rest issue 4 vol CXXXI spring 2023

TUFTSBSERVER

“WE HAVE TO TALK ABOUT FOOD”

Amanda Westlake

WHY ARE WE HERE, ANYWAY?

Nikhil Vootkur

THE PLEATS IN THE DRAPE

Eli Marcus

WE SHOULD FEAST.

Leah Cohen

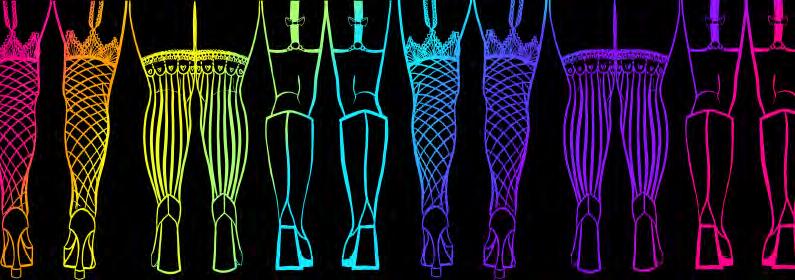

LET’S TALK ABOUT BURLESQUE, BABY

Kiara Mastropasqua

CREATIVE INSET

Ines Wang

PROOF THAT NOTHING IS REAL

Zed van der Linden ON LEARNING

Josephine Yip

SOMERVILLE COUNCIL TARGETS MEDICAL DEBT

Layla Kennington

COVERING PALESTINE ON CAMPUS & BEYOND

Tufts SJP

SLEEP IS THE MONSTER ON MY BED

Veronica Habashy

BETWEEN TWO CULTURES

Josephine Yip and Iris Yang

FEATURE 2 OPINION 6 PO & PRO 9 VOICES 10 A &C 12 ART 14 PO & PRO 18 19 NEWS 20 OPINION 22 VOICES 24 CAMPUS 26

TABLEOFCONTENTS

Editors-in-Chief

Melanie Litwin

Amanda Westlake

Editor Emeritus

Sabah Lokhandwala

Managing Editor

Juanita Asapokhai

Creative Directors

Angela Jang

Yimeng Lyu

Feature Editors

Ruby Goodman

Emara Saez

News Editors

Rohith Raman

Layla Kennington

Arts & Culture Editors

Sophie Fishman

Millie Todd

Opinion Editors

Michelle Setiawan

Clara Davis

Campus Editors

Liani Astacio

Eden Weissman

Poetry and Prose Editors

Neya Krishnan

Priyanka Sinha

Voices Editors

William Zhuang

Sarah Fung

Creative Inset

Ines Wang

Art Directors

Aidan Chang

Audrey Njo

Multimedia Director

Pam Melgar

Multimedia Team

Anika Kapoor

Megan Reimer

Juniper Moscow

Emmeline Meyers

Claudia Aranda Barrios

Brenda Martinez

Podcast Directors

Grace Masiello

Noah DeYoung

Publicity Directors

Ava Vander Louw

Sofia Valdebenito

Publicity Team

Anthony Davis-Pait

Emma Iturregui

Aatiqah Aziz

Staff Writers

Edith Philip

Leah Cohen

Billy Zeng

Ava Vander Louw

Sage Malley

Lily Feng

Siona Wadhawan

Hanna Bregman

Erin Zhu

Felipe Campano

Veronica Habashy

Joyce Fang

Bella Cosimina Bobb

Designers

Madison Clowes

Hami Trinh

Anastasia Glass

Jasmine Wu

Anthony Davis-Pait

Anya Bhatia

Aviv Markus

Maria Cazzato

Lead Copy Editors

Lucy Belknap

Eli Marcus

Copy Editors

Seun Adekunle

Kara Moquin

Alec Rosenthal

Drexel Osborne

Nika Lea Tomicic

Phoebe McMahon

Ashlie Doucette

Podcast Team

Emily Cheng

Ethan Walsey

Alice Fang

Megan Reimer

Soraya Basrai

Jamie Doo

Qinyi Ma

Eden Weissman

Staff Artists

Emmeline Meyers

Diana Gateño

Olivia White

Lydia Jiameng Liu

Heather Huang

Mariana Porras

Rachel Liang

Chileta Egonu

Zed van der Linden

Nour El-Solh

Matilda Peng

Maria Cazzato

Katie Rejto

Adina Guo

Website Manager

Clara Davis

Treasurer

William Zhuang

Contributors

Josephine Yip

Kiara Mastropasqua

Nikhil Vootkur

Josephine Yip

Iris Yang

John McKean

Tufts Students for Jutice in Palestine

STAFF

flutter your eyes on the day, just long enough to experience the electrifying clarity of a dream. take a napnot all problems are problems.

“WEHAVETOTALK ABOUT FOOD ” AT TUFTS, NOT ALL STUDENTS TAKE THEIR NEXT MEAL FOR GRANTED

By Amanda Westlake

As a first-generation and low-income student, junior Aaron Apostadero has dealt with food insecurity for a long time. Now, as the co-president of Tufts Student Garden club, he wants to address and raise awareness of the issue at Tufts.

“I’ve met people who deal with the same problem,” Apostadero said, noting food insecurity is especially prevalent among members of the first-generation community. But, according to Apostadero, although the issue impacts many students, “no one talks about it.”

Food insecurity, the inability to reliably afford or access adequate food, is an urgent problem at Tufts. A recent survey shows that both affordability and accessibility of food are prevalent issues. Out of the 516 undergraduate respondents to the Tufts Community Union (TCU) Annual Survey, 11.82 percent of respondents said they were hungry but did not eat due to financial constraints sometime in the past month. Furthermore, 26.32 percent of respondents said they were hungry but

did not eat due to a lack of access to food sometime in the past month. The university has recently taken steps to address food insecurity at Tufts with the formation of the Food Solutions Coalition last summer. The coalition, which consists of administrators, faculty, staff, and students, has worked on projects like the Swipe it Forward meal swipe bank, a grocery store shuttle, and providing food to students over school breaks. Individual students have also organized around the issue, such as Apostadero, who recently planned an event called Food Day that brought students together to discuss food insecurity on April 15. But Apostadero said he still doesn’t think most people at Tufts are aware of the issue, especially on a campus with a high percentage of wealthy students; as of 2013, 19 percent of students came from families in the top one percent of incomes in the US. “I know a lot of people who will never have to deal with these things,” he said.

SILENCE AND STIGMA

The persistent stigma surrounding food insecurity can make the topic more difficult to address. “If we are going to develop a more empathetic campus, we have to talk about food more,” said Professor Julian Agyeman, the chair of the Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts and a member of the Food Solutions Coalition.

Given the wealth of the student body at Tufts, some students might not feel comfortable publicly sharing their experiences with food insecurity. Sophomore Adrienne Mermin said, in her opinion, Tufts is “not a place where it feels totally normal to hear people expressing financial struggles.”

One of Agyeman’s students did a research project on two community colleges in the Boston area and how they dealt with food insecurity, which revealed the importance of addressing stigma. Agyeman said one college used an “under the table kind of manner” to supply food in a subtle way, while the other college “accepted the stigma and started talking

FEATURE 2 T UFTS OBSERVE R APRIL 18, 2023

about it with students.” At the second college, they found more students were using the provided food services, and the issue was essentially destigmatized. Agyeman said, “This is what I want to see more of—empathy and dignity being baked into food policies.”

Nicholas Stewart, a graduate student and Food Solutions Coalition member said that although universities like Tufts are considered elite, hunger still exists. He said, “These are places of great higher knowledge and great excellence, but within these infrastructures are still systemic issues that affect people. Access to food, access to housing, access to clothing… Those are basic needs that are not being met in intentional ways.”

For Agyeman, combating the stigma around food insecurity is essential to eliminating hunger at Tufts and beyond. “What we’re dealing with here is a very intimate personal issue that requires empathy and the centering of human dignity and the right to food as part of that solution,” he said. “Anything that falls short of that is doomed to fail.”

ON CAMPUS, MEAL PLANS DETERMINE WHO CAN EAT

When living on campus, most students purchase meal plans, which allocate a certain number of meal swipes each semester. First years are required to buy a premium meal plan, which includes 400 swipes. Sophomores on campus must choose between the premium, 220, and 160 swipe meal plans. Mermin called the options “very expensive, and not exactly conducive to students’ needs.” The premium meal plan costs $3,818 each semester, which she said includes “more swipes than you would ever need.” The next highest option, however, fails to provide even three meals a day.

For second-year dual degree student Ed Hans, a last-minute change in housing last fall left them without a reliable source of food. They originally purchased the 40-swipe meal plan, but when they were forced to vacate their off-campus apartment and move to an on-campus dorm, they ended up with too few meals for

the semester and no kitchen to cook in. Although they later tried to switch their meal plan, they were told it was already past the deadline. Director of Dining and Business Services Patti Klos wrote in a statement to the Observer that preventing students from changing their meal plan after a certain point is “necessary to ensure we have sufficient staffing” at the on-campus dining locations.

OUT OF THE 516 UNDERGRADUATE RESPONDENTS TO THE TCU ANNUAL SURVEY, 11.82 PERCENT OF RESPONDENTS SAID THEY WERE HUNGRY BUT DID NOT EAT DUE TO FINANCIAL CONSTRAINTS SOMETIME IN THE PAST MONTH.

This precarious situation took a major toll on Hans’ well-being. To make their meal swipes last longer, they would stay in the dining hall for hours and try to eat as much food as possible. When short-term aid ran out, they had to “beg” for more, sending email after email to the financial aid department. Hans said, “It was really stressful, only knowing two weeks in the future that I would have food… It made it way more difficult to just be a student.”

To find resources, Hans referenced the Tufts Food Resources webpage and ended up receiving short-term aid from two main sources: the unexpected hardship emergency fund and the Swipe it Forward program. The unexpected hardship fund offers up to $500 for students on financial aid, and Hans received $200 in JumboCash in early October meant to be used to purchase meals.

The next aid Hans received was from Swipe it Forward, Tufts’ meal swipe bank run by the FIRST center, Student Affairs, Tufts Dining, and the TCU Senate. Meal swipes are donated by both Tufts Dining and students. In the fall of 2022, the program was used to distribute 1,802 meal swipes according to a report released by the Food Solutions Coalition. Dean of

Student Affairs Kevin Kraft wrote in a statement to the Observer that because of the coalition’s work, the number of donated meals has “grown significantly” over the past year.

But the program, while useful, has limitations. Students can only donate a maximum of six meals each semester and receive a maximum of 10. Additionally, students can only receive donated swipes if they have less than five meals in their account, an issue Hans ran into when they knew they would run out of swipes soon but still had more than five. They finally received 10 swipes in late October, less than a week’s worth of food. The coalition seems aware that their donation may fall short of student needs; the report states they are considering “increasing the swipes allowed per donation and per request.”

Hans wondered why hungry students can’t just be let into the dining halls for free. They were especially angry at finding out that parents were allowed to eat at Tufts for free during Parents Weekend. Hans said, “If you could do that all along, why not let me into the dining hall?”

Throughout their time dealing with food insecurity, Hans didn’t feel like administrators were able to react appropriately to the urgency of their situation. “They were not hearing my human pleas,” Hans said. “They were just thinking, ‘That’s not in the system. We can’t do that.’” Hans did not receive a long-term solution until November, when their financial aid was increased enough for them to purchase sufficient meals to last them until the end of the semester.

OFF CAMPUS, GROCERY STORES INACCESSIBLE

Students living off-campus without a meal plan face different challenges when getting food. Local grocery stores can be difficult to access without a car, and even the stores that are close by often have high prices and limited selection. The problem is especially prevalent at a time when food prices are rapidly rising.

Upon moving into an off-campus apartment last year, Apostadero said one

FEATURE

APRIL 18,

TUFTS OBSERVER 3

DESIGN BY HAMI TRINH, ART BY AUDREY NJO

2023

big challenge was the new time commitment that came with buying and preparing food. He compares prices at different grocery stores to try and find the best option because “it might be only 10 cents, but 10 cents matter.”

Bfresh and Neighborhood Produce are relatively close to Apostadero’s house, but culturally accessible supermarkets are further away. “I’m not going to get Asian ingredients at either of these grocery stores,” Apostadero said. “So I have to go all the way to Central Square to go to the H Mart to get them, and I don’t have a car.”

Because local grocery stores can often be inaccessible, TCU Vice President and Food Solutions Coalition member Arielle Galinsky began a pilot program to help students get to the Wegmans in Medford more easily. The shuttle ran every Thursday and Sunday for five weeks from February to March. Galinsky believes the program was successful, effectively “heightening access to nutritious food for lower costs for students.”

Administrators have indicated they would like the program to continue. Kraft wrote, “We expect to continue to offer a shuttle to a grocery store next year. Details about the frequency and schedule are being finalized.”

FOOD JUSTICE, FROM THE ASIAN AMERICAN CENTER TO A NEW COMMUNITY FRIDGE

Just inside the door to the Asian AmJust inside the door to the Asian American Center, a bulletin board labeled “affirmations” holds a scattering of sticky notes left by students. Five of these notes contain some variation of “Food will come back to the AAC.”

During the 2021–2022 school year, a community food supply at the Asian American Center provided meals to anyone who needed them. The food occupied a few small cabinets in the AAC kitchen and quickly became popular. However, according to AAC Associate Director Emily Ding, it was unsustainable. Ding said, “The food that we refilled would disappear quite immediately.”

The program was possible in part because of COVID restrictions at the time, which limited the amount of food that could be served at AAC events. The AAC redirected this budget into the community food supply—buying rice, spam, and frozen meals at Costco to supply students with 217 portions of food throughout the year. But when the Center applied for additional funding to continue the food supply the next year, the request was denied. When asked why this request was denied, Kraft wrote, “In order to ensure that all students have access to food resources, the AAC partnered with the food solutions coalition to create a more robust resource accessible to all.”

26.32 PERCENT OF RESPONDENTS SAID THEY WERE HUNGRY BUT DID NOT EAT DUE TO LACK OF ACCESS TO FOOD SOMETIME IN THE PAST MONTH.

Ding said that because the food supply was such a success, students and staff began to unrealistically expect that the AAC and other DSDI centers could fill the gap left by food insecurity. However, the AAC food supply was only ever intended to be a short-term resource, not a systemic change that could meaningfully address food insecurity on campus. The centers are already underresourced; at the AAC, Ding said that while the Asian population has been growing on campus, the center’s budget and resources have not increased proportionately. Ding said, “We only had two staff at the time, and we already are pulled in so many directions.” All of these factors contributed to the lack of resources to sustain the food supply.

Now, Ding, Stewart, Galinsky, Klos, and others on the Food Solutions Coalition have been working on a new project, one that takes the burden of feeding students away from the AAC and puts free food in one centralized location: Jumbo’s Community Fridge.

The new community fridge and unstaffed food pantry will bring free food directly to the Medford campus. The project has been heavily supported by Tufts Dining, and Ding said the coalition hopes to launch the fridge before the end of the semester. The fridge and pantry will be donations-based, although Ding and others have discussed Community Supported Agriculture farm shares as a future option. Kraft wrote, “This will be a pilot program that will run for one year and be re-evaluated. We are also considering initiatives in a variety of areas to help further expand food access in our community. Ideas and suggestions from everyone at Tufts are welcome.”

Stigma was a significant concern for Galinsky when planning for the upcoming food pantry. She said, “One of the big concerns and thought processes when planning for the food pantry was: how are we going to find a balance between students wanting to use the pantry without feeling stigmatized that they need access to it?”

In her work, she wants to not only address food insecurity, but change how people talk about the topic at Tufts. “How do we have all these initiatives while completely redefining how food security is thought of and considered at Tufts?” she said. “Because ultimately, there should be no stigma attached to being food insecure.”

FEATURE 4 T UFTS OBSERVE R APRIL 18, 2023

FEATURE

APRIL 18, 2023 TUFTS OBSERVER 5

DESIGN BY HAMI TRINH, ART BY AUDREY NJO

W H Y ARE WEHER E , ANYW AY?

The state of academia amid an ever-strengthening careerist milieu.

By Nikhil Vootkur

By Nikhil Vootkur

6 T UFTS OBSERVE R APRIL 18, 2023 OPINION

As Fall 2023 courses were released, I sat in Hotung Café browsing SIS on my laptop, which rested precariously atop our beloved, wobbling tables flanked by Emeco Navy chairs (a military industrial project designed for use in naval ships and prison interrogation rooms). I selected my major, Race, Colonialism, and Diaspora, from the dropdown menu. While the search results buffered, I briefly scanned the surrounding landscape: the usual crowd, clad in Carhartt and thrifted boxy knits, Yerba Maté in hand, was momentarily replaced by a herd of sophomores and juniors in business casual, awaiting their coffee chats with representatives from the likes of consulting firm Bain & Co., which would be hosting its annual spring presentation that coming Thursday. This presentation, chiefly recruiting students interested in consulting, floated inconspicuously among the week’s preprofessional milieu, which included a Communications and Media Networking night, Pre-Health Interview preparation, “Wall Street Prep” (described in a Career Center email as “a M&A and LBO Modeling Boot Camp”), and the University’s “Law Day.”

Back on-screen, the SIS results page was populated with just 14 course offerings in studies of RCD—including an introductory lecture, two thesis writing blocks, and a capstone course. For students who are neither brand new to RCD nor nearing their graduation, this leaves only 11 course offerings. Both Asian American Studies and Latinx Studies do not have courses or full time professors who will be here in the fall. Including a for-credit internship and an independent study, American Studies offers four courses. Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies has 16 courses available (again, four of which are for thesis work, independent research, or an in ternship). Even English, one of the more established hu manities departments, has just 39 courses which are catered to undergradu ates, and an additional 13 graduate and doctoral courses. History, Sociol ogy, and Anthropology lack course breadth too,

with 40, 27, and 21 undergraduate offerings for Fall 2023 respectively.

More careerist degree tracks, which feed into jobs ranging from finance to IT, sing a different tune. There are, of course, the liberal arts majors, such as economics, which are more pre-professional than academic and feed into the likes of software conglomerates, biotech companies, and consulting firms. Students majoring in economics ( a go-to major for those interested in a job at Bain, for example) at Tufts may enjoy their choice of 64 courses for the fall. Computer science majors may choose from 65, and biology majors from 61. Not all STEM tracks are this fortunate, though; more academia-oriented STEM majors trend towards having fewer course options than their pre-professional counterparts. Such is the case for math, which offers just 36 courses for undergraduates this fall, including introductory and core credit-bearing courses (which are catered largely to non-math majors).

These statistics exist against a frightening landscape for pursuers of the humanities, academia at-large, and the generally corporate-averse. Tufts reports that for the 2022–2023 year, humanities majors do not make up any of the top 10 majors, which comprise an aggregate 64.8 percent of the undergraduate community. In 2022, considering first, second, and third majors, Tufts awarded just 31 English diplomas and 30 for history of 1,914 total awarded majors. Philosophy and Religion

At Tufts, the 10-year trend is not optimistic: wholesale arts and humanities diplomas have decreased by 33 percent since 2011. Anthropology, international relations, and political science diplomas have decreased by 30 percent, 46 percent, and 33 percent, respectively. Simultaneously, graduating economics majors experienced an 116 percent increase, biology increased by 155 percent, and computer science increased by 634 percent. The university also expanded programming in entrepreneurship and business alongside the recent opening of the Joyce Cummings Center, our on-grounds, brightly lit Memphis

In his New Yorker essay “The End of the English Major,” Nathan Heller writes about what he describes as a “freefall” within the study of the humanities. Heller ping-pongs between the academic tableaus of Harvard College and Arizona State University. At both, he shares, students feel discouraged to concentrate in the humanities, citing concerns over losing college. Undergraduate tuition has skyrocketed and continues to approach a six-figure mark for annual payment, the middle class continues to dwindle, and at the elite universities, Tufts included, students are surrounded by peers in the highest income brackets. It is no surprise, then, that there exists a conscription apparatus—exploitative and chiefly targeting those who need to make money back immediately—at these universities which pushes students to pursue the tracks that make them immediately hirable. This is what students colloquially refer to as “selling out.” But selling out, as one would have it, is the best way to secure a return on investment (an investment, again, that is becoming increasingly out of reach). As one Harvard student shared in an interview with Heller, “My parents, who were low-income and immigrants, instilled in me the very great importance of finding a major that would get me a job— ‘You don’t go to Harvard for basket weaving’ was one of the things they would say.”

Perplexing, though, is that, per Heller, even the wealthy and privileged at elite schools are walking away from a path in the humanities. The simple argument is that for those who need it, the economic comforts which stem from lucrative careers (think military engineering con-

OPINION APRIL 18, 2023 TUFTS OBSERVER 7

DESIGN BY ANTHONY DAVIS-PAIT, ART BY MARIANA PORRAS

tracts, corporate law, consulting, or a stint at Google) render the humanities undesirable (if STEM makes you rich, then the humanities will make/keep you poor). However, there seems to be a uniform distance that students of all socioeconomic backgrounds are taking from the humanities, and this becomes puzzling. The economic pressures of attending college, I believe, corrupt the American university in two crucial ways. The first is that universities much like Tufts, which were founded on and continue to regard themselves as beacons of scholarship and ideation, lose their penchant for enhancing the production and consumption of knowledge. The liberal arts university, once an idyll of knowledge exchange happening everywhere from the lecture hall to its leafy paths, no longer feels oriented toward scholarship, academia, learning

This brings us to the second problem, the American labor milieu. On campus, a familiar and omnipresent truism ostensibly rings, “you just can’t work without a degree,” and it’s becoming increasingly clear that the undergraduate diploma is no more than an entry ticket to one’s place in the white-collar workforce. Consequently, a process of extraction has emerged; as tuition fees increase and undergraduate education (and, in some cases, graduate education, too) is rendered a mechanism for career placement, students are incentivized to extract as much capital as possible out of their (increasingly expensive) college years. As students find it harder to rationalize non-lucrative careers, their natural and valid desire for post-collegiate

stability takes the wheel. In response, the elite university, therefore, has abandoned its scholarly roots to become a white-collar trade school.

A trigger-happy response to arguments like mine (that universities are deprioritizing the humanities and other academia-oriented disciplines) is to claim the root of the problem is not systemic, but a lack of interest in those fields among current students and high school applicants.

An interrogation into the sources and external influences for these very interests suggests that this may not be as much of an organic cultural shift as it may seem. It does not help that the US government, once a boon to the humanities at a national level—pouring billions of dollars into education in the humanities (in all 50 states, K–12 schools, and the private and public domains alike) from the middle of the twentieth century to just before the 2008 economic crisis—has now turned its attention toward STEM (recall, if you can, the CODE.org posters in your middle school with the faces of Mark Zuckerburg and Barack Obama). This nationwide priority shift bleeds into the private institution, too. In 2016, Tisch College at Tufts received 15 million dollars and was rededicated to the study and promotion of civic life. Five years later, the university received 90 million dollars to open its Joyce Cummings Center, and with it, give more attention to computer science and entrepreneurship. These funds appear to be funneled into the careerist STEM, economics, and entrepreneurship departments—conversely, the older, grayer buildings such as Braker Hall and the once-set-for-demolition Lincoln Filene Hall are relegated to those lesser departments, like anthropology or RCD. These fiscal and material markers directly signal to students what is important to the university and to the state, and, subsequently, what will help one accrue wealth and achieve stability in the “real world”— who could say no to that?

I am brought back to thinking about the state of affairs for the Race, Colonialism, and Diaspora department and the SIS results page that started this whole inquiry. The dialogue and scholarship coming out of RCD and other interdisciplinary majors including Asian American studies, American studies, Africana studies, Latinx stud-

ies, and WGSS is becoming increasingly relevant in our American socio-cultural landscape. Affirmative action will inevitably be scrapped; critical studies of race are being threatened across the country; anti-queer and trans legislation continues to proliferate; and the reproductive autonomy of women is diminishing nationally. Simultaneously, crucial ethical concerns over the widespread application of generative AI tools including GPT and DallE have emerged. All of these issues, which occupy more and more space in the American discourse, require answers rooted in ethics, identity, and general study of the humanities. Liberal arts colleges and universities like Tufts were once dedicated to these scholarly pursuits, and were acutely aware of the societal gravitas and potential for problem-solving that these areas of study have.

Such was especially the case here. The story of Tufts’ founding as described on the Tufts Admissions website goes like so:

As local lore has it, when a relative asked Charles Tufts what he would do with his land, and more specifically with “that bleak hill over in Medford,” Tufts replied, “I will put a light on it.” In 1855… Rev. Hosea Ballou 2d… the college's first president, remarked, “For if Tufts College is to be a source of illumination, as a beacon standing on a hill, where its light cannot be hidden, its influence will naturally work like all light; it will be diffusive.”

We are currently faced with a critical, albeit provocative, question: Why are we here? What is the fundamental, teleological purpose of our four-or-so years on the Hilltop? The status quo appears to suggest that the undergraduate experience is merely a stepping stone to the workforce, perhaps disinterested in producing new knowledge or pursuing scholarship, and most certainly abstaining from critical studies of the self and our global contexts. However, I believe that our purpose here is much greater than the jobs we may secure after graduation. By rededicating itself to scholarship, Tufts may once again become an idyll of knowledge exchange, the diffusive source of illumination it had at its origins sought to be; for we are here to learn, and how lucky are we to do that.

OPINION 8 T UFTS OBSERVE R APRIL 18, 2023

the pleats in the drape of my tragic disposition where my love hides

By Eli Marcus

a broken lamp taped together in the corner of my room summer bugs at night when leaving a lover’s car while the inside light is on and the door is open—say, in August persimmons, plums, pomegranates the nothing after a morning started in the afternoon

a melodica from my father (from his) from Germany children on asphalt, dipped in chlorine and drying in radiation wind against wet hair, frizz that follows three hats—lilac, ochre, moss—all crocheted six months apart the wearing down of the inside of my right shoe, the sole pulling away at the heel the way hot oil turns white onion translucent, the way soap cleans day from hands

POETRY & PROSE

APRIL 18, 2023 TUFTS OBSERVER 9

DESIGN BY ANASTASIA GLASS, ART BY ZED VAN DER LINDEN

WE SHOULD FEAST. WE SHOULD FEAST.

By Leah Cohen

Content Warning: Mentions of disordered eating, complex relationship with food, and body image

The secret to a good salad is to finely chop mint, basil, or any herbs you can get your hands on to use as lettuce greens. Adding a bitter leaf such as radish or carrot greens can do wonders in an oily vinaigrette. Kale can be made edible by ribboning it and soaking it in lemon juice or another acid and giving it a good olive oil massage. Don’t skimp out on cheese. A mixture of hot and cold adds complexity. Try crisping some chickpeas as a crunchy garnish, or starching it up with some chilled pesto pasta. When in doubt, aim for more alliums and spices, not less. I’ve never known a guest to complain about a dish having too much flavor.

There was a long period in my life where sections of the above would deeply terrify me. “Massage in some olive oil.” How much? A tablespoon of olive oil is 119 calories. That’s 10 minutes on the treadmill. “Don’t skimp out on cheese.” But cheese makes me so bloated. Maybe I can swap it with some tahini. “Starching it up.” Absolutely not. I have a performance tomorrow.

These are the woes of a person I only halfrecognize now, like a face in an overexposed Polaroid or a murmur in the background of an old home video. Of course, sometimes she creeps back up behind me to adjust the fall of a new dress, jut out her chin in the mirror with a dash of angst and dismissal, or pinch and prod at the pores on my chin and nose and thicken the hand of cream contour that hollows my full cheeks. She still sleeps at the foot of my bed, sometimes to suggest I stay in my oversized sleep shirt on the days I feel least myself. She follows me into the bathroom and won’t leave me alone for hours at a time, when the work begins to pile up and I see my friends and family less.

I used to love how good I was at scarcity. I was so skilled at refusal; I would reward myself

for being good at saying no by saying no even more often.

In my last year of boarding high school, I got really into going to the gym. I carefully crafted a very specific workout routine that coupled perfectly with three playlists, comprised of songs for which the beat and tempo corresponded with a deliberately selected rep in my abs routine or with oscillating high intensity intervals on the treadmill. The gym had a row of treadmills facing the grand bay windows, and I would run until all the air had evacuated my body, leaving me hollow. I’d watch from behind the glass as my friends went on evening walks, slowly skateboarded to and fro, laughed and joked and did homework. I’d grimly gloat to myself about how I would never be so childish as to indulge in a moment of rest. One time in a theater class, one of my teachers said in front of all of my peers that my performance work was not worth his time. I walked out of class and straight to the gym, where I ran for two hours straight. I had never felt more powerful and more empty. The only person I could count on was myself, and I was slowly letting that person atrophy.

It was fine because everyone was doing it. My friend Jamie had developed a diet of exclusively pineapples chunks, cinnamon, and cottage cheese; my friend Lisa joked about my new celery fixation because Jamie’s boyfriend had told me it was negative calories; we all got really into making these low-calorie tofu and rice bowls on the cafeteria hot plate that semester. I made imitation cookie dough out of peanut butter, greek yogurt, and sugar-free chocolate chips, a recipe I had seen on Instagram, and lied through my teeth about how great it tasted.

After a high school career spent getting better and better at feeling bad, I arrived at college and was assigned to live in a single. Everyone congratulated me and told me how

VOICES 10 TUFTS OBSERVER APRIL 18, 2023

jealous they were, while I mourned the loss of a built-in lunch buddy. It was exhausting to text a new person you met six days ago every time you needed to go to the dining hall, so you didn’t have to sit alone. I decided I’d rather just sit and watch Bojack Horseman in the dark under my weighted blanket. I wished for something to rescue me from the loneliness and figured I could kill the feeling by giving it less of a body to feed on. I shrank into myself. I sent mirror selfies in crop tops I’d never worn in high school to my old friends because I was too self-conscious; they’d send back “omg, you look so good!” I was disappearing in front of them and it was a major slay.

Every once in a while, I worry that I wished a little too hard for a lifeline out of that Carmichael single, because right when I was getting to the point of seeing sparkling silver fish flash across my vision every time I stood up, school was evacuated and the world transformed around me. Two months of a projected pandemic homestay turned into over a year of dinners with my dad, and only my dad. My dad and I decided to make the most of New Hampshire’s stunning summer and abundant outdoor dining, and sought out the best (and most pandemic-safe) lobster rolls in New England. On weeknights, he churned out recipe after recipe, putting a hot and delicious meal in front of me every night when I logged off from my remote jobs at various political nonprofits like I was the Queen of England. I started to remember how good it felt to chew, how lovely garlic and onions smelled, and how much I enjoyed the oscillation between flaming hot sauce and the soothing starch of bread and potatoes. I filled my plate with pasta and homemade red sauce and our quiet and isolated home with chatter. I was making up for lost time, for a childhood I stole from myself by focusing on the singular goal of slimness. In hindsight, I think my father was also making up for missing out on my descent into self-induced starvation, a tactic of control I learned from my mother.

When it was finally time to come back to Somerville, I found a house with robin’s egg walls, big windows that caught the mid-afternoon light, and an unusually large kitchen. I love my dad and his cooking, but I longed to try my own hand. I also had a lot of friends to catch up with after a year of separation, so I in-

vited everyone to my oversized kitchen table. I demanded everyone’s presence on Friday and Saturday nights and planned elaborate meals that began with decadent cheese boards and experimental cocktails and rounded out with hearty stews and spicy stir-fried noodles. Of course, I also demanded feedback. I learned to replace the satisfaction of being the best at starving with the smugness of being the best at feeding others. I knew my food tasted good, but what I wanted more than to be a good cook was to be a good caretaker. I wanted my friends to be able to count on me to care for them. For the first time in my life, I wanted to be solid, full, and stable. Feeding my friends became my form of community care, and through my desire to help others feel full, I filled my own plate.

Lately, I’ve been trying to choose a mind set of abundance. It’s not easy. I find ways to cheat myself regularly. I have to pause when I find a new recipe to fixate on—do I love the way it tastes, or do I love the way the TikTok influencer who taught it to me pitched it ca lorically? Do I want to bike to work because the weather is lovely or because I feel like I haven’t met my goal? Can I peel my eyes away from my Apple Watch step count? Do I really feel the health benefits of drinking psyllium husk powder? And I do enjoy simple vegeta tive recipes, and I do feel better when I get some movement in my day, and perhaps I don’t enjoy the taste of psyllium but I certain ly feel the effects of a plentiful fiber intake. It really is a constant balancing act—like craft ing a perfect meal.

I had to stop waiting for the day to fi nally come when I liked my body and instead choose every day to love my life enough to fill it with community, memories, and delicious food. My friend Celia texted me last month asking for my perfect summer salad recipe, a meal I shared with her in July that she referred to as “life-changing.” There’s a few more steps I forgot to mention—sundried tomatoes can bring dressing to life and pickled veggies add a tangy twist. But the real secret to a good salad is someone to share it with.

VOICES DESIGN BY JAZZY WU, ART BY KATIE REJTO APRIL 18, 2023 TUFTS OBSERVER 11

LET’S TALK ABOUT BURLESQUE, BABY

By Kiara Mastropasqua

Afrenzy commences backstage as dancers scurry around the wings of Cohen Auditorium in lingerie. Nerves and excitement permeate the air; the audience waits to watch friends and peers on stage. The lights dim, the crowd hushes. Then: lights, music, bodies on stage. Cheers erupt, the show begins. Dance after dance takes the stage, each one a different theme. It is the night of the Tufts Burlesque Troupe showcase. It is electric.

Burlesque is a dance performance and art form in which performers combine explosive components of costumery, dance, comedy, and theater, all while centering nudity or lingerie. As the art form has evolved, burlesque has come to challenge the conventional, calling into question gender politics, the perception of sexuality, and the public’s gaze on the naked body. According to HuffPost, Burlesque’s historic roots date as far back as the 1840s, associated with America’s minstrel culture. A new form of leisure at the time, burlesque shows incorporated familiar aspects of song, dance, and performance into a reimagined type of entertainment. But the version that is popular today—a combination of vaudevillian humor, dance, and striptease—arose in the early 1900s. At that time, mostly female performers took to clubs and Broadway venues to

create a new vision of music, dance, and nudity. Burlesque has become a nightlife and cultural staple for all to consume and experience.

The Tufts Burlesque Troupe’s popularity is reflected both by attendance of the show, which always sells out in minutes, and sign ups to join dances— sign up lists fill up shortly after their release. It is a non-audition group, which means anyone can join, creating a space on campus for all those who want to dance and experience the community that is Burlesque. The club is student-run with an executive board of eight people; membership consists of 300 students who are part of dances choreographed by other members. Senior and Tufts Burlesque Troupe Co-President Nyssa Singhal attributed Burlesque’s popularity to its uniqueness. “There’s no other club where you dance in your underwear,” she said.

Abigail Pomeranz, a senior and Burlesque choreographer, said a unique aspect of burlesque is the versatility. “It can look like a lot of different things, like when you go to the show each dance is really distinct, and it can be really fun and goofy,” she said. “It can be more serious and slow and sensual. It really runs the whole gamut.” This attracts people to the group, as it becomes a space anyone

can make their own while also providing community among individuals trying to cultivate a safe space to build confidence and try something new.

Many Burlesque dances are open to all, but some serve as affinity spaces where people of specified identities can come together in a safe space. Some of these affinity spaces include Queer and Femme POC, Genderqueer, Trans, BIPOC, and BIPOC Femmes. As treasurer of the organization, Clarissa Garzon said affinity spaces within the troupe allow for “everyone to find a group within Burlesque and know that we all have the same mission that we bring to the space.” Garzon described Burlesque as being a “super gender-affirming space” within the identity-based groups due to being surrounded by accepting or like-minded individuals. Junior Lacey Walls, a dancer with Burlesque, said the first dance she joined was a “queer affinity space, which I was looking for [in order] to get out and meet more people in the community.”

Burlesque is not something offered on many college campuses, making it an even more unique opportunity at Tufts. Established in 2007 at Tufts, Burlesque was created with the intention of bringing empowerment and sensuality into the Tufts arts and dance scene, allowing students to

12 T UFTS OBSERVE R APRIL 18, 2023 ARTS & CULTURE

express themselves sexually and providing a comfortable and supportive setting to do so. Walls said, “Burlesque really [shows] that you have these opportunities at Tufts that you’re probably never going to have again, encapsulating how Tufts’ [campus] really allows students to build their own spaces and make them their own.” Pomeranz also noted that the space offers every student “a chance to explore their body and feel really confident in their body and movement and sexuality, in a way that’s also really normalized.” The reception and support of the Tufts community also plays a role in the experience that is Burlesque, continuing to perpetuate popularity and support.

Singhal spoke on the core values of Burlesque, describing it as a way “to give amateur dancers or people who want to dance a space where they’re united over either speaking positively about your body or respecting your body or just coming together to acknowledge that your body is awesome and it carries you through your day.” Burlesque plays a crucial role on campus for participants and viewers alike, providing a space for “gender positivity, body neutrality or positivity,

and sex positivity,” as Garzon said. Garzon said the intention of the performance is “normalizing in some ways bodies in general. We’re just here in our bodies and we should all be able to feel good and honored and respected in them.”

The day of the Burlesque show—a cumulative showcase of all the dances— is for many a time of nerves, excitement, and pure energy. Two e-board members, Singhal and Garzon, recounted the amount of work that goes on behind the scenes: discussing the logistics of selling tickets, reserving rooms, and coordinating people—a much more intensive and exhausting process than others may be aware of. Pomeranz said, “It’s unbelievable how much it comes together at the end, but it can feel really chaotic. In the last two weeks, together with costumes and with dress [rehearsal] and everything, people start to get really comfortable and confident in what they’re doing.” Discussing show day, Walls said, “Once you’re out there, it always goes by in the blink of an eye. It’s so fast, like every single time I feel like I can’t remember what happened as soon as I step off the stage.”

Burlesque and the community cultivated within it are important to Tufts students. Pomeranz expressed gratitude for the space and community of Burlesque on campus, and said, “For me, it has been an incredible space where I really have found so much more peace with my body and love for my body.” Through providing a space to learn about oneself and others, Burlesque fosters community inside and outside the organization. Garzon said, “I’ve learned so much about myself along the way and met so many cool people along the way. I’m always thinking about my choreos that I had a year ago and how they’ve totally shaped and changed my time here at Tufts.” Burlesque serves a formative role for many Tufts students in fostering a space for community and visibility. As Walls said, “The people who do Burlesque are putting themselves out there in a way that I think is really admirable and doing that all as a community together.”

APRIL 18, 2023 TUFTS OBSERVER 13 ARTS & CULTURE ART AND DESIGN BY MARIA CAZZATO

REST REST

REST REST

or movement in order to relax, refresh oneself, or recover strength.

cease wo rk

DESIGN BY INES WANG

verb

DESIGN BY INES WANG, ART BY MARIA CAZZATO

Proof that Nothing is Real and the World is a Giant Fish

By Zed van der Linden

I can’t stop dreaming about him. I don’t dream a lot—mostly because I don’t sleep a lot—but when I do, and when I can remember that I do, it’s always him.

In one, we were getting married.

I was sitting in a strange hotel room with my dad, desperately trying to delay the inevitable. He had me dressed in an ornate, poofy silk dress with scenes of famous lovers painted in thread across my skirts, weeping on my knee and dancing a debutante ball around my ankles, clawing into the fabrics to climb up my calf, chasing one another up my thigh. I clamped my death grips around my drooping bouquet of weeping white hydrangeas as I walked a waltz down the aisle where he was waiting for me, dressed like he didn’t even care.

I faced him and felt my dress turn saccharine, sanguine, slowly, helplessly watching myself get swallowed by a horrific white cupcake. My vision clouded with frosting, my lungs filled with buttercream, my ears and eyes and nose stuffed full of dense, sweet cake. My mother had a dream like this—a white dress pulling me down into the water, swirling around me like foaming water; a necklace of pears breaking like a noose and falling like tears down my neck. She told me to go to the lake, and now I hold her flowers.

With my last breath, I yelled out to my father.

I begged him to cut me out of my wedding dress.

In another, he pushed me down a flight of stairs into his lake.

I hit the frozen surface hard and felt my bones shatter along with the ice beneath me. Paralyzed and rigid, I could only move my eyes, flicking them quickly across his face, which stared at me dying in the water. I reached out. He turned away. I let my eyes roll back into my skull.

I woke up in his arms, and he told me he’d saved me from drowning. He brought me to the things I loved and made me watch as I couldn’t do them. He held my hands up to my face to show me all the things I could no longer hold or have. He reminded me my body was no longer my own.

I couldn’t speak or move. Every inch of me belonged to him.

The last one started as a memory.

We were on my couch. My parents were gone. He chose the movie. We were holding hands. Mine got so sweaty; the accumulated sweat melted and started flooding the room like a great big broken pipe. The water tickled my ankles but I was glued to the screen, entranced by the enticing allure of not having to look at him until I had to, until I woke up. Until he woke me, craning his head back and arching his spine until it cracked like a sick joke as he howled at the lurid moon, looming over me like a voyeur.

I pulled my feet from the water. He grabbed my jaw. He made me watch. I watched him grow, swelling until the couch capsized under his weight. I watched and watched as his eyes bugged out of his face, and his nose shrunk down. I watched as his neck split open into gills and his arms flattened down into translucent fins. I watched as his body inflamed and burst out of itself, a long tail spilling out of his stomach. He continued to grow until he took up the entire room. I kept watching as his giant, fishy lips kissed my whole face and swallowed my whole head.

I watched until I knew him. Until he held me and soothed me with a crooning song that echoed like a lullaby on a sticky night by the shore. He told me everything was going to be okay as he swallowed me into the darkness of his stomach; a darkness that looked like the inside of my room late at night. I watched the sunrise and the days pass, and I watched myself have more dreams at night.

I can’t stop dreaming about him.

I think I’m living in a giant fish stomach.

6 T UFTS OBSERVER SEPTEMBER 28, 2020 18 TUFTS OBSERVER APRIL 18, 2023

DER LINDEN

DESIGN BY ANASTASIA GLASS, ART BY ZED VAN

POETRY & PROSE

On Learning

By Josephine Yip

we had an American English teacher from Texas in Primary 3

before I had the words to describe what Woody from Toy Story was

when I did not know the Chinese word for jeans meant cowboy pants

she taught us that the capital of this Lone Star state was Austin

and talked about the other jumbo cities: Houston, Dallas, San Antonio

in Primary 4 when I scored full marks on the mock mathematics exam

my teacher scribbled stupendous! next to the number 100 in red

I stared in confusion thinking the word meant stupid, brainless

and unbelievable as it was— or at least most Americans would think— that we had end-of-year exams starting from the ripe age of Primary One but that is the prime time to cultivate “work ethic”

alas I know nothing about the Wild West nor long division

nor what Americans think when they talk or act in the way they do

we speak the same speech but it always feels like different dialects

DESIGN BY AVIV MARKUS, ART BY AUDREY NJO APRIL 18, 2023 TUFTS OBSERVER 19 POETRY & PROSE

SOMERVILLE MEDICAL DEBT

By Layla Kennington

By Layla Kennington

On January 12, Somerville City Council unanimously passed a resolution to spend a portion of the city’s American Rescue Plan Act funding to alleviate medical debt for Somerville residents. The effort began as a result of increased medical expenses related to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has only intensified the already existing medical debt crisis in the US.

The city of Somerville is partnering with RIP Medical Debt, a national nonprofit that was launched in July 2014. Founded by two former collection industry executives, the organization claims to have relieved over $8.5 billion in medical debt for over 5.5 million families. RIP Medical Debt buys bundles of medical debt from hospitals and health care providers, which

allows them to alleviate “millions of dollars [of debt] at a fraction of the original cost,” according to the organization. This means the allocated funds will address “100x its value in medical debt.”

To be eligible for debt cancellation with RIP, Somerville residents must have household incomes less than four times the federal poverty level or have medical debts that exceed 5 percent of their annual income. It is not necessary to apply for the program. RIP notifies beneficiaries via a letter that their debts have been acquired and canceled.

The Somerville resolution commits $200,000 of the $77 million allocated to the city from the ARPA budget to medical debt payoff. According to Willie Bur-

ley Jr., a Somerville committee member instrumental in the resolution’s passing, this would ideally alleviate as much as $4.3 million in medical debt for Somerville residents.

Somerville’s commitment to debt alleviation is indicative of the city’s historical commitment to progressive policy. Mark Lannigan, a Tufts senior and Massachusetts Democratic State Committee member, highlighted the Somerville government’s track record of leading on national issues. “Somerville has always been a city that has stepped up to the forefront of progressive issues,” Lannigan said. “They’ve always kind of been on the cutting edge of taking on big fights before they were even taken on as national

NEWS 20 T UFTS OBSERVE R APRIL 18, 2023

the federal level. Most recently, the Biden administration announced a series of actions to lessen the burden of medical debt in April 2022. Proposed solutions to relieving this burden include eliminating medical debt as a factor in credit scores, completely forgiving medical debt for veterans, and having the Consumer Fi nancial Protection Bureau increase their education tools aimed at navigating the medical billing landscape.

Tufts Professor Amy Lischko, who currently serves as the Massachusetts di rector of health care policy, highlighted the importance of educational resources for American consumers when address ing medical debt. “Some of [the solutions] are at the policy level, and some are maybe educating people about the type of health insurance that’s best for them, and then how to use the health insurance that they do have.”

Medical debt impacts 23 million people throughout the US, a number that equals approximately one in 10 adults. In 2022, the Census Bureau released the Survey of Income and Program Participation. According to the report, people in the US owe a combined $195 billion in medical debt, making medical expenses the largest source of debt in the country. Across the board, racial minorities and those without medical insurance are more like-

In the face of the current dearth of federal policies aimed at the eradication of medical debt, the directing of ARPA funds towards the issue stands as a significant so-

posed to eradicating the reasons individuals acquire debt in the first place.

“I don’t think [RIP] is a solution to this problem long term. I think [RIP] is an important resolution for those individuals that are impacted today,” Sesso said in an interview with the A Second Opinion Podcast. “[But] I don’t want to lose sight of the fact that everyone [RIP] helps today, it’s improving their lives… [RIP’s work] is an important support and I can provide it for a low cost and relatively easily.”

Lischko echoed a similar sentiment. “You can always criticize those kinds of policies that aren’t getting at the root cause. But it’s a difficult problem as it involves policies that are more difficult to get passed. I think that [alleviating medical debt] is an innovative way of using ARPA funds… You’re not really addressing the root problem, but it does still bring relief to the families that do have medical debt,” she said.

The resolution is currently awaiting approval from the office of Somerville Mayor Katjana Ballantyne. If passed, Somerville would be one of the first in a line of municipalities working to relieve medical debt across the country.

Tufts’ relationship with its host commu nity of Somerville. “Tufts as an institution should be giving back more to our communities, [and] a very tangible way that [Tufts] could be doing a lot more is paying more in taxes,” he said. “This can help make up for some of the money that is going to disappear when funds from these federal programs disappear. A lot of the people that I have been working with at the state and local level have recently been looking at how to use [ARPA funds] in ways where we don’t become reliant on it.”

These one-time solutions are additionally problematic as they fail to address the systemic roots of medical debt. Allison Sesso, RIP’s CEO, highlighted the faults of solely focusing on relieving debt as op-

Lannigan retains high hopes for the future of the proposed legislation. “[The resolution] has really gotten a lot of support,” he said. “There’s been a lot of conversation about medical debt in the state [and] in the nation… I have my fingers crossed.”

NEWS APRIL 18, 2023 TUFTS OBSERVER 21

In February, The Tufts Daily published a breaking news story titled “Protesters disrupt Israel-Palestine discussion event, Monaco condemns protest.” In the article, the Daily reported on the protest of an event hosted by Tufts Friends of Israel and Tufts J-Street U. The Daily quoted J-Street U, describing the event as a “dialogue” between “an Israeli and a Palestinian who have the shared experience of living in the occupied West Bank.” Nowhere in the article was it mentioned that the “Israeli citizen” is an illegal settler in the occupied West Bank. The Daily lacked the diligence to do any of their

own research on the Roots organization that the speakers were representing. In fact, they describe Roots as a “Palestinian-Israeli initiative” when minimal research on its website shows that much of its “Leadership on the Ground” is made up of israeli settlers. One of these “leaders” describes himself as “a passionate Zionist settler.”

The Daily has also not published any articles about the over 100 people injured and at least 10 people killed by israeli forces in deadly raids on Nablus, Palestine. The lack of context for why protesters feel the need to disrupt events that normalize israel’s continued killing of Palestinians is, simply put, bad journalism. Out of context, the demonstration seems like a disrespectful action directed at “peaceful” speakers, rather than protesters showing their opposition to the whitewashing of violent colonialism through the platforming of a settler. The article sidelined the everyday violence Palestinians face through humiliating searches at checkpoints, illegal raids on their homes, and military presence in their neighborhoods, and it

ON CAMPUS AND BEYOND COVERING PALESTINE COVERING PALESTINE ON CAMPUS AND BEYOND

By Tufts Students for Justice in Palestine

22 T UFTS OBSERVE R APRIL 18, 2023 OPINION

framed the people who oppose occupation as a problem.

The ignorant framing of this article is part of a larger trend in the mainstream media of downplaying israel’s violent land theft. Every year near Ramadan, israeli occupation forces storm al-Aqsa mosque, a sacred site for Palestinians. The raids of al-Aqsa are covered in US and European mainstream media as “clashes,” “tensions,” or “confrontations” rather than armed israeli state forces attacking Muslim Palestinians who are praying during their holy month. A CNN article published on April 15, 2022 is titled “Jerusalem on edge as violence flares at key holy site.” Just days ago, the storming of al-Aqsa by israeli occupation forces was reported in the BBC under the headline: “Jerusalem: clashes erupt at Holy site.” These sources report israeli military forces storming al-Aqsa with the goal of enacting violence on Palestinians without explicitly naming who was perpetrating the violence in the first place. The decontextualization of these routine attacks on Palestinians works to normalize this violence as a clash between two equal parties rather than an attack on colonized people by their colonial oppressors.

Another example of decontextualized journalism took place last May when Al Jazeera journalist Shireen Abu Akleh was shot and killed by an israeli sniper as part of a larger israeli military attack on Palestinians. The New York Times initially titled an article “Shireen Abu Akleh, Trailblazing Palestinian Journalist, Dies at 51,” erasing who killed Abu Akleh— the israeli occupation forces. The title was later changed to “Trailblazing Palestinian Journalist Killed in West Bank,” but both titles demonstrate a major issue of mainstream media using passive voice to obscure the

perpetrators of violence. The article went on to quote the israeli military’s Twitter account, which claimed that “Palestinian armed gunfire” might have been responsible for her death. However, many eyewitness reports clearly confirmed that it was shots fired by the israeli military that killed Abu Akleh, supported by multiple human rights organizations like B’tselem and Amnesty International. The Times mentioned claims by Al Jazeera and the Palestinian Health Ministry that Abu Akleh was murdered by the israeli military, but created a false equivalency between these claims and claims of israeli occupation forces. Representation of violence against Palestinians as if there are always two sides obscures the unequal violence of settler colonialism and equates resistance of colonized subjects with violence from a colonial power. Nearly two months later, The New York Times finally published a detailed investigation of Abu Akleh’s murder clarifying that claims by israeli occupation forces were not factually supported and there were no armed Palestinians near her when she was shot. This passive reporting and uncritical inclusion of israeli propaganda negates the agency of israeli military forces and settlers who are committing the real violence inflicted on Palestinians.

Journalists often claim the need for an arbitrary standard of “objectivity” in their reporting, but to equate an occupier and an occupied people only denies the unequal reality. Last year was the deadliest year for Palestinians since the al-Aqsa intifada in 2005, with over 230 Palestinians killed by israeli forces and settlers. The Palestinian Health Ministry has described the past few months as the deadliest start to a year since 2000, as over 90 Palestinians have already been killed since the start of 2023. The framing of “Israel/Palestine” as a conflict instead of a colonial occupation makes israel’s continued ethnic cleansing of Palestinians possible; it leads readers to believe neutrality is acceptable.

Furthermore, the Society of Professional Journalists, a US journalism organization, states ethical journalists should provide context and “take special care not to misrepresent or oversimplify in promoting,

previewing or summarizing a story.” The Tufts Daily and countless other news outlets have neglected this journalistic duty in their coverage of Palestine.

Journalists on every level, including at the university level, must take steps to stop the normalization of settler colonialism and take the side of the colonized. Last April, for instance, The Harvard Crimson’s editorial board put out a statement in support of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement, which calls for economic action against israel. The Tufts Daily released a strong statement condemning Russia’s war crimes against Ukraine just over a month ago, applauding Western attempts to sanction the occupying nation. The same situation applies to Palestine and the Palestine solidarity movement which calls for boycotts, divestments, and sanctions of israel and israeli institutions and companies until Palestine is free. We urge all news outlets at Tufts to adopt the same condemnation of the israeli occupation of Palestine and heed the call from Palestinian civil society by endorsing BDS. Additionally, we urge all student journalists to consider the language they use when writing about Palestine and Palestine activism on campus. The stakes are high. News media is one of the first ways people learn about the events around them. Therefore, journalists have a special responsibility in shaping the narrative surrounding acts of colonial violence. We do not live in an equal world. Therefore, journalists must consider their power and positionality in every aspect of creating a news story, from the language they use and the voices they platform to the ultimate narrative they produce. Readers and consumers of media must also be wary of any media they consume that claims to be “neutral” in the face of oppression, settler colonialism, and genocide.

We encourage anyone seeking out news on Palestine to follow these alternate sources for coverage of Palestine: Mondoweiss, the Institute for Middle East Understanding, Eye on Palestine, Electronic Intifada, +972 Magazine, Within Our Lifetime, and Al-Quds.

OPINION

TUFTS OBSERVER 23

DESIGN BY ANTHONY DAVIS-PAIT, ART BY NOUR EL-SOLH APRIL 18, 2023

SLEEP IS THE MONSTER ON MY BED

By Veronica Habashy

I was a poor sleeper from the start. Until I was seven years old, I slept in the same room as my parents and younger sister, not for lack of space, but because I wanted to. I recall waking often, excluded from the scene of a room that was snoring in harmonious tension with its own silence, disappointed in myself for failing to comply with such an ordinary task. I have no recollection of ever daring to wake anybody so they might keep me company, but I can vividly see the image of my mother sitting up in bed with me, snacking on a sliced Persian cucumber, after which I must have drifted back into sleep every time. At school, during naptime, I habitually shut my eyes in faux slumber, never actually falling into the warm net of the afternoon nap so kindly offered to me. Instead, I remained stiff, my body humming in discomfort with itself, and eavesdropped on the conversation of the adults in the room, always wishing someone might notice I was still awake but never considering telling them myself.

A state of perpetual sleepiness would be a challenge for most children. Every moment I spent awake each night turned into weighty remainders which pushed steadily down on my eyelids, my head ready to fall forward at any moment of the day. I was apt at dozing off on car rides (coming home, leaving home, etc.); in the dim afternoon heat of a class after lunch, sitting up and with my eyes open; or with my head down on the table in the stark, fluorescent attention of restaurants, lulled by the humming of voices and the clinking of silverware. I seemed incapable of getting all the way to REM unless I was in the company of other people who were wide awake.

My youngest years, dominated by the hazy cloud of constant fatigue, faded

into tense and vivid adolescence. Beginning at 13, my months were often blocked out by phases of inexorable insomnia followed by weeks of near-narcolepsy. My diagnosis of insomnia by Dr. Goldsich, my exceedingly optimistic pediatrician, was unexpectedly unceremonious. For some reason, in all my years of sore necks and cheeks pressed against the car window, I was waiting for something more. She, however, seemed unfazed, and was not quick to provide a solution other than discouraging me from caffeine. Unsurprisingly, my adolescence was characterized by a bitter, nascent anxiety which clutched at my stomach and tied it into an expert palomar knot, squeezing a tense headache into the narrow space between my eyebrow ridges and the skin that covers them. I resorted to occupying each unclaimed moment of my days with sleep in some naive and blind trust of its restorative, forgiving, and non-discriminating qualities. I felt perhaps that I had earned its sweetness after each day spent bouncing my knees into oblivion, raising my shoulders into a semi-permanent embrace with the sides of my neck in the unceasing concern for things that had not yet occurred. I failed to consider a source, that perhaps it was the prospect of falling asleep around other people which ate away at me, the recurring nightmare of dozing off so deeply that I missed the end of the day, an unintentional Irish goodbye—except it was everybody else leaving me instead. I came to see my bed as an island on which I had to strand myself each night in submission to the self-fulfilling prophecy of tossing and turning perpetuated by each preceding night. It is unremarkable that I felt lonely as a teenager. However, I did not come to recognize this until each night, when I rendered

myself paralyzed, resigned to another night of failure. I felt that I had no other choice, and I kept my own limbs splayed and pinned to the bed as a frog primed for dissection, always during the disappointing purgatory of the swallowing hours between late night and early morning, and then awake again half an hour later, and again without fail. It was then that I finally heard the rare silence of my house, interrupted only by my father’s snoring down the hall, and remembered the isolation of being the only one awake all those years I spent sharing that room full of heavy sleepers.

To learn solitude and its prerequisite loneliness is at the centerfold of growing up—at least it was for me. Coming to terms with the fact that sleep’s kindness has never been guaranteed is on the following page. We often construct this concept of getting worse at sleep with age, but then what of nights spent shrieking from the crib for the soothing warmth of company? And haven’t we always craved the weight of bedtime stories, back rubs, and tight sheets in order to understand that it was okay if we rested, closed our eyes, and didn’t worry for just a few moments? Perhaps the juvenile nightmare is just the young body’s sudden awareness of the cold, stuffy air around me, nearly suffocated with its empty pressure. I realize now how I have mistakenly, in resentful disdain, blamed sleep for being the one gift which I could never seem to receive from myself, supposedly promised to me by the end of each dizzy and relentlessly sunny day, no matter how willing I was to give it. Now I question who it was that told me that if I was just a little more patient, then my rigid horizontal posture would eventually melt into something sweet and childlike, belly up like a cat who trusts

VOICES 24 T UFTS OBSERVE R APRIL 18, 2023

the sun through the open window shade far too much.

We are brought up to shed our fears of the dark, to count our own sheep in solitary silence, and to trust that we are the only ones in the room despite its sprawling blackness and the unknown corners of the closet and beneath the bed. The truth is that the dark represents the crushing weight of isolation that we must, as children and then teenagers and then adults, confront and grapple with each day. Lying there alone in it is a concentration of a most acute loneliness that, despite how much one enjoys such a state, is always a gravitational pull in ward of the self all at once, forced to re member its true smallness. How, then, is anyone meant to sleep soundly all alone in the choking quiet of the room which I have, at long last, been asked to begin sleeping in by myself? Amidst all the anxiety, I wonder now—how much do I really deserve to feel the barren, sheepish shame that comes with wak ing from a moment timidly stolen from the harsh daylight? What do I have to do to get permission for my eyelids to quit their straining and let their immense weight plunge me into something solid and bolstered by the palpable presence of other people, awake and obliged to wake me if they were leaving? For a long time, I woke every morning to a creaky and stiff sternum, sore from the way my body would fold itself down the middle each night, creased in self-comfort.

As I grow up, I am finally willing to recognize my insomnia for what it is, and I find that I am steadily turning past it. There are certainly still nights when I wake from dreams of a stifling exhaus tion that pulls me away from the rest of the world. My most frequently recur ring nightmare is one of that syrupy conscious lethargy consuming my body, and the frightening awareness that de spite how much I want to explain myself and say that I’m sorry, and that I just need to sleep a little while longer, my mouth is sealed shut and I am left be hind by everyone who is awake enough to be a normal person. Usually waking

from this dream to the silence of only having been asleep for two hours is clutching and unsettling. However, in my first year of college, I often roll over to see my roommate in settled and graceful repose, learn

VOICES

APRIL 18, 2023 TUFTS OBSERVER 25

DESIGN BY JAZZY WU, ART BY ADINA GUO

BETWEEN TWO CULTURES

TRANSNATIONAL ADOPTEE VOICES AT TUFTS

By Josephine Yip and Iris Yang

Over the past few weeks, Tufts China Care has hosted several events for the transnational adoptee community, both on campus and in the wider Boston community. A waffle-making event for adopted children and their families in March was followed by an annual fundraising event last week, where students purchased tickets to play games. All proceeds were donated to the OneSky Foundation, an organization that aims to provide better lives for at-risk children and orphans in China, Mongolia, and Vietnam. In addition to raising money for the OneSky Foundation, Tufts China Care aims to connect local Chinese-born adoptees with their birth culture and raise awareness on campus about issues related to international adoption. The organization represents one of few spaces at Tufts where transnational adoptees can talk about their shared adoptee identity.

Transnational adoption, or intercountry adoption, refers to the process by which an individual or couple adopts a child who was born in a country different from the

one in which the adopter(s) reside(s). In the US, the largest population of transnational adoptees is from China. Following the implementation of the One-Child Policy in China in the 1980s, the number of local orphanages increased to meet the demands of families giving up their children for adoption due to financial concerns and the government’s increasing efforts to curb population growth.

The lives of transnational migrants, including students at Tufts, are often characterized as being in between two nations and two cultures. Anju Meyer, An-lin Sloan, and Megan Starses—three members of Tufts China Care—all have unique relationships with their identities as Chinese transnational adoptees. Meyer, Sloan, and Starses all are ethnically Chinese and were raised by American parents in predominantly white areas. Although China is the most popular country to adopt from, it represents a small portion of the larger transnational adoptee community.

Meyer is a sophomore at Tufts and a member of Dumplings, a subgroup of

26 T UFTS OBSERVE R APRIL 18, 2023 CAMPUS

China Care, which organizes events to help transnational adoptees in the Boston area connect with their culture through games and activities such as calligraphy writing and egg-waffle-making. As an adoptee herself, Meyer finds the opportunity to interact with adopted children and their families meaningful. She sees it as a chance “not [to] pay it forward, but to provide kids with a space to embrace their adoptee identity.”

Meyer was adopted from Lianjing, located in the Guangdong province, at 10 months of age by a white couple. Growing up, Meyer said her parents were open about her adoption and commemorated her “Gotcha Day” each year—a day that marks the anniversary of when an adopted child joined a family. “They told me—and my sister, who’s also adopted— very early on [about our adoption], which I guess was probably good for my mind. I feel like I’ve never really had an issue with it,” she said.

Many adoptees have no recollection of their life before adoption, and all three interviewees said their adoptee identity is a fundamental part of who they are. However, being raised in a western country like the US, it can be difficult for adoptees to find a connection to their birth culture. Even though Meyer’s parents, who initially intended to adopt a child from India, were open to different cultures and diversities, Meyer remarked that she wishes she was more connected to Chinese culture. “I could have gone to Chinese school, which I wish I had. There was a school in Chinatown which [offered] a dual-language program. We went to the Chinatown Parade during Chinese New Year… which is nice,” Meyer said. But she also recognized that “having white parents… it’s kinda hard.” She said, “I don’t think I missed out on anything per se. I’m not sad that we didn’t do anything. But [Chinese language and culture] were not the biggest part of my upbringing.”

Like Meyer, Sloan, who is a sophomore and the Education Chair of China Care, was adopted from China at a young age. She said being adopted is just a natural part of life. “[My parents] are the only parents I’ve ever known. They are my par-

ents; they’re not my adoptive parents,” she said.

However, Sloan highlighted another experience that is not specific to adoptees but closely linked to the general demographic of couples who choose to adopt: having older parents. “The majority of adoptive parents are older [than birth parents], at least in the US,” said Sloan, which leads to a larger age gap between parents and their children. Sloan’s parents considered having children, but were focused on their careers. As her mother got older and decided she didn’t want to go through childbirth, Sloan’s parents decided to adopt from China given her mother’s cultural heritage as a Chinese American. Sloan said growing up with parents from an older generation led to parent-child interactions that were “way different than [those of her] other friends who had much younger parents… the values are different. They’re in the old Baby Boomer mindset.”

While the age gap has led to funny moments, such as being mistaken as her mom’s granddaughter at Chinese restaurants, Sloan expressed more serious concerns about her parents’ health and their futures. “There are statistically less years you have with them, so it’s a little bit worrisome, but not something you think about every day… Just as you’re starting your career, you also start taking care of them. I definitely want them to be around to meet my kids.” Although many people will encounter the same worries as their loved ones grow older, Sloan sees this as a marker of her adoptee experience.