Ho and Daniel Keys; he took workshops with both while in his early 20s. Brady’s first introduction to oil painting and representational art, however, happened at 16 through the artist Kenneth Shanika, who taught him the basics of traditional technique. Brady then built upon that foundation through self-study and practice.

Regardless of the subject, Brady has trained his eye to find something paintable in every situation. “There is beauty everywhere I look,” he says. “The same visual concepts that excite me in a grand vista can also be found in a simple still life.”

Over the last several years, ERIN ANDERSON (b. 1987) has used her artistic gifts to explore the fundamental ways humans remain connected to one another while retaining their individuality. Several of these series, created prior to the pandemic, became even more relevant to the artist and her viewers during the ensuing period of isolation and disruption.

For these scenes, Anderson often begins by conducting scientific-like research or observation, unearthing the interconnectedness among primal elements in nature and applying it to innate correlations in her figures. “In one series, I used imagery from patterns in nature for my compositional inspiration, spending hours looking closely at such things as topographical maps, wind maps, and water currents to see what kinds of patterns and forms they created,” the artist shares. “I like to think the connection we have to one another is similar to the way elements in nature are connected.”

In another series, Anderson chose root systems and tree trunks as her starting point, etching them throughout paintings that speak to women’s separate yet shared experiences. In the diptych Twins, illustrated here, she again turned her attention toward female connectivity,

this time focusing on subjects she knows personally. “These figures are two of my best childhood friends, who happen to be twins,” she explains. “I wanted to allude to the idea of a shared history.”

Twins is also the first work where Anderson experimented with the technique of copper sheet “canvases.” “I like to push myself to find different ways to use copper,” she says. “Previously I used paint or natural patina to create dark values in the background. For Twins, I used a torch on the copper panel to bring out a brilliant rainbow of colors. The results are so fun and interesting to work with!”

An Ohio native, Anderson developed her drawing skills and oil-painting technique from a young age, copying the Old Masters at the Toledo Museum of Art. In 2009, she earned a B.A. in psychology and entrepreneurship from Ohio’s Miami University. Soon after, she enrolled in an independent art program at Pennsylvania’s Waichulis Studio, and she now lives in Ohio again.

Originally from Oregon, the painter BRADLEY HANKEY (b. 1979) attended Boston’s Massachusetts College of Art and Design and has been based in Los Angeles since 2009. In 2020, the artist took many reference photographs during a memorable helicopter ride that inspired a series of major paintings of Southern California’s distinctive convergence of city and sea. Works resulting from yet another helicopter flight taken this February will appear in a show to be mounted by the other passenger on that aerial adventure, dealer Lia Skidmore.

Fortunately, we need not wait for a glimpse of what’s in store. Available now from Hankey’s other representative, Sue Greenwood Fine Art, is the scene illustrated here, Always You, which constitutes a kind of bridge between 2020’s nocturnal scenes and the dusky ones he will show next. Always You draws its title from Hankey’s first date with his now-partner, almost a decade ago — an evening that launched a relationship he says was “meant to be.”

Hankey thinks the phrase “emotional realism” describes his art best: “The scene depicted in Always You made an emotional impact on me, which is why I took a photo of it. And that moment of emotional impact is what I sought to convey in the painting.” Always You certainly is realistic, yet it also reflects Hankey’s engagement with abstraction: “I love using solid blocks of color wherever I can, and

especially in urban landscapes, where a structure is often reduced to a simple shape with a single color.”

In his nocturnal series, Hankey used a rich, dark palette, but Always You incorporates pastel hues, a shift that makes sense when we consider how much more light the dusk encompasses. The artist notes, “The sky and water are built up with glazes, transparent layers of paint that blend optically to form a richer color. The cityscape is also built up in layers, but opaque ones. Single brushstrokes represent entire buildings, and dots represent a range of light sources.”

It is a pleasure to view Hankey’s work in person, first up close to admire his “simple” strokes of paint, then backing away to watch them coalesce. The resulting sense of discovery, even surprise, relies upon the tension between rhythm and painterliness. Here the Santa Monica Pier’s shimmering lights — flashes of energy — contrast with the dark, expansive planes of sky and ocean that convey nature’s power, and its comparative calm. Finding that balance is not easy, but Hankey has mastered it, and we look forward to seeing more dusk scenes.

TODAY’S MASTERS

SANDY SCOTT’S PRODUCTIVE PANDEMIC

You can never tell how a global catastrophe such as the COVID-19 pan demic might impact a specific person. Fortunately, the Wyomingbased sculptor Sandy Scott (b. 1943) has done just fine. “Some artists fell into creative funks,” she says, “but I became more energized and actually experienced one of my most produc tive periods ever.”

Delighting Scott’s collectors and admirers nationwide this autumn is the arrival of more than 30 new pieces, which she has nick named the COVID Collection because “most would not exist had COVID not made possible the enormous amount of studio time I’ve enjoyed.” The artist is quick to note, however, that guiding each work through her trusted foundry (Eagle Bronze) has been challenging because its project backlog exploded during 2020, and because the casting and finishing pro cess is so detail-oriented and labor-intensive in the first place.

Born in Iowa and raised in Oklahoma, Scott admired animals from an early age because her father bred quarter horses. She studied at the Kansas City Art Institute and later worked as an animation background artist in the motion picture industry, turning her attention to printmaking in the 1970s and finally to sculpture in the ’80s. Today Scott works in Lander, Wyoming, near that superb foundry that casts her bronzes, though she also maintains a studio in Ontario.

An avid outdoorswoman who loves to hunt and fish, Scott has made 16 trips to Alaska as well as trips to Europe, Russia, China, and South America. A licensed pilot for more than half a century, she believes her “knowledge of aerodynamics has been helpful in achieving the illusion of movement in my bird sculptures.” Though Scott remains com mitted to conducting field work in order to know and accurately present her subjects, it goes without saying that several research trips were put on hold beginning in March 2020. “COVID-19 has had me studio-bound,” she says, “so much of the new work reflects travel that occurred before the pandemic, including — for example — my 2019 adventure in Morocco. Yet I still haven’t violated my self-imposed rule of never modeling an animal unless I have experienced it in the field.”

Everyone at Fine Art Connoisseur was delighted recently when Sandy Scott kindly offered to tell us about some of the new works — in her own words. Here, then, are 10 of our favorites, described by the master herself.

No bird better shows attitude than a rooster; with his chest out, tail up, and comb erect, he struts forward to meet the break of day. The passive and active elements of the bird’s shapes present an exciting design opportunity for any sculptor. I have combined the shapes of body mass and tail profusion with controlled modeling of the head and feet in an attempt to design a symbol of arrogance and spirit. Roosters look especially great displayed in kitchens; this one lives in mine.

My personal ideal of equine aesthetic perfection is an ongoing pursuit, so at any given time I have several horse sculptures in progress. I’m influenced by Greek and Renaissance prototypes as well as by the 19th-century masters Antoine-Louis Barye and Emmanuel Frémiet, and also Anna Hyatt Huntington and Adolph Weinman from the 20th century. My goal while creating Tempest was to present a feeling of dignity and drama with a symbolic pose of wind-tossed mane depicting power, beauty, and proportion. As a lover of horses, someone who grew up with and has always owned them, I enter the realm of instinct while contemplating the design of what I consider the most beautiful animal on Earth.

This head study was a nightmare for the mold maker and for the foundry to cast. We spent many hours consulting the technicians and relying on their assistance during the production process. The image stems from an unforgettable trip to Tanzania several years ago with a group of artist friends: John Agnew, Julie Askew, Robert Caldwell, Paul Dixon, James Gary Hines, Jan Martin McGuire, Tony Pridham, and Dale Weiler. With our guide and Land Rover, we spent hours at water holes in search of closeups and details of various species, returning home with more than 15,000 digital images. Famous for the long black plumes on its head, the secretary bird is a raptor closely related to the osprey and can be found stomping snakes in sub-Saharan

The American bison, or buffalo, has been elevated to the stature of the American bald eagle as an emblem of our great country. Under recent U.S. legislation, the bison became the National Mammal due to its economic and cultural significance over the centuries. More than 60 million of them once roamed North America, but by 1890 their story almost ended in extinction. Today the largest population resides in Yellowstone National Park — two hours from my studio. While the bison has long been one of my favorite subjects, it is more than an animal to me: it is an emotional manifesto that exemplifies my deep affinity for the West and its history.

The grizzly bear is common where my studio is located, at the base of the Wind River Range in the wild state of Wyoming. I’ve encountered the animal only once while hiking in the high country, but I routinely see them nearby in Yellowstone. The anatomy of an animal with such thick fur or hair must be fully understood in order to avoid modeling a shapeless mass; sometimes that means using artistic license to “trick” viewers into seeing the anatomy correctly.

The genesis of this sculpture was a scene I witnessed on a hike in Jackson, Wyoming. After hearing a riotous cacophony of croaks and squawks, I used my binoculars to spy a pair of ravens a short distance away. One bird was silent — with a seemingly aloof attitude — while the other was totally “in your face.” The drama of that event struck me and now this sculpture speaks for itself.

In the late 17th century, hunting scenes and still lifes became more popular than religious imagery in newly Protestant Holland because they reflected the “real,” secular world. And of course the depiction of fur, feathers, and gills in sporting scenes remains a traditional motif to this day. This work was inspired by an autumn hunt near my Lake of the Woods studio in Ontario with our beloved Brittany dog, Penny. The delicious bird was enjoyed on Canadian Thanksgiving, which occurs in October.

Rock of Liberty, of 25), 33 x 32 x 27 in.

My eagle sculptures have been placed at many venues nationwide, including the National Museum of Wildlife Art (Jackson Hole), William J. Clinton Presidential Library & Museum (Little Rock), Brookgreen Gardens (South Carolina), and San Francisco’s Presidio. This iconic bird continues to inspire me and serve as a reminder of my love of country. For this new work, which has been designed for placement indoors or outdoors, I combined uncomplicated shapes and a strong silhouette in an effort to communicate power. The rock merging with the bird’s mass suggests the solidarity and resolve of America.

Herons are long-legged, long-necked freshwater coastal birds that are also found along rivers and ponds. Their pointed dagger-like bill is perfect for catching fish and frogs. The design source for this image was the tricolored heron, a sleek, slender, and fairly small bird compared to its cousin, the great blue heron. Reference for this work was gathered at Port Aransas on Texas’s Gulf Coast; it is the latest addition to my growing portfolio of coastal, wading, and shore birds.

This work was modeled in the spring of 2020 when, like many folks, Trish and I bought a new puppy as it became clear we would remain house-bound for quite a while. We had lost our 14-year-old Scottie the year before, and we (along with our old bird dog) missed her terribly. As soon as the new pup arrived, everyone was happy again. The interaction between the old dog and the new one was sheer joy and presented the perfect models. Like many other works, this has yet to be molded and cast; many will be introduced in October 2023 at Cheryl Newby Gallery and Red Piano. (Please see Information below.)

Information: sandyscott.com, sandyscottblog.blogspot.com x width x depth. Scott is represented by the following galleries: Broadmoor (Colorado Springs), Cheryl Newby (Pawley’s Island, SC), Columbine (Loveland, CO), Davis & Blevins (Saint Jo, TX), McBride (Annapolis), Montgomery-Lee (Park City, UT), Mountain Trails (Santa Fe), Red Piano (Bluffton, SC), and Wilcox (Jackson Hole).

KELLY COMPTON is a contributing writer to Fine Art Connoisseur.

TODAY’S MASTERS

GO WILD

As fellow residents of Earth, wild animals have always fascinated humans, especially the artists among us. Thus many creatures appear in prehistoric cave paintings, and today the desire to depict them endures, stronger than ever.

The artworks illustrated here confirm this ongoing enthusiasm, and it’s easy to learn more thanks to a host of activities happening across North America. For example, in Charleston next February, the annual Southeastern Wildlife Exposition (sewe.com) will again delight animal lovers with exhibitions, demos, and other activities highlighting the importance of conservation. Touring the country are the annual Art and the Animal exhibitions organized by the Society of Animal Artists (societyofanimalartists.com), and then there is the annual festival hosted by Artists for Conservation

(artistsforconservation.org), which features an exhibition by leading international artists, screenings, demos, and performances. (This year’s edition is scheduled for September 22–25 in Vancouver.) Look out, too, for the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole (Wyoming, wildlifeart.org) and Wisconsin’s Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum (lywam.org), which hosts an annual Birds in Art exhibition.

These are just a few of the impressive array of offerings in wildlife art — all encouraging evidence that this longstanding genre is alive and well.

(CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT) GARY JOHNSON (b. 1953), African Crowned Crane , 2017, mixed media on handmade silk paper, 11 x 10 in., private collection AKI KANO (b. 1974), Starling , 2020, watercolor on paper, 9 x 12 in., 33 Contemporary Gallery (Chicago) CALVIN LAI (b. 1972), Elevated Eating , 2021, oil on canvas and wood panel, 48 x 24 in., Abend Gallery (Denver) KRISTEN SANTUCCI (b. 1970), The Wise One , 2022, oil on copper panel, 7 x 5 in., available through the artist

(CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT) JESSE LANE (b. 1990), Abyss , 2019, colored pencil on Bristol board, 28 x 39 in., private collection (limited-edition prints available through RJD Gallery, Romeo, Michigan) WALTER MATIA (b. 1953), Southfork , 2021, bronze (open edition), 13 x 31 x 8 in., available through the artist REGINA DAVIS (b. 1985), Blue Bliss , 2022, oil on board, 8 x 10 in., available through the artist VERYL GOODNIGHT (b. 1947), The Sage , 2018, bronze (edition of 35), 12 x 5 x 14 in., available through the artist CATHY SHEETER (b. 1979), Just a Hare to the Left , 2021, scratchboard, 16 x 20 in., private collection DALE MARIE MULLER (b. 1972), P erfect Darkness , 2021, graphite on paper, 11 x 17 in., available through the artist

(CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT) SHERYL BOIVIN (b. 1962), Female Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) , 2021, pastel on Pastelmat, 9 x 12 in., available through the artist JAMES MORGAN (b. 1947), Resting Tundra Swans , 2010, oil on linen, 24 x 36 in., private collection BRUCE PIERCE (b. 1961), Heading for Greener Pastures , 2019, oil on canvas, 11 x 14 in., available through the artist DIANNE MUNKITTRICK (b. 1954), Around the Bend , 2022, oil on canvas, 30 x 40 in., available through the artist DUSTIN VAN WECHEL (b. 1974), Making Dinner Plans , 2022, oil on linen, 48 x 24 in., available this September at the Buffalo Bill Art Show & Sale (see page 105)

HISTORIC MASTERS

JOHN KOCHPAINTINGS THAT PUZZLE

To use a baseball analogy, the paintings of John Koch (pronounced “Coke,” 1909–1978) have come down to us with two strikes against them.

First, Koch was a successful portraitist, catering to a wealthy clientele whose commissions helped support his career in fine art. (The publishers Henry Luce and Malcolm Forbes, as well as the composer Richard Rodgers, were among his many sitters.) That shouldn’t be a strike against anyone, but, like it or not, many observers have considered commissioned portraiture an obstacle to “serious” artmaking for more than a century. Why? Because it usually requires artists to please the sitter, while “fine art” obliges them to please only themselves.

Second, we have come to believe that great artists challenge accepted norms. (“Comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable,” as one wit put it.) Monet made the seemingly permanent look transitory; Picasso fractured the spatial plane and disoriented viewers, while Warhol proposed that markers of consumer capitalism had become America’s defining feature. John Koch, on the other hand, depicted his comfortable middle class life in New York City, sometimes while painting a nude professional model, sometimes during a cocktail party that revealed the wondrous view from his upper-floor apartment on Central Park West. The main artistic currents during his heyday were various forms of abstraction, most reflecting the uneasiness of modern life. Western culture was transformed by the 20th century: underlying anxiety is what we came to look for in an artist, not self-satisfaction.

“I think some of the problem with Koch’s works is that they strike people as totally academic, totally well-done but just so old-fashioned,” says Barbara Haskell, curator at New York City’s Whitney Museum of American Art, which owns several paintings by this artist that haven’t seen the light of day in decades, and won’t anytime soon. Ultimately, she concludes, “he doesn’t have any relevance to the contemporary art world.” Robert Fishko, who owns Manhattan’s Forum Gallery and has sold Koch’s work on the secondary market from time to time, offers his verdict: “Koch was a very interesting artist, but he made no single

unique contribution to American art to arouse a great deal of interest.” One might say that artists can defy societal conventions, but not the drift of the art world. “He was just the wrong guy at the wrong place at the wrong time,” adds painter Jacob Collins (b. 1964), who also refers to himself as a “perennial outsider.” Strike two.

Initially I didn’t want to launch this exploration of Koch’s life and art in such negative terms because, in large measure, that is what almost every other writer on him has done (and there aren’t that many to begin with). The last notable exhibition of his art, John Koch: Painting a New York Life, occurred in 2001–02 at the New-York Historical Society, which owns works of art but isn’t really an art museum. Almost all of its catalogue essays begin with descriptions of postwar intellectual ferment and the artists — particularly Pollock and De Kooning — who captured the era’s rebelliousness that Koch seemingly did not share.

Let’s not feel pity for John Koch, however. His paintings of that Manhattan apartment are in the collections of major museums including the Metropolitan, Whitney, Brooklyn, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, and Museum of Fine Arts Boston. At some point, curators at all of these institutions liked his works, even if they almost never get displayed now. One exception: Caroline Gillaspie, assistant curator of American art at the Brooklyn Museum, notes that Koch’s The Sculptor was frequently on view in its American galleries between 2001 and 2016.

Lack of visibility in museums has not eliminated all interest in Koch, however. “We handle works by Koch, perhaps not every season but certainly every other season,” says Caroline Seabolt, head of sales in Christie’s American Art department. “He has a dedicated collector base.” Koch’s drawings, studies, and finished paintings command prices at auction that can be quite high, such as Studio—End of Day (1961, oil, 5 x 5 ft.), which fetched $604,000 at Christie’s in 2005, or Siesta (1962, oil, 30 x 25 in.), which brought $596,075 at Bonhams in 2020. Galleries that sell Koch works on the secondary market find no lack of buyers. “Anything we get of his, we sell very quickly,” says

Katherine Degn, director and partner of New York City’s Kraushaar Galleries, which represented both the artist and his estate from the 1940s through the ’90s.

IS KOCH PULLING OUR LEG?

So, let’s focus on the 1969 oil John Koch Painting Alice Neel in the permanent collection of the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. Feted last year with a well-attended retrospective at the Metropolitan, Neel (1900–1984) was a barrier-breaking New York painter, influenced by the German Expressionists and strongly leftist. She made many portraits, but they were never commissioned. They depicted her family members and friends — including artists Robert Smithson and Andy Warhol, Metropolitan curator Henry Geldzahler, and art historian Linda Nochlin — as well as figures less familiar to the art elite, like labor organizers and black and brown people.

Perhaps her most famous painting is the nude self-portrait (1980) that shows Neel staring at us, her pale, sagging body perched on an upholstered chair. “This is me, now,” she seems to declare. Without explicit references to sex, she also painted out-of-the-closet

gay men and lesbians who stare right back at us. Such images were not sales gold through most of her career, which suddenly took an upward trajectory from the late 1960s as feminists began to celebrate her frank subject matter, expressive handling, and the very fact that a woman artist was challenging viewers in this way.

Koch’s painting of his session with Neel is totally different. We see a large room with stained wood floors; at its far end is Neel, sitting in an armchair, wearing a long, modest dress one might associate with

the Victorian era. Her face is largely obscured by shadows. There is no artificial lighting, and, if there is a window, it is out of view somewhere at left. In the foreground is Koch himself, mostly seen from the back, seated before his easel and reaching for a rag — presumably to wipe his hands or something else — next to a table holding his paints. The room itself is quite bare. A large painting of what looks like a darkened European church interior hangs beyond Neel, and behind the artist is an antique writing desk.

There is an oddness about this painting. The fact that Neel, an artist who exposed things, is dolled up so primly, and that her face is not recognizable in the shadows, suggests that the scene is neither about her nor her relationship with Koch. (In some ways, it is almost a parody of her work.) Koch himself is not much of a presence, other than the fact that

he clearly orchestrated the moment we are viewing. There actually is more clarity devoted to the wall’s wainscoting and the inlaid desk than to the two people here. Perhaps the furnishings that might otherwise belong in what seems to be a living room have been pushed aside so that no paint will drip on them? One might say Koch likes Neel but loves the room, which seems to be the star here.

If this room is relatively bare, other rooms in Koch’s apartment — the staging site of so many pictures — are filled with furniture, most antiques or just old-fashioned. Portrait of Dora in Interior (1957) does include a profile of his wife, Dora, but her face is largely in shadow because the lamplight is behind her; better illuminated are the vases of fresh flowers, and the room is full of interesting elements — a tabletop sculpture, a seascape on the wall, and a shelf holding various objets d’art. Dora herself appears to be just one more object in the room.

The oil Morning, 1971 shows Koch on a stepladder polishing a chandelier’s crystals while his wife, Dora, cleans out the hearth. The room is crammed with loveseats, cane-back chairs, carved desks, framed pictures, and inlaid bookcases holding not books but curios. Mina Weiner, who organized that 2001 exhibition at the New-York Historical Society, says this painting is actually funny because “the people who knew John and Dora knew that they never cleaned.”

In yet another oil portrait of Koch’s apartment, The Movers (1954), two workmen in undershirts strain to lift a large painting; its richly carved wood frame is likely what makes it so heavy. The workmen need to be careful, not only with the painting but with the many antiques all around them. From the side, Dora’s shaded face watches the pair like a hawk, presumably to ensure they don’t scratch anything; perhaps her surveillance is part of the strain they feel. The workmen twist their bodies to support the framed painting; perhaps Koch was channeling the contorted figures in Rodin’s sculptures, in which twists and turns reveal their musculature. Assuming that’s true, this is a painting about the physical weight of art that also references historical art. Like Morning, 1971, it’s funny, but in a different way.

Koch certainly had time to study Rodin sculptures, among the works of many modern and pre-modern masters, during the five years he spent in Paris in the early 1930s, and again after World War II. He had little formal training in art: nine months drawing plaster casts with a private teacher at age 10 in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where he was raised, then a couple of summers taking classes at the Provincetown Art Association on Cape Cod in 1926–27. Fortunately, his parents (his father worked in a furniture store) were generally supportive of their son pursuing his bliss.

Paris was a hotbed of experimentation, but Koch was less interested in visiting artists’ studios and contemporary galleries than in spending time in museums, particularly the Louvre, where the Old Masters were parked. Gregarious by nature, he made friends easily with both French and American people, some of whom commissioned him to paint portraits or other images, which helped him pay his way in what was then a relatively inexpensive place to live.

Koch did try his hand at modernism (“Kandinsky had an effect on me … quite a strong one”), and he once visited Picasso, whom he described as “an enormously charming man, very friendly … [although] I had a very hard time making out exactly what he was saying,” which he attributed to his own “embryonic French.” He also met some Dada and Surrealist painters who tried to pull him into their spheres, but it didn’t really take. Former Manhattan gallerist Gertrude Stein, now 95, knew John and Dora Koch. She recalls that, several years before his death, he suffered a stroke that affected his dominant right side. “Dora tried to get him to paint with his left hand, and he did something that was abstract, but he didn’t like it.”

Koch’s time studying the Old Masters in Europe clearly made him partial to a pre-modern sensibility. In the backgrounds of many paintings, particularly those set in his apartment, are copies he made of museum masterworks; perhaps that blurred seascape in Portrait of Dora in Interior was one such copy, though he did occasionally purchase an actual Old Master painting or sculpture when it fit his budget. In The Cocktail Party (1956), we see two paintings in the background, one by Tiepolo and the other by Vuillard, that Koch described to an interviewer (for the 1963 exhibition John Koch in New York at the Museum of the City of New York) as “my complete fantasy” — the fantasy being that he could actually afford to own such masterpieces.

Koch’s own paintings may remind viewers of figures found in Baroque art, dramatically contorted to reveal musculature and an emotional

state. His undated Telephone Call suggests the influence of Georges de la Tour (1593–1652), with its dramatic lighting provided by an electric lamp rather than a candle. The unexpected ring of a telephone awakening a naked woman might bring to mind Rembrandt’s Danaë (1636, Hermitage). The twisting bodies in Baroque art were intended to heighten the emotional effect of the story being told, usually based on the Bible or classical mythology. In Koch’s scenes, however, the narrative is generally mundane or non-existent because his focus is instead the look of a body in a position that highlights its musculature. Here the modern world is a form of life drawing class. When he returned to the U.S., settling in New York City on the recommendation of an English friend he met in Paris, social realism was all the rage, but “I knew that was not for me,” Koch recalled later. What was for him was a woman he had met and fallen in love with before going to Europe, the pianist and piano teacher Dora Zaslavsky (1904–1987). She was married at that time, but that union was ending when Koch came to New York in 1934, and the pair wed the following year. All reports indicate it was quite a happy marriage. (“Her first husband was a very close friend of mine, and I met her through him,” Koch said. “It worked out very well.”)

Love doesn’t pay the rent, and neither did Koch’s paintings in the depths of the Depression, but Dora earned some money from concert performances and, later, as an instructor. For a couple of years during World War II, Koch taught at the Art Students League, but “portraiture always came to my rescue,” he said: “Certainly of that period, some of the most committed and telling pictures, I think, were portraits.” The parents of some of Dora’s students commissioned him to paint their children’s portraits, paying him $100 or $150, not bad money in the 1930s and ’40s. (An example of Koch’s family portraiture from 1951 is illustrated here.)

In 1939, Kraushaar Galleries began to show and sell Koch’s work, beginning what he called a period of “enormous growth and great happiness.” Many of those paintings were Manhattan cityscapes made as new buildings and bridges were being erected, or they depicted the workmen undertaking these projects. These were not stylized social realist images of the working class whose victory will come. Radical politics was not Koch’s thing; he noted later that “both Dora and I were pretty much fighting the official leftism of the time.” His East River (c. 1930) offers an aestheticized vision of industry in which factory and tugboat smoke blend in a cloudy sky that mirrors the water itself. The workingman “does represent mankind to me in a certain way,” Koch explained in 1968. “I do think that people are beautiful, and I think the image of what they’ve built is beautiful.”

Koch enjoyed getting out of the city from time to time, painting quieter rural life, as seen in Vermont Barns — Neutral Monochromatic Study in Grays (c. 1940); here we view a small town from the other side of a waterway. Nature is great, but this artist’s heart was really with the interactions of city people.

A circle of artist friends began to develop for John and Dora, including Milton Avery, Paul Cadmus, Reginald Marsh, Isabel Bishop, Marsden Hartley, and Raphael and Moses Soyer. Marsh and his wife, Felicia, were particular favorites, and Koch’s 1953 portrait of them is now in the Whitney’s collection. It is not just painters who appear in Koch’s work, but also writers, collectors, and members of genteel society in general. As noted above, Koch would occasionally make paintings

of cocktail parties held in his apartment, combining his portraiture skills with his love of this home and the satisfaction he had with life. He also portrayed the piano lessons his wife gave, views of his studio (with and without models), the daily interactions of a husband and wife, and views over the city from the windows.

There is, as commentators have often noted, something odd about many of Koch’s images. They can seem a sort of puzzle in which viewers try to put the pieces together to uncover the story, somewhat like an amusing Hogarth scene of 18th-century British life. Yet there is nothing particularly funny or moralistic here. Koch frequently shows people not looking at, or speaking to, each other, disconnected or lonely in the midst of others. Or they may be absorbed by the newspaper, or just thinking. The look of the apartment, its tastefulness and air of refinement, steals the show every time. In this way, the paintings are deeply personal, reflecting Koch’s sense of himself as portrayed through the placement of every piece of furniture. The artist willingly makes himself a bit ridiculous through his roles as director, prop master, and choreographer. Even in his own day, this stageset was becoming dated, and it takes a brave person to do that.

SOMETHING ODD

In his numerous artist-in-the-studio paintings, Koch’s models — both male and female — are depicted as points of fascination, sometimes posing but frequently taking a break, returning to who they are. In After the Sitting (1968, private collection), a male model starts putting his clothes back on while the painter continues developing what looks like a theatrical Tiepolo scene of Olympian gods. Presumably, the John Koch in this painting is por-

traying a nude, while the actual John Koch is more interested in the naked model at what is normally an unseen moment.

Koch’s penchant for showing people not interacting can even appear when they are in the same bed: Telephone Call suggests that the woman rising to answer the phone is quite through with the man still asleep beside her. Night (1964) is a post-coital scene of a naked woman on her side seemingly asleep, or aiming to sleep, while the naked man beside her reads a newspaper. Siesta (1962) shows a naked woman fixing her hair while her female partner still sleeps, wrapped in a bed sheet. The tenderest moments appear to reveal how alone and apart people feel: Discussion (1974) features a fully clad man and woman holding drinks and sitting silently across from, but not looking at, one another.

Was-he-or-wasn’t-he speculation about Koch’s sexual preferences has long factored in the interpretation of his paintings of models and of men generally. The Sculptor (1964) is interesting not only for the image itself — a standing nude model, seen from behind, lights the cigarette of the seated male artist, whose face is perilously near the model’s genitals — but also for what appears on the museum’s webpage devoted to the painting. There members of the public can ask questions; two make reference to the model’s buttocks, and one asks if the artist was gay.

Kraushaar’s Katherine Degn takes umbrage at the very question, calling his sexuality “irrelevant,” yet it remains an open question. “He had a longtime marriage to Dora,” curator Mina Weiner says, “although certainly there were rumors about his homosexual longings. He may have been very closeted, not acting out his homosexuality.” Ninety-four-year-old Burton Silverman, a portraitist who was taken under Koch’s wing early in his career and had several of his paintings purchased by the older artist, recalls him as “fey,” noting that Koch “did not talk about his sexuality, keeping it quiet. Maybe he was a 19th-century gay. I never saw anything one way or the other.” Jacob Collins, who didn’t know the artist but likely was influenced by him, says, “I don’t know for a fact that he was gay, but that was my impression.” He adds that the suggestion that Koch was homosexual perhaps is made by “gay activists throwing a lifeline to his reputation,” in effect making him more relevant to our times.

There is a sense of stagecraft in Koch’s art. A question that arises after seeing many of his paintings, particularly those of his Manhattan apartment, is whether he is playing the debonair master of home and studio, wearing tailored suits and showing off his antiques, or if he really is that comical-yet-not-funny person. Burt Silverman claims that Koch really was the former. Perhaps his greatest creation was his lifestyle, depicted so often in his paintings. (When she was organizing the 2001 exhibition, Weiner visited the apartment and found it smaller than it appears in his scenes, as though Koch sought to aggrandize his life.)

The longer we look, the more we wonder, “What is the subject of this painting? What was on the artist’s mind?” Great art may overcome the oddness of an artist’s personality (think Van Gogh), but the fact that Koch’s paintings remain in seemingly permanent storage nationwide reflects their puzzle-like nature, that they do not fit into a category and thus don’t help curators wanting to tell a clear story of American art. Don’t hold your breath that this puzzle will be figured out anytime soon.

THOMAS HART BENTON ARTIST IN THE HEARTLAND

If you’ve never had an opportunity to view the famous murals, drawings, and paintings created by the Regionalist painter Thomas Hart Benton (1889–1975) during his prolific, sevendecade-long career, you’ll surely find some in almost any major U.S. art museum. If, however, you also want to see where Benton conceived and created some of those masterpieces — as well as the books he read, the instruments he played, the environment where he communed with his family and fellow artists, plus many lesser-known drawings, studies, and sculptures — consider visiting the Thomas Hart Benton Home & Studio State Historic Site.

Located in the upper-class Roanoke neighborhood of Kansas City, Missouri, the house and stable-turned-studio were purchased in 1939 by Benton and his wife, Rita, for $6,000 cash. Originally built in 1903 by architect George Mathews, the three-story limestone house encompasses an impressive 7,800 square feet and is surrounded by lush trees and shrubbery. Here Benton spent the last 36 years of his life developing several now-renowned murals, most notably Achelous and Hercules, A Social History of the State of Missouri, Independence & the Opening of the West, and Sources of Country Music, as well as the easel-size paintings Hailstorm, The Year of Peril, Cave Spring, and Lewis & Clark at Eagle Creek. Today the site is one of 55 within the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Historic Artists’ Homes & Studios network.

BECOMING BENTON

Benton was widely admired as a draftsman, painter, muralist, and instructor who — like many long-lived artists — moved through various stages of stylistic experimentation, though he is best remembered as the outspoken, articulate voice of American Regionalism. Along with Grant Wood (1891–1942) and John Steuart Curry (1897–1946) — they were dubbed the Regionalist Triumvirate — Benton pursued both art and activism during the Great Depression, helping to foster a uniquely American brand of realism that was particularly proud of agriculture and manual labor. His depictions of rural life in the South and Midwest championed working-class laborers while eschewing foreign and elitist influences.

One of Benton’s best-known murals, the 10-panel America Today, became a paragon of this ethos and was inspired by a six-month sketching trip he made across the country in 1928. The project was

commissioned by the New School for Social Research in New York City and focused on the distinct personalities and cultural characteristics of each American region, with scenes ranging from farming and religion to industry and urban life. Where Benton shines brightest in this mural, however, is in the closely observed, sensitively portrayed portraits of the varied people who together make America what it is. In all of its scenes, Benton’s message is clear: hard work and a respect for

both the land and the citizenry are what America was founded on and what would, in time, lead the country back to prosperity.

Benton developed such down-home ideals growing up in the small town of Neosho, Missouri. But he was also exposed to a broader worldview from a young age, which he would continue to develop throughout life while traveling and reading. The key to his cosmopolitanism was the fact that his father was a lawyer and U.S. Congressman, who relocated the family to Washington, D.C., for eight years and often took his son along on his travels. Spending his teenage years as a cartoonist for a local newspaper, young Benton eventually convinced his father to allow him to attend the Art Institute of Chicago in 1907; the following year he headed to Paris to study at the Académie Julian and Académie Colarossi.

In 1911 Benton returned to the U.S. and settled in New York City. He began working in the silent-movie studios of New Jersey and teaching at the Chelsea Neighborhood Association. There he met his future wife, Rita Piacenza, an art student from Italy who would become the most pivotal figure in his life. Benton remained in Manhattan for just over 20 years, marrying Rita at the age of 33. His nineyear stint as an influential instructor at the Art Students League of New York (1926–1935) is remembered best via the legacy of Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), who took Benton’s instructional wisdom and antiestablishment philosophy to heart.

COMING HOME

In 1935, aged 46, Benton returned to Missouri to head the painting department at the Kansas City Art Institute, and also to undertake a major mural commission for the Missouri State Capitol. Although he had

spent his early career as a stereotypical starving artist, Benton was returning to his home state as — arguably — America’s most successful, albeit controversial, artist; he had recently become the first artist to have a work (the self-portrait illustrated here) appear on the cover of Time magazine. Over the next 36 years, the Bentons’ Kansas City property evolved not only into a “live/work” space but also a place of business and cultural activity where the couple entertained collectors, fellow creatives, and political figures. “You could make an appointment to come to the house and buy a painting right off the wall,” site administrator Steve Sitton says. “Rita was a sharp businesswoman, but also cautious. If you couldn’t afford a Benton, or if she didn’t know or trust you, you had to buy one of his drawings or one of his students’ works. Once she saw you were serious and not just looking to flip the work, then you could buy a Benton painting. Rita was extremely crucial to Tom’s success, and he freely admitted it. She handled all the behind-the-scenes administration, but he got the glory. We talk about her quite a bit on the tours here, about the instrumental role she played in his career.”

The art collection displayed in the home and studio totals roughly 25 original Bentons: paintings, drawings, and lithographs, as well as three tabletop bronze sculptures. All have been obtained through loan, donation, or purchase. “Although we don’t have any Benton masterpieces,” Sitton notes, “we do have a lot of his studies and preparatory work for murals and larger paintings. And we have several extremely rare works you wouldn’t necessarily associate with Benton: some of his early student pieces, still life paintings, paintings of the far West, and large abstractions from both very early and late in his career. One of the most interesting items is a satin tablecloth he painted for his mother when he was 22, with a Matisse-like design. These works help us see the entire arc of Benton’s career and some of those searching and experimental stages. He was pigeonholed into Regionalism, but there is far more to him than that.”

Here visitors also find evidence of other artistic pursuits Benton explored during his life — what Sitton calls “the sides of him

you might not have otherwise known.” A gifted storyteller and writer, Benton penned two autobiographies and kept a library well stocked with books that clearly influenced him. Music was another passion, particularly folk and country, so it’s appropriate that two harmonicas, a baby grand piano, and a collection of sheet music remain in the home. Sitton explains: