Tufts Observer

feature

The Afterlives of Anti-Imperial Tufts Student Activism Pt. 1

Billy Zeng

news

Building Walls, Breaking Promises: Revisiting the USMexico Border under Biden

Emara Saez

poetry & prose

One, Two, Three

Layla Kennington

museum of steel rosaries, and burning film

Mariana Campano

magnolia tree

campus

Ashlie Doucette

opinion

Rankings vs. Reality: the Numerical Value of a College Education

Lauren Langbort From Music to Movies: How Digital Platforms Influence Our Cultural Consumption

Spencer Vernier

Weaving Indigenous Narratives: Interconnectedness in TUAG’s Double Arrows

Emma Duran arts & culture

For the Sake of Humanities: Addressing the Facilities Divide at Tufts

Miles Kendrick

Fair Wages, Fair Education: The Union Struggle at Tufts

Seun Adekunle

Editor-in-Chief

Juanita Asapokhai

Managing Editor

Emara Saez

Creative Directors

Anastasia Glass

Hami Trinh

Art Directors

Audrey Njo

Uma Adulbehram

Feature Editors

Ruby Goodman

Rohith Raman

News Editors

Kara Moquin

Arts & Culture Editors

Sophie Fishman

Ava Vander Louw

Opinion Editors

Lucy Belknap

Megan Reimer

Campus Editors

Clara Davis

Eli Marcus

Poetry & Prose Editors

Veronica Habashy

Neya Krishnan

Creative Inset Lead

Aviv Markus

Editors Emeritus

Melanie Litwin

Amanda Westlake

Staff Writers

William Zhuang

Layla Kennington

Erin Zhu

Leah Cohen

Billy Zeng

Joyce Fang

Seun Adekunle

Matilda Peng

Bella Cosimina Bobb

Spencer Vernier

Sacha Waters

Anna Farrell

Designers

Madison Clowes

Maria Cazzato

Aviv Markus

Rachel Li

Kaya Gorsline

Unmani Tewari

Staff Artists

Zed van der Linden

Maria Cazzato

Phoebe McMahon

Mariana Porras

Chileta Egonu

Stella Omenetto

Ava Hudson

Annica Grote

Elika Wilson

Lead Copy Editors

Ashlie Doucette

Alec Rosenthal

Copy Editors

Sofia Valdebenito

Emma Castro

Madison Greenstein

Mia Ivatury

Miles Kendrick

Anne Li

Publicity Directors

Aatiqah Aziz

Sofia Valdenbenito

Publicity

Emma Itturegui

Francesca Gasasira

Leah Moradi

Podcast Directors

Grace Maisello

Noah DeYoung

Podcast

Caroline Yang

Emily Pham

Isaac Ulloa Antonio

Tamara Setiadji

Erin Guy

Soraya Basrai

Eden Weissman

Website Manager

Clara Davis

Treasurer

William Zhuang

Contributors

Lauren Langbort

Emma Duran

Mariana Campano

black and white, life and death, yin and yang, dogs and cats, sun and rain, sweet and sour, water and fire; all seemingly contradictory, but generative when placed together. there is power in difference, it just takes a willing eye to see it.

By Billy Zeng

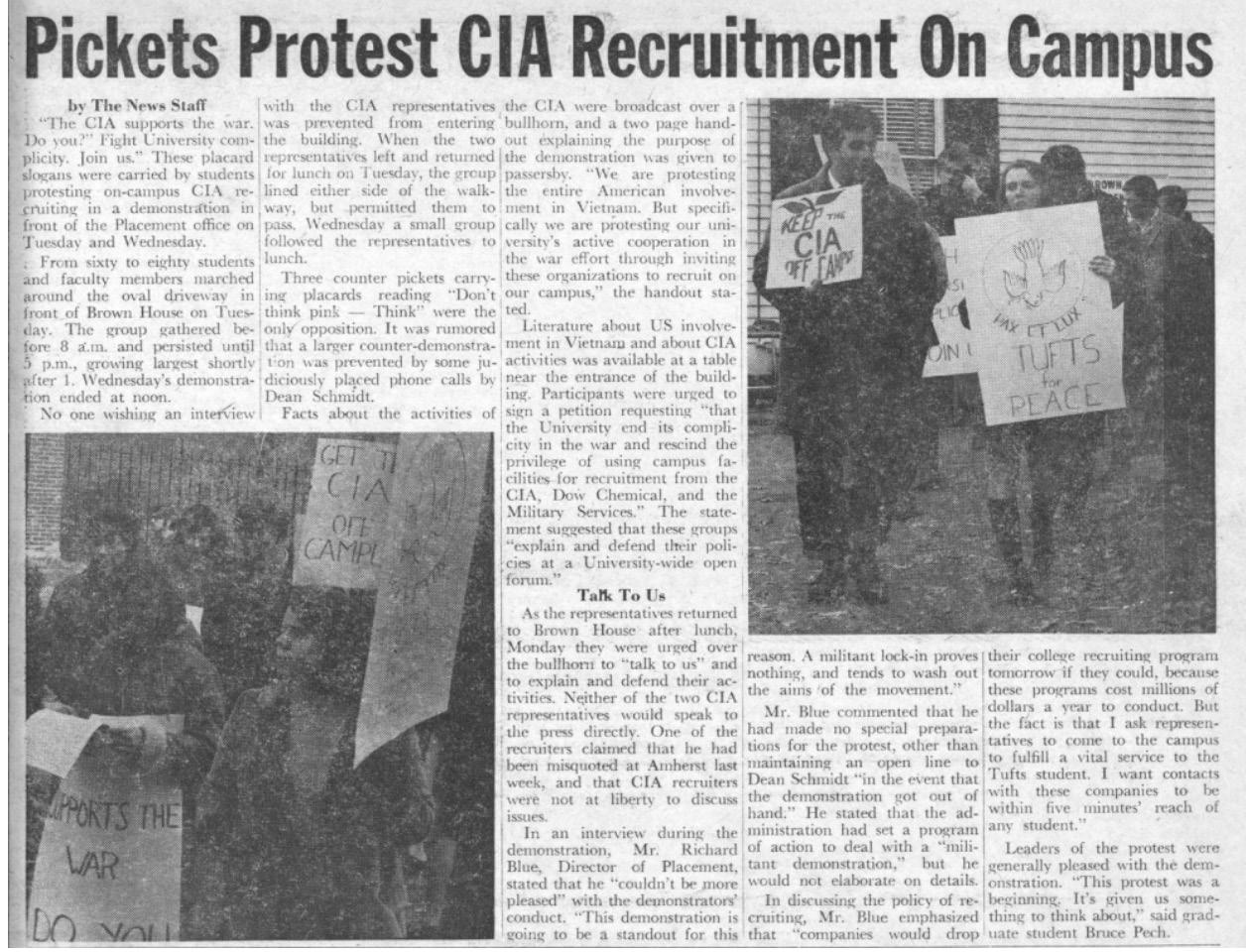

November 6, 2023 will mark the 55th anniversary of the start of the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF).

The TWLF was formed by members of San Francisco State University’s Black Student Union and other political student groups of color in the late 1960s. Forming a united student front, the group went on to initiate a five-month strike calling for better treatment of minoritized students from their institution. The TWLF strike became one of the longest ever initiated by students in the United States. The strike stemmed from the frustrations of San Francisco State students with biased admission practices that barred students of color from being admitted at the same rates as their white counterparts. The coalition also demanded a change to the dominance of Eurocentrism in their education. They wanted visibility in a curriculum that empowered “Third World peoples”—a term used during the 1960s to refer to minoritized and working-class peoples—according to their demands.

TWLF’s vision and values have become central to the founding and teaching of ethnic studies on university campuses across the country as well as US-based international solidarity organizing.

Not only was the TWLF concerned with the US education system, but the coalition was also focused on the political stakes of the ethnic education they demanded. Inspired by the growing anti-war US movement and calls for the US government to pull American troops out of Vietnam, TWLF organizers connected this incident of US imperialism

in Vietnam to their visions for a third world education.

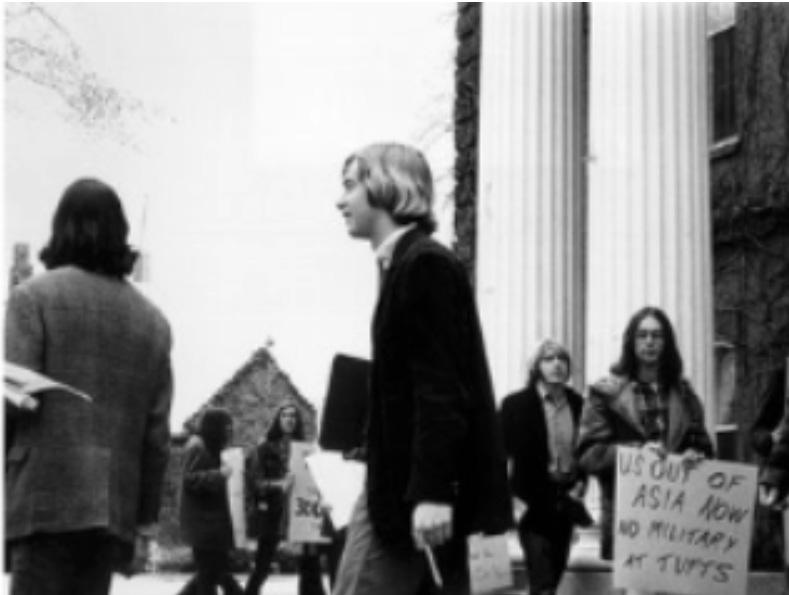

Heavily rooted in anti-imperial activism around the world, the legacy of TWLF has expanded far beyond the boundaries of the 1960s radical Bay Area. The seeds of the TWLF have been sown across the country, from San Francisco State to Tufts University, where anti-imperial student organizing has defined student life and campus politics over the last 50 years.

Brian, a current senior who asked to be identified only by first name, described in a written statement to the Tufts Observer how “part of the mission of anti-imperial organizing is to make it clear that the interests of these [politically motivated] organizations, unions, and student groups, ultimately lie in the ending of this capitalist system and the institutions that prop it up at home and abroad, such as the US military, weapons contractors, and intelligence services.”

This legacy of radical student activism has been well documented by past Tufts students and the Tufts archives. Access to this history provides entry points for the Tufts community to apply effective tactics and strategies to campus organizing today.

Dan Santamaria, Director of the Tufts Archival Research Center (TARC), wrote in a statement submitted to the Observer , “We hope that students working with archives take away that they are part of a long legacy of activism and of people working to try to improve the lives and work of everyone in the Tufts community… [to learn] about what strategies for en -

acting positive change were effective and building organizational continuity across generations of students.”

Three of the most prominent examples of past anti-imperial student activism have been extensively documented by TARC: student oppositions to the Vietnam War from 1967-1972; student-faculty organizing against the Marcos regime in the Philippines donating money to the Fletcher School from 1977-1981; and student mobilization for Tufts to divest from South Africa apartheid from 1977-1989.

Note: These are not comprehensive histories. Many more materials exist at TARC that dive into each of these three campaigns in much more extensive detail.

Opposition to the Vietnam War was growing in the late 1960’s, and Tufts students were no exception. In the fall of 1967, students protested against the CIA and Dow Chemical Company, two military institutions that sought to recruit students to join the war effort. In 1968, the Student Council held a vote that aimed to ban military recruiting on campus. The Student Council supported this initiative, but then Tufts President Burton Hallowell rejected the student advocacy effort, according to TARC.

The anti-war movement reached its peak once President Nixon publicly declared that the US would involve its military in Cambodia. When mass opposition erupted amongst college students, the government responded by deploying National Guard troops on campuses across the country to suppress student protests. Anti-war sentiments at Tufts were fueled by a clash between National Guard troops with Kent State University students that triggered a nationwide student strike.

Tufts students held rallies to criticize the war and violence against protesters, culminating in the cancellation of final exams during the spring semester of 1970, according to the archives.

According to the same edition of the Observer , a handwritten note made its way to then President Hallowell that claimed credit for the bombing. The group was known as the Arson Squad, who said they bombed Dean Guillon’s office to express solidarity with the people of Laos who were fighting against American imperialism, led by agents trained at Fletcher. The note concluded by confirming that this act of violence was the only way to demonstrate to America the destruction it was enabling abroad in Southeast Asia.

Anti-war movements around the country eventually paid off when President Nixon began withdrawing US troops from Vietnam starting in June 1969.

A March 1971 edition of the Observer reports that “the Fletcher School and its deans have been constant targets for campus political activists and the local SDS [Students for Democratic Society] chapter. Criticism has largely focused on Fletcher’s role in furthering the aims and activities of imperialist American capitalism and the military.”

Edward Gullion, Dean of the Fletcher School in March 1971, had his office firebombed in the early morning by a group of anonymous students, reflecting the increasing intensity of antiwar activities on campus in the spring of 1972.

Marcos regime, Philippines, and the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy

Six years later, the Fletcher School was yet again a target of student protest and activism. This time, students were calling out the Fletcher administration for accepting a $1.5 million grant from the Marcos Foundation, according to a 1977 edition of the Tufts Observer

The grant money was proposed to create an endowment fund where a program could be developed to teach Fletcher students about “the history, politics, development, economics, cultures, and foreign relations of East and Southeast Asian countries,” according to the same 1977 edition of the Observer . Part of the endowment also proposed the establishment of a Chair of East Asian and Pacific Affairs under the name of Ferdinand E. Marcos, the dictator of the Philippines at the time.

In late October 1977, Mrs. Imelda Marcos and Carlos P. Romulo, the First Lady of the Philippines and the secretary of foreign affairs for the

Philippines, visited Tufts and met with President Jean Mayer and other members of the Tufts administration to discuss the details of this newly proposed endowment. Fletcher was chosen as the ideal candidate for their philanthropic initiatives because of its growing reputation as a prestigious institution for international relations. Secretary Romulo specifically cited that “President Marcos has dug deep into [his] resources (for this gift) so that people of the United States may know [the Philippines] better.”

In the same 1977 edition of the Observer , Tufts students questioned why the First Lady of the Philippines at the time was donating money to a “rich American university instead of to her own people” when poverty rates and living conditions in the Philippines were so dramatically worsened under martial law.

Dean Gullion dismissed student concerns and voices. He was quoted as having labeled their sentiments as “complete nonsense.” President Mayer additionally “defended Tufts acceptance of the gift on the grounds that it is strictly for academic purposes and does not tie the university to the Philippine government.”

The original plan for the $1.5 million distribution was for the Marcos Foundation to pay Fletcher $500,000 from 1978-1979. The remaining $1 million was to be distributed at a later date. However, the archival records suggest that it was largely because of student and faculty activism that the Marcos Foundation eventually decided to withdraw the funding. Marcos lifted martial law in the Philippines that same year, creating another motive for Tufts to withdraw the funding.

Historically, student organizing has taken the form of student groups challenging and demanding change from the Tufts administration. One such group was a Tufts chapter of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), formed in the fall of 1964. This student organiza -

tion would eventually “become one of the largest organized opponents of the [Vietnam] war on the Tufts campus.”

Tufts SDS’s mission statement included the commitment to “rebuild [their] universities as truly humanist institutions of learning” and “democratize all the major institutions of our society.” The legacy of activism planted by organizations like Tufts SDS continues to be relevant in the present, providing Tufts students with a historical model for developing a radical political consciousness on campus.

Students in the past leaned on the power of collective action when organizing in their struggle to push for what they believed in, a method that can serve as inspiration for the current moment. Nick Rabb, a Computer Science and Cognitive Science PhD student, currently teaches an elective in the Science, Technology, and Society (STS) department titled “Data and Power: Surveillance.” In a written statement to the Observer, he said “there are certain levers that students have access to when they want to make change, and the more people they have to push on the levers, the more they can make the university listen to them rather than to their funders, board, or donors.”

In addition to their activism on campus, anti-imperial students also took more non-classroom based approaches to political education with the goal of radicalizing students on campus. The famous Tufts tradition of painting the cannon, for example, is rooted in a history of anti-imperial student organizing.

Some student activists feel that disruption is the most effective strategy to call attention to issues they are passionate about. Brian said, “If Tufts students are to stop Tufts from backing this imperialism, they will have to make ‘business as usual’ unsustainable for the university. The university will not drop these profitable investments, the prestige, and research funding that these imperial connections bring if it is not forced, and, if they are unified and organized, Tufts students have the collective power to force it.”

Tufts students of the past did not organize alone. With the abundance of colleges and universities in the Greater Boston area, there is a rich history of intercollegiate anti-imperial activism.

For example, the Tufts SDS chapter worked with Harvard students to create political education spaces for students to learn about South African apartheid. The longest anti-imperial student campaign recorded in the archives was in response to Tufts financial investment in the South African apartheid government. It took twelve years of student pressure and activism for Tufts to finally divest from the apartheid government in 1989.

Refer to this Observer published in 2021 for a quick history overview of student activism at Tufts related to the anti-apartheid in South Africa movement: A Legacy of Oppression.

A 1965 edition of the Tufts Weekly describes these inter-collegiate spaces as, “Part of the Boston student anti-apartheid movement, directed at American corporations who continue[d] [providing] economic support to the undemocratic African nation and against the US government’s refusal to impose economic sanctions against South Africa.”

at UMass Boston,” wrote Emily Hoffman in a senior thesis titled Three’s a Movement: Student Demographics and the Anti-Vietnam War Movement at University of Massachusetts-Boston, Tufts University, and Wellesley College for the Department of History in April 2019.

To Brian, “The best way for students to build on these legacies is to not let the lessons of past struggles go unlearned by us in the present. Decades of student activism on just the Tufts campus, let alone the rest of the world, gives plenty of evidence of the power that an organized, active, and conscious student body can have.”

Alongside a history of collaboration with other institutions in the Greater Boston area, anti-imperialism organizing at Tufts was oftentimes a joint effort between students and faculty.

This was not an isolated event, but part of a growing web of collaborative anti-imperialist activism. Students protesting the Vietnam War frequently interacted with students attending the University of Massachusetts (UMass) Boston and exchanged organizing strategies. “When the antiwar movement became a national force in the fall of 1967, Tufts students were quick to join. They followed many of the same protest trends as the students

For instance, in 1978, “80 students marched in a candlelight vigil calling for divestment [from Tufts’ investments in companies upholding South African apartheid]. The group chanted and sang in front of President Mayer’s house for over an hour, and also dropped off a petition signed by students and faculty calling for divestment,” according to the South African Divestment entry in the Concise Encyclopedia of Tufts

History, a project that seeks to record Tufts institutional history.

During the anti-Vietnam War movement at Tufts, professors used their positions within academia to speak out about war and to educate their students. Hoffman wrote that during the time of the campaign, “the arts and sciences faculty voted prior to the [October Moratorium, an event intended to think critically about the war] to suspend classes and use the time for an extensive educational program about the war.”

Professors also went beyo nd the classroom to take a stance in the anti-war protests. The Tufts Weekly from 1966 details a letter written by Tufts professors in the Boston Area Faculty Group on Public Issues that “called for an immediate de-escalation of war, withdrawal of American troops, and meaningful peace negotiations.”

During the period of the Marcos grant advocacy, students found ways to build power with faculty members from various departments across the university. Students and faculty organized alongside one another to put pressure on Tufts to cut ties with the Marcos regime and to hold the administration accountable for Fletcher’s ties to the violent legacies of US imperialism in the Philippines, as noted in the archival records.

relative safety to speak out, join protests, and call others to do the same. It is important to remember that this is not just the students’ struggle, and that, in fact, the anti-imperial movement is made much stronger when broader sectors of the people join in.”

Brandon, a Greater Boston-based anti-imperial community organizer who asked to be identified only by first name, agreed. He said, “Professors should also be engaged politically with [what] students are trying to do

sake. The best way to honor these legacies is for students to have a clear idea of what needs to be fought for and the level of organization and activity to see the struggle through.”

This article is the first in a twoarticle series on past and present antiimperial activism on Tufts campus. Read pt.2 in the Observer’s upcoming issue 4 this semester. O

[on campus]. Aside from helping uplift those struggles, alongside the students, those [professors] can also help pass down experiences of organizing and the [institutional] knowledge. Professors should also be talking to other professors and staff about these situations, so it’s not just a student movement.”

A coalition of students and faculty known as the Get Marcos Off-Campus Committee (GMOCC), proved to be effective in protesting the endowment. A December 1977 edition of the Observer reports that the GMOCC “[was] an organization of fluctuating size, comprised of students, faculty and staff who…feel that ‘by accepting the money, by maintaining a chair named after Marcos, and by honoring Mrs. Marcos as a humanitarian, Tufts is lending support to the repressive Marcos regime.’”

Brian shared that “professors, especially tenured ones, have a lot of protection from university retaliation, and they would in theory be able to use that

Even now, educators are weaving conversations about imperialism into their classes. In “Data and Power: Surveillance,” Rabb writes that in his class, they “explicitly think about state oppression in these cases—whether the state doing the oppressing is the US or Israel, in our examples—and how surveillance technologies embody and enable oppression.”

This rich history of collaborative organizing is still present at Tufts today. Brian reminds students that “[they] cannot fall into the practice of ritualistically painting the cannon whenever the next atrocity is committed, they cannot fall into tradition for its own

By Miles Kendrick

Humanities students returned to a sweltering disappointment this fall, as near-record-breaking temperatures forced multiple humanities classes—most of which are non-air conditioned and sparsely windowed— to end early. These incidents have revived frustrations surrounding the humanities-STEM facility divide, one that seems to prioritize science, technology, engineering, and mathematics facilities over their humanities counterparts.

As the $90 million Joyce Cummings Center approaches its two-year anniversary, Eaton Hall remains under construction, its first major renovation project in almost 60 years just recently making headway. Lincoln Filene Hall, described by former Dean of Tisch College Alan Solomont as “a crappy building” needing “more renovation than it’s worth,” remains home to several humanities classes and departments. Students in Braker Hall fan themselves with folded-up poems and crumpled study guides while professors in Miner Hall search the floor for nubs of chalk with which to write the date.

These scenes juxtapose a more comfortable existence in STEM buildings like the Science and Engineering Complex, which houses departments like biology and mechanical engineering and includes amenities like kitchenettes, gender-neutral and accessible bathrooms, an outdoor patio, JumboPrint stations, and Kindlevan Café. For STEM students, learning environments are comfortable and collaborative, leaving many in the humanities to question Tufts’ priorities.

“It makes me feel like we’re just being neglected,” said third-year English major Natalie Bricker. “It really does count for a lot when you’re physically

comfortable in a class and you can actually focus on what’s being taught.”

Bricker was walking into her first day of “Black World Literature” in Lane Hall this September when the classroom temperature overtook her. “It was too hot to think,” she said. The professor ended class just halfway through the lecture, reflecting the decisions of other humanities professors facing similar conditions.

One such professor was James Lipsky, a lecturer for the Eliot-Pearson Department of Child Study and Human Development with a focus on American Sign Language and Deaf Studies. Through an ASL interpreter, Lipsky explained that for his classroom to function, students must be able to sit in a semicircle where both himself and a projector are visible. “ASL is a visual language,” he emphasized. “When I sign, everyone needs to see me signing.”

However, this year, the Office of the Registrar moved his class from Anderson Hall to Bromfield-Pearson. Anderson Hall was last renovated in 2017 with the completion of the SEC and includes a number of sign language-accessible features like open rooms and visible monitors. Bromfield-Pearson, as Lipsky came to find out, was a decidedly worse fit. “I thought [the move] might be a good idea… but I did not expect so many chairs to be in there and for the screen to be above the board,” Lipsky explained. “I was wrenching my neck to look back, and it was too hard for me to point out different things.” After complaints to the Office of the Registrar, the class was returned to Anderson Hall.

Another one of Lipsky’s classes was suspended due to uncomfortably high classroom temperatures. “They said that the city turned [the AC] off. Anderson Hall had AC, but this building did not, so I didn’t understand,” he said. “I had two classes, and by the second class I had to stop… it was just too hot.”

Lipsky’s experience is not unique. Instead, it seems to be just one of many examples of institutional failings when it comes to the humanities.

Part of the issue is caused by discrepancies in donations. The JCC, for example, was primarily funded by a multi-million-dollar donation from the Cummings Foundation, founded by real estate mogul and Tufts alum Bill Cummings (LA58). The same group made a $50 million donation to Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine in 2004, the largest endowment in Tufts history.

Beyond donations, though, many hold the loss of Eaton Hall responsible for much of the current disparity.

Eaton Hall, originally opened in 1908 as the university library, served as the central hub for humanities departments beginning in 1965. In 2020, after the collapse of a ceiling in Room 202, the building was officially closed for renovation. Today, Eaton Hall remains under construction and is not expected to reopen until the next academic year.

Heather Curtis, the Warren S. Woodbridge professor of religion and director of the Center for Humanities at Tufts, accredits Eaton’s absence to the current disparity in facilities. “While Eaton is offline being renovated, it’s

been really challenging, at least within my department, to have excellent spaces for humanities teaching,” she said.

The loss of Eaton Hall has forced the redistribution of humanities classes across several older buildings like Braker, Lincoln Filene, and Miner Halls, many of which are not equipped for the number and diversity of courses currently being taught. “There are two kinds of teaching in the humanities. There’s sort of a larger lecture course… and there are small humanities discussion seminars,” explained Curtis. While, in her own experience, larger lecture classes are reasonably easy to find, “Right now it’s almost impossible to find a space [for the small humanities discussion seminars].”

Curtis suggested that although the SEC and JCC currently serve as undeniable examples of superior STEM facilities, the opening of Eaton will restore feelings of equity among the humanities. “There really isn’t a signature building for the humanities, so I feel like Eaton is going to be a step in that direction.”

The loss of Eaton Hall raises interesting questions regarding the concept of place, particularly as it relates to one’s sense of belonging and inclusion.

Professor Cathy Stanton, a distinguished senior lecturer in the Department of Anthropology and the Department of Environmental Studies, has been studying the anthropological “place” for much of her career. She explained that “a sense of a center” is key to creating place within a community. “[Good places] shouldn’t just be

an amorphous, atomized kind of space. There needs to be cohesion and comprehensibility,” she said.

This kind of cohesion is important not only because it creates structure but also because it creates a sense of belonging. “Campus communities are really strange and complicated… We have to make a sense of home and belonging very quickly with a whole bunch of strangers,” said Stanton. “If you’re inclined to feel like you’re not quite sure that you belong to begin with, then having a space that doesn’t open its arms to you… is maybe [going to] underscore that.”

Like Curtis, Stanton believes that the return of Eaton could restore a sense of cohesion to the humanities. “We had that over in Eaton, and we’re hoping to have it again.”

Some, though, are less willing to sit and wait. After leaving her “Black World Literature” class on that sweaty first day, Bricker sent an email to Dean of Students Camille Lizarríbar and Associate Dean of Student Affairs Kevin Kraft demanding working AC in Lane Hall. “I was feeling really frustrated,” she explained. “I kind of felt like, at this point, I needed to make some noise.”

In this instance, the noise was heard, and Lane Hall had AC by the following Thursday. Bricker, though, remained skeptical. “I don’t really know if my email led to things being fixed because I also filed a work order and called a number that I found on the department site.” She never received a response from either of the deans.

How much credit, then, does Tufts deserve for their handling of the facilities divide? As humanities director, Curtis suggested perhaps more than some are giving them.

“[Tufts] really has been addressing one thing at a time within budgetary resources to make the humanities spaces better,” she explained. “The new provost and the new vice provost are both really dedicated to the humanities and do seem to be aware of how important the humanities are to Tufts and to academic inquiry more broadly.”

In terms of fostering an anthropological “place” for students and community building on campus, Stanton, too, believes that Tufts is heading in the right direction. “They’ve got a long triage of what needs doing first. Some of it is opportunistic, some of it has to do with donors,” Stanton said. “But I do feel like the admin is paying attention and cares about the physical, spatial, and inclusive kind of experience that students have.”

In a written statement to the Tufts Observer, the Office of the Registrar maintained that they do not prioritize any department or group of subjects over another and that their team is constantly looking for ways to advance and refine the scheduling process.

For some, though, it will take more than promises of things to come to restore the trust lost. “I want to give Tufts credit. I so badly want to say thank you for treating humanities majors the same [as STEM majors], but I can’t say that right now. So it just makes me really frustrated,” sighed Bricker. “I just don’t feel like we’re a priority at Tufts.” O

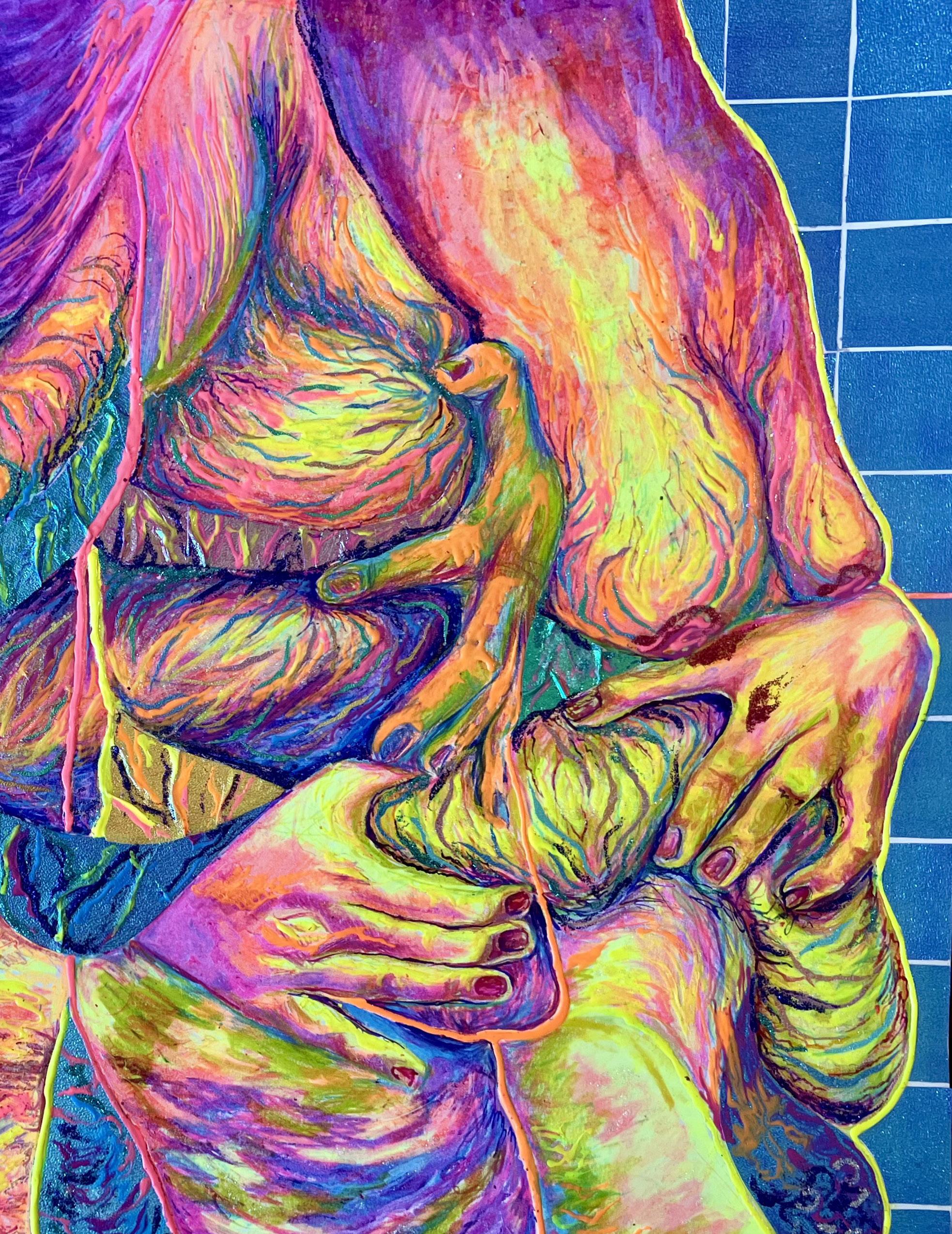

We are sitting tightly packed, regardless of the expanse of the living room available to us. Kitchen chairs are jumbled around the aging television set, limbs pressed against the chairs’ hardwood, brown against brown, feet splayed like they’re ready to launch you up at any moment. I am kneeling between my grandmother’s legs, head tilted partially so she can access my scalp, partially so I can watch the TV. My toes take turns digging into the carpet’s fibers out of both boredom and a muted pain radiating from just above my forehead. My body continues to twist itself in other ways: sometimes I hold my breath, sometimes I wring my fingers. My mother sits beside us, a comb in her mouth, separating long bundles of hair. She is ready to hand us whatever we need, sometimes craning her own neck to see the state of my grandmother’s handiwork.

are in the heart of the house, of the street, and of the entire universe to the extent that I can tell. The only insight that the outside world exists at all is the flashes of content on that glowing box before us. It has passed midnight, the time when only the degenerate and especially perverse are supposed to be awake. We watch four episodes of Unsolved Mysteries and my soft, underdeveloped brain is rocked with images of spousal disappearances, drownings, and darkness. I do not yet believe that death can occur in people that I know. It seems surprising that bad things can exist at all in that too-warm, too-bright room.

It is here that I am vaguely aware of my mother’s own girlishness. I am familiar with following her around the house in the manner of an overeager puppy, and it is that same eagerness that I see in her quiet deference to my grandmother. We are contorted like puzzle pieces around each other, coming together in a medley of efficiency and care. There lives a sort of muted divinity in our tired trio, and my still-forming body believes it knows true completeness and harmony. By the time the sun rises, my hair will be fully braided, regardless of the few times we stop for a break for the sake of my still-tender scalp. When I nod off at various points throughout the night, it is because I am lulled to sleep by the subtle thwacking sounds the hair makes as it transfers through her fingers and against itself. One, two, three– a whispered and consistent lullaby.

When I finally twist my head away, squirming at one too many probable deaths, I am greeted by a swift tug. Keep your head this way, she says. Bad things don’t happen in this family , she says. And I am inclined to believe her, for the only badness I can perceive at this point in my life are stiff limbs, fatigue, and an aching scalp.

And everything is so warm. The floral couches are a faded, lived-in yellow. The walls are a deep red, the result of one of my grandmother’s other creative, domestic escapades. And while the rest of the house is dark, the room, the television, and the women inside of it emit a lone light. We

As years go by, the stiffness in both of their hands will become permanent. I have since learned to braid my own hair but do so only on certain occasions, as it takes much longer alone. My body is longer now, and it knows stiffness mostly in the context of growth. I am still getting used to all the ways it can move itself and spend most of my time trying to hide it from all those who knew it when it was smaller.

When I do braid my own hair, I am careful to keep my head at a certain angle so I can get the parts just right like she did. I hold the three strands in my hand and inter- lock them. The hair comes apart and back together, over and over, until I reach the end. The process repeats until the sun comes up, or sometimes it goes down, but it always ceases by the time my wrists

feel as though they could give up. And although I find peace in this ritual, it often seems that with every moment I am weaving a sort of lie into myself. For not only are my parts perpetually crooked, but at this point, I have learned that bad things do happen in our family, and I am learning what badness means outside of discomfort. Seven years later, as I am teetering on the edge of teenagehood, the trio is broken. It is a reality that greets me when I find my mother on the floor. Again her body has twisted itself into a seemingly unnatural shape, yet grief lines the contours of her limbs. I don’t know what to do, she says. I am all alone, she says. And I feel as though we are not enough just the two of us. Apparently, not all deaths can be sensationalized, and most are too ordinary to end up on the TV. I am not sure how my body interlocks with just my mother’s. I am hyperconscious of all this newness, and we sit on opposite ends of the wall. She holds herself and I am painfully aware of all the ways I can and cannot move. One, two, three. I say to myself to calm down. One, two, three.

By Emma Duran

Tufts University Art Galleries (TUAG) opened its fall show Double Arrows on September 5, featuring the art of Elizabeth JamesPerry, a member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head Aquinnah on Noepe, also known as Martha’s Vineyard. Her art is inspired by the practices of Northeastern Woodland cultures, focusing on weaving and the use of white and purple wampum shell carvings of the Atlantic Quahog clam. Upon entering the show, viewers will be met with the same peace felt while being in nature. The spaciousness of the room creates a languid atmosphere, fostering the sense that there is enough time and space to take everything in and that each display of artwork will reveal its quiet details through careful observation and appreciation. After walking through the door, gallery viewers will immediately see a gorgeous image of the ancient Aquinnah Cliffs jutting out into the ocean with plants waving in the foreground, one of the most sacred sites of the Wampanoag tribal homelands. Beside the cliffs there is a picture of James-Perry’s garden of green

sprouts glowing with life, titled The Future. These first pieces orient the viewer to the themes of James-Perry’s work: the connections between land, water, plants, and, of course, us.

James-Perry’s artwork focuses on human connection to the natural world. She draws from her background in marine biology to explore this connection beyond her wampum jewelry and textiles. She was involved in bringing together the perspectives of several northeastern Tribes and agencies for Ocean Planning Body meetings, an initiative created under the Obama administration to protect marine areas. James-Perry also helped the New Bedford Whaling Museum develop educational panels on seals and designed the Milkweed Warriors mural for TUAG in response to the designation of monarch butterflies as an endangered species.

From the inclusion of other Indigenous artists who also explore interconnectedness in their work, to the foraging many of the artists partake to collect art materials, the idea of human connection with the natural world is present at every level of the exhibition. Among the col-

laborators are the artist’s brother, Jonathan James-Perry, a traditional dancer, speaker, singer, and carver, grounded in the traditions of his ocean-going ancestors. Another contributor is the artist’s mother, Patricia James-Perry, who works with scrimshanding, the art of handcrafting items from whale ivory, bone, and antler. Outside of the artist’s family, the show also includes work from SMFA faculty member Tanya Crane, a jewelry artist who draws from natural materials to honor African American craft traditions, and Erin Genia (Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate), a multidisciplinary artist who uses her role as an educator and community organizer to amplify the voices of Indigenous peoples in the arts.

The organization of the exhibition itself speaks to the interconnectedness of the natural world which James-Perry explores in her art. Laurel McLaughlin, organizing curator of Double Arrows spoke on James-Perry’s dedication to collaboration. “We initially invited her to do a solo exhibition, but in keeping with Elizabeth’s way of working, she’s always thinking about collaboration, kinship ties, working with the environment and also with her collaborators, it felt very appropriate that she extend[ed] our invitation to her collaborators. It

really speaks to the whole point of the exhibition, in creating collaborations with nature, and extending it beyond to both human and nonhuman species,” said McLaughlin.

In a conversation with SMFA Professor Silvia Bottinelli, JamesPerry explained that she included other artists in her exhibition because, “It makes for a richer experience to have pieces in conversation with each other.” This value for collaboration extends beyond James-Perry’s curatorial work for her own exhibition and connects to the Indigenous worldviews, that see the individual as interconnected to the land and all life. Artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation echoed the significance of interconnectedness in her own work, saying, “My content has a relationship to every single Native artist, their work, and their humor… They’re the ones that make my world go round because the content in their work is feeding me.” Walking through the Double Arrows exhibit and viewing art from multiple artists will lead gallery attendees to consider not only how each piece is related to the environment, but also how they relate to each other.

Aside from Tanya Crane’s Voyage sculpture mounted in the center of the back wall, James-Perry’s work lines the entire gallery, almost as if her work is the supporting cord of a necklace and Crane’s creation of reeds, fibers, and NuGold is the pendant dangling in the middle. On the floor of the gallery are displays of James-Perry’s wampum jewelry and a handwoven mat. Mashq (Bear) is a necklace with a string of milkweed colored with bloodroot dye strung through a piece of Quahog wampum consumed with a swath of deep purple. Another necklace titled Onkeehq, meaning seal in Wampanoag, recalls James-Perry’s aforementioned work

with the New Bedford Whaling Museum. The necklace is made of milkweed and dyed with madder dye. The milkweed string is attached via sinew and bone beads to the wampum in the center, which emulates the body and flippers of a seal. In the middle of these two necklaces lies a bracelet, fittingly called Grounded/Centered. It is a cuff of alternating red and white patterned squares made with porcupine quills, smoked deerskin, thread, and black walnut and cochineal dyes. On the other side of the floor lies the piece On The Earth, a handwoven mat made of ash splints whose alternating shades of white elevate the texture beyond the intricacy of the weaving. These pieces of jewelry and the handwoven mat sandwich the work of other featured artists who also draw upon Indigenous knowledge and materials to explore human connections with the environment. Erin Genias’ Listen, a sound vessel reminiscent of an ear shape or an eroded landscape with turquoise water at the bottom, simultaneously speaks to the power of water and the destructive nature of colonialism. Also in the center of the room are Patricia James-Perry’s pendants from her Pootahpuh Whale Collection. There are three pendants: a narwhal, a sperm whale, and a right whale scrimshawed on cross sections of fossilized mammoth tusks. Jonathan James-Perry’s Blue Heron Necklace uses traditional cold hammered copper to depict an abstract heron. The necklace is strung with white glass trade beads, and the center pendant is hand-engraved Rhode Island slate with strips of rose gold copper on either side. The combination of these artists’ work provides a rich conversation of Indigenous artists, drawing from traditions of their past and posing questions to

viewers about their own relationship to the natural world.

Due to the way James-Perry forages her art materials, it is essential that she is attuned to the cycles of nature and knowing what grows when and where. She wild-harvests cedar, willow, and cattail in addition to growing native plants like milkweed, sedges, and corn to use in her artwork. To dye her braided or spun necklaces, she uses local dyes made from plants: red from bedstraw, orange from bloodroot plants, and green from mint. In her interview with Bottinelli, she added that “walking on the beach to collect seaweed for dyes… you have to plan life around those seasonal harvesting rounds—plant materials simply do not last out in the elements.” If James-Perry does not forage her materials, she grows them. In praise of the mat Sky Beings over Mystic River, McLaughlin emphasized James-Perry’s connection with the reeds used to hand weave the piece, saying, “She grows them, she knows when to harvest them, she knows how to treat them, and how to weave them.” With many of James-Perry’s materials, at no point is there a disconnect between her life and artistic process, as she raises them herself and gives them new lives in the form of her work.

Double Arrows echoes the larger role of Indigenous art in reminding people of the interdependencies we share with the natural world. In an interview for Cultural Survival, a publication that shares Indigenous artists’ stories, Shipibo artist Sara Flores said, “[the] work of art and the work of environmental activism… towards Indigenous sovereignty cannot be

separated; they must move forward on the same path.”

Broadly speaking, in museum history, exhibits of Indigenous art have included only historical objects without drawing connections to Indigenous peoples in the present day. At Tufts, the Double Arrows show at SMFA as well as Véxoa: We Know show at Aidekman Arts Center, display an intentional effort to counter this history and exhibit the work of contemporary Indigenous art and artists on campus. Elizabeth Canter, the manager of academic programs for TUAG added that “In the last 10 years since I’ve been here, other contemporary Indigenous artists’ work has been shown in several group exhibitions, the most notable of which was A Decolonial Atlas exhibition in 2019. There have been other exhibitions that have featured

works from the Permanent Collection, such as re:imagining collections in 2023, which featured antiquities from the Permanent Collection made by Indigenous groups in Central and South America. Additionally, there have been class visits and faculty that have pulled work from the Permanent Collection for object study and research purposes (For example, these Native American objects).”

As for representation of Indigenous art in the future, Canter said, “I think Véxoa marks a turning point for us, as it was curated by guest curator and educator, Naine Terena (member of the Terena Indigenous people of the Brazilian State of Mato Grosso do Sul). The idea of self-representation here is really important and as an institution helps us to consider the stories we tell—who tells them and how we tell them.” There has been programming beyond the TUAG fall exhibits to promote community connection with the art. The Véxoa exhibit had a Reception and Artist Program on September 20, and Double Arrows had a Toast, Tour, & Workshop on September 13 as well as an Artist Talk on October 18. While these events are a wonderful starting point, and Véxoa certainly does mark a turning point, junior Muri Mascar-

enhas, a Brazilian student who worked on the show points out that, “There are few real appealing strategies to support people in interacting with the Indigenous narratives. Works of art displayed in a gallery don’t make an art experience; art is created when others interact with someone’s art. It’s about belonging, connecting, and co-learning.” Indigenous artists, especially the ones shown at TUAG, must be continuously engaged with larger communities in meaningful conversations about their work to ensure that they are rightfully seen as agents of change instead of disappearing into the past. Following their work on Véxoa, Mascarenhas suggested that viewers fully engage themselves in the TUAG exhibits, “There’s a playlist available downstairs at the galleries. Get those songs, walk through the gallery, and let that art belong with you too,” Mascarenhas said. There is room for more connections and conversation within the Tufts community around future exhibits of Indigenous art. “It’s our job to make the exhibits strategically interesting, and now it’s up to people to immerse themselves and share with friends.” O

By Seun Adekunle

From SAG-AFTRA and the Writers Guild to the United Auto Workers, union-led efforts have seen mobilization and impacts across the country at a scale grander than any in the past few decades. This national trend is mirrored by recent developments at Tufts. On August 25, Tufts Student Life sent a statement to the student body, writing that “Union negotiations are quite common at Tufts. However, this fall we have an unusually high number of them taking place simultaneously.” These include recent struggles led by dining workers, RAs, SMFA Professors of the Practice, SMFA part-time lecturers, and graduate student workers.

Two groups in particular—SMFA part-time lecturers (PTLs) and Tufts University graduate student workers—are represented by the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 509 and remain in active negotiations with the university about their contracts.

SMFA PTLs have been negotiating pay increases to bring them in line with other creative faculty. Lizi Brown, a lecturer in the Drawing and Painting Department at the SMFA, said in a written statement to the Tufts Observer, “Tufts has a corporate culture of paying visual art faculty less than other creative faculty.” This culture was summarized in a graphic posted by the studentrun account @smfastudentsforfaculty, which stated that Tufts administration thinks “SMFA Studio Art Faculty are less valuable because we do not give enough reading and writing assignments… [and] do not spend as much time for course preparation… and [we] work less because studio art classes have in-class work time.”

boards they complete, has been instituted in its place.

This change, however, has had other impacts for PTLs. In order to both support their students’ learning and maintain their previous pay level, PTLs continue to conduct review boards. Noting that PTLs can only complete about five boards per day, John Ros, a part time lecturer at the SMFA and member of the Bargaining Committee and the Contract Action Team of the SEIU Local 509, explained that PTLs are forced to “come in [on] days they are not scheduled to teach” in order to complete review boards. An anonymous faculty member at the SMFA attributed this to a change in the academic calendar, from review boards occurring over the course of 10 days to only seven or eight days, which is not accessible to all PTLs and their work schedules.

Bedford noted their appreciation for meaningful feedback from PTLs during review boards. “I know I’ve definitely had review boards where the faculty kind of made or broke what was going on in the room,” they said.

A focal point of the PTLs’ platform is restructuring review boards, which are extended discussions of a student’s work at the end of each semester. Prior to the start of negotiations, the contracts of PTLs included compensation for the completion of eight mandatory review boards per course, with five review boards conducted per day. Recent negotiations have resulted in the requirement being dropped, and a pay-per-board policy, in which PTLs are paid on the basis of the number of review

PTLs, as Ros wrote, “find [the current review board structure] unacceptable due to other work, career or personal obligations.” According to the anonymous faculty member, there have been cases of PTLs not showing up to review boards, likely because of conflicts with their other commitments. Essentially, according to Ros, “the SMFA is asking us to become full time employees for two weeks out of the term,” despite their designation as PTLs. Ros stressed that the union has historically pushed for a more equitable schedule that would allow PTLs to “fulfill their required boards on the days that they teach.”

The pay-per-review board policy amounts to around a 16.6 percent pay decrease if no review boards are completed. This decrease reflects a restructuring in the pay for review boards. “It’s very crazy—the schedules that are asked of them during that time, across the board… and then [to] not… pay well for the service that they’re providing,” said Joy Bedford, a senior in the BFA program at the SMFA. Bedford also argued that the current system disadvantages students as well, stating that “all of the professor feedback is probably the most critical to students, but if they’re stretched so thin, they can’t commit their full attention because they aren’t able to get enough rest to recuperate for the next day.” They suggested some reforms, holding that the “review boards need a little bit more time.”

On the Medford campus, graduate student workers provide instructional and research services to students and professors and are also mobilizing to increase their pay. In a written statement to the Observer, Sam Alterman, a Bargaining Committee Member and PhD student from the Department of Physics and Astronomy, said, “Grad labor is central to the dayto-day functioning of academia, and our campaign for a living wage here at Tufts is part of a national movement of grad workers demanding that the multi-billion dollar institutions we work for treat us with respect and dignity.” Alterman asserted that that “Grad workers’ working conditions are our students’ learning conditions” and that Tufts University Graduate Workers Union is “fighting for a contract which invests in the human infrastructure of Tufts, ensuring that grad workers are paid a living wage and receive just benefits so that we can provide the top notch education our students deserve.”

In a written statement to the Observer, Bryan Rust, a Bargaining Committee Member from the Department of Mathematics, echoed these sentiments. “I don’t think anyone should be surprised then that graduate workers are demanding compensation commensurate with their work. I think what is unique to Tufts is the direness of the cost of living situation,” Rust wrote. Tufts graduate workers are paid significantly below the cost of living in the area, which is especially concerning “when compared to Tufts’ self-identified peers.” Similar sentiments were shared by the SMFA PTLs in their written statements to the Observer

In reference to the high number of negotiations occurring simultaneously, Brown contends that “the university chose

this timing,” as the administration asked the SMFA PTLs to postpone their negotiations until March 2023, when they had presented the aforementioned pay cuts. Matt Kalan, a Contract Action Team Member from the Department of Chemistry, explained in a written statement to the Observer that these negotiations have been especially contentious as the cost of living continues to rise aggressively in the area surrounding Tufts. The university’s lack of urgency in regards to the cost of living is making the struggle for corresponding adjustments to pay and benefits “a real fight.”

Along with the majority of Americans supporting union activity, Tufts has portrayed itself as a staunch supporter of bargaining rights. In a statement sent to the student body on August 31, Tufts Student Life reiterated that “Tufts respects the rights of all our employees… to engage in concerted, protected activity, including the right to unionize.” Members of the Tufts Labor Coalition, however, feel that Tufts University has falsely represented itself. “Tufts has bargained in bad faith, open[ing] negotiations by demanding a pay cut,” they asserted in a written statement to the Observer

This reflects the circumstances of grad students reported in a Campus Climate Survey conducted by the Office of Institutional Research at Tufts. According to the report, 75 percent of grad students selected “My basic needs are not met by my income” or “It’s tight but my needs are met.”

There have been many developments since the start of this recent bout of union negotiations. Dining workers had wins over the summer. The RAs recently passed their first contract, meeting many of their demands. Ros informed the Observer that on September 15, the university offered the SMFA PTLs a pay increase for the first time since recent negotiations began and a counter proposal that has reduced the number of required review boards from eight to five per course. Most recently, the members of TUGWU walked out in protest during the inauguration of Tufts’ newest president, Sunil Kumar.

Students on both the SMFA and Medford/Somerville campuses have shown support for unionized PTLs and grad students. Bedford attended a TLC-led teach-in at the SMFA about the PTL cause, where students discussed the union’s de-

mands and the realities faced by the lecturers. “You want to believe that the money that you pay means that you’re getting a better education, means that your educators are being paid well, and then to find out that that’s not necessarily true is like really upsetting to learn,” Bedford said. Bedford also appealed to fellow students for support of the PTLs, writing that “Getting involved as a student is super important and especially getting your parents involved is really important because… parents have so much power, like if they email the school and start to raise concerns,” the school would find it much harder to ignore them relative to students, “as they have previously and continue to do.” As the members of TLC wrote, “No contract negotiation, no grievance, no demand exists in isolation. Although it may seem that there are many ‘fights’ for respect and dignity by workers all around the country, this is one fight. This is everyone’s fight.” According to Ros, “Universities have long profited off the work of marginalized employees, creating a system of exploitation for profit. It is time for these practices to end!” O

“A dominant narrative that we often encounter as graduate students and workers is that we are supposed to struggle. Graduate school is hard and that’s just the way it is. Our professors struggled when they were graduate students so it’s completely normal that we are struggling as well,” said Casey O’Reilly, a Bargaining Committee Member from the Department of English. She went on, writing, “By fighting for a livable wage, we are fighting to alleviate the financial burden that so many of us bear in order to build a more welcoming and inclusive educational environment for graduate student workers from all backgrounds.”

to its prestigious reputation and commitment to quality education. When I was applying to colleges, I knew I wanted to attend a smaller university outside of California, where I had grown up. I aimed to experience a different location and culture, while receiving a toptier education. Despite being accepted by my state schools and other larger out-of-state institutions, I ultimately decided on Tufts after touring and discussing it with my parents. However, it’s hard not to question whether I made the right decision. This year’s annual US News Report on college rankings revealed that Tufts dropped from the 32nd to the 40th position among the best colleges in the nation. This ranking falls behind several universities including University of California Santa Barbara, University of California Irvine, University of California San Diego, Boston College, and University of Wisconsin. The recent ranking shift has prompted me to wonder whether attending an out-of-state school is worth the considerable extra expense, or if I should have chosen an in-state school after all.

It’s hard not to have the gut reaction that this ranking indicates a decline in the quality of our education at Tufts. While one can thrive in a college

By Lauren Langbort

with a lower ranking, students here have dedicated a lot of effort and financial resources to attend this school, hoping for a worthwhile return on our investment. However, despite this initial reaction, it is vital to remember choosing a college should be based on much more than rankings, and these rankings cannot begin to encapsulate an entire college experience. Students will be investing the next four years of their life living, learning, and growing at an institution, so the decision must be far more deliberate than merely following a numerical ranking. Ideally, a change in ranking should lead neither incoming students nor current students to doubt their choice of college.

This doesn’t mean that the Tufts administration should discredit the shift in ranking as meaningless. The 2024 US News rankings were based on adjustments to the calculation that emphasize inclusivity and accessibility factors. This drop should serve as a crucial wake-up call for the school to assess areas that need improvement. The aspects that led Tufts to decline in ranking have more to do with economic accessibility than academic quality; the quality of a Tufts education remains similar to previous years and still holds a respectable reputation. Therefore, while students shouldn’t let this ranking drop discredit their personal accomplishments, the administration needs to seriously re-

flect on ways it can improve accessibility for all students.

Tufts’ ranking over the past decade has consistently been in the high 20s or low 30s. This drop to 40th marks a striking difference from previous years and is attributed largely to adjustments made by the US News report in the way it assesses colleges. Alumni donations, proportion of students receiving government loans, high school standing, terminal degree faculty, and class size were removed from the calculation, while more weight was placed on factors such as the number of graduates receiving a Pell Grant, amount of debt, the proportion of first-generation graduates, and the post-graduation earnings of college graduates in comparison to high school graduates.

These changes reflect a shift in focus by US News toward inclusivity and accessibility as important criteria for assessing the value of a college education. It’s true that Tufts’ decline may point to a disparity in this criteria—the institutions that surpassed Tufts in the rankings are primarily state schools, which likely had an advantage in the new ranking system by being more accessible for in-state students due to their substantially lower in- state tuition costs. However, state schools are not a universally more accessible alternative, especially for students like me who

wanted to leave their home state for college. For instance, while the University of Michigan is comparatively affordable for in-state students, for whom the tuition is $35,450, it may not be affordable for out-of-state students who pay a tuition of $76,294. So how can a student really tell if the rankings indicate that a school is accessible for everyone?

Even so, Tufts is bound to struggle in this new ranking system, given its tendency to admit students from affluent backgrounds and lack of needblind admission policies. Historically, Tufts has one of the highest proportions of wealthy students among colleges. The school enrolls more students from the top one percent of the income bracket than the whole bottom 60 percent, and it gives less than half of its student population financial aid—40 percent in 2022. Tufts is less inclusive across socioeconomic classes than it should be, indicating a need for improvement. Considering that rankings are starting to emphasize accessibility, Tufts’ current management of admissions is leading them on a path towards consistent decline. If Tufts values a higher ranking, it is essential that the school takes the initiative to improve the admissions process, allowing people across a diverse range of socioeconomic backgrounds equal opportunity to be admitted to the university.

professor, Joe Hurka. These are just a few of the experiences that can’t be captured by college rankings. A number can’t capture the variety of classes, the range of clubs, and the relationships built. A ranking only reflects a mechanical perception of what counts as a top university. What it doesn’t consider is how you, as a unique individual with your own personality and interests, will fit into the university and what opportunities will truly excite you.

In conversations with other students, it is evident that many of them are also unaffected by the university’s ranking, believing it has not diminished the quality of their educational experience. Junior Kabir Pamnani said, “Tufts’ ranking dropping doesn’t bother me at all, because for me, I base my judgment of the quality of education on my own experiences. I am getting a great education with great professors, and I feel I am given the opportunities that any top school in the world is given, and so I don’t focus on rankings.” While rankings may influence the perceptions of individuals who haven’t attended the university or are unfamiliar with it, there are still those who have thoroughly enjoyed their time at Tufts and would vouch for the topnotch education and unique opportunities it provides.

of few students from the bottom 60 percent income bracket is a crucial indication that the institution must enhance its inclusivity efforts. This could potentially come from Tufts implementing need-blind admissions or removing loans from financial aid. These policies would alleviate the stress of student loans, which are one of the leading causes of debt for adults in America post-college. It’s disheartening to see our school’s ranking decline, in part due to the administration’s failure to provide sufficient need-based aid to prospective students. However, students shouldn’t dwell too much on the actual number of Tufts’ rankings. This drop says less about the quality of education and the experiences of current students and more about the university’s incapability to make Tufts an affordable option for students from all socioeconomic backgrounds.

Having said all this, as a student looking for a high quality education, I remain confident in my decision to attend Tufts. Unlike many other larger institutions, Tufts offers intimate class sizes of 20 students or fewer, providing the personalized learning environment I sought. Additionally, I tend to be shy and struggle to step out of my comfort zone; in a smaller school setting like Tufts, I’ve found it easier to connect with others, enabling me to explore new activities such as Burlesque, the Observer, and yoga class. Experiencing a more personalized education has allowed me to form friendships with some of my professors, such as my creative writing

Ultimately, when looking at rankings, it is important to remember that college encompasses more than just learning. It serves as a crucial opportunity for young adults to break away from their familiar environments and develop on their own, offering a safe space for self-exploration and facilitating the discovery of careers to pursue and activities to take part in. The college experience aids in shaping students into the kind of person they aspire to become, and a ranking cannot encapsulate the value of this transitional period that occurs at a school.

Instead, Tufts students should view this ranking drop as a clear signal that improvements are needed in the school’s accessibility. Tufts’ admission

The choice of college, or even the decision to attend college at all, is profoundly personal and cannot be reduced to a mere ranking. Each individual possesses unique characteristics and requirements, and what fits one person may not suit another. While students at Tufts can continue to find fulfillment in their college experiences, the recent decline in the university’s ranking should undeniably be concerning for the administration. This dip in rankings should serve as a compelling call to action for the Tufts administration, urging it to improve accessibility and ensure that our education and opportunities are within reach for a more diverse range of students, irrespective of their socioeconomic backgrounds. O

Yesterday, I witnessed the advent of another new Spotify campaign: “put your friends on to Hotline TNT through a collaborative playlist,” it suggested (an “indie shoegaze” band I, admittedly, like a lot). While collaborative playlists aren’t new to the platform, Spotify’s most recent effort encourages you to create collaborative playlists with the intent of “putting your friends onto culture,” placing each individual into a hierarchy of cultural knowledge and the artist within a hierarchy of cultural value.

like Spotify, Letterboxd, and Goodreads has prompted the commodification of that culture.

“It’s hard to have an insular and individual experience,” fourth-year dual-degree student Adrian Wong said. This is a shockingly plain expression of the structures that I seek to examine in this article. This newfound focus on individual consumption as a site of cultural creation is achieved through identity formation, in which the individual seeks to embody a commodified personhood. The encouragement

With artistic production now all but reliant on internet pathways to “exist” within a cultural canon, the platforms through which cultural products are spread influence the perceived merit and value of that art. This commodification of culture is propagated by socially oriented sites that focus on a single art form, like Letterboxd and Goodreads, as well as those offering both consumption and social engagement, namely Spotify. These sites of cultural-artistic identification are particularly prevalent in collegiate environments like Tufts, and, as Wong stated, they have “become platforms that build social cohesion.” They have reconstructed our collective cultural landscape in a way that reproduces bias, affirms hierarchies of cultural value, forms cycles of exclusion, and pushes art toward monoculture. Platforms like Instagram, Twitter, and Tumblr offer a point of entry through which people can broadly engage with cultural interests in the digital company of friends and rs. Another appeal is the ease with which they allow users to make connections. This is the consequence of suggested content, user algorithms, and forum-like comment sections that unite individuals through a shared appreciation of content. The content mediation that occurs on these platforms provides an initial value determination of all of the cultural output that passes through their doors. Furthermore, posting acts as a declaration of visibility—a proclamation of limits, which establishes what is allowable to us within a creative form, whether that be music, film, or literature—and in turn is essential to the processes of commodification and promoting monoculture.

By Spencer Vernier

Let us begin by examining two “socialized database” platforms, Letterboxd and Goodreads. These platforms tend to be popular among the arts-oriented crowd at Tufts due to what senior Mariana Janer-Agrelot described as, “an appeal to the brand of not being mainstream.” While each caters to a particular niche, Letterboxd intended for enjoyers of the silver screen and Goodreads meant for bookworms, each functions on a similar premise. These platforms amass an expansive archive of works (titles of movies and books in this case), creating an extensive database for users to access. The art within their collections is inevitably commodi fied by the platform-curator and then positioned within a cultural hierarchy of value. Letterboxd and Goodreads may not allow users to directly consume the content they focus on, but they streamline its critical assessment and cultural placement through their curation efforts, and as Wong said “you’re constantly inundated with what other people think.” This takes many forms, including themed lists, promoted reviews, or suggested films and books on Letterboxd and Goodreads. A prime example of the “consumption panopticon” is the presentation of a user’s top four picks on Goodreads, which senior River Smith described as being, “a deliberate process because I knew it was going to be the first thing everyone saw.”

This digital environment homogenizes cultural discussion and critique by promoting hierarchies of value and credibility, as well as a path toward uniformity, encouraged by the centrality of ratings and reviews on these websites. As Wong said, ratings and reviews on these platforms provide “an open field for people to compare taste and to see

who’s doing a good job of building their repertoire of knowledge.” A platform that allows users to view which works and user-critics are highlighted will always be swimming toward a monoculture because it profits from singularity—it is easier to promote oneness than complexity and vibrancy. This is exemplified by the marketing campaigns featured on these platforms, notably Letterboxd, which spotlights certain users or films both within the database itself and on other social media platforms. One example is the hegemonic presence of Karsten Runquist on Letterboxd, whose reviews consistently receive more attention than anyone else on the site. His YouTube channel is sponsored by the platform, and he operates in a “supposed central role” to Letterboxd’s dynamics, according to Wong. In the end, the celebrity of Karsten Runquist (and similar phenomena) demonstrates a tendency of companies to leverage cultural hierarchies in a way that, in effect, limits cultural consumption. Take Spotify—the monopoly the platform aims to have over the curation and consumption of music is indicative of its desired role in cultural commodification. Spotify produces an environment in which artists and their music lose all agency, with artists’ survival dependent on their cooperation with what Spotify deems worth promoting, such as marketable “subcultures” or trends. This is only exacerbated by the fact that, as Smith stated, “To exist as an account on a website like Letterboxd or Spotify means that you are creating content for that website, whether you’re aware or not.” I would add, you’re also contributing to its power; user engagement with Spotify’s version of cultural subgroups is essential to feeding its process. While the platform lacks total control over music curation and consumption, it has become essential to the music world. As a consequence, no matter

what musicians create, they must cede to the labels and commodities that Spotify wants to offer its customers. This is because art consumption, especially with music, has been shifted heavily to streaming and Spotify’s model compensates artists at a completely unlivable rate of $0.003 to $0.005 cents per stream. Currently, their payouts in no way provide anything resembling a living wage for artists, but finding success on the platform can lead to sold-out shows or merch success, which are far more profitable artist ventures. Furthermore, in a digital world that has placed the impetus on artists to self-promote to create awareness around their work, Spotify acts as a necessary evil which entrenches the struggles of non-confirming and innovative output. As a consequence, experimental and marginalized scenes are consistently pushed to the bottom rung of the platform’s hierarchies of value, unless they offer Spotify the opportunity to engage in a performative undertaking for “the good of the culture,” something my interviewees categorically indicated they did not care about.

The same dynamics are replicated in other sites of cultural consumption; for instance, film studios market their new releases with Letterboxd ratings in mind, and videos of directors or actors reacting to reviews are commonplace. As Janer-Agrelot told me, she is “always thinking about how many stars to give a movie” when she watches one, so the tactics are certainly working. Cultural output has become a marketable commodity, and creatives are increasingly dependent on connecting their work with a commodified identity by way of these platforms.

A positionality is being created which falsely propagates the idea that anyone can become part of the canon’s outlets of criticism, or that there is a meaningful awareness of the relation between the artist, their

work, and those who engage with that work. But the reality is that the new critics are the industries that capitalize on that art: record labels, film studios, publishing houses, and the platforms themselves. As with Spotify’s recent rollout of opportunities to advantage certain artists through paid promotion on the platform, the industry has recognized the potential that lies in how the ultra-curated nature of these databases have and will continue to transform the landscape of culture. Now more than ever, our connection with artistic-cultural output is being degraded into buying a commodified identity-product. Now, listening to Loveless and Souvlaki is a stand-in for real involvement in an independent music scene; watching A24 films serves as a cultural demarcation of being part of a group with “true” cinema fans (which often carries with it misogynistic intentions); and having read the entire works of Kafka is a signifier of advanced socio-cultural knowledge. What we choose to do in response to this flattening of cultural consumption into a product is what matters most. Buy your favorite artist’s records, go to the movies, ask a professor their favorite books— break free from the limits of these hegemonies and biases, break free from the patterns of monoculture, and find a new path forward that pursues the groundbreaking, the marginalized, the challenging, and all the possibilities they hold.

what remains of something in this world when it only exists in a photograph? when it burns in the hearth, unreplicated and unremembered?

destroying evidence while meticulously recording its existence, calculated and unforgiving, removing all trace, hair by hair by hormone until i fear being useless to them, to those who watch, waiting to feed jumping in for the taking, their teeth marking territory, feigning desire—or masking it they bite and kiss and say they didn’t mean it, that none of it was real. decide they hate the taste of blood only after i paint my lips red.

how even in trying to kill that which gnaws at my wrist, i feed it from my open palm.

how even that which i fear so deeply, i follow defenseless into the dark with my hands clasped tight at my sides, at my back—at its service.

how even at the very altar of my salvation, i kneel down and pray to the chains around my ankles, prisoner’s rosaries, take pictures of myself for them, make copies, take proof

of this wartorn body, conserved for an audience i wish would not exist, would chance past my ruins without a second look, never lay eyes on my skin but who in every act i serve even now—spectators unseen and unyielding.

how long can one hate something before they end up living for it? a moth to the flame, but with eyes clenched shut—crouching and covered in ash, terrified of fire but still hungry for warmth, digging bare-handed for embers.

deep in the rough rests a diamond, looking for strength in the rock, scratching its own likeness into its unfinished surface, deep enough to stay there long after it is polished, carved heavy—its very image a scar in its future.

a woman, still throwing herself into the fire hoping one last time to burn off the man, if only to save the ashes, to show everyone, to prove to them

how beautifully he burned.

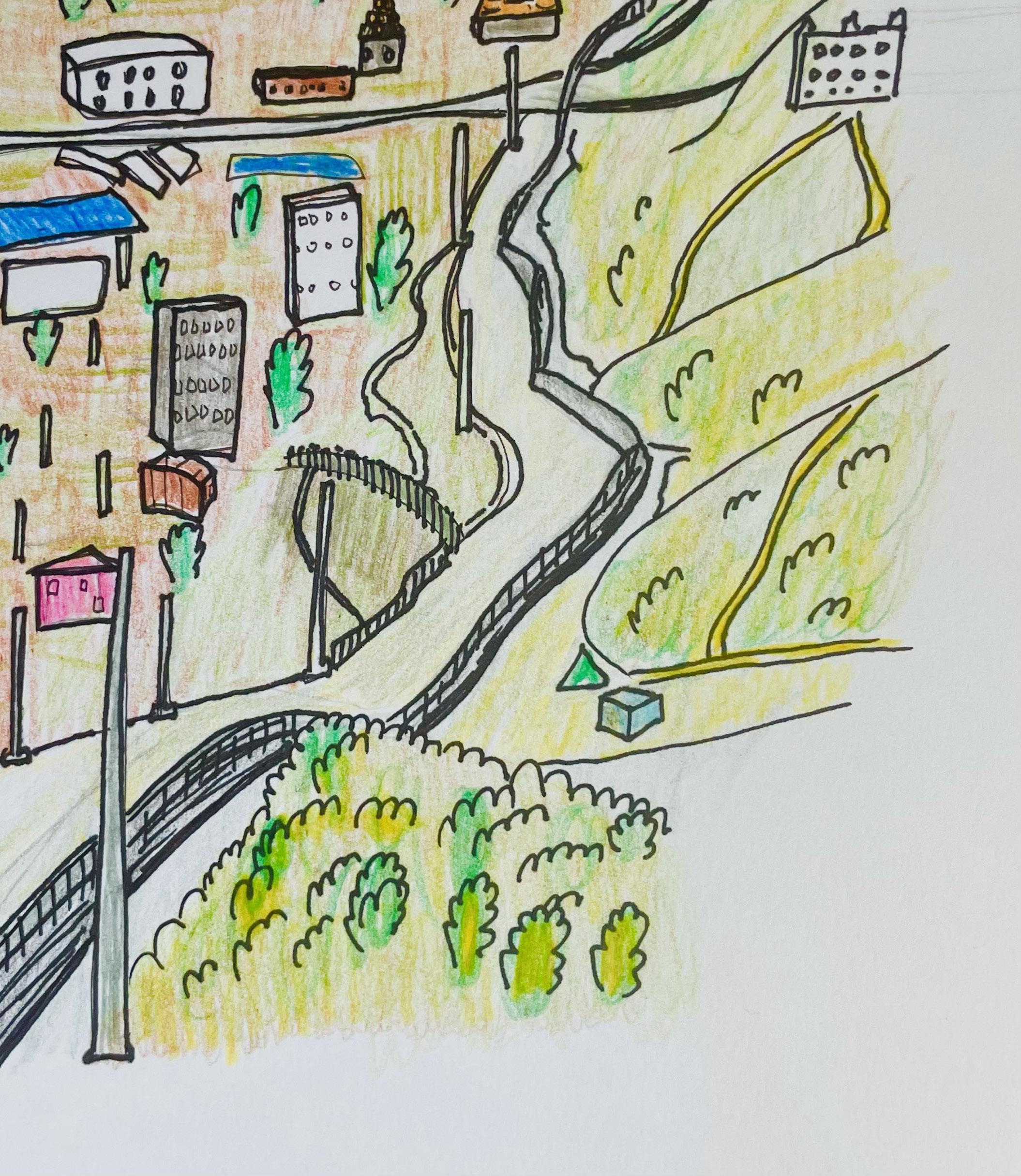

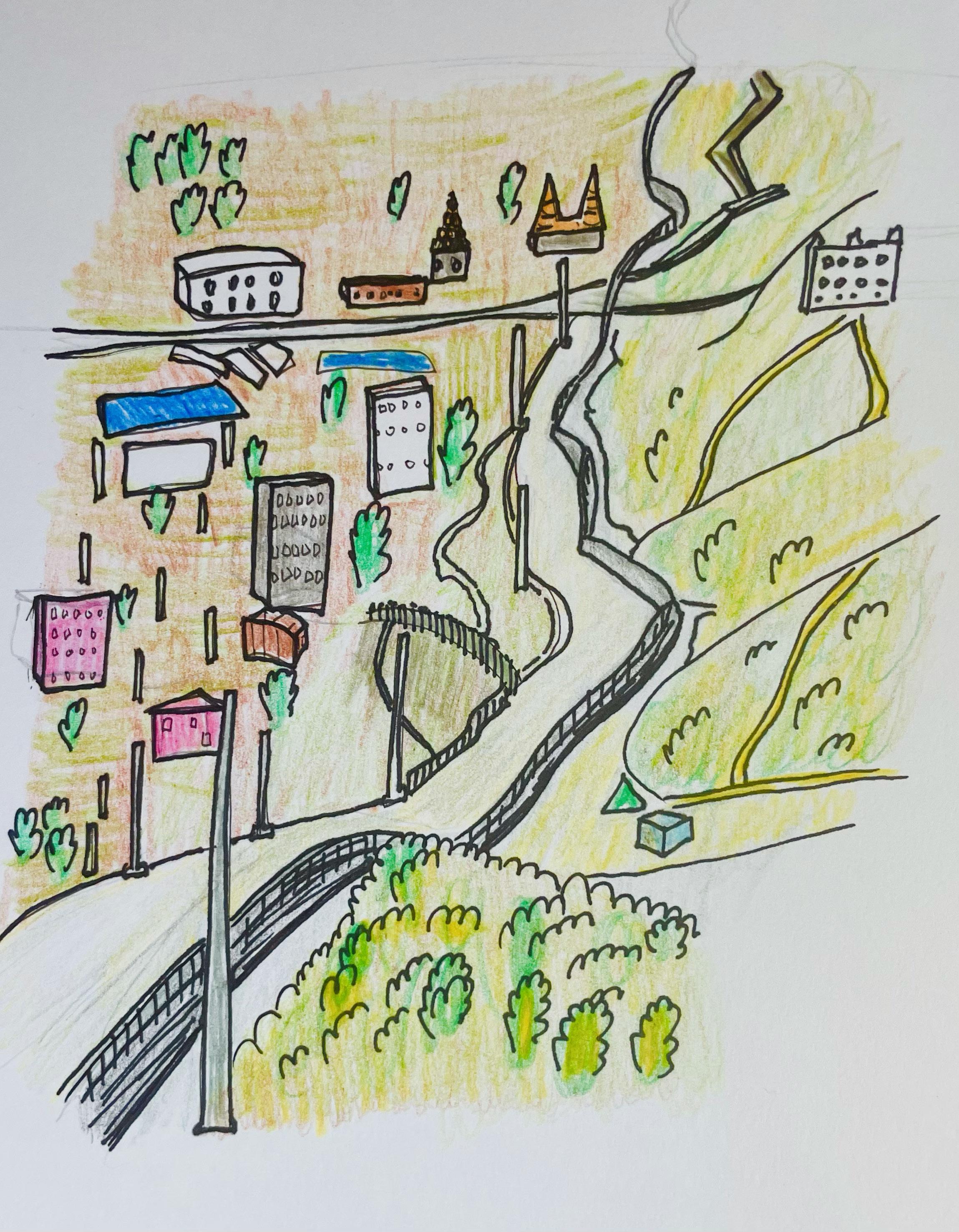

On October 5, 2023, the Biden administration announced a change to its approach towards the USMexico border wall that began construction under the previous Trump administration. The administration said it would build up to 20 miles of border barriers in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley, a confusing move given that, during his bid for the presidency, President Biden swore to never build another foot of the wall.

This isn’t the first time Biden has gone back on his promise, as the administration has already completed some other smaller sections of the border wall. However, this would be the first major segment to begin construction on Biden’s watch and is particularly notable since the

September 30, which forced the administration to fast-track the process to move forward with the construction given there was not enough time to negotiate a new deal. The new segments will cost about $140 million to complete, and among the 26 environmental and cultural protections the administration waived are the National Environmental Policy Act, the Endangered Species Act, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, and the American Indian Religious Freedom Act.

ing forces behind migration, however, provides insight into why border wall policy is as ineffective as it is harmful. “Most migration of folks into the US from a country, such as Mexico, is more so a reflection of conditions in the receiving country than anything else. So, labor market dynamics in the United States frequently drive the infusion of people into the country.”