13 minute read

LMDh preview

The LMDh cars were on track at Daytona in December in final preparation for the opening round of the WeatherTech series. Racecar was there to see how they got on

Advertisement

The LMDh category has been a long time in gestation but it’s fi nally here, and ready for competition debut at the 24 Hours of Daytona at the end of January. The cars had a fi nal group test at Daytona early in December and, although each of the manufacturers that were present, including Cadillac, Acura, Porsche and BMW, had car-stopping problems, the teams set about fi xing them in test conditions, rather than a race weekend and go into the fi rst race with some optimism after a challenging year.

This test was the fi rst time teams had sight of the new tyres from Michelin that will be used next year, and was supposed to be a performance test to help organisers with the Balance of Performance for the 24-hour race. However, failures of the motor generator unit (MGH) and other electrical issues, along with dramas at customs shipping new parts in, prevented much meaningful running. Following the test, teams were more concerned with making their cars run cleanly than worrying about the obvious lack of grip on cold tyres fresh out of the pits, or even what their rivals were doing.

Acura ahead

Offi cial times were not available from the testing, but from data available to teams it appears the Acura was fastest, at 1m35.75s, Cadillac narrowly behind at 1m35.80, Porsche 1m35.90 and BMW 1m36.35s. The cars were at similar pace over long runs, too.

Just to re-cap, the cars are based on chassis provided from a choice of four manufacturers: Dallara provides the base car for BMW and Cadillac, the Italian fi rm continuing its relationship with the latter that started in the DPi era of prototype racing. ORECA supplies the chassis for the Acura, again a long-standing relationship that has won big races and titles. Porsche opted for Multimatic, which was supposed to produce cars for the other VAG manufacturers, Audi and Bentley. Audi confi rmed its participation but then backed out shortly before switching its allegiance to Formula 1 for 2026, while Bentley’s bid to take over the Audis was rejected by Bentley’s board in October 2022.

As none of the chassis builders are allowed to exclusively supply one manufacturer, their products are all commercially available. Lamborghini will come in 2024 with a Ligier chassis, Alpine with ORECA, while McLaren is scheduled to arrive in 2025 and is expected to choose either Dallara or Multimatic.

The manufacturers provide the engines and aero kits. This means the cars are all very diff erent looking, with brand styling cues readily apparent in each one. They are powered by a variety of engines and only Acura has produced a brand new power unit.

Honda Performance Development, based in California, produced its 2.4-litre, twin-turbo V6 from scratch, and the company says it has very little in common with the proposed IndyCar engine that first ran in 2021, but which was dramatically dropped by IndyCar in the same week the Daytona test took place.

Power units

BMW opted for its old 4.0-litre, naturallyaspirated V8 taken from the DTM and which first raced in 2011, while Porsche went even older on its design, taking the 3.4-litre naturally-aspirated V8 from its RS Spyder that first ran in 2005, and was later used in the 918 Spyder road car.

The last power unit is that of Cadillac, which has taken over the design of its 5.5-litre V8 in house, where previously it had been prepared by ECR Engines in North Carolina.

The cars run with a spec hybrid system comprising the MGU from Bosch, battery from Williams Advanced Engineering and gearbox from Xtrac. This is designed to supplement the power from the engines, replacing the demand on the ICE with that of the electronic unit instead.

Power is limited to 500kW from either the ICE or the combination of ICE and hybrid, with deployment strategies open for the teams to choose how they want to use it.

Electronics are all supplied by Bosch, including telemetry, scrutineering harnesses and the safety systems, unlike in the DPi era when the choice of provider was open.

Teams are free to write their own software, as the ECU is not regulated, and it is up to the manufacturers to ensure the ECU is integrated into the operation of the hybrid system. This has not been easy – much of the testing and the subsequent failures have involved the demands made by the ECU on the hybrid system, which has been blamed for many days of lost track time.

The LMDh cars are performance balanced and, to help the organisers achieve parity, the cars must hit a point on the lift / drag graph in all conditions, including different ride heights and wing angles. Weight and power are also strictly regulated. Power is no longer measured by output from the engine, instead torque sensors have been introduced to monitor power at the wheels, which will make the balancing more accurate.

Minimum weights have been mandated for overall car (1030kg), as well as such items as the engine (180kg). Similarly, the location of the engine is closely monitored, which helps the chassis manufacturers design their cars to accept different engines, including in the future the new LMP2 power unit.

Tyres come from Michelin, who will provide the same rubber as in the FIA World Endurance Championship. At the Daytona race, due to the cold overnight temperatures,

The BMW uses a Dallara chassis and a naturally-aspirated, 4.0-litre engine from the German company’s DTM programme

This is the first year IMSA will have hybrids, so the learning curve is steep. Shown here the Wayne Taylor Racing Acura

The Porsche 963 suffered with a gearchange issue early on but managed to fix that and put in some longer runs on day two

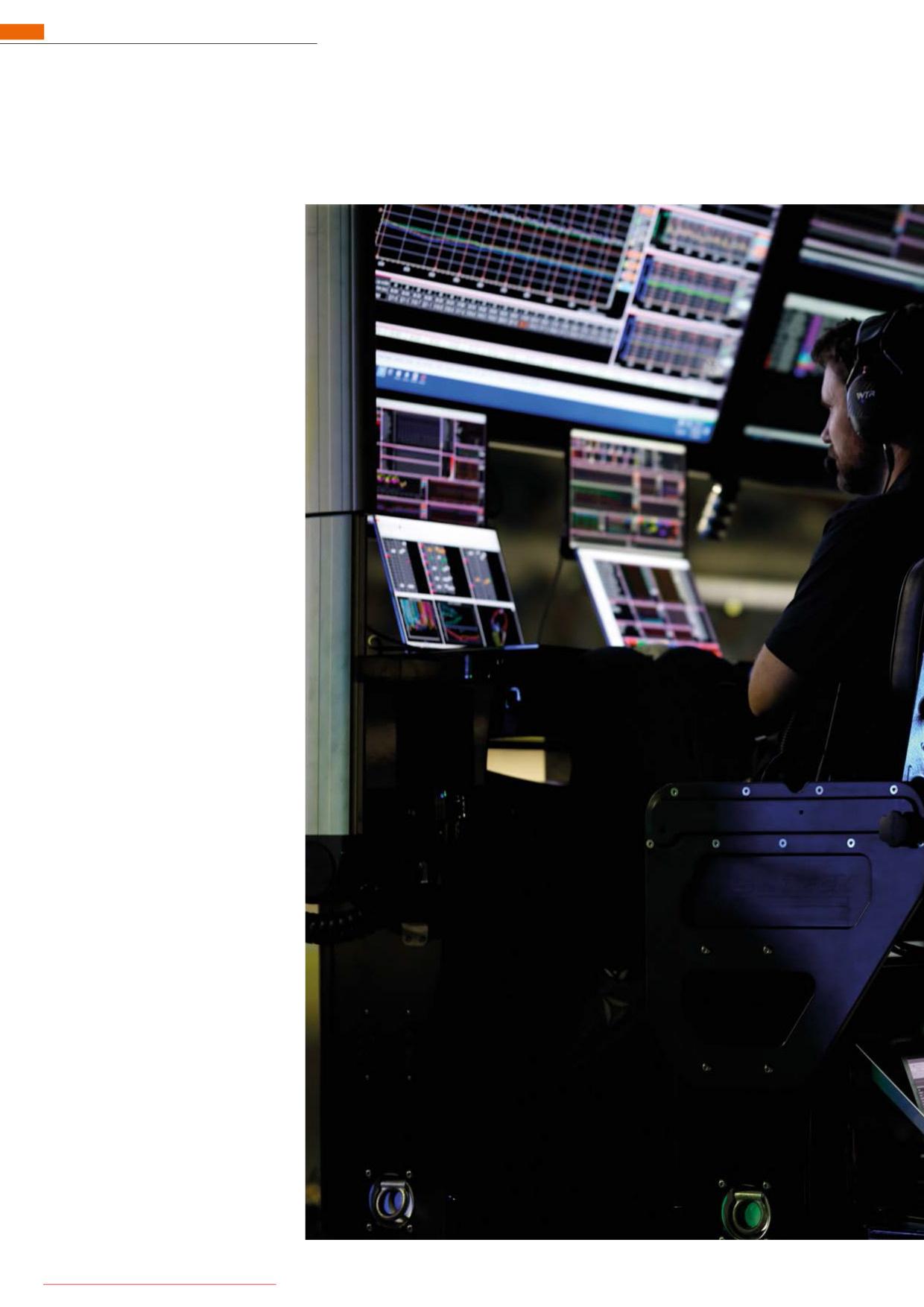

Bosch, Williams and Xtrac engineers were all on site for the Daytona test

a choice of two compounds will be available to teams, although IMSA has yet to determine whether the softer compound will be available for the whole race or just a 12-hour window overnight.

For the remainder of the season, Michelin will bring only one spec of tyre to each race, and it will be up to the tyre manufacturer to decide which will be available to teams on any given weekend. In contrast, in the FIA WEC Michelin will provide the choice of rubber for every race and teams will be free to use each compound as they choose.

Energy limits

A further change for next year is the way the sanctioning body, IMSA, deals with the energy used by each of the cars per stint. Reminiscent of the old Equivalence of Technology rule set, the body is considering limiting the energy per stint available for each car. The idea is to reduce the impact of the different choices of engine, and to retain the element of strategy. Teams will still benefit from fuel saving as they look towards the end of the race and that crucial final pit stop. This is a marked change from looking purely at fuel consumption and balancing that using different size tanks and fuel hoses.

Testing has proven to be challenging and, although each of the manufacturers claim to have racked up high mileage, all have experienced problems of one sort or another. Early testing has been hampered by a shortage of materials, and therefore components, from core suppliers as demand on such items as electronics and carbon are high due to the war in Ukraine.

According to reports from the teams, each session has been punctuated with red flags as an LMDh car has been towed back to the pits after a mechanical breakdown. The Daytona test was no different.

Teams, and crucially the suppliers, are now under huge pressure to get everything right for the biggest test of them all – a 24-hour race to kick the season off in cold overnight temperatures, followed by a 12-hour race at Sebring in March.

New rubber

Early testing saw the teams use the old 29/34 tyres from the 2022 Hypercars, but the Daytona test provided a first glimpse of the all-new 2023 tyre from Michelin that has a higher bio-content than the previous generation rubber.

The shape, construction and compound will be the same across the LMDh cars in both IMSA and the FIA WEC, as well as the Ferrari and Toyota Hypercars, while for the Peugeot, which is allowed to run the same size tyre all round, the fronts will be stretched and the backs squashed to fit the needs of the predominantly front-biased car.

Although the teams’ pre-test run plans focused on performance testing, much of the session times were used fixing niggling issues that prevented cars from extended running. None were able to complete a full stint length on track, for example, let alone a double stint. BMW and Cadillac both brought brand new chassis for their roll out, but both spent the first day in the garage waiting for their Bosch scrutineering harnesses to clear customs. They were denied permission to run without the system by the sanctioning body.

Porsche suffered a gearchange issue on the first day, having installed new components into the system, but managed to start its longer runs on the second day.

Acura has developed a complex antilag and traction control system for its turbocharged engine that sounded like a mechanical bag of nails as the car negotiated slow-speed corners. The teams confirmed codes were being re-written to help, but it took nearly two days before any meaningful running was achieved, meaning any performance testing only occurred on the afternoon of the second day.

Michael Shank’s Acura broke an MGU on the second day of testing and was unable to complete any significant running. The team was so concerned with its lack of track time that it has scheduled another test early in January, while the Wayne Taylor Racing car suffered a split header tank, though this was quickly rectified. Taylor’s team will not take part in the early January test, preferring to work towards the 24-hour race.

Despite time wasted waiting for its Bosch harness to clear customs, Cadillac put in some decent testing, including evening work

The MGU on Shank Racing’s Acura broke on day two, halting the team’s testing. It has since scheduled a January test to make up time

Complex drive

Throughout the Daytona test, the teams were reporting how complicated these cars are to work on. One driver commented that the controls were not integrated with each other and that, if one change was made, others have to be made in sequence to complete the process.

‘It is the most mentally draining car I have ever had to drive,’ said BMW driver, Augusto Farfus, while manufacturers confirmed it will take some time and running before customer drivers will be able to operate these cars.

For other professionals, though, the complications were not a drama. ‘The car is a completely different animal to the LMP2 cars Sébastien Bourdais in the Cadillac. The electronic systems are all integrated but controlled separately and can easily stop the car

Close-up view of the BMW front suspension (and Porsche, right) Porsche worked hard on set up and got to long runs on the second day of testing

I drove last year. It’s far more complicated, but to me it’s logical,’ said WTR driver, Louis Delétraz. ‘Yes, one thing leads to another, but I am comfortable doing that.’

However comfortable some drivers may be, having the systems operating separately means the teams have to hire technologically-literate professional drivers until new programmes can be written to make controlling these complex cars a more straightforward process.

The test was supposed to be one of performance running, with many teams believing they had got on top of the reliability issues that have plagued these cars from the start, but the electronics appear to be an issue, specifically getting the different elements of the system to talk to each other.

Simulated balance

Another consequence of the lack of meaningful fast running was IMSA did not have the opportunity to accurately correlate its simulation data on track, something it needs for the performance balancing to take place. The technical team at IMSA was confident it will get the process right as its simulation is so advanced, and says it has a good handle on what the cars are capable of, but this was the first time the cars ran on the new tyres, and the last time they will run on the Daytona track before the race week.

The BoP tables will therefore be largely based on simulation, and IMSA and the FIA and ACO are working closely together to align their approach.

In the past, the FIA’s BoP has affected the GTE-Pro class and changes have been applied retrospectively. For example, an FIA performance balancing change would rely on a prescribed number of green flag laps of the previous two races before being applied to the next race. However, that does not account for the nature of the circuit on which the change will be applied.

IMSA’s approach has been different, and more proactive. The body started to predict the Balance of Performance for its cars on the next circuit based on experience of DPi cars. However, without that option available, it has turned to simulation experts for help.

The lack of meaningful fast running… [means] the BoP tables will therefore be largely based on simulation, and IMSA and the FIA and ACO are working closely together to align their approach

The final chance

The cars will run at Daytona at the pre-race test, the so-called Roar before the 24, one weekend before the start of the 24-hour race . That’s normally considered a fine-tuning test, and it will be too late then to make any major changes. But with teams still busy making their cars run reliably, and worrying about how their new tyres will work on a low-grip surface, it could be different this year.

Certainly standing at the International Horseshoe, it was clear that even in moderate ambient temperatures the first laps out of the pits on new tyres (unheated in IMSA for many years) are going to be difficult for the drivers. Even the front end seems to be hunting, while the option of running a lower ride height would appear to be out, judging by the sparks coming from under the Cadillacs as they passed the pits on the second afternoon while the drivers waited for pressures to rise.

Last word goes to Connor de Phillippi, driver of the BMW Hybrid V8: ‘Especially this year with where everybody is in development, I think just focusing on your own [programme] and not getting sucked into the competitive aspect, especially early in the race. It’s going to be about keeping it all together and performing at the end when it actually matters.’