iThink 2023

iThink 2023

On our individual quests in life to find our more about our unique characters, our contributors have come together to discuss the question, 'Who Am I'? Being a broad question, it has encouraged every person to think deeply about the significance within their own lives and how they find meaning from their surrounding environment. Our edition, in its very nature, reflects the unique nature of humanity, and consequently, responds to a range of questions from a myriad of angles.

We would like to thank every contributor for the time and effort that they have put in their articles to inspire all our readers and stimulate further ideas and discussions. And finally, we are eternally grateful for Mrs Beresford-Miller and her guidance throughout the production of this edition. We are very thankful to have been given the opportunity in our final year to give back to the Trinity community which we have learned from and inspired us.

Amy Clarke, Alfie Edwards, David Aisa Miller

Abi Watkins

Catherine Lanaspre

Oscar Clarke

Jay Trinder

Olly German

Cessie Hall-Eade

Aayan Ratnayaka

Alex Martin

Cover Art : Noah Gilham

The

Abi Watkins

Psycholgical-Continuity

Catherine Lanaspre

Philosophy,

David Aisa Miller

The

Ayann Ratnayaka

Autism

Jay Trinder

Maturity

Alex

Oscar

Japanese

Amy Clarke

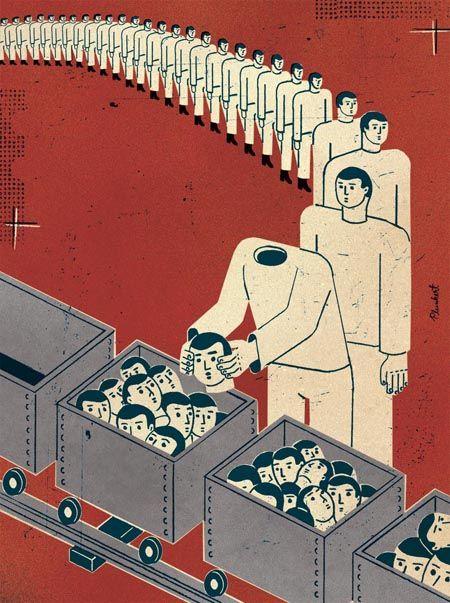

Humanstendtobelievethattheirexperienceisuniqueinsomewayorother,andthismay partiallybetrue;thereisnobodythatgrewupinthesameplacewiththesamejobandthe same hobbies. However, this is not enough to consider them to be truly unique. Every personisamemberofanumberofgroups,andtheymightbeuniqueinthatthereisnobody whoisapartofallthesamegroupsasthem–thereisnobodyelseintheirsegmentofthe Venndiagramofpeople.Butthismeansthatpeopleareonlyuniqueinthewaythatthey eachchoosetoconform.

grandma trend, showing evidence of a collective effort to hop on the new trend early,andtolivetheidealshowninvideos. Similarly,TikTokandPinterestthrivefrom suggesting and appealing to (mainly feminine) aesthetics such as the ‘it girl’ aesthetics, and others which include not only guides on clothes to wear but also hobbiestotakeupandideologiestoliveby. People become compelled to fit themselves intooneofthedistinctaestheticsbybuying clothes and altering their lifestyle. While fewpeopleachievethisthereisevidenceof attemptsandinclinations.

As Robert Smith put it, ‘everybody’s happy; they’re finally all the same. ’

Carl Jung’s ideas about the archetypes of the collective unconscious (certain charactertypesandideasfoundrepeatedly

in stories of historically and geographically unrelated cultures) caused him to conclude thattheremustbesomepartofourbiological psychology that makes these archetypes so prevalent.

However,thereisanothergroupthathas always existed in some form, that criticises these aesthetics, and in this criticism, they appeal to another aesthetic, defined by their (often misogynistic when considering the modern aesthetics) desire to be different. There is no way to truly break away from these aesthetics, because the denial of aesthetics is an aesthetic in itself. In other words, the desire to break away from the collectivewillalwaysbeacollectivedesire.

Often, people will express a wish to break away from the mainstream, but this only happens when the current trend involves breaking the norm. Some examples of this are the hippie movement in the 1960s, and the emergence of punk in the 1970s. These bothdemonstratetheyouthofthedaytrying tomoveawayfromoppressivenormalityand mainstream, but are only as a result of the zeitgeist being of rebellion and disruption: eachindividualstillactsinaccordancewith

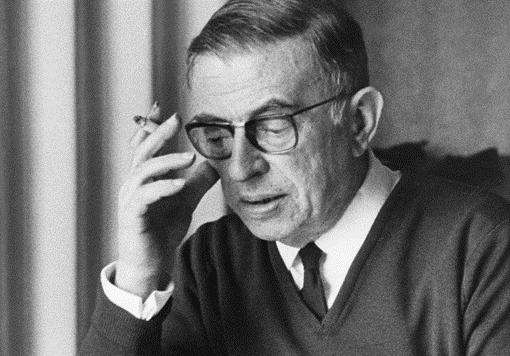

the masses. This is not a break away from the mainstream, it is simply an interpretation of the ideology represented in the group that each individual has subscribed to. Jean-Paul Sartre thought that there is no reason that things are the way that they are, so there is no reason why they should remain that way. This means that we are totally free to change everything. He believed that not living according to yourself would compromise your fulfilment and happiness, so we should not live under an authority. Instead, we need to live authentically. However, by accepting Sartre’s existentialism, you are subscribing to an authority that tells you to live authentically, but the fact that a person might follow existentialist ideas or consider themselves an existentialist contradicts the very essence of existentialism. Sartre encouraged people to live authentically but by following this encouragement they are not living authentically; they are living according to Sartre’s authority, but by not following it theyarestillnotlivingauthentically.This creates a kind of paradox where it is impossibletomakeadecisionthatistruly authenticorunique.

In knowing that our motivations and desires are never truly unique, we can only describe our individuality in terms of the groupsthatweareapartof,theideaofthe self falling in the intersection of these groups. This describes us in terms of the masses; it is a description that allows us to find our place in the masses rather than describing us in terms of ourselves. It is a shallower version of individuality than an individuality of ambitions and motives, because it describes us in terms of our physical place in the world. The individualitycomesfromthefactthatthere can physically only be one person in that space, so a person is only unique in that regard.

Therefore, the answer to the question of ‘WhoamI’is:thesameaseveryoneelse,in everymeaningfulway.However,thelackof individuality is not necessarily a negative thing. A lot of television and literature are made to be relatable, and appeal to many people. Total individuality would disable human connection and disallow empathy. However, attempts at and belief in individualityarestillnecessary,becausethis iswhatinspiresmotivation.Toachieve,we must believe that we are able to do what others cannot. It is for this reason that everybody needs to believe the lie of individuality.

Psychological-continuity theory was first proposedbyJohnLockeinthe17thcentury.

Locke’s initial theory argued that memory and consciousness determine personal identity over time: ‘ a thinking intelligent Being...canconsideritselfasitself,thesame thinking thing in different times and places.’ Over time the theory evolved to includeothermentalfeaturese.g.character.

The modern theory is now based on two concepts: psychological connectedness and continuity. This essay will discuss various strengths and weaknesses of the modern version of the theory and will ultimately argue that psychological continuity is only part of personal identity and that no one thing can be used to determine whether a personpersistsovertime.

The modern version of the theory centres around two concepts: psychological connectedness and psychological continuity.

Psychological connectedness refers to the causal relation between previous psychologicalstates,andone'scurrentstate, e.g.atanearliertime,Ihadtheintentionof going to school and, because of this intention,Iamcurrentlywalkingtoschool. It claims that personal identity over time relies on a causal dependence between a person ’searlierpsychologicalstateandtheir current psychological state. Psychological continuity is the sharing of mental states, e.g., having the same memories, goals, and disposition at different times - the sharing of these mental states is due to psychologicalconnectedness.These

concepts seem reasonable when defining personal identity. Often when judging whether two people are the same we consider whether they share mental features, e.g. they have the same memories and character traits as the last time we saw them.Equally,psychologicalconnectedness seems reasonable because of the general principlesofcausality:athingislargelyhow itiscurrentlybecauseofhowitwasbefore.

However, what is unclear is how psychologically continuous I have to be with an earlier version of myself to still be the same person. Real-life scenarios highlight an arbitrariness to this decision. For example, after Phineas Gage’s accident in 1848, where a metal rod was driven into his brain, many of his colleagues thought that he was no longer the same person despite his memories being intact; additionally, people often consider those with dementia still to be the same person despite dramatic memory loss. This lack of definitivenesssuggeststhatpsychological

continuity is not a concrete way of determiningpersonalidentity.

Another problem is that the psychologicalcontinuity view reaches some odd conclusions.Onesuchconclusionisthatit suggests that the original person still exists if someone who is entirely physically different from them shares their mental features. In the 1980s, Derek Parfit introduced a thought experiment where a personistransportedfromEarthtoMarsby tele-transporter which transports them by destroyingtheiroriginalbodyonearthand creating a perfect replica on Mars. According to the psychological-continuity theory, the replica is no different from the originalasitiscontinuouswiththeoriginal, thus the original person still exists. This argument is unconvincing, because, while the replica is psychologically continuous with the original person, it seems that the replica’spsychologyonlytakesonthetraits and memories of the original person rather than being caused by the original’s psychology. This means that, while the replica will experience a constant flow of consciousness that has continued from the originalperson’sconsciousness,theoriginal person ’sflowofconsciousnesshasstopped; and surely if the original person ’ s flow of consciousness has stopped then they no longerexist.

The difference between being caused by and taking on traits and memories etc. suggests that psychological continuity does not account for everything. It also seems that the only way for a person ’ s current psychology to be caused by their earlier psychology is through brain processes and so perhaps the psychological continuity theory does not recognise the role of the brain in affecting psychology and personal persistence. Therefore, let us consider a combined theory: a neural-andpsychological-continuity theory. Combining these two aspects, however, does not alleviate all the flaws of the psychological-continuity theory: the psychological criterion remains poorly defined and arbitrary, and introducing the brain criterion does little apart from differentiatingbetweenoriginalandreplica (this does not add much to the theory –especially as cloning remains science fiction). When assessing real-life cases where there have been both psychological and neuroanatomical changes, there are no clear solutions. In Phineas Gage’s case, there were both significant mental and physicalchangesandsoitwasdecidedthat he was no longer the same person, but in a case where there were smaller changes in brainstructureandpsychologye.g.theloss of synaptic connections in a demented person ’sbrain,arethepsychologicalor

neuroanatomical changes then significant enough to say that they are no longer the sameperson?

The failure of all theories of personal identity to provide definitive answers perhaps suggests that identity is, in fact, an arbitraryconceptthatsimplyinvolvessome vague physical and psychological conditions. David Hume’s view was that personal identity is not something that exists independently of perception and experience. The self instead is a collection of different factors that are constantly changing.Ultimately,thisviewappearsthe mostconvincingasitaddressesthefactthat therearecaseswhereitisunclearwhethera person should still be considered the same persone.g.adementedpersonoraclone.

However, it also undermines the concept of personal identity and replaces it with a more unclear and flexible idea that does not provide any conclusive answers to the tricky problems of personal identity.

Inconclusion,thepsychological-continuity theory is important in highlighting what people usually judge as important in personal identity, however, it fails to providethewholepictureand,alone,raises severalproblems.Firstly,thereisnoprecise point where a person is considered so psychologically discontinuous with the earlierpersonthattheyaredefinitivelysaid to be a different person. Secondly, it does notdifferentiatethedifferencebetweenthe originalandthereplicaandhowsharingthe same memories and being psychologically continuous does not mean that is the same person. And after considering a combined neural-psychological theory, the most convincing option is that there is no factor thatdecisivelydeterminespersonalidentity.

David Aisa Miller (Upper

Identity is defined as the qualities, beliefs, personality traits, appearance, and expressions that characterize a person or group. Whilst this description is thorough, it is essential to acknowledge that these contributing factors are undoubtedly influenced by other factors. Studying RS andGeographyhashighlightedmanyways in which they are influenced; however, the most fascinating and compelling are the concepts of free will and globalisation. In my opinion, these two theories clearly demonstrate that both Philosophy and Geography greatly influence our identify because, as social sciences, each subject uniquelyexplainshowtheworldaroundus determineswhoweare.

Firstly,thetheoryoffreewill,akeyconcern within Philosophy, is important to our identitybecauseifwearenotfree,itcanbe

arguedthatweareunabletoknowwhowe are as we lack the freedom to truly express our identity. It is first important to understand what free will is, as this will directly determine whether we have it or not.Itisdefinedasthepowerandcapacity for humans to make decisions independently to any prior event. Fundamentallyforonetobefreetheymust befreeofanyexploitationormanipulation. Examples within society which demonstrate that we are not free include: excessive government intervention, limitations created by society which are simply illusions, and social constructs unconsciously luring us into behaving a certainway.Jean-JacquesRousseau,bornin Genevain1712andoneofthe18thcentury's most important political thinkers, focussed onthisrelationshipbetweenhumansociety and the individual. His early work argued thatthedevelopmentofcivilisationledtoa decrease in happiness due to a lack of freedom. His book ‘The Social Contract’ begins with “Man is born free, and he is everywhere in chains”, explaining that people could only experience true freedom if they lived in a civil society that ensured the rights and well-being of its citizens. Rousseau's theories of sovereignty and law directly influenced French revolutionaries, such as Robespierre, contributing to the ideas that would lead eventually to the French Revolution. ‘The Social Contract’ emphasisestheneedforindividualstoplay aresponsiblepartinacivilsocietyinreturn fortheinsuranceoftheirliberty.

Todaythisneedisstillnotfulfilledinmany societies. Ultimately, there is plentiful of evidencetosuggestthatourfreewillhas

been comprised to the extent that our identity is in danger of becoming simply a socialconstruct,showingthatPhilosophyis indeedagreatinfluence.

Whilst Philosophy and free will are certainly relevant, globalisation, a pillar of Geography, is also important to discuss with reference to our identity as it determines how places and people are perceived. Globalisation is defined as the increasing connections between places and people across the planet, established through trade, politics, and cultural exchanges, aided by technology and communication. This theory has changed theidentityofmanycountries,regionsand even individual people. To some extent it can be argued that globalisation has rendered individual identity impossible or implausible as the process of homogenisation creates a single global culture which is engrossed by all. It occurs as the popular (normally western) beliefs, businesses, traditions, and more are promoted instead of lesser-known ideas, leading to a reduction in cultural diversity. Theories such as McDonaldization and Americanization are good examples of culture amalgamating and resulting in global homogenisation. With reference to the identity of a place, this makes it harder to be unique as everywhere becomes so similarthatnooneplacestandsout.

Onespecificaspectofglobalculturewhich haschangedsignificantlyisthemake-upof oureconomies.Globalisationhasledtothe creation of ‘Clone Towns’ which is where the High Street or other major shopping areas of a town are significantly dominated by chain stores. This is likely to be caused bytwocombiningfactors.Firstly,thereisa higher demand for TNCs (Trans-National Corporations)astheirglobalbrandsappeal to a wider audience. Secondly, they have more economic power so they can afford andthriveofthecompetitionunlikesmaller businesses which are only comprised of a single families' wealth. This demonstrates that,toacertainextent,globalisation,along with TNCs have eroded local culture and identity, validating that Geography is assuredlyacriticalinfluence.

In conclusion, both Philosophy and Geography through their respective theories, significantly influence our identity. Whilst Philosophy is more metaethical, Geography highlights the tangiblefactors,whichiswhyIthinkthatit is marginally more relevant and important. However, it should be remembered that, although we can agree on a common meaningforwhatidentityis,atitscoreitisa subjectivetermsothefactorsthatinfluence it reflect the uniqueness of an individual. Ultimately, as Marx highlighted “Philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways, the point, however, istochangeit.”Therefore,ifouridentityis truly something we perceive as a valuable, weshouldactnowtosustainitsprotection.

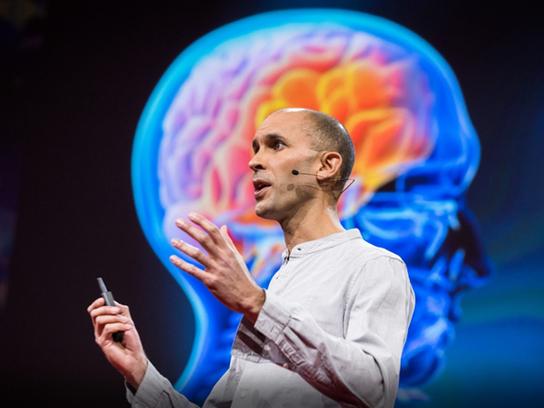

The question of who we are (neurologically speaking) is something scientists and people have wondered for many years and a large number of theories have come out about who we are. Some of these come out of neuroscience,someoutofreligionandsome arejustideasputforwardbypeople.

An example of a religious perspective on who we are comes out of Buddhism. Many Buddhists believe in the idea of ‘no-self’ (anatta), that actually we are simply sensations,feelings,andthoughts.Although The Buddha himself did not say this, when hewasaskedthequestionifthereisaself,he did not answer. It is said that The Buddha’s teachingon anatta wassimplyanattemptto getridof‘clinging’whichispartofsuffering. Although this view has effectively no empirical evidence to support it, it still provides an interesting way to think about whoyouare.Buddhismasawholeseemslike averyrelaxingandcalmwaytoliveyourlife, but if we question if it actually provides an answer to who we are, it seems clear to me thattheanswerisno.

One area highlighted recently is the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) which is located in the prefrontal cortex (the ‘front’ part of the brain) which when injured/impaired leads to an impaired senseof identity and who we are. The vmPFC is the ‘lower’ part of the medial prefrontalcortex,anditispossiblethatthis partofthebrainmakesa‘model’ofwhowe areand‘places’itindifferentplaces.

Modernscience(includingneuroscience, cognitiveneuroscienceandpsychology) hastheviewthateverythinghappensin ourbrainandisdowntocomplex neurologicalprocesses(neuronsfiringand differentareasofthebrainworking togetherinawaythatwearestilltryingto figureout).

Another area highlighted is the medial prefrontal cortex, which is where the vmPFC is located. Using functional magneticresonanceimaging(fMRIscans),a techniquewhichutilisesthehaemodynamic responsewhichisthechangeinbloodflow thatoccurswhenanactivityhappens,andit detectsthisandlocatesit.Thesescanshave recently shown that the medial prefrontal cortex has an increased flow of blood to it (thisbloodisnecessaryasitcarriesoxygen) when we think about memories of ourselves, suggesting that this part of the brain is also prominent in how our brain perceives us. The other part of the medial prefrontal cortex is the dorsal medial prefrontalcortexandwhenwethinkabout ourselves,itdistinguishesusfromothers.

This is very common and actually has a name which is the self-reference effect (SRE),thisistheideathatourbrainrecalls memoriesofourselvesbetterthanofothers.

This self-reference effect has been used to evaluate memories of ourselves. A study was carried out by Stendardi et al (2021) from where seven people who had brain lesions (damage to brain tissue) in the vmPFC(allmalewithanaverageageof57) were compared to eight people who had injuries to other parts of the brain (control group - seven male, one female with an averageageof61)and23peoplewhodidnot havebraininjuries(controlgroup-21males, two females with an average of 57). This allowed the researchers to draw a causal conclusionastowhetherthevmPFCaffects SRE

Participants were given a list of 45 negative adjectives and 45 positive adjectives and asked to name a few that described themselves in the present and a few to describe themselves in 10 years.

They were also asked to do the same thing for a famous celebrity named Gerry Scotti (he was used because he is Italian as this studyoccurredinItalyandbecauseheisof asimilaragetotheparticipants).Whatwas foundisthattheparticipantsinthecontrol groups were able to recall more adjectives for themselves than the celebrity after a periodoftimeforboththepresentandin10 years. However, the participants with damage to the vmPFC had more or less no abilitytorecallthewordsaboutthemselves in either category. This suggested to the researchers that the vmPFC has a central roleinself-identity.

A key case study is that of Phineas Gage, a railworkerontheAmericanRailroadinthe 19th century. In an accident, an iron rod went through his frontal lobe which is where the prefrontal cortex is, he most certainly had damage to his brain tissue whichwouldbewheretheprefrontalcortex is located. He miraculously survived (although he did lose an eye) but what is fascinatingaboutthiscasestudyisthatafter the accident he was said to be ‘ no longer Gage’. His personality was completely altered,anditwasasifhewasnotthesame person before and after the accident. This once again suggests to psychologists that it istheprefrontalcortexandtheareaswithin it that are vital to our self-identity in the brain.

To move away from specific parts of the brain,weshouldlookatmodelsofoursense of self. One of the more recent models of self-identity comes from Georg Northoff, a psychiatrist who suggests that our sense of self is a ‘nested hierarchy’. He suggests a three-layered structure of our sense of self which supports the idea that our sense of self comes from many areas of the brain working together in perfect unison. These threelayersare:theinteroceptivelayer,the proprio-exteroceptive layer and the mental layer.

Today thisneedisstillnotfulfilledinmany societies. Ultimately, there is plentiful of evidence to suggest that our free will has been comprised to the extent that our identity is in danger of becoming simply a socialconstruct,showingthatPhilosophyis indeedagreatinfluence.

Hismodelsuggeststhatprocessesthatoccur inthebraindependonotherfunctionsand vice versa, in other words, they all work together to provide a coherent model of personal identity. John Locke, a British philosopher,andphysicianwhosubscribed totheempiricalwayofthinking(useofthe sense rather than reason) argues that personalidentityiscausedby‘psychological continuity’ and that personal identity is basedonconsciousnesscausedbymemory. He suggests that we are born tabula rasa (blankslate),thismeansthatweareshaped byourexperiencesandtheenvironmentwe live in (this is named the behaviourist approach and actually is far more complicated but that is the gist of it); these memories are what creates the personal identity in the brain. Similarly, another empiricist philosopher David Hume suggests that personal identity is related to episodicmemories(atermcoinedbyEndel Tulving, a cognitive neuroscientist who livedanddiedwellafterHumelived)which are memories of experiences/events. These memories directly influence our personal identity.

Inconclusion,itiscleartomethat,through my research, personal identity is caused by multipleareasofthebrainworkingtogether in unison. Whether it is the vmPFC tying together our present and future selves or if we are a nested hierarchy. All of these theories suggest many parts of the brain working together in perfect unison to give usaclearindicationofwhoweare.

“The identity that we ascribe to things is only a fictitious one, established by the mind, not a peculiar nature belonging to what we ' re talking about.”

DAVID HUME

Despite all these ideas being different, they all have one thing in common which is that they all suggest that personal identity in the brain is caused by multiple parts of our brain working together.

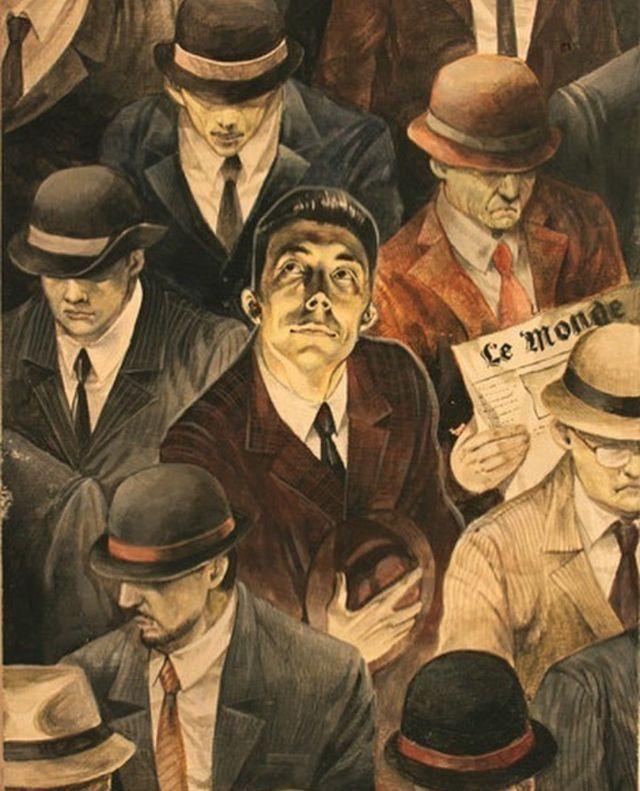

‘Who am I?’ is a difficult question for anyonetodefinitivelyanswer.Considering thereexistmultiplesubjectivedefinitionsof ‘the self’, a single answer is nigh on impossible. In a psychological context, ‘the self’isdefinedbyWilliamJamesas‘Me’and ‘I’.AccordingtoJames,theformerrefersto the self as an object of experience, whilst thelatteristhesubjectofexperience.Thisis a distinctly linear view of the self, which is understandable considering the psychological context, but is, nevertheless, misguided.Itis,inmyopinion,pointlessto attempt to understand the self in a linear way, as one ’ s conception of the self is a spectrum, and the spectrum is far from linear.

It took me 15 years to attempt to explore whoIwas,and17tobegintounderstandit whenIwasofficiallydiagnosedwithautism. This diagnosis gave me both closure and a strange sense of claustrophobia. It proved that there was an empirical, systematic, almostnumericalexplanationforthenature ofmyexistencethatwasmorecomplicated

than “that’s just Jay”. It made me overwhelmingly aware that I was being perceived. It also made me realise how muchIhadbeenavoidingthatfactoverthe last decade. Autism affects various key aspects of daily life: from processing ability to diet, there’s even a correlation between autismandhypermobilityofjoints;butthe mostpublicised‘adverseeffect’ofautismis the confusion surrounding social cues. In my experience, this manifested itself in my becoming so afraid of being perceived as ‘wrong’ for something I cannot control (such as my voice, the way I walk or my ‘special interest’) that I unconsciously adopted traits from others based on the level of social acceptance they achieved. According to Michael Fitzgerald, language is used as a means of ‘masking’ by autistic people, to avoid accidentally offending. Fitzgerald also noted that “older persons with autism can have a marvelous sense of verbal humour and playing on words”, often without realizing the positive effects oftheirlanguage.

Language,therefore,canbeusedby autisticpeopletoalterthe‘self’thatthey presenttotheoutwardsocialworldinto amodelthattheydeemtobesocially acceptable.

Autism can also affect the way a person acquires traits over time in such a way that their sense of self is obscured. Autistic children, for example, will often regularly impersonateacharacterfromtheirfavourite cartoon, or impersonate a particularly prominent adult in their life. Whilst this is true of most children of around age 5-7, autistic children and people continue to, often accidentally, mimic people. In Liane Holliday’sautobiography'PretendingToBe Normal', she describes mimicking the actionsandreactionsofthosearoundherto thepointofmentallyrecordingandcopying “the way they used their eyes ” and “how [those around her] would open them wide when they spoke loud and animated: and equallyhow“[thosearoundher]wouldcast [their eyes] downwards if they were speaking quietly or slowly”. This mimicry, whilst theoretically ensuring social acceptance,alsoresultsinanobscuredsense of self due to the constant nature of masking.

It is sometimes impossible for autis peopletotelliftheirthoughts,actions,an reactions are their own or the performan of a culmination of characters they a subconsciously forced to play. Hegel not in his Phenomenology of Spirit, that a ‘ se consciousness’, a desire for recognitio from others, is held within every hum psyche,leadingtoanaturalsocialhierarch He asserts that there are some who des recognition more than others in order gain a positive sense of self. There are al otherswhogivethatrecognitionmoreth theydesireit-thesecharactersbecomet authorityfiguresinsociety.

The desire for recognition to distinguish between ‘self’ and ‘other’ exists, according toHegel,innatelyandnecessarily,primarily to establish the border between what is ‘yourself’ and what is ‘other’. Autism blurs that line, not only to the point at which whatis‘yourself’becomesindistinguishable from what is ‘other’, but also that ‘the self’ exists as an abstract, separate entity - a culmination of ‘others’, often to the point thatonecannotrecognisewhatisone’sown and what is another learned (or, one could say, stolen) trait. Perhaps, however, this is why autistic people tend to harbour a strongersenseofemotionalawarenessthan

Self-consciousness is “desire itself” and can only find “satisfaction” in other consciousnesses

'allistic people' – we are aware that there is no “just” about any person – since every emotional trait has an explanation and a root. When one traces the root of an emotion,itmakesthingsdecidedlyeasierto explain or, if necessary, combat. Autism, however,remainsanon-linearspectrum,as does‘selfhood’.Thereis,tome,noneedto attempttotracea‘root’ofautism,asautism isnotsomethingthatneedstobeeradicated or changed. The autistic spectrum, along

Alex Martin (3rd Year Essay Prize Winner)

The theme of making peace with the establishment is one which has been long debated. However before delving deeper into this statement, it is first necessary to define and analyse what is meant by the termsofthisdebate.Firstly,wemustdefine “the establishment”. In the sense of this essay,theestablishmentisboththepolitical party/systemthatgovernsthecountry,and also the status quo of other social conventions. This would include aspects such as policing, as well as slightly more trivial things like queuing and general manners.Thesecondtermwhichrequiresa definition is the idea of “making peace ” withthisestablishment.Makingpeacewith the establishment does not mean that one has to agree with every aspect of the establishment or status quo, only that one understandswhythesesystemsareinplace and respects them without making a nuisance of oneself. The final term requiring definition is maturity. In this context,maturityistheabilityforsomeone to react and respond to a situation in a suitable and appropriate way. This may involvenotalwaysreactinghowonewould liketo,inordertokeepthepeaceandallow better relations with others or more progresslong-term.

Making peace with the establishment is something that many people have done, andtherearemanygoodreasonsforit.Iwill begin this section by demonstrating some areas where it is almost certainly appropriateforonetomakepeacewithand accept the status quo as it is. Manners and respect are important aspects of life as well as many cultures. It is widely observed and settleduponthatyoungerchildrenwillnot havethesamelevelsofmannerandrespect for others that would be expected of an adult. This is due to their brains and cognitive abilities being at a different stage of progression when compared to older, moredevelopedandmorematureadults.It would seem wholly absurd for someone to reject these types of common manners on account of a supposed rejection of the status quo. These types of social standards further the development of society as a whole – which ultimately returns to and benefits you – and they also promote a healthier society with better relations betweenall.

The previous example relates primarily to social standards and conventions, but the more political establishment can also be broughtintothis.Policingisacontroversial topic, with many different views on how it shouldbeimplemented,orevenifitshould beinexistenceatall.Whateveryourviews on it, most would agree that if you were to be pulled over by the police, you would oblige. Even if you believe that the police force should be abolished, it would be irresponsibletoflee–especiallyifitisjusta standardtrafficstop.Fleeingwouldresultin moreresourcesandenergybeingwasted

and would not ultimately gain you anything Maturity in this scenario would be recognsing the bigger picture and understanding that you fleeing is ultimately pointless and immature as you would be risking lives of not only yourself and the police, but also those of the general public This would make a decision to flee or resist arrest immature, showing that the mature option in this scenario would be to simply make peace with the establishment and the way that it functions

Being stopped by the police is a hindrance and can impact your day, especially if in a rush. However, these negatives do not justify defying the establishment. Being in a fight with the establishment is not advantageous for you, nor for anyone else. Governments in most countries have established lines of contact for citizens, so that their concerns can be voiced in a way which is advantageous to all Surely it is far better to use these methods of communication to further the development and progression of all, and to improve the workings of the establishment, than to be at war with it, defying it and working against it Working against the establishment will only result in negative outcomes for you, as you would be defying a system and machine which has been designed to work as effectively as possible It would be foolish and immature to think that a single person as such a small opposition could ever hope to combat the mighty establishment On the contrary it is far more mature to recognise your personal insignificance in the grand scheme of things, and to take decisions accordingly This view of believing that oneself is more important than others is childish, and an important aspect of true maturity is coming to terms with the reality of your own insignificance. Although the machine

is not perfect, fighting it in such a rebellious manner will only result in it destroying you, perhaps through no fault of its own, as this is simply how it has been designed

Despite the arguments and points that have just been raised, there are also numerous counterarguments There have been numerous instances in history where people have campaigned viciously and completely rejected the status quo and current system in order to provoke change. In many of these instances, using routes of communication with the government wouldn’t be sufficient One of the key examples of this is the suffragettes and similar campaigns. These types of campaigns are fighting severe problems, and many would argue that the rights that they were fighting for far outweigh the issues associated with being at war with the establishment It could even be argued that their way of fighting these issues was more mature, as they recognised that simply raising their issues would not be sufficient to cause adequate change, and thus chose more appropriate and effective action – which resulted in a success.

“Protest beyond the law is not a departure from democracy; it is absolutely essential to it.”

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.

Maturity requires careful consideration of outcomes, and given that seems to have taken place in these types of instances, it clearlysuggeststhatmakingpeacewiththe establishmentmaynotalways,ifeverbean importantaspectofmaturity.Furthertothe previous point, many establishments worldwide are severely corrupt and mismanaged.Thismeansthatanyeffortsto raiseconcernsoveracertainmatterthrough established routes would likely be ineffectiveandpointless.Again,itcouldbe arguedthatmaturityisrecognisingthisand alteringyouractionappropriately.

Overall, this question is a complicated and intricateone,onewhichisalsohardtosum up in so few words. There are many other factors,whichwhenanalysedbringupmore difficult questions regarding maturity, and alsothecurrentstateofhumanexistence–andwhetherwearejustcogsinamachine.

Overall, with regard to the points raised in this essay, it appears that the answer to the essay question is still somewhat shrouded. In my personal judgement, with regard to theoriginalessaystatement,theanswerhas todependonthesituationandcause.Itoo recognise that my view is ultimately insignificant, however I feel many would agree that certain causes (like that of the suffragettes) require more robust and industrial action that will have a drastic change.However,forthemostpart,people should make peace with the establishment, andcertainlyfortheeverydayperson,asitis averyimportantpartofmaturity.

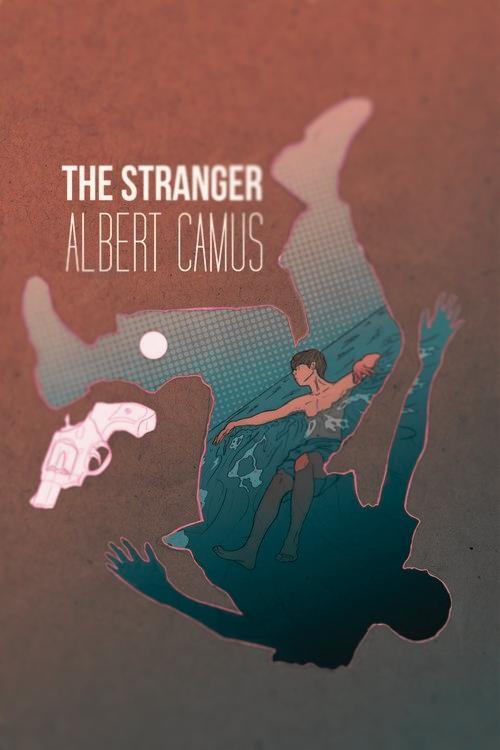

“IOpenedMyselftoTheGentle

WhoamI?’.Thequestioneverypersonhas toreconcilethemselveswith.Weexploreit as a child, jumping from one disparate career path to another before lunch, defining ourselves by our future work becausethatiswhatwearetoldistheendof life – many people never grow out of this mindset.Asateenager,wegrapplewithour wider place in social mechanisms and hierarchies, posturing to be at the top of one ’ s own social microcosm – school. An increase in critical thinking brings about a newfound self-perception, almost universallythisisnotapleasantexperience, akin to looking in the mirror and seeing some Kafkaesque cockroach staring back. We begin to recognise; our peers, our mentors, our parents, are all deeply flawed, this being generalisable to the wider world engulfing us – including to ourselves. Existential dread typifies many a teenage experience–mineownincluded,butnowI canpretentiouslyquoteCamusatthedrop of a hat, so some pyrrhic victories at least. As I lose my teenaged title and prepare for thenextcrown,Iamremindedofjusthow heavytheheadthatwearsitis,20isatruly terrifying, but completely silent and arbitrary prospect. The cusp of adulthood has however repromoted my quest to answer – who am I? This metaphysical journey, from capitalist hamster running placidlyonitswheeltoexistentialedgelord, has led me to one conclusion – this is not therightquestiontoask.

Itistheobviousquestion,andIamnotnow goingtospoutsomeclichélike“whodoyou wanttobe?”,insteadIamgoingtorejectthe whole premise of this Socratic search. We, allofus,cannotbedistilledtoonething.

“You will never live if you are looking for the meaning of life.”

Wedonothavesomecorewithinoutbrain, containing some root of ‘ us ’ , there is no maximwhichouractionsaredefinedby,no one philosophy which grounds us. A human is but the aggregation of personal experience,builtnotfromthegroundupby oneself,butbyamyriadoflinearlystacking external influences, so incalculably large that the search for a root ‘identity’ is going to result in nothing but existential dread –‘angst’asKeirkaguardtermedit–aswetry and fail to succinctly define ourselves. It is not so surprising that people define themselves by their job or some other categorisation, be that; sexuality, race, politics, religion etc. For this is an easy escape,ratherthanaddressingtheissuesof ‘meaninglessness’, not only within the universebutinourownpsyche,wecanfind ourdoor,likeRoseandJack,toclingto.Just like the Titanic, so too has our concept of the ‘I’ sunk. Camus argued that religion is philosophicalsuicideforthisreason,itisan evasion of the problem at hand –meaninglessness – Camus called it the ‘absurd’.Itmightbealifeboat,butnotone whichwilltakeustoshore.Weequally

should not let ourselves sink below the water to cold decay, this is equally an evasion of the problem. The human condition, and its search for simple definitions. Neat boxes. Tidy solutions. Willalwaysfailwhenaddressingourselves, for we really are just that complicated. Life is just that complicated. There is no black and white, only a dizzying array of kaleidoscopic colours. But mostly it’s just a boring grey – as a Londoner, one sympathises.

I have so far been thoroughly unhelpful. Not answering a question is perhaps the forte of a philosophy student, but the political scientist in me craves a semigeneralisedanswer.Tome,wehavearrived atthemostexcitingpointanyonecanreach in their self-discovery, the point at which one gets to self-define. Where ‘I’, as an individual, and as part of a greater whole, gettoask,‘howdoIwanttolive.’Lifeisnot asomethingwecanlookatandaskholistic questionsof,‘whoamI?’willyieldnothing, for my answer changes at every given moment, life is a process. We cannot jump totheconclusionwithnopremisestobuild on,andsowecannotjumptoajudgmentof ourselvesbeforeweareourselves.Theonly questionswecanaskandanswer,arethose regarding the process. ‘How’, not ‘who’ or ‘why’. So ask yourself dear reader, how do youwanttoliveyourlife?

Define yourself by your approach to life; the feelings you want to maximise, the philosophies you want to satisfy, how you want other people to talk about you.

Self-definitionismoreactionthanthought, we are not some disembodied brain, that is nothowtheworldperceivesus,butinstead asactorswhocanhaveimpactontheworld around us. So perhaps defining oneself by workmakessense,butnotexclusively,we

havetotakeamoreholisticapproachtoour personhood which is constantly redefined, ifweallowourselvestostagnatewebeginto lose our humanity, relying more and more on one corporate source for purpose and validation.Lifeitselfisapurposiveprocess, thepursuitoflivingcaninitselfbeourend. Your life is yours to live, so live it. Do not wasteyourtimetryingtoworkoutwhatitis about. The answer is always the same: nothing.

“Are we to look at cherry blossoms only in full bloom, at the moon only when it is cloudless?”, Buddhist Monk Yoshida Kenkō asks one to consider. Our society demands perfection as the beauty standard, creating impossible targets which consequent extreme dissatisfaction,depression,anxiety,andadistortedimageoftheself.Wabi-SabiisaJapanese aestheticphilosophywhichfocusesontheprincipleofacceptingtransienceandbeautythat is imperfect or incomplete. ‘Wabi’ is defined by elegance in simplicity, and ‘Sabi’ is characterised by embracing imperfection. The philosophy teaches us to escape a chasm of despair and discontent within ourselves and embrace the ultimate imperfection of our existence,muchlikehowCamus’absurdismasksustoriseabovetheabsurditywithinour seeminglymeaninglesslives.

The 15th Century ruling class within Japan loved to display their vast amounts of wealth and they drank tea from ornate Chinese cups at the time of full moon.

Murata Shukō, a monk, strove to simplify this celebration, changing its meaning to embrace the transient nature of existence, usingsimplecupsanddrinkingatapartial moon.Thishistoricaldevelopmentofwabisabi embraced asymmetry, simplicity and theimperfectnatureofourselves,havinga moreminimalisticapproach.

“The most precious thing in life is its uncertainty.”

YOSHIDA KENKŌ

Wabi-sabi emerged from the practices and teachings of Buddhism. Within Buddhism, there are “Three Marks of Existence” (in Japanese it is called ‘sanboin’). The teachings of sanboin are Dukkha (suffering), Anatta (no fixed sense of self owing to constant change), and Anicca (impermanence). In Buddhism, Annica, or impermanence,teachesusthateverything in life is changing, nothing remains the same.ThisechoestheGreekhistorian Heraclituswhocommentsthat "Noman

everstepsinthesamerivertwice,forit'snot thesameriverandhe'snotthesameman", astheworld,andeverythingwithinit,exists inaconstantstateofflux.Aseverythingis impermanent, we cannot expect perfection to exist within our lives, we constantly evolveaspeople,andwecannotremainthe exact same person as we did the preceding day.

Our lives have no absolute objective standardswhichwemustliveupto.Dōgen, the founder of the Sōtō school of Zen Buddhism highlights that “One must be deeply aware of the impermanence of the world”. We simply exist and cannot attribute moral values to aesthetics. Oscar Wilde's ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’ separates moral from aesthetic value, “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all”. Ethics and aesthetics must be kept separate as no perfection can be found within our lives henceitisunrealistictocreatestandardsto judgeandperformthevaluationofaperson by.

The Wabi aesthetic favours imperfection. Tea master Sen no Rikyū was dissatisfied with people’s attitudes towards perfection, “In the small (tea) room, it is desirable for every utensil to be less than adequate. Therearethosewhodislikeapiecewhenit is even slightly damaged; such an attitude shows a complete lack of comprehension.” Yet this must not be confused with the more brutal philosophy of ascetism as instead it promotes moderation in wabi ceremonies.“Evenwhenfacedwithfailure, onedoesnotbroodoverinjustice”,

proclaims Hirota in the Zencharoku (the ZenTeaRecord),beautystandardsmustbe rejected as beauty doesn’t have to entail

Japanese architecture reflects the teachings of Wabi-Sabi. The traditional Japanese tea house has a highly simple structure which evokes a sense of sublime and awe attributed to its minimalistic style. Out of thewall,aspaceisremoved,negatingfrom the room in order for light to seep inside and create an opening from the void. Subtracting, and creating imperfection, to let the light through and embrace the beauty brought about through austere imperfection.Reflectinguponourselves,we can apply this principle of Wabi-Sabi to overcome the negative imaging and standardswhichthemediaprojectuponus.

Existing with the lack of objective principles,standardsarenothingbutsocial, theyareimminentnottransientandinnate. They arise from the capitalist consumerist drive to maximise product revenue. As Theodore Adorno criticised in ‘The Culture Industry’, art is standardised and commodifiedowingtomassculture,which is pervasive within our society, suffocating individualityandrejectingnon-conforming beauty. Japanese aesthetics, influenced by the Buddhist idea of impermanence, nothing lasts forever, argue that it is imperfection that must be valued. This is convincing in the inherent absence of objectivevalues,rejectingprojectedsocietal values of the self which we must conform to,andembracingindividualityatthehand of unattainable perfection. Buddhism teachesthatattachmenttodesireleadsto

to Dukkha, suffering. This inner turmoil caused by elusive societal mechanisms of exploitation only leads to unhappiness, hencewemustacceptthesubjectivenature ofbeauty,andembracethiswhenreflecting inwardsuponourselves.

Japanese aesthetics promote an awareness ofourfundamentalexistentialconditionof existence, that our lives are immanent and limited. This should lead to a sense of appreciation of current circumstances, rather than causing grounds for nihilistic anguish,revilinginthelackofself-purpose and meaning. Kenkō in ‘Essays and Idleness’providescomfortintheinsecurity that “It does not matter how young or strongyoumaybe,thehourofdeathcomes soonerthanyouexpect”,asthephilosophy of Wabi-Sabi can change our mindsets to appreciationratherthandespair.

“Mono no aware ” or “the Pathos of Things” put simply means having “ an empathy towards things”, or “ a sensitivity to ephemera”.

The phrase emphasises having an awareness of the impermanent and transient nature of things and a ‘gentle sadness’ when they perish. Confucianism, known as Ruism or Ru classism, is a philosophical tradition or philosophy of ancientChinaandithasevidentinfluences upon the Japanese Wabi-Sabi tradition whenitwasintroducedin3rdCenturyAD. It maintains that human beings are fundamentallygoodinnature,andtheycan find perfection through practicing selfcultivation, as promoted through mono no aware. Japanese director Yasujirō Ozu incorporated mono no aware into Japanese filminthe1970s,withacharactersaying“Ii tenki desu ne?” (いい天気ですね), “Fine weather,isn’tit”afteraprofoundsocietalor familialeventandagainstabackdropofan evolvingJapan.Ozuactedtoevokeasense

of awareness to the nature of our lives, which must be recognised and embraced rather than overlooked or creating unhappiness. This teaching was explored byKenkōwhoremarkedifwewere“never tovanishlikethesmokeoverToribeyama(a fictional film location), how things would lose their power to move us! The most preciousthinginlifeisitsuncertainty”.We must accept and celebrate this impermanence of the nature of our beings toenableustoleadafulfilledandcontented life.

“Man first of all exists, encounters himself, surges up in the worldand defines himself afterwards"

JEAN-PAUL SARTRE

The philosophy of Wabi-Sabi has direct correlations with existentialism, a philosophy which emphasises an individual’s liberty to determine their lives and meaning through their acts, selfactualisationinanintrinsicallymeaningless world. Jean-Paul Sartre, a notable French existentialist philosopher, proclaimed his thesis “that man first of all exists, encountershimself,surgesupintheworldand defines himself afterwards.” Existentialism was expressed in Postmodernist Japanese authors, particularly in post-war Japan. Haruki Murakami, a quintessential existentialist author, adopts existentialist thought into thelivesofhischaractersastheyattemptto embrace the anguish in post-war Japan. Murakami focuses on the themes of loss, and childhood trauma, concluding that in perseverance we can find meaning and happiness amongst the chaos, echoing the existential thesis that our purpose within life is what we make for ourselves. In example, Murakami’s character of Toru Okadain‘TheWind-upBird’reflects

principlesofSartreanexistentialismasToru is a free individual creating his own selfessence in the absence of a meaningful existence.Thenovelconveysajourneyofa man searching for his lost cat, followed by his search for his wife, concluding with Torufindinghisessence.

Camus Absurdism has evident parallels to mono no aware, having an awareness of impermanence and rising about this. “One must imagine Sisyphus happy”, Camus denotesin‘TheMythofSisyphus’,wemust rise above the absurd nature of our lives. Absurdismfocusesontheconflictbetween the meaningless of human lives and the human desire for meaning, yet in recognisingtheinherentlackofmeaning,it does not prevent a person from finding their own subjective purpose. Wabi-Sabi similarly promotes the embracing of impermanence within our lives and rising aboutthistonotdescendintounhappiness.

From the Japanese philosophy of WabiSabi, one can take away the embracement and rejoicing of the imperfection of ourselvesandourhumannature.Wemust escape the despair caused through societal projections of standards which aspire to objectivevalueswhichinherentlycannot exist. Our impermanent nature should not be a means for nihilistic despair, but our awareness of the nature of our existence should instead teach us to rise above the absurd and find beauty and essence in the elusive.

Everythingthatyouhaveeverdonehasled uptothismoment.Everypostureyousitin, the way you keep your gaze in a conversation,thewayyoudrinkfromyour water bottle. One of the problems that existentialism poses is that the thinkers we associatewiththephilosophy,wouldnever themselvesclaimtobeexistentialists.Sartre centres his ideas around atheistic existentialism, the belief that there is no God and that in its place there must be some sort of being to make our lives purposeful. We are those beings, and although there are factors that humans claimtakesawayfromtheirautonomy,(for instance, ethical theories that we follow or being influenced to act similarly to those around you) we must ultimately take full responsibility for everything that we do. Those standards must be met if not to fall into ‘bad faith’, the act of taking responsibility away from your autonomy andapplyingittoexteriorinfluencesonthe mind’s capability. While Nietzsche is associated most notably with the philosophy of nihilism, he himself takes note of the idea that the human creativity maygiveuselementsofthefreedomSartre isreferencing.Nietzschemaynotbehinting attheradicalfreedomasSartre,andhedoes theorise that we are most certainly bound byoursociety,butarguablytheoneofthe

few differences between existentialism and Nietzsche’s philosophy is his slight pessimism towards the human condition. As to living in ‘bad faith’, Sartre gives the example of a waiter, who acts and speaks like a waiter. He is the perfect waiter and encompasses all things that waiters should be. However, Sartre explains these actions byclaimingthatheisonlyactingintheway inwhichhebelieveswaitersshouldact.The waiter, Sartre concludes, is living in ‘bad faith’- as his autonomy is being blocked by some sort of guidance outside his own consciousness.

“Existence precedes essence "" JEAN-PAUL SARTRE

The next of Sartre’s maxims is quoted by many as the key principle in existentialism in the 20th Century. ‘Existence precedes essence ’ outlines how, in Sartre’s own words, there is nothing true about what it means to be you until you start making decisionsinyourlife.Hethinksthathuman traits, attitudes, and characters are built on the decisions we conscientiously make. Until we do this, we cannot truly reach authentichumanity.

Another of Sartre’s maxims, ‘Like it or not, we are free’ asserts how freedom is what makes one a subject rather than an object.

Kant separates the world of physics and metaphysics,andwasconcernedwithmoral freedom, human subjectivity, and the human psyche. It may be that Sartre may have founded the influence for separating subjectsandobjectsfromKant-althoughin the mid-20th Century, metaphysics had begun to ‘go out of fashion’ in terms of philosophical thought. Instead, Sartre reformulates these concerns in a way that would be more accessible to the contemporary world- which is where his atheistic approach to existentialism is founded. Unlike Kant, he believed that societyhasmadeupGodinordertorelieve the burden of decision making. If you can latch onto something apparently certain, such as the 10 Commandments, then you inevitably avoid the individual reflection that is required to yourself decide whether killing, stealing, or committing adultery is actually wrong. In the same way, psychoanalysis serves largely the same function as religious belief does. It allows you to attribute your behaviour, your feelings, and your connection to the world to your childhood and your early experiences.Thedeterministicoutlookthis givesyouonyourownlifeallowsyouto

take responsibility away from the choices that you make. According to Sartre, both religious belief and psychoanalysis allows you to deceive yourself and unconsciously submit your autonomy away to exterior forces on the human mind. Only when livingin‘goodfaith’willwebeabletotake fullownershipofourhumanity.

Many people are aware of the popular thought experiment that asks: if a tree falls in a forest, but there is no one around to hear it fall, does it make a sound? This was posited by George Berkeley, an Irish philosopher known for his development of subjective idealism, or immaterialism. This is a form of monism that rejects dualism, butalsorejectsmaterialism,asitclaimsthat materialobjectsinthemselvesdonotexist, but rather exist contingently in their perception via sensory experience. For this reason, subjective idealism is said to be an extreme form of empiricism. Berkeley is known to have coined the term, ' esse est percipi', or ‘to be is to be perceived’, meaning that existence relies on conscious awareness. However, this opens up debate when we question what, or who, needs to be perceiving something in order for it to exist.

“To be is to be perceived” "Esse est percipi"

GEORGE BERKELEY

Thus, to answer the above question, one couldsuggestthatabugmayperceiveatree falling, and so it falls. But to Bishop Berkeley, no bugs are needed since God is able to perceive everything all at once, meaningthatallobjects,eventsandpeople are ‘real’ since they are being perceived by God. However, if we were to remove God from this theory and take it one step further, we could argue that other people only exist through our perception, such as behaviours that we can see, or expressions thatwecanhear.

Therefore, one could conclude that scepticism towards the existence of other bodies and even other minds is justified. Is itsoimpossibletobelievethattheyceaseto exist when they are not being perceived? When this idea is reduced down to one single‘existing’thing(mymind)thatexists, asIknowthatmymindisthe‘perceiver’in question, it begins to sound like Cartesian Dualism. However, where Cartesian Dualism arrives at the conclusion that cogitoergosum,or‘IthinkthereforeIam’, subjective idealism does not necessarily make the assumption that the doubting mindexplainsmaterialreality.Infact,using thelogicofextremeimmaterialism,thereis nothing to suggest that I am not merely a singular floating mind, with all my experiences and sense perceptions a result ofsomesimulationorbrilliantimagination.

This extreme form of subjective idealism is known as solipsism, an idea that seems to make sense, yet ultimately fails logically and pragmatically.

To me, this idea of solipsism is initially attractive. It seems plausible that nothing beyondasingleindividualmindisrealand everything it experiences comes from within.Thisconcepthasevenmadeitsway intofilmandtelevision,withmediasuchas

The Matrix, Mulholland Drive, and Black Mirror arguably exploring ideas that could be considered in line with solipsism. Furthermore, most criticisms of the theory can be easily refuted by blaming faulty perceptionoranincredibleimagination.

However, beyond a mere ‘what if?’, the theoryismeaningless,regardlessofwhether it makes logical sense or not. It is primarily untestable, meaning that it fails the criteria of both Ayer’s Verification Principle and Popper’s Falsification. Such extreme metaphysical talk is inconclusive and does not meet the standard of meaningful conversation for these philosophers. However,bytheirlogic:art,culture,music, and morality are all nonsense too, so how credible are these thinkers really in determining what makes meaningful discussion?

Stepping back into the theory of solipsism itself, rather than discussing whether it is actuallyworthtalkingaboutornot,wecan placeintoquestionthelogicalcoherenceof this argument from the perspective of Wittgenstein, and his theory of ‘Language Games’. At a glance, Wittgenstein posits that language exists within lebensforms, or ‘forms of life’ that provide subjective meaning for language. For this reason, language must be shared, and thus there is no such thing as a private language. When appliedtoanyargumentthatpositsone

singular mind being the only thing in existence, the argument faces a major problem:inordertoformanargument,one requires the language to do so, as well as argumentative reasoning that inherently comes from language, such as syllogisms that follow a universal linguistic structure. However,inordertoformthelanguagefor the argument that no other mind or thing exists, there must first exist another entity with which that language is shared. This is obviously paradoxical, and seems to bring down the argument for solipsism, but only fromaWittgensteinianperspective.

Overall, however, the rejection of material existence and of other minds seems as if it could be the truth, and solipsism is ultimately quite an interesting theory to muse on. However, due to its untestable nature and its inability to be falsified, the theorycannotreallygoanywhereandoffers noguidanceormeaningforone’slife,sois typicallyrejected.People’sunwillingnessto adoptsuchanegocentricideaisevident,as some have even used the term ‘solipsism syndrome’ to describe dissociative and delusional characteristics in individuals who believe that everything around them exists only in their mind. It is clear to see that, on the whole, subjective idealism and thesolipsismthatdevelopedasaresultofit, are not healthy ways of understanding the world, however much truth such theories mayhold.

In 1689, John Locke published his Essay ConcerningHumanUnderstanding.Inthe chapter entitled Of Identity and Diversity, Locke proposes his theory of personal identity, a theory that formed the basis of theWesternunderstandingoftheself.The theory posits that the self is derived from psychological continuity, meaning that ‘I’ am merely a single stream of conscious experiences. In the 20th Century, phenomenalists formed what is now called the argument from illusion, claiming that our conscious experiences are so often delusive that they simply cannot be comprised of direct perceptions of material things. Modern advances in the field of neurophenomenology are beginning to show a scientific basis for this argument, aiming to demonstrate that our experience of ‘reality’ is a hallucination. Such phenomenalist theories have profound implicationsfortheLockeanself,as,if‘I’am my conscious experiences, yet these experiences are illusory fabrications, then my conscious existence too is illusory. Thus,inthisessayIshallarguethattheself, as it is understood by exponents of the psychologicalcontinuityview,isanillusion. However, this is not to say that we cannot experience selfhood, rather, that what we areconsciousofisnotourrealself.

“If you think of perception as prediction then it becomes natural to think that the self is not the thing that does the perceiving. The self is a perception.”

ANIL SETH

Heraclitus famously stated that “ no man ever steps in the same river twice, for it is not the same river and he is not the same man ” . Whilst it is undoubtedly true that our physical bodies and the physical world are always changing, I object to the suggestionthatIcannotbethesamemanas I was yesterday. Instead, the very fact that today,ashasbeenthecaseeverydayforthe last 17 years, my friends, family, and teachers still call me ‘Alfie’ would imply that at least some parts of me, namely my fundamental identity and selfhood, have remained constant. In his essay Personal Identity, Derek Parfit argues that, were my brain to be cut in half and placed in the heads of two new bodies, assuming that both halves retained the same memories and function, ‘I’ would survive as two new people. This argument draws on Locke’s theory of psychological continuity as Parfit is proposing that, via this operation, the stream of consciousness that constitutes ‘ me’isbeingsplitintotwonewstreamsthat arestill‘me’astheyshareacommonsource. Therefore, if one accepts the psychological continuity theory, it is clear that one possesses an identity which appears separatetothephysicalbody.

Atthispointitiscrucialtodiscussthe

discuss the substance dualists’ theory of selfhood,andhowmystancediffersfromit.

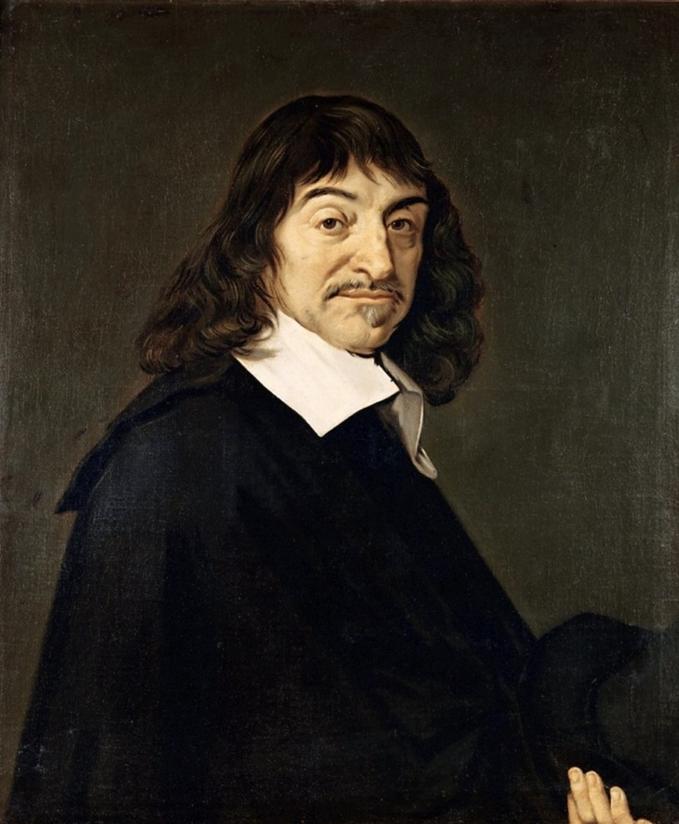

In his Meditations on First Philosophy, René Descartes draws on Plato’s ideas of substancedualismtoconcludethatwe,our conscious selves, are merely res cogitans (thinking things) - an immaterial mind, separate from the physical body. Whilst Descartes’ theory successfully accounts for the self’s continuity through the changing physical world, it is erroneous as, by virtue of writing in the 17th Century, Descartes does not understand that the mind can be seen as a construct caused by purely physical processes in the brain. Thus, my view comes from a position of hard physicalismandontologicalmonism,rather than dualism. That is to say that, whilst identity appears separate to our physical bodies, this is because it is ultimately an abstract concept, but one which can be reducedtophysicalprocessesinthebrain.

It can even be argued that, since the mind and self are constructed by the brain, they supervene on the brain.

As I have now made reference to my physicalist theory of consciousness, I shall proceed by explaining how the brain constructs our conscious experiences. In Being You: A New Science of Consciousness, Professor Anil Seth outlinesthetop-downmodelofperception. The model presents our perception of reality as a brain-based guess based on inferences as to the sources of sensory information received by the brain. For this reason, Seth refers to conscious experience as a “controlled hallucination”, because we donotdirectlyperceivethematerialworld, instead we construct an idea of what it is likely to be. As part of the argument from illusion, phenomenalists have long illustrated this difference between perceptionandthephysicalworldwith

examples of delusive perceptual experiences. For example, I may see a stick in a jug of water, it appears to bend at the pointitentersthewater,butIknowthisnot tobethecase.Therefore,myperceptionof the stick cannot be direct, as I do not perceiveitasitexistsinreality.Historically, naïve realists, who argue that the senses provide direct representations of the physical world, have criticised such examples by claiming that only delusive perceptions are indirect. However, this criticismisrightlydismissedbyA.J.Ayerin The Foundations of Empirical Knowledge. Ayer points out that delusive perceptual experiences are qualitatively indistinguishable from veridical ones, the only difference being the accuracy with which they represent the physical world. Hence,itfollowsthatallourperceptionsare indirect,notjustthoseincasessuchasthat of the ‘bent stick’. Ayer also introduces ‘sense-data’languagetoclarifythemeaning ofstatementsmaderegardingperception.A sense-datum,accordingtoAyer,iswhatwe directly perceive. This is not a material thing,butthemind’srepresentationofone, so instead of saying “I see a bent stick”, we should,forthesakeofclarity,say,“Isensea sense-datum of a bent stick, which is my delusive perception of a material stick that is, in reality, straight.” To summarise, our perception of reality is not direct, instead, we are conscious of sense-data that representthematerialworld,althoughthis

representation may be inaccurate. So, our conscious experiences are formed in the brain, and it can be concluded that our Lockean identity is a hallucinatory construction.

Basedonthisconclusion,somemaystartto question whether we exist at all, but fortunatelythisscepticismisunjustified.In his Discourse on the Method, René Descartes declares that “I think, therefore I am”. By this maxim, Descartes is asserting that one’s existence can be logically deduced from their ability to doubt their ownexistence,as,todoubt,onemusthave a mind, and, therefore, exist. Whilst Descarteserrsinthepremisesthatleadhim to this conclusion, he is ultimately correct, although the principle could be better phrasedas“Iperceive,thereforeIam”.This is because, as I have shown, the processes involved in constructing our conscious realitiesarebiologicalprocessesinthebrain. Therefore, for us to perceive the world, be thisperceptionveridicalornot,wemustbe living organisms. From this, it follows that we have selfhood, as our continued existence provides a constant stream of conscious experiences, though these are at leastpartialhallucinations.

(experiential) knowledge as untrustworthy. At first glance, this may appear to logically follow from the knowledge that our conscious experiences are hallucinations. However,A.J.Ayerhighlightsthatthisway ofthinkingisfallacious,asitisgroundedin anincorrectassumptionaboutthenatureof a posteriori knowledge. Experiential knowledgecannot,bydefinition,becertain as it is obtained via inductive reasoning. Thus, Descartes’ dismissal of a posteriori knowledge is misguided as it is impossible to guarantee the truth of such knowledge, insteaditcanonlybehighlyprobable.

“To think, therefore I am” "Cogito ergo sum" RENÉ DESCARTES

Scepticsmaynowconcedethatwedoexist, but question whether we should disregard allofoursensoryexperiencesaspotentially delusive, leaving us without the psychologicalcontinuitythatcomprisesthe self. This thinking resembles Cartesian doubt,aformofmethodologicalscepticism adopted by Descartes, which is centred aroundthedismissalofallaposteriori

Furthermore, the potential inaccuracy of a posteriori knowledge in its representation of reality is ultimately not very significant. This is because, there is hypothetically a ‘real’self–onecomprisedofitsexperiences in the objective reality outside of our hallucinations (experiences of what Immanuel Kant calls ‘things-inthemselves’). However, we a conscious of the illusory self, and thatthisappliestoeveryonemeans as well call this state of consc ‘reality’andforgoanyattemptate astothenatureoftheobjectivere the ‘things-in-themselves’ that com ProfessorAnilSethsuggeststhatw do this by saying that “ we hallucinating all the time, it is when we agree about our halluc thatiswhatwecallreality.”

Inconclusion,theselfisanillusion,asisall of our conscious experience, yet this is not as problematic as it may appear. It is true that perception is indirect and constructed by the brain; it is true that we can never experiencerealityasitreallyis;anditistrue thattheself,asunderstoodbyLocke,hasno bearing in the objective material world. However, this is true of everyone, so we canstill have selfhood, albeit with the knowledge that this is artificially constructed. Taking Locke’s view of identity,wecouldhavea‘real’self,separate to the one we are conscious of; a stream of experiences shaping a psyche that we cannotaccessasitispartofaphysicalworld we do not perceive. This ‘real’ self would likelynotmassivelydifferfromtheillusory self, as the latter is still formed from sensedata that, for the most part, stem from reality. Talk of this ‘real’ self is, however, withoutpurposebyvirtueofnotexistingin the‘reality’weareconsciousof.Instead,the illusory self is as real as anything we can everexperience.

“We are all hallucinating all the time, i that when we agree about our hallucin that is what we call reality”

ANIL SETH