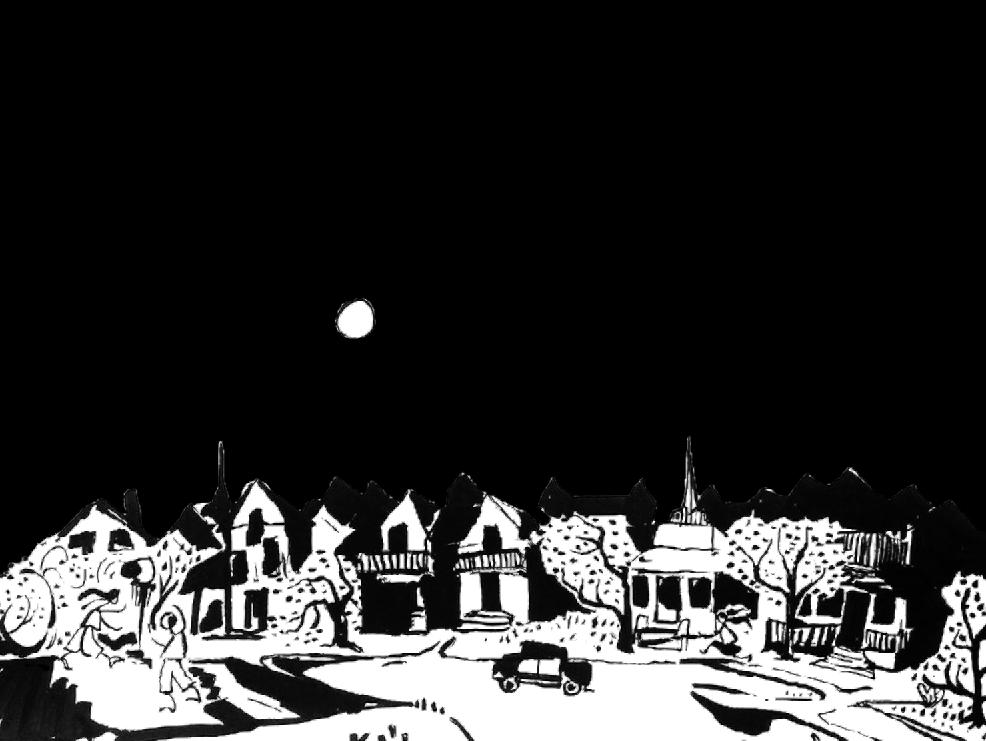

Language has always intimately intertwined with my emotions. I have written myself through life for a while now. Writing has carried me through my first heartbreak, the joys of moving to Somerville, and the memories I continue to make. The idea of the written has given me peace since I was young. (maktoob) is a phrase in Arabic that translates to, “It is written.” It was only in Arabic 21 did Souhad explain the grammar, the rules, and execution behind the phrase that rolls off the Muslim community’s tongue. is a passive phrase in Arabic; you construct it by slicing up a verb, adding in a couple letters, and squeezing it into a sentence. In its essence it is the doing of writing. In life it means whatever is thrown at you was meant for you. In joy, communities glee in pride, and in sorrow wraps you like a mother’s hug or the warm blanket we all need.

This phrase reminds me of the power of writing. If our futures are pre-documented, whose written do I get to explore next, who am I written next to, and what is written next for me. The Observer has written a lot this semester—from the stories of faculty of color to women’s rights in Iran. These are all stories that were written in a conversation of frustration, in a hope for equality, or in a demand for this institution to be better. I’m enamored by all the stories we’ve collectively compiled in 150 pages over the past three months.

Tonight is my last layout at the Observer. I joined this magazine my freshman fall, perched over my tiny desk in Hill Hall opening a horrible software called Remo. Ironically enough, my first article was edited by Melanie, who is now sitting across from me eating a BJ’s chocolate cake, Dumpling Kitchen lo mein, and debating whether a “a twit for a twat” is an appropriate article title. Every semester at Tufts, the Observer has been my sense of stability. I sludged into the MAB Lab to rant about life to Aroha and Mira, who would blindly support me. I successfully convinced Juanita to drop her CBS major as she guessed everyone’s big threes in a creepily accurate manner. As a staff, my favorite moments were when we matched dating apps to their corresponding Tufts Dining establishment, begged the copy eds to eat the cake, and categorized each other as gaslight, gatekeep, or girlboss. I’m thankful for all the laughs, bad puns, category games, and quote walls I’ve enjoyed for the past couple of years. I truly cannot imagine learning and loving without them. Thank you Melanie for helping me get everyone out early (except tonight), participating in lengthy email chains, and being there since the beginning. Thank you Julia and Ines for your infectious smiles and boundless creativity. Thank you Marco and Emilia for slyly stealing snacks and always making me giggle. Thank you Aidan and Uma for organizing and creating beautiful artwork. Thank you Emara, Hanna, Ruby, Claudia, Layla, Eden, Amanda, Priyanka, Juanita, William, Sophie, and Michelle for letting me annoy you and always pushing me and the Observer to be better. And thank you to all the people to the left of this letter! It has been the utmost pleasure to be written next to all of you <3

DESIGN BY JULIA STEINERS, PHOTOS BY SABAH LOKHANDWALA With power, Sabah LokhandwalaI’ll be in an airport next week. Tucked into my suitcase: long woolen socks, a few novels from class that I can’t part with, and a handknit sweater (not knit by me). My bag is swollen with the better parts of my life, as well as the mundane toothbrush and some less exciting socks. If someone opened it they might see right through me; they might not. Maybe they’d see that I’m trying really hard. Layover in Chicago Midway. I’ll have a hot dog (poppy seed bun, sport peppers, pickles, mustard). Like nowhere else, the airport is a place of simultaneous vulnerability and anonymity. I know why I’m going where I’m going. But why are they? The plane taking me home is delivering someone else far from theirs.

People don’t understand why I like to go out just to sit on nearby benches. When they ask about it, I tell them I’m never just sitting. I watch the world—people, animals, and all—pass by, coming up with stories to accompany these new charac-

As a university, Tufts has abandoned its formal mission and core values. We as students have witnessed the university claim to uphold principles of anti-racism, freedom of expression, and equity, yet not practice them when given the opportunity. This has caused concern within the student importance it held in creating a richer campus culture and the skills she learned. “We were there during the [anti-Apartheid] sit-in at Ballou Hall, [and for other] student protests that we were covering as the Observer,” she said. As far as the relationship between student journalists and the Tufts administration, Moore said,“It was the same in our times… [There] was a bit of a contentious relationship with

the administration.”

Tufts’ Media Relations has halted providing comment to the Observer and has asked administrators to do the same over concerns with the accuracy and fairness of the Observer’s reporting on the administration. The Obis currently engaged in ongoing conversations with Tufts’ Media Relations regarding fairness of reporting. e are concerned by Media Relations prohibiting administrative staff from Observer student journalists based on our editorial decisions. This is especially alarming considering Tufts officially recognizes “freedom of expression and inquiry are fundamental to the academic enterprise.” In the past, student journalists had direct contact with administrators, and Media Relations intervention was not required. The current process limits students’ direct access to administrators, creating an unnecessary barrier between those in power and the student body. As student journalists in an institution that promises freedom of expression, we deserve access and transparency from Tufts administrators.

The Observer remains frustrated with the university’s relationship with student journalism and activism due to a history of tension between administrators and students who desire change at Tufts.

In recent years, Tufts has neglected to listen to the student body’s concerns and support initiatives with large student support. For instance, this semester, Tufts declined to voluntarily recognize United Labor of Tufts Resident Assistants

(ULTRA) which has received official endorsements from Somerville City Council and Medford City Council, in addition to formal support from the TCU Senate and widespread support from Tufts community members. In fall 2020, Tufts Students for Justice in Palestine and Tufts for a Racially Equitable Endowment passed two referenda questions through the Tufts Community Union special election with a majority of student support. The questions concerned the demilitarization of the Tufts University Police Department and a proposal for Tufts to divest from “corporations that profit off of the private prison system” respectively. Tufts ultimately refused to recognize the results of both referendums. Additionally, the Office of Equal Opportunity (OEO) declined to recognize caste as a category of discrimination despite widespread student-supported efforts to do so. Altogether, these instances point towards a university whose true values are more at odds with its students’ values than it is willing to admit.

Tufts owes its students transparency in relation to issues faced by the institution, especially since Tufts’ mission statement directly posits “effective stewardship” as a priority for the university. Tufts also claims to center diversity and inclusion in its mission, saying that the school strives to create an environment of equal opportunity where all students, faculty, and staff may “thrive here and have opportunities to participate fully.” In the interest of its fellow Tufts community members, the Observer calls on Tufts to faithfully adhere to these promises.

Tufts students, faculty, and staff have been alerted to allegations of a “toxic” work environment that has come to taint the experiences numerous of Tufts’ ad ministrative staff of color. Importantly, the allegations—as reported by the Daily—refer most seriously to the actions of senior members of faculty and staff and suggest that individuals such as Dean of Admissions JT Duck and provost ad in terim Caroline Genco bear responsibility for propagating exclusionary values within the workplace. A university authentically concerned with ensuring diversity and in clusion would take these issues more seri ously and address them with urgency. Ad ditionally, the Office of the Provost houses the Office of DEIJ, indicating that Tufts is fundamentally paralyzed from carrying out DEIJ initiatives. This is particularly egregious and concerning when considering the university’s consistent rhetoric of anti-racism since the murder of George Floyd in 2020.

The ongoing “mass exodus” of faculty and staff of color suggests the university has failed in its written commitment to

make Tufts a place where “all members of our community feel a sense of belonging and are empowered to contribute in ways that celebrate the most important parts of their identity.” Students suffer significantly as a result of the continued loss of BIPOC faculty and staff from the university. students are frustrated by the university’s lack of transparency. In a statement posted to their Instagram account @ tuftspaa, Tufts’ Pan-Afrikan Alliance wrote, “What is shocking is the continued proclamation of Tufts University

On November 17, the editorial board of the Daily published an editorial condemning the institution for its failure to uphold anti-racist values as well as its continued lack of transparency.

The Observer echoes the Daily’s concern and urgently calls on the university administration and newly announced President Sunil Kumar to prioritize transparency and communication between the administration and the student body.

As Tufts elects its first person of color as president, the Observer editorial staff insists that new leadership goes beyond descriptive representation and truly put the values, needs, and ideals of its students first over optics. Per the Declaration on Freedom of Expression at Tufts University, “When community values are not respected, every member of the Tufts community has an obligation to respond.” It is the editorial staff that Tufts has not been respecting community values, and it is in this spirit that we demand more of the university. voice these concerns because we know the university—the place we call home

Moore said, “There’s always going to be someone that would like you to cover them in a favorable light. And the true mission of journalism is not necessarily to [do that]. PR is a different field than journalism for a reason.”

By the Pan-Afrikan Alliance

By the Pan-Afrikan Alliance

It was the first community dialogue hosted by the Pan-Afrikan Alliance this year, a group dedicated to furthering the political well-being of the black diaspora. The question came from a discussion leader as he stood in front of a group of students spread around the lounge of the Africana Center. Really, the question was not meant to create debate, and the collective groan around the room that elicited a cheeky grin from the leader made that apparent. One by one, a steady flow of grievances spilled from the students’ mouths. It was a veritable torrent of the various ways black students felt wronged by this institution, and each sentence was accompanied by their peers’ hoots and finger snaps of approval. Each issue built upon the next, and you could see each student becoming more impassioned, more deliberate in every word.

If you haven’t already caught on, the answer to that question was a very hard “no.” For those of us in tune with the black political conscience at Tufts, this isn’t exactly surprising news. Black students are angry. And they want to be heard.

The mountain of grievances black students have had with Tufts has a long and extensive history, but the Pan-Afrikan Alliance has selected from among them some core issues that resonate with the black student body. These include the insensitive behavior of JT Duck, Dean of Admissions, the lack of transparency in Office of Equal Opportunity reports on racist attacks and hate crimes, the departure of Diversity leaders Rob Mack and Joyce Sackey under the reign of Provost Caroline Genco, and, most importantly, the utter failure that is Tufts’ retention of black faculty and staff. These issues have been condensed into a public statement, and we will be proceeding with a TCU resolution to emphasize our commitment to the effort.

It seems every other month students’ inboxes are graced with an email directly from the Tufts OEO. The contents will give a bare-bones snippet of a reported racially motivated or antisemitic attack, followed by a stock response that tells us not to worry— Tufts is on the case. Shockingly, this has not at all resolved the black student body’s concerns over how hate crimes are handled. Attacks are treated with utmost secrecy, as the primary goal of the investigation is to protect Tufts. After the initial email, students are provided no communication on how the incident is treated, and students whose identity group is harmed are never consulted on how Tufts can make the university a safer and more welcoming space for them.

How did this attack happen? What was the severity of the situation? These are among the questions that are never answered. In the PAA meeting, students mentioned their lack of confidence in the OEO’s ability to resolve these issues. The popular sentiment is that our concerns are swept under the rug, and that we should look for alternatives to counteract this dismissal. The fact that black students, some not even old enough to call themselves adults, are pitching ideas to protect themselves speaks to the abject failure that is the OEO’s relationship with the black student body.

Tufts’ OEO is far from the only issue students have with the Tufts administration. The interim Provost and Vice President of Tufts have been mentioned many times during PAA meetings. Caroline Genco’s term has overseen a large departure in staff in the Office of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Justice at Tufts. The Tufts Daily reported on her contentious tenure, marked by workplace hostility and racial ignorance. Within a couple months of her term, Tufts had lost two of its chief diversity officers. Students

o you think Tufts is an anti-racist institution?”

were not notified of their departures. Furthermore, Genco does not seem to value the input of black leaders on Tufts’ race relations. The Juneteenth Planning Committee at Tufts, a group consisting of African American leaders, submitted a resolution on May 3 questioning the intent of Tufts’ observation of the holiday. The Juneteenth committee was concerned the university had not considered the opinions of the black student body on whether they wished for the institution to go through with the half-day of programming. The resolution also outlined that the short length of the programming was contradictory to its sentiment of commemorating the holiday.

The Juneteenth Planning Committee extended an offer to meet with the Provost in hopes of creating a productive dialogue surrounding the programming. The Provost showed up to the meeting with the head of Human Relations at Tufts in tow in a show that, according to S. Rae Peoples, an associate director of diversity and inclusion education and member of the Juneteenth committee, was reasonably interpreted as “intimidation” and a “posturing of power of the committee.” Committee members reported being deeply offended by the way the dialogue unfolded during the meeting. They depicted the events of the meeting to be “disheartening, scolding, thrashing, and frightening.” For the meeting between black leaders and one of the members of Tufts’ upper echelon to be characterized with such abrasive language speaks to the fraught relationship this “anti-racist” institution has with the black community.

The rampant culture of racial insensitivity runs deep, and it’s no shock to black students that this trend continues when the topic turns to the Dean of Admissions, JT Duck. According to a Tufts Daily article, Duck has been responsible for creating a climate current and former employees describe as “racist, sexist, transphobic, and antisemitic.” From the start of his tenure at Tufts in June 2019, Duck has overseen the departure of at least 22 employees from the offices of admissions. Nine of the current and former workers described the work culture as “toxic.” There have been multiple complaints submitted to the OEO concerning reports of Duck “[ignoring] discrimination allegations and [punishing] people who criticized him.” The Dean of Admissions’ tenure has clearly been characterized by an approach that runs contrary to any form of anti-racism. The PAA believes his continued behavior and the blatant lack of accountability are unacceptable; what does it say about Tufts to be reflective of a system upheld by a misuse of power?

It is clear Tufts’ upper management has a history of insulating the superiors from allegations of discrimination and toxicity against minority rank-and-file staff, but nowhere does this phenomenon become more apparent than the retention rate of black staff. With black faculty increasingly suffocated by a work culture that views them as expendable, there has been an alarming rate of departures from minority staff specifically, as reported by the Tufts Observer. Reasons for departure range from there being “no accountability procedures for managers to follow,” to working at Tufts being described as so suffocating that leaving was “to gain some respite from experienc[ing] unrelenting discrimination.” To think that the work atmosphere at Tufts would ever be described as actively hostile to minorities is an embar-

rassing blot on the record of this institution. Black students want to see themselves in Tufts’ management and staff. In a setting that actively chases out the people that resonate with our beings, there is a feeling of utter dejection.

Complacency with Tufts’ harmful actions, ones that are veritably adversarial with the well-being of black students and faculty, has been going on for long enough. The PAA is in the process of drafting a Tufts Community Union resolution to highlight these moral failures. These include addressing and creating a detailed, transparent plan to identify the lack of faculty and staff retention and remedy it, discussing the nature of the OEO’s reports, and having an even-handed and mutual dialogue between the Tufts administration and black campus organizations. We’ve already created a public statement addressing some major concerns, and the majority of black student groups at Tufts have signed on in support. The collective effort in trying to shake the foundation of a centuries-old institution is monumentally difficult, but as black students have shown time and time again, we’ll be there on the frontlines. Because unfortunately, as always, we have to be.

With regard to the future, Tufts is in the process of a transfer of power at the presidential level. Incoming President Sunil Kumar will be overseeing a tumultuous institution that, to black students, is steeped in racial scandal. We wish him the best in his term and hope for him to be the shake-up that Tufts sincerely needs. We hope his status as the first president of color will inform his choices and make Tufts a more hospitable place for diversity in body and thought.

On the flip side, we will be watching closely, as always, for however long Tufts gives us a reason to.

By Anthony Davis-Pait

By Anthony Davis-Pait

Editor’s Note: Anthony Davis-Pait is currently a member of Access Betters the Lives of Everyone (ABLE).

mong much of the student body, it is understood that Tufts is a very inaccessible campus. However, the actual barriers disabled and neurodivergent students face are not as widely known and go beyond the fact that the campus sits on a hill.

Julian Hammond, a senior in the Resumed Education for Adult Learning program and founding member of Disability Queers, a new student-run affinity group with the LGBT Center, defined ableism as “systems that privilege able-bodied people, either directly or by virtue of harming and restricting access to non-able-bodied people… and anyone who has a different neurotype or learning style or dietary need, or literally anything.”

Sophomore Morgane Hanley emphasized how ableism is a systemic issue at Tufts. For example, they have had to advocate for broken accessible door buttons to be fixed rather than someone being in charge of making sure the infrastructure works properly. Hanley said, “Ultimately [all of these things combined take] a physical, social, and mental toll on my wellbeing and [ensure] that I do not have an equal opportunity to succeed as a student on campus.”

Theatre, Dance, and Performance Studies, cited the Aidekman-Jackson complex as an inaccessible space on campus. He said, “Until the university puts in the money and resources necessary to transform the space, the building itself is going to be a fundamentally ableist structure.”

ableism at Tufts is the lack of learner variability and the rigid grading styles in classes. “All people learn in different ways and demonstrate what they have learned in different ways—regardless of whether they are diagnosed as neurodivergent or not,” Hammond said. Senior Jessica Goober, a co-leader of Access Betters the Lives of Everyone (ABLE), spoke highly of one of their professors who had lenient attendance policies, granted extensions, and employed a system in which students graded themselves. According to Goober, an inclusive class design

would also include recording every lecture and posting all slides.

Montez job as a faculty member and chair of the [department] is to serve every student of the university and to make sure that they’re given a space to learn, to experiment, to thrive… So if there who have accessibility needs that are connected to disabilities that they have, that’s part of the work that I have to do as someone committed to student learning, to make sure that I’m fostering that environment.” Montez said he tries to meet with students individually to get a sense of what their needs are and whether they have diagnosed disabilities or not.

Senior Al Bolton, who is teaching the Experimental College course “Disability Theories” next semester, said the primary reason they wanted to teach this course is that there isn’t one like it at Tufts. “I think it’s absolutely ridiculous that there’s not more dedication to [disabilities studies classes],” Bolton said. They hope that this course will become a

decision to remove the mask and testing mandates this semester. “There are a lot of people who are immunocompromised, so when you take away precautions, those people… [are] more likely to catch COVID from the same exposure of other people [and] more likely to have [severe symptoms] from it,” they said. “I don’t necessarily have the same kind of ability to be less cautious about [COVID] because I am personally worried about the potential higher complications if I do have COVID.”

Ary Wolfe-Herman, a co-leader of ABLE who is also immunocompromised, pointed out that the problem isn’t just with the administration’s policies. They said students who aren’t disabled or immunocompromised haven’t been taking COVID seriously enough. Wolfe-Herman said, “You could just put a piece of fabric on your face and that would just be so easy.”

The StAAR Center—formerly the Student Accessibility Services Center until its merger with the Academic Resource Center in 2020—is supposed to be a place to provide disabled students with support in finding accommodations; however, many students feel it is just another source of ableism on campus. Wolfe-Herman hasn’t engaged with the StAAR Center and says many disabled people choose not to engage with the StAAR Center for a variety of reasons. According to their website, the StAAR Center requires students to submit a registration form and clinical documentation of their disabilities in order to receive consideration for accommodations. Students who have not been formally diagnosed with a disability are, therefore, not eligible for accommodations. Further, Goober said, “The definition of reasonable accommodations is subjective, so there are no checks and balances” to ensure that students receive the accommodations they need.

Goober said during her sophomore year she requested an

accommodation from the StAAR Center to take a part-time semester and still be considered a full-time student, which would have helped her succeed during online learning, but she was denied this accommodation even after submitting a note from her therapist and doctor. WolfeHerman said even for students who have a formal diagnosis, the StAAR Center does not provide a list of accommodations students can request. Disability Queers has created such a list to fill this gap. Overall, some students feel the StAAR Center makes it unnecessarily difficult to receive accommodations. Hanley said they experienced “immediate pushback or prolonged pushback” against accommodations they needed.

ABLE is in the process of collecting student testimonies about their experiences as disabled and neurodiverse students at Tufts. They plan to use them to inform their work on campus and advocate for a Disability Center on campus. They hope a Disability Center will be a fully accessible space and a step towards making the campus more survivable for disabled and neurodivergent students.

The Disability Justice Movement, which formed out of conversations between disabled queer women of color activists in 2005, seeks to challenge systemic ideologies that are at the core of

on shifting our understanding of access from individualized to collective and interdependent.

Hammond said, “I feel like Disability Justice is a lot about eliminating the need for accommodations.” Hanley shared a similar sentiment: “How do we make it so that access needs are already built into spaces and systems? How do we ensure that access is treated as an inherent right rather than privilege so that disabled people don’t have the unjust burden of constantly fighting for the resources they need to exist and be successful in spaces?” Bolton believes access does not solve ableism in and of itself. They

encouraged people to focus not only on access but also on dismantling ableist ideas and norms at their core. They cautioned that increasing access is not liberatory if “all of the societal ideals and norms are still built in a way that [excludes] disabled people and [frames] them as abnormal— as something that needs to either be cured, disappear, or not be integrated.” access is a part of a broader vision of liberation from ableism. WolfeHerman sees this future as one that “allows us to simply live and exist and not have to constantly prove our worth and who we are and what is deserving... of time, attention, money, whatever it may be.”

“HOW DO WE ENSURE THAT ACCESS IS TREATED AS AN INHERENT RIGHT RATHER THAN PRIVILEGE SO THAT DISABLED PEOPLE DON’T HAVE THE UNJUST BURDEN OF CONSTANTLY FIGHTING FOR THE RESOURCES THEY NEED TO EXIST AND BE SUCCESSFUL IN SPACES?”

Once, when I was a child, my grandmother told me the story of La Llorona, of how her far cry was a warning to the children of the town to stay inside. Trembling under blankets, every child remained in their home, afraid to hear the distant voice approach their window. At that young age, the only image that remained with me was that of a weeping woman roaming the streets at night, black hair covering her drowned face. This story, among others, was a behavior management tactic my family used to call an end to my brother’s and my temper tantrums. And, for the most part, they worked. I recall my grandmother sermonizing about the children of today being absent-minded, locos, mal comportados, puny, and any other word that drove this message home. Yet, she managed to deal with all five grandchildren who came before me. And there began my understanding of the woman who sat next to me: a señora who was wise and contained a world’s worth of knowledge in her mind, una abuela, a grandmother.

At six years old, I had a pristine image of who Leticia Cortez was. When I turned seven, geopolitical borders marked an end to the physicality of family; the longing for the safety my grandma’s presence gave me found a home at the southern US-Mexico border. At 13, I was reunited with family from Mexico that crossed the border, among them the woman whose hands could cure all evil in the world. She was an abuela ready to take back her seat among

the table of angels who whirled around my upbringing. It was not until later that I came to know my grandmother as anything other than a caretaker.

In 2020, the future’s uncertainty became increasingly concerning as the start of my first college semester drew near. According to my parents, it was in my best interest to take virtual classes from home. I, however, wanted to leave. And I did. Despite the disapproval of my parents and my grandmother, my desire for independence and exploration carried me across the country from Texas to Massachusetts. Here, I found the distance to be simultaneously 1) culpable for the lonesome despair that accompanied me my first year, and 2) helpful in many ways. For one, it made me miss my family, a sentiment that hadn’t visited me often before. At the same time, it granted a space that allowed for growth. Distance bestowed a new perspective that made me want to connect with my family more than ever.

Gradually, over the span of that first year, each family member back home began to undergo metamorphosis in my mind. My father was more than just my father. At 18 years old, he had left his hometown in Mexico and traveled to Texas to work in field picking, and afterward flew across the country from state to state, summer or winter, to work. My mother held jobs as a secretary and a house cleaner as early as 15 years old. This information, which had been presented to me before,

was now being perceived through new eyes, eyes which had now seen a little bit more of this world. As a result, only now was the effect of those stories life-changing. During this time, I began to think of my family as people who had endured hardships way before I existed. Doing so made me understand that even though our situations were different, the very essence of how we felt was similar. Above all my newfound connections, the most important was my grandmother, whom I missed the most. She and I both stemmed from the same root.

Leticia Cortez was once a young lady reeling through the streets of Saltillo, Coahuila. She was once lost, messy, and in pain. Her hair, styled in accordance with the decade, swayed with the wind, bringing forth a new day’s adventure. Her mind, fraught with fears of the future– a future that is now my present,– played her favorite song on repeat: la sonrisa ancha / la lluvia en el pelo / no importaba nada / ibas a encontrarte con el. She sat at her desk, attentive to the teacher’s instructions. In 1974, at 20 years old, she was a student of the Autonomous University of Nuevo León, where she earned a degree in nursing. This, however, did not come easy.

By the time she got to college she already had four children of her own, my mother included. Call it tradition or circumstance, but these four children were her everything, fueling her with ardor to continue with her education. Every

weekend, while her parents helped with the children, she attended class. Despite how arduous it was at times, she always knew it was worth it. The tests, essays, group studies, and end-of-semester exams, things with which I’m all too familiar now, were once her present. She doubted herself before finals; she cried, sweated, witched her school hallways, mourned the loss of opportunities, celebrated gained experience, and came home to the family she’d created. Somewhere along that path, she gained the knowledge that made her the woman I’ve always known her to be.

The word before holds so much power in our lexicon. It both constructs and limits. The perspective of oral stories is one of the past; everything that is orated has happened before, the goal being to prevent it from occurring in the after. When my grandmother told me the story of La Llorona, it was told in the past tense because the world then belonged to the woman who became the cautionary tale. The word before only extends 21 years for me. Before that, there is nothing. Of course, there was a world then, but the world from then does not belong to me. It’s all my grandmother’s. And before her, there’s another mother whose life extends years before having her only child, and so on, until we reach the very beginning of life.

Before she was my grandmother, before she was my mother’s mother, she was just a daughter of two campesinos, a dream

girl for boys whose ambition did not even reach above her knee.

Even now, far away as I am from the woman who brightens every Christmas, I feel the presence of her 20-year-old self leading me through sidewalks of new beginnings and roads back home.

When Elon Musk acquired Twitter in October, the acquisition became fuel for memes and online mockery—yet beneath the jokes, there are serious implications. In a social media-obsessed society, the billionaire’s takeover of Twitter is an example of money buying power and influence. Musk’s changes to the platform, as well as the resulting fallout, raise important questions regarding the role of social media and the distinction between free speech and hate speech.

Musk’s time as Twitter CEO so far has been marked by seemingly impulsive decisions that have led some to claim he is making it up as he goes. Just a few of these decisions include laying off approximately half of Twitter’s employees, introducing a now-paused paid verification system with Twitter Blue, and promising to reinstate previously banned accounts—including Donald Trump’s account and those that have previously violated Twitter’s rules on hate speech. These changes open the door for altright accounts to have more reach and influence.

Jennifer Best (A’22) spoke about her own experience with Twitter. “I’ve seen more friends and accounts I’ve followed getting attacked with right-wing campaigns to try to report them or just hate comments. More people that I know have been getting that and very specifically once Elon Musk took over,” she said.

In the wake of changes and Twitter’s currently precarious position, over 1000 additional employees have resigned. Musk is also scaring off advertisers, with 50 of the platform’s top 100 advertisers having slowed or halted their Twitter advertisements. Media Matters for America cited Musk’s “rash of brand unsafe actions” as the reason for these decisions.

Many of Musk’s actions as CEO boil down to his goal of increasing free speech on Twitter and his contested claim that Twitter is “the de-facto town square.”

However, the legal right to free speech refers to government regulation, not a company like Twitter. “His version of free speech seems more like letting hate speech exist,” Best argued. “[Twitter] is a private company that does have the right to regulate speech.”

Best currently works as the Communications and Outreach Manager at the Massachusetts AAPI Commission, and, while she has not seen a rise in hate on the account she professionally runs due to the organization’s small size, she still voiced concern over what may be to come.

Sophomore Maya Chandrakasan, an avid Twitter user, shared similar sentiments on Musk’s free speech claims. “It’s free speech for people who he agrees with and whose voices he wants to platform,” they said.

In a written statement to the Tufts Observer, philosophy professor Benedetta Giovanola said, “[W]e should go beyond an exclusive focus on the speakers’ right to freedom and acknowledge also the importance of the hearers’ rights, such as the right not to be harmed and the right to be respected as a person.”

Hate speech has in fact increased since Musk’s takeover of Twitter. Part of this may be attributed to the fact that content moderators were among those laid off. Large amounts of hate speech online can contribute to the normalization of this language and hateful actions offline.

Giovanola wrote, “Besides showing a strong correlation, if not a causal link with hateful actions offline, hate speech online promotes the spread of a background culture of hatred, exclusion, and disrespect that is detrimental for the society as a whole.”

She continued that this may “erode our capability to engage in dialogue with others.”

At the same time, there have been claims of accounts being suspended for making fun of or challenging Musk himself. There appears to be a double standard with what content is considered hateful on Twitter. Chandrakasan said, “It’s just super hypocritical of Elon Musk to say, ‘Oh, I’m just going to reinstate all of these banned accounts,’ while he’s continually in the process of banning other accounts that are critical of him.”

In the same vein, a lack of proper content moderation will also result in increased misinformation. During the short time it was in place, Twitter Blue allowed for the impersonation of previously verified accounts. Some used this function to seemingly mock large, controversial corporations—such as a fake Eli Lilly and Co. account tweeting, “We are excited to announce insulin is free now.” However, this raises the concern of any account being able to impersonate anyone should paid verification be reinstated, including public figures or news sources.

The power Musk holds over Twitter is concerning when viewed in relation to Twitter as an information source. The platform is a valuable tool for many journalists, both in conveying news and receiving tips. Along the same lines, activists and organizers often use Twitter to connect with one another, share underreported stories, and publicly communicate information on protests and other similar events. Chandrakasan cited Twitter as an important way she receives first-hand news from other parts of the world.

According to Pew Research Center, for approximately 69 percent of US journalists, Twitter is a favored social media platform for job-related purposes. This percentage jumps to 83 percent among younger journalists between the ages of 18–29.

“Social media [has] become the main source of information for most people. Yet, social media companies are not considered (and do not want to be considered) as media, but rather as networks that connect people and ideas,” Giovanola wrote. “This (mis)conception has serious implications not only for the issue of content moderation (which is left, at best, to the decision of automated algorithmic systems or single individuals) but more deeply for the understanding of social media’s role in shaping the public sphere and for the regulations they need to be subjected too.”

Best said, “People underestimate social media and how complicated and

important it is. How people get a lot of news, and also within activism, a lot of information is shared through Twitter. And so if we were to lose it, we’re not just losing a way to stay in touch with friends, but important information networks.”

These crucial uses of Twitter for information now essentially lie in the hands of a singular billionaire. Chandrakasan said, “It’s just dangerous for a single person to have control over such a big platform. Twitter is so widely used by so many people around the world, and it’s just such a big place for people to challenge power and create community.”

When one has as much money as Musk, power is inevitable. It is this disproportionate amount of wealth that allowed him to buy Twitter in the first place.

Regarding Musk’s current power over Twitter as just one person, Giovanola said, “All [of] this can amplify a problem that already affects social media, that is, the problem of a concentration of power in the hands of a few private individuals that set the rule[s] of the game.”

This concentration of power with the wealthy is a concern shared among many. Best said, “Hopefully people will start to realize how much capitalism is really controlling and suppressing and limiting options and giving uber-rich people the power to do what they want.”

The future of the platform rests in Musk’s hands, and if the past couple of months have been any indication, even he might not know what is next for Twitter.

On November 8, after months of frustration with the Tufts Office of Residential Life and Learning (ORLL), United Labor of Tufts Residential Assistants (ULTRA) revealed their official formation and publicly announced a campaign for better working conditions. Since then, ULTRA has received official recognition from the Tufts Community Union Senate, Medford City Council, and Somerville City Council. However, despite this support, Tufts chose not to voluntarily recognize the union.

Julie Francois is a junior residential rssistant and ULTRA organizing leader. ULTRA was formed after the pandemic exacerbated concerns about payment, treatment, and transparency for Tufts RAs. She said, “Workplaces [do not] want unions because they will keep wanting to oppress workers and not really spend the money or time on them.”

By unionizing the RAs on campus, ULTRA hopes they will be able to redefine their working conditions. According to senior David Whittingham, another ULTRA organizer, the decision to unionize was catalyzed by the “long-standing issue of RAs not feeling adequately compensated and not feeling adequately treated or adequately supported by [ORLL].”

Over 80 percent of RAs support unionization. After their public announcement, ULTRA released a petition asking for community support.

ULTRA highlighted the high expectations of their job in their petition. While RAs are expected to be flexible with their supervisors’ requests, ORLL of-

fers little flexibility for RAs themselves.

Francois said, “Things get [sprung] onto us [at the] last minute and it’s a lack of understanding [and] flexibility from [ORLL].”

Francois also explained RAs are faced with ambiguous contracts where RAs themselves have little input. “[There’s] just a lot of [uncertainty] in our contracts, and unspoken obligations… For example, unpaid training is required every year—that’s two weeks. And this year [we had to handle] move-in for a lot of first-year areas, which was unexpected.”

Despite their frustrations, many students become RAs because they are dependent on the free university housing it provides. Tufts only guarantees housing for the first two years for undergraduates. Finding a place to live as an upperclassman can be difficult and unaffordable. “The primary reason people apply for being an RA is out of financial necessity,” said Joyce Fang, a sophomore and first-year RA at Bush Hall.

On November 18, the Tufts Daily published an article revealing the struggles upperclassmen face finding housing, citing financial hardships as a barrier to off-campus housing in the Medford and Somerville communities. Whittingham said, “The university knows that there are a lot of students who have [no other housing options],” leading them to become RAs despite any concerns.

Furthermore, this additional leverage imposed by the University has prevented students from calling attention to these problems. Whittingham said, “It puts the students in a very difficult position in terms of speaking out to try to improve the job… speaking out or making any change to supervisors or administration carries the risk of retaliation or termination of some kind.” A first-generation low-income (FGLI) first-year RA shared similar worries, voicing concerns about speaking out about the unionization efforts and receiving backlash for it from ORLL.

In addition to their expansive formal responsibilities, RAs also serve an important supportive role for many of their residents. Fang said, “RAs are doing a lot… the communicative labor of responding to residents and being aware of what’s going on in the halls [such as] conflict mediating [is] emotional labor.”

RAs’ efforts to foster a sense of community and inclusion do not go unnoticed by their residents. Dzheveira Karimova, an FGLI sophomore, discussed her relationship with her firstyear RA. “Being a first-generation student, it’s really difficult for me… so my RA was the first person I met who has gone through this experience,” she said. “I would consult with her all the time and be like ‘Leah, I need help.’” In this way, RAs serve a crucial role in supporting their residents, including supporting first-year students as they transition to college.

All of these concerns are especially amplified for RAs who are students of color and FGLI students. According to the union’s petition, “The university has committed to ensuring equity for its marginalized communities, but has sadly fallen short of this duty with regard to its Resident Assistants.” This grievance is supported further by TCU Senate’s Resolution S.22-4, acknowledging that “first-generation/low-income student workers are disproportionately represented in the Resident Assistant workforce, making the fair treatment and compensation of RAs integral to Tufts University’s proclaimed commitment to equity and support for marginalized groups.”

Since the Tufts administration has denied voluntary recognition, ULTRA has decided to go forth with elections through the National Labor Relations Board, an independent federal agency tasked with conducting secret-ballot elections

regarding union recognition and other issues in employeremployee relations.

Francois said, “After Tufts denied us, we just took our 85 percent support cards… and sen[t] it over to the NLRB. And they basically took that information and are going to host an election for us to win the [union] that way. That means we’ll be [able] to organize the union and we will be recognized by the [US] government.” Their unionization would result in “a bargaining situation where we’ll have elected people to be trained and sit at a table with whoever Tufts feels is appropriate to sit with us… to bargain over a contract and list out our demands.”

As ULTRA continues its process of becoming a recognized union, they hope their example can serve as inspiration for other student workers to organize and stand together in solidarity to fight for better working conditions. Whittingham said, “As colleges and universities increasingly become and behave like corporations, we hope that more unionization on college campuses can serve not only to improve the situation for workers themselves but also try to make positive change in general.” Especially as Tufts’ peer institutions such as Boston University have seen unionization efforts similar to ULTRA’s, Whittingham has expressed that he is “hopeful that this can be part of a bigger movement.”

It remains to be seen how Tufts will respond to the NLRB elections. While employers do have the right to appeal NLRB decisions, Francois said Tufts is “not actively contesting the [RA unionization] election so far… and [as] for the conversation we’ve had with the Director of ResLife, Christina [Alch], she’s been empathetic to our efforts.” Additionally, in their response to rejecting voluntary recognition, the administration encouraged the union to go through the NLRB.

Francois is hopeful about “where we are political[ly] as a nation [with] the sweeping movements of unionization, especially through [undergraduate] groups [unionizing] across campuses across the country.” She said at the end of the day, “People don’t want the bare minimum. We just want to fight

Imagine this: you’ve just been accepted to one of the best International Relations programs in the world. You arrive at Tufts, but it is not what you thought—it’s selectively “international”. Much like how feminist theorist Cynthia Enloe famously asked “Where are the women?” in International Relations, we—“brown,” “foreign,” “women”—ask “Where are the women who look like us?” We also ask, “How are they treated?” While Tufts may be increasingly diverse, it is not inclusive. Those who hold senior positions in the school administration and faculty are largely male and white. Courses about us are seen through the lens of “the other” and deemed less rigorous and too specialized. Tufts needs to do more: implement caste protections, prioritize representative and diverse faculty and course offerings, and create spaces of care and inclusion.

Simply put, we want to be celebrated, not just tolerated.

When applying to graduate school, we were acutely aware of our positionality as brown women. We felt an inexplicable sense of responsibility to be brilliant. A responsibility driven predominantly by the fear of misrepresenting “our people.” The fear that, if we said the wrong things, it would be held against everyone that looks like us.

As South Asians, this fear is compounded by the awareness that being the right kind of brown is built on privilege. Privilege in the form of financial support and in the form of support networks that help us take on the emotional labor that applying to a prestigious school entails. These are privileges that help replicate the caste-based social hierarchy wherever we go. However, the right kind of brown is a speaks when spoken to archetype of empowerment. And people aren’t speaking about caste.

So we live with the responsibility of representing our people and the silent hypocrisy of knowing that we don’t. We’re at different points in our academic journeys now, but the only constant for both of us has been the weight of this responsibility we didn’t ask for but will never turn away from.

There are several factors that disadvantage brown women trying to study IR. It all starts with picking a school and a program. It should be

news to no one that IR as a discipline suffers from westcentrism and was born out of imperialist logic. It is, however, disappointing to see how little is being done to remodel programmes to accurately reflect power and politics as they exist in the international system. Let’s say you overcome the first obstacle and find a reputed school like Tufts that offers diverse fields of study and various specialized programs. What next?

You evaluate your worth unkindly, of course. So you rule out the programs that don’t interest you. Then you rule yourself out of the programs that you think you’re not qualified for, yet, somehow, you land up here at Tufts.

One of the first things you notice in an IR school is the silent hierarchy of course offerings. You gaslight yourself into thinking it isn’t real. But disciplines like security, business, and law that are thought to require a higher level of skill, technical knowledge, or innate aptitude are treated as more important. They are largely taught by tenured male faculty. Disciplines of culture, race, gender, and several others—the “softer” disciplines—though offered, are not valued the same and are seen as less employable and less rigorous. Obviously, they more often are taught by faculty who are women, gender non-binary, and of color. They’re probably adjunct contract workers who are underpaid, overworked, and, most likely, “disposable.”

So when brown women try to find their place in this hierarchy, the assumption is that we will be more interested in the disciplines that don’t require a high level of skill, technical knowledge, or innate aptitude—things we are seen to not possess. For those of us who choose to study disciplines at the top of the hierarchy, we are often presumed incompetent. We are not taken “seriously.” The standards for brilliance are designed to not include our work. Research by and about us is seen as anecdotal, less rigorous, and not theoretical. Our panels are relegated to the small rooms at conferences, our events are publicized less, and our research is funded less. Our critical commentaries are framed as ranting and raging (just as this one will be).

And for those of us who choose the softer disciplines (a choice both of us have made), we face the same struggles. But we are also a self-fulfilling prophecy, weaponised against those who look like us and follow similar paths: incompetent people study incompetent disciplines. As a faculty member once described one of our feminist ethnographic projects, we are “only talking about [our] feelings.”

In addition to exceeding the unrealistic standards of brilliance, there is a quiet expectation that we will provide free labor by educating those around us about the very conditions that oppress us. We’ll serve on diversity, equity, and inclusion committees, organize intersectional conferences, and appear in photographs on the university website touting the diversity of the student body. This isn’t new. But we are tired. This free emotional, intellectual, and physical labor we perform causes what Audre Lorde described as a “constant drain of energy which might be better used in redefining ourselves and devising realistic scenarios for altering the present and constructing the future.”

Despite this, we persevere. We speak. What then? Do our words change systems? No. Because we are either seen to speak for all of us or none of us. We represent what every brown person thinks or just ourselves. Brownness is either homogeneous or hyper-individual. It’s all or nothing. Because these aren’t facts. Facts are white. Opinions are brown.

The individual and collective exhaustion caused by these microaggressions is anything but small. We’ve created small spaces of care and joy on campus and off, where we “tend to” and “attend to” each other. As Audre Lorde says, care and joy have become forms of resistance. But it is time for more. It is time that the system listened and changed. Changed so that we can stop fighting to exist, and start demanding opportunities for excellence and spaces for exuberance. The structures around us need to be redesigned for more than just our survival; they need to be designed for our pleasure.

Sunil Kumar was recently appointed as the incoming President of Tufts University, the first person of color to have been appointed to this position. Does this signal progress, or is it a representation of the insidious mechanisms that maintain power asymmetries? We hope that making visible the everyday racist microaggressions helps Kumar make good on his commitment to exploring “how to make the Tufts experience available to more people, and how to make sure the experience is even better.”

Tufts needs to invest its resources in creating visible spaces for us to “celebrate our unbelonging.” There is a need to go beyond numbers. The student body’s diversity doesn’t imply its inclusivity. The fact that regional and racial diversity is increasing doesn’t imply socioeconomic diversity is, too. So where do we go from here?

Building trust is an important part of creating space to celebrate “unbelonging.” We need to trust you when you say we matter. We need to see more people that look like us, being treated how we hope to be treated. We welcome the appointment of the new President, which is a step in the right direction, but only one of many that are yet to be taken. We need to see that the issues we care about are issues that matter to the university. For example, Tufts is yet to identify caste as a protected category, a step taken by several universities across the country, most recently Brown.

We need to see that you recognize the heterogeneity of being brown and celebrate it. We need more funding and scholarships. We need to see our research highlighted. We need a break—we’re exhausted.

Last month, one of us (along with a team of 10 wonderful humans) organized Fletcher’s largest student-run conference, The Gender Conference. In the aftermath of an enriching academic opportunity, we were told that the conference “was good but too South Asian.” Too South Asian in this context was defined as seven out of the 27 speakers we invited being of South Asian origin.

We need to know that we are at a university that deserves our labour. A university that recognises that, however we choose to show up, we are not too little, we are not too much. We are enough.

n.therealizationthateachrandompasserbyislivingalifeasvividandcomplexasyour own—populated with their own ambitions, friends, routines, worries and inherited craziness—anepicstorythatcontinuesinvisiblyaroundyoulikeananthillsprawling deepunderground,withelaboratepassagewaystothousandsofotherlivesthatyou’ll neverknowexisted,inwhichyoumightappearonlyonce,asanextrasippingcoffeein thebackground,asabluroftrafficpassingonthehighway,asalightedwindowatdusk.

I

n past years, Tufts students could order a cake from Tufts Dining on their birthday. The baking staff would bake a homemade cake, decorate it, and even write a message on the top. Tufts service attendant and shop steward Tricia O’Brien recalls this fondly. “That made so many people’s days,” she said. Now, with short-staffing and budget cuts, ordering custom birthday cakes from Tufts is no longer an option.

According to Tufts Labor Coalition (TLC), a student group that advocates for workers’ rights on campus, Tufts Dining has reduced its baking staff from four or five bakers to two since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. As the staff has shrunk, Tufts has not re-hired enough bakers to equal the pre-pandemic team. This has resulted in additional labor for the remaining employees. “We used to work normally,” Tufts baker Raymond Cormier said. “Before, when we had four bakers, we made our stuff and it was a good time. Now, we’re trying to rush to get things done…[It’s] more stressful.” With the limited amount of hands on deck, if even one bakery staff member calls in sick, it means nearly double the work for the remaining employees. “The managers have got to start realizing that we need more help,” Cormier said.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Tufts began to outsource baked goods, purchasing frozen products from outside suppliers when baking on campus every day wasn’t an option. Before the pandemic, the more robust baking team made most bakery products from scratch; this is no

longer the case, as Tufts has decided to continue outsourcing goods even past the worst of the pandemic. “They’re outsourcing everything,” O’Brien said. “They’re outsourcing the pizza dough… They’re outsourcing cakes.” Tufts Dining has not made it public if they plan on continuing to outsource baked goods in the future. To Cormier, there is an essential difference

own recipes with ingredients of their choice. Cormier mentioned his frustration at having to work with exclusively European butter instead of regular butter. While Cormier understands it is important to sometimes use this butter replacement to produce vegan desserts, he also believes it takes away from the quality of non-vegan products. Lee corroborated this, adding that the lower-quality taste of the baked goods is not fair to students. “The student pays for it. They should have good food,” she said. Cormier doesn’t think the managers would be receptive if he requested different ingredients.

between the quality of goods that Tufts promises and the actual food that is served. “[Tufts’ dining website] says it’s freshly baked every day, but it isn’t,” Cormier said. “It’s freshbaked someplace else and brought in.”

This shift has led to discontent within the baking staff, who were accustomed to baking their

Outsourcing and ingredient replacements have not been the only changes in the way baked goods are produced at Tufts; the diversity of homemade bakery products made on campus has taken a hit as well. Instead of making their own array of recipes, staff members largely recreate the same menu each week. Baker Melissa Lee expressed there was a difference between what she had been promised in her hiring process and what the actual daily life as a bakery employee looks like at Tufts. “In the interview for this job they said ‘they will have a lot of different desserts,’ but for me, when I work here, I don’t see those things… I just do the same thing every week,” she said. Cormier has witnessed firsthand how baking at Tufts has become more repetitive in recent years. “We [used to have] a big display and we had all kinds of cakes that I did… they cut that out. They said it was just too expensive,” he said.

Shifts in the way food is produced at Tufts have meant that baking staff have been given less space to

“WE DON’T HAVE THE MANPOWER AND [TUFTS DINING MANAGERS] DON’T WANT TO HIRE ANYBODY ELSE,” CORMIER SAID. “IT SEEMS LIKE THEY’RE PUSHING US OUT.”

work. According to Cormier, since Tufts Dining relocated the production of hot food for Hodgdon Food-on-the-Run to Dewick, bakers have struggled with a lack of storage space. “I had four tables,” Cormier said. “Now we’re lucky if we have two… They took my bench on the bottom. The cupcake tins and everything… some stuff got thrown away.” Much of the baking staff’s equipment has been moved aside or thrown out in order to make space for other facets of dining. Cormier explained that even the freezer allocated for bakery items has been recently opened up to the whole central kitchen. This has left only a small freezer for the baking staff to store food in, which is not enough space for the amount of products the staff hopes to make.

All of these changes have made Cormier and Lee feel unprioritized by the Tufts Dining managers. The bakers fear for the future of their jobs. “We don’t have the manpower and [Tufts Dining managers] don’t want to hire anybody else,” Cormier said. “It seems like they’re pushing us out.” Dining managers have chosen efficiency at the expense of their employees.

Discontent among the bakery staff has led the remaining employees to seek help from the Tufts Labor Coalition to demand the revitalization of baking at Tufts. In response, TLC has formulated a petition, which links a series of demands to be delivered to the administration.

The first of these demands is that Lee must be able to work full-time during the upcoming winter break. In previous years, according to TLC member Emma Cohen, the university would employ at least one baker during recesses for students who remained on campus. This is no longer the case. Rather than employing Lee to bake during winter break, Tufts Managers are asking Lee to pre-prepare goods and freeze them. Cohen said, “Now what they’re doing is having [Lee] make a bunch of goods before break, [and] freezing them so that she doesn’t work over break. Students don’t get fresh food, but the university doesn’t have to deal with any of those consequences.”

These consequences go beyond the freshness of the bakery products. Without work at Tufts, Lee will be left without a source of income for the span

of winter break. TLC believes that it is the university’s responsibility to employ Lee in order to “support her own livelihood,” according to the petition. Lee is a nonlegacy employee, which means her contract does not technically require her to get paid time off during recesses. However, TLC members feel this should be amended given short staffing. Cormier is a legacy employee and receives paid leave.

TLC also demands more open communication from the administration about the quality of outsourced food, and their third demand is for outsourcing bakery products to stop completely. Finally, TLC demands “Tufts University publicize a plan to have a total of five full-time bakers employed by Tufts Dining by the start of Spring semester, January 17th,” according to the online petition.

TLC has sent the petition out to the Tufts community and has delivered it to the dining management team in a meeting organized by TLC. “These kinds of efforts can work,” Cohen said. “We really believe that we can make these changes happen as long as everyone steps up and supports this all together.”

Note: Liani Astacio is currently a member of Melisma and WMFO.

After a year and a half of radio silence from Tufts’ live music scene, bands ranging from indie to jazz to pop emerged on campus at the start of the 2021 academic year. This reemergence of live music coincided with the loosening of COVID restrictions last fall, allowing for both student bands and bands outside the Tufts community to perform on campus.

Some of Tufts’ well-known music clubs have had a presence on campus for decades. WMFO has been the campus radio station since its start in 1956 when it was an AM broadcast known as WTCR, or Tufts Community Radio. By 1969, WMFO eventually became an FM freeform broadcast after receiving a hefty grant from Tufts University. Applejam, a club that hosts live music events, has been a campus fixture since as early as 2003 and once even hosted a pre-Be the Cowboy Mitski.

Live music culture isn’t new at Tufts; in fact, Tufts has produced a number of highly successful artists, including multi-Grammy award winner Tracy Chapman, who graduated from Tufts in 1987. She was discovered by a Tufts parent and music producer Charles Koppelman while still a student at the university. More recently, Tufts has produced bands such as the indie-alternative band Crumb, which has amassed almost 2 million monthly Spotify listeners. Band culture has continued to be a part of Tufts’ student culture.

However, many students are just recently getting their first taste of the live Tufts music scene and culture. Junior Amelia Oliver started a new WMFO show called Post-Adolescence Glow

in October, dedicated to playing live music from Tufts bands and musicians. She said, “I started Post-Adolescence Glow [when I was] missing music [due to COVID] and hoping to bring it back into my life in a totally new way.” She added, “It is so exciting being around live music every week and seeing the amazing musical and creative connections within these groups.”

Junior Joanet Plascencia spoke on her experiences engaging with the different music clubs at Tufts and her efforts in starting a band. Her band practices in Tufts’ studio spaces and takes advantage of the equipment available. She said, “There’s so many great resources here, and I really appreciate it because I feel like I have resources as well as a supportive community of friends and other music enjoyers.” She noted that in her first year at Tufts she was not aware of many music clubs at Tufts, but said, “It’s become more open and welcoming, and more people are learning about these clubs, learning about these shows.”

While Plascencia expressed excitement and enthusiasm for live music at Tufts, she also described concerns about the lack of diversity within many of these spaces. She cited the amount of physical space white students take up as a barrier to her enjoying some shows on campus. Her least favorite thing about the live music scene is “how white the spaces are and how entitled people can be in these crowds.” Plascencia said, “I’d like to see appreciation for music genres that were created by people of color.” Many significant genres including rap, jazz, blues, reggaeton, funk, bachata, cumbia, and samba were created by

Black and Indigenous communities, but have not always received respect from white Western culture. She explained that, while it’s impossible to escape how white a predominantly white institution like Tufts is, she hopes more people of color can feel safe in music spaces at Tufts. She said the reality of a lack of diversity in these spaces “can be a turnoff and make [students of color] feel unsafe or not valid.”

Plascencia expressed hope for more inclusive music spaces on campus. She discussed how a lot of the dance groups have a strong aspect of musicality, especially the step teams such as ENVY, challenging what is considered music. She said, “I really do appreciate some of the events that cater to just Black heritage and art. Even if it’s just the dance groups.” She described how she hopes her upcoming band, which is composed entirely of people of color, will help continue to make space for other students of color in the independent music scene.

Ian Smith, Editor-in-Chief of Tufts’ music journal Melisma and member of Applejam and WMFO, also commented on the lack of diversity within the music scene at Tufts. They said, “[Applejam] is a pretty white club, and then the people who are also going to the shows I would say are majority white.” They also commented that a majority of the bands that perform at the shows are predominantly cis white men.

Smith discussed how important it is to try to make music spaces at Tufts more inclusive, despite its current state. They said, “What I want to try and improve on in [Melisma] is uplifting more people of color and women with the articles that we write because the indie music scene as a whole is pretty white, although there have been efforts in the past 5 to 10 years to change that.” They added how

National Public Radio’s Tiny Desk concerts called Earworms, in which they hope to spotlight musicians that have not had the opportunity to take up a lot of space within the current channels at Tufts. They have also reiterated the idea that the Tufts music scene has not been inclusive of all genres and want to create space for more variety. Ybáñez said, “We want genre variety and music in different languages, something that’s not just shoegaze.” Shoegaze is a predominantly white-dominated genre under the indie umbrella that Ybáñez attributed as being the most common genre played in the Tufts music scene.

Hirschorn-Martinez also mentioned how the label of indie and “cool music” can be incredibly limiting and creates a feedback loop of what type of music is accepted in performance spaces and what is not. She said, “What type of music is deemed indie? What sounds and what instruments? What vocal patterns? What quote unquote is cool.” Ultimately, according to Hirschorn-Martinez and Ybañez, creating spaces that move beyond the limiting label of indie music would help create a more inclusive live music scene.

Ybáñez added that many of the live music clubs are larger extensions of friend groups, and with a socially-segregated school like Tufts, these spaces are always going to be dominated by the same people and be predominantly white. She described conversations she had with other students, especially musicians, who feel like performance spaces are impenetrable to those who are not already part of the predominantly white in-group. “[The people who get to perform] often know someone or look a certain way, dress a certain way, and/or listen to certain artists,” she said.

Ybáñez also described the importance of working on making the music scene more inclusive. “It’s one thing to recognize [the exclusivity]. It’s another thing to do something and act on it. And I think that there’s just so much talent here that goes unheard,” she said. “I think [working on promoting inclusivity] is definitely a collective group effort.”

important it is that Melisma makes more of an effort to cover artists that are not under the label “indie,” and delve into genres with roots in the Black and Latinx diaspora such as reggaeton and genres dominated by women, such as pop.

Historically, indie rock and do-it-yourself cultures have disassociated themselves from popular culture even though the genres are also framed within the values and ideals of white Western culture. The DIY music culture, which prides itself on musicians using resources available to them, still has had problems with inclusivity and accessibility. Independent artists of color, especially those who make art drawing from their identities, still have not received the same amount of success or critical acclaim as many white artists, despite many white indie musicians taking influence from Black and brown artists, as well as the fact that Black musicians invented rock music.

Other students are also brainstorming ways to make a more inclusive and diverse music scene that breaks away from the white indie norm. Anevay Ybáñez, Amalia Hirschorn-Martinez, and Ruby Goodman have been working on a project based on

The current state of the live music and band scene extends upon a larger problem in music, especially within indie or alternative music spaces that take up a lot of space on college campuses. Many Tufts students have recognized how collective action and hard work on multiple levels are necessary in order to change a radically growing live music culture.

By Chloe Cheng

By Chloe Cheng

My mother says an illness grows in the heart like homesickness. I worry I will never be home.

I wrote an apology to you.

I’ve been a bad friend. I miss you.

Look at me, see the longing deep in my retinas to hurt stronger, to su er deeper. I should have died at eighteen.

I am too sad to sleep tonight. I feel small, covers su ocate me. I am the dot of an “i” in a long, long letter: … A mountain lake and a gray sky, fallen owers caressed our cool skin. We worshiped the way the cold water burned. …

I’m sorry I was a wretched in uence. It was my fault you got bad again. I’m sorry I bled in front of you; I’m sorry I tried to die.

I want to tell you how much I love you, but I’m scared it will sound too much like a goodbye. I’m not ready yet, I hope you know that.

I let my pain spread like ink on a tear soaked page. I won’t rope you into my mess again; I am not the sel sh child I once was.

by Tobias Fu

by Tobias Fu

November comes late in my hometown.

Street cleaners diligently collect Fallen leaves, golden and brown.

Dazzling rain calms down Bustling crowds and glittering alleys.

Colorful lights re ect in the puddle On a redbrick road and foggy bus windows. daylight falters through autumnal sky walk to the grocery store and rest in the park. going to Jade Buddha Temple, lady with a stick staggering across. up the streets of a sepulchral town!

and pities our ruins. my fellow compatriots,

By Erin Zhu

By Erin Zhu

When I come home during the holiday breaks, I often catch myself spending considerable time reflecting on the past, recalling childhood moments and experiences. I’m sure most of the events, at the moment I experienced them, were rather bland and unremarkable. But the act of remembering, in and of itself, is pleasurable. Over the years, my memories have been sanded down and polished into something precious. I find myself wondering what shape they will take in 10, 20, or 30 years from now; how their meanings will change when I am much older, and whether or not they really mean anything at all.

When I consider the memories that dominate my recollection of early childhood, it is the years I spent on Elmwood Road that I recall the most vividly. To provide some background: from the ages of two to six, I grew up in a two-family, two-story house on Elmwood Road with white siding and a brown roof, located in a modest and aging New Jersey suburb. The

property included a large front yard with scattered patches of dead grass and forsythia bushes dividing our lawn from the next-door neighbor’s. My father, mother, and I lived on the first floor while another family lived above.

The family had a son named Steven. Steven had dark hair that would lie flat on his head when it got wet and then spike up like a pufferfish after it dried. The summers he spent playing soccer and baseball had tanned his arms and legs, and out on the field, he jogged as many children do: like limp spaghetti conjoined at the elbows, hips, and knees. He was shy around strangers and often ducked behind his mother, clutching her shirt and turning his face away. But his lips would be pursed, his shiny eyes darting back and forth as if on the verge of committing something clandestine but harmless.

Neither Steven nor I had any siblings, so we found replacements in one another. I would say most of the characteristics I

took on during this period of time were just pitiful attempts at mimicry. He played soccer, so I did too (poorly), he watched football, so I tried it too (wasn’t for me), and when we started first grade he began obsessively collecting Pokémon cards (I actually excelled at this one). During one Christmas, he had come downstairs and, upon seeing the decorations scattered across the dining table waiting to be hung on the tree, proposed a competition. He decided we should see who could throw the round glass ornaments the furthest. I agreed this was an incredible idea, so one by one, we took the round, satin-finished Christmas ornaments and hurled them across the living room until my mother caught us and shooed us upstairs.

Steven’s father had a separate room on the second floor with an electric keyboard and a good sound system. When Steven and I were bored, we would bound up the

is a Highway” (the Pixar movie Cars had recently come out), and we pretended to play the guitar and drums and jumped into dramatic slides on the carpet floor and screamed in naive agony. When we did this, his mother would come in and tell us to quiet down before she returned to the kitchen table to study, as she wanted to be a nurse.

Sometimes, I would come up behind her and watch her take her index finger and trace the lines of the textbook as she jotted on her notepad. The words were cramped densely on the textbook pages to the point where they were almost illegible, and I would eventually wander away, looking for something more interesting. But when I close my eyes and look back in time, I see her seated at the kitchen table, one index finger tracing and the other hand writing.

***

We had a blue inflatable pool, and in the summertime Steven and I would watch, our legs jogging up and down, while his mom pumped air into it. Afterward, she would drag the long green hose across the backyard, prop it against the pool wall, and all three of us would watch the water pour into the chasm of blue plastic. Water would spill outwards, dampening the soil around the base, and our arms

and legs would become flecked with wet, green grass clippings. When it was filled to the brim, Steven and I leapt in.

With our backs to the bottom of the pool and our bellies facing up, we pushed ourselves through the water like toads. We pretended we were scuba diving, tracing our fingers over the ridges of the interior, or picking up stones that had somehow ended up at the bottom. Sometimes, I would let myself sink downwards till my back hovered over the bottom of the pool, and I would watch the light hit the water and scintillate along the sides.